#bedřich smetana

Text

Bedřich Smetana serving cunt

Alois Jirásek serving cuntor

#litomyšl kamarádi#mnohé krásy#bedřich smetana#alois jirásek#český blog#český tumblr#litomyšl#czech republic

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

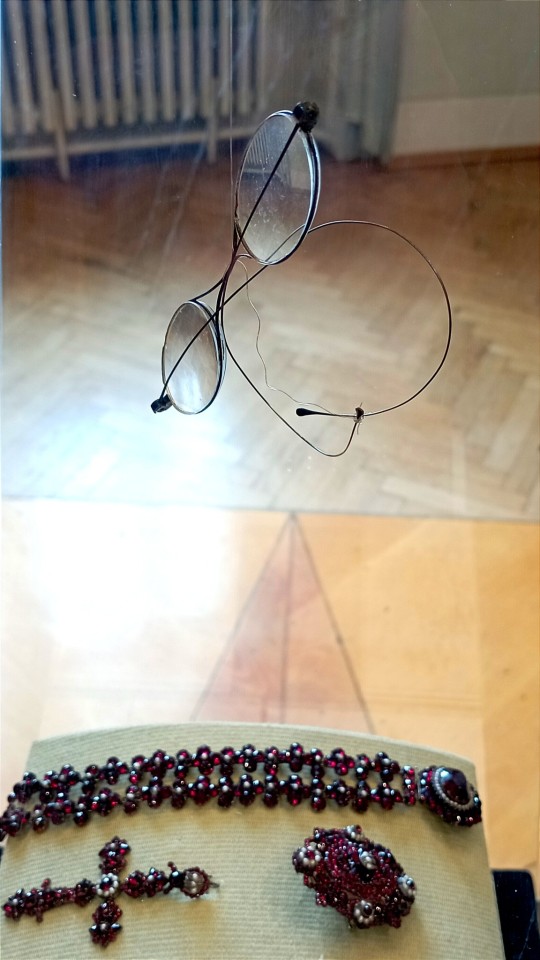

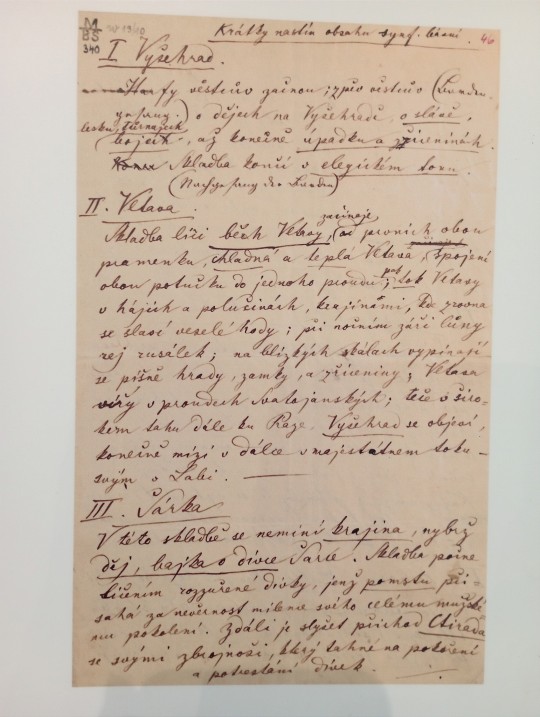

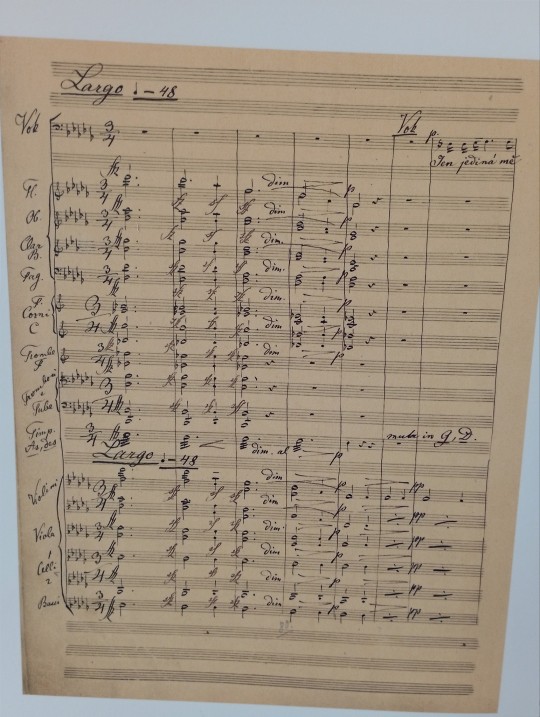

02.03.24 • Bedřich Smetana Museum • Prague

#because where else should i spend the 200th anniversary of the birth of one of my favourite composers?#bedřich smetana#prague#czech#classical music#filetmignon talks

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

B. Smetana (1824-1884) — String Quartet No. 1 in E minor "From my life"

Performers / MSQ: Wojciech Koprowski — violin Aleksandra Bryła — violin Michał Bryła — viola Marcin Mączyński — cello

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#johann sebastian bach#pyotr ilyich tchaikovsky#wolfgang amadeus mozart#ludwig van beethoven#gioachino rossini#scott joplin#antonio vivaldi#john cage#jules massenet#robert schumann#edward elgar#hermann necke#johann strauss II#bedřich smetana#georg friedrich händel#franz schubert#juventino rosas#frédéric Chopin#georges bizet#edvard grieg#john philip sousa#franz liszt#felix mendelssohn-bartholdy#johannes brahms#joseph haydn#françois-joseph gossec#leo delibes#amilcare ponichelli#friedrich burgmüller

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A review of a 1945 production of Bedřich Smetana's "Die verkaufte Braut" conducted by Anton Paulik:

"23. Juli 1945. Diese Oper gefiel mich sehr, sehr gut. Hilde Konetzni und Anton Dermota sangen fein."

From a copy of the libretto, found on a public shelf in Vienna in July 2023.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

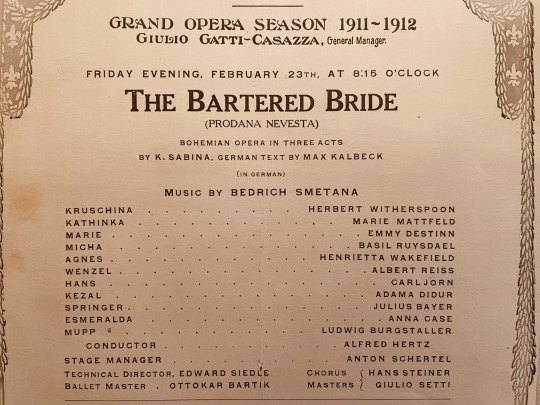

Here we see a cast list from The Metropolitan Opera 1912. The opera “The Bartered Bride” from Bedrich Smetana had until today 86 performances at the MET. A very good cast at this evening exactly 111 years ago.

#The Metropolitan Opera#The Metropolitan Opera House#The Met#Metropolitan Opera#Metropolitan Opera House#Met#The Bartered Bride#Bedřich Smetana#Smetana#Prodaná nevěsta#The Sold Bride#opera#bel canto#classical music#music history#composer#classical composer#chest voice#Herbert Witherspoon#bass#Emmy Destinn#dramatic soprano#Basil Ruysdael#Adam Diour#Henriette Wakefield#mezzo soprano#Anna Case#lyric soprano#Albert Reiss#tenor

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Raya Recounts: a brand-new series of overly-detailed opera summaries with unsolicited commentary!

I hope you’ll forgive the irregular time gaps between the episodes, I guess it depends on how much I like the opera I’m covering (or at least, how easy I find it to watch).

Episode 5: Prodaná nevěsta

Prodaná nevěsta (literally, “The Sold Bride”, but usually translated as “The Bartered Bride”) is a 3-act comic opera by Bedřich Smetana. Smetana is known as one of the most internationally famous Czech composers in classical music, if not the most famous after Antonín Dvořák. He is well-known for developing a style of music that contains a genuine Czech characteristic, which of course made him quite associated with Czech nationalism.

Smetana’s most famous piece by far is the symphonic poem Vltava (better known as Moldau) from his symphonic suite Má vlast. You will recognize the melody, especially if you grew up with either Baby Einstein or Little Einsteins. (Also, he composed this piece when he had gone completely deaf, much like what happened to Beethoven. So yeah, double praise.)

The libretto for Prodaná nevěsta was written by Karel Sabina, who also wrote the libretto for Smetana’s previous (and first) work Braniboři v Čechách. This time, it seems to be an entirely original story created by Sabina for the opera itself. This work actually exists in 4 versions; it was revised 3 times, and the final version, which replaced all previously-present spoken dialogue with recitatives, is the one that is usually performed nowadays.

While it has a rocky history, this opera is one of Smetana’s better-known works, and his best-known opera, and it remains often performed worldwide. Because Czech was not a widely spoken language back in the days, international performances at the time were often sung in German instead, under the title Die verkaufte Braut (meaning the same thing as above, obviously), and with all the character names Germanized. This German version is still often performed nowadays, especially in German-speaking countries (no shit!). In general, the opera is often performed in translation, including the Met’s 1978 production which was sung in English.

This opera is also well-known for having 3 orchestral dances based on Czech folk dances, one in each act, which are well-known enough to be performed on their own in concert settings.

This is dedicated to @notyouraveragejulie, for suggesting the title. This is one of my absolute favorite operas ever, so I’m really, really excited to publish this and convince other operablr regulars to join me in the cult of loving this opera.

As usual, solo characters’ named bolded and potentially bad translations for the important numbers. This is my first time tackling a non-Italian opera, and this presents itself as twice as much of a challenge, since whereas I know quite a bit of Italian from learning it in Conservatory and from listening to a lot of operas the way you would pick up Japanese from watching a lot of anime (and also knowing French and Spanish), I do not speak a word of Czech, so just a (major) heads up. At least Wikipedia literally lists all the numbers this time.

Apologies to all Czech speakers.

Spoilers, of course!

We first get a super-energetic overture in F major which, much like the overture for Episode 3′s selection, I would like to classify as being in sonata form, and is well-known enough to be often performed on its own in concert settings (and Mahler very briefly quotes it in the last movement of his Symphony No. 1).

The curtain then opens on Act 1, at a village square somewhere in Bohemia (a region in modern-day Czechia), probably around the time the opera was written (so the 19th century at the very least). There is a fair going on, and the villagers are singing all about enjoying life while it lasts because marriage supposedly leads to strife and unhappiness (Chorus: Proč bychom se netěšili; usually translated to “Let’s rejoice [and/let’s] be merry”, but it seems to more directly translate to “Why wouldn’t we enjoy” or something like that).

As the theme of the chorus takes a minor key, we zoom in on one young couple among the villagers; the guy, Jeník, a tenor, asks Mařenka, his soprano girlfriend, why she looks so gloomy. She explains that her mother told her that the guy she is betrothed to is coming to the village to visit her. Jeník tells her not to worry, to trust him (Jeník) and to keep her will strong. The chorus of villagers tells her to stop lamenting because her faithful love for Jeník will definitely end up earning a blessing, then sings a reprise of the opening chorus before going off to party a little more.

Once they are left alone, Mařenka remains pessimistic, and Jeník asks what happened exactly. Mařenka tells him that the farmer (as in, landowner) Mícha and his son are coming to the village to ask for her hand in marriage. Jeník asks what her answer will be, but Mařenka despairs because it would be difficult for her to say that she is already in love with another, since this is a promise that her father is bound to fulfill.

She then remarks on his reserved attitude, and tells him to assure her that he doesn’t have another lover somewhere or something like that, and he affirms that he absolutely doesn’t. Mařenka tells him that should she ever find out something like that about him, she would get really angry (Aria: Kdybych se co takového; “If I ever learn”). She asks him why he left his home and his entire former life behind, and remarks on how his whole past is shrouded in mystery, which her father has mentioned to her several times.

Jeník tells her about his Tragic Past™: he is the son of a pretty well-to-do father, but after his mother died, his father married a woman who ended up kicking him (Jeník) out. So he basically set out into the world and supported himself by entering the service of other people. He and Mařenka go on about how a stepmother’s hate can really be hurtful, but that committed love like theirs cannot be hurt by pains from the past, and they promise to love each other forever, and they are usually just being the most cutie-patootie thing ever, depending on the production (Duet: Jako matka požehnáním... Věrné milování; “As a mother’s blessing... Faithful love”).

After that, Mařenka hears her parents coming, looking for her. Jeník, not wanting them to see him, bids her a heartfelt goodbye, before they each exit the stage separately. Now enter Krušina, a baritone peasant, and Ludmila, a soprano, both Mařenka’s parents, along with Kecal, a bass and a marriage broker who is very much a businessman in terms of attitude. Kecal is in the midst of discussing the whole arranged marriage business; he assures Krušina that it’s all gonna go smoothly thanks to his sharp skills, and that should Mařenka object and stuff, he will make sure that she does what she is told (Trio: Jak vám pravím, pane kmotře; usually translated to “As I’m saying, dear fellow”, but it contains the word “kmotr”, meaning “godfather”).

While Krušina expresses satisfaction with this arrangement, Ludmila says it’d be better to take the time to discuss this with the bride-to-be. But Kecal remains very confident that their firmness and his wit alone will win over any objections the bride-to-be has over this marriage. Ludmila says that it depends on what the bridegroom himself is like, but Kecal continues to dismiss this.

We then learn through Krušina that Tobiáš Mícha is a childhood friend of his, and that he has two sons: one Jeník by his first wife (wait, that same Jeník we met minutes ago??? We’ll just have to wait and see...), and one Vašek by his second wife, but he (Krušina) doesn’t know either son. Despite that, he promised years ago that he would give his daughter’s hand in marriage to Mícha’s son. Ludmila asks which son Kecal is talking about, he replies that Mícha technically only has one son: Vašek. He dismisses the other one as a vagrant and a rascal, and says that no one knows about him (rude).

Krušina inquires about what kind of boy Vašek is like, and asks why Kecal didn’t bring him with him right now. Kecal starts rattling off all of Vašek’s virtues (Trio: Mladík slušný; “A decent young man”): he is a young man quiet as a lamb, he supposedly has no faults or flaws, he has a lovable soul, he is neither too much this nor too much that either physically or mentally, is in good health, and especially, he is set to inherit a farm worth thirty thousand (the currency is not stated here, but later in the libretto, it’s shown to be guilders). What can anyone want more from a perfect bridegroom like him??? Krušina and Ludmila believe his words to be true, and all three repeat their lines for a few more measures.

Then Mařenka comes back in, and asks her parents why they were looking for her (Quartet: Tu ji máme; “Here we have her” or something like that). Kecal says that he was asking her parents if she has someone she is in love with, and tells her that if she doesn’t, he has a young man to introduce her to. Krušina and Ludmila assure her that she will meet him first, and if she doesn’t like him, she can turn him down. Kecal announces that a deal has been reached, and that everything will be settled once Mařenka says yes. Mařenka objects that this can’t be settled as quickly as he says, and that he doesn’t even suspect that there is a hitch in this whole thing. But Kecal doesn’t care, claiming that he never quits whatever he puts his mind to.

Mařenka finally admits that she is already in love with another. Kecal tells her to dump him and let him seek his fortune elsewhere. Mařenka retorts that she has already given him her word, that she has already signed a contract for this. Kecal replies that he gives zero fucks, that they can tear up the contract, and then it’s just a whole back-and-forth argument between them. Kecal says to trust the absolute wonders of his wit, and everything will work out no matter what, because his mind is apparently just so amazing that it can succeed where no one else can (damn, that bloated ego gives me a lot of miscellaneous déjà-vu).

Mařenka claims she knows that Jeník won’t give her up, and is ready to stake her life on this (Recitative: Jeník neupustí; “Jeník won’t let go”). Krušina says that whether or not Jeník would give her up doesn’t really matter, because he has made a promise to Tobiáš Mícha in front of witnesses. At Ludmila’s inquiry, Kecal pulls out a contract, which he shows to have been signed by Mícha, Krušina and witnesses. Mařenka says it doesn’t matter, since she and Jeník didn’t know anything about that contract and that they still won’t give each other up, then she leaves.

Kecal gets briefly frustrated at how twisted the world is (uhm, because a girl actually knows her rights as an individual person??), and Krušina asks him where Mícha and his son the Perfect Bridegroom™ actually are right now, as it would be nice for him to actually talk to Mařenka. Kecal agrees, but explains that the boy is not used to talking to women, he is incredibly shy. Krušina briefly remarks on how hard this will make the wooing process. Kecal suggests that Krušina try to meet Mícha elsewhere “by chance”, as the square is about to get noisy now that the villagers are getting ready to dance (man, the people in this village love to dance and party!). This is indicated by the beginning of a polka (a type of Bohemian (as in, from the region of Bohemia) folk dance with a 2/4 time signature) in the orchestra. Meanwhile, he (Kecal) resolves to find Jeník and try to talk to him. Both leave.

The villagers come back onstage as the polka starts picking up. This is the first orchestral dance interlude; many productions will bring in actual dancers to show off what they’ve got, and also sometimes to excuse choristers who can’t dance very well... Anyway, the chorus sings all about the bounciness of the polka, and the curtain falls as everyone present is having a great time (Finale: Polka... Pojď sem, holka, toč se, holka; “Come here, girl, spin, girl”. You might recognize it if you’re familiar with Baby Einstein. The orchestral version linked is without chorus, tho).

Act 2 opens inside an inn in the village. Jeník and a male chorus of peasants are seated at a table drinking beer. The chorus sings the obligatory opera drinking song all about the wonders of beer, all the typical stuff about how it’s a gift from heaven, it reduces troubles to nothing and it gives strength and courage (Chorus: To pivečko; “That [little] beer”).

Jeník, ever the tenor, claims that love is better than either wine or beer, as it’s the only lasting source of happiness. The chorus tenors acknowledge that he’s currently head over heels in love, and the basses point out Kecal, who is sitting somewhere in the background, and they warn him (Jeník) not to let that old dude spoil his happiness in love. Kecal finally speaks up, claiming that good advice and money are the only two important things in life, and that whoever uses them sensibly will be well-anchored. As the other men sing a reprise of the beer chorus, Kecal and Jeník continue arguing the merits of either money or love over beer and honestly everything else respectively.

Then the orchestra starts playing a furiant (another Bohemian folk dance, of a particular fast and fiery character, with the time signature either alternating between 2/4 and 3/4 or, as in this case, in 3/4 with lots of accents) (Dance: Furiant. It’s less well-known than the other orchestral dances in this opera, but do listen to it here). A lot of productions will showcase male dancers jumping and spinning energetically, and I’m so here for it. After that, everyone probably either shrinks to the background or leaves altogether, for the sake of the next scenes.

A new arrival shows up slowly onstage; it’s none other than Vašek himself! A stuttery, big baby tenor, he is indeed as shy as we have been told he was, if not so much more. In a stuttering song well emphasized by accents in the orchestra, he muses about how his mother told him that he should be getting married, and he adds that if he doesn’t, he will become the laughingstock of the village (Aria: Ma-ma-ma-matička; “Mo-mo-mo-mother”). (Yes, I know making fun of stuttering hasn’t aged well. But.)

Then, Mařenka shows up (interesting note: in the score, it says that they bump into each other and burst into laughter, but I don’t think I ever saw this in a production). She recognizes Vašek but pretends to be someone else (Recitative: Vy jste zajisté ženich Krušinovy Mařenky?; “Surely you are the groom of Mařenka Krušinova?”). When he asks how she knew who he is, she points out his outfit, which should logically be ridiculously tacky clothes typical of a sheltered rich kid about to get married. She also adds that the entire village is talking about him and pitying him.

He asks why, and she says that “Mařenka” already has someone else in her life, and that she is planning on deceiving him (Vašek) and making his life hell in order to make him die soon. The simple-minded Vašek is confused at first and then terrified, as his mother told him that he has to get married. Mařenka points out that he can still get married, since there are plenty of girls around here for him to choose from.

When he expresses enthusiastic interest, she tells him about a girl she knows who supposedly has been madly love for him for a long time now (Duet: Známť já jednu dívčinu; “I know a girl”). Reassuring all his worries about “Mařenka” and his mother, she describes that girl as pretty and young just like “Mařenka”, and also adds that should he refuse her (that girl), she would get so upset that she would probably try to kill herself. She adds in some (probably fake) crying, and the ensuing conversation between her and Vašek leads to her easily tricking him into falling for her charms, seemingly framing the whole thing as that girl being none other than herself (not smart, Mařenka, not smart).

She continues wooing him, telling him she would love him like a baby in diapers or something (I mean, he IS a big baby after all), and makes him swear to never marry “Mařenka”. While Vašek refuses at first, she manages to make him tearfully agree by threatening bad things happening to whoever courts “Mařenka”, and she makes him swear to never want anything to do with her, to never want to see her or hear of her. And after a recapitulation of the initial theme of the duet (the bit with Mařenka telling Vašek about a girl who is in love with him), they both leave.

Then, Jeník and Kecal return to the foreground, the latter in the midst of trying to negotiate a deal with Jeník, to get him to give up Mařenka in exchange for a rich wife, with very little regard for literally anything else (Recitative: Jak pravím, hezká je; “As I’m saying, she is pretty”). Of course, Jeník remains absolutely firm on his refusing to give up Mařenka, but Kecal chides his sentimentality, telling him that money is more important. They have a whole back-and-forth about this whole business, with Kecal especially stressing that marrying a girl only brings benefits if she has money, because apparently wives always cheat on their husbands at some point, and them having money at least leaves them with something (se-xist, se-xist) (Duet: Nuže, milý chasníku; “Now, my dear gentleman” or something like that). (We also learn that Jeník comes from far away, someplace at the Moravian borders, but that detail is not important for now.) Kecal continues to try and persuade Jeník to give up Mařenka, in exchange for a rich girl who owns/is set to inherit a cottage, some animals, a piece of field and a new cupboard (because yes, Kecal, as @notyouraveragejulie so kindly pointed out long ago, a new cupboard will totally seal the deal), and most importantly, MONEY!

And if Jeník accepts to give up Mařenka, he will receive a hundred guilders (Recitative: Odřeknešli se Mařenky; “If you give up Mařenka”). Jeník refuses, claiming that it’s too little money for such love. Kecal increases the amount to two hundred, but Jeník still claims it to be too little. When Kecal increases the amount to three hundred, he says that should Jeník continue to refuse, he will use all his ressources to drive him out of here. Jeník initially refuses when he hears that Kecal will be the one giving him the money, since he wouldn’t sell Mařenka to him for anything, but Kecal clarifies that he’s not the one who wants her, since he already has a wife (wait, what?!! How did I not know that??? Anyway, I pity her, whoever that woman is), and he’s actually negotiating on behalf of the son of Tobiáš Mícha.

This time, Jeník (HMMMMMMMM????? Has Jeník realized something????????) seems to accept the deal, but adds in a condition that no one but the son of Tobiáš Mícha can get Mařenka, and insists on making it an actual clause in the contract. Kecal accepts the deal, and starts going to call in witnesses, but Jeník also asks to add in a condition that as soon as Mařenka and Mícha’s son have consented to the marriage, Krušina’s debt to Mícha shall be entirely cancelled. Kecal agrees, and leaves.

Jeník is left alone, and to make sure that the audience fully understands what is happening in case the production and/or the singer didn’t make the earlier realization very clear the moment the name “Tobiáš Mícha” was uttered, he gloats over his successful manipulation of Kecal’s deal. Then he sings sentimentally about how could anyone ever believe that he would actually sell his darling Mařenka, his angel, for literally any amount of money; there is no one else in the world like her and he would do anything for her, he just loves her so much (Aria: Až uzříš... Jak možná věřit; “When you see... How could you believe”).

Then, as the orchestra plays the first theme of the overture, Kecal comes back in, calling a chorus of villagers, including Krušina, to come in and witness the signing of the contract (Finale: Pojďte, lidičky; “Come, people”). Jeník publicly reads out the terms of the contract, in which he officially agrees to give up his girlfriend to no one but the son of Tobiáš Mícha, IF he (the son) truly loves her and agrees, in front of witnesses, by his own free will, to marry her. The chorus and Krušina are in awe at Jeník’s willingness to make such a selfless sacrifice.

BUT THEN, Kecal clarifies that Jeník is receiving three hundred guilders from this deal, meaning that he basically sold Mařenka in exchange for this money. This time, the mood completely changes, with the villagers and Krušina calling Jeník a scoundrel for doing something as shameful as selling his girlfriend like this. When Kecal tells Jeník and then the witnesses to sign the contract, Jeník signs it as “Jeník Horák” (often translated as “Jeník of the mountain[s]”). As Krušina signs, he (Krušina) declares being glad to have finally known his true nature, and the curtain falls as the chorus continues to shame Jeník for selling his sweetheart. (In the 2019 Garsington production, which happens to be the first one I ever watched (I needed subs) and which updates the setting to the 1950s, someone even splashes Jeník in the face with beer!! Just mentioning it because I love this detail.)

Act 3 takes us back to the village square as in Act 1. Vašek is all alone onstage, pondering out loud in an equally stuttering second aria, absolutely terrified of the possibility of “Mařenka“ poisoning him and stripping him of everything (Aria: To-to mi v hlavě le-leží; “It-it’s in my head” or something like that).

But his musings are interrupted by the approaching sounds of a trumpet, a piccolo and some percussions playing a march. Other villagers probably also come to see what’s going on. It’s a traveling troupe of performers! (The original Czech refers to the performers as “comedians”, but it does have many characteristics of a traveling circus.)

The leader of the troupe (the original Czech refers to him as the “principal comedian” and Wikipedia calls him the “Ringmaster”, but I’ll just call him “the leader”), a character tenor who doesn’t need a lot of singing skills because his part, at least in this recitative, mostly consists of repeated notes, announces that they will be putting on a supposedly never-seen-before show later today, consisting of one Esmeralda Salamanca performing various acrobatic feats, a Native American from the faraway Tahiti islands swallowing forks and knives (yes, this did NOT age well), and most importantly, a real tamed American bear who will be dancing a French Cancan with Esmeralda (Recitative: Ohlašujeme slavnému publikum; “We announce to the [famous] audience” or something).

The leader gives everyone who is watching a quick preview of the upcoming show, during which the performers, who in many productions are played by actual circus performers, get a chance to show off their skills (or lack thereof, probably for the sake of foreshadowing some later revelations about the shadiness of the troupe, as in the 1982 Vienna production) as the orchestra plays a skočná (yet another Slavic folk dance, this one being of a particularly rapid characteristic and usually with a 2/4 time signature. I noticed the name “skočná” resembles the Czech “skočit”, which means “jump”, but I’m not sure if they are connected) (Dance: Skočná, often better-known as the “Dance of the Comedians”. Listen to it here, conducted by the famous Herbert von Karajan. It’s mostly well-known for being used extensively in the Road Runner cartoons).

After the dance is finished, Vašek expresses excitement about the upcoming show (and also ogles Esmeralda’s legs) (Recitative: Je-je-je-je! To bude hezké!; “Oh-oh-oh-oh! It’s going to be lovely” or something like that). Esmeralda, a soprano, approaches him and asks if he will be attending the show. He answers that he will, and that he is looking forward to seeing her tightrope walking.

But then the “Native American”, a bass (who by the way speaks fully fluent Czech with zero written-in accent, making me strongly believe that he’s an in-universe redface character or something like that), comes in running, telling the leader that the guy who was supposed to do the dancing bear number got so drunk that he can hardly stand on his feet. The desperate leader considers using some boy from the village as a replacement, but the Native American points out that word might get out and the troupe will be laughed at, and besides, they have to find someone who can fit properly inside the bear suit, and there is barely any time left before the show anyway. Meanwhile, Vašek is becoming more attracted to Esmeralda. The men notice that the bear suit might fit Vašek quite well. The leader sends the Native American and the other performers (except Esmeralda) away while he talks to Vašek, and the rest of the troupe exists as a reprise of the march plays.

Now that the three are left alone, the leader and Esmeralda use Vašek’s very obvious infatuation to persuade him to join the troupe, with Esmeralda’s love as a reward. The leader in particular tells him all about the life of a performer, including plenty of debts money, freedom and a highly regarded status. Of course, they do the thing of not pressuring him, telling him to only try it once today, and Esmeralda demonstrates the Cancan part that he is supposed to perform. At first, Vašek fears what his mother will think, but the leader and Esmeralda assure him that she won’t recognize him because he will be fully dressed in an animal suit (Duettino (Italian diminutive for duet, i.e., “little duet”): Milostné zvířátko uděláme z vás; “We will make a lovely little animal out of you”). Then the two leave.

Vašek is left alone for a short while, trying to process all that has been going on, between the marriage and the performers’ troupe (Recitative: Oh, já ne-nešťastný!; “Oh, unhappy me!”). In come Vašek’s father, Mícha himself, a bass, and mother, Háta, a mezzo, accompanied by Kecal. Háta asks Vašek why he looks so sad. He says he is afraid. She asks why, and tells him to get married because apparently everything will be alright once he gets a wife. Kecal and Mícha try to get him to sign the contract to marry Mařenka, but Vašek says he doesn’t want to, to the great confusion of the other three (Quartet: Aj! Jakže, jakže?; “Ay! How, how?”). Vašek claims that Mařenka would poison him, and the others ask him where he got that silly idea. He says that some pretty girl who likes him told him that today. When they ask him if he knows her, he admits that he doesn’t, before leaving. Kecal, Háta and Mícha suspect that there’s something fishy in there, and Kecal decides to get to the bottom of this whole thing.

At this moment, Mařenka comes in with Krušina and Ludmila. Mařenka has been told about how Jeník basically sold her, and she is in complete, desperate denial about this whole thing (Ensemble: Ne! Ne, tomu nevěřím; “No! No, I don’t believe it”, with a few more no’s that I was too lazy to add). Kecal proves it by showing her the contract that Jeník signed to give her up in exchange for three hundred guilders. Mařenka is completely upset at this supposed betrayal, especially since Jeník swore that he would basically sacrifice the world for her. Krušina tries to reassure her that at least she know knows his true character. Kecal tries to get her to sign the contract to marry Vašek, but she refuses, claiming to prefer living alone forever without breaking her promise. Kecal and the two pairs of parents tell her that there is no way around that.

Kecal calls Vašek over, and he (Vašek) immediately recognizes Mařenka as the girl who told him all these scary things, and who also told him that she would love him (uh oh, uh oh. Mařenka, this is why I told you your scheme was not very smart!!!!). All the adults introduce her as his future wife. Vašek (who seriously has, as the French say, un cœur d’artichaut (“an artichoke heart”), meaning he falls in love wayyyyyy too easily) still claims to like her. Kecal tries to get them to sign the contract, but a weepy Mařenka claims to need a moment to think it over. Kecal and the two pairs of parents urge Mařenka to think very carefully about the choice she is about to make, and not to let her stubbornness get in the way because her happiness literally depends on this choice (Sextet: Rozmysli si, Mařenko; “Think about it, Mařenka”). Mařenka says she will think about it, and everyone but her leaves.

All alone, Mařenka expresses her extreme sorrow at Jeník’s betrayal and her crushed dream of love in one of ye long typical soprano aria of despair, even though it seems at some point that she still doesn’t entirely believe the whole betrayal thing, considering that maybe Jeník himself doesn’t even know about it (Aria: Oh, jaký žal!... Ten lásky sen; “Oh, what grief!... That dream of love”. Ngl, this moment really made me think of the stages of grief. We already have denial, bargaining and depression in there).

Jeník comes in running, calling Mařenka the star of his life and asking her how is their cause currently standing. Mařenka angrily rebuffs him (ah, there’s the anger!), asking how he could stoop so low as to literally sell her heart, and she asks whether he did actually do it, telling him to only answer either yes or no, nothing else. Jeník begs her to let him explain, but Mařenka refuses to hear his excuses and asks if he did sign that contract to sell her.

When he confirms it, she warns him to never come near her ever again, and declares that she will marry Vašek. Jeník bursts out laughing upon hearing this, which further angers Mařenka. Jeník again begs her to just let him explain his side of the situation, but she still refuses to listen. Jeník remarks on her stubbornness and asks if he could really look into her face if he really were guilty, to no avail. Ye typical operatic back-and-forth ensues (Duet: Mařenko má!... Tak tvrdošíjná; “Mařenka mine!... Are you so stubborn”. It’s actually my favorite musical bit in this entire opera. Listen to it here, sung by Peter Dvorský and Gabriela Beňačková; I used this specific recording in my 5th Opera(s) as Vines video. Mařenka sings two high C’s).

Kecal returns and tells Jeník that he will soon be getting his money, much to Mařenka’s disgust, and he asks Mařenka if she will marry Mícha’s son. Jeník replies that she will and that he swears that no one else is to have her. Kecal praises his sensibility and Mařenka calls him (Jeník) a scoundrel and a liar, and absolutely refuses to marry. Jeník asks Kecal what he would give him if he managed to persuade her, to Mařenka’s absolute anger and despair. Jeník gently tells her to trust him because Mícha’s son loves her so fucking much and there’s luck and happiness in store for her within this marriage, Mařenka continues despairing, and Kecal praises the wisdom of Jeník’s words and is seemingly just amused by the whole thing, and then they all agree that it is now time to bring in the parents and witnesses to put an end to this whole fuckery (Trio: Utiš se, dívko; “Calm down, my dear”).

Kecal leaves, and Jeník and Mařenka are very briefly left alone; he asks her if she still doesn’t understand what is really going on. She rebuffs him again and he steps aside. Then Krušina, Ludmila, Mícha, Háta and the chorus of villagers all come in. The chorus urges Mařenka to tell them her final decision (Ensemble: Jak jsi se, Mařenko, rozmyslila?; “How have you changed your mind, Mařenka?” or something like that). Aside, Mařenka looks forward to trick Jeník and get revenge on him by doing what he probably is not expecting. Then, she announces that she will do as she is asked (i.e., marry Mícha’s son). The chorus praises her decision and proclaims that the fuckery is now ended, and the wedding shall now take place.

Jeník steps forward, proclaiming that yes, the wedding shall now take place and that everyone will rejoice. The surprised Mícha and Háta immediately recognize him and ask where did he come from. Jeník addresses Mícha as “father” and muses that he has lived in a foreign place for a long time and that he suspects it is high time for him to come back home. Kecal is absolutely speechless upon hearing that this simple, poor boy is in fact Mícha’s eldest son, as he thought he was a soldier (I have no idea where that point came from). Jeník confirms again that he is indeed Mícha’s son, and clarifies that while he is no soldier, he did have to fight many personal battles with fate during his wandering days.

Háta retorts that he certainly had plenty of time for all the wandering around he did, and Jeník replies that he is all too aware that she had kicked him out, as he previously mentioned in Act 1. But he brushes it aside as no big deal, preferring to focus on his claim for Mařenka’s hand in marriage, which he says he is entitled to as a son of Mícha. He makes it clear that he actually tweaked the deal in his favor, and that there are technically two eligible sons for Mařenka to choose from. Mařenka finally understands where he is coming from, proclaims herself as belonging to him and joyfully throws herself in his arms.

Kecal completely despairs at his defeat by Jeník’s cunning trick, which apparently destroyed his reputation and honor. Everyone starts laughing at him, going on about how that wisdom of his which he has boasted so much about throughout the opera seems to have left him, and that what happened to him was pretty stupid (yes, Kecal, serves you right for being a pompous asshole who only cares about money) (note: it’s never indicated exactly, but because he is never mentioned after this scene either in the libretto or the score, one could assume that he leaves).

But these jolly happenings are interrupted by shouting noises backstage, followed by two boys running onstage, screaming in lines spoken rather than sung, about how the performing troupe’s bear has escaped and is running in this direction. Said bear comes onstage, and reveals itself to be Vašek in costume, telling everyone not to worry, as it’s only him. Everyone laughs. Háta scolds Vašek, calling him a fool, and then drags him offstage. Krušina tells Mícha that hopefully he will recognize that Vašek is still a bit young of mind, not ready for marriage yet. He and Ludmila encourage Mícha to make peace with his son Jeník, with whom he is finally reunited after such a long time.

Mícha blesses the couple (in the 1998 London production, he blesses them but also Vašek and Esmeralda, which I find kinda weird), and everyone present sings a happy chorus about faithful love saving the day, just as predicted in Act 1, and looking forward to the upcoming wedding (Finale: Pomněte, kmotře... Dobrá věc se podařila; “Remember, [neighbor]... A good cause has succeeded” or something like that). There is probably a lot of dancing going on, given the overall nature of this opera. The curtain falls on this celebration of love, and everyone lives happily ever after as far as we know.

The end! ❤❤❤ This has been an overly-detailed opera summary with unsolicited commentary, I hope you enjoyed ;)

- Raya / rayatii

(PS: I wanna give a quick shoutout to @notyouraveragejulie‘s liveblog of this opera, in particular that famous Czech TV movie from 1982 (no subs, unfortunately, which is a shame because it’s one of the absolute best productions available online), which influenced quite a bit of the commentary in this post. Yes, I know I’m the one who suggested it to you, but I didn’t have anyone to scream about this opera with!! This reminds me, I should rewatch this production sometime.)

(PPS: the score that I have, which is downloaded from IMSLP, actually contains an annex with a short duet between the leader of the performers’ troupe and Esmeralda, which is only one among the handful of numbers that were in early version(s) of the opera and that were discarded during revisions. This one is set at the exact moment where the leader is telling Vašek all about the abilities of a performer. I ran the lyrics through Google Translate, but I barely understood what they were all about, but they did have something to do with performing.)

(PPPS: I think I saw in at least one source something saying that Esmeralda is the leader’s daughter (which makes sense imo), but in all the links I have used while writing this post, I have never seen anything mentioning that, and I don’t know if I just hallucinated it or something?????)

#raya recounts#opera#opera summary#overly-detailed opera summary with unsolicited commentary#prodana nevesta#prodaná nevěsta#the bartered bride#bartered bride#smetana#bedrich smetana#bedřich smetana

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A colleague: It’d be cool if they somehow made a shot the beginning of Silmarillion, and how there are different melodies in the darkness and then they combine into one song and everything is created, i wonder what that would sound like...

Me: you mean, like the beginning of Smetana’s Vltava (Moldau)?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

El sueño de Smetana

Disponible en la edición impresa Abril-24 y en edición en PDF de Vallecas Va

También disponible en Ventana, sección cultural del Listín Diario.

Publicación relacionada:

https://otracarreraalanochecer.wordpress.com/2019/04/02/moldava-el-sueno-de-smetana/

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

Má vlast (My Country) : No. 2, Vltava (Moldau)

#music#bedřich smetana#smetana#just realized spotify shares are just previews#which is bullshit#youtube

0 notes

Text

Today's the bicentenary of Bedrich Smetana, grat composer and father of czech nationalism. Cheers to him!

0 notes

Text

youtube

CzechoSLOVAK singer Gabriela Beňačková-Čáp sings Libusa´s aria from opera Libuše by Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884).

Conductor: Vaclav Neumann

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#johann sebastian bach#edward elgar#sergei rachmaninoff#frédéric chopin#wolfgang amadeus mozart#georg friedrich händel#antonio vivaldi#richard wagner#pyotr ilyich tchaikovsky#johann strauss II#john williams#bedřich smetana#ludwig van beethoven#carl philip emmanuel bach#robert schumann#franz schubert#franz liszt#niccolo paganini#claude-achille debussy#gustav holst#edvard grieg#felix mendelssohn-bartholdy#erik satie#camille saint saëns#joseph haydn#antonín dvořák#luigi boccherini#guiseppe verdi#johann pachelbel

0 notes

Text

Vox Satanae - Episode #573: 16th-20th Centuries - Week of 2024 January 15

Vox Satanae – Episode #573

16th-20th Centuries

This week we hear works by Philippe Rogier, Giovanni Battista Fontana, Louis Couperin, François Couperin, Joseph Schmitt, Jan Václav Voříšek, Bedřich Smetana, Hanuš Jan Trneček, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and David Del Tredici.

147 Minutes – Week of 2024 January 15

Stream Vox Satanae Episode 573.

Download Vox Satanae Episode 573.

View On WordPress

#Bedřich Smetana#classical instrumental music#classical music#classical vocal music#david del tredici#François Couperin#giovanni battista fontana#Hanuš Jan Trneček#Heitor Villa-Lobos#Jan Václav Voříšek#Joseph Schmitt#Louis Couperin#magister gene#Philippe Rogier#radio free satan#vox satanae

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

The Snow Queen (Original inspired by The Moldau) The Piano Guys

#Bedřich Smetana#the piano guys#piano guys#the moldau#moldau#Vltava River#the snow queen#christmas#winter#music#classical music#jon schmidt#steven sharp nelson#Youtube

1 note

·

View note