Text

I turn 35 tomorrow. How better to celebrate that than with some notes on the handful of video games I have managed to finish over the last ten months. In no particular order:

Judgment (PS4)

Something I think about often is that there aren’t many games which are set in the real world. By this I man the world in which we live today. You can travel through ancient Egypt or take a trip through the stars in the far future, but it’s relatively rare to be shown a glimpse of something familiar. Hence the unexpected popularity of the new release of Microsoft Flight Simulator, which lets you fly over a virtual representation of your front porch, as well as the Grand Canyon, and so on.

I found something like the same appeal in Judgment, a game which took me longer than anything else listed here to finish — seven or eight months, on and off. Like the Yakuza games to which it is a cousin, it’s set in Kamurocho, a fictional district of a real-world Tokyo; unlike other open-world games, it renders a space of perhaps half a square mile in intense detail. I spent a long time in this game wandering around slowly in first-person view, looking at menus and in the windows of shops and restaurants. The attention to detail is unlike everything I have ever seen, from the style of an air conditioning unit to the range of Japanese whiskies on sale in a cosy backstreet bar. And this was a thing of value at a time when the thought of going anywhere else at all, let alone abroad, seemed like it was going to be very difficult for a very long time.

It’s a game of at least three discrete parts. One of them is a fairly cold-blooded police procedural/buddy cop story: you play an ex-lawyer turned private eye investigating a series of grisly murders that, inevitably, link back to your own murky past. In another part you run around the town getting into hilarious martial arts escapades, battering lowlifes with bicycles and street furniture. In another, you can while away your hours playing meticulous mini-games that include darts, baseball, poker, Mahjong and Shogi — and that’s before we even get to the video game arcades.

All these parts are really quite fun, and if you want to focus on one to the exclusion of the others, the game is totally fine with that. The sudden tonal shifts brought about by these crazy and abrupt shifts in format are, I think, essentially unique to video games. But the scope of Judgment is a thing all its own. As a crafted spectacle of escapist fiction it’s comprehensive, and in its own way utterly definitive.

Mafia: Definitive Edition (PS4)

I was amazed when I found out they were doing a complete remake of Mafia, a game I must have finished at least three or four times in the years after its release back in 2002. Games from this era don’t often receive the same treatment as something like Resident Evil, where players might be distracted by the controls and low-poly graphics of the original.

A quality remake makes it easier for all kinds of reasons to appreciate what was going on there. (Not least because they have a lot of new games in the same series to sell.) But in the early 00s PC games like this one had started to get really big and ambitious, and had (mostly) fixed issues with controls; so there’s a hell of a lot more stuff going on in Mafia than in most games of that era. It was also a very hard game, with all kinds of eccentricities that most big titles don’t attempt today. Really I have no idea how this remake got made at all.

But I was so fond of the original I had to play it. The obvious: it looks fantastic, and the orchestral soundtrack is warm and evocative. The story is basic, but for the era it seemed epic, and it’s still an entertaining spectacle. The original game got the balance of cinematic cutscenes, driving and action right the first time, even while Rockstar were still struggling to break out of the pastiche-led GTA III and Vice City.

They have made it easier. You’re still reliant on a handful of medical boxes in each level for healing, but you get a small amount of regenerating health as well. You no longer have to struggle to keep your AI companions alive. Most of the cars are still heavy and sluggish, but I feel like they’re not quite as slow as they once were. They’ve changed some missions, and made some systems a little more comfortable — with sneaking and combat indicators and so on — but there aren’t any really significant additions.

The end result of all this is that it plays less like an awkward 3D game from 2002, and more like a standard third-person shooter from the PS3/360 era. Next to virtually any other game in a similar genre from today, it feels a bit lacking. There’s no skill tree, no XP, no levelling-up, no crafting, no side-missions, no unusual weapons or equipment, no alternative routes through the game. And often all of that stuff is tedious to the extreme in new titles, but here, you really feel the absence of anything noteworthy in the way of systems.

My options might have been more limited in 2002 but back then the shooting and driving felt unique and fun enough that I could spend endless hours just romping around in Free Ride mode. Here, it felt flat by comparison; it felt not much different to Mafia III, which I couldn’t finish because of how baggy it felt and how poorly it played, in spite of it having one of the most interesting settings of any game in recent years. But games have come a long way in twenty years.

Hypnospace Outlaw (Nintendo Switch)

If this game is basically a single joke worked until it almost snaps then it is worked extremely well.

It seems to set itself up for an obvious riff on the way in which elements of the web which used to be considered obnoxious malware (intrusive popups and so on) have since become commonplace, and sometimes indispensable, parts of the online browsing experience. But it doesn’t really do that, and I think that’s because it’s a game which ends up becoming a little too fascinated by its own lore.

The extra science fiction patina over everything is that technically this isn’t the internet but a sort of psychic metaverse delivered over via a mid-90s technology involving a direct-to-brain headset link. I don’t know that this adds very much to the game, since the early days of the internet were strange enough without actually threatening to melt the brains of its users.

(This goes back to what I said about Judgment - I sometimes wonder if it feels easier to make a game within a complete fiction like this, rather than simply placing it in the context of the nascent internet as it really was. Because this way you don’t have to worry too much about authenticity or realism; this way the game can be as outlandish as it needs to be.)

But, you know. It’s a fun conceit. A clever little world to romp around in for a while.

Horace (Nintendo Switch)

I don’t know quite where to begin with describing this. One of the oddest, most idiosyncratic games I’ve played in recent years.

As I understand it this platformer is basically the creation of two people, and took about six years to make. You start out thinking this is going to be a relatively straightforward retro run-and-jump game — and for a while, it is — but then the cutscenes start coming. And they keep coming. You do a lot of watching relative to playing in this game, but it’s forgivable because they are deeply, endearingly odd.

It’s probably one of the most British games I’ve ever played in terms of the density and quality of its cultural references. And that goes for playing as well as watching; there’s a dream sequence which plays out like Space Harrier and driving sequences that play out like Outrun. There are references to everything from 2001 to the My Dinner with Abed episode of Community. And it never leans into any of it with a ‘remember that?’ knowing nod — it’s all just happening in the background, littered like so much cultural detritus.

A lot of it feels like something that’s laser-targeted to appeal to a certain kind of gamer in their mid-40s. And, not being quite there myself, a lot of it passed me by. Horace is not especially interested in a mass appeal — it’s not interested in explaining itself, and it doesn’t care if you don’t like the sudden shifts in tone between heartfelt sincerity and straight-faced silliness. But as a work of singular creativity and ambition it’s simply a joyous riot.

Horizon: Zero Dawn (PS4)

I stopped playing this after perhaps twelve or fifteen hours. There is a lot to like about it; it still looks stunning on the PS4 Pro; Aloy is endearing; the world is beautiful to plod around. But other parts of it seem downright quaint. It isn’t really sure whether it should be a RPG or an action game. And I’m surprised I’ve never heard anyone else mention the game’s peculiar dedication to maintaining a shot/reverse shot style throughout dialogue sequences, which is never more than tedious and stagey.

The combat isn’t particularly fun. Once discovered most enemies simply become enraged and blunder towards you, in some way or another; your job is to evade them, ensnare them or otherwise trip them up, then either pummel them into submission or chip away at their armour till they become weak enough to fall. I know enemy AI hasn’t come on in leaps and bounds in recent years but it’s not enough to dress up your enemies as robot dinosaurs and then expect a player to feel impressed when they feel like the simplest kind of enrageable automata. Oh, and then you have to fight human enemies too, which feels like either an admission of failure or an insistence that a game of this scale couldn’t happen without including some level of human murder.

I don’t have a great deal more to say about it. It’s interesting to me that Death Stranding, which was built on the same Decima engine, kept the frantic and haphazard combat style from Horizon, but went to great lengths to actively discourage players from getting into fights at all. (It also fixed the other big flaw in Horizon — the flat, inflexible traversal system — and turned that into the centrepiece of the game.)

Disco Elysium (PS4)

In 2019 I played a lot of Dungeons and Dragons. I’m talking about the actual tabletop roleplaying game, not any kind of video game equivalent. For week after week a group of us from work got together and sort of figured it out, and eventually developed not one but two sprawling campaigns of the never-ending sort. We continued for a while throughout the 2020 lockdown, holding our sessions online via Roll20, but it was never quite the same. After a while, as our life circumstances changed further, it sort of just petered out.

I mention all this because Disco Elysium is quite clearly based around the concept of a computerised tabletop roleplaying game (aka CRPG). My experience of that genre is limited to the likes of Baldurs Gate, the first Pillars of Eternity and the old Fallout games, so I was expecting to have to contend with combat and inventory management. What I wasn’t expecting was to be confronted with the best novel I’ve read this year.

To clarify: I have not read many other novels this year, by my standards. But, declarations of relative quality aside, what I really mean is that this game is, clearly and self-consciously, a literary artefact above all. It is written in the style of one of those monolithic nineteenth century novels that cuts a tranche through a society, a whole world — you could show it to any novelist from at least the past hundred years and they would understand pretty well what is going on. It is also wordy in every sense of that term: there’s a lot of reading to do, and the text is prolix in the extreme.

You could argue it’s less a game than a very large and fairly sophisticated piece of interactive fiction. The most game-like aspects of it are not especially interesting. It has some of the stats and the dice-rolling from table-top roleplaying games, but this doesn’t sit comfortably with the overtly literary style elsewhere. Health and morale points mostly become meaningless when you can instantly heal at any time and easily stockpile the equivalent of health potions. And late on in the game, when you find yourself frantically changing clothes in order to increase your chances of passing some tricky dice roll, the systems behind the game start to feel somewhat disposable.

Disco Elysium is, I think, a game that is basically indifferent to its own status as a game. Nothing about it exists to complement its technological limitations, and nor is it especially interested in the type of unique possibilities that are only available in games. You couldn’t experience Quake or Civilisation or the latest FIFA in any other format; but a version of Disco Elysium could have existed on more or less any home computer in about the last thirty years. And, if we were to lose the elegant art and beautiful score, and add an incredibly capable human DM, it could certainly be played out as an old-fashioned tabletop game not a million miles from Dungeons and Dragons.

All of the above is one of the overriding thoughts I have about this game. But it doesn’t come close to explaining what it is that makes Disco Elysium great.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Years ago, back in the times when I went to such things, I was at a poetry evening or some kind of screening, and I saw a short film made up of a collage of scenes from movies where characters are writing. You can imagine the sort of thing, because it is a fairly ripe cliche — a lot of scenes of people staring anxiously at a blank page, before starting to scribble at a feverish pace as inspiration hits.

At the time I remember thinking it was quite funny, and very clever. But for some reason it has stuck with me ever since, even though I only saw it the one time. I think about it more often than I think about probably any other film I saw that year. I thought it was funny because it so effortlessly showed up the silliness of that familiar movie routine, and I thought it was touching because it demonstrated our need to construct little stories in our lives about familiar actions. All that frantic action has to come to something, because it would be awful if it came to nothing.

But nobody has ever written like this, have they? This is not what it feels like as I sit here now, at two minutes past nine in the evening, with the faint familiar ache of eye strain across my forehead. And this is only one small way in which movie reality often has little or nothing to do with reality as it is lived. Or rather: reality as I live it, which is really the only thing I am qualified to describe.

Parenting is another one of those things where movie reality so often seems only a distant cousin to where I’m really at now. I struggle to recognise myself in almost any depiction of fatherhood I’ve ever seen elsewhere. Right now I keep trying to find myself in things and failing.

Here are some significant portraits of fatherhood that have always stuck in my mind.

Mufasa in The Lion King

When I was a kid of (I think) around ten years old, I went through a phase of being obsessed with watching The Lion King. I had it on VHS and at one stage I watched it every day, or close to that. At one point I could close my eyes and replay the whole thing inside my head; I could recall every scene and every line of every song in the whole film. It was a good way to fall asleep.

At some point I’m sure I got used to the scene where Simba’s father Mufasa is thrown beneath the stampeding wildebeest herd. This was pretty intense for a children’s film in the late 1990s. The subsequent scene of devastation still conveys how I felt at the time about the idea of losing a parent. It is the stuff of grand tragedy and pathetic fallacy. Mufasa is perfect and life is golden, then he is suddenly taken away, and the world becomes a blasted heath.

Back then I was also desperately worried that something would happen to my parents — that they would either split up, or die, or a combination of both — and then where would I be? I would be alone. Obviously. But then years later when my father actually passed away I discovered that death is really nothing like this. It was tragic only in the sense that it was very sad, and very unfair; it wasn’t tragic like Hamlet is a tragedy. There was no story to it. I was not especially alone, and there was no convenient thunderstorm to underline my emotional state. The world outside mostly carried on as normal, and it was vast and basically indifferent.

Don Davis in Twin Peaks and The X-Files.

Until recently I had never seen a single episode of The X-Files. The show was a total pop culture blind spot for me: I knew nothing about it, apart from the usual blurb about Mulder and Scully. And so when we got to the episode Beyond the Sea, where get to meet Scully’s father for the first time, I was absolutely astonished to find that her dad is played by Don Davis, who also played Major Briggs in Twin Peaks.

This should not be entirely unexpected. That episode came only a few years after the first season of Twin Peaks, which was hugely successful. But it also goes beyond an inside joke because Don Davis plays precisely the same character in both shows: a distant, austere military man, with an otherworldly demeanour. He haunts both shows in the way you might expect a familiar figure of authority to haunt someone. He is an icon of benevolent patrician power. But it is impossible to imagine him as a dad, doing dad things with a baby-faced Dana Scully. He exists in The X-Files only to be almost immediately killed off. He is more important as a cipher than as a character.

Jack Torrance in The Shining

I read The Shining some years after I first saw The Lion King. I'm not sure how many years, honestly, but by then, my fears had developed a little. I was no longer quite so terrified of losing my parents. But the book left me anxious and preoccupied by the idea of a family turning against itself. It was a little like how zombies scared me not because of their blind sociopathic fury, but because of the idea that suddenly someone close to you could suddenly switch, and start coming after you, and never stop.

I didn’t like the idea that my dad could, for whatever reason, try to kill me. I really didn’t like it. That thing of trust suddenly inverting itself into a blind hatred — one that uses all the things you know about a person against themselves — is one of the most unsettling things I can imagine.

Today the story mostly seems to be about the way that dads are damned to destroy others and die themselves. It's one that repeats itself almost every day in the headlines somewhere around the world, outside of the lofty confines of the Overlook.

It goes without saying that the Kubrick film is a masterpiece that has very little to do with anything outside of itself.

Bandit, the dad from Bluey

If you just watch the show you will discover that he is actually the best dad in anything right now.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

It occurred to me recently that I haven’t posted here for about nine months, and that if you knew nothing about me except for this blog, you might think that it something of a cliffhanger that I ended it on a post about expecting the arrival of my first child. (Or perhaps that would have been an entirely fitting way to end it.) Either way: I am fine, and we are fine, and last November brought the arrival of my son Robin into my life. I have been very busy almost every day since.

There are a couple of cliches about parenting that remain indisputably true. The first is that they grow up so fast. And the second is that nothing prepares you for it. We thought we were entirely ready and pretty well informed but from his delivery onwards nothing went as planned. We thought we’d feed him when he was hungry, and we’d put him to sleep when he was tired; and change his nappies, and play with him, and love him; and what else was there to it, really?

It turns out there is a lot more to it than that. Before Robin I never realised how polarised, how strained and how political people’s feelings are about matters of childcare. We’ve ended up raising him in ways we had never previously considered, partly out of necessity, and partly out of the kind of habits that grow into paths of desire across the days. Consciously or not I judge people who do things differently, and no doubt they judge me too. In spite of the reams of available literature it turns out that for many things — perhaps even most things — there isn’t necessarily a right or a wrong way to proceed.

Here is a third cliche that turns out to be extremely valuable: every baby is different.

The question of literature is a tricky one. In search of assistance I read a few parenting manuals; some of these turned out to be better than others, but I’ve yet to find a good book about what it means to be a father. Most books aimed at new dads are of the ‘pull your socks up’ variety — the kind of thing where the author imagined it thrust upon some feckless deadbeat by a weary spouse. But, being reasonably conscientious, and looking for something with a bit more depth than a guide to how to change nappies, I’ve found most books about parenting have little of interest to say to new fathers.

Being a dad is an odd thing to write about. I’ve read and heard people talk about how new mothers ought to be proud to be joining a kind of grand universal maternal tradition, one which predates even humanity itself. (Animals surely know about babies; witness my cat Louie’s endless patience with Robin’s various attempts to pull his ears off.)

People do not generally talk about the grand traditions of fatherhood in this way. And for good reason: a lot of men today wouldn’t be happy to follow the example of their own fathers, let alone imitate the conditions of detachment and distance that defined fatherhood for centuries. I want to say that expectations of fathers today have never been higher; but this is only because for most of recorded history, we had no expectations of fathers at all. In the space of perhaps two or three generations we have gone from the idea that a father should only have to provide for a child’s upkeep (and not slap them around too much) to a very immediate understanding of dadhood as a central plank of parenthood.

Perhaps a lot of this speaks more to my own insecurities than it does to anyone else’s. Still, I feel like there’s an easy camaraderie between mothers that isn’t apparent between fathers. My wife has developed a little circle of local mums with whom she’s in constant communication, whereas the WhatsApp group we created for the fathers in our NCT group has languished in silence. I don’t really have anyone with whom to compare notes. And what would we say if I did?

The pandemic has put us in an unusual situation. Ordinarily I would have had two weeks’ paid paternity leave, plus any holiday time taken alongside that. So I took three weeks off work — but I’m still working from home every day, as I have been since March 2020. This means that instead of watching me disappear to work five days a week, my son has spent every day of his life together so far with both his parents. I don’t even know where to begin with writing about the way this has changed us; perhaps I won’t know how to talk about it until it comes to an end.

It does mean that parenting feels like it has consumed my life in ways that might not have otherwise been the case. Being at home for so long with a new baby was a remarkable opportunity, and in the early days — through winter and the Christmas lockdown — it didn’t feel like I was missing out on much. Things are a little different now. Every absence independent from my family feels like it requires a negotiation as much with myself as with anyone else. And I don’t only mean literal absences. Someone new has come into my life and they have no tolerance for anything else that might be meaningful to me. So many of the things against which I used to define myself have necessarily had to be neglected.

It goes without saying that I haven’t written much. Whatever free time I have at the moment is normally spent collapsed in an exhausted heap on the sofa, watching TV. I can count the number of books I’ve actually finished in the last eight months on one hand; I have started and set aside perhaps two dozen. I feel very remote from the person who spent several years documenting here every book he finished.

Games have fared a little better. In the early days, when I found myself with some late night hours to myself, I picked up the remastered Bioshock collection. It took me months, but I eventually finished all three: the first game is a masterpiece, the second is a very decent sequel, and the third is probably the greatest missed opportunity in all of gaming. (I ended up writing several thousands of words about the games, over the course of weeks — the only thing of substance I’ve written since Robin was born, in fact — which I since abandoned, in a fit of self-doubt and impatience with my own tortuous style.)

But I mean it when I say that the first game is a masterpiece. I had forgotten just how immensely absorbing it is — a journey into another world that’s less realistic than it is gloriously theatrical. Every time I think about it I feel like I want to replay it again. And it never really occurred to me before that Bioshock is about parenting as much as it is a picture of Objectivism in decay. It hits different now, as the kids say.

While driving over the weekend I passed the word ‘DADDY’ outlined in rich pink flowers, laid in memorial at the centre of a roundabout. It made me flinch. Every time I see that word in whatever context it seems to come with an intimation of departure. And in the same way every time I think about this game it seems laden with the feeling of a dying fall that nobody ever really seems to talk about. You play as a kind of genetically modified clone, returning home to his unwelcoming father and near-absent mother in a demented inversion of the Odysseus tale; and the only good you can do in this world is to rescue the handful of innocents left within it. You have to become a father yourself, in a sense. But your days are numbered.

The ending of the original Bioshock is often written off as a bit of a joke. You fight a deliriously incongruous final boss, and then depending on your actions through the rest of the game, you get to see one of two final sequences. In the bad ending, the denizens of Rapture somehow steal a nuclear submarine, and it’s implied that something very bad follows. But the good ending has more to it than that. You return to the surface, and it’s implied that you adopt some of the Little Sisters you rescued down there as though they were your daughters. There’s a brief montage of scenes from an assortment of lives. A graduation. A marriage. A child reaching for a parent’s hand. And then a death bed. The hands of your daughters reach out for you one last time.

After perhaps twenty hours of gameplay this sequence is perhaps less than a minute long. It feels rushed, awkward, sentimental. But as a coda, it also has the outstanding benefit of being perfectly real.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

bb

How to describe the experience of expecting a first child in 2020? In some ways the pandemic made no difference at all. Most of the time we have been at home, waiting for things to happen, and that would have happened anyway. In terms of health we have both been quite lucky to have had no immediate concerns or difficulties, but what should have been routine visits to the GP and hospital became slightly more complicated. Our local doctors in particular seemed entirely inert — almost all appointments were over the telephone — and on the one occasion my wife arrived on time for a scheduled meeting with a doctor, it turned out that they’d booked it on the wrong day, and the GP in question was at home. Not ideal.

The staff at the hospital were better. I count myself lucky in that I was allowed to all of the ultrasound scans except the first, though for some reason this didn’t extend to any other appointments. Otherwise my experience with hospital so far has been limited, and strange. Mostly I’m just waiting in the public areas outside the maternity ward, listening to my headphones, waiting for something to happen. And that’s fine, and to an extent I understand why it needs to happen. The hospital itself is not even especially scary. The first time I went there I imagined it would be in some sort of state of perpetual emergency, but in the lobbies and halls everything happens mostly as normal. Only everyone is wearing masks.

The first thing I have come to understand about being a father in waiting is that expectations of you are very low. What exactly was required from me from the health service, or from my employer, or from anyone else outside my household? Very little. Next to nothing. I’ve had no appointments with anyone. My employer signed off on my paternity leave with no fuss, plus a little extra time from my holiday allowance. The midwives asked me nothing, and I asked them nothing, because usually I wasn’t in the room. Only sometimes I was a quiet presence behind a mask in the ultrasound appointments. None of this was very difficult.

There is still so much scrutiny afforded to the mother’s role. In theory, society expects more from fathers than it ever has in the past – which is good – but in practice nobody seems to have very much to say to them about it. In our antenatal classes (conducted exclusively over Zoom) the focus of every presentation and every discussion was on the mother’s experiences during pregnancy, labour, and afterwards. Everyone who attended my classes came as a couple, but the only mentions of the partner’s role were in the context of how they could assist the mother. Bring snacks to the labour room; remind her to go to the bathroom; figure out the best route to drive to the hospital. All of which is fine! But that’s all it was.

I am trying to avoid the suggestion that it should all be about me. I appreciate that antenatal classes have a practical purpose — they aren’t group therapy. But all this fed into the sense I already had that the expectations of me were so low as to be almost non-existent. Nobody asked how having a child would make me feel. Nobody wanted to talk to me about it. A thought occurred to me from time to time: I could be anyone! In the eyes of the world, I could be any kind of father at all, and nobody would ever know! Except me.

Managing this feeling is a strange sort of juggling act. In most aspects of life I would be happy to accept these diminished expectations as relieving a certain amount of pressure. But in the context of expecting a child, it leads to a corollary: nobody wants to know what you think about being a dad, therefore it doesn’t matter how you feel about it. I am sure that isn’t true. But it doesn’t always feel that way. The world seems to want a lot from fathers but at the same time it expects almost nothing at all, and certainly not in the same way it expects from mothers.

Recently I was reading samples on the Kindle ebook store for books aimed at new fathers. Almost everything I could find was entirely useless. Most of them are written in a kind of ‘strap in, bucko’ style that insistently reminds the reader of their responsibilities at every juncture, in the most patronising voice possible. Again: I get it. It feels churlish to complain too much about this kind of thing. I understand that these books have a purpose, and I’m sure they have an appreciative audience. But they told me next to nothing about what it would feel like for a new father to understand that they were going to have a kid, and what it would feel like for that kid to arrive, and what it would feel like to have to look after that new presence in a person’s life. I don’t know if these questions are too big or too small to be worth an author bothering with.

Popular culture is weird for models of fatherhood. I hate the term ‘beta male’, but TV and film is preoccupied with images of sidelined men who fit that trope. We’ve been watching a Canadian sitcom on Netflix called Workin’ Moms, which is enjoyable, if a little one-note — the basis of most of its jokes is that the mothers of the show behave just as badly as fathers used to in terms of philandering, over-focusing on their careers, and neglecting their children, whereas the fathers are relegated to keeping the boring practicalities of family life ticking along in the background. It’s fun, but – well, there are many other shows like this.

Elsewhere I stumbled on some useful stuff. Some of it is slight. I love the ridiculous baby in a bottle in Death Stranding, though I’m at a loss to explain what it means beyond being an unexpectedly tender portrait of babyhood in one of the strangest video games ever made. In The Last of Us: Part II I liked the short sequences late in the game where Ellie is carrying a gurgling potato-shaped baby around a quiet farmhouse; that, plus her subsequent panic attack in the barn, seemed relatable. (Ellie is absolutely the dad of that particular story.)

Recently I found myself listening repeatedly to Spalding Gray’s monologue It’s a Slippery Slope, where he talks variously about learning to ski and learning to become a father for the first time at the age of 52. It is oddly calming, not least as a reminder that there is no entirely right way to go about these things. Gray’s example is certainly not ideal — his first child came as a result of cheating on his long-term partner, and he’s frank about his initial wish that she not keep it at first. But it’s still kind of beautiful, and one of his more optimistic efforts.

A couple of weeks ago we happened to be watching the movie Parenthood. It is a gentle and straightforward Ron Howard movie, but no movie with Steve Martin was ever wholly unlikeable; and more to the point, it feels like an earnest portrait of a dad who is neither entirely feckless nor a figure of distant grace like Mufasa in The Lion King. There’s a line in it where Martin’s character snaps at his wife: ‘Women have choices. Men have responsibilities.’ Encountered today it sounds kind of MRAish, though the film goes to some lengths to undermine the logic of this (“Well, I choose you to have the baby” is his wife’s rejoinder); at any rate, the point is that when you’re in the middle of this stuff it doesn’t feel like you have any choices. There is probably something in this. But the point of the movie is that insisting on personal ‘choice’ as a measure of anything worthwhile is at best inconsequential, at worst destructive. Nothing that ever really mattered in life happened because you chose it.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

a beginner’s guide

I have been neglecting this blog in recent months. My last post was written in fits and starts over many, many weeks. I’ve been preoccupied with other things and, like many people right now, my productivity has ebbed and flowed. I haven’t stopped writing, and I certainly haven’t forgotten about this blog, but I confess that I’ve slightly given up on writing so comprehensively about every book I finish. Most of my time and energy in writing has gone towards trying to write a book about video games. (The subject is a bit more specific than that, but I don’t want to give the thing away just yet.)

This is something I always thought I could do. I have been playing computer and video games since I was able to do anything at all. I have a lot of ideas on the subject. But it’s also quite difficult, not least because I never thought I wanted to write non-fiction. In fiction you can more or less do whatever you want, but in this other thing the problem of imposter syndrome sometimes seems (to me at least) to be overwhelming. How much do I need to cite? At what point does a generalisation become intolerable? Am I supposed to anticipate every potential objection or counter-argument in advance? Is my authority worth anything at all? Is it worth trusting my own experience, or is it all just, like, my opinion?

Of course in asking all these questions I forget that I’ve spent years pottering around on this blog, actually doing all the non-fiction writing I am supposedly so worried about. But I still feel like I’m trying to un-learn all the habits of supposedly serious writing that I learned at university. I studied English Literature, which teaches a mode of formal discourse that is useful now only in the abstract, and mostly quite worthless in terms of creating something worthwhile outside of academia. The problem is basically one of tone. It’s one of what kind of book am I trying to write.

I know what it’s not. It is not a history of games, and it isn’t an academic treatise. There might be a thesis, but it’s not a TED talk. I want it to describe what it feels like to encounter and experience games. I don’t want to try to second-guess player motivation from a distance, and I don’t want to study game design in the abstract, as if it were secretly the most interesting part of games. Above all I don’t want to fight battles on behalf of an imagined movement. There is no shortage of books arguing that games are (or aren’t) worthwhile, either as art or as tools for productivity or creativity or brain longevity or mental health. Some of these are quite good. But it seems to me like the arguments for the quality of games are omnipresent and overwhelming for anyone who cares to look.

It’s strange, though, that ‘books about games’ are relatively rare. I know that there popular works of non-fiction on this topic, but I’m being a bit more specific: I mean this in the sense of ‘books about particular games’, and ‘books that take a thematic approach to what games do and how’. There are some interesting exceptions: You Died: The Dark Souls Companion by Keza McDonald and Jason Killingsworth comes to mind. There’s also the Boss Fight Books range of short-ish texts that typically focus on an author’s experience with a single game. But for the most part, books about games either fall into one of a few categories. You might get a general record of an author’s life in gaming that argues for the experiential benefits of games; or you might get a semi-academic thesis about games, often supported by evidence from psychological or sociological studies; or you might get a potted history of game development. Or some combination of the above.

Which is fine. Some of these books are very good. But there aren’t many books of cultural criticism applied to games. Take the question of violence in video games: there are plenty of books which argue the case one way or the other about whether this is ‘harmful’ or not. It’s much harder to find books that forego this angle in favour of taking a long, hard look at the games themselves; that consider what it really means for a game to be called ‘violent’ in the first place, or why violent games can be satisfying and horrifying and amusing all at once. Too often what it feels like to play violent games becomes immediately subordinate to the question of what these games are supposedly doing to our brains, to our sensibilities, and to our sense of right and wrong – as if players weren’t aware of this in the first place – as if the effects of any work of art could only be considered by judging how people behave around it.

Games are often portrayed as a sort of inscrutable ethical problem for modern society, as if they weren’t the product of human imagination at all. Often an accessible book about games will come loaded with disclaimers and framing devices intended to put the reader at ease, to reassure them that what they’re about to encounter won’t hurt them. It feels like there aren’t many books which try to take us inside specific games, to show us how they work, and to make the reader feel how they make the player feel.

And that’s odd, in a way, because this kind of game criticism is omnipresent online. In the weeks after a major release, every gaming website will have a whole buffet of hot takes available. People are keen to produce stuff to support their favourite titles, sometimes for years afterwards. To pick a random example, the Mass Effect games are still enormously popular, and have spawned all kinds of novelisations and comic book spin-offs. Doubtless you can still find hundreds of thousands of words of opinion out there about why those games are good. But I don’t think anyone has written a book about Mass Effect.

You could argue that this is not especially unusual. Any of the following arguments could apply:

cultural criticism is best left to specialist magazines and journals

people who play video games do not (for the most part) read a lot of books

people who don’t play video games don’t want to read about games

people in general don’t want to read books about media which they aren’t likely to experience themselves.

There is a sense in which the most successful games of this sort belong to the fans foremost. The culture that grows up around big games is fan culture. Movies have something of the same thing — especially since the Marvel and Star Wars movies exploded in popularity again — but that’s only one wing of the superstructure that is film culture. There are whole other wings dedicated to serious cinematic avant garde, to art films; you could spend a lifetime studying Hong Kong cinema and barely know a thing about Bollywood, and vice versa. Which is fine because film caters for taste at all levels. There are popular film magazines and blogs, serious journals about film, and occasionally works of critique that bust through into the mainstream: I’m thinking of stuff like Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s De Palma, about the director of the same name; and Room 237, about some of the more outlandish theories that have grown up around Kubrick’s film of The Shining.

Granted, those examples were only moderately successful. They’re semi-popular but not exactly mainstream. But my point is that it’s inconceivable for me to imagine something similar coming out of the video game community. Whether it’s Ready Player One or the latest Netflix documentary High Score, games are stuck retelling their own histories from scratch each time. Which is not to say that new and fascinating stories can’t be brought to light — but so often games media aimed at a general audience begins with a long, laborious retread of game history.

There is very good, very specific stuff out there, but it’s hard to find. Video games are very good at reaching people who already play games. Many game critics are good at the same thing. But neither are very good at bringing the most interesting aspects of games to people who have no prior interest. The Beginner’s Guide is one of my favourite games of all time, and I think it’s one of the finest ‘games about games’ ever made; but so much of it is ‘inside baseball’ of the kind which would be incredibly difficult to explain for someone not already steeped in it. YouTube is increasingly a great source for insightful video essays about games that go far beyond ‘hot take’ culture, but in a similar way, it’s kind of impossible for an audience to find any of this stuff if they’re not already out there searching for it.

Is there a way out of this? I don’t know. Maybe it’s worth a shot.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little while ago I wrote about Swimming to Cambodia, a copy of which I discovered in a charity shop. I read it and I liked it a lot. And then for a while I forgot about Spalding Gray until one day my wife pointed him out to me in the film Beaches. I think he played a doctor of some kind — I wasn’t really paying attention — but it was enough to get me thinking about his stuff again.

I started trawling YouTube for what I could find. Most of his stuff is out of print, but there at least you can find a few of the monologues — Terrors of Pleasure, Gray’s Anatomy and It’s a Slippery Slope are all delightful. The most interesting primer is Steven Soderbergh’s documentary And Everything is Going Fine, which is assembled entirely from excerpts from Gray’s monologues and interviews. It’s a deft, skilful, and beautifully elegiac piece of work which feels more like one great final performance than it does a conventional biography. Appropriate, perhaps, given that so much of what Gray did was rendering up his life through storytelling.

I also bought a couple of books: Impossible Vacation, which is the only novel Gray published, and the posthumous collection of extracts from his journals. Apparently he laboured for years over the text of Impossible Vacation, with the original draft running to over a thousand pages — the monologue Monster in a Box was actually performed with the manuscript sitting in a scruffy cardboard box at his elbow. The final published form of Impossible Vacation is a relatively svelte few hundred pages in paperback, which is enough to make anyone wonder about the scale of the original.

I was expecting Impossible Vacation to be a bit more novel-like. I was expecting a modern American comic story along the lines of A Confederacy of Dunces, perhaps. But in fact, the novel is a lightly fictionalised version of Gray’s own life. And that’s about as ‘light’ as it gets: it’s funny, but it’s also just as self-involved as any of his monologues. Gray’s protagonist is renamed Brewster North, but not much detective work is required to map North to the author. Much of the novel is mirrored elsewhere in Gray’s stories from the stage: the trip to India, his brief stint as an actor in pornographic movies, the experimental theatre scene in New York; and above all the memory of his mother, and the lasting effects of her suicide.

If you read (and watch) far enough into Gray’s work it feels a little like wandering into a hall of mirrors: we see the same selves and preoccupations reflected over and over again, sometimes in distorted or disturbing ways. Glimpsed in passing the effect is comic, but after a while the effect becomes haunting. There is a moment in Gray’s Anatomy where he describes watching a student in a storytelling workshop, and staring into her eyes, and watching her face somehow disintegrate until the flesh falls from her skull and her face becomes a sort of ball of white light. Sometimes that’s what reading his stories feels like: the contortions of history and storytelling are subject to a relentless focus that becomes so intense that the reader is lulled into a sort of hypnotic compliance.

This feeling of falling into a sort of dissociative trance is not uncommon in his work; it seems emblematic of a sort of transcendental feeling that Gray was perpetually striving for. Hence the dream of the ‘perfect moment’ in Swimming to Cambodia, hence escapism via skiing in It’s a Slippery Slope. Set against that dream of escape is everything the real world has to offer: the anguish of the domestic; the problems caused by anxiety, depression, drinking; the sad, strange, tortuous complications of his love life. In these respects, it hasn’t aged well – I can imagine audiences today having a little less patience for Gray’s occasional sways into mysticism. And his attitude towards women might at times be generously described as ‘problematic’. In the 90s perhaps it was easier to dismiss his casual reports of philandering as the trappings of the tortured artist; today it only seems sad, and a little wearying.

So why is it that I find his stuff so appealing? I’m not in the habit of reading biography. I like podcasts, but while Gray seems like a model for all kinds of modern tendencies in vlogging, I’m not aware of anyone who is doing exactly what he did in the same way he did it. Current trends towards the confessional in stand-up comedy don’t quite fit, either. The form of the thing is so important. He was as much a performer as he was a storyteller. The closest equivalent that I know of is David Sedaris, and I find his stuff intolerable. There are a few reasons for this, but to me Sedaris always seems convinced that the problem is with other people. He is stuck in a mode of perpetual disdain. But with Gray, we are never really left in any doubt that this author is in fact the only author of his own troubles. And yet he also knows how to have fun, sometimes; and I find that endearing because it seems to me more honest, and less spiteful.

One point of comparison is Proust. I don’t mean to say Gray’s prose is exactly Proustian, but they have an endearing amount in common. There’s a perpetual anxiety about death and entropy that often manifests itself as hypochondria. There’s the obsession with the mother, the retiring nature, the preoccupation with irony. The pursuit of the perfect moment through which emotion can become recollected in tranquility. And though both took to entirely different forms of media, it seems like both were attempting something a level of formal innovation which, while initially seeming familiar, approached a new way of committing memory and experience into art.

Impossible Vacation is often intense but it’s not always laugh-out-loud funny. More often it seems possessed by a restless, struggling, enquiring energy. Sometimes the writing is inspired, but it lacks form – the feeling of form that was so dominant in the monologues themselves. As it stands, you wouldn’t consider half of the things that go on in the book as the plot for a novel because (like life) they don’t entirely cohere. And the story ends before it ever really begins, though it does at least contrive a neat circular ending that recalls (lightly) Finnegans Wake.

Still, it’s a shame that the novel is out of print because, much like his monologues, it’s certainly worthwhile; the published journals of Spalding Gray are an entirely different and more difficult thing. The journals are kind of a mess. An enormous amount of biographical heavy lifting is provided by the notes and annotations by the editor, Nell Casey, and without this context any reader would struggle to discern what was going on. But the notes are pretty comprehensive, and in the end this seems as close to a biography as we are ever likely to get. It does, however, take a long time to get going. The journal entries all through the 70s and early 80s are sketchy, and not especially interesting. A lot of the time they’re purely expressive, and we have to be told what it is exactly that they are referring to. It’s only once the monologues get going that his private style becomes elaborate and involved enough to be worth reading.

The picture we get of Gray is less of a single-minded auteur and more of a man who sort of wandered-or-fell into fame as a monologuist. After the fame and exposure of Swimming to Cambodia there is a sense of freewheeling — of doing what he’s doing because it’s what he does, and it’s rarely entirely under his own steam. He is perpetually worried, questioning, uncomfortable. Eventually he would become concerned with the idea that he had used himself up, and that he had no private life worth living outside the performances. But some of this was ameliorated by the late in life arrival of children and a more settled family situation. For a while, he thought himself happier than he had ever been.

In 2001, Gray was involved in a terrible car crash while on holiday in Ireland. His injuries included a broken hip and a fractured skull that likely caused brain damage. The accident changed his life, and afterwards he was never the same. The journal entries from after this point are harrowing — there is no other word for it. I knew of his eventual suicide, but I had no idea until of the extent to which depression utterly consumed his life. I didn’t know about the frequent hospitalisations, the shock treatment, and the pain his failed suicide attempts caused on others. There aren’t many extracts from this time shown, but what we are given was enough at times to make me wonder if any of it should have been published at all. But perhaps there is a purpose in trying to give a picture of the anguish he was in.

All through his life Gray had been preoccupied with the idea of his mother taking her own life. The story he told about this was that this was precipitated by his parents moving house, to a new place away from the ocean, which his mother could never feel at home in. After the accident he and his family also moved house, and he came to regret this decision intensely. The editor Nell Casey calls this ‘his obsession, a mythic rant’. Gray cannot seem to accept the idea that a house might be, as a psychologist puts it, ‘a pile of sticks’. Here is how Gray considers trying to explain it to his sons:

‘…And they said, I’m sure, that, you know, Mrs. Gray—my mom—has other problems about the house, it must be symbolic of something, that same old Freudian rap, you know, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, sometimes a house is just a house. She missed the house. It wasn’t symbolic of something, she really missed walking along the sea. I miss walking in the village, I miss the cemetery, I miss hundreds of things. But boys, listen: when you get to that point, where you have been driven so crazy by something, like for me, when I think about the house, it’s not me thinking about it, it’s thinking me…’

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the red telephone

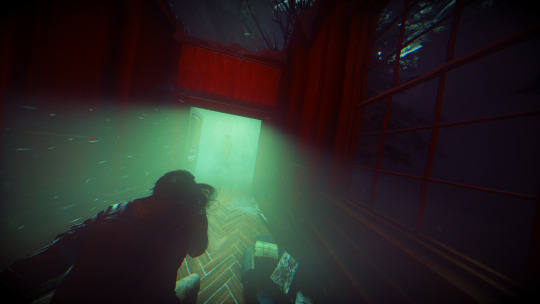

The thing about Control is that I don’t think I’ve ever played a game where I’ve felt such a vast difference between a game’s artistic and technical quality and its total lack of thematic and narrative depth.

There is a good case for saying that this oughtn’t to be a problem. It’s long been the case that if a video game is entertaining enough, any further ‘depth’ (by the standards established by other media) is unnecessary. This is why we don’t much care if the story isn’t good in Doom. The sense of being there and doing the thing is enough. But Doom isn’t drawing on influences bigger than itself. Clearly it’s been influenced by a variety of things — from Dungeons and Dragons to heavy metal album covers and Evil Dead and everything in between — but Doom is not referential, and it’s not reverential. Doom is complete unto itself. Control is not complete.

Horror films and ghost stories and weird fiction are best when they are about things. Think about The Turn of the Screw and The Thing and Twin Peaks and Candyman, to pick a few examples off the top of my head. They work not just because what we see and hear and read is mysterious. They are compelling because they have intriguing characters and thematic resonance. The Babadook is not just a story about a monster from a book for children. Night of the Living Dead isn’t just about, you know, the living dead. By comparison I find it hard to say that Control is about anything, but it presents itself as adjacent to this kind of work. It is a magnificent exercise in style which trades in empty symbols. It wraps itself in tropes from weird fiction in the hope of absorbing meaning by osmosis.

It feels like a wasted opportunity, because the setup is not without interest. You play as Jesse Faden, a woman supposedly beginning her first day on the job at the Federal Bureau of Control, a mysterious government organisation that deals in high-level paranormal affairs. The FBC is a feast of architectural and environmental detail: a vast Brutalist office complex with an interior that seems to be stranded in time somewhere around the mid-1980s. Everything is concrete and glass and reel-to-reel machines and terminal workstations. It’s frequently stunning.

Unfortunately most of the staff are missing because Jesse’s visit to their headquarters coincides with a massive invasion by the Hiss, a paranormal force which has taken over the building. The Hiss is a sort of ambient infection that turns people into mindless spirit-drones, chanting in an endless Babel. (Conveniently, most of those drones are present as angry men with guns. There are also zombies, and flying zombies, for variety.)

There is, obviously, more to Jesse than meets the eye. She spends a lot of time talking to someone nobody else can see. But there isn’t that much more to her. Like every other character in the game she is a monotone. There is no reason to believe she has any existence outside the plot devised for her here. Similarly, the other characters you meet exist only as the lines they speak to you. It works only when the effect is entirely, deliberately flat: the most compelling person in the game is Ahti, the janitor with a sing-song voice and a near-indecipherable Finnish accent. He is nothing but what he is — he has no past, no future. He has all the answers, if only you knew what questions to ask.

Control is undeniably stylish. The interiors are striking, vast, spacious. Even on the smallest scale the game has a great eye for little comic interactions via systemised physics. You can shoot individual holes in a boardroom table and watch the thing splinter apart into individual fragments. You can shoot a rolodex and watch all the little cards whirl around in a spiral. If a projector is showing a film you can pick the whole thing up and the film will reveal itself as an actual dynamic projection by spiralling and spinning madly across the nearest walls. (Speaking of film, the video sequences with live actors are great fun, and this being a Remedy game, there’s a fantastic show-within-a-show to be found on hidden monitors around the FBC.) And all of this before I mention the sound design — the music, which is full of concrète mechanical shrieks and groans — and the endless sinister chanting which fills the lofty corridors and hallways of this place, The Oldest House.

All of this is very, very good. And most of the time it’s quite fun to play. I mean, you can pick up a photocopier and fling it at enemies. It’s never not fun when almost anything can be used as a projectile. And then you get the ability to fly! At its best the combat in Control feels messy and chaotic — in a good way — but in a way that has little to do with typical video game gunplay. Staying behind cover doesn’t work because the only way to regain health is to pick up little nuggets dropped by fallen enemies, so most of the time you have to use your powers to be incredibly aggressive. The result is that often you feel like the end-of-level boss — a kind of monster — throwing yourself into conflict with a team of moderately stupid players who think they’re supposed to be playing a cover shooter circa 2005.

That you are given a gun at all seems odd. The gun feels like a compromise. The gimmick of a single modular pistol that can shape-change into a handful of other weapons is neat, but those weapons are just uninteresting variations on the same old themes: handgun, shotgun, machine gun, sniper, rocket launcher. The powers are more interesting and powerful. But of course the gun has to be there; can you imagine them having to go out and sell this game without a gun in it? What would Jesse be holding on the front cover?

A gun is an equaliser. It evens the odds between the weak and the strong. But if you’re already strong it doesn’t feel worthwhile. You’re clearly so much more powerful than everyone else you meet in Control that after a while you begin to wonder why the game is also frequently quite hard. The omission of any difficulty settings is notable in a game of this type; it suggests that the developers were committed to their vision in the way that might recall Dark Souls. In fact the hub-like structure of the game is pretty clearly influenced by From Software’s games, and though it’s nowhere near as challenging, it seems to be reaching towards the same kind of thing.

It’s a game which demands you take it seriously as a crafted object. But then it has all these other elements cribbed from elsewhere — the generic level-based enemies with numbers that fly off them when shot, and the light peppering of timed/semi-randomised side activities, both of which made me think of Destiny. So there’s games-as-service stuff wedged in here too, and it doesn’t sit at all comfortably with this supposedly mysterious, compelling world that you’re supposed to want to explore.

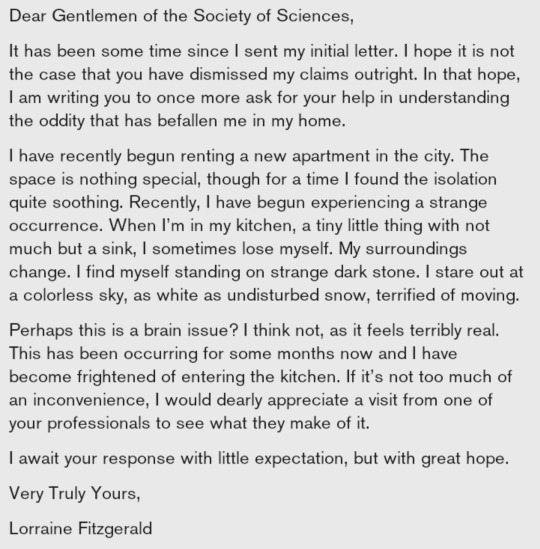

This isn’t a horror game. There are one or two enemies with the potential to induce jump scares, but given that you can always respond with overwhelming force, it’s never really unsettling. But it’s clearly been inspired by horror. A source often mentioned as an inspiration for Control is the internet horror stories associated with the SCP Foundation wiki. From there the game borrows the idea that unlikely everyday objects can become sources of immense cosmic power — hence we see items like a rubber duck, a refrigerator, a pink flamingo, a coffee thermos imprisoned behind glass as if they were Hannibal Lecter. A pull-cord light switch becomes an inter-dimensional portal to an otherworldly motel. The great part about this is that these little stories can be told effectively in isolation; it’s always interesting to come across another object in the game and to discover what it does. (The fridge is especially unpleasant.)

But experiencing this kind of thing in the context of an action game is entirely different to stumbling it on it online. SCP Foundation is pretty well established now, but still, there’s a certain thrill in stumbling across something written there in plain text, titled with only a number. When those stories are good, they can be really good. Given the relative lack of context, and the absence of any graphical set-dressing, there’s room for your imagination to do the heavy lifting.

In Control these fine little stories are competing for attention with all the other crazy colourful stuff going on in the background. You read a note and you move on to the next thing. You crash through a pack of enemies and the numbers fly off them. There’s never a sense of the little story fitting into an overall pattern. That lack of a pattern can be forgiven in the context of a wiki. In Control, these stories start to feel irrelevant when you never come across an enemy you can’t shoot in the face. In a different format, or a different type of game, this kind of rootless narrative might be more compelling.

But what is this game about? There’s a sister and brother. A sinister government agency. Memories, nostalgia. A slide projector. It’s all so difficult to summarise. When I think about the game all these words seem to float around in my head, loosely linked, but not in a way that suggests any kind of coherence. The game always seems to be reaching towards some kind of meaning but it only ever feels hollow. It feels flat. Yet all the elements that are good about Control must be made to refer back to these hollow, flat signifiers. Sometimes the flatness works for the game, but mostly it doesn’t.

Today, it’s hard to see that anyone could see the point in establishing a website like SCP Foundation if it didn’t already exist. Viral media is not what it was in the first decade of the 2000s. Written posts that circulate on social media have a shorter half-life than ever. It’s almost impossible for any piece of writing over a few hundreds words to go viral in ways that go beyond labels like ‘shocking’, ‘controversial’, ‘important’, etc. ‘Haunting’ and ‘uncanny’ don’t quite cut it. This kind of thing doesn’t edge into public spaces in the way it used to via email inboxes, or message boards, or blogs.

Perhaps the weird stuff is still out there. Perhaps we only got better at blocking it out. With the arrival of any new viral content, today’s audience is mostly consumed by questions of authenticity, moral quality, and accuracy. If you think this creepy story might be ‘real’, you’re a mug. If you promote it you might be a dangerous kind of idiot. And that’s fair: there are a lot of dangerous idiots out there. Yet there’s something to be said for an attitude of persistent acceptance when it comes to the consumption of weird stuff on the internet. I know I become gluttonous when I come upon such things. I want to say: yes, it’s all true, every word. I’ve always known it’s all true.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

the big light

The Mirror and the Light has been in the works for a long time. I read Wolf Hall shortly after its release in 2009, and loved it. Same with Bring up the Bodies in 2012. Two years after that my wife and I went to see Hilary Mantel read from The Mirror and the Light at the South Bank Centre. Back then it must have seemed like the release wasn’t too far away; had someone told me then that we wouldn’t see it till 2020 I would have thought them unhinged.

It’s long — well over 700 pages. At first glance the length might seem surprising because this is not (for want of a better term) the sexiest part of Henry VIII’s rule. The story is one of those notorious miscalculations of history: after the death of Jane Seymour, who is often thought Henry’s most beloved wife, a marriage is arranged between him and Anna of Cleves. She is a woman from a distant German state who Henry has never met; the union is essentially one of convenience, because England’s international situation has rarely been more complicated.

Following the reformation, England has been excommunicated by the Catholic church. In theory, both the nation and its ruler are fair game for invasion or murder by any loyal Christian nation. In practice, the uneasy relationship between the rulers of France, Italy and the Holy Roman Empire makes that far from straightforward, but the risk seems real all the same. Cromwell faces further trouble at home — riots and uprisings are becoming more of a problem, motivated in part by deep local affections for the old religion. Thomas is the most powerful he has ever been but he’s still surrounded by enemies, especially amongst the old families of England, who have never allowed him to forget his humble origins.

It may seem as though there’s a lot going on, but by the end of the novel I felt like there wasn’t enough to justify the sheer weight of paper in my lap. This is not to say the writing isn’t good. It is often great. But this is a novel light on surprises. I enjoyed reading it all the same – it’s enough for me to be carried along by Mantel’s authorial presence, which still feels absolute and omnipresent. Cromwell’s personality in these novels is one of the most compelling characters in fiction. Yet there’s very little in The Mirror and The Light which we haven’t encountered before in the two previous novels. The same scenes from his life come again and again — the death of his wife and children in Wolf Hall, and those endless scenes with Anne in Bring Up the Bodies. The same lines become like motifs: arrange your face, so now get up, and so on. Perhaps the problem with a novel where you see everything is that after a while you start to feel like you’ve seen everything.

We feel there isn’t much that is new to discover about Cromwell. There are a few exceptions; the rumours that grow up around Cromwell regarding prospective new marriages are not without interest. But I found little here which sticks in the mind like the scenes from the earlier books, and part of the problem is the whole concept of ‘scenes’ as they exist here.

The preceding novels have now had at least two major adaptations — one for the West End stage, and one for TV. I saw both, and they were good, solid, conventional. A cynical reader might declare that too much of The Mirror and the Light feels like it’s been written with dramatic adaptation in mind. At times it seems less like a novel and more like notes towards a screenplay. There are endless conversations which seem intended to be tense, dramatic confrontations, but which never seem to advance or demonstrate anything.

And yet as soon as the novel switches back into the interior mode, you almost want to forgive it everything. Being in Cromwell’s room is like working your way through a series of rooms in a museum — full of detail and diversion — and it’s wonderful, except the novel keeps pulling you out of it like an excitable tour guide who can’t help but subject you to another conversation, another insignificant moment from history, another scene.

I feel like the previous novels weren’t like this. But I still feel like I’m too close to them to go back now. The best I can say of The Mirror and the Light is that it consolidates the vision of Cromwell as perhaps England’s greatest ever reformer and renaissance man. He wins the long game in the ways that matter: not only the break from Rome, but in the idea of the monarch and state as deserving respect entirely separate from any religious obligations. In these books Cromwell also seems to stand for something profound in the idea of the British idea of the self-made man. He plays to our love of the self-starter, the man who started out with empty pockets and a seemingly infinite set of talents, and who took on the establishment. He won, but in the sense that he lived long to see himself become the establishment, and to be swallowed by a machine he had built to catch others. (And there’s something additionally satisfying in this kind of downfall. We love to see a man build himself up, but we also love to see him torn down to size.)

In the end, there is something drab and faintly disappointing about Cromwell as he emerges here. All his work was not in service to anything greater than himself. The pursuit of humanistic knowledge, the service of his prince, and the consolidation of his own power — what was his legacy outside of this? Part of Mantel’s genius is to work that thread of disappointment through the text here; Thomas is constantly looking to his own legacy, worrying that he hasn’t done enough; he is preoccupied with his mistakes and things he could have done better, like the death of William Tyndale. In this way he emerges as a bit more human: he is someone who, like any of us, is worried about what he will leave behind.

And yet it’s hard to feel too sorry for him by the final pages. Our sympathy is limited in part because his success has been so outlandish, and in part because of his lack of anything resembling sympathy for the world around him. He is devoid of intimate, empathetic connections. Alms for the poor and the foundation of a few schools don’t quite cut it — philanthropy is only the rich man’s way of paying his debt to society on his own vastly skewed terms. His servant Christophe is his most intimate friend, perhaps because he reminds him most of himself as a young man. In the end it seems there is nobody else who will miss him.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

soft play

I was never much of a one for rock climbing. I have tried it a few times over the years, enough to know that while I’m not afraid of heights, the fear and discomfort and frustration that sets in while trying to balance on a tiny ledge some fifteen or twenty feet above the ground is too much for me. It’s not something I want to be doing.

As with much else, the climbing in Rise of the Tomb Raider is borrowed from the Uncharted games. They add a couple of mechanics for flavour, but not much. Once you’ve latched on to a surface you just move the stick in the right direction and Lara proceeds to execute all kinds of seamless acrobatic moves. There’s no skill, one might complain. But that’s fine with me, because I don’t like climbing.

I like the stuff that happens before and after the climbing. I like camping, I like hiking, I like exploring. And Rise of the Tomb Raider actually does that stuff quite well, in a very safe, very streamlined, very contained way. It gives you these big open areas to romp around — they’re supposed to be wild, dangerous places, but they are laid out more like huge soft play rooms. You scramble up slopes and slide down ravines and swing on ropes and splash through rapids and delve into secret caves, and it’s all just as satisfying as when you were diving into a big ball bit or sliding down a death slide or bouncing on a trampoline as a child.

The other stuff the game borrows from Uncharted feels a bit tedious. The mandatory plot-driven action sequences are a bit tedious, though the story itself is not totally without interest. There are far too many moments where it dumps you into a room (not even a big room!) full of angry guards and asks you to get on with it. This is like having to do your homework in between soft play. But when it slows down a bit afterwards, it’s a pleasure. The world is beautifully rendered, and it’s fun to romp around finding stuff and solving puzzles and sneaking around and collecting junk.

Here’s a thing: I don’t think I have ever played a game which pays so much attention to detail to depicting the protagonist as vulnerable. She is physically small and slight compared to everything and everyone else around her, and that’s refreshing, but so often Lara is shivering or gasping for breath or reaching out as if to steady herself. Sometimes the animations are charming: when you climb out of a pool of water, Lara will always take a moment to reach up and fix her ponytail again. That’s a nice, human touch. But there’s a fair amount of discomfort too.

This is worth mentioning not because it’s shocking, but because visible vulnerability is a rare occurrence in games of this type. Male protagonists in particular are rarely shown visibly suffering unless it’s a horror game, or things get really bad. It’s odd here because as a player you almost never feel disempowered, even while the game is showing you that Lara is cold or injured or exhausted. The game seems to be asking you to sort things out, but there’s no penalty for leaving her to shiver forever.

So why do it at all? In part it seems to be a stylistic hangover from the first rebooted Tomb Raider that came out back in 2013, a game which seemed partly inspired by survival horror films and the concept of the ‘final girl’. Lara begins that game a naive student; mid-way through she emerges reborn from a vast pool of gore; by the end of it she is machine-gunning bad guys with panache. Here, Lara is still at ease with thumping her ice axe into some dude’s skull, but the game consistently feels the need to emphasise her fragility.

In terms of violence, the dissonance in this kind of representation has been widely discussed. I have little to add to it; as a topic of discussion it seems exhausted, one to file alongside ‘lack of player agency’ and ‘lazy developers’ as exegetical dead-ends. But by the end of the game I was starting to wonder at what point that Lara would become the woman from the old games again. (These are, after all, prequels.) I don’t mean ‘when are they gonna put her in hot pants again’, obviously; her attire in this game is thankfully quite sensible by comparison. But there is something to be said for a video game protagonist who is confident, knowing, assertive; probably murderous, and fairly dubious in her intentions. Someone who can live up to the way they’re supposed to be behaving on screen.

You could argue that we had plenty of those characters already in video games, and most of them were rubbish. You’d be right. But by comparison it feels like here we’ve been issued with Lara as a stereotypical millennial: a young adult perpetually arrested in time, perpetually struggling, perpetually shivering. And while there’s nothing wrong with that sort of character in principle, it feels a bit insincere compared to the sort of game they’ve placed her in.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

the republic of heaven

Back in 2000 when The Amber Spyglass came out I feel like there was not so much news in the world. At the turn of the millennium we seemed to be entering a more optimistic time. Tony Blair was elected in 1997 at the head of a liberal Labour government, and while it may be true that Blair would never be so popular again as he was in the opening years of his premiership, the Tories seemed hopelessly outdated by comparison. They were still the nasty party of old, while the country was ambitious, outward-looking, internationalist. Explicit racism and homophobia were no longer tolerated. We were Europhiles, but we weren’t part of Europe. There seemed to be a lot of money about.

At home there were occasional horrors — the murder of Jill Dando, the homophobic pub bombings in London, Harold Shipman — but they were somehow isolated, disparate, inexplicable. They were exceptional. There was the war in Kosovo, which set a template for liberal interventionism in years to come. The economy was trucking along; unemployment was low; for the first time there was a national minimum wage. I skim the headlines today and it seems like such a comfortable time by comparison. Perhaps I am remembering it wrong. But when the years to come would bring a spiral of endless war, recession, and one of the most significant declines in relative generational living standards, I’m not sure there is any need for rose-coloured glasses.

Into this comes The Amber Spyglass, which is basically quite an optimistic anti-authoritarian novel. It was also the book which, for a handful of reasons, really brought Philip Pullman to the world’s attention. It was this which ensured that his name still lurks around the list of authors most frequently ‘banned’ in America, and which in the years after its publication would attract scores of avid cheerleaders and detractors. Inevitably most of those had no interest with engaging with the substance of the book itself. Instead, it became a sort of battleground: on one side, those convinced that religion was under attack from an educated elite; on the other, those who were committed to reducing the role of religion in public life, discourse, education, and so on. It is worth revisiting this typically excitable interview and profile by Christopher Hitchens for an example of how these novels were talked about.

To call the novel ‘optimistic’ might seem surprising, because much of it is shrouded in scenes of gloom and suffering. But when I think of the tone of the novel as a whole, it is pastoral. When the world isn’t tearing itself apart the language seems more lyrical than in either of the two preceding books. Some of that is to do with the perspective, which now has at least three (and sometimes more) main characters to follow. This means that a sense of distance, of floating high above the many worlds of the story, becomes necessary. But it’s also that the reader has a sense that this book is going to be about the promised war against the heavens outlined in The Subtle Knife, and it’s likely the reader will also understand that this is a war that must be won.