#seaforth highlanders

Photo

“An impressive photograph of Lieutenant N. Naillie-Stewart of the Seaforth Highlanders who has been held for a month in the Tower of London as a "secret prisoner" on charges of violating the Official Secrets Act of Great Britain. The prisoner (with arrow pointing towards him) is seen here taking his daily exercise walk around the grim old walls of the Tower of London escorted by an officer of the Coldstream Guards.”

- from the Kingston Whig-Standard. March 2, 1933. Page 12.

#norman baillie-stewart#official secrets act#tower of london#army officer#lord haw haw#seaforth highlanders#british army#military plans#selling state secrets#treason#military prisoner#british history#great depression in the united kingdom#nazi sympathizer

1 note

·

View note

Text

Troops of the 72nd Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders of Canada) halted in the snow. Bazentin, February 1917.

#ww1#history#black history month#ww1 stories#ww1 portrait#The Great War#The First World War#1918#1917#1916#1914#Battle of the Somme

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 13th April 1719 a small Spanish force, believing itself to be part of a much larger invasion planned for England to return the Jacobites to power, landed in Loch Duich, east of the site of what is now Kyle of Lochalsh.

The little known 'Little Rising’, saw a force of 300 Spanish soldiers land and combine with less than a thousand Highlanders, under George Keith, the 10th Earl of Marischal, William Mackenzie, the 5th Earl of Seaforth Lord George Murray and John Cameron of Lochiel.

The plan had been hatched by King Philip of Spain and Italian Cardinal Alberoni as a diversion to help in the campaign to restore Spanish power and territories ceded to the British following the Treaty of Utrecht. The Spanish force should have been much larger, but much of it had been destroyed by a storm. Added to this Highlanders did not join the Jacobites in the expected numbers, However, the Jacobites made their base at Eilean Donan Castle and intended to capture Inverness. Unfortunately, Hanoverian ships shelled the castle and the only battle was at Glen Shiel two months later when the Jacobites were defeated by a Government army led by General Joseph Wightman.

This uprising is often overlooked, the only “major” action was on June 10th at the Battle of Battle of Glen Shiel, more of that in a couple of months.

A wee added note to this, it was during this time that Eilean Donan was destroyed by Government ships bombarding it the ruined castle was abandoned until 1912 when it was purchased by Lieutenant-Colonel John MacRae-Gilstrap. Rebuilding was undertaken between 1914 and 1932 and it was at this time that a bridge was built to link the island to the shore. The pics shows how the castle looked in the two centuries between these events and the restoration, and the ruin, as it was.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

“MacAdams Shovel”

A unique field shovel designed by the Canadian Army during WWI, supporting appearance - Seaforth Highlander, Canada

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Private Ralph Forrester of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, 1st Canadian Division, places flowers on the grave of his brother, who was killed in action at Ortona, Italy. 16 January 1944

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Georges VI inspecting Seaforth Highlanders 1944

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Men (and a dog) of the Seaforth Highlanders rest in a trench, near La Gorgue, France, August 1915. Note how the bayonets are fixed, possibly pointing to the staging of the picture, as in 95% of the occasions

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queen inspecting the 7th battalion Seaforth Highlanders in 1955.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

@moonydabest and @whatsorryiwasntlistening FAN-FUCKING-TASTIC HELL YEAH OFFSHORE OIL RIGS. OKAY S O. I’m gonna talk about the sinking of one of them since that’s probably the most interesting (however also very tragic) things. Anyways so it’s this semi submersible oil rig named the Ocean Ranger, owned by a company called ODECO. It was 267 km east of St. John’s, Newfoundland and drilling in the Hibernia oil field. So for context this rig was about to encounter a massive storm that it honestly only should’ve sustained minor damage from. There were two smaller rigs nearby that weathered the storm with minimal damage despite it being a very intense storm. So by all means the Ocean Ranger should’ve been completely fine.

However the crew wasn’t educated on safety precautions which is a shortcoming on ODECO’s part and the rig was also not prepped with proper survival equipment. The issues started when (once again lack of safety education) the crew didn’t close the hatches that cover the windows in the ballast control room. The control room is only around 28 ft above the water and during storms there’s hatches that should be closed during storms as the glass can be broken and flooded, causing damage to the control board which is exactly what happened. (Also ballasts are what make the rig buoyant and controls how much water can be in and out of the ballasts at a time, lowering or heightening the rig depending on how much water is let into them.)

The controls sustained damage but due to the crew being inexperienced and uneducated they didn’t realize this was such an issue. They had shut off power to the controls for a time but then (assumed for repairs) gave power back to the room, short circuiting the board and causing the ballasts to open and take on water. This caused the rig to list (lean) heavily 15 degrees to the side, which for an oil rig is a massive deal.

The rig had correspondence with multiple rigs and boats during this but it didn’t convey any signs of emergency until later. At 00:52 (local time) a mayday call was sent out and the Rangers support boat, the Seaforth Highlander set towards the rig. It was about 8 miles away. The two nearby rigs also dispatched their own nearby support boats to the Ranger for assistance and land crews were notified but due to the severe weather, no helicopters could get off the ground at the time to help evacuate the crew who had no survival suits which could prevent hypothermia and drowning in the water.

At 1:30 AM (local time) the Ocean Ranger sent its last transmission, letting the support/standby boats, nearby rigs, and ground crews know the crew was no longer going to radio as they’d be going to lifeboat stations. There were difficulties launching the lifeboats due to the severe list of the rig but they were able to launch at least one. However the attempts by standby boat Seaforth Highlander to recover the lifeboat were unsuccessful due to the weather and that the ship was not made to rescue anything from the water. A helicopter could only be launched to help at 2:30 AM but by this point in time the crew inside the lifeboat had been unable to be recovered by the standby ships who’d arrived (3 total ships as 2 supply ships arrived later) and the crew trying to tie to the larger Highlander ship has been tossed into the sea as the ropes snapped and lifeboat flipped with 20 crew members strapped inside. All succumbed to hypothermia and drowning and all 84 crew members of the Ocean Ranger rig died. The rig itself had remained upright for another 90 minutes before sinking entirely into the sea with no trace other than the buoys.

#hello yes thank you for listening#i tried to break this up a little so it’s not just a block of text since i hate reading large blocks of text with no breaks#but anyways yeah it was a tragedy and greatly impacted newfoundland at the time#there’s a memorial for it now#crow rants#tw: death#tw: drowning

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Los perros se utilizaron para desempeñar muchos roles diferentes en las trincheras de la Primera Guerra Mundial. Fueron considerados más versátiles que los caballos debido a sus habilidades cognitivas, físicas y capacidad de entrenamiento. Los ejércitos los utilizaron como perros guardianes para enviar mensajes, además de desplegarlos para instalar cables de telégrafo y localizar a los soldados heridos. En la foto, hombres escoceses del regimiento Seaforth Highlanders descansando en una trinchera con un perro durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, 1915. (en Tlaquepaque, Guadalajara) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cp0se7mP1O9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Erickson Exhibit, Seaforth Highlanders Museum, Vancouver

James Calhoun, Curator & Archivist of the Seaforth Museum in Vancouver, has overseen a fine new museum display on Arthur Erickson's early military service with the Seaforth Highlanders, including items donated from the Erickson family. Arthur joined the Seaforth Cadets before training for missions in India, British Ceylon, and Malaysia with the Canadian and British Intelligence Corps. His interest in travel and understanding other cultures never ceased after that, such that he initially pursued becoming a Canadian diplomat rather than an architect. The Erickson family is also donating Arthur’s father Oscar Erickson’s military medals and materials to the museum, which include the Military Cross, and The Order of The British Empire.

The museum is located in the Seaforth Armoury on Burrard Street, and thanks to the work of James Calhoun, Hon. Lt. Colonel Rod Hoffmeister, and Rod Bell-Irving, it has been carefully restored and transformed into a real treasure, with a great collection that's well worth visiting: https://www.seaforthhighlanders.ca/visit

Photo: Geoffrey Erickson

0 notes

Text

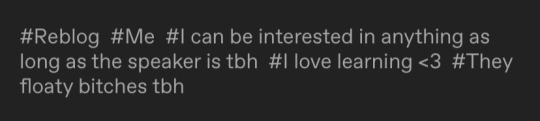

"MCNAUGHTON AIDE. - Lieut. Ian W. Bell-Irving, 23, son of Mr. and Mrs. Richard Bell-Irving, Onslow Place, West Vancouver, has been named aide-de-camp to Lieut.-General A. G. L. McNaughton overseas, according to word received here.

Lieut. Bell-Irving, a graduate of Shawnigan Lake School and King George High School, went overseas in April, 1942, to join the 1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders in England."

- from The Province (Vancouver). March 13, 1943. Page 5.

#aide de camp#overseas service#canadian corps#military officer#canadian army#seaforth highlanders#vancouver#commander in chief#canada during world war 2

0 notes

Photo

New Seaforth Highlanders British Army Let's We Forget Personalized Rug from Tagotee.net 🔥 See more: here

0 notes

Text

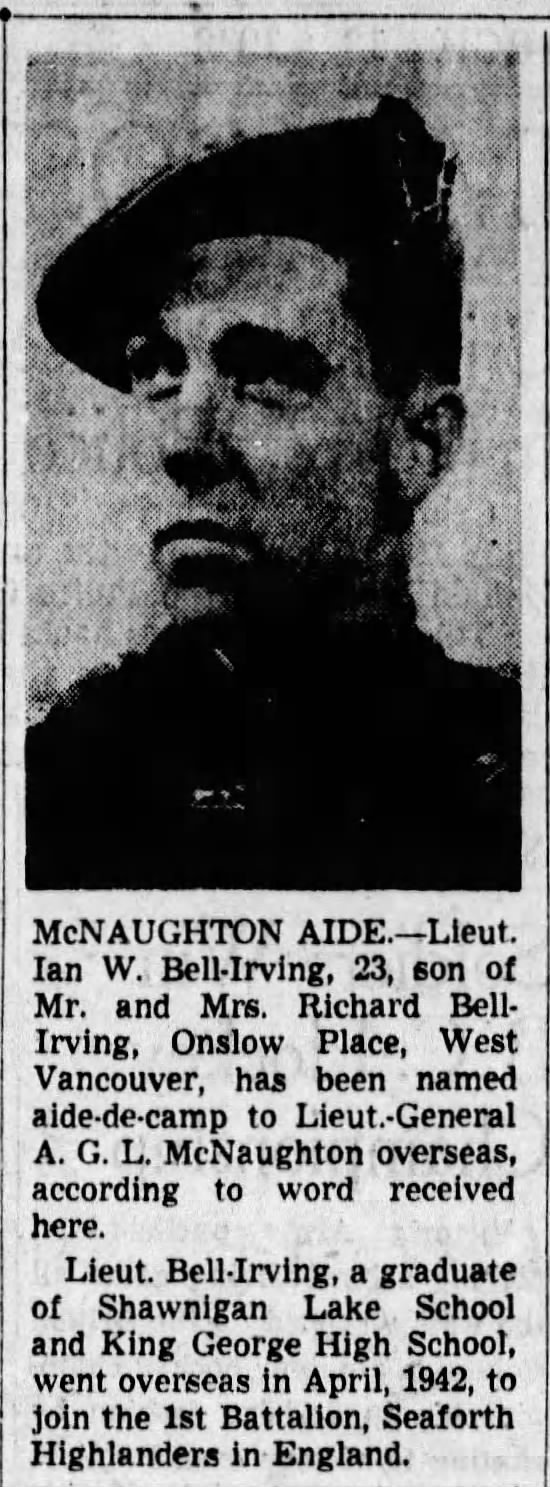

2nd February 1645 saw The second Battle of Inverlochy.

This was one of a series of stunning victories for the Royalist army led by James Graham, 5th Earl and 1st Marquis of Montrose, this battle saw him rout the Earl of Argyll's Covenating forces.

In August 1643 the Scottish Government and English Parliament signed the Solemn League and Covenant resulting in Scotland entering the war against King Charles I. In response the King appointed James Graham, Marquis of Montrose as Captain General of Royalist forces in Scotland. Although he had fought as a Covenanter commander during the Bishops War, he had opposed the subsequent power of the Presbyterian leadership under Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll. Montrose effectively mobilised the Highland forces, many of whom were opposed to Campbell, and achieved a number of rapid successes including victory at the Battle of Tippermuir the previous September and an assault on Aberdeen in October.

The Covenanter forces consisted of men drawn from Campbell's territories within Argyll and also veteran troops drawn from the Scottish army fighting in England most of whom were lowlanders. The Royalists had a core of Highlanders but their numbers were being depleted as many returned home laden with the loot they had acquired from the raided Campbell territories. However Montrose also had a large contingent of Irish, headed by General Alasdair MacColla, who had joined with the Royalist force in November 1644.

At Glencoe the army crossed the high passes into Glen Nevis, moved around the north slopes of Ben Nevis, going round Inverlochy Castle, and then continued up the Great Glen, arriving at Kilcummin to re-supply. Montroses´ army was dwindling as his highlanders continued to head home leaving him with about 1500 men. He was aware that a Covenanter army under the command of the Earl of Seaforth was waiting to confront him at Inverness. Montrose was also aware that Argyll, with a force of 3000 men, was pursuing him and was only thirty miles behind at Inverlochy. What followed was one of the greatest flanking marches in British history across some of the toughest and wildest terrain in the British Isles. Instead of marching back down the glen, Montrose decided to surprise Argyll and marched south through the mountains around Ben Nevis to mount a surprise attack.

The Montrose army spent a cold night in the open on the side of Ben Nevis. Argyll was aware that a small force was operating in the area, he did not know however that it was the entire royal army. Just before dawn on 2 February 1645, Argyll and his covenanters were dismayed at the sight that lay before them, as far as they were aware Montrose should have been 30 miles north.

Argyll did not stay for the battle, but instead he left the command of his army to his general, Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck, and retired to his galley anchored on Loch Linnhe. As seen in the pic. Auchinbreck lined up the covenanters in front of Inverlochy castle, which he reinforced with 200 musketeers to protect his left flank. In the centre he placed the Campbells of Argyll and put the lowland militias on the flanks. Unlike at Tippermuir and Aberdeen, where Montrose had defeated easily hastily conscripted and poorly trained militias, the troops he faced at Inverlochy were veterans of the war in England. Montrose lined his army up in only two lines deep to avoid being out flanked, placing his 600 highlanders in the centre with the Irish on the flanks, the right being commanded by MacColla. The fight did not start straight away and instead skirmishes broke out along the line. This is probably because Auchinbreck and his officers thought that they were only fighting one of Montrose´s lieutenants and not the man himself, believing he was still far up the glen. Just before first light, the Royalists launched their attack.

The Irish clashed with the lowlanders on both flanks and routed them while the highlanders closed with the Campbells in the centre. The Campbells broke, but their retreat to the castle was blocked by the Royalist reserve cavalry under the command of Sir Thomas Ogilvie. Auchinbreck was shot in the thigh while trying to rally his men and died shortly afterwards.

The remaining Covenanters briefly rallied around their standard, then broke and ran, trying to reach Lochaber. The small garrison in Inverlochy castle surrendered without a fight. Over 1500 Covenanter troops died, while Montrose may have only lost 250 men, the most notable being Sir Thomas Ogilvie who was killed by a stray bullet.

Montrose, through his lieutenant, MacColla, who commanded the 2000 Irish troops sent by the Irish Confederate), was able to use this conflict to rally Clan Donald against Clan Campbell. In many respects, the Battle of Inverlochy can be seen as part of the clan war between these two.

The first illustration is called The flight of Argyll from the Battle of Inverlochy, and is from 'Loyal Lochaber. Historical Genealogical and Traditionary' by W Drummond Norie, Glasgow, 1898.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Montrose in Scotland: ‘I Aim Only at Your Majesty’s Honour and Interest’

The End of the Royalist Dream

The Marquess of Montrose, portrait by Anthony van Dyck (1636). Source: Wikipedia

NASEBY MAY have permanently damaged the King’s cause in England, but the situation in Scotland was very different, where James Graham, Marquess of Montrose and his raggle taggle band of Irish Confederates, Highland rebels and Scottish Royalists, had defeated everything the Covenanters could throw at them. The Marquess’ unexpected victories had suddenly made Scotland an unlikely depository for Royalist hopes and Charles now looked to Montrose for salvation of his entire cause. Graham may have entered Charles’ northern kingdom as a folorn hope, but the exploits of this epitome of the Cavalier general were the sole bright light in the gathering darkness engulfing the King’s hopes in his war with Parliament.

In November 1644, Montrose and his Irish Confederate lieutenant, Alisdair MacColla, planned their next move. Following the sack of Aberdeen, the Royalist force had withdrawn into the Highlands to replenish its ranks through a recruitment campaign that deliberately played on clan animosities. To the Stewarts and Robertsons were added traditional enemies of the Campbells (the dominant clan in Scotland) the MacDonalds and Camerons, and MacColla’s proposed strategy took on a distinctly tribal orientation. He proposed to the Lieutenant Governor that the army launch a winter campaign deep into Campbell lands, ravaging the holdings of Archibald Campbell, the Marquis of Argyll and head of clan Campbell. Montrose was persuaded of the plan, despite its obvious logistic difficulties, because Argyll was also the leading politician in the Covenanter government, the Scottish Estates, and a successful attack on Argyll would be a victory for the King as much as it would be for clan vengeance against the Campbells. In December Montrose’s army began its march, traversing arduous peaks and inclement weather to eventually emerge in the heart of Argyll’s lands in Inverary. Argyll was caught unprepared and quite incapable of mounting a defence of his ancestral lands as the Royalist army plundered far and wide indiscriminately killing any of those they felt were guilty of rebellion, were prominent supporters of the Estates, or could be identified as Campbell notables. At Kilcumin, Montrose received word that Argyll’s army was moving north to attack the Royalists, with the intention of trapping them between his force and that of Mackenzie of Seaforth. Montrose decided to force the issue and led his 1,500 strong army on an extraordinary forced march day and night, over snow covered mountains and outflanked Argyll’s force, falling on the Covenanters at Inverlochy on 1st February 1645, taking the Campbell force entirely by surprise. Although outnumbered by two to one, the clansmen charged into the body of their opponents and put them to flight. Over half the Covenanter army was killed in the battle or its aftermath, and its commander Sir Duncan Campbell, doomed by his surname, was executed in cold blood by MacColla after the battle. Argyll himself escaped the slaughter, having previously dislocated his shoulder and had therefore boarded a ship anchored off the coast to recover: he advisedly fled by sea. The stunning victory at Inverlochy put Montrose, and by extension, the Royalist cause, in charge of the whole of the west Highlands.

The scale and nature of the defeat at Inverlochy shocked the Covenanter leadership, leading some to characterise Montrose’s success as being down to divine providence. Meanwhile Montrose marched to the north east, wishing to rouse the powerful Gordon clan to the King’s banner, with the intention of then launching an invasion of Lowland Scotland - heartland of Covenanter support - and onwards into England to join Charles. By this stage, William Baillie, one of the victors of Marston Moor, been summoned back north of the border by the Scottish Estates. Wary of the fighting skill of the Highlanders, the experienced Baillie did not initially seek battle, instead he manoeuvred his forces to block Montrose’s march either north east or south. As summer 1645 approached many of the Royalist army’s clansmen, bored with the lack of fighting and plunder, began to desert, once again depleting Montrose’s and MacColla’s numbers. Covenanter commmander, Sir John Hurry, had meanwhile moved into Gordon lands to pre-empt Montrose’s advance there. Undaunted, Montrose moved his small force at pace to support the Gordons and met Hurry’s force outside the village of Auldearn on 8th May. The resultant battle was a confused affair, fought on boggy ground with Montrose successfully fooling Hurry into thinking his army was bigger than it was. The battle was closely fought, but ultimately, ill discipline on the part of Hurry’s infantry led to a dissolution of the Covenanter line and flanking attacks from Montrose’s cavalry led to its collapse. The Covenanter army was destroyed, with 2,000 killed. Auldearn may have been a somewhat fortunate victory for the Royalists but it was no less devestating for the Covenanters than had been Inverlochy.

One of the main benefits of this victory was an immediate influx of new supporters into the Lieutenant Governor’s army, attracted to what seemed to be the new dominant force in Scotland. The Scottish Estates, now decidedly worried, insisted that Baillie engage Montrose and destroy this Irish Catholic insurgency once and for all before it turned into a full scale Highlands Royalist conquest. Baillie remained wary, particularly as the Royalist army was now reinforced with its new recruits, but he eventually drew his army up for battle at Alford on the banks of the River Don on 2nd July 1645. Montrose had drawn up his own forces in disguised positions and a feinted retreat proved too tempting for Baillie who sent his cavalry in pursuit across the bridge that forded the river. The Gordon foot and horse rose to meet them and in the ensuing melee, the Covenanter cavalry and infantry were routed. Again no quarter was given by vengeful Gordon clansmen whose laird, Lord Gordon, had been killed in the fighting. Over a thousand Covenanter soldiers were killed, the survivors retreated in disarray and Baillie offered his resignation to the Estates. This was refused and Baillie led a further force of 6,000 men to engage Montrose again, anxious to defeat him before MacColla returned with more Highlands reinforcements. The two sides met at Kilsyth on 14th August and once more Graham was triumphant, inflicting on Baillie an arguably bigger defeat than he had suffered at Alford. There was now no Covenanter army of any size to oppose the Royalists in Scotland. Montrose, having entered the country with just two followers less than two years ago, was now effectively its conqueror.

Montrose moved south, occupying Glasgow on 16th August. Edinburgh surrendered soon after and MacColla moved into Ayrshire to subdue Covenanter and Campbell forces there. Against all odds, Montrose appeared to have won Scotland for the King and he summoned a Scottish Parliament to take place on 20th October. However, Montrose’s triumph was illusory. He was incapable of securing the support of the implacable Presbyterian Church or their Lowland congregations. Equally, his army of Highlanders and Irish were getting restless, wishing to head to home to enjoy their plunder and rejoin their families. The notion that Montrose could impose loyalty to Charles on Lowland Scotland with an occupying force of outlanders and Catholics, was always far fetched. Realising this, Montrose decided to join up with Charles and headed with his depleted army to the English border. This too was a folorn plan: not only did Covenanter forces hold the north of England for the Committee of Two Kingdoms, but David Leslie was leading a strong force of 8,000 men to head the Lieutenant Governor off. On 12th September, unaware of the proximity of Leslie’s army, Montrose made camp at Philiphaugh. With lax lookouts and incomplete defences, the Royalists were ill prepared for Leslie’s surprise assault at dawn. Although his men fought bravely, they were surprised and outnumbered. Within an hour, Montrose’s last army was finally defeated. The vengeful Presbyterians ensured there would be no Royalist resurgence. The captured clan leaders were summarily executed and all Irish prisoners were massacred in an episode of religious inspired atrocity. Montrose escaped the disaster and sought refuge in the Highlands, hoping he could raise another army and repeat his extraordinary run of victories; he still had hopes of uniting with the King, but it was not to be. Just as Naseby had dashed Royalist hopes in England, so Philiphaugh ended the dreams of Royalist recovery in Scotland.

The irony of the ultimate failure of Montrose’s romantic adventure is that a desperate Charles would now look to the Scots to support his hopes, the very Covenanters who had fought him since the 1630s and finally destroyed Scottish Royalism on the field of Philiphaugh.

#english civil war#charles i of england#british history#marquess of montrose#battle of philiphaugh#civil war in scotland

1 note

·

View note

Text

Private Stanley Davis of 5th Seaforth Highlanders rides a captured German pack mule branded with a swastika. Sicily, 16 August 1943

19 notes

·

View notes