#ann goldstein

Text

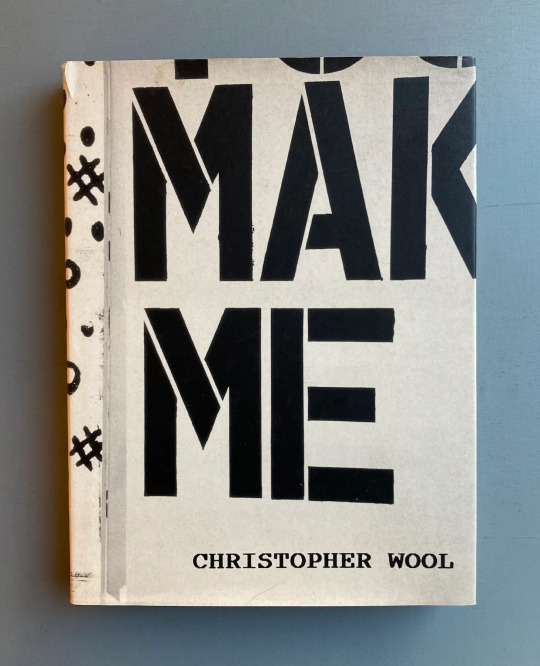

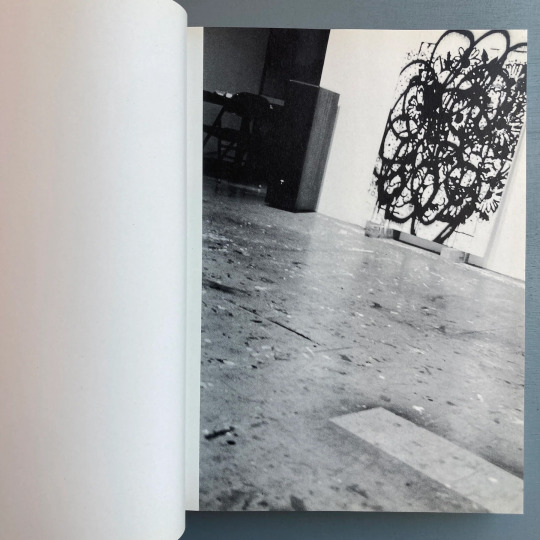

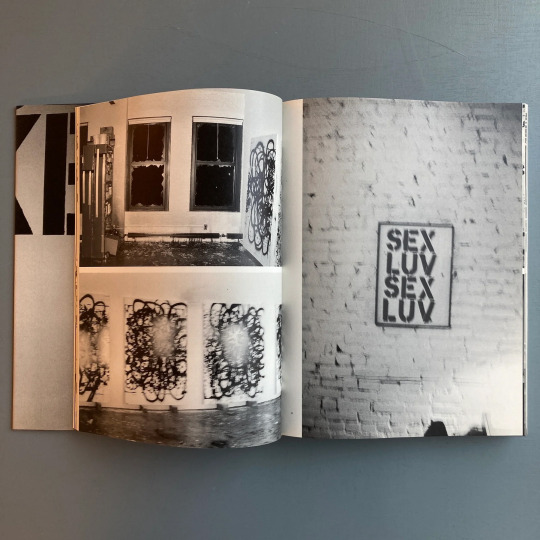

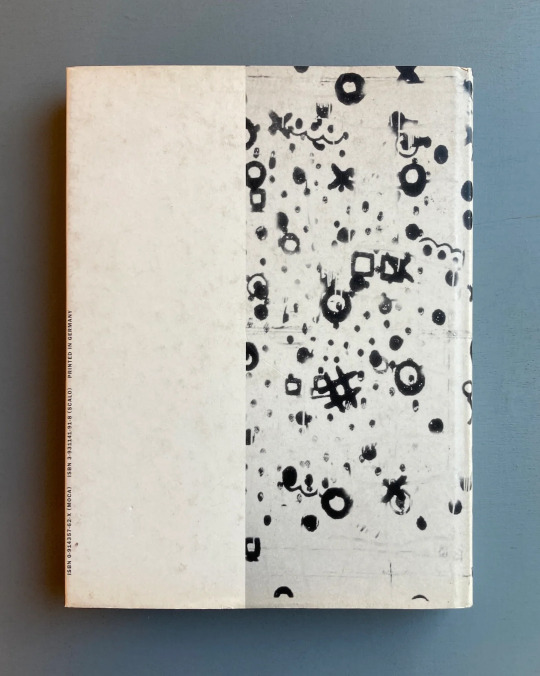

Christopher Wool: 'You make me', (exhibition catalogue), MoCA, Los Angeles, CA, and Scalo Publishers, 1997 [Saint-Martin Bookshop, Bruxelles-Brussel]

Essays: Thomas Crow, Ann Goldstein, Madeleine Grynsztejn, Gary Indiana and Jim Lewis

Cover Art: Christopher Wool, Untitled, (enamel on aluminum), (detail), 1997 [© Christopher Wool]

#graphic design#typography#art#visual writing#drawing#mixed media#exhibit design#catalogue#catalog#cover#back cover#christopher wool#thomas crow#ann goldstein#madeleine grynsztejn#gary indiana#jim lewis#moca#scalo publishers#1990s

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

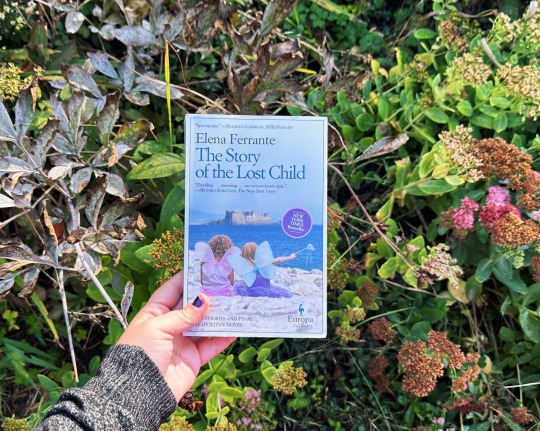

The twist of the final book in this quartet will always take my breath away. I had a hard time reading The Story of the Lost Child knowing what was coming. The taste of dread was in my mouth the whole time, the rising threat in the background, the question, the mystery.

Spoilers ahead. I’ve always been fascinated by the possibilities of these final passages. In the final years, Lenú desperately wants to read the novel she’s certain that Lila must be writing, so much that she writes their novel in an attempt, a hope, that the boundaries will fade between them despite them having grown apart, that somehow Lila’s voice will just intrude, invade, as Lila always seemed to invade Lenú’s life before. Ultimately, Lenú is upset that the boundary she always wanted is set between them for good, that a wall has been erected.

Or, is something uglier going on? Lenú received, read, and tossed all of Lila’s notebooks. Lenú wants Lila’s voice to invade her novel, but it doesn’t. How much of Lenú’s story is truly their story? How much of a reliable narrator is she, given that she is so gifted at lying to herself, that she is so unsure of what’s hers, that she seems to never be able to see what’s right in front of her throughout the series? What doesn’t she understand of Lila, and yet what did she take from Lila, in the end?

#the story of the lost child#neapolitan novels#elena ferrante#lila and lenú#ann goldstein#women in translation#books in translation

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The private becoming public, the individual subject dividing, and the writer becoming her own reader and vice versa—the diary, an elusive, elastic container, straddles all this and more. Diary writing may be the most private of forms, but when placed within the context of a novel or when it serves, as it does here, for the structure of the novel itself, this form of confession, dating back at least in the Western tradition to Augustine, contradicts its very nature.

From Petrarch to Gramsci to Woolf to Lessing, all diaries and notebooks, whether intended for publication or not, whether invented by their authors or not, whether framed as (or within) novels or not, are all dialogues with the self. They are instances of self-doubling and self-fashioning. They are declarations of autonomy, counternarratives that contrast and contradict reality. The fictionalized diary has always been especially appealing in that we get to know the character not only as a person but also as a writer. This additional authorial persona is especially provocative in light of female consciousness, which has struggled to find its place in history and in the literary tradition

—Jhumpa Lahiri, in the foreword to Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes tr. Ann Goldstein

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

elena ferrante never misses

#now lets see if the adaptation hits as well#elena ferrante#books#ann goldstein#translation#bookblr#the lying life of adults#my posts#read#book photos#europa editions#booklr#book photography#literature#litblr#reading

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ann Goldstein knows the works of Elena Ferrante intimately – perhaps more than anyone else in the English-speaking world – but she doesn’t have any great desire to meet her. Goldstein is the literary translator who has brought the Italian author’s novels, most famously the Neapolitan Quartet, to Anglophone audiences. In English, like in the original Italian, they have become bestsellers. Ferrante is beloved for her truthful depictions of adolescent friendship and the pains of womanhood. But “Elena Ferrante” is a pseudonym: the identity of the author is not known to the public, despite numerous attempts to discover her.

Goldstein communicates with Ferrante via her Italian publisher. “It doesn’t really bother me, not to speak to her directly,” she said over Zoom from her book-laden apartment in Greenwich Village, New York City. “The person who writes the books is the person I know, whoever that person is, the consciousness that’s writing the books is someone that I have a dialogue with.” She giggled, as she did frequently, despite being about to say something she must have insisted many times before. “And – by the way – I don’t know who she is. And it’s not me.”

Goldstein was born in 1949 and grew up in New Jersey. She has been translating Italian literature into English since the early 1990s and spent the bulk of her career working in the copy department at the New Yorker, which she joined in 1974. In the late 1980s she became the head of the department, overseeing copyediting and proof-reading. She had studied ancient Greek at university, and can read French “pretty well”, but it was with New Yorker colleagues that she first learned Italian. Over three successive years the group read the trio of books comprising Dante’s Divine Comedy. Goldstein was in her late thirties at the time; it is more difficult to learn a language later in life. “You don’t get the same facility, the same kind of fluency, as if you were a child,” she said, “but you can do something.”

She retired from the magazine in 2017 and has since pursued translation. She still abides by the many grammatical rules instilled in her by four decades at the New Yorker (“things like the serial comma or the Oxford comma – nobody seems to use that any more, which is ridiculous, because it’s so clarifying”). The two halves of her career are distinct yet overlapping. “I do think that proofreading, copy-editing, editing, they have to do with an attention to detail, and of course translation is all about attention to detail. It’s attention to particular words, to sentences, and how words work in a sentence. It’s about getting everything as right as you can, or what you think of as right, from the way the word is spelled – and we might have a difference of opinion about that,” that amused her, “to the way it’s used.”

Goldstein spoke knowingly about her own language (“spelled” could of course be “spelt”) and regularly corrected herself, as though always in pursuit of the most precise way of conveying her meaning. She wore a grey V-neck jumper, dangly silver earrings and thick-rimmed glasses – above which her eyebrows often appeared, jumping up in excitement as she furrowed her brow in concentration and then quickly released it.

Her most recent translation is of Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes. First published in Italy in the 1950s, the novel comprises a series of diary entries by Valeria Cossati, who secretly writes of her deep dissatisfaction with her life in post-war Rome. “I was struck by the fact that it seems – it’s a little bit cliché to say this – but it seems so contemporary. It seems like she’s dealing with the same problems that women have now, or have had since then. This was 70 years ago. The daily struggles are different, but the psychological struggles are so similar.”

The book is also being republished in Italy, where it has been out of print for decades. It marks a “rediscovery”, a reassertion of an author who was successful in her lifetime, but whom the patriarchal cultural memory has forgotten. It was in Ferrante’s Frantumaglia, a collection of letters, essays and interviews that Goldstein translated into English, that she first learnt of de Céspedes, whose life was remarkable by any standard – and of particular interest to the translator, who is fascinated by wartime and postwar Italy.

De Céspedes was the granddaughter of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, who led Cuba’s revolt for independence from Spain and then served as its first president. She was born in Rome, married when she was 15 and had a child aged 17. In 1943 she and her second husband fled to escape the Nazis’ occupation of the capital. “So they spent a month hiding in the woods in Abruzzo!” Goldstein explained, wide-eyed. “She wrote a diary – there’s a little diary that I translated that I’m trying to get published. It’s amazing. I don’t know how she wrote it, but she did, just about being in the woods, and they were slowly being more and more closely surrounded by the Germans. It’s pretty dramatic. She had a wild life!”

Goldstein’s enthusiasm for her authors – and for her part in the “rediscovery” project of an author such as de Céspedes – is evident. The thematic similarity between Forbidden Notebook and many of Ferrante’s works is, she said, a coincidence. “But I do like novels about women – I guess. Though not exclusively. I have done a lot more [books by] women, especially first person narrator women. There’s something about it that is particularly congenial.” She stopped herself. “But I’m always interested in anything!”

She could not, however, explain exactly what she looks for in literature she might translate. She prefers books that are set in Italy, but beyond that – “I don’t really look for anything. Most books, even if they ostensibly don’t seem interesting, end up being interesting for one reason or another, either for translation issues or language issues.”

She doesn’t see herself as a writer as such – “I mean, I’m not writing anything of my own” – and aligns herself instead with the critic Cesare Garboli, who wrote: “To translate is to be an actor.” “The actor is performing,” Goldstein said. “It’s only once, it’s his own personal performance, and nobody else can do the same thing.” Translation is also, she said, “a puzzle. You’re solving puzzles all the time. But in order to solve them, you have to interpret.” And of course there is never just one answer.

For a long time those critiquing the publishing industry spoke of the “3 per cent problem” – that just 3 per cent of books sold in English were in translation. (The statistic has been cited for both the UK and the US.) In the 30 years Goldstein has been translating, she has seen that number grow. “There’s definitely more openness to translations,” she said, citing the proliferation of small presses, including New Directions and Archipelago Books in the US, as leading the charge. “The Ferrante phenomenon” – as she described it – has helped translators receive the credit they deserve. “Because there’s no author, it made people more aware of the fact that there’s a translator involved in the book.”

Goldstein has a personal fascination with Italian culture, but also sees a moral pursuit in reading in translation. “It opens you up to other cultures. We’re all very – well, especially in America – we’re so inward-facing, we’re so solipsistic,” she punctuated her pause with a laugh. “Or, what’s the word! I mean, that’s one word. People don’t attend to other cultures. They don’t pay attention, and they don’t want to learn anything. They don’t want to understand how other people might think, how their neighbours might think. It’s just, the more you know, the better it is. The broader your sense of the world – it can’t help but make you a better person.”

“Forbidden Notebook”, by Alba de Céspedes and translated by Ann Goldstein, is published by Pushkin Press

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

She meant something different: she wanted to vanish; she wanted every one of her cells to disappear, nothing of her ever to be found. And since I know her well, or at least I think I know her, I take it for granted that she has found a way to disappear, to leave not so much as a hair anywhere in this world.

— Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend (trans. Ann Goldstein).

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

is anyone please able to provide page numbers for the sexual assault in the book My Brilliant Friend?

i checked “doesthedogdie.com” for trigger warnings and it said there is sexual violence but didnt specify which pages, and i really would rather not be caught off-guard and triggered by it.

@amulbutter tagging so you see this post bc i know youve read the book, but posting publically in case anyone else could kindly help out 🥲❤️🙏

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

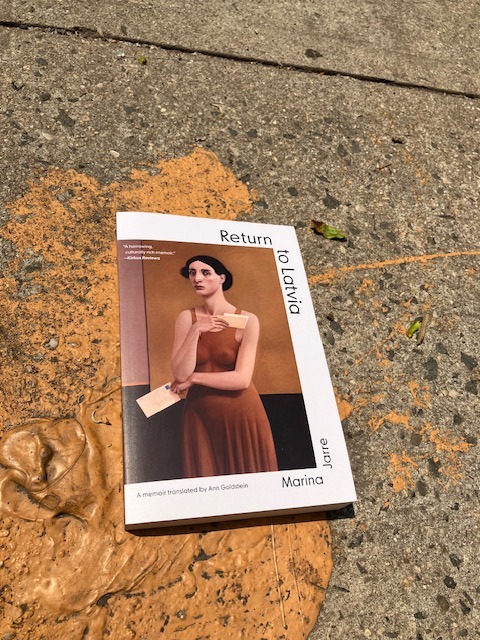

“Ann Goldstein gracefully captures Jarre’s alternation of warmth and indignation, of poignant observation and buried regret—the breadth of a most human writer . . . Return to Latvia is a memoir with real questions about shared history and atrocity. How can we look for the truth when no one will speak it?”—Words Without Borders

https://wordswithoutborders.org/book-reviews/to-tell-is-to-betray-marina-jarres-return-to-latvia/?src=hp

#New Vessel Press#Return to Latvia#Marina Jarre#Words Without Borders#translation#Ann Goldstein#Latvia#Italian literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

shattering the illusion that writing is a place of refuge, and replacing it with the certainty that it is a place that always both pollutes and sabotages us

Valeria is constantly vowing to stop: to stop writing and get rid of the diary, as she discovers harsh and painful truths about herself and her family. But the more acute, honest, and distressing her perceptions become, the more compelling is the desire to will deep writing, to keep digging; and yet ultimately, she has to stop, as a way of self-preservation. In her introduction to the new Italian edition of the novel, the writer Nadia Terranova says, “The genius of Alba de Céspedes in this book is in shattering the illusion that writing is a place of refuge, and replacing it with the certainty that it is a place that always both pollutes and sabotages us.” As Valeria discovers: toward the end of the novel, she tells her daughter, “Save yourself, you who can do it.”

— Ann Goldstein, in “A Note from the Translator” in “Forbidden Notebook: A Novel” by Alba de Céspedes (Astra House, January 17, 2023)

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘the circle of an empty day is brutal, and at night it tightens around your neck like a noose.’

elena ferrante you are SICK (i adore you)

0 notes

Text

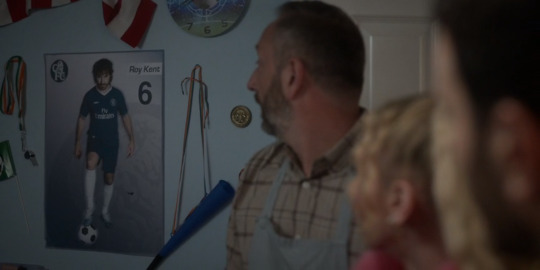

Okay yes I’m happy for Phil and Brett and Hannah and Juno and Jason, I loved this season and they all truly deserved their nom. And Sam, Becky, and Sarah killed it in their guest roles, like absolutely slaughtered it. But Toheeb Jimoh??????????????!!!!!?????????????????? Who BROUGHT IT this season????????????? Nick Mohammed???????? Billy Harris??????????????? And the episodes given noms for writing and directing were both so long, farewell????? When Sunflowers was right there???????????????????????????

#ted lasso#phil dunster#brett goldstein#hannah waddingham#juno temple#jason sudeikis#toheeb jimoh#billy harris#nick mohammed#sarah niles#becky ann baker#sam richardson

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

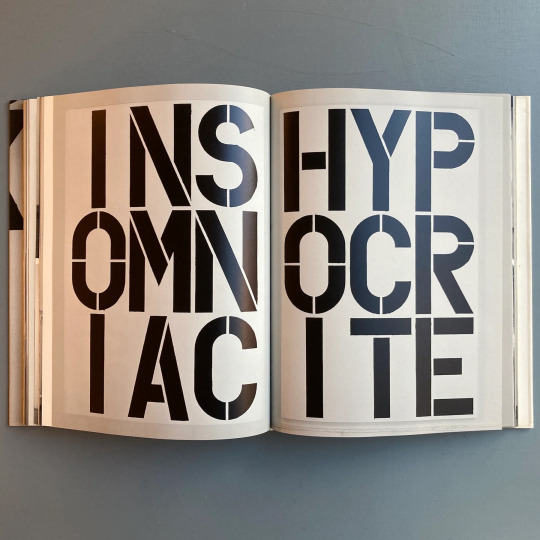

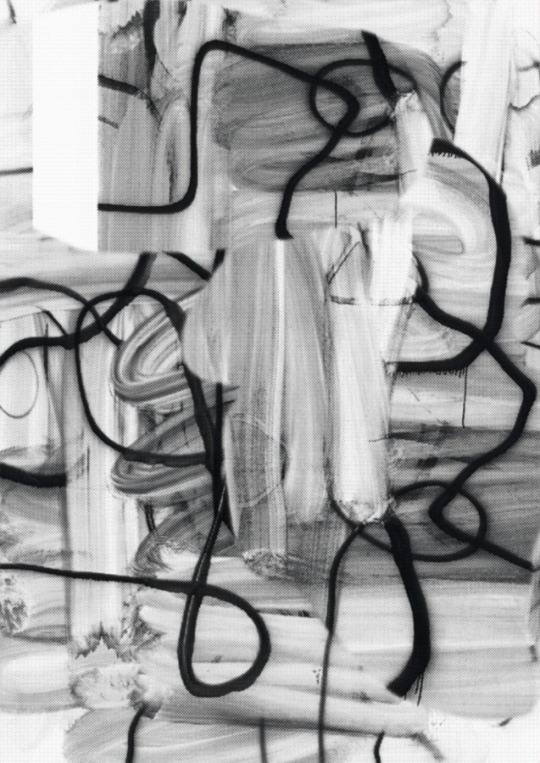

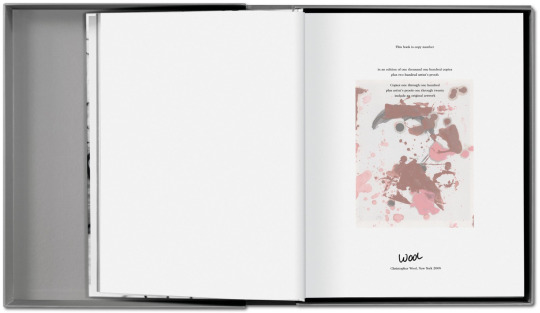

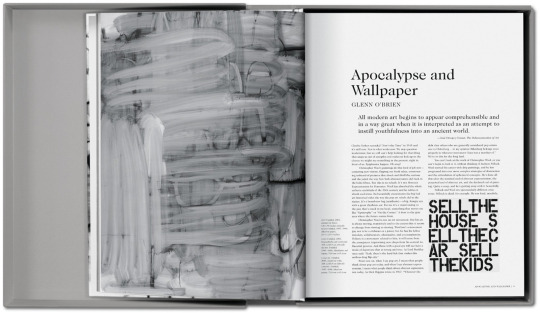

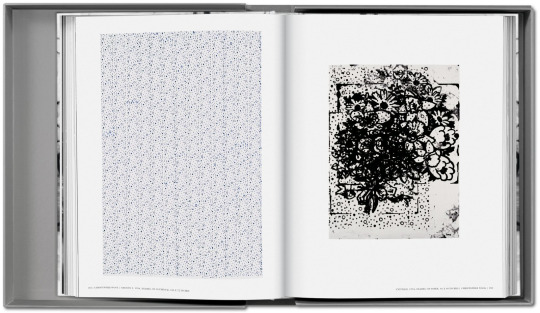

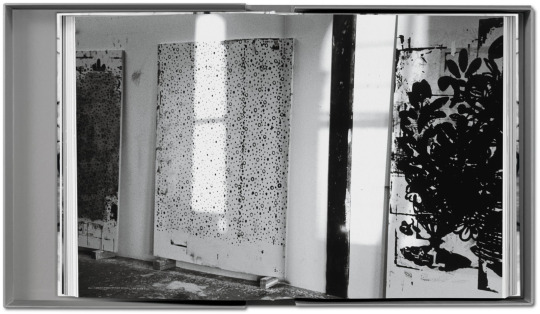

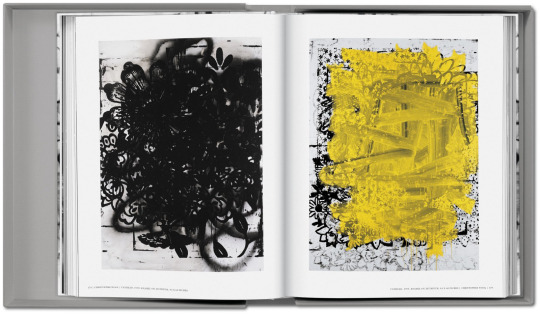

Christopher Wool, Edited by Hans Werner Holzwarth, Texts by Eric Banks, Ann Goldstein, Richard Hell, Jim Lewis, Glenn O'Brien, and Anne Pontégnie, TASCHEN, Köln, 2008, Limited Collector’s Edition of 1,000 copies, each numbered and signed by the artist

#graphic design#typography#art#visual writing#mixed media#catalogue#catalog#cover#christopher wool#hans werner holzwarth#eric banks#ann goldstein#richard hell#jim lewis#glenn o'brien#anne pontégnie#taschen#2000s

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

One final note, with spoilers, on The Story of the Lost Child by Elena Ferrante tr. Ann Goldstein, and its brilliant final chapters.

In the very final moment, the two dolls from their childhood arrive, impossibly, in Lenú’s apartment, in what seems like the best case of dissolving boundaries there is. Lila in that moment has bent time and space to her will. No one knows where she is. In the end, Lila seeks out that complete dissolving, because in that space, she can decide her own reality, to some extent. But still, she sends the dolls.

And how did she get them? I always wondered if perhaps, in that very first scene of the Neapolitan novels, as they’re in the dark basement, if Lila found the dolls after all. If she just wanted to push Lenú to challenge the villain, if she just wanted to ruin their game, if she just wanted both of them for herself. If she went back for them later.

I think that’s why Lenú finds it comforting. It’s not just that it’s proof of Lila still being out there, but proof of something inherent in their complicated friendship. A friendship both adoring and spiteful. A friendship that so often consisted of Lila “hiding” things from Lenú that Lenú simply didn’t or couldn’t see; of Lenú hiding things from Lila and thinking to herself that it’s justified. They both tried to protect the other, in their ways, and Lila is both acknowledging that and admitting that here. She is admitting the pain and pleasure of their relationship, in a way that Lenú recognizes on some deep level.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

**Shots of the Episode**

Ted Lasso (2020)

Season 3, Episode 11: “Mom City” (2023)

Director: Declan Lowney

Cinematographer: Vanessa Whyte

#shots of the episode#ted lasso#ted lasso season 3#ted lasso s3#mom city#declan lowney#vanessa whyte#jason sudeikis#joe kelly#2023#bill lawrence#brendan hunt#brett goldstein#nick mohammed#juno temple#keeley jones#phil dunster#jamie tartt#becky ann baker#coach beard#2023 tv#roy kent#afc richmond#kola bokinni#billy harris#cinematography#apple#apple tv+#tv#streaming

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

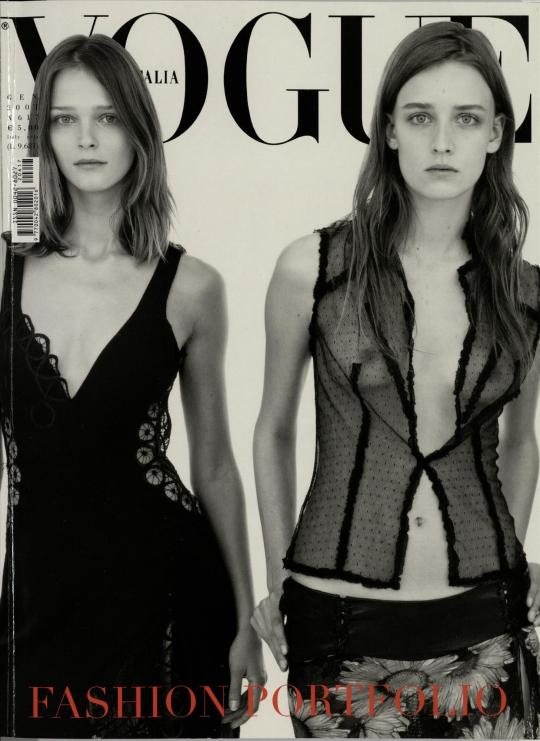

Vogue Italia January 2002

Carmen Kass, Anne-Catherine Lacroix & Donna Mitchell by Steven Meisel

Styled by Lori Goldstein

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

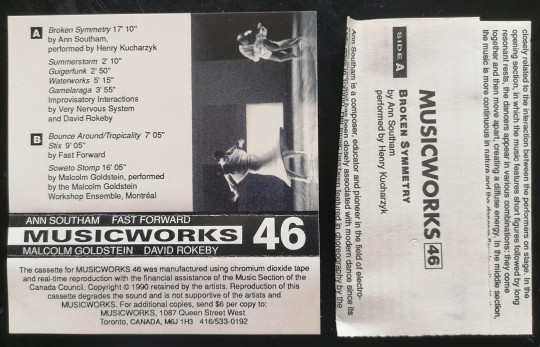

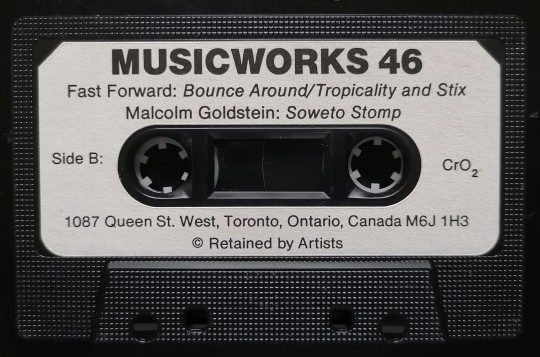

V/A

"Musicworks #46"

(cassette. Musicworks. 1990. rec. 1987-88/90) [CA/US]

youtube

#compilation#1987#canada#usa#contemporary#electronic#avant garde#ann southam#david rokeby#very nervous systems#malcolm goldstein#fast forward#cassette#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes