#Sara Crewe: What Happened at Miss Minchin's

Text

“As to answering,” she used to say, “I don't answer very often. I never answer when I can help it. When people are insulting you, there is nothing so good for them as not to say a word—just to look at them and think. Miss Minchin turns pale with rage when I do it. Miss Amelia looks frightened, so do the girls. They know you are stronger than they are, because you are strong enough to hold in your rage and they are not, and they say stupid things they wish they hadn't said afterward. There's nothing so strong as rage, except what makes you hold it in—that's stronger. It's a good thing not to answer your enemies. I scarcely ever do. Perhaps Emily is more like me than I am like myself. Perhaps she would rather not answer her friends, even. She keeps it all in her heart.”

#Sara Crewe: What Happened at Miss Minchin's#Frances Hodgson Burnett#anger#A Little Princess#earlier version of it#quotations#verbal abuse

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

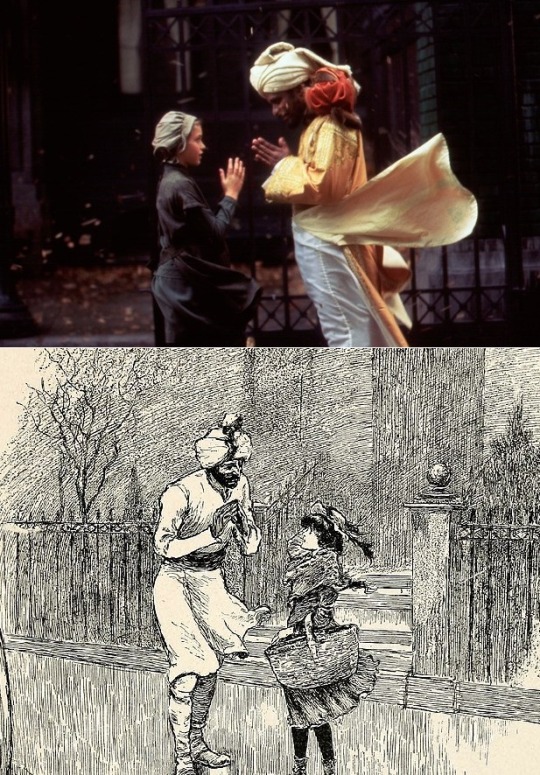

A Little Princess (Sara and Ram Dass).

Up: A scene from the film in 1995.

Down: Illustration from Sara Crewe; or, What Happened at Miss Minchin's (1888)

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

it's 'sara crewe or what happened at miss minchins' I used to love the little princess when i was a kid and its like the shorter version of that the author wrote first

but I also have red white and royal blue, the bell jar and atonement on tbe go rn 😬😬

omg i remember reading the bell jar. i haven't read the others, but i do hope you get to them and enjoy them!!

0 notes

Text

A Little Princess began as a short story called “Sara Crewe, or What Happened at Miss Minchin’s,” which was later expanded into a play, The Little Un-Fairy Princess, and finally published in novel form. The basic story in each version is the same: Wealthy, princess-like Sara Crewe loses her money after some unfortunate business dealings hasten her father’s death and is forced by the hostile and bitter headmistress of her school to work as a servant. Despite the horrific conditions she must now live under, Sara fights to maintain her dignity and graciousness and is finally discovered by her father’s former business partner and is restored to the wealth that wasn’t lost after all.

However, the earlier versions lack certain elements present in the final novel. Sometimes details are different, and Sara’s characterization undergoes a shift too. I will now elaborate on the details of these differences in the short story (saving the play for another time), and it’s going to get long.

The short story begins with an intro to the “Select Seminary” and Sara’s knowledge that she is no longer “Select” before flashing back to a quick overview of her coming there, at age eight (not seven, as in the novel).

In the novel, Sara is very withdrawn but does not cry after her father leaves, which surprises Miss Amelia. In the short story, she cries incessantly after he leaves, hates Miss Minchin, and looks down on Miss Amelia “who…lisped.”

Sara’s father is said to have inherited his money and doesn’t intend to stay in the army long.

Her relationships with her classmates are not addressed, nor are the diamond mines. The story moves quite quickly to Captain’s Crewe’s death and properly begins with Miss Minchin breaking the bad news to Sara.

Sara opts to put on the outgrown black dress herself instead of Minchin ordering the change.

In the novel, Miss Minchin objects to Sara carrying Emily and Sara refuses to put her down “not [...] with rudeness so much as with a cold steadiness with which Miss Minchin felt it difficult to cope...” This same moment occurs in the short story, but Sara has an extra line, bolded below, and the emphasis is not her lack of rudeness but on her willfulness. This Sara has not been immune to the negative consequences of her upbringing and seems to foreshadow Mary Lennox more than her characterization from the novel.

"No," said the child, "I won't put her down; I want her with me. She is all I have. She has stayed with me all the time since my papa died."

She had never been an obedient child. She had had her own way ever since she was born, and there was about her an air of silent determination under which Miss Minchin had always felt secretly uncomfortable. And that lady felt even now that perhaps it would be as well not to insist on her point. So she looked at her as severely as possible.

Sara is said to have a “little pale olive face.” No mention is made in this version of her mother being French, but this seems to suggest some kind of Mediterranean heritage.

She makes no comment about the relief of being able to work and her desire to teach. In fact, she’s rather rude to Minchin instead about her French. In the novel, Sara’s reluctance to correct the headmistress on the first day of class leads to the assumption that she needs to learn elementary French, until she can explain herself to the French teacher. But this Sara is much less concerned with princessly tact.

"I can speak French better than you, now," said Sara; "I always spoke it with my papa in India." Which was not at all polite, but was painfully true; because Miss Minchin could not speak French at all, and, indeed, was not in the least a clever person. But she was a hard, grasping business woman; and, after the first shock of disappointment, had seen that at very little expense to herself she might prepare this clever, determined child to be very useful to her and save her the necessity of paying large salaries to teachers of languages.

"Don't be impudent, or you will be punished," she said. "You will have to improve your manners if you expect to earn your bread. You are not a parlor boarder now. Remember that if you don't please me, and I send you away, you have no home but the street. You can go now."

Sara refuses to thank Minchin because “You are not kind,” without the novel’s addition “and it is not a home.”

Sara’s attic is next to the cook’s, not Becky’s. Becky is absent altogether.

As in the novel, Sara is said to “seldom” cry, but this seems inconsistent with her reaction to her father’s departure. The novel corrects this.

In the novel, she is interested in other people and forms bonds with her classmates. In the short story, she is quite standoffish and the narrator is as dismissive of the other girls as she is:

She had never been intimate with the other pupils, and soon she became so shabby that, taking her queer clothes together with her queer little ways, they began to look upon her as a being of another world than their own. The fact was that, as a rule, Miss Minchin's pupils were rather dull, matter-of-fact young people, accustomed to being rich and comfortable; and Sara, with her elfish cleverness, her desolate life, and her odd habit of fixing her eyes upon them and staring them out of countenance, was too much for them.

Almost all the other girls are unnamed. A line given to Lavinia in the novel comes in the short story from “one girl, who was sly and given to making mischief.”

Instead of Sara’s human relationships, her relationship with Emily is emphasized; this Sara is more constantly in her own head, perhaps to a fault. Note below too that there is definitely no Melchisedec in this version!

There were rat-holes in the garret, and Sara detested rats, and was always glad Emily was with her when she heard their hateful squeak and rush and scratching. One of her "pretends" was that Emily was a kind of good witch and could protect her. Poor little Sara! everything was "pretend" with her. She had a strong imagination; there was almost more imagination than there was Sara, and her whole forlorn, uncared-for child-life was made up of imaginings. She imagined and pretended things until she almost believed them, and she would scarcely have been surprised at any remarkable thing that could have happened.

The following passage is also interesting in terms of how this Sara relates to others. She’s rather judgmental toward her former schoolmates but isn’t too proud to resort to reading their discarded books or even a housemaid’s cheap sensational fiction. Sara in the novel never gets to that point, but this unnamed housemaid might be a precursor of Becky, with whom Sara in the novel engages in some of her more colorful fantasies of prisoners in the Bastille.

None of Miss Minchin's young ladies were very remarkable for being brilliant; they were select, but some of them were very dull, and some of them were fond of applying themselves to their lessons. Sara, who snatched her lessons at all sorts of untimely hours from tattered and discarded books, and who had a hungry craving for everything readable, was often severe upon them in her small mind. They had books they never read; she had no books at all. If she had always had something to read, she would not have been so lonely. She liked romances and history and poetry; she would read anything. There was a sentimental housemaid in the establishment who bought the weekly penny papers, and subscribed to a circulating library, from which she got greasy volumes containing stories of marquises and dukes who invariably fell in love with orange-girls and gypsies and servant-maids, and made them the proud brides of coronets; and Sara often did parts of this maid's work so that she might earn the privilege of reading these romantic histories.

Sara first interacts with Ermengarde when she find her crying over some books and speaks to her “perhaps rather disdainfully”—“And it is just possible she would not have spoken to her, if she had not seen the books.” She offers to read Ermengarde’s books and tell her about them, but it seems more motivated by a desire to read only, and Ermengarde offers her money, which she won’t take. This is unlike the novel, in which they meet shortly after Sara comes to school, witnesses Ermengarde suffering through a French lesson, and becomes indignant at how the girl is being bullied. Sara of the novel is more driven by compassion in this friendship; in the short story, she’s more concerned with how Ermengarde can benefit her.

Her motives for not sinking to the level of the people who mistreat her are a bit different from the novel. Novel!Sara embraces the role of princess and models herself after Marie Antoinette in being strong in the face of adversity. Her refusal to respond to cruelty comes from her belief that “A princess must be polite” and show mercy to those who are “poor, stupid, unkind, vulgar old thing[s], and don't know any better.” In the short story, she is driven by a more detached sense of justice and a knowledge of her own cleverness as something that should prevent her from being unjust. This Sara is still determinedly polite, but less warm and compassionate, more disdainful than pitying:

Sara recollected herself. She knew she was sometimes rather impolite in the candor of her remarks, and she did not want to be impolite to a girl who was not unkind—only stupid. Notwithstanding all her sharp little ways she had the sense to wish to be just to everybody. In the hours she spent alone, she used to argue out a great many curious questions with herself. One thing she had decided upon was, that a person who was clever ought to be clever enough not to be unjust or deliberately unkind to any one. Miss Minchin was unjust and cruel, Miss Amelia was unkind and spiteful, the cook was malicious and hasty-tempered—they all were stupid, and made her despise them, and she desired to be as unlike them as possible. So she would be as polite as she could to people who in the least deserved politeness.

Sara is not stuck in the black dress, as in the novel, but is said to wear also “a faded blue plush skirt, which barely covered her knees, a brown cloth sacque [short, loose-fitting jacket], and a pair of olive-green stockings which Miss Minchin had made her piece out with black ones, so that they would be long enough to be kept on.”

She has to build up to being kind and considerate to Ermengarde—in the book she “always felt very tender of Ermengarde, and tried not to let her feel too strongly the difference between being able to learn anything at once, and not being able to learn anything at all.” So her remarks about “Perhaps…to be able to learn things quickly isn’t everything” is more like a sudden revelation instead of an attempt to comfort her friend.

The Large Family is still said to have eight children, but nine are listed. In the novel, they are Ethelberta Beauchamp, Violet Cholmondeley, Sydney Cecil Vivian, Lilian Evangeline Maud Marion, Rosalind Gladys, Guy Clarence, Veronica Eustacia, and Claude Harold Hector. But in the short story: Ethelberta Beauchamp, Violet Cholmondeley, Sydney Cecil Vivian, Lilian Evangeline, Guy Clarence, Maud Marion, Rosalind Gladys, Veronica Eustacia, and Claude Harold Hector. Note the shifting of names and birth order.

Mr. Carrisford is said to be “elderly”; in the book he was at school with Sara’s father (in his thirties at the oldest?).

Sara speculates that Ram Dass “saved his master’s life in the Sepoy Rebellion” because “they look as if they might have had all sorts of adventures.” The Rebellion took place in 1857-59, plausible in a short story published in 1887, but not for a novel published in 1905.

Sara meets Ram Dass when he’s outside waiting for his employer to get in the carriage. They have conversations in which he tells her more about Carrisford.

Sara returns from the bun incident, gets yelled at and given old bread to eat, then goes upstairs thinking that she can’t pretend anything more and will have to dream instead. In the novel, the build-up to her darkest moment is more extreme.

Yes, when she reached the top landing there were tears in her eyes, and she did not feel like a princess—only like a tired, hungry, lonely, lonely child.

"If my papa had lived," she said, "they would not have treated me like this. If my papa had lived, he would have taken care of me."

Instead of falling asleep in her shabby attic and waking up to find it transformed, she discovers less dramatically upon entering her room that night.

Sara’s coming to return the monkey is told from her perspective, not that of Carrisford and the Carmichael children, which makes sense since her perspective is the only one in the story, as suitable for its length.

The conversation about her background is between her and Carrisford only, with no one else present, and when it’s figured out, he sends for Mr. Carmichael and Sara goes home with the monkey, confused about it all.

The next day Mr. Carmichael comes and speaks to Miss Minchin, then brings over his wife to lengthily explain to Sara who Carrisford is and what’s been going on.

Sara gets to meet the kids, whose real names are not revealed, but the oldest (”Claude Harold Hector”) goes to Eton (hence why he is not among the other older siblings in later versions?), and she stays with the Carmichaels that night. Mr. Carmichael’s first name is revealed to be Charles, and Mrs. Carrisford is given more dialogue.

There’s more emphasis on Sara’s relationship with the Carmichaels:

Then there was a sort of fairy nursery arranged for the entertainment of the juvenile members of the Large Family, who were always coming to see Sara and the Lascar and the monkey. Sara was as fond of the Large Family as they were of her. She soon felt as if she were a member of it, and the companionship of the healthy, happy children was very good for her. All the children rather looked up to her and regarded her as the cleverest and most brilliant of creatures—particularly after it was discovered that she not only knew stories of every kind, and could invent new ones at a moment's notice, but that she could help with lessons, and speak French and German, and discourse with the Lascar in Hindustani.

The confrontation with Miss Minchin is limited to the “always very fond of you” exchange, for less dramatic effect. Miss Minchin bills Mr. Carrisford a lot for Sara’s ���education and support” and he pays it as a favor to Sara and this happens:

When Mr. Carmichael paid it he had a brief interview with Miss Minchin in which he expressed his opinion with much clearness and force; and it is quite certain that Miss Minchin did not enjoy the conversation.

In conclusion, the Sara of the short story begins as more overtly spoiled and, although still noble, rather detached from and judgmental of other people. She is capable of rudeness and arrogance, and thus her struggle to maintain her politeness shows some growth. Her friendship with Ermengarde begins as an arrangement of convenience but becomes more meaningful as she comes to see Ermengarde as more of a person, although their relationship remains underdeveloped. The bun incident has a slightly different impact as a turning point for her in developing compassion. By the time she meets Carrisford and the Carmichaels, she is more capable of developing close relationships, less confined to her own head.

On the other hand, the Sara of the novel is more likable from the beginning, although not without her share of flaws, and more invested in other people throughout, which allows the reader to (perhaps) more readily feel for her in her sufferings, which are more detailed and drawn out. Neither characterization is necessarily superior, but they illustrate how Burnett’s vision for the character developed over time and adjusted to the needs of the two version’s formats.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Princess - Chapter 2

- “"She has silk stockings on!" whispered Jessie, bending over her geography also. "And what little feet! I never saw such little feet."

"Oh," sniffed Lavinia, spitefully, "that is the way her slippers are made. My mamma says that even big feet can be made to look small if you have a clever shoemaker. I don't think she is pretty at all. Her eyes are such a queer color."

I like to think that this a Cinderella reference, since A Little Princess is essentially a Cinderella story of fortune lost and found and apparently Burnett liked writing Cinderella stories in her romance novels for adults.

-“"Oh," sniffed Lavinia, spitefully, "that is the way her slippers are made. My mamma says that even big feet can be made to look small if you have a clever shoemaker. I don't think she is pretty at all. Her eyes are such a queer color."”

“She isn't pretty as other pretty people are," said Jessie, stealing a glance across the room; "but she makes you want to look at her again. She has tremendously long eyelashes, but her eyes are almost green."”

- “”She was a child full of imaginings and whimsical thoughts, and one of her fancies was that there would be a great deal of comfort in even pretending that Emily was alive and really heard and understood. After Mariette had dressed her in her dark-blue schoolroom frock and tied her hair with a dark-blue ribbon, she went to Emily, who sat in a chair of her own, and gave her a book.

"You can read that while I am downstairs," she said; and, seeing Mariette looking at her curiously, she spoke to her with a serious little face.

"What I believe about dolls," she said, "is that they can do things they will not let us know about. Perhaps, really, Emily can read and talk and walk, but she will only do it when people are out of the room. That is her secret. You see, if people knew that dolls could do things, they would make them work. So, perhaps, they have promised each other to keep it a secret. If you stay in the room, Emily will just sit there and stare; but if you go out, she will begin to read, perhaps, or go and look out of the window. Then if she heard either of us coming, she would just run back and jump into her chair and pretend she had been there all the time."

“"Comme elle est drole!" Mariette said to herself, and when she went downstairs she told the head housemaid about it. But she had already begun to like this odd little girl who had such an intelligent small face and such perfect manners. She had taken care of children before who were not so polite. Sara was a very fine little person, and had a gentle, appreciative way of saying, "If you please, Mariette," "Thank you, Mariette," which was very charming. Mariette told the head housemaid that she thanked her as if she was thanking a lady.

"Elle a l'air d'une princesse, cette petite," she said. Indeed, she was very much pleased with her new little mistress and liked her place greatly.”

What prompted me to do this reread was critics calling Sara an “idealized child figure” and people on Goodreads calling her a Mary Sue. It is true that Sara has a unique beauty, is very intelligent and very rich. But she is also consistently described as “odd”, “queer”. While she is “special”, she doesn’t act or think like children are expected to. Even her make-believe has a seriousness and conviction to it, she is very self-conscious and self-aware about her pretense that Emily is a real child and tries to convince herself of the validity of it, and she acts more like an author of fiction rather than a typical child playing with her doll. She doesn’t really like others’ company. She is clearly distinct from cheerful and friendly characters like Heidi, Pollyanna or Anne Shirley (though Anne is also imaginative).

Sara’s odd traits are endearing to others because of her class status and her intelligence. Her pretentiousness, daydreaming and excessive politeness are endearing traits for Mariette in a child that she is supposed to serve. And they are tolerated in a child that others are predisposed to want to be friends with because of her riches. Sara’s uniqueness makes her look like a little princess in her frilly dresses, if she were born poor and less intelligent she would be stigmatized for these weird traits, and she wouldn’t be raised to be so polite to stop herself from saying something wrong. In effect Sara’s story is about a weird and intelligent child whose “weirdness” is tolerated and even admired because of her class privilege and of what happens when that privilege is taken away from her.

- “"As your papa has engaged a French maid for you," she began, "I conclude that he wishes you to make a special study of the French language."

Sara felt a little awkward.

"I think he engaged her," she said, "because he—he thought I would like her, Miss Minchin."

"I am afraid," said Miss Minchin, with a slightly sour smile, "that you have been a very spoiled little girl and always imagine that things are done because you like them. My impression is that your papa wished you to learn French."

If Sara had been older or less punctilious about being quite polite to people, she could have explained herself in a very few words. But, as it was, she felt a flush rising on her cheeks. Miss Minchin was a very severe and imposing person, and she seemed so absolutely sure that Sara knew nothing whatever of French that she felt as if it would be almost rude to correct her. The truth was that Sara could not remember the time when she had not seemed to know French. Her father had often spoken it to her when she had been a baby. Her mother had been a French woman, and Captain Crewe had loved her language, so it happened that Sara had always heard and been familiar with it.

One of Miss Minchin's chief secret annoyances was that she did not speak French herself, and was desirous of concealing the irritating fact. She, therefore, had no intention of discussing the matter and laying herself open to innocent questioning by a new little pupil.

"That is enough," she said with polite tartness. "If you have not learned, you must begin at once. The French master, Monsieur Dufarge, will be here in a few minutes. Take this book and look at it until he arrives."”

Writers like Roald Dahl and even Lemony Snicket are sometimes rightfully praised for depicting the way adults oppress children as a class of people unlike the more idealistic depictions in classic children’s books. But this passage of A Little Princess is such a realistic depiction of the way adults talk over children and don’t listen to them. It also reminded me of an Iranian film I have recently watched called Where Is the Friend’s House? where a small child couldn’t even ask the most basic of questions to adults. Adults are so loud and they can’t hear you when you are seven.

Sara’s mother is French. I think she is white and her relatively exotic looks are caused by her mother being “Mediterranean”. I think it wasn’t uncommon for multiracial Anglo-Indians to assert that they were partially of “Latin” origin to explain their looks; I have once watched a video where a girl learned that her Portuguese grandmother from India was actually Indian all along via DNA test. But I don’t really think that it is the case here, though it can certainly be interpreted that way.

“”Sara's cheeks felt warm. She went back to her seat and opened the book. She looked at the first page with a grave face. She knew it would be rude to smile, and she was very determined not to be rude. But it was very odd to find herself expected to study a page which told her that "le pere" meant "the father," and "la mere" meant "the mother."”

Sara is undoubtedly a very polite and nice child. But I like the way her politeness isn’t presented as simply an inherent, natural trait but as something that she actively tries to embody. This is what makes her distinct from a simple idealized child figure, you see her actively trying to be (and sometimes struggling to be) what she is.

- “Miss Minchin glanced toward her scrutinizingly.

"You look rather cross, Sara," she said. "I am sorry you do not like the idea of learning French."

"I am very fond of it," answered Sara, thinking she would try again; "but—"

"You must not say 'but' when you are told to do things," said Miss Minchin. "Look at your book again."

And Sara did so, and did not smile, even when she found that "le fils" meant "the son," and "le frere" meant "the brother."”

Everyone who remembers their childhood can remember the frustration Sara feels here when adults simply do not let her speak and talk over her. “Adultsplaining” much (I am really sorry for coining this word)?

- “Monsieur Dufarge began to smile, and his smile was one of great pleasure. To hear this pretty childish voice speaking his own language so simply and charmingly made him feel almost as if he were in his native land—which in dark, foggy days in London sometimes seemed worlds away.”

Burnett was multinational, which means that the book lacks the jingoistic and xenophobic tone that can be present in other classic British children’s books. She has been dunking on the foggy weather of London for two chapters in a row now. This does not excuse the way she depicts colonialism and the Indian characters, but it is still worth noting.

“Miss Minchin knew she had tried, and that it had not been her fault that she was not allowed to explain. And when she saw that the pupils had been listening and that Lavinia and Jessie were giggling behind their French grammars, she felt infuriated.

"Silence, young ladies!" she said severely, rapping upon the desk. "Silence at once!"

And she began from that minute to feel rather a grudge against her show pupil.”

I wish I could say that an adult teacher getting angry at and harboring a grudge against a child because of her knowing more than herself and making her look wrong for a minute is unrealistic, but I can confidently assert based on personal experience that it is unfortunately wholly realistic.

Sara’s perfect French can be read as another “special” trait that makes her unduly idealized. But she knows it because she has been hearing it since her birth, not because she is a genius.

Sara’s knowledge of French and her slightly pretentious nature come to have consequences for her, as the last line of the chapter foreshadows. As I have said, Sara’s knowledge and her “annoying” traits are tolerated by Minchin because she is so rich, when she loses her privilege they will become a motivation for her to abuse her. Despite its romanticization of wealth, A Little Princess does a good job in showing how the same traits can be regarded differently based on your class privilege.

I am really enjoying this reread. The book is still very good and fun to read.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is a really dumb but adorable realization but:

A Little Princess by Francis Hodgson Burnett was first published as a book in 1905. It is an expanded version of the short story "Sara Crewe: or, What Happened at Miss Minchin's", which was serialized in St. Nicholas Magazine from December 1887, & published in book form in 1888.

which means Lucie Herondale would have likely read it & that’s entirely precious to me.

#chain of gold#tlh#→ the shadowhunter chronicles // fandom#James is over here#just doting on his sister#what a dumbass#I love him#also I love that book#way too much

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Don’t be impudent, or you will be punished,” she said. “You will have to improve your manners if you expect to earn your bread. You are not a parlor boarder now. Remember that if you don’t please me, and I send you away, you have no home but the street. You can go now.”

Sara turned away.

“Stay,” commanded Miss Minchin, “don’t you intend to thank me?”

Sara turned toward her. The nervous twitch was to be seen again in her face, and she seemed to be trying to control it.

“What for?” she said.

“For my kindness to you,” replied Miss Minchin. “For my kindness in giving you a home.”

Sara went two or three steps nearer to her. Her thin little chest was heaving up and down, and she spoke in a strange, unchildish voice.

“You are not kind,” she said. “You are not kind.” And she turned again and went out of the room, leaving Miss Minchin staring after her strange, small figure in stony anger.

- Sara Crewe, or What Happened at Miss Minchin’s, pg. 12- 13, from the 1903 publication of “Sara Crewe, Saint Elizabeth and Other Stories” by Frances Hodgeson Burnett

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Princess

Fiksi anak klasik ini ditulis oleh seorang wanita berkebangsaan Inggris, Frances Eliza Hodgson Burnett. Mengisahkan tentang seorang anak perempuan kecil bernama Sara Crew. Sara memang masih sangat muda dalam hal usia, namun bisa dikatakan dia dewasa secara mental.

Cerita ini pertama kali diterbitkan sebagai sebuah buku pada tahun 1905. Sebelumnya kisah ini merupakan cerita pendek yang terbit di majalah anak St. Nicholas, judulnya "What Happened at Miss Minchin's"

Seorang Anak Perempuan Kecil

Sara Crew, hidupnya nyaris sempurna. Ayahnya yang seorang pegusaha kaya raya, dan begitu menyayangi putri tunggalnya.

Sara dan Ayahnya berangkat dari India menuju London untuk belajar di sebuah asrama khusus perempuan yang tentu saja bergengsi disana.

Sayangnya semua kebahagiaan itu pada suatu waktu berbalik 180 derajat karena Ayahnya yang tiba-tiba dikabarkan telah tiada. Sara sendiri tanpa seorangpun kerabat, bahkan ayahnya tidak meninggalkan apapun untuknya.

Cara Sang Putri Cilik Menghadapi Masalah

Saat ayahnya tiada, itulah awal dari berbagai macam masalah yang menuntut Sara untuk benar-benar tegar sekaligus menguji kesabarannya.

Begitu mengagumkan bagaimana Sara mengendalikan dirinya di tengah banyak hal -atau masalah- yang kebanyakan orang pasti sudah tidak sabar menghadapinya. Entah marah, terpuruk, memberontak, bahkan sekedar bermuka masam.

Seorang anak perempuan kecil yang berusaha tegar & positif dengan cara yang tidak biasa. Bisa dibilang cara yang unik untuk menghadapi masalah.

Salah satu kutipan favorit saya di buku ini:

(...) Secara mental, Sara seperti menjalani kehidupan di mana kedudukannya lebih tinggi daripada orang-orang lainnya. Sara nyaris tidak mendengar hal-hal kasar dan masam yang dilontarkan kepadanya; atau, seandainya mendengarkan ia tidak peduli sama sekali (...) - hal. 175

Kalau kamu senang dengan bacaan yang lumayan ringan & bisa memberimu pelajaran berharga, buku ini layak dibaca. Saya selalu penasaran tentang bagaimana selanjutnya Sara akan bereaksi.

// Jakarta, 11 September 2020 | ©renabooks.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

Day 123/365 - A Little Princess

By Andrew Lippa and Brian Crawley

Sara Crewe is in trouble from the outset. She has been sent to her room without supper for coming to the table barefoot. Becky, a young maid about the same age, smuggles a muffin upstairs to Sara, and peppers her with questions about what life was like in India

Everyone else at the London school has been stand-offish, so Sara is glad to answer the questions, and invites Becky to picture the send-off she received from her friends in Fort St. Louis in (Good Luck, Bonne Chance). After the townspeople wish her the best, Sara's father, Captain Crewe, bids her a private farewell. He reveals he must send her to London as he is embarking upon a mission of exploration to the forbidden city of Timbuktu. He promises, once the Saharan trek is over, he will return to London to fetch her home (Soon, My Love). Sara and Becky's reverie is over when Miss Winifred Minchin surprises the two girls. Servants and schoolgirls are not meant to mix; Minchin asks Becky to fetch her cane. Sara protests that her father's instructions were that she was not to be corporally punished. Miss Minchin replies she is aware of the instructions, and will beat Becky in Sara's stead. Between the bare feet and illicit camaraderie, Minchin is convinced Sara has no idea how to behave in a civilized fashion. She therefore forbids Sara to speak to anyone without permission. Once the monstrous headmistress leaves, Sara vents her frustration (Live Out Loud).

The next day the other schoolgirls corner Becky and demand to know everything she learned about Sara. The girls are envious of Sara's wealth, and her privileges - she's out riding a pony while the rest take their exercise in a courtyard - but curious as well. Lavinia, the oldest and meanest of the girls, threatens to harm Becky just as Sara returns from her ride. Lavinia backs down when she sees Sara's riding crop. She continues, though, to tease Becky, joking about the accident that left Becky an orphan.

To comfort Becky, Sara confides her own mother is deceased. She offers to help Becky get in touch with her mother's spirit. Miss Amelia, Miss Minchin's sister, can't resist this idea. Sara begins to tell the girls how to contact spirits. Her tales are so vivid they seem to come to life. Soon the schoolgirls are joined by imagined Indians in a joyous dance; a spirit enjoins Becky to let her heart be her compass (Let Your Heart Be Your Compass). It is Sara's first success with the other schoolgirls. But it is short-lived. During the dance Lavinia leaves to fetch Miss Minchin, who arrives furious. As part of Sara's punishment, Minchin tears a letter from Captain Crewe into pieces. She also sends Becky to the workhouse. Whilst this is happening, a schoolgirl named Ermengarde picks up the pieces of Sara's letter.

In Africa, Captain Crewe is met with one setback after another. His retinue dies off; his trade goods are stolen; he is detained by a tribal leader with deep suspicions as to an Englishman's reasons for being there. Feverish, despairing, Crewe imagines how happy his daughter must be in London (Isn't That Always the Way).

Sara's defense of Becky has won her two new confidantes: Ermengarde, who has pieced together Crewe's letter for Sara, and Lottie, the youngest of the schoolgirls, who is intrigued by the doll Sara brought by her father, it was made in France and a gift upon his departure from her. Ermengarde reads the letter to Sara and they all imagine what her father is doing over in Africa (The Widow Zuma). Sara enlists Ermengarde and Lottie's help to create such chaos at school that Becky is recalled from the workhouse, and restored to her position. Miss Minchin, realizing she has been outmaneuvered, believes all Sara's advantages come to her because she has been born lucky (Lucky).

Meanwhile, in Sara's room, Ermengarde and Lottie apologize to Becky for their past transgressions against her, and promise to be her friends in future, just as Sara is. Becky is cowed at first. Sara assures her that wealth and position are mere 'accidents of birth'; Becky is willing to agree that even if it were the other way around, she and Sara would have wound up friends (The Tables Were Turned). Time passes and Sara's birthday arrives. Miss Minchin is a bit more disposed to be kind to the girl; rumors have reached London that Captain Crewe made it to Timbuktu. Minchin has made a small fortune on the resultant stock market speculation. Sara's classmates are fascinated by a large box from the London docks. It turns out to be full of presents Sara has ordered for the other girls.

There is no time to enjoy them. A barrister brings news that not only did Crewe never make it to Timbuktu, he died in disgrace. At a stroke Sara is left a penniless orphan, and Miss Minchin's own fortune disappears. She decides, rather than put Sara out on the street, to make her a serving girl, sell all her things, and house her in a dark attic room. Sara does not believe what she has been told, and is determined to find out the truth (Soldier On).

Lottie visits Sara in her new room just before the Christmas holiday. She is shocked by the drab, cold attic. Sara comforts her by describing it as a new, exciting place full of unexpected magic (Another World), though once Lottie leaves the depressing reality of it returns.

Downstairs the schoolgirls are dressed in their best, ready for a holiday. It is almost Christmas (Almost Christmas), and all they can think of are the presents awaiting them at home. Sara is sent out on a cold Christmas Eve to buy a goose for Miss Minchin. She hurries past the happy last-minute shoppers, wondering where her father might be. She imagines she hears Pasko, a friend from St. Louis.

That she does find a goose, and at the last minute, is quite impressive to Miss Amelia. She suggests sharing the holiday meal with Sara, who angers Miss Minchin. Miss Amelia resolves to leave the school and find a way to have Sara released; she tells the child how she and her sister once played at being virtuous little princesses too (Once Upon A Time). Miss Amelia leaves. Miss Minchin sends Sara to her room, but mourns her hollow victory over the girl (Lucky Reprise). She locks Sara and Becky in the attic for the night.

Sara is disconsolate. Becky tries to use Sara's doll to invoke the magic of the imagination, to comfort Sara the way she has been comforted herself; nothing happens. Sara goes to sleep while Becky mourns the powerlessness of the broken doll (Broken Old Doll).

The two girls sleep. Pasko sneaks in through the window, bringing food, fire-wood and blankets to the girls. While he does so Sara and Becky dream of fantasy Indians bearing more exotic objects and luxuries, and of Captain Crewe becoming a hero by reaching his destination (Timbuktu). Becky and Sara awake from the dream smelling the breakfast Pasko has left them. They are startled to see him. As Miss Minchin comes up to check on the girls,. Sara grabs a plank and puts it on between hers and the neighbours home escaping the police which have been called to come get her for stealing back her locket. Becky, afraid of heights, stays behind, but promises to meet them later. The girls have heard of Sara's escape and gossip downstairs (Gossip).

Miss Minchin seizes Becky and determines to have she and Sara arrested. Sara arrives with the highest authority in the land, Queen Victoria, whom she has waylaid and regaled with stories of the cruel headmistress. It is Minchin who is arrested. Victoria acknowledges, just before Sara returns to Africa, that anyone can be a princess, if their hearts are open and their actions true (Finale).

It’s a bit long-winded but I like the morals of the story.

Favourite Songs: Soon My Love, Live Out Loud, Let Your Heart Be Your Compass, Lucky, If The Tables We’re Turned, Almost Christmas, Once Upon A Time and Finale.

Favourite Character: Sara

She’s super determined, humble and caring. She definitely knows her worth and wants to play a part in helping other recognise their worth too.

#andrew lippa#brian crawley#a little princess#ayearofmusicals#a year of musicals#music criticism#musical theatre#musical#musicals

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Princess - Putri Raja Cilik

Novel anak klasik ini ditulis oleh seorang wanita berkebangsaan Inggris, Frances Eliza Hodgson Burnett. Mengisahkan tentang seorang anak perempuan cilik bernama Sara Crew. Anak kecil yang dewasa.

Cerita ini pertama kali diterbitkan sebagai sebuah buku pada tahun 1905. Sebelumnya kisah ini merupakan cerita pendek yang terbit di majalah anak St. Nicholas, judulnya "What Happened at Miss Minchin's"

Seorang Anak Perempuan Kecil

Sara Crew, hidupnya nyaris sempurna karena Ayahnya yang kaya & menyayanginya. Berangkat dari India, dia disekolahkan di asrama khusus perempuan bergengsi di London.

Pada suatu waktu, Ayahnya harus pergi meninggalkannya untuk selamanya. Sara sendiri tanpa spenser pun warisan ditinggalkan.

Cara Unik Menghadapi Masalah

Begitu mengagumkan bagaimana Sara kecil mengendalikan dirinya di tengah banyak hal -atau masalah- yang kebanyakan orang pasti sudah tidak sabar menghadapinya. Entah marah, terpuruk, memberontak, bahkan sekedar bermuka masam.

Seorang anak perempuan kecil yang berusaha tegar & positif dengan cara yang tidak biasa. Bisa dibilang cara yang unik untuk menghadapi masalah.

Jika ada kata-kata yang bisa menggambarkan bagaimana buku ini memberi pelajaran dan bagaimana sosok si kecil Sara. Kurang lebih seperti ini:

Siapapun/apapun bisa saja berusaha menjatuhkanmu, namun dirimu yang memilih untuk jatuh atau tetap terus berjalan dengan tegak.

Salah satu kutipan favorit saya di buku ini:

(...) Secara mental, Sara seperti menjalani kehidupan di mana kedudukannya lebih tinggi daripada orang-orang lainnya. Sara nyaris tidak mendengar hal-hal kasar dan masam yang dilontarkan kepadanya; atau, seandainya mendengarkan ia tidak peduli sama sekali (...) - hal. 175

Kalau kamu senang dengan bacaan ringan yang seru & bisa memberimu pelajaran berharga, buku ini layak dibaca. Saya selalu penasaran tentang bagaimana selanjutnya Sara akan bereaksi.

Saya tidak akan menulis rating. Misalkan rating saya untuk buku ini adalah 3,5/5. Bagi saya 3,5 adalah angka yang cukup besar & masuk kategori buku yang bagus.

Namun, pembaca tulisan ini mungkin akan menilai 3,5/5 itu angka yang kecil sehingga urung untuk membacanya.

// Jakarta, 11 September 2020 | ©bukkuku.tumblr.com

0 notes

Photo

Just Pinned to Vintage Books at Seaside Collectibles: Antique Vintage Retro for You! on Instagram: “Sara Crewe or What Happened at Miss Minchin's by Frances Hodgson Burnett Illustrated by Margot Tomes. CATALOG INFO: G.P Putnam…” https://ift.tt/2odSCGZ

0 notes

Photo

“The monkey seemed much interested in her remarks.” From Sara Crewe or What Happened at Miss Minchin’s by Frances Hodgson Burnett, 1918.

Here’s my collection of the most interesting vintage primates I’ve encountered through the course of my research.

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

it's "the secret garden" anon! i read the tags on your latest post and now i'm super curious about the other versions of "a little princess" where sara had more pronounced flaws! would you mind elaborating? :)

Hi, Secret Garden anon!

I’m going to do a post about that very thing in the near future; it’s just going to take a while to put together because DETAILS!

The earliest version of the story was a short story called Sara Crewe, Or, What Happened at Miss Minchin’s (serialized 1887, published 1888). Then Burnett expanded it into a play called A Little Un-fairy Princess (later The Little Princess) in 1902, which was further expanded into the novel A Little Princess.

Stay tuned, and I will get back to you on this!

EDIT: There are also some minor textual variants in the serialized version of The Secret Garden (most notably Mary’s continuing to wear black after coming to Misselthwaite) that I’d like to talk about at some point.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Princess ★8.6/10

『小公女』(しょうこうじょ、A Little Princess)は、アメリカの小説家フランシス・ホジソン・バーネットによる、児童文学作品の一つ。

雑誌「セントニコラス」に連載された。連載終了後、1888年に "Sara Crewe, or What Happened at Miss Minchin's"(セーラ・クルー、またはミンチン学院で何が起きたか)という題で発表されたが、舞台化の成功と読者からの投書に応じて大幅加筆された再版分(1905年)からは "A Little Princess" の題名で発行されている。

舞台は19世紀のイギリス。セーラ・クルーは、英領であったインドで資産家の父ラルフ・クルーとともに暮らしていたが、7歳の頃、父の故郷イギリスのロンドンにあるミンチン女子学院に入学する(当時、インドに住むイギリス国籍の子供は、その年頃になると勉学の為に帰国。寄宿舎に入る習わしがあった)。父の要望もあり、特別寄宿生となったセーラだが、境遇を鼻に掛ける事もなく聡明で心優しい性格で、たちまち人気者になる。

10歳の頃、父はインドで友人であるクリスフォードとともにダイヤモンド鉱山の事業を開始。学院の経営者であるマリア・ミンチン院長は、多額の寄付金を目当てにセーラの11歳の誕生日を盛大に祝う事を計画する。

しかし、誕生祝いの最中に父親の訃報と事業破綻の知らせが届く。ミンチン院長は、それまでの出資金、学費などを回収出来なくなったとし、セーラの持ち物を差し押さえた上で、屋根裏部屋住まいの使用人として働くように命じ、セーラの生活は一変した。突如訪れた不幸と、不慣れな貧しい暮らしの中でも“公女様(プリンセス)のつもり”で、気高さと優しさを失わずに日々を過ごすセーラ。wiki

0 notes

Text

I’m trying to write these notes up into a proper review

#wish me luck#it was over three months ago#but I still have Thoughts#and Feelings#A Little Princess#A Little Princes the musical#fanciful AU fanfic#written by committee#and set to music#by#Andrew Lippa#Amanda Abbington#was remarkable in it#she did an amazing job#with what she was given

0 notes

Text

i would really love to see a version of a little princess that combines the original version (Sara crew or what happened at miss minchins) and the revised book. They have really different themes despite being the same story, and the revised version is admittedly a lot more polished and fleshed out in certain areas (mr carrisford and the large family having scenes interspersed as soon as they’re relevant) but I do like beta sara.

i can see though how revised sara stays true to her sense of politeness, beta version sara is quite blunt and it is the mistreatment she suffers from others that make her brush up the way she speaks and value her words effects on others. She is much more solitary, being totally ignored by the pupils and without Becky or even Ermendgarde for a majority of the novel.

There isn’t any birthday party in the beta novel, so it really puts a different lens over miss minchins mistreatment of sara having absolutely no justification (debt is the reason in the revised version. Beta version is just cause I guess). i love how beta version sara speaks hindustani to beta version ram dass, and its amazing she can speak 4 languages including German— which is only implied in the revised novel.

They’re both great. I like them both. For the beta version there are lots of exposition near the end, but the way the Magic blindsides u and Sara alike was really great. The revised version foreshadows the entire thing repeatedly before it happens.

Also Mr Carrisfords neuroticism was a lot more apparent in What Happened than A Little Princess. But I prefer the opening chapters ofthe revised version for simply for the way the sentences flow.

I read the beta version for the first time after having read/heard the revised version nearly twenty times so it was interesting to see new bits in the story :)c

#a little princess#sara crewe#sara crewe or what happened at miss minchins#frances hodgson burnett#no really im nearing twenty time of reading or hearing this book#around 17 or 18 rn tho

1 note

·

View note