#the late Mycenaean period which was followed by the Bronze Age collapse

Text

The fact that the Volturi leaders were born in the Bronze Age 🤯

#the late Mycenaean period which was followed by the Bronze Age collapse#then the dark age#then the period we know as Ancient Greece#volturi#volturi coven#the volturi coven#the volturi#aro volturi#marcus volturi#caius volturi#twilight volturi#twilight saga#twilight renaissance#twilight renewal#twilight resurgance#twilight revival

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

“According to Michael Hudson, echoing Trigger, the evidence shows that in Mesopotamia “private property” was introduced from the top and gradually flowed downwards.

The contrast between public usufruct-yielding lands and family-held subsistence lands is reflected in the fact that no terms for “property” have been found even as late as the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1600 BC in Babylonia). The closest relation is “domain of the Lord,” evidently the first land organized to produce a systematic usufruct or land rent. Rentier income thus seems to have originated in the public sector. Only after private individuals adopted public-sector modes of enterprise to produce regular surpluses of their own could taxes as such be levied. Indeed, it was the private appropriation of the land and large workshops that brought in its train a reciprocal liability for paying taxes.

The privatization process started with the ruler’s family, warlords and other powerful men at the top of the emerging social pyramid. After 2300 BC, Sargon’s heirs are found buying land from the families of subject communities (as documented, for instance, in the Stele of Manishtushu). As palace rule weakened, royal and public landholdings came to be privatized by palace subordinates, local head-men, creditors, and warlords. Land formerly used to support soldiers was charged a money-tax, which governments used to hire mercenaries.89

And elsewhere:

THREE types of landed property emerged in southern Mesopotamia’s cradle of enterprise: communal land (periodically re-allocated according to widespread custom); temple land endowments, sanctified and inalienable; and palace lands, acquired either by royal conquest or direct purchase (and often given to relatives or other supporters).

Of these three categories of land, “private” property (alienable, subject to market sale without being subject to repurchase rights by the sellers, their relatives or neighbours) emerged within the palace sector. From here it gradually proliferated through the public bureaucracy, among royal collectors and the Babylonian damgar “merchants”. However, it took many centuries for communal sanctions to be dissolved so as to make land alienable, forfeitable for debt, and marketable, with the new appropriator able to use it as he wished, free of royal or local communal oversight….

(1) The first real “privatizer” was the palace ruler. Rulers acted in an ambiguous capacity, treating royal property — and even that of the temples, which they took over in time — as their own, giving it to family members and supporters. In this respect “private” property, disposed of at the discretion of its holder, can be said to have started at the top of the social pyramid, in the palace, and spread down through the royal bureaucracy (including damgar “merchants” in Babylonia) to the population at large….

(2) A derivative form of private ownership developed as rulers gave away land to family members (as dowries), or companions, mainly military leaders in exchange for their support. The recipients tended to free themselves from the conditions placed on what they could do with the land and the fiscal obligations associated with such land. As early as the Bronze Age, such properties and their rents are found managed autonomously from the rest of the land (viz. Nippur’s Inanna temple privatized by Amorite headmen c. 2000-1600 BC). Likewise the modern system of private landholding was catalyzed after England’s kings assigned property to the barons in exchange for military and fiscal levies which the barons strove to shed, as can be traced from the Magna Carta in 1215 through the Uprising of the Barons in 1258-65.

Much as modern privatization of the national patrimonial assets often follows from the collapse of centralized governments (e.g. in the former socialist states and Third World kleptocracies), so in antiquity the dynamic tended to follow when centralized palace rule fell apart. Royal properties were seized by new warlords, or sometimes simply kept by the former royal managers, e.g. the Mycenaean basilae, not unlike how Russia’s nomenklatura bureaucrats have privatized Soviet factories and other properties in their own names.

(3) A third kind of privatization occurred in the case of communal lands obtained by public collectors and “merchants” (if this is not an anachronistic term used for the Babylonian tamkaru), above all through the process of interest-bearing debt and subsequent foreclosure. Ultimately, subsistence lands in the commons (or more accurately the communally organized sector, which often anachronistically is called “private” simply because it is not part of the public temple-and-palace sector), passed into the market, to be bought by wealthy creditors or buyers in general.90

So the Lockean model of individual private appropriation is largely an ahistorical myth. Private property in land has been the result, rather, of forced privatization by states, sometimes in concert with landed nobilities.

In fact, anything closely resembling the classical liberal ideas of private individual property — whether obtained by “homesteading” or not — appeared in relatively few places until the modern era (most notably ancient Rome and late medieval Europe). So it’s probably not coincidental that libertarian defenses of private property as natural and ubiquitous typically start with Greek and Roman law and leap from there to the common law of property as explicated by Blackstone (although even in these cases their mythology requires ignoring the robbery by which such forms of property came about).91 And while Roman legal conceptions of property to some extent foreshadowed modern private property, and have been consciously drawn on in its development, nevertheless — as Widerquist and McCall quote Chris Hann arguing — “in fact the great bulk of land in the ancient world was farmed by peasant smallholders and transmitted within their communities according to custom. Most historians would argue that the same was true under feudalism.”92

— Kevin Carson, Capitalist Nursery Fables: The Tragedy of Private Property, and the Farce of Its Defense

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

6,000 Years of Murder – Part Four: There Goes the Neighbourhood

Tim: The Wicked + The Divine #36 finally gave us a definitive list of every damn Recurrence that has occurred since Ananke first started exploding heads, so we thought we’d take a walk through the annals of history and provide some context for what was happening at the time. Welcome to 6,000 Years of Murder.

In this entry, we hit the halfway mark in our voyage through history, as we found a modern religion, celebrate the most baller of all the Pharaohs and watch thousands of years of progress get flushed into the Mediterranean Sea...

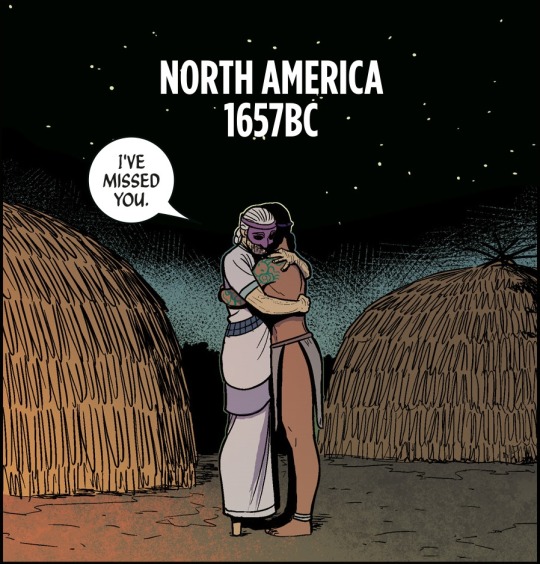

1657BC – North America

It’s time for another one of our rare pre-Columbian trips to North America, and around this point, that means we’re probably in the area of modern-day Louisiana, checking out some mounds. The Poverty Point culture (an unfortunate name, but historians are a cruel and unusual lot) were a group of indigenous peoples who occupied the lower Mississippi Valley from around 2200BC to 700BC, building settlements in over a hundred sites and creating a large trading network throughout what is now the eastern United States. Mainly hunter-gatherers, they are descended from the tribes that passed through Wrangel Island and down into the continental US.

This time would have been the peak of Poverty Point culture, with work on their eponymous largest settlement just beginning. It would go on to take up 910 acres, and has been described as the “largest and most complex Late Archaic earthwork occupation and ceremonial site found in North America”. Exactly what Poverty Point was used for is heavily debated – some think it was a settlement or trading centre, while others point to its concentric rings of semi-circular mounds as suggesting a ceremonial function.

1565BC – Northern China

Our last trip to Northern China saw the Xia dynasty emerging around Erlitou and the Yellow River. As we check back in, the Xia are on their way out, about to be replaced by the Shang dynasty, who will rule for around 600 years. The Shang provide us with some of our first examples of Chinese writing, and oversaw several important developments, including large-scale production of bronze; a foundation of a powerful standing military; artistic works in jade, bone and ceramic; and the construction of large walled palace complexes.

The Shang are the earliest dynasty we have concrete archaeological evidence for, with earlier dynasties existing in the weird space between oral history and folklore. Not only do we have evidence, but we have accounts of the Shang in classic Chinese literature like the Book of Documents, the Bamboo Annals and the Records of the Great Historians (although these were all written at least 1,000 years later). Sidenote: the Chinese remain great at naming things.

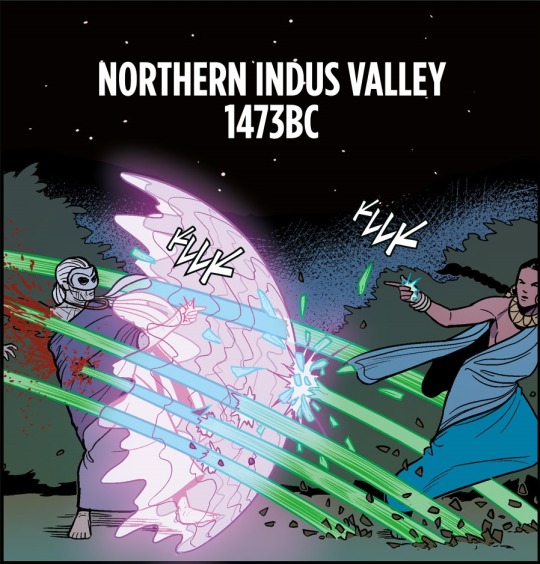

1473BC – Northern Indus Valley

Our old friend the Indus Valley Civilisation is no more, I’m afraid. It dissipated around 200 years back, when consistent drought and aridification made agriculture more difficult, and urban settlements became harder to support. As it broke up, the people of the Indus Valley Civilisation scattered. Many headed east, while others remained, mingling with incoming Indo-European and Indo-Iranian tribes. For the next 1,000 years or so, the Indus Valley will return to a more tribal, pastoral model without a strong urban centre.

However, who needs an urban centre when you’ve got RELIGION?! Not just any religion, either – this time is known as the Vedic period, because it’s when the four central texts of Hinduism will be written, starting around this time with the Rigveda, a collection of 1,028 Sanskit hymns and 10,600 verses. Discussing cosmology, the nature of god and the virtues of charity, the Rigveda is one of the oldest extant texts in any Indo-European language, and a cornerstone of a religion that boasts 1.15bn followers today. If we’re trying to correlate Persephone fighting back with particularly momentous periods in history, the Vedic period – despite being largely pastoral – certainly qualifies.

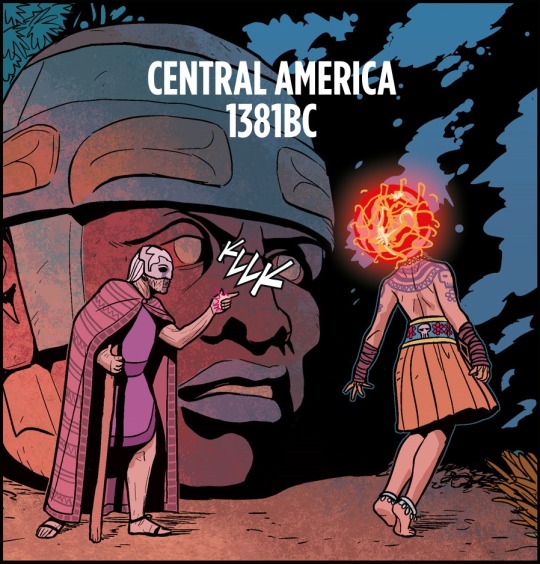

1381BC – Central America

It’s Central America. There’s a big head in the background. It must be OLMEC TIME. One of the earliest known major civilisations in Mesoamerica, the Olmecs were found in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco, between 1500BC and around 400BC. As the first major culture to emerge in the area, the Olmecs sort of set the template for civilisations that would follow in the area, and while that template included a complex writing system, the concept of zero, advanced calendars and a great ballgame, it also involved ritual bloodletting and, quite possibly, human sacrifice.

Let’s talk about the big heads. No known pre-Columbian texts explain their origin or purpose, and while only 17 have been unearthed to date, they have become a well-recognised symbol of the Olmecs. Once theorised to be popular ballplayers, they are now generally accepted to be portraits of rulers, although possibly dressed as ballplayers, like when Putin rides around shirtless on a horse. No two heads are alike, and they were carved from huge single blocks or boulders of volcanic basalt, with the finished products ranging in size from 4'10″ to 11' tall. Those are some big-ass heads.

1289BC – Egypt

Oh Egypt, we couldn’t stay away too long, especially when you’ve been so busy. The Middle Kingdom is long over and it’s time for the New Kingdom. See if you can recognise some of the names that have come and gone while we were away. Amenhotep. Nefertiti. Tutankhamen. But if they weren’t important enough to bring us back, what could possible be around the corner? It’s only ya boi Ramesses II, aka Ramesses the Great, aka Ozymandias, Great Ancestor, king of kings, the greatest, most celebrated and most powerful pharoah of the Egyptian civilisation.

The 19th Dynasty has just begun in Egypt, and at age 14, Ramesses has been appointed Prince Regent by his father, Seti I. Within 10 years, he’ll have taken the throne, and he’ll reign for around 70 years. During that time, he’ll engage in countless military campaigns, retaking territory from the Nubians and Hittites. He’ll also sign the first recorded peace treaty, oversee a period of unprecedented construction throughout Egypt, and move the capital from Thebes to a new city named after himself that includes huge temples and a zoo. Microscopic inspection of his mummified body, which was originally buried in the Valley of the Kings, suggests he was a redhead, adding to his similarities to Cheryl Blossom.

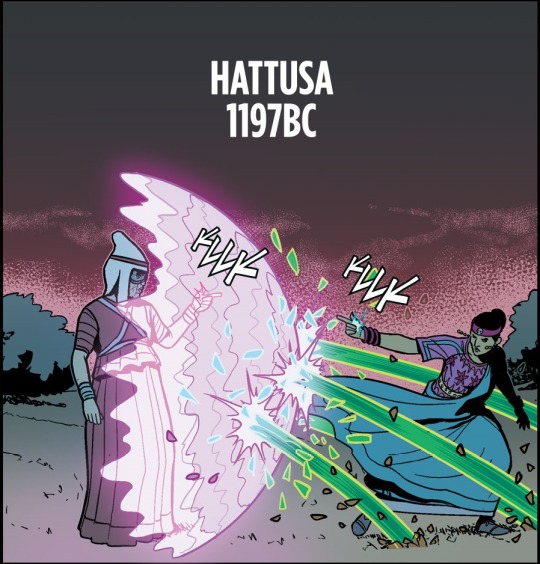

1197BC – Hattusa

We’ve mentioned that Ramesses II was going to war with the Hittites – what’s their deal? Well, at this point, their kingdom is in decline, following a lengthy war with Egypt and the rise of the Assyrian Empire. But at their height in the mid-14th century BC, they encompassed Anatolia (aka modern day Turkey), Upper Mesopotamia, the Levant and chunks of modern day Egypt. The capital city Hattusa is located in central Anatolia, surrounded by rich agricultural lands and small woods that provided wheat, barley, lentils and timber, as well as grazing lands for sheep.

During the reign of the most successful Hittite monarch, Suppiluliuma I (circa 1344-1322 BC), large walls were erected around the city that are still visible today. The city had an inner and outer section, with the inner area occupied by a citadel with large administrative buildings, temples and a royal residence, all decorated with elaborate reliefs depicting warriors, sphinxes and lions. Unfortunately, just as Ananke perfects her force field, here comes the Bronze Age Collapse, which will result in much of the city being abandoned and falling into ruin.

1106BC – Greece

That long mix of a fart noise and a scream you can hear is the Late Bronze Age collapse. In between 1200-1150BC, the area surrounding the Mediterranean undergoes huge upheaval, shifting from the city-state and palace economy that has characterised the region back to small isolated villages. Wave goodbye to the Mycenaean Greeks (who just won the Trojan War finally), the Kassites in Babylon, the Hittites and the Egyptian Empire. In a 50-year span, almost every major city between Pylos in Greece and Gaza in the Levant will be violently destroyed.

What the hell caused all this chaos? There are a variety of theories, including climate change, drought, a volcanic eruption, changes in warfare, the rise of the Iron Age and a general systems collapse that encompasses all these things plus untenable population growth and soil degradation. Whatever the cause, the result is a complete shift in terms of power in the area. While Assyria and Elam will survive past the main period of collapse, they too soon shrink and fade. The Iranian people from Central Asia and the Eurasian Steppe will travel southeast, displacing the Kassites and Hurrians to become the Persian Empire, while following the Greek Dark Ages, this area will eventually re-emerge into the Classical Greek period with its many steps and columns.

1014BC – Central China

While the Middle East is wondering what the hell happened, China is continuing to kick ass and take names. The Shang dynasty has come to an end, and been replaced by the Zhou dynasty, which will last longer than any other period of Chinese history, from 1046 to around 250BC. The period will see Chinese bronzeware-making at its peak, and the written Chinese script evolve from a very basic form to something close to its modern version. The Zhou dynasty is often compared to feudal Europe, with a complex system of peerage ranks and intensive agriculture carried out by serfs on land owned by nobles.

The first half of the Zhou dynasty is called Western Zhou, and begins with King Wu of Zhou overthrowing the Shangs at the Battle of Muye. Wu died shortly after and, with his son too young to rule, his brother the Duke of Zhou took command, stamping out civil wars and rebellions, conquering more territory and establishing the Mandate of Heaven, a sort of two-for-one sale that combines the divine right of kings with manifest destiny. All this upheaval and authoritarian rule is clearly approved by Ananke, who has perfected her Double Click Technique when it comes to taking out Persephones.

Like what we do, and want to help us make more of it? Visit patreon.com/timplusalex

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

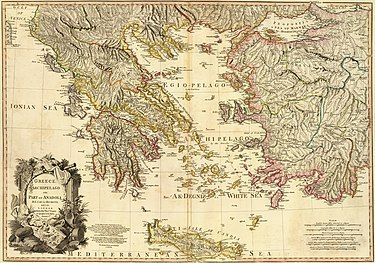

Ancient Greece was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (c. AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically related city-states and other territories—unified only once, for 13 years, under Alexander the Great's empire (336-323 BC). In Western history, the era of classical antiquity was immediately followed by the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine period.

Roughly three centuries after the Late Bronze Age collapse of Mycenaean Greece, Greek urban poleis began to form in the 8th century BC, ushering in the Archaic period and colonization of the Mediterranean Basin. This was followed by the age of Classical Greece, from the Greco-Persian Wars to the 5th to 4th centuries BC. The conquests of Alexander the Great of Macedon spread Hellenistic civilization from the western Mediterranean to Central Asia. The Hellenistic period ended with the conquest of the eastern Mediterranean world by the Roman Republic, and the annexation of the Roman province of Macedonia in Roman Greece, and later the province of Achaea during the Roman Empire.

Classical Greek culture, especially philosophy, had a powerful influence on ancient Rome, which carried a version of it throughout the Mediterranean and much of Europe. For this reason, Classical Greece is generally considered the cradle of Western civilization, the seminal culture from which the modern West derives many of its founding archetypes and ideas in politics, philosophy, science, and art.

0 notes

Text

Nikos Deja Vu - The Return of Heracleidae (or the Dorian Invasion) Greece

The Return of Heracleidae

The Dorian invasion

The Dorian invasion, sometimes called the Dorian migration (Greek: Κάθοδος των Δωριέων), which took place ca. 1100 BC, describes the descent of the Hellenic Dorian tribe, from area north of the Caspian Sea into mainland Greece and Peloponnesus as well as the islands of the Aegean Sea.

Considered as an invasion, the advent of the Dorians is generally advanced to explain the swift collapse of Mycenaean civilization in ancient mainland Greece.

Peloponnesian cities that the Dorians invaded include Corinth, Olympia, Sparta and Mycenae. Many archaeologists attribute the destruction of Mycenae, a pivotal Mycenaean city, to these invading Dorians.

Concurrent effects are the disruption of long-distance trade and possibilities of civil war and natural disaster, as well as the colonisation of islands in the Aegean sea and the west coast of Asia Minor.

The Dorian invasion was partly responsible for the subsequent Greek Dark Ages. The written record is nonexistent; the Dorian migration is documented in the mute archaeological record: widespread burning and destruction of Bronze Age sites both in Crete and the mainland of Greece, many of which were reduced to villages or abandoned, and the introduction of iron-working ended the Bronze Age in the Aegean.

Who are the Dorians

The Dorians were one of the ancient Hellenic tribes acknowledged by Greek writers. Traditional accounts place their origins in the north, north-eastern regions of Greece, ancient Macedonia and Epirus, whence obscure circumstances drove them south into Attica and the Peloponnesus, to certain Aegean islands, and to the SW coast of Asia Minor. Late mythology gave them an eponymous founder, a certain "Dorus", son of "Hellen", the mythological patriarch of the Hellenes.

Beginning about 1150 BC, the Dorians invaded the Greek mainland, the Peloponnesus, Crete and other places throughout the Mediterranean, disrupting the Bronze Age Mycenaean civilization. Peloponnesian cities that the Dorians invaded include Corinth, Olympia, Sparta and Mycenae. Many archaeologists attribute the destruction of Mycenae, a pivotal Mycenaean city, to these invading Dorians.

Though most of the Doric invaders settled in the Peloponesse, they also settled on Rhodes and in Asia Minor, where in later times the Dorian Hexapolis (the six Dorian cities) would arise: Halicarnassus, Cos, Cnidos (Asia Minor); Lindos, Kameiros (Camiros), and Ialyssos (in Rhodes). These six cities would later become rivals with the Ionian cities of Asia Minor. The Dorians also invaded Crete. These origin traditions remained strong into classical times: Thucydides saw the Peloponnesian War in part as "Ionians fighting against Dorians" and reported the tradition that the Syracusans in Sicily were of Dorian descent (Thucydides, 7.57). Other such "Dorian" colonies, originally from Corinth, Megara, and the Dorian islands, dotted the southern coasts of Sicily from Syracuse to Selinus. Culturally, in addition to their Doric dialect of Greek, these colonies retained their characteristic Doric calendar revolving round a cycle of festivals of which the Hyacinthia and the Carneia were especially important (EB 1911).

The Dorian invasion was partly responsible for the subsequent Greek Dark Ages. The written record is nonexistent; the Dorian migration is documented in the mute archaeological record: widespread burning and destruction of Bronze Age sites both in Crete and the mainland of Greece, many of which were reduced to villages or abandoned, and the introduction of iron-working ended the Bronze Age in the Aegean.

The Dorian invasion

The Dorian invasion, more often called the Dorian migration in modern texts, is co-related with ash layers at Mycenaean sites and changes in burial practices, from Mycenaean group burials in tholos tombs to individual burials and the burning of the corpse, previously unknown. Considered as an invasion, the advent of the Dorians is generally advanced to explain the swift collapse of Mycenaean civilization in ancient mainland Greece. Concurrent effects are the disruption of long-distance trade and possibilities of civil war and natural disaster, as well as the colonisation of islands in the Aegean sea and the west coast of Asia Minor.

Mythic origins

According to a myth based on an etymological fantasy, the Dorians were named for the minor district of Doris in northern Greece. Their leaders were mythologized as the Heracleidae, the sons of the legendary hero Heracles, and the Dorian incursion into Greece in the distant past was justified in the mythic theme of the "Return of the Heracleidae". The most famous of Dorian groups were the Spartans, whose austere and martial lifestyle was much admired and feared.

Upon the death of Eurystheus an oracle tells the Mycenaeans to choose a Pelopid king and Atreus and Thyestes — already installed in nearby Midea by Sthenelus — contend for the prize. Atreus eventually wins out and his son, Orestes, returns to Mycenae and seizes the throne from Aletes, son of Aegisthus.

Orestes expanded his kingdom to include all of Argos, and he became king of Sparta by marrying Hermione, his cousin and the daughter of Menelaus and Helen. Finally, Tisamenus, Orestes' son by Hermione, the daughter of Helen, inherits the throne.

The Heracleidae ("children of Heracles") return to the Peloponnese, led by Hyllus, the son of Heracles, and Iolaus, Heracles' nephew, and contend with the Pelopidae ("children of Pelops") for possession of the Peloponnese.

The Heracleidae base their claim to power on their descent, through Heracles, from Perseus, the founder of Mycenae, whereas Tisamenus was a Pelopid whom the Heracleidae regard as a usurper.

After a year, the Heracleidae are driven out by plague and famine. Upon consulting the Delphic oracle, they were told that they had returned before their proper time: the god said they should await "the third crop."

Accordingly, after three years, the Heracleidae invade the Peloponnese again, and Hyllus challenges the Peloponnesians to single-armed combat. In the ensuing duel with Echemus, king of Arcadia, Hyllus is killed and the Heracleidae undertake to withdraw for fifty years.

The Heracleidae invade again, under the leadership of Aristomachus, the son of Hyllus and Heracles' grandson. But Aristomachus is slain in combat with Tisamenus and his army, and the Heracleidae withdraw once again.

Upon consulting the oracle again, the Heracleidae are told that "the third crop" referred to the third generation of Heracles' descendants.

The Return of the Heracleidae under Heracles' great-grandsons is finally successful — although Aristodemus is slain by a thunderbolt, and his sons Procles and Eurysthenes assume leadership of his forces.

Temenus, Procles and Eurysthenes (the sons of Aristodemus), and Cresphontes cast lots for the kingdoms. Temenus becomes master of Argos, Procles and Eurysthenes of Sparta, and Cresphontes of Messenia.

Cresphontes secured the rule of Messenia for himself by the following stratagem: it was agreed that the first drawing of lots was for Argos, the second for Lacedaemon, and the third for Messenia. Both Temenus and the sons of Aristodemus throw stones into a pitcher of water, but Cresphontes cast in a clod of earth; since it was dissolved in the water, the other two lots turned up first.

Traditionally, this "Return of the Heracleidae" takes place eighty years after the Trojan war — between 1100 and 950 bce — and is represented as the recovery by the descendants of Heracles of the rightful inheritance of their hero ancestor and his sons.

For ancient historians, the Return of the Heracleidae explained the spread of Doric language and culture throughout areas regarded as Achaean during the Minoan and Mycenean eras: in the historical period the whole of the Peloponnese with the exception of Arcadia, Elis, and Achaea is Doric, along with Doris in northern Greece and the islands of Crete and Rhodes.

The traditional date of the "Dorian Invasion" correlates with archaeological evidence of widespread burning, destruction, or abandoning of Bronze Age sites on both Crete and the mainland in Late Helladic IIIC (1200-1050 bce), and the beginning of the Dark Ages in Greece.

The destructions are clear, but their causes are much disputed — theories run the gamut from economic factors, to social upheaval, climatic change, or external invasion.

And it is generally agreed that Doric speakers did enter Greece around this time, but most likely as a migration after the Mycenaean centers were destroyed. (The late Bronze Age was a period of migration throughout the Mediterranean basin.)

Dorians Tribes through the Ages

(from 1600 & 1100 BC to Today)

Pontians

Macedonians

Cretans

Spartans

Epirotes

Rhodians

Cypriots

Troyans*

* New evidences (2008) in south Italy reports: "part of people of Troy should be primal Dorian race" source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/169476/Dorian-invasion

Sources:

Foundation of Hellenic World

Britannica

Helios

Eleftheroudakis

Foundation for Hellenic Studies

Hellenic Foundation for Culture

Nikos Deja Vu

n1999k.blogspot.com

youtube.com/nikosdejavu

0 notes

Text

Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse occurred between 1206 and 1150 BCE and was marked by a sharp decline in trade, a widespread loss of written language, and the destruction of the overwhelming majority of cities in the region, from Phylos to Gaza, some of which were never resettled.

I believe the key to understanding this collapse is recognizing that all of these civilizations formed a shared world-system. Linguistics, as well as the Western inclination to break up reality into subjects (and corresponding objects or inert material) rather than understanding it as a question of fields and relationships, can prejudice us to view the region as being populated by “separate” cultures and polities: the Egyptians; the Assyrians; the Israelites; the Mycenaeans; and so forth. It is more accurate to understand these peoples and polities as different strands woven together in a complex fabric.

The Bronze Age collapse has been widely studied, and numerous causes have been proposed, from an increase in warfare and barbarian invasion, to climatic changes and volcanic eruptions, to economic collapse stemming from the exhaustion of the bronze supply (bronze-based industry, unlike the iron-based industry that followed it, required intense trade networks spanning a large geographic region). None of these explanations seems satisfying in its own right, and none enjoy a scientific consensus. Before suggesting another cause, I would like to problematize the concept of causation itself, at least in how it has traditionally been approached in scientific research.

Can we imagine that the periodic outbursts of insurrection, collapse, civil war, and revolution that at the present are occurring with an increasing frequency (Albania, Bolivia, Greece, Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Brazil, etc.) eventually intensify to the point where they cause the collapse of the current world system? And what if ten thousand years went by, all electronic records were lost, and the only thing future researchers could uncover were climate data, some of the most basic chronologies of the major states, and some cursory information about economic practices?

Surely some would hypothesize that climate change were the cause of the collapse, others—unearthing cryptic references to the appearance of a bellicose class known as “terrorists” and discovering archaeological evidence of civil war in Ukraine, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, Libya, and Colombia—would suggest invasion and warfare. Others might posit peak oil or currency inflation. From the current standpoint, all of these explanations should strike us as unsatisfactory, precisely because they are all interrelated and none of them, precisely, is the cause of the increasing systemic insecurity we can feel. At least not in the way a chemical reaction can be identified as having a clean, simple, concrete cause. On the contrary, all of these factors contribute to the insecurity of the world system, that great fabric we are all wrapped up in. Each of these factors shakes and pulls at the fabric, causing growing instability, until any structures built atop the fabric collapse (or until the fabric itself is torn). In complex systems, it is instability and turmoil that cause systemic collapse and the spontaneous emergence of new systems. But instability is not just the sum of discrete forces acting on a static equilibrium. On the contrary, the instability comes to constitute a force in itself that triggers more destabilizing events. It unifies the total array of forces that cause individuals and communities to reproduce the dynamic equilibrium of the system or to rebel against it. These forces are economic, ecological, technological, political (in terms of administrative structures, discourses of legitimacy, and also relations of war/peace between polities), spiritual, and also psychosocial. This last, often ignored, and approaching what George Katsiaficas terms the “eros effect,” is undeniable on the ground: a society is most likely to rebel when the power structures that dominate it appear unstable, or when neighboring societies also rebel, no matter what their reasons. This explains why, starting at the end of 2008, social rebellions occurred with greater frequency, even in many countries where the economic crisis had only appeared in the news but not yet manifested in higher unemployment, or why there was a direct interplay and transference between insurrections and uprisings in Greece and Turkey—one country in economic recession and the other experiencing economic growth—or Greece and Bulgaria—one uprising inspired by anarchist values and the other by fascist values.

Assuming that we can understand systemic collapse in this light, I would like to suggest another factor (potentially the most important factor, although the data do not exist to prove this claim) for the Bronze Age collapse: internal rebellion and struggles for freedom.

I propose that we would attain a far more accurate view of history if, every time a state collapsed, we assumed rebellion was a principal cause, unless evidence existed for another cause. We know that states provoke resistance from their own subjects, and that struggles for freedom are universal (although visions of freedom and methods for attaining it are beyond any doubt historically and culturally specific). Too often, historians and archaeologists fabricate cheap mysteries, “Why did this great civilization suddenly collapse?,” because they refuse to accept the obvious: that states are odious structures that their populations destroy whenever they get the opportunity, and sometimes even when they face impossible odds.

- Peter Gelderloos “Worshiping Power: An Anarchist View of Early State Formation” chapter VII

144 notes

·

View notes