#alexandros IV

Photo

Ancient Greek gold coinage.

Hellenistic Kings and Queens ruled an area from Greece in the west till India in the east.

From left to right:

1) King Asandros, Kingdom of Bosporos/Pontos (Black Sea region), 36 BC

2) King Demetrius I Poliorketes, Kingdom of Macedonia, 3rd BC

3) Seleukos II, Seleucid Empire, 3rd BC

4) Antiochos III o Megas (the Great), Seleucid Empire, 3rd-2nd BC

5) King Ptolemaios II, Kingdom of Egypt, 3rd BC

6) King Alexandros IV (the young Prince/Son of Alexander the Great), Kingdom of Macedonia, 323-315 BC

7) King Achaios (usurpator), Seleucid Empire, 220-213 BC

8) King Menander I Soter, Kingdom of Indo-Greeks (appr. modern Afghanistan -parts of India), 165-130 BC

9) Queen Arsinoe II, Kingdom of Egypt, 283-246 BC.

#art#design#coin#gold#style#history#greek#king#queen#hellenistic#king asandros#king demetrius#seleukos II#achaios#arsinoe#alexandros IV#macedonia#seleucid#ptolemaios#menander I#india#afghanistan#egypt#archeology

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

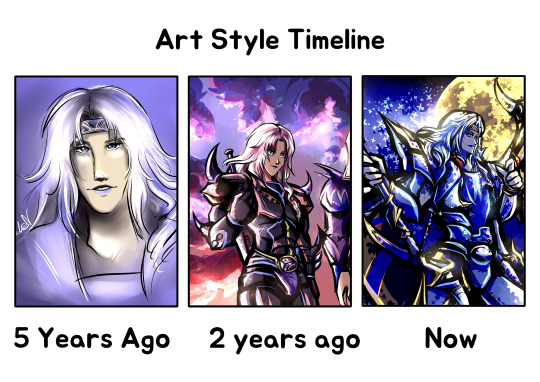

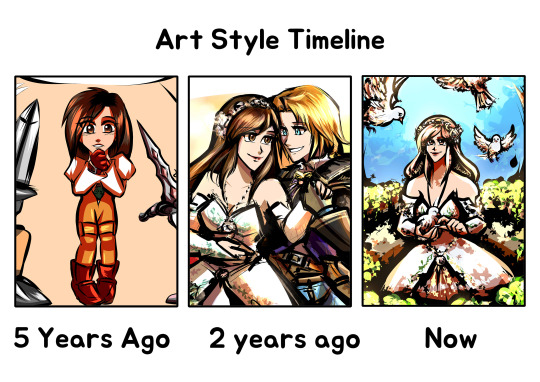

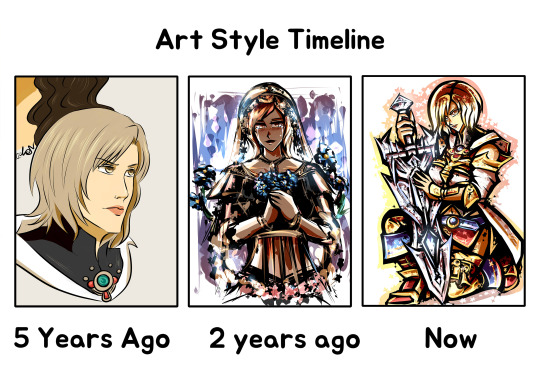

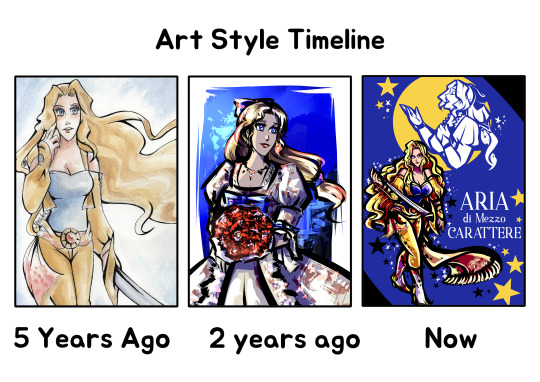

[Final Fantasy] edition! Cecil, Garnet, Ashe and Celes, among others, have been my muses, and they will always be 💗✨

Challenge by SunnyDionysus (twittah)

MY COMMISSIONS INFO

#my artwork#final fantasy#ffiv#ffvi#ffix#ffxii#ff12#ff4#ff9#ff6#final fantasy iv#cecil harvey#final fantasy vi#celes chere#final fantasy ix#garnet til alexandros#final fantasy xii#ashelia b'nargin dalmasca

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Final Fantasy x Songkran 2023 is completed yay!

Thank you ALblavender on Twitter for the prompt.

You can support me here❤️

#final fantasy#final fantasy ii#final fantasy iv#final fantasy vii remake#final fantasy viii#final fantasy ix#final fantasy xiv#final fantasy xv#emperor mateus#kain highwind#tifa lockhart#selphie tilmitt#garnet til alexandros#zenos yae galvus#lunafreya nox fleuret#my fanart

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want...... no..... i Need to draw fake screenshots from the rental car dating sim that is absolutely still a joke and definitely not something i am willing to make at some point no sir except that it definitely isn't and i definitely am

#like either fuckinnnn way#itll be a funky little art thing i can kill a few hours on hahahaha#i also need to draw young quinn and young alex aka edgy grunge phase quinn and miserable buzzcut alex#i also need to draw alexandro still#ALSO I NEED TO DRAW KAI#bc ive been neglecting my atdao blorbos and i have an ask abt kai that i wanted to doodle a little kai for c:#also..... i need to go to bed.#i have to be up early to take squeaky boy in for his tooth surgery#theeeeeen i need to go in for a blood test then i need to make a bunch of phone calls#then I'll probably go back to sleep all afternoon tbhhhhh

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Reading the Wikipedia articles of most Ptolemaic kings, there's a note right at the beginning: "Numbering the Ptolemies is a modern convention. Older sources may give a number one higher or lower. The most reliable way of determining which Ptolemy is being referred to in any given case is by epithet (e.g. "Philopator")".

I did not find a similar note in articles about the Argeads, Seleucids, or any other Hellenistic dynasty, for that matter, even if their members generally had epithets. This made me look into the list of Ancient Macedonian monarchs, as it occured to me that, besides Alexander the Great, I could not name a single pre-Alexander monarch with an epithet! The only ones I could find were Alexander I the Philhellene and Amyntas II the Little.

Hellenistic monarchs seem to have had all sorts of colorful epithets - Soter, Nicator, Epiphanes, Euergetes, Philopator. Even Macedonian kings had them, but most post-Alexander - Poliorketes, Gonatas, Keraunos. Is there a reason why the Macedonian monarchs from the Argead dynasty do not generally have epithets for which they are known?

Tl;dr answer: as the world widened and certain names became increasingly repetitive in ruling families, epithets were an easy way to separate them. The “numbering system” is recent and largely European. It was retrofitted to the medieval and ancient worlds when writing histories about these eras (and sometimes non-European regions too, such as Japan and China).

Epithets, or “nicknames,” became useful when identifying individuals outside their usual sphere of reference, especially if there might be more than one famous person from (say) Macedon named “Alexandros.”

Thus we get the most famous Alexander (III) Magnus/Megalexandros [the Great]/Alexandros ho Anikētos [the Undefeated], but also Alexandros (I) ho Philhellenas [the Philhellene]/Alexandros ho Khruseos [the Golden]. The first name listed for each is the one used by posterity, the latter was the name used in their own lifetime. So no, Alexander III was not called “the Great” until a while after his death. 😉

Identifying Individuals in Ancient Greece

We find a two- or three-tiered identification system:

Given Name

Father’s name in the genitive = [son/daughter] of ____ (patronymic)

Place of origin (also in the genitive = “of ____”)

The first two are all-but-universal, and the third is a common addition, but may be omitted in cases where the place of origin can be assumed. “Place of origin,” however, can vary. It may be a city-state/nation, or within a city-state, the phratry (clan) or tribe.

So, if you were to travel from, say, Eretria (on Euboia Island) to Athens, you’d identify yourself: Myron Apollodorou Eretrias = Myron, son of Apollodoros, of Eretria. You wouldn’t get specific about a phratry because you’re not home. Nobody cares.

Just like when I travel to Greece, I rarely say, “I’m from Omaha.” I usually just say, “I’m from the States,” and if they ask which state, I add “Nebraska”—which solicits confused looks. LOL If I were to begin with “I’m from Omaha,” they’d really be confused! It’s only inside the US that I say I’m from Omaha, Nebraska. Inside Omaha, I may give my neighborhood. So that’s a good referent as to how specific they might get, and under what circumstances.

Another fun fact: it was typical (if not absolute) for the first son to be named for his paternal grandfather, the second for his maternal grandfather, and then by various other male relatives. So, for instance, Perdikkas III, the first of Amyntas III’s sons to have a son, named the boy Amyntas. Ergo, Philip named Alexander for his elder brother, who didn’t live long enough to marry and procreate. Yet, again, it’s not absolute (unlike in Greece today); e.g., Demosthenes, son of Demosthenes; Aristobulos, son of Aristobulos … Alexander (IV), son of Alexander (III).

As for women, they’re identified by father or husband (or son or brother). It’s much rarer to see a place identifier, in part because women were assumed not to travel much. We get exceptions: the famous Aspasia, Perikles’s mistress, was identified (in Athens) as “from Miletos.” Also, in royal marriages. So, Olympias was daughter of Neoptolomos, of the Molossoi (ruling clan of Epiros): Olympias Neoptolomou Molossou.

When we get to these upper-class families, with their clan designations, we get closer to what, today, we’d call a “surname.”

Athens had several aristocratic clans, but the most famous/notorious were the Alkmeonidai, of which Kleisthenes, Perikles, Alkibiades, and Plato were all members (some via their mothers). Another Athenian example were the Philaidai (Miltiades and Kimon).

These aristocratic families took their name from a mythical forefather: e.g., Alkmaion, great-grandson of Nestor (yes, from the Iliad). This pattern was true all over Greece, not just Athens. These are largely the descendants of the old kings (basileis) and nobles (aristokratoi) of the Greek dark age/archaic age (e.g., Late Iron Age).

But in some areas, royal families persisted, such as Epiros, Macedon, and Sparta, who also kept the royal clan designation: Molossoi (Epiros), Temenidai (Macedon), Agiadai and Eurypontidai (Sparta). Thessaly’s main cities also has a semi-ruling royal family, such as the Aleuadai of Larissa, traditional allies of the Macedonian royal house.

While you’ll often see me refer to the Macedonian royal family as “Argeads,”* the clan name they’d have used was “Temenidai,” as they believed themselves to be descendants of Herakles (and thus, Zeus) through his great-great-grandson Temenos. Outside Macedonia, however, they’d use “Makedonon” (of Macedon). We find Alexander referred to on an ancient Roman bust (the Azara Herm) as Alexandros Philippou Makedonon

Non-royal Macedonians would use Patronymics (+ origin place), so Hephaistion is identified in Arrian as Hephaistion Amyntoros Pellais (Hephaistion, son of Amyntor, of Pella). Krateros, however, is identified only by his patronymic in our texts (the most common pattern), so we’re less clear on where he was from: Krateros Alexandrou (Orestidis?).

In the pre-Philip/Alexander era, it’s usually possible to untangle Macedonian kings by patronymic if employed, but even that doesn’t always work. The first Alexandros (I) was the son of an Amyntas and so was the second, Philip’s older brother. Fortunately, we find them referenced in such a way that we usually know who’s meant.

Usually.

Yet take the fragment from Anaximines (FGrH 72 F 4) that says simply “Alexandros” created the Pezhetairoi (Foot Companions).

Um… WHICH ONE?! Arguments have been made for Alexander I (Wrightson), Alexander II (Greenwalt), and Alexander III (various).

Welcome to the Wild, Wild West of ancient history. We write entire articles arguing “which Alexander” because the ancient sources didn’t identify him beyond a single name.

In any case, once Macedonia emerged onto the “world stage,” so to speak, it became critical to find better ways to identify the various Successor kings (Diadochi) of the Hellenistic era. All the more so as they frequently reused names (Ptolemies) or alternated (Seleukos/Antiochos). Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy isn’t very meaningful! Epithets became an easy way to identify which Ptolemy.

——————

* “Argead” is a modern usage for reasons I won’t go into or it’s Rabbit Hole Time about the putative Greekness (from Argos) of the Macedonian royal family. Suffice to say Alexander would be mightily puzzled to be called an Argead.

#asks#ancient royal designations#epithets for ancient kings#alexander the great#macedonian royal house#ancient greece#ancient greek naming patterns#ancient macedonia#classics#temenidae#naming ptolemies#naming seleucids#tagamemnon#royal designations

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

how do you keep names within a single culture sounding phonetically consistent? its something ive been struggling with a lot but you seem to be doing really well at it

I am?? That's a relief!

I guess the rule of thumb I use is considering which phonemes tend to show up in which languages/dialects and grouping similar ones into related names. Like if we take Greek heroes as an example, we could formulate a list of some good ones - Heracles, Perseus, Theseus, Achilles, Patroclus, Menelaus, Alexandros - and recognize some patterns. This space of characters features lots of three-syllable names where the final syllable sounds like "-eez" or "-us". There's also semi-frequent use of the "-kl-" phoneme in the middle of the names, and they tend to favor "-e-" and "-a-" vowel sounds outside of the final syllable. If we wanted to make names that sounded like they belonged in this space, we could start by drawing on these patterns.

Actually Greek is a good starting example, because it's responsible for a lot of English's reflexive assumptions about naming conventions. Female names like Clytemnestra, Atalanta, Sophia, Hippolyta, etc all end in "-a" because "-α" is a common feminine noun ender in Greek, in contrast to the masculine "-ος". Hebrew names like Sarah, Ariella, Ayla, Daniella, Devorah, etc do the same thing, some even being feminine versions of masculine names like David or Daniel, altered by adding an "-a" sound to the end. I don't know enough about linguistics to know if this is a coincidence or a common ancestry thing, but I think this is a large part of why we trend towards considering names that end in "-a" as more feminine.

Different languages have different common phonemes. The sound "-tsu-" is quite common in Japanese but is very rarely found in English or the romance languages. Slavic names often end in "-ov" or "-ovitz". Many Spanish surnames end with "-ez". Lots of cultures commonly feature family name components that mean "son of" like "fitz-", "mac-", "ben-" or (obviously) "-son".

And even within single groups, different phoneme patterns can be tied in with different things. A lot of Jewish family names started off as "ornamental surnames" adopted by families when the government demanded they stop with that inconvenient "son of-" or "daughter of-" tradition, and are thus constructed from simple German nouns of whatever was within line of sight at the time, like "Rosenbaum" (rose tree), "Goldstein" (gold rock), "Bloomenfeld" (flower field), "Hirsch" (deer), etc. Thus, the phoneme patterns of a lot of Jewish surnames draw on German origins and have very little in common with the phonemen patterns of Jewish first names like Sarah, Deborah, Noah, Elizabeth, Esther, Caleb, Nathaniel, Jacob, Gideon, etc.

If you're working entirely in a fantasy culture, rather than drawing on outside patterns you can just start your own. Most of my character names favor "-a-" and "-e-" vowel sounds, which helps them sound similar to one another. I also use "-l-" sounds more than other consonants, and as a result, Falst, Alinua and Kendal all kind of sounds like they belong in the same space. Erin and Tess, meanwhile, have the same short "-e-" sound in their names with none of that familiar "-a-" present, and Dainix - the most geographically and culturally far-flung - has two sounds not present in anyone else's names, an "-ay-" vowel sound and an "-ix" ender. What little we've seen of Ignan culture and naming conventions has other uses of the "-x-" consonant, mostly "ainox", which kind of helps make that seem like a unifying factor. To make sure things sound coherent when we deal with more Ignans, I might use those unique sounds more often, naming other ignans things like Rase or Lainn or Onix to produce a coherent *vibe*.

Personally as a strict no-conlanger I don't worldbuild the underlying logic behind these patterns, but frankly I don't think you need to. Just roll the sounds around in your head, pick out the patterns you want to explore, google them once to make sure you haven't accidentally recreated an obscure eastern european slur, and have a good time.

367 notes

·

View notes

Text

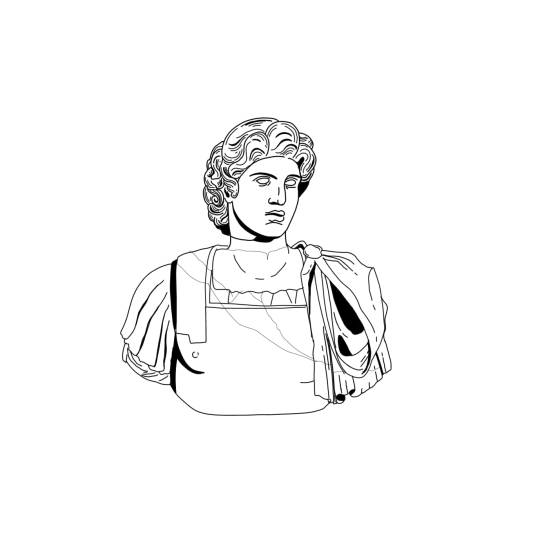

Im excited because tomorrow i get Alexandros The Great tattooed. He's become so important in the little time ive learnt about him. Open doors that i wouldn't have thought to explore before and makes me determined to push through and do my best in this world ❤️

#alexander the great#alexander#alexandros#alexandros III#ancient world#ancient greek#ancient#ancient soul#positivity#he means so much to me#i miss him#old soul#macedonia#alexander of macedon#hes important to me#i adore him#tattoos#tomorrow#excited

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

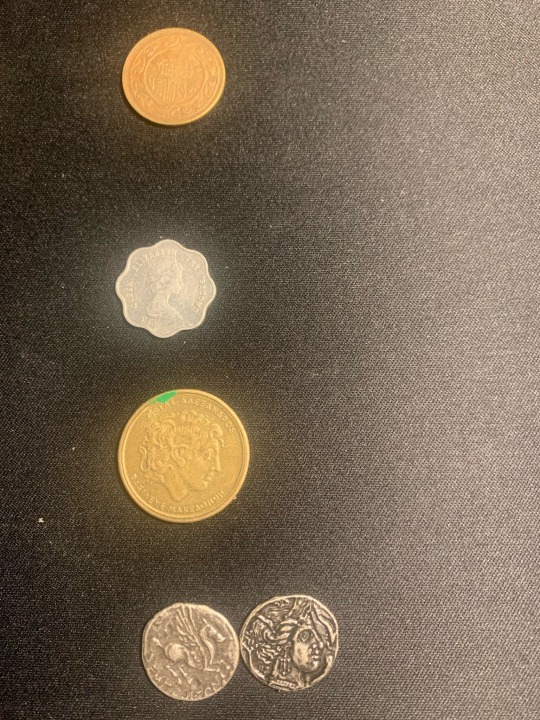

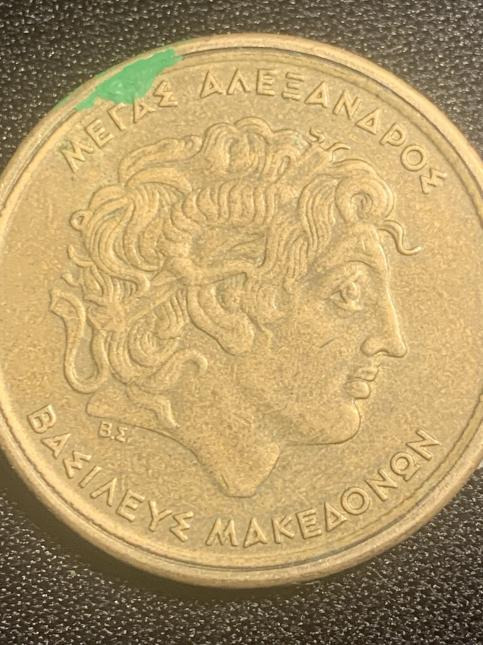

Decided to mess around and post my coin collection (27 in total):

(LONG POST)

Here's the Euros Ive got:

And then the other currencies! (Decorative souvenir coins from France, Kroner, Liras, Francs, Dirham, East Caribbean cents, Modern Drachmae and Ancient Drachmae):

My favorites include:

10 cents (2006) with the face of Venus (Italy)

1 Euro (2010) with the owl of Athena (Greece)

1 Euro (2009) with the vitruvian man (Italy)

2 Euro (2002) with the rape of Europa (Greece)

500 Liras (1987) with the face of Hermes (Italy)

100 drachmae (1990) with the face of a horned Alexander the great (Greece)

Decorative Notre Dame coin (2006)

5 cents (1984) with a curious flower-like shape (East caribbean states)

Regards the ancient drachmae, they are Emporion drachmae (3rd century replica) I bought at the Archeological musem, here's the actual coin:

These were brought to Spain by greek traders to the city of Genova, Mallorca.

The 1990 drachmae is honestly the best of the bunch, the engraving of the face is very visible and well kept except for a green paint stain and some scratches:

"Μεγασ Αλεξανδροσ, Βασιλευσ Μακεδονων" (Megas Alexandros, Vasilefs Makedonon)

Transl. Alexander The Great, Macedonian king

(If anyone who speaks greek is seeing this and I got the translation wrong IM SO SORRY grr i can understand it to a CERTAIN but LOW level)

In total I have:

11,75 euros

5 kroner

600 Liras

2 Francs

50 dirham

5 East caribbean cents

102 drachmae (Counting the older coins just by the amount i got, although im sure the value of the older drachmae would make this number less exact)

If anyone's curious the decorative coins are from the Paris Opera and Notre Dame! :) I got the opera coin because I am a huge nerd of both classic opera and The Phantom of The Opera sooo :P!

I keep them in a bag so far because I need to get a proper place to put them in, lets hope I find more silly coins to add! I almost got some roman Denarians with Caesar engravings (There was one with Hadrian) but they were abysmally expensive (The Drachmae cost 6 euros something something each, which I dont blame them, its literal SILVER. And the denarians were gold, but of course they aren't legitimately 100% gold, of course, it's a mismash of metal.) There were other coins such as golden spanish escudos from the middle ages who were 7 each, they were HUGE.

#I just really like coins guys im normal about them#I got the ancient drachmae from a museum it was awesome#they are made of silver#the crypt opens once again

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

How are you doing? I've missed your presence on this app! 😊

Ohhh hello lovely! That message means a lot to me ^_^ tbh I am in the throws of some pretty big ASD burnout and my executive function and comms have defs hit a low. But im doing okay, im currently on a weekend away and may just have the brain space to hop on HPHM and catch up on the Halloween fun.

Im hoping to be able to rejoin the tumblr fandom a little bit more as I recover xx

You wonderful people are still my favs ive just been v quietly watching from the sidelines when I have the mental spoons to hop on. Hope you are all doing well and are keeping safe:

@eternalchaoschocolaterain @alexandros-deathwood @kim-sala-bim @londonhalcyon @weirdcursedvaultkid @unoriginal2tall

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A text of G. Nagy on Herodotus as logios and the Persian logioi (with some critical remarks of mine)

“Herodotus and the Logioi of the Persians

Gregory Nagy

Short Writings: IV. Table of Contents

[This essay was originally published in No Tapping around Philology: A Festschrift in Honor of Wheeler McIntosh Thackston Jr.’s 70th Birthday (ed. A. Korangy and D. J. Sheffield) 185–191. Wiesbaden 2014. In this online edition, the original page numbers of the print edition will be indicated within braces (“{” and “}”). For example, “{185|186}” indicates where p. 185 of the print edition ends and p. 186 begins.]

The argument

In this essay, I argue that the term logioi as used by Herodotus applies not only to ‘the Persians’ but also to Greek masters of prose like Herodotus. And the word logioi, I further argue, means ‘masters of prose’, referring to the medium of Herodotus himself.

The background

At the beginning of his Histories, Herodotus says that the logioi of the Persians claim that the cause of the great conflict between the Greeks and the Persians, which is the main subject of the Histories, must be attributed to the Phoenicians—so, not to the Persians, nor to the Greeks. According to the logioi of the Persians, it was the Phoenicians who were aitioi ‘responsible’: Περσέων μέν νυν οἱ λόγιοι Φοίνικας αἰτίους φασὶ γενέσθαι τῆς διαφορῆς· ‘the logioi of the Persians say that it was the Phoenicians who were responsible [aitioi] for the conflict’ (Herodotus 1.1.1).

According to these same logioi of the Persians, Herodotus goes on to say, it was the Phoenicians who had once abducted a heroine named Io from the Greek city of Argos and brought her to Egypt (1.1.1–4). By contrast, as Herodotus emphasizes, the Greek version of the myth is different: it was the Egyptians themselves and not the Phoenicians who abducted the heroine Io from Argos and brought her to Egypt (1.2.1).

Returning to “the Persian version,” Herodotus goes on to say further that the Greeks reacted to this act of wrongdoing by abducting a heroine named Europa from the Phoenicians, specifically from the Phoenician city of Tyre (1.2.1). So the retaliation of the Greeks is symmetrical, since they abduct a heroine from the Phoenicians, not from the Egyptians, even though the Phoenicians had brought the heroine Io to Egypt and not to Phoenicia. This way, the symmetry of action and reaction sets up a rhetorical dichotomy between Europe as represented by Greeks and Asia as represented by Phoenicians, and this dichotomy is ironically made permanent by way of naming the name of the heroine who is abducted from Asia, Europa, since Herodotus bases the very concept of Europe on the name of this heroine from Asia.

So far, according to the logic of the logioi of the Persians, things are ‘even Steven’—isa pros isa, as Herodotus reports (1.2.1). But now we are about to see a new cycle of wrongful actions—and of retaliatory reactions. And, this time, it is Greeks who started it (1.2.2). If we continue to follow the logic of the logioi of the Persians, there is a wrongful action that has now been started by Europeans, not by Asiatics, and it is this: the Greeks abduct a heroine named Medea from Colchis in the Far East and bring her to a place vaguely defined as Hellas, imagined as the heartland of Europe (1.2.2–3). When the Asiatics react by demanding not only the return of the heroine Medea but also compensation for her {185|186} abduction, the Europeans refuse, offering the excuse that Hellas had never been compensated for the original abduction of the heroine Io by the Phoenicians, nor had Io been returned to Europe (1.2.3). Then, at a later time in the heroic age, the Trojan hero Paris, also known as Alexandros, abducts the heroine Helen from ‘Hellas’ and brings her to Troy in Asia; now it is the Hellenes who react by demanding not only the return of Helen but also compensation for her abduction, and now it is the Asiatics who refuse, offering the excuse that they in turn had never been compensated for the abduction of Medea by the Hellenes (1.3.1–2).

In the preceding paragraph, I must note, I have started to use the word ‘Hellenes’ instead of ‘Greeks’, following the usage of Herodotus, who has of course been using the word Hellēnes ‘Hellenes’ from the start. My reason for making this switch from saying ‘Greeks’ to saying ‘Hellenes’ will become clear in the next section.

At this point, as the report of Herodotus about the Persian version continues, the conflict between Hellenes and Asiatics escalates, since the Hellenes undertake a military expedition against Troy in order to retaliate for the abduction of Helen; and, in so doing, they commit a grave provocation (1.4.1). In Hellenic terms, of course, this expedition is the Trojan War, which is the core narrative of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey.

In Persian terms, by contrast, this expedition of the Hellenes is a grave military provocation that calls for military retaliation, and that is why the Persian Empire will launch its massive military attacks against Hellenes in Hellas. Those attacks are of course the core narrative of the Histories of Herodotus.

But here is where Herodotus starts interposing his own perspective. He notes a fundamental assumption on the part of the logioi of the Persians, which is this: Persians recognize that the abduction of women may be immoral, but they do not consider such an act to be a grave provocation that is worthy of a military expedition (1.4.2–4). And the attitude of the Phoenicians, as also described by Herodotus, is even more pronounced: this attitude, expressed presumably by their own logioi, is that Io, the first woman to be abducted in this chain reaction of abductions, was not really abducted but rather had intercourse willingly with the captain of the Phoenician ship; when she got pregnant, she was ashamed to tell her parents and willingly sailed away to Egypt along with the Phoenicians (1.5.1–2). And here we see a big difference between the Hellenes on one side and the Persians and Phoenicians on the other: the Hellenes do consider the abduction of women to be a grave provocation that calls for the waging of war. That is why, ostensibly, the Hellenes escalated the hostilities. And it is this war, according to the logioi of the Persians, that ultimately justified the war about to be waged by the Persian Empire against to Hellēnikon ‘the Hellenic thing’ (1.4.4).

European Greeks and Asiatic Greeks

In this new section, I have reached the point where I can explain why I started saying ‘Hellenes’ instead of ‘Greeks’ in the previous section. Herodotus, in reporting the argumentation of the logioi of the Persians about the hostilities between the Hellenes on one side and the Persians along with the Phoenicians on the other side, speaks of these hostilities in terms of an opposition between Europeans and Asiatics (1.4.1, 3–4). Our first impression is that Hellenes were all Europeans while non-Hellenes were all Asiatics. But {186|187} what about all the people who spoke the Greek language in places other than European Hellas? I am thinking here especially of the Greeks in Asia Minor and in such major outlying islands as Chios and Samos. For the moment, let me refer to these Greeks by using the blanket term ‘Asiatic Greeks’. In terms of the formulation made by the logioi of the Persians, as reported by Herodotus, these Asiatic Greeks are not Hellenes. They are Asiatics, just like the Persians and the Phoenicians. In terms of this same formulation, it is only the Greeks of the Helladic mainland, that is, of Hellas, who are Hellenes. [1]

From the pluralistic standpoint of the Persian Empire, the Greeks of Asia Minor and of the outlying islands were not Hellenes but Aeolians, Ionians, and Dorians. I list these Asiatic Greeks here in roughly geographical order, proceeding from north to south. And the same nomenclature applies in the earlier era of the Lydian Empire, superseded later by the Persian Empire. When Herodotus gives his own explanation of the causes of the great conflict between Greeks and Persians (1.5.3–1.6.3), he actually starts with the Lydian Empire in general and with the Lydian king Croesus in particular: it was this Croesus, Herodotus reports, who first succeeded in subjugating the Ionians and the Aeolians and the Dorians ‘in Asia’ (1.6.2). The historian evidently lists these Asiatic Greeks here in order of political and cultural importance, and the Ionians take pride of place.

But it is anachronistic for Herodotus to refer to the Asiatic Ionians and Aeolians and Dorians as ‘Hellenes’ in the historical context of the era when the states of these Greeks were tributaries of the Lydian Empire (1.5.3, 1.6.2, 1.6.3)—even if the term surely applies in the context of the later era when these same Greek states became tributaries of the Athenian Empire. In other work, I analyze in some detail the proleptic references of Herodotus to the Athenian Empire as a successor to the Persian Empire and to the earlier Lydian Empire in dominating the Ionians and Aeolians and Dorians of ‘Asia’ after the victory of the Hellenes over the forces of the Persian Empire in 480 and 479 BCE. [2] Here, I simply insist on the anachronism of applying the term ‘Hellenes’ to the Asiatic Greeks at a time when the Persian Empire was waging war against the Athenians and other fellow ‘Hellenes’, as they called themselves.

Herodotus is in fact quite cautious in his attempts to steer clear of the term ‘Hellenes’ with respect to the countless Asiatic Greeks who had been recruited by the Persian Empire to fight against the European Greeks—that is, against the Athenians and other ‘Hellenes’ on the Helladic mainland whose states had not already chosen to side with the Persians. In his description of the naval battle of Salamis, for example, where the navy of the Persian Empire was comprised of a massive number of Ionians as well as Phoenicians and other non-Greeks, Herodotus finds ways to maintain a distinction between the ‘Hellenes’ on one side and the ‘Ionians’ on the other side of the sea battle (the most telling passages are at 8.10.2 and 8.90.1). {187|188}

The logioi of the Persians and Herodotus as logios

Given that the Asiatic Greeks were part of the Persian Empire during the war narrated by Herodotus, I argue that the logioi of the Persians were not Persians themselves but Asiatic Greeks who represented the world view of the Persian Empire, just as the Asiatic Greeks who fought for the Persian Empire in the war narrated by Herodotus must have called themselves not ‘Hellenes’ but Ionians or Aeolians or Dorians and so on. I link this argument with another argument, developed in earlier work. [3] In terms of this other argument, Herodotus too considered himself a logios. In linking these two arguments, I find it relevant to highlight the fact that Herodotus of Halicarnassus was an Asiatic Greek in his own right. And his symbolic filiation may have been Doric, though his language of public discourse was Ionic. So, yes, Herodotus too was an Asiatic Greek. But here is the big difference. Herodotus was not a logios of the Persians; rather, he was a logios of the ‘Hellenes’.

In order to pursue this line of argumentation, I start with the traditional form of Herodotean discourse, which can be described as prosimetrum. [4] By using this term, I mean that the medium of Herodotus can feature poetry—especially oracular poetry—framed within prose. More frequently, however, the poetry framed within the prose of Herodotus is also turned into prose, along the lines of the Life of Aesop tradition, where the fables embedded within the prose that tells the life of Aesop represent a poetic medium that has been turned into prose. [5] For example, Herodotus turns into prose the sayings of Solon, who figures as the most eminent of the Seven Sages in the poetic tradition that records their sayings, and the historian embeds these sayings within the framing prose narrative of the Histories. [6]

Here I repeat a point I have made in earlier work on the similarities between the media of Herodotus and Aesop. [7] These similarities are noted by Plutarch in his essay On the Malice of Herodotus (871d), where he notes wryly that the big difference between Herodotus and Aesop is that, whereas the fables of Aesop present us with talking apes and ravens, the Histories of Herodotus show more elevated talking characters who include not only humans such as Scythians, Persians, or Egyptians, but even the god Apollo himself in the act of speaking his oracular poetry. [8] The talking humans in this negative reference correspond to characters in a genre of fable known as Subaritikoi logoi ‘discourse from Sybaris’. As we learn from the scholia for the Birds of Aristophanes (471), Sybaritic fables are distinct from Aesopic fables in that they feature talking humans as the main characters, not talking animals. [9]

In the case of Plutarch’s comment about the talking characters of Herodotus, I draw attention to the fact that Plutarch here highlights Scythians, Persians, and Egyptians rather than {188|189} ‘Hellenes’. [10]

The negative implication is that Herodotus is disingenuously applying to non-Hellenes what really applies to Hellenes. As I have argued, however, such a strategy of indirect application is what Herodotus himself had really intended: what is disingenuousness for Plutarch is in fact a refined sense of diplomatic strategy for Herodotus. [11]

The diplomacy of Herodotus in the use of ainoi as fables is a topic that I have explored at length in previous work. [12]

And I will explore it further in a future project “Homo ludens and the Fables of Aesop,” especially with reference to the elements of fable inherent in the story of Hippokleides in Herodotus (6.126–130), which are cognate, in my view, with the elements of the fable of “The Dancing Peacock” as attested in the Indic Jātakas. [13]

The point I made earlier about the diplomatic use of ainoi as fables by Herodotus, where the speaking characters may be Scythians, Persians, or Egyptians even though the intended listeners are in fact ‘Hellenes’, is relevant to the use of the word logios by Herodotus, which we can translate loosely as ‘master of speech’ when it is a noun and ‘expert in speech’ when it is an adjective. [14]

That said, I return to my argument that Herodotus is a logios. This word logios, in terms of the argument, is applicable to Herodotus in his capacity as a master of prose performance. I say applicable, not applied, because Herodotus (1.1.1) applies the word not to himself but to those who identify themselves with the Persians, not with the Hellenes, and who are therefore representatives of a world view that is different. Examining all the Herodotean contexts of the word logios (1.1.1, 2.3.1, 2.77.1, 4.46.1), I argue that logioi are masters of discourse about different world views as represented by Persians (1.1.1), Egyptians (2.3.1, 2.77.1), and Scythians (4.46.1). [15] In terms of my argument, then, this word logios could apply only implicitly to Herodotus as a Hellene but it applies explicitly to non-Hellenes, just as the ainoi or fables of Herodotus could apply only implicitly to Hellenes but explicitly to Persians, Scythians, or Egyptians. [16]

In support of my argument that the term logios in the sense of ‘master of speech’ applies implicitly to Herodotus himself, I highlight the parallel semantics of the word logopoios ‘artisan of speech’, which Herodotus actually applies to Aesop himself (2.134.3), to be contrasted with the word mousopoios ‘artisan of song’, which he applies to Sappho (2.135.1). [17] As in the case of the word logios, Herodotus does not apply the word logopoios to himself, but he does in fact apply it to another Asiatic Greek who happens to be his rival, the historian Hecataeus of Miletus (2.143.1, 5.36.2, 5.125). By implication, then, Herodotus is a logopoios, an ‘artisan of speech’, just like Hecataeus. [18] And, as a logopoios, Herodotus is even like Aesop. {189|190}

In short, I interpret the word logios in the sense of a ‘master of speech’ to refer to mastery of prose in contrast to song, just as the word logopoios ‘artisan of speech’ as applied by Herodotus to Hecataeus refers to mastery of prose in contrast to the word mousopoios ‘artisan of song’ as applied to Sappho, which refers to mastery of song. [19]

Conclusion

As I think back to the stories about the abductions of women as retold by Herodotus in the initial paragraphs of his Histories, I find there was an element of playfulness in the way he retells those stories, though of course the consequences of the storytelling lead to historical events that are very serious. Such playfulness reflects a delight in mimesis, which has the power to re-enact forms of verbal art that range from the fables of Aesop all the way to narratives about grim wars that determined the course of history. The war, recounted by Herodotus, was of course won by ‘Hellenes’, who made their name stick, especially in the context of the Athenian Empire. If the war had been won by the Persians, however, I doubt that Greek-speaking people would have persisted in calling themselves ‘Hellenes’. My guess is that they would call themselves Ionians. The Persians still call them that. {190|191}

Bibliography

Asheri, D., A. Lloyd, and A. Corcella. 2007. A Commentary on Herodotus Books I-IV (ed. O. Murray and A. Moreno; translated by B. Graziosi et al.). Oxford.

Kurke, L. 2011. Aesopic Conversations: Popular Traditions, Cultural Dialogue, and the Invention of Greek Prose. Princeton.

Luraghi, N. 2009. “The Importance of Being λόγιος.” Classical World 102:439-456.

Maslov, B. 2009. “The Semantics of ἀοιδός and Related Compounds: Towards a Historical Poetics of Solo Performance in Archaic Greece.” Classical Antiquity 28:1-38.

Nagy, G. 1990. Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore, MD.

Nagy, G. 2009. “Hesiod and the Ancient Biographical Traditions.” Brill’s Companion to Hesiod (ed. F. Montanari, A. Rengakos, and C. Tsagalis) 271–311. Leiden.

Nagy, G. 2011a. “Asopos and his multiple daughters: Traces of preclassical epic in the Aeginetan Odes of Pindar.” Aegina: Contexts for Choral Lyric Poetry. Myth, History, and Identity in the Fifth Century BC (ed. D. Fearn) 41–78. Oxford.

Nagy, G. 2011b. “Diachrony and the Case of Aesop.” Classics@, Issue 9, “Defense Mechanisms.”

Footnotes

[back] 1. On the politics of the term ‘Hellene’ (Hellēn) in its earliest phases, I offer an analysis in Nagy 2009:274–275. On the politics of the same term in its later phases, I offer further comments in Nagy 2011a:54n32, with references to recent discussions.

[back] 2. Nagy 1990:229–231 = 8§§22–23

[back] 3. Nagy 1990:221–225 = 8§§8–14; for background, see Asheri et al. 2007:74.

[back] 4. Nagy 2011b §§124, 133–134, 151–153.

[back] 5. Nagy 2011b §153.

[back] 6. Nagy 1990:248 = 8§50; 332 = 11§32.

[back] 7. Nagy 2011b §154.

[back] 8. Nagy 1990:332 = 11§19; 334 = 11§35.

[back] 9. Nagy 1990:324–325 = 11§21; 334–335 = 11§35.

[back] 10. Nagy 2011b §155.

[back] 11. Nagy 1990:324–325 = 11§21n59.

[back] 12. Nagy 1990 ch. 11.

[back] 13. I disagree here with Kurke 2011:417, who thinks that the Greek version of the story was somehow borrowed from the Indic version.

[back] 14. Nagy 2011b §157.

[back] 15. I offer a short commentary on these Herodotean passages in Nagy 1990:224 = 8§13n54.

[back] 16. Nagy 2011b §159.

[back] 17. Nagy 1990:224 = 8§13n54.

[back] 18. Nagy 1990:324–325 = 11§21

[back] 19. Nagy 2011b §160. There I highlight the attestation of an explicit contrast between logioi ‘masters of speech’ and aoidoi ‘singers’ in a song of Pindar (Pythian 1.92–94), where the word logioi occurs in a phraseological context that is parallel with what we find in Herodotus (1.1.1). There are also examples of logioi in other songs of Pindar (Nemean 6.45, Pythian 1.92–94) where the word occurs in phraseological contexts that are once again parallel to what we find in Herodotus (1.1.1). My synchronic study of the linguistic evidence showing collocations of these words in their attested contexts was the basis for my arguing, from a diachronic point of view, that these contexts are cognate with each other (Nagy 1990:221–225 = 8§§8–14). In Nagy 2011b (especially §161), I criticize what Kurke 2011 as well as Maslov 2009 and Luraghi 2009 have to say in their interpretations of the relevant Pindaric passages.”

Source: https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-herodotus-and-the-logioi-of-the-persians/

Gregory Nagy (Hungarian: Nagy Gergely, pronounced [ˈnɒɟ ˈgɛrgɛj]; born Budapest, October 22, 1942)[1][2] is an American professor of Classics at Harvard University, specializing in Homer and archaic Greek poetry. Nagy is known for extending Milman Parry and Albert Lord's theories about the oral composition-in-performance of the Iliad and Odyssey (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregory_Nagy

Gregory Nagy is an eminent classicist and this article of his is for sure thought provoking.

I remark, however, that λόγιος is in Greek the learned person or the scholar, not specifically the “master of prose”.

It is of course important that Herodotus records in the beginning of his Histories what the “learned among the Persians” reported about the origins of the hostility between “Asia” and Greece, presenting in this way the Persian version about the responsibility for the Greco-Persian wars. I believe that Herodotus’ sources on the views of the “learned Persians” on this matter must have been Greeks having worked for the Persians or hellenized Persians living in Asia Minor.

However, what is far more important is that Herodotus in a revolutionary move eventually dismisses such researches in the mythological past as beyond verification and starts his account of the Greco-Persian conflict and its causes with a historical person, namely Croesus of Lydia, whose misguided pre-emptive attack on the emerging Persian empire and his defeat by Cyrus the Great put an end to the Lydian state and brought Persians and Greeks in contact for the first time, with the Persian conquest of the Greek colonies in Asia Minor.

Moreover, I don’t find particularly fortunate Nagy’s comparison of Herodotus with Aesop, as we are talking about the representatives of two very different literary genres. I add that the authenticity of the anti-Herodotus diatribe On the Malice of Herodotus as work of Plutarch is not beyond doubt and that, anyway, this diatribe is mainly an apology for the Boetian aristocracy and its collaboration with the Persians during Xerxes’ invasion (although the author of the On the Malice... combines the defense of his pro-Persian ancestors with claims that Herodotus would have been “philobarbaros”-”barbarian lover”!).

I remind also that the Ionians were one of the four major Greek (Hellenic) “tribes” (alongside the Dorians, the Achaeans, and the Aeolians) and that Dorians and Aeolians too had established colonies on the coast of Asia Minor (Herodotus’ hometown -Halicarnassus- was a Dorian colony). Now, I fail to see how and why, in the case of Persian conquest of mainland Greece, the Dorians or the Aeolians or the Achaeans would have identified themselves as Ionians, not as Hellenes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

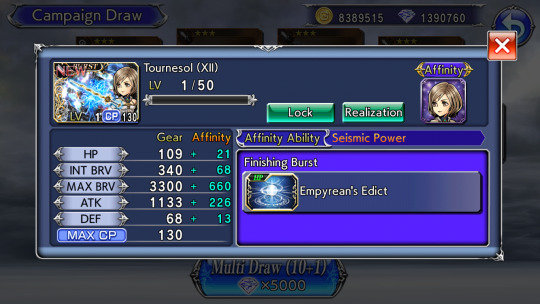

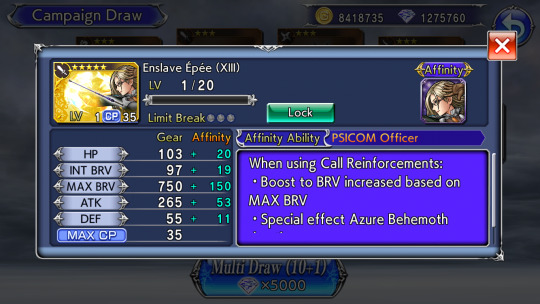

Dissidia Final Fantasy: Opera Omnia Special Title Draw Banners Gems Pulls Results Part 2

The Special Title Draw banners just showed up in the Dissidia Final Fantasy: Opera Omnia (DFFOO) mobile game.

Sadly, the reason why these banners showed up is because DFFOO just announced that it will discontinue or end its service on February 29, 2024.

That announcement came as a shock. Really wish that wasn’t true. Wish the game wasn’t ending at all.

I talk more about that in another post. In this post, will talk about the results of my gem pulls on the Special Title Draw banners.

This is actually a continuation of another post. Had to split the posts since the 1st one or part 1 already reached the max limit of 30 pics per post.

Special Title Draw Banners Information

There are a total of 7 Special Title Draw banners. All the weapons that have been released up through November 21, 2023 will be available in these banners.

Special Title Draw Banner 1 features all the weapons of chars from Final Fantasy I, Final Fantasy XV, and Final Fantasy Type-0.

Special Title Draw Banner 2 features all the weapons of chars from Final Fantasy II and Final Fantasy VII.

Special Title Draw Banner 3 features all the weapons of chars from Final Fantasy III, Final Fantasy VIII, and Final Fantasy X.

Special Title Draw Banner 4 features all the weapons of chars from Final Fantasy IV, Final Fantasy XIV, and Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles.

Special Title Draw Banner 5 features all the weapons of chars from Final Fantasy V, Final Fantasy XIII, and Stranger of Paradise: Final Fantasy Origin.

Special Title Draw Banner 6 features all the weapons of chars from Final Fantasy VI, Final Fantasy XI, and Final Fantasy Tactics.

Special Title Draw Banner 7 features all the weapons of chars from Final Fantasy IX, Final Fantasy XII, and World of Final Fantasy (#ad).

Special Title Draw Banners Gems Pulls Results

Here are the results of my gem pulls on the Special Title Draw banners. Have a million+ gems, and a lot of my pulls just give me the usual bronze and silver trash and gold dupe/s.

As such, decided to only take a screenshot if I get a Force (FR) weapon and/or a Burst (BT) weapon regardless of if it’s new or a dupe. Will also take a screenshot if I actually get something new or something I haven’t fully max limit broken yet even if it isn’t a FR and/or BT.

Will also take screenshots if I get an interesting enough draw like if an unusually high number of golds shows up or something.

A force orb gave me a dupe of Lann & Reynn’s (from World of Final Fantasy) FR.

My 1st copy of this hasn't been limit broken at all.

A Burst orb didn't show up so was pleasantly surprised when this pull gave me my very 1st copy of Ashelia B'nargin Dalmasca's (from Final Fantasy XII) BT.

This draw also gave me dupes of Enna Kros's (from World of Final Fantasy) Ex and Gabranth's (Noah fon Ronsenburg from Final Fantasy XII) 35cp.

Got another dupe of Lann & Reynn's FR.

Got dupes of Cid Raines's (from Final Fantasy XIII) FR and Sazh Katzroy's (from Final Fantasy XIII) 35cp.

Got my 1st copy of Faris Scherwiz’s (Sarisa Scherwil Tycoon from Final Fantasy V) FR from a force orb.

This pull also gave me a dupe of Noel Kreiss's (from Final Fantasy XIII) Ex.

Got dupes of Kuja's (from Final Fantasy IX) LD, Garnet Til Alexandros XVII's (from Final Fantasy IX) FR, and Basch fon Ronsenburg's (from Final Fantasy XII) Ex.

Got a dupe of Enna Kros's FR.

Got a dupe of Noel's BT.

Got dupes of Exdeath's (from Final Fantasy V) Ex as well as a 15cp dupe.

My 1st copy of Exdeath's Ex hasn't been limit broken yet.

A force orb gave me a 15cp dupe as well as a dupe of Penelo's (from Final Fantasy XII) FR.

Got a 15cp dupe as well as dupes of Galuf Halm Baldesion's (from Final Fantasy V) 35cp, Neon’s (from Stranger of Paradise: Final Fantasy Origin) 35cp, and Jihl Nabaat's (from Final Fantasy XIII) 35cp.

My 1st copy of Nabaat's 35cp has been limit broken once.

A force orb gave me my 1st copy of Reks's (from Final Fantasy XII) FR.

This pull also gave me a 15cp dupe as well as dupes of Enna Kros's Ex and Eiko Carol's (from Final Fantasy IX) Ex.

Got a dupe of Edward Chris von Muir's (from Final Fantasy IV) Ex.

My 1st copy of this has been limit broken twice so this dupe will finally let me fully MLB this weapon.

A force orb gave me dupes of Reks's Ex, Quina Quen's (from Final Fantasy IX) FR, Lann & Reynn's 15cp, and Vivi Ornitier's (from Final Fantasy IX) Ex.

My 1st copy of Reks's Ex hasn't been limit broken at all.

Got dupes of Cid Raines's FR and Dorgann Klauser's (from Final Fantasy V) Ex.

And that’s it. For this post, at least. There’s a lot more but gonna have to talk about the results of the rest of my Special Title Draw banners gem pulls in another post since already reached the max limit of 30 pics in this one.

Conclusion

So what about you? What do you think about the news that DFFOO is ending its service on February 29, 2024? Did you pull on any of the Special Title Draw banners? Feel free to share your thoughts and opinions by leaving a comment below or by reblogging or replying to this post.

Notes:

screenshots are from my Dissidia Final Fantasy: Opera Omnia game account

#dissidia final fantasy opera omnia#pulls for these chars:#cid raines#jihl nabaat#enna kros#ashelia b'nargin dalmasca#dorgann klauser#galuf halm baldesion#noel kreiss#quina quen#lann & reynn#and more#games#gacha games#mobile games#dffoo#dffoo gem pulls#dffoo banner pulls

0 notes

Text

Opera Omnia Burst Themes 1/?

With Opera Omnia shutting down, I decided to make a few posts about one of my favorite parts of the game: The Burst Weapons. Not because they were a powerful, much sought after weapon tier that gave big numbers with massive benefits, but because I have a love for Final Fantasy music, and what BTs I wanted was strongly dependent on what song would play when used.

These posts are meant to be more for the sake of archiving what there had been more than anything else, but at the very least I am going to list a large number of great FF songs.

The first listing will be the songs that we had gotten during the game's lifetime.

Final Fantasy I

Warrior of Light: Battle

Garland: Miniboss Theme

Final Fantasy II

Firion: The Rebel Army

Leon: The Imperial Army

Minwu: Battle Theme A

Final Fantasy III

Onion Knight: Battle 2

Cloud of Darkness: This is The Last Battle

Final Fantasy IV

Cecil Harvey (Dark Knight): The Red Wings

Cecil Harvey (Paladin): Battle 2

Kain Highwind: The Final Battle

Rydia: Rydia's Theme

Rosa Joanna Farrell: Theme of Love (Remake)

Fusoya: The Final Battle (Remake)

Golbez: Battle with the Four Fiends

Rubicante: Battle with the Four Fiends (Remake)

Ceodoe Harvey: Battle 2 (Remake)

Ursula: Fabul (Remake)

Leonora: Troian Beauty

Final Fantasy V

Bartz Klauser: Battle 2

Faris Scherwiz: Pirates Ahoy!

Lenna Charlotte Tycoon: Lenna's Theme

Dorgann Klauser: Home, Sweet Home

Kelgar: Deception

Xezat: Castle of Dawn

Gilgamesh: Battle on the Big Bridge

Exdeath: The Final Battle

Final Fantasy VI

Terra Branford: The Decisive Battle

Locke Cole: Locke's Theme

Sabin Rene Figaro: The Unforgiven

Setzer Gabbianni: Setzer's Theme

Edgar Roni Figaro: Edgar & Sabin's Theme

Celes Chere: Searching For Friends

Relm Arrowny: Relm's Theme

Mog: Protect the Espers

Strago Magus: Strago's Theme

Leo Cristophe: Battle Theme

Kefka Palazzo: Dancing Mad

Final Fantasy VII

Cloud Strife: Fight On!

Tifa Lockhart: JENOVA COMPLETE

Yuffie Kisaragi: Wutai

Vincent Valentine: Chaotic End

Aerith Gainsborough: Aerith's Theme

Cait Sith: Cait Sith's Theme

Jesse Rasberry: Let the Battles Begin!

Sephiroth: One-Winged Angel

Zack Fair: The Price of Freedom

Cissnei: Ecounter

Angeal Hewley: Dreams and Honor

Reno: Turk's Theme

Rufus Shinra: Shinra Inc

Kadaj: J-E-N-O-V-A (Advent Children)

Weiss: Fight Tune: Weiss the Immaculate

Final Fantasy VIII

Squall Leonhart: Force Your Way

Laguna Loire: The Man with the Machine Gun

Irvine Kinneas: The Stage is Set

Quistis Trepe: Don't Be Afraid

Selphie Tilmitt: Where I Belong

Rinoa Heartilly: Premonition

Fujin: Only a Plank Between One and Perdition

Ultimecia: The Extreme

Final Fantasy IX

Zidane Tribal: Not Alone

Vivi Ornitier: Breaking Through the South Gate

Garnet Til Alexandros XVII: Alexander

Eiko Carol: Eiko's Theme

Quina Quen: Quina's Theme

Amarant Coral: Amarant's Theme

Kuja: Dark Messenger

Beatrix: Something to Protect

Final Fantasy X

Tidus: Battle Theme

Yuna: A Contest of Aeons

Auron: This is Your Story

Braska: Final Battle

Seymour Guado: Battle with Seymour

Jecht: Otherworld

Paine: Yuripa, Fight! No. 2

Next Entry

1 note

·

View note

Text

hope everyone has to gather together and be like "how are we going to free anduin from the jailer???" and alexandros just goes "i mean. king varian is dead. just go find his soul and tell him about anduin."

"how does that help?"

"what do you mean?"

"what would varian do about it?"

"what w—? you don't have kids, do you?"

#alexandros: why are you confused ive literally done this before#warcraft#alexandros#anduin#shadowlands

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy International Women’s Day 2020 ♥ (insp.)

#ffgraphics#final fantasy#lightning farron#tifa lockhart#aerith gainsborough#lunafreya nox fleuret#celes chere#yuna#rinoa heartilly#garnet til alexandros#terra branford#rydia of mist#fran#aranea highwind#my edit#iv#vi#vii#viii#ix#x#xii#xiii#xv#ffgifs#ffedit#final fantasy iv#final fantasy vi#final fantasy vii#final fantasy viii

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Summoners throughout Final Fantasy

#graphics#ffgraphics#thechocobros#final fantasy iv#final fantasy ix#final fantasy x#final fantasy x2#rydia#garnet til alexandros#eiko carol#yuna#lenne#ffx#ffiv#ffix#ffx2#final fantasy#finalfantasyedit#final fantasy edit#mine#mygifs#mygif#my gifs#my gif#summoners#i love that all the summoners in the series are women

798 notes

·

View notes

Photo

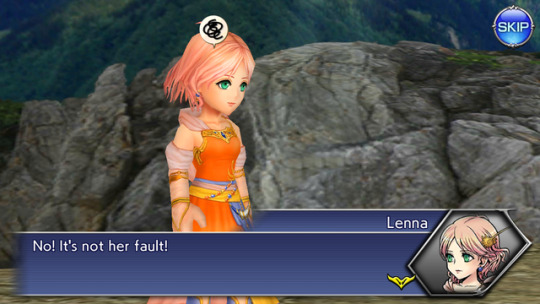

Event/Lost Chapters Characters Part 3

Princess of Alexandria - Garnet a.k.a. Dagger

Raise the Runic Blade - Celes

The Proud Lance of Baron - Kain

Taking the Gods’ Stage - Kuja (a.k.a. grand winner of the first early release character poll)

A Mischievous Black Mage - Palom

The Beautiful Archeress - Maria

Balamb Whiplash - Quistis (a.k.a. 1st runner-up of the first early release character poll)

One-Winged Angel - Sephiroth (a.k.a. grand winner of the second early release character poll)

A Devoted Heart - Lenna (a.k.a. 2nd runner-up of the first early release character poll)

Space Dreams - Cid [Highwind] (a.k.a. 2nd runner-up of the second early release character poll)

I know, some of these have obvious dialogue, but I hope their Lost Chapters-exclusive scenes will have stuff of just them without text boxes.

Event/Lost Chapters Characters Part 1

Event/Lost Chapters Characters Part 2

Event/Lost Chapters Characters Part 4

Event/Lost Chapters Characters Part 5

Event/Lost Chapters Characters Part 6

Event/Lost Chapters Characters Part 7

#final fantasy#dissidia final fantasy#dissidia final fantasy opera omnia#character events#final fantasy ix#garnet til alexandros xvii#dagger#kuja#final fantasy vi#celes chere#final fantasy iv#kain highwind#palom#final fantasy ii#maria#final fantasy viii#quistis trepe#final fantasy vii#sephiroth#cid highwind#final fantasy v#lenna charlotte tycoon#lost chapters

23 notes

·

View notes