#vera figner

Text

Termékeny munka és harc helyett, amely egy tökéletesebb életformát hivatott megteremteni, ezek az emberek leülnek a pamlagra, és így szólnak: "Beszéljünk arról, mi lesz kétszáz év múlva." Csak álmodoznak a jövőről, s ez a passzív álmodozás az emberiség ragyogó, derűs, boldog jövőjéről az egyetlen fénysugár létük félhomályában.

Valóban ilyen volna a mai nemzedék? Valóban ilyen fénytelen, ilyen reménytelen, ilyen holt a mai élet? Minek akkor egyáltalában kiszabadulni a börtönből? Nem mindegy: itt tengetetem-e életemet, vagy odakünn? Ha kilépek a fegyház kapuján, egy kis börtönből egy nagy börtönbe jutok. Miért lépjek akkor ki ezen a kapun? Mi célja annak, hogy a szürke bizonyosságot a szürke bizonytalanságra cseréljem fel?

Vera Figner gondolatai a börtönből történő szabadulása előtt

#vera figner#napló#gondolatnapló#gondolat#szorongás#nagyoncringe#magyar#depresszió#öngyilkosság#szeretet#saját#vera#figner#idézet#fájdalom#szerelem#gondolatok#kapcsolat#forradalom#generáció#mentális egészség#börtön#magyarország#magyar tumblisok#hianyzol#magyar tumblr#magyarul#magyar vers#magyar zene#saját sztori

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

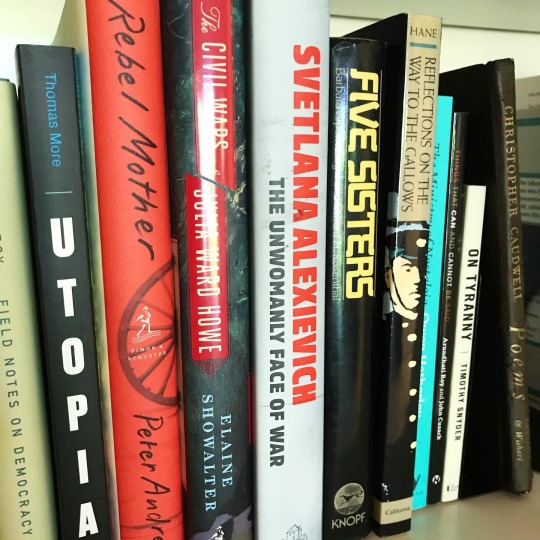

International Worker’s Day

#a little belated#booklr#international workers day#may day#arundhati roy#china mieville#verso books#history#reflections on the way to the gallows#vera figner

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Vera Figner

The life of Vera Figner is perhaps one of the most remarkable in Russian history. Born to noble parents in the Russian backwoods, Vera spent her childhood under the auspices of a governess who taught Vera and her sister music theory, French diction and dance concepts...http://www.findingvera.net/early-years

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Here is a list of books you might want to read if you are interested in the Romanov dynasty and the country and society they goverened. I have read some, I own most and some may be of warying quality and reliability. Some include periods before and after the Russian Empire. Some could be fitted into more than one cathegory. A few are not available in English.I will try to update this list from time to time as I find new books or new books become published. Enjoy!

Diaries and correspondence of the Romanovs

The Memoirs of Catherine the Great

Love and Conquest: Personal Correspondence of Catherine the Great and Prince Grigory Potemkin

Chere Annette: Letters from St. Petersburg, 1820-1828: The Correspondence of the Empress Maria Feodorovna to Her Daughter the Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna

A Lifelong Passion: Nicholas and Alexandra: Their Own Story

Romanov Family Yearbook: On This Date in Their Own Words

The Letters of Tsar Nicholas and Empress Marie

The Correspondence Of The Empress Alexandra Of Russia With Ernst Ludwig And Eleonore, Grand Duke And Duchess Of Hesse

The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra: April 1914-March 1917

In the Steps of the Romanovs: Final Two Years of the Last Russian Imperial Family (1916-1918)

The Last Diary of Tsaritsa Alexandra

The Diary of Olga Romanov: Royal Witness to the Russian Revolution

Journal of a Russian Grand Duchess: Complete Annotated 1913 Diary of Olga Romanov, Eldest Daughter of the Last Tsar

Tatiana Romanov, Daughter of the Last Tsar: Diaries and Letters, 1913–1918

Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918

1913 Diary of Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna: Complete Tercentennial Journal of the Third Daughter of the Last Tsar

Maria and Anastasia: The Youngest Romanov Grand Duchesses In Their Own Words

Correspondence of the Russian Grand Duchesses: Letters of the Daughters of the Last Tsar

Michael Romanov: Brother of the Last Tsar Diaries and Letters, 1916-1918

Diaries and correspondence of other people

Russian journal of Lady Londonderry, 1836-37

Letters from Russia

The Diaries of Sofia Tolstoy

Letters from St Petersburg: A Siamese Prince at the Court of the Last Tsar

The Romanovs Under House Arrest: From the 1917 Diary of a Palace Priest

Private Diary of Mathilde Kschessinska

A Countess in Limbo: Diaries in War & Revolution; Russia 1914-1920, France 1939-1947

Memoirs by the Romanovs

Once a Grand Duke

Always a Grand Duke

25 Chapters of My Life

Education of a Princess

A Princess in Exile

A Romanov Diary: The Autobiography of H.I.& R.H. Grand Duchess George

My life in Russia's service--then and now

Memories In The Marble Palace

Memoirs by other people

The Memoirs of Princess Dashkova

Lost Splendor

Memories of the Russian Court

My Mission to Russia and Other Diplomatic Memories

An Ambassador's Memoirs

The Real Tsaritsa

Thirteen Years at the Russian Court

The False Anastasia

Six Years at the Russian Court

Before the Storm

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna Empress of Russia

Left Behind

At the Court of the Last Tsar

Memories of Russia 1916-1919

The Emperor Nicholas II: As I Knew Him

The Sokolov Investigation of the Alleged Murder of the Russian Imperial Family

The Russia That I Loved

Dancing in Petersburg: The Memoirs of Kschessinska

On the Estate: Memoirs of a Russian Lady before the Revolution

Theater Street

The Other Russia: The Experience of Exile

Russia Through Women's Eyes: Autobiographies from Tsarist Russia

The Fall of the Romanovs: Political Dreams and Personal Struggles in a Time of Revolution

Tommorow Will Come

Fanny Lear: Love and Scandal in Tsarist Russia

The Coronation of Tsar Nicholas II

Days of the Russian Revolution: Memoirs from the right, 1905-1917

The House by the Dvina: A Russian Childhood

Under Three Tsars

Last days at Tsarskoe Selo

Last Years of the Court at Tsarskoe Selo

The Real Romanovs

Biographies of the Romanovs and general topics concerning them

The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias

The Romanovs: 1613-1918

The Romanovs

The Romanovs: Ruling Russia 1613-1917

Secret Lives of the Tsars: Three Centuries of Autocracy, Debauchery, Betrayal, Murder, and Madness from Romanov Russia

The Tragic Dynasty: A History of the Romanovs

The Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion, and the Fall of Imperial Russia

Romanov Autumn: Stories from the Last Century of Imperial Russia

The Romanovs, 1818–1959: Alexander II of Russia and His Family

Alexis, Tsar of all the Russias

Sophia: Regent of Russia, 1657-1704

Peter the Great: His Life and World

Peter the Great

Terrible Tsarinas: Five Russian Women in Power

Elizabeth and Catherine: Empresses of All the Russias

Catherine the Great

Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman

Catherine the Great & Potemkin: the imperial love affair

Catherine the Great: Love, Sex, and Power

Great Catherine: The Life of Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia

The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia

Alexander I: The Tsar Who Defeated Napoleon

Alexander I: Tsar of War and Peace

Alexander of Russia: Napoleon's Conqueror

Nicholas I and Official Nationality in Russia 1825 - 1855

Nicholas I: Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias

Becoming a Romanov. Grand Duchess Elena of Russia and her World

Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar

Katia: Wife Before God

Alexander III: His Life and Reign

Little Mother of Russia: A Biography of the Empress Marie Feodorovna

Nicholas II: Emperor of All the Russias

Nicholas II: Last of the Tsars

The Last of the Tsars : Nicholas II and the Russian Revolution

The Last Tsar: The Life and Death of Nicholas II

King, Kaiser, Tsar: Three Royal Cousins Who Led The World To War

A Gathered Radiance: The Life of Alexandra Romanov, Russia's Last Empress

The Last Empress: The Life and Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, Tsarina of Russia

Alexandra

Alexandra: The Last Tsarina

Nicholas and Alexandra

Alix and Nicky: The Passion of the Last Tsar and Tsarina

The Last Tsar & Tsarina

The Four Graces: Queen Victoria's Hessian Granddaughters

The Imperial Tea Party: Family, Politics and Betrayal: the Ill-Fated British and Russian Royal Alliance

From Splendor to Revolution: The Romanov Women, 1847-1928

Born to Rule: Five Reigning Consorts, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria and The Romanovs: Sixty Years of Mutual Distrust

Queen Victoria's Matchmaking: The Royal Marriages that Shaped Europe

Imperial Requiem: Four Royal Women and the Fall of the Age of Empires

The Romanov Royal Martyrs: What Silence Could Not Conceal

The Romanovs: Family of Faith and Charity

The Romanovs: The Final Chapter

The Last Days of the Romanovs: Tragedy at Ekaterinburg

The Fate of the Romanovs

The Murder of the Romanovs

The House of Special Purpose

The Murder of the Tsar

Alexei: Russia's Last Imperial Heir: A Chronicle of Tragedy

A Guarded Secret : Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra and Tsarevich Alexei's Hemophilia

The Romanov Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra

The Grand Dukes

The Grand Dukes - Sons And Grandsons Of Russia's Tsars

The Other Grand Dukes: Sons and Grandsons of Russia's Grand Dukes

White Crow: The Life and Times of the Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich Romanov, 1859-1919

The Grand Duchesses: Daughters & Granddaughters of Russia's Tsars

Once a Grand Duchess: Xenia, Sister of Nicholas II

Michael and Natasha: The Life and Love of Michael II, the Last of the Romanov Tsars

The Last Grand Duchess: Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna

Olga Romanov: Russia's Last Grand Duchess

Ella: Princess, Saint and Martyr

Elizabeth, Grand Duchess of Russia

Grand Duchess Elizabeth of Russia: New Martyr of the Communist Yoke

Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna

Princess Victoria Melita

A Fatal Passion: The Story of the Uncrowned Last Empress of Russia

Gilded Prism: The Konstantinovichi Grand Dukes & The Last Years Of The Romanov Dynasty

Death of a Romanov Prince

A Poet Among the Romanovs: Prince Vladimir Paley

Princesses on the Wards: Royal Women in Nursing through Wars and Revolutions

The Romanovs: The Way It Was

Behind the Veil at the Russian Court

The Flight of the Romanovs: A Family Saga

Russia and Europe: Dynastic Ties

Biographies of other people

The Tsar's Doctor: The Life and Times of Sir James Wylie

The Romanovs & Mr Gibbes: The Story of the Englishman Who Taught the Children of the Last Tsar

An Englishman in the Court of the Tsar: The Spiritual Journey of Charles Syndney Gibbes

The Forgotten Tutor: John Epps and the Romanovs

The Rasputin File

Rasputin: The Untold Story

Rasputin: Rascal Master

Rasputin: The Biography

Rasputin: a Short Life

The Murder of Grigorii Rasputin: A Conspiracy That Brought Down the Russian Empire

The Man Who Killed Rasputin: Prince Felix Youssoupov and the Murder That Helped Bring Down the Russian Empire

The Princess of Siberia

Angel of Vengeance: The Girl Who Shot the Governor of St. Petersburg and Sparked the Age of Assassination

Imperial Dancer: Mathilde Kschessinska and the Romanovs

Diaghilev: A Life

Nijinsky: A Life of Genius and Madness

The Russian Album

Russian Blood

Tolstoy: A Russian Life

The Pearl: A True Tale of Forbidden Love in Catherine the Great's Russia

Katya and the Prince of Siam

The Defiant Life of Vera Figner: Surviving the Russian Revolution

Pushkin: A Biography

Photoalbums, cofee-table books

The Camera and the Tsars: The Romanov Family in Photographs

The Romanov Family Album

Tsar: The Lost World of Nicholas and Alexandra

The Romanovs: Love, Power and Tragedy

The Regalia of the Russian Empire

The Sunset of the Romanov Dynasty

The Summer Palaces of the Romanovs: Treasures from Tsarskoye Selo

Royal Russia: The Private Albums of the Russian Imperial Family

Russia: Art, Royalty and the Romanovs

Nicholas II: The Last Tsar

Nicholas and Alexandra: The Family Albums

The Last Tsar

Romanovs Revisited

The Private World of the Last Tsar: In the Photographs and Notes of General Count Alexander Grabbe

The Jewel Album of Tsar Nicholas II: A Collection of Private Photographs of the Russian Imperial Family

Anastasia's Album

Lost Tales: Stories for the Tsar's Children

The Last Courts of Europe: Royal Family Album 1860-1914

Dear Ellen (Royal Europe Through the Photo Albums of Grand Duchess Helen Vladimirovna of Russia)

Royal Gatherings (Who is in the Picture? Volume 1: 1859-1914)

Jewels of the Tsars: The Romanovs and Imperial Russia

Jewels from Imperial St. Petersburg

Postcards from the Russian Revolution

Before the Revolution: A View of Russia Under the Last Czar

Twilight of the Romanovs: A Photographic Odyssey Across Imperial Russia

The Romanov Legacy: The Palaces of St. Petersburg

Moscow: Splendours of the Romanovs

Fabergé, Lost and Found: The Recently Discovered Jewelry Designs from the St. Petersburg Archives

Art of Fabergé

Faberge: Treasures of Imperial Russia

Artistic Luxury: Fabergé, Tiffany, Lalique

Russian Imperial Style

A Smolny Album: Glimpses into Life at the Imperial Educational Society of Noble Maidens

Konstantin Makovsky: The Tsar’s Painter in America and Paris

Anna Pavlova: Twentieth Century Ballerina

Tamara Karsavina: Diaghilev's Ballerina

General history and specific events

Russian Chronicles

Russia's First Civil War: The Time of Troubles and the Founding of the Romanov Dynasty

The Court of Russia in the Nineteenth Century; Volume 1

The Court of Russia in the Nineteenth Century; Volume 2

The Crimean War: A History

Internal Colonization: Russia's Imperial Experience

The Conquest of a Continent: Siberia and the Russians

Red Fortress: History and Illusion in the Kremlin

Sunlight at Midnight: St. Petersburg and the Rise of Modern Russia

St Petersburg: Three Centuries of Murderous Desire

The Shadow of the Winter Palace: Russia's Drift to Revolution 1825-1917

Society and lifestyle

Land of the Firebird: The Beauty of Old Russia

Serfdom, Society, and the Arts in Imperial Russia: The Pleasure and the Power

Lord and Peasant in Russia from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century

A Bride for the Tsar: Bride-Shows and Marriage Politics in Early Modern Russia

Origins of the Russian Intelligentsia: The Eighteenth-Century Nobility

The Icon and the Axe: An Interpretive History of Russian Culture

The Court of the Last Tsar: Pomp, Power and Pageantry in the Reign of Nicholas II

Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy, Vol. 1

Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy, Vol. 2

Pavlovsk : The Life of a Russian Palace

Entertaining Tsarist Russia: Tales, Songs, Plays, Movies, Jokes, Ads, and Images from Russian Urban Life, 1779-1917

A Social History of the Russian Empire, 1650-1825

Slavophile Empire: Imperial Russia's Illiberal Path

Russia at Play

Women In Russian History: From The Tenth To The Twentieth Century

St. Petersburg: A Cultural History

Russian Peasant Women

Romanov Riches: Russian Writers and Artists Under the Tsars

The Magical Chorus: A History of Russian Culture from Tolstoy to Solzhenitsyn

Family in Imperial Russia

Village Life in Late Tsarist Russia

Imperial Crimea: Estates, Enchantments and the Last of the Romanovs

Russia on the Eve of Modernity: Popular Religion and Traditional Culture Under the Last Tsars

The Martha-Mary Convent: and Rule of St. Elizabeth the New Martyr

The Way of a Pilgrim

Icon and Devotion: Sacred Spaces in Imperial Russia

Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia

Valse Des Fleurs: A Day in St. Petersburg in 1868

Murder Most Russian: True Crime and Punishment in Late Imperial Russia

What Life Was Like in the Time of War and Peace: Imperial Russia, AD 1696-1917

When Miss Emmie Was in Russia: English Governesses Before, During and After the October Revolution

From Cradle to Crown: British Nannies and Governesses at the World's Royal Courts

What Became Peters Dream: Court Culture in the Reign of Nicholas II

Faberge's Eggs: The Extraordinary Story of the Masterpieces That Outlived an Empire

Beauty in Exile: The Artists, Models, and Nobility who Fled the Russian Revolution and Influenced the World of Fashion

Revolution and its general aftermath

Spies and Commissars: The Early Years of the Russian Revolution

A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891-1924

Interpreting the Russian Revolution: The Language and Symbols of 1917

The Russian Court at Sea: The Voyage of HMS Marlborough

Former People: The Final Days of the Russian Aristocracy

The Downfall of Russia

Doomsday 1917: The Destruction of Russia's Ruling Class

Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd, Russia, 1917

To Free the Romanovs: Royal Kinship and Betrayal in Europe 1917-1919

The Race to Save the Romanovs: The Truth Behind the Secret Plans to Rescue Russia's Imperial Family

Students, Love, Cheka and Death

Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War, 1918-1921

Conspirator: Lenin in Exile

Hidden Treasures of the Romanovs

Romanoff Gold: The Lost Fortunes of the Tsars

Russia Abroad: Prague and the Russian Diaspora, 1918–1938

Bread of Exile

The Many Deaths of Tsar Nicholas II: Relics, Remains and the Romanovs

Saving The Tsars' Palaces

Catalogues

Kejserinde Dagmar

Nicholas And Alexandra: The Last Tsar And Tsarina

Russian Splendor: Sumptuous Fashions of the Russian Court

At The Russian Court: Palace And Protocol In The 19th Century

History of Russian Costume from the Eleventh to the Twentieth Century

Collections of the Romanovs: European Arts from the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Magnificence of the Tsars: Ceremonial Men's Dress of the Russian Imperial Court, 1721-1917

Conspiracy and pretenders

Imperial Legend: The Mysterious Disappearance of Tsar Alexander I

The File on the Tsar

The Escape of Alexei, Son of Tsar Nicholas II: What Happened the Night the Romanov Family Was Executed

The Romanov Conspiracies

I am Anastasia; The Autobiography of the Grand Duchess of Russia.

The Resurrection of the Romanovs: Anastasia, Anna Anderson, and the World's Greatest Royal Mystery

A Romanov Fantasy: Life at the Court of Anna Anderson

The Secret Plot to Save the Tsar: The Truth Behind the Romanov Mystery

The Quest for Anastasia: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Romanovs

695 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Praskov’ia Naumovna Belenkaia was born on 12 April 1864 or 1865 (her Moscow archive lists her date of birth as 1865 but the autobiographical statement in her St Petersburg archive lists it as 1864), to a Jewish family in St Petersburg, probably of the merchant class since Jewish residence in the Imperial capital was strictly limited. Admitted to the physics and mathematics section of the St Petersburg Vysshie Zhenskie (Bestuzhevskie) Kursy (Bestuzhev Higher Women’s Courses), Belenkaia completed the third graduating class of the Courses in 1884. She never took her final exam—perhaps due to her political activities; the Courses were a hotbed of radicalism and, like a number of other feminist activists, Belenkaia was a student radical.

The date of Belenkaia’s marriage is not known, but upon marriage she adopted the family name of her husband, Miron Isaevich Arian. Praskov’ia Arian supported herself as a translator and journalist—forms of employment available to educated Russian women—while seeking to combine her work with her ideals. She wrote for a range of publications, including the Birzhevye Vedomosti (Stock market gazette), the Sputnik Zdorov’ia (Health guide), the Vestnik Blagotvoritel’nosti (Philanthropy bulletin) and Iskusstvo i Zhizn’ (Art and life). In 1884, she founded a daycare center, Detskaia Pomoshch’ (Children’s Aid), for children of workers in St Petersburg, where she worked for ten years alongside the center’s first President (and feminist pioneer), Nadezhda Vasil’evna Stasova.

In 1899, Arian founded the Pervyi Zhenskii Kalendar’ (First Women’s Calendar), single-handedly compiling, editing and publishing this compendium of information for women (each year from 1899 to 1915). The Kalendar’ contained articles on religion, health, employment and education, as well as biographical sketches of Russian feminists, radical activists and literary figures, with accompanying photos. It chronicled the activities of the major feminist organizations, such as the Russkoe Zhenskoe Vzaimno-Blagotvoritel’noe Obshchestvo (Russian Women’s Mutual Philanthropic Society)—including photos of the society’s facilities—and the Liga Ravnopraviia Zhenshchin (League for Women’s Equal Rights).

Feminist congresses also received detailed coverage: in particular the 1908 Pervyi Vserossiiskii Zhenskii S’ezd (First All-Russian Congress of Women) and the Pervyi Vserossiiskii S’ezd po Obrazovaniiu Zhenshchin (First All-Russian Congress on Women’s Education; held from 26 December 1912 to 4 January 1913). Arian recruited a wide range of contributors to the Kalendar’, including the writer Maxim Gorky, the radical activist Vera Figner, the artist Il’ia Repin and the psychologist Vladimir Bekhterev. Arian traveled widely. Working in the archives of Swiss universities, she gathered data on Russian women studying abroad for the Kalendar’ issues of 1899 and 1912 and, after a trip to Japan, published articles on the Women’s University in Tokyo and the status of Japanese women (see the Kalendar’ issues of 1904 and 1905).

News about the international women’s movement was a regular feature of the Kalendar’. The Kalendar’ dwelled on a range of issues affecting women. Prominent among them was health, both physical and mental. Each issue contained nutritional advice and pointers on personal hygiene and behavior. The 1912 Kalendar’, for example, included the article “Nervnost’ i mery dlia bor’by s nei” (Anxiety and ways to fight it). Arian is perhaps best known as the driving force behind the establishment of the First Women’s Technical Institute. It was Arian who lobbied the government tirelessly for permission to open what were originally called the Vysshie Zhenskie Politekhnicheskie Kursy (Women’s Higher Polytechnical Courses); she also carried out the fundraising necessary to sustain the new venture, hired the staff and rented the initial space (an apartment) in her own name.

When the Courses opened on 15 January 1906, they were the first in the world to train women engineers. Arian remained committed to providing educational opportunities for workers of both sexes. In the year that the Vysshie Zhenskie Politekhnicheskie kursy opened (1906), she was granted permission to open an evening school for workers in the Narva Gate section of St Petersburg. Despite government harassment, closings and arrests of students, the school survived for ten years. Never once imprisoned for her activities, Arian maintained ties with those who had been incarcerated for their opposition to the tsarist regime. From 1907–1917, she was an active member of the support group for prisoners in the notorious Schlusselburg Fortress.

Arian was among a number of women activists in this period to maintain ties with political radicals and with legal feminist groups. The pattern of her activism challenges the notion that women of her generation went ‘from feminism to radicalism’ and that feminism and radicalism were separate, mutually exclusive spheres. Arian was active in the Russkoe Zhenskoe Vzaimno-Blagotvoritel’noe Obshchestvo (Russian Women’s Mutual Philanthropic Society), speaking and writing for the society, working in its library and chairing the committee researching conditions of women’s work in Russia.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Arian complained privately to friends about the mere lip service paid by the Bolsheviks to women’s rights. In the 1930s, she conducted courses for workers at the Kirov factory in Leningrad (today St Petersburg), lecturing on Pushkin. In 1942, during the siege of Leningrad, she was evacuated to Piatigorsk and then to Tashkent. She died in Moscow (?) on 28 March 1949.”

- Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild, “ARIAN, Praskov’ia Naumovna Belenkaia (1864/5–1949) in Biographical Dictionary of Women’s Movements and Feminisms

14 notes

·

View notes

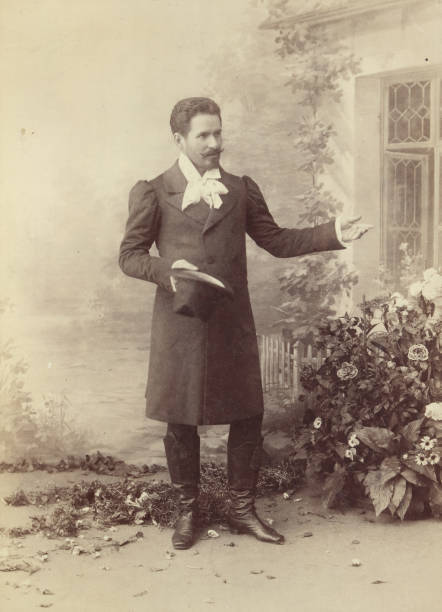

Photo

Nikolay Nikolayevich Figner (1857–1918), lyric tenor, was born in Nikiforovka, near Kazan, on 9/21 February 1857. He was a brother of the famous "People's Will" revolutionary, Vera Figner (1852–1942). He joined the Russian Navy as a midshipman, and rose to the rank of lieutenant, retiring in 1881 to study voice with Vassily Samus, I. P. Pryanishnikova and Camille Everardi at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Figner then travelled to Italy, where he made his debut at Naples in Gounod's Philémon et Baucis in 1882.[3] He sang at the San Carlo Theatre and appeared at other Italian venues for a number of years. While in Italy, Figner took the opportunity to study with the prominent singing teacher Francesco Lamperti and also received instruction from E. de Roxas. Figner performed, too, in Madrid, Bucharest and London (at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden) He travelled to South America as well during this period. On 4 November 1886, in Turin, he sang the principal tenor role in the world premiere of the revised version of Alfredo Catalani's Edmea;[4] this was also the occasion of Arturo Toscanini's first appearance as a conductor in Italy after his initial triumph in South America.[3][5][6] During his travels, he sang roles such as Arnold in Rossini's William Tell, the Duke in Verdi's Rigoletto, and Carlo in Donizetti's Linda di Chamounix. He also happened to appear on stage with Medea Mei in a production of Donizetti's La favorite; they formed a liaison, and he brought her back to Russia in 1887. Two years later, they wed. Figner soon established himself as the leading tenor at the Mariinsky Theatre, retaining this status until 1903. Other Russian composers whose operas he sang were Alexander Borodin (Vladimir in Prince Igor), Alexander Dargomyzhsky (the Prince in Rusalka), and Anton Rubinstein (Sinodal in The Demon). A good-looking man, he projected a memorable stage presence and sang with sensitivity and style.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

do i have a crush on vera figner? perhaps

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vera Figner, Russian Bolshevik on seperation between activist front and military front

0 notes

Text

Some interesting facts on the development of War and Peace from my reading of R.F. Christian’s Tolstoy’s War and Peace: A Study

#2: Prototypes

Natasha is actually based off of Tolstoy’s sister-in-law, Tatyana “Tanya” Behrs Kuzminskaya

Interesting (but not from this book): Tanya was actually known for her beautiful, deep contralto singing voice. It’s possible Tolstoy envisioned Natasha’s voice the same

The incident with Anatole is based off of Tanya’s real experience with Anatoly Shostak, who served as a prototype for Anatole Kuragin

The male Rostovs are based off his family, Nikolai being his father, Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy, and Ilya being his grandfather Ilya Andreevich.

They were once going to be called the “Prostoys.” Prostoy means “simple,” making Ilya “Count Simple.” Tolstoy considered the real Ilya a man of limited intelligence.

Sonya is likely based on his wife Sofya, and Vera on his other sister-in-law, Elizaveta Behrs. Vera was originally called “Lise.”

Marya Dmitrievna Akhrosimova was based on a real woman named Nastasya Dmitrievna Ofrosimova. She was a proud, old fashioned Russian well known for not mincing words and appeared as an inspiration in other works by Tolstoy’s contemporaries.

Dolokhov was a combination of A.S. Figner and Tolstoy’s relative, Fyodor Ivanovich Tolstoy.

Tolstoy stated that unlike other characters, Prince Andrei was not based on anyone, but rather invented to fill a position in the story.

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ám ha az önkényuralom nem törődik sem a nép szükségleteivel, sem a társadalom törekvéseivel, s vakon halad a maga útján; ha a nép jajszava, (...) minden követelése és a publicisták hangja egyaránt süket fülekre talál; ha a hatalmat nem érdeklik sem a tudósok komoly kutatásainak eredményei, sem a statisztika számadatai; ha az alattvalók egyetlen csoportjának sem áll módjában bármiképpen is befolyásolni a közéletet; ha minden eszköz meddő, s minden út el van zárva; ha a társadalom fiatal, hevülékenyebb rétege számára nem nyílik működési tér, s hiába akarja a nép javát szolgálni, nem talál semmit, amit lelkesedésének tüzével táplálhatna - akkor elviselhetetlenné válik a helyzet. Akkor a felháborodás minden ereje a társadalomtól elszakadt államhatalom megszemélyesítőjére és képviselőjére, az uralkodóra zúdúl, aki maga nyilvánítja ki, hogy ő felelős a nemzet életéért, jólétéért és boldogságáért, s aki maga eszét és erejét az emberek millióinak esze és ereje fölé helyezi; s ha a meggyőzés minden eszközét latba vetettük, és minden meggyőző kísérlet egyformán meddőnek bizonyult, nem marad más hátra, mint a fizikai erőszak: a tőr, a revolver, a dinamit.

Vera Figner

#vera figner#napló#gondolatnapló#gondolat#nagyoncringe#magyar#depresszió#szorongás#öngyilkosság#saját#szeretet#idézés#magyar idézetek#fidesz#orbán kormány#orbán viktor#orbán egy geci#saját idézet#idézetek#idézet#idéz#saját fotó#saját sztori#saját szöveg#sajat erzes#saját gondolat#sajnálom

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

“ I. A special kind of policeman

The Okhrana took over in 1881 from the notorious Third Section of the Ministry of the Interior. But it only really developed after 1900, when a new generation of police was put in charge. The old officers of the constabulary, in particular the higher ranks, had considered it contrary to military honour to occupy themselves with certain aspects of police business. The new school overrode such scruples, and undertook to organise the secret police on a scientific basis, to carry out provocation, informing and betrayal inside the revolutionary parties. It was to produce talented, erudite men like the Colonel Spiridovich who has left us a voluminous History of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party and a History of the Social-Democratic Party.

Special attention was given to the recruitment, education and professional training of the officers of this police force. At police headquarters, a file was kept on each man, thoroughly documented and including many interesting details. Character, level of education, intelligence and service record were all noted down in an eminently practical spirit. One officer, for example, is described as “limited” – all right for secondary jobs, only requiring firm handling; while another, the file points out, is “inclined to pay court to the ladies”.

Among the many questions on the form, the following are particularly striking: “Does he have a good knowledge of the statutes and programmes of any of the parties? Which parties?” We find that our friend who runs after the ladies “has a good knowledge of Socialist- Revolutionary and anarchist ideas – a passable knowledge of the Social-Democratic Party – and a superficial knowledge of the Polish Socialist Party.” Note the careful grading of learning. But let us carry on examining this same file. Has our policeman “followed courses in the history of the revolutionary movement?” “In which parties has he had secret agents working? How many? Are they intellectuals? Workers?”

Naturally, to train its experts, the Okhrana organised courses in which each party was studied – its origins, its programme, its methods, and even the life-histories of its better-known members.

It should be noted that this Russian police force, trained to do the most sensitive political police work, no longer had anything in common with the local constabularies of Western European countries. Its equivalent is to be found in the secret police of all capitalist states.

...

III. The secrets of provocation

The most important section of the Russian police was unquestionably its “secret service”, a polite name for the provocation agency, whose origins go back to the first revolutionary struggles, developing to an extraordinary degree after the 1905 revolution.

Only policemen (force officers) who had undergone special training, instruction and selection were engaged in the recruitment of agents provocateurs. Their degree of success in this field was taken into account in grading and promoting them. Precise instructions established the very finest details of their relations with their secret collaborators. Finally, highly paid specialists collated all the information supplied by the provocateurs, studied it, sorted it out and cataloged it in reports.

At the Okhrana buildings (16 Fontanka, Petrograd), there was a secret room entered only by the chief of police and the officer in charge of sorting documents. It was the centre of the secret service. Its basic contents consisted of the filing system on the provocateurs, in which we found over 35,000 names. In most cases, though an excess of precautions, the name of the “secret agent” was replaced by a pseudonym.

When, after the triumph of the revolution, these reports fell in their entirety into the comrades’ hands, this made the identification of many of these wretches particularly difficult. The name of the provocateur was to be known to no one but the head of the Okhrana and the officer responsible for maintaining permanent contact with him. Generally only pseudonyms were used, even when the provocateurs signed the monthly receipts for their salaries, which were paid as normally and regularly as to other state employees, for sums ranging from 3, 10 or 15 roubles a month up to a maximum of 150 or 200. But the administration, distrustful of its agents and anxious that police officers should not invent imaginary collaborators, often carried out detailed investigations to check on different branches of their organisation. A fully authorised inspector personally checked up on secret collaborators, interviewed them at his discretion, and either sacked them or gave them a rise. We should add that reports from such inspectors were, as far as possible, carefully checked out against each other.

...

VII. A ghost from the past

Even today we are far from having identified all the agents provocateurs of the Okhrana whose files we now have.

Not a month passes without the revolutionary tribunals of the Soviet Union passing judgement on some of these men. They are met and identified by chance. In 1924, one such wretch appeared, coming back to us from a fifty-year past as though with a sudden rush of nausea – he was a real ghost. This spectre called to mind a page of history, which we insert here simply to project into these sordid pages a little of the light of revolutionary heroism.

This agent provocateur had given 37 years’ good service (from 1880 to 1917) and, even as an old man, was wily enough to give the Cheka the slip for seven whole years.

... Around 1879, the 20-year-old student Okladsky, a revolutionary from the age of 15; a member of the Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will) Party, and a terrorist, planned an attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander II together with Zheliabov. They were going to blow up the imperial train. It passed over the mines without incident. The infernal package had not worked. An accident? So it was thought at the time. But 16 revolutionaries, including Okladsky, had to answer for this “crime”. Okladsky was condemned to death. Was this the beginning of his brilliant career? Or had it already begun? A pardon from the emperor commuted his sentence to life imprisonment.

It was in any case the beginning of the series of inestimable services Okladsky was to render to the Tsarist police. In the long list of revolutionaries he was to hand over, were four names which are among the finest in our history: Barannikov, Zheliabov, Trigoni and Vera Figner. Of these four, only Vera Nicolaevna Figner survived. She spent twenty years in the Schlüsselberg fortress. Barannikov died there. Trigoni, after suffering twenty years in Schlüsselberg and four in exile in Sakhalin, lived just long enough to see the overthrow of the autocracy before his death in June 1917. Zheliabov died on the gallows.

All these brave figures were leaders of Narodnaya Volya, the first Russian revolutionary party, which, before the birth of the proletarian movement, had declared war on the autocracy. Their programme was for a liberal revolution, which if achieved would have been an enormous step forward for Russia. In a period in which no other action was possible, they employed terrorism, constantly striking at the head of Tsarism, driving it mad sometimes, and on March 1, 1881, beheading it. In the struggle of this handful of heroes against the powerfully-armed old society, were forged the customs, traditions and outlook which, carried forward by the proletariat, were to temper many generations for the victory of October 1917.

Of all these heroes, perhaps the greatest was Alexander Zheliabov, and it was certainly he who rendered the greatest services to the party he had helped to found. Denounced by Okladsky, he was arrested on February 27, 1881, in an apartment on the Nevsky Prospekt, in the company of a young lawyer from Odessa, Trigoni, also a member of the mysterious Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya. Two days later, the party’s bombs blew Alexander II to pieces in a St Petersburg street. The following day, the legal authorities received an astounding letter from Zheliabov, jailed in the Peter and Paul prison. Rarely has a judiciary and a monarchy met with such defiance. Rarely has the leader of a party carried out his last duty with such pride. The letter said:

“If the new sovereign, who receives his sceptre from the hands of the revolution, plans to give the regicides the same punishment as of old; if he plans to execute Ryssakov, it would be a crying injustice to spare my life, since I have made so many attempts on the life of Alexander II, and only chance prevented my participation in his execution. I am very concerned that the government may be putting a higher price on formal justice than on real justice, and adorning the crown of the new monarch with the corpse of a young hero, solely for lack of formal proof against myself, a veteran of the revolution.

With all my heart I protest against this iniquity.

Only cowardice on the part of the government could explain why two gallows should not be raised instead of one.”

The new Tsar, Alexander III, in fact had six gibbets put up for the regicides. At the last moment, a young woman, Jessy Helfman, who was pregnant, was pardoned. Zheliabov died alongside his companion, Sophia Perovskaya, Ryssakov (who had turned traitor, to no avail), Mikhailov, and the chemist Kibalchich. Mikhaiov had to suffer being hanged three times. Twice, the hangman’s rope broke. Twice, Mikhaiov fell, wrapped in his shroud and hood, and stood up again of his own accord ...

... The provocateur Okladsky, meanwhile, carried on with his services. Among the open-hearted youth who tirelessly “went to the people”, to poverty, prison, exile and death, to open the way for revolution, it was easy enough to deal hidden blows! Scarcely had Okladsky arrived in Kiev, when he handed over Vera Nikolaevna Figner to the police chief Sudekin. Then he worked in Tbilisi as a professional traitor, becoming an expert in the art of forming relationships with the best men there, gaining their friendship and feigning to share their enthusiasm, in order then one day to point the finger and have his comrades buried alive... and receive the expected gratuity.

In 1889, the imperial police called him to St Petersburg. The Minister, Durnovo, absolving Oksladsky of anything unworthy in his past, turned him into the Hon. Citizen Petrovsky, still of course a revolutionary and the confidant of revolutionaries. He was to remain on “active service” until the revolution of March 1917. Up until 1924 he managed to pass himself off as a peaceful inhabitant of Petrograd. Later, locked up in Leningrad in the very prison where many of his victims had awaited their death, he agreed to write a confession of his life up until the year 1890.

But beyond that date, the old agent provocateur refused to say a word. He would speak only about a past from which scarcely any of the revolutionaries survived, but which he had peopled with martyrs and with dead.

The revolutionary tribunal of Leningrad passed judgement on Okladsky in the first fortnight of January 1925. The revolution is not vengeful. This was a ghost from too remote a past, a past which was dead and buried. The trial, conducted by veterans of the revolution, seemed like a scientific debate on history and psychology. It was a study of the most pitiful of human documents. Okladsky was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment.

VIII. Malinovsky

Let us dwell briefly on a case of provocation of which there are several examples in the history of the Russian revolutionary movement: provocation on the part of a party leader. Enter the enigmatic figure of Malinovsky. [1]

One morning in 1918 – the terrible year which followed the October Revolution, with civil war, requisitioning in the countryside, sabotage by technicians, conspiracies, the Czech uprising, foreign intervention, the infamous peace (as Lenin called it) of Brest-Litovsk, two assassination attempts on Vladimir Ilyich himself- one morning in that year, a man quite calmly appeared before the Commandant of the Smolny Institute in Petrograd and said to him:

“I am the provocateur Malinovsky. I ask you to arrest me.”

Humour has a place in all tragedy. Unmoved, the Smolny commandant nearly showed his untimely visitor the door.

“I have no orders to deal with this! And it’s not my job to arrest you!”

“Then take me to the party committee!”

And at the committee offices, he was recognised, with astonishment, as the most execrable, the most contemptible figure in the party. He was arrested.

His career, in brief, was as follows:

The good side: a difficult adolescence, three convictions for thieving. Very gifted, very active, a member of several organisations, so highly thought of that in 1910 he was asked to accept nomination to the Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, and was elected to it at the Prague Bolshevik Conference (1912). By the end of that year he was a Bolshevik deputy in the IVth Imperial Duma. In 1913 he was president of the Bolshevik parliamentary faction.

The bad side: Okhrana informer (known as “Ernest”, and later “The Tailor”) from 1907. From 1910, he was on 100 roubles a month (a princely rate). The ex-Chief of Police, Beletsky, says: “Malinovsky was the pride of the service, which was grooming him to be one of the leaders of the party.” He had groups of Bolsheviks arrested in Moscow, Tula, etc; he handed Milyutin, Nogin, Maria Smidovich, Stalin and Sverdlov over to the police. He made over secret party archives to the Okhrana. He was even elected to the Duma with the discreet but effective help of the police ...

Once exposed, he received hefty compensation from the Ministry of the Interior and disappeared. The war intervened. Taken prisoner in the fighting, he became an active member again in the concentration camps. Finally he returned to Russia, to proclaim to the revolutionary tribunal: “Have me shot!” He maintained that he had suffered enormously from his dual existence; that he had only really understood the revolution too late; that he had let himself be drawn on by ambition and the spirit of adventure. Krylenko mercilessly refuted this argument, sincere though it may have been: “The adventurer is playing his last card!” he said.

A revolution cannot halt to decipher psychological enigmas. Nor can it run the risk of being deceived once again by a turbulent, impassioned actor. The revolutionary tribunal delivered the verdict demanded by both the accuser and the accused. That same night, a few hours later, Malinovsky was crossing an isolated courtyard in the Kremlin when he suddenly received a bullet in the back of the neck.

...

XI. Russian informers abroad. M. Raymond Recouly

The ramifications of the Okhrana of course extended abroad. Their archives contained information on the large number of people then living beyond the frontiers of the Empire, including some who had never been in Russia at all. Although I only came to Russia for the first time in 1919, I found a series of files on myself. The Russian police followed the activities of revolutionaries abroad with the greatest attention. On the case of the Russian anarchists Troianovsky and Kirichek, caught during the war in Paris, I found voluminous files in Petrograd. They included the complete report of the inquiry held in the Paris Palace of Justice. For the rest, be they Russians or foreigners, the anarchists were everywhere kept under special surveillance by the Okhrana, which for that purpose maintained a constant correspondence with the security services of London, Rome, Berlin etc.

In every major capital city there was a Russian police chief in permanent residence. During the war, M. Krassilnikov, officially an adviser at the embassy, occupied this delicate position.

At the time the Russian Revolution broke out, some 15 agents provocateurs were operating in Paris in the different Russian emigré groups. When the last ambassador of the last Tsar had to hand over the legation to a successor appointed by the Provisional Government, a commission consisting of highly-regarded members of the emigré colony in Paris undertook a study of M. Krassilnikov’s papers. They identified the secret agents without difficulty. Among other surprises, they found that a member of the French press, who had always appeared to be a good patriot, had been around the Rue de Grenelle as an informer and spy. He was M. Raymond Recouly, then a journalist on Le Figaro, where he was in charge of the foreign desk. In his secret collaboration with M. Krassilnikov, Recouly, following the rule for informers, had changed his name to the not-very-literary pseudonym of Rat-Catcher. A dog’s name for a dog’s job. The Rat-Catcher reported to the Okhrana on his colleagues in the French press. He put forward Okhrana policy in Le Figaro and elsewhere. He was paid 500 francs a month. His activities are notorious. They can be read about complete, in printed form; they were apparently published in Paris in 1918 in a voluminous report by M. Agafanov, a member of the Paris emigrés’ commission of inquiry into Russian provocateurs in France. The members of this commission – some of whom must still be living in Paris – will certainly not have forgotten the Rat-Catcher Recouly. René Marchand, meanwhile, in 1924, published in L’Humanité proof, taken from the Okhrana’s Petrograd archives, of M. Recouly’s police activity. This gentleman did no more than issue a denial which no-one believed, yet he was not rejected by his colleagues. [7] And for good reason. Given the extent of the corruption of the press by foreign governments, his case was not very remarkable.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emancipation of Russian Serfs

A.D. 1861

ANDREW D. WHITE — NIKOLAI TURGENIEFF

By the act that freed the serfs in Russia, Alexander II, to whom it was in great measure due, obtained a place of unusual honor among the sovereigns that have ruled his nation. It was the grand achievement of Alexander's reign, and caused him to be hailed as one of the world's liberators. The importance of this event in Russian history is not diminished by the fact that its practical benefits have not as yet been realized to the full extent anticipated. In 1888 Stepniak, the Russian author and reformer, declared that emancipation had utterly failed to realize the ardent expectations of its advocates and promoters, had failed to improve the material condition of the former serfs, who on the whole were worse off than before emancipation. The same assertion has been made with respect to the emancipation of slaves in the United States, but in neither case, does the objection invalidate the historical significance of an act that formally liberated millions of human beings from hereditary and legalized bondage. In the two views here presented, the subject of the emancipation in Russia is considered in various aspects. Andrew D. White's account, being that of an American scholar and diplomatist familiar with the history and people of Russia through his residence at St. Petersburg, is of peculiar value, embodying the most intelligent foreign judgment. White's synopsis covers the entire subject of the serf system from its beginning to its overthrow. Nikolai Turgenieff, the Russian historian, writing while the emancipation act was bearing its first fruits, describes its workings and effects as observed by one intimately connected with the serfs and the movement that resulted in their freedom.

Read the manifesto below (in Russian).

http://schoolart.narod.ru/1861.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

May 2018 bookhaul

New books:

The Gloaming

The Illumination of Ursula Flight

A Young Doctor's Notebook

Diaboliad and Other Stories

The White Guard

A Dog's Heart

Notes on a Cuff and Other Stories

The Fatal Eggs

The Surface Breaks

Marina

When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit

Circe

The Meaning of Mary Magdalene

The Buried Giant

The Astonishing Color of After

The Wicked Deep

Second hand books:

The Defiant Life of Vera Figner

Books I borrowed from the library:

The Strange and Beautiful Sorrow of Ava Lavender

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

💟..It’s an interesting fact that we have the Russian woman of 1917 led by Poliksena Nestorovna Shishkina-Lavein and Vera Figner to thank for international Women’s Day . It was on February 23, in the old Russian Calendar (now March 8th) that forty thousand Russian woman took to the streets to demand change . Although it was in 1913 when the official woman’s day holiday was first celebrated. The 1917 revolution of woman paved the way to change. 💟 So my call goes out to all the Russian woman who fought hard for their rights and of course for all that have waged this constant crusade since and before this time, from all the countries in the world. 💟 When I started to write this post , I wanted to talk about the famous woman who worked so hard for their rights , and then thought , how is that possible ? It’s about all of the minds that have written , talked , argued, been victimised , spat on , made fools of .. etc . It’s about all Those people you and I know personally , who are constantly working for change and fairness , that’s not just about gender , it’s about all inequalities and injustices that woman have fought for and have strived to change . Because I personally know a few , whose energy on this mission and mental strength to fight about the rights and safety of animals, racism and poverty and the environment is quite amazing. 💟 And it’s also strange to me , being a zodiac junky , that this day falls in Pisces . And I happen to know a lot of Pisces woman who think, voice and battle for fairness and justice and whose emotions are affected deeply by the injustices in this world . So really and truly it’s about everyone , your girl friends , your mothers , wife’s, bosses , workers . It’s about all the amazing girls we know who’s passion for humanity is overwhelming . (at London, United Kingdom) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9d-D7chw7t/?igshid=h869h93a91b6

0 notes

Video

youtube

Nikolay Figner (Николай Фигнер) sings “Oh, give me oblivion” (”О дай мне забвение, родная”)

As you have probably guessed, I’ve spent the past week listening to various versions of this aria - there aren’t a lot of other bits of ‘Dubrovsky’ available on youtube - the whole or this.

I first heard about Nilolay Figner (the role of Gherman in ‘Pilovaya Dama’ was written for him) long before my absession with opera started - at uni we studied the Narodovolcy organization (they contributed to the abolition of slavery in Russia and eventually murdered tzar Alexander II) in minute detail as one of our prossessors was a fanboy/expert on the topic and I got fascinated by one of the highranking members of this group - Vera Figner (this woman still, to this day holds the record of the longest run from the Russian political police - 5 years on the run!) Since that time, I’ve been fascinated by the dillemma: was it more bizarre for a famous operatic tenor to have a major political terrorist for a sister or the other way round?

#opera#my opera shananigans#Dubrovsky#Nikolay Figner#and actually their other sister also was a revolutionary

0 notes