Text

I’m doing Na(MaIncProOnYo)NoWriMo.

National (Make Incremental Progress On Your) Novel Writing Month!

I’m just trying to average 500 words a day. Enough to make palpable progress without getting bogged down and overwhelmed.

Join in!

I am neither doing NaNo nor skipping NaNo, but a secret third thing…

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

How "In Medias Res" ACTUALLY Works (& When to Use It)

I haven’t ever done an article on in medias res in part because it’s been covered so much in the writing world already, what could I really add to it that you probably haven’t heard? Well, after looking around online … it turns out, quite a few things. I sometimes feel that in medias res gets misunderstood, and overused.

As most people who teach about in medias res will tell you within four seconds, “in medias res” is Latin that translates to “in the midst of things.” In some ways, this is pretty straightforward: Instead of starting a story with exposition or setup, you start with the action or conflict. Most people will cite that this will grab the reader and draw them into the story.

As someone who has read thousands of unpublished manuscript openings though, I’ll tell you that a lot of times, it doesn’t. But I’m getting ahead of myself, let me backtrack a bit (speaking of starting something in the “middle of things” 😉)

Back when I was a “young” writer, when the topic came up of how to start a story, it was often, if not almost immediately, followed up by talking about in medias res. “If you don’t know how to start the story, start in medias res”–I was told time and again.

So like many people, I thought that if I had bombs going off or someone dying in the first paragraph, that it would for sure hook the audience and get them to keep reading–and it’d be a great opening too!

Years later, when navigating submission piles, it soon became apparent to me that this often wasn’t the best way to start. I could only handle so many “bombs going off” (metaphorically or literally) and “war battles” (metaphorically or literally), and I could only handle them for so long … before they got boring. (And to add to it, often newer writers, in their efforts to make it “exciting,” make it unnecessarily graphic to the point of being grotesque.)

In contrast to what many people teach, in medias res can actually get rather boring within paragraphs or pages if it isn’t done well. Because in medias res means cutting off the exposition and setup, it also means cutting off the context. If I have no clue who to care about, how we got here, and why what is happening matters, it can be really difficult to get invested in the story. After reading several paragraphs of people being run through with swords, I start wondering, Why does this matter? And why do I care?

And immediately teaching about in medias res when someone asks how to start a story often isn’t a great way to teach how to start a story. After all–you’re actually cutting off the starting of the story.

Of course, like anything, beginning in medias res can be great when done well and for the right effect. But in order to do that, you need to understand how it actually works and what that effect is.

For starters, it’s helpful to not think of in medias res as only being used for story openings. You can use in medias res for any scene at any point in the story. So let’s talk about how this works on the scene level, and then talk about it on the narrative level.

In Medias Res in Scenes

Typically, a scene is defined as a unit of action that takes place in a single location and continuous time. But this definition is certainly not perfect and the boundaries can get blurry fast with the right examples. However, I think most can agree that a scene is one of the smallest recognized structural units in a story.

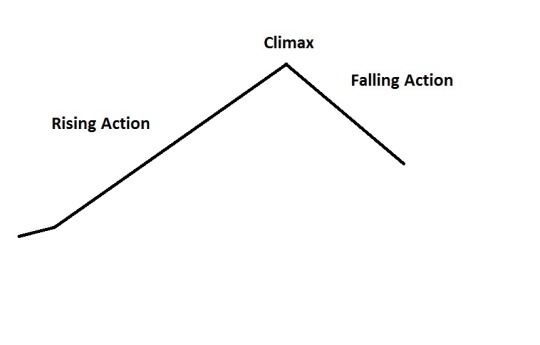

And all structural units–whether they’re a scene, sequence, act, or whole story–fit into this shape:

A scene will usually start with a hook and setup, followed by rising action (conflict), a climax, and a falling action. In some cases, some of these may be left out, but scenes almost always contain these things.

You can find slightly different approaches to scene structure from different sources.

For example, recently, I talked about scene structure according to Dwight V. Swain, who is famous for his approach. (In fact, his approach may arguably be the most famous.)

He recognizes two types of the smallest structural unit: scene and sequel (you can learn about them in more detail in “Scene Structure According to Swain” and “Sequel Structure According to Swain.”)

The scene is made up of three parts: goal, conflict, and disaster. And the sequel is also made up of three parts: reaction, dilemma, decision. But regardless, both still fit into the structure above.

In medias res means “in the midst of things,” so instead of starting with the hook and setup, you drop the audience right into the rising action, or in some cases, even climax. (And the conflict or climax often becomes the hook.)

The setup portion is used to ground the audience in the scene–it conveys when and where the scene takes place, who is in the scene, the character’s goal, may lay out the stakes, and if there are multiple viewpoint characters, will clue the audience into whose viewpoint they are in. (For more on all this and scene openings, see “4 Key Elements of Scene Openings.”) This orients the reader and gives context for what is about to happen. It gives meaning to the rising action.

When you start in medias res, the audience lacks this context.

In this way, beginning in medias res is a lot like writing a teaser, which also works off a lack of context. In a teaser, the whole point is to tease the audience through a lack of context. The teaser promises that if the audience keeps reading, they will get more context to understand what just happened. This is often a great way to use in medias res.

But just like a teaser, the audience won’t stick around if context is withheld from them for too long. Like me going through submission piles, they start wondering, Why does this matter? And why should I care? Teasers only work well when they are short.

So, when you start in medias res, the audience can only handle so much of being “in the midst of things” before getting antsy for information. Contrary to what many writing instructors might advise, I would argue that starting in medias res is often harder, because the writer must fill the audience in on everything they are missing–and they must do it sooner rather than later. And often for newer writers, this leads to big dumps of information, setting, worldbuilding, characterization, stakes, goals–and whatever else–in the middle of conflict and action. Or, it might lead to the dreaded flashback. This is a tough situation to be in, even for the best of us, because one small reason that stuff is in the setup is so it doesn’t clutter and kill the pacing of the conflict. It’s so we can focus on the conflict.

Sure, some context will be easy to squeeze into the rising action. For example, you can convey the viewpoint character rather quickly. In fact, you can slip in most information in a line or two if you are well-practiced. But the problem is, it’s often a line or two per thing: goal, character, stakes, setting, motive, and any other background info. That’s a tall order.

Now, with all that said, you may think I’m against starting in medias res. I’m not. I’m just pointing out how difficult it can be, especially for newer writers, and yet we are often telling them to do it. I mean, no wonder beginning writers have so many flashbacks and info-dumps in their openings–they’re being (indirectly) led to do that.

In medias res can work great in a few situations:

As a teaser: As stated above, starting in medias res is a lot like writing a teaser. The audience doesn’t know the full context, and that’s the point. The promise is that they will get more information if they keep reading, so instead of being drawn into the story because of the goals, stakes, and conflict, they are drawn into the story because of mystery, intrigue, and curiosity. The tone of the story is often conveyed, cluing the audience into what sort of emotions they can expect if they stick around. The audience won’t stick around for long without important context, so the scene either needs to be brief, or the text needs to start filling the audience in after teasing them.

The setup information doesn’t really matter: Sometimes how the character got to the rising action of the scene isn’t really important to the story. For example, a story may open with a sword fight in medias res, but the fight doesn’t really matter that much to the actual plot. It might instead be used to showcase the protagonist. Reading about a sword fight with no context can get boring. Reading about a sword fight told through a strong viewpoint character can be fascinating. And if he does a lot of sword fighting and is skilled in it, this might be an excellent way to illustrate that. You will of course still need to fill in some setup. But because the conflict itself isn’t vital, you won’t need to struggle explaining everything that led to this moment.

Other times the conflict does matter because the result kicks the plot in a new trajectory by affecting what happens next, but the setup isn’t important because it’s simple, mundane, obvious, or easily implied. It doesn’t really need to take up that space to set the stage. For example, say we have a scene where some kids are playing hide-and-seek in the woods and one finds a treasure chest. The setup (which would involve starting the game) may not be very important. So instead, we might start with the “seeker” already finding one or two kids. Finding the treasure will be the scene’s turning point, and change the direction of the plot as the kids decide what to do with the coins and jewels.

The audience already knows the setup: If you are writing about a famous event, such as 9/11 or Lincoln’s assassination, you may not need to include the setup–the audience already knows what led to the conflict or climactic moment.

Other than that, if the in medias res scene isn’t the opening scene, then it’s possible a prior scene already established enough of the setup. The audience knows the goal and stakes, the time and place, because it was stated or implied. So instead, we can cut right to the action.

With all this said, almost no scene requires you start in medias res. So rather than stress if a scene should start in medias res, ask yourself if starting in medias res is more effective for the story you want tell.

In Medias Res in Narrative Arcs

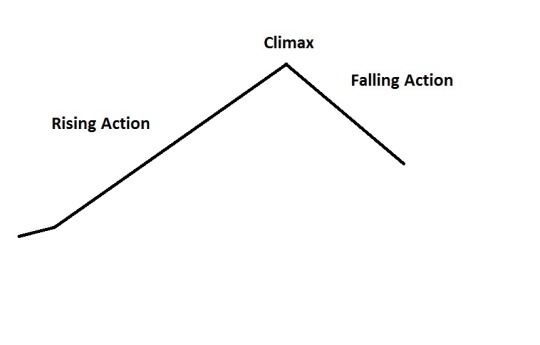

Because all structural units follow the same shape …

… you can essentially do this to the story as a whole.

The setup of a whole story covers about everything prior to the inciting incident. The inciting incident is a disruption that kicks off the plot of the story and is either a problem or an opportunity for the protagonist. The setup introduces us to the characters, setting, and establishes a sense of what’s normal.

Keep reading

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Trellis

Pantsuit

Ball-point pen

Parts of a ball-point pen

On-ramp

Precinct

Syringe

Parts of a syringe

High tops

Coupe

Knit jacket

Parts of a jacket

These are not brainwashing trigger words or the world’s worst shopping list. This is just what the Google search history of an author looks like.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

no google docs you don't understand this is a sexy, necessary grammar mistake

104K notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s also a large grey area between an Offensive Stereotype and “thing that can be misconstrued as a stereotype if one uses a particularly reductive lens of interpretation that the text itself is not endorsing”, and while I believe that creators should hold some level of responsibility to look out for potential unfortunate optics on their work, intentional or not, I also do think that placing the entire onus of trying to anticipate every single bad angle someone somewhere might take when reading the text upon the shoulders of the writers – instead of giving in that there should be also a level of responsibility on the part of the audience not to project whatever biases they might carry onto the text – is the kind of thing that will only end up reducing the range of stories that can be told about marginalized people.

A japanese-american Beth Harmon would be pidgeonholed as another nerdy asian stock character. Baby Driver with a black lead would be accused of perpetuating stereotypes about black youth and crime. Phantom Of The Opera with a female Phantom would be accused of playing into the predatory lesbian stereotype. Romeo & Juliet with a gay couple would be accused of pulling the bury your gays trope – and no, you can’t just rewrite it into having a happy ending, the final tragedy of the tale is the rock onto which the entire central thesis statement of the play stands on. Remove that one element and you change the whole point of the story from a “look at what senseless hatred does to our youth” cautionary tale to a “love conquers all” inspiration piece, and it may not be the story the author wants to tell.

Sometimes, in order for a given story to function (and keep in mind, by function I don’t mean just logistically, but also thematically) it is necessary that your protagonist has specific personality traits that will play out in significant ways in the story. Or that they come from a specific background that will be an important element to the narrative. Or that they go through a particular experience that will consist on crucial plot point. All those narrative tools and building blocks are considered to be completely harmless and neutral when telling stories about straight/white people but, when applied to marginalized characters, it can be difficult to navigate them as, depending on the type of story you might want to tell, you may be steering dangerously close to falling into Unfortunate Implications™. And trying to find alternatives as to avoid falling into potentially iffy subtext is not always easy, as, depending on how central the “problematic” element to your plot, it could alter the very foundation of the story you’re trying to tell beyond recognition. See the point above about Romeo & Juliet.

Like, I once saw a woman a gringa obviously accuse the movie Knives Out of racism because the one latina character in the otherwise consistently white and wealthy cast is the nurse, when everyone who watched the movie with their eyes and not their ass can see that the entire tension of the plot hinges upon not only the power imbalance between Martha and the Thrombeys, but also on her isolation as the one latina immigrant navigating a world of white rich people. I’ve seen people paint Rosa Diaz as an example of the Hothead Latina stereotype, when Rosa was originally written as a white woman (named Megan) and only turned latina later when Stephanie Beatriz was cast – and it’s not like they could write out Rosa’s anger issues to avoid bad optics when it is such a defining trait of her character. I’ve seen people say Mulholland Drive is a lesbophobic movie when its story couldn’t even exist in first place if the fatally toxic lesbian relationship that moves the plot was healthy, or if it was straight.

That’s not to say we can’t ever question the larger patterns in stories about certain demographics, or not draw lines between artistic liberty and social responsibility, and much less that I know where such lines should be drawn. I made this post precisely to raise a discussion, not to silence people. But one thing I think it’s important to keep in mind in such discussions is that stereotypes, after all, are all about oversimplification. It is more productive, I believe, to evaluate the quality of the representation in any given piece of fiction by looking first into how much its minority characters are a) deep, complex, well-rounded, b) treated with care by the narrative, with plenty of focus and insight into their inner life, and c) a character in their own right that can carry their own storyline and doesn’t just exist to prop up other character’s stories. And only then, yes, look into their particular characterization, but without ever overlooking aspects such as the context and how nuanced such characterization is handled. Much like we’ve moved on from the simplistic mindset that a good female character is necessarily one that punches good otherwise she’s useless, I really do believe that it is time for us to move on from the the idea that there’s a one-size-fits-all model of good representation and start looking into the core of representation issues (meaning: how painfully flat it is, not to mention scarce) rather than the window dressing.

I know I am starting to sound like a broken record here, but it feels that being a latina author writing about latine characters is a losing game, when there’s extra pressure on minority authors to avoid ~problematic~ optics in their work on the basis of the “you should know better” argument. And this “lower common denominator” approach to representation, that bars people from exploring otherwise interesting and meaningful concepts in stories because the most narrow minded people in the audience will get their biases confirmed, in many ways, sounds like a new form of respectability politics. Why, if it was gringos that created and imposed those stereotypes onto my ethnicity, why it should be my responsibility as a latina creator to dispel such stereotypes by curbing my artistic expression? Instead of asking of them to take responsibility for the lenses and biases they bring onto the text? Why is it too much to ask from people to wrap their minds about the ridiculously basic concept that no story they consume about a marginalized person should be taken as a blanket representation of their entire community?

It’s ridiculous. Gringos at some point came up with the idea that latinos are all naturally inclined to crime, so now I, a latina who loves heist movies, can’t write a latino character who’s a cool car thief. Gentiles created antisemitic propaganda claiming that the jews are all blood drinking monsters, so now jewish authors who love vampires can’t write jewish vampires. Straights made up the idea that lesbian relationships tend to be unhealthy, so now sapphics who are into Brontë-ish gothic romance don’t get to read this type of story with lesbian protagonists. I want to scream.

And at the end of the day it all boils down to how people see marginalized characters as Representation™ first and narrative tools created to tell good stories later, if at all. White/straight characters get to be evaluated on how entertaining and tridimensional they are, whereas minority characters get to be evaluated on how well they’d fit into an after school special. Fuck this shit.

64K notes

·

View notes

Text

I fan cast my characters twice. Once for appearance and once for personality. It helps me imagine and describe the character to pick the actor I’d like to see play them, but it helps me bring the character to life to pick someone whose attitude I want them to emulate. Honestly, I find it easier to write for a character once I figure out whose behavior they remind me of rather than just who they look like.

I made so much better progress writing for my antagonist when I realized that he probably talks like Gordon Ramsay regardless of which celebrity he looks like.

#oc#writers#write#writing#writers on tumblr#writblr#creative writing#fiction#characters#original characters#ocs#fan cast#fancast

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

When editing my stories, there are two primary questions I’m asking throughout.

Is it clear what’s happening?

Does the writing conjure feeling?

Obviously, there are large-scale rewrites that occur, but almost every small-scale change aims to reword, rearrange, or replace what’s already there to better answer those two questions with an emphatic, “YES.”

#writing#creative writing#writing advice#writing tips#oc#writers#write#writblr#writeblr#editing#edit#saved in the edit

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

My summer always ends with the same, sad song.

Every summer, I get back to writing again. I get back to telling my stories. And it reminds me how much I love it, more than anything else. When I’m writing, I feel this sense of urgency to finish my work, to put it out there - but I also feel this intense focus and purpose and peace.

I’m a teacher, and my normal job more than fulfills the need to do something meaningful, to do something with purpose. But summer break always reminds me that writing is my original dream. When I started to write in 2nd Grade, it was the first time in my life that I felt like I had found what I wanted to do with my life. I’ve never given up on it, even when adulthood tries to block it out of my life. But my dream persists.

And so my summer always ends with the same, sad song. It’s a song of farewell, with a touch of anger, as I prepare to say “until we meet again” to a love that I have only just reunited with. Work, adulthood, a great man things try to get in the way, but I won’t let them stop me. One day, my name will be on a book that sits on bookstore shelves.

Mark my words.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

crowley/loki crossover when 🤨

Not my department. That's fanfiction, which means it's up to you lot.

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

The way we write romance stories are so unrealistic and it relies on the readers part to have enough self awareness to know that this is an escape from reality and not reality itself. Opinions?

What a great point! If we cannot suspend disbelief, then what’s the point of fiction? There’s still something satisfying about a story that feels like it COULD happen, and fictional relationships need to feel NATURAL, of course. But what the serendipity that happens on a daily basis in real life? And where would we be without fiction’s flights of fancy? As always, it is about balance in all things :)

Keep writing!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tip

The joy of editing can be discovered in finding new and better ways to say things you thought you had already said.

I always thought that I hated editing. That I hated second drafts. It turns out that I always moved from project to project so fast that I never really had the chance to sit down and work on a second draft. Well, I am now entrenched deeper in a second draft project than I have ever been before, and I have learned that, to my surprise . . . I actually really enjoy the editing phase! I am enjoying writing my second draft!

My disdain from editing as a younger writer always stemmed from pride and perfectionism. I didn’t like the idea of second drafts because I wanted to put the time and thought and care and creativity into saying it the right way from the very beginning. It turns out that even with such agony, a rough draft is never anything more than a rough draft.

In the years since, my opinions on “shitty first drafts” have reversed. My battles with writer’s block have convinced me that the only way to finish most drafts is to just put SOMETHING down until you reach the end, no matter how bad it is, and then suck it up and edit later. And let me tell you . . . I have had more fun editing my first draft and creating my second draft than I ever expected. And it’s because of this writing tip I am sharing today.

All that pride and perfectionism I used to agonize over in the rough draft, I am now discovering to greater effect in the second. I left almost an entire year between completing my shitty first draft and editing my second, and that distance allowed me to get my head out of the clouds and actually examine the writing critically. The result is that I have found so much unexpected joy in the process of reading old writing and then being struck with the thought, “You know what? A year ago, I wrote this because this is how I thought this scene was supposed to go, but now I see that it would be so much better if it went like THIS!” I have managed to find joy even in re-writing entire chapters because of the joy that I have found in discovering the better version of something you already wrote. I highly recommend it.

#writing tips#writing tip#oc#writing#creative writing#writers#write#writeblr#shitty first drafts#shitty rough drafts#creative writers#fiction#fiction writing#editing#writing advice#advice for writers#editing tips#second drafts

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh you’re a fan of my writing? name five of the unfinished stories sitting in my drafts

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing advice from my uni teachers:

If your dialog feels flat, rewrite the scene pretending the characters cannot at any cost say exactly what they mean. No one says “I’m mad” but they can say it in 100 other ways.

Wrote a chapter but you dislike it? Rewrite it again from memory. That way you’re only remembering the main parts and can fill in extra details. My teacher who was a playwright literally writes every single script twice because of this.

Don’t overuse metaphors, or they lose their potency. Limit yourself.

Before you write your novel, write a page of anything from your characters POV so you can get their voice right. Do this for every main character introduced.

205K notes

·

View notes

Text

you don’t get good at doing something by not doing it

you get good at doing something by doing it badly and learning how to do it better

59K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Absolutely obsessed with this thread of anons documenting and exposing a writer’s overwhelmingly blatant muscle fetish bleeding into everything he’s ever worked on

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Writing Tip

I feel like I shouldn’t even say this but it has legitimately helped me in the past so here it goes....

If you’re suffering from writer’s block, write the smutty version of what comes next just to get writing again, get you through to the next scene, and get you excited about your story again. You can then go back and replace it with what actually happens.

But you didn’t hear that from me.

#writing tip#writing advice#write#writers#writing#writeblr#writblr#writer’s block#dark writing tip#wip#creative writing

202 notes

·

View notes