#The Medium Margery

Text

Dec 19-22nd 2019, available for showcase-production? What did they actually discover about the Afterlife? Based on their correspondence, chasing seances where they might find genuine mediums. In the Afterlife, they replay the events ad-infintum. Until the wives push through the ETHER for a final resolution. Interested? Props, puppets, Q-lab files of special effects real and imagined.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started a book on a ‘real’ haunting recced by a friend but in the prologue the writer comes off as a willfully delusion pollyanna and in the second chapter a researcher is referenced who I KNOW is a bitch bc he was colluding AND carrying on with the fake medium (redundant) Margery Crandon. And how do I know he’s a bitch? HARRY FUCKING HOUDINI AND KENNETH SILVERMAN TOLD ME SO, CRANDON ADMITTED THEIR COLLUSION AT THE END OF HER LIFE

#dying screaming gnashing my teeth#the haunting of alma fielding#if you like this book do not fuck with me i have no patience for woowoo spiwitualism#i fucking grew up in a haunted house so when i say a ghost hunter is a bitch i fucking mean it!!!!#pseudoscientific horseshit!!!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

November Reading

Asadov, Farda. "Trade Routes, Trading Centers and the Emergence of the Domestic Market in Azerbaijan in the Period of Arab-Khazar Domination on the Silk Road." Acta Via Serica 4, no. 1 (2019): 1-24.

Beckemeyer, R. (2000). RJ Tillyard and the medium Margery: dragonflies and séances. Argia, 12(2), 11-13.

Breasted, James Henry. "The earliest boats on the Nile." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 4, no. 1 (1917): 174-176.

Brenard, Robert. "The romance of the air mail to East and South Africa." Journal of the Royal African Society 38, no. 150 (1939): 47-64.

Burns, Mary Ann T. "Pliny's ideal Roman." Classical Journal (1964): 253-258.

Caulk, Richard. "Bad men of the Borders: shum and shefta in Northern Ethiopia in the 19th century." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 17, no. 2 (1984): 201-227.

Dierikx, Marc LJ. "Struggle for Prominence: Clashing Dutch and British Interests on the Colonial Air Routes, 1918—42." Journal of Contemporary History 26, no. 2 (1991): 333-351.

Edgar, Adrienne. "Bolshevism, patriarchy, and the nation: The Soviet “emancipation” of Muslim women in Pan-Islamic perspective." Slavic Review 65, no. 2 (2006): 252-272.

Edwards, David N., Ali Osman, Yahia Fadl Tahir, Azhari Mustafa Sadig, and Intisar Soghayroun el-Zein. "On a Nubian frontier—landscapes of settlement on the Third Cataract of the Nile, Sudan." Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 47, no. 4 (2012): 450-487.

Garretson, Peter P. "Frontier Feudalism in Northwest Ethiopia: Shaykh al-Imam'Abd Allah of Nuqara, 1901-1923." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 15, no. 2 (1982): 261-282.

Goody, Jack. "The political systems of the Tallensi and their neighbours 1888–1915." Cambridge anthropology (1990): 1-25.

Gordon, Eleanora C. "The fate of Sir Hugh Willoughby and his companions: A new conjecture." Geographical Journal (1986): 243-247.

Gradskova, Yulia. "Opening the (Muslim) woman’s space—The Soviet politics of emancipation in the 1920s–1930s." Ethnicities 20, no. 4 (2020): 667-684.

Isitt, Guy F. "Vikings in the Persian Gulf." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 17, no. 4 (2007): 389-406.

Kritsky, Gene R. "An Unusual Method of Insect De-Extinction." American Entomologist 61, no. 2 (2015): 66.

Mather, Charles. "Shrines and the domestication of landscape." Journal of Anthropological Research 59, no. 1 (2003): 23-45.

Paviot, Jacques. "England and the Mongols (c. 1260–1330)⋆." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 10, no. 3 (2000): 305-318.

Pirie, Gordon. "Incidental tourism: British Imperial air travel in the 1930s." Journal of Tourism History 1, no. 1 (2009): 49-66.

Seri-Hersch, Iris. "" Transborder" Exchanges of People, Things, and Representations: Revisiting the Conflict Between Mahdist Sudan and Christian Ethiopia, 1885–1889." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 43, no. 1 (2010): 1-26.

0 notes

Text

on cycles

a syllabus of orbits, loops, repetitions, and returns

loops, the limits of language, the paradoxical loneliness of "i love you," and what keeps love alive by maria popova

an installment of popova's newsletter the marganialian that draws on the writing of roland barthes. popova begins by describing her repeated daily walking routes, drawing a connection between the repetition of movement and the repetition of speech and feeling-- the recurrent declaration of "i love you."

why did our universe begin? with roger penrose

video with nobel prizewinning physicist roger penrose that explains his theory of "conformal cyclic cosmology": that our universe's deep past bears a similarity to its deep future, giving evidence for an infinitely cycling timeline. see the essay "time after time" by paul halpern for more on physics and cyclical time.

"time, space, and the eclipse of the earth" (part i: abstraction) by david abram

from ecologist and philosopher david abram's book the spell of the sensuous. in this section, he distinguishes broadly between how space and time are viewed in oral cultures and literate cultures. he focuses on the alignment between oral cultures and a cyclical model of time, discussing why alphabets and writing might affect the way space-time manifests in a cultural imagination.

the hero with a thousand faces by joseph campbell

book by mythologist and literature professor joseph campbell describing his archetypical "hero's journey" cycle, a basic multi-step plot shared by myths and stories across many centuries and cultures (also called a "monomyth"). for a condensed version of the hero's journey, see this diagram by lisa paltz spindler designed for the gunn center for the study of science fiction.

"on small seasons and long calendars" by ross zurowski

essay by designer ross zurowski on how we divide and mark time, arguing that we should begin to divide our lives into more organic and useful phases. the essay is inspired in part by the sekki, short descriptive seasons used by farmers in ancient china and japan-- you can see a list of sekki (along with twitter and ical notifications) at zurowski's a guide to understanding small seasons.

wintering by katherine may

book by british writer katherine may on literal and metaphorical winters. may writes about the necessity to periodically experience darkness throughout life, meditating on the winter solstice, cold water swimming, the northern lights, hibernation and fairy tales to illustrate how wintering can catalyze self-renewal.

"ouroboricisms" by alice lesperance

medium essay about trauma that uses the ouroboros as a metaphor for the circular reconstruction of memory. lesperance draws from mystics and writers julian of norwich, anne carson, margery kempe, and flannery o'connor and their engagement with the repetition and recreation of wounds.

"on reset" by brian blanchfield

a meditation by poet brian blanchfield from his essay collection proxies about discovering a series of audition tapes in which the same scene is repeatedly recast with different actresses. he draws a comparison between the audition scene and poetic repetition, not only in the structure of poems but in our engagement with poetry itself.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

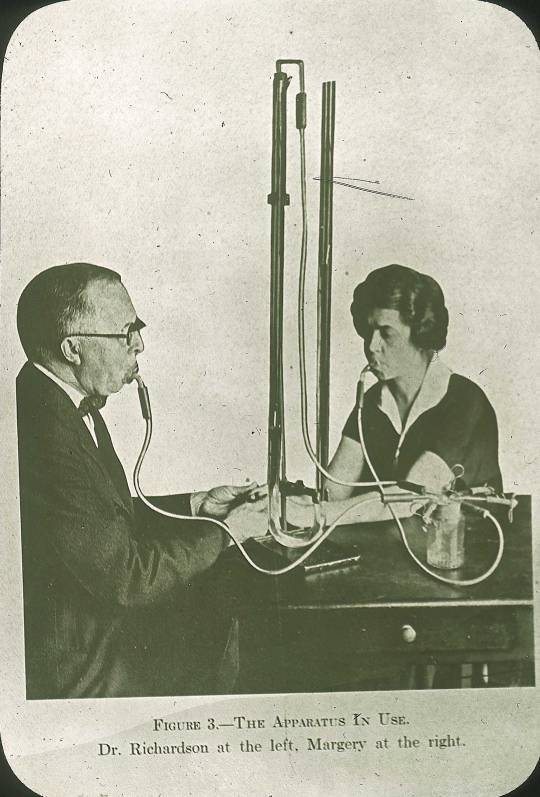

The Voice-Cut-Out Machine

A glass lantern slide of Dr. Richardson speaking to Margery through a voice-cut-out machine, which the medium, Margery, used to speak with the spirit, Walter. Thomas Glendenning Hamilton verified this process in 1925.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ectoplasm mirrors the unstable era in which it emerged. But ectoplasm also, by its very elusive and indefinable nature, allowed female mediums of the period to redefine themselves and also to expose the limits of positivist and psychical knowledge. While we, unfortunately, have no way of knowing what motivated these mediums, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that their ectoplasmic protuberances materialized as a means of prodding back at their examiners and at the boundaries of polite society. Palladino’s séance room performances allowed her both social and sexual mobility while the cross-class collaboration between Eva C. and Juliette Bisson helped the women not only to defy Schrenck-Notzing’s clinical authority but also to achieve recognition among Spiritualists and psychical researchers alike. [...] Margery, like Houdini, took her secrets to the grave. While she was on her death bed, Nandor Fodor, who had been a friend of the medium, asked Mina how she produced the phenomena that she did. Mina responded somewhat warily, “all you ‘psychical researchers’ can go to hell” then playfully added “why don’t you guess? You’ll all be guessing…for the rest of your lives” (Margery 184-85).

— Anne L. Delgado, Bawdy Technologies and the Birth of Ectoplasm, 2011.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Garment Analysis – 80s women’s wear: Power Dressing

The 80s was a time of Capitalism as the stock market was at a peak. More women than ever before found themselves in higher positions of power in the workplace. Women were no longer just secretaries. They were managers, directors, and executives. In 1983 women filled 39% of financial and banking management roles, a dramatic increase, compared to 20 years prior when women only filled 9%. (Guilder, 1986) (Hacker, 1984).

The change of demographic of the executive workforce led to a new fashion trend known as ‘Power Dressing’: mainly women wearing the ‘the Power suit’. Worn by professional women, this style of suit has the characteristics being: shoulder pads, large double-breasted collars and a tight sinched waist. The shoulder pads exaggerate the appearance of the shoulders, resembling the silhouette of a man’s figure but waistline remaining feminine. It was still important that women were considered attractive by their male colleagues and women still had to work hard to assert themselves in the workplace. This way of dressing was used to make themselves “publicly visible” and “distinguishable from her secretarial counterparts” (Enwistle 2020).

As seen in figure 1, A medium Grey 2 Piece ‘pant suit’ is seen in figure 1, designed by Calvin Klein for Autumn / Winter his collection. This looks has padded shoulders but has feminine features. For instance, Klein’s suit jacket is cropped so the wearers waistline would be exposed, revealing the feminine body shape. However, there is some debate about whether this suit would be the best option for a woman to be perceived as ‘Powerful’ as according to research for John T Molloy’s ‘Dress for success’ guidebook, grey jackets make a women’s appearance sickly and drained. (Molloy. 1988. P. 37) To stand out in the office more perhaps a better colour would be a bright one.

Margaret Thatcher was a well-known power dresser. An example of an item she wore is an Aquascutum suit (1989) Made in a bright blue, it’s an obvious choice to stand out but also reflects Thatcher’s party – the Conservative party. ( figure 2) This Suit was a staple in thatcher’s wardrobe as she wore it throughout her time in downing street. She wore it when entering the office in 1979 and when she gave her last speech as leader in 1990. (Cruden 2015)

It is clear to see that the power suit was influenced by the military style of the 40s. Designers like Schiaparelli made tailored suits. This was an influence in the effect of the change in gender roles during WW11. This signals that women’s fashion is affected by the change of society just like the 80s.

The large shoulder pads of the 80s may now be considered very dated but we still see the influence from it today. Lady Gaga wore a Marc Jacobs suit with large, padded shoulders in 2018 and claimed that she “wanted to take Power Back” (Hobbs 2020). The power suit may not be commonly seen today but it may be a trend for the future if women decided the want to dress more masculine again.

References

- Cruden, A. 2015. Margery Thatcher’s Aquascutum suit. [Online] ( Accessed 6th Nov 2021] Available from https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5968414

- Enwhistle, J. 2020. Fashion Theory: A Reader. 2nd Edition. Barnard, M. New York: Routledge

- Guilder, G. 1986. Women In The Work Force. The Atlantic. September Issue. [ Accessed 25 October 2021] Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1986/09/women-in-the-work-force/304924/

- Hacker, A. 1984. Women Vs Men In The Work Force. The New York Times Magazine. 9 December, p. 124

- Hobbs, J. 2020. The Evolution of the Power Shoulder. [Online]. [ Accessed 6th Nov 2021] Available from https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5968414

- Reeder, J. 2011. Elsa Schiaparelli (1890–1973. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. [Online] [ Accessed 6th Nov 2021] https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/elsa/hd_elsa.htm

Image reference list:

Figure 1- Klein, C. 1985. Womens Grey jacket. Available from: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/81423.

Figure 2 - AQUASCUTUM 1989. Blue suit worn by Thatcher. Available from: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5968414

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Henry VIII was at Whitehall Palace when the Tower guns signaled that he was once more a free man. He then appeared dressed in white mourning as a token of respect for his late queen, called for his barge, and had himself rowed at full speed to the Strand, where Jane Seymour had also heard the guns. News of Anne Boleyn’s death had been formally conveyed to her by Sir Francis Bryan; it does not seem to have unduly concerned her, for she spent the greater part of the day preparing her wedding clothes, and perhaps reflecting upon the ease with which she had attained her ambition: Anne Boleyn had had to wait seven years for her crown; Jane had waited barely seven months.

It was common knowledge that Henry would marry Jane as soon as possible; the Privy Council had already petitioned him to venture once more into the perilous seas of holy wedlock, and it was a plea of the utmost urgency due to the uncertainty surrounding the succession. Both the King’s daughters had been declared bastards, and his natural son Richmond was obviously dying. A speedy marriage was therefore not only desirable but necessary, and on the day Anne Boleyn died the King’s imminent betrothal to Jane Seymour was announced to a relieved Privy Council. This was news as gratifying to the imperialist party, who had vigorously promoted the match, as it would soon be to the people of England at large, who would welcome the prospect of the imperial alliance with its inevitable benefits to trade.

Although the future Queen had rarely been seen in public, stories of her virtuous behavior during the King’s courtship had been circulated and applauded. Chapuys, more cynical, perceived that such virtue had had an ulterior motive, and privately thought it unlikely that Jane had reached the age of twenty-five without having lost her virginity, ‘being an Englishwoman and having been so long’ at court where immorality was rife. However, he assumed that Jane’s likely lack of a maidenhead would not trouble the King very much, ‘since he may marry her on condition she is a maid, and when he wants a divorce there will be plenty of witnesses ready to testify that she was not’.

This apart, Chapuys and most other people considered Jane to be well endowed with all the qualities then thought becoming in a wife: meekness, docility and quiet dignity. Jane had been well groomed for her role by her family and supporters, and was in any case determined not to follow the example of her predecessor. She intended to use her influence to further the causes she held dear, as Anne Boleyn had, but, being of a less mercurial temperament, she would never use the same tactics.

Jane’s well-publicized sympathy for the late Queen Katherine and the Lady Mary showed her to be compassionate, and made her a popular figure with the common people and most of the courtiers. Overseas, she would be looked upon with favour because she was known to be an orthodox Catholic with no heretical tendencies whatsoever, one who favoured the old ways and who might use her influence to dissuade the King from continuing with his radical religious reforms.

Jane was of medium height, with a pale, nearly white, complexion. ‘Nobody thinks she has much beauty,’ commented Chapuys, and the French ambassador thought her too plain. Holbein’s portrait of Jane, painted in 1536 and now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, bears out these statements, and shows her to have been fair with a large, resolute face, small slanting eyes and a pinched mouth. She wears a sumptuously bejeweled and embroidered gown and head-dress, the latter in the whelk-shell fashion so favoured by her; Holbein himself designed the pendant on her breast, and the lace at her wrists. This portrait was probably by his first royal commission after being appointed the King’s Master Painter in September 1536; a preliminary sketch for it is in the Royal Collection at Windsor, and a studio copy is in the Mauritshuis in The Hague. Holbein executed one other portrait of Jane during her lifetime.

Throughout the winter of 1536-7, he was at work on a huge mural in the Presence Chamber in Whitehall mural no longer exists, having been destroyed when the palace burned down in the late seventeenth century. Fortuitously, Charles II had before then commissioned a Dutch artists, Remigius van Leemput, to make two small copies, now in the Royal Collection and at Petworth House. His style shows little of Holbein’s draughtsmanship, but his pictures at least give us a clear impression of what the original must have looked like. The figure of Jane is interesting in that we can see her long court train with her pet poodle resting on it. Her gown is of cloth of gold damask, lined with ermine, with six ropes of pearls slung across the bodice, and more pearls hanging in a girdle to the floor. Later portraits of Jane, such as those in long-gallery sets and the miniature by Nicholas Hilliard, all derive from this portrait of Holbein’s original likeness now in Vienna, yet they are mostly mechanical in quality and anatomically awkward.

However, it was not Jane’s face that had attracted the King so much as the fact that she was Anne Boleyn’s opposite in every way. Where Anne had been bold and fond of having her own way, Jane showed herself entirely subservient to Henry’s will; where Anne had, in the King’s view been a wanton, Jane had shown herself to be inviolably chaste. And where Anne had been ruthless, he believed Jane to be naturally compassionate. He would be in years to come remember her as the fairest, the most discreet, and the most meritorious of all his wives.

Her contemporaries thought she had a pleasing sprightliness about her. She was pious, but not ostentatiously so. Reginald Pole, soon to be made a cardinal, described her as ‘full of goodness’, although Martin Luther, hearing of her reactionary religious views, feared her as ‘an enemy of the Gospel’. According to Chapuys, she was not clever or witty, but ‘of good understanding’. As queen, she made a point of distancing herself from her inferiors, and could be remote and arrogant, being a stickler for the observance of etiquette at her court. Chapuys feared that, once Jane had had a taste of queenship, she would forget her good intentions towards the Lady Mary, but his fears proved unfounded. Jane remained loyal to her supporters, and to Mary’s cause, and in the months to come would endeavor to heal the rift between the King and his daughter.

- Alison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII

“A story of a later date had Queen Anne finding Mistress Seymour actually sitting on her husband’s lap; ‘betwitting’ the King, Queen Anne blamed her miscarriage upon this unpleasant discovery. There was said to have been ‘much scratching and bye-blows between the queen and her maid’.

Unlike the King’s invocations of the divine will, however, there is no contemporary evidence for such robust incidents; the character of Jane Seymour that emerges in 1536 is on the contrary chaste, verging on the prudish. As we shall see, there is good reason to believe that the King found in this very chastity a source of attraction; as he had once turned to the enchantress Anne Boleyn from the virtuous Catherine. Yet before turning to Jane Seymour’s personal qualities for better or for worse, it is necessary to consider the family from which she came …

The Seymours were a family of respectable and even ancient antecedents in an age when, as has already been stressed, such things were important. Their Norman ancestry – the name was originally St Maur – was somewhat shadowy although a Seigneur Wido de Saint Maur was said to have come over to England with the Conquest. More immediately, from Monmouthshire and Penbow Castle, the Seymours transferred to the west of England in the mid-fourteenth century with the marriage of Sir Roger Seymour to Cecily eventual sole heiress of Lord Beauchamp of Hache. Other key marriages brought the family prosperity. Wolf Hall in Wiltshire, for example (scene of Henry’s autum idyll with Jane if legend is to be believed) came with the marriage of a Seymour to Matilda Esturmy, daughter of the Speaker of Commons, in 1405. Another profitable union, bringing with it mercantile links similar to those of the Boleyns, was that of Isabel, daughter and heiress of Mark William Mayor of Bristol, to a Seymour in 1424.

Sir John Seymour, father of Jane, was born in about 1474 and had been knighted in the field by Henry VII at the battle of Blackheath which ended a rebellion of 1497. From this promising start, he went on to enjoy the royal favour throughout the next reign. Like Sir Thomas Boleyn, he accompanied Henry VIII on his French campaign of 1513, was present at the Field of Cloth of Gold, attended at Canterbury to meet Charles V; by 1532 he had become a Gentleman of the Bedchamber. Locally, again echoing the career of Thomas Boleyn, he had acted as Sheriff of both Wiltshire and Dorset. It was a career that lacked startling distinction – here was no Charles Brandon ending up a duke – but one which brought him close to the monarch throughout his adult life.

Sir John’s reputation was that of a ‘gentle, courteous man’. That again was pleasant but not startling. But there was something outstanding about him, or at least about his immediate family. Sir John himself came of a family of eight children; then his own wife gave birth to ten children – six sons and four daughters. All this was auspicious for his daughter, including the number of males conceived at a time when women’s ‘aptness to procreate children’ in Wolsey’s phrase about Anne Boleyn, was often judged by their family record.

It was however from her mother, Margery Wentworth – once again echoing the pattern of Anne Boleyn – that Jane Seymour derived that qualifying dash of royal blood so important to a woman viewed as possible breeding stock. Margery Wentworth was descended from Edward III, via her great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Mortimer, Lady Hotspur. Indeed, in one sense – that of English royal blood – Jane Seymour was better born than Anne Boleyn, since she descended from Edward III, whereas Anne Boleyn’s more remote descent was from Edward I. This Mortimer connection meant that Jane and Henry VIII were fifth cousins. But of course neither the Wentworths nor the Seymours were as grand as Anne Boleyn’s maternal family, the ducal Howards.

The Seymours may not have been particularly grand, but close connections to the court had made them, by the generation of Jane herself, astute and worldly wise. Sir John Seymour was over sixty at the inception of the King’s romance with his daughter (and would in fact die before the end of the year 1536); even before that the dominant male figure in Jane’s life seems to have been her eldest surviving brother Edward, described by one observer about this time as both ‘young and wise’. Being young, he was ambitious, and being wise, able to keep his own counsel in pursuit of his plans. Contemporaries found him slightly aloof – he lacked the easy charm of his younger brother Thomas p but they did not doubt his intelligence. Edward Seymour was cultivated as well as clever; he was a humanist and also, as it turned out, genuinely interested in the tenets of the reformed religion (unlike his sister Jane) … The vast family of Sir John Seymour began with four boys: John (who died), Edward, Henry and Thomas, born in about 1508. A few years later the King would speak ‘merrily’ of handsome Tom’s proverbial virility. He was confident that a man armed with ‘such lust and youth’ would be able to please a bride ‘well at all points’. Then came Jane, probably born in 1509, the fifth child but the eldest girl. After that followed Elizabeth, Dorothy and Margery; two sons who died in the sweating sickness epidemic of 1528 made up the ten.

Apart from her presumed fertility, what else did Jane Seymour, now in her mid-twenties (the age incidentally at which Anne Boleyn had attracted the King’s attention), have to offer? Polydore Vergil gave the official flattering view when he described her as ‘a woman of the utmost charm both in appearance and character’, and the King’s best friend Sir John Russell called her ‘the fairest of all his wives’ – but this again was likely to loyalty to Jane Seymour’s dynastic significance. From other sources, it seems likely that the charm of her character considerably outweighed the charm of her appearance: Chapuys for example described her as ‘of middle stature and no great beauty’. Her most distinctive aspect was her famously ‘pure white’ complexion. Holbein gives her a long nose, and firm mouth, with the lips slightly compressed, although her face has a pleasing oval shape with the high forehead then admired (enhanced sometimes by discreet plucking of the hairline) and set off by the headdress of the time. Altogether, if Anne Boleyn conveys the fascination of the new, there is a dignified but slightly stolid look to Jane Seymour, appropriately reminiscent of English medieval consorts.

But the predominant impression given by her portrait – at the hands of a master of artistic realism – is of a woman of calm and good sense. And contemporaries all commented on Jane Seymour’s intelligence: in this she was clearly more like her cautious brother Edward than her dashing brother Tom. She was also naturally sweet-natured (no angry words or tantrums here) and virtuous – her virtue was another topic on which there was general agreement.

... Her survival as a lady-in-waiting to two Queens at the Tudor court still with a spotless reputation may indeed be seen as a testament to both Jane Seymour’s salient characteristics – virtue and common good sense . A Bessie Blount or Madge Shelton might fool around, Anne Boleyn might listen or even accede to the seductive wooings of Lord Percy: but Jane Seymour was unquestionably virginal.

In short, Jane Seymour was exactly the kind of female praised by the contemporary handbooks to correct conduct; just as Anne Boleyn had been the sort they warned against. There was certainly no threatening sexuality about her. Nor is it necessary to believe that her ‘virtue’ was in some way hypocritically assumed, in order to intrigue the King (romantic advocates of Anne Boleyn have sometimes taken this line). On the contrary, Jane Seymour was simply fulfilling the expectations for a female of her time and class: it was Anne Boleyn who was – or rather who had been – the fascinating outsider.

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII

“Whilst Jane was always denied a political role, her political interests are clear. She favoured Mary, attempted to save the monasteries and sympathized with the rebels during the Pilgrimages of Grace. Jane’s politics were largely conservative. Her strong character is visible both by her ruthlessness in watching the fall of Anne Boleyn and in the way in which she ruled her household. Jane could have been a queen as strong and influential as Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn had been in the early years of their marriages. Unfortunately for Jane, when the opportunity finally arose with the birth of her son, she did not survive. Had Jane lived, as the mother of the king’s heir, she could have asserted her authority safe in the knowledge that her position was finally secure. After Henry’s death, when Jane’s son was only nine years old, she would have had a very strong claim to the regency as the mother of the king. Jane Seymour could have been so much more and, whilst it is possible to glimpse her potential, much of what she could have achieved will forever be speculation.

Jane did not live to take on the political role that would have been open to her as the mother of the heir to the throne and her real legacy is her son, Edward VI, and the prominence of her brothers, Edward and Thomas Seymour. Although Henry would go on to have another three wives after Jane’s death, Edward was his only son and, on Henry’s death in January 1547, he became king aged nine as Edward VI Edward was hailed by many in England as a future great king and Jane would have been proud of her son. Edward’s tutor, Sir John Cheke, for example, wrote of the king that ‘I prophesy indeed, that, with the lord’s blessing, he will prove such a king, as neither to yield to Josiah in the maintenance of the true religion, nor to Solomon in the management of the state, nor to David in the encouragement of godliness’. Roger Ascham, the tutor of Edward’s sister, Elizabeth, also sang the youth king’s praises, writing that ‘he is wonderfully advanced of his years’. Edward was raised to be a king and received a formidable education, writing very advanced letters even in early childhood (even if is clear that he must have received some assistance in the earlier letters). In one letter to his father, Edward wrote:

In the same manner as, most bounteous king, at the dawn of day, we acknowledge the return of the sun to our world, although by the intervention of obscure clouds, we cannot behold manifestly with our eyes that resplendent orb; in like manner your majesty’s extraordinary and almost incredible goodness so shines and beams forth, that although present I cannot behold it, though before me, with my outward eyes, yet never can it escape from my heart.

Edward was raised to be king in the manner of his father but in his appearance, with his pale skin and fair hair, he always resembled Jane.

Jane’s greatest regret, when she came to realize that she was dying, was that she would not live to see her son grow up …

Jane’s legacy is also her own reputation and her relationship with Henry VIII. Jane never inspired the deep obsession in the king that he felt for Anne Boleyn or the admiring love that he, at first, felt for Catherine of Aragon. Instead, he married her almost on a whim. She was the woman best placed at the perfect time. There is even some evidence that Henry came to regret his haste in marrying Jane after seeing some other beautiful ladies at his court. Jane never raised the passion in Henry that some of his other wives did. Throughout their marriage, it is clear that Henry did not entirely view his marriage to Jane as permanent. It was essential that Jane fulfilled her side of the bargain and that was to bear a son. Until that time, as Jane was very well aware, she was entirely dispensable.

In spite of this, with her death in giving him the son he craved, Henry’s feelings towards Jane entirely changed and he came to look back on their marriage through rose-tinted spectacles. A commemoration to Jane was written some time after her death and perhaps best sums up how Henry came to view her:

Among the rest whose worthie lyves

Hath runne in vertue’s race,

O noble Fame! Persue thy trayne,

And give Queene Jane a place.

A nymphe of chaste Dianae’s trayne,

A virtuous virgin eke; In tender youth a matron’s harte,

With modest mynde most meeke.

Jane spent her entire marriage trying to prove to Henry that she was his ideal woman and, posthumously, she succeeded.

- Elizabeth Norton, Jane Seymour: Henry VIII’s True Love

“How a woman like Jane Seymour became Queen of England is a mystery. In Tudor terms she came from nowhere and was nothing.

Chapuys confronted the riddle in his dispatch of 18 May 1536, which was addressed to Antoine Perrenot, the Emperor’s minister, rather than to the Emperor Charles V himself. Freed from the decorum of writing to his sovereign, the ambassador expressed himself bluntly. ‘She is the sister’, he began, ‘of a certain Edward Seymour, who has been in the service of his Majesty [Charles V]’; while ‘she [herself] was formerly in the service of the good Queen [Catherine]’.

As for her appearance , it was literally colourless. ‘She is of middle height, and nobody thinks she has much beauty. Her complexion is so whitish that she may be called rather pale.’

This is a neat pen-portrait of the woman whose mousy, peaked features and mean, pointed chin, are denred by Holbein with his characteristic, unsparing honesty.

So much Chapuys could see.

But when he turned to her supposed moral character he gave his prejudices full rein. ‘You may imagine’, he wrote Perrenot, man-to-man, ‘whether, being an Englishwoman, and having been so long at Court, she would not hold it a sin to be virgo intacta.’ ‘She is not a woman of great wit,’ he continued. ‘But she may have’ -and here he became frankly coarse- ‘a fine enigme.’

‘Enigme’ means ‘riddle’ or ‘secret’, as in ‘secret place’ or the female genitalia. ‘It is said’, he concluded, ‘that she is rather proud and haughty.’ ‘She seems to bear great goodwill and respect to [Mary]. I am not sure whether later on the honours heaped on her will to make her change her mind.’

Whatever was there here -a woman of no family, no beauty, no talent and perhaps not much reputation (though there is no need to accept all of Chapuys’s slanders)- to attract a man who had already been married to two such extraordinary women as Catherine and Anne?

But maybe Jane’s very ordubarubess was tge oiubt, Anne had been exciting as a mistress. But she was too demanding, too mercurial and tempestuous, to make a good wife. Like the Gospel which she patronised, she seemed to have come ‘not to send peace but the sword’ and to make ‘a man’s foes ... them of his own household’ (Matthew 10.34-6).

Henry was weary of scenes and squabbles, weary too of ruptures with his nearest and dearest and his oldest and closest friends. He wanted his family and friends back. He wanted domestic peace and the quiet life. He also, more disturbingly, wanted submission. For increasing age and the Supremacy’s relentless elevation of the monarchy had made him ever more impatient of contradiction and disagreement. Only obedience, prompt, absolute and unconditional, would do.

And he could have none of this with Anne.

Jane, on the other hand, was everything that Anne was not. She was calm, quiet, soft-spoken (when she spoke at all) and profoundly submissive, at least to Henry ...”

- David Starkey, Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII

Images: Jane Seymour painted by Hans Holbein the Younger. Variousa actresses from costume dramas that have played Henry VIII’s third consort. Elly Condron from the documentary drama Secrets of the Six Wives documentary presented by Lucy Worsley. Anne Stallybras from the BBC miniseries The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1970). Jane Asher from the BBC film Henry VIII & his Six Wives (1972). Lastly, Kate Phillips from Wolf Hall (2014).

#Jane Seymour#Tudor History#dailytudors#historians assesment of Jane Seymour#David Starkey#Alison Weir#Antonia Fraser#Elizabeth Norton

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

I movemout today and my family is getting a new dog tomorrow -.-

#we have a toy poodle named zoomy#and tomorrow they're getting a medium sized pitbull named Margery#which my mom thinks she can change the name is Zabu

1 note

·

View note

Note

Met online asks: the Psmith series, predictably?

I am at long last getting to this! (and what, no, I wasn’t expecting this one at all... :P )

So I think what stymied me here is that... Mike is almost certainly a lurker online. I can imagine Psmith being a Personality easily, but Mike probably spends his time in the internet as inconspicuously as he can. And they need to meet as equals, obviously, so you can’t have just one be Internet Famous at the start...

BUT. Once I started typing, it worked out pretty well!

So here we go:

Mike has Facebook and Twitter and so on, partly for keeping up with IRL connections but mostly to keep up with cricket and his brothers. Tweets almost exclusively about cricket (though also about TV shows he’s currently into), actually has followers who don’t know him IRL because he has Informed Takes

His Twitter account is old enough that it’s not connected to his real name, and he doesn’t identify himself either because he doesn’t like the notoriety of being the Youngest Jackson Brother when he’s not even playing... what do you even call it? Do you call it playing pro cricket, nowadays? You know what I mean. He’s probably still in high school

So yeah his online presence isn’t explicitly connected to the rest of his family’s. His brothers follow him, but they’re not very active on Twitter, and personal communication in the Jackson family is mainly over group text, so the fact that they’re related doesn’t really show

Psmith, meanwhile, has a Twitter account that jumps randomly from topic to topic, depending on whatever the heck he’s thinking about at the moment. It’s constant Psmith Monologuing thrown out into the void, just what the internet was made for

His Twitter display name is Psmith and his handle is something like @ therealpsmith. No one’s sure if it’s supposed to be his last name or if his name is P. Smith or what.

(It feels weird making up Twitter accounts for them in response to an ask from you... but this AU has different goals and so I do need different Twitter presences for them. And I can’t see Mike on Tumblr at all, so that’s not an option)

Since this is an AU, I think they can initially connect over cricket. Psmith follows Mike first, and tends to retweet a fair amount of his cricket takes with his own added commentary. After enough of this (since Mike isn’t so high-profile that he doesn’t notice a new regular interacter) Mike goes and checks out his Twitter

It’s not all cricket and a lot of it is diatribes about whatever’s annoyed Psmith today. But they’re witty and entertaining diatribes, and Mike ends up following him

Before long Psmith starts up a long thread about something Mike’s already been stewing over--a plot development in a TV show they both watch, maybe? Not sure

But anyway Mike starts commenting/retweeting/arguing with other people who disagree, because the thing in question is Stupid and Wrong and the fact that people think otherwise bothers him on a personal level

And then Psmith DMs him like “The cricket connoisseur has come to my aid! I am gratified by your assistance,” and then starts talking to him, personally, about why the thing is Dumb and Wrong

From this they start chatting/interacting more regularly. Mike is, obviously, less loquacious than Psmith, and I don’t think their friendship solidifies quite as quickly as in canon just because they aren’t doing things together, but they still click

At some point Psmith’s bemoaning the fact that he’s so constrained by Twitter’s character limit (unlike Mike, who is “the strong, silent type, admirable suited to the medium”) and starts talking about how to fully express himself he should really have a podcast

Mike: “Why don’t you, then?”

Psmith: “You are right. Why not? Here we see the strength of a true man of action--direct and to the point. Why SHOULDN’T I start a podcast?”

Annnd then he ropes Mike into doing it with him so he’ll have someone to talk to. Mike insists, however, on only using his first name, because he doesn’t want this to reflect badly in his brothers if it goes horribly wrong

So they start a nominally-about-cricket (since that’s their biggest shared thing) podcast, called simply “Mike and Psmith”

(There’s probably a joke somewhere in their eventual fanbase about it being “Mic and Psmith,” since Psmith’s doing 80% of the talking)

Between their dynamic and Psmith’s ability to talk, it’s surprisingly successful--it bounces all over the place, topic-wise, but they’re just fun to listen to

While they’re not, like, Buzzfeed Unsolved levels of well-known, they get a decent-sized fanbase

(There’s a long-running fandom debate over whether Psmith is actually Like That or if the show’s scripted. It will probably never be permanently resolved)

They also start a YouTube channel for playing video games and so on--partly because listeners wanted to see it, but partly because they just like hanging out and doing stuff together

Mike has not told his family about any of this, BTW, because he’s too self-conscious about being mildly internet famous, but one day Margery stumbles across the show. He’s in for a lot of teasing

I honestly don’t know how they meet IRL--I’m torn between A) them just video-chatting eventually, learning each other’s actual names, and meeting up at a cricket match, and B) them meeting coincidentally, in some completely different capacity, and recognizing each other by their voices

Either way, though, once they meet they keeping meeting and eventually end up room/flatmates once they both move away from home (if Mike’s planning to play cricket, would he go to college? Would modern Mike be planning to play cricket for a living? I don’t know these things so I’m leaving that vague)

“Moving in with someone you made friends with online” is not always a recipe for success, but it works out for them. They were already best friends, but now they can actually do stuff together! It really just solidifies their friendship for good

(Not that there isn’t friction--the number of Shenanigans Psmith drags Mike into has vastly increased, for one thing--but it all works out, in the end)

Their podcast is an essential part of their routine, by now. I’m not sure how it develops over the years, but it stays pretty low-key... the core of it is still just two best friends hanging out, and that works

(At some point in the future, the cast may expand to "two best friends and their wives, who are also best friends,” but that’s another story, and one I don’t know well enough to say for sure)

#psmith#mike jackson#isfjmel-phleg#ask games#thank you for this one!#it was fun once i got it going#and there REALLY should be a Part 2 with the girls but i don't know if it'll happen#(if anyone else wants to come up with that one please do!)#there need to be Internet Identity Shenanigans in that of course#too much wodehousian potential there to pass up#(and i almost went there for mike and psmith but i felt it should maybe be saved for psmith and eve)#this had less Emotional Drama than the psych one but i think that fits them okay?#not that i'm OPPOSED to Emotional Drama it just didn't come up the same way#also wasn't expecting them to become podcasters but i enjoy the mental images of that#and psmith needs to use the internet to talk SOMEHOW right#too good a venue to pass up#WAIT 'Nominally About Cricket' is their tagline

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

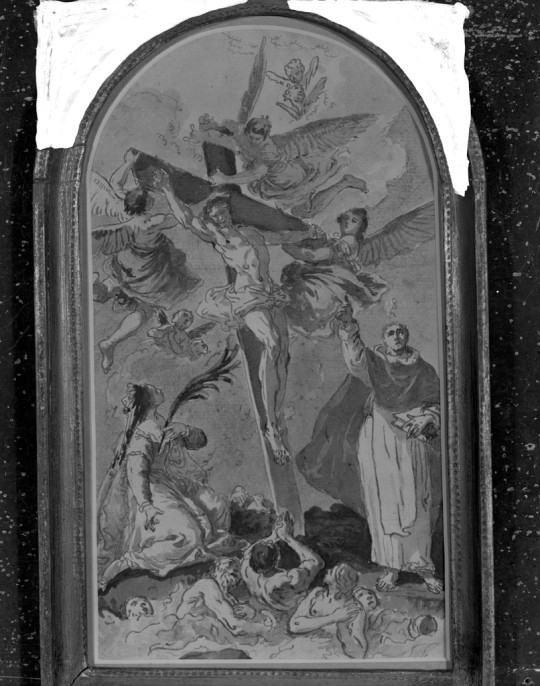

Christ on the Cross with Saints Catherine and Dominic, Francesco Fontebasso, 18th century, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Francis B. Richards in memory of his sister, Margery Richardson

Size: actual: 31.4 x 17 cm (12 3/8 x 6 11/16 in.)

Medium: Brown ink with blue, brown, and pink washes over graphite on off-white antique laid paper

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/296030

1 note

·

View note

Text

Winterfell’s Daughter. On Sansa Stark (part 12)

I’ve previously written a series of posts that analyse Sansa Stark’s narrative arc in Game of Thrones - during season 1 (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6) and during season 2 (Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10) and now season 3 (Part 11). In my previous post I wrote that:

If Sansa’s season 2 arc was about enduring abuse, then her season 3 arc is dealing with hope of an escape - a hope held out by different political players of varying trustworthiness.

However, her season 3 arc is also very much about her political status as Robb Stark’s heir apparent. In short, she has become the Key to the North and as such she’s become an important piece on the political chessboard and to all the major political players in King’s Landing and that is why Petyr Baelish, Lord Varys, Tywin Lannister and the Tyrells begin to take an interest in her. In this post I’m going to take a closer look at her very first interactions with the members of House Tyrell, which is establishing itself as a major power player in the Game of Thrones. Sansa has several interactions with the Tyrells but in this post I’ll limit my analysis to one scene in particular since it is interesting how the Tyrells at first are only interested in Sansa because they’ve heard some disturbing rumours about King Joffrey, Margaery Tyrell’s intended. It is also a scene that I found much more disturbing during my re-watch than when I first watched in years ago.

SECRETS, LIES AND TRUTH - LUNCH WITH THE TYRELLS

In my metas about Margery Tyrell’s season 3 arc (x), I noted that she immediately made her presence felt in King’s Landing through a clever deployment of soft power, which has secured her the goodwill of the common people. At the same time her grandmother Olenna, called the Queen of Thorns, conducts the more direct political negotiations with both Tywin and Tyrion Lannister. However, that is not all - in the very first episode it becomes clear that they are also taking an interest in Sansa, due to the disturbing rumours that they’ve heard about Joffrey’s abuse of her. Thus, they are quick to invite her to a private lunch in the lush gardens of the Red Keep.

It is both sweet and a bit sad to see how happy and excited Sansa is that there are some people that want to spend time with her, who are initially kind to her and who even made the effort to find out what her favorite food is.

Her hopeful little smile here shows how incredibly grateful she is that someone is seeking out her company and it really drives home just how isolated and lonely Sansa has been at the royal court - shunned by the people who have been standing idly by as she’s been abused in public.

She’s being charmed by the Tyrells and you can see how she’s beginning to think that things might change for her. Sadly, as Sansa, Olenna and Margaery sit down for a talk, it quickly becomes clear that the reason they have invited her to lunch is because they want something from her. It is worth watching the entire scene, especially the private conversation between the three women (timestamp; 2:22) because this conversation turns out to be rather traumatic for Sansa.

youtube

Sansa’s happiness is shattered the moment that Olenna Tyrell asks her to tell the truth about Joffrey. This turn in the conversation makes Sansa feel incredibly nervous and unsafe – she stammers and her eyes dart wildly about, as if she’s looking for an escape.

Sansa: I… I…

Olenna: You, you. Who else know better? We’ve heard some troubling tales. Is there any truth to them?

Cut to a close-up of Margaery, tilting her head, looking at Sansa. Then the camera cuts to a close-up of Sansa who looks down, having lost her happy smile. She’s clearly scared but perhaps also disappointed that these people have only sought out her company because they want something from her.

Olenna (VO): Has this boy mistreated you? ... Has he ripped out your tongue?

Olenna really comes across as a bully here, especially when you consider that Sansa is an abuse victim.

Sansa (stammers): King Joffrey, His Grace is very fair and handsome and as brave as a lion.

It is clear that Sansa is very uncomfortable and that she’s lying. Sansa’s response tells us that she doesn’t trust the Tyrells, and I also expect that she doesn’t react well to Olenna pressuring her like that (it is too similar to the way her abusers demanding answers from her), which we’ve seen in previous episodes. In fact, Olenna’s method is reminiscent of how Cersei Lannister interacts with Sansa (x), except that Olenna is more directly aggressive than Cersei.

Olenna: Yes, all Lannisters are lions… But how kind is he? How clever? Has he a good heart? A gentle hand?

Margaery: I’m to be his wife. I only want to know what that means.

I believe that Margaery is honest here. Then we get an OTS shot of Margaery, from Sansa’s POV. The camera work reinforces the POV structure – we experience this conversation mainly through Sansa point of view. The camera cuts to a close-up of Sansa, her mouth is slightly open. This is a reaction shot to Margaery’s utterance. Sansa is hesitating, pondering whether she should tell Margaery the truth. Margaery’s soft approach seems to work better than Olenna’s heavy-handed bullying. This moment, where Sansa is on the brink of telling the truth about Joffrey, is ruined when a servant appears. Sansa turns to look at him – and when she turns back, her expression is closed-off! She’s afraid of being overheard – she knows that there are spies everywhere in the Red Keep. Sansa lowers her head quickly and her gaze follows the retreating servant.

Olenna (leaning forward towards Sansa): Are you frightened child? No need for that.

She offers Sansa a lemon cake – her favorite food – in an attempt to calm her down.

Olenna: We’re only women here. Tell us the truth. No harm will come to you.

OTS shot of Sansa with her gaze lowered (from Margaery’s POV).

Sansa: My father always told the truth.

She lifts her gaze but it is clear that she isn’t looking at either woman. An avoidance of a gaze is often a defense mechanism. Sansa is scared and she doesn’t trust these women - and Olenna is making things worse by pressuring her since it is the way that Sansa’s abusers also act.

Olenna: Yes, he had that reputation. And they named him traitor and took his head.

A close-up of Sansa’s face, her gaze unfocused. She looks lost in thought and she looks so defeated. Oleanna is handling her all wrong, now invoking the traumatic experience of her father’s death.

Sansa: Joffrey…

Close-up of Sansa. She looks at Olenna now, her expression is both angry and anguished. Her eyes move, shifting her gaze to Margaery.

(GIF set by @aryaestarks)

Her lip quivers, she’s close to tears. Cut to Olenna looking thoughtful. Cut to OTS shot of Margaery (from Sansa’s POV).

Margaery (gently): Go on.

Cut to OTS shoot of Sansa, Margaery’s POV. Sansa lifts her gaze to Margaery. Then she starts to stammer because she’s afraid now that’s she just told the brutal truth to a pair of stranger that she doesn’t know she can trust.

Sansa: I can’t. I never meant…

Cut to OTS shot of Margaery, looking sad.

Sansa (VO): My father was a traitor.

Cut to OTS shot of Sansa (from Olenna’s POV).

Sansa: My brother as well. I have traitor’s blood.

Sansa’s eyes dart nervously between the two women. She is obviously scared and she’s reverted to tonelessly repeating the things that her abusers tell her. This is where I really began to dislike Olenna because she speaks to Sansa very much like her abusers do – relentlessly prodding her for answers when she is so obviously scared. Olenna gets her results after much prodding and by making Sansa angry – but she also rips open a painful wound and her aggressive stance makes Sansa retreat into the behaviour that she uses to protect herself – a rote litany where she repeats the things that her abusers tell her. Olenna is burning bridges here and you get the hint that Margaery’s more gentle approach might have been a better idea.

Sansa: Please, don’t make me say anymore.

At this point Sansa is pleading with them – she is terrified because she knows that she’ll get a beating (at minimum) if she is overheard. This is so incredibly sad.

Margaery: She’s terrified, Grandmother. Look at her.

Close-up of Olenna, leaning forward.

Olenna: Speak freely, child.

Cut to a shot of all three women, Sansa in center frame with her front to the camera, flanked by the two Tyrell women, their backs to the camera.

Olenna: We would never betray your confidence, I swear it.

Slow zoom on Sansa with a cut to a close-up of her face, her lips quivering and she raises a tearful gaze as ominous music begins to play.

After being bullied and re-traumatized, Sansa finally tells the basic truth about what Joffrey is: a monster. Yet both Olenna and Margaery react to this in a manner that seems rather cavalier and unbothered.

Cut to a close-up of Olenna.

Olenna: Ah.

Olenna turns to look at Margaery who simply shrugs as she eats a grape.

Close-up shot of Sansa, her eyes wet with unshed tears.

Sansa: Please, don’t stop the wedding.

Cut to OTS shot of Olenna (Sansa’s POV).

Olenna: Have to fear. The Lord Oaf of Highgarden is determined that Margaery shall be queen.

Cut to close-up of Sansa, she’s close to tears now. Then there’s a cut to an OTS shot of Margaery (Sansa’s POV): Margaery looks thoughtful, perhaps disappointed and she gives a little smile to Sansa.

Cut to a close-up of Olenna.

Olenna: Even so, we thank you for the truth…

The scene ends with a medium shot of Sansa, looking sad and dejected. She sits completely still, frozen like a statue as the camera keeps the focus on her.

What had initially been such a source of happiness to an abused and lonely girl turned out to be a horrible experience where Sansa once again learns that the powerful people of the royal court only care about what they can get from her, not for her as a person - and this is absolutely heartbreaking. Once again Sansa had her hopes lifted only to have them smashed.

This scene is, in many ways, very close to how it plays out in the book (though with less characters present). Most of the dialogue is taken directly from the book (ASoS) and like in the show, Sansa is absolutely terrified throughout the whole interview whilst Olenna keeps pressuring her. In the books, we know Sansa’s thoughts because we are in her head – we see what she thinks and we feel what she feels. That kind of interiority cannot really be recreated on television where the audience is placed on the outside when it comes to the inner life of the characters. Sansa’s acute fear during this interview is conveyed entirely through Sophie Turner’s acting: her facial expressions, her gestures and the modulation of her voice. It is fortunate that Turner is as talented as she is when it comes to non-verbal cues.

This entire scene makes me so sad for Sansa. She was so excited and delighted that someone was seeking out her company, looking as though they would be kind to her – only for her to realize that they want something from her. Even worse, Olenna basically bullies Sansa into telling the truth about Joffrey and then they both she and Margaery act rather cavalierly, as if the truth doesn’t matter (or that is what it would look like to Sansa). When they have finally gotten what they wanted, they continue as if nothing unusual has happened whilst Sansa just silently sits there, in emotional turmoil and bitterly disappointed.

To be continued...

(GIFs not mine)

#game of thrones#sansa stark#character analysis#winterfell's daughter#olenna tyrell#margaery tyrell#sophie turner

106 notes

·

View notes

Link

Harry Houdini wrote Sir Arthur Conan Doyle a heartfelt plea to recommend a medium “you know to be genuine.” His mother had just died and he wanted proof she had not completely vanished. The friends investigated mediums in the U.K., France and the U.S., where Scientific American was to pronounce the medium Margery genuine. They witnessed Eva C’s ecotoplasm and, in Atlantic City, Lady Doyle’s inspired communication.

ETHER, based on their letters, recreates the seances and their dramatically opposite narratives. As the gap widened, the “frenemies,” denounced each other on stages around the world with no end but their fortunes and lives. In the Afterlife of ETHER, the two are stuck in their passionate war about the nature of life and death. Was the Spiritualist, a doctor and author, a deluded fanatic? Was the ecape artist and master of physical illusion an unbiased observer of phenomena? As evidence mounts up, subjective and objective truths erupt in a transcendent conclusion.

The action in this play within a play, told with projections, puppetry, and stage magic, is orchestrated by their wives, Bess and Lady Doyle. They are aware that their worlds; Doyle’s study and and Houdini’s show, are contained within the Afterlife–our present in abstracted media. They are also tethered to their husbands. Eons weary, they join forces to resolve the bitter conflict-- so all can move on.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Secondary Sources

Armit, Ian. Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Avramescu, Catalin. An Intellectual History of Cannibalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Baert, Barbara. “Vix Clamantis in Deserto: John’s Head on the Silent Platter.” In Decapitation and Sacrifice.

Saint John’s Head in Interdisciplinary Perspectives: Text, Object, Medium, 63-92. Edited by Barbara

Baert and Sophia Rochmes. Leuven: Peeters, 2017.

—. “Wandering Heads, Wandering Media. Framing the Head of Saint John the Baptist Between Sculpture

and Painting.” In Decapitation and Sacrifice. Saint John’s Head in Interdisciplinary Perspectives:

Text, Object, Medium, 197-231. Edited by Barbara Baert and Sophia Rochmes. Leuven: Peeters,

2017.

Barber, Malcolm. The Trial of the Templars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Barstow, Anne Llewellyn. Witchcraze: a New History of the European Witch Hunts. New York: HarperOne,

1995.

Binski, Paul. Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1996.

Bonogofsky, Michelle. The Bioarchaeology of the Human Head: Decapitation, Decoration, and

Deformation. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Cameron, Euan. Enchanted Europe: Superstition, Reason, and Religion, 1250-1750. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2010.

Callan, Maeve Brigid. The Templars, the Witch, and the Wild Irish: Vengeance and Heresy in Medieval

Ireland. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Carmela, Mento and Settineri Salvatore. “The Medusa Complex: the Head Separated from the Body in the

Psychopathology of Negative Affects.” Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 4, no. 1

(2016): 1-11.

Cervone, Thea. “’Tucked Beneath Her Arm’: Culture, Ideology, and Fantasy in the Curious Legend of Anne

Boleyn.” In Heads Will Roll: Decapitation in the Medieval and Early Modern Imagination, 289-310.

Edited by Larissa Tracy and Jeff Massey. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Chatterjee, Paroma. “The Gifts of the Gorgon: A Close Look at a Byzantine Inkpot.” RES: Anthropology and

Aesthetics no. 65-66 (2014/2015): 212-223.

Cohen, Ester. “The Meaning of the Head in High Medieval Culture.” In Disembodied Heads in Medieval

and Early Modern Culture, 59-76. Edited by Catrien Santing, Barbara Baert, and Anita Traninger.

Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Cooper, Kate. The Virgin and the Bride: Idealized Womanhood in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 1999.

Cooper-Rompato, Christine F. “Decapitation, Martyrdom, and Late Medieval Execution Practices in The

Book of Margery Kempe.” In Heads Will Roll: Decapitation in the Medieval and Early Modern

Imagination, 73-89. Edited by Larissa Tracy and Jeff Massey. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Deveruex, George. “Fantasy and Symbol as Dimensions of Reality.” In Fantasy and Symbol: Studies in

Anthropological Interpretation, 19-41. Edited by R. H. Hook. London: Academic Press, 1979.

Dexter, Miriam Robbins. “The Ferocious and the Erotic: ‘Beautiful’ Medusa and the Neolithic Bird and

Snake.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 26, no. 1 (2010): 25-41.

Dowden, Ken. European Paganism: the Realities of Cult from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. London:

Routledge, 2000.

Eisler, Raine. Sacred Pleasure: Sex, Myth, and the Politics of the Body. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco,

1995.

Ezzy, Douglas. “Reassembling Religious Symbols: the Pagan God Baphomet.” Religion 45, no. 1 (2015): 24-

41.

Faulkner, Mark. “’Like a Virgin’: the Reheading of St. Edmund and Monastic Reform in Late-Tenth-Century

England.” In Heads Will Roll: Decapitation in the Medieval and Early Modern Imagination, 39-52.

Edited by Larissa Tracy and Jeff Massey. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Felson, Nancy R. “Appropriating Greek Myths: Strategies and Caveats.” Studies in Gender and Sexuality

17, no. 2 (2016): 1126-131.

Feng, Aileen A. “’Volto di Medusa’: Monumentalizing the Self in Petrarch’s Rerum vulgarium fragmenta.”

Forum Italicum 47, no. 3 (2013): 497-521.

Ferrari, Chiara. “Gender Reversals: Inversions and Conversions in Dante’s Rime Petrose.” Italica 90, 2

(2013): 153-175.

Flint, Valerie L. J. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Foster, Hal. “Medusa and the Real.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics no. 44 (Autumn 2003): 181-190.

Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Edited by Robert Fraser. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1994.

Freeman, Derek. “Severed Heads that Germinate.” In Fantasy and Symbol: Studies in Anthropological

Interpretation, 233-246. Edited by R. H. Hook. London: Academic Press, 1979.

Garber, Marjorie and Nancy J. Vickers. The Medusa Reader. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Graves, C. Pamela. “From an Archaeology of Iconoclasm to an Anthropology of the Body: Images,

Punishment, and Personhood in England, 1500-1660.” Current Anthropology 49, no. 1 (February

2008): 35-57.

Gow, Andrew Colin. “’Sanguis Naturalis’ and ‘Sanc de Miracle’: Ancient Medicine, ‘Superstition’ and the

Metaphysics of Medieval Healing.” Sudhoff’s Archiv 87, no. 2 (2003): 129-158.

Hartswick, Kim J. “The Gorgoneion on the Aigis of Athena: Genesis, Suppression and Survival.” Revue

Archeologique, Nouvelle Serie 2 (1993): 269-292.

Hayes, Dawn Marle. Body and Sacred Place in Medieval Europe, 1100-1389: Interpreting the Case of

Chartres Cathedral. London: Routledge, 2003.

Henderson, Joseph L. “Ancient Myths and Modern Man.” In Man and His Symbols, 97-156. Edited by Carl

G. Jung and M.-L. von Franz. London: Dell Publishing, 1964.

Henderson, Lizanne. Witchcraft and Folk Belief in the Age of Enlightenment, 1670-1740. Basingstoke:

Palgrave MacMillan, 2-16.

Hertz, Neil. “Medusa’s Head: Male Hysteria Under Political Pressure.” Representations 4 (Autumn 1983):

27-54.

Hook, R. H. “Phantasy and Symbol: a Psychoanalytic Point of View.” In Fantasy and Symbol: Studies in

Anthropological Interpretation, 267-291. Edited by R. H. Hook. London: Academic Press, 1979.

Huot, Sylvia. “The Medusa Interpolation in the Romance of the Rose: Mythographic Program and Ovidian

Intertext.” Speculum 62, no. 4 (1987): 865-877.

Jonowitz, Naomi. Icons of Power: Ritual Practices in Late Antiquity. University Park, PA: the Pennsylvania

State University Press, 2002.

Kayali, Talia. "Turkish Woman Awaits Trial after Beheading Her Alleged Rapist." CNN. September 06, 2012.

Accessed May 31, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2012/09/05/world/europe/turkey-rape-

beheading/index.html.

Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Klavins, Kaspars. “The Ideology of Christianity and Pagan Practice Among the Teutonic Knights: the Case

of the Baltic Region.” Journal of Baltic Studies 37, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 260-276.

Knusel, Christpher. “Courteous Knights and Cruel Avengers: a Consideration of the Changing Social

Context of Medieval Warfare from the Perspective of Human Remains.” In The Routledge

Handbook of the Bioarchaeology of Human Conflict, 263-281. Edited by Christopher Knusel and

Martin J. Smith. London: Routledge, 2014.

Kristeva, Julia. The Severed Head: Capital Visions. Translated by Jody Gladding. Edited by Lawrence D.

Kritzman. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

La Barre, Weston. “Species-Specific Biology, Magic, and Religion.” In Fantasy and Symbol: Studies in

Anthropological Interpretation, 55-63. Edited by R. H. Hook. London: Academic Press, 1979.

Larson, Frances. Severed: a History of Heads Lost and Heads Found. London: Granta Books, 2014.

Leeming, David. Medusa: In the Mirror of Time. London: Reaktion Books, 2013.

Lifshitz, Felice. “Priestly Women, Virginal Men: Litanies and their Discontents.” In Gender & Christianity in

Medieval Europe: New Practices, 87-102. Edited by Lisa M. Bitel and Felice Lifshitz. Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Linke, Uli. Blood and Nation: the European Aesthetics of Race. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 1999.

Lord, Evelyn. The Templar’s Curse. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman, 2008.

Mansfield, Margaret Nossel. “Dante and the Gorgon Within.” Italica 47, no. 2 (Summer 1970): 143-160.

Marx, Patricia A. “The Introduction of the Gorgoneion to the Shield and Aegis of Athena and the Question

of Endoios.” Revue Archeologique, Nouvelle Serie 2 (1993): 227-268.

Masciandaro, Nicola. “Non Potest Hoc Corpus Decollari: Beheading and the Impossible.” In Heads Will Roll:

Decapitation in the Medieval and Early Modern Imagination, 15-36. Edited by Larissa Tracy and

Jeff Massey. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Massey, Jeff and Larissa Tracy. Heads Will Roll: Decapitation in the Medieval and Early Modern

Imagination. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Miller, William Ian. The Anatomy of Disgust. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Mittman, Asa Simon. “Answering the Call of the Severed Head.” In Heads Will Roll: Decapitation in the

Medieval and Early Modern Imagination, 311-327. Edited by Larissa Tracy and Jeff Massey.

Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Mollenauer, Lynn Wood. Strange Revelations: Magic, Poison, and Sacrilege in Louis XIV’s France.

University Park, PA: the Pennsylvanian State University Press, 2007.

Novak, Shannon A. “How To Say Things With Bodies: Meaningful Violence on an American Frontier.” In

The Routledge Handbook of the Bioarchaeology of Human Conflict, 542-559. Edited by

Christopher Knusel and Martin J. Smith. London: Routledge, 2014.

Park, Katherine. “The Life of the Corpse: Division and Dissection in Late Medieval Europe.” The Journal of

the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 50 (January 1995): 111-132.

Phinney, Edward Jr. “Perseus’ Battle with the Gorgons.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American

Philological Association 102 (1971): 445-463.

Pratt, Annis. Dancing With Goddesses: Archetypes, Poetry, and Empowerment. Indianapolis: Indiana

University Press, 1994.

Ritchey, Sara. “Affective Medicine: Later Medieval Healing Communities and the Feminization of Health

Care Practices in the Thirteenth-Century Low Countries.” Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures

40, no. 2 (2014): 113-143.

Russo, Florence. “Cupiditas, the Medusean Heresy of Farinata.” Italica 89, no. 4 (2012): 442-463.

Santing, Catrien. “’And I Bear Your Beautiful Face Painted on My Chest’. The Longevity of the Heart as the

Primal Organ in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance.” In Heads Will Roll: Decapitation in the

Medieval and Early Modern Imagination, 271-306. Edited by Larissa Tracy and Jeff Massey.

Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Schulenburg, Jane Tibbetts. “Women’s Monasteries and Sacred Place: The Promotion of Saints’ Cults and

Miracles.” In Gender & Christianity in Medieval Europe: New Practices, 69-86. Edited by Lisa M.

Bitel and Felice Lifshitz. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Shoaf, R. A. “The Franklin’s Tale: Chaucer and Medusa.” The Chaucer Review 21, no. 2 (Fall 1986): 274-

290.

Silverman, Doris K. “Medusa: Sexuality, Power, Mastery, and Some Psychoanalytic Observations.” Studies

in Gender and Sexuality 17, no. 2 (2016): 114-125.

Tack, Laura. “The Body at the Banquet. How to Interpret the Presence of John’s Severed Head at Herod’s

Festive Meal in Mark 6:17-29.” In Decapitation and Sacrifice. Saint John’s Head in Interdisciplinary

Perspectives: Text, Object, Medium, 23-39. Edited by Barbara Baert and Sophia Rochmes. Leuven:

Peeters, 2017.

Timbers, Frances. Magic and Masculinity: Ritual Magic and Gender in the Early Modern Era. London: I.B.

Tauris, 2014.

Tucker, Katie. “The Osteology of Decapitation Burials From Roman Britain: A Post-Modern Burial Rite?”

In The Routledge Handbook of the Bioarchaeology of Human Conflict, 213-236. Edited by

Christopher Knusel and Martin J. Smith. London: Routledge, 2014.

Vanhauwaert, Soetkin. “Van Sint Jans Onthoofdinghe. The Sculpted Saint John’s Head in Performances of

Saint John’s Beheading in the Low Countries.” In Decapitation and Sacrifice. Saint John’s Head in

Interdisciplinary Perspectives: Text, Object, Medium, 93-137. Edited by Barbara Baert and Sophia

Rochmes. Leuven: Peeters, 2017.

Vorster, Johannes N. “The Blood of the Female Martyrs as the Sperm of the Early Church.” Religion &

Theology 10, no. 1 (2003): 66-99.

Westerhof, Danielle M. “Amputating the Traitor: Healing the Social Body in Public Executions for Treason

in Late Medieval England.” In The Ends of the Body: Identity and Community in Medieval Culture,

177-193. Edited by Suzanne Conklin Akbari and Jill Ross. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

2013.

Wilk, Stephen R. Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lab 2 Houdini vs Margery

It’s frightening what people used to believe in. To think, there was a time, that a movement like Spiritualism could have millions of followers in America!

The situation

Houdini has set out to disprove the mystics once and for all. He correctly assumed that after his death the mediums would claim that they could communicate with his spirit. Further advancing their course and twisting Houdini’s words.

Houdini decided the only way that was to create a code with his wife. That way the mediums couldn’t make false claims without his wife verifying that that it was from Houdini.

The solution must be able to differentiate between a real and fake medium.

Our solution

The solution that my group decided on was the idea of using timestamps between conversations. This will prevent a replay attack. This method was similar to the idea of a challenge response. The issue is the challenge must involve each time.

The code must have some qualities sin order to be successful. It must be repeatable and it must be there has to be a way to authenticate the message that was sent.

We were then introduced to the idea of an asymmetric cryptosystem! I’ll make a separate blog to go into depth about RSA and how the system works.

1 note

·

View note

Text

reading an incredible book and I just learned that one of the first "credible" mediums was a woman named margery crandon in the 1920s who claimed to be able to emit ectoplasm from (among other places) her vagina

3 notes

·

View notes