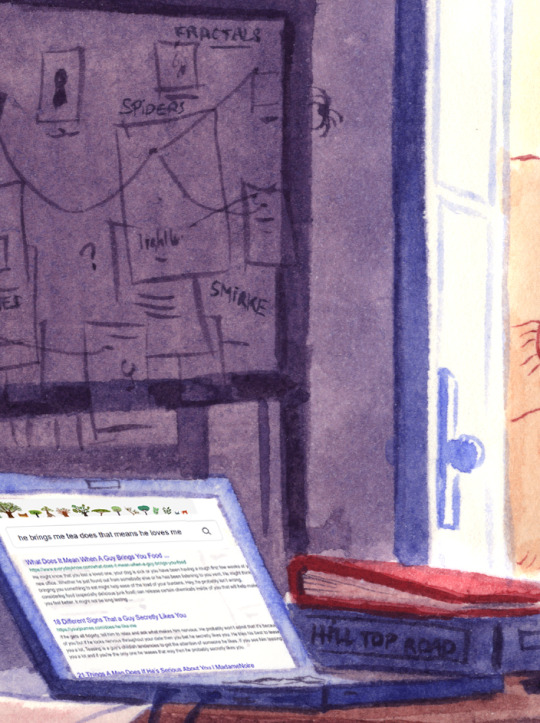

#i hid a bunch of gifts in the details of this illustration

Photo

you guys loved the jon & cats doodles so much I couldn’t stop there

here’s a coloured version

edit: someone said it looks painted and that’s because it is :D it’s watercolour, I’ll add pics of the process under, and on my ig i usually show the process

#:3#no seriously seeing everyone's tags was the end of me i've been smiling at my phone so much#we're all yearning for cats cuddles and kisses huh#and for jonmartin in general#GIVE JON A CAT#cat 4 jon#sharing the love for this podcast gives me so much inspo to do more art#so yeah#i hid a bunch of gifts in the details of this illustration#it was fun#hope you like it#someone said in the tags 'how do you draw so many straight lines without going insane' and yeah#i hate doing background lmao but the archives are worth it#it's a good learning process#especially with how i'm so bad at perceiving depth and drawing spaces like that#and i'm working as a layout artist i don't know how i manage it#anyway#tma#the magnus archives#the magnus archive fanart#jonmartin#jmart#jonandcats#jonathan sims#martin blackwood#the admiral#jon and the admiral#or jon with any cat#the magnus institute#magpod

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Greek Mythology Hades + Persephone Notes

It’s been funny to me, having this story cropping up in FFXIV stuff lately lol. The myth of Hades and Persephone has been a huge part of my life since I was a little girl. My mom used to read different versions of it to me (among other things) in beautifully illustrated treasuries. I remember even then it made a big impression. One of my favorites.

In high school, I tried to retell the story. And I did an absolute BUTTLOAD of research for it. I read not just the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Ovid’s iteration, the more recent accounts in Bullfinches and Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. I listened to Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo and read the libretto. I found Claudian’s version. I went to Hesiod’s Theogony so I would understand where the gods came from before discovering their callings.

At the time I wasn’t ready. As a writer, I wasn’t at the level I needed to be and my trying to be historically authentic wasn’t the right road given what resonated for me personally. I do think I’m about ready now, just need to sort some stuff out.

But I have a few thoughts I’m going to include under a cut. This was a little inspired by another post on my dash, and it started with me being a bigass nerd nitpicking a detail lol. And I was side-eyeing myself all “don’t be that guy, it’s a good post”. And then I just got to thinking about the characters again a bit, and I still have a lot of affection and thoughts, so in the end I decided to just collect the bunch and plop ‘em here.

The nitpick thing comes from The Theogony.

Something that really stunned me when I first realized it--the original six children of the titans Cronos and Rhea had no assigned roles or tasks. They were, effectively, just people. Just gods. No elements, no affiliations.

Hestia, goddess of the hearth and home, a virgin, was the eldest. Not the eldest daughter only--of her, Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus, she was first. Hades was the eldest son. Zeus, of all of them, was youngest while Hera was the youngest daughter only.

For a long time I’ve thought there was something kind of lonely, sad, interesting, and kind about Hestia and Hades. They both kept to themselves for the most part. Both avoided the drama and extreme punishments/squabbles of the other gods.

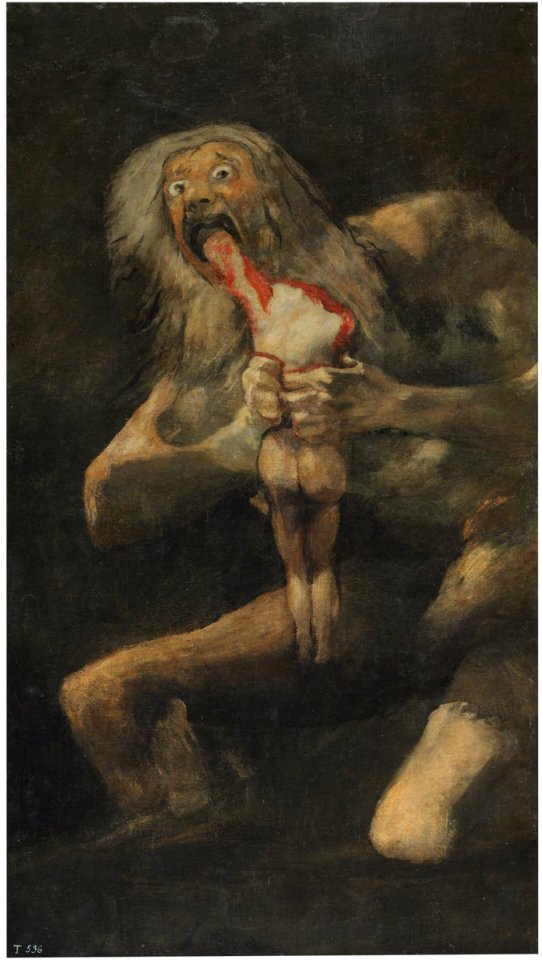

Each of the original six except for Zeus was consumed by their own father.

Being gods, they continued to grow and learn and survived even so. But it’s something I think about, and the idea that every one of them who went through the experience faced it alone is something I think about too.

Zeus was only able to escape because Rhea hid him. I wonder if she’d tried to hide the others only to be thwarted every time. I wonder if she stopped wanting to have children because she knew what would happen to them. There may have been a time she loved her husband, but if I remember correctly she helped her children slay him in the end. I wonder if she grew to truly hate him or if any love that remained was just outweighed by her horror.

Zeus had to be suspended from the trees in a cradle. If he’d been on the ground, the sky, or the sea alone then Cronos would have found and consumed him. His formative years would have been ruled by the fear that with one misstep, he’d be discovered and eaten as well. I think about that sometimes too, given he was so afraid of the prophecy that any offspring with Metis would outstrip the father in power that he literally ate his lover before she could give birth. When Athena was born anyway, bursting from her father’s skull in full armor, I wonder if he realized that he’d become the most horrifying embodiment of his father. I wonder what conversations followed between him and Athena that led to her becoming honored and beloved by him instead of feared. And I find it interesting that for all the love and pride Zeus felt for his goddess of war who outstripped him, he only ever felt scorn for Ares--the god of war and his only son with Hera.

But anyway.

Rescued by Zeus, the original six made alliances with their uncles the Cyclopes, the Hecatoncheires/the Hundred Handed Ones. And from them, the sons each received gifts to help them do war against the titans who would see them destroyed. Zeus received the lightning bolt. Poseidon, the trident. And Hades was gifted a helm of invisibility. Again, at that point none had any kingdoms or callings.

When the Olympians won, the brothers drew lots among themselves. I actually think the order might have been detailed too. Before they made their selections, I wonder if they were more afraid or hopeful. One of them would be the king of all the gods, ruler of the heavens. One of them would be banished from their midst to dwell only with the dead for the rest of his years.

Hades went first. Hades got what was, in many ways, a sentence to isolation. An exile. He’d done nothing to deserve it except be brave and be willing to accept the risk of that office. Maybe there was a reason for that, and only the one willing to risk shouldering that weight could receive it

I think about how Poseidon went next, and when he was given dominion over the seas I remember reading a little about him essentially throwing a tantrum/small war. Because he wanted to rule. I think about how Hades probably watched that furious reaction. I wonder how he felt and if he and Zeus spoke at all before parting.

Hades, before Persephone, experienced fear at the onslaught from Typhon, Gaia’s son born to Tartarus as revenge upon the gods for killing her titan children. He wasn’t the only one. All the other deities became animals and fled. Zeus was caught and mutilated. Those who remained had to band together and save him.

And I think about how, despite all the wars and squabbles, Hades seemed to appreciate the gravity of his position. He honored the dead he watched over. And it was only when, stricken by Eros’ arrow at the power-hungry Aphrodite’s behest, that his loneliness and need overwhelmed him.

He must have been repressing that for a long time.

In Claudian’s version, Persephone is shown falling in love with the King of the Dead. In L’Orfeo, when Orpheus comes to plead for his wife Persephone makes clear that she does in fact love her husband and considers herself fortunate to be beside him. I think about how Persephone was both goddess of spring (birth and rebirth, the renewal of life) and the Iron Queen whose name mortals feared to speak. I wonder if nature, red in tooth and claw was part of how she reconciled these truths in herself. I wonder what the process was like as they came to know each other and if it was difficult. I wonder what point it became clear that Hades didn’t simply need Persephone to be any companionship, any light among the dead--but as herself. As his equal and consort, who could and sometimes did challenge his decisions.

I really like the idea that their process of falling in love--Persephone, having always lived in the shadow of her mother without any opportunity to discover who she was for herself, Hades having sacrificed himself to duty to the point that it drove him mad--required both of them to help each other stand on their feet and reclaim their own identities from the circumstances smothering them. I adore the idea that they came to truly love each other after coming to know and love themselves too.

At some point I really am going to write my take on all of this as a proper story. Probably sometime soon. But it’s been nice to see the different ways pieces of Greek mythology get referenced in FFXIV, and when the specific Hades/Persephone story gets brought up by fans I remember this stuff.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Books, Wefts, and Black Lives Matter at the Baltimore Museum of Art

Kiki Smith, “Tidal” (1998), on view as part of “Off the Shelf: Modern & Contemporary Artists’ Books” (2017), The Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mitro Hood)

Fog enveloped Phan-Xi-Pang, Indochina’s tallest peak, in an ocean of vanilla milkshakes. You could drink the air with a straw.

Touring Vietnam during the past two months, I eagerly anticipated painting and drawing the mountains I found pictured online. Unfortunately, clouds and fog often hid the range like the closed covers of a book, day after frustrating day. Frustrating, that is, until I embraced the mystery of what was there — Robert Ryman on swimmy steroids — rather than longing for what wasn’t.

Shortly before leaving the US, I had a related experience. I was at a press preview for a show called Off the Shelf: Modern & Contemporary Artists’ Books at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where being unable to see all that I wanted to see played first a troubling role, then an enticing one.

Artists’ books tend to be rare and fragile. They need to be protected. Hence the vitrines, which, along with closed covers and fixed, double-page spreads, prohibit a full read. It is, however, a treat to see any part of these inventive objects.

Of course, there are many works of art beset by obstacles that limit our viewing experience. We stand far below that colossal, every-page-visible-at-once picture book known as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. Who wouldn’t like a more optimum look at the narratives muscling their way across a vaulted heaven? Who wouldn’t like to get up close and personal with Adam or Eve, or to bite into an apple from that tree in their garden? We can’t. But we take what we can get.

Compare this to the thwarted desire to leaf through the pages of the publisher Ambroise Vollard’s 1931 edition of The Unknown Masterpiece (Le Chef-d’Oeuvre Inconnu) by Honoré de Balzac, the first book I was drawn to upon entering Off the Shelf. Six of the etchings by Pablo Picasso that accompany this tragic literary classic about art and seeing, which hang directly above the book. The illustrations can be treasured independently, as can the French author’s words. But when a great story and great images merge, it’s magic.

Installation view of “Off the Shelf: Modern & Contemporary Artists’ Books” (2017), The Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mitro Hood)

With one exception (a promised gift), all the works in Off the Shelf are from the BMA’s collection. Rena Hoisington, Senior Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, curated wisely, as well as helped design the individual displays and overall galleries. On monitors in an adjoining room, viewers can scroll through numerous books from the exhibition, allowing for a more start-to-finish eyeballing (albeit virtual) experience. One of my scrolling favorites is Paul Verlaine’s once-banned, sapphic Side by Side (Parallèlement, 1900), sinuously illustrated by Pierre Bonnard. In what is considered by many to be the first modern livre d’artiste (artist’s book), the artist’s rose-sanguine marks echo the look and spirit of Verlaine’s words, which were printed on cream-colored pages in a fluid, Renaissance font designed by Claude Garamond.

Bonnard’s sprawling lithographs sometimes corral and always counter the boxy boundaries of italicized type. Often, it seems as if the women he portrays are being coaxed from, or are dissolving into, the paper’s humid sensuality, nude figures sparely drawn here, detailed there. Like a storm cloud, in a section entitled “Sappho,” a sweeping arc of dark, braiding hair from two embracing women further exhilarates their impassioned moment.

Double-page spread of “Side by Side (Parallelement)” (1900), words by Paul Verlaine, images by Pierre Bonnard

Off the Shelf is an intimate exhibit of small gems. The works spring from inspired painter/writer pairings of showstopper sensibilities, including Grace Hartigan/James Schuyler; David Hockney/The Brothers Grimm; Susan Rothenberg/Robert Creeley; and Jasper Johns/Samuel Beckett. With few exceptions, like the over-sized and weighty My Pretty Pony, a steel-covered undertaking by Barbara Kruger and Stephen King, these editions are not what, 30 years ago, my then-three-year old daughter would have referred to as “two-handed books.” But despite their mostly midsize proportions, these images and objects have a king-size impact, partly because creative combos are sharing the more private — but no less profound — sides of themselves. And we get to peek.

“Salute” (1960), Grace Hartigan, prints/James Schuyler, text, The Baltimore Museum of Art: Gift of Floriano Vecchi, New York, in memory of William Richard Miller (© Estate of Grace Hartigan)

Few of the more than 130 artists’ books and related prints in this show are ever seen in public, yet they are decidedly social in nature. Visual artists team up with other visual artists, as well as with poets, novelists, fairytale writers, book designers, typographers, typesetters, and publishers.

Hands down, the biggest social event of Off the Shelf takes the form of 1 Cent Life (1964), a celebration of art and poetry that brought together the disparate styles of abstraction and Pop. Walasse Ting and Sam Francis invited 28 blue-chip artists, ranging from Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol, to James Rosenquist, Joan Mitchell, and Tom Wesselmann. The boisterous affair included 172 pages filled with 62 lithographs and 62 poems (written by Ting).

Installation view of “Off the Shelf: Modern & Contemporary Artists’ Books” (2017), The Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mitro Hood)

In this exhibition, pages turn, hang, separate, and fold. When unfolded, the accordion books, Tidal (1998), by Kiki Smith, and Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), reveal elegant, elongated proportions with sleek, unique formats.

With computer screens replacing paper pages, a show like Off the Shelf is timelier than it would have been less than a decade ago. It remains to be seen whether tactile books become less important due to their cost and the diminishment of their practical necessity, or more important through their physicality and personality. Big money is on the former. I hope it’s the latter.

* * *

Louise Wheatley at her loom in her studio, Harford County, MD, 2016 (photo by Anita Jones)

Another show currently at the Baltimore Museum of Art is Timeless Weft: Ancient Tapestries and the Art of Louise B. Wheatley. Anita Jones, the museum’s Curator of Textiles, installed weavings from Wheatley’s more than 40-year career alongside a series of ancient Egyptian Coptic fabric works. The historical conversation that unfolds between the contemporary weaver’s works and the time-old textiles enriches them both.

Content, color, texture, and technique represent visible connections between the two bodies of work. And then there are invisible links that become an evocation of time. The Coptic weavings have missing — invisible — parts, which have been lost over the centuries. I’ve always been a sucker for fragments, where the harsh blade and the delicate patina of centuries reconfigure shapes and dimensions, add subtlety to surface, and glaze the beauty of age across pristine colors. Fragments lead to fantasy. What could have been depicted in the no-longer-visible parts surrounding the stylized hares racing through several borders of an Egyptian 10th-11th-century silk and linen textile? The fragment adorns a wall not much more than a vitrine away from its contemporary counterpart, Wheatley’s “Rabbit” (2014). From threads to shreds and back again, in my imagination I complete the story.

Louise Wheatley, “Rabbit” (c. 2014), linen, wool, cotton, silk (courtesy the Artist and The Baltimore Museum of Art)

Although some of Wheatley’s finely crafted weavings are large, many are about the length of a long finger. But even the artist’s tiniest textiles deliver with the might of a fog that can erase a mountain, as we see in both her portrayal of a gangly insect, “Walking Stick” (c. 1995), and a biblical hero, “David” (c. 1991), as he kneels (in one panel of a pocket-size triptych) to look for the stone with which he will defeat Goliath.

One of the larger wall hangings, “Fruits of the Spirit” (c. 1991), struck me initially as being dominated by three vertical strips of flat black. The central strip backs a charming, light-toned portrait of a pear tree that grows on the artist’s farm in Maryland. Turns out, the dark strips aren’t black at all, or flat, for that matter, but rather — as a close inspection reveals — a blend of deep tones, textures, and colors.

This tapestry does with shade what another of her works, “Egg Collection” (2005) does with shine. Here, variations in the figure/ground relationships, the finely spun warm and cool off-white ovals, and the quivering grid containing the now-you-see-them-now-you-don’t eggs create a slow, playful bounce to this fragile yet solid work. It’s as if the artist took a bunch of eggs, shook them up, and not only did not a one of ‘em crack, they all seem to revel in the delicacy of the dance of their white-on-white invisibility.

Louise Wheatley, “Egg Collection” (2005), linen, wool, cotton, silk (courtesy the Artist and the Baltimore Museum of Art)

Wheatley’s range of subjects is impressive. With heft and weft, she is equally expressive — formally, psychologically, and spiritually — at addressing pear trees and eggs, darkness and light, bugs and the bible.

* * *

Adam Pendleton, “A Victim of American Democracy IV” (wall work), (2016), adhesive vinyl, installation at The Baltimore Museum of Art (photo by Mitro Hood. ©️ Adam Pendleton, courtesy Pace Gallery)

For merging words and images, these are red-letter days on Baltimore’s Art Museum Drive. In a third show at the BMA, Front Room: Adam Pendleton, the words are the images. In Pendleton’s case, his ABCs are white, gray, and black — not red — sometimes spanning the walls from floor to ceiling.

Several works feature variations of the rallying cry “Black Lives Matter,” which has a trenchant meaning in Baltimore after the death of Freddie Grey. Gestural, sprayed, dripped, printed, broken, cropped, layered, rotated, and wiped-away, the letters simultaneously weave information, emotion, frustration, and hope into a powerful humanistic, social, and political message.

Adam Pendleton, “what is . . . (study)” (2017), silkscreen ink on Mylar (courtesy the Artist and Pace Gallery)

Like the BMA’s books, Wheatley’s textiles and Pendelton’s mixed-media ventures pack a punch (actually, hers is more of a lingering touch). With her, you don’t see it coming; with him, you can feel the vibrations down the block. Her mists/his missiles, resounding, both.

Off the Shelf: Modern & Contemporary Artists’ Books continues through June 25; Timeless Weft: Ancient Tapestries and the Art of Louise B. Wheatley continues through July 30; and Front Room: Adam Pendleton continues through October 1.

All three exhibitions are located at the Baltimore Museum of Art (10 Art Museum Drive, Baltimore, Maryland).

The post Books, Wefts, and Black Lives Matter at the Baltimore Museum of Art appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2rIMbMw

via IFTTT

0 notes