#Czech films about the holocaust

Text

📷 From the documentary film “Forbidden Love – Queer Victims of the Nazi Dictatorship”

Documentary shows three poignant fates of queer Nazi victims

Persecuted, arrested and murdered: The documentary “Forbidden Love – Queer Victims of the Nazi Dictatorship” shows, with celebrity support, what it meant to be a queer person who was an enemy of the Nazi state.

Auto-translate from German [original from Queer.de]:

The documentary will be broadcast on January 27th, the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holocaust.

The approximately 45-minute documentary by Sebastian Scherrer shows how the Nazis increased punishments and terrorized queer people. For this purpose, the fates of the three queer protagonists Elli Smula, Liddy Bacroff and Rudolf Brazda are not only examined, but the voices of historians and well-known faces are also sought. …

The documentary does not force the protagonists into the role of victims

All three take on a “sponsorship” for one of the protagonists in order to shed light on their fate. These include Elli Smula, who was persecuted as a lesbian, and Liddy Bacroff, who was harassed by the authorities as a "transvestite", as well as Rudolf Brazda, who was imprisoned in the Buchenwald concentration camp because of his homosexuality.

Over 50,000 queer people were demonstrably persecuted at the time, many of whom were oppressed, imprisoned or murdered. But as cruel as the Nazi era was for LGBTI people, the documentary proves that despite the most adverse circumstances, some managed to live out their identity and assert themselves during the Nazi era.

And although the protagonists actually became "victims" of the Nazi regime, they are not presented in the documentary in a "victim role", but as self-confident people who did not want to let the Nazi regime change them.

All three take on a “sponsorship” for one of the protagonists in order to shed light on their fate. These include Elli Smula, who was persecuted as a lesbian, and Liddy Bacroff, who was harassed by the authorities as a "transvestite", as well as Rudolf Brazda, who was imprisoned in the Buchenwald concentration camp because of his homosexuality.

Over 50,000 queer people were demonstrably persecuted at the time, many of whom were oppressed, imprisoned or murdered. But as cruel as the Nazi era was for LGBTI people, the documentary proves that despite the most adverse circumstances, some managed to live out their identity and assert themselves during the Nazi era.

And although the protagonists actually became "victims" of the Nazi regime, they are not presented in the documentary in a "victim role", but as self-confident people who did not want to let the Nazi regime change them.

Other fates during the Nazi era are also discussed.

In addition to the events surrounding Smula, Bacroff and Brazda, other fates from the Nazi era are also highlighted, such as that of SA leader Ernst Röhm. The homosexual officer was murdered on behalf of Adolf Hitler in 1934.

But Magnus Hirschfeld, who worked as a sex researcher for the decriminalization of homosexuality, is also remembered. For his efforts, the Nazi regime punished him by storming his institute.

The right degree between personal stories and education

The documentary manages to find the right degree between the narration of personal fates and the factual education about the Nazi era. In addition to the protagonists, historical documents are shown from which shocking evidence emerges.

At that time, sexual acts between men were described as “fornication” and homosexuality as a “popular plague”. The so-called “Pink Angle” publicly stigmatized homosexual men in concentration camps. Czech Holocaust expert Anna Hájková sums it up aptly: "Queer people embodied everything the Nazis hated."

And the prominent faces and activists always find the right words, express criticism or ask legitimate questions. Finally, on some of the stumbling blocks, for example, there are deadnames of deceased trans people, which denounces them.

Finally, reference is made to the current situation of queer people, because hate is increasing again. That's why the documentary ends with an impressive sentence:

Love should never become a crime again.

#international day of remembrance of the victims of the holocaust#forbidden love#queer#queer history#lgbqti#holocaust#trans#pink triangle#homosexuality#magnus hirschfeld#lgbt#lgbtq#fascism#germany#nazi#2024

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

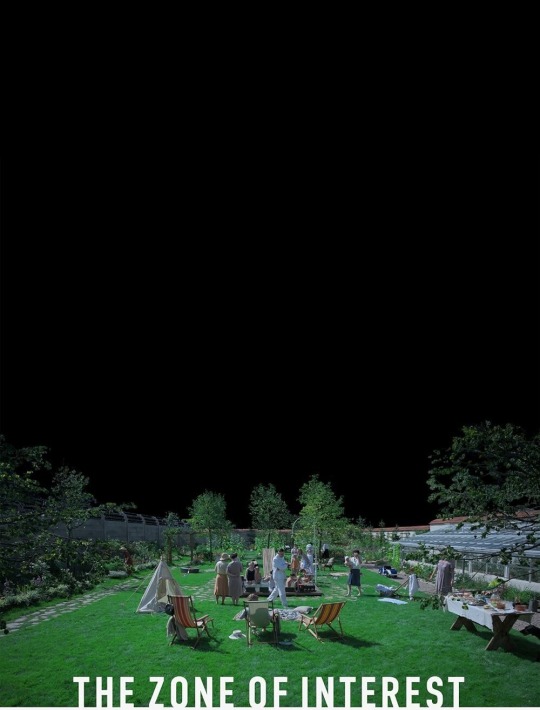

Movies I watched this week (Year 4, week 8)

"Rudy calls me The Queen Of Auschwitz"...

After waiting for many months, I finally had a chance to watch Jonathan Glazer's transcendental The Zone of Interest. It's the most spine-chilling horror film I've ever seen, and I'll bet it will grow to become one of the greatest films of all time.

Making art about genocide is nearly impossible. Few Holocaust movies were able to tackle the topic honorably (Claude Lanzmann's epic Shoah', and Alain Resnais's 'Night and fog', both documentaries). But fictional dramas about concentration camps and Nazism are usually an affront against humanity. This one is different: Restraint, oppressive to the bone, ambient, extraordinarily disturbing. 9/10.

🍿

2 with Swedish actress Lena Olin:

🍿 Another film about the holocaust. One life is the directorial feature film debut of James Hawes, who directed two of my favorite 'Black Mirror' episodes ('Hated in the nation' and 'Smithereens'). Anthony Hopkins plays Nicholas Winton, who saved the lives of 699 Czech children by transferring them to England, just before the beginning of World War 2.

Watching Hopkins is always a delight, but unfortunately much of the film is a historical flash-back, a genre I dislike in principle. But even as much as I can't stand the period posturing and sub-par acting in the flash-back, the pathos and manipulation used here were so effective, it left me in tears for most of the film. 8/10.

🍿 The Adventures of Picasso is a Swedish surrealist comedy, very much in a 1970's absurdist style. Including a few lovely scenes (A dubbed Rossini duet, violinist Henri Rousseau ascending to heaven to the tune of 'I dream of 'Jenny', an excessive cauliflower farting performance) among mostly low-brow and stereotypical caricatures. Woody Allen did it better in 'Midnight in Paris'. 2/10.

🍿

And a third movie about related topic, Hitler Lives - Wow! A virulent anti-German propaganda film, originally written by Dr. Seuss and directed by Frank Capra, but which was remade by new director Don Siegel, and even went on to win the 1945 Oscar. Commissioned by the War Department, it was so over the top, that even George Patton walked out of the screening for top military brass, calling it 'Bullshit'.

['Today I learnt' that Don Siegel directed his first two movies in 1945, this and 'Star in the Night', and both of them won the Oscars, one for Short drama, and one for Short documentary!]

🍿

River, my second charming comedy by Japanese director Junta Yamaguchi (after his original 'Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes'). Like the previous one, it's a quirky "2 minute time loop" story, where every 2 minutes, time rewinds and everyone returns to where they were before. It takes some getting used to, but it's more relaxed [maybe because the location is a traditional inn, 'Ryokan', in a beautiful rural area]. The dozen participants adjust their responses to the Loop, and learn to behave accordingly. 100% on Rotten Tomatoes.

🍿

2 Korean police thrillers:

🍿 Cold eyes is about a team of surveillance officers tracking a gang of highly-sophisticated criminals. Excellent fast-action, cat and mouse plot (with improbable tech). 6/10.

🍿 The Outlaws is a fast action, brutal story of a gang war in seedy Chinatown in Seoul. Tough as nails and hard hitting, the captain in charge of the investigation goes against one of the most ruthless screen villains I've ever seen, a loan shark who likes to chop people's hands off. Lead officer Ma Dong Seok is relentless and uncompromising, and with the most powerful knock-out punches. The all-out brawl at the airport bathroom executed as well as the fight scenes from 'True Lies' and 'Terminator 2'.

The film was a big success in Korea, and they already made 3 sequels to it. 8/10 - My most entertaining surprise film of the week!

🍿

"Something is rotten in the State of Denmark".

Laurence Olivier's brilliant adaptation of Shakespeare's Hamlet, the first British film to win the Oscar for 'Best Picture'. It got everything: A son avenging the murder of his father, a ghost story, incest and madness, suicide, poetry, politics of the day, as well as stunning photography in German Expressionist style. Also, a 'foppish courtier', tight tights for the men and giant protruding codpieces.

I wish I was much more versed with Elizabethan English, so that I could enjoy it even more.

🍿

Marlene Dietrich as a conniving murderess X 2:

🍿 First watch: Witness for the Prosecution, a terrific Billy Wilder drama with Charles Laughton and Marlene Dietrich, and with Tyrone Power in his final role. My dislike for pompous courtroom dramas was surpassed by the wit and fluidity of the Agatha Christie story. 8/10.

🍿 The 1950 Stage Fright was a mediocre Hitchcock Noir, with a similar set up, featuring a conspiring, duplicitous Marlene Dietrich as a remorseless co-conspirator to a murder. Not as engaging, or as staged. The most memorable performance in it was the 'Laziest Gal in Town' scene, which was parodied so well by Madeline Kahn. 3/10.

🍿

Re-watching 'Singing in the rain' X 2:

🍿 Another frequent re-watch: Nancy Meyers perfect feel-good hug, The intern. Meyers directed only 7 movies, but wrote nearly 20 romantic blockbusters. She's a superb screenwriter, and this is a marvelously-constructed bonbon. De Nero is super cute, and even Anne Hathaway is wonderful here. The relationship between them develops in stages so well. And it culminates with the heart-warming You Were Meant for Me scene at the Mark Hopkins Hotel. 10/10.

It's amusing to think how different this movie will be if Michael Caine and Tina Fey (or Reese Witherspoon) would play in it, as originally planned. That would actually be a good project for a 2026 A.I. "Alternative Version" re-make! ♻️

/ Female Director

🍿 So I had to watch Singing in the rain again. If there ever was a perfect musical, this is it. There isn't much I can say that hadn't been said before many times, so here:

The 'You were meant for me' scene which is the emotional center of the movie, happens (as it often does in well-timed Hollywood classics) at the 48:25 mark, precisely one hour before the end.

Gene Kelly wears this ridiculously-giant white chapeau. I don't even know what it's called.

The musical numbers are composed of mostly very long shots, with few, nearly invisible, cuts!

Debbie Reynolds was only 19 when she was cast as Kathy Selden.

And, Clockwork Orange's Alex DeLarge definitely altered forever any connotation to the beauty of 'just singing and dancing in the rain'...

10/10 - will watch again. ♻️

🍿

Once Within a Time is Godfrey Reggio's 8th experimental feature. Like his famous Koyaanisqatsi trilogy, it's an abstract non-linear montage, but this time with a different element of story-telling, that of children watching today's world disintegrate.

With a Philip Glass score (once again), exec-produced by Steven Soderbergh and with a cameo by Mike Tyson (?). It's a psychedelic, surreal trip, with animated dreamscapes, like La Planète sauvage on digital Psilocybin. 5/10.

🍿

"Today I learnt" about Stig Anderson, "The fifth ABBA". He was their promoter, manager, lyricist and manager. Stikkan is a new Swedish documentary about one of the most fascinating and influential people of Swedish music. (Even though the narrator has a very irritating intonation!).

🍿

"Obviously, Jesse is Tom and we're all Greg's"...

From Southbank Central, A fascinating panel discussion with Jesse Armstrong and four other brilliant writers of 'Succession' on September 15, 2023. 8/10.

And just to follow up, I revisited the masterful 'Pilot' episode, Celebration. Directed by Adam McKay, it introduced all the unpleasant main characters in such a way that one is being lured to obsessively follow them for 40 additional hours. It's also obvious from the very first viewing of Kendall Roy, with his sloped shoulders and forlorn sad-dog looks, that he is a 'Loser' who'll never be able to fill his father's big shoes. 10/10. ♻️

🍿

"I like your hairstyle... I like your polyester look"...

When Saturday night fever first opened in the 70's, I was a film snob and refused to see it. After stumbling upon the iconic opening scene today, I though I'll give it a shot. But Tony Manero still was a strutting, empty-headed, raping asshole, and the rest was not for me either. "Rocky but for Disco"? I saw Rocky recently and it was a great story. This was a ridiculous, sexist, stereotypical chauvinist, and pathetic ride. And was there a Ron Jeremy cameo? 1/10.

🍿

“I’ll be watching you, al-jazeera..”

Where do I even start? Poultrygeist, Night of the Chicken Dead is a piece of low-budget Troma schlock full of absurd, tongue-in-cheek body-fluid gore, the kind of shitshow I usually avoid. I thought I'll be able to see how bad can it really be, but after another explosive diarrhea gross-out scene that lasted for 2 or 3 minutes, I had to give it a permanent pass. 'Bye, Lloyd Kaufman. 1/10 - didn't finish.

🍿

(My complete movie list is here)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Holidays 9.23

Holidays

Al-Yaom Al-Watany (Saudi Arabia)

Batman Day (DC Comics)

Bi Visibility Day (UK)

Bonn Phchum Ben (Ancestors’ Day; Cambodia)

Celebrate Bisexuality Day (a.k.a. Bisexual Pride & Bi Visibility Day)

Checkers Day

Chuuk Liberation Day (Micronesia)

Day of the Genocide of Lithuania's Jews (Lithuania)

Dogs in Politics Day

Flashbulb Day

Grito de Lares (Puerto Rico)

Haryana Veer and Shahidi Divas (Haryana, India)

Holocaust Memorial Day (Lithuania)

I Have Not Yet Begun To Fight Day

Innergize Day [Day after Equinox]

International Day of Sign Languages

International Restless Legs Syndrome Day

Kyrgyz Language Day (Kyrgyzstan)

Landscape-Nursery Day

Learn to Code Day

National AFM Day (a.k.a. Acute Flaccid Myelitis Day)

National Checkers Day

National Field Marketer’s Day

National Go With Your Gut Day

National Property Manager’s Day

Neptune Day

New Year's Day (Constantinople)

Nintendo Day

Pancake Queen Memorial Day

Puffy Shirt Day (Seinfeld)

Restless Legs Awareness Day

Speed Racer Day

Sügise Algus (a.k.a. Sügisene Pööripäev; Estonia, Finland, Sweden)

Teachers’ Day (Brunei)

Thrue Bab (Blessed Rainy Day; Bhutan)

Teal Talk Day

That'll Be the Day Day

World Maritime Day (UN)

Food & Drink Celebrations

Chewing Gum Day

Gastronomy Day (France)

Great American Pot Pie Day

Key Lime Pie Day

National Apple Cider Vinegar Day

National Snack Stick Day

Za’atar Day

4th Friday in September

Love Note Day [4th Friday]

National BRAVE Day [4th Friday]

National Hug Your Boss Day [4th Friday; also 9.13]

Native American Day (California) [4th Friday]

Feast Days

Adomnán (Christian; Saint)

Augustalia (Ancient Rome)

Cicciolina Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Cissa of Crowland (or of Northumbria; Christian; Saint)

Citua (Feast to the Moon; Ancient Inca)

Corneille (Positivist; Saint)

Feast of Chukem (Deity of Footraces; Colombia)

Feast of the Ingathering (a.k.a. Harvest Home, Kirn or Mell-Supper; UK)

Festival of Papa, Wife of Rangi (Maori; New Zealand)

Festival of the Goddess Ninkasi (Sumerian Goddess of Brewing)

Linus, Pope (Christian; Saint)

Manolo and Carlo Flamingo (Muppetism)

Padre Pio (Christian; Saint)

Sossius (Christian; Saint)

Thecla (Roman Catholic Church)

Walk the Plank Day (Pastafarian)

Xanthippe and Polyxena (Christian; Saint)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Fortunate Day (Pagan) [39 of 53]

Taian (大安 Japan) [Lucky all day.]

Unlucky Day (Grafton’s Manual of 1565) [45 of 60]

Premieres

Abraxas, by Carlos Santana (Album; 1970)

Baa Baa Black Sheep (TV Series; 1976)

The Blacklist (TV Series; 2013)

Blonde (Film; 2022)

Bridges to Babylon, by The Rolling Stones (Album; 1997)

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Film; 1969)

Corpse Bride (Animated Film; 2005)

Enola Holmes (Film; 2020)

The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt (Novel; 2013)

Heroes, by David Bowie (Song; 1977)

The Jetsons (Animated TV Series; 1962)

Mad About You (TV Series; 1992)

Modern Family (TV Series; 2009)

Mom (TV Series; 2013)

North, by Elvis Costello (Album; 2003)

The Nylon Curtain, by Billy Joel (Album; 1982)

Parallel Lines, by Blondie (Album; 1978)

People Are Strange, by The Doors (Song; 1967)

Phantom of the Opera, by Gaston Leroux (Novel; 1909)

The Shawshank Redemption (Film; 1994)

Sledge Hammer! (TV Series; 1987)

When I Was Cruel, by Elvis Costello (Album; 2002)

Today’s Name Days

Helene, Thekla (Austria)

Elizabeta, Lino, Pijo, Tekla, Zaharija (Croatia)

Berta (Czech Republic)

Linus (Denmark)

Diana, Dolores, Tekla (Estonia)

Mielikki, Miisa, Minja (Finland)

Constant, Faustine (France)

Linus, Gerhild, Thekla (Germany)

Iris, Polixeni, Rais, Xanthippe, Xanthippi (Greece)

Tekla (Hungary)

Lino, Pio, Rebecca (Italy)

Ivanda, Omula, Vanda, Veneranda (Latvia)

Galintas, Galintė, Linas, Teklė (Lithuania)

Snefrid, Snorre (Norway)

Boguchwała, Bogusław, Libert, Minodora, Tekla (Poland)

Zdenka (Slovakia)

Constancio, Lino, Pío, Tecla (Spain)

Tea, Tekla (Sweden)

Autumn, Linnet, Linnette, Lynette, Lynn, Lynne (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 261 of 2022; 104 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 7 of week 37 of 2022

Celtic Tree Calendar: Muin (Vine) [Day 16 of 28]

Chinese: Month 8 (Guìyuè), Day 23 (Jia-Xu)

Chinese Year of the: Tiger (until January 22, 2023)

Hebrew: 22 ʼĔlūl 5782

Islamic: 21 Ṣafar 1444

J Cal: 21 Aki; Sixday [21 of 30]

Julian: 5 September 2022

Moon: 7%: Waning Crescent

Positivist: 9 Shakespeare (10th Month) [Vondel]

Runic Half Month: Ken (Illumination) [Day 9 of 15]

Season: Summer (Day 89 of 90)

Zodiac: Virgo (Day 26 of 31)

0 notes

Text

Holidays 9.23

Holidays

Al-Yaom Al-Watany (Saudi Arabia)

Batman Day (DC Comics)

Bi Visibility Day (UK)

Bonn Phchum Ben (Ancestors’ Day; Cambodia)

Celebrate Bisexuality Day (a.k.a. Bisexual Pride & Bi Visibility Day)

Checkers Day

Chuuk Liberation Day (Micronesia)

Day of the Genocide of Lithuania's Jews (Lithuania)

Dogs in Politics Day

Flashbulb Day

Grito de Lares (Puerto Rico)

Haryana Veer and Shahidi Divas (Haryana, India)

Holocaust Memorial Day (Lithuania)

I Have Not Yet Begun To Fight Day

Innergize Day [Day after Equinox]

International Day of Sign Languages

International Restless Legs Syndrome Day

Kyrgyz Language Day (Kyrgyzstan)

Landscape-Nursery Day

Learn to Code Day

National AFM Day (a.k.a. Acute Flaccid Myelitis Day)

National Checkers Day

National Field Marketer’s Day

National Go With Your Gut Day

National Property Manager’s Day

Neptune Day

New Year's Day (Constantinople)

Nintendo Day

Pancake Queen Memorial Day

Puffy Shirt Day (Seinfeld)

Restless Legs Awareness Day

Speed Racer Day

Sügise Algus (a.k.a. Sügisene Pööripäev; Estonia, Finland, Sweden)

Teachers’ Day (Brunei)

Thrue Bab (Blessed Rainy Day; Bhutan)

Teal Talk Day

That'll Be the Day Day

World Maritime Day (UN)

Food & Drink Celebrations

Chewing Gum Day

Gastronomy Day (France)

Great American Pot Pie Day

Key Lime Pie Day

National Apple Cider Vinegar Day

National Snack Stick Day

Za’atar Day

4th Friday in September

Love Note Day [4th Friday]

National BRAVE Day [4th Friday]

National Hug Your Boss Day [4th Friday; also 9.13]

Native American Day (California) [4th Friday]

Feast Days

Adomnán (Christian; Saint)

Augustalia (Ancient Rome)

Cicciolina Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Cissa of Crowland (or of Northumbria; Christian; Saint)

Citua (Feast to the Moon; Ancient Inca)

Corneille (Positivist; Saint)

Feast of Chukem (Deity of Footraces; Colombia)

Feast of the Ingathering (a.k.a. Harvest Home, Kirn or Mell-Supper; UK)

Festival of Papa, Wife of Rangi (Maori; New Zealand)

Festival of the Goddess Ninkasi (Sumerian Goddess of Brewing)

Linus, Pope (Christian; Saint)

Manolo and Carlo Flamingo (Muppetism)

Padre Pio (Christian; Saint)

Sossius (Christian; Saint)

Thecla (Roman Catholic Church)

Walk the Plank Day (Pastafarian)

Xanthippe and Polyxena (Christian; Saint)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Fortunate Day (Pagan) [39 of 53]

Taian (大安 Japan) [Lucky all day.]

Unlucky Day (Grafton’s Manual of 1565) [45 of 60]

Premieres

Abraxas, by Carlos Santana (Album; 1970)

Baa Baa Black Sheep (TV Series; 1976)

The Blacklist (TV Series; 2013)

Blonde (Film; 2022)

Bridges to Babylon, by The Rolling Stones (Album; 1997)

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Film; 1969)

Corpse Bride (Animated Film; 2005)

Enola Holmes (Film; 2020)

The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt (Novel; 2013)

Heroes, by David Bowie (Song; 1977)

The Jetsons (Animated TV Series; 1962)

Mad About You (TV Series; 1992)

Modern Family (TV Series; 2009)

Mom (TV Series; 2013)

North, by Elvis Costello (Album; 2003)

The Nylon Curtain, by Billy Joel (Album; 1982)

Parallel Lines, by Blondie (Album; 1978)

People Are Strange, by The Doors (Song; 1967)

Phantom of the Opera, by Gaston Leroux (Novel; 1909)

The Shawshank Redemption (Film; 1994)

Sledge Hammer! (TV Series; 1987)

When I Was Cruel, by Elvis Costello (Album; 2002)

Today’s Name Days

Helene, Thekla (Austria)

Elizabeta, Lino, Pijo, Tekla, Zaharija (Croatia)

Berta (Czech Republic)

Linus (Denmark)

Diana, Dolores, Tekla (Estonia)

Mielikki, Miisa, Minja (Finland)

Constant, Faustine (France)

Linus, Gerhild, Thekla (Germany)

Iris, Polixeni, Rais, Xanthippe, Xanthippi (Greece)

Tekla (Hungary)

Lino, Pio, Rebecca (Italy)

Ivanda, Omula, Vanda, Veneranda (Latvia)

Galintas, Galintė, Linas, Teklė (Lithuania)

Snefrid, Snorre (Norway)

Boguchwała, Bogusław, Libert, Minodora, Tekla (Poland)

Zdenka (Slovakia)

Constancio, Lino, Pío, Tecla (Spain)

Tea, Tekla (Sweden)

Autumn, Linnet, Linnette, Lynette, Lynn, Lynne (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 261 of 2022; 104 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 7 of week 37 of 2022

Celtic Tree Calendar: Muin (Vine) [Day 16 of 28]

Chinese: Month 8 (Guìyuè), Day 23 (Jia-Xu)

Chinese Year of the: Tiger (until January 22, 2023)

Hebrew: 22 ʼĔlūl 5782

Islamic: 21 Ṣafar 1444

J Cal: 21 Aki; Sixday [21 of 30]

Julian: 5 September 2022

Moon: 7%: Waning Crescent

Positivist: 9 Shakespeare (10th Month) [Vondel]

Runic Half Month: Ken (Illumination) [Day 9 of 15]

Season: Summer (Day 89 of 90)

Zodiac: Virgo (Day 26 of 31)

0 notes

Text

Forbidden Dreams (Smrt krásných srnců) - Karel Kachyna, 1987

Forbidden Dreams (Smrt krásných srnců) – Karel Kachyna, 1987

Director Karel Kachyna (The Ear) gets his metaphors in early in Forbidden Dreams, otherwise known by its more evocative Czech title, Smrt krásných srnců (The Death of Beautiful Deer). Mr Popper (Karel Heřmánek), a Jewish vacuum cleaner salesman who can’t stop hopping into bed with his female customers, is out fishing in the countryside with his two eldest sons. Through his…

View On WordPress

#Czech cinema#Czech comedy#czech drama#Czech film reviews in English#Czech films about the holocaust#Czech films about World War 2#Forbidden Dreams 1987 Film Review#Forbidden Dreams 1987 Karel Kachyna#Smrt krásných srnců 1987 Karel Kachyňa

1 note

·

View note

Text

The British Schindler

He saved 669 children.

Nicholas Winton was a young British stockbroker who rescued 669 Czech Jewish children from being sent to Nazi death camps. He never told anybody of his heroism, and the story only came out 50 years later after his wife found an old briefcase in the attic containing lists of children he’d saved.

Nicholas was a 29 year old clerk at the London stock exchange getting ready for a ski trip to Switzerland when he received an urgent call from his friend Martin Blake. Known to be passionately opposed to Nazism, Martin urged Nicholas to cancel his vacation and come to Prague immediately. He told Nicolas, “I have a most interesting assignment and I need your help. Don’t bother bringing your skis.”

It is a testament to Nicolas’ sterling character and strong moral compass that he didn’t waver for a moment. It was an easy decision to sacrifice his fun and relaxing ski trip and instead travel to a dangerous place on a mysterious mission.

Two months earlier, in October 1938, Nazi Germany had annexed the Sudetenland It was clear that the Nazis would soon occupy all of Czechoslovakia. When he reached Prague, Nicholas was shocked by the huge influx of refugees fleeing from the Nazis. In early November, the Kristallnacht pogrom occurred in Germany and Austria. Jews were killed in the street and hundreds of synagogues burned down, as well as Jewish-owned businesses. This horrifying event shocked the Jewish community in eastern Europe, and thousands were now desperate to flee.

Born to Jewish parents, Nicholas was actually Jewish himself. However, his parents changed their name from Wertheim and converted to Christianity before he was born. Nicholas was baptized and raised as a Christian, and he didn’t consider himself Jewish (although was doubtless aware that Hitler would.)

In Prague, organizations were springing up to help sick and elderly refugees, but Nicholas noticed that nobody was trying to help the children. In his words, “I found out that the children of refugees and other groups of people who were enemies of Hitler weren’t being looked after. I decided to try to get permits to Britain for them. I found out that the conditions which were laid down for bringing in a child were chiefly that you had a family that was willing and able to look after the child, and fifty pounds, which was quite a large sum of money in those days, that was to be deposited at the Home Office. The situation was heartbreaking. Many of the refugees hadn’t the price of a meal. Some of the mothers tried desperately to get money to buy food for themselves and their children. The parents desperately wanted at least to get their children to safety when they couldn’t manage to get visas for the whole family. I began to realize what suffering there is when armies start to march.”

Nicholas knew something had to be done, and he decided to be the one to do it. He later remembered, “Everybody in Prague said, ‘Look, there is no organization in Prague to deal with refugee children, nobody will let the children go on their own, but if you want to have a go, have a go.’ And I think there is nothing that can’t be done if it is fundamentally reasonable.”

Nicholas decided to find homes for the children in the UK, where they would be safe. He set up a command center in his hotel room in Wenceslas Square and his first step was to contact the refugee offices of different national governments and see how many children they could accept. Only two countries agreed to take any Jewish children: Sweden and Great Britain, which pledged to accept all children under age 18 as long as they had homes and fifty pounds to pay for their trip home.

With this green light from Great Britain, Nicholas did everything possible to find homes for the children. He returned to London and did much of the planning from there, which enabled him to continue working at the Stock Exchange and soliciting funds from other bankers to pay for his work with the refugees. Winton needed a large amount of money to pay for transportation costs, foster homes, and many other necessities such as food and medicine.

Nicholas placed ads in newspapers large and small all over Great Britain, as well as in hundreds of church and synagogue newsletters. Knowing he had to play on people’s emotions to convince them to open their home to young strangers who didn’t even speak English, Nicholas printed flyers with pictures of children seeking refuge. He was tireless in his efforts and persuaded an incredible number of heroic Brits to welcome the traumatized young refugees into their homes and hearts.

The office in Wenceslas Square was manned by fellow Brit Trevor Chadwick. Every day terrified parents came in and begged him to find temporary homes for their children. Despite Nicholas’ success in finding places for the kids to stay, British and German government bureaucrats made things difficult, demanding multiple forms and documents. Nicholas said, “Officials at the Home Office worked very slowly with the entry visas. We went to them urgently asking for permits, only to be told languidly, ‘Why rush, old boy? Nothing will happen in Europe.’ This was a few months before the war broke out. So we forged the Home Office entry permits.”

The first transport of children boarded airplanes in Prague which took them to Britain. Nicholas organized an amazing seven more transports, all of them by train, and then boat across the English Channel. The children met their foster families at the train station and Winton took great care in making the matches between children and foster parents.

The children’s transport organized by Nicholas Winton was similar to the later, larger Kindertransport operation, but specifically for Czech Jewish children. Nicholas saved an astounding 669 children on eight transports. Tragically, the largest transport of all was scheduled for September 1, 1939 – but on that day, Hitler invaded Poland and all borders were closed by Germany. Winton was haunted for decades by the remembrance of the 250 children he last saw boarding the train. “Within hours of the announcement, the train disappeared. None of the 250 children aboard was seen again. We had 250 families waiting at Liverpool Street that day in vain. If the train had been a day earlier, it would have come through. Not a single one of those children was heard of again, which is an awful feeling.”

Nicholas joined the British military and spent the rest of the war serving as a pilot in the Royal Air Force, attaining the rank of Flight Lieutenant. After the war, Nicholas worked for the International Refugee Organization in Paris, where he met and married Grete Gjelstrup, a Danish secretary. They moved to Maidenhead, in Great Britain, and had three children. Their youngest child, Robin, had Down Syndrome, and at that time children with the condition were usually sent to institutions. However Nicholas and Grete wouldn’t consider it and instead kept their son at home with the family. Tragically, Robin died of meningitis the day before his sixth birthday. Nicholas was devastated by the loss, and became an active volunteer with Mencap, a charity to help people with Down Syndrome and other developmental delays. He remained involved in Mencap for over fifty years.

Humble – and perhaps traumatized by the children on the train he wasn’t able to save – Nicholas rarely talked about his wartime heroism and his own family didn’t know the details. It was only in 1988 that Nicholas Winton became widely known. His wife found an old notebook of his containing lists of the children he saved. Working with a Holocaust researcher, she tracked down some of the children and located eighty of them still living in Britain. These grown children, some with grandchildren, found out for the first time who had saved them.

The BBC television show called That’s Life! invited Nicholas to the filming an episode that became one of the most emotional clips in TV history. With Nicholas in the audience, the host told his story, including photos and details about some of the children he’d saved. Then the told Nicholas that one of those children was the woman in the seat next to him! They embraced, teary eyed, and the host announced there were more grown children in the audience as well. She asked everybody who owed their life to Nicholas Winton to stand up. The entire audience stood up, as Nicholas sat stunned, wiping away the tears.

After that, Nicholas was showered with honors, including a knighthood for services to humanity. Known as the British Schindler, he met the Queen multiple times and received the Pride of Britain Award for Lifetime Achievement, both for saving refugee children and working with Mencap to improve the lives of people with cognitive differences. There are multiple statues of him in Prague and the UK, and his story was the subject of three films.

Nicholas Winton died in Britain in July 2015, at age 106. Today there are tens of thousands of people who owe their lives to Nicholas Winton.

For saving hundreds of Jewish children, we honor Nicholas Winton as this week’s Thursday Hero.

Accidental Talmudist

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

Im sorry, 'Racist and has NAZI WHAT

FUCK this got so long because the more I dug out the worse I realized the fic was

The fic in question has like, really stereotypical depictions of Czechs and Russians, to the point where Czech Skull was given a “Russian” sounding name that wasn’t even a real name? Plays into the stereotype of all Slavic countries being basically Russia and also what the fuck, please research names

Only a few cases are: Kept referring to an already named black character as just “black man” in multiple casual mentions of him, called him exotic, and called him ebony-skinned. Used the slur g*psies for Romanian people A LOT, as if it’s a descriptor and not a derogatory term. Had her oc say she had to learn Japanese even though Mandarin worked for most Asian countries which is literally not true and really racist. Said this about Jewish people which is probably the worst fucking example here

They also reference a lot of issues that did not need to come up and they likely have no business writing it? Like mentioning slave trading in Arabia, African border wars, the Holocaust, inserting their oc into a real life coup that happened in Libya (like yeah there are films that do this for an interesting plot and to teach some sort of lesson but maybe dON’T DO THIS IN ANIME FANFICTIION)

It’s literally tagged racism but if your fic has racism I think it should be condemned, not normalized in most interactions even for the time period, and it should certainly not be in the narration that’s meant to reflect the author

There’s also some sideplot where a character is a former Nazi who’s supposed to be developing out of it but one, are you equipped to write this???? and two, why are you exploring such a topic in... anime fanfiction

And somehow I see this fic recommended way too much in the fandom. Like this seems so disconnected from khr in the worst way anyway I do not see the appeal. Not to mention it’s 50+ chapters with a sequel

#khr#katekyo hitman reborn#i hid an answer in the illusion#its... bad#wow a lot of the word stereotype on this blog lately#someone gotta say it i guess#and ive seen a czech person express discomfort for that first part#Anonymous

24 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

pyrrhiccomedy You know, this scene is so powerful to me that sometimes I forget that not everyone who watches it will understand its significance, or will have seen Casablanca. So, because this scene means so much to me, I hope it’s okay if I take a minute to explain what’s going on here for anyone who’s feeling left out. Casablanca takes place in, well, Casablanca, the largest city in (neutral) Morocco in 1941, at Rick’s American Cafe (Rick is Humphrey Bogart’s character you see there). In 1941, America was also still neutral, and Rick’s establishment is open to everyone: Nazi German officials, officials from Vichy (occupied) France, and refugees from all across Europe desperate to escape the German war engine. A neutral cafe in a netural country is probably the only place you’d have seen a cross-section like this in 1941, only six months after the fall of France. So, the scene opens with Rick arguing with Laszlo, who is a Czech Resistance fighter fleeing from the Nazis (if you’re wondering what they’re arguing about: Rick has illegal transit papers which would allow Laszlo and his wife, Ilsa, to escape to America, so he could continue raising support against the Germans. Rick refuses to sell because he’s in love with Laszlo’s wife). They’re interrupted by that cadre of German officers singing Die Wacht am Rhein: a German patriotic hymn which was adopted with great verve by the Nazi regime, and which is particularly steeped in anti-French history. This depresses the hell out of everybody at the club, and infuriates Laszlo, who storms downstairs and orders the house band to play La Marseillaise: the national anthem of France. Wait, but when I say “it’s the national anthem of France,” I don’t want you to think of your national anthem, okay? Wherever you’re from. Because France’s anthem isn’t talking about some glorious long-ago battle, or France’s beautiful hills and countrysides. La Marseillaise is FUCKING BRUTAL. Here’s a translation of what they’re singing: Arise, children of the Fatherland! The day of glory has arrived! Against us, tyranny raises its bloody banner. Do you hear, in the countryside, the roar of those ferocious soldiers? They’re coming to your land to cut the throats of your women and children! To arms, citizens! Form your battalions! Let’s march, let’s march! Let their impure blood water our fields! BRUTAL, like I said. DEFIANT, in these circumstances. And the entire cafe stands up and sings it passionately, drowning out the Germans. The Germans who are, in 1941, still terrifyingly ascendant, and seemingly invincible. “Vive la France! Vive la France!” the crowd cries when it’s over. France has already been defeated, the German war machine roars on, and the people still refuse to give up hope. But here’s the real kicker, for me: Casablanca came out in 1942. None of this was ‘history’ to the people who first saw it. Real refugees from the Nazis, afraid for their lives, watched this movie and took heart. These were current events when this aired. Victory over Germany was still far from certain. The hope it gave to people then was as desperately needed as it has been at any time in history. God I love this scene. freekicks not only did refugees see this movie, real refugees made this movie. most of the european cast members wound up in hollywood after fleeing the nazis and wound up. paul heinreid, who played laszlo the resistance leader, was a famous austrian actor; he was so anti-hitler that he was named an enemy of the reich. ugarte, the petty thief who stole the illegal transit papers laszlo and victor are arguing about? was played by peter lorre, a jewish refugee. carl, the head waiter? played by s.z. sakall, a hungarian-jew whose three sisters died in the holocaust. even the main nazi character was played by a german refugee: conrad veidt, who starred in one of the first sympathetic films about gay men and who fled the nazis with his jewish wife. there’s one person in this scene that deserves special mention. did you notice the woman at the bar, on the verge of tears as she belts out la marseillaise? she’s yvonne, rick’s ex-girlfriend in the film. in real life, the actress’s name is madeleine lebeau and she basically lived the plot of this film: she and her jewish husband fled paris ahead of the germans in 1940. her husband, macel dalio, is also in the film, playing the guy working the roulette table. after they occupied paris, the nazis used his face on posters to represent a “typical jew.” madeleine and marcel managed to get to lisbon (the goal of all the characters in casablanca), and boarded a ship to the americas… but then they were stranded for two months when it turned out their visa papers were forgeries. they eventually entered the US after securing temporary canadian visas. marcel dalio’s entire family died in concentration camps. go back and rewatch the clip. watch madeleine lebeau’s face. https://78.media.tumblr.com/eb576ea3f782ea59d435b8da875e79a0/tumblr_inline_oky3pnIElT1qe7a3m_540.png https://78.media.tumblr.com/10057f222566275d8853a4a8047e0183/tumblr_inline_oky3b3bfpr1qe7a3m_540.png https://78.media.tumblr.com/44e8f5e0745cedf253e819eba07c039d/tumblr_inline_oky3s0TiBp1qe7a3m_540.png casablanca is a classic, full of classic acting performances. but in this moment, madeleine lebeau isn’t acting. this isn’t yvonne the jilted lover onscreen. this is madeleine lebeau, singing “la marseillaise” after she and her husband fled france for their lives. this is a real-life refugee, her real agony and loss and hope and resilience, preserved in the midst of one of the greatest films of all time. http://notmypresidentno.tumblr.com/post/175638713168/thebibliosphere-blood-on-my-french-fries

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Anne Frank - Parallel

Voice/Vision had the honor of hosting Dr. Michael Berenbaum on October 14, 2018 where he presented "Holocaust Denial, Vulgarization and and Falsification." We recently found out about a documentary that Dr. Berenbaum has taken part in and wanted to share. Dr. Berenbaum … himself —historian and professor of Jewish studies is one of the historians and curators of various Holocaust memorials provide the historical background as “#AnneFrank” visits a rail car museum exhibit, or the Czech Pinkas Synagogue, where the names of all the Czech Jews murdered in the Shoah are written on the walls.

The film’s purpose is not merely to tell the story of Anne Frank, as many have before, or to visualize her environment and the facts of her life, but rather to look at Anne’s generation of teenagers and open up specifically for young people the difficult questions of how such blind evil could occur, before asking how each of us will respond. This is a mirror for us all.

Through Anne’s diary, survivors’ recollections and historical footage, we can feel as though we are there with Anne.

The narrator declares that the glimpse into Anne’s household is like watching ourselves and imagining how we and our families would react in the same situation. Would we not become irritable, wildly rebellious and drawn into fantasies as an escape from our ‘prison’? Would we pretend, ignore mistreatment, or conform ourselves in order to keep safe and comfortable? Could we still be ‘me’ at all?

Of course, looking in a mirror is not always pleasant, but it is important. If we see bad signs, we can do something to stop them from worsening.

Also, in this ‘mirror’ we feel uncomfortable as we see the footage of embarrassed villagers who’ve been living alongside the German concentration camps without opposing them (for if they had, their lives would surely have been cut short). As a consequence for turning a blind eye to gross evils, the locals are forced by Allied soldiers to enter the concentration camps, view the extreme destruction and personally handle the bodies, granting them proper burial.

“The moral lesson: it’s very much about those little moments… choices.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Shop on Main Street (1965, Czechoslovakia)

Putting “New Wave” in a sentence referring to a film movement is asking for trouble. Whether the New Wave is French, Iranian, or Japanese in origin, the term implies a series of films and filmmakers breaking narrative and aesthetic norms in conventional moviemaking, exalting innovation. New Wave directors from those respective countries include Jean-Luc Godard and Agnès Varda; Forough Farrkohzad and Mohsen Makhmalbaf; Nagisa Oshima and Seijun Suzuki. For those I have just listed, I am not denying their talents, their importance to film history. But show any of their films to someone who is less familiar with these New Waves, without the contextual understanding of the environment their works were released, and befuddlement and distaste will likely abound. Rare is the New Wave film that can be shown to unfamiliar eyes and minds without appropriate context.

Ján Kadár and Elmar Klos’ The Shop on Main Street (adapted from Ladislav Grosman’s novel of the same name) is sometimes considered a part of the then-concurrent Czechoslovak New Wave. And if one considers it part of that New Wave, then it is one of the more comprehendible, technically grounded films of that movement. It certainly qualifies as one of those New Wave exceptions – a film that can be digested by a viewer not accustomed to older movies or has any experience with Czech- or Slovak-language cinema. I consider The Shop on Main Street a Czechoslovak New Wave film. When one looks beneath its World War II-era surface, its politics extend beyond its condemnation of Nazi Germany’s treatment of Jews and the local Slovak population. Though rooted in the nation’s past, it was as timely as Věra Chytilová’s Daisies (1966) upon release. The film outdoes many New Wave films by playing fast and loose with genre expectations: a black comedy in the first half, a tragedy in the second. Nazi Germany’s state-executed hatred, if not including the fringe groups inspired by their example, is no longer; Czechoslovakia has long been split in two. The Shop on Main Street and its censure of those who manipulate the oppressed, while pointing their fingers elsewhere.

In March 1939, the Slovak Republic was carved out of Czechoslovakia as a client state of Nazi Germany. The Slovak Republic never received recognition from the Allies (with the brief exception of the USSR until they were invaded by Germany), and they soon set about the process of Aryanization. Aryanization was a process in which Jewish property and businesses were to be put into “Aryan” ownership so as to “de-Jew” the economy. In The Shop on Main Street, Slovak carpenter Anton "Tóno" Brtko (Jozef Kroner) is offered by an official the ownership of a button store owned by the elderly, near-deaf Rozália Lautmannová (Ida Kamińska). Mrs. Lautmannová, a widow, is unaware that there is a war, that Czechoslovakia is being occupied by invaders intent on seizing her business and exterminating her fellow Jews. She welcomes Tóno as a helper and believes – mishears, really – that he is her nephew. Tóno, thrown into this awkward situation, soon learns that Mrs. Lautmannová’s store is not profitable and depends on community donations. The Jewish community implore Tóno to stay as de jure owner of the store, for fears that a more exploitative owner might be selected were he to give it up. Tóno agrees, accepting a small payment, and dedicating himself to the store’s and Mrs. Lautmannová’s welfare. They find time to see the humor in her mishearing and his stubbornness. In the final scenes, Tóno and Mrs. Lautmannová must make a horrific decision.

Czechoslovakia’s communist government, during the Czechoslovak New Wave, frowned upon films that could be construed as anarchic, insurrectionist, troublemaking. The Shop on Main Street – unlike many of its contemporaries – avoided government meddling. The villains here are the Nazis, whom communist forces across the Eastern bloc fought against. On its surface, The Shop on Main Street assigned no criticism towards Czechoslovakia’s communist regime or to communism. Yet the braggadocious Nazis are a minority in this film. A detestable sociopolitical minority becomes empowered when others sympathize with them, rationalize their prejudices and atrocities, and fail to defend the targets of that minority. We see non-Jewish Slovaks shrugging their shoulders about Aryanization. Why not pocket some extra money with this new policy, they reason, in a sluggish economy and a better-armed invading force now patrolling their streets? These are economically desperate times for non-Jewish Slovaks (and, if my hunches are correct, probably even more so for Jewish Slovaks), so they will use whatever programs necessary to survive, rooted entirely in self-interest.

The communist censors probably thought something, while viewing The Shop on Main Street, that is resurgent in modern-day Europe: that Nazi Germany’s anti-Semitic policies (from Aryanization to concentration camps and much more) were Germany’s responsibility and no one else’s. Complicity with the Nazi agenda is being debated among historians, politicians, and within the 125-minute runtime of The Shop on Main Street. For Tóno, the invaders inspire mutterings out of earshot and disdainful moues. His wife, Evelína (Hana Slivková), is concerned only about money – she is thrilled when she learns that the Aryanization program will give them a financial cushion (so she thinks), never contemplating the possibility this it is the beginning of the Jewish community’s ruin. Has she ever known someone from the community? It is not clear. Tóno’s non-Jewish acquaintances, too, are unfazed by these proclamations. Life is already difficult in the Slovak Republic (Czechoslovakia itself was not formed because its patchwork of ethnicities had common political pursuits and aspirations, but due to expedience and tensions with other ethnic groups), and any economic lifeline that will be offered to the non-Jews will be taken. Are those who support and/or participate in Aryanization irredeemable, given their desperation and the Nazi aim to manufacture conflict between Jews and non-Jews? Is Tóno an accessory of the Nazis?

These are questions that may seem small when grasper the enormity of the Holocaust. But that is the intention of directors Kadár and Klos, who often worked together co-directing films. In his directorial statement for the film in the New York Herald Tribune’s January 23, 1966 issue, Kadár (whose parents and sister were murdered at Auschwitz) writes that he was the principal director for this film – Klos agreed to be a sort of secondary director for The Shop on Main Street, deferring to Kadár because of his personal connection to the material. Klos also notes:

[Klos] knows that I am not thinking of the fate of all the six million tortured Jews, but that my work is shaped by the fate of my father, my friends’ fathers, mothers of those near to me and by people whom I have known. I am not interested in the outer trappings—figures, statements, generalizations. I want to make emotive films.

This is not an epic film intended to sweep viewers into the broadest discussions of the Holocaust. The Shop on Main Street is foremost a film about an unlikely connection – one separated by age, language, and faith – that is formed when exploitation would be so much easier. This is where The Shop on Main Street derives its pathos, in places where despair ought to triumph.

When Tóno meets Mrs. Lautmannová for the first time, he is surprised to see how disconnected she is from the world. She knows little of what is happening outside of the storefront door, and she delights in the company of her few – but dedicated – customers and the letters she receives from a relative in America (she hasn’t received their letter in some months). She closes the store on the Sabbath (sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday), retreating to her bedroom to pray and to read. Her friends in the Jewish community realize her frailty and lack of understanding, deciding to protect her from the news of pogroms and war. When lacking any authority to make laws or force political change, all they possess are their words and neighborliness – which they share with Tóno freely. Tóno is struck by their generosity, and his friendship with Mrs. Lautmannová grows. Ida Kamińska (the Polish actress was sixty-six years old when The Shop on Main Street was released, and nicknamed the Mother of the Jewish Stage) and Jozef Kroner (a star of numerous Slovak films, but this is his most recognized work) play off each other. In a series of successive (gentle and dark) misunderstandings, these two commoners are each other’s foils. He is a drinker, impatient, and needs to learn diplomacy. She is kind, religious, and concerningly naïve.Their performances are incredible, helping The Shop on Main Street pull off its tonal transitions that should have seen this film crumble into treacle.

youtube

Zdeněk Liška’s score to The Shop on Main Street alternates between foreboding string lines wracked with minor key, string-crossing double stops signaling the precariousness of the story’s developments, the unusual situation the characters find themselves in, and emotional torment. A memorable, carnival-like march that opens the film is used to stunning effect when employed ironically. Liška’s cue placement helps Kadar and Klos achieve the respective comedic and dramatic moods that the screenplay and actors so nimbly establish.

Lengthy is the canon of films depicting and commenting on the Holocaust. The Shop on Main Street, avoiding extensive declarations, is one of the earliest films on that list. Its examinations on complicity and the extent of human callousness reverberate to a present where Holocaust denial and blame-shifting continues to rail against the truth of untold millions and their descendants. It is a tremendous film, one containing unexpected power through its performances and the impossible situations the main characters find themselves in. Bathed in white, the final seconds of The Shop on Main Street show a wonderful dream, one that could only be crafted by a director pouring his decades-long grief for his parents and sister into his work. As the camera dances to the right, away from the shop on main street, we see in the background the shops and homes of the Jewish community now silent.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. The Shop on Main Street is the one hundred and fifty-eighth feature-length or short film I have rated a ten on imdb.

#The Shop on Main Street#Jan Kadar#Elmar Klos#Ida Kaminska#Jozef Kroner#Hana Slivkova#Martin Holly Sr.#Frantisek Zvarik#Ladislav Grosman#Zdenek Liska#Vladimir Novotny#Czechoslovak New Wave#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

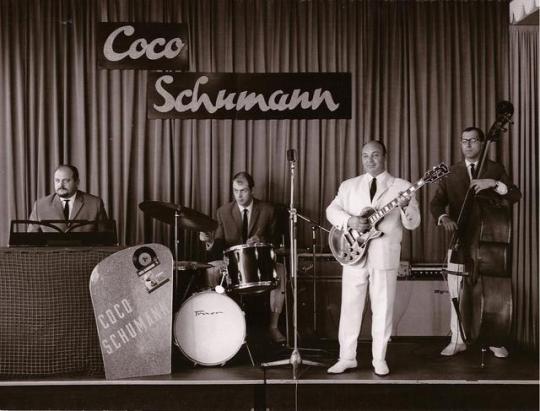

Coco Schumann RIP

Coco Schumann was a jazz musician who was forced to play the guitar in Auschwitz as victims were selected for the gas chamber

Coco Schumann, who has died aged 93, was always at pains to stress that he was, as he put it, “a musician who spent time in a concentration camp, not a concentration camp prisoner who made music”. He said that music had defined his life, and he was convinced it was music that had been responsible for his survival.

Partly out of a wish not to allow the Nazis a prominent place in his biography, and because he thought no one would believe his story, and partly because of the horrors he had witnessed during the more than two years he spent incarcerated, it took him more than half a century to talk about the experience. “For years I didn’t speak about it, Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, Dachau, I thought no one would believe I had been in those places,” he said in 2014.

But one day, at an event for concentration camp survivors in the mid-1980s, someone challenged him. “He said to me, if you don’t speak about it, who will tell people what really happened there? And in that moment a switch turned on in me, and I thought he was right,” Schumann said. He became increasingly aware of the importance of his role as one of the last remaining “first voice” eye-witnesses of the Holocaust.

Schumann was infected by the jazz bug at the age of 13, when a friend played him Ella Fitzgerald’s new record A-Tisket A-Tasket, at a time when people held secret gramophone sessions with their friends to savour a music genre that had been officially classed as Negermusik (literally nigger music) and therefore “degenerate” by the Nazis. He taught himself the guitar and went on to make his name in Berlin’s underground jazz scene, where he regularly performed as a minor in a Gypsy swing band.

Owing to his father’s conversion to Judaism out of love for his mother, Schumann was classified as a Geltungsjude, or a person considered a Jew by law, and lived in permanent fear of being deported.

His first close shave came in 1942 when a group of SS officers entered the Berlin bar where he was playing, to arrest a Jewish member of the audience. Convinced of his own imminent capture, Schumann recalled approaching one of the officers and saying: “If you’re going to arrest him, you might as well arrest me too.” When asked why, he replied: “First of all I’m Jewish, secondly, I’m underage, and thirdly, I’m playing jazz.” He was ignored until a year later, after – so he always suspected – a romantic rival and a regular in the Rosita bar, where he often played, informed on him.

Schumann was transported in 1943 to Theresienstadt, in what is now Terezin, Czech Republic. There, aged 19, he began playing in a band called the Ghetto Swingers, founded by the Czech trumpeter Eric Vogel. In September 1944, they were given clean white shirts to perform in a propaganda film – an extension of a hoax played on the Red Cross the previous summer pretending that Jews had a decent life in the camp – to show the breadth of cultural activities on offer in the so-called “settlement”. The 20 minutes of the film that survives includes footage of the band leader, Martin Roman, and his elegant Ghetto Swingers performing in a bucolic scene in a pavilion in the park.

Immediately after, Schumann was deported to Auschwitz, along with other cast members and the director, Kurt Gerron, and his wife. There, thanks to a musician friend who recognised him, he was commandeered into a swing band that had the job of accompanying the tattooing of new arrivals and the selection process for the gas chambers, both to ease the SS guards’ boredom and to prevent panic among those who should not know they were going to their deaths. On a guitar that had belonged to a murdered Romani musician, Schumann was forced to play requests from the soldiers for hours at a time, everything from La Paloma to Alexander’s Ragtime Band. He later said he had always avoided the gazes of the children.

Born Heinz Schumann in Berlin, to Alfred, a decorator, and Hedwig (nee Rothholz), a hairdresser, he inherited a drum kit from his Uncle Arthur who was emigrating to Bolivia, and a six-string guitar from a cousin called up to the Wehrmacht. Heinz got his nickname, Coco, from a French girlfriend.

Having survived Auschwitz, where he nearly died from spotted fever, and then Dachau, Schumann was liberated by American troops in Bavaria while on a death march towards Innsbruck, and returned to his home city. His autobiography, The Ghetto Swinger: A Berlin Jazz-Legend Remembers (1997), which was turned into a musical in 2012, described being received back in the bars and clubs he had previously played in, as if he were a ghost appearing. “Everyone was surprised I’d survived,” he said.

It was while wandering down the bombed-out Kurfürstendamm boulevard in 1945 that Schumann met his future wife, Gertraud Goldschmidt, who approached him after recognising him as a member of the Ghetto Swingers from the time she herself had spent in Theresienstadt.

In 1950 he emigrated with Gertraud and her son to Australia, returning, homesick, in 1954, and subsequently spent years performing as a musician on cruise ships or playing with dance bands and radio ensembles and accompanying among others, Marlene Dietrich, Ella Fitzgerald and Helmut Zacharias. But he rarely revealed much about his past, saying: “I didn’t want to think people were applauding me out of sympathy.” In the 1990s, buoyed by the nostalgic comeback of swing, he formed the Coco Schumann Quartet, which enjoyed success and earned him considerable attention.

He was quick-witted, warm and charming, with a string of homemade bons mots always to hand, which one friend habitually recorded in a notebook that was published as a book, Coco, in 2015. In recent years, he suffered a brain tumour and that, and an injury to his finger following a fall in the summer of 2014, more or less put paid to performing in public. But he never stopped his daily habit of plucking at one of the many electric guitars he kept around his Berlin bungalow.

His 90th birthday was marked by a tribute gala put on by Germany’s cultural and political elite. Asked once how he managed to continue performing the very melodies he was forced to play in Auschwitz, that accompanied people to their deaths, Schumann replied: “Why should the music be tainted for the fact it was violated by the Nazis?” He added: “The pictures that burned themselves into my memory in Auschwitz are something I am forced to endure the whole time, regardless of whether I’m playing the tunes or not.”

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prisoners in Nazi concentration camps made music; now it's being discovered and performed - 60 Minutes - CBS News

The sign above the steel gates of Auschwitz reads "arbeit macht frei" – work sets you free. It was, of course, a chilling lie, an evil hoax. But there was one surprising source of temporary escape inside the gates: music. Composers and singers and musicians, both world-class and recreational, were among the imprisoned. And what's not widely known is that under the bleakest conditions imaginable, they performed and wrote music. Lots of it.

More than 6 million people, most of them Jews, died in the Holocaust, but their music did not, thanks in part to the extraordinary work of Francesco Lotoro. An Italian composer and pianist, Lotoro has spent 30 years recovering, performing, and in some cases, finishing pieces of work composed in captivity. Nearly 75 years after the camps were liberated, Francesco Lotoro is on a remarkable rescue mission, reviving music like this piece created by a young Jewish woman in a Nazi concentration camp in 1944.

Francesco Lotoro (Translation): The miracle is that all of this could have been destroyed, could have been lost. And instead the miracle is that this music reaches us. Music is a phenomenon which wins. That's the secret of the concentration camps. No one can take it away. No one can imprison it.

It seems unlikely, even impossible, that music could have been performed and composed at a place like this site of unspeakable evil, the most horrific mass murder in human history.

This is Auschwitz-Birkenau. The Nazi concentration camp in southern Poland. Set up by the Germans in 1940 as part of Hitler's "Final Solution," it became the largest center in the world for the extermination of Jews.

More than a million men, women and children died here. For those who passed through this entrance, known as the "Gate of Death," these tracks were a path to genocide and terror.

After they disembarked from cattle cars, most were sent directly to their deaths in the gas chambers.

The sounds of the camp included the screech of train brakes, haunting screams of families separated forever., the staccato orders barked by SS guards.

But also in the air: the sound of music, the language of the gods. This piece, titled "Fantasy" was written for oboe and strings, composed by a prisoner in Poland in 1942.

"In some cases, we are in front of masterpieces that could have changed the path of musical language in Europe."

At Auschwitz, as at other camps, there were inmate orchestras, set up by the Nazis to play marches and entertain. There was also unofficial music, crafted in secret, a way of preserving some dignity where little otherwise existed.

During the Holocaust, an entire generation of talented musicians, composers and virtuosos perished. 75 years later, Francesco Lotoro is breathing life into their work.

Francesco Lotoro (Translation): In some cases, we are in front of masterpieces that could have changed the path of musical language in Europe if they had been written in a free world.

Francesco Lotoro's work may culminate in stirring musical performances, but that's just the last measure, so to speak. His rescue missions, largely self-financed, begin the old fashioned way, with lots of hard work, knocking on doors, and face-to-face meetings with survivors and their relatives.

Jon Wertheim: I have heard that you've searched attics and basements. I imagine sometimes families don't even know the musical treasure they have.

Francesco Lotoro (Translation): There are children who have inherited all the paper material from their dad who survived the camp and stored it. When I recovered it, it was literally infested with paper worms. So before taking it, a clean-up operation was required, a de-infestation.

Lotoro grew up and still lives in Barletta, an ancient town on the Adriatic Coast of southern Italy. His modest home, which doubles as his office, is stuffed with tapes, audio cassettes, diaries and microfilm.

Aided by his wife, Grazia, who works at the local post office to support the family, Lotoro has collected and catalogued more than 8,000 pieces of music, including symphonies, operas, folk songs, and Gypsy tunes scribbled on everything from food wrapping to telegrams, even potato sacks.

The prisoner who composed this piece used the charcoal given to him as dysentery medicine and toilet paper to write an entire symphony which was later smuggled out in the camp laundry.

Jon Wertheim: He's using his dysentery medication as a pen and he's using toilet paper as paper.

Francesco Lotoro: Yes.

Jon Wertheim: And that's how he writes a symphony.

Francesco Lotoro: Yes, when you lost freedom, toilet paper and coal can be freedom.

It's a testament to resourcefulness, how far artists will go to create. It's also a testament to the range of emotions that prisoners experienced.

Jon Wertheim: What kind of music is this? This is 1944 in Buchenwald, in a camp.

Francesco Lotoro: This here a march.

Jon Wertheim: This is a march?

Francesco Lotoro: This surely to be scored for orchestra. (SINGS) It's a march.

Lotoro isn't just collecting this music, he's arranging it and sometimes finishing these works.

Jon Wertheim: Is this completed work or is this only partial?

Francesco Lotoro: No, they're only the melodies

This tender composition was written by a pole while he was in Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Lotoro says that if music like this isn't performed, it's as if it's still imprisoned in the camps. It hasn't been freed.

This wasn't an obvious calling for an Italian who was raised Roman Catholic, but from age 15, Lotoro says, he felt the pull of another religion.

Jon Wertheim: You converted to Judaism. You say you have a Jewish soul. Define what that means.

Francesco Lotoro (Translation): There was a rabbi who explained to me that when a person converts to Judaism, in reality he doesn't convert. He goes back to being Jewish. Doing this research is possibly the most Jewish thing that I know.

Francesco Lotoro (Translation): We Jews have a word which expresses this concept. Mitzvah. It is not something that someone tells you you must do, you know as a Jew that you must do it.

Lotoro's quest began in 1988 when he learned about the music created by prisoners in the Czech concentration camp Theresienstadt. The Nazis had set up the camp to fool the world into believing they were treating Jews humanely. Inmates were allowed to create and stage performances, some of which survive in this Nazi propoganda film. Lotoro was amazed by the level of musicianship and wondered what else was out there.

He reached out to Bret Werb, music curator at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington D.C. Werb says Francesco Lotoro is building on the legacy of others who have searched for concentration camp music, but Lotoro is taking it to the next level, making the scores performable.

Jon Wertheim: Why did people in concentration camps turn to music?

Bret Werb: It helped people to cope. It helped people to escape. It gave people something to do. It allowed them to comment on the experiences that they were undergoing.

Jon Wertheim: Did music save lives during the Holocaust?

Bret Werb: there is no doubt that being a member of an orchestra increased your chances of survival

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch is one of the last surviving members of the women's orchestra at Auschwitz. She is now 94 years old. We met her at her home in London.

Jon Wertheim: What had you heard about the camp before you arrived?

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: We heard everything that was going on there only we didn't – still tried not to believe it. But by the time I arrived there, in fact, I knew it was a reality, gas chambers and... yeah…

Jon Wertheim: You came prepared for the worst?

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: I came prepared for the worst, yes.

Her parents, German Jews, were taken away in 1942 and she never saw them again. She was just 18 when she arrived at the death camp a year later.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: We were put in some sort of block and waited all night, and the next morning there was a sort of welcome ceremony and there were lots of people sitting there doing the reception business. Like tattooing you, taking your hair off, et cetera. That's all done by prisoners themselves

The numbers are still visible on her left arm.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: I was led to a girl also a prisoner and a sort of normal conversation took place. And then she asked me what was I doing before the war. And like an idiot, I don't know, I said, "I used to play the cello." She said, "That's fantastic." "You'll be saved," she said. I had no idea what she was talking about.

Jon Wertheim: And that's how you heard there was an orchestra?

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: And this is your salvation?

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: That was my salvation, yeah.

The conductor of the orchestra was virtuoso violinist alma rose, niece of the famous Viennese composer, Gustav Mahler. Anita Lasker-Wallfisch says Rose, a prisoner herself, had an iron discipline and tried to focus attention away from the profound misery of the camp.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: I remember that we were scared stiff of her. She was very much the boss. And she knew very well that if she did not succeed to make a reasonable orchestra there, we wouldn't survive. So it was a tremendous responsibility this poor woman had.

The orchestra members all lived together in a wooden barracks like this – in Block 12 at Birkenau – known as the Music Block.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: We were based very near the crematoria. We could see everything that was going on.

Jon Wertheim: You're practicing your orchestra and you can see everything going on?

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: Yeah, I mean, once you are inside Auschwitz, you knew what was going on, you know.

Jon Wertheim: How do you play music pretending to ignore everything going on around you?

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: You arrive in Auschwitz you are prepared to go to the gas chamber. Somebody puts a cello in your hand, and you have a chance of life. Are you going to say "I'm sorry I don't play here I play in Carnegie Hall?" I mean, people have funny ideas about what it's like to arrive in a place where you know you're going to be killed.

Jon Wertheim: What I hear you say is that your ability to play the cello saved your life.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: Yeah, simple as that.

The main function of the camp orchestras: playing marches for prisoners every day here at the main gate, a way, literally to set the tempo for a day of work. And a way to count the inmates.

Jon Wertheim: Right here is where the men's orchestra played?

Francesco Lotoro: Yes there was like a procession and the orchestra played there.

The orchestras also played when new arrivals disembarked from trains at Birkenau, to give a sense of normalcy, tricking newcomers into thinking it was a hospitable place. This, when at the height of the killings, Nazis were murdering thousands of men, women and children each day. Evidence of the scope and scale of the atrocity still exists here: mountains of shoes, suitcases, glasses, shaving brushes, murder on an industrial scale.

Auschwitz archivists showed us some of the instruments that were taken out of the camp by orchestra members at the end of the war and later donated to the museum. This clarinet, a violin, and an accordion, as well as some of the music they played.

Jon Wertheim: This is the prisoner's orchestra the concentration camp Auschwitz?

Archivist: Yes.

Jon Wertheim: And this is the inventory of instruments.

Archivist: Yes, what is inside.

The orchestras also gave concerts on Sundays for prisoners and for SS officers.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch remembers playing for the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele, known as "the angel of death." Mengele conducted medical experiments on prisoners. His notorious infirmary still stands just steps from the railroad tracks in Birkenau.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: What was interesting is that these people, these arch criminals, were not uneducated people.

Jon Wertheim: That this monstrous man could still appreciate Schumann.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: How do you reconcile that?

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch: I don't.

Francesco Lotoro took us to another location where the Auschwitz camp orchestra played for Nazi officers and their families. It's just feet from the crematorium and within sight of the house of camp commandant Rudolf Hess.

Jon Wertheim: You were saying sometimes the smoke from the crematorium was so thick the musicians couldn't even see the notes in front of them.

Francesco Lotoro: Yes, it happened.

Jon Wertheim: It happened.

Francesco Lotoro: And it's tragic. Life and death were together.

Jon Wertheim: Life and death were intermingling.

Francesco Lotoro: And the point of connection of life and death is music. This is all we have about life in the camp. Life disappeared. We have only music. For me, music is the life that remained.

Music may be the life that remained, music like this 1942 piece titled "Fantasy", but it is the people behind the music that animate Francesco Lotoro's long and ambitious project. Their compositions created at a time when fundamental values were in danger.

Today, as the number of Holocaust survivors dwindles, it's more often their descendants Lotoro tracks down.

For 30 years, Lotoro has been on an all-consuming quest to collect music created by prisoners during the Holocaust. As he travels the world, mostly on his own dime, he is both a detective and an archaeologist, digging through the past to recover and discover actual artifacts. But maybe even more important, he meets with survivors and their family members to excavate the stories behind the music. We traveled to Nuremberg, Germany, to meet Waldemar Kropinski. He is the son of Jozef Kropinski, perhaps the most prolific and versatile composer in the entire camp constellation.

Waldemar Kropinski says his father's work was totally unknown before Francesco Lotoro brought it to light.

Waldemar Kropinski (Translation): I thought it was something that was of no interest to anyone because my father was already dead and not even one camp composition of his was performed in Poland.

Jozef Kropinski, a Roman Catholic, was 26 when he was caught working for the Polish resistance and sent to Auschwitz, where he became first violinist in the men's orchestra and started secretly composing, first for himself, and then for other prisoners. In 1942, he wrote this piece that he titled "Resignation".

Waldemar Kropinski (Translation): This is the list my father did seven months before his death.

Jon Wertheim: Oh this was all of his music.

Kropinski wrote hundreds of pieces of music during his four years of imprisonment, at Auschwitz and later at Buchenwald, including tangos, waltzes, love songs, even an opera in two parts.

Still more astonishing, he composed most of them at night, by candlelight, in a tiny room the Nazis diabolically called a pathology lab, where during the day, bodies were dismembered. Other prisoners had secured the space for kropinski so he could have a quiet place to compose.

Jon Wertheim: This is where he worked? This is the pathology room where the cadavers mounted and he wrote music.

Waldemar Kropinski (Translation): Yes.

Paper was in short supply, so Kropinski wrote music on items like this stolen Nazi requisition form…

Waldemar Kropinski (Translation): Because on the other side you had clean paper and my father could write notes…

Jon Wertheim: What's the name of this piece?

Waldemar Kropinski (Translation): A set of Christmas songs for a string quartet.

That's right, a few feet from piles of dead bodies, Jozef Kropinski wrote a suite of holiday songs. Waldemar says his father did it all to help raise the spirits of his fellow prisoners.

Waldemar Kropinski (Translation): His music was really touching hearts and very positive. It was important that the prisoners could hear something else in this time, something touching, so that they could go back in their memory to the old times, and feel encouraged.

In April 1945, as the Allies approached Buchenwald, the camp was evacuated and inmates were forced on a death march. Kropinski was able to smuggle out his violin and hundreds of pieces of music, some hidden in his violin case and others in a secret coat pocket, but only 117 survive today. On the march, he sacrificed the rest to build a fire for his fellow prisoners.

Jon Wertheim: You're saying your father took paper on which he had written compositions and used that to start a fire to give people heat to save their lives?

Waldemar Kropinski (Translation): Yes, not only his life but the lives of others.