Text

The town where the English and the French learned to like each other

As we drove home from Normandy my wife was unwell. I fell ill with covid myself back in London. By the time we realised that the virus had been rampant in France, it was too late to spoil our trip.

We'd stayed near Eu, at the northern tip of the Seine Maritime department. The name, incidentally, is supposed to sound like œufs (eggs), not like the past participle of the verb avoir. If you don't know the difference, never mind: the French are as confused as the English on how to pronounce Eu.

The town unites the two nations in many ways. Take its main church, the Collégiale Notre-Dame church (pictured above). A leaflet informed me that Lawrence O'Toole was buried here. Intrigued, I stepped inside.

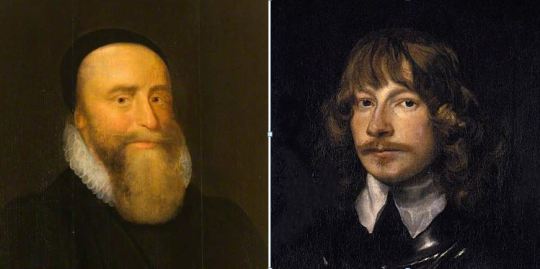

The O'Toole in question, it turned out, was not an English actor but an Irish saint. Spot the difference:

But it doesn't matter which illustrious O'Toole chose Eu as his final resting place.

One way or the other, it illustrates the fact that the town had been at the heart of cross-Channel relations for a millennium.

A stone near the collégiale commemorates the wedding between Guillaume, a local warlord, and a woman called Mathilde, in the 11th century. The groom went on to conquer England.

That conquest led to a reverse land-grad: Normandy fell to the English crown. Over the centuries other French provinces were gobbled up by England, until locals had had enough.

You can think of the Hundred Years' War as a football game. The French scored early. The visitors fought back and were set for victory when the French boss brought on an untried teenager. The substitution boosted morale no end: the youngster didn't finish the game, but the home side won.

Eu's role in the Joan of Arc saga is commemorated by another plaque. Following her capture, the pucelle spent a night at the castle here, on her way to Rouen where she was burned at the stake on charges of heresy, witchcraft and cross-dressing.

But soon religious strife threatened to reignite conflict between England and France.

Eu became a flashpoint once again. The Duc de Guise, the leaflet said, settled there. I remembered from my school days that he was a Catholic fanatic. But he hailed from eastern France and Protestants were big in the south. Why come to Normandy?

Eu's castle houses a history museum: maybe I would find the answer there. A bearded man standing outside the splendid Renaissance building told us it was closed for winter. He knew because he was the curator.

Figuring he didn't have much to do, I questioned him. I drew near to make sure I heard correctly. If he was the one who gave me covid, it was worth it. He passed on knowledge as well.

In 1570, the bearded man said, the duke married the Countess of Eu. He used her castle as a base to hound Huguenots across Normandy and nearby Picardy, and to foment Catholic unrest in Britain.

The French king, Henri III, was as Catholic as the next guy. But his main concern was peace. In the late 1580s, when he heard that the duke was plotting to kill Elizabeth I, Henri blew a fuse.

"Does he want another Hundred Years' War? How many massacres are enough for him?"

"What he wants, Sire, is his cousin Mary - formerly Queen of Scots - on the throne in England and himself on yours."

"Get me rid of the felonious scumbag!"

The assassination of de Guise on royal orders unleashed France's umpteenth war of religion. The childless king was in turn murdered by a Catholic radical. The killing backfired: next in line was a Protestant. That successor fostered tolerance but he too was taken out by a nutter.

By the early seventeenth century, France was exhausted. A peace of sorts prevailed. But that didn't stop many Catholics regarding the Duc de Guise as a martyr. In Eu, his widow built a shrine to him.

The Chapelle du Collège des Jésuites, completed in 1624, is one of Normandy's hidden gems - religious zealots, I've noted, often have good taste.

It contains marble mausoleums to the duke and his wife. Both are shown in odd, recumbent poses.

The statue of the countess is particularly striking: she's fallen asleep while reading a book.

Eu remained the stronghold of the Guises, France's most Anglophobic clan, until 1660, when it was taken over by the House of Orléans, who were fans of all things British.

Meanwhile, Paris went the other way. Albion became the arch-enemy once again. It remained so for 170 years. The problem this time was not that the English claimed French land, but that they wouldn't let France (as a monarchy, republic or empire) grab foreign land.

In 1830 something miraculous happened: the Orléans somehow ascended the throne. For the first time in French history, true Anglophiles were in charge.

Relations didn't improve overnight. British elites remained deeply Gallosceptic. In 1840, the French king, Louis-Philippe, redoubled efforts to mend fences: he named François Guizot, an ardent liberal and former ambassador to London, as his foreign minister.

Despite Guizot's record as Britain-booster the English weren't sure the French had changed their spots.

"Those rosbifs are infuriating," Louis-Philippe eventually told Guizot. "I set up a constitutional monarchy, I promote peaceful commerce, I don't bang on about the glory of France. And they still treat me as if I'm about to invade the Palatinate."

"For all they know you are, sire," Guizot said. "They've been burned before."

The minister had a plan. No English monarch had visited France since Henry VIII. Britain had a young new queen: why not invite her?

And what better venue for a reset than the king's summer residence at Eu? There, Guizot said grandiloquently, "the ghosts of William, Joan and the Guises can be summoned and banished."

Victoria was 24 and Louis-Philippe pushing 70 when they met in 1843. Despite the age gap, the two hit it off.

The first Entente Cordiale was not a formal treaty, unlike its 1904 sequel. It boiled down to regular contacts between Guizot and Lord Aberdeen. "We basically want the same things, so we can tell each other everything," Guizot wrote to his counterpart and friend.

Their successors were not always on such warm terms. But a habit had been formed. France and Britain have been allies ever since. It all began in Eu.

Such historic significance is not the only reason to visit the town. Its streets are lined with magnificent 17th and 18th century buildings - some are pictured at the end of the post.

The one that struck us most was the Hotel Dieu (above). It was built with a bequest from the widow of Duc de Guise as a hospital for the poor - religious zealots, I've noted, often have a caring side.

A plaque says that at this spot, on 17 July 1636, the mayor commissioned "an image carved in silver showing of the Virgin Mary carrying the town of Eu" to ward off the plague.

The sign does not say whether this approach to a health emergency worked better than anti-covid measures four centuries later.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les marais de la Bresle (a marshland walk)

(A warning: although this is an English-language blog, the text that follows is in French. The reason is not that it tells of an outing in Normandy. I chose to use my native language because I discovered both a landscape and the vocabulary associated with it. An average Parisian, I knew nothing about wildlife. I found the explanations provided throughout this wetlands circuit as magical as the things they described. To non French-speaking readers, I suggest trying Google Translate: it may add some magic of its own.)

Je ne suis pas ce que les Anglais appellent un birdwatcher. Je ne vois pas la différence entre un rouge-gorge et un rossignol, ni l'intérêt de la savoir. Je considère les piafs comme des nuisances sonores.

Ce n'est pas l'ornithophilie qui nous a poussés, mon épouse Lesley et moi, vers la vallée marécageuse de la Bresle: iI fallait simplement balader notre chien.

Nous séjournions au Tréport. J'avais repéré sur une carte un chemin en dur de long de la rivière: cela semblait parfait pour laisser gambader Gamma sans se couvrir de boue nous-mêmes.

On accédait à ce chemin par le bassin portuaire: entrepôts, bateaux, et au loin une usine de traitement des eaux. Sur le mur d'un hangar, des affiches vitupéraient la "dictature des éoliennes" qui tue la pêche marine.

Passée cette zone glauque, une pancarte marque notre entrée dans un "lieu d'accueil pour les oiseaux migrateurs".

La nouvelle est a priori mauvaise: les animaux domestiques sont généralement bannis de ce genre de sanctuaires. Mais, encouragés par la présence d'autres promeneurs de chiens, nous poursuivons.

Gamma batifole entre les brins d'herbe empreints des urines capiteuses de ses congénères. Nous sommes à pied sec. Tout le monde est content.

Je me mets à trouver l'endroit franchement sympathique en découvrant le mot "roselière". Rien à voir avec les fleurs: il s'agit d'un endroit où poussent les roseaux.

Le panneau explicatif achève de me mettre en joie:

"L'ordre des passereaux regroupe le tiers des oiseaux français. Ils sont couramment caractérisés par leur capacité vocale exceptionnelle, leur petite taille et un mode de vie arboricole. Certaines espèces sont liées aux roselières bordant les étendues d'eau pour l'habitat de reproduction et d'alimentation. On y retrouve notamment la Gorgebleue à miroir, le Phragmite des joncs ou encore la Bouscarle de Cetti."

Ce milieu abrite en outre le "râle d'eau" et le "grèbe castagneux". Il s'avère que ce dernier, "étant très territorial, ne niche pas en grande colonie". Je suppose qu'il doit son surnom à sa nature ombrageuse.

Ce qui frappe le plus en remontant la vallée de la Bresle, c'est le respect des hommes pour la plaine inondable.

Des deux côtés de la rive, les routes et les constructions se sont écartées du cours de la rivière.

Le chemin cyclo-pédestre qui se faufile entre la rive, les étangs et les pâtures détrempées constitue le seul apport bitumineux.

En trois quart d'heures nous parvenons à Eu, cité historique que j'évoquerai dans un billet prochain. Nous y retrouvons ma sœur Valérie et sa chienne, venues de Paris pour se joindre à la randonnée.

Sur un étang un couple de cygne prend langoureusement son essor. Selon une brochure ramassée au syndicat d'initiative d'Eu, le marais est prisé des "oiseaux paléarctiques migrateurs car il se situe à mi-chemin entre l'Oural (zone de reproduction) et le Sahara (zone d'hivernage)".

J'imagine que ces cygnes, partis de Sibérie aux premiers froids, ont mis un point d'honneur à faire escale au Tréport et viennent de s'envoler pour Tombouctou.

Mais non: au bout de trois minutes ils sont de retour. Ils sont bien dans cette mare.

La fascination qu'ils m'inspirent ne semble pas réciproque. La femelle reste en retrait; le mâle témoigne son sentiment à mon égard en me montrant son cul.

Seule ombre au tableau: les chasseurs dont la présence dans les hauteurs environnantes se manifeste par des détonations intempestives.

La chienne de Valérie est prise d'un affolement que la surdité de l'âge épargne à Gamma.

Sur le bord du chemin, des panneaux mettaient en garde promeneurs et cyclistes: "En période de chasse soyez prudent." En France, six mois dans l'année, les chasseurs ont la haute main sur la nature: c'est au public de faire attention.

Nous avons fait une halte sur une aire aménagée au bord de l'eau, avant de gagner Incheville par un chemin compliqué par une pénurie de ponts.

J'avais prépositionné notre automobile dans cette localité. C'était heureux car il commençait à pleuvoir.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

North Sea Scotland (12): Aberdeen's winners and sinners

My last post enthused about the granite extravaganza that Aberdeen became in the 19th century.

But there is much more to the city than grey Victorian buildings.

The speckled hulk of St Machar Cathedral, 3km north of the city centre, combines every material its medieval builders could lay their hands on: rough blocks of dark granite, red sandstone and even pebbles from the river.

Machar was an Irish monk who evangelised the Picts.

A stone in the cathedral featuring a Pictish cross is said to come from a church he built around 600.

The current one went up between 1380 and 1520.

Its star attraction is a "heraldic ceiling" with shields representing European kings - including Scotland's – and the Pope. It was a sign of clerical loyalty at a time when, over in Germany, Martin Luther demonised Rome.

In due course the Protestants had their revenge and left their mark on the building.

Note the naked walls. Initially, they would have been plastered and covered with biblical pictures. But after the 1560 Reformation the decorations were painted over.

In 1495 a bishop founded King's College, just south of the cathedral. This led to the development of Old Aberdeen.

The houses along the High Street mostly date from 18th and early 19th century.

The rough stones and cobbled streets give the area a quaintness that contrasts with the Victorian city centre a mile or two away.

A five-minute walk down the High Street is the university.

The original halls are long gone, but the 16th-century chapel with its funky crown tower is still standing.

In the picture below, it's to the left of the main college building, a 19th-century job.

The most strikingly medieval-looking venue, Elphinstone Hall (below), was actually built in 1931.

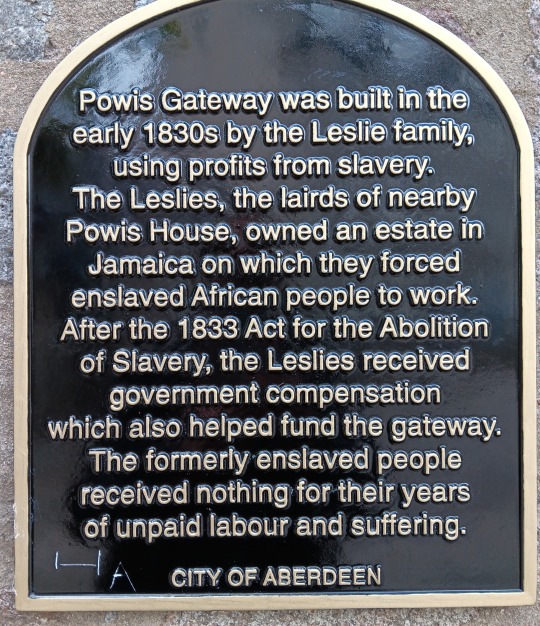

Another campus curiosity is the 1834 Powis Gateway.

Topped by Turkish-style minarets, it stands on land that used to be the property of the Leslies of Powis, a local family.

Lamentably, this orientalist relic is among the most "instagrammable" landmarks in Aberdeen, so taking it down may take time.

Meanwhile a plaque makes it clear that the Leslies were bastards.

The Leslies' problem is that they lived in the wrong part of town.

They wouldn't have stood out much in New Aberdeen, further south. That burgh was created in the late Middle Ages to accommodate the rising merchant class. It has busy markets, port facilities and no student body to denounce colonial sins.

Of course, living away from campus and diocese did not automatically protect businessmen from religious or political tumult.

The oldest surviving building in New Aberdeen is Provost Skene's House. It dates from 1545 and is named after a 17th-century trader who served as provost (i.e. mayor).

The most interesting occupants were Matthew Lumsden and his wife Elisabeth. After buying the house in 1622 they built a secret prayer room in the eaves: like many Catholics in Presbyterian Scotland, they were able to practise their faith quietly.

In the run-up to the British Civil Wars the couple joined Scotland's hard-line Protestant majority. Matthew even enlisted in a "Covenanter" militia and was killed in the Catholic-Royalist offensive of 1644. Elizabeth died three years later.

A century on, Provost Skene's House was caught up in a failed rebellion against the Hanoverian regime. The owners were no Jacobite hotheads, but the royal commander seized their property and treated it with all the care of a teenager in her parents' empty home.

The jinxed house fell into disrepair and eventually became a hostel for the homeless. It is now a museum celebrating eminent Aberdonians. The only one I'd heard of was Annie Lennox, a pop star.

The second-oldest dwelling in Aberdeen is Provost Ross's House, built in 1593.

Note the coarse, brown-red granite that contrasts with the smooth grey surfaces of the mature granite age featured in my earlier post.

Ross, another merchant turned mayor, lived there in the early 18th century.

The building is now home to a maritime museum that highlights Aberdeen's booms and busts from the hanseatic trade to offshore drilling.

The city's first oil industry, Arctic whaling, thrived in the 18th century. The modern harbour was built in the 1770s to handle big ships and their blubbery cargo.

By the early 1830s North Atlantic whales had been hunted almost to extinction. A few years later Captain Ahab, a fictional but realistic seaman from Massachusetts, found only one whale during a three-year voyage. That really got to him.

In the 19th century Aberdeen turned to fishing and shipbuilding. Both later declined but oil and gas took off in the 1970s.

Hopefully something else will turn up after the offshore fields run out in the next decade or two.

No trip to Aberdeen is complete without a visit to Footdee (or, as it is pronounced, "Fittie").

The village was built in the 1820s to house fishermen and their families as the harbour expanded.

Wedged between river and sea, its alleyways lined with bohemian cottages and colourful outbuildings exude community spirit.

0 notes

Text

Aberdeen's shades of grey (North Sea Scotland 11)

I was ready to believe that Aberdeen was actually a nice place.

Its image as a battleground between welfare claimants and tax-dodging oilmen, I suspected, was unfair.

But I was not prepared for what I found: one of Europe's most stunning cities.

Admittedly, Aberdeen is very grey. That's because it is made of the local stone - hence its nickname, the "granite city".

The main drag, Union Street (pictured above), was laid out in the early 19th century to allow the city to grow from its medieval centre.

Before then, granite was too hard to be much use for construction. But from the early 1800s, steam-powered machines made it increasingly easier to cut and polish. The granite age had arrived.

Eventually Union Street sprouted buildings like this:

The Town House (i.e. city hall) was designed in the late 1860s. Note the smooth, shiny surfaces, like a hybrid between satin and concrete, which are characteristic of the mature granite age.

Next door is another neo-Gothic gem: an 1892 building that was once hosted the Esslemont & Mackintosh department store:

The Salvation Army Citadel terminates the eastward perspective vista from Union Street in style.

This glorified food bank/church takes 1890s Gothic revival to Disneyesque heights:

Facing the citadel is the Archibald Simpson pub, named after Aberdeen's greatest-ever architect.

Archibald Simpson designed many of Aberdeen's landmarks, including this one in 1840 (as a bank):

The most monumental erection in the area is Marischal College:

Located just off Union Street, the college is the second biggest granite building in the world, after the Escorial in Madrid.

It's actually two buildings in one. The facade (above) was built in the 1890 in the "perpendicular gothic" style.

But step inside and you'll find Archibald's Simpson’s pared-down Elizabethan quadrangle (1837):

Simpson's building is made from rough granite from the nearby Rubislaw quarry. A harder, white stone was used for the later, mock-medieval exterior.

John Betjeman, an architecturally inclined English poet, described Marischal College thus in a 1947 radio talk : "Bigger than any cathedral, tower on tower, forests of pinnacles, a group of palatial buildings rivalled only by the Houses of Parliament at Westminster."

The college is owned by the University of Aberdeen, but is now leased by the Aberdeen city council. Near the entrance stands a statue of King Robert the Bruce.

The sculpture looks older than it is. Unveiled in 2011, it represents the Bruce in equestrian splendour, holding aloft a 1319 charter that helped Aberdeen become a medieval powerhouse.

But in my view the best Aberdonian architecture avoids bombast and hero worship. It lets granite ennoble the mundane.

Further down Union Street are the old offices of the Northern Assurance Company:

It dates from 1885 and – appropriately for a building designed for commercial use – is now a Thai restaurant.

For elegance, simplicity and boldness no one beats Archibald Simpson. He built these homes on Bon-Accord Crescent in the 1820s.

In 1975, Aberdeen decided to honour the man who did more than anyone to shape the city.

It did so in an exquisite way: the Archibald Simpson memorial is not a corny statue, but a block of granite in the middle of a square he designed.

There is more to Aberdeen than granite and I will post about other aspects of this magnificent city.

In the meantime, here are a few more highlights from the council's excellent granite trail leaflet:

In the early 1900s they knew how to build post offices. The one above is now just a block of flats.

Aberdeen's granite has served various styles, from classical to neo-Gothic and modernist.

The 1930s Bon Accord Baths (above) are clearly Art Deco. They closed in 2008 and were turned into a gym.

The elegant homes on Rubislaw Terrace were built in the early 1850s.

Queen's Cross, a villa built in 1865, was the swish home of George Washington Wilson, a pioneering Scottish photographer:

Wilson was a fan of granite. When foundations for a church were laid 50 yards away, he offered to pay for it to be made of that stone. But it was too late: sandstone had been ordered.

Wilson was furious. When he learned that another church was to go up across the street, he bought rights to the spot make sure it was made of granite.

When describing New Cross Church to his radio audiences, Betjeman, for once, was at a loss for words.

"I never saw such a thing," he said. "I cannot describe its style or changing shapes as it descends in lengthening stages of silver-grey granite from the pale blue sky to the solid prosperity of its leafy suburban setting."

Unlike Betjeman, I can let you judge for yourself:

0 notes

Text

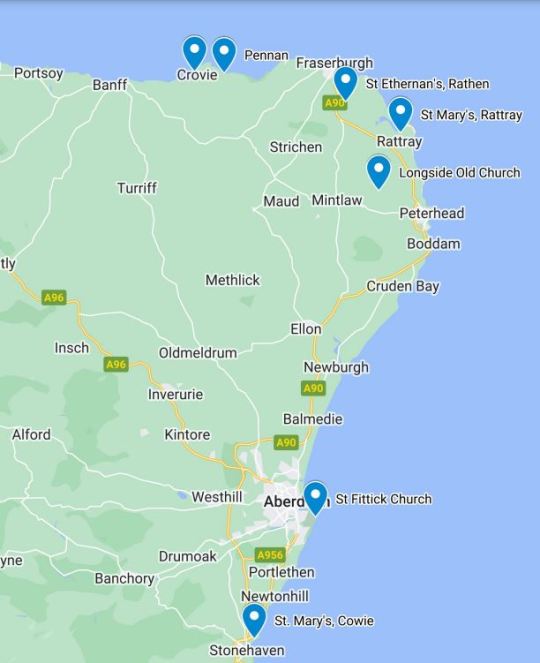

Graveyards by the sea

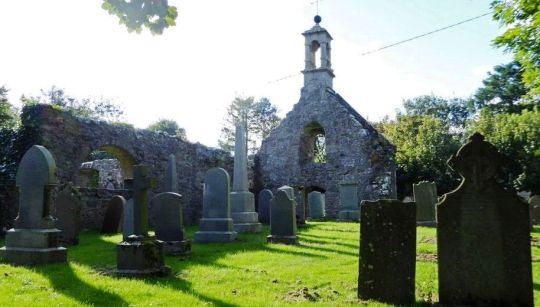

Abandoned churches dotted along the Aberdeenshire coast give it a pleasingly godforsaken feel.

The regional council has put out a guide to 12 of the best such ruins. Here is my short list, from south to north (map at the end of this post.)

The remains of St Mary's Church, in Cowie - pictured above and below - sit oddly between a golf course and cliffs overlooking Stonehaven Bay.

The 13th-century chapel was dedicated to "St Mary of the Storms" but fell into disuse in the 1560s. Perhaps the newly Protestant kirk objected to involving the Holy Virgin in maritime meteorology. A panel at the site only says that the church "was unroofed by the ecclesiastical authority on account of certain scandals".

Locals recycled the crumbling walls as building material, despite a rumour that the stones would "rain blood upon any house built with them".

There was an attempt to rebuild the chapel in the 19th century. The churchyard includes a memorial to a Stonehaven lifeboat crew who perished in a failed rescue in 1874. Far from bringing succour to seamen, it seems, the site was jinxed. Parishioners deserted it.

The adjacent golf clubhouse, on the other hand, is doing brisk business.

Twenty kilometres to the north is another former church in an incongruous setting. The ruins of St Fittick's Church stand next to the south shore of Aberdeen harbour.

The 12th-century chapel was named after an Irish monk who set out to evangelise the Picts in the 600s. According to legend, Fittick's boat was caught in a storm. He told the sailors that salvation lay in Christ. They threw him overboard to placate Manannán mac Lir, the god of the sea.

But the holy man had the last laugh. He managed to swim to the shore. When the villagers asked him how he had survived the wrath of Manannán mac Lir, Fittick said: "Salvation lies in belief in Christ."

The church testifies to the complex relationship between Scots and their fellow Celts across the Irish Sea.

The kirkyard features the gravestone of one William Milne, a victim of Britain's civil wars of the 17th century (my post about the Scottish part of that conflict is here).

Milne, a farmer, joined a Protestant "Covenanter" militia during a royalist offensive backed by Irish Catholics. The Latin epitaph says that he fell in 1645"for the cause of Christ... by the sword of a savage Irishman".

Fifty kilometres up the coast is Longside Old Parish Church, built in 1619-20.

The churchyard features many memento mori symbols: skulls and bones, hourglasses and the like.

My favourite gravestone is that of William Reid, who "depairted this life" in 1702 and "rests in hops of blesed resurection". I quote this not to mock the spelling, but my own obsession with spelling.

Soon I will be gone, as will the linguistic proprieties I held so dear. For a pedant, this stone is the most poignant memento mori of all.

St Mary Chapel, Rattray, is another monument to transience.

Rising from flatlands that seem to merge into the sea, it is all that remains of the "royal burgh" of Rattray.

That status was granted by Mary Queen of Scots to encourage local clans to engage in commerce rather than feuds. Thus Rattray gained the right to hold markets and trade far and wide.

The sea had other ideas. Winds and currents filled the harbour with sand over the years. By the 1800s the village had vanished, as if engulfed by the soggy ground.

But the shell of the 13th-century chapel still stands, at the end of a single lane that seems to lead nowhere.

A few kilometres inland, on the outskirts of Fraserburgh, is St Ethernan's, Rathen.

A front gable and a side wall are all that's left of this 17th-century parish church.

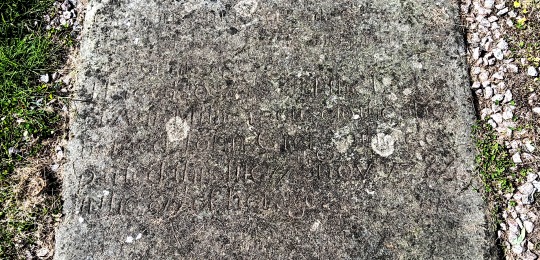

The stars of the kirkyard are John Greig and Anne Milne, a couple of tenant farmers who happened to be the great-great-grandparents of Norwegian composer Edvard Greig.

One of their sons emigrated and became a successful merchant in Bergen.

Three generations later, little Edvard learned how to play the piano and the rest is musical history.

The inscription on the gravestone is quite worn but someone deciphered it: "Here lyes the remains of JOHN GRIEG, late tenant in Mostoun of Cairnbulg d 6 Jan 1774 in his 71st year. Here also was laid the body of ANN MILNE, spouse of above named John Greig d 17 Nov 1784 in 81st year. This stone is erected to his memory by his surviving children."

The survivors refrained from mentioning the couple's connection to an illustrious descendant. Another lesson in humility!

Fraserburgh is home to an informative Museum of Scottish Lighthouses. Those uninterested in nautical beacons can happily skip that town and follow the coastline to the west.

The highlights of the northern Aberdeenshire seaboard are fishing villages that are little more than strip of cottages between water and cliff.

They look cute now but were born of desperation. Farm labourers settled these unpromising shores in the 18th century, after being evicted in the Highland Clearances.

One of the most picturesque of those villages is Crovie (above). There is not even room for a road either in front or behind the cottages.

The most famous is Pennan, which was put on the map by Bill Forsyth's film Local Hero.

Its phone box plays a big part in the movie - made in the dark, pre-mobile ages.

Forty years on, the red kiosk is still there.

The Aberdeenshire council has apparently kept it in service as a tourist attraction.

Talking about maps, here's the one I promised (forgive its crudeness: the only cartographical tool my incompetence can handle is Google My Map.)

1 note

·

View note

Text

North Sea Scotland (9): Three castles

Scotland doesn't lack for castles. The challenge for the tourist is not just to tell them apart but to remember them apart.

There's a reason why they blend into one crenulated blur. It's the same story everywhere: a man who fought alongside Robert the Bruce was rewarded with land; his son built a fortress; a great-grandson extended it.

Making my way through the castles of Aberdeenshire, I found an antidote to this déjà-vu feeling: focus on one historical period and consider how each place experienced it. A narrow angle allows you to see individual fates that are lost if you take the long view.

I chose to zero in on the mid-17th century, a very dangerous time for Scottish aristocrats. The traditional sources of discord (clan feuds, the Highlands/Lowlands cultural split, links with England, etc.) combined with religious tensions in a particularly noxious mix.

I'd learned about the launch of the Scottish Reformation while visiting Perth. In Aberdeenshire, I had to brush up on what happened next. Here's a summary.

Scotland ditched Catholicism in 1560, well after England. Of course, it had to do it differently. For one thing, Scottish Presbyterians were much more austere than Anglicans: big on sermons, short on music, etc. And crucially the head of their "Kirk" was not a temporal monarch, but Christ himself.

Thus Scotland's fire-and-brimstone preachers accepted the Catholic Queen they had inherited: she was irrelevant.

This split between Church and Crown took the sting out of religious differences. Without a state to enforce confessional uniformity, swathes of Scotland, mostly in the Highlands, quietly continued to follow Catholic rites. Calvinist Presbyterians and Papists rubbed along.

Everything changed when the Stuarts acceded to the English throne in 1603. Although the Stuarts were Scottish, the move was bad news for their native country.

The Stuarts now reigned over two separate kingdoms (with Ireland thrown in as a bonus). In one, they were ecclesiastic supremos; in the other, they remained ordinary parishioners. They thought: "It's about time we Scots learned how to run a Church properly."

The first Anglicised Stuart, James (confusingly, he had different regnal numbers on either side of the border), was persuaded to go slow on interfering with the Kirk. He just foisted token bishops on it. The country's religious peace was tested but not broken.

His son was known as Charles I both in Scotland and England. That's the extent of his contribution to harmony between his realms.

Charles was a man of principles. Half-measures were pointless. In 1637, he decided that the Scots would just have to swallow an Anglican Kirk, music and all. Crypto-Catholics were happy but the Presbyterian majority was not. Riots erupted. Presbyterians raised armies. Loyalists did likewise.

Scotland's "Bishop War" of 1639-40 kick started conflicts that engulfed the British Isles for 20 years. In England, the fighting was as much about politics as it was about religion: Parliament objected to Charles's belief in a God-given mandate to rule without consulting anyone.

In the 1640s the Scots were sucked into that civil war. Presbyterians naturally backed the Parliamentarian camp; which was dominated by Protestant hardliners; others stuck with Charles.

Interwoven wars were fought on both sides of the border by a head-spinning succession of shifting alliances. Some Scottish aristocrats proved better at playing this game than others.

Below is a look at the fates of three family estates near Aberdeen. I suppose that similar stories of defiant resistance, opportunistic guile and self-destructive zeal can be found across Scotland.

CRATHES CASTLE

This 16th-century erection, 20 miles west of Aberdeen, is the seat of the Burnetts of Leys. The interesting one is Sir Thomas Burnett, 1st Baronet of Leys (1580s-1653).

He was a leader of the "Covenanters", who opposed Charles's bid to turn the Kirk into an Anglican affiliate. But not everyone was all that bothered. When Burnett went to Aberdeen to raise funds for a Covenanter army in 1638, city magistrates told him to stop agitating against the king.

Sir Thomas informed a Covenanter friend, the earl of Montrose, that Aberdeen was a nest of loyalists. Montrose said: "Leave it with me." He entered Aberdeen with 3,000 men: it's amazing how an army can focus minds.

Burnett found Aberdonians much more receptive to his crowdfunding appeal. Invited to donate to the Covenant or have their property confiscated, locals gave generously to the cause.

Fast forward to 1644: Covenanters are firmly in control. Burnett still supports them but he's pushing 60 and has taken a back seat. In fact, he's a bit miffed that he has received no compensation for the money he lost hosting troops at Crathes Castle.

Montrose, meanwhile, has had a radical change of mind. A rival is in charge of the Covenanter movement. As he sees it, it has become an extortion racket. So the earl has turned coat and is leading a royalist offensive in Scotland, with support from Irish Catholics.

After storming several Covenanter estates, he gets to Crathes. His second in command tells him: "This castle belongs to that traitor Burnett. Let's ransack it." Montrose says: "Leave it with me."

He gets off his horse and knocks on the door. Burnett invites his old friend in.

Over dinner, the ageing baronet explains that he's no longer involved with the government – which actually owes him 100,000 merks for quartering soldiers all those years ago.

"They also forced me to melt down the family silver to lend money to the Treasury," Burnett sighs.

"Greedy bastards," Montrose snorts.

At the end of the meal, Burnett offers his guest weapons and horses, as well as 5,000 merks. "Thanks for the guns and the nags," Montrose says. "But keep your money. We're not greedy bastards."

Burnett and his family were the only Covenanters protected by Montrose.

The earl was eventually defeated by the Scottish government. He was executed in 1650, aged 37. Burnett was quizzed by Parliament and said he'd given a fortune to the Covenanters, but not a merk to their enemies. It's unclear whether he got any compensation but he and his castle were safe.

DRUM CASTLE

Drum Castle, down the road from Crathes, tells a very different story.

It was the seat of Clan Irvine. The ninth laird of Drum (1566-1631) was a smart operator. He was as Calvinist as the next Scot, but he didn't make a fuss over James' bishops.

He even lent money to that profligate king and, in return, he got dispensation to eat meat on Fridays.

His son the 10th laird, Alexander, stuck his neck out at a time when doing so was risky. He was an ardent royalist living deep in Covenanter country. Drum castle became a prime target.

Government troops looted it four times. Alexander owed his life to the fact that he did not put up any resistance.

The two sons joined Montrose's royalist/Catholic army. When they were obliterated in 1645, both young Irvines were captured. One, who had been a fierce fighter, was elaborately killed. The other, who had taken part in minor clashes, managed to escape.

The 1660 restoration should have been a good time for that surviving son, another Alexander. The Stuarts, for whom his family had hazarded their lives and property, were back on the throne. The Kirk was Anglicized. Protestant hard-liners were hunted down.

The new king, Charles II, was keen to reward those who had remained loyal throughout the wars. Alex requested an audience. His friends were not especially hopeful that Charles would respond. The Irvines were only minor aristocrats from the Lowlands.

But the king knew that his gratitude would get a favourable press precisely because of the obscurity of the recipients. Two weeks later, Alex was received at Hampton Court Palace.

"Thanks for coming from so far away," the king said. "I've decided to make you a peer."

"That's big of you my Lord," Alex said. "But our crops have been ruined, all our animals are dead, our jewellery and furniture are gone, generations of heirlooms have been burnt or stolen. Our castle has been gutted – because we stuck by YOU."

"I've heard about the hardship the Irvines has endured. It's precisely in recognition of this sacrifice that I want to make an example and elevate you and your issue to the highest..."

"My brother was tortured to death. My father died of a broken heart in a country occupied by Cromwell. I want full compensation for our huge losses. We can talk about the peerage later."

Charles did not say: "I've got better things to do than haggle with a bumpkin from the glens." The king said nothing. The audience was over.

DUNNOTTAR CASTLE

Overlooking a spectacular stretch of coast south of Aberdeen, Dunnottar Castle is one of the most recognisable landmarks in Britain (recognisable to the eye, but maybe not to the ear: the name doesn't rhyme with "Pat Benatar" but with "an otter").

It is the historic seat of the Keiths, who gloried in the title of Earl Marischal. They were firm Covenanters and helped Montrose (Mk 1) in his campaigns against loyalists in Aberdeen and the Highlands.

But when Montrose (Mk 2) returned to Donnottar with a royalist army in 1645, the earl did not invite him for dinner. He dug in.

Unable to storm the fortress, Montrose torched nearby villages. As Keith watched the smoke rise from his smouldering barony, his Puritan preacher reassured him that "the reek will be a sweet-smelling savour in the nostrils of the Lord".

Meanwhile, in England, the Parliamentarians were crushing the royalists. This led to the mother of all alliance shifts. The Roundheads no longer needed the Scots. Cromwell never really liked them anyway. His army was full of radicals who opposed any organised religion: Calvinism was not their thing.

The Covenanters, for their part, were appalled by the hodgepodge of sects proliferating in revolutionary England. Many suspected that a diminished Charles might be preferable to a hothead like Cromwell.

When Charles was executed in 1649, there was rising Scottish support for his heir. A year later, Charles II signed off on the principle of a Presbyterian monarchy - it was just PR: he knew he was in for a long spell in exile. The Edinburgh Parliament declared him king.

The Covenanters were now full-blown royalists. Cromwell, not for the first time, attacked Scotland.

This brings us back to Dunnottar: as Earl Marischal, Keith had a duty to protect Scotland's Crown Jewels.

They had been taken to the castle after Charles's hasty coronation (he skipped the country shortly afterwards).

The invaders laid siege to Dunnottar for nine months. By the time its defenders surrendered, in 1652, the national bling had been safely removed. The furious Roundheads ransacked the castle.

Over the years, it had been attacked by Scots and Englishmen, by Catholic and Protestants.

Dunnottar is a monument to neither cautious ambivalence nor self-destructive loyalty. It stands for something rarer: the principled U-turn.

0 notes

Text

North Sea Scotland (8): A legacy in ruins

Arbroath Abbey, on Scotland's east coast, has a deserved place in the guidebooks. But its place in history books, I submit, is not nearly as prominent as it should be.

The Scots, of course, do honour the ruined abbey. It is best known for the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, a letter drafted by a local monk (they had to find a guy who wrote decent Latin) and signed by nobles asking the Pope to recognise Scotland's right to independence.

The National Records of Scotland describe it as the "most famous historical record" they hold. The monastery, the Arbroath Abbey leaflet says, is "rightly famed for its place in Scotland's national consciousness".

But if that was all there was to it, the declaration would be precious only to Scots. You might reply that it voices a yearning for autonomy that others can identify with, but such a yearning is hardly original: Demosthenes and the Bible expressed it about two millennia earlier (in fact, some Scottish nationalists have invoked the Old Testament, implicitly equating English kings with Pharaoh.)

What matters most in the Declaration of Arbroath is not what it says about foreign rulers leaving people alone. It is what it says about the relationship between a people and its own rulers.

A few words of context: the death of a king in 1286 (in a stupid accident I've already written about) triggered a succession crisis that was fraught even by the standards of medieval Scotland. The desperate Scots asked Edward I of England to help them pick their new king.

Things unravelled from there: Ed seized the opportunity to claim overlordship over Scotland. Some Scots felt a type of loose allegiance was acceptable, but most said no. A rejectionist government struck an alliance with France, which precipitated an English invasion.

It was a brutal affair. In the 1290s William Wallace (a.k.a. Mel Gibson) started a guerrilla war against the occupiers, until he was betrayed and executed. Robert the Bruce picked up the fight, as well as the Scottish crown.

He was a great leader and his campaign achieved a lot in the early 14th century. But he had a problem: the Pope backed the English kings' claim. "God with us" was not an empty slogan then.

So the Declaration of Arbroath asks Pope John XXII to change tack – and, incodentally, to lift various excommunications the Bruce had on his head.

Now for the key passage: "If [Lord Robert] should agree to make us or our kingdom subject to the King of England or the English, we should exert ourselves at once to drive him out as our enemy... for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule."

In other words the king's will is not absolute: his subjects are not bound to him unconditionally. The declaration presents the nation not just as distinct from its rulers, but potentially in conflict with them.

Thus, in the middle of a savage war of independence, a bunch of medieval bigwigs managed to spell out a universal principle. This is why the declaration was awarded special status by Unesco.

It should be regarded as a founding text of liberalism, along with the Magna Carta, the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

You might object that such fancy words are cheap. The Arbroath plea for pontifical support was singularly ineffectual. It sat on John XXII's desk for nine years, by which time the Bruce had thrashed the English on the battlefield.

Moreover, the warlord's actions belie his noble principles. He was ruthless with rivals and his love of independence did not extend to Ireland, which he invaded. The Bruce was no different from the opportunistic barons who couched their beef in the self-righteous language of a Magna Carta that was immediately torn up by King John.

And for sheer hypocrisy, it is hard to beat America's slave-owning Founding Fathers and the blade-happy French Revolutionaries.

I concede all that. In fact, I would go so far as to say that Arbroath Abbey itself is a testament to betrayed ideals. It was founded in 1178 by William I of Scotland in memory of his childhood friend Thomas Becket, an English archbishop who died to keep the Church independent from the state.

Having built a shrine to the separation of powers, William showered it with all the perks of royal favour. These included lucrative trading privileges and income from 24 parishes. The abbey grew wealthy indeed, becoming a magnet for well-connected leeches.

As the Arbroath leaflet says: "After 1500, the post of abbot became more a source of income than a position of spiritual leadership." No wonder the abbey was ransacked during the Reformation (hence its present state – I described how Scotland's Calvinist rampage started in this post).

None of that is meant to dismiss declarations of principles. Some words, in the long run, speak louder actions. There are times when it takes more courage to preach than to practice, and an eloquent sinner is more precious than a silent saint.

Judge the quality of the vision, not the virtue of the visionary. If they give you a stick you can use against any evildoer – including themselves – they contribute to human progress. The Arbroath declaration does that as clearly as any of the tablets of liberalism hallowed by history books.

0 notes

Text

North Sea Scotland (7): The castle, the coal heiress and the conman

Glamis Castle has name recognition as the setting of Shakespeare's Macbeth - although the 11th-century Scottish king had no connection with the place.

But the castle deserves to be known for the real-life story of an occupant with untainted royal pedigree.

Glamis (pronounced "Glahms") has been the home of the Lyon family since the 1300s. Those folks have staying power. They saw out the century between the 1640s and 1740s, a turbulent one for Scottish aristocracy, without too much damage.

The castle was ransacked by Cromwell's troops. But after the Restoration, the Lyons' loyalty to the Stuarts (evident in the strutting representations of James VI/I and Charles I outside the castle, below) was rewarded with an upgraded title of "Earls of Strathmore".

Things got tricky again after the Stuarts' eviction. Some Lyons/Strathmores got involved with the Jacobite rebellion of 1715. Most, however, played the game and the clan held its own in Hanoverian Britain.

Fast forward to 1767 when the 29-year-old ninth earl, John Lyon, decides to marry an 18-year-old heiress from northern England, Mary Eleanor Bowes.

He can do with a rich wife. She's OK with it as well: known as "the beautiful Lord Strathmore", he cuts a dashing figure.

The marriage settlement is not a quick affair. Mary's late father, coal baron George Bowes, insisted in his will that whoever weds his only child should take the Bowes name. Negotiations take 18 months. The name change requires an act of parliament.

But in the end, John Lyon becomes John Bowes and Mary a countess.

But pretty soon she realises that life as Glamis is not all that glam. John turns out to be a disappointment. He wastes his good looks on study, plans for extensions to the castle – which her money will pay for – and letters to the gardener about orchards and yew hedges.

Mary is no Philistine. She writes poetry and likes botany, but a girl has to have fun once in a while.

When John dies of consumption in 1776, she is not devastated. In fact, she is pregnant by her lover, a Scottish rogue who has just blown his inheritance on ventures in India.

He was keen on marrying her, but Mary knew exactly what he would do with her fortune so had an abortion instead.

Wise to chancers as she was, she was not prepared for what hit her next.

Andrew Stoney, unlike her Scottish wastrel, was wily. He charmed her with laments for his first wife - who had died in suspicious circumstances, leaving her money to him - and with tall tales of military derring-do.

Mary was happy to sleep with Stoney, but unsure about going further. So Stoney devised a brilliant stratagem.

Using a pseudonym, he wrote articles about her private life in The Morning Post, feigned outrage and got the editor to print his defence of the countess's besmirched virtue.

When Mary laughed the whole thing off, Stoney stepped up a gear: he insisted on fighting a duel with the editor.

The whole thing, of course, was staged. Faking a mortal injury, Stoney persuaded Mary to grant him his dying wish: marry him. He was carried to the altar on a stretcher, and managed to whimper "I do".

Stoney, now Stoney Bowes, enjoyed a miracle recovery and dropped all pretence. He abused his new wife verbally and physically. He held drunken orgies with prostitutes in their home. When he learned that she had placed her money in a trust before marrying, he tried to force her to hand control to him.

He even imprisoned the countess. In 1785, she managed to escape and file for divorce, a pioneering step. The proceedings dragged on, allowing Stoney Bowes to abduct her again. In the end, she did get her divorce. Stoney Bowes was convicted of assault and died in prison.

Mary Eleanor Bowes was exceptional in many ways. Her only book, the self-published The Siege of Jerusalem, earned her a place in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey. But poetry and precedent in family law are not her only contributions to posterity.

One branch of the Bowes family – which we came across in Barnard Castle in northern England - have been major patrons of the arts since the 19th century.

Mary's great-great-great-granddaugther Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon was born in Glamis in 1900. She married the Duke of York and became queen consort when his brother renounced the throne in 1936.

The couple's daughter ended up being Britain's longest-reigning monarch. That daughter's son (Mary's great-great-great-great-great grandson, if my fingers are correct) is now king.

1 note

·

View note

Text

North Sea Scotland (6): In Pictland

The Picts are Europe's noble savage.

Proud, fierce and independent, they are easy to admire, and chief among the admirers were their enemies. Tacitus, so-in-law of a Roman general who fought them, commended them for defending the world's "last inch of liberty".

The Picts could never be subdued, only wiped out. Their disappearance from the record around the 10th century adds to their mystique.

They had no writing but did not leave without a trace. About 200 carved stones remain dotted around the Picts' heartland.

A clutch of them are on display at a great little museum just north of Dundee, the Meigle Sculpture Stone Museum. They are not just stunning works of art: they bear testimony to a tragic history.

But before turning to those slabs, I'll go through a few things we know about the Picts from other sources. As mentioned in my previous post, they were a Brittonic people. Britons, by the way, are Celts who lived on the island of Britain during the Iron Age and are distinct from Gaelic Celts from Ireland.

While the Romans conquered most of Britain, Picts and other Brittonic holdouts kept them out of "Caledonia". The Anglo-Saxons who replaced the Romans also stayed south of the border – initially at least – to focus on fighting each other.

Meanwhile the Picts prospered. By the fifth century, their kingdom stretched from the top of Scotland to the Firth of Forth, the inlet just north of Edinburgh.

At a time when Anglo-Saxons and Gaelic Scots were fragmented into warring chiefdoms and clans, Pictland remained united (apart from a temporary north-south split following the introduction of Christianity).

So what was the secret of the Picts' success? I found a convincing explanation in Jamie Jeffers' engagingly erudite British History Podcast: matrilineal succession.

The rule around Europe then - and until the 20th century - was that first-born sons inherited the crown. The system might not yield the best person for the job but it had the virtue of simplicity: if a) your dad is king and b) you've got a penis but no older sibling who does, then you're next in line. End of.

The Picts had different approach. Tribal chiefs got together and settled successions through consensus, a process that was better at weeding out obvious inadequates than accident of birth.

And crucially, they chose among candidates who could trace their royal ancestry through the female line. As Jeffers notes, this prevented disputes: if the male carries the magic blood, there is always a possibility that his partner could carry another man's child and the throne loses its magic; if it's the woman who carries the magic blood, then you know that her offspring carries it as well.

Princesses, in other words, had quasi-mystical pulling power among Pictish nobles, a unifying feature reinforced by the deliberative selection system. To Jeffers' analysis, I would add the hypothesis that any increase in the status of women - even limited to royals - contributes to the cohesiveness, stability and sophistication of a society. Just look at today's Denmark vs the Tabilan's Afghanistan.

This brings me back to the Meigle museum, where the high degree of Pictish civilisation is on display.

The stones tell us about the beliefs of a deeply pious people.

Among the distinctive symbols and patterns are representations of fabulous creatures, including a lion with a man's head and dancing sea-horses (above).

The Picts were also fond of domestic animals.

The menageries above feature horses, stags, cattle as well as the manticore, a monster of middle-eastern origin with the tail of a scorpion. Clearly the Picts were aware of distant lands.

Several stones combine pagan and Christian symbols, illustrating how the new religion was assimilated into ancient beliefs. They show crosses superimposed on representations of animals. Note the seahorses again and the cat on the bottom left!

I couldn't help but see those stones as expressions of unity. As mentioned, northern Picts were slower than southerners in adopting Christianity. The carvings seem to say: whatever our beliefs, we are one nation.

The last of the stones date from about 850 AD. No trace of a Pictish civilisation remains beyond 900. This raises the question: if the Picts were so sophisticated, why did they vanish? Well, the superior nature of a civilisation does not a guarantee survival.

In the end, the Picts had too many enemies: Gaelic Scots to the west, Brittonic rivals to the south-west and increasingly assertive Anglo-Saxons in the south. For a while, the Picts dealt with these threats by a combination of force and bridal diplomacy. Pictish princesses married potential foes.

In the ninth century, Viking invasions forced the Picts to get closer to the Scots. This political shift led to Gaelic symbols appearing on Pictish stones.

In 843, Kenneth MacAlpin absorbed Pictland into his Scottish kingdom. The fact that his mother was Pictish helped the junior partner accept the takeover. But it spelled the end for their nation.

The Picts themselves, it appears, understood the limits of bridalism as a foreign-policy tool.

One of the more intriguing stones shows a human figure set upon by animals (below). Museum curators say she could be Guinevere, the wife of King Arthur.

The Welsh legend was adopted by the Picts. In their version Guinevere was a Pictish princess, known locally as Vanora, whose marriage to Arthur highlighted Brittonic unity against the Anglo-Saxons.

But the alliance did not work out: Vanora, as the carvings show, was fed to ravenous beasts by her jealous husband.

0 notes

Text

North Sea Scotland (5): Old Scone

No visit to Perth is complete without a visit to Scone Palace. And no visit to Scone is complete without a pronunciation lesson.

After multiple enquiries, I established that it rhymes with "spoon". A confusing factor is the way some locals shorten the "oo" vowel (to a Londoner's ear, a Scottish "soon" can sound like a Liverpudlian "sun"). But they expected you to say "skoon".

Scone the location has no etymological connection to the delicacy. The scone you eat rhymes with "gone".

The place has considerable historical significance. Scone was the biblically sanctioned seat of royal power in Scotland.

It was the capital of the Picts. A few words about these valiant people are needed: Picts were "Brittonic" Celts, like other tribes that had the run of Britain before Romans turned up. Brittonic groups must not be confused with Scots and other Gaelic Celts who came from Ireland.

The Picts were true Brits. While their brethren south of the border were subdued, the Picts kept the empire at bay. Eventually the Romans built a wall to keep them at bay.

The Picts are often thought of as savages. But that's because, unlike their Roman victims, they didn't write things down. Behind their warring prowess lay a highly sophisticated civilisation.

Picts and Scots embraced Christianity well before Augustine converted England. In fact, the Scots were such early adopters that they got custody of the stone Jacob had used as a pillow to dream on (Gen 28; 10-22).

In 843 Kenneth McAlpin unified the rival groups to become king of Alba ("Scotland" was the result of a subsequent rebranding exercise). He had the holy rock moved from a Scottish monastery to Scone, where it served as a coronation seat for centuries.

In 1296, Edward I of England invaded and took the stone to Westminster. The theft acquired a simulacrum of legitimacy when the two crowns merged 307 years later.

But the Stone of Destiny was destined to return to Scotland. In 1950 Scottish nationalists broke into Westminster Abbey and briefly took it to Glasgow. In 1996 it was handed back for good. The stone now sits at Edinburgh Castle. Scone only got a replica.

The Scots let the English borrow it for King Charles' coronation.

You will note that it fits underneath the coronation chair: stone was fine for Biblical heads and Scottish bottoms, but not good enough for English softies.

There have been doubts about the authenticity of the sacred slab. Geologists say it is made of Perthshire sandstone. No one is questioning the fact that Jacob's stone travelled to Scotland: we have that on the highest medieval religious authority.

But you wonder if those Scottish monks may have given Kenneth a fake. There are suggestions that Edward was similarly fobbed off. The stone currently in Scone could be the replica of a replica of a replica.

But where might all the replicated items be? My answer: everywhere and nowhere. Copies of the stone are dotted around Scotland (we saw another one at Arbroath monastery, below). Any of them could be the real thing - or not.

The largest copy in Scone, however, is not the stone but the palace itself (top picture). This identikit of a grand English house was built by a Scottish peer in the nineteenth century.

The earls of Mansfield are still based there. They dropped the title "Lord Scone" in 1970, probably when they wearied of having their names mispronounced and being paired with earls of Sandwich by facetious dinner-party hosts.

0 notes

Text

North Sea Scotland (4): Perth

The previous entry ended with our departure from Dundee, which was ugly and wet.

Perth, a short drive away, was just wet. The rain eased, revealing the beauty of this old royal burgh.

It occupies a choice spot on the River Tay where it is both easy to cross and tidal, allowing ships to moor.

This, an information panel revealed, made the city a trade hub in the Middle Ages. It was also designated as a "craftis toun" because of its top-quality products.

Glovers, we learned, were the most influential guild in medieval Perth. The industry naturally attracted tanners. The panel included a depiction of their quarter circa 1440:

Leather-making apparently involved soaking hides into a mix of urine and dogs' faeces.

This, I thought, provided interesting historical background to the Spinal Tap album Smell the Glove.

The oldest house in Perth is said to be "Fair Maid's House". But the inscription "1393"was suspiciously legible.

The plaque said the habitation drew its name from Sir Walter Scott's novel The Fair Maid of Perth - which was published in 1828!

In short the house looked to me as medieval as Deep Purple's Book of Taliesyn album (I don't know why walking in Perth put vintage rock into my head.)

But if you're into faux medieval, nothing beats the real thing: Victorian arts-and-crafts architecture.

Perth has plenty of wonderful specimens. Many, I noted, have been taken over by the food-and-drink industry.

The above buildings – all from the 1890s – now house Perth's Pizza Express (left), an Indian restaurant (centre) and a pub (right).

The river front is lined with glorious Gothic-revival erections.

The County Buildings (1881, above) initially a natural history museum is now, predictably, a fancy eatery.

My favourite building is the 1840s police HQ (below).

Carved into these stern stones is the inscription: "This house hates knaves, crimes punisheth, preserves the laws and good men honoureth."

Contrast that with the "transformative vision" for Scottish justice set out in 2022 "with a focus on creating safer communities and shifting societal attitudes and circumstances which perpetuate crime and harm".

The Tay, the longest river in Scotland, can be fierce in Perth. In days of old, a panel explained, people dealt with flooding by demolishing damaged structures and building new ones on top until the ground was raised to a safe level.

The above picture was taken from a spot where Perth Castle once stood. It was washed away in 1209.

It was not the last traumatic event to occur at this site. Dominicans built a monastery on the ruins of the castle. Two centuries later, James I of Scotland died there in unusual circumstances.

James had a habit of dealing ruthlessly with rivals. But what did for him was not so much his love of power as his love of tennis. In 1436, he decided to spend Christmas at the monastery. It had great traveller reviews, as well as an indoor court where he could practice his favourite sport.

Knowing plotters were after him, James familiarised himself with escape routes before settling down for a nice extended holiday. But there was a problem with the tennis: his balls kept falling down a drain pipe.

The king got so frustrated that he ordered the drain to be blocked. Three days later his enemies reached the monastery. He disappeared down a hatch. The tunnel, however, led to the drain that had been filled with stone. He was swiftly slaughtered by his pursuers.

Fast forward 122 years. As a previous post explained, mid-16th century Scotland was ruled by Catholics but ripe for Protestantism. Knowing which way the wind was blowing, the Calvinist preacher John Knox returned home after 11 years in exile.

In May 1559 he headed to Perth and commandeered St John's Kirk (top image).

From a pulpit surrounded by the paraphernalia of Popish superstition (relics, stained glass windows, painted walls, etc.), Knox inveighed against idolatry. Whipped into an iconoclastic frenzy, the crowd trashed the church.

The crowds then headed for the Dominican priory and ransacked it. Perth's three other monasteries – as well all 40 altars in the city - were destroyed in two days of rioting. Knox went on to repeat the feat at St Andrews cathedral 50 miles away. The Scottish Church fell like a house of cards.

Perth these days is endearingly unthreatening. During our wanderings we came across a parade. A crowd cheered as bagpipe players in kilts, aldermen in suits, Scots Guards in Jeeps and Star Warriors in costumes filed past.

Towards the end a brass band played the vintage hit Gimme Some Lovin'.

1 note

·

View note

Text

North Sea Scotland (3): Dundee

Warning: This post contains odes to a city's industrial heritage, which some readers may find inappropriate, or just boring.

Our trip so far: we crossed into Scotland, headed straight north to Fife, giving Edinburgh a miss, followed the tourist route along the Firth of Forth and ended up in St Andrews.

The next city up the coast was Dundee.

It has been called the "drug-death capital of Europe" and the "suicide capital of Scotland". We figured Dundee couldn't be that bad and made it our base for a few days.

Our first impressions, however, did little to set the record straight. Below is the view from the place where we stayed.

The next morning, as we set out to explore the city, it began to rain. The museum was the best option.

We found it in this area - the actual building is on the right:

A refurbished 19th-century factory, the museum calls itself "Verdant Works".

The original inhabitants, it must be noted, didn't go in for bucolic appellations. This part of Dundee is named "Blackness" and the brook that runs through it is the "Scouring Burn".

Despite its curious designation, Verdant Works turned out to be a top-notch industrial museum.

Dundee, I learned, grew rich from textiles. In the 16th and 17th centuries local operators began to produce coarse linen from flax – stuff for sacks rather than clothing.

The cottage industry grew in the 18th century, thanks to flax imported from Russia. The government stepped in, on the mercantilist assumption of the time: a key function of the state was to nurture domestic trade and industry.

Thus in Scotland a "Board of Trustees of Fisheries and Manufactures" was created in 1727 to spur flax cultivation. Its "stampmasters" carried out systematic inspections to guarantee quality.

"Dundee's stampmaster David Blair," one panel says, "was known to be particularly vigilant, refusing to pass any adulterated or inadequate cloth."

Another mercantilist measure was the "bounty", an export subsidy that led to soaring linen exports to American in the second half of the 18th century.

But everything is a matter of trade-offs. The downside of government intervention was that manufacturers were stuck with approved fibres. The board "discouraged the use of substitutes for flax in canvas weaving," the museum explains.

From the late 18th century, the idea markets could do fine without bureaucratic encouragement began to take hold (it was a Scot, incidentally, who popularised it in a 1776 best-seller.)

Stamping was abolished in 1823. Mercantilism truly ended when Britain lifted trade restrictions in the 1830s.

Free to experiment and choose suppliers, Dundee's manufacturers found a cheap, excellent raw material for canvas in India. Jute is a taller and easier to harvest than flax. The humid climate where jute grows means the bark rots quickly, making it straightforward to extract the fibre.

By the 1850s, jute overtook flax as Dundee's money spinner. Geopolitics helped. As the museum notes, the Crimean war and the American Civil War created "great demand for tenting, horse blankets, wagon and gun covers, sandbags and for carrying supplies".

But the city’s boom was mostly the result of globalisation.

Strong and porous, jute sacks were ideal for transport and allowed commodities – whether grain, coffee flour, sugar, seeds, coal – to breathe.

Dundee products also moved people: "The emigrants went on to travel across the continents to find land to settle, whilst sheltering beneath jute and linen wagon covers and tents."

Machinery displayed at Verdant Works provides a chance to explore the stages of jute production in fascinating detail.

The processes involved have magical names, such as carding or roving.

Above is a beaming machine. The explanation provided can be arranged as poetry:

"The ends from the swift are taken

Through the top reed

And a tensioning roller

And then tied into the beam."

The emergence of synthetic canvases has not made jute redundant. These days the stuff is used as backing for carpet, lining for shoes, component for roofing, protection for cables.

Jute also makes aprons, mattresses, tarpaulins, conveyor belts, lampshades - and of course sacks and ropes.

Although Dundee developed this most versatile of fabrics and spread it around the world, the city no longer benefits from its enduring appeal.

Today's industry, sensibly, is based where as the plant grows: on the Indian subcontinent. There, the curators say, "the livelihood of millions of people depends on jute production".

So the Industrial Revolution and globalisation may not be a rich-world conspiracy against the wretched of the Earth after all! (Verdant Works is refreshingly free of the guilt-inducing lectures that are rife in modern museums.)

India's jute industry grew over the past 100 years. Many factories were set up by Dundee manufacturers with machines from their redundant works.

After such a wonderfully informative visit, we were curious to get a sense of what the city lives on nowadays. But it was still raining as we walked out. We were faced with this sight:

A short road trip seemed more appealing than a city walk.

0 notes

Text

North Sea Scotland (2): Unholy St Andrews

Despite its famed 18-hole course and prestigious university, St Andrews was not built on golf or study. It was built on religion.

A very long time ago, some Irish monk got his hands on a tooth and a kneecap of Andrew the Apostle and brought them here. A monastic community grew around the relics.

Medieval St Andrews once had equal status with Santiago de Compostela, another city named after the apostle whose bones it keeps in storage. Equal in the eyes of the Church, that is: in Europe's pilgrimage mass market, of course, Scotland's North Sea shores were a tougher sell than the Spanish seaside.

Still, St Andrews had a cachet that its English counterpart could only dream of. Canterbury had the full body of a saint, but he was a recent, local martyr. Scottish archbishops commanded full respect from their kings: no royal whining about pesky priests – let alone murders in cathedrals – there.

The bishops, not the kings, built St Andrews Castle in the 1100s. Two centuries later, Church support was crucial in the resistance against England.

The castle we see today (pictured above) is what's left of a fortress built by a bishop in the 1390s to make sure it would never fall into English hands again.

And it was clerics who founded the University. Some of its buildings date from the 16th century.

The Reformation, however, had particularly far-reaching consequences in Scotland. The Church was not transformed: it was obliterated, resulting in the permanent downgrading of St Andrews.

The archbishops started by hunting down Lutherans in the 1520s. In 1528 one preacher was burnt at the stake outside St Salvator's College (its 19th-century incarnation is below right, with a nearby grand hall on the left).

It didn't help when the English king, after breaking with Rome, attacked Scotland for refusing to follow suit. The Scottish Church was able to play the nationalist card and call Protestants traitors.

Things got worse after the Scottish king died in 1542. His daughter Mary was a baby, so a regency was organised. Although the regent himself was moderate Catholic, the king's French widow, Marie de Guise, fanned the flames of Popish extremism.

South of the border, Henry VIII renewed his attacks – this time aimed at forcing a marriage between his own son and Mary. This only strengthened Catholic diehards in Scotland.

In 1546 another Protestant was burnt alive in front of St Andrews Castle. Some of his followers made their way inside, stabbed the archbishop, hung his body from the castle walls and dug in. Then ensuing siege began lasted a year.

In 1547, Protestant ministers were allowed to join the hold-outs. One of them, John Knox, used that opportunity to form Scotland's first Protestant congregation.

But Marie de Guise, who was in no mood for negotiation, got French gunboats to bomb the castle. The rebels surrendered. Knox and others were bundled onto French galleys. They may owe their lives to the fact that the new archbishop, the regent's own brother, favoured appeasement.

The most dangerous time for a bad regime, Tocqueville wrote, is when it tries to reform itself. He was talking about France's absolute monarchy, but the rule also explains the end of Apartheid and the fall of Communism.

And it is confirmed by the fate of the Scottish Church. By the mid-1550s, it was no longer in lockstep with the Royal Palace. While the archbishop in St Andrews had given up clobbering Protestants, across the Firth Marie de Guise was keen on persecution. Power was divided.

Meanwhile, Knox was biding his time. After his release from the galley he knocked around Reformation Europe, reading up on predestination and honing his rhetorical skills. In 1559, sensing another opportunity, he returned home from Geneva.

Knox – now a full-blown Calvinist - was declared persona non grata by the government. But he managed to make his way to Perth where he had sympathisers. The local priest allowed Knox to speak during Mass. His sermon on idolatry incited the crowd to trash the church on the spot.

Knox went on to St Andrews, Antichrist's high command in Scotland. His imprecations against the "Hoore of Babylon" had the intended effect: the cathedral was ransacked. A year later Marie de Guise was dead and the Edinburgh Parliament rejected papal authority.

It meant the end of St Andrews as a religious centre. To see why, you have to understand the nature of the Scottish Reformation.

Elsewhere in Europe, the break with Rome was driven by local princes, who adapted existing institutions to the new faith. The new Church of England replaced the old English Church. The Canterbury cathedral had a new master but it remained a religious HQ.

Scotland's reformation, by contrast, was imposed on hostile rulers. Thus the Presbyterian Church of Scotland was nothing like the old Scottish Church. Knox rejected the hierarchical model. The Kirk was a grassroots organisation: no bishops, much less archbishops, and no alliance with the state.

This is why Canterbury's Cathedral still stands tall and St Andrews' has been left to crumble (top picture). The repository of relics is a relic itself.

Powerful people still come to St Andrews - but only to hit the links or put their kids through college, not to kiss any rings.

1 note

·

View note

Text

North Sea Scotland (1): Neuk shelter

Having crossed into Scotland (read about it here), we skipped the big southern cities and headed to Fife.

That region lies beyond the Firth of Forth, the estuary just north of Edinburgh.

Its sheltered waters have made it a focus of trade – and thus power - from time immemorial. Fife was the ancestral capital of Scottish kings.

The regional council advertised a "Fife tourist route", so we gave it a go. The best spot is at the western end.

With its 17th and 18th century homes (pictures above), Culross is as easy on the eye as it is hard on the tongue - to pronounce it half-way correctly, try saying "Culross/made to lure us" as a rhyming slogan.

The "Culross Palace" (below) is mansion built around 1600 by George Bruce, a mining baron. It houses a museum that explains how he brought royal favour and prosperity to Culross.

Bruce invented a drainage system that allowed miners to dig coal from under the Firth of Forth without getting wet.

King James VI was impressed and made Culross a "royal burgh", meaning it could trade overseas.

Crail, at the eastern end of the route, is also gorgeous.

That old fishing village is confusingly pronounced as you expect, rhyming with "Grail".

The coastline between Culross and Crail is called the East Neuk (as in "nuke"). We found it underwhelming, whatever the Fife tourist board said.

We were hoping to stop for lunch in tearooms by a quaint harbour, but had to settle for a café in an industrial estate on the outskirts of Kirkaldy.

But the East Neuk is interesting for historical reasons. It is the site of an epochal tragedy.

Alexander III (1241-1286) was the best king medieval Scots could wish for. He put a lid on clan feuds. He kept the English sweet, having married Henry III's daughter.

She died young but had time to produce two sons and a daughter. The succession seemed safe. Without a pressing need to remarry, Alexander played the field – particularly in convents.

According to one chronicler, the king would never "forbear on account of season or storm, nor for perils of rocky cliffs, but would visit nuns or matrons, virgins or widows as the fancy seized him".

But in the early 1280s, things started to go south for the happy widower. All three kids died. The daughter had had time to give birth to a baby girl (she was married to the king of Norway). In 1284, Alexander rushed to name his newborn granddaughter as his heir.

Messy successions were a recipe for disaster. The King's Council felt it was safer if Alexander had a son.

"Look near convents," he said breezily, "I'm sure you'll find one."

"He must be legitimate, my Lord. Otherwise every Scott, Bruce and Rory in the land will claim he's your kid and all hell will break loose again."

A French bride was found. At 44, the king was still in his prime when he remarried. Shortly thereafter, yearning for his new wife after a long day's work in Edinburgh, he decided to rejoin her in Kinghorn across the Firth.

"This is madness," the chief councillor said. "It's dark and a storm is raging."

To be clear, Alexander was planning to ride 10 miles west from Edinburgh to the crossing, take a barge and then travel east another 12 miles – in driving rain.

That was no problem, the king insisted: he had ridden through night and wind many times before; and it was not rough seas he was crossing, but the sheltered Firth.

Alexander did make it to the northern shore. At Inverkeithing, he was met by nobles who begged him to stay: "My lord, what are you doing out in such weather? How many times have I told you that midnight travelling will do you no good?"

But the conjugal bed was calling. A mile from Kinghorn the horse lost his footing. The animal and the master broke their necks on the Neuk's shore.

The photo below was taken near the spot: over the Firth are the outskirts of Edinburgh; you can just about see the crossing on the right in the distance.

With the king dead, the councillors hit the panic button.

Stability now depended on his three-year-old granddaughter. She had to be repatriated from the wilds of Scandinavia to Scotland's shielded shores.

She died on the way, triggering a succession crisis that plunged the realm into bloody chaos for 70 years.

0 notes

Text

The most dangerous place in England

The information sign on the village green had me reaching for my phone. Could Norham really have ever been "the most dangerous place in England"? A quick fact check established that this was a credible claim.

Norham lies in the far north-eastern corner of England, within striking distance (by cannon, bow or slingshot) of Scotland across the River Tweed.