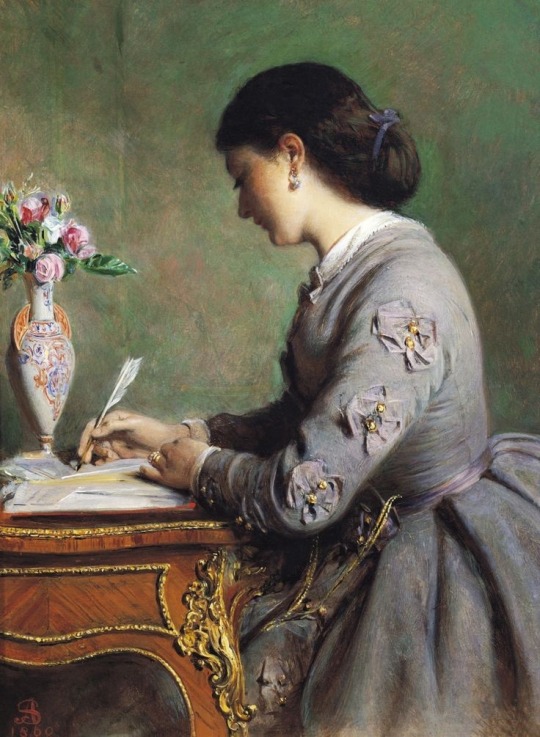

#abraham solomon 1824

Text

Dearest,

You told me you’d die if I turned down your marriage proposal. Here’s my answer:

Perish, then.

Never yours,

xx

#Victorian Woman Writing At Desk Painting#letters#love letter#this is so eloise bridgerton coded#rotnread#sanditon#victorian#la lettre#abraham solomon 1824#bridgerton#dearest

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Flight from Lucknow, 1858 by Abraham Solomon (English, 1824–1862)

921 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"I love another!" (1861). Abraham Solomon (British, 1824-1862). Oil on canvas.

The lady holds a crimson fan as she looks off to her left. There is little suggestion about the title. The composition is one suggesting a portrait.

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Flight from Lucknow

Abraham Solomon (1824–1862)

New Walk Museum & Art Gallery

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

ABRAHAM SOLOMON (BRITISH 1824-1862)

THE LION IN LOVE

Oil on board

Lyon and Turnbull

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Abraham Solomon (English, 1824-1862)

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

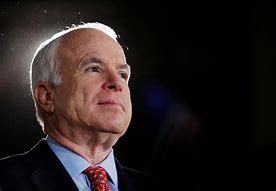

An American Hero

John McCain’s death was hardly a surprise. (The announcement at the end of last week that the decision had been made to discontinue medical treatment was certainly a clear enough indicator that he was coming to the end of his days.) I admit that the national wellspring of emotion the senator’s death brought forth from political fellow travelers and opponents alike, even leaving the President’s belated and begrudging response out of the mix, caught more than a bit off-guard. But it was Senator McCain’s posthumously-revealed wish that he be eulogized in a bipartisan manner both by Presidents George Bush and Obama that made the strongest impression on me. That these were the two men who the most consequentially thwarted his own White House aspirations—the former by defeating him for the Republican nomination in 2000 and the later by defeating him in the presidential election of 2008—also impressed me as a sign both of humility and magnanimity. The funeral is this Saturday, so I’m writing this before knowing what either man will say. But my guess is that both will rise to the occasion and pay homage to the man, not for holding this or that political view, but for having the moral stamina to move past his own defeats at both their hands to return to the Senate to continue his life of service to the American people.

Senator McCain was a complicated figure and hardly a paragon of invariable virtue. He himself characterized the decisions that led to his involvement in the “Keating Five” scandal the “worst mistake of my life.” (The fact that he made that comment after the Senate Ethics Committee determined that he had violated neither any U.S. law nor any specific rule of the Senate itself speaks volumes: here was a man who could have gone on to crow about his innocence—or at least about his non-guilt—yet who chose instead publicly to rue the appearance of impropriety that he feared would permanently attach itself to his name.) He owned up publicly to the fact that, at least in the context of his first marriage, he was not a model of marital fidelity. He was in many instances a party-line guy, going along with the plan to invade Iraq without stopping to notice that there was no actual evidence that Saddam Hussein possessed the weapons of mass destruction President Bush was so certain had to exist and in fact going so far as to refer on the floor of the Senate to Iraq as a “clear and present danger” to our country without pausing to ask himself how he could possibly know that in the absence of evidence that Iraq possessed actual weapons capable of reaching these shores.

On the other hand, his more than five years as a prisoner of the North Vietnamese—the beatings and the torture he endured, his refusal to accept the early release offered to him because the military Code of Conduct instructs prisoners to accept “neither parole nor special favors” from the enemy, his two years of solitary confinement—speaks for itself. (And the phony “confession” he signed at a particularly low point when his injuries had brought him to the point of considering suicide does nothing to change my mind about his heroism. In the end, he defied his captors in every meaningful way and was momentarily defeated by them only once.) As does his lifetime of service to the American people, one given real meaning specifically by the fact, as noted above, that he specifically did not abandon his commitment to serve merely because he was twice thwarted in his bid for the presidency and instead simply returned to the Senate, following the admirable example of Henry Clay, who lost the election of 1824 to John Quincy Adams and then, after serving as the latter’s Secretary of State for four years, returned to the Senate where he served as Senator from Kentucky for two non-consecutive terms and died, like McCain, in office.

But it was McCain’s posthumous letter to America that I want the most to write about today. Lots of literary masterworks have been published posthumously—all three of Kafka’s novels, for example, came out after he died in 1924—but most have been works that their authors for some reasons chose not to publish or were unable to get published in their lifetimes, not letters that their authors specifically wished to be publicized after they were gone from the world. That concept, however, is not unknown…and the concept of creating what is called an ethical will in which a legator bequeaths, not physical possessions or money, but values and moral principles to his or her heirs is actually a Jewish practice that has its roots in medieval Jewish times.

There are early examples of something like that even from biblical times—the Torah contains the pre-posthumous blessings that both Jacob and Moses left behind for their heirs to contemplate and to allow to guide them forward after Jacob and Moses were going to be gone from the world. (When the New Testament author of the Gospel of Matthew portrays Jesus as doing the same thing, in fact, it is probably part of an ancient author’s effort accurately to depict Jesus as a Jewish man doing what Jewish men in his day did.) But the custom reached its fullest flower in the Middle Ages—the oldest extant ethical will from that period was written by one Eleazar ben Isaac of Worms in Germany and dates back to c. 1050. After that, there are lots of examples, many of which were collected and published in two volumes back in 1926 by Israel Abrahams under the title Hebrew Ethical Wills and still available for a very reasonable price. There is even a modern guide to preparing such a will to leave to your own descendants in Jack Riemer’s Ethical Will and How To Prepare Them: A Guide for Sharing Your Values from Generation to Generation, published in a revised second edition just a few years ago by Jewish Lights in Woodstock, Vermont.

And it is in that specific vein that I found myself reading Senator McCain’s letter to the American people: not as last-minute effort to make a few final points, much less to get a few last jabs in at specific, if unnamed, opponents. (The Bible has a good example of that too in David’s last message to the world, which includes a hit-list of people David hopes Solomon will find a way to punish—or rather, to execute—after David is gone from the world and Solomon becomes king after him.) The McCain letter, neither vengeful nor angry, is not at all in that vein. Nor is it particularly soothing: it is, in every sense, the literary embodiment of its authors hopes for the nation he served and his last word on the course he hopes our nation will take in the years following his death. To read the full text, click here.

Senator McCain identifies the core values he feels should lie at the generative core of all American policy: a deep dedication to the concept of personal liberty, an equally serious dedication to the pursuit of justice for all, and, to quote directly, a level of “respect for the dignity of all people [that will bring the nation and its citizens] happiness more sublime than life’s fleeting pleasures.” Furthermore, he writes unambiguously that, in his opinion, “our identities and sense of worth [are never] circumscribed, but enlarged, by serving good causes bigger than ourselves.”

He characterizes our country as “a nation of ideals, not blood and soil.” And then he writes this: “We are blessed and are a blessing to humanity when we uphold and advance those ideals at home and in the world.” But his tone is not at all self-congratulatory. Indeed, the very next passage is the one that seems both the most filled with honor and trepidation: “We weaken our greatness when we confuse our patriotism with tribal rivalries that have sown resentment and hatred and violence in all the corners of the globe. We weaken it when we hide behind walls, rather than tear them down; when we doubt the power of our ideals, rather than trust them to be the great force for change they have always been.” It is hard to read those words without reference to the current administration, and I’m sure that McCain meant them to be understood in that specific way. But the overall tone of the letter is not preachy or political, but deeply encouraging and uplifting. His final words to his fellow Americans are also worth citing verbatim: “Do not despair of our present difficulties,” the senator writes from the very edge of his life. “We believe always in the promise and greatness of America because nothing is inevitable here. Americans never quit, we never surrender, we never hide from history. We make history. Farewell fellow Americans, God bless you, and God bless America.”

I disagreed with John McCain about a lot. We were not on the same side of any number of the most important issues facing our nation, but those divisions fall away easily as I read those final words. Here, I find myself thinking easily, was a true patriot—a flawed man in the way all of us must grapple with our own weaknesses and failings, but, at the end of the day, a principled man and a patriot. His death was a loss to the nation and particularly to the Senate, but the words he left behind will, I hope, guide us forward in a principled way that finds in debate and respectful disagreement the context in which the American people can find harmony in discord (which is, after all, a peculiarly and particularly American concept) and a focused national will to live up our own Founders’ ideals.

In the physical universe, energy derives from tension, friction, and stress. In the world of ideas, the same is true: Socrates knew that and developed a way of seeking the truth rooted not in placid agreement but in vigorous debate. That concept, almost more than anything else, is what shines through Senator McCain’s literary testament to the nation. He notes wryly, and surely correctly, that we are a nation composed of 325 million “opinionated, vociferous individuals.” But he also notes that when debate, even raucous public debate, is rooted in a shared love of country, the result is a stronger, more self-assured nation, not a weaker one enfeebled by conflicting opinions. I think that too…and my sadness at the senator’s passing is rooted, more than anything else, in that specific notion.

John McCain’s life was a gift to our country and his death, a tragedy. May he rest in peace, and may his memory be a source of ongoing blessing for his family and for his friends, and also for us all.

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Introduction to the Thinkers of Reform Judaism

By Josh Daniels, Former Research Intern

Growing up in a secular household, I had only a loose connection to the religion of Judaism. I attended Hebrew school twice a week for five years, and studied eight months independently for my bar mitzvah. I attended High Holiday services throughout my high school years, and ended up all but renounced my religious identity into college, where, ironically, I majored in religion and culture. I was always taught that social liberalism and commitment to universal human rights were sufficient markers of my Jewish identity. While I believe these traits are central to Judaism, they never gave me the drive to associate myself with any particularly Jewish values or practices. After all, given my relatively secular upbringing, why should I not just embody humanist values? It wasn’t until completing my undergraduate work in the study of religion that I realized that being intellectually fulfilled was a crucial part of a religious identity, and I found the Jewish intellectual tradition to be a rewarding avenue for articulating my own identity. It was hard to find a place to start however, considering my upbringing. As much as I’d learned while earning my degree, it was still hard for me to feel honest doing things like laying tefillin, especially since it was barely two years ago that I professed a fairly militant atheism.

Subsequently, I became particularly interested in the intellectual basis of Reform Judaism, which I saw as an opportunity to connect with both tradition and the modern world. I turned my attention to the archives at the Center for Jewish History, and through my research, found that the roots of the Judaism I was brought up in can be traced back to 19th century Germany. Germany at the time was a hotbed of ideas and had a century to react to the emergence of enlightened rationalism. Germany was churning out literary and philosophical giants such as Goethe and Hegel. Enlightenment thinking affected Jews and gentiles alike, as there arose many thinkers in Germany in the 1800’s whose ideas would have repercussions for Jews in Europe as well as America. As other secular or Reformish acquaintances of mine can attest, the real nuts and bolts of these early reformist ideas were absent from our Jewish education. Therefore, I will use my interest in the history of Reform Judaism in 19th century Germany and America to write a two-part series of blog posts hoping to give context for past attempts at reconciling Judaism with modern culture.

The Reform movement in 19th century Germany can be understood by highlighting a few of its prominent voices. Reform began in 19th century Germany despite the obstacles of ideological irrelevance in the wake of Enlightenment rationalism and political subjugation. Following the disintegration of the Holy Roman Empire, Germany consisted of a confederation of 39 different German-speaking states, all of which varied in their legislative influence on their Jewish communities.[1] Early on in the 1800s, reform was generally an urban phenomenon, mostly supported by members of the wealthier, educated classes.

One of the first attempts at a resurrection of Judaism culturally and politically was the formation of the Society for the Culture and Science of the Jews. The society was comprised of “a young generation of Jews educated at German Gymnasiums and universities [which] gathered from 1819 to 1824.”[2]

Despite the eventual conversion of almost all of the members to Christianity, one figure remained stalwart in his pursuit of the Society’s original goal. This man was Leopold Zunz (1794 – 1886). Often spoken of in the same breath as Moses Mendelssohn, Zunz was educated in the study of Classics and History at Berlin University.[3] He continued with the initial project of the Society, developing the Science of Judaism (Wissenshaft des Judentums), the precursor to what we would today consider the academic study of Judaism.

Jul Loewensohn, “Seated studio portrait of Leopold Zunz holding a book; Berlin Portraits Men,” Franz Rosenzweig Collection AR 3001, F AR 3001, Call # F3824N, Leo Baeck Institute. http://search.cjh.org/beta:CJH_SCOPE:cjh_digitool884570

This work helped to legitimized Judaism in the eyes of the educated classes of Germany and give Judaism a place in 19th century intellectual life. This work was of considerable importance towards the work of reform, considering the political situation at the time widely barred Jews from positions in academia, education, and government. Interestingly enough, however, “Zunz himself ultimately gave up hope for reform and confined himself to strictly historical researches, even adopting increasingly orthodox practices as he aged.”[4]

If Leopold Zunz represented the academic face of the reform movement, then Abraham Geiger and Samual Holdheim represented the theological face. Geiger, too, was engaged in the work of forming a science of Judaism, but did so by incorporating this work into his rabbinic career. Raised in an Orthodox family, he quickly entered secular university and began the work of reform.[5] Geiger was often at odds with more conservative members of his community, refusing to compromise by relinquishing “beth din (the Rabbinical Court) and the halakhic (legal) functions” of the Breslau Jewish community to Rabbi Solomon Tiktin, and refused a position as head of the Berlin Jewish Reform Congregation on the grounds that reform must not cause a schism in the Jewish community as a whole.[6]

“Seated studio portrait of Abraham Geiger, Portraits Men,” circa 1860, Abraham Geiger Collection AR 29 AR 29, call # F 2200, Leo Baeck Institute.http://search.cjh.org/beta:CJH_SCOPE:cjh_digitool891829

Geiger’s theology was based on the idea that Judaism evolved naturally over time, and that it was necessary to rely on these historical processes which worked over centuries for the work of reform. Geiger understood the history of Judaism to be divided into four different periods: Revelation, Tradition, Rigid Legalism, and finally Liberation and Criticism. In his own words, the task which confronts Judaism in this current stage was:

The loosening of the fetters of the previous period [Rigid Legalism] through the use of Reason and historical investigation – without interrupting the connection with the past. It is a period of attempts at self-renewal, of bringing the historical process into flux again, a period of criticism.[7]

Last, Samuel Holdheim, in contrast with Abraham Geiger, believed in a radical break with the past. Holdheim’s focus on a departure from tradition is at odds with his education as a “Talmudist of the old school.”[8] His theology was based on what he thought was a radical misunderstanding “of the events of the year 70 C.E., when the Jewish State and the Jerusalem Temple were destroyed. The task of the nineteenth-century Jew, therefore, was to get back to the Bible – or, at any rate, to those parts of the Bible which, according to Holdheim, were meant to have eternal validity.”[9] For Holdheim, the destruction of the Temple was due as much to the action of God as the actions of the Romans. This unique reading of history upended such concepts as Jewish racial purity, allowing mixed marriages, and observance of the laws associated with the ancient Jewish theocracy in Palestine.[10] These details of these two thinkers’ legacies are presented in several 20th century manuscripts which are accessible in the digital collections of the Center for Jewish History.

The waves that these thinkers made in the intellectual and theological worlds in Germany would first be exported to America in relatively insular German-Jewish communities know as Landsmanschaften, but given the absence of a deeply entrenched orthodox monolith in America, they would soon spread and develop in unique ways, which I will explore in the next entry.

Editor’s note: you can read more about the origins of the Reform movement in the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Reform_Religious) or Jewish Encyclopedia (http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12634-reform-judaism-from-the-point-of-view-of-the-reform-jew).

References

2008. German Confederation. August 21. https://www.britannica.com/topic/German-Confederation.

Hill, Harvey. 2007. "The Science of Reform: Abraham Geiger and the Wissenschaft des Judentum." Modern Judaism 329-349.

2004. "Leopold Zunz." Encyclopedia of World Biography.

Petuchowski, Jakob J. 1976. "Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim - Their Differences in Germany and Repercussions in America." New York City: Leo Baeck Institute, April 12. Hyperlink: http://search.cjh.org:1701/beta:CJH_SCOPE:CJH_ALEPH004613018

Wallach, Luitpold. 1958. "The Thoughts of Leopold Zunz." Center for Jewish History: Digital Archives. Hyperlink: http://search.cjh.org:1701/beta:CJH_SCOPE:CJH_ALEPH000202068

[1] (German Confederation 2008)

[2] (Wallach 1958)

[3] (Leopold Zunz 2004)

[4] (Hill 2007)

[5] Ibid.

[6] (Petuchowski 1976)

[7] (Petuchowski 1976)

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sunday Morning

Abraham Solomon (1824–1862)

The World of Glass

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Flight from Lucknow

Abraham Solomon (1824–1862)

New Walk Museum & Art Gallery

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Abraham Solomon, English, 1824-1862)

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sunday Morning

Abraham Solomon (1824–1862)

The World of Glass

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Flight from Lucknow

Abraham Solomon (1824–1862)

New Walk Museum & Art Gallery, Leicester Arts and Museums Service

107 notes

·

View notes