Photo

240406_123846_a.clj

https://tweegeemee.com/i/240406_123846_a

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

wendy carlos, taken by robert moog

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Wow Signal

The ‘Wow! signal’ was received at 11.16pm on August 15, 1977 - the night before Elvis died — as a radio telescope in Ohio swept its gaze through the constellation of Sagittarius.—

It lasted 72 seconds and was earned its name because of the message of disbelief Jerry Ehman, a researcher with the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) programme, scrawled next to the printout recording it.

The characteristics of the signal - a rise and fall in its ‘loudness’ were exactly what the alien-hunters had been told to look out for.

The signal had the trademark of an artificially produced interstellar broadcast.

How did they broadcast it from a point in space where there are no planets and there are no solar systems? Well, the only explanation would be a spaceship, and the signal is used to communicate to other spaceships.

6K notes

·

View notes

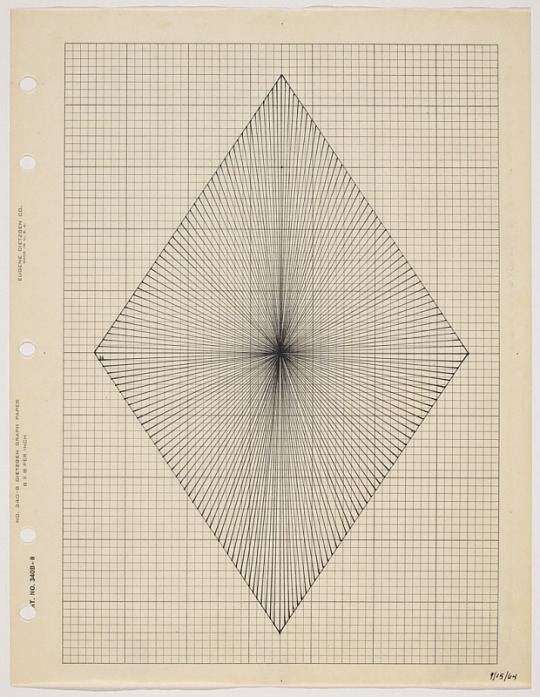

Photo

Lenore Tawney, Untitled, 1964

Ink on graph paper

© Lenore G. Tawney Foundation

379 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Morning Good Night, Sachiko M / Toshimaru Nakamura / Otomo Yoshihide (2004)

No wonder Good Morning Good Night angers so many – music rarely tests the recorded form like this. Sachiko M, Nakamura and Yoshihide work their strains of experimentalism into the sounds of the everyday, intermingling life with digital buzz and vice versa. One’s experience is totally dictated by circumstance; so life shifts, as one never lives the same sounds twice, so no two listens of Good Morning Good Night are alike.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Michael Heizer, Double Negative, 1969

(Moapa Valley, NV)

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Otto Piene, Nachtsonne (The Moon Upon Which It Depends), 1964-1965

Fire painting on canvas, 150 x 200 cm.

445 notes

·

View notes

Photo

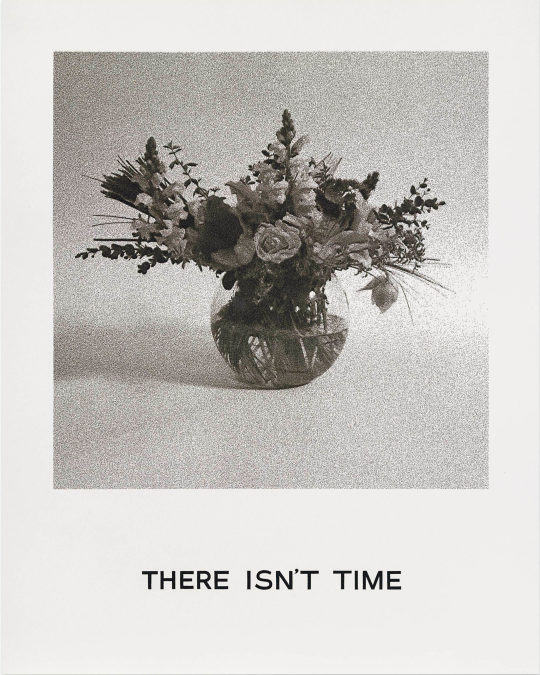

John Baldessari

There isn’t Time

Goya Series, 1997

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Love Hertz

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

minimalistic

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

02.02.24 Tribute to legendary NYC composer Phill Niblock at Hunter College in NYC, organized by Hans Tammen. With Lucie Vitkova, Marcia Bassett, Teerapat Parmongkol, Alex Zhu, Luke Dubois, Emad Jamal, Monica Rocha, Shoko Nagai, Crystal Penalosa, Chuck Bettis, Kamran Sadeghi, Michael Schumacher, David Galbraith, Daniel Neumann, David First, Abby Davis, David Rothenberg, Daniel Neumann, Ben Manley, Miguel Frasconi, Andrew Neumann, Laura Feathers & Hans Tammen. Visuals by Katherine Liberovskaya.

#phill niblock#hans tammen#katherine liberovskaya#experimental music#composer#performance#concert#tribute#nyc#electronic music#drone music

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

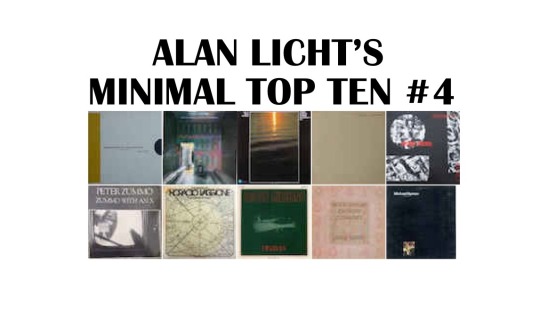

Alan Licht’s Minimal Top Ten List #4

A few weeks ago, near the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, my friend Mats Gustafsson sent out a mass email encouraging people to send him record lists to post on the “Discaholics” section of his website–top tens, favorite covers, anything. I immediately thought of the first 3 Minimal Top Ten lists I did (now found online here) back in 1995, 1997, and 2007 respectively, for the fanzine Halana (the first two) and Volcanic Tongue’s website (the third), and sent them to him. Those articles have sort of taken on a life of their own, and I still see them referenced as the albums get reissued and so on. Occasionally people ask me if I’d ever do another one, and looking at all three again made me think now is the hour. I started writing this in the midst of the lockdown, and the drastic reductions in people’s way of life—the restriction of any activity outside the home to the bare essentials, the relative stasis of life in quarantine, even the visual stasis of a Zoom meeting—make revisiting Minimal music, with its aesthetic of working within limitations and hallmarks of repetition and drones, somehow timely as well.

The original lists were never meant to represent “the best” Minimal albums: they were ones that were rare and in some cases surpass, in my opinion, more widely available releases by the same artist and/or better known examples of the genre. Some were records that hadn’t been classified as Minimalist but warranted consideration through that lens. Likewise, the lists aren’t meant to be ranked within themselves, or in comparison to each other; the first record on any of the lists isn’t necessarily vastly preferable to the last, and this fourth list is not the bottom of the barrel, by any stretch. In some cases the present list has records I’ve discovered since 2007; others are records I’ve known for quite a while but haven’t included before for one reason or another. I’ve also made an addendum to selected entries on the first three lists, which have become fairly dated in terms of what is currently available by many of the artists, and to account for some of the significant archival releases in the 25 years since I first compiled them.

Unlike the mid-90s, most if not all of these records can be heard and/or purchased online, whether they’re up on YouTube or available for sale on Discogs. So finding them will be easier than before (although I haven’t included links to any of the titles as a small tribute to the legwork involved in tracking records down in olden tymes), but hopefully the spirit of sharing knowledge and passions that drove my previous efforts, forged in the pre-internet fanzine world, hasn’t been rendered totally redundant by the 24/7 onslaught of virtual note-comparing in social media.

1. Simeon ten Holt Canto Ostinato (various recordings): This was the most significant discovery for me in the last decade, a piece with over one hundred modules to be played on any instrument but mostly realized over the years with two to four pianos. I first encountered a YouTube live video of four pianists tackling it over the course of 90 minutes or so, then bought a double CD on Brilliant Classics from 2005, also for four pianos, that runs about 2 and half hours. The original 3LP recording on Donemus, from 1984, lasts close to 3 hours. It’s addictively listenable, very hypnotic in that pulsed, Steve Reich “Piano Phase”/”Six Pianos” kind of way, with lots of recurring themes (which differentiates it from Terry Riley’s “In C,” its most obvious structural antecedent). Composed over the span of the 70s, as with Roberto Cacciapaglia’s Sei Note in Logica, it’s an example of someone contemporaneously taking the ball from Reich or Riley and running with it. Every recording I’ve heard has been enjoyable, I’ve yet to pick a favorite.

2. David Borden Music for Amplified Keyboard Instruments (Red Music, 1981)

3. Mother Mallard’s Portable Masterpiece Co. Like a Duck to Water (Earthquack, 1976): These were some of my most cherished Minimal recordings when I was a teenager in the mid-80s, and are still not particularly well-known; they’re probably the biggest omission in the previous lists (at least from my perspective). Borden formed Mother Mallard, supposedly the first all-synthesizer ensemble, as a trio in the late 60s, although there’s electric piano on the records too. He went on to do music under his own name that hinged on the multi-keyboard Minimalism-meets-Renaissance classical concept he first explored with Mother Mallard, as exemplified by his 12-part series “The Continuing Story of Counterpoint” (a title inspired by both Philip Glass’ “Music in Twelve Parts” and the Beatles’ “The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill”). I first heard Parts 6 & 9 of “Continuing Story” (from Music for Amplified Keyboard Instruments) on Tim Page’s 1980s afternoon radio show on WNYC, and bought the Mother Mallard LPs (Like A Duck is the second, the first is self-titled) from New Music Distribution Service soon after. I mail-ordered the Borden album from Wayside Music, which had cut-out copies, maybe a year later (c. 1986). I wasn’t much of a synth guy, but I loved the propulsive, rapid-fire counterpoint and fast-changing, lyrical melodies found on these records. “C-A-G-E Part 2,” which occupies side 2 of the Mother Mallard album and utilizes only those pitches, has to be a pinnacle of the Minimal genre. Interestingly, Borden claims to not really be able to “hear” harmony and composes each part of these (generally) three-part inventions individually, all the way through. The two-piano “Continuing Story of Counterpoint Part Two” on the 1985 album Anatidae is also beloved by me, and there was an archival Mother Mallard CD called Music by David Borden (Arbiter, 2003) that’s worth hearing.

4. Charles Curtis/Charles Curtis Trio: Ultra White Violet Light/Sleep (Beau Rivage, 1997): Full disclosure: Charles is a long-time friend, but this record seems forgotten and deserves another look, especially in light of the long-overdue 3CD survey of his performances of other composers’ material that Saltern released last year. This was a double album of four side-long tracks, conceived with the intent that two sides could be played simultaneously, in several different configurations; two of them are Charles solo on cello and sine tones, the others are with a trio and have spoken vocals and rock instrumentation, with cello and the sine tones also thrown into the mix. (I’ve never heard any of the sides combined, although now it would probably be easily achieved with digital mixing software.) The instrumental stuff is the closest you can come to hearing Charles’ beautiful arrangement of Terry Jennings’ legendary “Piece for Cello and Saxophone,” at least until his own recording of it sees the light of day; the same deeply felt cello playing against a sine tone drone. And it would be interesting to see what Slint fans thought of the trio material. Originally packaged in a nifty all-white uni-pak sleeve with a photo print pasted into the gatefold, it was reissued with a different cover on the now-defunct Squealer label on LP and CD but has disappeared since then. Stellar.

5. Arthur Russell Instrumentals 1974 Vol. 2 (Another Side/Crepuscule, 1984)

6. Peter Zummo Zummo with an X (Loris, 1985): Arthur Russell has posthumously developed a somewhat surprising indie rock audience, mostly for his unique songs and singing as well as his outré disco tracks. But he was also a modern classical composer, with serious Minimal cred—he’s on Jon Gibson’s Songs & Melodies 1973-1977 (see addendum), and played with Henry Flynt and Christer Hennix at one point; his indelible album of vocal and cello sparseness, World of Echo, was partially recorded at Phill Niblock’s loft and of course his Tower of Meaning LP was released on Glass’s Chatham Square label. He’s the one guy in the 70s and 80s (or after, for that matter) who connected the dots between Ali Akbar Khan, the Modern Lovers, Minimalism, and disco as different forms of trance music (taken together, both sides of his disco 12” “In the Light of the Miracle,” which total nearly a half-hour, could arguably be considered one of his Minimalist compositions). Recorded in 1977 & 1978, Instrumentals is an important signpost of the incipient Pop Minimalism impulse, and the first track is a pre-punk precursor to Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca’s appropriations of the rock band format to pursue Minimal pathways (Chatham is one of the performers in that first piece). The rest, culled from a concert at the Kitchen, features long held tones from horns and strings and is quite graceful, if slightly undercut by Arthur’s own slightly jarring, apparently random edits. [Audika’s 2006 reissue, as part of the double CD First Thought Best Thought, includes a 1975 concert that was slated to be Instrumentals Vol. 1, which shows an even more specific pop/rock/Minimal intersection]. Zummo was a long-term collaborator of Russell’s and his album, which Arthur plays on, is a must for Russell aficionados. The first side is made up of short, plain pieces that repeat various simple intervals and are fairly hard-core Minimalism, but “Song IV,” which occupies all of side two, is like an extended, jammy take on Russell’s disco 12” “Treehouse” and has Bill Ruyle on bongos, who also played on Instrumentals as well as with Steve Reich and Jon Gibson. A recently unearthed concert at Roulette from 1985 is a further, and especially intriguing, example of Russell’s blending of Minimalism and song form. (That same year Arthur played on Elodie Lauten’s The Death of Don Juan–another record I first encountered via Tim Page’s radio show–which I included on Top Ten #3; Lauten as well as Zummo played on the Russell Roulette concert, as their website alleges).

7. Horacio Vaggione La Maquina de Cantar (Cramps, 1978): Another one-off from the late 70s, and yet more evidence of how Minimalism had really caught on as a trend among European composers of the time. Vaggione had a previous duo album with Eduardo Polonio under the name It called Viaje that was noisier electronics, and he went on to do computer music that was likewise more traditionally abstract. But on this sole effort for the Italian label Cramps, as part of their legendary Nova Musicha series, he went for full-on tonality. The title track is like the synth part of “Who Are You” extended for more than fifteen minutes and made a bit squishier; but side 2, “Ending”–already mentioned in the entry on David Rosenboom’s Brainwave Music in Top Ten #3–is my favorite. Kind of a bridge between Minimalism and prog, and a little reminiscent of David Borden’s multiple-synth counterpoint pieces, for the first ten minutes he lingers on one vaguely foreboding arpeggiated chord, then introduces a fanfare melody that repeats and builds in harmonies and countermelodies for the remainder of the piece. Great stuff, as Johnny Carson used to say.

8. Costin Miereanu Derives (Poly-Art, 1984): Miereanu is French composer coming out of musique concrete. Unlike some of the albums on these lists, both sides/pieces on Derives are superb, comprised of long drones with flurries of skittering electronic activity popping up here and there. Also notable is the presence of engineers Philip Besomes and Jean-Louis Rizet, responsible for Pôle, the great mid-70s prog double album that formed the basis of Graham Lambkin’s meta-meisterwork Amateur Doubles. I discovered this record via the old Continuo blog; Miereanu has lots of albums out, most of which I haven’t heard, but his 1975 debut Luna Cinese, another Cramps Nova Musicha item, is also estimable, although less Minimal.

9. Mikel Rouse Broken Consort Jade Tiger (Les Disques du Crepuscule, 1984): Rouse was a major New Music name in the 80s, as was Microscopic Septet saxist Philip Johnston, who plays here. Dominated by Reichian repeated fills that accentuate the odd time signatures as opposed to an underlying pulse, this will sound very familiar to anyone acquainted with Nik Bärtsch’s Ronin albums on ECM, which use the same general idea but brand it “zen funk” and cater more to the progressive jazz crowd rather than New Music fans, if we can be that anachronistic in our terminology. Jade Tiger also contrasts nicely with Wim Mertens’ more neo-Romantic contemporaneous excursions on Crepuscule. Rouse later performed the admirable (and daunting) task of cataloging Arthur Russell’s extensive tape archive for the preparation of Another Thought (Point Music, 1994)

10. Michael Nyman Decay Music (Obscure, 1976): Known for his soundtracks to Peter Greenaway films, and his still-peerless 1974 book Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond (where I, Jim O’Rourke, and doubtless many other intrepid teenage library goers learned of the Minimalists, Fluxus, AMM, and lots of other eternal avant heroes), Nyman is sometimes credited with coining the term “Minimal music” as well, in an early 70s article in The Spectator. Decay Music was produced by Brian Eno for his short-lived but wonderful Obscure label. The first side, “1-100,” was also composed for a Greenaway film, and has one hundred chords played one after another on piano, each advancing to the next once the sound has decayed from the previous chord (hence the album title). For all its delicacy and silences, you’re actually hearing three renditions superimposed on one another, which occasionally makes for some charming chordal collisions (reminiscent of the cheerfully clumsy, subversive “variations” of Pachelbel’s “Canon in D major” on Eno’s own Discreet Music, the most celebrated Obscure release). This is process music at its most fragile and incandescent. In hindsight it may have also been an unconscious influence on the structure of my piece “A New York Minute,” which lines up a month’s worth of weather reports from news radio, edited so that one day’s forecast follows its prediction from the previous day. I’ve never found the album’s other piece, “Bell Set No. 1,” to be quite as compelling, and Nyman’s other soundtrack work doesn’t hold much interest for me, but I’ve often returned to this album.

11. J Dilla Donuts (Stones Throw, 2006): One more for the road. Rightfully acclaimed as a masterpiece of instrumental hip hop, I have to confess I only discovered Donuts while reading Questlove’s 2013 book Mo’ Meta Blues, where he compared it to Terry Riley. The brevity of the tracks (31of ‘em in 44 minutes) and the lack of single-mindedness make categorizing Donuts as a Minimal album a bit of a stretch, but Questlove’s namecheck makes a whole lot of sense if you play “Don’t Cry” back to back with Riley’s proto-Plunderphonic “You’re Nogood,” and “Glazed” is the only hip hop track to ever remind me of Philip Glass. Plus the infinite-loop sequencing of the opening “Outro” and concluding “Intro” make this a statement of Eternal Music that outstrips La Monte Young and leaves any locked groove release in the proverbial dust. There isn’t the space here to really explore how extended mixes, all night disco DJ sets, etc. could be encountered in alignment with Minimalism, although I would steer the curious towards Pete Rock’s Petestrumentals (BBE, 2001), Larry Levan’s Live at the Paradise Garage (Strut, 2000), and, at the risk of being immodest, my own “The Old Victrola” from Plays Well (Crank Automotive, 2001). On a (somewhat) related note I’d also point out Rupie Edwards’ Ire Feelings Chapter and Version (Trojan, 1990) which collects 16 of the producer/performer’s 70s dub reggae tracks, all built from the exact same same rhythm track–mesmerizing, even by dub’s trippy standards.

Addendum:

Tony Conrad: “Maybe someday Tony’s blistering late 80s piece ‘Early Minimalism’ will be released, or his fabulous harmonium soundtrack to Piero Heliczer’s early 60s film The New Jerusalem.” That was the last line of my entry on Tony’s Outside the Dream Syndicate in the first Top Ten list in 1995, and sure enough, Table of the Elements issued “Early Minimalism” as a monumental CD box set in 1997 and released that soundtrack as Joan of Arc in 2006 (it’s the same film; I saw it screened c. 1990 under the name The New Jerusalem but it’s more commonly known as Joan of Arc). Tony releases proliferated in the last twenty years of his life, which was heartening to see; I’d particularly single out Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain (Superior Viaduct, 2017), which rescues a 1972 live recording of what is essentially a prototype for Outside played by Tony, Rhys Chatham, and Laurie Spiegel (Rhys has mentioned his initial disgruntlement upon hearing Outside, as it was the same piece that he had played with Tony, i.e. “Ten Years Alive,” but he found himself and Laurie replaced by Faust!) and an obscure compilation track, “DAGADAG for La Monte” (on Avanto 2006, Avanto, 2006), where he plays the pitches d, a, and g on violin, loops them over and over , and continually re-harmonizes them electronically–really one of his best pieces.

Terry Riley: The archival Riley CDs that Cortical Foundation issued in the 90s and early 00s don’t seem to be in print, but I feel they eclipse Reed Streams (reissued by Cortical as part of that series) and are crucial for fans of his early work, especially the live Poppy Nogood’s Phantom Band All Night Flight Vol. 1, an important variant on the studio take, and You’re Nogood (see Dilla entry above). These days I would also recommend Descending Moonshine Dervishes (Kuckuck, 1982/recorded 1975) over Persian Surgery Dervishes (Shandar, 1975), which I mentioned in the original entry on Reed Streams in the first Top Ten; a lot of the harmonic material in Descending can also be heard in Terry’s dream-team 1975 meeting with Don Cherry in Köln, which has been bootlegged several times in the last few years. Finally, Steffen Schleiermacher recorded the elusive “Keyboard Study #1” (as well as “#2,” which had already seen release in a version by Germ on the BYG label and as “Untitled Organ” on Reed Streams), albeit on a programmed electronic keyboard, on the CD Keyboard Studies (MDG, 2002). As you might expect it’s a little synthetic-sounding, but it also has a weird kinetic edge (imagine the “Baba O’Riley” intro being played on a Conlon Nancarrow player piano) that’s lacking in later acoustic piano renditions recorded by Gregor Schwellenbach and Fabrizio Ottaviucci. But any of these versions is rewarding for those interested in Riley’s early output.

Henry Flynt, Charlemagne Palestine: A few of the artists on that first Top Ten list went from being sorely under-documented to having a plethora of material on the market, and Henry and Charlemagne are at the top of the heap. I stand by You Are My Everlovin, finally reissued on CD by Recorded in 2001, as Henry’s peak achievement, but I’m also partial to “Glissando,” a tense, feverish raga drone from 1979 that Recorded put out on the Glissando No. 1 CD in 2011. Charlemagne’s Four Manifestations On Six Elements double album still holds up well, as does an album of material initially recorded for it, Arpeggiated Bösendorfer and Falsetto Voice (Algha Marghen, 2017). The Strumming Music LP on Shandar is a definitive performance, and best heard as an unbroken piece on the New Tone CD reissue from 1995. Godbear (CD on Barooni, vinyl on Black Truffle), originally recorded for Glenn Branca’s Neutral label (which had also scheduled a Phill Niblock release before going belly-up), has 1987 takes of “Strumming Music” and two other massive pieces that date from the late 70s, “Timbral Assault” and “The Lower Depths”; Algha Marghen released a vintage full-length concert of the latter as a triple CD.

Steve Reich: Not a particularly rare record, but his “Variations on Winds, Strings and Keyboards,” a 1979 piece for orchestra on a 1984 LP issued by Phillips (paired with an orchestral arrangement of John Adams’ “Shaker Loops”), is often overlooked among the works from his “golden era” and I’d frankly rate it as his best orchestral piece.

Phill Niblock, Eliane Radigue: As with Henry and Charlemagne, after a slow start as “recording artists” loads of CDs by these two have appeared over the last twenty years. Phill and Eliane’s music was never best served by the vinyl format anyway—you won’t find a lackluster release by either composer, go to it.

Jon Gibson: I called “Cycles,” from Gibson’s Two Solo Pieces, “one of the ultimate organ drones on record” in the first Top Ten list, and it remains so, but Phill Niblock’s”Unmounted/Muted Noun” from 2019′s Music for Organ ought to sit right beside it. Meanwhile, Superior Viaduct’s recent Gibson double album Songs & Melodies 1973-1977 collects some great pieces from the same era as Two Solo Pieces, with players including Arthur Russell, Peter Zummo, Barbara Benary, and Julius Eastman.

John Stevens: In Top Ten #2 I mentioned John Stevens’ presence on the first side of John Lennon & Yoko Ono’s Life With the Lions; the Stevens-led Spontaneous Music Orchestra’s For You To Share (1973) documents his performance pieces “Sustained Piece” and “If You Want to See A Vision,” where musicians and vocalists sustain tones until they run out of breath and then begin again, which result in a highly meditative and organic drone/sound environment. In my early 00′s Digger Choir performances at Issue Project Room we did “Sustained Piece,” and Stevens’ work was a big influence on conceptualizing those concerts, where the only performers were the audience themselves. The CD reissue on Emanem from 1998 added “Peace Music,” an unreleased studio half-hour studio cut with a similar Gagaku–meets–free/modal jazz vibe. I also mentioned “Sustained Piece” in my liner notes to Natural Information Society’s Mandatory Reality too, if that helps as a point of reference.

Anthony Moore: Back in ’97 I wondered “How and why Polydor was convinced to release these albums [Pieces from the Cloudland Ballroom and Scenes from the Blue Bag] is beyond me (anyone know the story)?” That mystery was ultimately solved by Benjamin Piekut in his fascinating-even-if-you-never-listen-to-these-guys book Henry Cow: The World is A Problem (Duke University Press, 2019)—it turns out it was all Deutsche Gramophone’s idea!

Terry Jennings, Maryanne Amacher, Julius Eastman–“Three Great Minimalists With No Commercially Available Recordings” (sidebar from Minimal Top Ten list #2): Happily this no longer applies to these three, although Terry and Maryanne are still under-represented. One archival recording of Jennings and Charlotte Moorman playing a short version of “Piece for Cello and Saxophone” appeared on Moorman’s 2006 Cello Anthology CD box set on Alga Marghen, and he’s on “Terry’s Cha Cha” on that 2004 John Cale New York in the 60s Table of the Elements box too. John Tilbury recorded five of his piano pieces on Lost Daylight (Another Timbre, 2010) and Charles Curtis’ version of “Song” appears on the aforementioned Performances and Recordings 1998-2018 triple CD.

Whether or not Maryanne should really be considered a Minimalist (or a sound artist, for that matter) is, I guess, debatable, but I primarily see her as the unqualified genius of the generation of composers who emerged in the post-Cage era, and the classifications ultimately don’t matter—remember she was on those Swarm of Drones/ Throne of Drones/ Storm of Drones ambient techno comps in the 90s, and I’d call her music Gothic Industrial if it would get more people to check it out (and that might be fun to try, come to think of it). She made a belated debut with the release of the Sound Characters CD on Tzadik in 1998, an event I found significant enough to warrant pitching an interview with her to the WIRE, who agreed—it was my first piece for them. Her music was/is best experienced live (the Amacher concert I saw at the Performing Garage in 1993 is still, almost three decades later, the greatest concert I’ve ever witnessed) but that Tzadik CD is reasonably representative, and there was a sequel CD on Tzadik in 2008. More recently Blank Forms issued a live recording of her two-piano piece “Petra” (a concert I also attended, realizing when I got there that it was in the same Chelsea church where Connie Burg, Melissa Weaver and I recorded with Keiji Haino for the Gerry Miles with Keiji Haino CD). While it’s somewhat anomalous in Amacher’s canon, making a piece for acoustic instruments available for home consumption would doubtless have been more palatable to the composer herself, who rightly felt that CDs and LPs didn’t do justice to the extraordinary psychoacoustic phenomena intrinsic to her electronic music. “Petra” is more reminiscent of Morton Feldman than anything else, with a few passages that could be deemed “minimal.” Some joker posted a 26-minute, ancient lo-fi “bootleg” (their term) recording of her “Living Sound, Patent Pending” piece from her Music for Sound-Joined Rooms installation/performance series on SoundCloud, which is a little like looking at a Xerox of a Xerox of a photo of the Taj Mahal; but you can still visit the Taj Mahal more easily than hearing this or any of Maryanne’s work in concert or in situ, so sadly, it’s better than nothing (and longer than the 7 minute edit of the piece on the Ohm: Early Gurus of Electronic Music CD from 2000).

A few years after Top Ten #2 I was on the phone with an acquaintance at New World Records, who told me he was listening to a Julius Eastman tape that they were releasing as part of a 3CD set. Say what?!?!? Unjust Malaise appeared shortly thereafter and was a revelation. Arnold Dreyblatt had sent me a live tape some time before then of an Eastman piece labeled “Gangrila”—that turned out to be “Gay Guerrilla,” and is surely one of my five favorite pieces of music in existence (the tape Arnold sent was from the 1980 Kitchen European tour and I consider it to be a more moving performance than the Chicago concert that appears on the CD, although it’s an inferior recording). The other multiple piano pieces on Unjust Malaise more than lived up to the descriptions of Eastman performances that I’d read. The somewhat berserk piano concert I mentioned in that entry seems similar to another live tape issued as The Zurich Concert (New World, 2017), and “Femenine,” a piece performed by the S.E.M. Ensemble, came out on Frozen Reeds in 2016. Eastman’s rediscovery is among the most vital and gratifying developments of recent music history–kudos must be given to Mary Jane Leach, herself a Minimalist composer, for diligently and doggedly tracking down Eastman’s recordings and archival materials and bringing them to the light of day.

The Lost Jockey—I was unaware of any releases by this group besides their Crepuscule LP until I stumbled onto a self-titled cassette from 1983 on YouTube. Like the album, the highlight is a piece by Orlando Gaugh–an all-time great Philip Glass rip-off, “Buzz Buzz Buzz Went the Honeybee,” which has the amusing added bonus of having the singers intoning the rather bizarre title phrase as opposed to Glassian solfège. Also like the album, he rest of the cassette is so-so Pop Minimalism.

Earth: Dylan Carlson keeps on keepin’ on, and while I can’t say I’ve kept up with him every step of the way, usually when I check in I’m glad I did. However I’d like to take this opportunity to humbly disavow the snarky comments about Sunn 0))) I made in this entry in Top Ten list #3. Those were a reflection of my general aversion to hype, which was surrounding them at the time, and of seeing two shows that in retrospect were unrepresentative (I was thunderstruck by a later show I saw in Mexico City in 2009). Stephen O’Malley has proven to be as genuinely curious, dedicated and passionate about drone and other experimental music as they come, and the reissue of the mind-blowing Sacred Flute Music from New Guinea on his Ideologic Organ label is a good reminder of how rooted Minimalism is in ethnic music, and how almost interchangeable certain examples of both can be.

And while we’re in revisionist mode, let’s go full circle all the way back to the very first sentence of the introduction to the first Minimal Top Ten: “I know what you’re thinking: ECM Records, New Age, Eno ambients, NPR, Tangerine Dream. Well forget all that shit.” Hey, that stuff’s not so bad! I was probably directing that more at the experimental-phobic indie rock folks I encountered at the time, and expressing a lingering resentment towards the genre-confusion of the 80s (i.e. having dig through a bunch of Kitaro records in the New Age bins in hopes of finding Reich, Riley, or Glass; even Loren Mazzacane got tagged New Age once in a while back then, believe it or not), which probably hindered my own discovery of Minimalism. What can I say, I’m over it!

Copyright © 2020 Alan Licht. All rights reserved. Do not repost without permission.

32 notes

·

View notes