#and a novel for young readers. Her fiction has appeared in The New Yorker and elsewhere

Text

I’ve been an Allegra Goodman fan for years, but Sam is hands down my new favorite. I loved this powerful and endearing portrait of a girl who must summon deep within herself the grit and wisdom to grow up.”—

Lily King, New York Times bestselling author of Writers & Lovers

What happens to a girl’s sense of joy and belonging—to her belief in herself—as she becomes a woman? This unforgettable portrait of coming-of-age offers subtle yet powerful reflections on class, parenthood, addiction, lust, and the irrepressible power of dreams.

“There is a girl, and her name is Sam.” So begins Allegra Goodman’s moving and wise new novel.

Sam is seven years old and lives in Beverley, Massachusetts. She adores her father, though he isn’t around much. Her mother struggles to make ends meet, and never fails to remind Sam that if she studies hard and acts responsibly, adulthood will be easier—more secure and comfortable. But comfort and security are of little interest to Sam. She doesn’t fit in at school, where the other girls have the right shade of blue jeans and don’t question the rules. She doesn’t care about jeans or rules. All she wants is to climb. Hanging from the highest limbs of the tallest trees, scaling the side of a building, Sam feels free.

As a teenager, Sam begins to doubt herself. She yearns to be noticed, even as she wants to disappear. When her climbing coach takes an interest in her, his attention is more complicated than she anticipated. She resents her father’s erratic behavior, but she grieves after he’s gone. And she resists her mother’s attempts to plan for her future, even as that future draws closer.

The simplicity of this tender, emotionally honest novel is what makes it so powerful. Sam by Allegra Goodman will break your heart, but will also leave you full of hope.

In Sam, Allegra Goodman presents a poignant coming-of-age story that explores themes of class, parenthood, addiction, lust, and the search for joy and belonging. Through the eyes of protagonist Sam, we witness the struggles and triumphs of growing up and finding one's place in the world. This beautifully written novel is a must-read for fans of coming-of-age stories and will leave you feeling moved and full of hope.

Editorial Reviews

Review

“Allegra Goodman knows. She knows families, their griefs and rages, their love and loss: complicated parents and complicated children. In Sam, she goes deep into the heart and soul, and voice of one girl. Sam is a deeply wise and empathetic portrait of this unforgettable girl, making her way into this tricky world and into the reader’s life.”—Amy Bloom, New York Times bestselling author of In Love

“Sam is one of the most evocative and tender examinations of youth that I’ve ever read, and Allegra Goodman fully understands the strange and dreamlike qualities of Sam’s world as she tries to navigate it, populated by adults who mean well but complicate every single moment. One of the best writers around, Goodman has made something truly beautiful, evoking a feeling that is hard to name but stirs inside us with every line.”—Kevin Wilson, New York Times bestselling author of Nothing to See Here

“What seems at first to be a simple coming-of-age story deepens under its own weight and shows itself to be a beautiful meditation on all the ways we love and fail each other. I was moved by the cumulative power of Sam, and I’m still rooting for the characters.”—Ann Napolitano, New York Times bestselling author of Dear Edward

“Bracing . . . Sam’s . . . travails gain heft through [Allegra] Goodman’s perceptiveness, specificity regarding Sam’s emotions, and arresting turns of phrase. It’s impressive how much emotional power is packed into this . . . contained story.”—Publishers Weekly

About the Author

Allegra Goodman is the author of five novels, two short story collections, and a novel for young readers. Her fiction has appeared in The New Yorker and elsewhere, and has been anthologized in The O. Henry Awards and Best American Short Stories. She lives with her family in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Product details

Publisher : The Dial Press (January 3, 2023)

Language : English 336 pages

#Allegra Goodman is the author of five novels#two short story collections#and a novel for young readers. Her fiction has appeared in The New Yorker and elsewhere#and has been anthologized in The O. Henry Awards and Best American Short Stories. She lives with her family in Cambridge#Massachusetts.#art#design#beautiful#quotes#love#painter

0 notes

Link

I don’t often toot my own horn on here, but..... The Globe and Mail just published a glowing profile on my dad’s press! I’ve been doing editing and design work for him for almost 10 years, and I couldn’t be prouder to be part of the family business.

This article is available in the print edition for today (February 29 2020). The above link is behind a paywall, but I’ve copied the article below the cut.

By Naben Ruthnum

The Shirley Jackson Award is one of the most prestigious prizes in horror, with recipients ranging from genre legends Stephen King and Neil Gaiman to literary crossover writers such as Emma Cline. In 2018, a Canadian publisher of horror fiction claimed their second Jackson. But you may never have heard of Undertow Publications, which is based in the small Ontario city of Pickering.

There are as many types of horror fiction as there are ways to be scared. The particular subgenre of horror that Undertow specializes in is “weird fiction”: a style that tends toward the high literary, enfolding the supernatural, tales of malaise in urban, rural and wild settings, and a sense of discomfort and eeriness that has more to do with atmosphere than reddened fangs.

While Undertow isn’t purely a one-man show, publisher Michael Kelly is the guiding acquiring and editorial eye on all books. “I always liked the literary sort of horror, weird fiction, and I wasn’t seeing it published.” As his inspirations, he cites the writers he was reading in 2009, around the time he started the press, "things like Arthur Machen, Oliver Onions, Walter De la Mare, Violet Paget.” Kelly was also reading Britain-based magazines such as Black Static and Supernatural Tales, pages that would introduce him to the authors he would eventually publish.

The press’s business operations began in his basement, and remain there, although the initial one-book-a-year output has grown to seven scheduled for 2020 and six planned for 2021. The prestigious small publishers of supernatural fiction that dot Britain and Ireland quickly recognized a peer in Kelly. Brian J. Showers, who runs Dublin’s Swan River Press, points to Kelly’s specific vision as a defining strength: “Michael Kelly guides Undertow with both taste and style, and with a dedication characteristic of only the very best small presses.”

Kelly, who is now focusing on Undertow full-time after his recent retirement from a 30-year career at the Toronto Star that ranged from the darkroom to syndicated sales, knew that keeping an eye on scale would be a crucial part of Undertow’s continued existence.

“I was reading stuff that really intrigued me in the small press, niche stuff, but there were only a couple of venues. I did my first anthology in 2009, and it was called Apparitions. Really – copies of the book were terrible. It was on very white, photocopy paper, done at one of those Espresso Book Machines – I knew a guy at McMaster who ran one. It was a bound book, but poorly bound.”

Despite the humble appearance of this first offering from a press that would soon be known for their beautifully designed and printed trade paperbacks, overseen by art director Vince Haig, Apparitions was nominated for a Shirley Jackson Award. The prestigious American award is well known to genre fans, and Undertow was quickly noticed by both readers and writers eager for a new venue for their weird fiction interests. But Kelly continued to grow the press slowly, guided by his own tastes and reading. Short-story collections – anthologies or single-author collections – form almost the entirety of Undertow’s output. One anthology series, Shadows and Tall Trees, has been going since the second year of the press’s existence, with the latest edition garnering awards recognition and the eighth volume appearing as Undertow’s first 2020 publication.

For years, Kelly has been finding authors in small magazines, online and in print – and while Undertow is a Canadian small-press success story, Kelly isn’t willing to let borders dictate what he’s going to publish. “I have published Canadian authors – Simon Strantzas, and Helen Marshall, and this year I’m publishing Richard Gavin. But I don’t do enough to get grant money, and I sort of want to publish what I want to publish.” Strantzas is a Canadian weird-fiction fixture, and his contribution to Shadows and Tall Trees 8 is definitively weird: “The Somnambulists” is the story of a hotel constructed from collaborative dreams. It’s a fantastical concept anchored by banality – a Ministry hotel inspector is being taken on a tour of the hotel – but even the dullness of the inspector’s official function doesn’t protect him from the creeping atmosphere of the place, and the possibility that his own family may be deeply involved in the dream that he is touring.

In selecting individual stories and collections, Kelly lets excitement guide him, as it did in the case of Kay Chronister, a young American writer whose first collection emerges from Undertow in March.

“Kay published a story I read online in a magazine called Shimmer that’s not around anymore. It was called ‘The Fifth Gable,’ and it knocked me flat. Last year, she had a story appear in Black Static, called ‘Roiling and Without Form.’ So I reached out to her, and asked her if she had any others, and she did.” Chronister’s stories, wide-ranging as they are, often seat horror in patriarchal traps of marriage and domestic expectations, while other elements in the same stories draw on horror mainstays such as witchcraft and or hereditary curses. As with other Undertow books, it’s the prose – in Chronister’s case, rich, descriptive, clean and never-purple prose – that melds horror elements that could work in a Hammer film with thematic content that would be at home in a New Yorker short story.

Kelly’s patience in growing his publishing list from year to year has also helped him wait on authors he particularly wanted. Priya Sharma, a UK-based writer who also works as a doctor, had been publishing stories for almost a decade before Undertow Press put out her first collection, All the Fabulous Beasts. “I was bugging her for years, then I gave up,” Kelly says. “Then, eventually, she emailed me. That book did very well.” Sharma’s collection won both the British Fantasy Award and Shirley Jackson Award, and the book is Undertow’s best-selling single-author collection.Unable to offer the large advances of a trade publisher, Kelly is also emphatic about leaving all ancillary rights with his authors. “We don’t take any audio rights, film rights – some of these presses grab everything they can.” In an era where industries from podcasts to film are hungry for intellectual property, keeping these rights author-exclusive matters, and Undertow’s books have attracted the interest of scouts from Netflix, among other companies.

“I’ve never put any commercial thinking into the press. I don’t look at a writer and think I want to publish them because they’ll sell a lot of books. I publish books that I want to read.” In addition to Haig, the Undertow team is rounded out by two family members – Courtney Kelly, Michael’s publishing-program graduate daughter, who works on typesetting, interior layout and design, and Carolyn Macdonell-Kelly, Michael’s wife, who takes on proofreading and bookkeeping duties, in addition to joining him in the ever-important sales efforts of the press. Kelly is currently trying to buck the enforced reliance that many small presses have on a particular online behemoth.

“I have to sort of play ball with Amazon, which drives me crazy, but otherwise the books don’t get any distribution. As a small press, I’m sending out stuff to independent bookstores all the time, trying to get them to stock the books … percentage-wise, probably about 70 per cent of my sales are Amazon. I do have quite a few loyal customers – my e-mail list is close to 1,000 – and I have loyal readers who will buy all of my stuff directly.”

Kelly is excited to expand the range of horror subgenres Undertow publishes, moving beyond the subtle, literary weird that they are known for. Kelly describes a forthcoming collection by Steve Topes as “visceral, straight-out horror. Not really what I usually publish, but he does it so well. The writing is so descriptive, I liked it.” And Undertow is contributing to a longstanding horror subgenre with a coming collection of ghost stories from A.C. Wise, a Canadian who lives in the United States. Wise was excited at the chance to have a book with a press she’d long admired. “Simply put, Undertow publishes gorgeous books. When Michael approached me about doing a collection, I jumped at the chance, knowing the care that goes into everything he produces.”

Coinciding with Kelly’s full-time commitment to Undertow is a change in how the press sources its publications: They recently opened to submissions for the first time, and received hundreds of manuscripts. But Kelly’s efforts to move toward publishing novels instead of the short fiction that the press established itself with have not been altogether successful, yet. “We got hundreds of submissions, and only three of them were novels. We’re known for our short-story collections [and our anthologies], so that’s what we got. We were surprised, because we specifically asked for novels and novellas. Three novels, two novellas … and the rest were short-story collections.”

What hasn’t changed is Undertow’s selection process, as Kelly admits. “We ended up taking one novella and three short-story collections. We didn’t like any of the novels … and by ‘we,’ I mean me.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

books 2017 finale

this is almost brief.

december:

The Lying Game - Ruth Ware

Every Heart A Doorway - Seanan McGuire

Saving Morgan - MB Panichi

Call Me By Your Name - Andre Aciman

City of Fallen Angels - Cassandra Clare

City of Lost Souls - Cassandra Clare (see below)

Barry Lyndon - William Thackeray

Into Thin Air - John Krakauer

that was the brief part, this is the ‘almost’ part. 279 for the year, up from 188 last year.

Why Did I Ever - Mary Robison

fiction, re-read, it is a delight always.

Binti - Nnedi Okorafor

fiction, I read a couple of other interesting explorations of "what does it mean when I am more like the monster than the hero?" which is pretty astoundingly generative as a genre, this was my fave. Binti herself explores two alien cultures, and reacts in practical ways to the unexpected, which is always a delight in a heroine. Space is strange; let us not dwell on realism, it's a different real. This willingness to abandon what does not work is characteristic of young women. Young women are great sff protagonists, and young women of historically-disadvantaged backgrounds who are incontestably heroic are the greatest sff protagonists of all.

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage - Sydney Padua

art, complex and excitingly rich alternative history, which not only explains computing history but also, at the last page, yanks at the heart of anyone who has ever yearned. The art is propulsive and antic, and the visual puns are very good. (not to be missed: the encounter with Queen Victoria!) Even I, a person who is bad at reading graphic novels, loitered over the drawings to understand them rather than reading the words and flipping the page.

IQ - Joe Ide

fiction, what Sherlock Holmes would actually be like in a modern novel. A loner in a big important city who feels that he has much to make up for, check the convincing depiction of depression, and the real nightmares who actually do fall short in the world's estimation, except that the world is too busy to notice them at all. The main thread is a fun romp, and the minor characters are so exquisite that it is almost a picaresque. I was talking about this loudly on a train, and when I and it stopped, a man came up to me and asked if I could give him the title again as he wanted to buy it. TRUE.

Hild - Nicola Griffith

fiction, on the recommendation of @inclineto This is what historical fiction should be like: it's not that this was somehow better than everything else, it was merely relevatory. Historical fiction can be about religion, power, families, war and how to card wool. (You don't have to pick if you are an inside or outside person! Girls, you can be both Thayet and Buri!) The protagonist can be cheerfully bisexual, too. It's as though all of the novels we have determinedly pretended were about gals being in love with other gals came true, and also the heroine gutted bad guys and was eventually canonized.

Everything is Teeth - Evie Wyld and Joe Sumner

art, teeth were a big theme this year (as ever) and this is the one where a) no one talks about the shameful inequalities in provision of dental care to children in the United States and b) no one fucks a fish. just letting the distinguished reader know that I have a selection process for what I read, I can see how that might not be clear. I would be delighted to talk about a) and b) mentioned here, or anything else I read this year.

Water Dogs - Lewis Robinson

fiction, re-read, always always. the person who loves novels about well-off and unusual families falling apart in opulent squalor either literal or metaphoric and maybe murder? that person is tuv. Inexplicably, no part of this was ever published in The New Yorker.

Margaret the First - Danielle Dutton

fiction, on the recommendation of @elanormcinerney The subgenre of “garrulous historical person in his or her own words" is becoming something of a crowded field (Ruth Scurr's book on/with John Aubrey is the other best entrant, there are others) and the artistry involved in this example is particularly fulfilling. This is smart and I remembered all the stuff about science and poetry that Arts & Letters Daily is always trying to teach me. That's why to read women, among other reasons. The smarts.

Blood in the Water - Heather Ann Thompson

non-fiction, persistent mismanagement, gross racism, and inadequate communication turn out not to be the way to run an organization. This is really a masterpiece of microhistory, about the Attica Prison Uprising, and the ways in which people in power blind themselves to consequences of their actions, while the people who suffer the consequences of those actions suffer and continue to suffer.

See Under: Love - David Grossman trans Betsy Rosenberg

fiction, goes well with the Quay Brothers' "Street of Crocodiles," while we are talking about Bruno Schulz. I read parts of it in my head to the neighbors' dog. the dog understood. my voice would have shredded with sadness if I had spoken. thanks, Astro, for being there.

Sarong Party Girls - Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

fiction, this is the novel that Kevin Kwan isn't tough enough to have written. It's about how grown-ups deal with the consequences of their actions, and also about drinking with pals. A person can be both of those things, and Jazzy is that, and more.

Emotionally Weird - Kate Atkinson

fiction, a strong taste for the picaresque, and a crystalline capture of youthful aimlessness and disorder even as it is being shaped by larger forces. Effie wanders through words and life, and I had a wonderful time with this one summer afternoon. No one else appears to have much liked this book, other people are wrong, it's funny. It is profoundly show-offy and unrelateable to play parlor games in the car, say book reviewers with terrible personalities -- sounds like someone lost a game of fives recently. (I’m very good at the game of fives, and I did not quite feel personally criticized when this book was unpopular, if only because I have my expertise at ‘name five mountaineers who did not climb Mount Everest’ to console me.)

A Line Made By Walking - Sara Baume

fiction, I just really love books about depressed women acting as they see fit.

Chemistry - Weike Wang

fiction, I just really love books about depressed women acting as they see fit.

The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue - Mackenzi Lee

fiction, recommended by @mysharkwillgoon see "Hild" above, books are just better when the main character solves problems and kisses everyone. This is how historical romances should be, this is what we have all received for those years of crossing our fingers under the cover of a Heyer and hoping 'maybe he'll love his best friend! maybe she'll tell her cousin what she really thinks!" and they DO. and then they escape from pirates, “The Monk,” and robbers.

Raven Rock - Garrett Graff

non-fiction, read this first and then think about how we all got from there to a study of underground bunkers and the places where some of us were going to go when the rest of us died. Offutt AFB is along the way, which only served to remind me that I have family in Nebraska and I live in fear of the day when one of them does some casual genealogy and we have to talk; "so. your state. big in the planning for our forthcoming and yet reucrring nuclear crisis, howdoes that feel? feels powerful and also sickening, yeah? anyway, your great-aunt's ashes aren't scattered in the Lincoln Tunnel, but we thought about it."

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye - Sonny Liew

art, here is what we are up against. The theme this year appears to have been "weeping at what could have been." This is a first rate textbook, and a cunning subversion of the whole notion of textbooks. I learned a great deal from this; had I learned nothing, my eye would still have wandered along, marvelling at the layout. There are several overlapping stories about narrative, success, and Singaporean history, yet the metatextuality (horrible word, apologies) is never confrontational. Which is truly a pleasure.

The Story of a Brief Marriage - Anuk Arudpragasam

fiction, this is the book I've been telling everyone about as my fave book on the year. Only the most literary of adjectives will suffice: brutal, lyrical, lambent, noctilucent, I'm just typing words.

The Unwomanly Face of War - Sveltana Alexievich trans Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

non-fiction, more incisive than more recent collections, and in a shimmering translation. Pevear and Volokhonsky have tossed words out like diamonds on black velvet. The rare wartime history that is more appealing without a map.

City of Lost Souls - Cassandra Clare

oh give me a fucking break, Jonathan nee Sebastian brainwashed Jace nee whatever while they were in the magical flying Gormenghast pied a terre, they absolutely schtupped.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shannon Gitte Diaz

Bibliography Entry:

Publication date: 1999

Publisher: ST MARTINS PRESS

Author: Michael Cunningham

Genre: Literary Fiction

Retrieved from http://www.powells.com/book/the-hours-9780312243029/18-0

Introduction:

Michael Cunningham was raised in Los Angeles and lives in New York City. He is the author of the novels A Home at the End of the World (Picador) and Flesh and Blood. His work has appeared in The New Yorker and Best American Short Stories, and he is the recipient of a Whiting Writer's Award. The Hours was a New York Times Bestseller, and was chosen as a Best Book of 1998 by The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Publishers Weekly. It won the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the 1999 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, and was later made into an Oscar-winning 2002 movie of the same name starring Nicole Kidman, Meryl Streep and Julianne Moore.

Summary:

After opening on a melancholy note with Virginia Woolf's willful death by drowning, The Hours branches out into three interconnected plotlines.

In one plotline, Clarissa Vaughan—a middle-aged book editor living in 1990s New York—gets ready to throw a party. A beloved friend of hers is about to be awarded a distinguished literary prize, and Clarissa is arranging a private celebration where he'll be congratulated by supporters and close personal friends. Clarissa's friend Richard Brown is dying from HIV/AIDS-related illnesses, and when Clarissa checks in on him in the late morning, she can tell that he's having one of his bad days. When she comes back later to help him get dressed for the party, things take a tragic turn: Richard slides himself out of a fifth-story window and is killed. Rather than throwing a party for Richard, Clarissa now finds herself making arrangements for his funeral. In the last hours of the evening, she collects Richard's elderly mother, Laura Brown, and offers her a late-night meal.

In another plotline, that same Laura Brown is still a young woman living in a sunny, pristine suburb of Los Angeles. She wakes on the morning of her husband's birthday and eventually musters up the energy to get out of bed and face the day. Throughout the morning, Laura and her three-year-old son, Richie, make a birthday cake together. It doesn't turn out as Laura hoped, and after receiving an unexpected visit from a neighbor, Laura dumps the cake in the garbage and starts again. In the afternoon, Laura leaves Richie with a neighbor for a few hours so that she can "run some errands," by which we mean she steals away for a few hours so that she can enjoy some rare time alone. Laura checks herself into a hotel, then curls up to read Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway. Back at home that evening; Laura presides over her husband's birthday dinner. Later, once Richie is asleep, she and her husband get ready to head to bed. As Laura fiddles around in the bathroom, she thinks about how easy it would be to swallow a fatal number of sleeping pills and slip away from her life.

In the novel's third plotline, Virginia Woolf wakes up with an idea for the first line of a novel. After getting some coffee and checking in with her husband, she spends the morning drafting the first pages of the book that will eventually become Mrs. Dalloway. In the afternoon, Virginia takes a walk and ponders her heroine's fate. Back at home, she lends a hand in the printing room, where her husband, Leonard, is preparing another book for publication. Virginia is expecting a visit from her sister, niece, and nephews, and soon the clan arrives. The children have found an injured bird in the yard, and before they all come inside, Virginia helps them to make a little deathbed for the creature. In the early evening, after her extended family members are gone, Virginia slips outside for another walk. She heads toward the train station with a half-baked plan to run off to London for a few hours. She buys a ticket, and then decides to walk around the block while she waits for the next train to arrive. As she does, she sees Leonard coming toward her. Playing it cool, she keeps her plans to herself and walks home. Back at home, as bedtime approaches, Virginia makes a final decision about her novel. Instead of killing off her heroine, Mrs. Dalloway, she decides that "a deranged poet, a visionary" will die instead.

Critical Analysis:

It was indeed that this novel was a great novel of all time as it was a recipient of a lot of award. After reading the summary of the said novel, the curiosity of mine upon how this novel was considered as the novel of all time and how this novel was a recipient of a lot of award in America has been answered as the technicality of the author, how great the interconnection was presented in every plotline. One story with three interconnected plotlines is quite a tricky thing to use considering the great outcome and sacrificing your name in one novel is an enormous thing to be noted. The story gives a lot of moral lessons as it tackles a lot of social issue such as the LGBT and also the HIV/AIDS victim. The story had this moral lesson to those writers who didn’t have this chance to be a productive in their field of expertise because of lack of confidence. The novel is very technical in a way that the author used a plot twist and a surprise thingy to his reader. This story will tell how great Michael Cunningman is and how talented he is in the field of literary writing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yuval Noah Harari’s History of Everyone, Ever

Yuval Noah Harari’s History of Everyone, Ever

https://ift.tt/2Sclqw8

As a camera crew set up, Harari affably told Pinker, “The default script is that you will be the optimist and I will be the pessimist. But we can try and avoid this.” They chatted about TV, and discovered a shared enthusiasm for “Shtisel,” an Israeli drama about an ultra-Orthodox family, and “Veep.”

“What else do you watch?” Harari asked.

“ ‘The Crown,’ ” Pinker said.

“Oh, ‘The Crown’ is great!”

Harari had earlier told me that he prefers TV to novels; in a career now often focussed on ideas about narrative and interiority, his reflections on art seem to stop at the observation that “fictions” have remarkable power. Over supper in Israel, he had noted that, in the Middle Ages, “only what kings and queens did was important, and even then not everything they did,” whereas novels are likely “to tell you in detail about what some peasant did.” Onstage, at YES, he had said, “If we think about art as kind of playing on the human emotional keyboard, then I think A.I. will very soon revolutionize art completely.”

The taped conversation began. Harari began to describe future tech intrusions, and Pinker, pushing back, referred to the ubiquitous “telescreens” that monitor citizens in Orwell’s “1984.” Today, Pinker said, it would be a “trivial” task to install such devices: “There could be, in every room, a government-operated camera. They could have done that decades ago. But they haven’t, certainly not in the West. And so the question is: why didn’t they? Partly because the government didn’t have that much of an interest in doing it. Partly because there would be enough resistance that, in a democracy, they couldn’t succeed.”

Harari said that, in the past, data generated by such devices could not have been processed; the K.G.B. could not have hired enough agents. A.I. removes this barrier. “This is not science fiction,” he said. “This is happening in various parts of the world. It’s happening now in China. It’s happening now in my home country, in Israel.”

Cartoon by Paul Noth

“What you’ve identified is some of the problems of totalitarian societies or occupying powers,” Pinker said. “The key is how to prevent your society from being China.” In response, Harari suggested that it might have been only an inability to process such data that had protected societies from authoritarianism. He went on, “Suddenly, totalitarian regimes could have a technological advantage over the democracies.”

Pinker said, “The trade-off between efficiency and ethics is just in the very nature of reality. It has always faced us—even with much simpler algorithms, of the kind you could do with paper and pencil.” He noted that, for seventy years, psychologists have known that, in a medical setting, statistical decision-making outperforms human intuition. Simple statistical models could have been widely used to offer diagnoses of disease, forecast job performance, and predict recidivism. But humans had shown a willingness to ignore such models.

“My view, as a historian, is that seventy years isn’t a long time,” Harari said.

When I later spoke to Pinker, he said that he admired Harari’s avoidance of conventional wisdom, but added, “When it comes down to it, he is a liberal secular humanist.” Harari rejects the label, Pinker said, but there’s no doubt that Harari is an atheist, and that he “believes in freedom of expression and the application of reason, and in human well-being as the ultimate criterion.” Pinker said that, in the end, Harari seems to want “to be able to reject all categories.”

The next day, Harari and Yahav made a trip to Chernobyl and the abandoned city of Pripyat. They invited a few other people, and hired a guide. Yahav embraced a role of half-ironic worrier about health risks; the guide tried to reassure him by giving him his dosimeter, which measures radiation levels. When the device beeped, Yahav complained of a headache. In the ruined Lenin Square in Pripyat, he told Harari, “You’re not going to die on me. We’ve discussed this—I’m going to die first. I was smoking for years.”

Harari, whose work sometimes sounds regretful about most of what has happened since the Paleolithic era—in “Sapiens,” he writes that “the forager economy provided most people with more interesting lives than agriculture or industry do”—began the day by anticipating, happily, a glimpse of the world as it would be if “humans destroyed themselves.” Walking across Pripyat’s soccer field, where mature trees now grow, he remarked on how quickly things had gone “back to normal.”

The guide asked if anyone had heard of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare—the video game, which includes a sequence set in Pripyat.

“No,” Harari said.

“Just the most popular game in the world,” the guide said.

At dusk, Harari and Yahav headed back to Kyiv, in a black Mercedes. When Yahav sneezed, Harari said, “It’s the radiation starting.” As we drove through flat, forested countryside, Harari talked about his upbringing: his hatred of chess; his nationalist and religious periods. He said, “One thing I think about how humans work—the only thing that can replace one story is another story.”

We discussed the tall tales that occasionally appear in his writing. In “Homo Deus,” Harari writes that, in 2014, a Hong Kong venture-capital firm “broke new ground by appointing an algorithm named VITAL to its board.” A footnote provides a link to an online article, which makes clear that, in fact, there had been no such board appointment, and that the press release announcing it was a lure for “gullible” outlets. When I asked Harari if he’d accidentally led readers into believing a fiction, he appeared untroubled, arguing that the book’s larger point about A.I. encroachment still held.

In “Sapiens,” Harari writes in detail about a meeting in the desert between Apollo 11 astronauts and a Native American who dictated a message for them to take to the moon. The message, when later translated, was “They have come to steal your lands.” Harari’s text acknowledges that the story might be a “legend.”

“I don’t know if it’s a true story,” Harari told me. “It doesn’t matter—it’s a good story.” He rethought this. “It matters how you present it to the readers. I think I took care to make sure that at least intelligent readers will understand that it maybe didn’t happen.” (The story has been traced to a Johnny Carson monologue.)

Harari went on to say how much he’d liked writing an extended fictional passage, in “Homo Deus,” in which he imagines the belief system of a twelfth-century crusader. It begins, “Imagine a young English nobleman named John . . .” Harari had been encouraged in this experiment, he said, by the example of classical historians, who were comfortable fabricating dialogue, and by “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” by Douglas Adams, a book “packed with so much good philosophy.” No twentieth-century philosophical book besides “Sources of the Self,” by Charles Taylor, had influenced him more.

We were now on a cobbled street in Kyiv. Harari said, “Maybe the next book will be a novel.”

At a press conference in the city, Harari was asked a question by Hannah Hrabarska, a Ukrainian news photographer. “I can’t stop smiling,” she began. “I’ve watched all your lectures, watched everything about you.” I spoke to her later. She said that reading “Sapiens” had “completely changed” her life. Hrabarska was born the week of the Chernobyl disaster, in 1986. “When I was a child, I dreamed of being an artist,” she said. “But then politics captured me.” When the Orange Revolution began, in 2004, she was eighteen, and “so idealistic.” She studied law and went into journalism. In the winter of 2013-14, she photographed the Euromaidan protests, in Kyiv, where more than a hundred people were killed. “You always expect everything will change, will get better,” she said. “And it doesn’t.”

Hrabarska read “Sapiens” three or four years ago. She told me that she had previously read widely in history and philosophy, but none of that material had ever “interested me on my core level.” She found “Sapiens” overwhelming, particularly in its passages on prehistory, and in its larger revelation that she was “one of the billions and billions that lived, and didn’t make any impact and didn’t leave any trace.” Upon finishing the book, Hrabarska said, “you kind of relax, don’t feel this pressure anymore—it’s O.K. to be insignificant.” For her, the discovery of “Sapiens” is that “life is big, but only for me.” This knowledge “lets me own my life.”

Reading “Sapiens” had helped her become “more compassionate” toward people around her, although less invested in their opinions. Hrabarska had also spent more time on creative photography projects. She said, “This came from a feeling of ‘O.K., it doesn’t matter that much, I’m just a little human, no one cares.’ ”

Hrabarska has disengaged from politics. “I can choose to be involved, not to be involved,” she said. “No one cares, and I don’t care, too.” ♦

https://ift.tt/39BhLOy

via The New Yorker

February 13, 2020 at 09:42PM

0 notes

Text

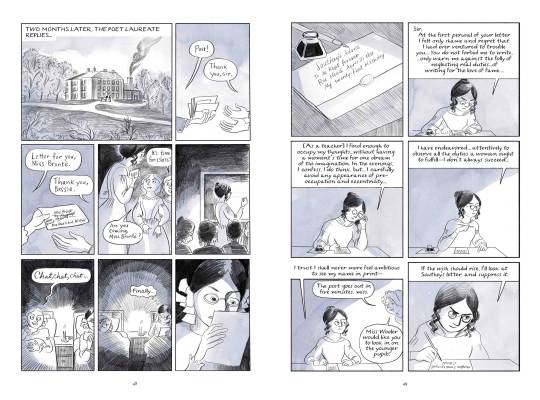

Blog Tour + #Review: CHARLOTTE BRONTE BEFORE JANE EYRE by Glynnis Fawkes (w/ #Giveaway)!

Welcome to Book-Keeping and my stop on the blog tour for the new graphic novel Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre by Glynnis Fawkes! I’ve got all the details on the book for you today, along with my review and a giveaway, so let’s get started.

About the Book

title: Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre

author: Glynnis Fawkes

publisher: Disney/Hyperion

release date: 24 September 2019

Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong!--I have as much soul as you,--and full as much heart!

Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre is a beloved classic, celebrated today by readers of all ages and revered as a masterwork of literary prowess. But what of the famous writer herself?

Originally published under the pseudonym of Currer Bell, Jane Eyre was born out of a magnificent, vivid imagination, a deep cultivation of skill, and immense personal hardship and tragedy. Charlotte, like her sisters Emily and Anne, was passionate about her work. She sought to cast an empathetic lens on characters often ignored by popular literature of the time, questioning societal assumptions with a sharp intellect and changing forever the landscape of western literature.

With an introduction by Alison Bechdel, Charlotte Brontë before Jane Eyre presents a stunning examination of a woman who battled against the odds to make her voice heard.

Add to Goodreads: Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre

Purchase the Book: Amazon | Kindle | Amazon Paperback | B&N | iBooks |

Kobo | TBD

About the Author

I'm a cartoonist and illustrator living in Burlington, VT.

My most recent book Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre, Center for Cartoon Studies Presents series, will be published in September 2019 by Disney/Hyperion. Also in September, Secret Acres will publish Persephone’s Garden, a collection of autobiographical comics that have appeared in the New Yorker and other places.

I began working on excavations as illustrator in 1998 and have worked on sites in Greece, Crete, Turkey, Israel, Cyprus, Syria, and Lebanon. I continue to work in Greece every year. My illustrations have been published in several books and many articles.

Many of my personal comics reflect a career in archaeology and family life. Greek Diary is about working on a dig and traveling with children. My drawings about my children were published regularly on Muthamagazine.com and were nominated for an Ignatz Award at the Small Press Expo in 2016.

Another project, Alle Ego, is about my first trip to Greece and how it launched my work in the direction of archaeology. A draft of this book won the MoCCA Arts Festival Award in NY in 2016. I drew most of it during a residency at La Maison des Auteurs in Angouleme, and I plan to return to work on this book in the future.

I’m currently working on a middle grade adventure set after the eruption of Thera in Late Bronze Age Greece.

Connect with Glynnis: Website | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | Pinterest | Tumblr | Goodreads

My 5-Star Review

I must admit from the start that I am an absolute Brontë sisters nerd and fangirl, so when I saw the announcement for this tour, I immediately jumped at the chance to take part. I have read all of the Brontë sisters’ books, as well as a variety of fictional accounts of their lives (one of my absolute favorite being Worlds of Ink and Shadow by Lena Coakley, my detailed review of which you can read here), and I was thrilled to add this graphic novel to my collection. Like Worlds of Ink and Shadow, Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre focuses on Charlotte’s childhood and young adult years, before she published Jane Eyre. While Charlotte is the main character, we also get to learn about her siblings Anne, Emily, and Branwell, and the closeness the four of them enjoyed. This focus on Charlotte’s formative years helps us to understand where the story for Jane Eyre came from, in addition to her other books.

I kept thinking, the whole time I was reading, that Ms. Fawkes has performed a heroic feat in condensing Charlotte’s story into a mere 92 pages, while including so many of Charlotte’s own words. I don’t know how she was able to do it, but she absolutely does get across the importance of Charlotte’s upbringing and her experiences as a teacher and private governess as it relates to her writing. It is amazing that she is able to tell this story in so few pages and in graphic novel format, but she does an amazing job. The illustrations are delightful, as well, and do such a great job evoking the desolate moors upon which the Brontë sisters grew up, the constrictions upon women at the time, the bleakness of the school the sisters went to (and where their two older sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, both died), and the difficulty Charlotte and her sisters had in getting their work published.

All told, I love this graphic representation of the formative years of Charlotte Brontë and what led to the incredible stories she wrote and that remain such an integral part of the canon today. Whether you are already a Brontë fan or are just learning about Charlotte and her sisters, I encourage you to pick up this graphic novel that is short yet packed full of Charlotte’s own words. I highly recommend Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre to any literature or history fan!

Rating: 5 stars!

**Disclosure: I received a copy of this book from the publisher for purposes of this blog tour. This review is voluntary on my part and reflects my honest rating and review.

About the Giveaway

Three (3) lucky winners will each receive a finished copy of Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre by Glynnis Fawkes! This one is US only and ends 4 October 2019. Enter via the Rafflecopter below, and good luck!

a Rafflecopter giveaway

About the Tour

Here is the full tour schedule so you can follow along!

Week One:

9/2/2019 - Odd and Bookish - Excerpt

9/3/2019 - Country Road Reviews - Excerpt

9/4/2019 - dwantstoread - Review

9/5/2019 - A Dream Within A Dream - Excerpt

9/6/2019 - Lifestyle Of Me - Review

Week Two:

9/9/2019 - Christen Krumm, Writer, Reader, Serious Coffee Drinker - Review

9/10/2019 - Careful of Books - Review

9/11/2019 - Character Madness and Musings - Excerpt

9/12/2019 - Fictitiouswonderland - Review

9/13/2019 - Fyrekatz Blog - Review

Week Three:

9/16/2019 - Little Red Reads - Excerpt

9/17/2019 - Book-Keeping - Review **you are here!

9/18/2019 - Life of a Simple Reader - Excerpt

9/19/2019 - Kati's Bookaholic Rambling Reviews - Excerpt

9/20/2019 - Inspired by Savannah - Review

Week Four:

9/23/2019 - History from a Woman’s Perspective - Review

9/24/2019 - Wishful Endings - Excerpt

9/25/2019 - Just Another Reader - Review

9/26/2019 - Jade Writes Books - Review

9/27/2019 - Rants and Raves of a Bibliophile - Review

Week Five:

9/30/2019 - two points of interest - Review

#charlotte bronte#charlotte bronte before jane eyre#Jane Eyre#bronte sisters#glynnis fawkes#graphicnovels#graphicnovel#graphic novel#yalit#ya lit#ya literature#book review#bookreview#5 stars#5 star#5 Star Review#5star#5stars#Blog Tour#rockstar book tours#rbt#disney books#Disney Hyperion#center for cartoon studies#historical

0 notes

Text

Sensor Sweep: Genre Magazines, Mort Kunstler, Vampire Queen, Boris Dolgov

Publishing (Forbes): Today, the number of science fiction and fantasy magazine titles is higher than at any other point in history. That’s more than 25 pro-level magazines, according to a count from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, amid a larger pool of “70 magazines, 14 audio sites, and nine critical magazines,” according to Locus Magazine.

Publishing (Jason Sanford): For the last few months I’ve been working on #SFF2020: The State of Genre Magazines, a detailed look at science fiction and fantasy magazine publishing in this day and age.This report is available below and can also be downloaded in the following formats: Mobi file for Kindle, Epub file for E-book Readers, PDF file. For this report I interviewed the editors, publishers, and staff of the following genre magazines. Many thanks to each of these people. The individual interviews are linked below and also contained in the downloadable Kindle, Epub, and PDF versions of the report.

Science Fiction (New Yorker): In her heyday, Russ was known as a raging man-hater. This reputation was not entirely unearned, though it was sometimes overstated. Of one of her short stories, “When It Changed,” which mourns a lost female utopia, the science-fiction novelist Michael Coney wrote, “The hatred, the destructiveness that comes out in the story makes me sick for humanity. . . . I’ve just come from the West Indies, where I spent three years being hated merely because my skin was white. . . . [Now I] find that I am hated for another reason—because Joanna Russ hasn’t got a prick.”

Comic Books (ICV2): Blaze Publishing has reached an agreement with Conan Properties International that will allow it to publish U.S. editions of the Glénat bande dessinée series The Cimmerian, ICv2 has learned. The Glenat series adapts Robert E. Howard Conan stories originally published in Weird Tales into comic stories that Ablaze describes as “the true Conan… unrestrained, violent, and sexual… just as Robert E. Howard intended.”

Fantasy (DMR Books): To cut straight to the one-line review: Jamie Williamson’s The Evolution of Modern Fantasy (Palgrave McMillan, 2015) is a must-read if you’re at all interested in how the popular genre now known as “fantasy” came about. Even if it’s a little difficult to obtain and get into. Williamson is both an academic and “one of us.” A senior lecturer in English at the University of Vermont, he’s taught a number of classes that I’d love to audit (Tolkien’s Middle Earth, Science Fiction & Fantasy Literature, King Arthur).

Historical Fiction (Jess Nevins): Hereward the Wake was written by the Rev. Charles Kingsley and first appeared in as a magazine serial in 1865 before publication as a novel in 1869. It is a fictionalization of the life of the historical Hereward the Wake (circa 1035-circa 1072), a rebel against the eleventh century Norman invasion and occupation of England. Although he became a national hero to the English and the subject of many legends and songs, little is known for certain about Hereward, and it is theorized that he was actually half-Danish rather than of Saxon descent.

Art (Mens Pulp Magazines): During the summer and fall of 2019, we worked with the great illustration artist Mort Künstler, his daughter Jane Künstler, President of Kunstler Enterprises, and Mort’s archivist Linda Swanson on an art book featuring classic men’s adventure magazine cover and interior paintings Mort did during the first major phase of his long career. That book, titled MORT KÜNSTLER: THE GODFATHER OF PULP FICTION ILLUSTRATORS, is now available on Amazon in the US and worldwide. It’s also available on the Barnes & Noble website and via the Book Depository site, which offers free shipping to anywhere in the world.

Gaming (Tim Brannon): Palace of the Vampire Queen. In the beginning, there was a belief that all DMs would naturally create all their own adventures and there was no market for pre-written ones. The only printed adventure out at this time was “Temple of the Frog” in Blackmoor. Seeing a need, the Palace of the Vampire Queen was written by Pete and Judy Kerestan. Yes, the very first adventure was co-written by a woman. The first edition was self-published, followed by a second and third edition by Wee Warriors (1976 and 1977) and distributed exclusively by TSR.

Fiction (DMR Books): Last summer, I was fortunate enough to acquire the copyrights to Merritt’s material from the previous owners. Along with the rights, I received a few boxes of papers, which I’ve enjoyed going through during the past few months, and which I anticipate will provide me with many more enjoyable evenings perusing them. Among these were papers relating to Merritt and the Avon reprints. Some of this takes the form of correspondence between Merritt’s widow, Eleanor, and the literary agent she’d engaged for Merritt’s work, Brandt & Brandt. Others are contracts with Avon, as well as Avon royalty statements.

Pournelle (Tip the Wink): Here, all of Pournelle’s best short work has been collected in a single volume. There are over a dozen short stories, each with a new introduction by editor and longtime Pournelle assistant John F. Carr, as well as essays and remembrances by Pournelle collaborators and admirers.” My take: I enjoyed this a lot. It had been a while since I read any Pournelle (and then almost always with Niven). I’m now tempted to reread The Mote In God’s Eye.

Gaming (Reviews From R’lyeh): Ruins of the North is an anthology of scenarios for The One Ring: Adventures over the Edge of the Wild Roleplaying Game, the recently cancelled roleplaying game published by Cubicle Seven Entertainment which remains the most highly regarded, certainly most nuanced of the four roleplaying games to explore Tolkien’s Middle Earth. It is a companion to Rivendell, the supplement which shifted the roleplaying game’s focus from its starting point to the east of the Misty Mountains, upon Mirkwood and its surrounds with Tales from Wilderland and The Heart of the Wild to the west of the Misty Mountains.

Art (Dark Worlds Quarterly): Being an artist for Weird Tales was not a fast track to fame and fortune. It is only in retrospect that names like Hugh Rankin, A. R. Tilburne, Hannes Bok, Lee Brown Coye and Vincent Napoli take on a luster of grandeur. At the time, the gig of producing illos for Weird Tales was low-paying and largely obscure. Some, like Lee Brown Coye, were able to establish their reputations in the art world after a long apprenticeship in the Pulps. Most are the select favorites of fans. Boris Dolgov was one of these truly brilliant illustrators who time has not been as kind to as should be.

Tolkien (Karavansara): But what really struck me in the whole thing was something that emerged from the debate: some fans said the novel should have been translated by a Tolkien fan, and by someone with a familiarity with fantasy. But other have pointed out that The Lord of the Rings is not fantasy. And my first reaction was, what the heck, with all those elves and orcs, wizards and a fricking magical ring and all the rest, you could have fooled me.

Tolkien (Sacnoth’s Scriptorium): So, I’ve been thinking back over Christopher Tolkien’s extraordinary achievements and wondering which was the most exceptional. A strong case can be made for the 1977 SILMARILLION. In retrospect, now that all the component pieces of that work have seen the light in the HISTORY OF MIDDLE-EARTH series we can see just how difficult his task was, and how comprehensively he mastered it. Special mention shd be made of one of the few passages of that work which we know Christopher himself wrote, rather than extracted from some manuscript of his father: the death of Thingol down in the dark beneath Menegroth, looking at the light of the Silmaril.

Art (Illustrator Spotlight): Many of you have seen some of the pulp covers he created; most likely those for The Spider, Terror Tales, Dime Mystery or Dime Detective. I was recently reading a blog post about David Saunder’s book on DeSoto (I can’t find the link to the blog anymore), and one of the comments was about how the commenter didn’t believe that DeSoto deserved a book, having painted only garish, violent covers. My reaction was immediate; I felt like telling the commenter to go forth and multiply, in slightly different words of course.

Martial Arts (Rawle Nyanzi): Yesterday, I put up a blog post where I showed videos discussing Andrew Klavan’s comments regarding women and swordfighting (namely, that women are utterly useless at it.) As one would expect, this has been discussed all around the internet, but much of it involves virtue signalling. To cut through a lot of that fog, I will show you a video by medieval swordsmanship YouTuber Skallagrim, in which he discusses the comments with two female HEMA practitioners — one old, one young.

Fiction (Black Gate): Changa’s Safari began in 1986 as a concept inspired by Robert E. Howard’s Conan. I wanted to create a heroic character with all the power and action of the brooding Cimmerian but based on African history, culture and tradition. Although the idea came early, the actual execution didn’t begin until 2005, when I decided to take the plunge into writing and publishing. During its creation I had the great fortune to meet and become friends with Charles R. Saunders, whose similar inspiration by Howard led to the creation of the iconic Imaro. What was planned to be a short story became a five-volume collection of tales that ended a few years ago with Son of Mfumu.

Gaming (Sorcerer’s Skull): The Arimites have the gloomy environment of Robert E. Howard’s Cimmerians and elements of a number of hill or mountain folk. They’ve got a thing for knives like the Afghans of pulp tradition with their Khyber knives, though the Arimites mostly use throwing knives. They’re miners, and prone to feuding and substance abuse, traits often associated with Appalachian folk. I say play up that stuff and add a bit from the Khors of Vance’s Tshcai–see the quote at the start, and here’s another: “they consider garrulity a crime against nature.”

Sensor Sweep: Genre Magazines, Mort Kunstler, Vampire Queen, Boris Dolgov published first on https://sixchexus.weebly.com/

0 notes

Link

THERE’S A CERTAIN BRAND of criticism reserved for overstuffed, bizarre stories — it consists of the critic throwing up her hands in despair and saying: “Sure, whatever, why not?” It usually has to do with a lack of narrative cohesion or consistency — but mostly it’s about the element of surprise. Whodunits rely on surprise by flouting expectation: when the audience least expects something, swerve. Poke the bear after insisting it’s harmless, then reveal it is the murderer. Avant-garde works rely on surprise by flouting tradition: baffle, provoke. Poke the bear, make it dance and tell you a campfire tale about a murderer with a heart of gold. Two men called Vladimir and Estragon wait, forever, by a tree, and it’s probably much ado about nothing? Charles Kinbote pretends to care about a long poem, but really he cares only about himself, and some country named Zembla? Sure, whatever, why not?

The Argentinian writer César Aira — I bought all 16 of his English-translated books, including his most recent, Birthday — is precisely the sort of writer to elicit that reaction. Take a centuries-old epiphany about a pirate treasure by a translator who appears at the exact location, and is immediately made rich. Or a headless dog who, without any semblance of a brain or any kind of nervous system, survives to adulthood. These are Aira stories, and if I’m being totally honest, they don’t strike me as particularly avant-garde. Most things that actually happen in an Aira story, in the sense of a plot, happen pretty quickly. The rest is digression, mostly Aira straight-up messing with the reader. On the basis of sheer experimentalism, there’s no Pale Fire–like flouting of formalism here. The prose is candid. There’s always some narrative. On the basis of grand metaphor, again, no dice. If you’re waiting to understand something, you won’t.

But that’s not true. Aira isn’t without tradition or precedent — he’s just hard to pin down. The provocations are too capricious; the subversion is undercut instantly with a cruel reminder of reality or lack thereof. The closest tradition is probably Dadaism in its insistence on nonsense verse. Then again — at least according to a profile in The Nation — Aira’s destabilizing of reality is supposed to be deeply political, the works of a man who was “a young militant leftist, with the notion of writing big realist novels.” But at least from the translated works that precede Birthday, there is little narrative coherence to his radicalism. If there is, it’s like an editor returning a draft with the sentence, “TK TK capitalism TK TK.”

Who says that’s a bad thing? There’s a big show of laziness, too, which is very much a conventionally bad thing (Aira claims to improvise entirely and never rewrite). In Varamo, the titular character contemplates the disbursement of his salary in counterfeit money:

After all, Panama was a young nation, and situations of this kind require a minimum of history. It was complicated enough to establish the laws that govern the legal printing of money, an operation which, in its early stages, is bound to resemble counterfeiting. So if he were caught trying to use fake money — as he was sure he would be — the case would set a precedent; the sentence and the legal concept would have to be invented, made up from scratch, given a comprehensible form and surrounded with discourse to make them plausible. All of which would involve intellectual and imaginative work, but that didn’t make the prospect any brighter for him.

Is this also what Aira the writer is doing? In the very first paragraph, the narrator promises us a book about how Varamo wrote a celebrated masterpiece of Central American poetry in one night. We never get that book, so it doesn’t matter.

Or actually, maybe it does matter, because on the night in question — before the writing begins — Varamo meets two spinsters who smuggle golf clubs and pontificates that for them, “the national was a categorical imperative,” the same as for printing money, even counterfeit money. A little detective work: Varamo the character, a hapless bureaucrat, writes his masterpiece in 1923 when Argentina was still one of the richest countries in the world (soon to change in the wake of a military junta taking power in 1930). It makes some narrative sense that the novel seems so very anxious about the black market and counterfeit money (in 1920s Argentina, an abundance of counterfeit money was quite real). In which case the plot is the digression, and everything else is vital.

So I suppose it is political after all: the idea that the bizarre is also real, from the writer who once chastised other Argentinian writers for being too unconcerned with the country’s “social and economic problems.”

How does one tell the difference? Conversations is easy. The post–Cold War United States manipulated the lives of people in ex-Soviet states, causing reality itself to having a strange in-between-y status. Others are harder. In The Literary Conference, giant silkworms engulf and destroy a whole city, by way of a cloning machine. In The Little Buddhist Monk, a suicidal Chinese pony imported to Korea jumps off a pagoda, because it has no knowledge of the toxic Korean herbs it would have otherwise required. In The Miracle Cures of Dr. Aira, Dr. Aira tries to cure cancer using “screens” that include or exclude everything in the universe: “[H]is right hand […] divided up the joys and sorrows of Muslims; his left was pulling a little on another screen that excluded too many apples.” In The Seamstress and the Wind, a woman drives a car “as light as a yawn” which can contain “only one not very fat person […] and only if they were tightly-folded up.” It’s going somewhere, or nowhere. It’s a mystery or, a soda bubble, or a magnet car. It may or may not occupy space. “The proverb says mystery does not occupy space,” Aira writes. “All right, fine; but it crosses it.”

If that isn’t the writer’s version of throwing his hands in the air and saying, “Sure, whatever, why not,” I don’t know what is.

¤

But there’s a pretty major problem with all that I’ve said thus far, though it’s the consensus view — and that is the idea that Aira is somehow colossally enigmatic. Alena Graedon in The New Yorker calls Aira’s novels “difficult to classify.” K. Reed Petty in Electric Literature insists that the reader not “try to understand.” Aura Estrada, for the Boston Review, wrote that Aira’s work showed that “the literary enterprise […] [is] pregnant with possibilities.”

The problem is that those pregnant possibilities do indeed mean very real things: both for Aira and fellow Latin American absurdist writers with whom he shares a tradition. The literary scholar Ericka Beckman reminds us that what people find colorfully absurd about Latin American fiction is often very real. A Latin American dictator in Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch sells the entire Caribbean Sea to the United States; the body of water is subsequently moved to the Arizona desert. But it’s the actual privatization of ordinary things in Latin American countries that lend the story its gravitas. “In 1999,” Beckman writes, “the Bolivian government signed a $2.5 billion contract to privatize the city of Cochabamba’s water supply.” Under the proposed agreement, a San Francisco–based consortium “was to own all of the city’s water resources, even the rain that fell from the sky.” The tradition also extends to Borges and Bolaño, the latter of whom called Aira “one of the three or four best writers working in Spanish today.” But whereas Bolaño is considered to have written some of the most innovative critiques of globalization and fascism, Aira is merely “not meant to be understood.” If that’s all Aira means to us, then we’ve lost something of immense value.

Indeed, much of Aira can be construed as a new articulation: not an idiosyncratic style from an exotic backwater, but something creatively new, a giant middle finger to the Western literary enterprise. In The Proof, for instance, a teenage lesbian couple (“Mao” and “Lenin”) try to seduce a shy girl and subsequently commit a violent act in a supermarket as a “proof of love.” According to Latin American literary scholar Héctor Hoyos, The Proof is about “destabiliz[ing] sexual orientation” and the inherent violence of ordinary commerce in the supermarket. That’s reasonable, and strikes me as a far better way to understand Aira than claiming he’s not meant to be understood.

How to explain the gonzo story that is How I Became a Nun? The story is narrated by a six-year-old child (boy or girl?), and begins when the father treats the child to ice cream for the very first time, only to become incensed when the child despises it, tries it himself, finds it revolting, and violently kills the ice cream vendor. Soon after, the child reports that “my body began to dissolve … literally … My organs deliquesced … turning to green and blue bags of slime hanging from stony necroses … bundles of ganglia.” Turns out there is a wave of lethal food poisoning, by way of cyanide contamination, across Argentina and neighboring countries.

The boy/girl is, as are many of Aira’s characters, named César Aira, and the child’s affliction affects not just the body but the telling of stories. It’s all very paradoxical; insistent that language is “anti-mimetic” and bears no resemblance to reality. In Conversations, a story-within-other-stories, the narrator immediately digresses: “[A]n aside: a memory can be identical to what is being remembered; at the same time it is different, without ceasing to be the same.” This is all the stuff of Barthes and Derrida, the idea being that nothing in the novel is real (or even helpfully un-real). If Aira really is Barthes and Derrida in plot form — poststructuralist children’s books, imagine that! — then thank goodness that these stories are so fun. With a lesser writer the hand-wringing would never end.

So, let me contradict myself again. Once you get the hang of it, Aira’s politics aren’t particularly difficult to suss out. Most of the time, when Aira says something, you should probably just believe him. One of his major themes is: People get these ideas, and it doesn’t really matter if they are true. A second major theme is of Authorial “exclusion”: a litany of unreliable narrators wax lyrical about closed loops or circles in narratives (Barthes would be proud). A third: If we wrap something simple into something indirect and symbolic, people are drawn in, even though we’re cheating. Boy/girl César decides to deceive a doctor: “The aim of my ruse was to make her think I had something ‘difficult’ to express.”

Let’s do Aira a favor and dispose of Barthes and Derrida because, simply put, we don’t need them. I’m not scoffing at literary theory. I simply think it makes more sense to privilege Aira’s own words. Here’s a stronger case. Every so often, you find something that has to be Aira the writer speaking directly to the reader. In Conversations, the narrator laments the plot weren’t more outlandish: “That […] would have resulted in a much more interesting story, right?” In How I Became a Nun, Aira is baffled by a singer, broadcast on television, who cannot sing: “[To] the Tone Deaf Singer herself … perhaps she is still alive, and remembers, and if she is reading this … My number is in the telephone book.”

I’m fairly certain that Tone Deaf Singer is really out there somewhere. I hope she got in touch with César Aira, and that they talked.

¤

So much is made of Aira’s oddities, plot twists, and diversions, but I want to convince you that it’s the emotional effect that should make you stick around. I read Ghosts last of all, and I was entirely unprepared for it. Shorn of quick swerves, Ghosts is perhaps his most poignant. Set at a construction site for a bourgeois condominium, the world-building is exquisite; no other translated work of his is as detailed or as tremulous. There aren’t surprises in the manner we’ve become accustomed to: the eccentricities feel familiar; the philosophizing logical.

Set over the course of a New Year’s Eve, Ghosts is only somewhat about ghosts — the ones that the workers and the immigrant family squatting at the site see, but the families soon to move in don’t. It’s a book preoccupied with the juxtaposition of the rich and the poor, while also fixated on the sadness and peril in the lives of an enormous cast of characters, slowly spiraling down to focus on the oldest daughter of the central squatter family.

It is uncommonly gentle and empathetic for Aira. But then it was with Ghosts that I realized that although Aira ensures the ludicrous to keep the pages turning, almost every one of his works also contains within it much sincerity and earthiness. The Proof reminds me of the wonderful film Tangerine in its spiky, breakneck earnestness. The Linden Tree proudly wears its heart on its sleeve: at turns nostalgic and charmingly silly. In almost every one of the others, something makes me go weak in the knees. It may even be called a “realist” oeuvre. Birthday — the most recent translation, released in February — makes this case best of all. A beautiful memoir inspired by Aira’s 50th birthday, Birthday is worthy of serious philosophical attention: lengthy digressions tell one explicitly how Aira perceives the past, the present, and the future, but what clarifies all his work is how he how he wrangles strangeness out of the quotidian. The phases of the Moon are a source of self-deprecation; the first encounter with electricity, fraught with worry; politics, a consequence of some remaining static as others charge ahead through life; death, as a proxy for history and how much we miss every day, “like Rip Van Winkle.” Everything in life is ultimately pretty strange, a cheeky rejection of the idea that “avant-garde” even exists.

So, ultimately three very simple things about César Aira: 1) He is exactly the sort of writer to elicit the response, “Sure, whatever, why not?” 2) He gets people all in a tizzy about his “tradition.” Okay, sure — though he’s already said a whole bunch about Borges. 3) He is most certainly meant to be understood. Of course he is. Don’t be daft! Just listen.

¤

Kamil Ahsan is a biologist and historian with a doctorate from the University of Chicago. His work has appeared in The Rumpus, Dissent, The Millions, The American Prospect, The A.V. Club, and Jacobin, among others.

The post Meant to Be Understood: On César Aira’s Complete Translated Works appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2U3522J

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

IN 2014, Nigerian author Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani argued in The New York Times that African literature, in order to be successful, had to appeal to “Western eyes.” The claim was prompted by a friend of Nwaubani’s who had told her, a bit inelegantly, that her first novel, I Do Not Come to You by Chance (2009), had figured out “what the white people wanted to read and given it to them.”

Nwaubani thought her friend had a point. I Do Not Come to You by Chance is about the so-called 419ers, the Nigerian “princes” who lure the unsuspecting into email scams — a phenomenon that has long since become an international joke and a callous way of dismissing what most are surprised to learn is the seventh-most-populated nation in the world. To be sure, the novel is in some ways familiar: a young man accidentally comes of age while simultaneously becoming ensnared in a criminal enterprise. Think Dickens via Doctorow. But it’s more than just a template, and the protagonist’s Uncle Boniface, the criminal mastermind who goes by the more colorful moniker “Cash Daddy,” looms large mid-book with a speech asserting that, no matter how much money may be bilked from the First World during a few years of internet tomfoolery, this loss will be dwarfed by the wealth, culture, blood, and potential that has been stripped from the entire African continent in the much vaster scam of colonialism, which lasted decades and lingers still. I may be putting a few words into Cash Daddy’s mouth, but by the time he’s done, you’re almost ready to start Googling Nigerian princes so you can cut a few checks.

I Do Not Come to You by Chance was critically well received (it won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book from Africa, among other honors), but I doubt it was the commercial blockbuster that Nwaubani’s cynical friend either feared or hoped it might be. The book is now a decade old, and in the years following its release, Nwaubani turned more toward journalism, becoming a chronicler of an endless smorgasbord of Nigerian oddities for the Times, the BBC, the Guardian, the Thomson Reuters Foundation, and, most recently, The New Yorker, which in July published Nwaubani’s account of her family’s history of trading — rather than being — slaves. All the while, Nwaubani has carefully avoided indulging in the kinds of stereotypes that appeal to Western eyes, and which “tend to form the foundations of [African writers’] literary successes.”

Somewhere in there came the Lost Girls. Yet even saying it that way is wrong, because Boko Haram was wreaking havoc and stealing Nigerian children long before the mass abduction of students in April 2014 that finally captured Michelle Obama’s — by which I mean the world’s — attention. Since then, Nwaubani has become the go-to authority on what is known locally as the “Chibok Girls.” She penned a number of articles about the kidnapping and its aftermath; she co-wrote a half-fiction, half-nonfiction volume on the episode with Italian journalist Viviana Mazza that appeared in Italy in 2016; and she served as location producer for a documentary on the subject that will be released this October.

Most important, the event returned Nwaubani to fiction, and her new novel, Buried Beneath the Baobab Tree, is both a harrowing account of a horrific event and a slyly trenchant criticism of all those who believe the tragedy would be easily remedied by simply bringing the girls home.

***

Being one of those books that is based on recent and all-too-real events, you kind of know what’s going to happen: the narrator is one of the abducted girls; her benign family life and promising education are interrupted by the theft of the young women; and, in the would-be caliphate of the Sambisa Forest of northeastern Nigeria, the Chibok girls are subjected to rape, murder, impregnation, and indoctrination; at last they are rescued by the Nigerian army and an international community that has finally decided to pay attention to what happens in Africa.

Early in the book’s extended preamble — as vague references to Boko Haram recur like the evil soon to manifest in a horror film — we are told the creation myth of the baobab tree. Eons ago, the story goes, a god in heaven hurled a gigantic tree down to Earth; it planted itself face down in the dirt, but continued to grow — which is why baobabs look upside-down, their roots all up in the air.

Such is the novel itself. The story is delivered in discrete chunks, a fragmented narrative like a choppy radio signal, and the result is a kind of upside-down root system of anecdotes, news reports, and riddle games. Western celebrities, we learn, loom in Nigeria like heathen deities from some demented Valhalla, and laptops are a mechanical oracle that permit communion with an artificial divine. The story reads easily, but there’s something lurking in the texture of the book, something lodged deep down in its point of view that the Western canon doesn’t have a name for — it’s first-person narration told from the perspective of someone lacking Western self-consciousness. Even the “I” is a kind of mournful collective identity.

Buried Beneath the Baobab Tree is being pitched as a Young Adult title — it has been published by Katherine Tegen Books, an imprint of HarperCollins that specializes in stories for even younger readers. The truth, however, is that the novel has far more in common with Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) than with any contemporary children’s book. Like Offred, Nwaubani’s narrator has no name apart from the one she is given after her abduction (Salamatu — Arabic for “safety”), and her story too breaks off abruptly after the Chibok girls are rescued. Atwood’s epilogue — an in-the-distant-future academic presentation on Offred’s manuscript, by then a historic curiosity — is matched here by a brief afterword by Mazza, who historically contextualizes Nwaubani’s novel and in the process accidentally confirms Atwood’s claim that her novel wasn’t really fantasy because everything in it was happening to real women somewhere in the world.

Yet a YA imprint may be a perfect fit for Nwaubani, if only because her story so often concerns itself with myth, lore, folktales, and children’s stories. Periodic epigraphs from Robert Browning’s “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” serve as a constant reminder of Nwaubani’s more fundamental concern, and of her awareness that fairy tales were originally much more than a cute way to put American children to sleep. Nigerian children too, we are informed, long for stories, but when the children of the narrator’s village are told a folktale one evening, they spend the rest of the night debating its meaning. Eventually, as the horror approaches, we begin to put the pieces together: the Sambisa Forest in northeast Nigeria is where the really wild things are. When Salamatu is finally rescued, a Western aid worker gives her a copy of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964), as though Willy Wonka has something to say to a girl who has by now been raped and stoned, and who is carrying the child of her abductor.

Once upon a time, fairy tales served the purpose of introducing children to the stresses and dangers of the adult world that awaited them. Not anymore — or at least not in the West, which giddily transforms Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” into Disney’s Frozen (2013). Nwaubani is on to all that: buried deep down beneath this baobab of a book are the charred remains of the fairy tale itself. When the Chibok girls were abducted, the call went out around the world: #BringBackOurGirls. Which is fine, so long as you recall that Africa had good witches and bad witches long before Dorothy did, and that #BringBackOurGirls is in no way the same happy ending as three taps of your ruby slippers. [h/t]

#adaobi tricia nwaubani#nigeria#nigerian author#nigerian authors#african author#african authors#books#los angeles review of books#i do not come to you by chance#sambisa forest#salamatu#chibok girls#bringbackourgirls#bring back our girls#fairy tale#fairy tales#afican fairy tale#african fairy tales#nigerian fairy tale#nigerian fairy tales#lit#literature#afican literature#nigerian literature#book review#book reviews#the lost girls#boko haram#viviana mazza#buried beneath the baobab tree

0 notes

Link

“The Afterlives.” By Thomas Pierce. Riverhead Books. 366 pages. $27.00.