#this is a balzac novel after all

Text

La peau de chagrin 1980

#nah i just thought these shots of eugene drunkenly playing with his lover's curls while listening to rapähel were cute#la peau de chagrin 1980#you can see why ralph's hair is so wrong for an uber dandy lol#euegene de rastignac#raphael de valentin#yes everyone is a decadent aristo with 'de' particles :P#this is a balzac novel after all

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is not a coincidence that in the last two decades of the 19th century, as the invert case study put gay lives into print for the first time, we begin to see the first novels that, rather than including gay characters within Zola-style social narratives, are instead about homosexuality, or, more accurately, about the condition of being a homosexual. There weren’t very many of these books, and most are long forgotten. But already, as Graham Robb observed in Strangers, his study of homosexuality in the 19th century, the trope of the ‘gay tragic ending’ was in evidence: ‘In twelve European and American novels (1875-1901) in which the main character is depicted, often sympathetically, as an adult homosexual man, six die (disease, unrequited love and three suicides), two are murdered, one goes mad, one is cured by marriage and two end happily (one after six months in prison and emigration to the US).’ As Robb says, it cannot only be that authors felt they had to inflict punishment on their characters, as a way of redeeming their text in the eyes of the censor. The tragic death was a strategy: by showing a doom to which gay men were fated, they were arguing against the society that made it inevitable.

The case study underlies the major tradition of gay writing that developed after 1945 and that persists to the present day, the often melancholic or tragic novels of individual struggle, of childhood and adolescent experience, of attempted repression, of searching, of sexual experiment and release: from Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar to James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, to Edmund White’s A Boy’s Own Story to Annie Proulx’s ‘Brokeback Mountain’ to Garth Greenwell’s What Belongs to You to Édouard Louis’s The End of Eddy to Alice Oseman’s Heartstopper. Those novels that largely or entirely concern themselves with gay male characters – such as Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library, which has no women in it – also have a relationship to the case study, which, especially once it concerns the subject’s adulthood, essentially limits itself to describing his interactions with men of his own kind.

The requirement to lift our sights – to see gay lives as they interact with, to use Zola’s words, family, nation, humanity – is especially pressing if we are dealing with the past, when society was culturally and legally premised on heterosexuality to an extent no longer possible here (though still the case in many non-Western countries). To write about gay men in Britain in the 19th century, for example, should be to write about them as sons, brothers, friends, lovers, husbands, fathers, grandparents, members of a social class, employees, employers, thinkers, readers, politicians, imperialists and so on; as part of the world, not as apart from it. To return to Forster’s definitions, this would be to take gay men out of story and put them into plot; to turn them from ‘flat’ characters, with one dominating trait, into ‘round’ ones. This does not mean that we should minimise sexuality – rather, we would see its significance more clearly, as it disrupts, or perhaps doesn’t, in all areas of life; in so doing, we would see the society more clearly also. The same can be done in novels about the present: to live up to the full ambition of the idea of ‘queering’ – as disruption – we need to see a queer individual in the full spectrum of their relationships with people, places, institutions. To keep our exploration within the bounds of identity is to conspire in our own limitation.

Full article: "Balzac didn't dare: Tom Crewe on the origins of the gay novel" [London Review of Books]

A rather thought-provoking article! The assertion about contemporary gay literature (the whole gay-related media, actually) still being centered on homosexuality itself is very true, and it's something I consider a crucial matter. And, of course, this also makes you raise questions over isolationist movements inside the LGBT+ community.

#tom crewe#literature#lit#gay literature#lgbt literature#history#gay history#lgbt history#gay books#gay fiction#gay#mlm#lgbt#booklr

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Rearranging my bookshelves at the moment in chronological order. One thing I noticed is that after Austen... English literature kinda fizzled out. At least until the early 1890s when a whole pile of writers emerge all at once (Wilde, Yeats, Shaw, Stevenson, Conrad, Doyle, Hardy, H. G. Welles, and more; and almost immediately they're followed by a tidal wave of modernists). Whereas for seventy years, aside from the three big poets you're covering plus Alice In Wonderland, it's just Dickens, Eliot, and the Brontes!

Now, admittedly the 'just' is doing some heavy lifting — but so are those novelists, in carrying Shakespeare's language over a seventy-ish year period! And in terms of variety, they feel like both a less *diverse* ('sprawling 18C three-deckers' describes accurately, if dismissively, most of those novels) and, more controversially, a less *fruitful* crop than the bursting quarter-century from Blake's first illuminated manuscripts to Austen's death.

Now you did discuss the 'cultural studies' aspect of the Victorian era, which was very enlightening — but at the same time, Russian, French, and American literature each undergo what are almost certainly their greatest periods! Which makes sense to me considering the *imaginative* ferment I'd expect to be cause by the political and industrial revolutions of the entire period... like, those three countries didn't reduce to cultural studies!

So, three questions: 1) Who am I missing over that stretch from Austen's death to, let's say, Dorian Gray? 2) Do you think this reading is correct, or am I weighting things wrongly, either being too dismissive of the writers named, or giving too much credit to the writers at either end of the century? 3) What, if you can answer something so broad, was different in France, America and Russia?

(Sorry to set you a three-part essay question on a Wednesday night lmao, really I'm just fishing for any interesting thoughts you might have)

If I were to dispute your claim, I would do so in two ways: 1. I'd say that Dickens is so enormous, so much the iconic and canonical English novelist, the one who stands next to Shakespeare, that he carries the whole period; and 2. I'd say (and have already said in The Invisible College) that the Victorian Sage writers like Carlyle, Ruskin, and Arnold have the weight and intensity of the prior Romantic poets and subsequent modernists.

If someone else were to dispute your claim, someone else might say that there are a lot of great novelists in the mid-Victorian period, like Trollope, Thackeray, Mrs. Gaskell, and Wilkie Collins. Someone else might say this, but I could never get interested in those writers, and I doubt anyone thinks they're the equal of Balzac, Melville, or Tolstoy—or of Dickens. On the other hand, we now take the Brontës far more seriously than people once did—I would put them essentially on the same level as Austen and Dickens—so fashions in these things are always changing.

So I essentially agree with you that, except for the writers you name, especially Dickens and Eliot, it's a fairly flat period. I suspect the reasons are the ones the modernists would have offered, despite their sometimes exaggerated animus against the Victorians: the sentimentalism, the censoriousness, the middle-class piety, the imperial self-regard, the padded serials, and all the rest of it.

I've quoted on here before Seamus Deane's slightly offensive view of the matter in his Celtic Revivals, coming from Marxist postcolonial theory (and as I've also said before, this is particularly unfair to George Eliot, who, I must emphasize, translated Spinoza):

It is, I believe, easier to understand Joyce’s achievement in this respect by looking to the Continental tradition of the novel. There the theme of intellectual vocation was much more deeply rooted and was treated with a subtlety quite foreign to the evangelical, female puritan spirit which so dominated the sentimental English novel. Perhaps Middlemarch more than any other single work shows how the innate provincialism of the English novel deprived it of a consciousness of itself as a part of a greater European culture. This is something conspicuously present in the French and, even more, in the Russian novel of the nineteenth century. One could not imagine Crime and Punishment or Le Rouge et le Noir without the idea of Europe, especially Christian Europe, as a living force in them, in their traditions, and in the minds of their creators. But Emma and Great Expectations and Middlemarch survive happily, and more modestly, apart from that idea. Not until an American, Henry James, arrived on the scene was the novel in English Europeanized, and the Irishman Joyce countered this achievement by anglicizing the European novel.

So that "puritan" and "provincial" spirit explains the disparity between the English on the one hand and the Russians and French on the other, who were simply writing in different social circumstances for an audience presumed to contain fewer young ladies in need of moral protection. One might add the English empirical bias against big ideas, which authors as different as Blake and Eliot would so strongly protest.

In Love and Death in the American Novel, Leslie Fiedler says the European novelists held together an audience that consisted of common readers, mostly female, on the one hand, and highbrow intellectuals, mostly male, on the other. The Anglo novelist, by contrast, somehow let this audience fragment early on and had to address either one set of readers or the other.

The American case is particularly instructive: Hawthorne and Melville were neglected in their time, relegated to the margin by popular novels written in "the evangelical, female puritan spirit," of which Uncle Tom's Cabin is the most famous—but we just don't read these books! We read The Scarlet Letter and Moby-Dick instead of The Lamplighter or The Wide, Wide World. It's as if the English Victorian canon had been reduced to Sartor Resartus and Wuthering Heights. This causes the historicist critic to despair, and obviously a certain type of feminist critic too, who especially resents Hawthorne's line about "the damned mob of scribbling women," but what we can we do? We're interested in what we're interested in. And as I said in one of the IC episodes, it's not as if the great female writers of the 20th century wanted to follow in Stowe's footsteps either, since the puritan and provincial spirit was a much a prison for female authors in the 19th century as it was their place (their only permissible place) of articulation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

books i read in feb 2024

[these are all short + casual reviews - feel free to ask about individual ones if u want my full thoughts or ask for my goodreads!!]

great pace for february! i'm in the complete opposite of a reading slump where i'm loving everything that i read, which is so enjoyable 🤗

mammoths at the gates - nghi vo ★★★★★ (fantasy novella)

a tender, thoughtful exploration of grief with great clarity of vision. i've loved every single instalment in this series!

heartstopper vol. 5 - alice oseman ★★★★★ (YA romance graphic novel)

lovely reread! i definitely enjoyed the volume over reading them online. i love how cute and charming and fun the whole comic is while still tackling serious topics with considerable weight

[REREAD] the song of achilles - madeline miller ★★★★★ (mythology retelling)

the audiobook makes such a tremendous difference in elevating this book! i gave it 3* as a paper read years ago and would probably still stand by that, but frazer douglas is working miracles

bride - ali hazelwood ★★★★☆ (contemporary romantasy)

super fun if you're into basic vampire-werewolf type of shit, and i am extremely into basic vampire-werewolf type of shit, so!

last night at the telegraph club - malinda lo ★★★★☆ (historical romance)

sometimes a book just tickles your personal fancy, and i think this is one of those. the writing was bold at parts and tastefully understated in others. it's delightful in its immigrant chinese-ness and touching in its queerness

seven ways we lie - riley redgate ★★★★☆ (YA contemporary)

solid look into the types of isolation we experience as teenagers in high school. it's pitched as gimmicky but easily transcends that into something surprisingly thoughtful

patron saints of nothing - randy ribay ★★★★☆ (YA contemporary)

idk if this is a "good" book about the sociopolitical issue at its heart, but it tackles with a lot of grace a very teenage reaction to a sense of powerlessness. it's also a hilariously cathartic book about a guy getting drastically humbled on every other page

greywaren - maggie stiefvater ★★★★☆ (fantasy)

i didn't reread the series before this finale so it's hard to judge it fairly, but it felt like a clumsy landing. i liked parts of it, but i found other parts of it totally forgettable or overwrought to no effect

balzac and the little chinese seamstress - dai sijie ★★★★☆ (historical)

reads almost pastoral, with its small scale and everyday concerns. a neat glimpse into a life under the cultural revolution, but nothing particularly unique or stirring

[DNF] a magic steeped in poison - judy i. lin ★★★☆☆ (YA fantasy)

giving up on this book after three tries. it's a completely standard YA fantasy and i think people who have an appetite for stories like this would enjoy it, but it's not for me

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who are your favorite novelists and why?

I love Stendhal above all because only in him are individual moral tension, historical tension, life force a single thing, a linear novelistic tension. I love Pushkin because he is clarity, irony, and seriousness. I love Hemingway because he is matter-of-fact, understated, will to happiness, sadness. I love Stevenson because he seems to fly. I love Chekhov because he doesn’t go farther than where he’s going. I love Conrad because he navigates the abyss and doesn’t sink into it. I love Tolstoy because at times I seem to be about to understand how he does it and then I don’t. I love Manzoni because until a little while ago I hated him. I love Chesterton because he wanted to be the Catholic Voltaire and I wanted to be the Communist Chesterton. I love Flaubert because after him it’s unthinkable to do what he did. I love the Poe of “The Gold Bug.” I love the Twain of Huckleberry Finn. I love the Kipling of The Jungle Books. I love Nievo because I’ve reread him many times with as much pleasure as the first time. I love Jane Austen because I never read her but I’m glad she exists. I love Gogol because he distorts with clarity, meanness, and moderation. I love Dostoyevsky because he distorts with consistency, fury, and lack of moderation. I love Balzac because he’s a visionary. I love Kafka because he’s a realist. I love Maupassant because he’s superficial. I love Mansfield because she’s intelligent. I love Fitzgerald because he’s unsatisfied. I love Radiguet because we’ll never be young again. I love Svevo because we have to grow old. I love . . .

— Italo Calvino, from “Answers to Nine Questions on the Novel” in “The Written World and the Unwritten World: Essays. Translated by Ann Goldstein. (Mariner Books Classics, January 17, 2023)

#Italo Calvino#authors#novels#Stendhal#Pushkin#chekhov#Conrad#tolstoy#manzoni#voltaire#flaubert#mark twain#Edgar Allan Poe#rudyard kipling#Jane Austen#Dostoyevsky#balzac#kafka#maupassant#Katherine Mansfield#radiguet

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi claritasssss ! i was wondering. who would you say are your biggest inspirations when it comes to writing? if you have no one specific you can just say any writer you enjoy : - )

Oh, this is gonna sound like a mess, but hear me out. Let's start off with the animanga content ones.

日日日/Akira is a huge inspiration when it comes to constructing complex characters, and when it comes to building upon the framework of classics. He's amazing at using them as clear inspiration without it feeling derivative and giving them a twist in his personal style. My mind is also blown by the inobtrusive way he includes metafiction into his story! He sucks as a person, and he's part of the money-grabbing-gacha machine which influences him and limits what he can do so I'm a bit sad that we can't see where ES would go were he given the reins, but not to the point where I'd read his other work. I don't wanna peek inside his mind.

On the other side of writing, Nisioisin's writing of JJBA: Over heaven greatly influenced my locution and how i articulate my thoughts - I really admire how he wields the rhythm of his sentences, as well as the way he begins and ends chapters. The novel majorly influenced me without doubt lol!

Jun Mochizuki is not a prose writer, but I consider her a master in crafting stories. When it comes to manga, I have to say Takako Shimura's Wagamama Chie-chan left a deep impression in me despite being pretty repulsive, and I think Shimura is kind of gross in general after a skim of what else she'd written LOL but the use of estrangement and unreliable narration in Chie-chan is super solid.

Incredibly due mention to Ikuhara. He's not a prose writer either but his usage of allegory and the ability to delve deep into traumatic subjects frankly but with grace are something I greatly admire.

Now, onto classics. You probably already figured out that I'm really marked by Chuuya Nakahara's work for better or for worse - I also like Rimbaud who was an influence of Nakahara's. I have other poems I like, but no authors I read consistently or felt particularly influenced by. As for classic novelists, Dostoevsky is a necessary mention, as well as - no matter how I loathe to admit it! - de Balzac. Not particularly for their writing styles, for I'm no bootlicker to realism, but I admire the way they delved into the human mind and everyday life respectively, devoting their lives to painting the image of a common man so throughly trampled by high literature! Ovid. There are a few classic Chinese poets I admire a lot for their graceful yet featherlight imagery in contrast to often somber topics, but my little book of foreign classics is not here so I can't quite recall the specific names. Akutagawa's short stories also.

Now, onto more modern writers. N. K. Jemisin is the scifi/fantasy author I admire the most, for I don't like either if they can't be connected to contemporary issues and stories, and she does an amazing job of it in her novels despite me having a few qualms with her writing style (mostly with her choosing to use a glossary of fantasy terms rather than explaining them in the text itself in the broken earth, it's difficult to follow but again that's partly on me). Oyinkan Braithwaite left a deep impression on me with her debut novel, and I'm excited to read more from her. I'm still early delving into R. F. Kuang's work (midway thru Babel and beginning Yellowface) but I really, really like her mastery of language and the sentences she builds. Min Jin Lee is super inspiring in how she switches between countless character perspectives with incredible fluidity and without the narration feeling strained at any point!

I shan't dive into all theorists I like because I'm not sure I can count them all on the fingers of one hand, but I wanna bring up Shklovsky's Art as device for opening my eyes to a lot of inner workings of literature. Peace and Love!

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am still at the beginning of their love story. This story will be followed by two sequels. Your Strawberry

A visit from home

He had been living in this great city pulsating with life for a few weeks and he was still fascinated to be living in a place that had inspired novels. He walked in the footsteps of Gustave Flaubert, Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac. He hardly missed his hometown, but he did miss the wife he had left behind there. It had taken all his courage to call her on the first day. But since then they had talked on the phone every day. He would have loved to walk the streets of the novels with her and discover this enchanting city together. He longed for a reunion, but at the moment this seemed far away.

Day after day he learned new things, but he had to admit that he was no longer the best. He had to acquire things through a lot of work. After another exhausting week, he arrived at his flat exhausted on Friday afternoon. But as he climbed the last flight of stairs to his garret, a surprise awaited him. The woman he longed for so much was standing in front of his flat door, waiting for him. He was so surprised that he stopped and just stared at her. Embarrassed, she looked towards him and brushed a strand of hair behind her ear. Then she gave him a smile that released him from his stupor.

Beaming, he climbed the last steps and embraced her. Moved, he whispered: "It really is you. There's nothing I've wanted more than to finally see you again." He heard her laugh, smelled her scent and felt her warmth. His tiredness was blown away. He could hardly believe his happiness that he could finally hold the woman he loved so much in his arms again.

He proudly showed her his small flat. Then they sat down at the small table with the two chairs and the view over the city. He made them espresso and they began to talk, just as they did every day on the phone. Now, however, they could see in each other's eyes how he reacted and after a short while their hands found each other and held each other. At some point their gaze went out the window and lingered over the city. Smiling, she said, "You have raved about this city so often that I had to come here to see it through your eyes. Will you show me all that you have already discovered?"

He guessed that this was not the real reason for her visit, yet he gladly acceded to her request and as he had imagined, he roamed with her through the streets of the novels they both loved. But unfortunately the city did not show itself from its best side and it began to rain. Completely soaked, they reached his flat where they faced each other soaking wet and started laughing at the same time. "This is not how I imagined the end of our exploration tour," he admitted. "We need to get out of these wet clothes," she said and he saw that she was already shivering slightly. "Go into the bathroom and take a shower," he suggested. Startled, she looked at him. "You're cold," he explained. He went to the cupboard and took out a large towel for her. "What should I wear after this?" she asked, a little embarrassed. "There's a bathrobe hanging in the bathroom. You can put it on," he explained. "And you?" "I'm not cold. I'll change when you're in the bathroom." He looked at her, pressed the towel into her hand and said, "Go." As the door slammed shut behind her, he murmured, "And lock the door behind you so I can't follow."

Then he felt that he himself was all wet. Automatically, he went back to the cupboard, took another towel and gathered dry clothes. Indecisively, he looked at the bathroom door and thought of the woman undressing and showering behind it. To distract himself, he tore the wet clothes off his body, dried himself and put on dry clothes. After wringing out his wet clothes, he put them on the radiator to dry, sat back on the sofa and stared at the bathrooms door.

After a while, the door opened again and she actually appeared in his bathrobe. His breath caught in his throat. She looked adorable looking at him with her shy smile. "I put my wet clothes on the radiator to dry," she said. He nodded and continued to look at her. She came to him slowly and asked, "May I sit down?" "Of course," he replied, tapping the seat next to his. When she had sat down, she turned to face him so that she could look him in the eye.

"I should finally tell you why I came today," she began. She saw curiosity flare in his eyes. "I have something to tell you that I can't tell you over the phone," she continued. Then she looked to the side and he sensed that she was having a hard time revealing to him the reason for her visit. He reached for the collar of the bathrobe and managed to get her to look at him again. "What do you have to tell me?" he asked expectantly. "You've told me so many times, but I've never said it back." She saw that he understood and an expectant gleam came into his eyes. Patiently he waited for her to continue. She took a deep breath and closed her eyes for a brief moment. When she opened them again, she said with a smile on her lips, "I love you too." Moved, he pulled her to him and kissed her.

Hellooo sweet 🍓! ❤️

No but you just kill me! Brigitte going there “just” (even if I suspect there will be more to it 😏) to tell him back that she loves him too. Oh my heart, just so pure and soft 🤧😍

The bathroom moment tho... just imagine how much Emmanuel had to fight with himself not to just bang the door and enter 🤭😂

Thank you so much, Strawberry! ❤️❤️❤️

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ariel-seagull-wings asked me this on @askimemnupodcast but I want to answer more basic questions there to rework into scripts, so I will answer this here. I will include this ask into a larger episode of the podcast called “What Would They Read?” but it would be an episode that would require a lot of research.

This is an excellent question! Actually we learn that gradually Mademoiselle starts to let Nihal read novels, and we are told that after Mademoiselle leaves Nihal is so sad that she is unable to read, but if I am not forgetting something we do not learn what she reads.

We are told that Bihter reads stories in Turkish in magazines and newspapers, which makes her distinct from Nihal and Behlül who are probably reading their novels in French.

The two characters whose reading habits we know more of are Mademoiselle de Courton and Behlül. Mademoiselle is a fan of Alexander Dumas (it is not clarified but I think it is the father) and reads the French newspaper Figaro. Behlül reads the novelist Paul Bourget because “he understands female psychology”.

What would Nihal read? First of all I think Nihal would be likely to read French literature since she knows French. It is unlikely that she would have access to the European literatures of other languages, and I don’t see her as being super interested in Turkish literature of her time.

I am a bit out of my depth here because I don’t really know what young Francophone girls were reading in turn of the century. Officially Nihal should be reading “clean” literature too since we are told that Mademoiselle checks what she reads. But if she were to read secretively, maybe picking up books from her father’s or Behlül’s libraries, maybe she would read the great authors we all know of like Balzac or Hugo? And if she were to read Madame Bovary she would understand what’s going on with Bihter much more quickly.

One French novel all girls in Turkish literature of the time read is Paul et Virginie, but I think it is a bit too romantic for Nihal’s taste. Nihal is a Romantic certainly, but she is not a romantic, you know?

If she were to read French translations of other European literatures, I can for some reason see her being fond of E. T. A. Hoffman.

Any other ideas?

@artemideaddams @ariel-seagull-wings @princesssarisa @struttingstreets

@la-pheacienne I know you haven’t read the book but you are a Francophone so…

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

weird question i know, but in one of your ask you mentionned Hamlet and while i don't go as far as thinking you liked the play just because you talked about it, is there any classical/literary works you enjoyed or particularly liked ?

I read Hamlet in school (I believe it's standard for students to read some Shakespeare in Anglophone or Anglo-controlled regions?), but I wouldn't call it a personal favorite. There is an obvious joke to it, that the play often labeled the greatest is the English language is in fact about Danes.

There's quite a few literary works I enjoy, and many of the fictional characters that have resonated with me the most come not from video games but from novels and plays. At university I specialized in 19th and early 20th century French and British literature, and that in combination with elements of Louisiana's own literary tradition forms the core of my interest in that area although not the entirety of it. As a child my favorite conte was always Perrault's "Cendrillon," and I like adaptations of that story that preserve its French character. De Laclos's Les Liaisons dangereuses was introduced to me via adaptation, and especially after reading the novel for myself I can say that it's produced one of my favorite villains.

More in my usual wheelhouse, of course I read all the big 19th century French novelists; Balzac may be my favorite in general - I love his whole comédie humaine concept of interconnected stories - although I did actually spend some time in the fandom for Les Misérables about a decade ago in my early days on Tumblr. For the Irish and British I gravitate more toward the modernists: Joyce and Yeats and Woolf (whose work inspired one of the few 21st century novels I've really liked, Michael Cunningham's The Hours) and Forster.

Over in Louisiana, Chopin is most known for The Awakening although I enjoy some of her short stories about the Louisianais as well. Faulkner is famously inscrutable, but as you can probably tell from my own writing I can respect the ability to string together very long sentences. His Absalom, Absalom! is a particular favorite as it prominently features New Orleans, and much of its plot hinges on the - as it's sometimes called - transnational character of the city. Of course I can't forget playwright Tennessee Williams, who (perhaps unknowingly?) eulogized French Louisiana in the mid-20th century with A Streetcar Named Desire, possibly the best-known literary work set in this city that doesn't involve vampires. I'm not terribly fond of Anne Rice's writing, but growing up with the knowledge that she'd mythologized my culture as hedonistic, bloodsucking undead was admittedly kind of fun in a way. Tourists who come here for their occult fascinations are absurdly easy to impress.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louveciennes resembles the village where Madame Bovary lived and died. It is old, untouched and unchanged by modern life. It is built on a hill overlooking the Seine. On clear nights one can see Paris. It has an old church dominating a group of small houses, cobblestone streets, and several large properties, manor houses, and a castle on the outskirts of the village. One of the properties belonged to Madame du Barry. During the revolution her lover was guillotined and his head thrown over the ivy-covered wall into her garden. This is now the property of Coty.

There is a forest all around in which the Kings of France once hunted. There is a very fat and very old miser who owns most of the property of Louveciennes. He is one of Balzac's misers. He questions every expense, every repair, and always ends by letting his houses deteriorate with rust, rain, weeds, leaks, and cold.

Behind the windows of the village houses old women sit watching people passing by. The street runs down unevenly towards the Seine. By the Seine there is a tavern and a restaurant. On Sundays people come from Paris and have lunch and take the rowboats down the Seine as Maupassant loved to do.

The dogs bark at night. The garden smells of honeysuckle in the summer, of wet leaves in the winter. One hears the whistle of the small train from and to Paris. It is a train which looks ancient, as if it were still carrying the personages of Proust's novels to dine in the country.

My house is two hundred years old. It has walls a yard thick, a big garden, a very large green iron gate for cars, flanked by a small green gate for people. The big garden is in the back of the house. In the front there is a gravel driveway, and a pool which is now filled with dirt and planted with ivy. The fountain emerges like the headstone of a tomb. The bell people pull sounds like a giant cowbell. It shakes and echoes a long time after it has been pulled. When it rings, the Spanish maid, Emilia, swings open the large gate and the cars drive up the gravel path, making a crackling sound.

Behind the house lies a vast wild tangled garden. I never liked formal gardens.

With the first crushing of the gravel under wheels comes the barking of the police dog, Banquo, and the carillon of the church bells.

Every room is painted a different color: lacquer red, pale turquoise, peach color, green and grey.

-Anais Nin, 1931

0 notes

Text

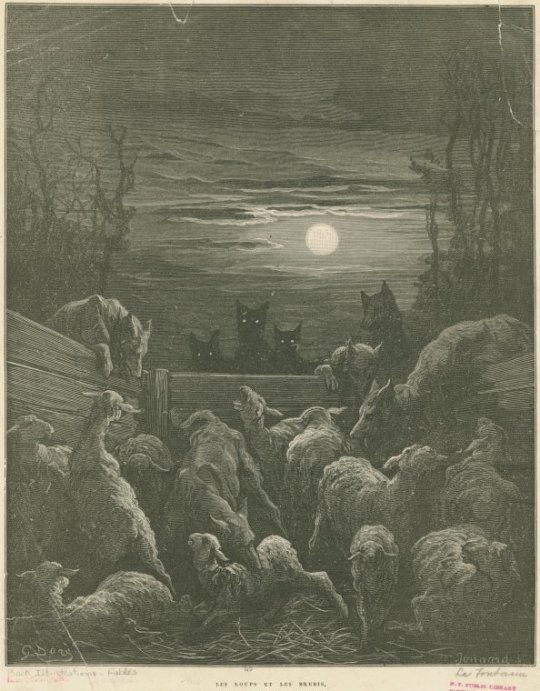

Madame Putiphar Groupread. Book Two, Chapter XXXI

“We must howl with the wolves, he who bleats among them shall be their prey!”

(tr. here by @sainteverge )

Gustave Doré's Les loups et les brebis.

Sit yourself with a nice cup/glass of something and let’s ponder urban/rural, intra/extra european tensions in the 19th c european novel together. nerdface emoji.

(I love you Borel but this chapter has tested my patience. Why do you make the blorboes move at a glaciar pace in times of crisis)

After Deborah’s announcement and Patrick’s declaration of ideal paternity and family life, the couple dines together. Patrick asks Deborah if she likes Paris specifically before letting her know that they must LEAVE the city FAST. That gives Borel the chance to explore through Deborah yet another central theme of the Romantic novel, or the 19th c novel as a whole, Rural vs Urban life tensions. Borel as always, adds his own personal twist to it. Taking into account how essentialist 19th c French-surely not exclusively- literature is, how Romantic movements are about going back to some kind of National essence, how you cannot leaf through one of these books without reading about so called spanish/italian personality traits, occasionally reaching ad absurdum levels like in Dumas when he has Dantès claim that southern europeans are more vulnerable to poison than northern europeans, Balzac and his ambitious meridionals (in his defense, he at least IS a meridional himself), his stabby-because-catholic corsicans, and don’t get me started on Gautier’s Voyage en Espagne. Positive or negative, there is in this literary word, no escaping regional stereotyping.

What Borel does when addressing the question, does Deborah miss Ireland, she states that she doesn’t, not Ireland specifically. What she misses is the countryside, what she loathes is city life. And, she affirms, she would loathe it as much in Dublin as in Paris. Modern Urban life is to her a sickness that seems to afflict all of Europe equally. This definitely stands out from other portrayals of Paris as a modern Babylon we’ve seen from other authors... Balzac would never. Paris is hell, but to him it is also Paris. as Diderot would say, in a fit of excessive nationalistic intoxication Paris is the brain of France, and France is the Brain of the World. yes. that was something he said unironically) But Borel does not care about what makes Paris specific here... Paris is part of something bigger, and not actually something good. He once again seems to anticipate much later philosophical ideas like Marc Augé’s non-places. Read this and tell me it doesn’t make you think of our post modern present, with our increasingly minuscule flats, the impossibility of looking out and not seeing more flats in some of the biggest metropolis in the world, etc:

“Living in cities is narrowing; these boxes, these cages where as prisoners we wither away, compress and cinch the soul like a corset: our spirit confines itself to two ceilings and four walls; our gaze, which cannot break through, hits the surface and falls back on us; we take the habit of indulging ourselves, of being satisfied with ourselves, we diminish, we shrivel away. The perpetual sight of men’s work renders us petty and bourgeois like them: we forget the grand spectacles of nature, we forget the universe, we forget humanity, we forget everything, aside from ourselves, and whatever tastes we seek to quench: all creation comes down to a few pieces of furniture, a few chairs, a few tables, a few beds, a few pieces of fabric or silk, which we grow enamoured with, which we’re attached to like the oyster to its stone, over which we vegetate and crawl like lichen”

(translation by sainteverge)

I’d like to link here an excerpt of Champavert: The Werewolf as well. This earlier text seeks to be specifically Parisian, and more encompassing than Debby’s experience. (noted passages in a similar vein: Balzac's Galleries of the Palais-Royale descriptionin Lost Illusions (the city-as-spectacle, everything and everyone for sale) and his snapshots of social inequality in Père Goriot)

“Le monde, c’est un théâtre: des affiches à grosses lettres, à titres emphatiques, hameçonnent la foule qui se lève aussitôt, se lave, peigne ses favoris, met son jabot et son habit dominical, fait ses frisures, endosse sa robe d’indienne, et, parapluie à la main, la voilà qui part; leste, joyeuse, désireuse, elle arrive, elle paie, car la foule paie toujours, chacun se loge à sa guise, ou plutôt suivant le cens qu’il a payé, dans le vaste amphithéâtre, l’aristocratie se verrouille dans ses cabanons grillés, la canaille reste à la merci. La toile est levée, les oreilles sont ouvertes et les cous tendus, la foule écoute, car la foule écoute toujours; l’illusion pour elle est complète, c’est de la réalité; elle est identifiée, elle rit, elle pleure, elle prend en haine, en amour, hurle, siffle, applaudit; en vain, quelquefois, sent-elle qu’on l’abuse et s’arme-t-elle de sa lorgnette, elle est myope, rien ne peut détruire son illusion et sa foi qu’exploite si galamment les comédiens”

Both of these passages share a grim diagnosis. Capitalist Modernity seems to be here a degenerative illness. Deborah’s focuses more on the domestic, most of her life means staying locked in, completely lonely, but she has observed how the city tends to isolate, to make people focus only on their selves and their whims, which can only be satisfied by buying furniture, clothes, a thirst for possessions that transforms Humans into Oysters....

This to me is the highlight of the chapter.

After this speech our friends agree they must flee, and quick. Patrick and Deborah are ready to be open to each other. They tell each other what the reader already knows, they are now both equally aware of their danger, and of the wrongs they have both endured at the hands of their aristocratic tormentors.

Noteworthy word choice: Patrick compares himself at the hands of Putiphar to a virtuous maiden (we have joked in the groupchat about Debby and Patrick being lesbians before... Butch Lesbian Patrick confirmed)

Another thing i found startlingly contemporary sounding, in our days of lawfare and soft coups, Patrick, talkig of how Putiphar can use his theft and murder accusatio to give her illegal persecution a virtuous veneer: “she’ll be able, not that she cares about it, to mask her revenge behind an honest mask (...)”(tr, by cam)

Theres an absurdly ooc Deborah moment when she weeps and declares herself a burden. His beauty could have been the key to a brilliant social assent. Patrick corrects her, slightly offended because he is not about that #arriviste #boytoy life (Debby already knows that!???!) But Debby is only saying all of this because she fears this Fredegund’s retaliation........

Since God is apparently devoid of his divine wrath, and the powerful villains go unpunished, they must leave Paris in search of a new Promissed Land (slightly Candide-ish, right?) where if men are not less evil, (Patrick moves away from Rousseau... at least for a second) at the very least they can hope for a less asymmetrical distribution of power. Patrick has his naif hopes set on one of those ignored places European society calls savage, which he assumes will be more fit to give them “their share of sun, land and fraternity” (this is also a common theme in french novels of the day... Patrick at least still hopes to find Fraternity in these unspecified so called third world lands, instead of lording over the savages like Thénarider or Goriot era Vautrin...-Splendeurs era Vautrin hopes for an American Forest to die alone in after having eaten his own tongue. Progress. Growth.)

The only way of living in the European City is howling with the wolves, and since they’re not willing to do so, because they are lambs, they must leave. And Fast. So first to Marseille, Geneva or Livorne, and then to whatever earthly “virgin” rousseau/bougainville paradise they choose to set their paths to.

So Patrick (finally!!! sorry) leaves to buy some tickets in the first available carriage, Deborah will pack their things to avoid boredom/stress. Patrick wants a kiss, she refuses bc the farewell will then feel too final (...) Patrick claims that iron cannot harm a limb that has been kissed by a woman’s lips, so she passionately kisses him over his heart... but as soon as he sets foot on the streets Deborah hears him cry out for help. He is taken away by the kings men (illegally, in the night, shielded by the darkness) Patrick warns her not to come (she has to think of their baby) and says farewell forever. She throws out a flaming curtain for visibility. she sees as she descends, how Patrick is taken away in a palace carriage. She faints. Is taken away by Palace guardsmen herself. Book Two is over. Lasciate ogni speranza?

{ @sainteverge @counterwiddershins }

#madame putiphar#long post#text post#did not revise this as much as i usually do. hope it's not very: cohesion? I don't know her!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deevyfiction - Chapter 18 - Teaching The Tutor A Lesson quirky thumb read-p2

Brilliantfiction She Becomes Glamorous After The Engagement Annulment read - Chapter 18 - Teaching The Tutor A Lesson mixed sock read-p2

Novel-She Becomes Glamorous After The Engagement Annulment-She Becomes Glamorous After The Engagement Annulment

Chapter 18 - Teaching The Tutor A Lesson tested aback

Even though Cherry thought about being with her daddy, he needed to deal with the vicious teacher now. It had been just as how Mommy would also blindfold her and let her know to number sheep whenever she fought others whenever they had been offshore.

Pete had been a hard to clean child and try to journeyed against him. He often produced him so upset that he or she almost want to offer him a good thrashing. Despite that, he persisted to consider that this was really a period that most common young children experienced.

It was subsequently all his fault.

Cherry stretched out her very little forearms and hugged her fine father. "Everything is going to be fine when you can understand your problems and switch over the new leaf, Daddy!"

Her conversation was very in keeping with what an exemplary teacher would say.

Nonetheless, even he himself was mad, let alone Justin who obtained always enjoyed and doted on Pete. It turned out just that his method of expressing it wasn't quite proper.

The forthcoming landscape was too bloody and unsuitable for young children.

Mommy's so smooth and gentle.

She Becomes Glamorous After The Engagement Annulment

Cherry was overwhelmed.

She disliked having to do research probably the most! Support, Pete!

The Bramleighs of Bishop's Folly

The tutor was shocked by his immediate wrath. Justin was usually very well-mannered directly to them, which produced her overlook how domineering anyone Justin really was.

Wouldn't his id to be a child be uncovered if she were to bathe him?

Which was, until eventually that occurrence past week…

Justin was consumed aback. He appeared lower suddenly to see his boy looking up at him trustingly. His little, childish speech created what he was quoted saying upcoming sound particularly heartbreaking: "Am I really very mindless and dull? Have Mommy reduce the standard of Daddy's genes?"

Which had been, till that accident last week…

the substitute bride is adored by the clumsy margrave

Her conversation was very in keeping with what an exemplary teacher would say.

The trainer was consumed aback.

At the view of how afraid his son searched, Justin didn't afford the coach a way to reveal any longer. He bought, "Bring her out, Lawrence!"

Honore de Balzac, His Life and Writings

Justin sighed. Then, he was quoted saying severely, "We won't indulge any more instructors. I'll personally educate you on later on."

Granny asserted that it had been because the child didn't have got a mom and therefore, had no sense of stability. They mustn't have him, a developed male, taking care of him any more, so she got organized for babysitters, friends and family medical professionals, and trainers for him.

Was this really that little dimwit who didn't communicate?!

It was all his fault.

In the doorstep, the tutor's legs journeyed limp the prompt she noticed Justin's murderous atmosphere and anger. She stated fearfully, "End spouting nonsense, Pete—"

Cherry hid behind Justin and hugged his lower body. She caught up out her tongue for the tutor and mentioned, "Remember to don't reach me once again. I'm sorry!"

In the view of methods afraid his boy appeared, Justin didn't supply the tutor to be able to make clear nowadays. He required, "Take her out, Lawrence!"

Justin's anger washed out a little and then he reported, "Give her an additional half a year's wages."

Was this really that little dimwit who didn't communicate?!

The gentle lips pressed against his brow, creating Pete to lock up. However while doing so, a feeling of anticipations also arose in him.

Within the talk about, Lawrence's go lowered even further. He resolved, "They reprimanded him simply by making him endure, reaching his palms, and reprimanding him. Also, they didn't train him really. They didn't dare to perform any sort of actual misuse more serious than that since they were also scared that someone would find out what was happening."

Her eye shone after she spoke.

The instructor was astonished by his sudden wrath. Justin was usually very well-mannered in their mind, which produced her ignore how domineering anyone Justin really was.

0 notes

Note

I've read the Baffler review, the competing LARB reviews, and the Nation interview, and even after all that, I still barely understand what Anna Kornbluh means by "immediacy." From your previous answer, I know you haven't read the book, but can you help us morons understand what she means? You have such a good way of explaining art and ideas (not that art can be "explained") that open up possibilities of thought for the budding belle-lettrist. (I should probably just read it myself...)

Thank you! I think she means that in a host of domains from communications technology to economic transactions to artistic styles to modes of philosophy there were more barriers or relays a thought had to cross on its way to materialization in the world. This allowed thought a greater purchase, in the form of critical distance, upon what the world really is.

Here's a thought: "I would like to make an economic transaction." You once had to go to bank and talk to someone to withdraw cash; then you had to go to a machine to get cash, and now you don't need cash at all but can just tap your card or use your phone to pay for something. In terms of communication, your feed is constantly refreshing on your screen as you're in instant contact with people all around the world. (How would you, specifically, have asked me, specifically, a question like this 30 years ago?) In the world of art, we no longer value novels, for example, that are complex verbal artifacts densely recording a complete fictional heterocosm, but instead we have speed-written records of the author's personal life. Not to mention streaming TV directly reflecting present conditions as we binge-watch them without critical reflection, etc.

As a Marxist, she's probably interested in the way these developments are an intensified form of ideology qua false consciousness, concealing from us in the blur of the world's increasing speed the material economic and political facts subtending these trends: the labor exploited, the forests cleared, the minerals mined in hellish conditions to bring the high and low bourgeoisie of the imperial core its immediate pleasures. When thought was slower and more "mediated" through real experiences—when we held cash in our hand, when we had to sit through the complexities of a Balzac or even a Pynchon novel if we wanted to be entertained—then even this cosseted bourgeoisie found it harder to deny, harder to avoid comprehending and criticizing, the blood and fire the world of capital is actually made of.

That's the best spin I can put on it. I didn't read the whole book, so I'm making assumptions about where she's coming from theoretically and politically. I agree with some of her critiques on an aesthetic level—I don't love Knausgård or Maggie Nelson either—but, as I said on Substack, I think she's observing an autonomous cultural dialectic, as well as paying too much attention to meaningless pop culture and fashionable pseudo-intellectual nonsense ("climate grief," please), and not really peering into the essence of the current economic order, which, as today's bad review in Compact suggests, she doesn't even really grasp. I don't either, but then I don't pretend to. Plus, her own prose style, as several reviewers pointed out and as anyone might notice, abjures the formal corollary of mediated thought in the Marxist critical theory tradition, i.e., Jameson's Anglicizing of the magisterial world-digesting architectonic sentences of Kant and Hegel and Adorno, and instead itself indulges in a certain vulgar and staccato burble.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You probably remeber this scene from Django Unchained (2012) by Tarantino.

There’s a moment in Django when Dr. Schultz and Calvin Candie discuss Alexandre Dumas, the author of The Three Musketeers. Dr. Schultz speculates that Dumas would not have approved of Candie’s decision to feed one of his slaves to a pack of dogs while he was still alive. Candie inquires, “soft-hearted Frenchman?” to which Schultz responds, “Alexandre Dumas is black.” At this point, we the audience are supposed to fall out of our chairs, because it’s just so badass. If you take a step back from this, you realize it only happens so the audience can feel comfortable in their belief that slave-owners were uneducated idiots, but, yes, Alexandre Dumas was of African descent. He was actually one-quarter black.

His paternal grandfather was Marquis Alexandre-Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie, a French nobleman who fell in love with a slave named Marie-Cesette ( an Afro-Carribean creole of mixed African and French ancestry). He took her as a concubine and they had a mixed race son: Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

This is him (and he was pretty badass!!!)

He was the first person of color in the French military to become brigadier general, divisional general and general-in-chief of a French army. Thomas-Alexandre’s strength was a legend and Napoleon admired his bravery and appreciated his military expertise.

He married Marie-Louise Elizabeth Labouret (a white woman) and they had two daughters and a son, the famous Alexandre Dumas.

But: The issue of racism was never far from Dumas father and son.

Being of mixed race affected Thomas all his life: He was born into slavery because of his mother's status. In order to give him access to education, his father took the boy with him to France where Slavery had been illegal since 1315.

When he proposed to join the army, his father only agreed on condition that he enlisted under his mother's name , in order to preserve the family's reputation.

When he was a young man,while he was accompanying an elegant (white) lady to the theater , an officer decided that it would be good fun to insult the black aristocrat. First, he pretended to mistake the young man of colour for the lady's lackey. Then, after an affray, he forced Thomas to kneel in front of him and ask for pardon.

And those racial abuses happened time and time again.

As for Alexandre, his fellow novelist Balzac referred to him as ‘that negro” and although his books were revered by his contemporaries, he was often mocked for his colour.

His own mother has issues with his mixed origins : before giving birth to Alexandre,she had seen a puppet show with a black devil called Berlick, and she had been terrified at the prospect of” giving birth to a Berlick”.

Dumas’ quick wit served him well when he was attacked: he famously remarked to a white man who insulted him about his mixed-race background with the following words: “My father was a mulatto, my grandfather was a Negro, and my great-grandfather a monkey. You see, Sir, my family starts where yours ends.”

Dumas said nothing of the racial abuse directed at his father. He adored him though: he has fictionalised many of his father's real-life exploits in The Three Musketeers .

At the start of the novel, d'Artagnan's father tells his son, "never submit quietly to the slightest indignity", for "it is by his courage alone that a gentleman makes his way nowadays…” I’d like to think that it is his way to pay hommage to his father who remained strong and dignified in the face of oppression.

Here original post on Quora

#vavuskapakage#alexandre dumas#black writers#literature#literature history#french writers#french author#slavery#django#django unchained#quentin tarantino#quora answers#quoradaily#quora questions

142 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I've seen ur Italian Literature recoms. and it's really helpful. Do you, by any chance, read French Literature too? If so, can you suggest some?

hi anon, sorry for the lateness but I'm going to give this a crack - ofc for obvious reasons as in I'm italian and not french I'm entirely less familiar with french lit that you'd study in school than with italian ones and my knowledge of contemporary french lit is subzero so I can only help you with classics but

I'm going to go straight for it and start with the 19th century novelists for reasons sorry if I go like not in chronological order but

as alexandre dumas wrote my second-favorite book in existence (the three musketeers) and is also one of my favorite writers ever I'll recommend you the d'artagnan romances (musketeers, twenty years later and the viscount of bragelonne) which are long but are all very easy to go through - honest the best thing with dumas is that while he's everything but synthetic you don't feel it, do start with musketeers because it's honestly out of this world good

also honest dumas hasn't written a book that's not entertaining but do read the count of montecristo you really really do want to it's amazing and my second-fave of his after the aforementioned d'artagnan books

talking about 19th century novelists... I mean you really wanna read victor hugo, mind that you have to be in the mood for it because most of his stuff is heavy/long but it's also incredibly well-written and you breeze through it if you vibe with it - maybe you can start with his theater and in that case anything is good though I'm partial to le roi s'amuse for obv reasons (as in they got rigoletto from that plot xD), but wrt novels I'd go with notre dame de paris, les miserables and the man who laughs first, starting with notre-dame because it's shorter and you get a better idea, but my friend les mis is just... I mean I honestly think if you don't read that book you miss out on some of the most amazing literature that ever was so there's that

and going back to another of my fave books ever, do try stendhal - my favorite is the red and the black which has honestly the most delicious terrible amoral protagonist ever and I just really love it, but the charterhouse of parma is also p. great

discussing the other heavyweights of 19th century french novels I personally did enjoy what zola I read more than I enjoyed what balzac I read but I also have no idea what's translated in english or not since not all of them didn't get translated in italian anyway but like if you want to give it a go wrt what you can expect from it with zola I'd go with therese raquin and with balzac either eugenie grandet or lost illusions (?? idk the english title)

meanwhile moving wrt flaubert you really wanna read madame bovary

also alexandre dumas's son - who has the same name as the father so you'll find him as alexandre dumas fils - has the dame of the camelias/la dame aux camelias which is where they took la traviata from and T__T I love iittt

and to finish with 19th century people, you want to try out maupassant too - any short story collection will do you good I think but if you want to try novels I'd go for bel ami

that is to say I haven't touched 19th century genre fiction but I mean... jules verne is a classic™, try out around the world in 80 days, journey to the center of the earth and 20000 leagues under the sea first and then if you like them you'll probably enjoy everything else

talking about classics, another one of my favorite books ever™ is laclos's dangerous liasons which is previous century but like... go for it

for more modern novels I do like a lot radiguet's the devil in the flesh and camus's the plague, there's other stuff I've meant to check for a while especially genre but I haven't gotten around to it yet :(

aaand I mean.... if you're very daring and you're into it I mean I feel bad leaving marcel proust out of a post about classic french literature recs because like in search of lost time is a... founding thing in french literature but like it's the kind of thing that you should read a) when you have a lot of time b) when you're in the mood c) when you're already familiar with most of ^^^^ the above stuff because otherwise it would just go over one's head and it's like seven books so I'm mentioning it because I have to and it's a great book but like if you aren't familiar with previous french literature I'd advise starting from something easier XD

now that was what I can give you for the novels but for everything else:

theater wise you're good with anything by moliere - any play of his is good, I can give you tartuffe, don juan, the miser and the misanthrope to have a few titles but most of his stuff is good

voltaire's work is in general a+ from philosophy to anything else and he's also very accessible, I'd start with candide if you want one thing

if you want to try more philosophers montaigne's essays are great, pretty accessible and have influenced also english writers and so on so he's the one I'd go for

(do not for the love of yourself ever read rousseau DON'T DO IT ANON DON'T DO IT THIS IS AN ANTI-REC)

wrt poetry I mean... if you want to go back to medieval times you can have a knock out of the chanson de roland for like EPIC POEM TIMES - I enjoyed studying it in high school admittedly but I guess it's not fundamental™ unless that's what you're interested in but as half of the few poets I actually do like are french...

my favorite of them is paul verlaine - I checked wiki and in english you can find not all of them but like do try fetes galantes, songs without words and poems under saturn, then there's charles baudeleaire for which you can get les fleurs du mal (I SHOULD hope there's a decent english translation around at least), and then arthur rimbaud, personally I just got a book with his full works and it worked great for me but for specific ones, a season in hell is his most famous, and like I have no idea if they translated verlaine's les poets maudits into english but it could be a good start for that whole branch of poetry

aaand I mean... that's what I feel comfortable recommending but if any of my french followers/french speaking followers who know more about this than me would like to chime in do feel free to! :D I might tag someone in the comments when my brain like starts working because I've been copying notes for the entire afternoon while writing this and I'm braindead but if any of you finds it before I tag you really go ahead XD

#literature#french literature#i accept corrections on everything but rousseau#anyone who can afford to NOT read that jerk should take the chance to#and NOT ever read any of his incoherent crap#sorry i have feelings about how much i hate his ass lmao

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

On one occasion, he did not move for four hours, the time it took him to finish a large novel by Balzac, from start to finish. Then he would undertake his long tour of the bookshops, after which he would go to another café where he would sit but not mix with a few acquaintances of his with semi-intellectual pretensions. He would listen (to “their nonsense”) and hardly say a word, then, after all these marathon sittings and feeble peregrinations, return home on the bus. He is always described as walking wearily along, looking very distinguished, but with a somewhat careless gait, his eyes alert and holding in his hand a leather bag crammed with the books and cakes and biscuits on which he would have to survive until evening, since lunch was never served at home. He carried that famous bag with great nonchalance, quite unconcerned that volumes of Proust should be sitting cheek by jowl with titbits and even courgettes. Apparently the bag always contained more books than were strictly necessary, as if it were the luggage of a reader setting off on a long journey, who was afraid he might run out of reading matter while away. According to his wife, he always had some Shakespeare with him, so that “he could console himself with it if he should see something disagreeable” on his wanderings.

Javier Marías, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa in Class, _Written Lives_

#javier marias#guiseppe tomasi di lampedusa#lampedusa#Shakespeare#william shakespeare#proust#marcel proust#balzac#honore de balzac#novel#walk#walks#reading#prose#biography#literature#literary

13 notes

·

View notes