#robert morstein-marx

Text

And now, a book review I've been saving. I want to savor this one:

Julius Caesar and the Roman People, by Robert Morstein-Marx, 2021.

It's hard to overstate how much I love this book. If you only read one book about Julius Caesar, get this one. It's not just a biography of Caesar, but a reassessment of the role of the "People" in Roman politics, of how democratic vs. oligarchic the republic truly was, of reliability and bias in ancient sources, and how we construct history through the lens of our own values and fears. Morstein-Marx sets out not merely to describe Caesar's life, but explore where our ideas about him came from, what biases are in our sources, and how those biases erased the agency and diversity of the Roman People themselves.

When I first read this book, I found it persuasive and well-researched - Morstein-Marx is a professor of classics, after all - but its conclusions were so different from the pop culture view of Caesar I had to check if this was another Michael Parenti situation, where an author exaggerates and cherry-picks evidence to support his own political agenda. But, from all the other references to this book I found, Morstein-Marx does seem to be a respected scholar who knows what he's talking about, and other historians like Erich Gruen, Fred Drogula and John T. Ramsey seem to agree with a lot of his points.

So, what are his main points?

That Caesar was not a radical popularis or Marian, nor was he consciously attempting to subvert the republic or install himself as an autocrat; his career up till 49 BCE was broadly conventional, his policies moderate, and his rift with Cato et al is better explained by personal rivalries, not ideology.

That Caesar was in many ways more traditional and respectful of the law than Cato, Bibulus and their allies, and there was a legitimate argument for siding with him in 49 BCE.

That much of the argument for seeing Caesar as subversive or radical depends on equating the government with the Senate, and downplaying the role of the People.

That neither Caesar nor Pompey deliberately started the civil war, but that it happened due to a breakdown in communications between the triumvirs, and fearmongering from a pro-war faction in the Senate.

That the majority of the Senate and People probably sided with him during the civil war.

That it's not actually clear whether Caesar "wanted to be king." Many of his actions as dictator are better explained as ad hoc responses to immediate political crises, while others may have been taken out of context, exaggerated or misattributed to him.

Now, you might be thinking this sounds awfully pro-Caesar. And Caesar does come across more sympathetically than in most portrayals. But Morstein-Marx also reminds us that Caesar killed or enslaved about two million people, ended free Roman elections, and other awful things. He tries to explain Caesar's actions, but not to excuse them.

Morstein-Marx's argument is not that Caesar was a hero, or a villain, but an ordinary man and product of his time. He was, to be honest, just not that important until his runaway success in Gaul. He had no long-term master plan, but was reacting to immediate issues most of the time, like all politicians do. His policies were mostly conventional, not revolutionary.

Julius Caesar and the Roman People is an attempt to take off the filters of hindsight, myth, and propaganda, and try to understand Julius Caesar's actions in the context of his time. And it will teach you a lot about how history is "constructed" along the way.

#i really need to reread this one and see if i still agree with all his conclusions#but he definitely Did The Research#robert morstein-marx#julius caesar and the roman people#jlrrt reads#book rec#book review#julius caesar#hot takes with jlrrt

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

what's. what the fuck wrong with them. good grief. I need to put the three of them in a jar and study them

Mark Antony: A Biography, Eleanor Goltz Huzar

Julius Caesar and the Roman People, Robert Morstein-Marx

Mark Antony: A Biography, Eleanor Goltz Huzar

#if you follow me elsewhere you may have witnessed me descend into some kind of dolabella madness yesterday#which took an abrupt left turn when i got to the 11th philippic like YEAH ACTUALLY TEAR THE BITCH APART. GET HIM CASSIUS#justice for my man trebonius. cicero's letter to him got me feeling so emotional#this love triangle political clown show bullshit has a body count that makes the tris homines look moderate as a whole good GOD#gaius julius caesar#mark antony#roman republic tag#drawing tag#komiks tag

197 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you recommend any non-fiction books about roman history for someone looking to get a little bit deeper into it?

yeah! do also check my book rec tag because ive probably answered something similar to this at Some point. also bear in mind this is specific to the roman republic (and tbh mostly the late republic) because i just do not care. like rome kept happening but who Give a shit. look at it. it's got emperors. anyway

a companion to the roman republic ed. nathan rosenstein and robert morstein-marx and the cambridge companion to the roman republic ed. harriet i. flower are both absolutely massive and full of v good introductions to a variety of topics! get basic understanding of a thing! nice!

some specific Books I Like on individual topics: the rise of rome: from the iron age to the punic wars by kathryn lomas covers the earliest roman Anything up to the third century And grounds that history in the context of what was going on in the rest of italy at the time. roman republics by harriet i. flower is about different ways of periodising the history of the republic(s?) and in doing so gives a good overview of major changes to the political system. party politics in the age of caesar by lily ross taylor is Quite Old but imo still holds up as an introduction at least.

you could also consider Picking A Guy and reading a biography. love it when a life is put into the context of wider history while also existing as a more coherent narrative on which to pin that history. some that are fun are sulla: the last republican by arthur keaveney, the patrician tribune by w. jeffrey tatum about clodius pulcher (the introduction is also suchhhhhh a good summary of 'party' politics and why that's not a great way to think about it!), clodia metelli: the tribune's sister by marilyn b. skinner about clodius' sister who was maybe also lesbia from catullus' poetry, cato the younger: life and death at the end of the republic by fred k. drogula, fulvia: playing for power at the end of the roman republic by celia e. schultz (i have been meaning to read this one lol), and brutus: the noble conspirator by kathryn tempest.

my anti-recommendation is rubicon by tom holland No i have not read it Yes i think it sucks. L + i have been shown excerpts of the bad prose + the republic had fallen apart way before caesar crossed the rubicon + the author has a whole bunch of bad takes + read attis (1996) instead

#clutuals as always i welcome your book recs <- guy who got into roman history via historical fiction#book list#beeps

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic, Robert Morstein-Marx

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

robert morstein-marx in every article about the civil war like: yall. im sorry. it has to be said. this topic has been beaten into hell. the prosecution theory is not probable.

#thanks mr morstein-marx i think i got it#yall i think he doesnt think caesar would have feared prosecution... i could b wrong?#gaius julius caesar

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

If I wanted to start researching Caesar where should I start? Asking because I know you like him, and it’s for a project

yayayayaya :3 caesar !!!! yay !! :3 thank u sm for asking me i feel honoured

uhhh honestly this is hard to answer bc i’m not sure how much depth you’re after and if there’s a particular focus for your research so i guess i’ll keep it general ???

my go to writers on caesar tend to be adrian goldsworthy and robert morstein marx, they both do really good overviews of caesar but also have more specific stuff on him too (goldsworthy did a really awesome little book about the civil war that is really fun to look at). i also like to recommend pat southern for general biographies on caesar and the emperors, i don’t always agree with her arguments (ie claiming domitian was Like That because of mommy issues😔💔) but i find her approach in general to be a lot more nuanced and interesting i dunno. her biography on caesar is good and easy to read

in terms of contemporary sources i do recommend reading caesar’s own writing both for an insight into his mode of propaganda and as a source for his military and political endeavours (i will warn you his writing style is infamously bland but i think it’s really interesting and like. he writes that way on purpose it’s part of the propaganda) and obviously suetonius, plutarch and cicero especially have a lot of interesting things to say about caesar too

i can send and/or recommend you individual papers or books on more specific aspects if you like (eg i have a Lot on the civil war, loads on caesar’s writing style, LOADS abt his architecture/material culture as propaganda, stuff about his personal life and some medical perspectives on his epilepsy) but i wasn’t sure what u were looking for, just message me abt anything here or on @caesxr <3

#i hope this is helpful ???? i didn’t want to write too much#also in terms of your wording it is imperative that i make you all realise that i do not “like” caesar as such shskshskshhsksj#he’s like. my pet historical figure hes simply a fascinating evil critter to me. he was a stinky horrible guy#i want to get inside his fucked up brain. he’s the poster child of roman toxic masculinity and imperial Conquerer mindset#i study him like a scientist studying a new and disgusting strain of micro bacteria

0 notes

Photo

*angry mob laughing in the distance

(Morstein-Marx, Robert. Mass oratory and political power in the late Roman Republic. Cambridge University Press, 2004.)

0 notes

Text

Free Classics Books

You can read 700+ free books from UC Press online. I combed through those 700 or so books to find those that would be useful to Hellenic/Hellenistic Polytheists. This is pretty much all of their free Classics books so it contains Roman and Greek religion, history, philosophy, and poetry. I have not read these yet, so this is a list for me as much as everyone else. If something looks like it doesn’t belong, let me know, and I’ll check it out.

Myth, Meaning, and Memory on Roman Sarcophagi - Michael Koortbojian

The Revolutions of Wisdom: Studies in the Claims and Practice of Ancient Greek Science - G. E. R. Lloyd

Hellenistic History and Culture - Edited by Peter Green

Reading Sappho: Contemporary Approaches - Edited by Ellen Greene

Regionalism and Change in the Economy of Independent Delos - Gary Reger

Athenian Democracy in Transition: Attic Letter-Cutters of 340 to 290 B.C. - Stephen V. Tracy

Senecan Drama and Stoic Cosmology - Thomas G. Rosenmeyer

The Development of Attic Black-Figure - J. D. Beazley

An Archaeology of Greece: The Present State and Future Scope of a Discipline - Anthony M. Snodgrass

Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles - Charles W. Fornara and

Loren J. Samons II

Tragedy and Enlightenment: Athenian Political Thought and the Dilemmas of Modernity - Christopher Rocco

Epic Traditions in the Contemporary World: The Poetics of Community - Edited By Margaret Beissinger

Rome Before Avignon: A Social History of Thirteenth-Century Rome - Robert Brentano

Traditional Oral Epic: The Odyssey, Beowulf, and the Serbo-Croatian Return Song - John Miles Foley

Catullan Provocations: Lyric Poetry and the Drama of Position - William Fitzgerald

The Poet's Truth: A Study of the Poet in Virgil's Georgics - Christine G. Perkell

Thucydides and the Ancient Simplicity: The Limits of Political Realism - Gregory Crane

Spectacle and Society in Livy’s History - Andrew Feldherr

Plato's Euthydemus: Analysis of What Is and Is Not Philosophy - Thomas H. Chance

Fiction as History: Nero to Julianau - G. W. Bowersock

The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity - Paul Zanker

Dioscorus of Aphrodito: His Work and His World - Leslie S. B. Mac Coull

Hegemony to Empire: The Development of the Roman Imperium in the East from 148 to 62 B.C. - Robert Morstein Kallet-Marx

The Power of Thetis: Allusion and Interpretation in the Iliad - Laura M. Slatkin

Religion in Hellenistic Athens - Jon D. Mikalson

Form and Good in Plato's Eleatic Dialogues: The Parmenides, Theaetetus, Sophist, and Statesman - Kenneth Dorter

Money, Expense, and Naval Power in Thucydides' History 1-5.24 - Lisa Kallet-Marx

Theocritus's Urban Mimes: Mobility, Gender, and Patronage - Joan B. Burton

Descartes's Imagination: Proportion, Images, and the Activity of Thinking - Dennis L. Sepper

Images and Ideologies: Self-definition in the Hellenistic World - Edited By Anthony Bulloch, Erich S. Gruen, A. A. Long, and Andrew Stewart

The Best of the Argonauts: The Redefinition of the Epic Hero in Book 1 of Apollonius's Argonautica - James J. Clauss

Dynasty and Empire in the Age of Augustus: The Case of the Boscoreale Cups - Ann L. Kuttner

Guardians of Language: The Grammarian and Society in Late Antiquity - Robert A. Kaster

The Defense of Attica: The Dema Wall and the Boiotian War of 378-375 B.C. - Mark H. Munn

The Politics of Desire: Propertius IV - Micaela Janan

Horace and the Gift Economy of Patronage - Phebe Lowell Bowditch

Nuptial Arithmetic: Marsilio Ficino's Commentary on the Fatal Number in Book VIII of Plato's Republic - Michael J. B. Allen

The Question of "Eclecticism" Studies in Later Greek Philosophy - Edited by John M. Dillon and A. A. Long

Public Disputation, Power, and Social Order in Late Antiquity - Richard Lim

Nemea: A Guide to the Site and Museum - Edited by Stephen G. Miller

Aristotle on the Goals and Exactness of Ethics - Georgios Anagnostopoulos

Virgil's Epic Technique - Richard Heinze

Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius - Alan Cameron, Jacqueline Long

Representations: Images of the World in Ciceronian Oratory - Ann Vasaly

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Companion to the Roman Republic

Nathan Stewart Rosenstein and Robert Morstein-Marx

eBook - click to read

0 notes

Text

More notes on the development of Roman imperialism and colonialism:

Rome began as a city warring with other cities and city-states in Italy. Its growth was haphazard and, in some ways, accidental. They don't seem to have thought of it as an "empire" in the sense of "our land and sea," until the 1st century BCE.

Before then, the Roman empire was characterized by active military control, not by thinking of lands as "Roman territory." This was not the USA trying to grab all the land it could in manifest destiny; this was a city-state that primarily aimed to enrich and defend itself, and often used military occupation to do so.

The Romans did not like to think of themselves as an expansionist power, but as fighting defensive wars for themselves and their allies. However, the Roman system of alliance building - and sometimes provoking other countries - frequently "pulled" Rome into wars anyway. And Roman generals who really wanted a war could often invent justifications for it. Caesar's conquest of Gaul is one of many wars that started as "protecting an ally from invasion" but which soon became opportunistic power-grabs.

Even so, this self-concept as "defenders" partly explains why the Romans mostly left defeated Italian communities intact, only demanding troop levies and sometimes confiscating part of the land. Draining conquered peoples dry or wiping them out was not the goal, and the Romans actually prided themselves on being relatively "merciful" to their neighbors (by classical standards). However, as Rome's sphere of influence grew, and the distance from Rome to defeated (and potentially rebellious) communities increased, they began stationing permanent military outposts in certain regions.

Roman colonies originated as military outposts. They served a quadruple purpose: 1) to punish communities that had rebelled or fought wars against Rome; 2) to reward Roman veterans; 3) to relieve economic tensions in Rome itself; and 4) to suppress further rebellion by maintaining Roman outposts in the region.

This is in contrast to Greek and Phoenician colonies, which were usually established by traders, and the USA's westward expansion, which aimed to replace indigenous peoples en masse.

Similarly, the word "province" originally referred to a task or assignment, not a geographic area. A proconsul might be assigned the "province" of Spain of Sicily in the sense of "keep this region from revolting."

Economic exploitation came later. The Punic Wars marked a turning point in which Rome stationed generals overseas for extended periods of time to prevent insurgency among subject peoples, not Italian allies who were acknowledged as mostly self-governing. These generals had immense latitude to do as they saw fit, and with the promise of armed protection, Roman businessmen soon saw opportunities for mining, slave plantations, and more. This is also why Spain, Sicily, and certain other regions were abused much more harshly than Italy itself.

In the 1st century BCE we see a slow shift toward conquest of lands being sought for its own sake, rather than as a by-product of war. By the reign of Augustus, writers imagined Rome conquering the whole world.

Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul occurred midway through this ideological shift. Hence he felt the need to justify his conquest by presenting his side of the story in his Commentaries, but the public response to his needless invasion of Britain was overwhelmingly positive. Conquest, if successful, was beginning to justify itself.

However, the Romans also gradually came to see themselves as responsible for the government of long-term provinces, and take measures to curb abuse of provincials. Caesar himself installed one of the biggest reforms limiting corruption. (Yes, he was a bit of a hypocrite...)

The gradual expansion of citizenship across the empire and military recruitment from provincials gradually put pressure on the Romans to value more than just Italian interests. We first see this with Julius Caesar's attempt to extend Latin Rights to Sicily and citizenship to Cisalpine Gauls; it reached its final form when the Edit of Caracalla made all free inhabitants of the empire citizens in 212 CE. The "Romanization" of Europe did not happen by displacing the original inhabitants of provinces, but by incorporating them.

Sources: SPQR by Mary Beard; A Companion to the Roman Republic, ed. Rosenstein and Morstein-Marx, chapters 6-7. See also my previous post on this topic.

#jlrrt reads#a companion to the roman republic#nathan rosenstein#robert morstein-marx#colonialism#imperialism#there were some cases of mass displacement and genocide btw. but at the risk of hair-splitting: these occurred as part of wars#rather than as the goal of roman colonialism per se#jlrrt essays

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love it when English-speaking historians apparently decide "This is getting complicated - break out the emergency German!"

Nathan Rosenstein and Robert Morstein-Marx, "The Transformation of the Republic," in A Companion to the Roman Republic.

Another great one is Schwertübergabe (sword-handover), which is used specifically for that one time consul Marcellus handed Pompey a sword late in 50 BCE and told him to raise an army against Caesar, at least in the English books I've read.

#nathan rosenstein#robert morstein-marx#jlrrt reads#a companion to the roman republic#the transformation of the republic#christian meier#gefälligkeitsstaat#schwertübergabe#german

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorite accidental running joke in Julius Caesar and the Roman People is Robert Morstein-Marx's 21-year-long ongoing argument with a rival historian in Germany about obscure points of Roman law:

#ALWAYS read the footnotes in this book#caesarhell#julius caesar and the roman people#robert morstein-marx#k m girardet#just roman memes#jlrrt reads

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

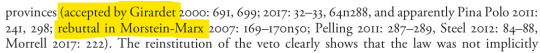

Look, I'm not saying Robert Morstein-Marx traveled back in time and personally killed Cato the Younger, I'm just saying if any historian had a motive--

(Robert Morstein-Marx, Julius Caesar and the Roman People, p. 582)

#just roman memes#cato the younger#marcus calpurnius bibulus#robert morstein-marx#julius caesar and the roman people#jlrrt reads#caesarhell

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guys, I just thought of a terrible, hilarious alternate history plot:

Make Octavian a couple years younger, stab Caesar as usual, and whoops Antony is now legally responsible for the world's evilest 15-year-old. Will Antony embezzle Octavian's inheritance? Will Octavian murder Antony without getting caught? Will Fulvia drag Antony, Octavian, Cicero, Brutus, and Cassius into the world's most awkward dinner party, which is of course crashed by Dolabella?? Not to mention Agrippa, Maecenas and Salvidienus embarrassing Antony in public with the pranks only bored teenagers can invent!

I need a sitcom where instead of the War of Mutina/Liberators' War we get Julian family drama 30 years early, Cicero and the conspirators live, and maybe, just maybe, the republic gets back on track. Mainly because Antony and Octavian are too busy hassling each other for either to fight Brutus and Cassius.

(Excerpt from Julius Caesar and the Roman People, by Robert Morstein-Marx, p. 566)

#jlrrt reads#hey new fanfic au#octavian#mark antony#julius caesar and the roman people#robert morstein-marx#alternate history#for bonus points imagine that for some reason antony and octavian literally have to live together#idk maybe they claimed the same house from caesar's will and both refuse to leave#tom and jerry style attempts to kill/prank each other every day#there's buckets of dye and pies involved#both of them complain about the other to lepidus but neither lets him get a word in edgewise

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Determinism, Dice Rolls, and Dickheads

So, @sextuscansextus posed a great question the other day: "If you were going to pin the BEGINNING of the downfall of the Roman Republic on the actions of one Roman, who are you blaming?" The pedant that lives in my brain immediately started asking more questions. Not to argue, but to explore. To enjoy. To attempt a political autopsy well outside my competence.

This post is my answer: who I blame most, and why.

Had the Die Already Been Cast?

Many folks (including sextuscansextus herself) have pointed out that the end of the republic was a complex process, and blaming it on one "key figure" doesn't really work. Historians don't just talk about the individuals who shaped history, but a web of other factors: geography, economics, religion, overvalued sparkly rocks, etc.

So, how much should we blame people like Sulla or Caesar? And how much should we blame systemic forces that pushed them and other Romans to act as they did?

A pure "systems" approach looks like Jared Diamond's book, Guns, Germs and Steel. It tries to explain why some societies colonized others, using physical geography and agriculture. Individuals could still make choices, but on a large scale, the societies followed the different paths permitted by their material situations.

Or, to more bluntly, Europe was destined to colonize the Americas because cows rule and llamas drool, wheat is better than potatoes, and Europe's coastline looks like it was drawn by a spider on cocaine.

This book is, shall we say, controversial.

Apart from issues with methodology, accuracy, and possible racism, the book invokes historical determinism. Determinism is the idea that events are inevitable: your behavior is determined by the state of your brain, your brain's state is determined by your genetics and environment, and every person is equally ruled by those factors. Free will is as nonexistent as Mark Antony's underwear.

Determinism Lite™️ might allow for individual free will, but still frames big shifts like the fall of the Roman republic as inevitable. Or, you might say it became inevitable after a certain event set it on the course to destruction. I think this is what sextuscansextus' question is really getting at. The point in Roman history when you say, "This is where it went wrong," influences who you think doomed the republic, and how you judge the leaders who followed.

But was it doomed? Did a civil war have to happen sooner or later? If an eagle had dropped a turtle on Julius Caesar's bald spot, would somebody else march on Rome instead?

Erich Gruen and Robert Morstein-Marx have other ideas.

Lucky Bastards and the Doomsday Clock

In The Last Generation of the Roman Republic, Erich Gruen asks: What was happening in Roman politics between 80 and 49 BCE? What changed, and what stayed the same? He catalogues every election, trial, law passed or blocked, military mutiny, incestuous clusterfuck - the detail is both impressive and mind-numbing. Then he compares it all to previous decades, and concludes...that in 50 BCE, the republic was not falling apart.

"But how can that be?" you may ask. "Look at everything that went wrong! Even the Senate house burned down!"

Gruen isn't saying there weren't crises during this time. What he's saying is that they don't reflect a fundamental decay in republican institutions, or mean the republic couldn't put itself back together. For instance, the burning of the Senate was followed by troops being called in to restore order and hold a trial for Clodius' murder, and Rome was then at peace for three years until Caesar invaded - for completely unrelated reasons. The two conflicts are not actually linked. And positive developments occurred in between them, but are usually overlooked by historians trying to explain why things went wrong.

Gruen's argument is multi-layered, and I can't summarize it all here. But he concludes that the Roman republic could have potentially survived much longer, if not for the personal, not systemic, conflict between Caesar and Pompey in 50 BCE. If he's right, then we can't say any of Caesar or Pompey's predecessors "doomed" the republic.

Robert Morstein-Marx takes Gruen's argument further. In Julius Caesar and the Roman People, he explores the lead-up to Caesar's civil war, and finds miscommunication, politicians waffling back and forth, and several times war was almost averted. Even after Caesar crossed the Rubicon, he and Pompey nearly reached a peace deal. And several times Caesar was almost killed in battle, only escaping through pure luck.

Neither the civil war nor Caesar's dictatorship were inevitable. So besides "important people" and "systemic factors," Morstein-Marx names another force of history: sheer, bloody chance.

Not all historians agree with Gruen and Morstein-Marx. But let's suppose that at some point, the republic was in danger, yet there was a chance of restoring it to its prior health and stability. Whether you think there was a 90% or 5% chance of saving the republic in 52 BCE, try thinking in terms of probabilities, not a path of cause and effect.

Let's call this the "probability model." There are people and events who raise or lower the republic's stability, going all the way back to its founding, when Lucius Brutus' sons tried to overthrow it. It's like the Doomsday Clock, which doesn't measure how long humans have before destruction, but our risk of things blowing up in our face. The Doomsday Clock can go forward (riskier) or backward (safer), just like the Roman republic could start stabilizing in 52-50 BCE before a civil war destabilized it again.

In this model, we can't really say there is a "beginning of the end," or one person who started it. There was a series of events during which the republic collapsed, but they didn't necessarily cause each other, or all stem from a single source. You might as well ask which raindrop flooded your house.

But don't worry. We can still throw rocks at a guy who's been dead for 2000 years. We just have to rephrase the question a little.

What Was the Biggest Hit?

We can't say one man caused the republic to irreversibly decay, but we can say some men struck bigger blows than others, or struck it at a worse time.

Personally, I really like Gruen and Morstein-Marx's analyses. I agree with Gruen that the republic had reasonable prospects to survive in 51 BCE, and with Morstein-Marx's argument that Caesar and Pompey could have resolved their differences peacefully. But I think the republic's chances dropped dramatically after Caesar invaded Italy and Pompey fled to Greece - perhaps from 80% to 30%, if you'll forgive me for pulling numbers out of my ass. And the odds got worse as the conflict went on.

For the next 20 years, Rome was in a nearly constant state of civil war, autocracy, or both. It's hard to overstate how damaging both of those were to every level of society. Men like Augustus grew up without having ever seen a healthy republic, and many of the men that knew how to run one were killed. Public offices went unfilled, infrastructure decayed, mouths went unfed. Even if preserving the republic wasn't impossible yet, it became far, far more difficult. So if we're gonna point fingers, I think we should be looking at 50-49 BCE.

A lot of politicians fucked up at that point. You can argue that Curio drove a wedge between Caesar and Pompey, that Cato shut down the peace negotiations, that Marcellus declared war first, that Caesar started the war for real, and that Pompey tried to play both sides and it blew up in his face. It's possible that if any of these men had acted differently, no war would have happened. But if I had to pick one man to blame the most...

The Motive Matters, Too

Let's go back to that point about systems versus individual agency. How far were these politicians' choices constrained by their culture and environment? It doesn't change how badly they fucked up, but when it comes to blame, I'm harsher on people who choose evil of their own free will, rather than because they feel pressured into it.

In De Bello Civili, Caesar tells us why he defied the Senate for a year and invaded his own country. He tells us he wanted to protect the tribunes' rights, but the tribunes only came to him days before he crossed the Rubicon, so it doesn't explain why he let the situation get so dire in the first place. For that, we must look at his other stated reason: dignitas.

He wasn't afraid of a trial, assassination, or the anger of his soldiers. He did it for his pride, public image, honor, whatever you want to call it. And he put that pride before the lives of his countrymen and the safety of his country.

Now, the ancient Romans might have thought dignitas was a better reason than we do, but we can't blame Caesar's actions on Roman culture, either. 140 years earlier, Rome had had another great general. His name was Scipio Africanus. His career shares many similarities with Caesar's, and he was likely one of Caesar's heroes. But Scipio never turned his power against his country. He actually turned down being dictator and perpetual consul, and when his enemies politically cornered him, he accepted exile rather than forcing an ugly, drawn-out fight. Despite that embarrassment, he remained a legend through Caesar's time and to this day.

Or perhaps you want an example closer to Caesar's era and situation. We have one: Lucullus, whom Caesar actually served under at Mytilene. 16 years before Caesar crossed the Rubicon, Lucullus was spurned for a triumph for his campaigns. He waited three years, living outside Rome all that time, before he finally got one. But during that time he demobilized his army and respected the Senate's laws, no matter how petty and personally motivated they were against him. He did not use the military as a threat.

When push came to shove, Scipio and Lucullus put the good of the republic before their own careers. Caesar did not. He chose to defy the Senate and take up arms against his countrymen, knowing full well he had other options available.

I blame Caesar not only for the size of the blow he inflicted on the republic, but also because the blow was so preventable, if only he had been a better man.

#holy shit this got long#it was super fun to write though!#gods i love talking about this stuff#jlrrt essays#historiography#roman politics#julius caesar#caesar's civil war#scipio africanus#robert morstein-marx#erich gruen#guns germs and steel#jared diamond#julius caesar and the roman people#the last generation of the roman republic#lucius licinius lucullus

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

My new favorite running joke in Julius Caesar and the Roman People is this one Pompeian commander who couldn't fight his way out of a paper bag, so Caesar keeps capturing him, letting him go and tells him "Say hi to Pompey for me!" every time.

(Robert Morstein-Marx, Julius Caesar and the Roman People, p.429)

#jlrrt reads#julius caesar and the roman people#robert morstein-marx#caesarhell#julius caesar#vibullius rufus#caesar's civil war

42 notes

·

View notes