#torminster

Text

It doesn't matter what century it is or what county they're in, small-town people have opinions, and God help you if you don't agree.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

@saxifrage-wreath kindly tagged me to share a list of my dearest books. What a lovely thing to do!

The Chronicles of Narnia (especially The Magician's Nephew)

The Eliots of Damerosehay (especially The Herb of Grace)

Brideshead Revisited

The Dean's Watch

C. S. Lewis' Letters to Children

Goodbye, Mr Chips

The Wind in the Willows

Gentian Hill

The Dark is Rising Sequence (espeically Over Sea, Under Stone)

The Torminster Trilogy (especially Henrietta's House)

Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries (especially Busman's Honeymoon)

These Old Shades

All Creatures Great and Small (especially Let Sleeping Vets Lie)

The Rosemary Tree

Piranesi

Lord of the Rings (especially The Two Towers)

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Harry Potter (especially and the Prisoner of Azkaban)

Summer Lightning

Linnets and Valerians

I tag anyone who'd like to do this!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells fic!

i searched up fics for the book just in case there were any, and there was one--a superbly written one detailing the events leading up to Felicity and Jocelyn's wedding, the people of Torminster's utmost satisfaction of the match, and the conclusion of the Problem with the Drains.

#I will say the very last part is a little bit of a downer#The complete opposite of the City of Bells' ending--Ferranti going away again#But still I guess it's to be expected#Such a charming fic that tried very hard to keep to the original flavor of the text!#clary scribbles#Elizabeth Goudge#A City of Bells

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

…it struck him that in all the world he would be able to find no more peaceful city in which to build their home.

A City of Bells by Elizabeth Goudge

#elizabeth goudge#a city of bells#torminster#wells#literature#quote#beautiful things#all the gifts of earth

172 notes

·

View notes

Photo

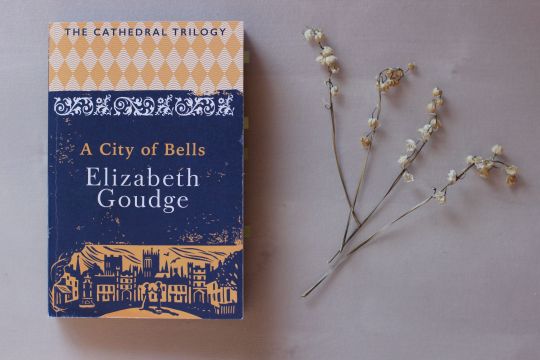

I last read...

‘A City of Bells’ by Elizabeth Goudge

what I wanted: a classic with a book-focus

what I got: a book that’s endearing but also doesn’t shy away from some of life’s tough questions

what I thought: This book felt somewhat like Anne of Green Gables + philosophy. I enjoyed the lovely descriptions of life in Torminster through the eyes of people who are capable of wonder and enjoying the little things in life, and I was really pleasantly surprised by the many philosophical musings the book offered on top of that. The characters and writing were delightful, and it really was a very pleasant reading experience, which is why I rate it 4 out of 5 lily of the valley stems one might be able to find in Torminster.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just gonna leave this one here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'm a little late to the party, but I'm busy catching up on A City of Bells by Elizabeth Goudge. It reminds me of some of the stuff I read growing up, particularly By the Shores of Silver Lake by Laura Ingalls Wilder, as well as some of my personal experiences with small-town life. I'm intrigued by the story, and there is so much description.

Jocelyn's introduction to Torminster reminds me of Kazuma Kiryu's life running the orphanage in Okinawa, and then later trying to establish a life in Onomichi with Haruto. The circumstances surrounding both men are of course very different, but there's a certain mystique to the quiet of rural living that soothes harsh wounds.

Inept thoughts will surely continue as I progress.

#a city of bells#dracula daily lit a fire that doesn't want to be put out#serial literature it is!#yakuza#kazuma kiryu#torminster#elizabeth goudge

1 note

·

View note

Note

Top 5 books I should read if City of Bells changed my life for the better

Oh my! Really, really more Goudge. In particular (and I'm cheating here):

1. Henrietta's House & Sister of the Angels (aka the other two Torminster books)

2. The Herb of Grace (or the whole Eliot trilogy)

3. The Dean's Watch (!!!)

4. Gentian Hill

5. The Scent of Water

(I also especially recommend The Rosemary Tree, but not so much in a Torminster sort of way)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter I — Part III

Jocelyn realized with something of a shock that the train was standing still in a perfectly ordinary station. Machines holding matches and chocolates faced him, and a beery porter was obligingly withdrawing his bag from beneath his legs. He had for a moment seen the real Torminster, the spiritual thing that the love of man for a certain spot of earth had created through long centuries, but now he was back again in the outward seeming of the place. Torminster, he supposed, would have dustbins like other towns, and a horrible network of drains beneath it, and tax collectors and public-houses. It might even look ugly in a March east wind and smell abominably stuffy on an August night, but these unpleasant things would now never matter much to him, for he would feel towards Torminster as one feels towards a human being when one has, if only once, seen the soul flickering in the eyes.

“Take the bus,” Grandfather had said and Jocelyn accordingly took it. The Torminster bus, once experienced, was never forgotten. In shape and colour it was like a pumpkin and its designer had apparently derived inspiration from the immortal conveyance that took Cinderella to the ball. It was pulled by two stout bay horses and driven by Mr. Gotobed, a corpulent gentleman clothed in bottle-green with a wonderful top-hat poised adroitly on the back of the head. His face was red, his whiskers pronounced and his language rich … He and the Dean together were the outstanding figures of Torminster.

“Get in, sir,” he said genially to Jocelyn. “I was ordered for you by the reverend gentleman. Fine day. Come on with that luggage, ’Erb. One gentleman for the Close and four buff orpingtons for The Green Dragon.”

Jocelyn was established on one of the two wooden seats that ran the length of the bus, with the buff orpingtons complaining of their lot and straining agitated necks through the slats of the crate on the seat opposite him.

“All aboard?” continued Mr. Gotobed, as though they were bound for the North Pole. “’Eave up the gentleman’s bag, ’Erb; we can’t sit ’ere all night while you calculate ’ow many drinks you’ve ’ad since Christmas.”

’Erb heaved up the bag and slammed the door while Mr. Gotobed climbed to the box, flourished his whip, laid it across the backs of the horses, told ’Erb what he thought of his ancestry and set the pumpkin in violent motion.

The outcry of the buff orpingtons was now drowned, for the wheels of the bus were solid and the streets of Torminster in many places cobbled. Jolting through it, and shut away from the subdued hum of its life by the walls of the bus, Torminster once more seemed to Jocelyn to lack everyday reality. The soft, moist air was the atmosphere of dreams and the old houses that lined the streets seemed to be leaning forward a little, as though drowsily nodding. The bus made such a noise that the few vehicles that passed them went by unheard and the handful of passers-by, though their lips moved and their feet trod the quiet pavements, were silent as the dead. Down the side of the sloping High Street, as they climbed up it, a little stream came hurrying down to meet them and Jocelyn gazed at it enchanted. Its water was clear and sparkling as crystal and it must have come down from the hills that surrounded Torminster. The bus stopped for a brief, respectful moment, to let the Archdeacon’s plum-pudding dog cross the street, and he could hear the stream’s ripple and gurgle … What bliss, he thought, to keep a shop in Torminster and do business to the sound of running water and the chiming of bells.

The High Street ended abruptly and they were in the Market Place, a wide, open square surrounded by tall old houses with shops below them. There was no one in the Market Place, except one old gentleman and two cats, and the peace of this centre of industrial life was complete. In the centre was a holy well that had been there before either the city or the Cathedral had come into being. A high parapet had been built round it, with a canopy overhead, and if you wanted to look inside the well you had to mount a flight of steps. The water, that welled up no one knew how far down in the earth, was always inky black and when you leaned over to look in you could see your own face looking back at you. Sometimes it stirred with a mysterious movement and then the sunlight that pierced through the carved canopy touched it with shifting, broken points of light like stars. There were always pigeons wheeling round the holy well, the reflection of their wings passing over it like light. There were pigeons there now, and it seemed to Jocelyn that their wings splintered the veiled sunshine into falling showers.

The bus clattered round the Market Place and stopped with a flourish in front of The Green Dragon. It was a small hotel and public-house combined, its old woodwork glistening with new paint and its windows shining with prosperity. The dragon, his scales painted emerald green, and scarlet fire belching from his nostrils, pranced upon an azure ground over the porch. Here it seemed that they would wait a long time, for Mr. Gotobed, after the exhaustion of carrying in the buff orpingtons, stopped inside to refresh himself.

Jocelyn got out and strolled a little way up the pavement, and then stopped stock still and stared. The most important moments of a lifetime seem always to arrive out of the blue and it was here that Jocelyn, his thoughts objectively busy with this Hans Andersen city, experienced a subjective moment that startled him like a thunderclap.

Between the tall Green Dragon and the equally tall bakery two doors off was wedged a little house only two stories high. Its walls were plastered and pale pink in colour and its gabled roof was tiled with wavy tiles and ornamented with cushions of green moss. There were two gables, with a small window in each, and under them was a green door with two white, worn steps leading up to it. A large bow-window was to the right of the door and a smaller one to the left. There was something particularly attractive attractive about the bow-window. It reflected the light in every pane, so that it looked alive and dancing, and it bulged in a way that suggested that the room behind was crammed so full of treasures that they were trying to press their way out. But yet it was in reality quite empty, for Jocelyn could see the bare floor and the walls papered with a pattern of rose-sprigs. Behind the house he thought that there must be a garden, for the top of a tall apple-tree was just visible behind the wavy roof.

The house affected him oddly. He was first vividly conscious of it and then overwhelmingly conscious of himself. His own personality seemed enriched by it and he felt less painfully aware of his own shortcomings, less afraid of the business of living that lay in front of him. He had felt like this once before, at the beginning of an important friendship.

“Why is that house empty?” he asked Mr. Gotobed, when that worthy returned to his duties wiping his mouth with the back of his hand.

“Because the gentleman what ’ad it ’as gone away and no one else ain’t taken it, sir,” explained Mr. Gotobed patiently.

“But why has no one taken it?”

“No drains,” said Mr. Gotobed briefly, and climbed to his box.

Jocelyn was now the only passenger left in the bus and they completed the circuit of the Market Place and turned to their right up a steep street at a smart pace. Then they turned to their right a second time and passed under a stone archway into the Close.

Instantly it seemed that they had come to the very centre of peace. In the town beyond the archway there had been the peacefulness of laziness, but here there was the peace of an ordered life that had continued for so long in exactly the same way that its activity had become effortless. Outside in the town new methods of buying and selling might conceivably be drowsily adopted, or some slight modernization of the lighting system might take place after a year’s slow discussion of the same, but inside in the Close the word “new” was unknown. Modernity had not so far touched it and even to admit the fear that it might do so seemed sacrilege.

Jocelyn, as the bus rolled along, looked across a space of green grass, elm-bordered, to the grey mass of the Cathedral. Its towers rose four-square against the sky and the wide expanse of the west front, rising like a precipice, was crowded with sculptured figures. They stood in their ranks, rising higher and higher, kings and queens and saints and angels, remote and still. About them the rooks were beating slowly and over their heads the bells were ringing for five o’clock evensong. Behind the Cathedral rose a wooded hill, brilliantly green now with its spring leaves, the Tor from which the city took its name.

“What a place!” ejaculated Jocelyn, and held on to the seat in delighted excitement. To his left, on the opposite side of the road to the Cathedral, was another, smaller mass of grey masonry, the Deanery, and in front of him was a second archway.

Once through it they were in a discreet road bordered on each side with gracious old houses standing back in walled gardens. Here dwelt the Canons of the Cathedral with their respective wives and families, and the few elderly ladies of respectable antecedents, blameless life and orthodox belief who were considered worthy to be on intimate terms with them.

The bus stopped with a jolt at Number Two the Close and Jocelyn got out in front of a blue door in a wall so high that only a grey roof and the tops of some trees could be seen above the wallflowers that grew on top of it. He felt the thrill of excitement inseparable from a walled house and garden; for a house behind railings has no secrets, but a home behind walls holds one knows not what. He opened the door and went in, and Mr. Gotobed, following him with his bag, banged it shut. There was something irrevocable in its clanging and Jocelyn felt that the old life was now dead indeed. Something new was beginning for him and this lovely garden was its starting point.

#torminstertravels#booklr#bookish#literature#a city of bells#elizabeth goudge#a city of bells: chapter 1

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter IX — Part IV

After this pious interruption the party became secular again. There was snapdragon in the darkened banqueting hall and races in the gallery, followed by the giving of prizes to the winners of the races and a few speeches. It was one of the habits of Torminster, a habit to be deplored, that upon every possible occasion it spoke. There were speeches at the choir-school prize-giving, speeches at the annual missionary sale of work, speeches at drawing-room meetings, speeches at concerts in aid of charity and, as if that was not enough, speeches at the party. Why there should be speeches at the party no one knew, but there always had been speeches at the party and so there always must be.

When the races had all been run, the orange-and-tea-spoon race, the three-legged race, the wheel-barrow race, the hopping race and all the others, they sat down, the boys on the floor and the grown-ups on chairs, and the Bishop said a few words.

He made them as brief as possible, hoping that others might follow his example. He merely told his guests what a delight it was to entertain them at the Palace—at this point Baggersley, who sometimes, like Grandfather, spoke his thoughts aloud, began to say something forcible to the contrary, but his remarks were drowned by a very loud fit of coughing on the part of Barleycorn—hoped the boys had enjoyed themselves and congratulated Binks Major and Minor, Hopkins Minor and Jenkins upon carrying off the prizes. Then he sat down and the Dean got up, clearing his throat and grasping the lapels of his coat in his beautiful hands.

With the light shining on his silver-white hair and whiskers he looked magnificent. His coat was without a crease and on his gaiters every button was done up. His diamond ring sparkled and the toes of his boots, just showing below his gaiters, shone like glass … Torminster glowed with pride. Not every Cathedral city, it thought, had a dean like theirs. You could have put him down anywhere and within two minutes he would have looked as though he owned the place.

“Dear friends and dear boys,” fluted the Dean. This party, he felt, always had too worldly a tone—out of the tail of his eye he could see that the prizes the Bishop would soon bestow on Jenkins, Binks Major and Minor and Hopkins Minor were boxes of fireworks and water-pistols—and he always did his best, in this speech, to raise things to a higher level. He did so now for a full quarter of an hour. He told the boys how grave and noble a calling was that of a choirboy. He likened them all to the infant Samuel serving in the Temple. He went on a long time about the infant Samuel. Then he warned them very seriously, with a sidelong glance at the fireworks, of the pernicious effects upon the character of frivolity. In the midst of life, he said, we are in death, and we should not allow pleasures to lull us to forgetfulness of our sins. Then he sat down amid loud and prolonged applause, for really, the boys thought, the old boy had looked splendid while he gassed, and dear old Canon Roderick, the senior canon present—for it was impossible to get Canon Elphinstone’s bathchair up the Palace stairs—tottered to his feet. Everyone loved Canon Roderick, for he had a face like a rosy apple and he never saw a child but he gave it sixpence. Moreover he always made exactly the same speech, both at the prize-giving and at the party, so that you knew exactly where you were and could applaud automatically in the right place without having to listen too hard. He always related the histories of his own sons—now elderly men—for he found, he said, that young people always like to hear about other young people. They began with Tom and followed his career through Eton and Sandhurst and into the army, went with him to India where he won distinction in a frontier skirmish, scurried at his heels to South Africa, where he won the V.C.—terrific cheers—and finally settled down with him in Hampshire where he was now, would you believe it, a retired general. Loud cheering, and they passed on to James, a sailor, following with deep interest and for the twentieth time as he climbed from midshipman to admiral and greeting his final elevation with a storm of cheering that nearly brought the roof off. Charles, a doctor, was a rugger blue—loud cheers—and Thomas, a schoolmaster, was a double first—rather subdued cheers. Henry was a leading barrister and last of all Edward, the baby, was actually a bishop. At this point, the company being what it was, the applause became deafening. Cheers, claps and even stamping greeted the achievement of Edward. Canon Roderick was helped to his seat, with his rosy face beaming with pride, and the Archdeacon rose to take his place with one of those speeches without which no prize-giving, not even a tiny one, is complete.

He began by saying that people who make long speeches are a great nuisance. Then for ten minutes or longer he explained why it is that they are a nuisance. Then he spoke a few words of congratulation to the boys who were to receive prizes, then a few words of consolation to the boys who would not receive prizes—conveying the impression that on the whole it is better not to receive prizes—followed by a few words to the grown-ups, followed by a peroration during which he suddenly stepped backwards on top of some potted plants and sent them flying.

The choir-school headmaster seized this opportunity to get up and begin his speech, which was always the last to be made at the party, hoping by this ruse to prevent anybody else from saying anything, for time was getting on and the longer they were over the speeches the longer it would be before his wife could get the boys to bed and there would be a little peace. On behalf of the choir he thanked everyone for their kindness and sat down.

It then seemed that Canon Allenby was going to make a speech, for he began to pant and grunt and heave his large person forward in his chair, and the headmaster cast a glance of anguished entreaty at the Bishop, for there was no reason whatever why Canon Allenby should make a speech, and once he started he never stopped … The Bishop got up hastily, while Canon Allenby was still heaving and grunting, and called upon Binks Major and Minor, Hopkins Minor and Jenkins to come and receive their prizes … Henrietta felt unhappy, and she could see that Grandfather felt unhappy too, for it was obvious that Canon Allenby was put out, and the old ought not to be put out. Let the young be put out, thought Grandfather fiercely, for the self-adjustment necessary to getting in again is so good for them. Then both he and Henrietta felt happy once more, for they saw the Dean give Canon Allenby a glance of commiseration behind the Bishop’s back and Canon Allenby, who adored the Dean and felt exactly as he did about the Bishop, was comforted.

The four boys received their prizes amid renewed applause and it was time for hide-and-seek all over the house.

The ardour of the grown-ups now began to cool a little and those of them who only liked children within reason gradually melted away, leaving behind those who after four hours of a party still liked children; on this occasion Mr. Phillips, Felicity, Jocelyn—though perhaps he only stayed because he liked Felicity—Hugh Anthony, Henrietta, Grandfather and the Bishop. The two latter, when hide-and-seek was well started, sank into chairs before one of the fires in the gallery, stretched their feet to the blaze, folded tired hands and meditated silently upon the amazing vitality of the young.

At eight o’clock the dishevelled children, their heated faces smeared with dirt and their Etons ornamented with cobwebs, were assembled in the banqueting hall and again fed, after which they all went home … It had been a grand party. The Bishop and Baggersley, as they saw their guests off at the hall door, could scarcely stand, while Grandfather did not refuse Jocelyn’s offer of an arm home.

Felicity walked behind with the children.

“I’ve milked my front,” said Hugh Anthony triumphantly, “and torn the seat of my trousers.”

“You’re a wicked boy,” said Henrietta, “and your suit will have to be given to the poor … I’m not milked or torn,” she continued with pride, and opened her coat for Felicity to see.

It was quite true. She was one of those fortunate people who are never untidy. Whatever Henrietta might do, and to-day she had fished raisins out of the snapdragon, slid down the banisters and hidden in corners that the Palace housemaid, having no mistress, consistently overlooked as a matter of principle, she always emerged at the end of it with unruffled hair and spotless dress. At this moment, in her blue frock in the moonlight, with her opened coat held out like wings and her eyes stars in her tilted face, she looked as much like a little angel as makes no difference.

“Oh, but I love you!” cried Felicity, and the garden door of Number Two the Close being now reached she gave way to that extravagance of action which so annoyed those who did not like her, went down on her knees in the snow and flung her arms round both children. “Don’t ever go away from me,” she implored them. “Never. Never.” Hugh Anthony, kissing her chin politely, wriggled and went away but Henrietta remained, pressing closer.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter IX — Part II

There was no need to ring at the front door, for it stood hospitably wide open, and Peppercue and Barleycorn, who always assisted the Bishop’s decrepit old butler Baggersley on festive occasions, were hovering about to help them off with their coats. The huge stone-floored, vaulted hall was very cold and they parted with their wraps reluctantly. “There are two fires lit in the gallery,” whispered Baggersley, with intent to cheer, and totteringly led the way up the lovely carved staircase.

Baggersley was very old, looked like a tortoise and was not of the slightest use. His dress clothes, green with age, hung loosely upon his withered old body and he could not now remember anyone’s name, but suggestions that he should be pensioned off were not favourably received by him, so the Bishop kept him on … “A disgrace to the place,” the Dean said. “A—er—disgrace.”

“Archdeacon Jones and family,” quavered Baggersley at the gallery door and the Fordyces, Mrs. Jameson, Felicity and Jocelyn trooped smilingly in. The Bishop, whose sight was poor, had a moment of confusion until Grandfather whispered hoarsely, “’Smee, Bishop,” when he identified them with relief. The shortness of Baggersley’s memory, together with the shortness of his own sight, made the arrival of guests something of a strain.

Few lovelier rooms were to be met with at this time in England than the gallery of the Bishop’s Palace at Torminster. It stretched the whole length of one wing of the Palace and was perfectly proportioned for its length. The polished floor shone like dark water and the linen-fold panelling on the walls roused the students of these things to ecstasy. At each end of the gallery a log-fire was blazing, its glow reflected on floor and walls, and in the centre was a Christmas-tree, its top reaching to the ceiling and its branches laden with twinkling candles and presents done up in coloured paper. The choirboys stood in an excited group near the tree, looking terribly clean in their Etons, their faces shining with soaps and their eyes with expectation, while near them stood the dignitaries of the Close with their dependents, smiling with the urbanity of those who feel themselves to be in the position of benefactors but yet have had no bother with the preparations. It was certainly a great occasion, and from the walls of the gallery the former bishops of Torminster looked down upon it from their portraits, the flickering firelight playing queer tricks with their painted faces so that some of them seemed to smile at the happiness, and some to frown at the frivolity, while one gentleman at the far end of the room was distinctly seen by Henrietta to raise a hand in blessing.

The choirboys’ presents were given first. Peppercue and Barleycorn mounted two rickety step-ladders and cut them off the tree, calling out the boys’ names in stentorian voices, while Baggersley trotted round in circles calling out instructions to Peppercue and Barleycorn, after the manner of those who while doing no work themselves see all the more clearly how it should be done. Paper and string strewed the floor and happy squeals greeted the appearance of knives, watches, whistles, blood-curdling books about Red Indians and boxes of those explosives which, when placed beneath the chairs of corpulent relations, go off with loud and satisfying reports … The Bishop always insisted upon this type of present, disregarding the complaints of the Dean and Lady Lavinia who maintained that they were in no way calculated to improve the morals of the dear boys. “No one,” said the Bishop, “wants to be bothered with morals at Christmas”; which the Dean and Lady Lavinia considered such an outrageous remark that they were careful not to repeat it … Delight mounted higher and higher, reaching the peak of ecstasy when the tree caught fire and Barleycorn fell off his step-ladder, Baggersley remarking with acid pleasure that he had said so all along.

Grandfather took advantage of the confusion and howls of joy that ensued to press little packets into the hands of his young grandchildren. He remembered from his own childhood how difficult it is to watch other children receiving presents when you do not get any yourself. You may have a toy-cupboard at home stocked with good things, you may be going to a party every day for a fortnight, but it does not make any difference, for in childhood there is no past and no future, but only the joy or desolation of the moment. The tight, polite smiles that Henrietta and Hugh Anthony were maintaining with difficulty changed in the twinkling of an eye into happy grins as knobbly parcels were slipped into their hot palms from behind … Surreptitiously they opened them … A tiny china teapot and a box of pink pistol-caps numerous enough to turn every day of the next fortnight into a fifth of November.

Looking over their shoulders they saw Grandfather standing with his back to them, gazing with an appearance of great innocence at a portrait of an eighteenth-century bishop with a white wig and sleeves like balloons … They chuckled.

The fire put out and Barleycorn smoothed down, they all went downstairs to the banqueting hall for tea.

The original banqueting hall, where kings and queens had feasted, was now a ruin standing out in the Palace grounds in the moonlight, but its name had been transferred to the sombre great room below the gallery, where damp stains disfigured the walls and where the wind always howled in the chimney.

Not that this worried the choirboys, for the Bishop’s cook had surpassed herself. They sat themselves down round the groaning table and they did not speak again.

But at the buffet at the far end of the room, where the grown-ups balanced delicate sandwiches and little iced cakes in their saucers, there was a polite hum of conversation. Extraordinary, thought Hugh Anthony and Henrietta, who had to-day to be perforce counted among them, how grown-ups talk when they eat. Don’t they want to taste their food? Don’t they want to follow it in imagination as it travels down that fascinating pink-lined lane to the larder below? Sometimes Henrietta tried to picture that larder. It had shelves, she thought, and a lot of gnomes called “digestive juices” ran about putting things to rights … Or sometimes, unfortunately, forgetting to.

“Please,” said Henrietta plaintively to Felicity, “could you hold my cup while I eat my cake? It’s so dreadfully difficult not sitting down.”

Felicity, who had finished her own tea, was most helpful. She held Henrietta’s cup in one hand and with the other she held the saucer below the cake so that Henrietta should not drop crumbs on the carpet.

“Shall I hold yours, Hugh Anthony?” asked Jocelyn, for Hugh Anthony’s cup of milk was slopping over into the saucer in the most perilous way.

“No, thank you,” said Hugh Anthony, and his eyes were very bright because he had just had a brilliant idea.

Putting it into immediate practice he placed himself and his cup behind the Archdeacon, who was holding forth to Mrs. Elphinstone about total abstinence. Now when the Archdeacon held forth he had a curious habit of stepping suddenly backwards when he reached his peroration. He did it in the pulpit, frightening everyone into fits lest he should fall over the edge and kill himself, and he did it on his own hearthrug so that in winter his visitors had to keep a sharp look-out and make a dash for it when his coat-tails caught the flames, and he did it now. “Temperance, my dear lady,” he said to Mrs. Elphinstone, “is the foundation stone of national welfare,” and stepped backwards on top of Hugh Anthony.

Everyone rushed to pick the poor child up. He was patted, soothed, kissed, and the milk that had spilled all over him was mopped up, though it was distressingly evident that his velvet suit was ruined.

The courage with which Hugh Anthony bore the pain of his trampled feet was much admired by everyone but Henrietta, for Henrietta, standing grave-eyed and aloof, knew quite well that he had done it on purpose.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter VIII — Part I

As soon as the festival was over St. Martin withdrew his summer and the rain came down in the way peculiar to Torminster, day after day of steady, penetrating downpour that made everybody and everything feel like a saturated sponge. It was very cold in the old, damp bedrooms of the Close. Grandfather got rheumatics very badly in his knees and Grandmother in her hands, and Henrietta sneezed incessantly. Hugh Anthony’s health remained unaffected, though he felt the chill of his little bedroom to such an extent that his nightly query was, “Grandmother, need I wash?”

Jocelyn, now that winter was upon them in good earnest, found the discomfort of a house without modern conveniences acute. His morning’s cold bath lacked thrill, but to boil enough water in his two little kettles for a hot one took a good hour. A large and loathsome fungus appeared in the corner of his bedroom and the paper in the hall peeled off with the damp. Very few customers came to the shop and he found a dead rat in the bread-bin. Martha Carroway went down with bronchitis and Mixed Biscuits with distemper. Jocelyn himself caught a bad cough through sitting up with Mixed Biscuits at night, and his balance at the bank mysteriously disappeared.

But the worst of all his trials was the mess he was getting into over Ferranti’s dramatic poem. The more he worked at it the more convinced he became that it was amazingly beautiful poetry, but though the plot of the story was mapped out to the end the actual writing was only a little more than half finished, and Jocelyn found himself obliged to fill up the gaps with his own verse.

And though, like everyone else, he had written passable poetry in his youthful days he did not find it so easy now that life and its disillusionment had a little dulled his perception of beauty and his response to it. “How is it that artists keep their powers of perception even in the days when life darkens?” he asked himself. Thinking about it and taking as his model Grandfather, an artist in religion who had given to its study the devotion and the hours of discipline that a violinist devotes to his instrument, he thought that their perception was born of the faculty of wonder, deepening to meditation and to penetrating sight and so strong that it could last out a lifetime. Grandfather wondered, all day and every day, at the wisdom of God and the beauty of the world, and Ferranti had wondered at the waste and pain and frustration of life.

In him, judging from the scraps of poems that had been rescued from Mrs. Jameson, wonder had become a sense of outrage, but it had had its fruits of meditation and a rather terrible penetration. The verse that expressed it was vivid as lightning and cruel as a microscope in its power of enlarging horror.

So Jocelyn too tried to acquire the perceptive outlook, the outlook of Hamlet when he cried, “This most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire.” Even the bitter words that followed, “it appears to me no other than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours,” were the words of an artist, Jocelyn thought, stabbing like a sword in their quick flash from joy to despair. Night after night and during every spare moment of the day he steeped himself in Ferranti’s poetry, and in all poetry that seemed to him akin to it, and he tried to feel every trivial happening of the day acutely and see every beauty and sorrow trebly intensified. And, though he reduced himself to a nervous wreck, he had his reward, for his verse became more and more like Ferranti’s, lighter and clearer and with a winged quality that Henrietta would have told him, had she heard it, made it jump up like a lark.

Not that Jocelyn thought so. Domestic trials and the weather and his own nervous exhaustion had reduced him to depths of depression as yet unplumbed by him. When at midnight on Christmas Eve he wrote the last word, completely unsatisfied yet knowing that he could not get the thing better, he felt that he had failed Ferranti utterly … This man Ferranti whom he had never seen and yet who, alive or dead, had mysteriously become his friend.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter VII — Part IV

At ten minutes to three Grandmother was sitting in her pew in the choir with the children one on each side of her. She wore her Sunday clothes and carried her best umbrella, that she never used unless it was sure not to rain. She had three umbrellas; one for rain, one for uncertain weather and one for fine weather. Henrietta wore her new red winter coat trimmed with beaver, with a round beaver cap on her head and a little muff hung round her neck on a chain. She was much too hot, but she did not mind because she knew she looked very sweet. Hugh Anthony, in his new nautical overcoat with brass buttons, neither knew nor cared what he looked like, but was comforted in his heated state by a whistle on a white cord. For years he had been telling his grandparents that a whistle should always accompany marine attire and now at last, just in time for the festival, this remark had sunk in. With his lovely eyes fixed on the altar and an expression of great spiritual beauty on his face he was wondering just when to blow the whistle. Should he accompany the last hymn on it or should be blow one shrill blast in the middle of the Dean’s sermon? It was difficult to decide. He must, as Grandfather said one should, wait and be guided.

The ladies of the Close had their pews near the altar and these were always reserved for them. Lady Lavinia had the front pew on the right with the Palace pew opposite her across the aisle. Behind these were ranged the pews of the Canons’ ladies in order of seniority. Barleycorn, the second verger, attired in his black gown and carrying his wand of office, was in charge of these pews, and it was his business to see that no presuming stranger dared to sit itself down in the seats of the mighty. It sometimes seemed to Henrietta that Barleycorn thoroughly enjoyed the ejection of a stranger. He would wait until the poor wretch had lowered itself, very tentatively, on to the square of wood sacred to Lady Lavinia and then he would glide swiftly forward with an expression of horror on his face, his gown floating behind him and his wand outstretched like the neck of a hissing swan. There would be a whispered colloquy, and the poor stranger would get up and creep away as though detected in the act of shoplifting, leaving its umbrella behind … On these occasions Henrietta detested Barleycorn, for she hated to see people made to feel ashamed.

But to-day no one sat down where they should not and very soon Barleycorn hurried away, a bell tinkled, they all rose to their feet and far away the choir were heard singing a hymn, “Ye holy angels bright,” as they came in procession from the vestry.

And now they had reached the entrance to the choir and were passing under the carved angels of the screen, the sound of their singing swelling gloriously.

Henrietta, her muff swinging and her hands holding her prayer-book upside down, forgot all distractions in her excitement as the procession came up the choir. First came one of the masters of the choir-school holding the great golden cross and after him came the choirboys singing fit to burst themselves, and then the choirmen singing more moderately but yet with extreme heartiness:

“Ye blessed souls at rest,

Who ran this earthly race,

And now, from sin released,

Behold the Saviour’s face,

His praises sound,

As in His light

With sweet delight

Ye do abound.”

After them came another choir-school master carrying the patron saint’s banner, a needlework picture embroidered in blues and greens and pinks and purples. It showed the saint, attired in his swineherd’s get-up, sitting beside the holy well and brooding sadly over the sins of the Torminster valley. At his feet flowers grew—pansies and violets and cowslips—and behind him were the blue hills, and up in the sky the Angel Gabriel was sitting comfortably on a cloud and holding an architect’s model of the Cathedral on his left palm. It was a beautiful picture, but by some extraordinary oversight the pigs had been omitted.

Behind the banner came Peppercue and Barleycorn, the vergers, followed by the Dean and Canons and the Archdeacon.

The combined ages of the Dean, the four Canons and the Archdeacon at this time came to four hundred and eighty-four, but it was marvellous how they got about. First came the two juniors, Grandfather and the Archdeacon, aged seventy-eight and eighty, who walked quite easily without sticks, then came Canon Allenby aged eighty-two, who used one stick, and Canon Roderick aged eighty-six, who used two sticks, and behind them came Canon Elphinstone aged eighty-eight in his bathchair, pushed by his gardener.

The Dean, who was only seventy, came behind the bathchair and was apt to complain to his wife that shepherding his Chapter in a procession made him feel exactly like a—er—nursemaid … The Dean never used strong language, but in conversation he quite unconsciously left expressive pauses where he would have used it had he not been a clergyman.

Behind the Dean came the Bishop’s chaplain carrying the Bishop’s pastoral staff and behind him came the Bishop’s cope with the Bishop just visible inside it, limping a little because his sciatica was bad that day. Spiritually the Bishop was a very great man, but physically he was not, being small and thin and lacking that autocratic bearing that made the Dean such a fine figure of a man at dinner-parties. The Dean and Lady Lavinia always patronized the Bishop a little. The man lacked private means and as a result the soles at his dinner parties were lemon, not Dover … But it was noticeable that people in difficulties always went to the Bishop for help rather than to the Dean.

“My soul, bear thou thy part,

Triumph in God Above,

And with a well-tuned heart

Sing thou the songs of love:

Let all thy days

Till life shall end,

Whate’er He send,

Be filled with praise.”

They all filed singing into their seats and knelt down to pray and Henrietta found to her delight that she was feeling good, a feeling she adored. Tears of happy emotion pricked behind her eyelids, her throat swelled and she was certain that she was never going to be naughty any more. God and His angels were near and one only had to be absolutely good and everything would be perfect … It was all quite easy.

“Shall I blow it now?” whispered Hugh Anthony, nudging her behind Grandmother’s back.

“Blow what now?” demanded Henrietta, opening her eyes.

“My whistle.”

“You dare blow your beastly whistle! You dare!” she whispered savagely. She was in an ugly rage that tore at her. She stretched across Grandmother, dragged the lanyard roughly over his head and buried it and the whistle in the depths of her muff. “You beast! You beast!” she panted.

“Here, give me that back,” said Hugh Anthony loudly. “It’s my whistle.”

Lady Lavinia, Mrs. Elphinstone, Miss Roderick, Mrs. Allenby and all the ladies of the Close raised their bowed heads and gazed at the couple more in sorrow than in anger … Really, if Mrs. Fordyce must adopt children at her age she could at least make some attempt to keep them in order during divine service.

Grandmother made it, for she was very angry. Her eyes were shining quite dangerously and her mouth, until she opened it, was a thin line. “Be quiet, children! Henrietta, give me that whistle. One more word from either of you and you go straight home. I never saw such an exhibition in all my life!”

The whistle was placed in Grandmother’s bag, which was snapped to with a resounding click, and everybody’s heads were lowered again. But Henrietta no longer felt good and the tears that trickled down behind her fingers were those of rage instead of sweet piety … How dared Hugh Anthony! … Little beast! … Just let him wait till they got outside and she would show him!

Hugh Anthony was not at all angry, for he was a firm believer in destiny. Things happened because they were ordained to happen. It was interesting to find out by what sequence of cause and effect they did happen, but useless to try to avert them. His whistle was gone and he was unlikely to see it again, but never mind; he would now be able to use on Henrietta, in punishment for her theft, a new booby-trap that he had recently invented but lacked opportunity to put into action. During the prayers and psalms he employed himself in working out a few minor touches that would perfect perfect its mechanism … By the time they got to the first lesson he had decided that when he grew up he was going to be an inventor.

The Dean’s high, nasal voice piped out from the lectern. “Let us now praise famous men, and our fathers that begat us … Such as found out musical tunes and recited verses in writing … All these were honoured in their generations, and were the glory of their times … And some there be, that have no memorial; who are perished, as though they had never been; and are become as though they had never been born … But these were merciful men, whose righteousness hath not been forgotten … Their bodies are buried in peace; but their name liveth for evermore.”

That penetrated Henrietta’s rage and she began to feel less wicked. She whispered the words to herself and they were so calming that by the time the final hymn was reached she had quite forgotten what it was she was going to do to Hugh Anthony when she got him outside.

This hymn was the climax of the service and lifted her up into the seventh heaven. The choir, followed by the whole congregation, sang it in procession, going all round the Cathedral and passing by all the decorated graves, leaving none of them out, so that everyone who had loved Torminster, alive or dead, was gathered together in one company.

“For all the saints who from their labours rest,

Who Thee by faith before the world confessed,

Thy name, O Jesu, be for ever blessed.

Alleluia!”

They were singing that verse as they passed Sir Despard Murgatroyd’s chantry, though he hardly deserved it, and Henrietta stood on tiptoe trying to see the dog with his wreath round his neck, but she could not.

“The golden evening brightens in the west:

Soon, soon to faithful warriors comes their rest;

Sweet is the calm of paradise the blest.

Alleluia!”

She did so hope her little dog was in Paradise, lying curled round in a ball in a bed of lilies, sleeping off the fatigue of following Sir Despard through purgatory.

They sang the end of the hymn standing in a group by the west door.

“From earth’s wide bounds, from ocean’s farthest coast,

Through gates of pearl streams in the countless host,

Singing to Father, Son and Holy Ghost.

Alleluia!”

Then they bowed their heads and the Bishop blessed them. “The peace of God which passeth all understanding keep your hearts and minds in the knowledge and love of God.” Then for a few moments there was silence, a deep, cool silence like the inside of a well … Peace … Henrietta was not quite sure what it was, but she knew it was very important. If one wanted it, Grandfather had told her once, one must not hit back when fate hit hard but must allow the hammer-strokes to batter out a hollow place inside one into which peace, like cool water, could flow.

The festival was over for another year and they drifted out through the west door on to the Green. It was dusk now, a smoky orange dusk that made the universe look like a lighted Chinese lantern swinging in space.

“I think I should like to go and help Uncle Jocelyn sell in the shop,” whispered Henrietta to Grandmother.

“Aren’t you coming to the Deanery tea-party?” whispered Hugh Anthony in astonishment. “There’ll be iced cakes, and cream in the tea.”

“I want to show Uncle Jocelyn my muff,” said Henrietta.

“Very well, dear,” said Grandmother, slightly relieved … One child alone at the Deanery party would probably behave itself, but with two together you never knew.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter VII — Part III

The Cathedral presented a scene of frantic activity, with all the canons’ female dependants scurrying about in overalls with scissors hanging from their waists. Not only had the lectern and the pulpit and the high altar to be flower-decked, as at other festivals, but every single tomb and memorial tablet in the Cathedral, no matter how humble and obscure, must have what Peppercue, the head verger, called its “floral tribute” before three o’clock that afternoon.

There was always a little difficulty as to who should decorate what, all the ladies having the lowest opinion of each other’s decorative powers. There was especial difficulty over the side chapel vases … If there is one thing in the world that every woman is quite sure no other woman but herself can do it is vases … The vases on the high altar were of course, as always, the duty of the wife or daughter of the Canon in residence (though goodness knew that poor Nell Roderick could no more make a dahlia stick upright than fly), but the side chapel vases were only filled on benefactors’ day and there was no real precedent as to who did them. Mrs. Elphinstone, as wife of the senior Canon, naturally thought she should, and Miss Roderick thought she should because she was doing the high altar vases and might as well do the lot together, and Mrs. Allenby thought she should because she had once been to the Scilly Isles and therefore must know more about flowers than anyone else, and no one knew why Mrs. Phillips, who was only the organist’s wife, thought she should … The Archdeacon had no female dependants.

It was at moments such as these that Grandfather came in useful. As he came smilingly up the aisle with his arms full of Japanese anemones it suddenly did not seem to matter very much who did what. For one thing his serene presence smoothed away all disagreement and for another thing he would be quite likely, with his fatal habit of thinking aloud, to repeat later at the Deanery tea-party, saying it over slowly and sadly to himself, any little remark that he had overheard and not liked … They all fell to on something or other and the side chapel vases were left to Mrs. Phillips.

Behind the high altar was the tomb of the patron saint of the Cathedral, a glorious canopy raised over a sculptured figure lying peacefully in his monk’s habit with his hands crossed on his breast and his eyes closed. It was a lovely piece of work, the luxuriant carving that had been hewn out of stone and raised over his bones for love of him contrasting touchingly with the simple figure … But alas, heavy doubts were entertained as to whether his bones were really there at all.

For he had lived in the Torminster valley as long ago as the age of miracles. He had been swineherd to a king whose name no one remembered but whose behaviour had been most distressing. So bad had he been that the whole land had groaned beneath his wickedness, the blue hills hiding their heads beneath the clouds for very shame, and the waters of the streams that ran down to the Torminster valley turning blood-red in horror. And the swineherd, who was a good man, was much upset. It was terrible, he thought, that this lovely valley, lying in the lap of these fair hills, should be so polluted, and one day while he sat beside the well where he watered his herd he earnestly prayed to God, as Grandfather would have done under similar circumstances, that he might be guided. And God in reply sent the Angel Gabriel down to the swineherd to talk the matter over and Gabriel said he thought the best thing to do would be to found a monastery, so that the radiance of the holy lives led by the monks might spread over the valley and conquer the darkness of its wickedness. That’s all very well, replied the swineherd, but where am I to find the holy monks? Gabriel made no verbal reply to this, but he picked up the stick that the swineherd carried and waved it over the backs of the pigs and over the well, and lo and behold, each pig became on the spot a holy monk while the well, that until now had been rather piggy and secular, became clear and holy, and the swineherd became the first Abbot of Torminster.

Helped by the holy angels, whose images are found carved everywhere in Torminster, he ruled long and wisely, living until the age of one hundred and ten and becoming holier and holier and sterner and sterner, for he was fully determined that never again should there be wickedness in the beautiful Torminster valley … And there never has been … To this day the inhabitants of Torminster are, on the whole and taking everything into consideration, exceptionally well-behaved, so well-behaved indeed that the disciplinary measure practised by the first Abbot, that of walling up alive indiscreet members of the community, has been discontinued.

But no one could ever be quite sure about the Abbot’s bones. After his death they took on extraordinary powers. Once a year his tomb was opened and they were displayed and people with whooping-cough who prayed beside them and touched them whooped no more, and other diseases were similarly benefited. This brought great credit upon the monastery and another monastery near by whose Abbot’s bones stayed put and did simply nothing at all was exceedingly jealous, and when there was a terrible fire at the Torminster monastery and vigilance was relaxed the miraculous bones mysteriously disappeared … And plague fell upon the neighbouring monastery … And a parcel of bones was mysteriously returned but, alas, they never cured the whooping-cough again, so were they the same bones?

The twentieth-century ladies of the Close did not know, but they gave them the benefit of the doubt and the Deanery hothouse plants.

Lady Lavinia Umphreville, the Dean’s wife, did not take any active part in the good work, for decorating tombs is a dusty business and she bought her clothes in Paris and knew what was due to them, but she always put in an appearance, walking very slowly and beautifully up the north choir aisle and down the south choir aisle and then out, bowing and smiling to the ladies of the Close as she went.

She arrived soon after Grandfather and the children, looking very exquisite in grey silk, with a pink ostrich feather in her hat and her grey hair beautifully done with the curling-tongs … She had a ladies’ maid and paid her, so Mrs. Allenby said, a fabulous sum, so no wonder she looked as she did. Mrs. Allenby would have looked the same, so she said, had Canon Allenby seen his way to providing her with a ladies’ maid too … Lady Lavinia had the willowy grace and dignity that so often go with aristocratic birth and her voice was low and gentle … though Henrietta had heard it said that the Dean was henpecked, but then Grandfather said one should not listen to gossip.

In Lady Lavinia’s wake followed the Deanery under-gardeners and the footman carrying the hothouse flowers, exotic things that seemed out of keeping with the memory of the simple man who had once kept swine in the valley.

Mrs. Elphinstone was not quite sure whether Grandfather and the children could be entrusted with any really important decorating, so she handed over to them an obscure chantry whose interior decorations could not be seen from outside. Its floor was covered with six flat tombstones whose lettering had been so worn away by the passing feet of the generations that it was impossible to make out the names of the dead whose dust lay under one’s feet. Though aware that he was being poked into a corner Grandfather was not in the least resentful, for he liked to feel that his flowers were honouring the unknown and this chantry was one of his favourite spots in the Cathedral.

The children loved it too, for it was like a fairy house carved out of an iceberg. You went up two steps, opened a door and there you were inside it. The walls and the ceiling were built of very white stone fretted into a hundred intricate shapes of flower and leaf and bird and demon, and so passionately had the sculptor enjoyed himself that he had taken as much trouble with the parts that did not show as the parts that did; you could put your finger round behind a grinning imp and find he had an unseen tail lashing away in the dark. And once upon a time the carving had all been coloured, for its whiteness was still stained here and there with patches of rose-pink and azure and lilac, as though the iceberg reflected a rainbow overhead.

The east end was entirely filled up by the huge tomb of the founder of the family in whose honour this chantry had been built. His sculptured likeness lay upon it, a colossal figure in armour with a huge plumed helmet on his head and a hound of no recognizable breed lying at his feet. His legs were crossed in token that he had been to the Crusades and his mailed hands were joined finger-tip to finger-tip as though in prayer … And looked a little awkward like that, as though it were a position not frequently adopted in life.

“Shall we give some flowers to Sir Despard Murgatroyd?” asked Henrietta. This was not really his name, but the children had once been taken to see a performance of Ruddigore and had been struck with the strong family likeness between the Bad Baronet and the gentleman in the chantry, whose grim face could just be seen below his raised vizor.

“Not too many,” said Grandfather. “I don’t think he’s the kind of man to appreciate flowers on his chest. But we’ll make wreaths to lay on the graves of these unknown descendants of his.”

“I bet you they’re his six wives,” said Hugh Anthony, “and I bet you he beat them. If he did a crime every day, like the Murgatroyds, I bet you he beat one every weekday and the dog on Sunday.”

“I don’t think they’re his wives,” said Henrietta, standing astride one of the tombs, “I think they’re six Saracens that he killed at the Crusades, and he had them pickled and brought them home to show that he’d really done it.”

“Then if they’re Saracens they’re not benefactors,” said Hugh Anthony, “and it’s waste of time decorating them.”

“That will do,” reproved Grandfather. “Put the flowers down there, please, Bates, and fetch us some jam-pots and water and then you can go home and see about those potatoes.”

Mrs. Elphinstone was quite wrong in thinking that Grandfather and the children could not decorate. Grandfather, of course, could not get down on the floor and actually do it because of his rheumatics, but he sat on one of the praying-chairs that stood in a row at the back of the chantry and was full of bright ideas which Henrietta and Hugh Anthony carried out with deft fingers.

The chantry looked lovely when they had done. Each wife, or Saracen, had a wreath of virginia-creeper and Japanese anemones, Sir Despard had a rose in his helmet and in all the niches in the walls they put pots of chrysanthemums. It was sad to think that both the rose and the wreaths on the floor would be dead by night, but the people in the tombs were dead too, and Grandfather assured them that death did not really matter at all, what mattered was that life while it lasted should be beautiful.

When they had finished decorating, and had cleared up the mess, Grandfather announced that they would now say a prayer for the repose of the souls of Sir Despard Murgatroyd and his relations. So they knelt in a row on the praying-chairs and Grandfather pleaded for Sir Despard, making use of the word Murgatroyd in his prayer in all innocence, for he had entirely forgotten how Sir Despard had originally come by it … “Give rest, O Christ, to Thy servants with Thy saints, where sorrow and pain are no more, neither sighing, but life everlasting,” he finished, and the children said “Amen.”

“And now we’ll go home to dinner,” said Grandfather, getting up from his rheumatic knees with a grimace of pain that was hastily repressed lest the children should see it.

“Roast beef,” said Hugh Anthony.

“I’ll stop a minute,” said Henrietta.

Grandfather nodded and left her, taking Hugh Anthony with him. There was something in Henrietta that he loved and respected, a power that she had of attuning herself to the things that are not seen. And it was because of this that he let her do things alone and go about by herself far more than Grandmother thought proper. He knew that she must discover by solitary experiment the way in which she herself could most easily learn to listen to the ditties of no tone that are piped to the spirit. She must learn to say, “Therefore, ye soft pipes, play on,” and know that they would obey her.

Left alone Henrietta dived about in the basket and found a long spray of virginia-creeper and three anemones. She twisted them together to form a collar and then, kneeling down in front of the dog who propped Sir Despard’s feet up, she slipped it round his neck.

She loved that dog, mongrel though he might be, and ugly into the bargain. The sculptor must have loved him too, for he had been carved so realistically that it was hard to realize his tail did not wag. Henrietta stroked his back, where the ribs stuck out under the skin as badly as Mixed Biscuits’ had before Jocelyn fed him up, and rubbed him behind the ears in the place where Mixed Biscuits liked to be rubbed and scratched his chest in the place where Mixed Biscuits liked to be scratched, and then she very gently kissed his nose.

Did dogs have immortal souls, she wondered? She had once asked Grandfather, but he had been distressingly vague about it. They might, he thought, or they might not. If it was a nice dog one could but hope.

Henrietta was sure this one had been a nice dog. After she had kissed his nose she knelt on with her eyes shut, thinking about him and his master. She doubted if Sir Despard had gone straight up to heaven to play a harp when he died … He did not look like that … He looked like one of those who went to a place called “the realms of darkness” and had a good deal done to them before they were suitable for harp playing. One of Grandfather’s prayers for the dead went like this—“King of majesty, deliver the souls of the departed from the pit of destruction that the grave devour them not; that they go not down to the realms of darkness: but let Michael, the holy standard bearer, make speed to restore them to the brightness of glory.” It was a prayer that suited Sir Despard very well, Henrietta thought. She could see him behind her closed lids, a dead man striding down long, black corridors, with his armour clanking and his feet kicking up a lot of dust, down and down into deepening darkness, with his dog at his heels … The dog was frightened by the dark and the dust and the silence of death and had his tail tucked in and his ears back, but he did not dream of leaving his master … And they tramped for hundreds of years until they came out into a great vaulted place like the crypt of the Cathedral and there Michael was waiting for them, with a sword in his hand and looking very grim, and he had a great deal to say to Sir Despard about his behaviour to the wives, or Saracens, before he could make him sorry for it, and a good deal to do to him before he could make him fit for heavenly society … And the poor dog had to sit in the corner and watch, trembling all over and whining, but not dreaming of running away … And then at last they went on again, Michael leading and Sir Despard following, feeling properly ashamed of himself, but this time they went up and up into deepening light, on and on for hundreds of years, so that the poor dog got terribly exhausted and his tongue hung out and his legs dragged. And so they came to the door of Paradise and Michael knocked on it with his sword and cried out, “Open! Bring the prisoner out of his prison house and he that sitteth in darkness out of the shadow of death!” And Saint Peter opened the door and Michael and Sir Despard went in … But the little dog, because he had no soul, was left crying outside and scratching at the door … Perhaps he was still there at this moment, after all these centuries, still trying to get in … Desperately Henrietta began to pray for him. “Give rest, O Christ, to Thy servant with Thy saints, where sorrow and pain are no more; neither sighing, but life everlasting.” And behind her closed eyelids she saw the door open a crack and heard Saint Peter say, “Come along in and don’t make that noise,” and the little dog ran in, his tail wagging, and disappeared in a blaze of light.

Henrietta opened her eyes and discovered that tears were running out of the far corners of them and making stiff wet tracks down her face in front of her ears. She wiped them away with the backs of her hands and giggled at herself, for during the last five minutes she had been living with that dog as intensely as it is possible to live … She had thought it was all real … It was odd, she thought, how that faculty that Grandfather said was called imagination could make one actually see and hear what was not really happening at all.

Yet surely that story she had imagined was a real thing? If you created a story with your mind surely it was just as much there as a piece of needlework that you created with your fingers? You could not see it with your bodily eyes, that was all. As she got up and dusted her knees Henrietta realized how the invisible world must be saturated with the stories that men tell both in their minds and by their lives. They must be everywhere, these stories, twisting together, penetrating existence like air breathed into the lungs, and how terrible, how awful, thought Henrietta, if the air breathed should be foul. How dare men live, how dare they think or imagine, when every action and every thought is a tiny thread to mar or enrich that tremendous tapestried story that man weaves on the loom that God has set up, a loom that stretches from heaven above to hell below and from side to side of the universe … It was all rather terrifying and Henrietta was glad to hurry home to lunch.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter VII — Part II

And so, by way of the archangels and the angels and the saints, they came to the humble benefactors, remembering them in the very middle of St. Martin’s summer … And St. Martin played up … But then, Henrietta thought, he would be sure to. That splendid young man who came dashing out of the town on a frosty winter’s night, with his scarlet cloak gleaming in the torchlight like a great dahlia and his horse’s hoofs striking sparks from the stones, was bound to be lavish in the way of weather. Just as he flung the rich folds of his cloak over the beggar who cowered by the roadside so, year after year, did he fling warm sunshine and a final largesse of autumn flowers over Torminster on its great day … A nice man.

And this year it was lovelier than ever. As soon as she woke up Henrietta scurried to the window to inspect the day. A sky of pale milky blue was tenderly arched over a world misted with silvery dew, and so frail and still and shining that it seemed like a blown soap bubble. Henrietta, leaning out of her window, was almost afraid to breathe lest it should break in spray against her face.

And after breakfast, as she helped Grandfather pick flowers in the garden for the Cathedral decorations, she was still afraid, for the flowers they picked were fragile as rainbows. There had been no cold weather yet and there were actually a few pink roses left, their petals transparent and faintly brown at the edges. The Japanese anemones, folded and hanging their heads after a touch of frost, were fairy lanterns of pearl and lilac that might at any moment vanish, and the scarlet leaves of the virginia-creeper fell at a touch like dead butterflies.

“They’ll all come to pieces when we put them on the graves,” mourned Henrietta, laying her spoils tenderly in the basket.

“Never mind,” said Grandfather, “the fallen petals are as precious in God’s sight as the dust of His dead.” He spoke sadly, for he was always depressed by the disintegration of autumn.

“Now, don’t be morbid, Theobald,” said Grandmother, issuing out of the front door in her goloshes. “And don’t stand about on that wet grass in those shoes. You’ve no more sense than a child of two … Here’s Bates with the chrysanthemums … Give them to Mrs. Elphinstone with my compliments, Theobald, and if she wants any more she can have them, but you must fetch them, mind. I won’t have her running about in my garden without a with-your-leave or a by-your-leave, wife of the senior Canon though she may be.”

Bates came out from behind the mulberry-tree with a huge bunch of yellow and red chrysanthemums and their colour and sturdiness, together with Grandmother’s strong-minded remarks, were somehow exhilarating in this dreamlike, vanishing autumn world.

They set off for the Cathedral, Grandfather and Henrietta and Hugh Anthony and Bates and the flowers. Grandmother did not come. She had been decorating churches for festivals for fifty years and had now come to the conclusion that she had had enough of it … Let other women take their turn at keeping the jam-pots from showing and mopping up the water that the clergy kicked over.

Grandfather and Henrietta walked on ahead, talking softly about the angels, and Hugh Anthony and Bates followed behind discussing horticulture.

“Bates, if I was to pour all the water over one plant in a flower-bed would it run along underneath the ground and make the others wet too?” asked Hugh Anthony.

“No, sir, it wouldn’t. If you was to ’ave a drink of beer it wouldn’t do me no good.”

“Bates, if you planted all the bulbs upside down would they come up in Australia?”

“I couldn’t say, sir. I ain’t never done such a thing.”

“Bates, why do peas grow in pods?”

“I couldn’t say, sir, I’m sure. Maybe they’re fond of a bit of company.”

“Bates, do you like radishes for tea?”

“I’m more partial to a kipper, sir. More tasty.”

“Bates, do you believe in God?”

“Yes, sir. I took religion when I started gardening. Wot I say is, ’oo put them peas in them pods and made them flowers so pretty and all?”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A City of Bells

Chapter VII — Part I

In November Torminster Cathedral commemorated its patron saint and benefactors. The Cathedral was great at festivals, each Christmas and Easter and Whitsun marching by in the procession of the days in flower-decked pomp, but in after years it seemed to Henrietta and Hugh Anthony that this particular festival surpassed all the others. It of course lacked the secular excitement of Christmas and Easter, for no one hung up stockings on it or ate pink boiled eggs for breakfast on it, but it had a peaceful and rather wistful beauty that was unforgettable.

It had been led up to by a season of remembrance. In September they had commemorated St. Michael and all the angels. In the Cathedral a great brass pot of Michelmas daisies had been placed under the window in the Lady Chapel that showed the good angels, looking very strong-minded and muscular, heaving the bad angels out of heaven on the end of pitchforks, and at home they had an iced cake for tea and while they ate it Grandfather told them how busy the angels were kept looking after little children. Henrietta felt that what with one thing and another the poor angels were very overworked, and she felt so grateful for their exertions that she made garlands of autumn flowers and hung them round the necks of the cherubs in her bedroom and the seraphim in the spare room.

And then had come All Saints’ Day, a lovely, wonderful day when the choir at evensong sang, “Who are these like stars appearing?” and the figures on the west front surely swelled a little to find themselves so appreciated. At bedtime that night Grandfather told them stories about the saints. They heard about St. Francis who loved birds and animals, St. Martin who shared his cloak with the beggar, St. Cecilia who loved music, St. Elizabeth who told such a shocking lie about the roses in her apron but was forgiven because she meant well, and St. Joan whom Grandfather loved best of all because when people laughed at her for saying she had been guided she took no notice whatever but just went straight on and did it.

Henrietta listened in a dreaming silence to these stories, utterly satisfied by their beauty, but Hugh Anthony was much exercised by the various points that they raised in his mind.

“When the saints die,” he asked Grandfather, “how long does it take their souls to get to heaven?”

“Ten minutes,” said Grandfather.

“How do they get there?”

“In the arms of their angels.”

“What do the angels do with the saints when they get them there?”

“Give them a thorough cleaning. It is, I believe, painful but very necessary. Dear me, yes. Not even the saints are perfect.”

“Are you a saint, Grandfather?”

“Dear me, no!”

“Why not?”

Grandfather replied in the words of Falstaff, “I have more flesh than another man and therefore more frailty.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means that I am stout and therefore inclined to be lazy. I can’t help being stout, but I ought to help being lazy and I fear I do not always do so. I go to sleep in the psalms.”

“Do saints never go to sleep in the psalms?”

“Dear me, no!”

Hugh Anthony returned to the point that was really worrying him more than he cared to admit. “Are you quite sure that it takes exactly ten minutes to get from earth to heaven?”

“I am absolutely certain,” replied Grandfather, meeting Hugh Anthony’s searching eyes with a keen, steady glance that brought conviction.

“Really, Theobald!” protested Grandmother, who was sitting by knitting and clicking her tongue in annoyance at Grandfather’s flights of fancy. “The things you say! One plain. One purl.”

But Grandfather was not penitent, for he believed with St. Elizabeth that there are times when a little inaccuracy is not only advisable but right. He was convinced that if a child with a naturally sceptical mind is ever to have faith there must never be any uncertainty about the answers given to his questions. He never said, “I don’t know,” or “I’m not sure,” to his grandson, though very occasionally, when completely floored, he replied to a question in the words used by the Angel Uriel when coping with the insatiable curiosity of the prophet Esdras. “Go thy way, weigh me the weight of the fire, or measure me the blast of the wind, or call me again the day that is past … Thou canst give me no answer … Thine own things, and such as are grown up with thee, canst thou not know; how should thy vessel then be able to comprehend the way of the most Highest?”

#torminstertravels#i am sorry about the break#but here wo go!#a city of bells#a city of bells: chapter 7

2 notes

·

View notes