#acting as a suitably square stand-in for george

Text

also if i put an annoying version of a song in my playlists, it's there for a reason

#this is about#mel torme's#secret agent man#painting austin powers as out of touch#and seth macfarlane#'reprising'#“You Couldn't Be Cuter”#on my#the philadelphia story#playlist#acting as a suitably square stand-in for george#also#vic damone 'reprising'#“the things we did last summer”#in my playlist for#the apartment 1960#to represent the Fred MacMurray character

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Princess Amelia of Great Britain (10 June 1711 – 31 October 1786) was the second daughter of King George II of Great Britain & Queen Caroline.

.

Princess Amelia was born at Herrenhausen Palace, Hanover, Germany.

.

On 1 August 1714, Queen Anne of Great Britain died. Princess Amelia’s grandfather succeeded her to become George I of Great Britain, in accordance with the provisions of the Act of Settlement 1701. Amelia’s father, now heir apparent to the throne of Great Britain, was made Duke of Cornwall & created Prince of Wales on 27 September 1714. She moved to Great Britain with her family & they took up residence at St James’s Palace in London.

.

Amelia’s aunt Sophia Dorothea, Queen in Prussia suggested Amelia as a suitable wife for her son Frederick (later known as Frederick the Great) but his father Frederick William I of Prussia forced his son to marry Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern instead.

.

In 1751, Princess Amelia became ranger of Richmond Park after the death of Robert Walpole, 2nd Earl of Orford.

.

The Princess was generous in her gifts to charitable organisations. In 1760 she donated £100 to the society for educating poor orphans of clergymen (later the Clergy Orphan Corporation) to help pay for a school for 21 orphan daughters of clergymen of the Church of England. In 1783 she agreed to become an annual subscriber of £25 to the new County Infirmary in Northampton.

.

In 1761, Princess Amelia became the owner of Gunnersbury Estate, Middlesex, & at some time between 1777 & 1784, commissioned a bath house, extended as a folly by a subsequent owner of the land in the 19th century, which still stands today with a Grade II English Heritage listing & is known as Princess Amelia’s Bathhouse.

.

She also owned a property in Cavendish Square, Soho, London, where she died unmarried on 31 October 1786, at which time she was the last surviving child of King George II & Queen Caroline. A miniature of Prince Frederick of Prussia was found on her body.

.

Amelia Island in Florida, United States, is named for her, as is Amelia County in Virginia, United States.

.

.

.

#Princessamelia #GreatBritain #Houseofhanover #RoyalHistory #royalfamily #BritishMonarchy (at Hanover, Germany)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBRRifAjkRV/?igshid=17p8hnlqyq1ir

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Wishes:

Say Her Name

Wednesday, September 14, 2020

This week, scholars and citizens will gather on Zoom (a platform not without its own controversy) to ponder the renaming of Lane County as part of the UO Department of History’s History Pub. Is it right to recalibrate our place names? What are we trying to communicate to future Oregonians? Do historical lives matter? And what is in a name?

The revision of popular history can be a force for good. Old wolves may be stripped of their wool and monsters given fresh charm. History is pressed with moveable type and leaves ample margins for new scribblings.

Such is our case today. Speeches – both great and small – begin with solemn invocations of the occupied, unhoused, and enjailed. Shade is thrown upon the statues our grandpas dedicated to their heroes. What was once Denali is now again, and McKinley is ground down into the muck under a glacier.

In that spirit let us Google our own map. At our city’s center and cleaving it in two is Washington-Jefferson Park, a sparking jewel in Eugene’s public crown. At one end, a strange monument welcomes visitors – a red giant that like many works of public art is both touchable and shape-shifting. From one vantage point, it recalls a child’s toy; from another it might be a corporate logo, a brand standing in front of a Fortune 500 campus. In a pinch and with a tarp, it may be turned into shelter for one who is unhoused.

At the other end, one finds a skate park, and that side of the W-J reflects some of our nation’s most persistent preoccupations: popular sport, youth culture, and public inebriation sans shame or temper.

A lovely park indeed, but perhaps a misfortune to be named for Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson - those two proud and rebellious Virginians, those two treacherous and super-rich slavers. O, that the W-J should be so popular with the unemployed and unemployable, yet be named for those two whose families were anointed in new world plunder and who multiplied it by the whip-scarred backs of the enslaved!

Those two historical men; those two questionable characters. One of them – a mediocre war chief born richer than Croesus himself and made richer still by the toil of humans worked as chattel. And the other man, TJ Maxx, the proto-metro and the gentleman farmer. So eloquent in his assertions of religious freedom to Virginia’s colonial legislature, so disgusting in his business methods. Fathers of a great nation? Perhaps, for history tells us that Abraham of Canaan also held slaves.

Was Abraham a traitor as well, I wonder. Let’s not kid ourselves: had a couple of battles gone slightly differently, Wash and TJ would’ve been strung up in Alexandria and Charlottesville squares. And this is to say nothing of President James Monroe whose plantation was known to be cruel to an extreme or of the genocidal acts of Generals-cum-Presidents William Henry Harrison and Andrew Jackson.

Forgive me when I don’t salute these great and ignoble assholes.

Let’s find new names for these parks, for these streets, and for this county and fast, for the old ones drip with blood.

But in our haste to remix the past, let us remember that it’s not enough to just delete the names of dead racists; justice demands healing, which begins with understanding the wound and what caused it.

Let me close this dark and bruised essay by invoking the name of one of the victims of Mr Jefferson’s malice: Ms Sally Hemmings. She was a slave bound to Mr Jefferson’s plantation and shackled to his will. Much has been written about Ms Hemmings and her relationship to her master; some have even framed it as a countryside romance suitable of a Brontë novel. But make no mistake. Despite whatever favor he granted her, despite whatever fairytale our common mythology spreads, and despite the surely beloved offspring she bore for him, their sex was not consensual. No slave can consent, and any sex between master and slave is necessarily rape. So when we say the names of victims of violence and white supremacy, say her name as well.

Say their names: Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Sally Hemmings.

Say her name: Sally Hemmings.

Best wishes,

Robert Johnson Patterson

PS – While many enjoyed last week’s ribaldry, one reader – the esteemed Mr Daniel Borson – writes in to remind that Eugene’s lack of public restroomage is anything but a laughing matter.

He writes, “As someone who lives with Crohn's Disease, easy and safe access to toilet facilities is crucial to my well-being while out and about town. While Oregon has an ‘Ally's Law’ that guarantees people with medical conditions (such as Crohn's and colitis) access to private toilets in businesses with at least 3 employees present, everyone should have such access.”

I agree wholly, especially after learning more about Ally’s Law at www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org. Thank you, Mr Borson, for reading and for feeding back

©2020, Robert Patterson, All Rights Reserved

#best wishes#robert patterson#say her name#Eugene#george washington#thomas jefferson#virginia#sally hemmings#black lives matter#revisionist history

1 note

·

View note

Text

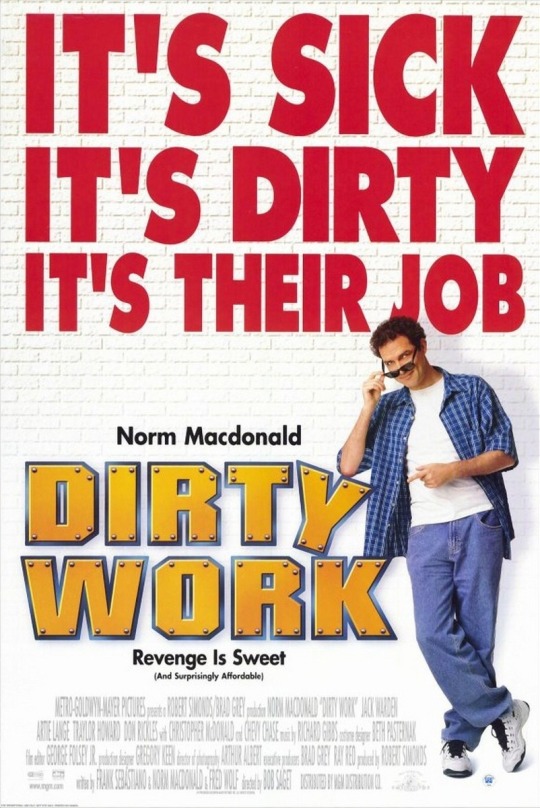

Favorites : Dirty Work (1998)

Earlier this week, I received the tragic news of Norm Macdonald’s passing due to complications from Cancer. Macdonald had always been a polarizing comedic enigma that clearly split those who became familiar with him into camps of love and hate, but it was that enigmatic persona that made it no surprise that his fight with Cancer had gone on for years with almost no public knowledge of it. The news hit me extremely hard, as his deadpan style, cavalier attitude and abstract anti-authority approach all spoke to me, so as a tool for immediate grieving I went to an old standby that’s helped me laugh my way out of many depressing times : Dirty Work.

youtube

Dirty Work predates the phenomenon of the Line-O-Rama approach to comedic filmmaking, joining fellow 1998 release club member Half-Baked as harbingers of the style that films like Old School ushered in and made the comedic standard. This approach works perfectly for Dirty Work, as the narrative is not the star of this film. With an ensemble comedic cast at your disposal like the one on hand, all you really need is a story about as complex as the one presented here in order to provide enough dramatic tension to count : dying father, estranged brothers, questionable business for quick money and corrupt businessman form the foundational square that makes up Dirty Work‘s narrative. From there, the green light is given to a decently-sized gathering of comedic mavericks to work off of one another as they mix different shades of non-traditional and traditional comedic chops that span at least three generations of funny people.

With so much humor on display, not to mention the shadow of Norm Macdonald’s death looming over this viewing experience, it really rang out to me just how bittersweet this movie has suddenly become. The film is still incredibly funny (at least to those who buy in to the Norm Macdonald and Bob Saget schools of comedy), but seeing comedic actors and talents like Jack Warden, Don Rickles, Chris Farley and Gary Coleman reminds us of the impermanence of life. On top of this, seeing faces like Artie Lange, Chevy Chase and Ken Norton in the mix remind us of how rocky the journey through life can be, regardless of your financial stature or prominence of star power. While Norm Macdonald may not have ever found the standard “traditional” footing that comes with a comedy career (whatever that may be), it’s nice to know that a film like Dirty Work not only was able to achieve the comedic cult status that it has, but that he was able to include so many friends and influences within the creative expression.

While this film wasn’t necessarily made to be a technically proficient masterpiece, one thing it does well is understand itself in terms of mood, tone and pacing, and these aspects are what allows the comedy to be carried through with little to no resistance, giving us as viewers the chance to turn off our analytical side and embrace a bit of pure, unadulterated silliness. There are tons of setups and callbacks sprinkled throughout the run of the film, be they immediate or separated and doled out through different acts. The film is not afraid to wallow in the muck and mire of low brow, childish comedy, but there are enough witty moments and completely out of left field references to give the comedy the feeling of covering some sort of spectrum. It is also impressive how well the abstractness of Norm Macdonald and Chevy Chase can work in connection with the one-liner styles of Jack Warden and Don Rickles, not to mention the raw energy and brooding darkness that comes with the comedy of Chris Farley and Artie Lange... surprisingly, nobody feels out of place or inappropriately used, with everyone getting plenty of opportunity to shine. While the film is considered more of a cult classic than a beloved one, the film is also highly quotable.

Part of the Norm Macdonald enjoyment factor was watching him insert his oddness into pre-conditioned structures, so watching him warp the structure of a rom-com and buddy comedy to a form that fits his approach is as inspiring as it is entertaining. Balancing this against the gruff, workingman’s approach that Artie Lange is known for makes their pairing a perfect update to the Odd Couple dynamic made famous in the past. Jack Warden brings an aged and unembarrassed twist to the Lange approach as a fatherly figure, standing out as both intimidating and endearing, with the common element being their extremity. Traylor Howard holds her own in the comedically abstract whirlwind that Macdonald and company create, infusing enough charm and affection to sell interest between Macdonald and herself (which is suitable, as I doubt magnetic attraction was not the aim). Chevy Chase does what he does best, dropping non-sequiturs and dry punchlines like cinder blocks to great comedic effect. Chris Farley brings his unhinged energy to a satellite role, while Christopher McDonald leans into the same energy that made his portrayal of Shooter McGavin so infamous. Cameo appearances by Don Rickles, Rebecca Romijn, John Goodman, Adam Sandler, Gary Coleman, Ken Norton and many more comedic cohorts all bring tons of laughs to the table.

There will probably never be another comedic mind quite like that of Norm Macdonald. Perhaps we will get the abstract approach of Andy Kaufman, the inherent deductive reasoning of George Carlin, the brutal honesty of Lenny Bruce and the free will of Robin Williams in small packages, but likely never in the same formula that birthed the polarizing funniness of Macdonald. If you’ve not seen Dirty Work and you’re currently feeling the pain of loss connected to Norm Macdonald’s passing, jump on HBOMax and give it a watch while it’s still streaming.

#ChiefDoomsday#DOOMonFILM#BobSaget#DirtyWork#NormMacdonald#ArtieLange#JackWarden#TraylorHoward#ChrisFarley#ChristopherMcDonald#ChevyChase#DonRickles#RebeccaRomijn#JohnGoodman#AdamSandler#GaryColeman#GeorgeChuvalo#KenNorton#DavidKoechner#JimDowney#FredWolf#KevinFarley#AnthonyJMifsud#GordMartineau

0 notes

Text

Arplis - News: How a Dangerous, Exploitative Railroad Industry Created J.P

Morgan’s Fortune

Before the Jupiter of Roman myth could become king of the sky and thunder, he had to overthrow his father in a mighty battle. Not so for the Jupiter of Wall Street. J.P. Morgan had trusted his father to set him on the right path and steer his career, and even when his father was overbearing, Morgan never mounted a challenge. The creator of the biggest companies the world had ever known was, himself, very much the creation of paternal influence. The young Morgan, once established, proved instinctively suited to the times in which he lived. It was an era of raucous, unfettered competition: chaotic capitalism that he would try to order.

John Pierpont Morgan was born in April 1837 into a wealthy family and inherited his father’s European connections and tastes, along with part of his fortune. He grew up in the river town of Hartford, Connecticut, a thriving center of trade and, by necessity, insurance. John preferred to be called Pierpont, though schoolmates nicknamed him Pip. As the eldest of five and the only son to live past childhood, he was also entitled to a lifetime of moral education and cautionary advice from his father, Junius, and continual redirection when he strayed. His mother, Juliet, was troubled by depression and lived at a sullen remove from the family. She once scolded Pierpont for writing home too often.

Pierpont suffered physically as a child. For months before and after his first birthday he was so frequently overcome by convulsions that his parents feared he might not survive. In adolescence, he missed school because of sore throats, headaches, earaches, boils on his face, and ulcerated sores on his lips. When Pierpont was fifteen, his father sent him to the Portuguese Azores, hoping the warm climate would cure his rheumatic fever. He stayed there, with only a family friend and a doctor to check on him, for four months.

Junius moved Pierpont into and out of boarding and public schools—transferring him nine times in thirteen years—without explanation. Pierpont didn’t complain. He was an indifferent student in most subjects other than math: “full of animal life and spirits . . . and not renowned as a scholar,” one classmate later described him. Pierpont sought order in the only ways he could. He collected and organized, first stamps and autographs of Episcopal bishops and then his own accounts. When he traveled, he noted the latitude of his destination and the time of his arrival, and wherever he was he kept a leather-bound journal of daily expenses: paper and postage, ice cream and strawberries, beaver hats, silk gloves, buggy rides, opera tickets.

In 1854, the family moved to London after Junius accepted a partnership in the British office of the premier American private bank, run by George Peabody, to help direct European capital to the United States. Junius would one day take over, and he hoped Pierpont would do so after him: a Morgan dynasty.

Pierpont was seventeen. He had graduated from the English High School of Boston, which specialized in math, and was eager to begin his career. But Junius wanted him to learn French and German and enrolled him at a school near Lake Geneva. Pierpont considered the accommodations too sparse and the studies uninteresting. “Adapts himself very slowly . . . Answers back . . . sulky,” the headmaster wrote of the new student. Outside the classroom, he was happier. He enjoyed the camaraderie of the other American students and soon made himself their unofficial leader. If they went on an expedition, he planned it; if they hosted a party, he arranged it. Taking charge would become a lifetime impulse—one, though, that Pierpont would have to curb around his father for years.

At the University of Göttingen, where Junius sent him next, Pierpont was such an exceptional math student that his professor thought he could one day join the academy. Neither Morgan considered that a suitable career path.

The possibilities for making a name and a fortune were so extravagant and, initially, the oversight so minimal that railroads naturally attracted uninformed investors and unscrupulous brokers.

In 1857, Junius arranged a first job for Pierpont, as an unpaid clerk at a New York investment firm linked to his. It specialized in financing the railroads eager builders were haphazardly laying across America. The industry was all raw hustle. Lines overlapped each other or ran parallel, creating a tangle of tracks of different widths and trains running on different time clocks. Operators constructed as much as they could afford and then stopped, requiring passengers to regularly switch cars to complete their trips. When Abraham Lincoln traveled from Springfield, Illinois, to New York in 1860, he had to change trains four times (and take two ferries) over the course of four days.

Pierpont moved into the city’s most fashionable neighborhood, around Union Square, and lived comfortably on the two hundred dollars his father sent every month. In exchange, Junius expected Pierpont to ignore the chance to make a quick profit in the stock market. But there were many chances. When Pierpont bought shares in a steamship company benefiting from a large government subsidy to carry mail, Junius disapproved. “Bring your mind quietly down to the regular details of business,” he advised. Pierpont was to become a banker beyond reproach, trusted to handle other people’s money and not speculate with his own. “Never under any circumstances do an act which could be called in question if known to the whole world,” Junius wrote. Integrity would give the Morgans a competitive edge in America.

After Pierpont served as an apprentice for two years, Junius decided his son should resign. The firm’s partners praised their clerk’s “untiring industry,” and suggested he would be even more successful if he approached colleagues with “suavity and gentle bearing” instead of impatience. Pierpont, recipient of regular job evaluations from his father, graciously accepted this one.

He may also have been distracted. He had fallen for Amelia Sturges, known as Memie, a bright, well-read, high-spirited member of his social circle. They planned a rendezvous in Europe that autumn. On their way home, Pierpont moped when the ship’s captain seemed to take an interest in Memie. “One of my friends very blue all day. Disappeared from dinner very suddenly,” she wrote in her diary. “No cry of Man Overboard so concluded he was all right.” They were engaged in August 1860.

That November, Abraham Lincoln was elected president, and within half a year, the North and the South were at war. But Pierpont was happily preoccupied by Memie and the autumn wedding they were planning. He didn’t even mind that Junius hadn’t found the right firm for him yet. He tried some freelance work instead, helping to finance a controversial deal to supply the ill-prepared Union Army with five thousand Hall carbines, refurbished rifles left over at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848. Pierpont didn’t see the sale through but earned a generous commission for his efforts. A congressional committee called the entire transaction profiteering. The Supreme Court didn’t. It ruled the government had to pay as promised, twenty-two dollars for each altered rifle originally priced at $3.50. More troubling for Pierpont, Memie had taken ill with a severe, lingering cough. A week before the wedding, she was still unwell, vomiting and sleeping badly. She looked so thin that she decided to keep a veil over her face during the entire marriage ceremony. It took place in her parents’ Manhattan home at ten in the morning on October 7, 1861, in front of a small group of friends and family. Two days later, the newlyweds left New York for a European honeymoon.

The couple consulted specialists in Paris, who determined Memie had tuberculosis: cause unknown, cure undiscovered. Pierpont didn’t share the diagnosis with Memie, only the doctors’ recommendations, which included rest and warm air as well as turpentine pellets, cod liver oil, and donkey’s milk. Nothing helped. Not the roses and geraniums he brought or the apples he roasted, not the nightingales and canaries that sang in their hotel room. By December, Memie was too weak to stand. Pierpont asked his mother-in-law to cross the Atlantic as soon as she could and meet them in Nice. Memie’s father had come to regard Pierpont as a hypochondriac and thought he might be exaggerating the danger of her condition, but he sent Memie’s mother and brother over in January.

After they arrived, Pierpont relented to pressure from Junius and traveled to London to discuss business. By the time he could wrest himself away ten days later, Memie was much worse. She threw her arms around him when he arrived at her bedside, and just that took all her energy.

Morgan’s days came to be consumed by the railroads: a sprawling, overextended, indebted industry that was growing with careless speed and changing everything it touched.

Pierpont stayed close to her throughout the day. At eight thirty the next morning, he was called from his bedroom to hers. She died moments later. They had been married four months.

Back in New York, Pierpont formed a business partnership with his cousin and hoped “constant occupation” would keep him from dwelling on his grief. His loss hung on him, and so did his regret. No one blamed Pierpont for failing to save Memie—except for Pierpont himself. His gaze intensified, his hazel eyes seemed to darken, and his constitution weakened again. In the days following her funeral that spring, sores appeared all over his body, a mild form of smallpox, and once he recovered, headaches would sometimes overcome him. Throughout those months, and for many afterward, Pierpont stayed in touch with Memie’s parents and held on to her Bible. He acquired his first oil painting, of a fragile young woman, and hung it over the mantel in his library. He read poetry about lost love. The Civil War provided opportunities to trade foreign exchange and new government bonds, and, eventually, offer railroad financing.

But Pierpont exhausted himself and suffered new breakdowns of his nerves and body. “I am never satisfied until I either do everything myself or personally supervise every thing done even to an entry in the books,” he wrote to his father in September 1862. Those periods of helplessness were also the only times when the pressure from Junius let up, and Pierpont was forced to relax his own exacting standards. His vigor returned by the next summer, and on behalf of his father’s firm and his own, he was issuing short-term loans, brokering securities, and financing commodity trades. That year, he, like many men of means, paid a substitute three hundred dollars to take his place in the army. He went on to earn fifty-eight thousand dollars from his firm. Lincoln’s salary that year was twenty-five thousand dollars.

Pierpont supplemented his salary by manipulating the market for gold. He and a friend created an artificial shortage by shipping gold they had bought on credit to London. When prices in America went up, they sold, and each took a profit of sixty-six thousand dollars. Other Wall Street brokers admired the scheme. Junius was furious, believing Pierpont had been reckless and greedy and had violated the Morgan code of conduct. Junius at first threatened to cut professional ties, then decided instead to arrange for a senior partner to join his son in New York. For much of the next two decades, Pierpont would have to be the junior.

In March 1865, as the world watched the war draw down, Pierpont proposed to Frances Louisa Tracy. She was twenty-two; he was close to twenty-eight. They lived in the same neighborhood, worshipped at the same Episcopal church, occupied equally comfortable positions in Manhattan’s social hierarchy. Fanny, as she was called, enjoyed attending the opera and concerts with him, and he enjoyed the idea of being married again. The nation was still in mourning for the slain President Lincoln when, on May 31, Pierpont and Fanny wed at St. George’s Church. She gave birth to their first child, Louisa, nine months and ten days later.

They had three more children over the next seven years: John Pierpont Jr. (who always went by Jack), Juliet, and Anne. Fanny, too, could be overwhelmed by melancholy, but while Pierpont craved work and social distractions, she needed quiet. She wanted to move to the suburbs of New Jersey. He told her he couldn’t survive there. Eventually, they began to create separate lives for themselves in different homes, cities, sometimes continents.

By 1871, a new national optimism had taken hold, a confidence in an expanding economy of steel and oil and electric power, of perseverance and luck. It was a time that Mark Twain would soon call the Gilded Age. Americans paid to hear a lecture titled “The Aristocracy of the Dollar,” and Walt Whitman was paid one hundred dollars to compose “Song of the Exposition” in celebration of the country’s industrial strength. John Sherman, a Republican senator from Ohio, wrote to his brother, General William Tecumseh Sherman, of how the wealthy “talk of millions as confidently as formerly of thousands.” With the massively popular serialized novel Ragged Dick, Horatio Alger’s fictions of social mobility made it seem as if anyone who worked hard enough could elevate themselves. Personal thrift for some; stock market speculation for others.

Pierpont grew weary amid this thronging hopefulness. He was so strained by his dealmaking and worn out by his perfectionism that he wanted to retire at age thirty-three. His father refused to let him. Instead, Junius allowed Pierpont to take his family to Europe for a year.

When he returned, Pierpont started a new partnership with Anthony Drexel, head of a prominent Philadelphia banking family. Drexel, who was twelve years older than Pierpont, had a reputation sound enough to satisfy Junius. Drexel’s name came first at the firm, and Junius still held sway, but Pierpont was permitted to manage the New York office. He had more authority than he was used to, which allowed him to reveal his vaulting ambition. But Drexel, Morgan & Company it was for the next two decades, until Drexel died and Morgan renamed the firm.

Drexel set Morgan up nicely. He paid more than $900,000, in gold, for several lots on Wall Street. Number 23 sat at the intersection with Broad Street across from the New York Stock Exchange, and when Drexel purchased the land in 1872, no comparable property in any city in the world had been sold for more. The six-story building was known simply as “the Corner.” It was constructed with white Vermont marble, a grand mansard roof, and statues representing Europe and America above the main entrance. Its interior was finished in black walnut and mahogany, with marble floors, steam heat, and, after Morgan financed Edison’s electric company, six hundred lightbulbs. It was among the first buildings to be illuminated entirely by electricity. The firm rented out office space on the upper floors, and several railroad companies relocated their headquarters to take up residence there.

Morgan’s days came to be consumed by the railroads: a sprawling, overextended, indebted industry that was growing with careless speed and changing everything it touched. It absorbed more money, mostly from European investors, than any enterprise before and more natural resources than any other in America. Some 170 million acres of the country’s public land would become the private property of the railroads, given, not sold, to them. Lincoln hoped transcontinental railroads would be a nation-building project after the Civil War. For every mile of track laid, the government awarded companies 12,800 acres, along with a bonus: any coal or iron underground.

Railroads relied on the labor of Chinese immigrants in the West and Irish, Italian, and Greek immigrants in the East. They first brought Scandinavian immigrants to the Midwest, then Eastern Europeans. The cars carried citrus, timber, cotton, grain, gas, pigs, cattle, mail, and mail order catalogs across the country. They advocated for public schools to create a ready supply of clerks. Their need for precise train schedules helped standardize time itself.

Railroads altered the geography of opportunity. Their lines determined which towns became impoverished and which prospered. Billings, Cheyenne, Tacoma, Reno: these were not places that would have otherwise attracted populations of any size. The companies’ shipping rates, adjusted as owners saw fit, influenced the economics of small and big businesses. They handed out free passes to the politicians they hoped to sway. The railroads had a greater impact on people’s well-being than the government, and though Americans might not have liked that feeling of dependence, they had to live with it.

The possibilities for making a name and a fortune were so extravagant and, initially, the oversight so minimal that railroads naturally attracted uninformed investors and unscrupulous brokers to take advantage of them. They sold overpriced stocks and bonds to build lines with little prospect of success. Owners bribed politicians, bought off journalists, pushed aside Native American tribes, and dismissed environmental concerns as a matter of business.

Safety precautions were especially lax. Tens of thousands of railroad employees died or ended up mangled every year. “It was taken as a matter of course that the men must of necessity be maimed and killed,” wrote one railroad commissioner hoping to improve that record. Many of the railroads were built cheaply. Repairs weren’t timely. Lines ran in both directions on single tracks with rudimentary signal systems. Men had to climb on top of freight cars traveling 20 miles an hour to activate the hand brakes. Then they had to jump to the next car to do it again. If the train lurched, they could tumble to the ground. A low overhead bridge could knock them out. Men linked or unlinked cars by maneuvering in between, and inevitably some fell underneath.

In Winona, Minnesota, one day in February 1873, E. Campbell, the engineer on a passenger train, didn’t sound the alarm or apply the brakes when he saw a freight train on the tracks. The trains collided and both engines were smashed. Campbell jumped off in time. But J. C. Reilly, the baggage master, was badly burned when he fell onto the stove.

Conductor Arthur Lindsley lost his right arm after he was run over by a freight train at Janesville, Wisconsin, in April of the same year. Fireman R. Brown was killed in an accident at Vincent Station, Ohio, in July. In November, an employee named Amandas Hagerty was bent over the track repairing a switch at the Mauch Chunk station in Pennsylvania on a Wednesday afternoon. Maybe he heard the No. 4 passenger train backing in. Maybe he didn’t. But he didn’t have time to escape. Two wheels severed his body, and he died immediately.

The mere fact of working on the railroads shortened a man’s life expectancy. But if a brakeman or switchman or fireman proved himself and managed to avoid injury, he figured his job was secure.

Then, in 1873, one of the Morgans’ most prominent American rivals, Jay Cooke and Company, went bankrupt. Cooke, who had assembled his own army of agents to sell government bonds across the Union, was known as the financier of the Civil War. Afterward, he turned his considerable talents for promotion to the railroads. He would finance the construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad, meant to traverse the sparse, frigid lands of Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho, and Washington. Cooke promised a temperate climate, tropical vegetation, and a broad fertile belt “within the parallels of latitude which in Europe, Asia, and America embrace the most enlightened, creative, conquering, and progressive populations.” Instead, the land through which the Northern Pacific would pass was disparagingly called “Jay Cooke’s banana belt.” When wheat prices fell and farmers failed, trouble followed for Cooke. He couldn’t find enough buyers for one hundred million dollars’ worth of bonds. His firm went under, and the shock set off a series of bank failures that caused a panic on Wall Street and shut down the stock exchange for ten days.

Banks collapsed. Businesses failed. People lost their savings and their homes. By 1876, an uncounted number of adults were unemployed and underemployed, and tens of thousands roamed the country looking for food and work, sleeping in police stations when they could. The railroad men’s expectation of lifetime positions was revealed as empty hope. Some tried to leave the country. Two hundred or so accepted work building a railroad in Brazil. After their ship sank off the coast of North Carolina, hundreds of other desperate men applied for the jobs.

The Long Depression ground on for six years, contributing to an international financial crisis. European investors lost six hundred million dollars in American railroad stocks. It was a scare for the Morgans. Pierpont’s health faltered; he stopped exercising. Friction in the office sank him lower. Amid the dreariness, he tried again to retire in 1876, and, failing to secure permission from his father, left for a summer abroad that lasted until the following spring.

In July 1877, firemen and brakemen in Martinsburg, West Virginia, walked off the job in a spontaneous protest against the second wage cut in a year by the Baltimore & Ohio. Railway workers across the country joined them, stopping train traffic in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Chicago. They took control of switches, uncoupled rail cars, blocked trains, and set fire to railway buildings and bridges. Breweries and flour mills idled in St. Louis. Banks closed. Bridges burned.

In Pennsylvania, anthracite coal miners stopped digging. The railroads oversaw the mines and transported the coal. “Bread is what we are after and, sir, we have not had enough to keep our families from suffering say for nearly two years, and it is written that man should not live by bread alone,” one miner told the governor after being granted an interview in his private rail car—an unusual gesture of conciliation. But to no avail. Coal fields flooded and steel mills shut down.

Executives called on state officials for help. “There are two military companies at Martinsburg, armed and supplied with ammunition,” the governor of West Virginia replied to a Baltimore & Ohio vice president. But the local militia sympathized with the strikers. The governor called for federal intervention. “Please send in addition 100 men and two pieces of artillery,” he said in a telegram to the secretary of war.

The military campaign against Native Americans out west had sapped the Army’s coffers. Pierpont—whose firm held almost a million dollars of the Baltimore & Ohio’s short-term debt, while his father’s firm held another four million—offered to lend the federal government money to pay Army officers. The military moved into the cities, subdued the streets, and took control of the railroads and mines.

Pierpont assessed the credit risk. The Baltimore & Ohio’s losses required it to take on longer-term debt, which he knew would be a hard sell. Instead, he and Junius organized a banking syndicate to buy and hold the railroad’s bonds until circumstances changed. “Affairs for a time looked very critical and gave me much anxiety for many days and nights,” Pierpont told one of his father’s partners that August. It took years to sell all the bonds.

More than one hundred thousand workers around the country protested that summer of 1877. One hundred were killed and a thousand jailed. The public called it a rebellion; the government called it a riot. Later, it came to be known as the Great Upheaval.

In November, the country’s business and political elite set aside any lingering worries and came together at Delmonico’s Restaurant on Fifth Avenue to commend Junius for upholding the nation’s credit and “honor in the commercial capital of the world.” That capital was still London. The Morgans had become trusted advisers on both sides of the Atlantic, just as Junius had wanted. “A kind Providence has been very bountiful to us,” Junius said. “And under this guidance, the future is in our own hands.”

By the 1880s, business was humming again. The railroads comprised 80 percent of the listings on the New York Stock Exchange, brought in revenue about two times as great as the federal government’s, and added an average of seven thousand miles of track each year. They couldn’t all survive. But in their construction, promotion, and dissolution, they provided possibilities of all kinds. When William Vanderbilt wanted to secretly sell shares in the railroad his father, Cornelius, had built, Pierpont helped. Vanderbilt’s nearly exclusive ownership of the New York Central was becoming a liability, likely to provoke either new restrictions or taxes. He wanted to avoid both. Pierpont persuaded the British investors he and his father had cultivated to buy the shares and give him the voting power, which meant he could take a seat on the company’s board. He made half a million dollars in the process.

Pierpont’s firm had also made a killing easing the Long Island Railroad into and out of bankruptcy. His most conspicuous deal involved helping sell forty million dollars’ worth of Northern Pacific bonds in November 1880 so the company could lay down the final sixteen hundred miles of track required to reach the Pacific. It was the largest railroad bond offering in the country to date. Before the Panic of 1873, Jay Cooke’s aggressive salesmanship on behalf of the Northern Pacific had helped inflate the railroad bubble in the first place. Now Pierpont was reaping the rewards. The Northern Pacific would become pivotal to his ambitions—and his conflict with Roosevelt.

New York thrived too. Plans were set for the city’s most expansive apartment cooperative, a twelve-story redbrick Victorian Gothic pile on West Twenty-Third Street, with the top floor given over to artists’ studios. It would be the tallest building in the city. (Later, it would become the Chelsea Hotel.) The Brooklyn Bridge was almost complete after more than a decade under construction. Luxury department stores opened on Broadway, and carriages lined the streets of Ladies’ Mile.

Morgan’s share of his firm’s profits was eight hundred thousand dollars in 1880 and nearly one million the year after. He acquired his own notable address at 219 Madison Avenue, in a neighborhood where he already knew everyone. The brownstone was renovated to his uncompromising requirements: walnut doors at a new entrance on Thirty-Sixth Street; a stainedglass dome and stained-glass sliding panels opening onto the front hall; twin white oak staircases; a two-story safe in the butler’s pantry. The mansion was the first private residence to rely completely on Edison’s lights. Morgan installed a private telegraph wire connecting the house to 23 Wall Street. The telegraph was meant for business but proved useful at other times, including when he accidentally locked the family’s French poodle in the wine cellar and carried off the key.

The drawing room took up the entire west side of the house, with a ceiling painted to look like a mosaic. The library was decorated with octagonal panels of allegorical figures representing History and Poetry, painted by Christian Herter, the premier interior designer of the time. On the shelves were Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy from 1621, a copy of the John Eliot Indian Bible from 1663, sixty-six volumes on Napoleon and His Generals, and hundreds of other leather-bound treasures. Morgan wanted the best of everything—“Nothing but masterpieces,” a friend said. “And he can afford to have them.”

Morgan devised a plan whose legality might have made others hesitate, but he was willing to take the risk.

That year, Morgan also purchased his first yacht, Corsair. It was a 185-foot black-hulled steamer, the largest and most technically sophisticated in the country. His close friends began to call themselves the Corsair Club and Morgan himself the Commodore. During summer weekends, he would steam up the Hudson to Cragston, the country estate near West Point where his family lived in the hot months. There he maintained kennels for his show dogs, collies mostly; he liked to give their puppies as gifts, but only to those he held in the highest regard. On Sunday evenings he and his guests slept aboard the yacht so they could get under way at daybreak. By the time they arrived on the New Jersey side of the Hudson, a hearty breakfast was ready. As they finished, around nine, a launch pulled up alongside Corsair and everyone went ashore. Morgan’s carriage waited to take him to 23 Wall Street.

He worked on the ground floor, in an office with glass walls, at a large desk, plain and businesslike. He kept the door open. Sometimes he could be seen swinging in his pivot chair, if anybody dared look. He usually had a long cigar, banded in gold, often unlit in his mouth or in his left hand. His Chesterfield topcoat and silver-tipped mahogany walking stick were set aside. Mr. Morgan, as everyone called him, attended to matters large and small: the daily flow of cash and accumulation of debt, the stream of potential dealmakers and advice seekers. He would concentrate intensely, maybe for a few moments, maybe for more, then arrive at a decision, dispatch instructions, and move on. That focus was his genius, but it was the genius of a monarch not a democrat. It kept him isolated, made him severe, and sometimes left him exhausted. Morgan said he could do a year’s work in nine months, but not twelve. His impatience could be withering. When a church organist gathered the nerve to ask a favor, Morgan gave him a minute. “I’m struggling to . . .” the man stammered. “So am I,” Morgan supposedly replied. “Keep struggling. Good day.” Then he walked back to his desk.

Morgan became more than a banker in the 1880s. His transformation wasn’t gradual, it was absolute, and it happened in a day. Morgan worried that European railroad investors were wearying of American imprudence, of accounting fictions and expensive rivalries that wasted their money. He made up his mind to remedy some “sore spots” in the industry. One of them ran right past his summer home. The West Shore line had been built to compete with the New York Central, operating parallel to it from New York City to Buffalo on tracks close enough to be visible. There wasn’t enough freight traffic for two lines, though, so each reduced rates until the West Shore was insolvent and the Central was heading that way.

Morgan devised a plan whose legality might have made others hesitate, but he was willing to take the risk. He invited the railroad executives onto Corsair and didn’t let them off until they came to an agreement to end their hostilities. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t get any more money from him. They ate a lovely lunch and smoked cigars as they sailed to Sandy Hook, New Jersey, then up the Hudson to West Point, where they could view the military academy high on the bluffs, and back again. “You must come into this thing now,” Morgan said to the lone holdout, and then said little else. By day’s end they had a deal. The Central would buy the West Shore out of bankruptcy. In exchange, the West Shore owners could buy from the Central’s owners a line in Pennsylvania to combine with the one they already operated there. Because such a monopoly was unlawful in Pennsylvania, Morgan would step in as a proxy buyer.

That didn’t fool everyone. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court eventually ruled against the merger, but by then the rivalries between the railroads and the men had dissipated. Each had been able to raise their rates, and their stock prices and dividends soon followed. Only their customers paid. Morgan continued to apply his remedies, and to be strained by his work.

As he reached age fifty, even his father warned him to slow down and stop responding so intensely to every entreaty, however desperate. (“Let the ‘small fry’ go to some other Doctor,” Junius said.) But the business community had come to believe that Morgan was indispensable. He was seen as the one man who could convince antagonists to cooperate. Even though they didn’t always heed him, he would continue trying throughout the next decade. Morgan sought money and its rewards—the homes, the yacht, the art—but as America’s economy expanded, he sought something bigger and more fundamental, too. He wanted to rationalize the free-for-all of capitalism—to make it orderly and concentrated, directed from above by the powerful men who, he was certain, knew best.

__________________________________

From The Hour of Fate by Susan Berfield. Used with the permission of Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2020 by Susan Berfield.

#TheHourOfFate #NewsAndCulture #Politics #Railroads #Features

Arplis - News

source https://arplis.com/blogs/news/how-a-dangerous-exploitative-railroad-industry-created-j-p

0 notes

Text

William Barr got his law degree at night school while working as a CIA agent during the Nixon CIA abuse period. He's never been a trial lawyer or a prosecutor. He's a rogue @CIA agent who hates American values of justice. The @FBIWFO @NSAGov @ODNIgov should consider him an enemy.

Laurence Tribe: Barr and Trump could permanently alter the balance of power among the branches of government.

"If those views take hold, we will have lost what was won in the Revolution—we will have a Chief Executive who is more powerful than the king."

William Barr, Trump’s Sword and Shield

The Attorney General’s mission to maximize executive power and protect the Presidency.

By David Rohde | Published January 13, 2020 | New Yorker Magazine | Posted January 14, 2020 |

PART ONE

Last October, Attorney General William Barr appeared at Notre Dame Law School to make a case for ideological warfare. Before an assembly of students and faculty, Barr claimed that the “organized destruction” of religion was under way in the United States. “Secularists, and their allies among the ‘progressives,’ have marshalled all the force of mass communications, popular culture, the entertainment industry, and academia in an unremitting assault on religion and traditional values,” he said. Barr, a conservative Catholic, blamed the spread of “secularism and moral relativism” for a rise in “virtually every measure of social pathology”—from the “wreckage of the family” to “record levels of depression and mental illness, dispirited young people, soaring suicide rates, increasing numbers of angry and alienated young males, an increase in senseless violence, and a deadly drug epidemic.”

The speech was less a staid legal lecture than a catalogue of grievances accumulated since the Reagan era, when Barr first enlisted in the culture wars. It included a series of contentious claims. He argued, for example, that the Founders of the United States saw religion as essential to democracy. “In the Framers’ view, free government was only suitable and sustainable for a religious people—a people who recognized that there was a transcendent moral order,” he said. Barr ended his address by urging his listeners to resist the “constant seductions of our contemporary society” and launch a “moral renaissance.”

Donald Trump does not share Barr’s long-standing concern about the role of religion in civic life. (Though he often says that the Bible is his favorite book, when he was asked which Testament he preferred, he answered, “The whole Bible is incredible.”) What the two men have in common is a sense of being surrounded by a hostile insurgency. A few days after Barr’s speech, Trump told an audience at the conservative Values Voter Summit, “Extreme left-wing radicals, both inside and outside government, are determined to shred our Constitution and eradicate the beliefs we all cherish. They are trying to hound you from the workplace, expel you from the public square, and weaken the American family, and indoctrinate our children.” As the effort to remove the President has gathered strength, Barr’s and Trump’s political interests have converged. Both men combine the pro-business instincts of traditional Republicans with a focus on culture clash and grievance. Both believe that any constraint on Presidential power weakens the United States.

Eleven months after being sworn in, Barr is the most feared, criticized, and effective member of Trump’s Cabinet. Like no Attorney General since the Watergate era, he has acted as the President’s political sword and shield. When the special counsel Robert Mueller released the findings of his inquiry into connections between Trump’s 2016 campaign and Russia, Barr presented a sanitized four-page summary before the report was made public, which the President used to declare himself cleared. At the behest of the President, Barr launched an investigation of the F.B.I.’s Trump-Russia probe and the intelligence community’s assessment that Russia intervened on Trump’s behalf in the election. Rather than seek a nonpartisan commission, Barr appointed a federal prosecutor, reinforcing the President’s claims of a “coup.” When an exhaustive review by the Justice Department’s inspector general found no evidence of political bias in the F.B.I. investigation, Barr issued a statement misrepresenting its findings and arguing that the evidence in the Russia probe was “consistently exculpatory”—leaving out the fact that five people connected to Trump’s campaign have been indicted for lying to investigators.

Barr maintains that Article II of the Constitution gives a President control of all executive-branch agencies, without restriction; in practice, this means that Trump would be within his rights to oversee an investigation into his own misconduct. (Barr declined multiple interview requests.) Throughout the House’s impeachment inquiry, Trump dismissed subpoenas for documents and testimony from Administration officials—a step taken by no other President. Barr and Pat Cipollone, a White House lawyer who once worked as Barr’s speechwriter, have also rejected subpoenas, flouting a congressional power plainly delineated in the Constitution. Donald Ayer, who served as Deputy Attorney General under George H. W. Bush, said, “They take the position that they don’t even have to show up. That’s totally outrageous. It’s denying the legitimacy of another branch of government in the name of executive supremacy.” Ayer described Barr’s ideas about Presidential power as “chilling” and “deeply disturbing.” If Trump survives a trial in the Senate, a President’s ability to resist congressional oversight will vastly expand. Laurence Tribe, a professor of constitutional law at Harvard, warned that Barr’s and Trump’s efforts could permanently alter the balance of power among the branches of American government. “If those views take hold, we will have lost what was won in the Revolution—we will have a Chief Executive who is more powerful than the king,” Tribe said. “That will be a disaster for the survival of the Republic.”

At the age of sixty-nine, Barr is grayer, heavier, wealthier, and more combative than he was when he served as George H. W. Bush’s Attorney General, twenty-eight years ago. But his ideology has not changed much, according to friends and former colleagues. “I don’t know why anyone is surprised by his views,” Jack Goldsmith, a law professor who headed the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel during the George W. Bush Administration, told me. “He has always had a broad view of executive power.”

A longtime member of the capital’s legal establishment, Barr is described by both allies and adversaries as a formidable thinker who relishes debating issues of Roman history, Christian theology, and modern morality. During his first tenure as Attorney General, he earned the nickname Rage and Cave: when he felt that his principles had been violated, he tended to bluster, then gradually accept the situation. Colleagues describe him as both supportive and self-regarding, happy to delegate but impatient with incompetence. A self-styled polymath, Barr has strong opinions on issues ranging from legal arcana to the proper mustard to apply to a sandwich. He designed his own home, a sprawling house in McLean, Virginia, and is not above boasting about it. During a trip to Scotland with a friend, he quizzed the owner of a local inn about whether the paint on the wall was “Card Room Green or Green Smoke, by Farrow & Ball.” The innkeeper had no idea what he was talking about.

Like other prominent conservatives, Barr formed his politics in reaction to a liberal consensus around him. He grew up on Riverside Drive, in Manhattan, among the bookish élite of the Upper West Side. As his neighbors hoped that Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society would flourish, the Barr family supported Barry Goldwater for President.

Barr’s mother, Mary, taught at Columbia, and worked as an editor at Redbook. His father, Donald, was the headmaster at Dalton, a progressive private school on the Upper East Side. During the Second World War, Donald had served in the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the C.I.A. As headmaster, he believed that discipline instilled morality, helping to fend off the “social pathology” that his son warned about decades later. While birth control and feminism were reshaping conventions around sex and work, Donald insisted on the old ways. Chip Fisher, who attended Dalton at the time, remembered him as brilliant but out of place: “It was like having Jonathan Edwards at the pulpit.” Dalton parents saw Barr as autocratic, insular, and obsessed with adherence to rules. In the early seventies, after a protracted and ugly public fight with the school’s board, he was forced out of his job.

Mary Barr, an observant Catholic, sent William and his three brothers to Corpus Christi elementary school. Even there, Barr was an outlier. In the first grade, he delivered a speech in favor of Dwight Eisenhower’s Presidential campaign. Later, he declared his support for Richard Nixon, and a nun promised to pray for him. In high school, at Horace Mann, Barr—known then as Billy—presented fellow-students with a line-by-line exegesis of the Constitution. One classmate told me that Barr delighted in intellectual combat: “That smug, low-key demeanor—he really loved to push people’s buttons.” Garrick Beck, another classmate, disliked Barr’s politics but admired his integrity. Even then, he said, Barr was convinced that only a strong President could protect America from threats. “How else does a nice guy like Barr defend this boorish tycoon?” Beck said, of Trump. “I think he is doing it because he is a true believer.”

When Barr was an undergraduate, at Columbia, his classmates marched against the war in Vietnam. Barr wanted instead to buttress American power. He had told a guidance counsellor that he hoped one day to lead the C.I.A., and, during breaks from school, he spent two summers as an intern there. In 1973, he finished a master’s degree in Government and Chinese Studies and returned to the C.I.A. as an intelligence analyst. At the time, a Senate investigation—known as the Church Committee—was uncovering decades of abuses at the C.I.A., and laws were being passed to curtail them. Barr later recalled the effort as a kind of assault, delivering “body blows” to the agency.

Barr spent two years as an analyst, but he was also considering a career in law. He started taking night classes at George Washington University Law School, and, in 1975, he transferred to the agency’s Office of Legislative Counsel. The following year, George H. W. Bush became the C.I.A. director, and Barr helped prepare him for testimony on Capitol Hill. One hearing involved a bill that would require the C.I.A. to send a written notification to Americans whose mail the agency had secretly opened. Among the bill’s sponsors was Bella Abzug, a liberal Democrat who represented Barr’s old neighborhood in New York. As a defense attorney, Abzug had won a stay of execution for Willie McGee, a black man convicted of raping a white woman in Mississippi; she had also represented several Americans accused by Senator Joseph McCarthy of being Communists. The C.I.A. spied on her for twenty years, at times opening her mail.

As Abzug and her colleagues grilled Bush about the C.I.A.’s activities, Barr saw a chance to impress the new director. “I went up and sat in the seat that’s behind the witness,” he recalled in a 2001 oral history of the Bush Administration. “Someone asked him a question, and he leaned back and said, ‘How the hell do I answer this one?’ I whispered the answer in his ear, and he gave it, and I thought, ‘Who is this guy? He listens to legal advice when it’s given.’ ”

When Barr began his career in government, the idea that the Presidency was too weak might have been considered eccentric, even radical. Mostly, people were concerned that it had grown too strong. As the Watergate scandal unfolded, the former Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., published an influential book called “The Imperial Presidency,” in which he enumerated the habits of potential autocrats: “The all-purpose invocation of ‘national security,’ the insistence on executive secrecy, the withholding of information from Congress, the refusal to spend funds appropriated by Congress, the attempted intimidation of the press, the use of the White House as a base for espionage and sabotage directed against the political opposition.”

Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, and embodied an image that was anything but imperial. He carried his own luggage, enrolled his daughter in public school, and shunned “Hail to the Chief” as an excessive display of pomp. More important, he enacted reforms that curtailed executive-branch power. He signed strict ethics legislation that empowered independent counsels and inspectors general to investigate waste, fraud, and abuse. Critics, including the conservative legal scholar Antonin Scalia, complained that the changes crippled the Presidency, but the new regulations had broad support from Congress and from the public.

With Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, things began to change. The Republican Party, after three decades as a minority in Congress, took control of the Senate—part of a conservative resurgence that Reagan hailed as “morning in America.” In 1982, the White House hired Barr as a deputy assistant director for legal policy. He fell in with a like-minded group of young lawyers, who began devising a legal armature for the executive branch as it tried to restore its power.

In 1986, Reagan appointed Scalia to the Supreme Court. That same year, aides sent Attorney General Edwin Meese a report, recommending steps to widen the power of the Presidency. Reagan, they said, should veto more legislation, and decline to enforce laws that “unconstitutionally encroach upon the executive branch.” The report outlined a legal argument that the President had unrestricted control of all executive-branch functions, and also questioned the constitutionality of special counsels and inspectors general. In a speech, Meese argued that even Supreme Court rulings should not be viewed as “the supreme law of the land.” (Two years later, Meese resigned, amid accusations of helping to steer federal contracts to a friend.)

In 1987, an independent counsel was appointed to investigate whether a Justice Department official named Ted Olson had lied to Congress during testimony regarding the Environmental Protection Agency. Meese and other conservatives challenged the move as unconstitutional. In their view, independent prosecutors were nothing more than unaccountable, costly political weapons, which Democrats used to smear Republican Administrations. (In fact, according to Stephen Gillers, a professor of legal ethics at New York University’s law school, both parties have sought to use such counsels for political advantage. But, he added, they remain necessary to limit abuses: “What the special counsel does is provide a check.”)

The resulting case, Morrison v. Olson, went to the Supreme Court, which ruled that independent counsels did not interfere “unduly” or “impermissibly” with the powers of the executive branch. The sole dissent came from Scalia, who cautioned that a politically biased prosecutor could carry out “debilitating criminal investigations” for minor crimes. “Nothing is so politically effective,” he wrote, “as the ability to charge that one’s opponent and his associates are not merely wrongheaded, naive, ineffective, but, in all probability, ‘crooks.’ ” (Ultimately, prosecutors declined to charge Olson.)

For Reagan and his aides, the Supreme Court ruling was not an abstract concern. The year before, news had broken of what became known as the Iran-Contra scandal. In an extraordinary series of crimes, the C.I.A. director William Casey and several White House aides sold sophisticated weaponry to Iran and funnelled the profits to anti-Communist rebels in Central America, in defiance of a law that specifically barred support for the group. All the while, Casey and the aides brazenly lied to Congress about their actions. When the scheme was uncovered, Reagan’s poll numbers sank, but he denied knowledge of the operation and avoided impeachment.

In televised hearings, the National Security Council aide Oliver North argued that Presidents and their aides should be able to do whatever they deem necessary to protect the country from threats. Dick Cheney, then a congressman from Wyoming, argued that North and his allies had done nothing improper, because foreign policy and national security should be controlled solely by the executive branch. But Democrats and a majority of Republicans said that Congress must be able to act as a check on a wayward President. At the hearings, Daniel Inouye, a Democratic senator from Hawaii, who headed the inquiry, warned that a “cabal” of officials who believed they had a “monopoly on truth” could lead to “autocracy.” Barr was unmoved. He later told an interviewer, “I think people in the Iran-Contra matter have been treated very unfairly.”

When George H. W. Bush ran for President in 1988, Barr, who was then thirty-eight, seized an opportunity to continue the mission of the Reagan years. He joined the campaign as an adviser, and, after Bush won, he was appointed to run the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, which advises the President and all federal agencies.

Barr immediately produced a memo, arguing that Congress was a menace to the Presidency. He urged Administration officials to be alert to legislative encroachment, and cited ten recent examples, from “Micromanagement of the Executive Branch” to “Attempts to Restrict the President’s Foreign Affairs Powers.” He wrote, “Only by consistently and forcefully resisting such congressional incursions can executive branch prerogatives be preserved.” Barr began chairing meetings in which the general counsels of executive-branch departments drafted a strategy to work against Congress. He recalled in 2001 that the President supported the mission: “Bush felt that the powers of the Presidency had been severely eroded since Watergate and [by] the tactics of the Hill Democrats.” But Bush favored an incremental approach, saying, “I don’t want you stretching—I think the way to advance executive power is to wait and see, move gradually.”

In a series of decisions involving government actions overseas, Barr helped expand Presidential power. In 1989, Bush was in a standoff with Manuel Noriega, the strongman leader of Panama, and considered having him arrested, on charges that included drug trafficking and money laundering. The Justice Department had traditionally considered that the President lacked the power to order arrests on foreign soil. But, in June, Barr issued a legal opinion arguing that Bush had “inherent constitutional authority” to order the F.B.I. to take foreign antagonists into custody.

The following year, after the Iraqi President Saddam Hussein moved his forces into Kuwait, Bush asked at a White House meeting if he needed congressional approval to mount a counterinvasion. Barr, who by then had been promoted to Deputy Attorney General, said that the mandate to defend national security gave the President the power to go to war whenever he wanted—even to launch a preëmptive attack on Iraqi forces, if he believed that they were preparing to deploy chemical weapons against American troops.

But Barr feared that lawmakers would try to block such an action, and so he urged Bush to cover himself by obtaining Congress’s support. Even the other conservatives in the room were startled; Justice Department officials were expected to maintain scrupulous impartiality. According to Barr, Cheney, at that time the Secretary of Defense, reprimanded him: “You’re giving him political advice, not legal advice.” Barr recalled that he said, “I’m giving him both political and legal advice. They’re really sort of together when you get to this level.” In August, 1990, Bush invaded Kuwait, with congressional approval. The following year, he named Barr Attorney General.

Since Barr’s days at Horace Mann, he has felt that the transformations of American society that began in the sixties have worsened its social problems. For decades, he registered unflinching disdain for criminal-justice reform, support for religion, and sympathy for big business. In a 1995 symposium on violent crime, he argued that the root cause was not poverty but immorality. “Violent crime is caused not by physical factors, such as not enough food stamps in the stamp program, but ultimately by moral factors,” he said. “Spending more money on these material social programs is not going to have an impact on crime, and, if anything, it will exacerbate the problem.” Barr also dismissed the idea of wrongful convictions. “The notion that there are sympathetic people out there who become hapless victims of the criminal-justice system and are locked away in federal prison beyond the time they deserve is simply a myth,” he wrote. “The people who have been given mandatory minimums generally deserve them—richly.”

As Attorney General, Barr increased sentences for drug-related crimes and cracked down on illegal immigration. In 1992, rioting erupted in Los Angeles following the acquittal of four police officers who had been videotaped beating the motorist Rodney King. Barr deployed two thousand federal agents on military planes to stop the unrest. He later argued that civil-rights charges should have been brought—not just against the offending officers but also against the rioters on the streets of L.A. “We could have cleaned that place up,” he lamented in 2001. “Unfortunately, we just brought the federal case against the cops and never pursued the gangsters.”

During his tenure, Barr turned down multiple requests to name prosecutors to examine potential executive-branch abuses. “The public integrity section told me that I had received more requests for independent counsel in eighteen months than all my predecessors combined,” Barr recalled. “It was a joke.” In one case, Barr opposed the appointment of a special counsel to investigate the Administration’s dealings with Iraq before the invasion of Kuwait. Even some conservatives objected; William Safire, the Times columnist, called him “cover-up general Barr.”

After Bush lost the 1992 Presidential election, to Bill Clinton, he blamed the defeat on Lawrence Walsh, the lead prosecutor in the Iran-Contra affair. Four days before the election, Walsh had filed a new criminal charge against former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, and revealed an entry from Weinberger’s diary that cast doubt on Bush’s long-running claim that he opposed trading arms for hostages. Bush was furious, Barr later recalled: “He felt that that indictment had cost him the election.” On Christmas Eve, 1992, Bush pardoned four former officials whom Walsh had prosecuted, and two more who were awaiting trial—a decision that Barr supported. In a statement accompanying the pardons, Bush complained of “the criminalization of policy differences,” and wrote that criticisms of the President should be expressed in “the voting booth, not the courtroom.”

To Democrats, the pardons were outrageous; officials had defied Congress to carry out a dangerous and illegal scheme, which provided arms to an avowed enemy of the U.S. Barr dismissed those concerns and suggested that Walsh’s investigation had unfairly hobbled the Bush Presidency. “It was very difficult because of the constant pendency of the Iran-Contra case and Lawrence Walsh, who I thought was a—I don’t know what to say in polite company,” he recalled in 2001. “He was certainly a headhunter and had completely lost perspective.”

Three blocks from the White House, on K Street, is a storefront with signs in its windows advertising “solidarity” and “mercy and justice.” The building houses the Catholic Information Center, a bookstore and a chapel where federal workers and tourists can attend morning and evening services. On a recent weekday afternoon, a sign announced an upcoming debate between conservative writers, called “Nationalism: Vice or Virtue?” A skateboard with an image of the Virgin Mary hung not far away, in the hope of attracting a younger crowd.

Led by a member of the archconservative group Opus Dei, the center is a hub for Washington’s influential conservatives. Its rise began in 1998, with the arrival of a charismatic new director, the Reverend C. John McCloskey, a forty-four-year-old banker turned priest. Hard-charging and unabashedly political, McCloskey liked to say, “A liberal Catholic is oxymoronic.” During the nineties, he helped convert a series of prominent conservatives to Catholicism, including the former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who is a vocal Trump backer. In 2003, McCloskey quietly left his post, and Opus Dei later paid a settlement of nearly a million dollars to a woman who said that he had sexually harassed her. But the center’s board of directors remains a nexus of politically connected Catholics. Pat Cipollone and Barr have both served on the board, as has Leonard Leo, the executive vice-president of the Federalist Society. Asked about Barr’s role, the center’s chief operating officer, Mitch Boersma, confirmed that he had served as a board member from 2014 to 2017 but said, “We don’t have anything to add.”

After Bill Clinton took office, in 1993, Barr stepped away from government work and continued promoting his version of an ideal society through various religious organizations. He served on the boards of groups whose charitable work is widely praised, such as the Knights of Columbus and the New York Archdiocese’s Inner-City Scholarship Fund. For years, Barr has paid the tuition of eighteen students a year at a parochial school in New York.

But Barr’s instinct for ideological combat did not wane. In 1995, he wrote an article for a journal called The Catholic Lawyer. Two years earlier, the F.B.I. had mounted a disastrous raid on a compound inhabited by a cult in Waco, Texas. In his article, Barr complained that journalists had made “subtle efforts” to liken the cult to the Church. “We live in an increasingly militant, secular age,” he wrote. “As part of this philosophy, we see a growing hostility toward religion, particularly Catholicism.” He argued that religious Americans were increasingly victimized: “It is no accident that the homosexual movement, at one or two percent of the population, gets treated with such solicitude, while the Catholic population, which is over a quarter of the country, is given the back of the hand.”

His position on executive power wavered over time, depending on which party controlled the White House. When Clinton was under investigation in the Whitewater affair, a Senate committee subpoenaed documents, and Clinton’s team claimed that they were protected by lawyer-client privilege. Barr called the rationale “preposterous,” and later complained that Clinton had diminished his office: “I’ve been upset that a lot of the prerogatives of the presidency have been sacrificed for the personal interests of this particular president.” When George W. Bush entered the White House, Barr resumed his arguments that the President should have “maximum power” in national security. In op-eds and in congressional hearings, he spoke in favor of military tribunals, the Patriot Act, and sweeping surveillance. In the Obama years, as Republicans in Congress launched a campaign to thwart the President’s initiatives, Barr largely went silent again.

In the private sector, Barr built a reputation as a pugnacious opponent of federal regulation. As the general counsel of G.T.E., one of the country’s largest telephone companies, he persuaded regulators to approve mergers that benefitted his employer while arguing against those which benefitted rivals. Around the office, he talked at times about such moral doctrines as natural law, but never expected secular colleagues to share his beliefs. Barr didn’t socialize much with co-workers; he commuted each week to New York from Washington, where he and his wife, Christine, raised three daughters amid a Catholic community centered on a tight circle of churches, schools, and social clubs. The girls went to a Catholic school in Bethesda, where Christine worked as a librarian. (Barr’s daughters later attended Catholic colleges, and all became lawyers.)

After years of government work, Barr began to grow rich. He helped lead G.T.E. when it merged with Bell Atlantic to form Verizon, the country’s largest telephone company. From 2001 to 2007, he was paid an average of $1.7 million a year in salary and bonuses, in addition to stock options, the use of a company jet, and a spending allowance. When Barr took an early retirement, in 2008, he received twenty-eight million dollars in deferred income and separation payments—a large enough sum that a watchdog group cited the payouts as an example of poor corporate governance. Barr had amassed a fortune that Forbes recently estimated at forty million dollars, and he made millions more serving on corporate boards, including those of Time Warner and Dominion Energy. He also joined Kirkland & Ellis, a Washington firm known for its leading conservative lawyers. And he and Christine built their house in McLean, a few miles from C.I.A. headquarters.

In July, 2012, Barr learned that his youngest daughter, Meg, had a recurrence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Meg, who was then twenty-seven years old, faced a roughly twenty-per-cent chance of survival. He stopped working and focussed on his daughter’s care. The family had Meg treated at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston, and Barr and his wife moved to be near her. After Meg underwent chemotherapy and a stem-cell transplant, Barr rented a house in the town of Scituate, outside Boston, so that Meg could be isolated from other patients and avoid infection. They read books, walked on the beach together, and talked about what Meg would do if she survived. “Those three months were the best and worst of times,” Meg told Fox News in 2019. “The hardest part of my illness was accepting the randomness of it, the fact that you can’t control the outcome. Both my father and I tend to be control freaks.”

Meg survived. But, Barr told Fox, “Meg’s illness changed our family. It changed me.” Friends of Barr’s said that he approached both his professional life and his personal life with a renewed zeal. Chuck Cooper, a litigator who worked with Barr in the Reagan Administration, told me, “I think he has an intense appreciation for life and our tenuous hold on it. And that to squander any of it is unforgivable.”

Barr was late to join the Trump revolution. In the nineties and the early two-thousands, he donated more than half a million dollars to Republican candidates, mostly such mainstream figures as George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney. (Barr even supported Jeff Flake, the Arizona senator whose occasional criticisms of Trump ended up turning constituents against him.) In 2016, Barr gave twenty-seven hundred dollars to Trump’s campaign—and about twenty times that amount to support Jeb Bush.