Text

Bringing it All Together (07)

The importance of family is extant for non-Asian Americans and Asian Americans alike and plays an important role in mental, physical, and emotional health, and can shape the life of an LGBT youth forever. Yet, the mainstream queer community has framed the coming out narrative as the quintessential LGBT experience despite being based on the limited experience of middle-class White gay men. By being blind to the ways in which the traditional coming out narrative erases people and by lauding gay marriage as the primary issue facing LGBT Americans today, the experiences of LGBT people of color have been swept under the rug and, while all people of color are negatively affected, LGBT Asian Americans have a particular invisibility in both the LGBT and Asian American communities that leaves them unspoken for in mainstream discourse.

Asian culture puts great emphasis on the importance of family and the necessity for familial loyalty and adhesion to traditional norms; while this is susceptible to misrepresentation in popular culture, the disastrous effects of failing to recognize the way LGBT Asian Americans must navigate their LGBT and Asian American identities only worsens the issues they face. Family is a critical part of queer Asian American experiences, and understanding the mechanics behind how LGBT Asian Americans can successfully balance both of their identities can help youth who are especially vulnerable to the ramifications of family rejection and give aid and agency to adults who may still struggle between the two.

Historically, the LGBT community has been seen as a mecca of tolerance and acceptance towards all. Unfortunately, it has its own ills, and the devaluation of queer Asian Americans is one of them.

(image source)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asian American Families & Religion (06)

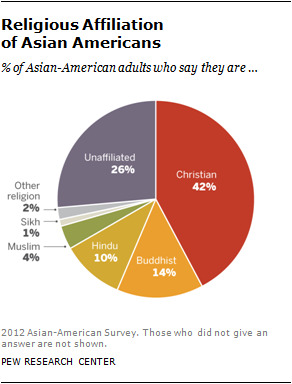

(image source)

As previously described, family support has a significant effect on health outcomes for LGBT youth and adults. In LGBT Asian American populations, the importance of family and acceptance is compounded by cultural values that emphasize familial connections, filial piety, and heteronormative expectations for offspring. Touched on briefly was the role of religion; in this post, that will be expanded upon.

Traditional Asian religions, such as Shintoism or Hinduism, do not address homosexuality or other queer identities (Akerlund & Cheung 289-90). Buddhism, a religion practiced by nearly 500 million across the world (Liu, “Buddhists”), also does not address LGBT identities in traditional texts, though the Dalai Lama has previously condemned homosexual relationships as “sexual misconduct ("Stances of Faith”). This is largely irrelevant, however, since most Asian Americans today are Christian (Liu, “Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths”), a product of relatively successful historical missionary outreaches. This can also be seen somewhat as a reflection of the popularity of Christianity, which comprises just over 70% of the American population (Wormald).

Religious beliefs and homophobia have been linked (Liu, “Religious Beliefs Underpin Opposition to Homosexuality”) and, while religion is not the sole reason Asian American families reject LGBT identities, it has a significant role. It varies from population to population – Koreans tends to be Protestant, Filipinos Catholic, Thai Buddhist, Vietnamese a split between Catholic and Buddhist, and Chinese a unique spread of religiosity and affiliation – and, accordingly, each population’s religious affiliation can be linked, with some consistency, to receptiveness to LGBT identity (Masequesmay 323). Overall, though, due to the strong tie between religion and family acceptance, LGBT youth of color report religious views of their families as a factor in family rejection (Kuper et al. 711).

Additionally, sexuality is rarely discussed in Asian American families due to both religious and cultural taboo; while most receive very little sexual education, including information about bodily processes like menstruation, some receive absolutely none (Kim & Ward 24). Queer Asian American youth and adults thus do not have the “luxury” of talking candidly with their families about their sexuality (Nadal 170), though subtle non-verbal communication may still occur. Parents convey ideals about cultural sexual values even through silence (Kim & Ward 25) just as they and other family members may silently be aware of their children’s LGBT identity (Nadal 170).

Works Cited

Akerlund, Mark, and Monit Cheung. “Teaching Beyond the Deficit Model.” Journal of Social Work Education , vol. 36, Oct. 1999, pp. 279–292., http://proxy.cc.uic.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=3295517.

Kim, Janna L., and L. Monique Ward. “Silence Speaks Volumes: Parental Sexual Communication Among Asian American Emerging Adults.” Journal of Adolescent Research, vol. 22, no. 1, 2007, pp. 3–31., doi:10.1177/0743558406294916.

Kuper, Laura E., et al. “Coping With LGBT and Racial-Ethnic-Related Stressors: A Mixed-Methods Study of LGBT Youth of Color.” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 24, no. 4, 2013, pp. 703–719., doi:10.1111/jora.12079.

Liu, Joseph. “Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths.” Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project, Pew Research Center, 18 July 2012, www.pewforum.org/2012/07/19/asian-americans-a-mosaic-of-faiths-overview/.

Liu, Joseph. “Buddhists.” Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project, Pew Research Center, 17 Dec. 2012, www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-buddhist/.

Liu, Joseph. “Religious Beliefs Underpin Opposition to Homosexuality.” Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project, Pew Research Center, 17 Nov. 2003, www.pewforum.org/2003/11/18/religious-beliefs-underpin-opposition-to-homosexuality/.

Masequesmay, Gina. “How Religious Communities Can Help LGBTIQQ Asian Americans to Come Home.” Theology & Sexuality, vol. 17, no. 3, 2011, pp. 319–335., doi:10.1179/tas.17.3.f6j256341505r572.

Nadal, Kevin L., and Melissa J. H. Corpus. “‘Tomboys’ and ‘Baklas’: Experiences of Lesbian and Gay Filipino Americans.” Asian American Journal of Psychology, vol. 4, no. 3, 2013, pp. 166–175., doi:10.1037/a0030168.

“Stances of Faiths on LGBTQ Issues: Buddhism.” Human Rights Campaign, The Human Rights Campaign, www.hrc.org/resources/stances-of-faiths-on-lgbt-issues-buddhism.

0 notes

Photo

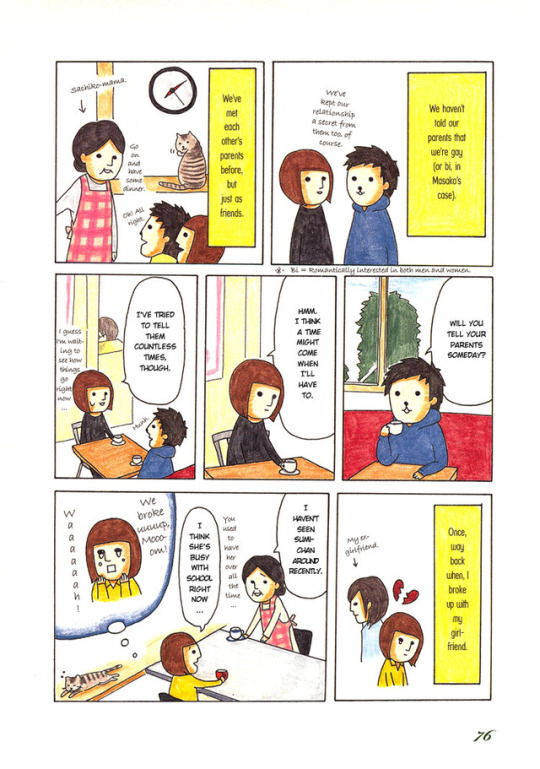

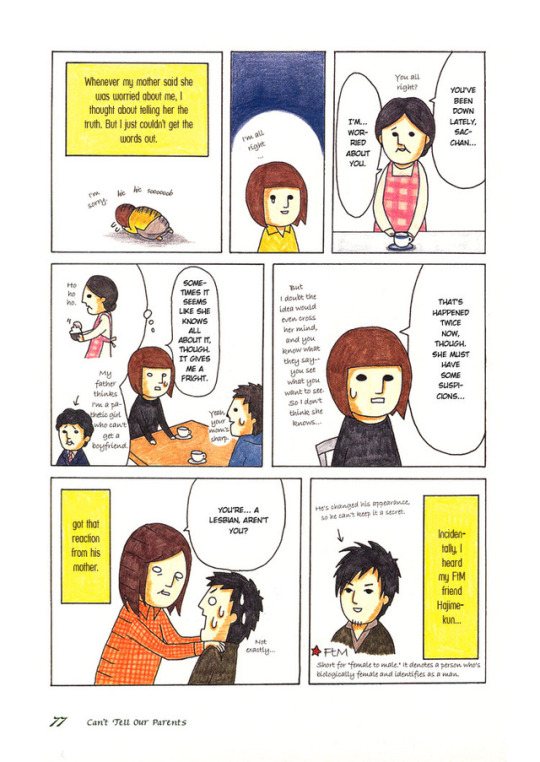

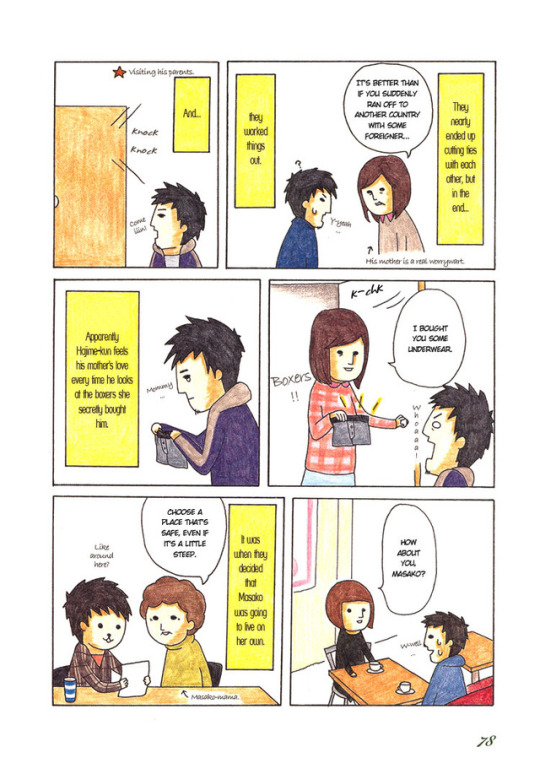

Coming Out (05)

Western gay culture has put upon a pedestal the experience of coming out. It dominates LGBT films, books, music, and dialogues; for many, it is seen not only as an essential part of accepting themselves but a necessity to be honest and true to themselves. Events like National Coming Out Day (Ngo 2) perpetuate the myth that coming out is not only mandatory for queer people, and ignores the reality of many LGBT Americans who suffer severe consequences as the result of coming out, like the loss of employment, family rejection, homelessness, and potentially fatal violence. The preoccupation with being out of the closet can be harmful in its own way, as well (Mitchum) and coming out stories are expected to follow a “stock” narrative (Espinoza), which people can feel pressured to self-edit their stories to conform to for legitimacy. Coming out, though important, has gained a rather ugly side in mainstream society and gay culture.

This becomes especially apparent when applying the narrative to non-European cultures, where coming out can take on a different shape altogether. Despite the existence of “multiple ways of being gay and proclaiming ourselves to be gay,” deviation from the narrative is largely underrepresented. Winter Han describes this as the conceptualization of the supposedly correct way to be gay as being based on gay white men (Kornhaber). For Asian Americans, this rings especially true. The coming out narrative is laden with Western ideals of independence and assertiveness, standing in direct opposition to Asian cultural values. This is embodied in the case of “Fong,” a gay Hmong man. Bic Ngo details prominent aspects of Asian culture and how they relate to Fong’s story: the unification of offspring and family, the need to save face, and the necessity to obey and respect one’s parents. Fong remarked that he “thought "that [his family] care[d] so much about their family’s name and reputation that sometimes…they’d rather care about that part than their own kids” (14) and, while it seems selfish from a Western perspective, it has a direct relationship to alienation and well-being (12-13; 16) in Hmong culture. Fong ultimately negotiates his LGBT identity with his family’s expectations by marrying while maintaining his relationship with his boyfriend (18-20), a marked difference from Western narratives where rejection from family leads to estrangement. Though even Fong’s experience is not representative of the entire Asian queer community, it does provide insight on a different perspective that is rarely seen.

In that vein, included is a chapter about coming out from Honey and Honey, an autobiographical comic drawn by Takeuchi Sachiko, a Japanese lesbian woman. Though she isn’t American, I’ve included it because it provides a humorous, true-to-life depiction of Asian queer, including bisexual and trans, experiences with family and coming out. LGBT comics like this have gained popularity in Japan (as evidenced by the success of My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness), and such comics can help both queer and non-queer people alike see representations of queer Asian identities.

Works Cited

Espinoza, Robert. “'Coming Out’ or ‘Letting In’? Recasting the LGBT Narrative.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 11 Oct. 2013, www.huffingtonpost.com/robert-espinoza/coming-out-or-letting-in_b_4070273.html.

Kornhaber, Spencer. “The Fierceness of ‘Femme, Fat, and Asian’.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 19 May 2016, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/05/kim-chi-rupauls-drag-race-femme-fat-asian-c-winter-han-interview-middlebury/483527/.

Mitchum, Preston. “On National Coming Out Day, Don’t Disparage the Closet.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 11 Oct. 2013, www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/10/on-national-coming-out-day-dont-disparage-the-closet/280469/.

Ngo, Bic. “The Importance of Family for a Gay Hmong American Man: Complicating Discourses of ‘Coming Out.’” Hmong Studies Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 1–27.

0 notes

Text

Gay & Asian: an Impossibility? (04)

(image source)

The double minority of queer and Asian American identities can be rife with strife and pressure to fit the mold. One man put it this way: “I am outcast amongst an outcast” (Poon & Ho 255). This sentiment is furthered by the lack of acknowledgement of queer Asian identities in the LGBT and Asian American communities, and by academia that tends to fail to fully address the diversity of queer identity. The void in queer Asian American representation is exacerbated by the lack of dialogue about it.

Consequently, Asian Americans don’t have access to a diversity of knowledge and representation of their sexuality. Asian sexuality, even in queer relationships, tends to center around stereotypes of Asian culture and bodies as submissive and feminine (Poon & Ho). Gay Asian men are denied masculinity (Chong-suk 3) and experience fetishization by “rice queens” (Chung & Katayama; Poon & Ho 258), just as queer Asian American women are “reduce[d] to an exotic stereotype” (Sung et al. 57).

The Asian American community is similarly alienating. For queer Korean Americans, being LGBT can mean complete exclusion from the community, their identities seen as “an oxymoron, simply unconceivable” (Rhee 78). Thus, while gay marriage remains the poster child of LGBT issues, for LGBT Korean Americans “the need for recognition as members may be more pressing” (Rhee 79). Additionally, Confucian values and the expectation of heterosexual marriage and continuing the family lineage can be seen as contradictory to LGBT identities (Akerlund & Cheung 290; Chung & Katayama; Masequesmay 328; Ngo 3). The prevalence of evangelical Christian influence further amplifies the view of LGBT people as unnatural (Cheng 542-3; Masequesmay 329; Rhee 82-3).

Queer Asian American identities have become increasingly visible in the mainstream with icons like George Takei and Margaret Cho, but they still are not fully accepted by either community, putting them in limbo.

Works Cited

Akerlund, Mark, and Monit Cheung. “Teaching Beyond the Deficit Model.” Journal of Social Work Education , vol. 36, Oct. 1999, pp. 279–292., http://proxy.cc.uic.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=3295517.

Chong-suk, Han. “Being an Oriental, I Could Never Be Completely a Man.” Race, Gender & Class, vol. 13, no. 3, 2006, pp. 82–97.

Chung, Y. Bary, and Motoni Katayama. “ Ethnic and Sexual Identity Development of Asian-American Lesbian and Gay Adolescents.” Professional School Counseling, vol. 1, no. 3, Feb. 1998, pp. 21–25., http://web.b.ebscohost.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=1&sid=a9dc7a35-42f7-4d09-9b6b-f61e1fc54074%40pdc-v-sessmgr01&bdata=#anchor=AN0000288448-2&AN=288448&db=ehh4.

Masequesmay, Gina. “How Religious Communities Can Help LGBTIQQ Asian Americans to Come Home.” Theology & Sexuality, vol. 17, no. 3, 2011, pp. 319–335., doi:10.1179/tas.17.3.f6j256341505r572.

Ngo, Bic. “The Importance of Family for a Gay Hmong American Man: Complicating Discourses of ‘Coming Out.’” Hmong Studies Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 1–27.

Poon, Maurice Kwong-Lai, and Peter Trung-Thu Ho. “Negotiating Social Stigma Among Gay Asian Men.” Sexualities, vol. 11, no. 1-2, 2008, pp. 245–268., doi:10.1177/1363460707085472.

Rhee, Margaret. “Towards Community: KoreAm Journal and Korean American Cultural Attitudes on Same-Sex Marriage.” Amerasia Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2006, pp. 75–88., doi:10.17953/amer.32.1.a058286569608j40.

Sung, Mi Ra, et al. “Challenges, Coping, and Benefits of Being an Asian American Lesbian or Bisexual Woman.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, vol. 2, no. 1, 2015, pp. 52–64., doi:10.1037/sgd0000085.

1 note

·

View note

Text

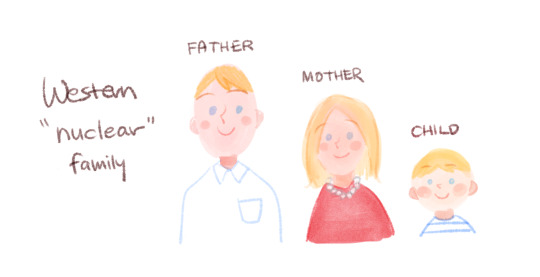

Asian Culture & Family (03)

(image source: self)

Asia spans over 17 million square miles (National Geographic 264) and 48 countries, with a total population of roughly 4,504,428 people, making up almost 60% of the entire world (“World Population Prospects 2017”).

Though Asian cultures are varied and diverse, some share historical and cultural roots. East Asian countries, for instance, were historically strongly influenced by Chinese culture. Korea served as a gateway between China and Japan through which Chinese culture travelled to Japan (“Korean Influence”), with scores of other interactions between all three countries shaping each other. A legacy of this connection is the spread of ideologies like Confucian philosophy and Buddhism, leading to certain commonalities like the nature of interpersonal relationships (Ying, Coombs & Lee 351).

Asian culture is typically associated with collectivism and tradition, and while aspects of Asian culture may be romanticized or even wholly, this shapes the way family is viewed. In the West, a family is typically made up of two parents (usually a mother and father) and their children. Other cultures outside of the West operate differently, with extended family that may live with the main family unit (“Culture and Family Dynamics”).

Additionally, in Asian cultures relationships have a deep sense of hierarchy. Elders are to be respected and obeyed by the younger members of the family, even as adults. Marriage and career alike are seen as family, not individual, matters (Ying, Coombs & Lee 351). A member of the family is not separate from the family even at work or at school. To separate from the family and reject the family values and expectations can have negative consequences on psychosocial health (Homma & Saewyck 74). This leads to stark differences in the ways which queer Asian Americans and European Americans handle familial rejection.

Works Cited

Carteret, Marcia. “Culture and Family Dynamics.” Dimensions of Culture, Marcia Carteret, 2011, www.dimensionsofculture.com/2010/11/culture-and-family-dynamics/.

Homma, Yuko, and Elizabeth M. Saewyc. “The Emotional Well-Being of Asian-American Sexual Minority Youth in School.” Journal of LGBT Health Research, vol. 3, no. 1, Dec. 2007, pp. 67–78., doi:10.1300/j463v03n01_08.

“Korean Influence.” Nakasendo Way, WalkJapan Ltd, 8 May 2014, www.nakasendoway.com/korean-influence/.

National Geographic. National Geographic Family Reference Atlas of the World. 2nd ed., National Geographic, 2006.

“World Population Prospects 2017.” United Nations, United Nations, esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/DataQuery/.

Ying, Yu-Wen, et al. “Family Intergenerational Relationship of Asian American Adolescents.” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, vol. 5, no. 4, 1999, pp. 350–363., doi:10.1037/1099-9809.5.4.350.

0 notes

Text

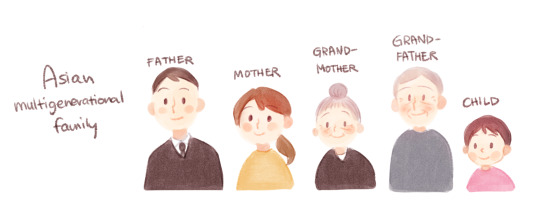

On the Importance of Family in the LGBT Experience (02)

(clickthrough for image source)

For LGBT and non-LGBT people alike, rapport with family is a protective factor for health (Resnick 830-1). For LGBT people, however, such rapport is uncommon.

The most common reactions to coming out are negative (Patterson 1063), putting youth at risk of homelessness or abuse. Acceptance is associated with higher self-esteem and self-acceptance (Patterson 1063) and is so strong a protective factor for LGBT people that it consistently predicts self-esteem, social support, general health, rates of depression, suicidal thoughts and behavior, substance abuse, and risk of unsafe sex despite individual background characteristics (Ryan et al. 207-8).

Rejection is a very real danger, though: 39% of LGBT Americans had been rejected due to their identity (“A Survey of LGBT Americans”) and 89% of homeless LGBT youth lose their home due to family rejection (Durso & Gates 4). Additionally, conflict with family is common. Most LGBT youth report family difficulties as their most frequently recurring difficulty (Kuper et al. 810,710) and LGBT Asian Americans similarly express “denial and difficulty in family accepting” as a common theme in familial relations (Nadal), an omen that doesn’t bear well for LGBT Asian Americans who are rejected by both Asian American and LGBT communities. The loss of what would traditionally be their closest social network is especially devastating (Kuper et al. 711).

Since research so far focuses on primarily White, middle-class LGBT Americans, future research should target people of color and a greater diversity of backgrounds (Lai 195). Among LGBT people, those of color generally experience the highest rates and the greatest severity of family rejection (Klein & Golub 197), and a majority of homeless LGBT youth are of color and have experienced family instability (Robinson). In the context of positive health outcomes, being a person of color puts one at a major disadvantage.

Works Cited

“A Survey of LGBT Americans.” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 13 June 2013, www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/06/13/a-survey-of-lgbt-americans/.

Durso, Laura E, and Gary J Gates. “Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Service Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth Who Are Homeless or At Risk of Becoming Homeless.” The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund, 2012.

Klein, Augustus, and Sarit A. Golub. “Family Rejection as a Predictor of Suicide Attempts and Substance Misuse Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults.” LGBT Health, vol. 3, no. 3, 2016, pp. 193–199., doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0111.

Kuper, Laura E., et al. “Coping With LGBT and Racial-Ethnic-Related Stressors: A Mixed-Methods Study of LGBT Youth of Color.” Journal of Research on Adolescence, vol. 24, no. 4, 2013, pp. 703–719., doi:10.1111/jora.12079.

Lai, Hor Yan. “Letters to the Editor: Regarding "Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, vol. 24, no. 3, 2011, pp. 195–195., doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2011.00297.x.

Nadal, Kevin L., and Melissa J. H. Corpus. “‘Tomboys’ and ‘Baklas’: Experiences of Lesbian and Gay Filipino Americans.” Asian American Journal of Psychology, vol. 4, no. 3, 2013, pp. 166–175., doi:10.1037/a0030168.

Patterson, Charlotte J. “Family Relationships of Lesbians and Gay Men.” Journal of Marriage and Family , vol. 62, no. 4, Nov. 2000, pp. 1052–1069.

Resnick, M. D., et al. “Protecting Adolescents from Harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health.” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 278, no. 10, 10 Sept. 1997, pp. 823–832., doi:10.1001/jama.278.10.823.

Ryan, Caitlin, et al. “Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, vol. 23, no. 4, 2010, pp. 205–213., doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Introduction (01)

(image source)

With the legalization of gay marriage, the introduction of sexual orientation and gender identity as protected classes against discrimination, and a greater acceptance of LGBT identities, societal views on homosexuality have inverted. In 1977, under half of Americans believed that homosexual relationships should be legal; in 2017, that percentage has increased by ~67% (Gay and Lesbian Rights). For some, it seems as if the “fight” for equality is over.

However, the LGBT community and mainstream gay rights movement has always had undercurrents of racism, classism, and sexism (EP; Faye; Flores). Though the prototypical LGBT person tends to be a middle-class White male, the movement has historically been furthered by marginalized groups: people of color, lower socioeconomic status (SES), and trans people (Flores).

One commonly overlooked group in society and in the mainstream LGBT community is the Asian American population, viewed commonly through a lens of racism such as the model minority, a concept invented in 1966 used to propagate the idea that Asian Americans overcame historic discrimination and racism through hard work and other “innately” Asian traits (Cheryan & Bodenhausen 173) while failing to take into consideration the historical context of Asian immigration and the cultural context of anti-Asian racism in 20th century America. Such racism extends similarly to queer Asian Americans, whose experiences and stories are devalued by Western narratives of sexuality. Much of the focus on anti-Asian racism in popular news outlets centers around gay Asian men and dating, with Grindr being the focal point (Bollinger; Jones; Ly), but little dialogue is found in mainstream spaces about the erasure of queer Asian American lives and experiences as a whole. This blog aims to counteract that and explore one specific aspect of queer Asian American life that holds particular importance: family acceptance.

Works Cited

Bollinger, Alex. “White Guy Surprised by Anti-Asian Racism on Grindr.” LGBTQ Nation, LGBTQ Nation, 16 Sept. 2017, www.lgbtqnation.com/2017/09/white-guy-surprised-anti-asian-racism-grindr/.

Cheryan, S, and G V Bodenhausen. “Model Minority.” Routledge Companion to Race & Ethnicity , Routledge, 2011, pp. 173–176.

EP. “Web Event 2: Classism and the Queer Community.” Serendip Studio, Serendip, 7 Oct. 2013, serendip.brynmawr.edu/exchange/critical-feminist-studies-2013/ep/web-event-2-classism-and-queer-community.

Faye, Sean. “The Gay Men Who Hate Women.” Broadly, Vice Media LLC, 11 Nov. 2015, broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/jpyz8k/the-gay-men-who-hate-women.

Flores, Andrew R. “Yes, There’s Racism in the LGBT Community. But There’s More Outside It.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 7 July 2017, www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/07/07/yes-there-is-racism-in-the-lgbtq-community-but-not-as-much-as-outside-it/?utm_term=.b5a9b8fe6abb.

“Gay and Lesbian Rights.” Gallup.com, Gallup, Inc., news.gallup.com/poll/1651/gay-lesbian-rights.aspx.

Jones, Owen. “No Asians, No Blacks. Why Do Gay People Tolerate Such Blatant Racism?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 24 Nov. 2016, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/24/no-asians-no-blacks-gay-people-racism.

Ly, David. “How Online Racism Towards Gay Asian Men Affects IRL Dating.” Vice, Vice Media LLC, 20 Apr. 2017, www.vice.com/en_au/article/mgy7wx/how-online-racism-towards-gay-asian-men-effects-irl-dating.

9 notes

·

View notes