#reject heroism return to villainy

Note

Haiii 😳😳... I believe, Aquarius would slay in 🔔 the Port Fest outfit...

Also thank you for doing my ask...

tell him he's handsome NOW !!!!!!!

(twst oc outfit asks)

#twst#twst oc#rsa oc#gawzdrawz#request#thank YOU for making the lil ask thing !!!! its v v fun :3#this is reminding me#my two rsa students are both like. nrc by proxy lmao#WAIT ALL THREE OF THEM#BC DARLING CHANGED SCHOOLS#reject heroism return to villainy#(almost typed heroin oops)#twst: aquarius bey

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

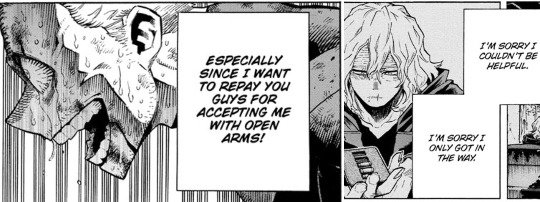

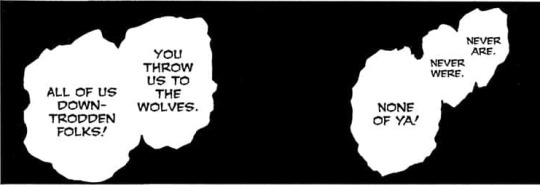

To talk about Twice and villainy is to talk about class and criminality (IV)

(Masterlist)

cw: references the dehumanization of “terrorists,” like, irl

The trash of society

“Disposability” is a framework that interrogates the way human lives are valued. Arising from observations about material disposability in the rapid industrialization of post-’45 and the increasing hold of mass-production and consumerism, “disposability” eventually expanded to an investigation of the human cost of this modern landscape. Theorists raised the question of how the disposability of human lives could be understood in tandem with the disposability of material goods, linking together issues of class, poverty, migration, imperialism, race, production, and consumerism. In essence, disposability as a framework investigates how human lives come to be rendered as disposable—and thus, like waste, byproducts of a lifestyle of endless growth.

This concern is one that receives frequent exploration in fiction that delves into the framework of humans-as-waste; for example, the sci fi dystopian short story Folding Beijing follows a waste worker in his efforts to fund the education of his adoptive daughter, who he found abandoned outside his waste-processing station. Although the conditions in BNHA aren’t nearly as grim, there are nevertheless clear connections drawn between its villainous characters and the concept of humans-as-waste, to the point where villains refer to themselves or are referred to by others as “trash.” Quirks may have effected a massive social upheaval, but that didn’t do away with, only shifted, the specifics of the idea that there are people who are deserving and people who are not, innocent people and criminals.

Throughout the series, we see characters mistreated while a society of deserving innocents looks on. There was little concern from the public when Izuku was mocked and bullied for his Quirklessness, when Rei was sold into a marriage for the benefit of a wealthy and abusive pro hero, when five-year-old Tenko wandered the streets alone, and when Jin was left to fend for himself as a teenager. Under the framework of disposability, they might as well have been rendered “waste,” as Zygmunt Bauman writes: “[t]he story we grow in and with has no interest in waste[...],” instead

“[w]e dispose of leftovers in the most radical and effective way: we make them invisible by not looking and unthinkable by not thinking. They worry us only when the routine elementary defences are broken and the precautions fail—when the comfortable, soporific insularity of our Lebenswelt which they were supposed to protect is in danger.” [source]

It is, interestingly, a bigger-picture version of the charges Shigaraki Tomura directs against the world of BNHA: like Bauman says, the innocent civilians are oblivious, recognizing neither the fragility of their peace nor the artificiality of it as it is maintained by heroes, unwilling to acknowledge the "leftovers”—the people who weren’t saved—until they return as villains and that very peace is threatened.

As for the leftovers themselves, they feel their alienation acutely. According to Bauman, to be “redundant” in a productivity-driven economy is to “share semantic space with ‘rejects’, wastrels’, ‘garbage’, ‘refuse’—with waste.” He outlines the conditions of redundancy thusly, describing it as a kind of “social homelessness”:

“To be redundant means[... t]he others do not need you; they can do as well, and better, without you. There is no self-evident reason for your being around and no obvious justification for your claim to the right to stay around. To be redundant means to have been disposed of because of being disposable[...]”

The experience of this kind of disposability is evident in BNHA, as class and exploitation seem to be highly correlated with social isolation. The members of the Shie Hassaikai were used and abandoned, and bonded strongly to one another after joining Overhaul. Jin’s experience of “social homelessness” shows him walking alone through empty city streets, before he ends up talking to his own clone below an overpass. Jin, too, finds companionship in joining a group, the League of Villains, but fears of disposability and further isolation plague his thoughts. Whether or not he genuinely believes League of Villains would abandon him, Jin feels the need to continue justifying his place among them. The societal bleeds into the personal; Jin’s disposability to society, best represented by his interactions with law enforcement and with his employer, also becomes an anxiety in his interpersonal relationships. Horikoshi’s decision to characterize Jin in such a way makes it impossible to ignore the larger issues that created him; namely, class issues that reflect real-world concerns.

As Jin sits below the overpass, talking to his clone, he asks whether he went wrong somewhere. The other Jin responds that it must have been “being born without an ounce of luck.” Bauman comments on unluckiness thusly:

“In Samuel Butler’s Erewhon it was ‘ill luck of any kind, or even ill treatment at the hands of others’ that was ‘considered an offence against society, inasmuch as it [made] people uncomfortable to hear of it.’ ‘Loss of fortune, therefore’ was ‘punished hardly less severely than physical delinquency’.” [source]

These observations are perfectly applicable to the characters we’ve met. It’s often the “unlucky” who get treated the worst: Izuku was bullied relentlessly for his “unlucky” Quirklessness, and Rei wound up trading her “unlucky” marriage for an institutionalization of ten years. Jin was fired from his job after an “unlucky” accident, fell into a life of crime, and is finally killed by the same hero who offered him a second chance. When Dabi probes Tokoyami Fumikage in an attempt to make him contend with Jin’s “ill treatment” at Hawks’ hands, Tokoyami dismisses it and justifies Jin’s execution, undoubtedly because it would be uncomfortable, possibly even world-shattering, to acknowledge Dabi’s charge. The fact that these people have been unlucky, or have even been actively mistreated or failed by others, turns the public’s gaze away in an attempt to escape the discomfort elicited by these embodiments of society’s waste. For the “redundant” to remind society of its human cost—or even to remind the non-redundant of the small gap of bad luck that separates them—they become objects of revulsion, to be forgotten or discarded as quickly as possible. Rendered “invisible” and “unthinkable” as leftovers, they become “ontologically non-existent.” [source]

Some of the anxiety towards the “redundant” is precisely because the framework of “becoming waste” is permeable. This permeability accounts for the possibility of transforming from citizen to disposable human; perhaps, then, when “all it takes is one bad day,” the line which separates citizen from villain is just as permeable. In the framework of hero society, it may be argued that villains are not simply redundant waste, but the trash whose alienation hero society relies on in a highly visible way. "The disposable, the waste as objects and humans, inhabit a place of exclusion from society which provides not only an unrecognized space of reinforcement for society itself, but also the fuel and the labor for maintaining the status quo.” [source] In BNHA’s terms, not only are villains excluded from a deserving, innocent society, they are also the fuel for maintaining it by embodying its opposite—the guilty and undeserving—their exclusion constantly reinforced through the public spectacle of their arrests and the public idolization of heroes. Villains are no longer simply inert leftovers that can be easily ignored, as Bauman described; villains have broken past hero society’s elementary defenses, and threaten the Lebenswelt of deserving innocents. While their visibility transforms villains back into an acknowledgeable existence, the very act of breaching their invisibility renders them a kind of waste that must be permanently disposed of.

A livable life?

Heroes do not kill. This is stated in 251 by the death-seeking Ending, who, despite his best efforts, is spared an unceremonious execution at the hands of a hero, who the readers know is a domestic abuser. The deathless resolution to Ending’s conflict, then, further compounds the horror of chapter 266, when Jin is eliminated with extreme prejudice by Hawks, who admires the aforementioned hero. The irony is shocking and bitter as readers witness the violation of one of heroism’s fundamental tenets, broken no less for the elimination of one of the series’ most sympathetic villains, after Hawks himself concedes that Jin is “a good person.” It may be said that heroes do not have carte blanche to kill, but neither is it an inviolable principle, and of course a no-kill mandate says nothing about the ways villains have been injured or tortured at the hands of heroes. While arguments can be made about the imminent risk of certain occasions, the issue remains that it’s often the most vulnerable people who pay the highest price for maintaining a nebulous definition of societal “safety” (a “safety” which always seemed to exclude certain people), a concept that is primarily defined by the state and the policing class. Furthermore, the willingness of a hero to kill in defense of hero society begs the question: who may be killed without consequence, and under what circumstances?

In her collection of essays addressing responses to terrorism, Precarious Life, Judith Butler writes:

“Certain lives will be highly protected, and the abrogation of their claims to sanctity will be sufficient to mobilize the forces of war. Other lives will not find such fast and furious support and will not even qualify as "grievable."”

The notion of a “safe” society hinges on the protection of those sanctified lives, at the expense of vulnerable lives deemed “disposable” through poverty, homelessness, or criminality. A threat against the deserving innocents or the murder of a hero unites every other hero and every citizen in public mourning, and then in opposition against murderous villains—there is no such mobilization for the suffering of Quirkless kids, abused women, or orphaned, destitute teenagers. The threats against their well-beings are considered part-and-parcel to their world—normal, unavoidable, and indeed not violence at all. Certainly, a murdered villain will not find such unanimous grief nor anger mobilized in the wake his death, not even directed toward changing the isolated, impoverished conditions which made villainy an appealing choice in the first place. Jin’s death is privately witnessed and privately mourned, only by those who comprised his ibasho. It’s through these uneven displays of grief that Butler questions: “what counts as a livable life and a grievable death?”

Butler argues that certain lives are removed from the bounds of “normative” humanity, and thus “grievability.” Violence against vulnerable lives is dismissed or legitimized by the state through their dehumanization: in the world of BNHA, villains are “presented [...] as so many faces of evil” and treated as mere vessels of a killing instinct.

“Are they pure killing machines? If they are pure killing machines, then they are not humans [...]. They are something less than human, and yet somehow they assume a human form. They represent, as it were, an equivocation of the human, which forms the basis for some of the skepticism about the applicability of legal entitlements and protections.”

This kind of dehumanization is, of course, explained through the claim that certain people are “dangerous,” a designation which (as Butler points out) is determined by none other than the state itself.

“A certain level of dangerousness takes a human outside the bounds of law[... T]he state posits what is dangerous, and in so positing it, establishes the conditions for its own preemption and usurpation of the law[...]”

Perhaps, then, if villains are something other-than-human, something so dedicated to violence that they can be stopped only through death, no "sanctity,” and no law, is violated if they are killed.

The ability of the state to designate certain people as “dangerous” is linked to another political strategy: defining the difference between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” violence. Butler explains:

“The use of the term, "terrorism," thus works to delegitimate certain forms of violence committed by non-state-centered political entities at the same time that it sanctions a violent response by established states. [...] In this sense, the framework for conceptualizing global violence is such that "terrorism" becomes the name to describe the violence of the illegitimate, whereas legal war becomes the prerogative of those who can assume international recognition as legitimate states.” [source]

In the world of BNHA, clearly such a discernment exists between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” violence. Although certain readers have been quick to draw the “terrorism” analogy, the series itself tends to differentiate between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” violence not through charges of terrorism, but through the designation of “hero” and “villain.” Legitimate violence is wielded by heroes in defense of the state, in defense of property, and against villains, whereas illegitimate violence is wielded by villains against the state, against property, and against heroes. This difference between “hero” and “villain” is, in actuality, insubstantial as far as the question of morality, as even labeled villains such as Gentle Criminal behave within a palatable frame of ethics, while some career heroes are just as capable as villains of taking and ruining lives; nevertheless, the state has a vested interest in strongly promoting the idea of this divide—of legitimate, heroic violence as moral, justified, and legal, and illegitimate, villainous violence as immoral, unjustified, and unlawful. In this way, the state can engage in “legal war” with very little questioning or dissent from its populace, and it further delegitimizes the violence of its opponents. The violence of heroes is justified, and therefore they have an understandable human rationale; on the contrary, the violence of villains is unjustified, it is attributed to their innate violence, which is incomprehensible and inhuman.

“The fact that these prisoners are seen as pure vessels of violence [...] suggests that they do not become violent for the same kinds of reason that other politicized beings do, that their violence is somehow constitutive, groundless, and infinite, if not innate. If this violence is terrorism rather than violence, it is conceived as an action with no political goal, or cannot be read politically. It emerges, as they say, from fanatics, extremists, who do not espouse a point of view, but rather exist outside of "reason," and do not have a part in the human community.” [source]

No one personifies this better than Tomura himself. He is named the “Symbol of Terror” by AFO, and is undoubtedly viewed as such by the heroes and civilians of BNHA. It has been repeatedly emphasized that to everyone but the League of Villains, Tomura is not so much a human as he is the embodiment of thoughtless destruction. Tomura is referred to as a monster, as someone unshackled to humanity, as an “it,” as something that cannot be reasoned with. This is an idea that Horikoshi himself seems to play into somewhat, because although Tomura voices certain critiques of the hero system, he nevertheless seems to remain rather apolitical in who or what he decides to target. It’s Jin, then, who lends a political voice to the villains by criticizing pro heroes from his very first narrated chapter, but even a clear articulation of his grievances gets him no understanding reaction from the hero in front of whom he raises these charges.

While the fictional heroes may see villains as nothing more than vessels of violence, it can be argued that Horikoshi himself went through an extensive effort to depict the rationale and humanity of the villains. As I’ve stated before, Jin is very clearly connected to the real-world struggles of certain Japanese citizens, making him real and relatable in ways other characters may not be. At the same time, the rationale and humanity that Horikoshi recognizes are things that heroes like Hawks can’t grasp: as someone who idolized a hero as a child, and who was, for better or worse, enveloped by the hero system, he does not question the legitimacy of the hero system. Hawks understands only unluckiness in Jin’s circumstances, and shows little awareness of the fact that Jin was failed by the very society Hawks defends, that his suffering was both enforced by the legal system and by his boss, and ignored by institutions supposedly designed to help. Jin, of course, is not so obtuse—he reiterates his awareness that he is one of those disposable, ungrievable lives that heroes don’t save, and he is ultimately proven right—when Hawks’ offer of rehabilitation is rejected, he instead moves to kill. Jin, and other villains, are so thoroughly dehumanized, likened to killing machines, that it doesn’t occur to any hero that they can possibly be reasoned with.

Could there have been any other conclusion? I don’t believe so—not without a significant shift in thinking from heroes. For many of the villains, there’s very little to gain from rejoining the society that they were ejected from. Bauman writes that, for “disposable” humans:

“Unwelcome, tolerated at best, cast firmly on the receiving side of socially recommended or tolerated action, treated in the best of cases as an object of benevolence, charity and pity (challenged, to rub salt into the wound, as undeserved), but not of brotherly help, charged with indolence and suspected of iniquitous intentions and criminal intentions, [they have] few reasons to treat ‘society’ as a home to which one owes loyalty and concern.”

It should come as no surprise, then, that Jin rejects Hawks’ offer of a “socially tolerated” rehabilitation into the society that both caused and ignored his suffering, which he has no reason to believe wouldn’t outcast him again for another slip-up. Of course, he instead chose the place he was understood, where his mistakes were met with patience, where he wasn’t forced to justify his presence, where his sense of belonging felt stable. The people he called his ibasho were a home, a place he was allowed an ontological existence—the very inverse of that old, disposable life.

Conclusion

Bubaigawara Jin should be read as class commentary. The various obstacles in his story are all too reflective of the systemic issues of real-world Japan, concisely highlighting the shortcomings and common abuses of the alternative care system, the justice system, and the workplace. It’s also highly likely that Horikoshi himself is aware of economic inequalities on some level, which seems to reflect in the obvious and less-obvious ways he addresses class in BNHA. I think this probable intentionality is important, as it can lend itself to our speculation on the series’ messages and themes. Importantly, if Jin’s story is a commentary about the real-world trials of economic marginalization, then surely this also applies to the way he is treated by heroes and by wider society. Beyond simple evaluations of “X did this, which forced Y to respond,” certain narrative choices may be better understood as a pattern of illustrating disposability, of the way this fictional society creates “human waste,” and to relate them to real-world patterns of which lives are considered worth saving.

I somewhat downplayed the real-world inspirations for Bauman and Butler’s texts, because I believe those are true and serious topics about capitalism and war that should be discussed on their own merits, unrelated to a fictional series; however, they also perfectly show how certain beliefs in the real world are transferrable to BNHA’s world. Because these beliefs are transferrable, readers’ reactions to certain narratives in fiction are rooted in certain truths we believe about the real world as well. For example, it would pointless to call the League of Villains “terrorists” as a condemnation, unless someone believes that the charge of “terrorism” in itself tells us anything meaningful about morality. As Butler has explained, and as real life shows (e.g. through the designation of black radical groups like the Black Panthers or antifascist groups as terrorist organizations), the term “terrorism” alone holds no inherent moral implication. Imagining that the label of “terrorist” can meaningfully convey anything about morality, and that "being a terrorist” removes a person from the boundaries of “normative humanity” (and thus due legal process in-universe, and reader sympathy out-of-universe) reflects an ignorance about certain real-world political processes.

Injustice in the world doesn’t only take the form of obvious oppression and violence; manipulation is also involved. There is a vested interest by the ruling class in guiding the ways people think and perceive reality, teaching us what we deserve and don’t deserve, what prices are acceptable and unacceptable to pay for human life. These lessons must be rejected from the outset, leaving rules and definitions open for interpretation. What qualifies as violence? Is violence more than a physical act of harm? Is it violence to isolate “unproductive” members of society? Is it violence to deny them food and shelter? Is it then violence to cage and execute them when they do not non-violently accept their subjugation? What forms of violence are unacceptable and why? Where does violence really begin?

Dismantling oppression can only be achieved by questioning its very foundations and the language used to justify it; fiction, by enveloping us into a new reality—a new world with new rules—should make this questioning easier if we’re willing to divest ourselves of certain beliefs fed to us by those in power. BNHA, as imperfect as it is, certainly tries to raise some of these questions about the designations of “heroes” and “villains,” about the deserving and undeserving, about who is saved and who gets left behind. I would go further, and argue that to invest legitimacy into the hero system is to invest legitimacy into everything that perpetuates it: the poverty, the violence, the disposability of those judged “villainous,” and the idea that agents of the state are uniquely positioned to enact legitimate violence. Confronting crime means eliminating the need for it and the conditions that give rise to it, and only then, not a moment before, will the problem of villains largely cease to exist.

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Profile

+1 to be graced by the beauty of Dr.Sofen

꧁ ❦ | · Karla Sofen · | ❦ ꧂

【 Biodata 】

Name: Karla Sofen

Aliases: Dr Sofen, Moonstone, Kate Sorenson, Meteorite, Ms. Marvel

Sex: Female

Age: Late twenties to early thirties

Species: Human Mutate

Race: American

Relationship Status: Single

Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual

Occupation: Psychiatrist, SHIELD consultant, Initiative psychology teacher, Thief

Education : Medical Doctorate and Psychiatry Doctorate, Masters in Psychology [Undergraduate] UC-DAVIS California, USA

Place of Creation: Captain America (1968) #192

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

【 Physical Specifics 】

Hair: Blonde

Eyes: Blue

Height: 5’11

Weight: 130 Ilbs (59 kg)

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

【 Relations 】

❦ Karl Sofen

Relation: Father

Status: Deceased

❦ Marion Sofen

Relation: Mother

Status: Deceased

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

【 Quotes 】

“Wh-what are you doing to me? I’m – I’m Moonstone again? I’ve been ‘reality-punched?’ That’s the stupidest @#%* thing I’ve ever heard of .”

”It always amuses me how people so ready to do the Devil’s work fall into asking for God’s help when things don’t play out as planned ”

” It’s hard to confront the deep truths about ourselves. Naturally you flee them at first ”

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

【 Personality 】

Dr. Sofen defines herself by her intelligence. And she is defined by a bitter, vengeful desire for social revenge and showing the world who’s the boss and who’s the bitch.

She’s a user and a predator, desiring to be as independent and high-status as possible, through both money and influence.Sofen is proud of having neither morals nor ethics. She sees those as yet another set of constraints that only applies to suckers with a less prodigious IQ than her own. She regrets nothing and stops at nothing. Her only goal is to make it big.

She’s greedy, and very open about it.But she is also smart and disciplined enough than it doesn’t constitute an Irrational Attraction in game terms.

It was a while before she began to want to change. Or before she admitted it to herself, anyway. She seemed to initially stay with the others for the safety of numbers. The desire to redeem herself was so different from her normal way of being and thinking that it took a long time, and intervention by an alien intelligence, to make her understand that she actually wanted it.

She never quite got the being a hero part though. Karla constantly questioned herself about whether she was simply doing what others wanted her to. Her superiority and need for independence make it difficult for her to ask others for help.

She developed a big-sisterly affection for Jolt, and romantic feelings towards Hawkeye, both of which could have influenced her path.Indeed, she worried it was Hawkeye’s influence in particular which had guided her down this path. This doubt may have stopped her being as committed to the relationship as she might otherwise have been.

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

【 Background History 】

Karla grew up in the mansion of a Hollywood producer, the child of a butler. After her father died, her mother worked three jobs to put her daughter through college, and Karla vowed never to end up like her mother, to never put another’s needs before her own. Despite building a successful psychological practice, Karla so disliked being dependent on her patients for income that she entered the super-criminal world as an aide to Doctor Faustus. Learning of Moonstone (Lloyd Bloch), she became his psychologist and manipulated him into rejecting the source of his powers, an extraterrestrial gem of considerable power, which she then absorbed to gain the powers of Moonstone.

Karla worked briefly for the Corporation, controlling the Hulk and manipulating General “Thunderbolt” Ross into a nervous breakdown. She continued to pursue greater power, stealing Curt Connors’ Enervator and searching the moon’s surface for further moonstone fragments. First Egghead and then Baron Zemo recruited Moonstone for their Masters of Evil, and she aided each against the Avengers. After the last of these fights, she decided to serve out her prison term and give up her criminal life. However, when Zemo formed a group of villains to masquerade as heroes, he broke Moonstone out of the Vault and she returned to villainy as the Thunderbolt Meteorite.

Upon encountering a young victim of Arnim Zola’s genetic manipulations, a youngster by the name of Jolt, Moonstone nudged Zemo into accepting her in the team. She soon became a mother figure to Jolt and used her enthusiasm to create a power-base inside the team, rallying the others behind her. Zemo exposed the true nature of the team, but Moonstone opposed him, followed by MACH-1, Songbird, and Jolt. Zemo had brainwashed the Fantastic Four and the Avengers, but the small team of Thunderbolts, with the help of Iron Man, was able to defeat Zemo and Techno, his ally. After the battle the Thunderbolts had decided to pay for their crimes, but they were unwittingly teleported to an alternate dimension.

In this world, known as Kosmos, Moonstone led the team to safety from the Kosmosian army and eventually executed the Kosmosian Primotur to ensure their return to Earth. Inspired by Jolt, she made the Thunderbolts see that it would be preferable to work for their redemption as heroes, rather than to be in jail. After gaining fake identities for the team, she led them away from S.H.I.E.L.D. and the Lightning Rods, and she managed to defeat Graviton using her psychological skills, making him see that he did not truly have a goal, that he lacked vision

. However, the Thunderbolts disagreed with her, for she merely thought of the present and did not care for the future consequences of her actions. When the former Avenger known as Hawkeye joined the team, claiming they would be pardoned if they followed him, she stepped down as leader and allowed him to get the position.

Soon after the Thunderbolts fought the new Masters of Evil, a veritable army of supervillains, and Moonstone decided to betray the team. But something inside of her snapped, and she defeated Crimson Cowl and returned to the team.

Weeks after, Graviton returned, having pondered the words of Karla. He took over the city of San Francisco, turning it into an island in the skies. Thunderbolts attempted to stop him, but they were captured. Graviton offered Moonstone a place at his side, as his queen, but she laughed in his face. As the youngest members of the team saved them, Moonstone wondered why she didn’t take Graviton’s offer.

During a mission against the Secret Empire, she become romantically involved with Hawkeye. But as time went by, she became haunted by nightmares of an ancient alien warrior woman, who whispered in her thoughts. Soon after, the team was targeted by Scourge, who killed Jolt. The death of the youngster hit Karla deeply. Subsequently, Citizen V asked for help against her own team, the V-Battalion, and the Thunderbolts agreed to do so, engaging the V-Battalion’s operatives in battle. Karla was torn about fighting them, for they were heroes. She released a surge of her powers to stop the fight, making them all intangible, and fled, trying to find out what was wrong with her. Her first stop was Attilan, but the Inhumans were gone. She then searched the Fantastic Four’s computers and found the answer she was looking for.

She flew under her own power to the Blue Area of the Moon, where she sought the Kree Supreme Intelligence and demanded the truth. The Supreme Intelligence revealed to her that the fragment she referred to as the “Moonstone” was part of a Kree Lifestone, which used to empower the Guardians of the Galaxy centuries ago. The alien warrior woman that haunted her dreams was the previous owner of the moonstone, whose memory was etched into it, and kept steering Karla into the path of heroism. The Thunderbolts managed to catch up with her, and so did Captain Marvel, who offered her help. Led by Captain Marvel, the Thunderbolts went to Titan, where Mentor and ISAAC attempted to remove the moonstone from Karla’s body. After a serious discussion about Karla’s potential to do good, Mentor allowed her to keep the gem but erased the memory of the previous owner, leaving Karla’s mind, and by consequence, her decisions, to herself.

The team returned to Earth, only to find Jolt alive. She exposed Hawkeye, revealing the pardons Hawkeye promised would not be honored. Soon, the Thunderbolts chased Scourge, who was being manipulated by Henry Peter Gyrich. Thunderbolts fought the V-Battalion’s Redeemers but eventually teamed up with them to defeat Gyrich, who was being manipulated as well. Valerie Cooper offered the Thunderbolts pardon for saving the world from her own people, with the condition that they would hang up their heroic identities forever.

Karla Sofen was soon contacted by Graviton, who hired her as a tutor. In the following weeks Karla helped Graviton understand and control his powers in ways he had not even dreamed, making him fall in love with her. Graviton soon attacked the Redeemers, slaughtering the team. He also managed to keep many of Earth’s heroes unmoving in the sky, as he lifted hundreds of cities all over the world as well, for he wanted to reshape the face of Earth into a semblance of his face. The Thunderbolts re-formed to stop him, only to find Karla at his side. In the end, she hesitated fighting them and helped them stop Graviton. However, his power imploded, sending most of the Thunderbolts to Counter-Earth.

While trapped on Counter-Earth, the Thunderbolts became true heroes at last, rescuing thousands in their flying city, Attilan. Karla was given the task of reshaping the minds of the world’s leaders, creating a new way of thought to ensure the survival of all. Soon after, Karla removed a second moonstone from that world’s Lloyd Bloch (known there as the Phantom Eagle), dramatically increasing her own powers. The Thunderbolts eventually returned to Earth, leaving Jolt and the Young Allies to complete their task of saving Counter-Earth.

When the Avengers later interfered in the Thunderbolts’ plan to control the world’s “transnormal energy”, a failsafe was triggered– a device that Karla had planted in her private plot against Zemo. The stolen energy was funneled into her moonstones, further increasing her powers. Karla attempted to use this energy to flee, but the Thunderbolts and Avengers combined forces to stop her. In the end, Zemo ended up in possession of both moonstones and Karla was left comatose. After recovering, Karla reunited with the Thunderbolts first with Zemo then under the leadership of Norman Osborn. Eventually she took the mantle of Ms. Marvel when Osborn created his version of the Avengers.

Once that venture failed miserably, after the siege of Asgard, Karla found herself back in the Raft prison, but again she was allowed to participate in the Thunderbolts program now led by Luke Cage.

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

【 Abilities 】

The Moonstone embedded in Karla’s body works through manipulation of gravity, and gives her a large toolbox of powers. She has high level super strength, speed, and durability. She is able to manipulate her density and the density of objects around her, allowing her to become intangible and phase through objects and attacks. She can manipulate gravity directly, using it to bend light (making her invisible), increase the gravitational pull of things around her, absorb energy, and even teleport. She can project beams of light as powerful lasers or simply emit bright light to blind opponents. She is a brilliant psychologist and uses her insight and way with words to get into the minds of her opponents in the middle of fights and effectively manipulate them Along with this ability, Karla also has perfect control over her voice. She can alter her pitch and modulation to varying degrees to literally drive a man crazy, as shown with what she did to Red-Hulk.. She is a skilled fighter and can fly at high speeds. She can generate and alter her costume at will, and can regenerate from wounds at a heightened rate.

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

【 Themes 】

❦ A Beautiful Lie

[ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Kvd-uquuhI ]

❦ Pray

【https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lLwKCdxN9vk 】

» ━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━۵━ «

[| Admin’s introduction |]

[| Hello, I see you’ve stumbled unto this other account of mine, whereby I roleplay as the human mutate who happens to be a hero/ villain Karla . Karla is an intricate villainous woman who I shall portray to the best of my ability and these are things you can expect to find here |]

~ Things related to the Marvel Universe

~ Quotes and edits on Moonstone

~ Roleplays

~ Admin posts/ shitposting for those moments when I feel so uninspired

[[ And these are just some of the things I wish to lay down ]]

1) I wish to emphasize when I’m speaking in character, I shall be using ❝ ❞ and for ooc character interactions , I shall be using [[ ]] or the dashes.

2) I’m a fairly nice person (despite the nature of the character I am rping as) so don’t be afraid to ask me if you wish to rp. My replies varies on how many lines one could reply with or if I’m feeling rather inspired during such moment so don’t worry if you think if your reply is too short or too long. Also if I seem to be taking too long on a rp, it’s either I forgot or I got busy.

3 ) No starting any sort of unnecessary drama on my account please for I wish to get along with everyone. With that said, if you have a problem with something I said or posted, don’t be afraid to talk to me about it so we can solve the issue.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[ quietly screaming.FIGHT ME ]

✧ that looks like IRA DRAKE! they’re the TWENTY-FIVE year old son of BOBBY DRAKE. [ they are also a POST GRAD at paragon. ] i hear they’re PROTECTIVE & GENTLE, but tend to be GUARDED & UNSYMPATHETIC. his file says that his power/ability is CRYOKINESIS. { zzy, pst, 28, she/her }

█████ Λ SUMMΛRY

Ira is the biological son of Bobby Drake, i.e. Iceman. His powers, unlike his father’s, are BLACK & MURKY IN COLOR, and his SIGNATURE MOVE involves SHARP, BLACK SHARDS & ICY SPIKES that shoot up from the ground. While his destructive, rebel years in late high school and his early twenties have passed, Ira has to keep a strict routine to manage his emotions and maintain his control over his powers. He’s a straight A student and currently is mostly well-behaved. However, he’s itching for someone to start a fight.

♛ high score king of pinball machines

♚ no queen necessary (gay)

♝ studies philosophy to try to challenge his point of view on the world

♞ protective & gentle to the few he’s close to

♜ guarded & prone to reclusive antisocial tendencies

♟ easily manipulated

currently obsessing over:

beginning work on his thesis, the ethics of heroism vs. villainy

TW: murder, mental disorders, violence

To avoid triggers, skip TW START section.

BIO UPDATES as of 6/12/19

□ header - updated with black ice graphic

□ history - no updates

□ personality - updated

□ wanted connections - no updates

【HISTORY】

BIOLOGICAL FATHER: Bobby Drake i.e. ICEMAN

Biological Mother: unknown

ADOPTED FATHER: name TBD

■ Mother died during childbirth, leaving Bobby as a single parent.

■ Ira’s diagnosed as a toddler with high-functioning autism.

■ Bobby meets a new love interest, (name TBD) who he marries a year later. He adopts Ira.

■ Ira discovers his powers in his early teens like his father, however, Ira’s ice manifestations are pitch black in color (black ice) unlike his dad’s.

■ Bobby was initially excited that his son inherited his cryokinesis abilities, but teaching him how to use them defensively and controlling them passively was a disaster in the beginning. Ira discovered quickly that he likes to offensively use his powers more than he likes to defend.

■ His father’s concern about the ‘differences’ between their powers and Ira’s temperament with them worries him. He unintentionally projects his insecurities onto Ira, causing him to feel like he’s unable to live up to his ‘perfect father’s’ standards.

■ Caught in a whirlwind of emotions he doesn’t understand, Ira rebels against his parents. He starts sneaking out at night to an abandoned warehouse where he can use his powers destructively on inanimate objects to blow off steam.

(TW START: graphic descriptions, violence, murder )

■ A couple of neighborhood bullies see him sneaking out one night and follow him. They start a fight with him, and Ira kills them by skewering them with pitch black icy spikes that shot up from the ground.

(/TW END)

■ When he returns home, he doesn’t tell his parents, nor does he appear to be phased by what he had done. Bobby finds out by a phone call when the bullies are found dead. Ira’s lack of emotion regarding what he’d done (and how he had done it) sets off alarms. Feeling that he’s lost control of his son, and not knowing how to help him, he immediately sends him to Paragon.

■ Hurt and angry about his father’s decision, Ira shuts himself off and feels like he’s in a cage during his senior year in high school at Paragon.

■ [TEACHER WANTED CONNECTION] helps Ira to reel in control over his powers to separate his emotions from them by encouraging him to develop routines. They, along with a couple of good friends, inspire Ira to want to try to be a better person. Ira decides to study what it means to be a good person and control his emotions and thoughts better by pursuing a degree in Philosophy. He’s determined to study his way to being a better person.

【POWERS】

Ira inherited his father’s powers with a few caveats.

❄ He can control moisture to freeze any air moisture into super-hard ice. This ice can be formed into any object of his choosing: the only limitations are his own imagination, and the ambient air temperature which determines how long his ice sculpture will stay icy. He does not have to hold the ice physically with his hands in order to shape it.

❄ He can construct ice walls/columns for defense, but he can not produce long ice ramps to travel on like Iceman.

❄ His body temperature is usually cool to the touch, even on a good day. If he feels anxious, paranoid, angry, or threatened, it’ll drop to freezing conditions to prevent others from being able to touch him.

✘ He does not have a fully ice form like his father.

✘ The ice he produces is pitch black, or murky. Only in rare circumstances when Ira’s in the right mental state is his ice white/lightly tinted blue like his father’s.

✘ Ira’s skin is sensitive to temperature. Hot water hurts him. He hasn’t experienced a hot shower since he was a teenager.

✘ Hot, dry days cripple him. He can use his own body’s water for his powers in the event of an emergency, but doing so puts him at serious risk.

✘ His powers are heavily linked to his emotional and mental state. He’s gone through great lengths to find the right self care routines to manage this.

【PERSONALITY】

☐ HIGH-FUNCTIONING AUTISM (Asberger’s Syndrome)

Ira was diagnosed with high functioning autism when he was a toddler. He struggles to understand others’ emotions, as well as his own at times. His ability to make himself freezing to the touch enables him to reject physical contact with others. He is obsessed with routine and structure, partially because it helps him to maintain a healthy state of mind to keep his powers under control. He does not accept change well, even to a minor degree.

■ can’t keep hands still & has a nervous tick where he jerks his neck

■ incredibly picky about food & forgets to eat when he’s binge-studying

■ interrupting his routine or daily meditation results in immediate shunning

■ sleeps most of the day if he doesn’t have class and stays awake at night

■ struggles to interpret other people’s emotions & facial expressions, usually assumes the worst

■ cares very little about his relationship with his father

■ can quickly become aggressive if he feels threatened

■ sensitive to loud & sudden noises

【WANTED CONNECTIONS】

☯ TEACHER / MENTOR who got threw to Ira during his first few years at Paragon. He goes to them for questions and they help him to develop some sympathy and compassion for others.

♥ FLINGS to distract him.

♞ RIVAL who gets under his skin and has gotten into fights with Ira in the past.

#【C❄LDasICE】✖ ( ira ) about.#//leave it to smirnoff ice to come up with the best representation I could find of Ira's Ice powers

1 note

·

View note

Text

The most brilliant moment of The Last Jedi is that elevator scene between Rey and Ben. Rey tells Ben she’s seen his future and knows that he’ll return to the Light. Ben tells Rey that he’s seen her future, and knows that she’ll join the Dark Side. Of course, neither Ben or Rey switches sides, but they do work together to slay Snoke’s guards. And that retroactively makes the elevator scene brilliant, because that fight scene was the vision they both saw.

The problem is that they each projected their own goals onto the other person. Rey saw Ben helping her to escape Snoke’s guards, and thought this meant he had rejected the Dark Side. Ben saw Rey helping him to slaughter his enemies, and thought this meant she had joined him in his quest to bring a new order to the galaxy. But though they were fighting side by side, they each had completely different motivations.

This ties into the film’s examination of violence and heroism. In the typical Star Wars narrative, fighting the bad guys is unquestionably a heroic action. Rey saw fighting the guards as Ben’s return to the Light. But Ben saw Rey doing the exact same actions and believed it the work of the Dark Side. The uncomfortable truth is that fighting evil doesn’t necessarily make you a hero--it may even make you a villain.

But Rey isn’t a villain--she was fighting so she could escape and help her friends. And Ben isn’t a hero--he was fighting to get revenge and destroy a universe that has disappointed him. But the visions only showed the actions of Rey and Ben, not their motivation, so they only learn the truth after the fight is over. Heroism or villainy isn’t just determined by who you fight--it also depends on your reason for fighting. And though Rey and Ben fought on the same side, their hearts were not in the same place.

#star wars#the last jedi#tlj spoilers#kylo ren#ben solo#rey#i feel like this is really repetitive but i can't think of a better way to say it right now#and maybe this interpretation is blindingly obvious to everyone else#but it struck me a couple days after watching the film and my mind was blown#so apologies if i'm just stating the obvious

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zub Invites Baron Zemo to a Thunderbolts Anniversary Celebration

Marvel Comics’ latest “Thunderbolts” team was formed when the Winter Soldier (AKA Bucky Barnes) and several former team members banded together to protect the living Cosmic Cube fragment, Kobik, from S.H.I.E.L.D. and any other forces looking to exploit her abilities. But by doing so Bucky unwittingly put them all in the crosshairs of his former partner, Steve Rogers.

Kobik used to be under the thrall of Hydra and its villainous master, the Red Skull, who utilized her reality-altering abilities to change history. When she was done, the original Captain America had been a secret agent of Hydra for pretty much his entire life. Kobik broke free son after tweaking the timeline, and the Skull’s forces have been trying to recover her ever since.

Now, Rogers has discovered that the childlike Kobik is in the custody of Bucky and his team. This February, he’ll put his secret weapon against the group into play; a weapon that knows Bucky’s comrades better than almost anyone: Thunderbolts founder, Baron Helmut Zemo. It all happens in “Thunderbolts” #10, by writer Jim Zub and artist Jon Malin, which celebrates the team’s 20th Anniversary and kicks off a new arc titled “Return of the Masters.”

CBR: You recently brought back a long-time Thunderbolt, Songbird, and this February, you’re bringing back another in the form of Baron Zemo. How does it feel to bring him back to the book? And how important do you feel Zemo is to the larger Thunderbolts mythos?

Jim Zub: Zemo is obviously at the heart of the original Thunderbolts concept, so if we have an anniversary issue, we want to bring him into the mix. There’s an element of nostalgia to the series, but it’s not just about retreading what’s been done before. It’s about celebrating the elements at the heart of what has been “Thunderbolts.” There are all these different elements that have built this amazing series and we want to address them all, have them in play, and do some very exciting things with them.

EXCLUSIVE: Art from “Thunderbolts” #10

In short, having Zemo involved is absolutely crucial. He formed the team, instigating the original mystery behind them and their villainous reveal. He’s part of the DNA of villainy that drove the Thunderbolts from the start and that the team members eventually rejected in an attempt to become heroes in their own right. For this special 20th anniversary event he’s got to be at the center of it.

What’s it like writing Zemo?

It’s awesome. Zemo is such a great character because he’s powerful, but not in a raw, cosmic sense. He’s just got the power of personality. He’s pure intent, and I think the way he’s able to drive that leadership and push people towards different ends is what makes him such a valuable character when you’re building a story.

Whenever you put him into the mix there’s always something great you’re going to get out of it; an intense, emotional quality. Regardless of what the other cast members of the Thunderbolts think in terms of their own heroism, what he did for them and the way he was able to unify them at the start, and at a number of other points in their history, can’t be denied. He’s someone who gets things done and I think that’s what makes him such a great character. You add him into the mix, and there’s this instant spark of intensity.

Has Zemo’s personality changed at all in light of history being altered so he and Steve Rogers were childhood friends?

I can’t really speak too much about that. I don’t want to spoil any of Nick Spencer’s story stuff that’s coming up. There are some aspects, though.

One thing I really like about the way Nick is writing Steve Rogers, even when he’s loyal to Hydra and that organization’s ideals, is that he’s still Steve Rogers. He’s still this aspirational figure. He’s doing and planning dark things, but there’s still a charisma to him. He’s still this larger than life figure. It’s great that Steve didn’t just become a mustache-twirling villain. He’s much more nuanced and careful. He’s still a leader even if he’s leading a group that’s villainous or has darker ideas in mind.

Zemo is sort of the same. Helmut has been altered, but at his core he’s still this charismatic, capable, driven person. That makes this work a lot better. It’s not just corny mind control where a person is outright evil and doing dark things for the sake of darkness. They still have their core personality they’re just driven to a different end now because of that historical alteration.

Yeah, I always felt Zemo was a character who had admirable goals, but pursued them via deplorable methods. I think with history being altered Steve has become a similar type of figure.

Right, and that makes for a great villain. You may not empathize with them completely, but there’s a sense of purpose where you go, “I don’t agree with what you’re doing, but I can see how you’d come to this conclusion even if you’re walking the wrong path.”

Zemo has such close ties to the Thunderbolts. He’s been through more with them than anyone else in his history so he has a desire to return to that strength. He feels they have value, but if they won’t join him he’s going to do what needs to get done. I think that’s what’s going to make the conflict so rich here. It’s not just a matter of Zemo showing up and kicking everyone’s butt. He brings hard decisions in his wake and that intensity makes the whole thing spark.

Bucky’s version of the Thunderbolts is different from Zemo’s, but both have been unifying forces, they just put the group in different situations. They’re going to have to make some hard choices especially in the face of stuff we’ve got coming up in the months ahead.

How big a role will Steve play in the “Return of the Masters” arc?

EXCLUSIVE: Art from “Thunderbolts” #10

I can’t really say. [Laughs] The fall out of Bucky’s imprisonment in the just-released “Thunderbolts” #8 and Steve’s involvement there will answer that a bit, otherwise readers will have to wait and see.

In issue #7, we got a little bit of your take on the relationship between Steve and Bucky, but can you talk a little more about how Steve views Bucky in light of everything that has gone on with him?

“Thunderbolts” #8 gives you a stronger sense of that. I can’t go into too much detail, but the way Nick and I have talked about it is that Steve is fond of James. They have a bond there, and they’ve gone on missions together. It’s not that they have no history — it’s just that it’s different than before.

When Steve talks to Bucky in prison, he wants to get Kobik of course, but there’s also a bond between the two of them. It’s not just a cold, calculating kind of thing. Some of that emotion and intensity coming from Steve is genuine.

The way I’ve thought about it, and I talked to Nick about it and we agree, is that, like you said, Steve has his ultimate ends in mind. He doesn’t consider himself a villain. Bucky currently has Kobik, and it’s a huge danger for Steve’s plans to have her to be out there without Hydra’s control. So, when push comes to shove, Cap is going to break towards his ultimate mission, but if he doesn’t have to kill someone he’s not going to.

With Steve, Zemo, Bucky and Kobik all sort of converging together, this story feels like it could be both a milestone “Thunderbolts” story and a pivotal chapter in the long form Steve Rogers tale that Nick is telling in his book.

Absolutely. Nick and I have been working closely together. Before any of this Hydra stuff was announced, I was brought up to speed on where things were going so we could plan it appropriately.

In the first issue of our new “Thunderbolts” series, we laid in some of the Chitauri stuff Nick has followed up on in “Steve Rogers” as well. We’ve been back and forth building some of these different elements, and I think people are going to be surprised at how they pay off later on.

If you’re reading the “Steve Rogers” book, the “Sam Wilson” book, and “Thunderbolts,” you’re getting as complete a picture as you can right now. Obviously, we’re heading towards more dramatic things to come.

What’s it like bouncing Zemo off some of the new members of the Thunderbolts like Kobik and Bucky?

Zemo has interacted with Kobik before during the “Avengers: Standoff” event. He saw her merely as a Cosmic Cube; an object he desired. It’s not as simple a thing now, though. She’s a lot more complicated.

Zemo thinks the Thunderbolts are still his to lead. He knows how to push and pull them and he’s not wrong in some ways, but he doesn’t always have a complete picture and tries to sort of bulldoze over any of the things he doesn’t know about them or care about them so he can get to his ultimate goals

To me, it always felt like Fixer and Atlas had especially conflicted feelings about Zemo.

EXCLUSIVE: Art from “Thunderbolts” #10

Absolutely. They couldn’t deny that he was charismatic and capable. Plus, in some ways he provided them with a structure that they needed.

I’ve always looked at Atlas as a follower. He’s looking for guidance and an authority figure to say, “This is what we need to do, and if we get it done we’re going to win.” When he has that kind of structure he feels most complete, and that’s why he’s really enjoyed being on a team with Bucky. Bucky tells him what to do, and tells him when he’s doing it wrong.

Someone like the Fixer is the same, but his issue is literally fixing problems. It doesn’t matter if he’s doing it for good or evil. I always got the sense the Fixer doesn’t have strong moral leanings one way or another. It’s more, “You give me a platform to show off how amazing I am? I’ll do that for you. You deny my genius and treat me like crap? I’m going to go somewhere else or betray you.”

Since this is a 20th Anniversary issue, are there also nods to other incarnations of the Thunderbolts like the brief “Fight Club” version, and the groups that served as Norman Osborn and Thunderbolt Ross’ personal strike teams?

When I took over the book, I read every single “Thunderbolts” issue with a notepad by my side. I also read “Dark Avengers” — not because I thought I was going to bring everything into play, but I wanted to have a good sense of what had come before. The way I look at continuity is that it all happened, but what areas do I want to emphasize? Or what rings true to me when I’m writing a story? If I can put in little asides or those elements dovetail into the story in a way that makes sense that we can mention stuff from the past, great. I don’t want to shoehorn things in there or make it feel like the Greatest Hits collection; where all I’m doing is callbacks because I feel like that’s disingenuous. Our job as storytellers is to keep this thing moving forward, but the good and the bad of continuity is that it all happened. If an element makes sense, I make sure I bring it in.

The characters have a past and a shared history. I’ll include funny little lines where they talk about Zemo as a leader compared to someone like Norman Osborn. That kind of contrast is something I like to play with, but I’m not trying to check off boxes of every single iteration of the team. When you do that it just becomes a cold exercise in nostalgia. I know that’s not a direct answer, but I’m trying to keep from revealing too much.

How will the action in the “Return of the Masters” arc manifest? Is this a story where Zemo is coming directly at the Thunderbolts? Or is it more of a tale of machinations and subterfuge?

It’s not subtle. [Laughs] It gets pretty intense right from the first chapter. It’s funny because when we were planning it out I had to make sure it was going to work with some of Nick’s plans and I realized that, based on the timing, we had to kick it into gear quite quickly but that actually worked for the best. Rather than starting off slow I thought, “Okay, let’s just open strong and intensify it from there.”

In issue #10 Thunderbolts creators Kurt Busiek and Mark Bagley are coming back to do a short story. When we were bouncing ideas back and forth, I realized what would actually work best based on the pacing was for Kurt and Mark to do the prologue. They’ve created a 10-page opening story that tees up a bunch of cool things for me. It’s part of the big payoff, not just an aside.

We know your artistic collaborator, Jon Malin, can handle action, and it sounds like this arc will have plenty of that, but it also feels like we’ll see him stretch his character acting skills as well since it involves a lot of interpersonal conflict and conflicted feelings.

Yeah, what’s nice about this arc is there’s an emotional intensity. There’s fisticuffs of course, but there’s also a lot of harsh conversations dripping with tension. I think readers are going to be surprised where we take things with issue #11.

So, is it safe to assume that by the time the “Return of the Masters” arc comes to an end the Thunderbolts will be in a very different place as a team if they’re still together at all?

EXCLUSIVE: Art from “Thunderbolts” #10

[Laughs] Issue #12 will be apocalyptic. We’re going to be breaking and building all kinds of stuff. We’ll also be putting them in some pretty cool spots. I hope people who have read “Thunderbolts” are pumped to see the next chapter and excited to let us run with the ball and keep working with such an amazing concept.

The Thunderbolts concept is so rich because it has a complexity to it. They’re villains trying to be heroes and often failing along the way. There are areas of redemption and failure in the concept that I don’t think a lot of other books play with. I like that the characters mess up but keep trying.

I knew Thunderbolts and had read it back in the day, but before I got this assignment I’d never sat down and tried to take it all in at once. When I did that I realized these were the threads that spoke strongest to me and I think speak strongest to the readers. They’re aspects I want to explore, but not just retread. So how can we move things forward in a way that makes sense, but also isn’t too easy to telegraph? Answering those questions while playing in the larger sandbox of the Marvel Universe has been a ton of fun.

I love that a book like “Thunderbolts” can have a 20-year legacy. There was a while there where it became a wonderful gathering place for a lot of lost characters that didn’t necessarily have a home. The Thunderbolts became this weird family that doesn’t really get along, but have this bond with each other. That bond is that they’re all trying to be more than what they are. Sometimes that’s in a villainous direction. Sometimes it’s heroic. It’s a great platform for telling stories.

The post Zub Invites Baron Zemo to a Thunderbolts Anniversary Celebration appeared first on CBR.com.

http://ift.tt/2jqQIv7

0 notes