#detroit industry murals

Text

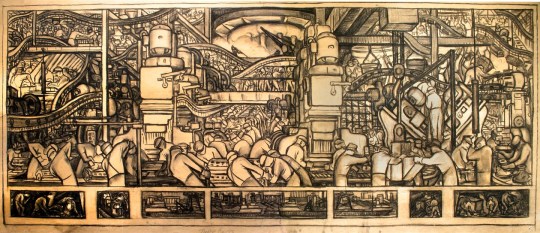

North wall, Diego Rivera, 1932-33, fresco at the Detroit Institute of Art in Detroit. aka Rivera Court at the (DIA)

More detailed views below

Detroit Institute of Arts

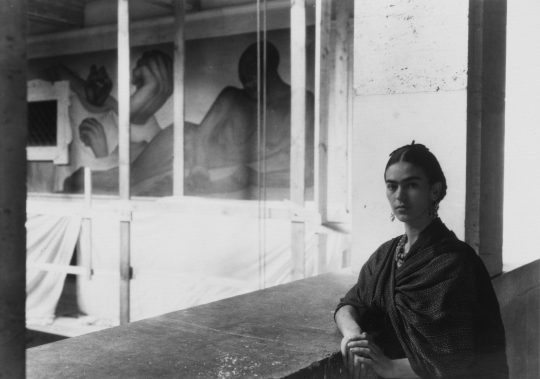

Diego Rivera working on fresco & checking in on Frida Kahlo, while they work.

Below - The Assembly of an Automobile (1932), a study for Detroit Industry fresco.

youtube

#art#murals#fresco#diego rivera#artists#detroit#frida kahlo#detroit industry#video#photography#vintage photography

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was unaware that Diego Rivera had done a set of massive fantastical-industrial murals for the Detroit Institute of Arts -- he was commissioned to do only a few panels but apparently wanted to do the entire courtyard, so one of the Fords (as in Henry) ponied up the cash for it. It’s absolutely fucking epic and spectacular; if you like the above you really should check them all out.

These are just two of my favorite panels; one shows the manufacture of chemical weapons (note bomb in background -- this was done in 1933 prior to the atomic bomb, so very prescient). The other is what I started thinking of as the Nativity of the Vaccine -- it’s a scene of scientists vaccinating a young child, but it’s deliberately designed to invoke images of the adoration of the Madonna and child. As the docent explained, the Madonna is also based on Jean Harlow, which caused a scandal when it was unveiled, “A Mexican Communist putting a sexpot film star into the role of the Virgin.” Absolutely compelling, richly-layered, beautifully wrought work.

[ID: Two panels from the courtyard murals; one shows a number of men in WWI-style gas masks, doing various industrial tasks including checking the pressure on a vat, while a large bomb hangs ominously in the background. The other shows a young child, draped in a towel, being held by a woman in a white dress while a man on the other side vaccinates the child in his arm. Three “wise men” scientists are at work in the background, and several farm animals used to develop vaccines are shown in the foreground.]

333 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Diego Rivera Industrial Workers, from the “Detroit Industry” Murals, Detroit Institute of the Arts 1932

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

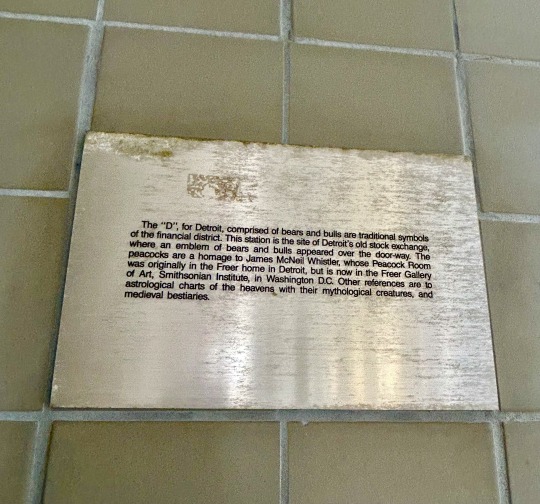

Art in the Stations: Fort/Cass

Overlooking the historic Detroit Club and the former Detroit Free Press building (now Press/321), Fort/Cass is one of the first People Mover stations I became familiar with due to its proximity to Rosa Parks Transit Center, John K. King Books, and the old Salvation Army thrift store (you can still check out Sally's on Fort)

"Untitled" by Farley Tobin is inspired by the Taj Mahal and created from 30,000 tiles to construct two murals. A Cranbook graduate, Tobin created and studied the history of ceramic tiles, architectural tile, and mosaic installations.

Her work can also be found in courthouses, museums, universities, and private homes.

Sandra Jo Osip is another Michigan-born artist who combines nature and her industrial environment. As you enter the Fort/Cass station, there are two six-feet high bronze sculptures to the left. "Progressions II" reminds me of shells with a floral flair, and was added to the station in 1992.

From Sandra's website, "In this time of uncertainty I began to offer hopefulness with bright and uplifting themes. Since flowers represent a new beginning and celebrate beauty, love hope and healing I used their forms, shapes and colors for the start of this new experimental journey."

I hope to meet these talented artists one day!

#artinthestations#detroitpeoplemover#dpm#detroit#downtowndetroit#sandrajoosip#sandraosip#Farleytobin#ceramics#tiles#pottery#sculpture#fortcass#detroitclub#detroitfreepress

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

38,000,000 Escaped - 10,000,000 Died

An unusual map supporting the fundraising efforts of Russian War Relief, Inc., an organization established after the Nazi invasion of Russia in 1941 to help the millions of refugees displaced within Russia by the invasion. The map of Russia has been reversed ("to compare the industrial west of Russia with the similar eastern area of the United States"): the Ukraine covers the eastern U.S., Moscow is near Detroit, and the Causcasus are in Oklahoma. The areas in grey were "occupied by the Nazis at the peak of the invasion." The capitol in Washington is burning, and the Nazi flag flies atop the Empire State Building. Other highlighted areas represent "giant industrial and agricultural communities" relocated to remote areas of Russia, e.g., Novosibirsk (Boise), Omsk (Salt Lake City) and Tashkent (Phoenix).

The map is undated, but because the text below the map says that "some of the survivors now are returning to homes recaptured by the Red Army," this map was probably produced after the Soviet victory at Stalingrad in 1943. The artist Elliott Anderson Means was raised in Texas, became an itinerant sign and mural painter in California, then studied at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles and the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts. He settled in New York, where he was a WPA artist in the 1930s; he created at least one other poster for Russian War Relief, "Help Put Him Back in Our Fight."

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Duille@DuilleDesign·

Detail: Detroit Industry mural, Detroit. Diego Rivera. c.1933.

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Untold story of Frida Kahlo to be re-enacted - WDET 101.9 FM

Detroit writer Louis Aguilar is hosting a multimedia event at 27th Letter Books in Southwest Detroit at 6 p.m. Saturday, Aug. 13.

Aguilar will discuss a little-known story about the well-known Mexican-American artist, Frida Kahlo.

He spoke with a woman over 25 years ago about a special moment she shared with Kahlo as a 10-year-old girl.

During this time, Diego Rivera worked in Detroit. Visitors were allowed to come and watch, and Kahlo often spent time with him as he painted the Detroit Industry mural at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

One day she spotted a little girl, gave her a tour and treated her like she was her own. Aguilar says the story the older woman told him about Kahlo was almost too good to be true.

“I realized as I started to do the research that so many of these stories were never told. I mean, I read books, I read the official documentation of the DIA and other scholars. And their [Kahlo and Rivera’s] interaction with the local Mexican community just did not seem to be on anyone’s radar, even though these artists were Mexican.” ...

... “I think that’s one of my favorite parts about living in Detroit … the places where you find these little stories.” ...

@danskjavlarna

#Frida Kahlo#GODDESS#Kindness#Children#Detroit#Michigan#Detroit Institute of Arts#Arts#Genius#godly#love#quality

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

WEEK 9_Cultural Materialism

In week 9, we studied "Cultural Materialism," showing how economics and technology shape cultural beliefs and behaviors. It emphasizes the influence of economic systems and technology, like social media, on daily life and consumption patterns. (Raine, 2024)

During our group activity, I chose to explore the significance of the MRT (Mass Rapid Transit) system as a representation of transportation infrastructure. This decision was motivated by its recent emergence as a focal point of development in my home country, Vietnam. The selection of this topic reflects Vietnam's commitment to sustainable national development and environmental conservation (Sustainable Infrastructure Investment by UN Environment Programme), drawing inspiration from the experiences of other nations.

In my Studio web layout project, I've integrated cultural materialism to great effect. By weaving in elements inspired by infrastructure, I've crafted visually engaging layouts that connect with my audience's cultural background. Prioritizing inclusivity, I've ensured broad appeal and accessibility by adhering to inclusive design principles, with every object in my website layout following the grid system.

In considering the influence of Cultural Materialism on art, one encounters timeless works that exemplify its impact. For instance, Diego Rivera's "Detroit Industry Murals" (1932–1933) and Ai Weiwei's "Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn" (1995) are notable examples. These artworks reflect the intersection of material conditions, cultural practices, and social relations, offering profound insights into the dynamics of their respective contexts. (Downs, n.d.) (Ai Weiwei’s “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995): - Bing, n.d.)

In conclusion, Cultural Materialism reveals how material conditions shape cultural phenomena, empowering designers to craft inclusive, culturally resonant designs for positive societal impact. Integrating this perspective enhances design outcomes and promotes broader societal awareness.

( 272 words)

References:

Sustainable Infrastructure Investment. (n.d.). UNEP - UN Environment Programme. https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/green-economy/what-we-do/sustainable-infrastructure-investment

Raine, S. (2024, January 24). What is Cultural Materialism? Perlego Knowledge Base. https://www.perlego.com/knowledge/study-guides/what-is-cultural-materialism/

Ai Weiwei’s “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995): - Bing. (n.d.). Bing. https://www.bing.com/search?pglt=161&q=Ai+Weiwei%27s+"Dropping+a+Han+Dynasty+Urn"+(1995)%3A&cvid=5340396a7f5b402e815440dd6634e43c&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOdIBBzQ1NmowajGoAgiwAgE&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=DCTS

Downs, L. (n.d.). Smarthistory – Diego Rivera, Detroit Industry Murals. https://smarthistory.org/diego-rivera-detroit-industry-murals/

0 notes

Text

Impact Detroit Magazine

Impact Detroit Magazine: Where Grit Meets Grace in Motor City's Renaissance

Detroit, a name synonymous with industrial might and musical soul, has experienced a rollercoaster ride in recent history. But amidst the shadows of hardship, a beacon of light shines: Impact Detroit Magazine. More than just a publication, it's a movement chronicling the city's vibrant resurgence, a platform for unsung heroes, and a catalyst for positive change.

Founded in 2011, Impact Detroit carved its niche amidst glossy, mainstream media's neglect of Detroit's raw, resilient spirit. Its pages pulsate with the rhythms of everyday Detroiters – the artists breathing life into vacant buildings, the entrepreneurs defying the odds, the community organizers stitching hope back into frayed social fabric. The magazine amplifies their voices, showcasing their struggles and triumphs with an unflinching honesty that both inspires and informs.

But Impact Detroit isn't solely focused on hardship. It celebrates the city's artistic renaissance, from the electrifying street murals to the intimate jazz clubs pulsating with raw talent. It highlights the burgeoning culinary scene, where chefs conjure culinary magic from locally sourced ingredients, breathing new life into forgotten neighborhoods. It embraces the fashion revolution, where designers weave threads of Detroit's heritage into bold, contemporary statements.

0 notes

Text

youtube

“Detroit Industry Murals” by #DiegoRivera

One of my faves! When I was a kid I went on a field trip to the Detroit Institute of Arts and saw his “Detroit Industry” murals and was completely taken with them. I was blown away and knew that Painting was something I needed to do. Seeing those paintings completely was the starting point of my work.

So next time your kid wants to go on a field trip, let them! Sign Them Up! Because it may just set them on their life’s work.

Birthday Remembrances. Today, Dec 8, 1886 – #DiegoRivera, Mexican painter and educator (d. 1957) was born.

( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diego_Rivera )

0 notes

Text

Diego Rivera: A Glimpse into the Master's Artistic Legacy

Introduction

Diego Rivera, a prominent figure in the world of art, left an indelible mark on the canvas of history with his awe-inspiring creations. His distinctive style, rooted in social and political themes, continues to captivate art enthusiasts worldwide. This blog post aims to delve into the brilliance of Diego Rivera's artworks offering a glimpse into his most iconic pieces, exploring the availability of his paintings for sale, and shedding light on the unique significance of his "Sugar Cane" series.

Diego Rivera's Artistic Legacy

Diego Rivera was a Mexican painter known for his large-scale murals and his deep commitment to depicting the struggles and triumphs of the working class. Born on December 8, 1886, in Guanajuato, Mexico, Diego Rivera art was deeply influenced by his political convictions, leading him to become a prominent figure in the Mexican muralism movement.

Rivera's unique style combined elements of cubism and impressionism, resulting in works that were not only visually striking but also politically charged. His murals, often commissioned for public spaces, conveyed powerful messages about social justice, labor rights, and the celebration of Mexican culture.

Diego Rivera's Iconic Artworks

"Man at the Crossroads" (1934): This monumental mural, commissioned for the Rockefeller Center in New York City, depicts a powerful juxtaposition of capitalist and socialist ideals. Unfortunately, the controversial nature of the piece led to its destruction, but Rivera's vision remains etched in the annals of art history.

"Detroit Industry Murals" (1932-1933): Housed in the Detroit Institute of Arts, this series of murals is a tribute to the industrial workers of Detroit. Rivera masterfully interweaves elements of technology, nature, and humanity, creating a visual symphony of labor and progress.

"The Flower Carrier" (1935): This iconic painting portrays a laborer carrying a massive load of flowers, symbolizing the weight of the working class. Rivera's use of bold colors and striking composition draws viewers into the heart of this poignant scene.

Diego Rivera Paintings for Sale

For art enthusiasts seeking to bring a piece of Diego Rivera's legacy into their homes, there are opportunities to purchase prints and reproductions of his renowned artworks. Several reputable art dealers and online marketplaces offer a curated selection of Rivera's paintings, allowing collectors to own a piece of this master's vision.

Diego Rivera's Sugar Cane Series

Among Rivera's most notable bodies of work is the "Sugar Cane" series, which he created during his time in Cuba. This series showcases Rivera's fascination with the labor-intensive process of sugar cane harvesting, a key industry in Cuba. Through vibrant colors and meticulous detailing, Rivera captures the essence of the workers' toil and the lush landscapes that define the sugar cane fields.

The "Sugar Cane" series serves as a testament to Rivera's ability to fuse the aesthetic with the socio-political. By immortalizing the laborers in his art, Rivera pays homage to the backbone of the Cuban economy, shedding light on their tireless efforts.

Diego Rivera Auctions: A Glimpse into Art History

For seasoned art collectors and enthusiasts, Diego Rivera auctions provide a unique opportunity to acquire original pieces from the maestro's repertoire. These auctions often feature a diverse range of Rivera's works, including sketches, paintings, and even personal artifacts, offering a rare glimpse into the artist's creative process.

Participating in a Diego Rivera auction is not only a chance to own a piece of history but also a way to contribute to the preservation of Rivera's artistic legacy. It allows collectors to become custodians of his vision, ensuring that future generations can continue to appreciate and be inspired by his extraordinary body of work.

Conclusion

Diego Rivera's artwork transcends time and borders, leaving an enduring legacy that resonates with art enthusiasts and activists alike. His ability to infuse profound social commentary into visually stunning creations is a testament to his genius. Whether through the availability of his paintings for sale or the exploration of his "Sugar Cane" series, Rivera's impact on the world of art remains immeasurable. As collectors engage in Diego Rivera auctions, they become part of a narrative that celebrates the power of art to inspire, provoke thought, and ignite change.

0 notes

Text

Georgia Bulldogs Shirt

DESCRIPTION

SHIPPING & MANUFACTURING INFO

TEEJEEP

Georgia Bulldogs Shirt

Among my duties was to keep seasonal decorations up to date. In this huge store that meant everything from designing window murals on glass to puppet displays in the Georgia Bulldogs Shirt and decorations hung from the ceiling. That year I decided I wanted to have Santa having a beach Christmas as a new thing- I had not seen it done before. The signpainter and I sat down and designed a scene where Santa’s sleigh was drawn by kangaroos and koalas sat on the sand with waves in the background. This was for the huge front windows. Well the signwriter went away and came back with stencils he’d cut of the scene and asked me if he could use them for other clients. I said yes, that year Santa on the beach became very popular!

buy it now: .Georgia Bulldogs Shirt

Miami Dolphins Waddle Waddle Jaylen Waddle Shirt

Fanatics Branded Heather Gray Kentucky Wildcats 2022 SEC Volleyball Regular Season Champions Shirt

Customized Buffalo Bills Ugly Christmas Sweater, Faux Wool Sweater, National Football League, Gifts For Fans Football Nfl, Football 3D Ugly Sweater, Merry Xmas – Prinvity

Kansas City Chiefs Est 1960 Baby Yoda Ugly Christmas Sweater, Faux Wool Sweater, National Football League, Gifts For Fans Football NFL, Football 3D Ugly Sweater – Prinvity

Kansas City Chiefs Est 1960 Baby Yoda Ugly Christmas Sweater, Faux Wool Sweater, National Football League, Gifts For Fans Football NFL, Football 3D Ugly Sweater – Prinvity

Kansas City Chiefs Est 1960 Baby Yoda Ugly Christmas Sweater, Faux Wool Sweater, National Football League, Gifts For Fans Football NFL, Football 3D Ugly Sweater – Prinvity

Homepage: limotees jeeppremium telotee

Gearbloom is your one-stop online shop for printed t-shirts, hoodies, phone cases, stickers, posters, mugs, and more…High quality original T-shirts. Digital printing in the USA.

Worldwide shipping. No Minimums. 1000s of Unique Designs. Worldwide shipping. Fast Delivery. 100% Quality Guarantee. to cover all your needs.

By contacting directly with suppliers, we are dedicated to provide you with the latest fashion with fair price.We redefine trends, design excellence and bring exceptional quality to satisfy the needs of every aspiring fashionista.

WHAT IS OUR MISSION?

Gearbloom is established with a clear vision: to provide the very latest products with compelling designs, exceptional value and superb customer service for everyone.

We offer a select choice of millions of Unique Designs for T-shirts, Hoodies, Mugs, Posters and more to cover all your needs.

WHY SHOP WITH US?

Why do customers come to

Well we think there are a few reasons:

BEST PRICING

Fashion field involves the best minds to carefully craft the design. The t-shirt industry is a very competitive field and involves many risks. The cost per t-shirt varies proportionally to the total quantity of t-shirts. We are manufacturing exceptional-quality t-shirts at a very competitive price.

PRINT QUALITY DIFFERENCE

We use only the best DTG printers available to produce the finest-quality images possible that won’t wash out of the shirts.

DELIVERY IS VERY FAST

Estimated shipping times:

United States : 1-5 business days

Canada : 3-7 business days

International : from 1-2 weeks depending on proximity to Detroit, MI.

CUSTOM AND PERSONALIZED ORDERS

Custom orders are always welcome. We can customize all of our designs to your needs! Please feel free to contact us if you have any questions.

PAYMENT DO WE ACCEPT?

We currently accept the following forms of payment:

Credit Or Debit Cards: We accept Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover, Diners Club, JCB, Union Pay and Apple Pay from customers worldwide.

PayPal: PayPal allows members to have a personal account linked to any bank account or credit card for easy payment at checkout.

0 notes

Photo

DiegoRiveraSelfPortraits Diego Rivera, was a prominent Mexican Painter. His Large frescoes helped establish the mural movement in Mexico and International art. Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted murals in, among other places, Mexico City, Charing and Cuernavaca, Mexico; and San Francisco, Detritus, and New York City United States. Inn1931, a retrospective exhibition of his works was held at the Museum of Morden Art in New york; this was before he completed his 27-mural series known as Detroit Industry Murals. Born: Guanajuato City, Mexico Died: November 24, 1957 (aged 70) Resting Place: Panteon de Dolores Nationality: Mexican Education: San Carlos Academy Known for: Painting, Murals Notable work: Man, Controller of the Universe, The History of Mexico, Detriot Industry Murals Movement: Cubism Realism Mexican muralism @ifyorjiekwe @benconnors @sparkyfish @richardjphoenix @rosie_ridgway @heartnsoulart @heartnsouleye @heartnsoulpics https://www.instagram.com/p/CjQgMx9DGzp/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Art in the Stations: Financial District

The Financial District is home to some of Detroit's most beautiful art-deco skyscrapers, including The Guardian, Buhl, Ford, and Penobscot Buildings. The People Mover Station features Aztec and Byzantine designs, integrating both the neighborhood's architecture and history.

The large hand-painted mural "'D' For Detroit" by Joyce Kozloff includes mythical animals, peacocks, the bull and bear of the Stock Exchange, and an illuminated "D." The mural design is inspired by the Guardian Building, the Fisher Building, and Diego Rivera's Detroit Industry Murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Kozloff created and hand-painted each tile herself in Kohler, Wisconsin at the John Michael Kohler Art Center. She has also worked on several other public art installations around the country, including Harvard Square and the 86th and Central Park Street Subway Station.

The peacocks were inspired by James McNeill Whistler's paintings, who had designed "The Peacock Room" at 49 Prince's Gate in London, owned by British shipping magnate Frederick Richards Leyland. The room was preserved in 1904 by Charles Lang Freer, who installed it in his home at 71 E. Ferry Avenue. The original wall is now on display at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

#artinthestations#detroitpeoplemover#financialdistrict#publicart#detroit#downtowndetroit#financialdistrictdetroit#freerhome#charleslangfreer#thepeacockroom

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virtual Sketchbook 2

1. Journaling

Unity and Variety: Unity is the completeness of a picture. Variety is the opposite of unity and provides diversity. An example of unity is Van Gogh famous painting “starry night” because it uses repeated colors and textures. An example of variety that I see in everyday life are the variety of trees and plants in my backyard.

Balance: achieved through symmetry or asymmetry. It’s similar to finding balance in life to improve your overall health. For me creating a healthy balanced life is spending time with my family, completing assignments, going to the gym and going to work without working overtime.

Emphasis and subordination: Emphasis is used to attract a viewer’s attention to the focal point. Subordination is the area around the focal point that is given less emphasis than the focal point. An example of emphasis and subordination would be the sky at night with the moon being the emphasis and the starts and sky the subordination.

Directional forces: Influences the way we look at an art piece by providing a path for the eyes to follow. Figure 4.12 from our text shows a painting by Fransisco Goya “BULLFIGHT”. He creates diagonals resulting in a sense of motion for the viewer..

Repetition and rhythm: Repetition is when visual elements are repeated over and over again to create a rhythm. An example of repetition and rhythm would be this beaded bracelet.

Scale and proportion: Scale refers to the size of one object compared to another. Proportion refers to the different sizes of the individual parts that make up one object. An example of scale would be a smart car next to semi-truck.

2. Writing and Looking

Diego Rivera’s DETROIT INDUSTRY, Fig 7.5. Diego Rivera created this fresco mural. A fresco mural is often a piece of art that cannot be bought or sold. Ford hired Rivera to create this mural showing the auto industry in Detroit. Rivera uses warm colors in this mural and paints people in different colors symbolic of the diverse workforce. The men working make up the focal point and the whitish grey of the machines in the background would be considered subordination.

3. Connecting art to your world

The colors blue, red, and yellow which are the primary colors are considered the most intense of all the hues. Going through school, I would and still to this day buy the blue colored paper to write notes in during class and to study before an exam. I feel like the value of the color blue is calming and relaxing. My favorite color is green. I love the color green because we live in a world where there is a lack of it. Green for me represents nature health and life.

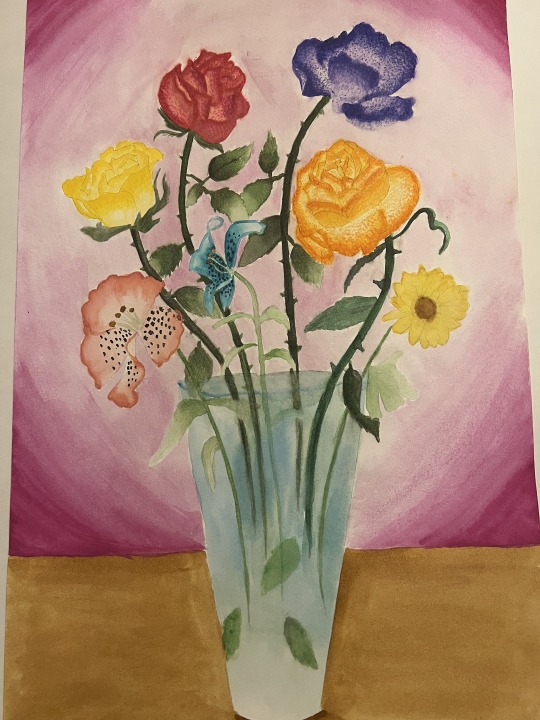

4. Art project- Artist’s choice

I made this watercolor painting to represent comfort, love and affection. I love when my husband brings me flowers to provide comfort during times where I’m in a tough spot. It reminds me of how much he loves me. There are times where all you need is that comforting feeling and thats what the flowers make me feel.

0 notes

Text

Rivera, Kahlo, and the Detroit Murals: A History and a Personal Journey

The year 1932 was not a good time to come to Detroit, Michigan. The Great Depression cast dark clouds over the city. Scores of factories had ground to a halt, hungry people stood in breadlines, and unemployed autoworkers were selling apples on street corners to survive. In late April that year, against this grim backdrop, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo stepped off a train at the cavernous Michigan Central depot near the heart of the Motor City. They were on their way to the new Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), a symbol of the cultural ascendancy of the city and its turbo-charged prosperity in better times. The next 11 months in Detroit would take them both to dazzling artistic heights and transform them personally in far-reaching, at times traumatic, ways.

I subtitle this article “a history and a personal journey.” The history looks at the social context of Diego and Frida’s defining time in the city and the art they created; the personal journey explores my own relationship to Detroit and the murals Rivera painted there. I was born and raised in the city, listening to the sounds of its bustling streets, coming of age in its diverse neighborhoods, growing up with the driving beat of its music, and living in the shadows of its factories. Detroit was a labor town with a culture of social justice and civil rights, which on occasion clashed with sharp racism and powerful corporations that defined the age. In my early twenties, I served a four-year apprenticeship to become a machine repair machinist in a sprawling multistory General Motors auto factory at Clark Street and Michigan Avenue that machined mammoth seven-liter V8 engines, stamped auto body parts on giant presses, and assembled gleaming Cadillacs on fast-moving assembly lines. At the time, the plant employed some 10,000 workers who reflected the racial and ethnic diversity of the city, as well as its tensions. The factory was located about a 20-minute walk from where Diego and Frida got off the train decades earlier but was a world away from the downtown skyscrapers and the city’s cultural center.

I grew up with Rivera’s murals, and they have run through every stage of my life. I’ve been gone from the city for many years now, but an important part of both Detroit and the murals have remained with me, and I suspect they always will. I return to Detroit frequently, and no matter how busy the trip, I have almost always found time for the murals.

In Detroit, Rivera looked outwards, seeking to capture the soul of the city, the intense dynamism of the auto industry, and the dignity of the workers who made it run. He would later say that these murals were his finest work. In contrast, Kahlo looked inward, developing a haunting new artistic direction. The small paintings and drawings she created in Detroit pull the viewer into a strange and provocative universe. She denied being a Surrealist, but when André Breton, a founder of the movement, met her in Mexico, he compared her work to a “ribbon around a bomb” that detonated unparalleled artistic freedom (Hellman & Ross, 1938).

Rivera, at the height of his fame, embraced Detroit and was exhilarated by the rhythms and power of its factories (I must admit these many years later I can relate to that response). He was fascinated by workers toiling on assembly lines and coal-fired blast furnaces pouring molten metal around the clock. He felt this industrial base had the potential to create material abundance and lay the foundation for a better world. Sixty percent of the world’s automobiles were built in Michigan at that time, and Detroit also boasted other state-of-the-art industry, from the world’s largest stove and furnace factory to the main research laboratories for a global pharmaceutical company.

“Detroit has many uncommon aspects,” a Michigan guidebook produced by the Federal Writers Project pointed out, “the staring rows of ghostly blue factory windows at night; the tired faces of auto workers lighted up by simultaneous flares of match light at the end of the evening shift; and the long, double-decker trucks carrying auto bodies and chassis” (WPA, 1941:234). This project produced guidebooks for every state in the nation and was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal Agency that sought to create jobs for the unemployed, including writers and artists. I suspect Rivera would have embraced the approach, perhaps even painted it, had it then existed.

Detroit was a rough-hewn town that lacked the glitter and sophistication of New York or the charm of San Francisco, yet Rivera was inspired by what he saw. In his “Detroit Industry” murals on the soaring inner walls of a large courtyard in the center of the DIA, Rivera portrayed the iconic Ford Rouge plant, the world’s largest and most advanced factory at the time. “[These] frescoes are probably as close as this country gets to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” New York Times art critic Roberta Smith wrote eight decades later (Smith, 2015).

The city did not speak to Kahlo in the same way. She tolerated Detroit — sometimes barely, other times with more enthusiasm — rather than embracing it. Kahlo was largely unknown when she came to Detroit and felt somewhat isolated and disconnected there. She painted and drew, explored the city’s streets, and watched films — she liked Chaplin’s comedies in particular — in the movie theaters near the center of the city, but she admitted “the industrial part of Detroit is really the most interesting side” (Coronel, 2015:138).

During a personally traumatic year — she had a miscarriage that went seriously awry in Detroit, and her mother died in Mexico City — she looked deeply into herself and painted searing, introspective works on small canvases. In Detroit, she emerged as the Frida Kahlo who is recognized and revered throughout the world today. While Vogue still identified her as “Madame Diego Rivera” during her first New York exhibition in 1938, the New York Times commented that “no woman in art history commands her popular acclaim” in a 2019 article (Hellman & Ross, 1938; Farago, 2019).

My emphasis will be on Rivera and the “Detroit Industry” murals, but Kahlo’s own work, unheralded at the time, has profoundly resonated with new audiences since. While in Detroit, they both inspired, supported, influenced, and needed each other.

Prelude

Diego and Frida married in Mexico on August 21, 1929. He was 43, and she was 22 — although their maturity, in her view, was inverse to their age. Their love was passionate and tumultuous from the beginning. “I suffered two accidents in my life,” she later wrote, “one in which a streetcar knocked me down … the other accident is Diego” (Rosenthal, 2015:96).

They shared a passion for Mexico, particularly the country’s indigenous roots, and a deep commitment to politics, looking to the ideals of communism in a turbulent and increasingly dangerous world (Rosenthal, 2015:19). Rivera painted a major set of murals — 235 panels — in the Ministry of Education in Mexico City between 1923 and 1928. When he signed each panel, he included a small red hammer and sickle to underscore his political allegiance. Among the later panels was “In the Arsenal,” which included images of Frida Kahlo handing out weapons, muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros in a hat with a red star, and Italian photographer Tina Modotti holding a bandolier.

The politics of Rivera and Kahlo ran deep but didn’t exactly follow a straight line. Kahlo herself remarked that Rivera “never worried about embracing contradictions” (Rosenthal, 2015:55). In fact, he seemed to embody F. Scott Fitzgerald’s notion that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function” (Fitzgerald, 1936).

Their art, however, ultimately defined who they were and usually came out on top when in conflict with their politics. When the Mexican Communist Party was sharply at odds with the Mexican government in the late 1920s, Rivera, then a Party member, nonetheless accepted a major government commission to paint murals in public buildings. The Party promptly expelled him for this act, among other transgressions (Rosenthal, 2015:32).

Diego and Frida came to San Francisco in November 1930 after Rivera received a commission to paint a mural in what was then the San Francisco Stock Exchange. He had already spent more than a decade in Europe and another nine months in the Soviet Union in 1927. In contrast, this was Kahlo’s first trip outside Mexico. The physical setting in San Francisco, then as now, was stunning — steep hills at the end of a peninsula between the Pacific and the Bay — and they were intrigued and elated just to be there. The city had a bohemian spirit and a working-class grit. Artists and writers could mingle with longshoremen in bars and cafes as ships from around the world unloaded at the bustling piers. At the time, California was in the midst of an “enormous vogue of things Mexican,” and the couple was at the center of this mania (Rosenthal, 2015:32). They were much in demand at seemingly endless “parties, dinners, and receptions” during their seven-month stay (Rosenthal, 2015:36). A contradiction with their political views? Not really. Rivera felt he was infiltrating the heart of capitalism with more radical ideas.

Rivera’s commission produced a fresco on the walls of the Pacific Stock Exchange, “Allegory of California” (1931), a paean to the economic dynamism of the state despite the dark economic clouds already descending. Rivera would then paint several additional commissions in San Francisco before leaving. While compelling, these murals lacked the power and political edge of his earlier work in Mexico or the extraordinary genius of what was to come in Detroit.

While in San Francisco, Rivera and Kahlo met Helen Wills Moody, a 27-year-old world-class tennis player, who became the central model for the Allegory mural. She moved in rarified social and artistic circles, and as 1930 drew to a close, she introduced the couple to Wilhelm Valentiner, the visionary director of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), who had rushed to San Francisco to meet Rivera when he learned of the artist’s arrival.

Valentiner was “a German scholar, a Rembrandt specialist, and a man with extraordinarily wide tastes,” according to Graham W.J. Beal, who himself revitalized the DIA as director in the 21st century. “Between 1920 and the early 1930s, with the help of Detroit’s personal wealth and city money, Valentiner transformed the DIA … into one of the half-dozen top art collections in the country,” a position the museum continues to hold today (Beal, 2010:34). The museum director and the artist shared an unusual kinship. “The revolutions in Germany and Mexico [had] radicalized [both],” wrote Linda Downs, a noted curator at the DIA (Downs, 2015:177). Little more than a decade later, “the idea of the mural commission reinvigorated them to create a highly charged monumental modern work that has contributed greatly to the identity of Detroit” (Downs, 2015:177).

When Valentiner and Rivera met, the economic fallout of the Depression was hammering both Detroit and its municipally funded art institute. The city was teetering at the edge of bankruptcy in 1932 and had slashed its contribution to the museum from $170,000 to $40,000, with another cut on the horizon. Despite this dismal economic terrain, Valentiner was able to arrange a commission for Rivera to paint two large-format frescoes in the Garden Court at the new museum building, which had opened in 1927. Edsel Ford, the son of Henry Ford and a major patron of the DIA, pledged $10,000 for the project — a truly princely sum at that moment — and would double his contribution as Rivera’s vision and the scale of the project expanded (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Edsel also played an unheralded role in support of the museum through the economic traumas to come.

A discussion of Rivera’s mural commission gets a bit ahead of our story, so let’s first look at Detroit’s explosive economic growth in the early years of the 20th century. This industrial transformation would provide the subject and the inspiration for Rivera’s frescoes.

The Motor City and the Great Depression

At the turn of the 20th century, Detroit “was a quiet, tree-shaded city, unobtrusively going about its business of brewing beer and making carriages and stoves” (WPA, 1941:231). Approaching 300,000 residents, Detroit was the 13th-largest city in the country (Martelle, 2012:71). A future of steady growth and easy prosperity seemed to beckon.

Instead, Henry Ford soon upended not only the city, but much of the world. He was hardly alone as an auto magnate in the area: Durant, Olds, the Fisher Brothers, and the Dodge Brothers, among others, were also in or around Detroit. Ford, however, would go beyond simply building a successful car company: he unleashed explosive growth in the auto industry, put the world on wheels, and became a global folk hero to many, yet some were more critical. The historian Joshua Freeman points out that “Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) depicts a dystopia of Fordism, a portrait of life A.F. — the years “Anno Ford,” measured from 1908, when the Model T was introduced — with Henry Ford the deity” (Freeman, 2018:147).

Ford combined three simple ideas and pursued them with razor-sharp, at times ruthless, intensity: the Model T, an affordable car for the masses; a moving assembly line that would jump-start productivity growth; and the $5 day for workers, double the prevailing wage in the industry. This combination of mass production and mass consumption — Fordism — allowed workers to buy the products they produced and laid the basis for a new manufacturing era. The automobile age was born.

The $5 day wasn’t altruism for Ford. The unrelenting pace and control of the assembly line was intense — often unbearable — even for workers who had grown up with back-breaking work: tilling the farm, mining coal, or tending machines in a factory. Annual turnover approached 400 percent at Ford’s Highland Park plant, and daily absenteeism was high. In response, Ford introduced the unprecedented new wage on January 12, 1914 (Martelle, 2012:74).

The press and his competitors denounced Ford — claiming this reckless move would bankrupt the industry — but the day the new rate began, 10,000 men arrived at the plant in the winter darkness before dawn. Despite the bitter cold, Ford security men aimed fire hoses to disperse the crowd. Covered in freezing water, the men nonetheless surged forward hoping to grasp an elusive better future for themselves and their families.

Here is where I enter the picture, so to speak. One of the relatively few who did get a job that chaotic day was Philip Chapman. He was a recent immigrant from Russia who had married a seamstress from Poland named Sophie, a spirited, beautiful young woman. They had met in the United States. He wound up working at Ford for 33 years — 22 of them at the Rouge plant — on the line and on machines. They were my grandparents.

By 1929, Detroit was the industrial capital of the world. It had jumped its place in line, becoming the fourth-largest city in the United States — trailing only New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia — with 1.6 million people (Martelle, 2012:71). “Detroit needed young men and the young men came,” the WPA Michigan guidebook writers pointed out, and they emphasized the kaleidoscopic diversity of those who arrived: “More Poles than in the European city of Poznan, more Ukrainians than in the third city of the Ukraine, 75,000 Jews, 120,000 Negroes, 126,000 Germans, more Bulgarians, [Yugoslavians], and Maltese than anywhere else in the United States, and substantial numbers of Italians, Greeks, Russians, Hungarians, Syrians, English, Scotch, Irish, Chinese, and Mexicans” (WPA, 1941:231). Detroit was third nationally in terms of the foreign-born, and the African American population had soared from 6,000 in 1910 to 120,000 in 1930 (WPA, 1941:108), part of a journey that would ultimately involve more than six million people moving from the segregated, more rural South to the industrial cities of the North (Trotter, 2019:78).

DIA planners projected that Detroit would become the second-largest U.S. city by 1935 and that it could surpass New York by the early 1950s. “Detroit grew as mining towns grow — fast, impulsive, and indifferent to the superficial niceties of life,” the Michigan Guidebook writers concluded (WPA, 1941:231).

The highway ahead seemed endless and bright. The city throbbed with industrial production, the streetcars and buses were filled with workers going to and from work at all hours, and the noise of stamping presses and forges could be heard through open windows in the hot summers. Cafes served dinner at 11 p.m. for workers getting off the afternoon shift and breakfast at 5 a.m. for those arriving for the day shift. Despite prohibition, you could get a drink just about any time. After all, only a river separated Detroit from Canada, where liquor was still legal.

Rivera’s biographer and friend Bertram Wolfe wrote of “the tempo, the streets, the noise, the movement, the labor, the dynamism, throbbing, crashing life of modern America” (Wolfe, as cited in Rosenthal, 2015:65). The writers of the Michigan guidebook had a more down-to-earth view: “‘Doing the night spots’ consists mainly of making the rounds of beer gardens, burlesque shows, and all-night movie houses,” which tended to show rotating triple bills (WPA, 1941:232).

Henry Ford began constructing the colossal Rouge complex in 1917, which would employ more than 100,000 workers and spread over 1,000 acres by 1929. “It was, simply, the largest and most complicated factory ever built, an extraordinary testament to ingenuity, engineering, and human labor,” Joshua Freeman observed (Freeman, 2018:144). The historian Lindy Biggs accurately described the complex as “more like an industrial city than a factory” (Biggs, as cited in Freeman, 2018:144).

The Rouge was a marvel of vertical integration, making much of the car on site. Giant Ford-owned freighters would transport iron ore and limestone from Minnesota and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula down through the Great Lakes, along the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers, and then across the Rouge River to the docks of the plant. Seemingly endless trains would bring coal from West Virginia and Ohio to the plant. Coke ovens, blast furnaces, and open hearths produced iron and steel; rolling mills converted the steel ingots into long, thin sheets for body parts; foundries molded iron into engine blocks that were then precision machined; enormous stamping presses formed sheets of steel into fenders, hoods, and doors; and thousands of other parts were machined, extruded, forged, and assembled. Finished cars drove off the assembly line a little more than a day after the raw materials had arrived at the docks.

In 1928, Vanity Fair heralded the Rouge as “the most significant public monument in America, throwing its shadow across the land probably more widely and more intimately than the United States Senate, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Statue of Liberty.... In a landscape where size, quantity, and speed are the cardinal virtues, it is natural that the largest factory turning out the most cars in the least time should come to have the quality of America’s Mecca, toward which the pious journey for prayer” (Jacob, as cited in Lichtenstein, 1995:13). My grandfather, I suspect, had a more prosaic goal: he needed a job, and Ford paid well.

Despite tough conditions in the plant, workers were proud to work at “Ford’s,” as people in Detroit tended to refer to the company. They wore their Ford badge on their shirts in the streetcars on the way to work or on their suits in church on Sundays. It meant something to have a job there. Once through the factory gate, however, the work was intense and often dangerous and unhealthy. Ford himself described repetitive factory work as “a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind,” yet he was firmly convinced strict control and tough discipline over the average worker was necessary to get anything done (Ford, as cited in Martelle, 2012:73). He combined the regimentation of the assembly line with increasingly autocratic management, strictly and often harshly enforced. You couldn’t talk on the line in Ford plants — you were paid to work, not talk — so men developed the “Ford whisper” holding their heads down and barely moving their lips. The Rouge employed 1,500 Ford “Service Men,” many of them ex-convicts and thugs, to enforce discipline and police the plant.

At a time when economic progress seemed as if it would go on forever, the U.S. stock market drove over a cliff in October 1929, and paralysis soon spread throughout the economy. Few places were as shaken as Detroit. In 1929, 5.5 million vehicles were produced, but just 1.4 million rolled off Detroit’s assembly lines three years later in 1932 (Martelle, 2012:114). The Michigan jobless rate hit 40 percent that year, and one out of three Detroit families lacked any financial support (Lichtenstein, 1995). Ford laid off tens of thousands of workers at the Rouge. No one knew how deep the downturn might go or how long it would last. What increasingly desperate people did know is that they had to feed their family that night, but they no longer knew how.

On March 7, 1932 — a bone-chilling day with a lacerating wind — 3,000 desperate, unemployed autoworkers met near the Rouge plant to march peaceably to the Ford Employment Office. Detroit police escorted the marchers to the Dearborn city line, where they were confronted by Dearborn Police and armed Ford Service Men. When the marchers refused to disperse, the Dearborn police fired tear gas, and some demonstrators responded with rocks and frozen mud. The marchers were then soaked with water from fire hoses and shot with bullets. Five workers were killed, 19 wounded by gunfire, and dozens more injured. Communists had organized the march, but a Michigan historical marker makes the following observation: “Newspapers alleged the marchers were communists, but they were in fact people of all political, racial, and ethnic backgrounds.” That marker now hangs outside the United Auto Workers Local 600 union hall, which represents workers today at the Rouge plant.

Five days later, on March 12, thousands of people marched in downtown Detroit to commemorate the demonstrators who had been killed. Although Rivera was still in New York, he was aware of the Ford Hunger March before it took place and told Clifford Wight, his assistant, that he was eager “not [to] miss…[it] on any account” (Rosenthal, 2015:51). Both he and Kahlo had marched with workers in Mexico and embraced their causes. Rivera had captured their lives as well as their protests in his murals in Mexico.

As it turned out, they missed both the march and the commemoration. Instead, the following month Kahlo and Rivera’s train pulled into the Michigan Central Depot, where Wilhelm Valentiner met them. They were taken to the Ford-owned Wardell Hotel next to the Detroit Institute of Arts. The DIA was the anchor of a grass-lined and tree-shaded cultural center several miles north of downtown. The Ford Highland Park Plant, where the automobile age began with the Model T and the moving assembly line, was four miles further north on the same street. Less than a mile northwest was the massive 15-story General Motors Building, the largest office building in the United States when it was completed in 1922, designed by the noted industrial architect Albert Khan, who also created the Rouge. Huge auto production complexes such as Dodge Main or Cadillac Motor — where I would serve my apprenticeship decades later — were not far away.

Valentiner had written Rivera stating, “The Arts Commission would be pleased if you could find something out of the history of Detroit, or some motif suggesting the development of industry in this town. But in the end, they decided to leave it entirely to you” (Beal, 2010:35). Beal points out “that what Valentiner had in mind at the time may have been something like the Helen Moody Wills paintings, something that had an allegorical slant to it. They were to get something completely different” (Beal, 2010:35). Edsel Ford emphasized he wanted Rivera to look at other industries in Detroit, such as pharmaceuticals, and provided a car and driver for Rivera and Kahlo to see the plants and the city.

But when Rivera visited the Rouge plant, he was mesmerized. He saw the future here, despite the fact that the plant had been hard hit by the Depression: the complex had been shuttered for the last six months of 1931, and thousands of workers had been let go before he arrived (Rosenthal, 2015:67). His fascination with machinery, his respect for workers, and his politics fused in an extraordinary artistic vision, which he filled with breathtaking technical detail. He had found his muse.

Rivera took on the seemingly impossible task of capturing the sprawling Rouge plant in frescoes. The initial commission of two large-format frescoes rapidly expanded to 27 frescoes of various sizes filling the entire room from floor to ceiling. Rivera spent the next two months at the manufacturing complex drawing, pacing, photographing, viewing, and translating these images into large drawings — “cartoons” — as the plans for the frescoes. He demonstrated an exceptional ability to retain in his head — and, I suspect, in his dreams — what he would paint.

Rivera’s Vast Masterpieces

Rivera’s “Detroit Industry” murals are anchored in a specific time and place — a sprawling iconic factory, the Depression decade, and the Motor City — yet they achieve the universal in a way that transcends their origins. Rivera painted workers toiling on assembly lines amid blast furnaces pouring molten iron into cupolas, and through the alchemy of his genius, the art still powerfully — even urgently — speaks to us today. The murals celebrate the contribution of workers, the power of industry, and the promise and peril of science and technology. Rivera weaves together Aztec myths, indigenous world views, Mexican culture, and U.S. industry in a visual tour-de-force that delights, challenges, and provokes. The art is both accessible and profound. You can enjoy it for an afternoon or intensely study it for a lifetime with a sense of constant discovery.

Roberta Smith points out that the murals “form an unusually explicit, site-specific expression of the reciprocal bond between an art museum and its urban setting” (Smith, 2015). Over time, the frescoes have emerged as a visible and vital part of the city, becoming part of Detroit’s DNA. Rivera’s art has been both witness to and, more recently, a participant in history. When he began the project in late spring 1932, Detroit was tottering at the edge of insolvency, and 80 years later, the murals witnessed the city skidding into the largest municipal bankruptcy in history in 2013. A deep appreciation for the murals and their close identification with the spirit and hope of Detroit may have contributed to saving the museum this second time around.

I still vividly remember my own reaction when I first saw the murals. As a young boy, the Rouge, the auto industry, and Detroit seemed to course through our lives. My grandfather Philip Chapman, who was hired at Ford’s Highland Park plant in 1914, wound up spending most of his working life on the line at the Rouge. As a young boy, I watched my grandmother Sophie pack his lunch and fill his thermos with hot coffee before dawn as he hurried to catch the first of three buses that would take him to the plant. When my father, Max, came to Detroit three decades later in the mid-1940s to marry my mother, Rose — they had met on a subway while she was visiting New York City, where he lived — he worked on the line at a Chrysler plant on Jefferson Avenue.

One weekend, when I was 10 or 11 years old, my father took me to see the murals. He drove our 1950 Ford down Woodward Avenue, a broad avenue that bisected the city from the Detroit River to its northern border at Eight Mile Road. Woodward seemed like the main street of the world at the time; large department stores — Hudson’s was second only to Macy’s in size and splendor — restaurants, movie theaters, and office buildings lined both sides of the street north from the river. Detroit had the highest per capita income in the country, a palpable economic power seen in the scale of the factories and the seemingly endless numbers of trucks rumbling across the city to transport parts between factories and finished vehicles to dealers.

We walked up terraced white steps to the main entrance of the Detroit Institute of Arts, an imposing Beaux-Arts building constructed with Vermont marble in what had become the city’s cultural center. As we entered the building, the sounds of the city disappeared. We strolled the gleaming marble floors of the Great Hall, a long gallery topped far above by a beautiful curved ceiling with light flowing through large windows. Imposing suits of medieval armor stood guard in glass cases on either side of us as we crossed the Hall, passed under an arch, and entered a majestic courtyard.

We found ourselves in what is now called the Rivera Court, surrounded on all sides by the “Detroit Industry” murals. The impact was startling. We weren’t simply observing the frescoes, we were enveloped by them. It was a moment of wonder as we looked around at what Rivera had created. Linda Downs captured the feeling: “Rivera Court has become the sanctuary of the Detroit Institute of Arts, a ‘sacred’ place dedicated to images of workers and technology” (Downs, 1999:65). I couldn’t have articulated this sentiment then, but I certainly felt it.

The size, scale, form, pulsing activity, and brilliant color of the paintings deeply impressed me. I saw for the first time where my grandfather went every morning before dawn and why he looked so drawn every night when he came home just before dinner. Many years later, I began to appreciate the art in a much deeper way, but the thrill of walking into the Rivera Court on that first visit has never left. I came to realize that an indelible dimension of great art is a sense of constant discovery and rediscovery. The murals captured the spirit of Detroit then and provide relevance and insight for the times we live in today.

Beal points out that Rivera “worked in a heroic, realist style that was easily graspable” (Beal, 2010:35). A casual viewer, whether a schoolboy or an autoworker from Detroit or a tourist from France, can enjoy the art, yet there is no limit to engaging the frescoes on many deeper levels. In contrast, “throughout Western history, visual art has often been the domain of the educated or moneyed elite,” Jillian Steinhauer wrote in the New York Times. “Even when artists like Gustave Courbet broke new ground by depicting working-class people, the art itself still wasn’t meant for them” (Steinhauer, 2019). Rivera upended this paradigm and sought to paint public art for workers as well as elites on the walls of public buildings. By putting these murals at the center of a great museum in the 1930s through the efforts of Wilhelm Valentiner and Edsel Ford — and more recently, under Graham Beal and the current director Salvador Salort-Pons — the Detroit Institute of Arts opened itself and the murals to new Detroit populations. Detroit is now 80-percent African American, the metropolitan area has the highest number of Arab Americans in the United States, and the Latino population is much larger than when Rivera painted, yet the murals retain their allure and meaning for new generations.

Upon entering the Rivera Court, the viewer confronts two monumental murals facing each other on the north and south walls. The murals not only define the courtyard, they draw you into the engine and assembly lines deep inside the Rouge. The factory explodes with cacophonous activity. The production process is a throbbing, interconnected set of industrial activities. Intense heat, giant machines, flaming metal, light, darkness, and constant movement all converge. Undulating steel rail conveyors carry parts overhead. There were 120 miles of conveyors in the Rouge at the time; they linked all aspects of production and provide a thematic unity to the mural. And even though he’s portraying a production process in Detroit, Rivera’s deep appreciation of Mexican culture and heritage infuses the frescoes. An Aztec cosmology of the underworld and the heavens runs in long panels spanning the top of the main murals and similar imagery appears throughout the frescoes.

On the north wall, a tightly packed engine assembly line, with workers laboring on both sides, is flanked by two huge machine tools — 20 feet or so high — machining the famed Ford V8 engine blocks. Workers in the foreground strain to move heavy cast-iron engine blocks; muscles bulge, bodies tilt, shoulders pull in disciplined movement. These workers are not anonymous. At the center foreground of the north wall, with his head almost touching a giant spindle machine, is Paul Boatin, an assistant to Rivera who spent his working life at the Rouge. He would go on to become a United Auto Workers (UAW) organizer and union leader. Boatin had been present at the Ford Hunger March on that disastrous day in March 1932 and still choked up talking about it many decades later in an interview in the film The Great Depression (1990).

In the foreground, leaning back and pulling an engine block with a white fedora on his head may have been Antonio Martínez, an immigrant from Mexico and the grandfather of Louis Aguilar. A reporter for the Detroit News, Aguilar describes how fierce, at times ugly, pressures during the Great Depression forced many Mexicans to leave Detroit and return to their homeland. The city’s Mexican population plummeted from 15,000 at the beginning of the 1930s to 2,000 at the end of the decade. If the figure in the mural is not his grandfather, Aguilar writes “let every Latino who had family in Detroit around 1932 and 1933 declare him as their own” (Aguilar, 2018).

A giant blast furnace spewing molten metal reigns above the engine production, which bears a striking resemblance to a Charles Sheeler photo of one of the five Rouge blast furnaces. The flames are so intense, and the men so red, you can almost feel the heat. In fact, the process is truly volcanic and symbolic of the turbulent terrain of Mexico itself. It brings to mind Popocatépetl, the still-active 18,000-foot volcano rising to the skies near Mexico City. To the left, above the engine block line, green-tinted workers labor in a foundry, one of the dirtiest, most unhealthy, most dangerous jobs. Meanwhile, a tour group observes the process. Among them in a black bowler hat is Diego Rivera himself.

On the south wall, workers toil on the final assembly line just before the critical “body drop,” where the body of a Model B Ford is lowered to be bolted quickly to the car frame on a moving assembly line below. Once again, through his perspective Rivera draws you into the line. A huge stamping press to the right forms fenders from sheets of steel like those produced in the Rouge facilities. Unlike most of the other machines Rivera portrays, which are state of the art, this press is an older model, selected because of its stylized resemblance to an ancient sculpture of Coatlicue, the Aztec goddess of life and death (Beale, 2010:41; Downs, 1999:140, 144).

On the left is another larger tour group, which includes a priest and Dick Tracy, a classic cartoon character of the era. The Katzenjammer Kids — more comic icons of the time — are leaning on the wall watching the assembly line move. The eyes of most of the visitors seem closed, as if they were physically present, but not seeing the intense, occasionally brutal, activity before them. Rivera, in effect, is giving us a few winks and a nod with cartoon characters and unobservant tourists.

~

Harley Shaiken · Fall 2019.

1 note

·

View note