Text

Italienerin (Chiaruccia) mit Spinnrocken (and details) by Friedrich von Amerling (1803–1887)

1846, oil on canvas

388 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Dutch Girl at Breakfast (detail) by Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702-1789)

oil on canvas, c.1756

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Isabella by Simon Maris (1873-1935)

oil on canvas, ca. 1906

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

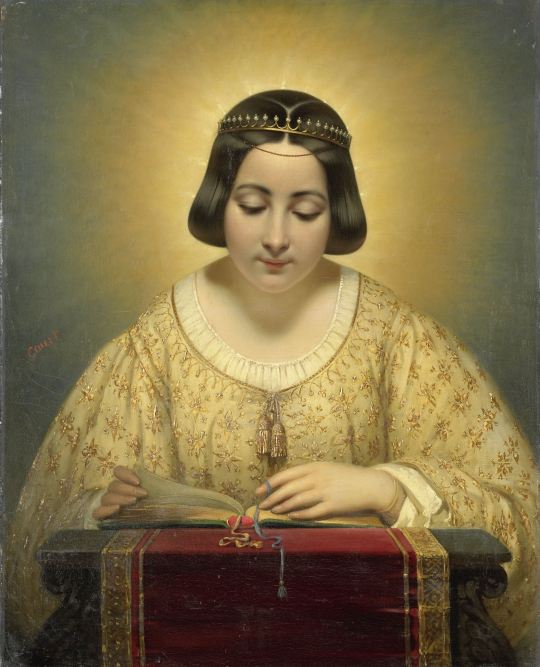

Countess de Pagès, née de Cornellan, as St Catherine by Joseph Désiré Court (1797-1865)

oil on canvas, ca. 1820-1850

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of Willem II (1626-1650), Prince of Orange, and his Wife Mary Stuart (1631-1660) (detail) by Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656)

oil on canvas, 1647

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Girl with Straw Hat by Friedrich von Amerling (1803-1887)

oil on canvas, 1835

300 notes

·

View notes

Photo

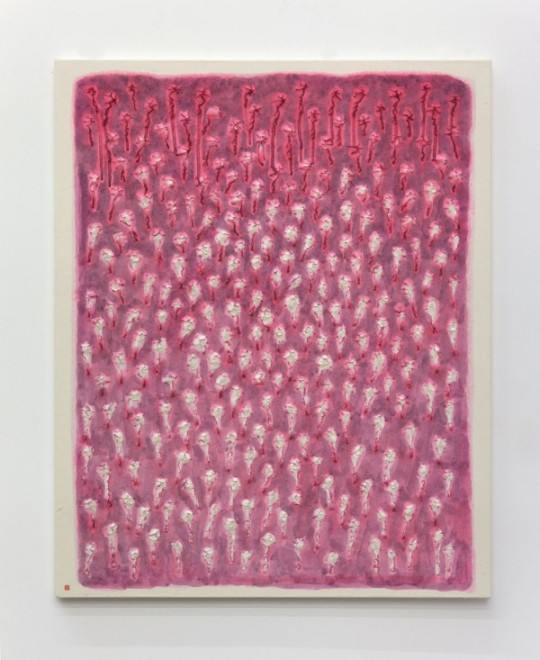

Untitled by Kwon Young Woo (1926-2013)

korean ink and paper, 1988

Kwon Young-Woo (권영우) was considered a pioneering figure in the development of Dansaekhwa (or the modern monochrome movement), a Korean painting tradition where artists work predominantly with paper.

Throughout his career, Kwon explored the textural abilities of his chosen medium by scratching, tearing, and layering sheets of hanji (traditional Korean mulberry paper) onto canvas and manipulating the material into three-dimensional relief sculptures which were then decorated with ink painting. Later in his career, Kwon removed any trace of representation and worked solely with white paper.

Kwon’s skill in altering a traditional material to reflect themes of Abstract Expressionism has led to him being recognised as one of Korea’s most groundbreaking artists. Recently, the artist’s works have been exposed to new audiences due to a resurgence in interest of the Dansaekhwa movement.

(source)

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

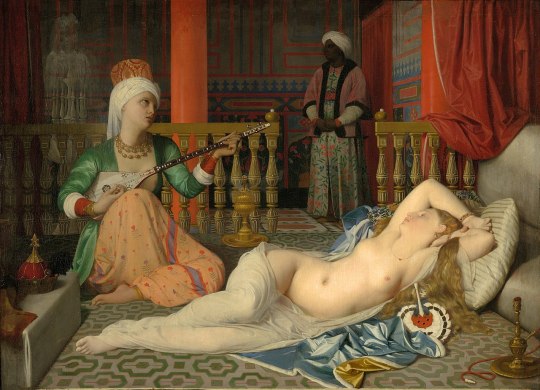

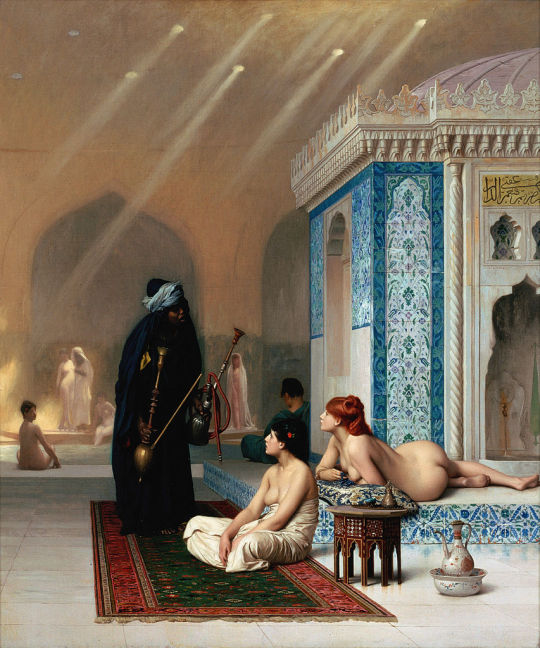

Odalisque with Slave, 1839, by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

Why Victorians Went Crazy for Orientalism

During the period of feverish obsession with Orientalism, European artists and art lovers looked towards what they dubbed the “East” - aka the “Orient.” The Victorians weren’t overly specific, as this region actually spans many distinct territories and cultures over the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia. They all did have one sure thing in common however, their “otherness.” They were decidedly different from European culture and while the obsession of the Orient has stretched quite far back in history (and I mean centuries before), we’re going to focus on how and why the Victorians in particular went crazy for it - particularly their obsession with the Ottoman Empire.

The idea of the “Orient” often sets the scene in one’s mind as slave markets, snake charmers, women either dressed in too much clothing or none at all, the hustle of markets and harems, as ‘Arabian Nights’ from Disney’s Aladdin plays in the background. These are just some of the stereotypes which continue to dominate much of the region(s) rich cultures and histories. Provocative, erotic, and exotic.

Power and Obsession

Society at this time held an appreciation of the complex architecture, but often little else, interested only in what the artists could portray as consumable to an audience - whether it was an accurate representation or not.

They largely pushed the view of East civilizations “otherness” through unrealistic portrayals of its people. Clearly all Arab men were snake charmers or slave traders, and all women were poor sexy slaves or… sexy slaves with slightly more luxurious lifestyles - “sexy slave babes” as Lindsay Ellis playfully coins in her video essay ‘The Most Whitewashed Character In Literary History.’ It largely represented these cultures stereotypes or fantasies from the Victorians outside perspectives.

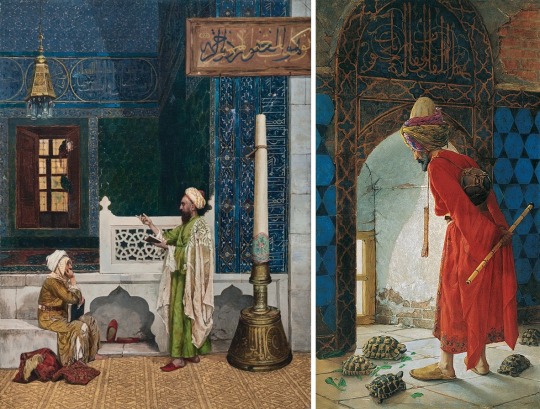

For example, look at the amazing care Osman Hamdi Bey, an artist actually born within the Ottoman Empire, took in portraying the architecture and lettering within ‘Reading the Quran,’ and ‘The Tortoise Trainer.’

While Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting ‘The Snake Charmer’ isn’t as grounded in reality.

These portrayals, which didn’t just occur in visual art but also frequently in literature and the World’s Fair, created a narrative in which the Western control of the East made them civilized and justifying that good ol’ colonial spirit.

Breaking the Nude Rules

Nudity was a big thing for the Victorians. Today we regard them as shrewds scared of showing their ankles, but they went nuts for scandal and drama. Traditionally in Victorian art, nudity had to hold a purpose in order to be deemed acceptable. This included requirements such as depicting mythological or allegorical figures. Then entered ‘Orientalism’ and with it an exception to the rule, where they could view as many naked sexy slave babes that they wanted! Orientalism was an exception to the Nude Rules within Victorian society, and Orientalist artists milked it. Depictions of harems within Victorian art could vary greatly, from some showing it as a more domestic space for women, to others dialed up the exotic and erotic to 100.

When seeing how the Harem was depicted in art by men in particular isn’t all that surprising, as it was the unrealistic portrayal of what was essentially the equivalent to an exotic form of an all-girls sleepover, equipped with nothing but pillows. In short, it was pure fantasy. This is largely due to the fact that men weren’t actually allowed in harems. Going back to Ellis’ video essay, these 19th century European men of course struggled with the “why can I not have the thing?” mentality, and so were naturally inclined to go off nothing but their sexy, sexy fantasies.

For example, let us view the harem through the male gaze with Jean-Léon Gérôme’s ‘Pool in a Harem,’ painted in the 1870s.

In comparison is Henriette Browne’s 1860 painting titled ‘A Visit: Harem Interior, Constantinople.’

Beautiful but Problematic

Orientalism, since the publishing of the famous ‘Orientalism’ by Edward Said, has been dubbed inherently racist by many. Many depictions were for sure inspired by colonialism and the want to patronising-ly differentiate civilizations. Adam Shatz in his article ‘Orientalism, Then and Now’ suggests that this hasn’t ended with the Victorians:

“Orientalism is still with us, a part of the West’s political unconscious. It can be expressed in a variety of ways: sometimes as an explicit bias, sometimes as a subtle inflection, like the tone color in a piece of music; sometimes erupting in the heat of argument, like the revenge of the repressed. But the Orientalism of today, both in its sensibility and in its manner of production, is not quite the same as the Orientalism Said discussed forty years ago.”

- Adam Shatz, The New York Review of Books

The Victorians undoubtedly fetishized these cultures in the guise of documenting the culture. And these stereotypes continue to persist to this day. On the site for ‘Reclaiming Identity: Dismantling Arab Stereotypes,’ it’s described how these views contribute to a larger (and inaccurate) view of the Middle East:

“‘Orientalism’ is a way of seeing that imagines, emphasizes, exaggerates and distorts differences of Arab peoples and cultures as compared to that of Europe and the U.S. It often involves seeing Arab culture as exotic, backward, uncivilized, and at times dangerous.”

- arabstereotypes.org

Orientalist artists no doubt made visually stunning works of art, but delving deeper into identifying what makes them more fantasy than reality and the repercussions that came from that is far more important. These works often took away what made the cultures of these regions unique and interesting in order to push their own narrative, and push a consumer trend. When again looking at an orientalist piece perhaps ask yourself what aspects the artist is portraying; reality or fiction?

11K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interior of the Nieuwe Kerke, Delft, with the tomb of William the Silent, Prince of Orange by Hendrik van Vliet (1611/12-1675)

oil on canvas, ca. 1650-1660

192 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Melancholy Thought by Francesco Hayez (1791-1882)

medium unknown, 1842

10K notes

·

View notes

Photo

still from Citizen's Forest by Park Chan Kyong (b.1956)

3-channel black and white video, directional sound, 2016

It is said that a ghost only appears on Earth when there is an unresolved conflict. In Park Chan Kyong’s three-channel film Citizen’s Forest (2016), viewers slip in and out of a comatose state of collective amnesia as they see ghouls from Korea’s past: young students in uniform, resembling those who died in the Sewol Ferry tragedy; men bearing glossy, skull-like helmets, presumably victims of the Gwangju massacre.

10 Korean Artists Who Are Shaping Contemporary Art by Ysabelle Cheung

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of an African Man (Christophle le More?) (detail) by Jan Jansz Mostaert (1475-1555)

oil on panel, ca. 1525-1530

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jeune Femme aux Perles by Marie Laurencin (1883-1956)

oil on canvas, date unknown

Laurencin was perhaps the most celebrated woman painter of avant-garde Paris. She was colleagues with Picasso at a time when few women were permitted into his inner circle. Laurencin was also a society fixture, befriending and painting Coco Chanel, and regularly attending Natalie Barney’s salons. Most of her works portray a syrupy fantasy realm where girls play in perfume clouds - a queer modernist vision that riffed on Fauvism and Cubism while asserting profound independence from these movements. Yet Laurencin’s legacy is shamefully underrepresented in art history. She’s one more great woman artist who’s been left out of the popular canon.

Why Marie Laurencin, the Queen of Avant-Garde Paris, Was Misunderstood for Decades by Miranda Gabbott

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

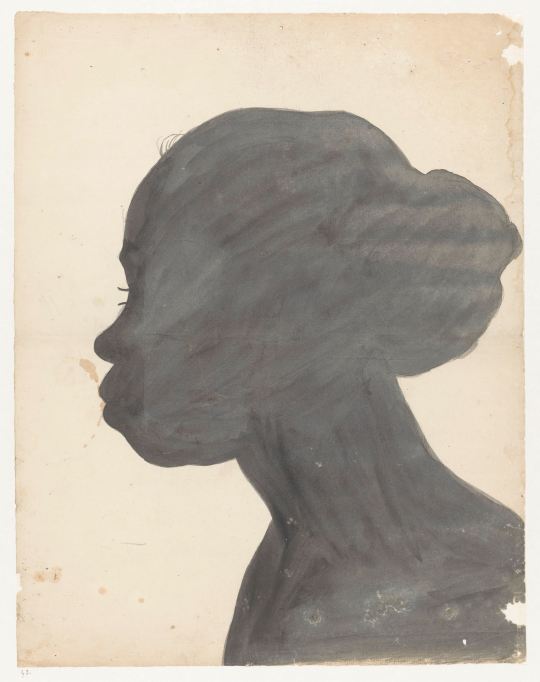

Silhouetportret van slavin Flora by Jan Brandes (1743-1808)

ink and pencil on paper, ca. 1780-5

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vengeance is Sworn by Francesco Hayez

oil on canvas, 1851

214 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bathsheba at her Toilet (detail) by Cornelis van Haarlem (1562-1638)

oil on canvas, 1594

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rotimi Fani-Kayode (1955–1989)

clockwise; Every Moment Counts, 1989

Adebiyi, 1989

Nothing to Lose viii, 1989

Untitled, 1987-1989

A seminal figure in 1980s black British and African contemporary art, Fani-Kayode’s timeless photographs constitute a profoundly personal and political exploration of complex notions of desire, diaspora, and spirituality. [source]

174 notes

·

View notes