#i am aware that hitler was born in Austria

Text

I Was reminded of this part in one of his autobiographies where Asimov talks about persecution and stuff like that, and I still think he does such a good job with it that I’ve decided to share a transcription I tracked down (and I think they mean to say transcription, cause it was always in english, but I’ll leave the credits in unaltered)

I just think it’s worth a read

I, Asimov: A Memoir, 1994; pp.20-21

(Transcription and all errors therein, by Lawrence of Cyberia)

My father was proud to say there had never been a pogrom in the small town where he was born, where Jews and Gentiles lived together without problems. In fact, he himself had a friend from a Gentile family, whom he used to help out with his homework. After the [1917] Revolution, the childhood friend became a Party official, and he in turn helped my father get the necessary papers to emigrate to the United States. This detail is important, because I’ve often read in the writings of wild romantics that my family fled Russia to escape persecution. According to them, we couldn’t have left the country except by jumping from ice floe to ice floe across the Dnieper River, with a pack of bloodthirsty dogs and the entire Red Army snapping at our heels.

Obviously, there was none of that. We weren’t persecuted, and we left entirely legally with no more red tape than one would expect from bureaucracy in general and from ours in particular. Sorry if that’s a disappointment.

Nor do I have horror stories to tell about my life in the United States. I have literally never suffered for being Jewish; by which I mean no one has ever hit me or [physically] abused me in any way. On the other hand, I have been provoked many times – openly by young louts, more subtly by educated people. But I accepted it; to me, these things were an inevitable part of the universe, that I could not change.

I also knew that large swathes of American society would remain closed to me because I was Jewish, but that was how it was in all Christian societies, going back two thousand years; so again, this was part of life. What was difficult to bear, however, was the feeling of permanent insecurity, and sometimes even terror, in the face of what was happening in the world. I am speaking here about the 1930s, and the rise of Hitler with his increasingly ferocious and increasingly deadly antisemitic madness.

No American Jew could fail to be aware that first in Germany, then Austria, Jews were constantly humiliated, abused, imprisoned, tortured and murdered simply because they were Jews. We could not ignore the fact that Nazi-like parties were emerging in other parts of Europe, using antisemitism as their rallying cry. Even France and Great Britain were affected; both of them saw the emergence of a fascist-type party, and both had a long history of antisemitism.

We weren’t even safe in the United States, a country where there was always an undercurrent of antisemitism and which was not immune to the occasional whiff of violence from the roughest street gangs. There was also a certain attraction to Nazism. I’m not talking here about the German-American Bund, the declared agent of the Nazis, but we heard individuals like Father Charles Coughlin, or Charles Lindbergh, expressing openly antisemitic views. Not to mention the indigenous fascist movements that rallied around the banner of antisemitism.

How did American Jews withstand this pressure? How did they not give way under its weight? I suspect that most simply adopted an attitude of “denial”, refusing to face up to things. They tried not to think about it and did their best to go on living as before. And to a large extent, that’s what I did too. There was no choice. (The Jews of Germany behaved the same way until the storm broke and it was too late.) Furthermore, I had too much faith in my country, the United States of America, to believe that it could one day follow the German example.

It is a fact that Hitler’s excesses, not only the racism but also the belligerent nationalism and the increasingly obvious rampant paranoia, aroused disgust and anger among a considerable number of Americans. Even if the government of the United States was on the whole non-committal about the tragic fate of Jews in Europe, its people were increasingly opposed to Hitler. That at least is how it seemed to me, and I took some comfort in that.

I tried also not to let myself become unpleasantly obsessed with the idea that antisemitism was the major problem in the world. Around me, many Jews separated the people of the world into two categories: Jews and others, and that was it. There were many who did not care about any problem except antisemitism, wherever and whenever it arose.

For me, it was evident that prejudice was instead a universal phenomenon, and that all minorities, all groups that were not at the top of the social ladder, were potential victims of it. In the Europe of the 30s, it was the Jews who suffered most dramatically, but in the United States, they were not the ones who were worst treated. Anyone who didn’t deliberately shut his eyes knew very well that over here it was the African-Americans. For two centuries they had been enslaved. Then we had theoretically put an end to that, but just about everywhere they had attained no more than a “semi-slave” status: they had been denied their most basic rights, treated with contempt and deliberately excluded from the so-called “American dream”.

Although I was Jewish and poor as well, I benefited from the American education system at its best and attended one of its finest universities; I wondered, how many African-Americans would have had the same opportunity at that time? Denouncing antisemitism without denouncing human cruelty in general troubled me constantly. The general blindness was such that I heard Jews condemn unreservedly the phenomenon of antisemitism, and then without skipping a beat move on to the African-American question, and talk about it as if they were little Hitlers. If I pointed this out to them and objected strenuously, they turned on me. They were completely unable to see what they were doing.

I once heard a lady speak passionately about the Gentiles who had done nothing to save the Jews of Europe. “You just can’t trust them”, she claimed.

I let it pass for a while, and then I suddenly asked: “And what are you doing to help the Blacks achieve their civil rights?”

“Listen”, she retorted. “I have enough problems of my own”.

And I said: “That’s exactly what the Gentiles of Europe said”. I saw a complete lack of comprehension in her face. She couldn’t see what I was getting at. What can we do about it? The whole world seems to be permanently waving a banner that reads: “Freedom! … but not for others”.

I publicly expressed my view on this only once, and in delicate circumstances. It was in May 1977. I was invited to a round-table discussion whose participants included Elie Wiesel, who survived the Holocaust and hasn’t spoken about anything else since. That day, he irritated me by claiming that you couldn’t trust academics, or technicians, because they had helped make possible the Holocaust. What a sweeping generalization that is! And precisely the kind of remark that antisemites might make: “I don’t trust Jews, because once, Jews crucified my Saviour”.

I let the others argue for a moment while I brooded over my resentment; then, unable to contain myself any longer, I spoke up: “Mr. Wiesel, you’re wrong; the fact that a group of people has suffered appalling persecution does not mean it is inherently good and innocent. All that the persecution proves is that this group was in a position of weakness. If the Jews were in a position of strength, who knows if they wouldn’t become persecutors?”

To which Wiesel replied, very angrily: “Give me one example of the Jews persecuting anyone!”

Naturally, I was expecting this. “At the time of the Maccabees, in the second century BCE, John Hyrcanus of Judea conquered Edom and gave the Edomites the choice of conversion to Judaism, or death. Not being idiots, the Edomites converted, but afterwards they were still treated as inferiors because even though they had become Jews, they were still originally Edomites”.

Wiesel, even more upset, said: “There is no other example.”

“There is no other period in history where Jews have exercised power”, I replied. “The only time they had it, they behaved just like the others.”

That put an end to the discussion. I would add however that the audience was entirely on the side of Elie Wiesel.

I could have gone further. Alluded to the fate of the Canaanites at the hands of the Israelites in the time of David and Solomon, for example. And if I’d been able to predict the future, I could have mentioned what is happening in Israel today. The Jews of America would have a clearer understanding of the situation if they could imagine the roles reversed: with Palestinians governing the country and Jews throwing stones at them with the energy of despair.

I had the same kind of argument with Avram Davidson, author of brilliant science fiction, who is of course Jewish, and was – at least at one time – conspicuously Orthodox. I wrote an essay on the Book of Ruth, which I saw as an appeal for tolerance in opposition to the cruel edicts of Ezra the scribe, who encouraged Jews to “renounce” their foreign wives. Ruth was a Moabite, a people the Jews clearly detested; yet she is portrayed in the Old Testament as a female role model, and is even listed as an ancestor of David. Avram Davidson took offense at my insinuation (that Jews could be intolerant), and I was treated to a very sarcastic letter in which he too asked me if the Jews had ever been persecutors. I replied in part: “Avram, you and I live in a country that is 95% non-Jewish, and that doesn’t pose any particular problem for us. What would happen to us on the other hand if we were Gentiles living in a country that was 95% Jewish Orthodox?”

I never received a reply.

Even as I write, Jews are immigrating from the former Soviet Union into Israel. They are fleeing their country because they fear religious persecution. But the moment they set foot on Israeli soil, they become Zionist extremists who are merciless toward the Palestinians. They change from persecuted to persecutors in the blink of an eye.

That said, the Jews are not alone in this. If I’m sensitive to this particular problem, it’s because I’m Jewish myself. In fact, this phenomenon is universal. In Roman times, when the first Christians were persecuted, they pleaded for tolerance. But when Christianity prevailed, did tolerance reign? Not on your life. Instead, persecution was soon going on in the opposite direction. Or take the case of the Bulgarians, who demanded freedom from their dictatorial regime, but once they had it used it to aggress against their Turkish minority. Or the people of Azerbaijan, who demanded of the Soviet Union the freedom denied it by the central government, only to immediately attack the Armenian minority.

The Bible teaches that the victims of persecution must in no circumstances become persecutors in their turn: “Do not mistreat an alien or oppress him, for you were aliens in Egypt.”(Exodus 22:21). But who follows this teaching? Personally, whenever I try to spread the word, I get hostile looks and make myself unpopular….

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

My grandfather and World War 2 - a slightly longer conversation with ChatGPT

Following a short conversation with ChatGPT last month, I have managed to find a bit more time to think about questions, interact, respond and ultimately to get a bit more from the internet's new posterchild.

I am trying to trace the movements of my grandfather during world war 2. If I provide you with statements as if written from his point of view, can you help give historical context so I can try and see situations through his eyes?

Of course, I'd be glad to assist you in understanding the historical context and providing insights into your grandfather's experiences during World War II. Please feel free to share the statements from his perspective, and I'll do my best to offer relevant historical information and context to help you gain a deeper understanding of his journey and the events he might have encountered during that time.

I was born in Stara Oselica in Slovenia in 1923 on a farm with brothers and sisters. Was this Slovenia or Yugoslavia at this time?

In 1923, the region of Stara Oselica was part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which was later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. So, at the time of your birth in 1923, it was known as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

This country was created after World War I, when several South Slavic regions, including Slovenia, Croatia, and Serbia, came together to form a new unified state. The name was changed to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, and it remained that way until World War II when the country was invaded and disintegrated.

Your birthplace, Stara Oselica, would have been part of this larger kingdom during your early years. If you have any more statements or questions, feel free to share them, and I'll continue to provide historical context and help you understand the events during your grandfather's time.

Before Germany invaded, would knowledge of the Nazis and the invasion of Poland etc be common knowledge in Yugoslavia? Would I have been expecting them to invade?

Before Germany invaded Yugoslavia, knowledge of the Nazis and their actions, including the invasion of Poland, would have been relatively limited among the general population. In the 1930s, the rise of Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler was mostly seen as a distant and foreign phenomenon, and news about the specific events in Germany, such as the annexation of Austria (Anschluss) in 1938 and the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, might have reached Yugoslavia, but not in great detail.

During this time, communication and information dissemination were not as advanced as they are today. Newspapers, radio broadcasts, and word-of-mouth were the primary means of information sharing. As a result, the knowledge of international events was somewhat restricted, and the common people in rural areas, like Stara Oselica in Slovenia, might have been less aware of the geopolitical developments in Europe.

While there may have been some awareness of tension and instability in Europe, the notion of an imminent German invasion of Yugoslavia would likely not have been a widespread expectation among the general population until the actual invasion began in April 1941. The rapid and unexpected nature of the invasion caught many people by surprise, leading to a swift and chaotic occupation of the country.

In 1941 Germany invaded. Is it likely they did this through Austria and into Slovenia?

Yes, that's correct. In 1941, Germany invaded Yugoslavia during World War II. The invasion took place through Austria and into Slovenia. On April 6, 1941, German forces, along with their Italian and Hungarian allies, launched an offensive against Yugoslavia from multiple directions, including Austria and northern Slovenia.

The German invasion of Yugoslavia was swift and overwhelming, leading to the rapid collapse of the Yugoslav defenses. Within a short period, most of the country was under Axis occupation. This invasion marked the beginning of a tumultuous and difficult time for the people living in the region, including those in Slovenia, who had to endure the hardships of occupation and resistance throughout the war.

At age 17 when the Germans invaded, am I too young to sign up to the army either Yugoslav or the German army?

During World War II, the minimum age for military service in Yugoslavia and Germany varied based on specific regulations and circumstances. However, in general, at the age of 17, you would likely have been considered too young to voluntarily join the regular army, both in Yugoslavia and Germany.

In Yugoslavia, the legal conscription age during peacetime was typically 21, and it's unlikely that they would have accepted recruits below that age even in the face of an invasion. However, during the chaos of war and occupation, there were instances where younger individuals might have been unofficially enlisted or involved in partisan and resistance activities.

In Nazi Germany, the legal conscription age was 18, and those younger than that were generally not eligible for regular military service. However, the Hitler Youth, a paramilitary organization, actively recruited boys aged 10 to 18 for ideological and militaristic training. While it wasn't a regular army, the Hitler Youth played a role in shaping young minds and promoting Nazi ideology.

It's important to note that during times of war and occupation, circumstances were often unpredictable, and some individuals, even underage, might have attempted to join military forces due to various factors like the lack of alternatives, pressure from authorities, or ideological beliefs. Nonetheless, the standard legal age for enlistment in both countries was typically higher than 17.

My most likely course of action at first then is to survive. I continue to work on the farm and sell produce locally where we can. Could I have travelled easily into Italy across the border?

During the initial stages of the German invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia, survival and maintaining a sense of normalcy would have been primary concerns for many civilians, including you on your family's farm in Stara Oselica.

As for traveling into Italy across the border, it would have been challenging and risky during the early years of the war. After the invasion of Yugoslavia, the country was quickly partitioned among various Axis powers. Italy occupied parts of Slovenia, including areas close to the border, and established a border barrier known as the "Alpine Wall" to prevent unauthorized crossings.

Border controls and restrictions would have been tightened, and attempting to cross into Italy without proper authorization or permits would have been perilous. Additionally, the German and Italian occupation authorities were vigilant in monitoring movement, and attempting to escape or cross borders could result in severe consequences, including arrest, deportation, or even execution.

During the occupation, the situation for civilians worsened, and many found themselves facing food shortages, forced labor, and other hardships. It's likely that your focus would have been on surviving on the farm and coping with the challenges imposed by the occupiers.

As the war progressed and the situation evolved, some individuals did manage to escape and join resistance movements or seek refuge in neighboring countries, but such actions were risky and required careful planning and support from sympathetic individuals or groups.

The Partisan movement had reached out my family and some had signed up. When did the Partisans first become active?

The Partisan movement in Yugoslavia was a significant resistance force during World War II. It was led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito. The Partisans were one of the key resistance groups fighting against the Axis powers and their collaborators during the war.

The Partisan movement began to take shape shortly after the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941. Initially, the resistance was fragmented and disorganized, but over time, it coalesced into a more unified and effective force under the leadership of Tito. By the summer of 1941, the Partisans had started to gain momentum and become more active in their efforts to resist the occupation.

During the early stages, the Partisans engaged in guerrilla warfare, ambushing Axis troops and conducting hit-and-run attacks. They also focused on recruiting and organizing resistance fighters from different parts of Yugoslavia, including rural areas like Stara Oselica.

The Partisan movement grew in strength and popularity, especially among the rural population, as they offered an alternative to both the occupying Axis forces and the collaborationist forces of the Independent State of Croatia (a Nazi puppet state established in parts of Yugoslavia).

It's important to note that while the Partisans were one of the major resistance forces, there were other resistance groups in Yugoslavia, such as the Chetniks, who had a different approach and sometimes clashed with the Partisans. The resistance movements in Yugoslavia were diverse, and the dynamics between them were complex.

If your family had members who signed up with the Partisans, they would have been part of this growing resistance movement, fighting for the liberation of Yugoslavia from Axis control and the establishment of a new socialist Yugoslavia after the war.

At age 17, possibly 18, I am a lookout for the partisans. Years later I will tell my family a story of how I would sit on a high bridge and watch for German tanks. I remember the day clearly when I saw the tanks advancing and had to run and tell others. Is there a bridge near Stara Oselica?

As an AI language model, I don't have access to specific maps or locations, and my knowledge is limited to information available up to September 2021. However, I can provide some general context regarding bridges in the region.

Stara Oselica is a small village in Slovenia, and Slovenia, as a whole, is known for its diverse landscape, with numerous rivers and streams. Given this geographical characteristic, it is likely that there would have been bridges in the area, providing essential crossings over rivers and ravines.

As a lookout for the Partisans, being stationed on a high bridge would have offered a strategic advantage, as it allows for a broader view of the surroundings and better surveillance of potential enemy movements. If there was a bridge near Stara Oselica, it could have been an ideal location for a lookout post during the resistance efforts against the Axis forces.

If you are looking for a specific bridge in the vicinity of Stara Oselica, I recommend consulting local historical records, maps, or reaching out to historical societies or experts in Slovenian history and geography. They might be able to provide more detailed information on the location of bridges and their relevance during World War II in the region.

Remember that historical records, especially from the wartime period, can be fragmented and sometimes difficult to access, but local historians and enthusiasts may have valuable insights that could help you piece together your grandfather's experiences.

Our involvement with the partisan movememnt means that we are at higher risk of being caught and severely punished. Would the punishment have been internment camps in Italy, Yugoslavia, Austria or Germany? Is there one of these camps which would have been more commonly used?

During World War II, individuals involved with the Partisan movement in Yugoslavia were indeed at higher risk of being caught and facing severe punishment if captured by the Axis forces or their collaborators. The specific punishment and treatment of captured Partisans varied depending on the circumstances and the policies of the occupying forces.

Internment camps were one of the forms of punishment used by the Axis powers for captured resistance fighters, including Partisans. These camps were established in various locations across the occupied territories, including Italy, Yugoslavia, Austria, and Germany.

In Yugoslavia, the Axis powers and the collaborationist authorities operated several internment camps for captured Partisans and other resistance members. These camps were known for their harsh conditions, and prisoners often faced forced labor, malnutrition, and abuse.

In Italy, the occupiers maintained internment camps for captured Partisans and Allied prisoners of war. Some of the well-known camps in Italy included Camp PG 29 in Servigliano and Camp PG 57 in Grupignano.

In Austria and Germany, captured Partisans and resistance members were sometimes transported to concentration camps, such as Mauthausen-Gusen in Austria or camps like Dachau and Buchenwald in Germany. These concentration camps were notorious for their brutal treatment of prisoners and high mortality rates.

It's important to note that the treatment of Partisan prisoners was often brutal and inhumane, and many faced the risk of execution, torture, or being sent to forced labor camps.

As the war progressed and the Partisan movement grew stronger, the Axis forces intensified their efforts to suppress the resistance, making the risk of capture and punishment even higher. Many Partisans chose to live in hiding, engage in guerrilla warfare, or seek refuge in remote areas to avoid detection and capture.

Again years later, I will tell my family of my escape from an internment camp. I even have a photograph of me from inside a camp. Were escapes frequent?

Escapes from internment camps, especially during World War II, were relatively rare and challenging endeavors. Internment camps were designed to be heavily guarded and escape-proof, making it difficult for prisoners to break out. However, despite the formidable obstacles, there were instances of courageous and daring escape attempts by prisoners, including Partisans and other resistance members.

The frequency of successful escapes varied from camp to camp and depended on several factors, such as the camp's security measures, the determination and resourcefulness of the prisoners, and sometimes, favorable external circumstances that created opportunities for escape.

In many cases, escape attempts were met with severe consequences if caught, including execution or harsher conditions for those remaining in the camp. As a result, prisoners often carefully planned escape attempts, sometimes with the help of fellow inmates or sympathetic individuals outside the camp.

The determination to escape was often driven by a desire to rejoin the resistance, continue the fight against the occupiers, or simply regain freedom. Escapes could be carried out individually or as part of larger organized efforts, depending on the circumstances.

While successful escapes were not common, they did occur, and each escapee's story represents an extraordinary tale of courage and resilience. These stories have become part of the collective memory of resistance movements during World War II, highlighting the strength of the human spirit and the lengths people were willing to go to resist oppression.

If your grandfather had a photograph from inside an internment camp and shared stories of his escape, it would be a testament to his bravery and determination in the face of adversity.

Other than the photo from an unknown camp, there are no records of my location or activity between 1941 and 1945, when I am picked up in Naples by Allied forces and am asked to join the British RAF as an Aircrafthand. If I have been in Italy most or all of this time, how will I have survived?

If there are no specific records of your location or activities between 1941 and 1945, and you were indeed in Italy during this time, your survival would have been a testament to your ability to adapt, evade detection, and navigate through the challenging circumstances of war.

Here are some possible ways you might have survived in Italy during World War II:

Underground Activities: As a member of the Partisan movement, you might have operated covertly, engaging in clandestine activities, and avoiding capture by the Axis forces and their collaborators. The Partisans were known for their ability to hide in remote areas, organize in secret cells, and carry out hit-and-run attacks.

Living in Hiding: You could have gone into hiding in rural areas or small villages, seeking refuge with sympathetic locals who were willing to help and protect resistance members.

Disguise and False Identity: To avoid detection, you might have adopted false identities or changed your appearance to blend in with the civilian population.

Avoiding Main Roads and Checkpoints: You might have traveled on backroads and avoided main highways and checkpoints where Axis forces were more likely to be present.

Connections with the Local Population: Having support and assistance from locals who were sympathetic to the resistance cause would have been crucial for survival. Local networks of support often provided food, shelter, and information to resistance members.

Escape from Internment Camp: If your escape from the internment camp was successful, you might have gone into hiding or sought refuge with the Partisans or other resistance groups.

Moving Between Safe Houses: Resistance members often moved between safe houses to avoid detection and ensure their safety.

It's important to remember that surviving during wartime required resourcefulness, courage, and the ability to adapt to ever-changing circumstances. Many individuals who were involved in resistance activities during World War II faced significant risks but managed to survive through their determination and the support of others in similar situations.

As a survivor who eventually gets picked up by the Allied forces and asked to join the British RAF, your experiences would likely have shaped you in ways that made you a valuable asset for the Allies in their efforts to defeat the Axis powers.

I read somewhere that there were over 40,000 camps at the peak of World War 2. Are there any official figures on this, and is it known how many were in Italy?

The number of camps during World War II was indeed substantial, but it's challenging to pinpoint an exact figure due to the sheer scale of the conflict and the diverse types of camps that existed. Many of these camps served different purposes, ranging from concentration camps, prisoner of war (POW) camps, internment camps, labor camps, and more.

While the number of camps might have reached tens of thousands globally, it's essential to differentiate between major camps, satellite camps, and smaller temporary facilities. Some sources estimate that there were over 40,000 camps or detention sites in various parts of Europe during the war, but this number includes both major camps and smaller, temporary facilities.

As for Italy, the country had its share of camps, including POW camps, concentration camps, and internment camps. The Italian government established internment camps for individuals considered to be a threat to the regime, and the Axis occupiers also operated camps for prisoners of war and other detainees.

One notable concentration camp in Italy was the Risiera di San Sabba, located in Trieste. This camp was used by the Nazis and the Italian Fascist forces to detain and execute prisoners, particularly during the latter part of the war.

The number of camps and their locations in Italy can be challenging to determine precisely, as historical records might be fragmented or incomplete. Additionally, some of the smaller camps and temporary facilities might not have been well-documented.

If you're interested in exploring more about specific camps in Italy or seeking official figures, I recommend consulting historical archives, research institutions, or experts in Italian history and World War II. They might have more detailed information and can guide you in your research.

There are a couple of things of note in the above conversation which I will investigate further once I have completed the RAF/Military Service investigations. I have felt for a while that my grandfather may have given a false name when in Italy and during any captivity, so it is interesting that ChatGPT presents the same theory.

I have slightly jumped ahead by thinking about the conflict & Prisoner of War period, but these questions had been buzzing around my brain for a while, and following my disappointment after contacting official sources, I personally needed some new theories and angles to investigate further.

ChatGPT is becoming an invaluable resource. Even if you take some of this information at face value, the ability to ask questions of something and get some reflections, albeit AI generated, is massively helpful for me as I struggle for time whilst juggling this research with a family and full time demanding job.

But it is this last sentence from ChatGPT which rings very true. It is both a reminder of what I have taken on and an unlikely source of motivation;

Remember that genealogical research can be both rewarding and challenging, and the journey to uncovering your family's history often requires time, patience, and persistence.

#familyhistory#family tree#yugoslavia#world war 2#prisoner of war#italy#chatgpt#ai#artificial intelligence

1 note

·

View note

Text

My top 5 European Countries based on their history and relevance

Disclaimer*

I am aware that no country's history is without violence, atrocities, or bloodshed. This is by no means glorifying or justifying the dark history that a country has. With that said, lets begin with the list.

5. Austria

- Austria is one of the youngest country in this list so it's history is not that long but still interesting and important. Austria started out as a state in the Holy Roman Empire and it was governed personally by the Holy Roman Emperor. And so, when HRE dissolved, The current Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II, only has the kingdom of Austria to rule. Even if the lands he rule diminished, that doenst mean that his influence and powers have as well. Austria still remained as an influential figure to Europe and one that plays a huge part on the countless vital events.

4. Spain

- The nation who first discovered America. The nation who colonized many countries, including the Philippines. And the nation that only existed because of the marriage of two monarchs. Their history is pretty complex because at first, it was considered as an Muslim Kingdom known as Al Andalus. This period in Spain history is pretty peaceful and is what I consider its golden age. It all changed however when the Reconquista happened. Christian nations from the North of the Iberian Peninsula invaded the Muslim states on the south until 1492 when Christianity reigned supreme in the peninsula.

The Union of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon remained as one of the most important event that ever happened to Spain as it was basically how the country formed. They ruled together as the Catholic Monarchs and they led the country to economic success and made Spain a force to be reckoned with.

3. Germany

- Germany's beginnings is perhaps my favorite out of all the European countries. Before, the teritorry it encompasses today is the Holy Roman Empire, which came from the Frankish Empire ruled by Charlemagne, the Grandfather of Europe. But when Napoleon came to picture, the Empire dissolved and the states within it are left to rule themselves. Then came the time of Hitler, the part of Germany's history at its darkest and grimmest. Thankfully tho, Germany came through and became what we know today.

The part of their history that piqued my interest the most is the disastrous family tree of one of their royal houses, the Habsburgs. The Habsburgs is a family where inbreeding and powermongering is normal and is considered as the supposed way of being a monarch. Its fascinating how it evolved throughout the centuries, from it being a place where pagan barbarians who waged war on Rome lived, to the place where protestantism emerged to change the Christian world forever.

2. France

- France, the country with my favorite language and culture. As mentioned before, it was from the Frankish Empire along with the Holy Roman Empire or as what we call it today, Germaly. Its was once known as the master of contitnents because of its military prowess when it came to land, and it was further proven by the time one man from Corsica was born, Napoleon Bonaparte

The event where im most interested in is the Napoleonic Wars. The thought that a single man and his country versus all of Europe is the most epic thing a man can be known for.

The French Revolution is also a turning point for Europe as a whole, it was a scare to other monarchy because it showed that ordinary and poor people has the power to eat the rich if they are provoked enough.

1. United Kingdom

- My number 1 choice would always be the United Kingdom, the country that got me interested in history. The United Kingdom, being 4 seperate countries in a union, have a rich history that stems all the way back from Roman times. It was first invaded by the Romans in the 43 ad when the place is still locals ruled by the local people. In 410 however, they need to leave England to protect their homeland, Italy. They were left to their own devices until the whole of England united under one ruler and soon all of the british isles followed.

My favorite part in their overall history is the monarchy and how the whole nation managed to play a huge part in world history, from the warring with France in the Hundred Years War to the nations contributions to the fall of Napoleon. They consistently fought with France even if all other countries sided with France.

The history of the United Kingdom will always be my favorite it holds many interesting events and is the place of some of the most well known names in history such as Shakespeare, Queen Elizabeth ii, and many more.

0 notes

Text

Kaminari: Sensei, which pride flag is that?

Aizawa: ...

Aizawa: ...Germany?

#mha#incorrect mha quotes#bnha#my hero academia#boku no hero academia#incorrect bnha quotes#funny bnha#funny mha#anime#kaminari denki#chargebolt#jirou kyouka#kamijirou#pride#germany#i dont know he’s just an idiot ig#shouta aizawa#eraserhead#i am aware that hitler was born in Austria

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Musings on “white guilt”

Recently I have come to think about the term “white guilt” and how I personally feel about it.

Full disclaimer, I am a white woman from an upper middle-class background. I am cisgender, and I have had easy access to good education. And while I am a bisexual woman, of which both factors come with their own forms of discrimination, I thankfully live in a country (Austria) where things could be far better, but they are better than in a lot of other places in the world. In other words, as far as privileged goes, I’m pretty far up there.

“White guilt” is often dismissed by people because “while, yes, my ancestors did terrible things, but I didn’t so why should I feel guilty? I’m not the one doing it.” And in theory I would agree. I did not commit those atrocities. I did not force people into slavery. I did not slaughter Jews in gas chambers. I did not kidnap, steal, loot, or kill. My ancestors did. And I do not feel guilty about their actions, because they are not my own.

However, I still reap the benefits of their actions. I reap the benefits of colonialism, of imperialism, of white privilege, of capitalism. And while I do not think that I am at fault for what my ancestors did, I do think that it is my responsibility, as a member of this society, to recognize the lasting impact of my ancestors’ actions and how they benefit me, and in turn, harm others. With this, I mean both on a grander scale, as in white Europeans, and a smaller scale, as in my direct family.

My father is English and my mother is Austrian. In other words, my ancestry has blood on their hands on both sides.

My grandmother was a Nazi. Not in the sense that she put people into concentration camps and joined the SS, but in that she benefited from the Nazi regime and stood by and did nothing. Sure, I can explain why she did it. She was born as a child out of wedlock and was thus denied many of her pier’s opportunities and Hitler, in order to increase his following, declared after the “occupation” of Austria that he would act as godfather to all illegitimate children and by doing so declaring them legitimate. This opened up many new venues for her. Offering her education and economic possibilities.

I can explain why she did it. That doesn’t make it excusable. My mum would always tell me that my Grandma was a highly confrontational person. My mum always said to my grandma, if she had had a Jewish friend, she would have gotten herself killed trying to protect them. But she didn’t have Jewish friend. The Holocaust did not affect her personally and so she did nothing. And while I loved my grandma in the short time I knew her – she died when I was 7 – I can now recognize that her actions, or rather her non action, where wrong. In a way, I am selfishly glad that she didn’t resist. Otherwise I most likely wouldn’t be alive today. However, if she had spoken up, or if she had aided in helping shield people from the Nazis then I think it would have been worth it anyway.

My legacy is that I am alive, that I am able to exist because my grandmother aided a system that killed millions of people. That is the legacy I inherited.

(Side note: I was always aware of that fact in the back of my mind, but after I wrote that last sentence it hit me like a freight train and started literally crying so hard I had to take a break from writing this.)

Of course, there are a million other ways I could go further into my Austrian side, but let’s move on my English side.

I cannot trace my lineage back directly to a specific circumstance where my English family did something terrible, but I can look at the larger scale.

England’s history is deeply steeped in colonialism, imperialism and slavery. Yes, England itself experienced great economical growth and advances in technology, but it did so by exploiting its own working class and ultimately supporting itself by robbing other countries of their culture, their recourses and their people. And they justified their actions by calling it the natural order. That they were genetically superior.

I am not the person to tell you about this. I am not the most qualified person to talk about this and I will always miss the subtle nuances that people from minority groups, who directly feel the legacy of slavery and colonialism, will experience. (Black People, Indians, Native Americans, etc…) It is always best to read as much as possible from minority voices to get a more nuanced and detailed view on the issues they have to deal with.

What I am getting at, is that lot of the advantages that I have stem from exploiting People of Colour, directly or indirectly. My parents both grew up dirt poor, but they got to the point they are now because they managed to get good education, and well-paying jobs in highly respected fields. I am proud of their accomplishments (especially my mum who grew up at a time when she wasn’t allowed to wear pants and is now a highly respected head doctor at the local hospital) and I do not want to diminish their accomplishments because I know they worked their asses off to be where they are now. (again, especially my mum) However, I am nevertheless aware that they were ultimately aided along the way by white privilege and cis privilege and straight privilege, and in the case of my dad, male privilege. If either of them had been, for example, Jewish, or Black, or not straight, or not cis, then they probably would have had to deal with discrimination behind every corner.

In the face of this awareness it is ultimately not my job to feel guilty, but it is my job to be aware of the legacy my ancestry left me; how it benefits me and how it harms others. And it is also my job to fight against the injustices caused by this legacy. Because no, it is not my fault, but is my duty as a human being to attmept to right the wrongs in this world, to support minorities anf fight for their rights and freedoms and to look at the legacy I was born with.

#racism#politics#history#white privelege#people of color#black lives matter#intersectionality#white guilt#self awareness#austria#england#leftist#left wing#allyship#2018#colonialism#imperialism#nazi

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My grandpa’s experiences in a Russian POW camp have been turned into a book.

Hi everyone. Today, I’d like to talk about something very personal, yet something that I think is very important to people in general. And to do that, we need to start with a bit of a history lesson.

Most of the people reading this I probably aware that I am French. Well, I was born and still live in Alsace, the easternmost region of the country, whose Eastern border is also the border between France and Germany.

Needless to say, this means that we’ve seen our fair share of conflict, as the two nations have been fighting over us, as well as another region called Lorraine, since... pretty much these two nations have existed. So unsurprisingly, one of the conditions of France’s surrender to Germany during World War 2 was that these two regions would be annexed, meaning they were officially part of Germany, meaning that all able-bodied men in these regions could potentially be drafted in the Wehrmacht, despite not being German. I’ll let you guess what happened to those who tried to refuse, and/or their families.

This happened across multiple countries and in France, we call them the “Malgré-Nous”, which translates to “Against Our Will”, and my grandfather was one of them. And because the Germans of course would rather not risk their superior homeboys, these people forced into the army were sent to fight off the Russians.

At some point, my grandpa’s squad ended up surrounded by Russian forces. They tried to flee, but were eventually caught and taken prisoners. They were sen’t to various prisoner camps, and ended up spending most of their time in the infamous Camp 188 in Tambov.

Now, this was a POW camp, the soldiers there were a bargaining chip for Russia, so they weren’t going out of their way to make people suffer or starve them, but this was a POW camp in soviet Russia, in the middle of the most brutal conflict in human history, so as you can probably guess, the living conditions barley allowed for survival.

I’m not entirely sure why, perhaps just to fight off depression and hunger, but my grandfather decided to keep a journal of it. He even describes the almost slapsticky way in which he had to move his arms around a guard searching him so he wouldn’t see it, and he explains that he eventually sewed hidden pockets inside his coat’s sleeves so he could hide it. It contains not only descriptions of the camp, daily life inside it and the land and wildlife of the area, but he also drew many sketches of what he saw, some of which you can see in these pictures. As an artist myself, I am very proud to see that not only does it run in the family, but he made such an important use of his talent.

Obviously, the journal of a surviving soldier’s experiences in a Russian POW camp is an incredibly rare and valuable document (even my family didn’t find out about it until a few years ago), especially considering the little-known aspect of WW2 of non-German people being forced into their army. Russian people are especially fascinated by this sort of stories because of course, for most of the XXth century, they could only know what their government would allow them to know about their own history.

This is how a French-speaking Russian woman who frequently visits France ended up hearing about the journal in local publications. She had this project of writing a book about the camp, and was looking for first-hand accounts of what it was like. Naturally, as soon as she heard about this, she contacted my parents and asked if she could write about the journal and include pictures of it. It goes without saying that they accepted. In fact, my father had the entire journal scanned in high resolution for just such an occasion (we also intend to have the entire thing printed, with a copy of the letter he received to inform him he was drafted).

Well, as the title of this post says, the book is now complete and its author sent us a copy. Of course, none of us can read Russian, but the author’s daughter is working on a French translation, so I’m very anxiously looking forward to it. There are other people’s accounts as well, my grandpa’s taking up about a third of the book.

Here is the letter announcing he’s been drafted, written on October 24th, 1944. It includes a list of items to get before reporting, such as work shoes, a shovel, a mess kit, etc... notice the “Heil Hitler!” at the end. Also note that although his name was “Geoffrey Rieb”, they of course spelt his name as Gottfried. Similarly, they spelled the name of the street where they wrote this “Rue du travail” (Labour Street) in German, turning it into “Strasse der Arbeit”.

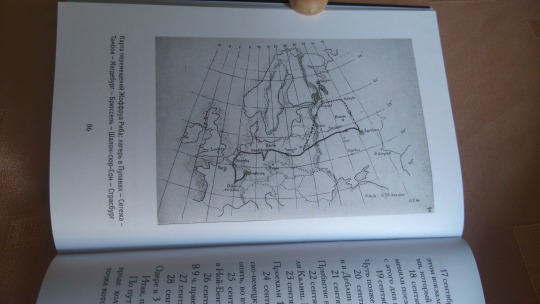

Here’s a map he drew while trying to work out where they were and how much he’d travelled (the guards only spoke a bit of German outside of Russian so they couldn’t provide much information). Oh and one thing that’s not included in the book is that he actually built a makeshift sextant to help in his calculations (note: I believe this specific sketch is from a copy of his journal which he remade more cleanly once he got back home as he clearly realized that all of this needed to be preserved).

On the left page, he specifies the many nationalities the people he met during his “stay” (as he put it) in the camps of Lobsch, Pulawy, Segesa and Tambow hailed from: France, Belgium, Luxembourg, ¨Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yougoslavia, Estonia, Lettonia, Hungary, Italy, Romania and Austria. He explains that all prisoners except for the Germans wore caps with their national colours on.

He also adds that in each camp, you had an easier time depending on your nationality: if you were Austrian in Lobsch, German in Pulawy, Polish in Segesa, and in Tambow... you had to be a teacher. It’s a bit of a joke since the camp almost exclusively included French prisoners, to the point it ended up being nicknamed “The French camp”.

On the right page is a sketch titled “Those who aren’t coming back.....” and depicts the Alsacian graveyard of Tambow. Yeah, let us not forget that around 8000 people died there. My grandpa was one of the lucky ones.

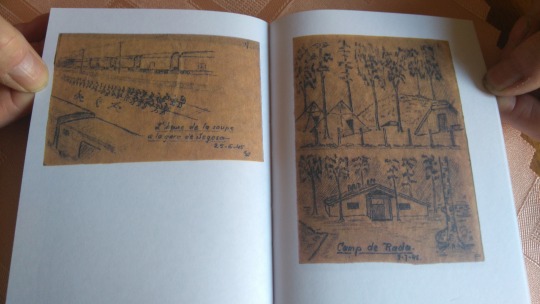

To the right is a sketch of another camp he went through, Rada. To the left is one of my favourite sketches, of which you can see a variation on the cover, of “Soup time at the Segesa train station”. These lines of people eating what little they could get is really striking. But what really stuck in my mind is an anecdote my grandpa relates. I’m not sure it was exactly at that moment, but on his way back, he mentions stopping at a train station and being so hungry he decided to trade his sweater for a sausage.

I wish nobody to ever be so desperately hungry that they are willing to literally trade the clothes on their backs for a sausage, in the middle of Northern Russia. And I wish for nobody to be desperately cold that they’re willing to trade what little food they have for a sweater.

It’s not all cold, hunger and sadness though. There are sketches of the beautiful nature, some amusing stories like the prisoners organising a football tournament, even being able to form national teams, some heartwarming moments like my grandpa making plans for renovations in their countryside home (which he eventually did make!).

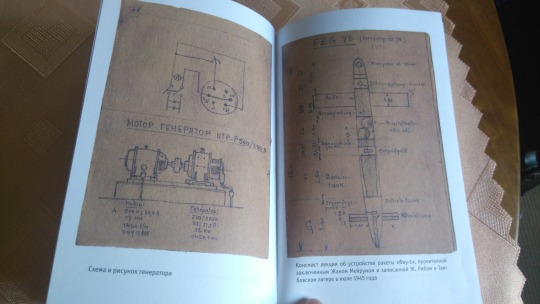

And then there are also some truly incredible moments, like when the prisoners decided to take turns giving each-other lectures on their job. This is what the sketch on the left in the top picture is for, as it describes one of the machines my grandpa used for his job.

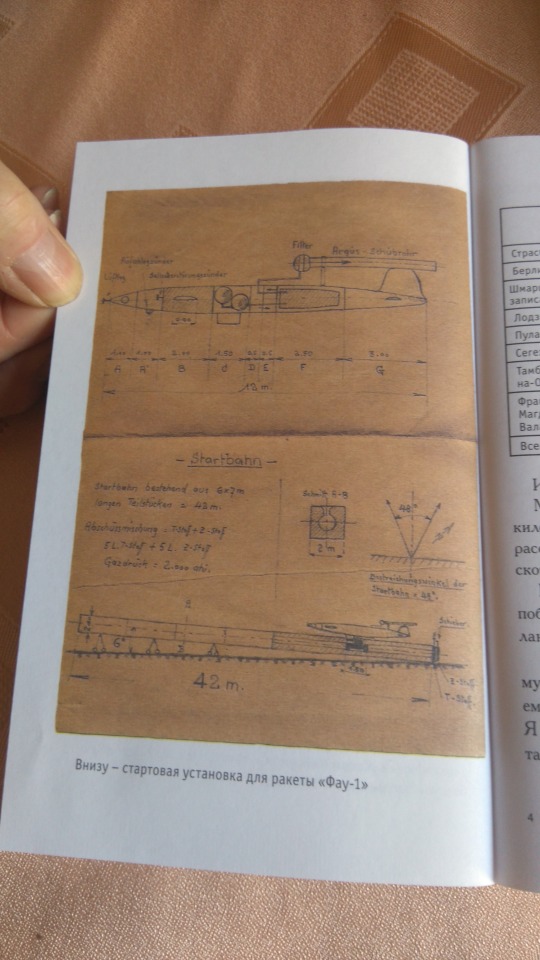

But that’s not what makes this story incredible. See, one of the people giving a lecture was a German engineer. And the sketch on right page and on the bottom pic are blueprints my grandpa was able to make based on descriptions by that engineer. You may have noticed it looks like a rocket. And if you look carefully at the top right sketch, you may have noticed the name V1.

That’s right, this guy was a military engineer, giving the prisoners a lecture on Germany’s signature weapon. now I’m going to go ahead an assume this sort of information was top secret, with major consequences should any info about it leak, and yet here it is in my grandpa’s journal. This blew my mind when I first saw it and I wondered if I was seeing this right.

This to me can only mean one of two things: either this guy expected to die in this camp, so he wasn’t scared for himself should the Russia get a hold of it and he was branded a spy and/or a traitor back in Germany, but even then you’d think he wouldn’t want to endanger his nation, or at least he’d fear for his family, or he knew that even if the Russians did find the blueprints, the Nazis would have fallen out of power by the time word got back to Germany. Either way, I’m still having a hard time comprehending that this is real and my grandfather got to hear it straight from one of the engineers.

But this also speaks volume about the situation these men were in. They were all trained, indoctrinated to hate and want to kill one-another. Propaganda was everywhere on all sides of the conflict. Just look at how hateful some of the European or American war posters were. And in Germany, we’re talking about a Nazi dictatorship, a regime raising an entire generation to believe that genocide was the right thing to do, so the incitement to blind hatred was especially strong.

And yet, here they all were, talking to each-other, educating one-another, exchanging ideas, trading as equals, ignoring nationalities, ethnicities and culture. Because when you’ve hit rockbottom, when you’re all neck-deep in the same shithole, tired, starving, and unsure if you’ll still be alive by the end of the week... who can still give a crap about such petty issues? I get the feeling that for them, the war was over long before any treaty was signed.

I hope you found this as interesting as I did and that it’s giving you a new perspective on World War 2, that conflicts are always so, so much more complicated than “good guys vs bad guys” and how the people most directly involved by it wanted nothing more than to live in peace and let their neighbours do the same.

For me, it’s also a very personal document, as my grandpa died when I was still very young and I don’t have many memories of him, so finding this helps me connect with him a little bit more. I’ll keep you posted when the French version is completed and who knows? Maybe we’ll make more. I just know I want as many people as possible to know about this. Remembering these events is our duty to the World and to future generations.

Oh and if you have any questions regarding this, feel free to ask, I’ll answer them to the best of my avbilities.

#personal#history#World war 2#World war II#WW2#world history#war#Russia#POW#prisoner of war#France#Germany#Tambov#Tambow#camp#camp 188#humanity#family#sketches#sketch#journal memories#memory#perspective

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

INTERVIEW WITH HANS WEISS

Hans Weiss was born in Hittisau, Vorarlberg, Austria in 1950. He studied Psychology, Philosophy, and Pedagogy at the University of Innsbruck where he did his Ph.D. in 1976. In 1978 he completed a postgraduate course in medical sociology at the Vienna Institute for Advanced Studies. He received a research grant from the British Council with stays at the Universities of Cambridge and London in 1978/79. In 1980, he worked as a pharmaceutical consultant, collecting material on the business practices of the pharmaceutical industry for journalistic reasons. Based on his research, he wrote two books “Gesunde Geschäfte” and “Bittere Pillen,” which caused a sensation at the time. “Bittere Pille” sold more than three million copies in the meantime and became one of the greatest German-language book successes. From 1994 - 1995 he trained at the International Center of Photography in New York and in 1997/1998 as well as in 2010/2011 at the School of Artistic Photography in Vienna.

On April 1, Deutsches Haus at NYU presented the opening of the exhibitoon “The Towers of Babel” by Hans Weiss. His exhibition will be on view until June 7.

Your current photography exhibition at Deutsches Haut at NYU captures the view from the 10th floor of NYU’s Bobst Library, from the same spot, between 2014 and 2018, at different times of the day and during different seasons. What made you choose this particular spot?

Whenever I stay in New York - usually five or six weeks every year - I use the reading room on the 10th floor of Bobst Library as my work space. It is quiet, I am surrounded by students and books, and I have this great view in front of me: nature (Washington Square Park) and culture (Manhattan skyline with Empire State and Chrysler Building). There are huge windows from floor to the ceiling and even though it is always the same view, it is also always different: changing lights, changing colors, changing impressions.

The photos in the series “The Towers of Babel” were all taken with an iPhone. Why did you choose this medium over a traditional camera?

I started the project not knowing that it would become a longtime project. I use my iPhone regularly as a visual diary. So, the first pictures were shot for private memory. I only started thinking about turning this body of work into an exhibition in 2017. Until 2017 I used an iPhone 4 and after that an iPhone 8. Photographically there is a big difference between the two: I can enlarge iPhone 8-prints a lot bigger than iPhone 4-prints. I am surprised about the quality and the sharpness of the photos. I think it has to do with the fact that I did not take the pictures by holding the iPhone in my hand, but pressing it to the window - with the same stabilizing factor like using a tripod. Using a traditional camera would have meant carrying it with me all the time, which is bulky and heavy.

You have spent four years documenting New York City’s skyscrapers. When you first set out, did you think it would take four years to complete this project? How many pictures did you take during this time and how do you go about the editing process?

When I started thinking of this as a serious project, I did not set myself a deadline. Although in my mind the project is finished, I still take pictures at Bobst Library. When you have run a long distance, it takes some time until your pulse is back to normal. After I showed some of my pictures to Juliane Camfield in 2018, I was invited to exhibit them at Deutsches Haus at NYU. I was happy but at the same time scared. How to select a small number of pictures out of about 3000? How can I bring them into an order which makes sense?

By chance I came across a famous picture from the Dutch painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder: “The Tower of Babel” (1563). It illustrates a story from ancient times. People started building a tower, to reach the clouds and the sky. It was the first skyscraper. God, who was an almighty figure at that time, felt offended and punished the builders. Everyone was given a different language and all of them were scattered all over the world. My series symbolizes the opposite of this story. People from all places on earth come to New York. They build skyscrapers, they speak 170 different, languages and they understand each other and feel united and at home.

To bring order to the infinite diversity of the world, artists, writers, and philosophers of Pieter Brueghel��s time used magic numbers like 7 or 4. For example, seven vices or four cardinal virtues. This was an important artistic tool in ancient and medieval times - and it helped me too.

In the exhibition you see 4 times of the day, 4 seasons, a group of 4 pictures with the universal topic “love,” and a group of 4 “virtues,” which I defined as curiosity, hard-working, ambition, and dream. Dream not in the meaning of Sigmund Freud’s teaching, but in the sense of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” - a very conscious effort of creating a better world. In addition to these four groups of four pictures there are 7 pictures representing “emotions”: fear, pride, sadness, courage, hope, anger, joy - scattered all over Deutsches Haus at NYU.

Are there any particularly memorable experiences from your time in the library that you would like to share with us?

In the fall of 2015, when I was a regular at NYU’s Library, I exchanged a few friendly words with a staff member named Allan. A short time later we became friends. Allan’s Jewish father, who came from Freiburg in Germany, survived Hitler, because in the 1930s he had read Hitler’s infamous book “Mein Kampf.” He was shocked and thought: “Oh, that sounds life threatening for the Jewish people!” Allan is serious about what he writes. He called his family to immediately leave Germany, but they were hesitant. He was the only one who left for New York - and the only one who survived the Holocaust.

Allan’s mother came from Vienna. She was half Jewish. During the Nazi era, she was a member of an underground resistance group, which helped Polish Jews fleeing via Vienna to Hungary - which until March 1944 was allied with Germany, but still an independent state. Therefore, Jews were not deported and killed like in Poland or Austria. But the resistance group was betrayed and the German secret police “Gestapo” caught all members, including Allan’s mother. She was sent to the concentration camp “Ravensbrück” in Germany, but survived. After the war, she spent some time in Vienna, but because the eastern part of Austria was occupied by the Soviet Union, she saw no future by staying and emigrated to New York, where she met Allan’s father.

Allan himself now owns several houses in the Catskills, which he only rents out to very poor people. He does not make any money with that, but he sees this as a moral and spiritual commitment to his mother’s attitude: Helping other people to survive.

You divide your time between Vienna and New York. How do you perceive these two metropoles? How has living in these two places shaped you as a person and photographer?

Until the 1980s Vienna used to be at the edge of Europe. Kind of a dead city, living from and with the past. Gray, old fashioned, slow pulse. That has really changed. The overall quality of life in Vienna is certainly much better than in New York. Now it is more diverse than a decade ago. A very well-maintained city (public transport and other public services). The museum scene is almost as vibrant as in New York. If you are a lover of classical music or German speaking theatre or timeless sitting in a coffeehouse or “dolce far niente,” then Vienna is the right place to stay. I love New York, because it is so fast and dense and New York people are the friendliest and most open minded in the world in my opinion. Vienna is a great place to raise kids and live an easygoing life, but for me it is honestly a bit boring. Whereas New York is an exciting place for photographers - in this regard I feel at home here.

Your fiction and nonfiction books sold more than five million copies and are translated into 20 different languages. What are the main differences in your approaches to writing and to photography?

For about three years now, I have become more interested in photography than in writing. Before that, I made my living mainly with non-fiction (books and reports for big German magazines). However, from time to time I also wrote literary pieces. Some non-fiction books were the result of huge undercover projects like working as a salesman for big pharma companies - to find out, how they bribe doctors and use patients as guinea pigs. These projects were very demanding and adventurous. You have to organize so many things at once, you have to be constantly aware of yourself playing a role, and you have to be on alert all the time as well as take enormous personal and legal risks. After all, you have to write, which is the most demanding effort. I know quite a few very successful writers. And with only one exception they all think, that writing is a terrible job. The thinking, the editing, the re-writing, the polishing of the words! Awful! But when you have finished something, it is great! Fiction writing is another thing altogether. Did I change the world with my writing? Well, maybe here and there, a little bit, I hope. But all in all, it is rather disappointing, I have to admit.

Photography is very different from anything I write. For me it is more emotional, more spontaneous. At the beginning of photo-projects, I do not think a lot about it. I am more instinct-driven, like an animal. I shoot and I instantly see the result. And only then, possibly, I start thinking. About light, shape, color, improvements, quality, meaning. After that there is the rather technical part of the job: Thinking in files, pixels, color grades, density, and so on. And transferring the images into images and prints, which are of interest for others. And all the organization, which is necessary for an exhibition.

What projects (either in writing or in photography) are you currently working on?

Currently I am working on three photo-projects: First, on portraits for which I use an app in the wrong way. The pictures look like portraits the cubist painters produced in France at the turn of the last century: distorted, divided, and reassembled. Second, I am currently working on “Tourist” which is a longtime project I began in 1996. Third, I am working on “Smoke” which has nothing to do with cigarette smoking. And I also began writing my autobiography.

0 notes

Text

3. Math Kid, Soldier

I became radicalized during the summer of my junior year, I was seventeen years old. At the time I was on academic exchange in Northern England, conducting research of minor importance on the pretense of scientific giftedness. My brilliant peers have pruned my confidence, so I stumped and sulked in the coldish air. I could not communicate properly with my advisor, a loving Frenchman who is battling for tenure, because he does not care for mathematical terms in English. Decidedly, I wanted to exploit what was left in my life, so I began to take walks in the diagonal of the college campus. The campus being a perfect square with hundred-meter sides, the diagonal was the only radical path in the campus square, and on my morning walks I often encounter Taki. I have been meaning to make friends with her, for I found her the least miserable and anxious out of all my peers. Soon I learnt that Taki will not joke around with me, but she meant all the best and would gladly talk about any scientific topic. The formality and rigor of our friendship is surprising, but certainly welcome.

I had just began writing my exposition in mathematics, when I became one with the symbology. When I began what my advisor called my projet petite, I wished to find an analog of the spiral of Theodorus in complex numbers. The plenitude of radicals signs, half-bent roofs over numbers, reminded me of the temporary nature of our lives. I thought about the sick and dying in nursing homes, including, perhaps, distant members of my own family that I was too preoccupied to know by name. Presently, I began to see all numbers as ugly and writhing in skeleton and flesh. Although only ten basic forms existed, the infinitude of naturals, integers, rationals, and reals were allelic for the finite mess of ways to be human. I was shaken and endeared, and I was unable to sleep, and I kept making correlations. For example, the number seventeen over thirteen is a newborn from Singapore born in the hospital of this very university, and the number six point five five is my dear advisor. The ubiquitous e, I felt, was simply the blue-collar worker. I had read about these types of people on Facebook, the crockpots who claim they see through mathematics into universal truth. I had never doubted their madness — for mathematics is only one pathetic language among many — but upon my vision I feared becoming one of them. To forge a personal, almost familial relationship to symbology was the first sign of my radicalization, but I denied it to be a symptom. After writing two more pages of my exposition, I was convinced that my logical faculties remained unclouded despite my vision. I decided against telling Taki, for I was sure she would take it as a joke, and I feared losing her friendship. For the next week I indulged in my vision whenever possible, writing down a summary at the end of the day for the pairings I have produced. The most significant were: the constant pi for refugees, migrants and people in movement, the number zero for Ethiopian women who live to be eighty years old, the number one for an Austrian violinist turned Tibetan monk, and the number three hundred forty two point six five for myself. After performing a preliminary bivariate test, the correlation between location, gender, or occupation and the nature of the numbers were perfectly random. Complex numbers were surprisingly absent from my vision, perhaps because they were the subject of my thesis. My writing was uncannily successful, and I finished my exposition a week ahead of time.

My conversations with Taki slowed my deterioration. We took to sitting on the donated bench after our morning stroll, although we walked in opposite directions. I did not care for her iPod and the classical music within it, but we discussed amicably over scientific ideas that we both understood. The dead fairy godfather of our park bench is one William Shortstorm, who apparently lived a very fruitful forty six years and was survived by his widow Edith. As a Southeast Asian I was unaccustomed to the nuanced mood of the climate, the paradoxically sunny coldness of a British summer. The English was fond of discussing the weather, and I found it justified. The personable gusts accompanied our conversation with equal gusto, and its waking strength reminded me of the youth in Taki’s life and my own. It had not crossed my mind to apply my vision to Taki and assign a number to her. Our friendship was short-lived, and by the end of the program we despised to see each other.

My doomed epiphany came the night before the submission of my exposition. Per my kind advisor’s request, I would read over my writing one more time and make sure that all notation is correct and sound. This fated task, it would seem, sealed the second coming of my inexplicable vision. Performing mathematics, for me, had become emotionally difficult. Although I was able to write down my calculus exercises without question, upon rereading these pages of numbers I was rendered helpless by my visions. The crass pages of my hasty exercises became intricate sketches of central train stations, where all walks of life came to share the misery of waiting. To have all sorts of numbers huddled so close to each other, such kaleidoscopic characters at once! It was difficult to not infer relationships between these people, even for a logical person such as myself. To this end it dawned on me that the mathematical notation represented relationships, not in the sociofamilial sense but in the emotive sense; as a summary of feelings between these number-people. Thus the rereading of my exposition became the disastrous peripeteia of my self-evidently trivial life. I stared at the multitude of radical symbols down the page. It resembled the check sign, as were the German blank cheques given to Austria a century ago, as were all likely struggles between true and false from computers to statehoods to exercise papers like my own. The undiscriminating stoicism of this open symbol, reducing and sheltering whoever comes its way, the same monk, the same privileged children, save the negative numbers — those who refuse to accept who they are. In time, I too, became sheltered under a radical symbol of my own, and I saw how absolutely correct it was. My own square root — could they be my children? Oh, I did not mind, whoever they were — my own square root crawled and seeded within my chest. An immense sense of insecurity and pity came over me: to be sheltered, to be loved, to be cared! — Yet so many could not afford it in this world. For the global capitalist machine had hijacked these numbers and symbology for its own benefit, just as its sentience had robbed life of its meaning. I realized that the precise ingenuity of capitalism was that it used mathematics to eliminate the very truth represented by mathematics. Capitalism, with its monstrous sentience, imposed its own truth upon these number-people, so that mathematical symbology no longer hold meaning beyond the pecuniary for people; for people who are numbers themselves. Truth is no longer truth when truth convinces itself of another truth. I identified it at once: that to eliminate this kidnapper of mathematics was the only means to global emancipation, the only means by which numbers could mean themselves again. Capitalism was an invisible enemy, for it existed around and beyond mathematics but not within mathematics itself. For us, it would mean organized resistance, it would mean armed resistance, it would mean theory-writing and interpretation of Marx and Goldman and Bakunin. Already I am in ruins and shudders. I have not known these names before — I do not understand who they are, save for the numbers they represented. Yet I had never been surer of the next step forward. The radical sign told me to leave mathematics at once: the language of truth had done all it could for me and this world. But my radicalization was not yet complete — as such, nothing is truly complete until it has been set in action.

Impassioned by my newfound mission, I found its actual execution beyond difficult. I could not leave the program, which drags on for one more week; among the daily science lectures and exercises I had emerged as one of the more hopeless of my peers. Taki’s academic standing is mediocre amidst these geniuses, although still above me nonetheless. Yet she does not look down on me: she had asked me to check the calculations in her exposition on astrophysics. But I found that I could no longer complete tasks as simple as these. After taking her pencilled notes and printed exposition back to my room (with plenty airy dandelions on the way, the wind still cold but embracing), I read over it carefully. But I could not edit it — I began to cry. I have not seen any scene as tragic as this — an entire people, an entire people of diversity and voluptuous history, subjecting themselves to suigenocide in defiance of — well, of Taki’s treatment of them. Why does she subjugate mother to son and invert families and ages? Why does she tie them up and feed them their own body parts? Why does she project one number upon another and doing so, destroy both heartlessly? There were but scientific sweet nothings on the page, but I saw concrete blood and corpse and innumerable human suffering. I could not believe that any dictator, fascist in human history could write anything half as cruel as this — and certainly not Taki. She had been nothing but polite and poignant during our friendship — how could I have known of her hidden cruelty! Indeed, how could herself be aware, and how could she understand my vision? Of course, I had no nuanced understanding of my unique situation back then. All I could do was rush to Taki’s room and knock on her door and give an infuriated spiel. I called her, indeed, worse than Hitler. Taki took great offense to this — and rightly so — her Japanese-American family had suffered considerably in the Second World War, and Taki does not forget easily. She had every right to react this way, for I had not explained properly. Nor had I time. When I returned to my pathetic room it was midnight, and I decided that my friendship with Taki had been destroyed sacrificially. With Taki gone, I had nothing to tie me down to the world anymore. I was past the point of inflection. From now onwards, along the t axis, nowhere but onto infinity.

Every coming day I itched for the program to end so I may board the flight home. I continued taking my daily stroll along the diagonal, one of the few activities that still grounded me to reality, and I noted Taki’s natural absence from the route. My advisor was surprisingly delighted with my paper, given that he had contributed zilch to its inception or completion. He told me that he would pass the paper around to other advisors and discuss potential publication. I did not care for his propositions, all I wanted was for this meeting to end, and thus for all math things to end. On the final day of the program I was awarded the best written exposition award. This came as a surprise for myself and an upset for my peers, for nearly everyone had rightfully looked down at my mental faculties. I saw Taki when I went on stage to accept the award. She was clapping; she was still angry. I have not seen her since.

As I landed in the airport of my home country, I immediately destroyed my cellphone to avoid being found by my chauffeur and parents. I counted the money I have on me, which was a comfortable sum. I purchased a second cellphone and SIM card, and I immediately knew who to contact. She was invited to my school to do a presentation on activism, which I yawned over at the time, and she was scantly remembered by my peers. Strangely, I did save her phone number — I was a number hoarder long before my epiphany. I called her at once: I addressed her as prophet, sage and saint. I told her that I was a student at her presentation, and that I am enlightened and I am ready to devote all myself to her cause at once. She was generous enough to not enquire further, but she gave me her address. I called a taxi there at once. Upon arrival at the polished middle-class home I proceeded into the attic and threw myself onto her. I told her about my vision and I sobbed incessantly. This group of strange old hippies must have decided that I was properly mad, but still of proper usage to them. They were Trotskyites, terrorists. I told my matrons that I could stay indefinitely.

Obviously, I had partially thought this through: my father and grandmother wield considerable political power in the city, so a public search ad would be out of the question. On the other hand, my presence under the wings of this underground group could be an immense threat to my life. I hid my passport from them and used a general name. I was not asked to justify why I attended a private preparatory high school. They were merely glad I joined the cause.