#fear factory redraw

Text

it was a dare from sabine

#garazeb orrelios#alexsandr kallus#ezra bridger#hera syndulla#kanan jarrus#kalluzeb#kanera#ghost crew#star wars rebels#swr#sw rebels#rebels fanart#fear factory redraw

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Nightmares Fear Factory redraw

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Rainbow Factory

Where your fears and horrors come true

In the Rainbow Factory

Where not a single soul gets through

-------------------------------------------

Oh boy it feels good going back to my roots lol. This is an AU from like 2018 where all my OCs are evil now for some reason, except now it's not 2018 and I can actually give them good reasons for being evil.

You might have noticed how the guy is snarling, but half of his face is smiling, almost like there's two of him or something. This isn't DID, but instead, a mad scientist having a mental breakdown, getting high off werewolf blood and getting possessed. The spirit possessing him says a lot of nonsense about "I am your animal instinct" but is actually just fricking with him. He's actually one of the scientist's victims who died in an experiment involving... Remnant? Determination? Uh... whatever the Pokemon version of soul essence that gives you power ups is, and is getting both a second chance at life, and some sweet, sweet petty revenge.

The scientist himself is trying his absolute hardest to keep himself and everything around him under total control, and only to some success. The idea is that in the main timeline, he's always taking the blame for everything and believes it's his responsibility to make things right. Twist that and you've got a man who needs to control everything for the sake of controlling it.

The big containers full of colour aren't literally for rainbows (just quoting the song at the top there) but is like... pokemon type essence? magic? stuff? And he needs to extract it from the blood for, y'know, mad science reasons.

So... what's this guy's name anyway? Well, in the main timeline, he's called Will Daniels, but had a crisis (because 90% of his character development happens due to a crisis) and changes his name without forsaking his identity. His name before that point was Daniel Willow. In this AU, he's still Daniel Willow (because he never had that crisis), but the spirit possessing him is a "will" of his own, and thus calls himself Will.

I've been telling myself I've wanted to do a redraw of this for five years and I think it paid off

Old version

Speedpaint

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation styles

Animation has 4 major ways of animating, that being traditional animations which are very rare and incredibly difficult to come across today however I feel like the animation style of traditional is one of the most pleasing in my opinion. Traditional animation is achieved by making the animation hand drawn with subtle differences. Some examples of traditionally animation being used in shows, movies and games would be:

Cuphead is a game that fairly recently came out and took around 7 years to develop due too the difficulty of animating however I feel it was definitely worth it

Another example of this style of animation would be

Another style of animation would be Cel animation which works on separating the characters from the background for animation, this allows animators to continue to animate a character without constantly needing to redraw the background with every scene

Another style of animation is stop motion which is made with real world models having the character models change slightly every frame, this type of animation also has incredible results, some of my favourite films are done in stop motion, those being

Fantastic Mr. Fox which is one of my favourite movies

Coraline is also one of my personal favourites however it is a little bit more on the creepier side of films, having horrific scenes in the start of the film, setting the stage for what is to come, the scene of The Beldam Witch creating Coraline doll is incredibly unsettling and targets a lot of peoples fears, such as making needles point towards the camera making it feel as if the needles going to poke your eye out.

youtube

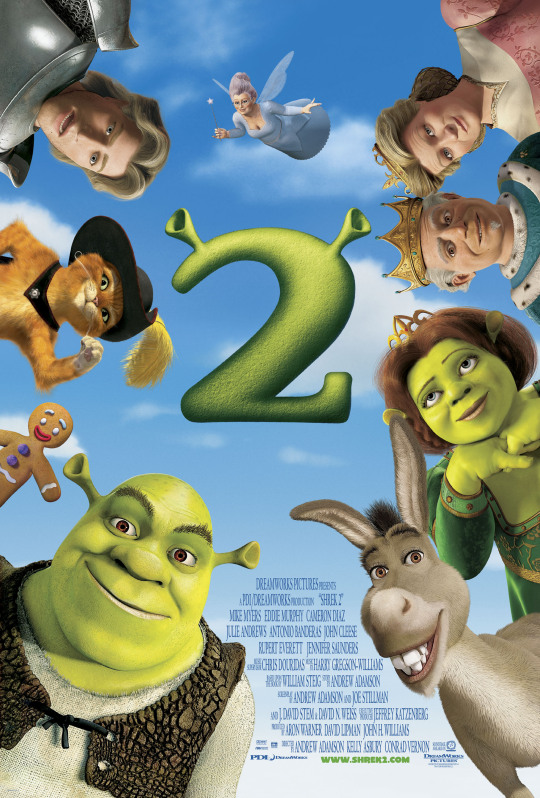

another form of animation is 3D computer generated animation an example of this would be Shrek 2, Shrek 2 is an incredibly fun movie with some really pleasing animation scenes, one of my favourite scenes is when the protagonists are escaping the fairy god mothers magic factory, when the potion fills the room and you see it effecting everything it touches, I really like how the camera follows the characters, another one of the amazing scenes was when the protagonists are doing a siege on the main castle, that scene has great flow and the action matches the musical number really well

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Photo

I got inspired to redraw an old fanart with the boys in tuxedos that I've found in someone's twitt favs which has these two heroes in classy uniforms. You can easily find it the Crystal Story Discord server. I've reposted it there for filling the fanart section.

I also drew this because today I will be going out to eat at Cheesecake Factory this Fourth of July with somebody. (Not my Hubbie, D sadly. It's real wishful thinking...) I'm quite excited since I haven't eat at there for a long time because it’s so expensive. But at the same time, I fear of getting COVID because it's not going away for a while... :(

#crystal story#crystal story ii#crystal story 2#d#d the dragon#kaz#tuxedo#4th of July#date night#sorta

1 note

·

View note

Text

So got bored and made this today

Based on this picture

(....maybe...?)

#art by op#digital art#doodle#drawing#dreamer’s ocs#cute#couple#MHA oc#nightmare fear factory#meme#redraw

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Profile picture vs Tagged Photos

Happy Halloweeen!

twitter+ref pic | Ko-Fi

#Fate grand order#fgo#lancelot#bedivere#gawain#tristan#artists on tumblr#redraw meme#redraw#nightmares fear factory#Happy halloween#halloween

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

decided to make this for fun, it's my redo of the album art for "Digimortal" by Fear Factory.

now, "Digimortal" isn't that good of an album; but i kinda like it.

"Linchpin" is just a good track, what else can i say?

i'm kinda late to the album redraw project thing in my computer class, but i just had to do one, and i thought of this

(illustrated in pixlr)

0 notes

Text

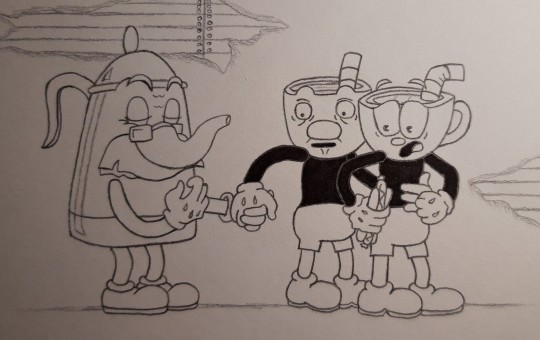

Hi ! I'm new to the Cuphead fandom and I loved Netflix' adaptation.

Episode 6 -"Ghots ain't real" might be my favorite because of Cuphead and Mugman's epic expressions of terror. It reminded me of the hilarious Nightmares Fears Factory reaction photos, and especially this one :

I just had to make a redraw of the cupbros and Elder Kettle exploring the haunted mansion together. Enjoy :

I guess Mugman will need another pants.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌈 In the rainbow factory, where your fears and horrors come true 🔪

Sorta redraw? (Not really but. Yknow) of the rainbow factory!! Been watching some mlp iceberg vids

Heres the OG piece Circa 2013?? Ish??

💖💬🔃 are appreciated

#my art#q#mlp#my little pony#rainbow factory#blood#blood tw#tw blood#scootaloo#rainbow dash#aurora dawn#orion comet#g4#pop culture

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

PRIMED FEELINGS

With the Romantic period one has a multifaceted movement originating in Europe that made its way to the US with the onset of the nineteenth century. Actually, the movement started in the late 1700s and can be seen as one of those social forces that served to heighten people’s awareness of the detrimental effects of a growing political upheaval and the initial industrialization of European life.

Central to its messaging was a focus on emotions and individualism. Part and parcel of its impact was its influence on liberalism, conservatism, nationalism, and radicalism.[1] While the movement’s most observable affect was on that time’s art and literature, the political world was also highly impacted. But to appreciate in which ways it moved politics, one needs to appreciate the directions it maneuvered the creative world of the arts – both the physical arts and in their written forms.

The Enlightenment adopted the classical tradition; the Romantics favored medieval expression. In that, it turns away from concerns of balance, proportion, and idealistic form (the bedrocks of classical art) to expressions of raw emotions and seeing art as the opportunity to be exposed to real experiences. That even included stirring the emotions of horror, terror, fear, and awe. But in the main, it shifted people’s attention to nature and its abundant beauty in its raw states.

With these focuses, Romantic art placed newfound appreciation for what had been previously judged to be common and plebian, that being folk art and national expressions. Now, with this newer view, such traditions were judged as worthy of being honored as noble. This included ascribing honor on national traditions of artistic endeavors that originated in those medieval days before firm national borders and national institutions took hold.[2]

An early expression of this newer sensitivity can be traced to Germany. There the Sturn und Drang (“storm and desire”) movement in that nation’s music and literature – taking place in the late 1760s to early 1780s – one finds works highlighting extreme emotions. They were considered as concerted efforts to rebel against rationalism as dictated by the Enlightenment. Credited with its early expression in words was the works of the philosopher, Johann Georg Hamann, an early proponent of the philosophy of language.

The movement, first in Europe and then in the US, had a recurring tangible target, that being industrialism and urban living as it sprawled with the rise of factories and other manufacturing centers. It was a recurring reaction to the lasting consequences of the Enlightenment, not the least being the French Revolution, even soliciting criticism among many Romantics who initially supported that overthrow of the French monarchy.

As this messaging matured, definite themes emerged. Those included placing high credit on the spokespeople of the movement judged to be heroic as individuals and artists, championing a better society. Especially honored were those seen as leading the way by the expressions of their individual imaginations. A general sense of liberation took hold, that being free from classical dictates as to what was legitimate art and it ushered in a Zeitgeist of this visceral expression.

A German artist, Casper David Friedrich, captured the new thrust with his summary remark, “the artist’s feeling is his law” or the English poet, William Wordsworth’s notion that art is the product of an artist’s powerful feelings that gets refined through the tranquility of his/her recollection. Handed down rules from previous disciplined schools of art were merely considered obstacles to the creation of legitimate art, for after all, these rules were artificial and not the product of the creative process.

The new criteria were authenticity, originality, and the expression of genius. Ultimately, great art was the creation of an expression from nothing. Interpretation or derivation were belittled, originality or novelty were praised. To this one can readily see the role of emotions, not well-thought-out plans or rationales, to calculate what should be done, what should be expressed, and what should be illustrated.

And what better source of such inspiration than nature? While not an essential attribute of Romanticism, nature turned out to be a recurring subject that Romantics exploited in their works. It functioned as a normative standard of goodness, unaffected by societal corruption. People are born as a product of nature and as such are initially innocent as they begin their lives. It is society that corrupts not only humans but defaces nature as well.

Nature, sans society, is pure and worthy of almost spiritual esteem. It took on a status among many Romantics as being worthy of devotion. A painting that is often is depicted as symbolizing this association between the movement and nature is Friedrich’s Wanderer above a Sea of Fog.

Born with the backdrop of war in Europe, this movement had first the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Wars up until 1815 as its setting. In France, the generation that took up the Romantic movement was weaned with the sounds and turmoil associated with this upheaval. According to Alfred de Vigny, the initial artists of this movement were “conceived between battles, attended school to the rolling of drums.”[3]

As for political views, Romantics are judged to have been mostly liberal to progressive but not exclusively. Within their ranks, mostly due to their emotional strains, conservative and even nationalist biases developed. In the extreme, this line of thought or feelings even led to fascism in the twentieth century. Constant attacks on reason led to the questioning – even rejection – of objective truth.

Before finishing these initial introductory remarks on Romanticism, a word on its relation to nationalism seems in order. It, the Romantic inclination, became a source of ongoing messaging or linking of emotional ties to this excessive attachment to one’s nation. And that, as just mentioned above, survived into the twentieth century, and some would argue, the twenty-first century.

This is attributable by historians to the emotionalism of that time. It led to ties not only to a person’s nationality but his/her ethnicity, and race. Of special interest was/is national language and a nation’s folklore. With that, people expressed increased interest in local customs with their accompanying traditions. It also led to national policies that had little concern about the legitimate claims of other nations or peoples.

During that time, Europe, partly because of this emotional bias, experienced various redrawing of national boundaries and even the creation of newer national polities, for example, the unification of Italy and Germany. In addition, nationalism incentivized people to become familiar with the medieval history of their nations when many of the folkloric traditions they could still identify got started and added to their sense of peoplehood.

Renewed popularity in epic poems from that past took on a special interest. And some of that digging into the past even stretched to pre-Roman, Latinization days especially in Germany and Celtic Scotland and Ireland. In many areas of Europe, Napoleonic Wars caused further motivation to heighten national commitments to first fight off this threat and then the actualization of French control.

This is a bit ironic in that the initial reaction to the French Revolution, as alluded to above, stirred Romantics to support its aims and successes. But as Napoleon expanded his control over the various nations of the continent, those nationalists became anti French and anti-Napoleon. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a German philosopher, provides an eloquent expression of this line of thought:

Those who speak the same language are joined to each other by a multitude of invisible bonds by nature herself, long before any human art begins; they understand each other and have power of continuing to make themselves understood more and more clearly; they belong together and are by nature one and an inseparable whole … Only when each people, left to itself, develops and forms itself in accordance with its own peculiar quality, and only when in every people each individual develops himself in accordance with that common quality, as well as in accordance with his own peculiar quality – then, and then only, does the manifestation of divinity appear in its true mirror as it ought to be.[4]

And that sets the stage for this blog to look at the way Romanticism made its presence known in the US.

[1] John Morrow, “Romanticism and Political Thought in the Early 19th Century,” in The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Political Thought: The Cambridge History of Political Thought, eds. Garth Stedman Jones and Gregory Claeys (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 39-76.

[2] Nuria Perpinya, “Ruins, Nostalgia and Ugliness: Five Romantic Perceptions of Middle Ages and a Spoon of Game of Thrones and Avant-Garde Oddity,”, Logos Verlag Berlin (2014), accessed September 9, 2021, Buchbeschreibung: : (logos-verlag.de) .

[3] “Neoclassicism and Romanticism,” Lumen: Boundless Art History (n.d.). Accessed September 9, 2021, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-arthistory/chapter/neoclassicism-and-romanticism/.

[4] Johann Gottlieb Fichte, “Modern History Sourcebook: Johann Gottlieb Fichte: To the German Nation, 1806,” Fordham University (n.d.), accessed September 9, 2021, Internet History Sourcebooks (fordham.edu) .

#Romanticism#Casper David Friedrich#Wanderer above a Sea of Fog#French Revolution#nationalism#Napoleonic Wars#Classical Art#civics education#social studies

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

//petition to redraw our muses in the “Nightmares Fear Factory” haunted house memeeee

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t see why they say the gods are gone

The gods were never gone, they were never dead. The only thing that changed was that we stopped listening.

We still have the weather, thunder and rain. Zeus calls down his storms both in peace to keep our lives safe, and in anger to wreak destruction. We might be better at predicting what is coming, but if the rain stopped coming, what would we do? We depend on the rain, and fear the storm.

More than 90% of the world’s trade comes by the sea. Poseidon watches over the sailors on the oceans, gives to fish to those who hunger, and gives protection to more than half of the life on the world, guarding the oceans and rivers.

Death is still is a part of our lives. When we die, Charon takes us across the rivers of the Underworld, and we face our fates. Hades still watches over the sick, giving strength and life to those still with work left undone, and guards those who find their end, judging them as befitting their deeds.

Love is as strong as before. Love still finds it’s way, no matter how we might try to crush it under a world of apathy and industry. Aphrodite finds those that need love in their lives, and she gives them the courage to take their leaps. Young couples still find Eros, families find their Storge, and marriages find their Pragma.

Homes are still as strong, and as broken as ever. Hera gives lovers the strength to overcome their problems, the endurance to see past the faults in those they love to find the perfection inside. She guards the children of broken homes, and shows the light to those that need it in their lives, to build their own families.

Warfare has changed drastically, coming at longer ranges, but war is as terrible as ever. Ares gives his strength to the weary legs of a soldier on march, and stills the nervous hands gripping at a rifle. He gives life to the wounded, and courage to the broken.

War is bigger now, more complicated. General staffs spend years drawing and redrawing their plans, preparing the perfect ideas to spare the world as much horror as they can. Athena gives wisdom to her field marshals, her officers, that they might know the best path.

Food is needed for every single person in the world. Demeter gives us a bountiful, full harvest so that we might not starve. She holds the hand of those working in the scorching fields, that their work may not be for nothing. She protects the abused animals in the factory farms, and she feuds with her brothers and sisters so that their wrath may not destroy the harvest.

Creation is an essential part of life. Hephaestus watches over not only the smiths, but the writers, the artists and every other smith of creation. He watches men build their battleships, lay the bricks of their buildings that might touch the sky, and the production of that which might not only keep us alive, but to make us prosper.

The gods aren’t gone, and they haven’t forgotten any of us. Even if we stop listening, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t there.

#theoi#hellenic polytheism#hellenismos#zeus#poseidon#hades#aphrodite#hera#ares#athena#demeter#hephaestus#jupiter#neptune#pluto#venus#juno#mars#minerva#ceres#vulcan

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fighting Voter Suppression in Hog Country, North Carolina

A voter waits in line a polling place in Black Mountain, North Carolina | Photo by Brian Blanco/Getty Images

In an election like none before it, the residents of North Carolina’s hog- and poultry-intensive eastern counties are fighting to regain the power of their vote

This story was originally published on Civil Eats.

Elsie Herring spends many days documenting and responding to complaints from her neighbors — about everything from the stench coming off of factory farms to the clearcutting of trees for timber to the emissions from nearby factories. But lately, when Herring, a community organizer for the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (EJN), gets a call, she’s also been making sure the person on the other end of the line has a plan in place to vote.

With almost two million swine within its borders, Herring’s native Duplin County in eastern North Carolina is the top hog-producing county in the United States. And because many residents have pre-existing health conditions, in part from living alongside the waste produced by so many animals, many are choosing to mail their ballots in this year rather than venture to the polls, where COVID-19 presents an additional threat.

But, in a part of the state home to many people of color, Herring worries about reports of minority ballot rejection rates. In North Carolina, the ballots of white voters are being rejected at a rate of .5 percent, while Black voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 1.8 percent rate and Native American voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 4 percent rate (eight times more than white voters’), according to October 21 data from the U.S. Elections Project.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other.

“They’re disproportionate, and right there, that tells me they’re trying to suppress the Black votes,” Herring says. “That has always been their focus, to suppress our vote and not allow us the right.”

And so, she carefully walks her neighbors through the mail-in voting process: “We’re telling them to be careful and aware of what they’re writing and not writing on their ballots. The witness name has to be printed, and you have to have their signature and address. If that’s not there, they kick it out.”

Herring’s fears about the suppression of minority votes are not ill-founded, given recent and long-term efforts in North Carolina. Over the last decade, the state’s General Assembly, which the Republican party has controlled since 2010, has gerrymandered voting district maps along racial lines and passed numerous laws aimed at making it harder for minorities to vote (though many of the measures have not held up in court and are no longer in place).

In the midst of these ongoing efforts, many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities in the eastern part of the state say they’ve repeatedly watched as their elected officials promote the interests of hog and poultry companies over their safety and well-being — as evidenced by the number and density of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) permitted in their communities and the ineffectiveness of the facilities’ waste-disposal systems.

In addition to enabling the industry to concentrate around low-income communities of color, residents say state lawmakers have limited the tools those communities once had at their disposal to protest the resulting pollution.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other: Without people in office to protect their interests, polluting industries such as the state’s industrial hog and poultry operations proliferate and remain largely unchecked, Herring says. And when industries pollute with little consequence, damaging the health and quality of life of the people around them, people are less likely to prioritize getting to the polls, especially given the fact that many are already dealing with myriad other issues, including poverty, food and housing insecurity, and lack of quality education and access to healthcare.

“It’s particularly troubling that when someone who is harmed by all these cumulative impacts seeks to remedy that . . . they find [that] the legislature in recent years has taken very intentional steps to deprive them of long-available remedies,” says Will Hendrick, staff attorney and manager of the Waterkeeper Alliance’s North Carolina Pure Farms, Pure Waters campaign.

“The reaction is, ‘My vote won’t matter — corporations control everything, and that won’t change.’”

Sherri White-Williamson, who worked for years in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office for Environmental Justice before returning two years ago to her hometown in Sampson County, says she has tried to encourage young people in her town to vote. “The reaction is, ‘Why should I? My vote won’t matter — they [corporations] control everything, and that won’t change,’” says White-Williamson, who now works as the NC Conservation Network’s environmental justice policy director. “People who live in communities and get stuff dumped on them feel less empowered to be able to effect any change.”

As a swing state that voted for Barack Obama in 2008, Mitt Romney in 2012, and Donald Trump in 2016, North Carolina will be pivotal in this election. The U.S. Senate race between Republican incumbent Thom Tillis and his Democratic challenger Cal Cunningham could affect which party controls Congress as well. And while there are many conservative parts of the state, the demographics are changing as metropolitan areas continue to grow and more Latinx and young people register to vote.

Despite the factors stacked against them — made worse by the pandemic — Herring says many people in eastern North Carolina are still determined to make their voices heard. This year, groups like the one she’s involved with are working to educate voters and ensure they have transportation to the polls. And while Herring’s biggest concern is that her community’s votes will be under attack, she asks: “What can we do to combat that? I don’t know, other than just showing up at the polls to bring about a change.”

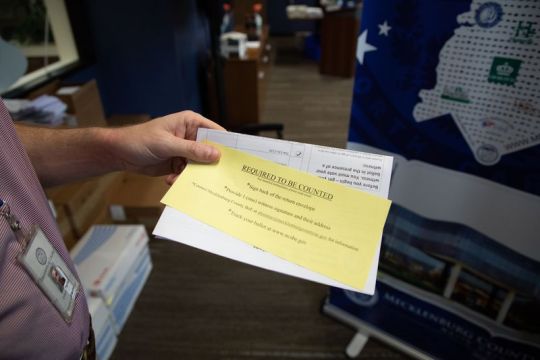

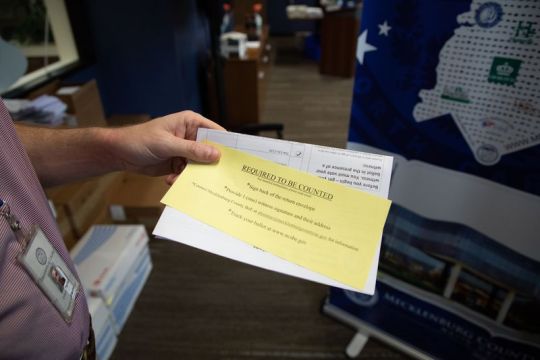

Photo by Logan Cyrus/AFP via Getty Images

An employee of the Mecklenburg County Board of Election in Charlotte, North Carolina holds up instructions that are mailed with absentee ballots for the 2020 election.

Suppressing the vote

In 2011, Republicans gained control of both of North Carolina’s Congressional houses and redrew the legislative district maps in the once-a-decade redistricting process to favor their party. In 2017, a district court and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the maps were illegally racially gerrymandered, meant to dilute the voice of Black voters. Two years after lawmakers submitted new maps, federal judges struck down the voting districts again, this time as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, saying they had been drawn with “surgical precision” — and were among the most manipulated in the nation. Lawmakers were ordered a second time to redraw the maps, which will be redone yet again in 2021, based on the 2020 Census.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in the state have made two other attempts at passing voter suppression laws. HB 589, one of the most dramatic voting rights rollbacks in the U.S., was overturned in federal court after it had been in effect for several years, and the voter ID requirement HB 1092 was blocked by a federal judge.

“There are a lot of different ways people are trying to cut back who is eligible to vote, whose votes count after they are cast, and who is going to feel comfortable voting,” says Kat Roblez, staff attorney with Forward Justice, a nonpartisan organization advancing racial, social, and economic justice in the South. In the Old North State — and nationwide — these tactics commonly include in-person voter intimidation at the polls, periodic purges of voter rolls, the spread of misinformation, voter ID requirements, and felony disenfranchisement laws, she says.

This year, the pandemic and the divisive nature of politics bring additional concerns. While in 2016, about 25 percent of total votes were cast by mail, this year that portion will be almost twice that, according to the Pew Research Center — and voting in a new way comes with its own complications. “It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion,” says Roblez. At the same time, many residents have concerns about the effectiveness of the postal service itself, prompted by budget cuts and policy changes put in place over the summer.

“It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion.”

The increased number of demonstrations by white supremacist and neo-Confederate groups is also worrisome, Roblez says. “What we’re most concerned about in some of the more rural areas is . . . Confederate parades coming to the polls,” she says, recalling how last February, demonstrators hung Confederate flags at a polling site in Alamance County, North Carolina.

Social distancing requirements will also necessitate larger polling places, which can put rural precincts, with less infrastructure available, at a disadvantage. “In an instance where a bigger polling location is needed, they might close two others that are smaller, but that [new] location may not be as accessible,” explains Joselle Torres of Democracy NC.

White-Williamson remembers seeing voter suppression growing up in Sampson County — a particular business owner showing up at the polls to confuse and discourage Black voters, for example — but she hasn’t been aware of polling-place suppression efforts in recent years.

Still, she could see it happening this year. George Floyd was originally from Clinton, the town where she lives, and after his murder at the hands of a white police officer in May, protestors pulled down the Confederate statue in front of the Sampson County courthouse, sparking heated public debates.

“There are a lot of things fresh on people’s minds,” she says. “As a Republican county, I see the potential for there to be efforts at polling places to discourage voting, like what we’re seeing around the country.”

Jeff Currie, a member of the Lumbee Tribe who works as a riverkeeper protecting the Lumber River watershed, believes the poor education system in low-income parts of the state also has a role to play in the area’s disenfranchisement.

“If the education system is not saying ‘vote,’ people don’t understand what voting is — they lack civics training and education and the cultural sense that that’s what you do,” he says.

As Election Day approaches, Democracy NC and Forward Justice are placing volunteer vote protectors at polling places across the state who “are ready and trained to sound the alarm” if they see signs of suppression, adds Torres.

Chuck Liddy/Raleigh News & Observer/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

A pig at Silky Pork Farms in Duplin County, North Carolina

Corporations over constituents

While legislators have tried to limit voting, the hog and chicken industries in eastern North Carolina have grown exponentially in ways that damage their surroundings, residents say. In the 1970s, family farmers in North Carolina raised an average of 60 pigs per farm, and the animals were free to roam around outside. That began to change in the 1980s and ’90s, however, as state lawmakers like teacher and farmer Wendell Murphy sponsored and helped pass bills that shielded large-scale hog farms from local zoning regulations and gave the industry subsidies and tax exemptions.

Now, North Carolina ranks second in the country for the number of hogs it produces, and the state’s average hog farm houses more than 4,000 animals. The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties — the top two hog-producing counties in the country — produce 4 billion gallons of wet waste a year, making up 40 percent of the North Carolina’s total. The waste is stored in open-air pits and periodically sprayed on nearby fields.

The foul-smelling chemicals the facilities release — ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, in particular — have been associated with difficulty breathing, blood pressure spikes, increased stress and anxiety, and decreased quality of life. Additionally, a 2018 study found higher death rates of all studied diseases — including infant mortality, mortality due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia — among communities located near hog CAFOs.

The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties produce 4 billion gallons of waste a year. The waste is stored in open-air pits.

For years, residents have spoken out about their suffering. They’ve told their representatives that the odor from the facilities forces them indoors all the time; they can’t sit on their porches, play in their yards, open their windows, or hang their laundry on the line; they have to buy bottled water rather than drinking from their wells; and “dead boxes” containing pig carcasses line the roads, and buzzards, flies, gnats fill the air.

And yet, says Naeema Muhammad, organizing co-director of the NC EJN, the state legislators and regulatory agencies don’t listen — and repeatedly prioritize large corporations as they make decisions about the permitting and regulation of these facilities. Time after time, she says, “legislators pass bills unmistakably against their constituents, in favor of the industry.”

In 2013, 500 residents of eastern North Carolina filed nuisance suits against the Chinese-owned Smithfield subsidiary Murphy-Brown, LLC, which owns the majority of the hogs in the state, complaining of the health problems and unpleasant ills the company subjected them to. In a victory for the hog-farm neighbors, juries ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the first five of the more than 20 cases to be tried, awarding the 10 plaintiffs in the first lawsuit more than $50 million in damages. (This number was reduced to a total of $3.25 million due to the state’s punitive-damages cap.) The industry is currently appealing the ruling.

As these lawsuits worked their way through the justice system, though, Herring watched in horror as her county’s representative in the state legislature, Jimmy Dixon, sponsored a bill that tied the hands of disadvantaged people looking for protection from factory farm pollution. The bill, passed in 2017, limits the compensation plaintiffs can receive in civil suits like the Smithfield case to a sum related to the diminished value of their property, and prevents them from receiving damages related to health, quality of life, and lost income.

Dixon, who did not respond to a request for comment in this story, said the bill was designed to protect farmers from the “greedy” lawyers who would sue them. “This bill is designed to protect 50,000 hardworking North Carolina farmers who are feeding a hungry world,” Dixon wrote in a 2017 op-ed in The Raleigh News & Observer.

In 2018, Senator and farmer Brent Jackson sponsored a similar bill that practically eliminates the right of residents to sue industrial hog operations by declaring that agricultural operations cannot be considered nuisances if they employ practices generally accepted in the region (like spraying hog waste on fields, for example). “With Senate Bill 711 on the books, we don’t have a leg to stand on,” Herring says. “We have to take what they give us, and [we don’t] have an avenue for recourse.”

Though legislators say they have the interests of farmers and consumers in mind, Muhammad thinks it’s more about campaign contributions. “You have people in power that are owned by the corporations — they’ve taken so much money from them, even if they wanted to do better, the industries would go after them,” she says.

John Althouse/AFP via Getty Images

In 1999, floodwaters from Hurricane Floyd engulfed a Burgaw, North Carolina hog waste lagoon.

Disproportionately polluting poor and minority communities

Those most affected by CAFO pollution are people of color. Duplin and Sampson counties have the highest share of Latinx residents in the state, with 23 and almost 21 percent, respectively. The residents of these two counties are also about 25 and 26 percent Black, as compared with the statewide average of 22 percent.

In 2014, NC EJN, Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH), and Waterkeeper Alliance filed a Title VI Civil Rights complaint with the Office of Civil Rights at the U.S. EPA claiming the North Carolina environmental regulatory agency allowed industrial swine facilities in the state to operate “with grossly inadequate and outdated systems of controlling animal waste and little provision for government oversight” — and that they had an “unjustified disproportionate impact on the basis of race” against Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people.

In 2018, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) settled the complaint, and this year, they put measures in place including a program of air and water monitoring near hog operations and involving impacted community members in permitting decisions. “I believe there’s a group of people [at the DEQ] who are trying to do the right thing,” says Muhammad. “With more collaboration with communities, we’ve seen some change. But you have a body of people who want to hold onto those old ways.”

In the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color.

Another complicating factor is the fact that the state has cut the regulatory agency’s budget year after year. “If you don’t have the budget to hire the staff to do the inspections, that’s a problem,” White-Williamson says.

While the size of pork industry has stabilized since a moratorium on new facilities with the lagoon-and-sprayfield system went into effect in 1997, no such limit was put in place on chicken operations, and as a result, the size of the poultry industry has tripled since then.

According to a report released this summer by the Waterkeeper Alliance and Environmental Working Group, between 2012 and 2019, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys in Duplin, Sampson, and Robeson counties increased by 36 percent to 113 million, compared to only 17 percent in the rest of the state. The racial disparities continue as well: In Robeson County, 42 percent of residents identify as Native American — compared to 1.6 in the state as a whole, according to 2018 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The concentration of chicken CAFOs worries environmental advocates, because rather than being kept in pits, the drier chicken feces is stored in large, uncovered piles and runs off into waterways when it rains. North Carolina chickens produce three times more nitrogen and six times more phosphorous than its hogs, causing environmental damage like toxic algal blooms and fish kills.

Unlike with hogs, the chicken industry does not have to notify the government when it opens a new facility, even if it is in an area prone to floods. As a result, the state environmental regulation agency often does not even know where chicken CAFOs are located, and inspections occur only when a complaint arises.

Lumber Riverkeeper Jeff Currie, who can smell poultry CAFOs from his house, says in the two years that have passed since Hurricane Florence, he’s documented 17 new operations consisting of 320 new barns in the watersheds he watches over.

Currie points out that, in the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline and a controversial wood pellet plant were both slated to be built in low-income communities of color in the area this year. While the pipeline was cancelled in July, the pellet plant is on its way to completion. If you don’t have the money to hire a private attorney and exert influence, Currie says, “you get dumped on.”

The effects of disenfranchisement

The environmental injustices piled onto low-income communities of color stem in part from their lack of political influence; disenfranchisement efforts on the part of politicians and parties who’d like to stay in power only make it worse.

Eastern North Carolina residents say that even without the state’s attempts to make voting difficult for them, the democratic process is frustrating, because when it comes to protecting them from agricultural pollution, there are no candidates who actually represent their interests.

“You get to the point where you’re like, what’s the point?” Currie says. “It’s not party-based — they all took the money. So who do you go to to try to get a bill introduced to end poultry operations in the 100-year floodplain?”

It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage.

White-Williamson believes even if solid state- and federal-level lawmakers were elected in 2020, it would take decades to recover from the damage that has resulted from the regulatory rollbacks, budgetary priorities, and culture of hatred that elected officials have promoted over the last few years. “It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage,” she says. “I feel like this is going to [take] almost a generation to straighten out.”

Muhammad is similarly concerned. “I’ve looked at everybody running from the federal level down to the local level, and I don’t hold out hope it’ll be a process that’ll bring about a lot of change,” she says.

And yet, despite the lack of strong local representation on CAFOs, many eastern North Carolina residents are still motivated by a desire to see change at the top, and they’re mobilizing to help each other get out the vote. Because, despite the roadblocks placed in their way and their lack of expectation for change, they have hope that things can get better — they offer as examples the victory in the Smithfield nuisance cases and the collapse of the oil pipeline project. Though the overall system is structured against them, they’ve seen small successes, and they plan to keep at it.

“If we have to continue to fight for the right to vote, so be it,” Herring says. “Whatever the issue is in our communities that is keeping us from living the best lives we can for our families and children, we have to organize, stay informed, hold meetings, make trips, write letters, make phone calls — do whatever we have to do to keep the issue on the forefront until we bring about change. We can’t give up.”

• Fighting Voter Suppression, Environmental Racism, and Corporate Agriculture in Hog Country [Civil Eats]

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/31HCIWv

https://ift.tt/3jvz0Fh

A voter waits in line a polling place in Black Mountain, North Carolina | Photo by Brian Blanco/Getty Images

In an election like none before it, the residents of North Carolina’s hog- and poultry-intensive eastern counties are fighting to regain the power of their vote

This story was originally published on Civil Eats.

Elsie Herring spends many days documenting and responding to complaints from her neighbors — about everything from the stench coming off of factory farms to the clearcutting of trees for timber to the emissions from nearby factories. But lately, when Herring, a community organizer for the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (EJN), gets a call, she’s also been making sure the person on the other end of the line has a plan in place to vote.

With almost two million swine within its borders, Herring’s native Duplin County in eastern North Carolina is the top hog-producing county in the United States. And because many residents have pre-existing health conditions, in part from living alongside the waste produced by so many animals, many are choosing to mail their ballots in this year rather than venture to the polls, where COVID-19 presents an additional threat.

But, in a part of the state home to many people of color, Herring worries about reports of minority ballot rejection rates. In North Carolina, the ballots of white voters are being rejected at a rate of .5 percent, while Black voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 1.8 percent rate and Native American voters’ ballots are being rejected at a 4 percent rate (eight times more than white voters’), according to October 21 data from the U.S. Elections Project.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other.

“They’re disproportionate, and right there, that tells me they’re trying to suppress the Black votes,” Herring says. “That has always been their focus, to suppress our vote and not allow us the right.”

And so, she carefully walks her neighbors through the mail-in voting process: “We’re telling them to be careful and aware of what they’re writing and not writing on their ballots. The witness name has to be printed, and you have to have their signature and address. If that’s not there, they kick it out.”

Herring’s fears about the suppression of minority votes are not ill-founded, given recent and long-term efforts in North Carolina. Over the last decade, the state’s General Assembly, which the Republican party has controlled since 2010, has gerrymandered voting district maps along racial lines and passed numerous laws aimed at making it harder for minorities to vote (though many of the measures have not held up in court and are no longer in place).

In the midst of these ongoing efforts, many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities in the eastern part of the state say they’ve repeatedly watched as their elected officials promote the interests of hog and poultry companies over their safety and well-being — as evidenced by the number and density of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) permitted in their communities and the ineffectiveness of the facilities’ waste-disposal systems.

In addition to enabling the industry to concentrate around low-income communities of color, residents say state lawmakers have limited the tools those communities once had at their disposal to protest the resulting pollution.

Voter suppression and environmental injustice often perpetuate and compound each other: Without people in office to protect their interests, polluting industries such as the state’s industrial hog and poultry operations proliferate and remain largely unchecked, Herring says. And when industries pollute with little consequence, damaging the health and quality of life of the people around them, people are less likely to prioritize getting to the polls, especially given the fact that many are already dealing with myriad other issues, including poverty, food and housing insecurity, and lack of quality education and access to healthcare.

“It’s particularly troubling that when someone who is harmed by all these cumulative impacts seeks to remedy that . . . they find [that] the legislature in recent years has taken very intentional steps to deprive them of long-available remedies,” says Will Hendrick, staff attorney and manager of the Waterkeeper Alliance’s North Carolina Pure Farms, Pure Waters campaign.

“The reaction is, ‘My vote won’t matter — corporations control everything, and that won’t change.’”

Sherri White-Williamson, who worked for years in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office for Environmental Justice before returning two years ago to her hometown in Sampson County, says she has tried to encourage young people in her town to vote. “The reaction is, ‘Why should I? My vote won’t matter — they [corporations] control everything, and that won’t change,’” says White-Williamson, who now works as the NC Conservation Network’s environmental justice policy director. “People who live in communities and get stuff dumped on them feel less empowered to be able to effect any change.”

As a swing state that voted for Barack Obama in 2008, Mitt Romney in 2012, and Donald Trump in 2016, North Carolina will be pivotal in this election. The U.S. Senate race between Republican incumbent Thom Tillis and his Democratic challenger Cal Cunningham could affect which party controls Congress as well. And while there are many conservative parts of the state, the demographics are changing as metropolitan areas continue to grow and more Latinx and young people register to vote.

Despite the factors stacked against them — made worse by the pandemic — Herring says many people in eastern North Carolina are still determined to make their voices heard. This year, groups like the one she’s involved with are working to educate voters and ensure they have transportation to the polls. And while Herring’s biggest concern is that her community’s votes will be under attack, she asks: “What can we do to combat that? I don’t know, other than just showing up at the polls to bring about a change.”

Photo by Logan Cyrus/AFP via Getty Images

An employee of the Mecklenburg County Board of Election in Charlotte, North Carolina holds up instructions that are mailed with absentee ballots for the 2020 election.

Suppressing the vote

In 2011, Republicans gained control of both of North Carolina’s Congressional houses and redrew the legislative district maps in the once-a-decade redistricting process to favor their party. In 2017, a district court and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the maps were illegally racially gerrymandered, meant to dilute the voice of Black voters. Two years after lawmakers submitted new maps, federal judges struck down the voting districts again, this time as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, saying they had been drawn with “surgical precision” — and were among the most manipulated in the nation. Lawmakers were ordered a second time to redraw the maps, which will be redone yet again in 2021, based on the 2020 Census.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in the state have made two other attempts at passing voter suppression laws. HB 589, one of the most dramatic voting rights rollbacks in the U.S., was overturned in federal court after it had been in effect for several years, and the voter ID requirement HB 1092 was blocked by a federal judge.

“There are a lot of different ways people are trying to cut back who is eligible to vote, whose votes count after they are cast, and who is going to feel comfortable voting,” says Kat Roblez, staff attorney with Forward Justice, a nonpartisan organization advancing racial, social, and economic justice in the South. In the Old North State — and nationwide — these tactics commonly include in-person voter intimidation at the polls, periodic purges of voter rolls, the spread of misinformation, voter ID requirements, and felony disenfranchisement laws, she says.

This year, the pandemic and the divisive nature of politics bring additional concerns. While in 2016, about 25 percent of total votes were cast by mail, this year that portion will be almost twice that, according to the Pew Research Center — and voting in a new way comes with its own complications. “It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion,” says Roblez. At the same time, many residents have concerns about the effectiveness of the postal service itself, prompted by budget cuts and policy changes put in place over the summer.

“It doesn’t have to be active voter misinformation as much as confusion.”

The increased number of demonstrations by white supremacist and neo-Confederate groups is also worrisome, Roblez says. “What we’re most concerned about in some of the more rural areas is . . . Confederate parades coming to the polls,” she says, recalling how last February, demonstrators hung Confederate flags at a polling site in Alamance County, North Carolina.

Social distancing requirements will also necessitate larger polling places, which can put rural precincts, with less infrastructure available, at a disadvantage. “In an instance where a bigger polling location is needed, they might close two others that are smaller, but that [new] location may not be as accessible,” explains Joselle Torres of Democracy NC.

White-Williamson remembers seeing voter suppression growing up in Sampson County — a particular business owner showing up at the polls to confuse and discourage Black voters, for example — but she hasn’t been aware of polling-place suppression efforts in recent years.

Still, she could see it happening this year. George Floyd was originally from Clinton, the town where she lives, and after his murder at the hands of a white police officer in May, protestors pulled down the Confederate statue in front of the Sampson County courthouse, sparking heated public debates.

“There are a lot of things fresh on people’s minds,” she says. “As a Republican county, I see the potential for there to be efforts at polling places to discourage voting, like what we’re seeing around the country.”

Jeff Currie, a member of the Lumbee Tribe who works as a riverkeeper protecting the Lumber River watershed, believes the poor education system in low-income parts of the state also has a role to play in the area’s disenfranchisement.

“If the education system is not saying ‘vote,’ people don’t understand what voting is — they lack civics training and education and the cultural sense that that’s what you do,” he says.

As Election Day approaches, Democracy NC and Forward Justice are placing volunteer vote protectors at polling places across the state who “are ready and trained to sound the alarm” if they see signs of suppression, adds Torres.

Chuck Liddy/Raleigh News & Observer/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

A pig at Silky Pork Farms in Duplin County, North Carolina

Corporations over constituents

While legislators have tried to limit voting, the hog and chicken industries in eastern North Carolina have grown exponentially in ways that damage their surroundings, residents say. In the 1970s, family farmers in North Carolina raised an average of 60 pigs per farm, and the animals were free to roam around outside. That began to change in the 1980s and ’90s, however, as state lawmakers like teacher and farmer Wendell Murphy sponsored and helped pass bills that shielded large-scale hog farms from local zoning regulations and gave the industry subsidies and tax exemptions.

Now, North Carolina ranks second in the country for the number of hogs it produces, and the state’s average hog farm houses more than 4,000 animals. The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties — the top two hog-producing counties in the country — produce 4 billion gallons of wet waste a year, making up 40 percent of the North Carolina’s total. The waste is stored in open-air pits and periodically sprayed on nearby fields.

The foul-smelling chemicals the facilities release — ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, in particular — have been associated with difficulty breathing, blood pressure spikes, increased stress and anxiety, and decreased quality of life. Additionally, a 2018 study found higher death rates of all studied diseases — including infant mortality, mortality due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia — among communities located near hog CAFOs.

The 4.5 million hogs in Duplin and Sampson counties produce 4 billion gallons of waste a year. The waste is stored in open-air pits.

For years, residents have spoken out about their suffering. They’ve told their representatives that the odor from the facilities forces them indoors all the time; they can’t sit on their porches, play in their yards, open their windows, or hang their laundry on the line; they have to buy bottled water rather than drinking from their wells; and “dead boxes” containing pig carcasses line the roads, and buzzards, flies, gnats fill the air.

And yet, says Naeema Muhammad, organizing co-director of the NC EJN, the state legislators and regulatory agencies don’t listen — and repeatedly prioritize large corporations as they make decisions about the permitting and regulation of these facilities. Time after time, she says, “legislators pass bills unmistakably against their constituents, in favor of the industry.”

In 2013, 500 residents of eastern North Carolina filed nuisance suits against the Chinese-owned Smithfield subsidiary Murphy-Brown, LLC, which owns the majority of the hogs in the state, complaining of the health problems and unpleasant ills the company subjected them to. In a victory for the hog-farm neighbors, juries ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the first five of the more than 20 cases to be tried, awarding the 10 plaintiffs in the first lawsuit more than $50 million in damages. (This number was reduced to a total of $3.25 million due to the state’s punitive-damages cap.) The industry is currently appealing the ruling.

As these lawsuits worked their way through the justice system, though, Herring watched in horror as her county’s representative in the state legislature, Jimmy Dixon, sponsored a bill that tied the hands of disadvantaged people looking for protection from factory farm pollution. The bill, passed in 2017, limits the compensation plaintiffs can receive in civil suits like the Smithfield case to a sum related to the diminished value of their property, and prevents them from receiving damages related to health, quality of life, and lost income.

Dixon, who did not respond to a request for comment in this story, said the bill was designed to protect farmers from the “greedy” lawyers who would sue them. “This bill is designed to protect 50,000 hardworking North Carolina farmers who are feeding a hungry world,” Dixon wrote in a 2017 op-ed in The Raleigh News & Observer.

In 2018, Senator and farmer Brent Jackson sponsored a similar bill that practically eliminates the right of residents to sue industrial hog operations by declaring that agricultural operations cannot be considered nuisances if they employ practices generally accepted in the region (like spraying hog waste on fields, for example). “With Senate Bill 711 on the books, we don’t have a leg to stand on,” Herring says. “We have to take what they give us, and [we don’t] have an avenue for recourse.”

Though legislators say they have the interests of farmers and consumers in mind, Muhammad thinks it’s more about campaign contributions. “You have people in power that are owned by the corporations — they’ve taken so much money from them, even if they wanted to do better, the industries would go after them,” she says.

John Althouse/AFP via Getty Images

In 1999, floodwaters from Hurricane Floyd engulfed a Burgaw, North Carolina hog waste lagoon.

Disproportionately polluting poor and minority communities

Those most affected by CAFO pollution are people of color. Duplin and Sampson counties have the highest share of Latinx residents in the state, with 23 and almost 21 percent, respectively. The residents of these two counties are also about 25 and 26 percent Black, as compared with the statewide average of 22 percent.

In 2014, NC EJN, Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH), and Waterkeeper Alliance filed a Title VI Civil Rights complaint with the Office of Civil Rights at the U.S. EPA claiming the North Carolina environmental regulatory agency allowed industrial swine facilities in the state to operate “with grossly inadequate and outdated systems of controlling animal waste and little provision for government oversight” — and that they had an “unjustified disproportionate impact on the basis of race” against Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people.

In 2018, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) settled the complaint, and this year, they put measures in place including a program of air and water monitoring near hog operations and involving impacted community members in permitting decisions. “I believe there’s a group of people [at the DEQ] who are trying to do the right thing,” says Muhammad. “With more collaboration with communities, we’ve seen some change. But you have a body of people who want to hold onto those old ways.”

In the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color.

Another complicating factor is the fact that the state has cut the regulatory agency’s budget year after year. “If you don’t have the budget to hire the staff to do the inspections, that’s a problem,” White-Williamson says.

While the size of pork industry has stabilized since a moratorium on new facilities with the lagoon-and-sprayfield system went into effect in 1997, no such limit was put in place on chicken operations, and as a result, the size of the poultry industry has tripled since then.

According to a report released this summer by the Waterkeeper Alliance and Environmental Working Group, between 2012 and 2019, the estimated number of chickens and turkeys in Duplin, Sampson, and Robeson counties increased by 36 percent to 113 million, compared to only 17 percent in the rest of the state. The racial disparities continue as well: In Robeson County, 42 percent of residents identify as Native American — compared to 1.6 in the state as a whole, according to 2018 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The concentration of chicken CAFOs worries environmental advocates, because rather than being kept in pits, the drier chicken feces is stored in large, uncovered piles and runs off into waterways when it rains. North Carolina chickens produce three times more nitrogen and six times more phosphorous than its hogs, causing environmental damage like toxic algal blooms and fish kills.

Unlike with hogs, the chicken industry does not have to notify the government when it opens a new facility, even if it is in an area prone to floods. As a result, the state environmental regulation agency often does not even know where chicken CAFOs are located, and inspections occur only when a complaint arises.

Lumber Riverkeeper Jeff Currie, who can smell poultry CAFOs from his house, says in the two years that have passed since Hurricane Florence, he’s documented 17 new operations consisting of 320 new barns in the watersheds he watches over.

Currie points out that, in the name of “creating jobs,” governing bodies allow all sorts of polluting industries to cluster in communities of color. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline and a controversial wood pellet plant were both slated to be built in low-income communities of color in the area this year. While the pipeline was cancelled in July, the pellet plant is on its way to completion. If you don’t have the money to hire a private attorney and exert influence, Currie says, “you get dumped on.”

The effects of disenfranchisement

The environmental injustices piled onto low-income communities of color stem in part from their lack of political influence; disenfranchisement efforts on the part of politicians and parties who’d like to stay in power only make it worse.

Eastern North Carolina residents say that even without the state’s attempts to make voting difficult for them, the democratic process is frustrating, because when it comes to protecting them from agricultural pollution, there are no candidates who actually represent their interests.

“You get to the point where you’re like, what’s the point?” Currie says. “It’s not party-based — they all took the money. So who do you go to to try to get a bill introduced to end poultry operations in the 100-year floodplain?”

It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage.

White-Williamson believes even if solid state- and federal-level lawmakers were elected in 2020, it would take decades to recover from the damage that has resulted from the regulatory rollbacks, budgetary priorities, and culture of hatred that elected officials have promoted over the last few years. “It’s going to be hard to reverse a lot of the environmental damage that has been done, as well as the cultural and racial damage,” she says. “I feel like this is going to [take] almost a generation to straighten out.”

Muhammad is similarly concerned. “I’ve looked at everybody running from the federal level down to the local level, and I don’t hold out hope it’ll be a process that’ll bring about a lot of change,” she says.

And yet, despite the lack of strong local representation on CAFOs, many eastern North Carolina residents are still motivated by a desire to see change at the top, and they’re mobilizing to help each other get out the vote. Because, despite the roadblocks placed in their way and their lack of expectation for change, they have hope that things can get better — they offer as examples the victory in the Smithfield nuisance cases and the collapse of the oil pipeline project. Though the overall system is structured against them, they’ve seen small successes, and they plan to keep at it.

“If we have to continue to fight for the right to vote, so be it,” Herring says. “Whatever the issue is in our communities that is keeping us from living the best lives we can for our families and children, we have to organize, stay informed, hold meetings, make trips, write letters, make phone calls — do whatever we have to do to keep the issue on the forefront until we bring about change. We can’t give up.”

• Fighting Voter Suppression, Environmental Racism, and Corporate Agriculture in Hog Country [Civil Eats]

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/31HCIWv

via Blogger https://ift.tt/3orBhVR

0 notes

Photo

So, I totally forgot about this piece. Whoops.

I did a collab with my homie @kcxzy way back in Halloween times this year.

I convinced Kc to help our characters as the two people in this nightmare fear factory reaction. Clove was done by me, and Yumo by them.

Old meme I know, even at the time, but I finally felt I was good enough to do a redraw of a nff reaction picture because I absolutely loved this redraw meme when it was super popular on Tumblr a few years ago, but my art was garbage. I know I’ve improved, I feel like I even improved since doing this back at the end of sept.

(still makes me giggle)

#clove#clove mohs#crystals#deer#furry#wolf#anthro#fursona#oc#my art#colab#halloween#spooky#haunted#house#nff#nightmare fear factory reaction#reaction#kcxzy

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I hope to do more, but in case that doesn't happen, consider this my Halloween pic. Also what is shading?

Voltron redraw from the Nightmares Fear Factory.

5 notes

·

View notes