Text

Hey, everyone! I hope all is well. Here: I created a shareable link at Wiley’s Online Library to the comparative essay on Merleau-Ponty and Nagarjuna that I got published in the Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, a journal published by Wiley on behalf of Drexel University in Philadelphia. I hadn’t realized that WOL is one of the world’s largest academic publishers. It was a pleasant surprise, indeed. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jtsb.12372

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jtsb.12372

0 notes

Text

2023 has gotten off to a great start! A philosophy research paper of mine on Merleau-Ponty and Nagarjuna was published online by the Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. It should be published in print by the end of the year or early next year, the latest. You can read the abstract here, though you’d have to pay to read the essay itself: http://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12372

#blog#journal#academia#philosophy#merleau-ponty#nagarjuna#buddhism#existentialism#phenomenology#ethics#compassion#sympathy#morality#themiddleway#mahayana

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nietzsche by Lou Salomé (a book review)

“Deep tension, stress, and illness, Nietzsche saw as preconditions for the activity of the mind. This should not be misconstrued as a ‘flight into illness’—as Nietzsche’s long, periodic bedridden spells and darkened chambers might suggest—but as a dangerous ‘experimental philosophy as I live it, even with the possibilities of the most thoroughgoing nihilism,’ for the sake of seeking knowledge.” – Siegfried Mandel

“[T]he total significance of Nietzsche’s interpretation of the historical battle between master and slave mentalities is nothing less than a radically simplified illustration of what transpires in the superior individual and what must split him into a sacrificial god and a sacrificial animal.” – Lou Salomé

I don’t know how it took 16 years of obsessing over Nietzsche and wishing I could read Lou Salomé’s thoughts on him to finally find out that she wrote an entire book on the man! And what a book it was! Damn, could she write! It was published in 1894, five years after Nietzsche’s collapse into madness and six years before his death. It gave me a whole new insight into his thoughts, philosophical transitions and the way he came to his psychological conclusions about human nature and philosophy. I read the Siegfried Mandel translation and his fabulous, in-depth introduction, contextualizing Nietzsche’s life and his relationship with his mother, sister, Paul Reé, the Wagners and of course Salomé herself.

What stands out for me the most in the book, and is at the core of it, is Salomé’s explanation of what Nietzsche meant by “What does not kill me makes me stronger” (or “…destroy me…”, as Mandel’s translation has it). I, like most, completely misunderstood it. First of all, he says “me” because he literally was referring to himself. It isn’t some absolutist claim that is meant to be applied to everyone. He was being as autobiographically pithy in a maxim as he possibly could be. Second of all, I always thought that, by “stronger,” he meant physically and emotionally stronger via overcoming (given overcoming is a cornerstone of Nietzschean thought), but that is completely wrong. What he meant by stronger was his strength (or sharpness) of mind, determination, intellectual thinking, life-affirmation and his assurance of immortalization through his ever-strengthening body of work. Salomé says that he took that maxim and “flagellated himself” with it, “not to the point of destruction or death but to a fever-pitch and a self-wounding he deemed necessary. This seeking of pain courses through the entire history of Nietzsche’s development and is its essential intellectual and spiritual source” (p. 14):

“[H]is powerful nature was capable of self-healing and pulling things together, in the midst of pain and contradictions; healing was prompted by strivings for the ideals of knowledge. But after recovery was achieved, his nature inexorable again required suffering and battles, fever and wounds” (p. 23).

Basically, he was constantly falling into sickly states. However, he did not allow them to be in vain. He’d use them to better understand himself and others in states of suffering, and in doing so, he’d be filled with the excitement brought on by new ideas, philosophical avenues and subterranean paths within his mind which he would have never discovered or ventured on otherwise. Salomé writes,

‘I recall something that Nietzsche told me which very appropriately expresses the joy that the seeker of knowledge takes in the vast breadth and depth of his nature; from it springs the desire to regard his life henceforth as “an experiment of the seeker of knowledge” (GS, 324). He said, “I resemble an old, weather-proof fortress which contains many hidden cellars and deeper hiding places; in my dark journeys, I have not yet crawled down into my subterranean chambers. Don’t they form the foundation for everything? Should I not climb up from my depths to all the surfaces of the earth? After every journey, should one not return to oneself?”’ (p. 22).

And so, by virtue of his new discoveries, he would begin intense contemplation of them, ceaselessly working through them in his writing, burning the candle at both ends, as he says in Ecce Homo (his autobiography), with his zeal and exuberance of life increasing and increasing as his inexorably ardent strength of will coursed through him and his mind soared heights he never could have imagined. And then, when the journey was over, out of sheer exhaustion, he would “return” to himself—and crash. He’d fall, bedridden, into severe migraines and fevers. He says in Ecce Homo that Human, All Too Human, which he says he wrote to help heal and overcome his sickly condition, was written between bouts of throwing up copious amounts of phlegm, which is the reason he had to write aphoristically, given he couldn’t write for very long periods of time, due to his horrible vomiting, migraines and eyesight. And then, in his newly sick feverish state (one bout almost killing him in 1879), new ideas would once again emerge, and it would all start all over again—a Nietzschean cycle.

“And so, two things stand out emphatically: the close connection between the life of the mind and the life of the soul—the dependence of his intellect upon the needs and excitations of his interior being. And then the unique feature, that this close relatedness must always yield anew to suffering; the light of knowledge requires the high glow of the soul, each time. . . . suffering is natural and necessary to Nietzsche’s existence” (p. 14).

Nietzsche believed, so says Salomé, that “a constant enduring and wounding may yield the greatest possession and creativity” (p. 18). This, she explains, is the crux of his view of “heroism as an ideal.” It is the demanding of more and more of oneself—no matter what the toll.

“His illness necessitated taking himself as the material of his thought, as well as the submission of his self to a philosophical world-picture and the spinning out of it from his own inner being. If all this were otherwise, perhaps he would not have been able to accomplish things so individualistic and unique. And yet, one cannot help but look back with deep regret upon this turning point in Nietzsche’s fate and that uncanny compulsion toward self-isolation. One cannot escape the feeling that the greatness reserved for him passed him by” (p. 56).

As is well known of Nietzsche and is intrinsic to his life and impassioned philosophy, “Instead of seeking to yoke his drives, he gives them all possible free rein; the broader the fields they explore with all their senses, the more they serve the individual’s purpose—a drive for knowledge” (pp. 19-20). It is this striving that would lead him to one new phase in his philosophy after another, which is why we have an early Nietzsche (The Birth of Tragedy), a middle Nietzsche (the one of positivism found in the works he published between 1878 and 1882) and a late Nietzsche (post-1882), from Thus Spoke Zarathustra onwards (the Nietzsche who turns his back on positivism and relies more on emotions, passions, sensations and instincts). “Nietzsche’s uniqueness later was marked by his taking problems almost exclusively from the inner world and subordinating logic to the psychological” (p. 33), hence so much of his influence on Freud, whom Salomé worked with and also wrote a book about, and the title of Kaufmann’s classic 1950 book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Salomé explains that:

‘For good reasons Nietzsche did not enter philosophy by way of abstract academic specializations; he pursued studies towards a deeper conception of the philosophic life and its innermost meaning. And if we wish to designate the goal intended by the peregrinations and battles of his insatiable spirit, we may not find a more appropriate phrase than his longing to discover “a new, and hitherto undiscovered possibility for the philosophical life”’ (HATH, 261) (p. 37).

And so, “Nietzsche’s theory of knowledge culminates in a kind of personal thrall in which the concepts of madness and truth are inextricably entwined” (p. 99).

I hadn’t realized just how thoroughly Nietzsche had ripped himself away from positivism in his works after The Gay Science, despite me having read and studied them all thoroughly on my own and at an undergraduate and then graduate level. Salomé allowed me to see that the superiority of the overman isn’t merely knowledge-seeking to the ultimate extreme, no. It is even beyond that. It is the creating and expanding of the very parameters and possibilities of knowledge itself. That is what makes the labyrinth of Zarathustra, the knocking down and vanquishing of all the limiting walls of human reason, logic and rationality, dissolving them into a philosophical and mystical realm of infinite horizons unlike which the world has ever known, without the need to have to turn to a nonexistent god in order to do so, for Nietzsche remained thoroughly atheistic till the very end. He always remained searching towards the truth, using everything at his disposal to head fearlessly towards it, not blindly clinging to that which wasn’t there in the hope of having found it, as with theism.

One thing that greatly surprised me and gave me much pause is that it turns out Nietzsche’s eternal return (or recurrence) was not merely a philosophical construct and existential experiment for him. He believed it to be a fact of reality and was planning on taking a break from writing, to study the natural sciences for ten years at the University of Vienna or Paris, in order to then prove to the world using science that the eternal return is the actual state of things (in modern terms that would mean the Big Crunch causing the Big Bang, like a snake biting its tail). His illness didn’t permit him to do that, however, and, at any rate, when he realized he wouldn’t be able to prove the eternal return on empirical grounds (using physics experiments, like he was planning on doing), he accepted it on mystical ones founded on “an inner inspiration—his own personal inspiration” (pp. 131-133), despite the fact that, given all his suffering in life, the eternal return was something unspeakably terrifying to him:

“Unforgettable for me are those hours in which he first confided to me his secret, whose inevitable fulfillment and validation he anticipated with shudders. Only with a quiet voice and with all signs of deepest horror did he speak about this secret. Life, in fact, produced such suffering in him that the certainty of an eternal return of life had to mean something horrifying to him. The quintessence of the teaching of eternal recurrence, later constructed by Nietzsche as a shining apotheosis to life, formed such a deep contrast to his own painful feelings about life that it gives us intimations of being an uncanny mask” (p. 130).

And it is also in Zarathustra, the harbinger of the eternal return, where, Salomé explains, we find the evidence that Nietzsche saw his madness coming and walked directly towards it. That is his infamous “abyss,” where no one else may pass and where Zarathustra would forever be alone. “Quite early Nietzsche had brooded over the meaning of madness as a possible source of knowledge and its inner sense that may have led the ancients to discern a sign of divine election” (p. 145), that is, someone severe and worthy enough to be esteemed, followed and exalted. And so he affirmed his own madness, willing it within the realm of amor fati.

“The picture of madness stands at the end of Nietzsche’s philosophy, like a shrill and terrible illustration of theoretical knowledge and of the conclusions drawn from it for his philosophy of the future, because the point of departure is formed by dissolving everything intellectual and letting drive-like chaos dominate. Nietzsche’s theory of knowledge, however, goes beyond the decline of the knower and conceives a revelation by life, inoculated by madness . . .

Madness was to bear witness also to the power of life’s truth through whose brilliance the human spirit is blinded. For no power of reason leads into the depths of life in its fullness. It does not permit a climbing into its fullness step by step or thought by thought . . . ” (p. 150).

‘For us, the outsiders, we can see that from then on Nietzsche was shrouded in the total darkness of night; he stepped into the most individual life of his inner experience before which the ideas that had accompanied him had to come to a halt; a profound and shattering silence spreads over these matters. Not only can we no longer follow his spirit into the last transformation, which he achieves through self-sacrifice, but also we ought not follow it. For in this transformation Nietzsche found proof for his truth, which has become completely merged with all the secrets and seclusions of his inwardness. During his last loneliness, he has drawn away from us and has closed the gate behind him. At the gate’s entrance, however, these words radiate towards us: “‘What hitherto has been your ultimate danger has now become your ultimate refuge. You are on your way to greatness, and that must be of greatest courage to you because there is no path behind you! . . . Here no one may sneak after you! Your own foot has obliterated the path behind you, and above that path is written: Impossibility’”’ (“The Wanderer,” Z, III) (p. 151).

And so Nietzsche’s final phase was complete isolation and separation from the herd through madness, lost yet found inside his own mind, just as he predicted in his Zarathustra. And with that, he answered the very question he asked Salomé about his very mode of overcoming one realm of philosophy in order to embrace and explore new truths:

‘Speaking to Nietzsche about the changes that already lay behind him, I elicited from him remarks he made half in jest. “Yes, things take their course and continue to develop, but where to? When everything has taken its course—where does one run to then? When all possible combinations have been exhausted, what follows then? How would one then not arrive again in belief? Perhaps in a Catholic belief?” And from the backward hiding place of these assertions emerged the added, serious words: “In any case, the circle could be more plausible than a standing still”’ (p. 32).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

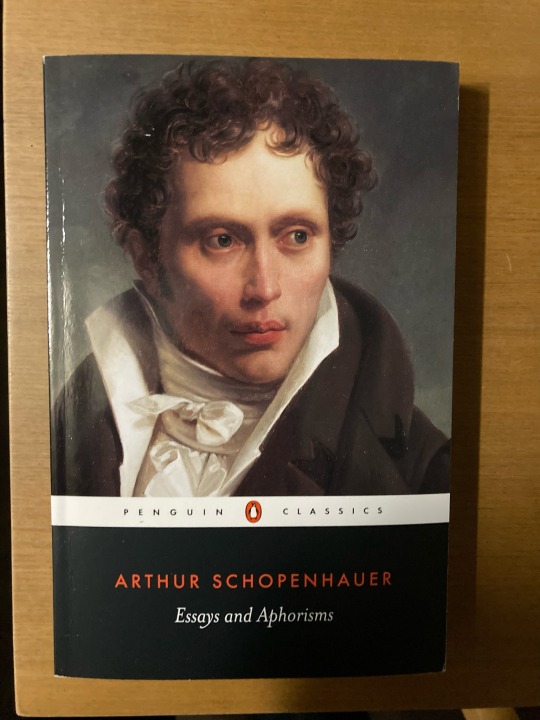

"No rose without a thorn. But many a thorn without a rose." - Schopenhauer, "On Various Subjects," II, B

I finally read the Essays and Aphorisms of Schopenhauer published by Penguin, and I was blown away by it! He'd been on my reading list for ages, and I never thought I’d enjoy him this much! I clearly see how much he influenced my favourite philosopher of all, Nietzsche (who used to be his disciple until he became his greatest critic), in both style and thought - both incredible writers and thinkers, filled with passion and wit. I also didn’t expect to agree with him on so many things. In many ways, he, like Nietzsche, was ahead of his time. Geniuses, pure and simple, and, like many a genius, neither one was truly appreciated until after leaving this world, though Scho did have some disciples in old age.

There’s nothing I love more than a deep thinker who expresses his thoughts with both eloquence and humour, and Scho certainly gives both at full throttle. I love his prosaic and aphoristic style, saying so much in so little space while, most importantly, being crystal clear about what he’s saying, unlike Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, which is incoherent and filled with run-on sentences. I found no wisdom in Hegel, whom I did a directed reading on in the final year of my undergraduate degree, along with Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason, which I found almost as awful, but I find tons of wisdom in Schopenhauer! I in particularly loved his critique and mockery of religion (namely Christianity and the church’s bloody history), his work on human psychology and the unconscious half a century before Freud, his annoyance with the mob and their lack of thoughtfulness and subtlety, his analyses of different mythologies and his criticisms of the writers of his day, in particularly the sensationalism spread by journalists, which he saw through as clear as day. R. J. Hollingdale's Introduction was fantastic as well! One of my favourite things in the book came early on - the best rebuttal I’m yet to see to Leibniz's apologetical claim (against the problem of evil) that this is the best of all possible worlds:

“Even if Leibniz's demonstration that this is the best of all possible worlds were correct, it would still not be a vindication of divine providence.

For the Creator created not only the world, he also created possibility itself: therefore he should have created the possibility of a better world than this one.” - Page 48

YESSSSSSSSSSS!!! SO MUCH YES!!! Bravo, Scho . . . BRAVO!

#philosophy#Schopenhauer#iconoclasm#existentialism#religion#god#will#literature#writing#reading#book

0 notes

Text

“We might say that the problem of authentic growth in a person’s life is to get rid of neurotic despair so as to come face to face with real despair, and then make a creative solution of his existence in greater freedom and full knowledge. This is the conclusion of Kierkegaard’s teaching now supported by the full weight of a mature scientific psychology.” - Becker, p. 206

Becker was one hell of a writer and thinker, one of the greatest (of both, actually), and arguably the profoundest and most important philosopher of the 20th century. He covers so much in this 199-page book (plus detailed endnotes) that I dare not try to summarize it in a review. But it’s the third book of his that I read (the other two being The Denial of Death and Escape from Evil), and he’s blown my mind once again, digging so penetratingly deep into the human psyche and unconscious, using psychology, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, and sometimes even film, to get a point across. From primate state, to tribal state and creature of symbols that accursedly has self-consciousness and realizes its own mortality, to modern-day hero-seeking man lost in the concrete wilderness of modern civilization, fragmented within himself and disconnected from his true, authentic self while not realizing it and that it is his lifelong neurosis along with the baggage of his childhood upbringing, hopelessly trying to justify his absurdly short time in a seemingly meaningless universe with no inherent purpose offered or any rationally objective cosmic roadmap to follow from cradle to grave, Becker takes you through the journey of human evolution from the prehistory of humanity to the modern-day, forlorn individual destined to die and know it. He states that “we can flatly and empirically say that everyone is neurotic, some more than others” (p. 151). Becker lays out all the ways society, culture, politics, business, materialism, religion and even dialogue between people try to give us the illusion of strength, hope, security and significance in order to appease our unconscious by assuring it that we’re more than just finite beings destined for permanent cessation. “Generally,” he says on page 33, “the more anxious and insecure we are, the more we invest in these symbolic extensions of ourselves.” This is why after I read The Denial of Death a little over 12 years ago, I never bothered to do a book review of it at all, despite how much I loved it, as he covered way too much in it, and my intimidation was justified.

0 notes

Text

My two new scorpion necklaces. Together, they make a heart. Red is my favourite colour, and black and red is my favourite colour combination.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Check out what I got myself for my birthday off Etsy - the iconic Sigil of Baphomet. It’s 23.4 inches, and I’m abso-fucking-lutely in LOVE with it! It’s hand-crafted and came with free shipping all the way to Tokyo from the Ukraine. It reaches down and touches my very heart, the greatest gift I could have possibly bought myself - for it mirrors my very core and being. Hail Satan!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Escape from Freedom - a Book Review

“[E]ven being related to the basest kind of pattern is immensely preferable to being alone. Religion and nationalism, as well as any custom and any belief however absurd and degrading, if it only connects the individual with others, are refuges from what man most dreads: isolation.” - page 18

Escape from Freedom was the third book of Erich Fromm’s that I read. It had been on my reading list ever since I took a fabulous psychology course when I was an undergrad called Personality. I highly recommend this seminal masterpiece! It’s Social Psychology and an exposition on why it is that the majority of people do not want to embrace their freedom but in fact run away and hide from it, due to how terrifying it really is on the human psyche in a vast, uncaring universe and world filled with hoards of people who contribute to our feelings of smallness.

One of the things it deals with is the rise of capitalism and how it turned humans into anxiety-ridden, self-doubting, insignificant cogs and addresses capitalism's negative effects and parallels with politics. Fromm explains in which ways capitalism and the Reformation made people freer while also "enslaving" them for their own purposes in different ways than Europeans were "enslaved" in the Middle Ages and how and why people unconsciously run away and escape from the freedom both systems offer. The systems then feed on that for a vicious cycle where man now feels more insignificant and powerless than ever.

Fromm also deals with sadomasochistic relationships and why such symbiotic relationships exist as an unconscious way of overcoming feelings of individual powerlessness, self-doubt and insignificance by losing oneself in another person, either as a way of expelling feelings of weakness via a facade of power that is in actuality merely inflicting abuse on a helpless, subservient subject or by relinquishing all sense of self and individuality as an object of masochism and helplessness, giving all power to the sadist in the process.

This leads him into a discussion on the authoritarian personality that gave rise to Nazi Germany. He also goes into great detail about the political and social circumstances in Germany post-World War I and how they affected the different economic classes that led to Nazism and why those classes reacted in the ways they did as a defence mechanism. The ways in which the masses can be manipulated are fascinating, and it is extremely imperative that they be understood.

I especially enjoyed the section on hypnosis and dream analysis and how so many of our thoughts and feelings come from without rather than from within. He expounds on the ways we try to rationalize those thoughts and feelings as being our own, just like in hypnosis; only media and societal hypnosis is what fools/hypnotizes the masses on a grand scale as we internalize both media and society without even realizing it.

He also elaborates on where he is in agreement with Freud, and where he believes Freud went wrong. Fromm covers so much in this book, and anyone who’s interested in psychology, sociology and/or philosophy should definitely give it a read. It is absolutely profound and was groundbreaking for its time and will always be relevant within the study of human nature and the dangerous path the human race tends to tread on. And the solution that he posits for the problem is a very Nietzschean one, which I love: the individual living creatively and spontaneously for the full realization and cultivation of the self and the true, positive freedom that is realized and experienced along with it.

“The problem we are confronted with today is that of the organization of social and economic forces, so that man - as a member of organized society - may become the master of these forces and cease to be their slave.” - page 269

Rating: five stars!

0 notes

Text

Staring at the Sun - a Book Review

“[D]espite the staunchest, most venerable defenses, we can never completely subdue death anxiety: it is always there, lurking in some hidden ravine of the mind. Perhaps, as Plato says, we cannot lie to the deepest part of ourselves.” - Pages 5-6

I haven’t written a book review in a long time, but after reading this existential, psychological masterpiece, I feel I must.

I’ve always been tormented by the fact that I’m going to die one day. It began suddenly when I was eight years old. However, given I was raised Catholic, it was the terror of burning in hell for all eternity that consumed me. Thankfully, though, I started doubting the existence of God when I was 17. After some time, the doubt finally erupted in full fruition when I was 24, permitting me to completely come to my senses and stop believing in any of that eschatological nonsense. I became an atheist without any belief in the afterlife whatsoever (though I'd like to be wrong about that and am open to the possibility of one).

My death terror then became about ceasing to exist completely and the universe going on and on forever and ever without me after I’m gone, blotting me out as if I never existed at all. It’s that thorough, unrelenting feeling of insignificance coupled with never being able to be aware of anything again that now gets me, and it’s only gotten worse with age (I’m turning 40 in July) due to the inexorable speed of time and my worldly-centred, fiery love of life. Leaving this world, and my mind ceasing for all eternity, absolutely terrifies me! The whole thing seems like a sick, twisted, impossible joke!

“The frightening thought of inevitable death, Epicurus insisted, interferes with our enjoyment of life and leaves no pleasure undisturbed. Because no activity can satisfy our craving for eternal life, all activities are intrinsically unrewarding. He wrote that many individuals develop a hatred for life - even, ironically, to the point of suicide; others engage in frenetic and aimless activity that has no point other than the avoidance of the pain inherent in the human condition.” - pg. 78

Something that’s always fascinated me is how people deal with their own mortality, which is why one of my favourite books of all time is The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker. It’s so deep, razor sharp, eloquent and penetrating. So when I heard of Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Terror of Death by Dr. Irvin D. Yalom, author of Existential Psychotherapy and When Nietzsche Wept, I simply had to get it, in the hope that it would help appease all this dreadful fear and anxiety within me while I delved deeper into a topic that I find absolutely enthralling.

Well, I finished it on the train ride home yesterday, and it was a truly brilliant, unabashed look at death head on. Dr. Yalom uses many of his case studies from personal sessions and successes with patients suffering from death terror and death anxiety. Sometimes he had to reveal to his patients, as it was revealed to him in doing so, that death anxiety was at the heart of what was the matter with them, the dilemma at their emotional and psychological core. Often their struggle with death was really just their struggle with regret and the fear of dying without fulfilling their lives. He also talks about close friends and mentors he’s had, and how they’d helped and learned from each other before they inevitably passed on. And his dream analyses of his patients are absolutely amazing, almost as if executed with acute precision.

One thing I really enjoyed and was delighted to see was that he talks a lot about Epicurus and Nietzsche in it, two philosophers I love greatly, especially Nietzsche. He uses their existential thoughts on mortality, living, and nothingness post-death in his therapy sessions with his patients who are having death anxiety, experiencing a life crisis or are at a crossroads. He even reads Nietzsche’s eternal return passage with the demon and the spider to his patients who might gain value from it, and often do, which then accelerates the work of the sessions.

One Nietzschean theme is the annihilation of the dread of death through the complete consummation of one’s life through self-cultivation and living life to the fullest. I love that, as it naturally rings so true for me.

As for it helping me - though he offers several ways of thinking and being to help allay death terror (none of them involving an afterlife) - it was the reading through of the book itself that gave me a heightened sense of peace with my own finiteness, which I really started to feel on page 210 or 211 (it’s 277 pages in total up till the end of the Afterword). But such a powerful book as this - at times humorous, by the way - can only affect everyone differently.

“Let’s not conclude that death is too painful to bear, that the thought will destroy us, that transiency must be denied lest the truth render life meaningless. Such denial always exacts a price - narrowing our inner life, blurring our vision, blunting our rationality. Ultimately self-deception catches up with us.

“...raw death terror can be scaled down to everyday manageable anxiety. Staring into the face of death, with guidance, not only quells terror but renders life more poignant, more precious, more vital.” - pg. 276

I agree. And, quaintly, as I walked home in the new area of Tokyo that I live in, I came across statues that I started taking photos of and which led me to a Japanese cemetery that I then proceeded to walk through, through the nature that was intertwined with it. And though my senses were heightened, I felt at peace.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cherry-Picking Biblical Apologetics Debunked

You know what I find as annoying and disingenuous as fuck? When modernist Christians try to have their cake and eat it too in regard to wanting to believe in science, history, and the Bible all at the same time, and so will believe in evolution and act like it doesn’t have any bearing on the validity of the Bible. They simply say that the story of Adam and Eve is to be taken allegorically and that the story of the eating of the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge isn’t necessary to be true in order for Christianity to be true. Meanwhile, according to St. Paul, Christ had to be sacrificed to save the world from the sin that "entered the world through ONE man" (Romans 5:12). "For since death came through a man, the resurrection of the dead comes also through a man. For as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive" (1 Corinthians 15:21-22). So if the story of Eden didn’t actually happen, then there is no need for the sacrifice of Christ. Furthermore, as in that quote from 1 Corinthians 15, Paul (or rather the actual writer of the First Timothy epistle) speaks elsewhere of Adam and Eve as if they're real, historical figures:

"A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety." - 1 Timothy 2:11-15

What a nasty, misogynistic book the Bible is, eh? (And where the hell does the writer of First Timothy get off saying that it wasn't Adam who was deceived. It's pretty clear from Genesis 3:6 that, since both ate the forbidden fruit, BOTH of them were in fact deceived.) And they don’t only play this cherry-picking game with the story of creation and the fall of man. They conveniently play it throughout the Old Testament, for example with the story of Noah and the flood, and the talking, burning bush, and the splitting of the Red Sea by Moses, etc., etc. It’s mainly Catholics whom I’ve encountered using this form of apologetics, though I know Methodists, Anglicans and other denominations do as well. It's bizarre, though, because, again, Paul speaks of Moses like he was an actual historical person who once existed, for example when he says:

"Nevertheless, death reigned from the time of Adam to the time of Moses, even over those who did not sin by breaking a command, as did Adam, who is a pattern of the one to come." - Romans 5:14

However, they don’t do this apologetical tap dance with the New Testament, and that’s what really gets to me. Because if they’re going to take the OT stories as mere allegories and symbolisms, then, to be logically consistent, they would have to do that with the virgin birth, Crucifixion and Resurrection as well. In fact, Genesis 1:1 - “In the beginning God” - would also have to be taken symbolically, which would ironically make the Holy Bible an atheistic book! In fact, why don’t they do the opposite? Why not claim that it’s the NT that’s purely allegorical symbolism and the OT that’s completely literal, hmmmmmmmmmm??

#apologetics#St. Paul#Christians#Christianity#The Bible#Lies#Iconoclasm#Truth#Reason#Logic#History#Adam and Eve#The Garden of Eden#The Fall of Man#Tree of Knowledge#Old Testament#New Testament#Atheism#Agnosticism#God#modernity#modernism#biblical iteralism#honesty#cognitive dissonance

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

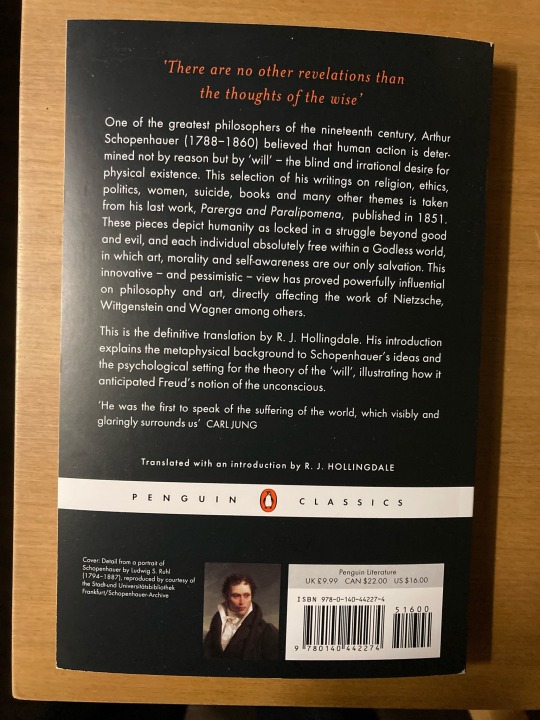

Here they are, all seven of my books on top of each other, from my very first one, “Incorrigibility,” published in April of 2012, at the bottom of the pile, to my brand new one, “Number Seven and One: Poetry, Prose and Polemics,” at the top. My author page: amazon.com/author/raymemichaels

0 notes

Text

Kindle Edition of “Number Seven and One”

Okay, the Kindle eBook of my new publication—my first book of poetry—is now up. Kindle Create was giving me a lot of trouble with it, which is what I was worried would happen. After publication, I wanted to fix a couple of minor errors on my part, but, for some unknown, annoying-as-hell reason, the Kindle Create file had gotten corrupted, so I had to make it again from scratch. However, the bright side of that is: having to do that, allowed me to unsuspectingly find issues caused by Kindle Create itself that I hadn't noticed before, along with three other blunders on my part. So I fixed those silly, pesky mistakes in the paperback too. Ugh, editing is such a fucking beast! What's annoying with KDP is that, after the new version is approved, the changes made don't go live for another 72 hours—so annoying! Anyway, here it is, my heart and soul poured out on paper in prose style, available to you digital lovers in digital form: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08HSDJ3J7

Enjoy!

0 notes

Text

New Release: Number Seven and One

So here it is, the paperback release of my second book of 2020 and my seventh book in total, Number Seven and One: Poetry, Prose and Polemics. It's my first book of its kind and my first book with a preface, which I enjoyed writing and which explains my poetic evolution from the traditional, old-fashioned style I used to write in to what you find in here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08HQ3ZMCC

I feel both incredible and ambivalent sharing myself with the world in this way, but I guess that's to be expected. At any rate, it was super fun and relieving to write, and I'm so happy that I've managed to make the most out of this very strange, turbulent and frightful year—of 2020, the year of the bat!

I hope you're all doing well.

0 notes

Text

New Book: Spirals of Orange and Black

Hello again, everyone. I hope you’re doing well in these very frightful, anxiety-ridden and precarious times. Just hang in there, and we’ll all get through it. It’ll just take some time. Make sure you’re exercising, sleeping well, taking vitamins, staying in as much as possible and eating right. The good news is, I’ve published my new book! It’s my first book of short stories, and I’m very excited about it. There are 19 stories in total, some true, some fictional, some of them even memoirs. If you’d like more detail, please check out the description box at the Amazon landing. Here’s the paperback: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B086FYBSLZ/

And here’s the eBook, which is on sale for only 99 cents, but only for this week; then it’s going back to its normal price: amzn.to/3arY4cH

And you can find all six of my books here: amazon.com/author/raymemichaels

0 notes

Text

Podcast Appearance

I did this podcast last Sunday night to promote my new book, The Chaos Cafe, along with my other four books as well: https://youtu.be/33Jw_N2EL6Y It was my second time on the show. The last time was to promote my sci-fi sex comedy, Even on Mars, which came out last year. That podcast was done over Skype. This one, however, was my first face-to-face one. Podcasts are always fun to do.

I felt kind of annoyed with myself afterwards for not clarifying better why exactly the heated political conflict between my protagonist, Chris Connolly, and his parents wouldn’t have worked if it took place in Canada. I should have explained further that I needed it to be between actual American voters (people with a REAL stake in the matter), arguing on American soil, so the reader could better sympathize with the impassioned, polarized positions on both sides, despite how inane and absurd his parents’ ideas and beliefs are. That’s why it couldn’t be in Canada, which would have made it a “what’s happening over there” matter rather than a “what’s happening over here” one. I came off in the interview as sounding like I thought a heated argument about Trump couldn’t happen within a family dynamic in Canada, which is ludicrous (as I’ve had so many such heated debates) and not what I meant at all!

Furthermore, Radley asked me in the interview what my fascination with chaos was, and I gave a very detailed explanation of only half the answer. The other half is my love of the fact that because there’s no intrinsic meaning to be found in existence, no inherent purpose in all this, no grand scheme of things and no divine hand doing any guiding, I’m, then, the one who’s fully responsible for the meaning I give my short time in this world and therefore all my failures and victories are my own, and I love and cherish that. There’s self-empowerment and joy in embracing that fact, that reality of things! There’s no cop-out of consolation for any shortcomings within myself or my life as being part of “God’s plan,” because there simply isn’t a God and therefore no divine plan. THAT’S real freedom, and THAT’S what I find so liberating. I agree with Sartre’s worldview and assessment that if theism were an accurate representation of reality, and therefore a deity was setting things in motion for the fulfillment of some teleological end, that there could be no real, substantial freedom for us because we wouldn’t be in full control of our “destiny.” There’d be no possibility of taking the full load of the responsibility of our very existence, due to the fact that everything would be predestined in accordance with the will of an omnipotent overlord rather than our own will. In fact, my own will wouldn’t mean shit. Most people don’t want that responsibility, though, so they put it on “God’s purpose” as the perfect cop-out for all their foibles and disappointments in life. I say, “Fuck that.” As with Camus, I love affirming the absurdity itself. It’s so freakin’ exciting and fantastic to me, and I wouldn’t want things to be any other way. Fuck grand schemes! I’ve got my own “schemes” that I create and toil towards, the outcome mine and mine alone, along with anyone who may have so graciously helped me along the way.

The other thing I wish I stated in the interview is that, at bottom, what bothers both my lead characters in Screw the Devil’s Daiquiri and The Chaos Cafe in regard to their own mortality, is that they see their own future deaths as leaving a gap in the world. However, that mistaken gap they see is both an illusion and self-delusion, and will not come about at all. And they, of course, know that. And there lies the rub, for that gap they see actually lies within themselves. It’s the unbridgeable distance between what they want to be true (that they be immortal) and what is actually true (that they are very much mortal). That gap, then, can only be closed either with 1) the acceptance that they are nothing and that the universe will go on and on for eons, as per usual, after they die and/or 2) what in Buddhism is called “ego death.” For in that actual gap within themselves, it is their egos that are unable to see (at least without serious introspection or someone pointing it out to them) - that there is a gap at all. So instead, the gap is projected into a future time in the external world, instead of seeing it where it actually is, inside them.

Oh, yeah, and I remembered - there’s a scene in my fourth book, Even on Mars, where two sisters are talking, and there’s no one else around. Whether or not a man is around is irrelevant for passing the Bechdel Test anyway. It’s whether or not the two women are talking about something other than a man, and so, yes, that scene passes it by that standard as well - not that that bullshit matters to me anyway.

You can find my books here: amazon.com/author/raymemichaels

undefined

youtube

0 notes

Text

Faces

Two moons’ faces,

So far yet so close.

They stared at each other in wanting,

Of what they feared and loved most.

Attraction and opposition,

Fleeing and engrossed.

A hope for better chapters,

Enamoured with a ghost!

Two moons’ faces glowing,

Reflecting each other’s sun.

Imposing their own powers,

Too blind to see they’re one.

Each elusive to the other,

Forever lost and out of noon.

If only they had sincere reflection,

To know they’re two sides of the same moon.

4/20/2018

0 notes

Text

NEW BOOK RELEASE!!!

Hey, it’s been a while, tumblrs! My new and fifth book (in fact, my second release in 9 months) went up for sale on Amazon last month, a few days before I left Tokyo for a glorious week-long holiday in the paradise that is Cebu, Philippines. The new book? The Chaos Cafe, my most intriguing, entertaining, gripping and philosophical one yet. It's both satirical and suspenseful, keeping you more and more on the edge of your seat as it goes on. It's a dark, urban, existential comedy and fantasy on chaos and a real mind-blender too. I'm heavily influenced by both Woody Allen and Kevin Smith, and the surrealistic style and existential themes often found in the films of the former are certainly apparent in it and my other books as well (except, of course, for my dark, gory, romantic vampire thriller, Red Love), while the contentious, often wacky, dialogue-driven parts clearly have the influence of Smith (check out my first book, Incorrigibility, which was heavily influenced by him and originally written in screenplay form). Philosophy was my major and what I did my master's degree in, and the existential matters covered by Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Sartre and Camus are motifs in The Chaos Cafe.

"That God does not exist, I cannot deny. That my whole being cries out for God, I cannot forget." - Jean-Paul Sartre

Here's the eBook on the Kindle Store: goo.gl/cYXATJ

And here's the paperback - ENJOY: http://goo.gl/yqY5Qr

My author page: amazon.com/author/raymemichaels

0 notes