#black communities

Text

https://x.com/Phil_Lewis_/status/1703407420515442919?t=KZA9wU6ZOvHpoTyQobuXKQ&s=09

For over 230 years, Gullah-Geechee people called Georgia's Sapelo Island home County commissioners voted to remove zoning restrictions & to strike language stating it should prevent “land value increases which could force removal of the indigenous" folk

For more than 230 years, a small community of Gullah-Geechee people have called Sapelo Island off the coast of Georgia home. Hogg Hammock, the area on the island where these descendants of enslaved people live, is a 427-acre coastal community of 40 residents and has been designated as a historic site since 1996. That means that the construction of houses more than 1,400 sq ft and any road paving or demolition of property are strictly prohibited to preserve the island community.

On Tuesday, McIntosh county commissioners, who preside over Sapelo, voted to remove zoning restrictions in Hogg Hammock. Gullah-Geechee residents fear that wealthy transplants who want to develop larger homes and who could force a rise of property taxes there will displace them and upend their livelihoods.

The county, which is 65% white, has voted to remove official language that acknowledges Hogg Hammock as an area with “unique needs in regard to its historic resources”. It will also strike language that states it should prevent “land value increases which could force removal of the indigenous population”.

Last Thursday, dozens of residents gave hours of testimony to the county’s zoning board arguing against the proposed changes, warning that the county had hastily made changes without community consideration. Reginald Hall, a landowner whose family had roots in Hogg Hummock, told the Associated Press the county’s approval would amount to “the erasure of a historical culture that’s still intact after 230 years”.

Residents and state lawmakers called for the county to delay their vote and to reflect on proposed changes for 90 days. “We will not allow our cultural history to be erased or bought at the price of land developers,” the state representative Kim Schofield, who represents Atlanta, told reporters. “This is our history and our heritage, and we will fight to protect it.”

Hall warned the county’s vote to remove development limits would give Gullah -Geechee residents in Hogg Hammock just “two to three years at most” to survive in the county before they scatter elsewhere, as 200,000 Gullah-Geechee people have already done across the south-eastern corridor of the United States. “If you talk about the descendants of the enslaved,” she said, “90% of us will be gone.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The white mob that held Memphis in terror for three terrible days in May 1866 targeted black churches for destruction. They burned wood frame buildings and ruined even a large brick church building. According to the Congressional inquiry into the massacre, the mob destroyed every black church in Memphis. The Congressional report recounted the testimony of preachers from African American churches whose lives had been threatened by white residents during and after the massacre.

Why would the white mob deliberately target black churches during the Memphis massacre? What did these churches represent – both to formerly enslaved Memphians and to white Memphians? How did black churches support African Americans’ struggle for civil and political rights in the post-emancipation South?

Slave Religion & Emancipation

Christianity had a long, complex history among American slaves. Historian Albert Raboteau’s classic Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South charted this history nearly forty years ago. He showed that despite slaveholders’ efforts to teach a version of Christianity centered on obedience to masters, slaves created complex religious cultures combining African religious retentions and Christian practices. Raboteau concluded with the observation of African American theologian Howard Thurman that, “By some amazing but vastly creative spiritual insight, the slave undertook the redemption of a religion that the master had profaned in his midst.” On the eve of emancipation, slave religion had become a vital cultural force, insisting on the humanity of those caught in the dehumanizing system of slavery. As spirituals – the theological writings of slaves – maintained, the God who brought the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt, destroyed the walls of Jericho, and protected Daniel in the lion’s den would upend the social order to free American slaves from bondage. Enslaved Christians worked for and longed for that divinely directed emancipation.

When the Civil War came to the Mid-South, black Christians recognized it as an opportunity for their exodus from slavery. On a West Tennessee farm, Isaac Lane, a slave preacher who would later found Lane College, led prayer meetings of fellow slaves praying that the Civil War would bring emancipation. Local whites badly beat Lane when they learned of his prayer meetings. This violence testified to the strong potential for liberation that white southerners recognized in black Christianity.

With emancipation, African Americans rapidly formed their own churches. Antebellum southern churches had contained several hundred thousand enslaved members. Once free, these black Christians left white-controlled churches, much to the surprise of white Christians who did not understand why former slaves would not want to remain as second class members in segregated balconies. Freed people across rural areas and towns built rough church buildings almost overnight, despite the poverty they endured. These churches hosted day, night, and Sunday schools for black adults and children, often with support from northern missionary groups.

Churches supported black southerners’ claims for civil and political rights as citizens at a time when those rights were deeply contested. For that support, black churches earned white southerners’ criticism – and violence.

Black Churches and Citizenship

After emancipation, there were many unanswered questions about African Americans’ place in the newly reunited nation. What civil or political rights could they exercise? Would free blacks be equal citizens with white Americans? Black churches supported African Americans’ claims for civil and political rights by hosting political gatherings and mass meetings and by allowing black southerners to claim an important common identity with local whites as fellow Christians.

In the infamous Dred Scott decision in 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that people of African descent, whether slave or free, were not citizens of the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment would overrule that decision, declaring that all persons born in the U.S. were citizens, but that amendment would only be ratified two years after the Memphis Massacre. Even if it were granted, what citizenship meant was also uncertain. Women’s presence as citizens who could not vote showed that citizenship did not guarantee equal political rights.

The Congressional Report on the Memphis Massacre talked of the “citizens” of Memphis as its longtime white residents. The document implicitly excluded newly-arrived northern whites and black residents when it spoke of the “citizens” who shaped public opinion in Memphis. Both access to citizenship and the rights that came with citizenship proved a shifting ground in the post-emancipation South.

Because citizenship was such an uncertain category, identity as Christians became all the more important for black Memphians – and other former slaves – as they sought to assert their civil and political rights. Insisting that they were fellow Christians with their white neighbors was an important way for black Memphians to assert themselves as equal to whites. While racial identity was a fixed, rigid category, religious identity could change. Southern preachers had long stressed that Christian conversion was available to all, whether slave or free, black or white. The more fully that black residents could insist that Christian identity should signify who belonged in Memphis, the more they could put themselves in that category of belonging. Religious identity gave black Memphians a malleable category to use instead of the fixed categories of race that excluded them from whiteness and from citizenship.

In making these claims, Memphis’ black community drew upon the widely accepted valued of Christian identity and behavior. As Major Gen. George Stoneman worked to restore order after the massacre, he wrote that Memphians must “govern themselves as a law-abiding and Christian community.” Missionary teachers from northern states interviewed after the massacre explained that they were working for the “education and Christianization” of black Memphians. The 1866 report makes clear that Christian behavior was a widely accepted goal. Black Memphians’ insistence that their Christian identity made them worthy of civil and political rights alongside white residents proved a savvy, effective strategy. But these efforts were also a consistent interpretation of generations of black Christianity.

In May 1866, black churches were full of Memphians who had long prayed that the God who had brought the ancient Israelites out of slavery in Egypt would free them from the horrors of the South’s peculiar institution. The churches held schools, community meetings, and political rallies in addition to their religious services. Churches helped black Memphians try to claim an equal status as fellow Christians with white southerners.

The white mob that targeted black churches during the Memphis massacre would not have done so by chance or by mistake. White Memphians knew that black churches occupied a central place in the black community’s quest for civil and political rights. Destroying all of Memphis’ black churches showed the mob’s effort to destroy the black community’s hope, their schools, their political advocacy, and their meeting places.

Fortunately, the mob did not have the final word. Within months, black churches would be rebuilt and would again be filled day and night with schools and religious services. They would continue to serve as centers for community organizing and political action. And they would continue to insist that black and white Memphians, as fellow Christians, deserved equal civil and political rights.

#tennessee#memphis#white hate#white supremacy#Black Churches#Black Communities#Why Did White Mobs Burn Black Churches in the Memphis Massacre#Freedmen#1866

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

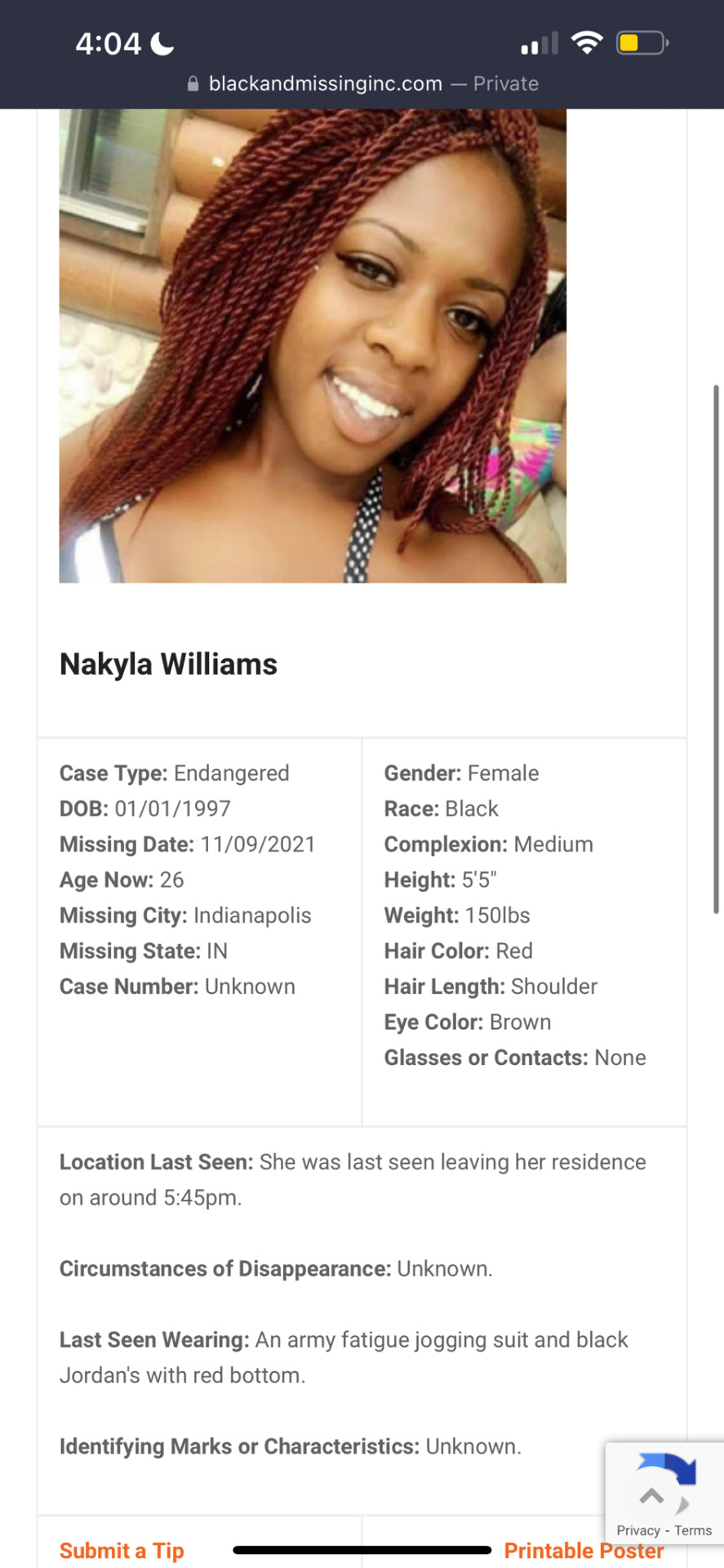

This is a prime example of why mental health is so on edge … just one example. I can’t get the link to work so I screenshot it, and linked below in case it works somehow for you SPREAD THIS!! BLACK WOMEN ARE BEING TARGETED

If we don’t act no one will.

Try this site , I can’t get it to post properly

Please share !!!!

#missing and black#black women#black woman#blacklivesmatter#protect black women#black community#black communities#black females#black female#black womens lives matter#black women in danger#black and missing#missing person#missing black woman#black and missing foundation#black power#black tumblr#black lives matter#blm#black liberation#black people#amber alert

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since it’s not letting me post the damn link to this missing Black woman, here’s a screenshot _ shareplz !!

Here’s the link if it works 😰

#black women#protection#protect black women#blacklivesmatter#black females#black woman#blackgirlmagic#black women appreciation#black community#black communities#black men protect black women#missing person#missing persons#black and missing#missing and black

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dance is an Essential Part of African American Culture.

African culture and traditions Florida is a collection of practices and traditions developed from a difficult beginning. Partner dance, accompanied by soulful music and clothing, is integral to our mental health.

#African culture and traditions Florida#Black communities#African American culture#African ancestors’ tribal dances#african american heritage#african diaspora jobs florida#Fatherland Florida

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medical Pearls: Hypertension In Black People

Hypertension (HTN) is particularly prevalent among Black communities and families, and effective management is crucial, as untreated or poorly controlled hypertension can lead to severe complications, including cardiovascular disease, renal disease, cerebral disease and even death. Managing hypertension often requires anti-hypertensive medication, which, when correctly managed, effectively…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Dark Prince

— by Betty Jiang

#painting#art#halloween#spooky#dark academia#dark art#goth#gothic#black phillip#the witch#the vvitch#witch#witchcraft#witchcore#witch community#witch aesthetic#gothcore#goth aesthetic#artist#oil on canvas#oil painting#chaotic academia#anya taylor joy#aesthetic#artblr#art community#art gallery#artists

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

IMPORTANT!!!

I’ve only seen like one person talk about this and it’s super important that this gets out there

Multiple punk symbols and sayings have been added to the FBI’s domestic terrorism guide

Things included are

The symbol for anarchy

ACAB and 1312

The three arrows pointing down in a circle

Eat the rich

Those are a few but it also mentions anything anti-fascist and anti capitalist

So if you live in the US please be careful

#feminism#intersectional feminism#black feminism#feminist#fuck the patriarchy#riot grrrl#inclusive feminism#punk#anti capitalism#anti facist#lgbtq community#equal rights

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Voters Seek Genuine Commitment from Political Leaders"

By Jordan The Producer

In a nation marked by the dynamic political prowess of Joe Biden and Donald Trump, Black voters are still searching for a party that truly values their voice and addresses their concerns. The victories celebrated across the States are undoubtedly significant, but for Black America, the time has come for a deeper understanding of which party is genuinely committed to…

View On WordPress

#Biden2024#Black men#Trump2024#Black Communities#Black History#Black on Black Violence#Black women#Declaration of Independence#Vote

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Who got you smiling like that?"

My friends. I'm so sorry that you can't gain joy from platonic interactions but I'm gonna go back to texting them now.

#my family won't quit thinking I've got a man 😒#its so irritating#aromantic#aro#aroace#asexual#black and aro#black aro#aro and black#black ace#black and asexual#jay's attempts at communicating

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

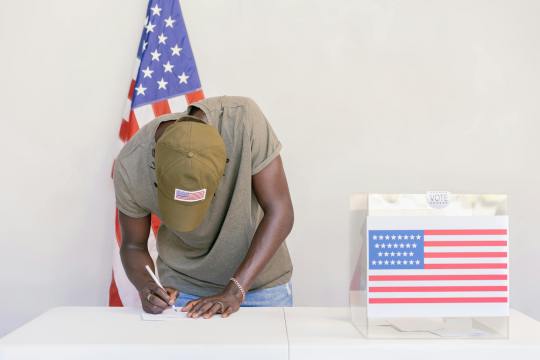

youtube

400 Years - A Case for the Deliberate Destruction of the Black Community

click and enjoy

#400 Years - A Case for the Deliberate Destruction of the Black Community#Black History#Black History matters#Black Communities#urban destruction#Black Lives Matter#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

DCist: Art Installation Calls Out Community Erasure, Past And Present

In what is now known as Metropolitan Park — created in phase one of Amazon’s headquarters in Arlington — a red brick tower stands resolute, reminding passersby that nearly a century ago a community was erased nearby.

The simple structure, which stands 35 feet tall in an area filled with high-rises and office buildings, seems lost in time. Its red brick exterior evokes a long-past, industrial era — one similar, maybe, to the era East Arlington residents lived in.

When visitors step inside the sculpture, they’re greeted by 903 ceramic teardrop-shaped “vessels” — one for every displaced community member.

The space is quiet, intimate and — above all — inspiring. According to Durrett, who spoke in an interview with Street Sense Media, that’s exactly the point.

“I try to leave space for the viewer to experience awe,” Durrett said. “First you see this mundane brick structure that looks like it’s from some bygone period. And then you enter the space and you’re met with something completely unexpected. The viewer then has all of these questions, and then hopefully feels inspired to find the answers and then learn this history that so many people don’t know.”

That history is a tragic one. East Arlington was a victim of displacement long before the 1940s, according to a 2011 presentation by the Arlington Public Library. Many of its residents previously lived in Freedman’s Village, a post-emancipation attempt to house enslaved people, before they were forced out by the government — this time to build the Arlington National Cemetery.

The construction of the Pentagon, at the time the largest office building in the world, initially offered a welcome source of work for men in Queen City, according to Dr. Nancy Perry’s 2014 lecture at the Arlington Historical Society.

East Arlington residents worked on the construction of the Pentagon for months before they were informed that the project would unseat them from their home, Perry said. The Black Heritage Museum of Arlington notes that Queen City was specifically displaced for construction of the transportation corridor that would ferry commuters to the Pentagon.

Without the means to move their belongings, many families were forced to leave behind almost everything they owned, according to the lecture. They fled — first to different temporary housing sites, and then to different parts of the country. Many of them never saw their neighbors again.

It was that side of the tragedy — the human suffering — that the artist said she wanted to evoke. In addition to researching the historic community, Durrett arranged a meeting with one of its last living residents. Her conversation with 92-year-old William Vollin, she said, taught her more about Queen City than archives ever could.

“Being able to identify and speak with someone who has been carrying that history since they were 12 years old further humanized the experiences that those people would have gone through,” Durrett said. “When I was speaking to [Vollin], he didn’t recount losing his home or any material possessions. What he did speak about was the loss of his community. About how he never saw most of those people ever again. He speaks about the destruction of Queen City as though it just happened yesterday.”

But the sculpture is about more than a single community, Durrett said. According to data from the housing search site Apartment List, D.C.’s cost of living is 53% higher than the national average — one of the least affordable cities in the nation.

“Queen City” tells a story of Black displacement at a time when, according to analysis by the Urban Institute, the District’s Black population has been declining for decades. The sculpture, according to Durrett, teaches more than just history.

“The value of learning that history is connecting the dots, it’s seeing how this sort of erasure persists into the present day.”

To create the 903 teardrops that line the interior of “Queen City,” each representing a displaced resident, Durrett commissioned 17 Black ceramicists from across the country.

“One thing that I asked them,” said Durrett, “was to bring forward stories of a Queen City in their own community. Each and every one of them had one.”

Although the artists might have been aware of each other’s work, this was their first opportunity to work together, Durrett said. Each ceramicist had varying abilities and experience, especially with the teardrop-shaped vessels Durrett was requesting.

This led to a “beautiful thing” happening, Durrett said. The ceramicists, rather than working independently on their portion of the commission, collaborated. Artists with more expertise met with less confident ones, creating an atmosphere of compassion and partnership.

In the process of memorializing a community, Durrett said, they had become one themselves.

“Using community, the very thing that was destroyed when East Arlington was razed, to actually create something as grand and long-lasting as ‘Queen City,’ was beautiful,” Durrett said. “It’s not just about the thing, the object — it’s about the process of making it. It’s about showing what we’re all capable of when we work together.”

#Freedmens Village#Queen City#Arlington#Black Cities raised for nothing#pentagon#Black Lives Matter#real estate fuckery#american lies#american hate#white supremacy#imminent domain#East Arlington VA#Black Communities#Black History in america#american history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Histories and Futures Month

View On WordPress

#activism#advocacy#awareness#biodiversity#Black communities#Black entrepreneurs#Black Histories and Futures Month#Black Lives Matter#CARBON FOOTPRINT#celebration#Clean Energy#Climate Action#Climate Adaptation#climate change#climate crisis#Climate Mitigation#collaboration#community#community building#Community Engagement#conservation#contributions#culture#diversity#eco-conscious#economic justice#Ecosystem#education#empowerment#environment

0 notes

Text

trans women are everywhere and are so eager to be seen and heard but only if they feel safe around you. if you hardly ever have trans women interacting with you, especially online, then consider there might be a reason for that and you should address it

#the same thing happens with black people#black people are everywhere! especially online! black gay and black trans people!#but when your community is suspiciously devoid of them then theres something wrong and you need to acknowledge it#even if its not intentional you need to think about how theres minority groups who do not feel safe around you at face value#this is why loud and outright support and solidarity is so important#black people and trans people and etc minority groups will assume you are unsafe unless you explicitly state otherwise#you can't just sit there and say 'well they didnt approach us so its not our fault for not including them!'#like did you TRY to get them to approach you??#cy texts

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Teachers In The Black Communities Having A Difficult Time | The G.A.B.

Full Show On The YouTube (Kamal Johnson Network). Link Below

YT Link

https://youtu.be/KCfrDZJpqdg?si=IuzPFoG_pvbpMckJ via YouTube

Podcast Links

iHeart: https://www.iheart.com/podcast/338-the-gab-101916901/episode/our-teachers-in-the-black-communities-133316106/

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/3Gfobp0RKNSaoch66RyIIv?si=8f8133ade48646db

Apple Podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-g-a-b/id1547660066?i=1000637635297

Podpage: https://www.podpage.com/the-gab/

@youtube @revolttv @bet @foxnews @npr @nbcnews @cbsnews @kusinews @starz @hbomaxes @showtimenetworks @hulu @twitch @msnbc @kpbs @vicemag @abcnews @cnnpolitics @pbs

#black teachers#difficult times#black communities#teachers#difficulties#black kids#sexyy red#jokes#lol#comedy#funny#fyp#for your page#black twitter#white people#black people#black excellence#black show#black podcast#black owned#twitch#youtube channel#comedy videos#funny videos#viral video#black news channel#news#news update#news show

0 notes

Text

For all my beloved mutuals who might need it

35K notes

·

View notes