#Ada Akpala

Text

youtube

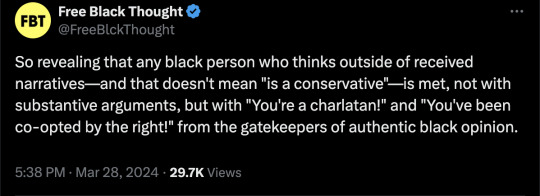

It's truly amazing that things have gotten to the point where the principle of colour-blindness is now seen as a tactic of "the right."

You can almost hear them say "ugh," when Coleman says that helping the poor will also help poor whites.

There's no better demonstration that the Dems have completely abandoned the working class than watching them recoil at anything that isn't identity politics. And they wonder why the polls turn out the way they do.

-

For reference:

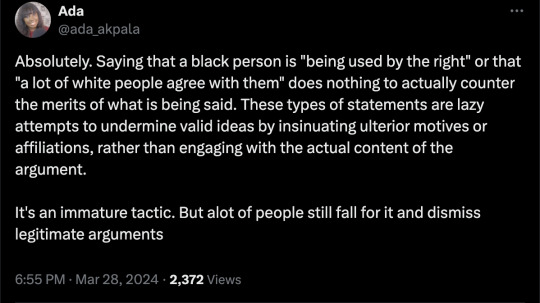

"Why We Can't Wait," Martin Luther King, Jr.

"White Fragility," Robin DiAngelo

I have no damn clue who Sunny Hostin is, but she's factually wrong. And ignorant. And considering she's a regular and Coleman's a guest with 10 minutes, she needs to shut her pie hole.

#Coleman Hughes#The View#Ada Akpala#Free Black Thought#color blind#colorblind#color blindness#colorblindness#antiracism as religion#antiracism#religion is a mental illness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Ada Akpala

Published: Oct 15, 2022

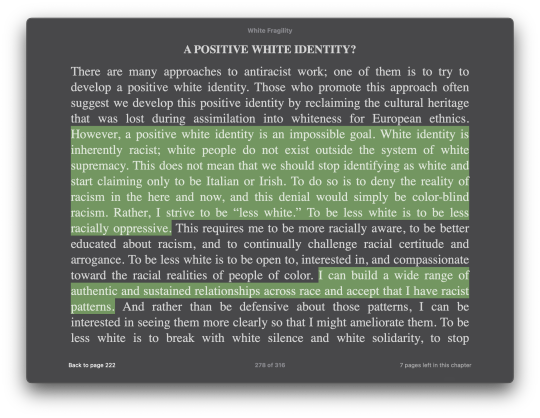

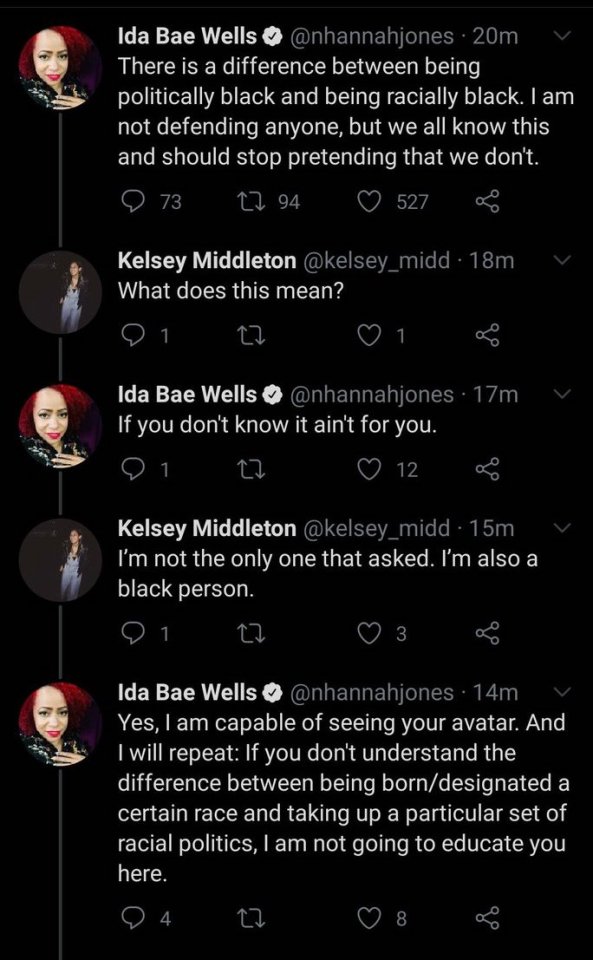

The term “political blackness” gained notoriety in the 1970s and came to refer to anyone in the UK who was likely to face prejudice because of their skin tone—that is, anyone who was not “white.” This ideological framework gave black Britons increased political and cultural power, as well as a platform to voice the many inequalities they faced in society.

By the 1990s, the term had lost its lustre, not only among other minority groups who felt it erased their specific identities, but also among blacks who felt that their socioeconomic plight was being diluted at best and hijacked at worst by the uniquely different challenges that other groups faced. Nevertheless, vestiges of the ideology persisted and continue to play a central role in the way that many black people view both themselves and others.

It goes without saying that today’s society, particularly in the Western world, is obsessed with racial identity. Despite seemingly good motives to end racism and advance equality, the current fixation on racial differences is stymying those efforts. With calls for colour-consciousness to be a social norm, it is virtually taboo to be thought of as being “colour blind” in many anti-racist circles.

Persisting in these race-politics games, in which essentialist traits are assigned to individuals based on their group identity, or where skin colour is elevated above other characteristics, actually fosters a culture in which racial animosity, tribalism, and intergroup conflict will be difficult to overcome.

What is racial identity in the context of blackness? What does it mean exactly? Who has the authority to decide its meaning? These questions seem odd, and they certainly are, but they persist because so many people, regardless of ethnicity, feel compelled to make observations about the “blackness” of others. Recently, Rupa Huq, whose parents immigrated from Bangladesh to the United Kingdom in 1962, deemed it acceptable to assert that ex-Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng was “superficially black” due to the prestigious schools he attended and the fact that “if you heard him on the radio, you wouldn’t know he was black.”

Her suspension as a Labour Party representative was reasonable and expected, but it does not answer all the questions that arise following incidents like this. Where does this audacity to comment on a person’s heritage originate? What characteristics define a genuine black person? Is it phenotypic features? Is it based on a person’s geographical origin? Or does it simply depend on whether or not they “sound black?” Has Kwasi Kwarteng’s blackness been diminished as a result of his attendance at affluent schools and use of a refined dialect? Would his use of slang and broken English pass the test of genuine blackness?

This type of myopic thinking emerges time and again, exposing the true bigotries of these so-called liberals. They love to point the finger at “the system” whenever they are questioned about the factors that impede the social advancement of certain communities. Yet they fail to recognise that their own lowered standards and de haut en bas approach are the real enemies of black progress.

The Huq-Kwarteng case is a prime example of how being black is not about one’s ethnicity, background, heritage, or even skin colour; rather, it is one’s adherence to political ideology, resonating with the Political Blackness movement of the 1970s.

“We had political unity in cultural diversity. And Black was the colour of our politics, not the colour of our skins.“ – Ambalavaner Sivanandan

Attacking people’s ethnicity rather than challenging their ideas is a sign of intellectual immaturity. Whether it’s being dubbed “a black face” or having your entire cultural identity questioned for not voting a certain way, it appears that being black implies only one way of being and thinking. I, too, have been told I’m “not black” and “excluded” from the black community because I didn’t agree with the standard talking points about the “black experience.”

Kwasi Kwarteng is visibly black, but that doesn’t mean much these days. A black person who had a good upbringing and came from privilege appears to be an oxymoron. True blackness must mean a challenging existence and the ceaseless enduring of hardship. We should especially be grateful to those who have assumed the role as “guardians of blackness,” admitting or expelling people based solely on their own perception of whether or not they represent authentic blackness.

Ironically, those who have traditionally been regarded as the most ardent supporters of black people are also those who believe they have the absolute authority to police a black person’s identity. They are convinced in their delusory minds that they are the only ones who can provide the best policies, ideologies, and platforms for black people.

Reality has repeatedly exposed them as fraudsters who profit from the black community’s deep wounds and sensitive issues. Yet, we enable and reward such people and the platforms they represent. We make excuses for them, elect and re-elect them, in spite of the scores of reasons not to. These self-appointed protectors and conferrers of blackness, use the concept of blackness itself as a tool to rein in defiant individuals.

It’s interesting to see which accomplished black people the allies choose to endorse and which ones they choose to denigrate. According to Rupa Huq’s logic, Barack Obama, who also attended elite academies and internationally renowned universities, should not be black enough either.

No one, however, views his blackness as superficial; they may disagree with his ideas and criticise some of his policies, but he is still typically held up as a symbol of black excellence, and rightly so, given that he made history as a black man. The point is that the rules must remain consistent; otherwise, it reinforces the notion that blackness has more to do with adhering to particular sociopolitical ideologies than anything else, and we should stop pretending that this is not the case.

Many of these advocates for social justice seem unwilling to acknowledge that black people can and do have a wide range of life experiences. Imagine being labelled “superficial” for having attended prestigious schools. Hundreds of thousands of black parents around the world invest their entire savings to send their children to the best schools in the world. According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency’s 2020/2021 statistics, there are currently 21,305 Nigerian students pursuing degrees in the UK. It’s unfortunate that those who have invested in themselves and strived to pursue a meaningful career and create a comfortable life for their families are told they aren’t black enough or that they act white. Why are we still having this conversation in 2022?

Having a better life is not a transition from one racial group to another. There is more to being black than just struggle and suffering. If anything, young black people, especially young black boys, need more role models like Kwasi Kwarteng.

It’s important to note that many black people are being socially programmed to downplay their accomplishments in favour of their struggles. Many black entertainers and public figures exaggerate their hardships or conceal their privileged upbringings out of fear of alienating or repelling fans. There seems to be a fetishization of struggle, and until this collective mindset changes, blackness will remain synonymous with oppression.

Observe that those whose blackness is most frequently questioned are those who dare to go against the grain of mainstream thought and who have unfettered themselves from being beholden to political parties and institutions that falsely portray themselves as the saviours of black people. The attacks on them are unending – and have become normalised. Why else would Biden have felt so at ease claiming that people considering voting for Trump in the 2020 elections were not black?

This overdependence on certain parties, who have repeatedly pretended to be allies in order to pass laws and enforce policies, has only pushed black people to the back of the line, while everyone else gets to skip ahead. Their entire structure is energised by the trauma of black people, to the point where black advancement and upward mobility appear to be an affront to their hegemony.

As a result, black people must speak and act the same, aim for the same heights and sink to the same depths. Personal ambition must be surrendered to groupthink, or else one runs the risk of losing their blackness. As though blackness is something that is given and taken by political parties as a reward for good or bad behaviour, as a parent does with a child.

That we still need to have this conversation today is just as sad as it is an indictment on our society as a place that grapples with the meaning of blackness and has political overlords and institutions bent on defining, policing, and boxing in the multiplicity of experiences of a “racial” group. As much as we want to fight against people like Huq and their low standards for black people, we can also be honest with ourselves and understand that a black person can be whoever they want to be, believe whatever they want to believe, and associate with whoever they want to associate with. The same rights as any other human being. While criticising, disagreeing with, or challenging our views is acceptable, doing so on the basis of our skin colour is not. It is time to put an end to practises such as identitarian gatekeeping, hive mentality, and the downplaying of our privileges in order to satisfy the conditions of a narrative or fit into a particular cultural mould. The time to end it is now. We are free.

--

Compendium of Free Black Thought: "Authenticity"

==

Also:

#Eric's Electrons#Ada Akpala#blackness#politically black#political blackness#antiblackness#anti blackness#black voices#authentic#antiracism#antiracism as religion#religion is a mental illness

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Ada Akpala

Published: Oct 3, 2023

I recently found myself reflecting on a radio program I once listened to on BBC Sounds. The featured guest was Simon Woolley, a distinguished figure in British society. The program was the iconic "Desert Island Discs," which invites celebrities and public figures to envision themselves stranded on a deserted island. During the show, the guest must select and discuss eight pieces of music, a book, and a luxury item they would want to have on the island. These choices are intended to reveal their personal tastes, cherished memories, and life experiences.

Throughout the podcast, Lord Woolley openly discussed his life's trials and triumphs, including personal family issues, his experience as an adoptee, and his complicated feelings towards his birth mother. The conversation was a poignant and captivating mix of humour, inspiration, deep reflection and heart-warming moments — all the ingredients that make for an enjoyable listening experience.

Around 15 minutes into the episode, just before he played his fourth selection, 'Titanium' by David Guetta featuring Sia, a statement he made momentarily dampened my enjoyment of the show. At this point, he was sharing his struggles with identity and bullying, becoming emotional as he described the profound conflict he experienced when he reconnected with his birth mother at the age of 16. It felt as though he had somehow betrayed his adopted mother. He went on to explain that his choice of the song 'Titanium' was based on the lyrics, “knock me down and I get up… I won’t fall, I am Titanium.” According to him, this resilience to keep getting back up represented the black experience.

However, this resilience needed to confront life's challenges is not an exclusive attribute of the black experience; instead, it is a fundamental aspect of the human condition. Such capacity to adapt, grow, and endure in the face of adversity is a shared characteristic that transcends racial and ethnic boundaries. In fact, this trait applies not only to human beings but also extends to various species within the animal kingdom and other life forms, where survival often depends on an organism's ability to adapt to changing environments and challenges.

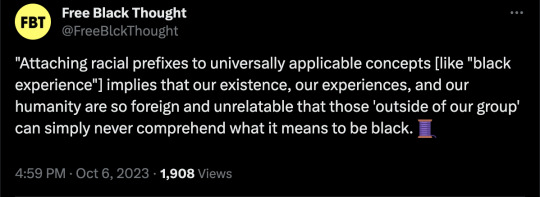

The insistence on attaching racial prefixes to universally applicable concepts is not only illogical but also serves to alienate us as black individuals. It implies that our existence, our experiences, and our humanity are so foreign and unrelatable that those "outside of our group" can simply never comprehend what it means to be black.

This attitude also has the effect of implying that struggle, hardship, and pain are direct synonyms for being black. This means that anyone who identifies as black is assumed, by default, to have experienced such gruelling hardships throughout their lives. So much so that if a black person expresses otherwise, they are often labelled as one of three things: an exception, a traitor, or deluded.

It's undeniable that black individuals have faced a distinct set of challenges throughout history, but it's equally important to acknowledge that various groups, too, confront their own unique obstacles and adversities. The notion that one group's challenges are more “real” or “unique” than another's oversimplifies the complex dynamics of human experience.

Usually those who speak of the “black experience” are speaking in terms of black people dealing with racism and discrimination, both past and present.

I would argue that throughout history, different groups have been demonised, ostracised, and dehumanised simply because of their group identity. In today’s world, there are numerous accounts of individuals from various racial groups finding themselves excluded and discriminated against based on their skin colour or racial identity, ironically in the name of equity and inclusion. Being a victim of racial discrimination is not exclusive to being black.

Various groups have their own distinct histories and cultural dynamics, and no two life experiences are identical. However, universal and timeless themes in life, such as joy, love, pain, rejection, loss, and death, transcend cultural boundaries and resonate with all of us to some extent.

As we continue our efforts to find effective solutions for easing intergroup tensions and improving social harmony in our multicultural and multiracial societies, a foundational step toward achieving this goal is to actively address and eliminate racialised and separatist language and thinking from our discourse and collective consciousness.

#Free Black Thought#Ada Akpala#black experience#racial discrimination#equity#inclusion#diversity#diversity equity and inclusion#adversity#religion is a mental illness

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

By: Kai Whiting and Ada Akpala

Published: Dec 20, 2022

Few things are as multifaceted or complex as personal identity. Yet, numerous social media posts and newspaper articles seem to suggest that we can somehow capture our unique individuality in one or two words, using broad labels such as black, white, gay, male and so on. But how could one word ever accurately depict a person’s culture, history, life experiences, physical characteristics, values and beliefs—not to mention a variety of other factors? Will two men have nearly identical experiences just because they happen to be men? To what extent can any label—or even a whole set of labels—help us to accurately understand the world inside someone else’s head and capture our own sense of self and the nature of our emotions, ideas and intentions?

Humans have been naming, labelling and categorising ever since we could paint cave walls. In the Abrahamic scriptures, Adam is asked to label every kind of animal that God introduces him to. Labels often help to simplify matters, making it easier for members of the same group to seek each other out for activities such as collective worship, marriage and friendship. But they can also cause us to judge others as if they were one-dimensional representatives of their group characteristics, rather than individuals in their own right, and this can impoverish our human experience and damage our sense of connection.

Consider the label privileged, which is often applied to western people with pale complexions on account of their lack of melanin. It is a fallacy to assume that racial privilege always trumps all other factors that impact a person’s life—even if we make provisions for those factors using the concept of intersectionality. In any case, labels do little to alter pre-existing attitudes. As researcher Erin Cooley found when she conducted a survey on attitudes towards poverty, when liberals read about white privilege, “it didn’t significantly change how they empathised with a poor black person—but it did significantly bump down their sympathy for a poor white person.” The counterargument to this is that, while white privilege does not guarantee the absence of struggle, it guarantees the absence of race-based struggle. But even this is not always true, since white people are not immune from being excluded or discriminated against on account of their racial identity.

The placement of whiteness at the apex of a hierarchy of privileges is paradoxical. What about white people in countries such as Latvia? Is it reasonable to assume that Latvian culture reflects American or British culture when it comes to notions linked to identity? Might it be that the language used by Americans to describe themselves is drawn from a specific context and a history that does not readily form part of the Latvian understanding of the world? Where do Romanians fit in? How many of them see themselves primarily as white in the same way some Americans might? The danger of assuming, stripping away, downplaying or even overemphasising a specific identity marker is that we might ignore the plethora of other potentially more important markers. We then might overlook the associated privileges that someone can be born into, such as a stable family life, a prosperous nation, high social class and access to wealth, an agreeable geographical location and English as a native language. All these elements affect a person’s outlook and opportunities.

Labels played a key role in shaping the dystopian realities of the twentieth century. The Holocaust, apartheid, Jim Crow laws and Idi Amin’s expulsion of Asians from Uganda all relied on the use of language to both unite and empower the tyrants and to stigmatise and exclude their victims. The weaponisation of language was an enabling factor in the genocidal Parsley Massacre of 1937, which resulted in the racially motivated murder of 12,000 Haitians living in the Dominican Republic. When the Dominican military could not rely on the colour of the person’s skin to ascertain whether they were Haitian, they made them say the Spanish word for parsley (which Haitians pronounce without a rolled R). Failure to pronounce the word perejil in the right way meant death.

So, to what extent has the West learned from such atrocities, which led to the criminalisation and ostracization of entire populations? And how well do we understand the role of language in fostering or undermining social cohesion?

Most people seem to agree that words matter. In recent years, there has been no shortage of celebrities, politicians and even members of the public apologising for using “inappropriate” language or making “inappropriate” remarks. Most reasonable people take great care as to how they address others—avoiding derogatory words because they genuinely do not enjoy upsetting people, not solely because they wish to avoid public backlash or professional repercussions. The challenge in navigating the public square, particularly on social media, is that certain colloquialisms or linguistic trends that were popular just a few years ago, have since been deemed so offensive that they should never be used, regardless of context.

At the same time, newspaper editors and journalists seem unconcerned about offending specific groups, so long as it is seen as punching-up. The Glastonbury Festival was chastised for being “too white.” After England’s women’s football team defeated Norway 8–0, much ado was made about the lack of non-white players on the field and on the bench. The team’s performance was of secondary concern, as was sport’s meritocratic selection process, which differentiates based on ability and not on immutable characteristics—at least not since the days of South African apartheid, when who could represent that country was determined on the basis of skin colour. Yet in 2022, while the English public was celebrating the team’s accomplishment, the BBC was so taken aback by the players’ white faces that they questioned whether a “fix” was required. White is no longer a descriptive label, denoting one’s melanin levels; it has been transformed into a political and moral issue. Yet, the GB women’s relay team that broke a national record at the Tokyo Olympics was entirely black—and no one seemed to deem this lack of diversity unacceptable. When did it become acceptable to report that an all-black team exists because of effort, skill and hard work, whereas an all-white team can only exist because of privilege, inequity and the exclusion of ethnic minorities?

Labels are not inherently bad or unimportant. The fact that you are white (pale-skinned) matters on a hot summer day. Likewise, it matters if someone offers to bake you a cake and you happen to be diabetic. If you are invited to a barbecue, you should let the hosts know if you are a vegan. Our preferences, needs and ways of life can all be revealed by labels—and that’s great. However, we must also remember that life is often more nuanced than this.

During an interview for 60 Minutes, Mike Wallace asked Morgan Freeman how to end racism. Freeman responded, “I will no longer refer to you as a white man and I will request that you stop referring to me as a black man.” Freeman wasn’t renouncing his heritage or ignoring the ethnicity of the man opposite him; rather, he was highlighting the ways in which labels can create a problem that would go away if we changed how we relate and refer to one another.

Identity should not be exclusive. One’s love for one’s native country, for example, should not preclude immigrants from loving that country too. The existence of one person’s privilege does not imply that another person lacks privileges of their own.

The heptapod language featured in Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 film Arrival depicts the past, present and future as cyclic, fluid and simultaneous. In the film, their language enables the aliens to transcend time. This is a fantasy—but it is not so far-fetched to believe that human language, if used appropriately, could help us transcend the limitations of labelling and categories. With a bit of effort and care, it could also assist us in getting rid of the zero-sum mentality that some labels have come to imply. Our relationship with language must evolve, and, as we learn to use language as a tool to foster connections, we can effectively de-tribalise our culture and de-weaponise our speech.

#Ada Akpala#Kai Whiting#identity labels#labels#no labels#whiteness#privilege#identity#white privilege#racism#stereotypes#wokeness as religion#cult of woke#woke#wokeism#woke activism#religion is a mental illness

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

By: Ada Akpala

Published: July 11, 2022

Racial prejudice has long been a thorn in humanity's side. It has long served as the primary impetus for some of humanity's most heinous deeds. Despite the international attention it has received, the many steps that have been taken to address it, and the progress that has been made, prejudice and discrimination nonetheless continue to exist and to negatively impact the lives of members of marginalized groups in numerous ways.

In the eyes of some, racism in society appears to be worsening, and racist remarks, actions, behaviours, and incidents appear to be on the rise. Almost every week, a new video of a person—typically white—apparently caught in the act of doing or saying something racist, circulates on the internet. The media opportunistically seizes on these incidents to highlight, if not exacerbate, the problem of racism.

While some suppose that racism is becoming more prevalent, others argue that racism has always been prevalent and is only becoming more visible as people become better educated and technology is available to capture incidents. Increasingly, “racism” is being used as a catch-all term to refer to any behaviour, attitude, or outcome a member of a minority group perceives as in any way negative.

In recent years, numerous unsubstantiated and even patently false claims of racism have deepened divisions in societies that cannot agree on how to come to terms with a past influenced by racial inequality.

One name immediately comes to mind with respect to false claims of racism: Jussie Smollett, the black Empire actor who orchestrated a hate crime and falsely claimed to have been the victim of a racist and homophobic attack. Smollett is believed to have staged the attack to increase his notoriety and advance his career. His false claims exemplify how racism can be used for personal gain.

This article discusses some lesser-known instances in which false allegations of racism have been leveled against others, with the accusers facing minimal or no consequences for their conduct.

There has been little research on the psychosocial and psychological consequences of false accusations of racism, but these can clearly have serious negative consequences for both the individuals accused and the groups to which they belong. In recent years, race relations have steadily worsened, according to polling data. A false accusation doesn’t hurt only the individual accused, but also their family and even the group they belong to.

Nobody is immune to false racist accusations. It can affect otherwise decent workers, such as Dominique Moran, a restaurant manager who was wrongly labelled a racist and became the target of vile online abuse following the viral video of her allegedly refusing to serve a group of black men. It was later revealed the group of men portrayed as the victims were known to "dine and dash," meaning they would eat at restaurants but then flee when the bill arrived. By the time the facts of the incident were fully revealed, Moran had already lost her job and received hundreds of messages vilifying and threatening her and her family. Not only that, but she found herself dealing with fear, paranoia, distrust, and shame, demonstrating the psychological battles one can face as a result of false accusations. Moran eventually found work, but the incident left her with a sense of vulnerability she had never felt before.

In another incident, four women in Coventry, UK, were subjected to racial abuse as they attempted to enter a taxi. The perpetrator was quickly identified after the video went viral and his photos and social media handles were posted online. The only issue was that the wrong individual had been identified. Barney Schneider, a fourth-year Coventry University student, was mistaken for the man in the video due to an uncanny resemblance. Schneider was viciously attacked online, received threatening messages, and expulsion from his university was demanded. As in Dominique Moran’s case, revealing the facts did nothing to take back the unforgiving and wrathful abuse that Schneider had endured.

An older incident highlights how even public officials are vulnerable. Shirley Sherrod, Georgia State Director of Rural Development, was fired on July 19, 2010, as a result of media reports from an event the previous March at which she had addressed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Sherrod's remarks were condemned as racist by the NAACP, and US government officials demanded her resignation. Nonetheless, a review of her entire speech revealed that the excerpts were selectively edited and that her remarks, when understood in context, were about the importance of overcoming personal prejudices. The White House and NAACP officials later apologised for their criticisms, but this did not undo Shirley Sherrod's ordeal, which included character defamation and the loss of a significant position.

There is no doubt that racism is a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses numerous barriers that prevent people from experiencing dignity and equality because of their race or origin, and that it extends beyond thoughts, words, attitudes, and behaviours. It is extremely important to emphasize that racism should not be taken lightly, but it also shouldn’t be used as a weapon to manipulate individuals, groups, or situations.

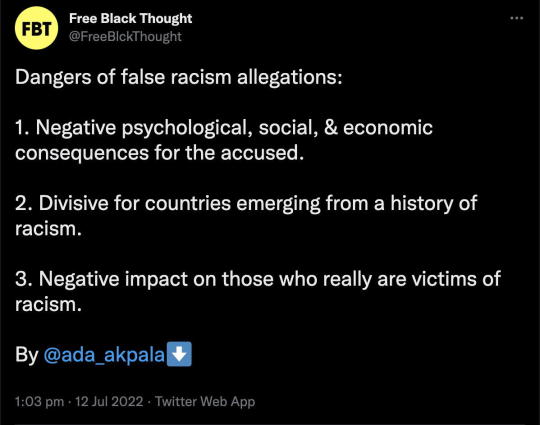

The dangers of false allegations of racism may be summarized thus:

False accusations of racism are hurtful, disrespectful, and an affront to a person's integrity and character. There are negative consequences for those accused and their family members, including emotional, physiological, psychological, social, and economic consequences. People may not simply be able to “move on,” and such a stigma can follow a person for the rest of their lives.

Unverified and false accusations of racism can be just as divisive in a country emerging from a history of racism as actual examples of racism. Such accusations may be detrimental to any projects aimed at fostering better race relations, re-establishing racial harmony, or progressing toward a future marked by racial equality.

When false accusations of racism are made, it negatively impacts those who really are victims of racism, as employers, office-holders, and the public at large may come to take their genuine accusations less seriously.

Racism is generally not tolerated in western societies. A genuine case of racist discrimination may result in civil, criminal, and financial penalties. Individuals should be free to report racist incidents without fear of reprisal. However, accusations must be made responsibly, as unfounded charges of racism can have a detrimental effect on individuals, communities, and society as a whole. Perhaps those who make false accusations should face repercussions as serious as those faced by genuine perpetrators of racist acts.

-

Ada Akpala is a writer and podcaster. Born in Nigeria, she now resides in the United Kingdom. She specialises in debunking sensationalist and inaccurate narratives about current and historical events, particularly in regard to race. She believes that we are the rulers of our own life and refuses to accept the victimisation culture that has been sold to so many, particularly black people. She focuses on creating content that combats the victim mentality and empowers black people and others.

Through her website, her writing, her Patreon, and her podcast Challenge The Narrative, as well as other social media platforms, Ada continues to challenge the established narrative on race, social justice, and current events.

==

Wilfred Reilly, frequent contributor to Free Black Thought, wrote a book specifically on, and titled, Hate Crime Hoax. Also, here’s a thread of over a hundred hoaxes, and an ongoing hashtag.

Apparently, they’re too busy in schools reading White Fragility to get around to The Boy Who Cried Wolf, or how false claims make people skeptical or distrustful of real occurrences, or diminished empathy due to becoming desensitized from even minor transgressions being blown into full scale scandals.

#Ada Akpala#Free Black Thought#sensationalism#clickbait#false accusations#racism#cancel culture#beautiful smile#wokeness as religion#cult of woke#woke activism#woke#wokeism#Hate Crime Hoax#long post#religion is a mental illness

8 notes

·

View notes