#international phonetic alphabet

Photo

xkcd is making a vowel hypertrapezoid

#linguistics#xkcd#linguist humour#vowels#vowel trapezoid#ipa#international phonetic alphabet#linguistics comics#comics

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

niche ass post feel free to disregard:

as a linguistics nerd, it’s always fascinating to me how dan and phil both manage to mispronounce so many words but always in a different way to each other. like “consummate” in the most recent dapg vid? dan pronouncing it consjumate/consyoomate and phil pronouncing it conʃumate/conshewmate and neither of them acknowledging they said different words? adding a palatal approximate (/j/ or “ya”) i can excuse kind of but i cannot find a single instance of adding a postalvelar fricative (/ʃ/ or “sh”) being accepted pronunciation. oh to be a fly on the wall in the phouse getting to gather linguistic data on them, then making a corpus of phanology (phorpus, if you will) <3

#jk i would not want to be a fly on the wall in the phouse#if for whatever reason i was ever invited to the phouse i’d say no thank you#dnp#dan and phil#phan#lingblr#linguistics#phanology#convergence#at this point dan and phil use a pidgin version of english only they know#good for them my best friend (who is getting the same degree as phil did) also have our own pidgin#this was the least pretentious way i could write this post btw#be thankful i didn’t write consummate in ipa#i can in the tags i guess#dan: /kɒnsjumeɪt/#phil: /kɔnʃʊmeɪt/#that’s my transcription but i also can’t hear lmao so who knows#yeet my deenp#yeet my deet#international phonetic alphabet#ipa

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

do you think IPA symbols give their girlfriends their brackets when they get cold

#langblr#language#language blog#languageblr#text post#text#late night thoughts#shower thoughts#ipa#international phonetic alphabet#linguistics#phonetics#pun

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

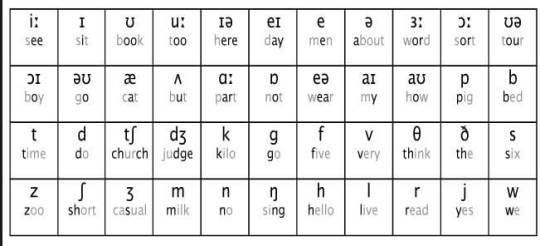

International Phonetic Alphabet.

I have seen enough posts with words transliterations written with how english speaking people hear and pronounce them. It's a somewhat faulty way because, well, first of all, English accents exist, so how a USAmerican person would transcribe a sound would defer from an Aussie person, for example.

Let me introduce a simple miracle tool:

International Phonetic Alphabet.

I am not going to retell the history of it. But it is the most comfortable linguistic tool insofar. It's a standardized representation of speech sounds in written form.

Here is a simple chart.

So if I wanted to transcribe a word of 'definitely' it would look like this: ˈdɛfɪnɪtli.

I think everyone would benefit from learning IPA. If you don't want to, though, there's this very helpful site that would do the transcription for you! No more deciding if you want to write down 'ides of March' as 'ai-deez' or 'eye-diz', you can write 'aɪdz ɒv mɑːʧ' and avoid all of the confusion.

Truly, one of my favourite linguistic tools.

#linguistics#IPA phonetic notation#international phonetic alphabet#languages#ides of march#sansael talks

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

*puts Troy and Abed in the Morning mug next to IPA chart mug* Troy and Abed learn phoneeetics!

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welsh LGBTQIA+ Terms IPA Pronucniation:

Anneuaidd- Nonbinary /anei̯ai̯ð/

Anrhamantus- Aromantic /anr̥amantɪs/

Anrhywiol- Asexual /anr̥ɪu̯jɔl/

Cwiar- Queer /ˈkw̥ʰjar/

Cyfunrhywiol- Homosexual /ˈkəvɪnr̥ɪu̯jɔl/

Deurywiol- Bisexual /ˈdei̯r̥ɪu̯jɔl/

Hollrywiol- Pansexual /hoːɬr̥ɪu̯jɔl/

Hoyw-Gay /ˈhɔi̯.u/

Lesbiaidd- Lesbian /lɛsbi̯ai̯ð/

Rhyngryw- Intersex /r̥əŋr̥ɪu̯/

Rhyweddgwiar- Genderqueer /r̥əwɛð'gw̥ʰjar/

Trawsryweddol- Transgender /trau̯sr̥əwɛðɔl/

Following the previous post, my informal/casual transcription left too much ambiguity, so I've taken it upon myself to learn the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to help make things a lot clearer for those interested.

#Welsh#IPA#international phonetic alphabet#Cymraeg#Cwiar#LHDT#cymraeg#cwiar#hoyw#trawsryweddol#deurywiol#lesbiaidd#cymru#welsh#lhdt

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

everyone wake up, new smiley just dropped

̆͗̈

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The sound that √-ǂ makes still haunts my dreams at night

936 notes

·

View notes

Text

guys i think i just discovered a new consonant

ok so you know the /f/ sound is usually formed by putting your lip to your teeth? well a while back i got curious and wondered what would happen if you made a consonant sound with just your teeth touching and it made what i'm pretty sure is a completely unique sound. like it's not on the ipa chart or anything. i checked.

did i actually come up with a new fucking consonant? am i losing my mind?

(btw if you can't figure out how to make the sound, just wince and treat that like a consonant.)

#language#languages#conlang#conlangs#constructed language#constructed languages#consonant#consonants#ipa#international phonetic alphabet#linguistics#what the fuck#wtf#thinking of calling it the “bidental fricative” or some shit

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

[v] ? Yeah, I wish someone would dentally frick my labia until I'm vocal.

#lesbian#linguistics#linguist humor#lesbian humour#lesbians#IPA#international phonetic alphabet#cunninlingus#or should I say cunninlinguistics?#Women!#[v]

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

(if you have an idea of how you'd pronounce it, but you're not confident, just go with your gut!)

#language#linguistics#english#international phonetic alphabet#polls#pronunciation#pathos#inspired by me seeing the pronunciation on wikipedia and going WHAT??#(don't look it up before you answer though!)#also the options are sorted alphabetically to avoid bias#mine

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 90: What visualizing our vowels tells us about who we are

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘What visualizing our vowels tells us about who we are'. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Gretchen McCulloch.

Lauren: I’m Lauren Gawne. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about plotting vowels. But first, we have a fun, new activity that lets you discover what episode of Lingthusiasm you are. Our new quiz will recommend an episode for you based on a series of questions.

Gretchen: This is like a personality quiz. If you’ve always wondered which episode of Lingthusiasm matches your personality the most, or if you are wondering where to start with the back catalogue and aren’t sure which episode to start with, if you’re trying to share Lingthusiasm with a friend or decide which episode to re-listen to, the quiz can help you with this.

Lauren: This quiz is definitely more whimsical than scientific and, unlike our listener survey, is absolutely not intended to be used for research purposes.

Gretchen: Not intended to be used for research purposes. Definitely intended to be used for amusement purposes. Available as a link in the show notes. Please tell us what results you get! We’re very curious to see if there’re some episodes that turn out to be super popular because of this.

Lauren: Our most recent bonus episode was a chat with Dr. Bethany Gardner, who built the vowel plots that we discuss in this episode.

Gretchen: This is a behind-the-scenes episode where we talked with Bethany about how they made the vowel charts that we’ve discussed, how you could make them yourself if you’re interested in it, or if you just wanna follow along in a making-of-process style, you can listen to us talk with them.

Lauren: For that, you can go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm.

Gretchen: As well as so many more bonus episodes that let us help keep making the show for you.

[Music]

Gretchen: Lauren, we’ve talked about vowels before on Lingthusiasm. At the time, we said that your vocal tract is basically like a giant meat clarinet.

Lauren: Yeah, because the reeds are like the vibration of your vocal cords – and then you can manipulate that sound in that clarinets can play different notes and voices can make many different speech sounds. They’re both long and tubular.

Gretchen: We had some people write in that said, “We appreciate the meat clarinet – the cursed meat clarinet – but we think the vocal tract is a little bit more like a meat oboe or a meat bassoon because both of these instruments have two reeds, and we have two vocal cords. So, you want to use something that has a double vocal cord.”

Lauren: I admit I maybe got the oboe and the bassoon confused. I thought that the oboe was a giant instrument. Turns out, the oboe is about the size of a clarinet. Turns out, I don’t know a lot about woodwind instruments.

Gretchen: I think that one of the reasons we did pick a clarinet at the time is because we thought, even if it’s not exactly the same, probably more people have encountered a clarinet and have a vague sense of what it looks like than an oboe, which you didn’t really know what it was. I had to look up how a bassoon works. We thought this metaphor might be a little bit clearer.

Lauren: Yes.

Gretchen: However.

Lauren: Okay, there’s an update.

Gretchen: I have now been doing some further research on both the vocal tract and musical instruments, and I’m very pleased to report that we, in fact, have an update. Your vocal tract is not just a meat clarinet, not just a meat bassoon, it is, in fact, most similar to a meat bagpipe.

Lauren: Oh, Gretchen, you found something more disgusting. Thank you?

Gretchen: I’m sorry. It’s even worse.

Lauren: Right. I guess the big bag – a bagpipe is made of a bag and pipes – the bag acts like your lungs. The lungs send air up through your vocal folds as they vibrate to make the sound. You do have a bag of air, just like in the human speech apparatus.

Gretchen: That’s a good start. What I didn’t know until I was doing some research about bagpipes – because the lengths that I will go to for this podcast have no bound – is that a bagpipe actually has reeds inside several of the pipes that extrude from the bag.

Lauren: Because there’s multiple sticking out in different spots.

Gretchen: There’s the one that you blow into, which doesn’t have a reed, but then the other ones, there’s the one with the little holes on it that you twiddle your fingers on and make the different notes, and then there’s also some other pipes up at the top. They also have reeds in them. Those reeds are just tuned from the length to a specific level. You know when you hear someone start playing the bagpipes and there’s this drone? [Imitates bagpipe sound] The sort of single note? That’s because of the note those reeds are tuned to in the other pipes that don’t have the holes in them.

Lauren: Ah, they’re not just decorative.

Gretchen: Right. They have this function of giving this harmony to the melody that’s being played on the little pipe with the holes in it, which is technically known as the “chanter,” but this is not a bagpipe podcast despite appearances to the contrary. We will link to some people on YouTube telling you more than you ever wanted to know about how bagpipes work if you want to go down that rabbit hole. But if you had an extra pair of hands or two, or a couple people helping you sort of reaching around your shoulders – this metaphor’s getting weirder by the minute – and you cut a bunch of little holes in the other sticking-up-the-top pipes –

Lauren: You would have less droning, and you could play multiple melodies or multiple notes at the same time. Hm.

Gretchen: At the same time. With this, you could make a bagpipe play something very close to vowels.

Lauren: Ah, cool!

Gretchen: This is so cursed.

Lauren: I mean, yes. Before we even talk about making it out of meat – it’s deeply, deeply cursed – it kind of reminds me of this instrument from the early 20th Century called the “voder.”

Gretchen: Would I pronounce that “vo-DUH” or “vo-DER”?

Lauren: With the R at the end.

Gretchen: Okay, “voder.”

Lauren: Thank you, convenient rhotic speaker here.

Gretchen: I’m glad to be of service.

Lauren: It kind of looked like something between a little stenographer’s keyboard and a piano, and with a whole bunch of finger keys and foot pedals you could manipulate it to make something that sounds like human speech.

Gretchen: Ah, wow. And this is pretty old?

Lauren: It’s from like the 1930s. There’s a little, short video snippet in one of the links in the show notes.

Gretchen: You could play these chords, and also have some consonants somehow, and end up with something that sounds like a synthetic human voice.

Lauren: Yeah. A lot of the early computer speech synthesis, as well, was actually quite good at making things that sounded like vowels. It turns out a lot of the consonant things are a little bit harder to do, but the very basic sound of vowels, as you say, you could play it with just a few bagpipes very carefully re-engineered.

Gretchen: I guess if you’re looking at instruments that can play multiple notes at the same time, we could also say that the human is like a meat piano.

Lauren: Right.

Gretchen: Or at least you could make vowels on a piano by doing a sufficiently complicated sequence of weird chords, like notes at the same time.

Lauren: I mean, we also have an instrument that’s known as the human voice. Humans are very good at singing. We possibly don’t have to engineer all these cursed things to get to that.

Gretchen: Okay. Let’s talk about the human voice as itself. We start with the vocal cords or folds. The tenseness or looseness of the vocal folds is what produces pitch. Then they go through the throat, which we can think of as one tube. Then they go through the mouth cavity, which we can think of as a second tube. Each of these tubes bounces around the sound in different ways to add two additional notes – one from the throat, one from the mouth – onto the sound that’s coming out, which is what makes it sound like a vowel to us.

Lauren: You can map the physics of air moving through the throat space and the mouth space as it comes out to pay attention to the differences between different sounds.

Gretchen: If you’re taking a physics diagram or a diagram of the acoustic signal and saying, “Which pitches are coming out of the mouth, which frequencies are coming out of the mouth that are being produced by these two chambers?” then you can see what those are, and you can do stuff with those diagrams once you’ve made them.

Lauren: The seeing bit is spectrograms, which we looked at in an earlier episode and played around with making different sounds and how they look in this way of visualising it where you have all these bands of strength and information that you can see vary depending on the different sounds that you made. That’s because of those different ways that we manipulate and play around with the air as its coming out of our mouth.

Gretchen: The first band that comes out is just the pitch of the voice itself. The lowest one is what we hear as the pitch of the sound, but I can make /aaaa/ and I can make /iiii/. Those are the same set of pitches but on different vowels.

Lauren: There’s something more than pitch happening there.

Gretchen: There’s something more than pitch happening. There’s two more notes – sounds – that come out at the same time. If the throat chamber is large because the tongue is fairly high and far forward, then this sound that’s the next one after the pitch, which was call “F1,” is low. Then if the mouth is quite open, and the lips are spread, the mouth chamber is quite small, so that sound is quite high, so the next sound, “F2,” is high pitched. If you put your tongue far forward, and your lips spread, you get /i/. The first of these dark bands is low; the second of them is high. That produces the sound that we hear as /i/. Whereas, by comparison, if we make the sound /u/, the throat chamber is still large because the tongue is quite high, but now, the mouth chamber is big because we have the lips rounding that make it big – /u/. Now, F1 is low, and F2 is also low, and we’re hearing the sound /u/.

Lauren: We have a very clear way of telling from those signals in the spectrogram, if we look at it, the difference between an /i/ and an /u/, even if we can’t hear it, we can see it on the spectrogram. This is where you begin to read spectrograms.

Gretchen: Or if we want to start measuring spectrograms very precisely, we can start doing this. We can also start seeing, okay, is /i/ when I make it the same as the /i/ when you make it?

Lauren: They’re similar enough that we recognise it as the same sound. If we both say, “fleece.”

Gretchen: “Fleece.”

Lauren: You say, /flis/. I say, /flis/.

Gretchen: /pətɛɪtoʊ pətatoʊ/. I think they sound pretty similar.

Lauren: Mine is maybe a little bit higher. I really pushed my tongue forward and up. It’s a very Australian thing to do.

Gretchen: We can actually record some people making all of the vowels and compare their measurements for these two different bands of frequency and see how similar two people’s vowels are to each other.

Lauren: Depending on the quality of your recording, you can see a lot more happening there as well. There’re all the properties that mean that we can tell your voice from my voice, or my voice from someone who has exactly the same accent because we have all these other features. It’s very different to if you record, say, a whistle or one of those tuning forks that people use to tune instruments because they are giving a clean single note.

Gretchen: A pure tone that’s just one frequency, one pitch, not several pitches all at the same time that we then have to smoosh together and interpret as a vowel sound.

Lauren: That’s what gives the human voice its richness. If a human voice sings the same note as a clarinet and an oboe, which are definitely two completely different woodwind instruments, there’s all these extra bits and things in the spectrogram that you can pick up the difference in the quality or just use your ears – also another possibility.

Gretchen: Yeah. If you wanna do detailed acoustic analysis on it – which is kind of fun and can tell us more precise things about the differences between how different people speak, which is neat – then you have this very precise way of measuring it by converting it into a visual graph/chart thing or a vowel plot rather than just listening to someone and being like, “Uh, these sound pretty similar. I dunno. I guess they’re a bit different. How are they different? Hmm.” Sometimes, being able to do it with numbers is easier.

Lauren: In the era before we had computers to create spectrograms and take these measurements, people did use their ear. The best phoneticians had this amazing ability to tell the difference between really, really subtly-similar-but-slightly-different sounds.

Gretchen: And they’re so well trained in being able to hear the difference between “Oh, you’re saying this, and your tongue is a little bit further forward than this other person who’s saying this with their tongue a little bit further back,” but if you’re not very good at hearing tongue position out of sounds, you can also produce some stuff and make the machines tell you some numbers about it, which can be easier with a different type of training.

Lauren: When we talk about the position of the tongue and how open the mouth is, we can use a plot to map where in the mouth these things are happening. That’s called the “vowel space.” We made a lot of silly sounds when we talked about that many episodes ago.

Gretchen: The vowel space goes from /i-ɛ-a/ on one side.

Lauren: That’s all up the front of your mouth, and it’s just going from being more close to more open.

Gretchen: /i/ to /ɛ/ to /a/, but you can through all these subtle gradations between them, and through /u-ɔ-ɑ/ at the back.

Lauren: That’s from all the way up the top at the back to open at the back.

Gretchen: You can draw a diagram of this which is shaped like square that’s been a bit skewed. It’s wider at the top than at the bottom. It’s known as the “vowel trapezoid” because the mouth is not perfectly shaped like a square. The jaw can hinge open.

Lauren: Only so far.

Gretchen: Only so far.

Lauren: Because this represents how you say or articulate these sounds, this is known as “articulatory phonetics.”

Gretchen: But then because you’re articulating a thing that goes into a sound that we can also analyse as the sound itself, these ways that you can articulate things map onto things that show up in the sound itself. Analysing that is called “acoustic phonetics.”

Lauren: Because you’re paying attention to the acoustic properties – the sound properties.

Gretchen: The really nifty thing is that this vowel chart that we’ve made from over 100 years ago, linguists, before they had computers, were like, “Here’s what I think the articulatory properties of the vowels are based on my mouth and my ear and some other people’s mouths and ears.” You can actually map very precisely this acoustic thing. Once we had computers, you can make them correspond to each other in this way that – you hope it works because, obviously, people do understand the vowels, but it actually does work when you start measuring things as well.

Lauren: I had always wondered whether it was just a coincidence that the articulation – where you put your mouth – and the acoustic information about the F1 and F2 with the spectrogram, but explaining it in terms of F1 and F2 are the way you change the shape of your throat and your mouth that leads to these changes in the acoustic signal, you can see how the articulation and the acoustics come together, and you get a similar type of information across both of them.

Gretchen: Absolutely. I think it’s really neat that there’s this relatively straightforward correspondence. There’s also, you know, an F3 that also does other stuff because there’s other more squishy bits of your mouth, and we’re not getting into them.

Lauren: There’s also a bunch of flip-flopping of X- and Y-axes that you need to do that Bethany kindly walked us through in the bonus episode.

Gretchen: Because these diagrams were created in an era before they were doing the computer acoustics. Sometimes, I think about the alternate version of what phonetics would look like if we’d started doing it with computers right away, and how there’s all this analogue stuff that’s residual based on human impressions, and how our vowel charts might be completely rotated if we had just started doing it with computers the whole time.

Lauren: But then we’d have to imagine ourselves standing on our heads to say anything, so I’m glad they are the way they are.

Gretchen: That’s true. When you’re talking about vowels, it’s an interesting challenge with English because there’s lots of different dialects of English, varieties of English, ways of speaking English, and, generally speaking, we’re pretty good at understanding other accents. One of the big factors that accents vary on, though, is the vowels.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: If you’re getting people to record a word list to do some vowel analysis on, what you might wanna do is have them record a bunch of words that all begin and end with the same consonant insofar as possible.

Lauren: Because vowels are very sweet and easily influenced. They’re very easily influenced by the consonants that are next to them. You have to make sure that they’re all kept in line and not influenced by what’s happening around them by giving them all the same context.

Gretchen: They’re very susceptible to peer pressure. You can have people say something like, “beat,” “bet,” “bit,” “bought,” “boot,” all of this stuff between B and T.

Lauren: I learnt to record between H and D: “hid,” “had,” “hoo’d,” “hawed.” Some of those words are less, uh, common – frequent – than others, but again, a really consistent environment.

Gretchen: But this also, obviously, causes problems for when you want to talk about the particular vowels in a given accent or in a given variety because if you go around saying, “Oh, well, the /hoɪd/ vowel” or something like this, how do you know if that’s a Cockney person saying, “hide,” or it’s me saying “hoyed,” or something else because all your consonants are the exact same, and there’s nothing to let you figure out what the original word is.

Lauren: Someone did come up with a solution for this. That person’s name is John Wells.

Gretchen: John Wells is this British phonetician who I’ve never actually met in person, but I feel like I know him because I used to read his blog back when he posted more actively.

Lauren: He used to write his blog in the International Phonetic Alphabet, which means that if you read the IPA, you would be reading it in John Wells’s voice.

Gretchen: You absolutely would be. This was a challenge that I used to set to myself. Sometimes, he also wrote in Standard English orthography, to be fair, but sometimes he would just write a whole blog post in IPA, and you’d be like, “Cool, I guess I’m reading this out loud to myself and hearing John Wells’s accent and speaking it like him,” which was really neat. In the 1980s, John Wells was like, “Hey, it’d be really useful if we had a way to refer to sound changes that happen in different English varieties,” which often happen to – like, all of the times you say the /ɪ/ vowel are a little bit more like this or like that, depending on the accent.

Lauren: I think it was very personally motivated because he was writing a book called “Accents in English.” It gets very difficult in a book, especially, but even in an audio recording, to be like, “the /ɪ/ vowel,” “the /u/ vowel.”

Gretchen: Right. You could use the International Phonetic Alphabet to refer to the specific vowel that people are making. But if you want to say, “People in this area realise this vowel as that, and people in this other area realise the same vowel as something else,” how do you refer to that thing that’s the macro-category of vowel that people would consider themselves to be saying the same word, but the specific way they’re realising it is different? He came up with what he called “the standard lexical sets,” which are now also called, “Wells Lexical Sets,” possibly John Wells’s greatest legacy, which is a bunch of words that are, crucially, easy to distinguish from each other based on the surrounding consonants that you can say when you’re giving a talk – like you can say, “the ‘kit’ vowel,” or “the ‘goose’ vowel,” or “the ‘fleece’ vowel,” and people know that the “kit” vowel refers to the specific sound because there’s no other “keet” word in English that it could be confused with.

Lauren: John Wells was somewhat self-deprecating when he was talking about this, and he was like, “I just kind of came up with it in a week where I had to write this bit of the book, and it’s weird to think that they’re still in use now,” but it was based on years of insight into the different ways different varieties of English realise different vowels and the balance he was trying to strike.

Gretchen: He has this charming blog post from 2010 where he’s like, “Anybody’s welcome to use them. I don’t claim any copyright. Maybe this is my legacy now, I guess.” He does actually put quite a bit of thought into the sets because they’re words that can’t be easily confused for each other. Sometimes, that means the words are a little bit rare. You have “fleece.” You might think, “Well, why not use ‘sheep’ because surely that’s more common. People say that.”

Lauren: But “ship” and “sheep” are very hard to distinguish in some varieties of English.

Gretchen: Right. If you had “sheep,” it could be confused with “ship,” whereas if you have “fleece” and “kit,” there’s no “flice” or “keet” for them to be confused with.

Lauren: Good nonce words to add to your collection.

Gretchen: Thank you. Similarly, for people like me where I make the vowels in “caught,” as in the past tense of “catch,” and “cot,” as in a small bed, the same. If I talk about /cɑt/ and /cɑt/, people are like, “I dunno which one you’re talking about because you say them both the same.” And I’m like, “Great, neither do I.”

Lauren: You mean when you’re talking about /cɑt/ and /cɔt/.

Gretchen: Hmm. Yes, see, you don’t have that “caught/cot merger.”

Lauren: Very easy for me, but it’s much easier to be able to say /θɔt/ and /lɑt/ – much more distinct for me to perceive with you because they don’t have merged equivalents.

Gretchen: “Thought” and “lot” are much more distinct because the consonants are different. You don’t need to be relying only on the vowels. Some of these words are just super fun. Can we read the whole Wells Lexical Sets? There’re not very many of them.

Lauren: Sure. Let’s take turns in going through each of the words.

Gretchen: All right.

Lauren: So, you can hear the differences in the way we pronounce each of these vowels.

Gretchen: /kit/.

Lauren: /kit/.

Gretchen: / dɹɛs/.

Lauren: / dɹɛs/.

Gretchen: / tɹæp/.

Lauren: /tɹæp/.

Gretchen: /lɑt/.

Lauren: /lɑt/.

Gretchen: /stɹʌt/.

Lauren: /stɹʌt/.

Gretchen: /fʊt/.

Lauren: /fʊt/.

Gretchen: /bæθ/.

Lauren: /bɑθ/.

Gretchen: Ooo, very different.

Lauren: We’ll come back to that one.

Gretchen: /klɑθ/.

Lauren: /klɑθ/.

Gretchen: /nɛɹs/.

Lauren: My Australian English speaker in me is already immediately prepared for /nɛːs/.

Gretchen: So, non-rhotic. Very good.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: /flis/.

Lauren: /flis/.

Gretchen: /fɛɪs/.

Lauren: /fɛɪs/.

Gretchen: /pɑm/.

Lauren: /pæm/.

Gretchen: Ooo, very different. /θɑt/.

Lauren: /θɔt/.

Gretchen: Also, very different. We’ll come back to this. /goʊt/.

Lauren: /gəut/.

Gretchen: Bit different. /gus/.

Lauren: /gus/.

Gretchen: /pɹəɪs/.

Lauren: /pɹæɪs/.

Gretchen: Bit different. I have Canadian raising there. We’ll get back to that. /t͡ʃoɪs/.

Lauren: /t͡ʃoɪs/.

Gretchen: /moʊθ/.

Lauren: /mæʊθ/.

Gretchen: Also, we’ll get back to that. /niɹ/.

Lauren: /nɪɑ/.

Gretchen: /skwɛɹ/.

Lauren: /skwɛɑ/.

Gretchen: /stɑɹt/.

Lauren: /stɑːt/.

Gretchen: /nɔɹθ/.

Lauren: /nɔːθ/.

Gretchen: /fɔɹs/.

Lauren: /fɔːs/.

Gretchen: /kjʊɹ/.

Lauren: /kjʊɑ/. I’m only slightly hamming up my Australian English diphthongs there.

Gretchen: That whole set with the Rs where I’m like, “These are just the same sounds, but now there’s an R,” you’re like, “No, these are really different diphthongs.”

Lauren: /kjʊɑ/.

Gretchen: /kjʊɑ/. /kjʊɹ/.

Lauren: Taking you on a journey of my whole mouth.

Gretchen: One thing you could do if you’re trying to compare mine and Lauren’s vowels is you could listen to us saying them and being like, “Yeah, those sound kind of different in some places.” But another thing we could do, is we could draw some diagrams.

Lauren: That’s what we did.

Gretchen: Yes!

Lauren: We were very grateful that Dr. Bethany Gardner – who is a recent PhD in psychology and language processing at Vanderbilt University in Nashville in the USA – took the time to work with us to take recordings of us saying words and plotting the vowels onto a vowel plot.

Gretchen: Now, we can look at our vowel plots and compare our vowels to each other. We have a whole bonus episode with Bethany about how we made these graphs with them. For the moment, let’s just look at them and compare them with each other and say some things about the results.

Lauren: We sent Bethany recordings of us reading the Wells Lexical Sets, much the way we did just then.

Gretchen: Less giggling though.

Lauren: We did record them a little bit more professionally, but they also used some processes to scrape data of equivalent word recordings from episodes of Lingthusiasm using our transcripts – turns out, another use of our transcripts!

Gretchen: Get people to analyse your vowels for you. It’s so cool!

Lauren: You can see the difference between clearly spoken vowels where we’re really focusing on them and then that really compelling influence that other sounds have on vowels that drag them all over the space.

Gretchen: Yeah. I’m looking at the first set of graphs for each of us, which are the Wells Lexical Sets, and my vowels are a lot more consistent in them. When I make /i/ and /ɪ/ and /u/, all the points are quite clustered in one spot – because we said everything several times – but I seem to be hitting quite a consistent target there. Whereas when I look at Bethany’s vowel plot of me from the Lingthusiasm episodes, there’s way more stuff there, and I’m way more spread out. My vowels are less consistent with each other because I’m producing them in several words. They tested several different words. I’m just producing them in running speech where things merge into each other a lot more rather than this very clear word list style.

Lauren: And human ears and brains are so good at disambiguating things that might be very close to each other in the plot, but in a running sentence, we can hear them quite clearly for the words that they are.

Gretchen: Right. My “goose” vowel and my “foot” vowel – /gus/ and /fʊt/ – are almost totally distinct from each other when I’m reading a word list. There’s very little overlap in terms of how I’m saying them. But when I’m saying them in running speech, apparently there’s a lot of overlap because I’m probably saying something like, “Oh, go get the goose,” /gʊs/, rather than /gus/ with that really clear /u/.

Lauren: There’s no other word I’m gonna confuse “goose” with, or even if I did, in context, I’d know what thing you’re expecting me to go get.

Gretchen: Right. Even if I’m saying something like, “dude,” you’re not gonna confuse that for “dud.” I’d be saying them in different contexts.

Lauren: The nice thing is you can see, especially from our clearly spoken word lists, that we are speaking a language where the vowels are in a similar place, but there are some slight differences. You can actually start to get the hang of the differences in the way different varieties of English tend to use the vowel space from this information.

Gretchen: One of the things I noticed about your vowel plot, Lauren – and this is a feature of Australian English – is that your “kit” vowel and your “fleece” vowel are very close to each other, especially in episode speech rather than word list speech.

Lauren: Yeah, “kit” and “fleece,” for me, are both really far forward. You’re using other features like length or tenseness to really disambiguate them. People struggle to do it.

Gretchen: Or just in context. I noticed when I was visiting Australia that people would say things like /bɪːg/, and I’d be like, “Oh, okay, I would say that as /bɪg/.”

Lauren: It’s a pretty classic feature of Australian English. It does remind me of one of the most embarrassing times someone misheard me when I was living in the UK. I was talking about how I used to be on a team with my friends for social netball. This person was not listening that well, and it was a noisy environment, and they thought that I had said, “nipple.”

Gretchen: Oh, no!

Lauren: /nɪpl̩/ and /nɛtbɑl/.

Gretchen: /nɛtbɑl/, /nɛtbɑl/, whereas I think my /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ vowels, my “kit” and “dress” vowels, are pretty distinct from each other. They don’t really overlap.

Lauren: Whereas all of Australian English is really far forward. It tends to be quite high. The British English speaker – I don’t know what sport they thought we play in Australia, but there was a moment of deep confusion.

Gretchen: These are the types of things that you can find out when you get your vowels done the way sometimes people – I think there’s a trend on Instagram right now to get your colours done, you know, find out whether you’re a “winter” or a “soft spring” or something like this.

Lauren: I’m an Australian English “kit”-fronting.

Gretchen: Yeah. What are your vowels? What does this say about where you’re from? Is there anything you noticed about mine?

Lauren: I think, for you, definitely what becomes clear is that “caught/cot merger,” or, as I like to think about it, the “Gawne/gone merger.”

Gretchen: Ah, the “Gawne/gone merger.”

Lauren: I can tell if people have it if my name and the word “gone” sound the same.

Gretchen: The past participle of “go.”

Lauren: It’s very salient for me. The cot/caught merger is so famous, people don’t use the Wells Set terms for it. They just refer to it as “caught/cot.”

Gretchen: But you could also call it the “thought/lot merger” or the “lot/thought merger.” I never know which one goes first because I literally just think of these as being said the same.

Lauren: You can see evidence. We’re not imagining that you’re merging them. You are physically merging them in the vowel space.

Gretchen: I’m literally saying them as the same thing. I was always confused about the “thought” vowel when I was learning the International Phonetic Alphabet because I was like, “I can’t figure out how to make a sound that is somewhere in between this sound in ‘lot’ and ‘thought’ but doesn’t go all the way up to the /oʊ/ in ‘goat’.” It doesn’t feel like there’s anything between them for me. That’s true. The vast majority of Canadians have “thought” and “lot” merged. But unlike at least some Americans, we don’t have them merged low; we have them merged high. I have “thought” and “caught,” and in order to produce the other vowel, I had to actually produce something lower in my throat – like /θɑt/ /cat/ which sounds very American to me – I had to produce this lower sound because there was no space between “thought” and “goat.” They’re very close to each other. In fact, the thing that I wasn’t producing was /ɑ/, the really low one, that sort of dentist sound.

Lauren: Yeah. Movements and mergers can happen in all kinds of different directions. The merging of “cot” and “caught” also explains why it took me a very long time to understand that “podcast” is a pun because it’s meant to be a pun with “broadcast,” and /pɑd/ and /bɹɔːd/.

Gretchen: /pɑdkæst/ and /bɹɑdkæst/. It’s the same vowel for me.

Lauren: Whereas it works as a pun for you. That was very satisfying to learn that’s why that’s meant to be a pun.

Gretchen: The pun that I didn’t get based on my accent – and this is to do with the “price” and “mouth” vowels – I didn’t realise that “I scream for ice cream” was supposed to be a pun.

Lauren: Oh, because the raising that you have in Canada means that it doesn’t work that way, whereas /ɑɪ skɹim fə ɑɪ skɹim/.

Gretchen: Right, you have the same vowel in those – or the same diphthong – but for me, “I scream for ice cream,” those are very different. In “choice” and “price,” I have different vowels than I would have in “choys” and “prize” – if “choys” was a word.

Lauren: “Bok choys” – multiple.

Gretchen: “Bok choys” – yeah, several of them. And “prize.”

Lauren: Returning to “podcast” but moving to the other end of the word, /kɑst // kæst/ as a distinction is so famous in mapping varieties of British English that people talk about /bɑθ // tɹæp/ distinctions all the time.

Gretchen: I hear of it as called the “bath/trap split,” but as you can hear, the “/bæθ // tɹæp/ split,” I just say them both the same.

Lauren: Whereas in Australia, Victorians traditionally would say /kæsl̩/ like “trap,” and people further north and in the rest of the country could say, /kɑsl̩/ –

Gretchen: Like “bath.”

Lauren: So, whether you’re a /kɑsl̩/ or a /kæsl̩/ shows this “bath/trap split” as well, to the point where, in New South Wales, you get the city of “New /kɑsl̩/,” but in Victoria, you have the town of “/kæsl̩/ Main.”

Gretchen: Ooo, this “castle” distinction from the “trap/bath split” – I think sometimes when I’m trying to do a fake British accent, I will just make all of my “traps” and “baths” into /tɹɑps/ and /bɑθs/.

Lauren: Right, okay. You know there’s something happening there, and you haven’t quite landed – because it does vary.

Gretchen: Well, then they’re not different categories for me because it’s all one category, and I push them all forward rather than moving half of them because I don’t know which half to move.

Lauren: I find it very satisfying listening to “No Such Thing as a Fish,” because they talk about the /pɑdkɑst/ or the /pɑdkæst/, and their guests do, depending on whether they’re from Southern England or more in the midlands and north where they tend to say /kæst/ instead of /kɑst/.

Gretchen: I have literally never noticed this distinction. I’ve also listened to many episodes of “No Such Thing as a Fish” because you made me start listening to them back in the day, and I’ve never noticed that they say anything different because it’s just not something I pay attention to.

Lauren: It’s so salient for me as a Victorian English speaker, but I notice it all the time. There would be a really fun mapping variation activity to do listening through to Fish – turns out I just listen to it and don’t get distracted by that too much.

Gretchen: Well, if you want to commission Bethany to make graphs of their vowels, I’m sure that’s an option.

Lauren: I love how Wells’ lexical set has just entered – in many ways, the “bath/trap split,” it means you get all these other terms like “goose fronting,” which is just great as a term.

Gretchen: I love how vivid these words are. Things like “fleece” and “goose” and “goat,” they’re very common animal nouns that are quite vivid.

Lauren: And there’re definitely linguists who have dressed up as Wells Lexical Set items for Halloween. It makes a great group Halloween costume.

Gretchen: Oh my gosh, my favourite one of these was from North Carolina State University. They got the whole department, and they each dressed up as one member of the Wells Lexical Set. Someone was a “kit.” They dressed like a cat. Someone dressed like a goose, and someone dressed like a cloth or a fleece. Then they stood in the positions to create the vowel diagram. They posted a photo on the internet. You can see it. We will link to it. It’s really great.

Lauren: Magic. You and I also once had a project where we plotted the Wells Lexical Set using emoji.

Gretchen: That was your project.

Lauren: I did the making the joke. You did the graphic design. It was a good team project.

Gretchen: Okay, that’s fair. That’s fair. I feel like I remember you being the instigator of this.

Lauren: Shenanigans were shenaniganed.

Gretchen: You can get a goose emoji and a goat emoji, and you can map the vowels in there as well.

Lauren: And “Goose fronting” – because we’re talking about moving the tongue further forward or back or up and down in the vowel space – I have quite fronted vowels as an Australian English speaker for my front vowels. So, “goose” – I’ve already got it quite far forward compared to you. You can see that in the diagrams.

Gretchen: I think my “goose” – my goose is also cooked – my “goose” is also fronted. Because I think Canadian English is also undergoing goose fronting. There’s a lot of different regions that are all simultaneously fronting their geese – no, not their “geese,” fronting their “gooses.”

Lauren: Fronting their “gooses.” I feel like the really stereotypical example is from California, particularly in the lexical item “dude.”

Gretchen: “Dude” – sort of like a surfer pronunciation of “duuude.”

Lauren: “/du̟d/ you’re a fronted /gu̟s/.”

Gretchen: If you compare that with like /dud/, which would be less fronted, /dud/ sounds like you’re more of a fuddy duddy, and /du̟d/ sounds like you’re “so /ku̟l/.”

Lauren: Yeah, I mean, there’re other things happening there as well because I found a paper while researching this where someone looked at 70 years of Received Pronunciation, which is that incredibly stuffy, British, old-fashioned newsreader voice. Apparently, goose fronting is happening in that variety as well.

Gretchen: Oh, so if the Queen was still alive, she’d be fronting her “goose” as well?

Lauren: Quite possibly. Gooses are being fronted all over the place.

Gretchen: All over the English-speaking world. One of the things that can happen if you’re getting your vowel tea leaves read is you can say things about region. Another thing that looking at a vowel plot can do – because vowels just contribute so much to our sense of accent – is it can say things about gender. One of the cool studies that I came across about this is there’re studies of kids. People often assess someone’s gender based on their voice. If someone’s on the phone, you may have an idea about their gender. You may also have an idea of their age. Part of this is based on vocal tract size. Kids’ voices are high pitched because kids’ heads and throats and larynxes are smaller than adults.

Lauren: The cool thing is there’s no gender difference in that until puberty. People who go through a testosterone-heavy puberty tend to grow larger vocal tracts and tend to have deeper pitches. I mean, not in the scheme of things where they’re so completely different. There’s so much overlap. But we’re really tuned into these subtle differences. But before that age, anything that kids are doing different, it’s nothing to do with what’s happening with the meat pipe and everything to do with what’s happening with the social performance of gender, which is to do with your culture.

Gretchen: Even at age 4, when there’s really no physiological difference, age 8 when there’s really no physiological difference, you can see that kids are producing their vowels somewhat differently in a difference that increases with age based on their gender because they’re culturally acquiring “This is what it means to feel like a boy,” “This is what it means to feel like a girl,” and they’re doing gender with their voices even when they don’t have the vocal tract changes reinforcing that yet.

Lauren: Cool.

Gretchen: Yeah. You can see that there are differences at age 4 that increase with age and increase up to age 8 and 12 and 16 and get more distinct from each other. The other thing is, once people get a bit older in teenage-hood and in adulthood, there are gender differences in vocal tract. The general finding with gender differences in vowel plot size – so we’ve been talking about having some vowels be more front or some vowels be more similar to each other, but the overall finding when it comes to gender is roughly that, at least in English-speaking environments, men tend to have all of their vowels more similar to each other, more towards the centre of the space/ Specifically, cis straight men tend to have vowels that are all more towards the centre of the vowel space. Everybody else – so cis, straight women, gay men, lesbians, trans people of all genders, nonbinary people – use way more of the vowel space.

Lauren: Straight men, you’re missing out.

Gretchen: Like, cis straight men are doing this one very specific thing with buying into hegemonic masculinity of vowels where they’re not wearing interesting colours, and they’re not doing interesting vowels.

Lauren: Hmm.

Gretchen: There was one quote from one of the studies that I read where they had one cis straight man who was an anomaly in the list of not doing this very centralised vowel thing, and he was like, “Yeah, sometimes people hear me, and they think I’m gay, which I’m not. I’m just a nerd. I don’t really do that macho stuff.”

Lauren: Aww, it’s nice they asked him.

Gretchen: Yeah. “People just perceive my vowels as whatever. I don’t really care. I’m not trying to do that thing with my vowels.”

Lauren: Fascinating that the social discourse was enough that he had been made aware of it.

Gretchen: Yeah, and that doing anything out of that little man box of the very small set of vowels was enough to get him thinking, “Oh, yeah, well, it’s because I don’t buy into this particularly narrow view of masculinity.”

Lauren: Fascinating. I should say, you flagged English there, but that’s because we have more of this work in English. We need more of this work across the world’s languages. There’s so much to be done about the social dimensions of vowels.

Gretchen: Right. A lot of the early work in, especially, gender and vowels has this very essentialist framework of like, “We found the male vocal tract; we found the female vocal tract.” There’s a recent study by Santiago Barreda and Michael Stuart which I got to see at the Linguistic Society of America last year where they were looking at “What are the vowel differences between genders, and can we actually characterise these more precisely?” They found that the biggest thing that affected vowel spaces was actually related to height. Taller people have more space in their vowels – deeper voices.

Lauren: Makes sense. They’ve got more space for their bigger meat pipe. That’s more of a bassoon than an oboe, Gretchen.

Gretchen: Taller people have a bigger meat pipe. In fact, the relationship between height of your whole body and size of your meat pipe is very linear and doesn’t have a categorical distinction for gender. Of course, if you collapse this into two different buckets labelled “men” and “women,” you’ll find, on average, that men are taller than women on average, but of course, there’re lots of individual people who are exceptions to that, and it’s much more of a variant thing. Similarly, with some of the research on sexuality, some of the early stuff is like, “Oh, do gay men or do lesbians have different-shaped vowel tracts from a physiological perspective?” The answer is “No, this is cultural.”

Lauren: Right, yeah.

Gretchen: But the finding keeps being reported in terms of like, “Oh, well, gay men have more extreme vowels in various places,” especially with “trap” being produced further away from the centre of the mouth. Lesbian women tend to have further-back sounds for “palm” and for “goose,” or sometimes they’re intermediate between male and female targets. But again, this seems to very much be cultural. The bi women – some studies found they patterned with the lesbian women. Some studies found they pattern with the straight women. No one knows what to do with us. The one study I found on bi men found they patterned with the gay men, but again, maybe other studies would find something different. There’s a paper by Lal Zimman about trans men’s voices being perceived as quote-unquote “gay” after they go on testosterone. He finds that it’s not quite the exact same as the cis gay men, but it’s also because it seems to not be in that narrow man box. People are just parsing it as gay.

Lauren: So many cultural attitudes coming to bear on vowel spaces.

Gretchen: Studies on trans women’s vowel spaces is often fairly dominated by the speech pathology literature, which is about, specifically, vocal training and trans women really trying to make their voices sound different, but it still finds that they’re not doing exactly the same thing as either cis women or cis men.

Lauren: Right. Again, lots of cultural practice at play there. Anything about our nonbinary pals?

Gretchen: There is a recent dissertation by Jacq Jones, and they find that basically nonbinary people do whatever the heck they like.

Lauren: I love it.

Gretchen: Which is, again, not exactly the same as anybody else and not necessarily the same as each other either. They could just keep doing whatever they want. But yeah, there’s a lot of stuff on gender and sexuality, especially in terms of dispersion of the vowel space and regional stuff in terms of specific things being closer or further from each other.

Lauren: There’s so much happening in vowels in terms of plotting them all in this space in the mouth, but also so much happening in terms of plotting them in the social space. This is what makes vowels so rich and so interesting.

Gretchen: I feel like when we’re talking about vowel plotting, there’s this aspect of “Mwahaha, I am putting my fingers together and plotting,” which is maybe the fact that vowels do convey so much social information about who you are or where you’re from that you can make plots about people when you know what their vowels are. If we were going to make a meat clarinet or a meat bassoon or even a meat bagpipe –

Lauren: Oh, dear.

Gretchen: I’m so sorry. We would not only want it to be able to convey the basic vowel chart. One of the reasons why I think these synthetic versions of the human voice often sound so weird is that they don’t have all of this additional demographic information, regional information, gender and sexuality information that’s also so important to our experience of vowels.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode – including visualisations of our very own vowel plots – go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on all the podcast platforms or lingthusiasm.com. You can get transcripts of every episode on lingthusiasm.com/transcripts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on all the social media sites. You can get scarves with lots of linguistics patterns on them including the IPA, branching tree diagrams, bouba and kiki, and our favourite esoteric Unicode symbols, plus other Lingthusiasm merch – like “Etymology isn’t Destiny” t-shirts and aesthetic IPA posters – at lingthusiasm.com/merch. Links to my social media can be found at gretchenmcculloch.com. My blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com. My book about internet language is called Because Internet.

Lauren: My social media and blog is Superlinguo. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you want to get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Our most recent bonus topic was a chat with Dr. Bethany Gardner, who built the vowel plots we discussed in this episode. We talked to Bethany about how to do vowel charts and how you can plot your own vowels, or you can just learn about how they did it for us. Think of it like a little behind-the-scenes episode on the making of this episode. If you can’t afford to pledge, that’s okay, too. We really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Gretchen: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Lauren: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#linguistics#language#lingthusiasm#podcast#transcripts#podcasts#episodes#episode 90#vowels#vowel sounds#vowel plots#vowel charts#IPA#international phonetic alphabet#phonetics#accents

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

a super serious question posed to to pathologic tumblr: if Bachelor Daniil Dankovsky spoke english, how would he pronounce the word research?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating a HRT milestone by analysing which symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet I would like to fuck

#linguistics#milestone#language#langblr#language blog#languageblr#language meme#language memes#linguistics humor#language learning#english#tiktok#smash or pass#phonetics#international phonetic alphabet#ipa#video#comedy#trans#trans rights#transgender#transmasc#ftm#ftm hrt#hrt

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

if twink x twunk and thing x thong, then

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

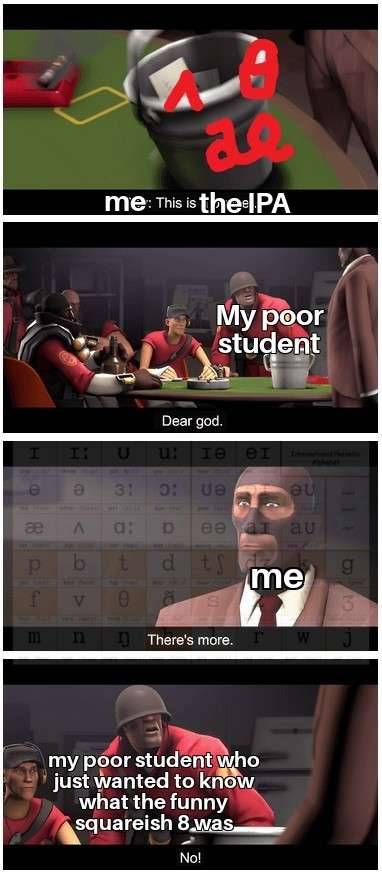

One of the people I teach English made the mistake of asking me (an English major) about the phonetic transcript that was next to their vocabulary list, and I went off on a tangent

#phonetics#international phonetic alphabet#tf2#meme#the tism is strong with this one boys. I am both fascinated and infuriated by phonetics

13 notes

·

View notes