#but just sharing video of a protest related to a violent war where real people are dying in large numbers

Photo

Editor’s note: this post is part of the Recommended Reading series here on Can’t You Read; an ongoing and evolving feature that combines an easy to swipe info-graphic, a short journal, and a link to an important related discussion I’d like to share with readers.

A Culture of Predation Can’t Stop Fascist Pig Violence

In the wake of the frankly surprising (but extremely welcome) guilty verdicts in the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, I’ve tried very hard to reign in my cynicism. After all, the conviction of a cop for murder “in the line of duty,” let alone a white cop who murdered an African American man with an impoverished background, is about as common as a goddamn unicorn fart, and on that account alone the verdict is worth commemorating, if not necessarily celebrating.

While it would be unspeakably obtuse to suggest that the verdict represented some sort of positive justice, it’s also undeniable that many feel this moment may indeed be a starting point; a chance to at least begin to imagine what a positive justice for African Americans might look like. In particular numerous observers have pointed to the very public crumbling of the proverbial “blue wall” of silence, the fact that Chauvin’s fellow police officers passionately testified against him with the whole world watching, as a positive omen for the future of police reform.

Unfortunately I (and many other observers) have doubts about this position. I don’t mean to be a downer, but the truth is that nobody, not even immunized murderpigs and their commanders, can justify the horrifying video of Chauvin mindlessly executing George Floyd over the course of nine and a half minutes. Faced with the choice of openly embracing their own “little Eichmanns” in front of an outraged public, the Blue Meanies decided that ultimately it wasn’t worth protecting a fuck up like Derek Chauvin. The cost, both to his fellow thug cops, and the profession of policing as a whole, would simply have been too damn high to justify the reward.

The sad and horrifying truth here is that if Derek Chauvin had simply shot George Floyd, instead of casually kneeling on his neck for almost ten minutes, he’d probably be a free man today; just like so many cracker murderpigs before him. Furthermore, even this smallest of concessions probably wouldn’t have happened without months of nationwide protests conducted under a state of constant assault by violent, openly rioting police officers. That last reality is certainly not lost on fascists and neoliberal authoritarians; why else do you think reactionary lawmakers are rushing to pass legislation that criminalizes mass protest against racialized police violence?

Still, you can’t blame folks for hoping; hope can be a good thing if it gives you the strength and courage to continue a seemingly impossible fight for actual justice. Perhaps some long day from now we will look back on this moment and say “and the conviction of Derek Chauvin was the point when the wave ultimately broke, and the tide of cracker police violence finally rolled back” - even if it’s clear that these convictions, by themselves, do not have the power to enact the change we so desperately need.

Where I can and will find fault however, is with those deluded and disingenuous souls who have used this moment to once again champion the doomed cause of police reform; blithely ignorant or willfully oblivious to the fact that police reforms already failed to prevent the murder of George Floyd, and so many others like him. The bald truth is that the current establishment movement towards police reform is about maintaining the power and funding of the very same violent uniformed thugs who’re murdering poor people on behalf of the capitalist state in the first place; that’s why nobody is talking about removing qualified immunity for police officers, and that’s why even some cops themselves are coming around to the idea of reform at this late a date. In many ways, the real importance of the movement to “Defund the Police” is that the mere threat of taking away the sweet filthy ducats that pay murderpig salaries has already shifted the carceral establishment’s position towards bargaining; albeit, in bad faith.

The road to neofeudalist hell is paved with dark intentions however, and what establishment reformers, even and perhaps especially those who’re prepared to acknowledge the fundamentally racialized aspects of police violence, aren’t prepared to discuss in the open is the nature and purpose of policing itself in a capitalist society. There is no public examination of why it is that we keep hiring folks who turn out to be violent white supremacists to be police; and there certainly will be no discussion about the ways class relationships intersect with race through the designed function of racialized policing.

Despite the pro-police propaganda you’ve been fed all your life to suggest otherwise, the vast majority of what police actually do in America is to protect the wealth, property, and feelings of affluent white people and the corporations they own. Far from solving major crimes and preventing violence, modern policing in the Pig Empire revolves around nuisance violations, so-called broken windows policing, and other methods of harassing poor people for minor infractions of the law; remember, the police encounter that lead to the murder of George Floyd started over the purchase of cigarettes and a dodgy twenty dollar bill. The reason murderpigs can get away with violently assaulting protestors and journalists who threaten the established order is because that is precisely what they’re being paid to do, and indeed what their predecessors before them have always been paid to do.

On the surface, this class and capitalism analysis may appear to create a tension with the narrative that white supremacy and racism are also driving the crisis of police violence, but that’s really just about the same old establishment spin. As I’ve discussed in numerous prior essays, you simply cannot separate capitalism from white supremacy, or even racism, because bigoted ideas are propagated and spread for the specific purpose of marking out certain marginalized groups for exploitation and highly-lucrative (for some) repression.

Do you want to know what systemic racism in policing really looks like? It looks like hiring murderpigs to repress the poor, knowing full well that due to centuries of slavery and exploitation, the nonwhite and particularly African American population will be vastly overrepresented in the targeted communities. It looks like a supposedly colorblind war on drugs, the ongoing use of demonstratively racist stop and frisk practices, and expanded powers for your community’s “gang squad” in pretty much any neighborhood that just happens to be predominantly Black. It looks like literally profiting from these practices in ways that are sometimes extremely brazen and obvious, but sometimes hidden from everyday sight; even if they’re hardly much of a secret. The fact that the police are ultimately enforcers for the capitalist ruling class, also makes them enforcers of the white supremacist order that capitalism is so dependent upon in our society; there is no contradiction involved here.

Look; you don’t get rid of fascist murderpigs and white supremacists in law enforcement by throwing more money at nazi cops. Joe Biden can summon up all the pretty words he likes, but you can’t address the racialized nature of police violence without fundamentally altering either the racialized nature of inequality in American life, or the very purpose of policing in our society; and he’s sure as shit not talking about doing any of that at all. Thus, no matter how surprised and hopeful I am after the Chauvin guilty verdicts, that sense of positivity is ultimately tempered by the realization that “nothing will fundamentally change” - and that includes cracker thug pigs executing unarmed Black men on camera.

Although they might finally be better than openly fascist Republicans, the Democrats still don’t have answers to the problem of racialized police violence because ultimately, they don’t have answers to the crisis of capitalism itself. It’s not a question of reform or changing the law; murder is already illegal, even if you’re a white cop. Inequality, and the security force violence necessary to maintain it, is a festering sore inside the American body politic, and there are indeed consequences for essentially ignoring a crisis now so obvious and enraging to the public at large.

What kind of consequences? Well, let’s ask researcher and professor Temitope Oriola who provides one terrifying answer in the public journal, The Conversation:

“The United States is at Risk of an Armed Anti-Police Insurgency“ by Temitope Oriola

Or, you know, we could just abolish the murderpigs first; your call really - but don’t expect Palooka Joe to be much help, either way.

- nina illingworth

Independent writer, critic and analyst with a left focus. Please help me fight corporate censorship by sharing my articles with your friends online!

You can find my work at ninaillingworth.com, Can’t You Read, Media Madness and my Patreon Blog

Updates available on Instagram, Mastodon and Facebook. Podcast at “No Fugazi” on Soundcloud.

Inquiries and requests to speak to the manager @ASNinaWrites

Chat with fellow readers online at Anarcho Nina Writes on Discord!

“It’s ok Willie; swing heil, swing heil…”

#Recommended Reading#Police#Police State#Essays#ninaillingworth#Derek Chauvin#Chauvin Trial#George Floyd#George Floyd protests#George Floyd was murdered#Guilty#Black Lives Matter#support blm#BLM#Social Justice#Temitope Oriola#ACAB#fascism#neoliberal authoritarianism#Defund the Police#abolish the police#fire em all#racial justice#crimes by police#murders by police#murderpigs#pigs#Police reform#anti-protest laws#GOP is fascist

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Will Brexit Bring the Troubles Back to Northern Ireland? https://nyti.ms/2rHSWA7

This is a fascinating look at the very real and immediate consequences of Brexit. While looking back at the violent sectarian history and what Brexit could awaken in the very near future. WELL WORTH THE TIME

"In Northern Ireland, Brexit is stirring up an especially volatile brew. Sectarian tensions have been roiling in one form or another since at least the 17th century, when King James I encouraged the migration of Protestant colonists from Scotland and England to the northern Irish province of Ulster, where they enjoyed special privileges. An act of the British Parliament in 1920, during the Irish War of Independence, led to Ireland’s partition, creating a Protestant-majority Northern Ireland. Catholic grievances over discrimination fueled animosities that helped precipitate the Troubles. By the time of the Good Friday Agreement, some 3,600 people had been killed and tens of thousands injured. The peace deal created a power-sharing system of government, but it did not bring reconciliation."

Will Brexit Bring the Troubles Back to Northern Ireland?

As the United Kingdom confronts the prospect of dissolution, old factions are bracing for the possibility of new violence.

By James Angelo's | Published Dec. 30, 2019 | New York Times | Posted January 2, 2020 |

Belfast, like Berlin and Sarajevo, draws many visitors not despite its history of murderous conflict but because of it. Guides there take tourists to “peace walls,” the tall barricades of corrugated metal and concrete erected during the sectarian conflict, known as the Troubles, that began in 1968 and ravaged Northern Ireland for three decades. The walls were built to divide Protestant and Catholic enclaves and to prevent people from killing one another as the spiraling cycle of attacks took hold. Today tourists from around the world visit the walls and take selfies. This type of tourism is more peculiar in Belfast than in some other cities shaped by a legacy of atrocity. You can visit the intact parts of the Berlin Wall, for instance, with the knowledge that the wall no longer serves its original purpose. In Belfast, however, the walls are still there to divide, their continued presence deemed necessary to prevent a resurgence of violence.

Tours of the peace walls are often given by ex-paramilitary combatants who were active during the Troubles. The bald, stout, tattooed driver who took me on one such tour last June said he was “connected” to a paramilitary called the Ulster Defense Association, or the U.D.A., which was responsible for the killing of hundreds. He described himself as “no angel” during the Troubles and asked that I use only his first name, Robert, so as not to attract attention from the authorities — those involved can still face criminal prosecution — or from old foes. “We’re all paranoid as hell here,” he told me shortly after I got into his van. “The war is not over. Far from it.”

Robert had a quick, friendly smile and a fast wit that made it a little hard to imagine his past paramilitary connection. But those were almost unimaginably violent times. In the rote manner of tour guides everywhere, Robert told me his father was a U.D.A. member who in 1975 was shot dead by the Irish Republican Army, or I.R.A., the most lethal of the paramilitary groups, at the bus depot where he worked. Robert himself had dodged three I.R.A. assassination attempts, he said, and the organization also “blew up” his brother-in-law and murdered seven of his friends. We pulled up to a section of the peace wall in an industrial part of West Belfast that divides the neighborhood around Falls Road, heavily Catholic, from that around Shankill Road, which is heavily Protestant. Robert pointed out the metal gate that opens during the day to allow traffic to pass and closes again at night. In 2013, the government of Northern Ireland announced a goal of removing the walls within 10 years, but Robert was against this. The situation, he said, was still too turbulent. “We’re not ready for it,” he said. “I’m sure you’re probably fed up with hearing about Brexit,” he said. “But people are worried about a bad deal, the wrong deal or no deal.” If things went badly, he added, “I think we’re going to need these walls more than ever.”

The 1998 peace deal, known as the Good Friday Agreement, subdued the violence in Northern Ireland, but it did not resolve the underlying sectarian conflict that propelled it. Northern Ireland is in the United Kingdom. “Unionists” or “loyalists” — who tend to identify as Protestant and as British — want it to remain that way. “Nationalists” or “republicans” — who tend to identify as Catholic and Irish — want a united Ireland. The peace between these factions was facilitated by a tangentially related circumstance: Both the United Kingdom and Ireland had by then joined the European Union. This arrangement ensured uninhibited trade across the border, helping to render it virtually invisible and placating many Irish nationalists with circumstances they deemed acceptable if not ideal.

At the time the peace agreement was signed, however, a different movement was growing across the Irish Sea in England: a skepticism of the European Union, bubbling up among voters on both ends of the political spectrum but embraced in particular by the conservative hard right. As populist, nationalist parties grew in strength across Europe and much of the globe, this skepticism culminated in the 2016 Brexit referendum. Few of the hard-line politicians who advocated Brexit seemed to consider the consequences their push to “take back control” would have on the delicate peace in Northern Ireland or, for that matter, on the cohesion of the United Kingdom itself. In the more than three years since the referendum, the matter of Northern Ireland has presented a unique and treacherous stumbling block to any agreement between the British government and the European Union on the terms of withdrawal. How would the United Kingdom “take back control” of its borders without hardening the Irish border, thereby endangering the Good Friday Agreement? However this question was answered, one side or the other in the sectarian divide was bound to be upset.

On Dec. 12, voters in the United Kingdom gave Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his Conservative Party a sweeping parliamentary majority based on his pledge to “get Brexit done.” His success, attributable in part to the electorate’s sheer exhaustion with the Brexit limbo, means the United Kingdom will almost certainly leave the European Union by Jan. 31. This occasion, however, will by no means bring closure to a United Kingdom that has become so deeply fractured — not only along party lines but also by geography — that many people predict the most salient and enduring consequence will be a kind of monumental self-immolation: the breakup of the United Kingdom itself.

As if to illustrate the volatility of the matter, Robert pulled up to a mural on the Protestant side of the wall. Murals are ubiquitous on both sides of the divide, sanctifying former combatants who are invariably considered coldblooded murderers on the opposite side. This one, repainted around the time of the Brexit referendum, depicted Stephen McKeag, a commander in the U.D.A. known as Top Gun, against a cloudy sky, as if floating in heaven. “If you believe the stories you hear, he was one of the ones who won most of the trophies, what they call a trophy for the amount of people he has supposed to have allegedly killed,” Robert told me. McKeag, indeed known as one of the U.D.A.’s most lethal assassins, died in 2000 of a drug overdose. “Remember With Pride,” the mural read. Several tourists snapped photos. Robert got out of the van and shook hands with another tour guide, a man who looked much like him, with a bald head and dark sunglasses. “Thirty years ago, we would have been trying to kill each other,” Robert said. The other guide, apparently a republican ex-combatant, nodded in agreement. They exchanged a few niceties. Robert got back in the van.

“We’re friendly, but we don’t fully trust each other,” Robert said, his tone quickly changing. He showed me a picture on his phone of the same man at a militant republican parade. He then showed me a video, taken the previous month, outside a wake for a former member of the Irish National Liberation Army, or I.N.L.A., a Marxist republican paramilitary group formed in 1974. The I.N.L.A. ostensibly decommissioned its weapons along with other paramilitary groups as part of the peace process. The video, however, showed six men in balaclavas. One of them carried an assault rifle. They lined up in formation, and the gunman fired several shots into the sky. The mourners applauded.

Robert pointed to the soaring twin steeples of a Catholic cathedral on the other side of the wall. The shots had been fired around there just a few weeks earlier, he said. “That’s why I say these guys have never gone away,” he added. “That’s why we don’t trust each other.” As long as people on this side of the wall felt threatened, he said, loyalist paramilitaries would remain. “You think we’re going to go away?”

While British euro-skepticism is far from new, its culmination in Brexit represents the most tangible manifestation yet of the re-emergence of the nationalist strains in Europe — and beyond — that the European Union was meant to temper. The British conservatives who advocated Brexit acted partly under pressure from the far-right U.K. Independence Party, which under its former leader Nigel Farage grew more popular in the years leading up to the referendum with a staunchly pro-Brexit, anti-immigration platform. Implicit in the “take back control” message employed by the “Brexiteers” were themes promoted by populist-right movements everywhere: a reassertion of national sovereignty coupled with the claim that only those who advocate this represent the true will of the people against a globalized elite. As far-right parties have risen across Europe, Brexit has provided them a concrete victory — and it’s possibly not the last, as such parties in countries like Italy, France and Hungary seek to corrode the European Union from within.

The more immediate consequence of Brexit, however, may be not the dissolution of the European Union but the dissolution of the United Kingdom. Brexit and Boris Johnson’s decisive election victory were propelled primarily by voters in England. The United Kingdom, however, is made up of three additional smaller countries — Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland — that contain nationalist movements of another sort. In Scotland and Northern Ireland in particular, left-wing nationalist parties perceive the source of unwanted foreign meddling to emanate from London rather than from Brussels. Majorities of people in Scotland and Northern Ireland, in fact, cast ballots in favor of remaining in the European Union, and many of these voters now see Brexit as a reason to split from the United Kingdom. This is particularly the case in Scotland, where the pro-independence Scottish National Party, or S.N.P., won a landslide victory in December. When Scotland held a referendum on independence from the United Kingdom in 2014, 55 percent of voters elected to remain. Now, in light of Brexit, the S.N.P. is calling for another referendum. Polls suggest the result would be much closer now. “Independence is coming,” Ian Blackford, the leader of the Scottish Nationalist Party in the British Parliament, said during a debate there in October. “We will take our place as a proud European nation.”

In Northern Ireland, Brexit is stirring up an especially volatile brew. Sectarian tensions have been roiling in one form or another since at least the 17th century, when King James I encouraged the migration of Protestant colonists from Scotland and England to the northern Irish province of Ulster, where they enjoyed special privileges. An act of the British Parliament in 1920, during the Irish War of Independence, led to Ireland’s partition, creating a Protestant-majority Northern Ireland. Catholic grievances over discrimination fueled animosities that helped precipitate the Troubles. By the time of the Good Friday Agreement, some 3,600 people had been killed and tens of thousands injured. The peace deal created a power-sharing system of government, but it did not bring reconciliation. Currently, the two largest parties elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly are Sinn Fein — once the I.R.A.’s political wing — and the socially conservative Democratic Unionist Party, or D.U.P., which advocates continued union with Britain. The partisan rift between them has been so great that the assembly has not fully convened for nearly three years. Many people in Northern Ireland, exhausted with the sectarian paradigm, have tried to move beyond it; this is evident from the recent growth of the cross-community Alliance Party.

Still, the sectarian rift remains palpable in much of daily life, influencing everything from which soccer team locals support to the everyday language they use. Many Irish nationalists, for example, refer to Northern Ireland as “the North of Ireland.” Schools in Northern Ireland remain mostly segregated along religious lines, and children often learn disparate versions of history. Attempts to administer justice for past atrocities seem only to deepen divisions. A former British paratrooper known to the public as Soldier F is now on trial on charges of murdering two people during the massacre known as Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British troops opened fire on unarmed Catholic demonstrators in Londonderry, killing 13 that day. For many Irish nationalists, the trial is painfully belated and woefully insufficient. Many loyalists, however, see it as a witch hunt, and it’s not uncommon to see flags celebrating Soldier F’s parachute regiment fluttering in loyalist strongholds.

Sectarian tensions are most evident in the so-called interface areas, urban working-class neighborhoods where Catholic and Protestant communities live in proximity but often barely interact. In addition to the physical walls of separation — of which there are some 100 in Belfast alone — territory in such neighborhoods is demarcated by paramilitary flags hung by front doors or sometimes by painted curbs, either in the colors of the Union Jack or the Irish tricolor. Residents in these areas often avoid patronizing shops located on what is deemed enemy turf, even if they have to walk farther to buy what they want. These communities live “cheek by jowl, but in separate worlds,” John Brewer, a sociologist at Queen’s University Belfast, told me. Publicly funded cross-community programs for youths in these areas aim to bridge the rift. But poverty and unemployment in interface areas tend to be high, leaving many young men hopeless and vulnerable to radicalization. Rioting and violent clashes in these areas are not uncommon.

Attitudes on Brexit, too, largely fall along sectarian lines. A majority of Protestants in Northern Ireland — 60 percent — voted to leave the European Union, according to one survey, and the D.U.P., long skeptical of the European Union, backed Brexit. A majority of Catholics — 85 percent — voted to stay, a position also backed by Sinn Fein, in great part because many people feared that Brexit would result in a hardening of the Irish border. The fate of that border presented the main obstacle in negotiations between successive British conservative governments and the European Union on a withdrawal agreement. The European Union, mindful that a hard border would undermine the Good Friday Agreement and quite possibly lead to violence, wanted a deal that avoided customs checks at the border. In October, Boris Johnson found a partial solution by agreeing to a new customs border in the Irish Sea, between Britain and Northern Ireland; this means checks on goods traveling within the United Kingdom instead of on the Irish border. But hard-line unionists have been outraged by the deal, with some calling it the “betrayal act.” English conservatives, they believe, have abandoned Northern Ireland and endangered its place in the United Kingdom. At the same time, many Irish nationalists, though relieved that the immediate prospect of a hard Irish border has faded, have nevertheless been so angered by the uncertainty of the last years that they see continued membership in the United Kingdom as less tenable than ever.

Passions around Brexit are heated across the United Kingdom, but nowhere are the stakes potentially higher than in Northern Ireland. A 2015 report on paramilitaries drafted in part by MI5, the United Kingdom’s domestic intelligence agency, said that all the main paramilitary groups that operated during the Troubles remain intact; moreover, not all their weapons were decommissioned. The report’s authors considered it very unlikely that these paramilitaries would return to political violence, but the fact that they continue to hold on to weapons just in case seemed to underscore the fragility of the peace. At the same time, some so-called dissident republican groups have continued, since the Good Friday Agreement, to launch violent attacks in the name of achieving a united Ireland. The police judge the terrorist threat from these groups, including one calling itself the New I.R.A., to be “severe.” Dissident republicans have tried to use anger over Brexit as a rallying cry to win new recruits. Amid the confusion and bitterness sparked by Brexit, one thing seems clear: Northern Ireland’s delicate, hard-won equilibrium has been upset, and the consequences are potentially grave.

The headquarters of Saoradh, a small, self-declared political party whose name means “liberation” in Irish, is on a narrow street in Londonderry, Northern Ireland’s second-largest city, close to the Irish border. A mural on the facade of the building pretty well encapsulates the group’s outlook: It shows a masked paramilitary soldier wielding a rocket-propelled-grenade launcher under the slogan “Unfinished Revolution.” Northern Irish police officers say Saoradh is inextricably linked to the New I.R.A.

Inside the headquarters one afternoon in July, a thin and meticulously coiffed 27-year-old named Paddy Gallagher introduced himself to me as the party’s national press officer. While Saoradh calls itself a party, it does not engage in electoral politics, because this, as Gallagher put it, would mean becoming part of the “British infrastructure.” The party consists of “disaffected republicans,” he said, who “don’t believe the signing of the Good Friday Agreement was a good thing.” I asked him if the peace the agreement made possible wasn’t a good thing. He objected to the premise that such a peace exists. “The ongoing struggle for Irish unification and freedom hasn’t ended,” he said; people remain “willing and capable of carrying out acts of resistance.” He then provided an example: A few weeks earlier, a bomb was placed under a police officer’s car in Belfast. This was true. The officer spotted the bomb before getting in his car at a golf club, and it was safely defused; the New I.R.A. claimed responsibility. “I would assume that it was intended to kill that member of the British crown forces,” Gallagher told me.

On other occasions, the New I.R.A., which was formed in 2012, has killed intended targets. It claimed responsibility for attacks that killed two prison officers: a man named David Black, who was shot dead in 2012 in his car on the way to work, and Adrian Ismay, who died in 2016 after a bomb exploded under his van. The New I.R.A. killing that sparked the most attention and outrage came one night last April, during a republican riot in a Londonderry neighborhood called Creggan; when a masked rioter fired shots in the direction of an armored police vehicle, a bullet struck and killed Lyra McKee, a 29-year-old journalist who had arrived on the scene to report on the riot. A few days later, the New I.R.A. released a statement to a local newspaper saying that its volunteers were engaging “British crown forces” when McKee was “tragically killed,” depicting her death as collateral damage. Police officers later raided Saoradh’s headquarters as part of their investigation into the shooting, though no one has yet been charged with McKee’s murder. When I visited Creggan, I found signs posted on street lamps warning people not to cooperate with the police. “Informers will be shot,” read one of them, signed by the “I.R.A.”

Gallagher denied that Saoradh supports or has had links to the New I.R.A. — or any other armed groups — though he did not disavow their violent methods. “The Irish people can use any and all means necessary to achieve Irish freedom, whether it’s armed struggle or not,” he said. “The party believes that is up to the Irish people.” Gallagher spoke as if observing events his party played no active part in. The effect was menacing, particularly when he talked about the possibility that Brexit would result in a hard Irish border. “If there is a hard border in Ireland, and it is a manned or fixed installation, I can only assume it would be attacked,” he said, just as such installations were in the past.

Sinn Fein — the party that represents mainstream republicanism and whose leaders participated in the negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement — has offered a stark political response to the anger Brexit has fomented. Enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement is the “principle of consent,” which means that the people of Northern Ireland have a right to decide to which nation they want to belong. The demographics of Northern Ireland have been steadily shifting, and within the decade, a majority of its people will be Catholic, making the prospect of a united Ireland seem almost inevitable. This population shift is evident in election results that increasingly favor nationalists; in the United Kingdom parliamentary election in December, voters in Northern Ireland elected more nationalist representatives than unionist representatives for the first time in the country’s hundred-year history. Now Brexit has provided an opportunity for Sinn Fein to argue that the time to make that choice is near.

In July, I met Michelle O’Neill, Sinn Fein’s vice president, in her cavernous office in Northern Ireland’s palatial Parliament building. Brexit, she told me, had changed the paradigm in Northern Ireland, necessitating a referendum on Irish unity. Northern Ireland, she said, should not be dragged out of the European Union against its will. She seemed eager to assure not only her base but also the moderate unionists who voted to remain in the European Union and who might swing such a referendum. “I want to see a united Ireland,” O’Neill said. “But it has to be an inclusive Ireland. It has to be one where those who have an Irish identity and those who have a British identity feel part and parcel, feel that they have their place, and it’s valued and cherished.”

This seemed a shrewd political approach. But Northern Ireland’s history often reads like a case study in how the most extreme elements in the society can wreak undue havoc. Northern Irish police officers have warned that the threat from violent dissident republican groups remains severe even without the prospect of a hard Irish border. On the other side of the divide, many are outraged in the belief that the prospect of militant republican violence drove Boris Johnson and the European Union to keep the Irish border open at the expense of Northern Ireland’s place in the United Kingdom.

After Johnson’s deal was announced, a few hundred loyalists, including reputed paramilitary members, met in East Belfast to discuss how they should respond to their perceived betrayal. Following the meeting, Jamie Bryson, a self-described “loyalist activist,” told local reporters that the Brexit deal would be met with mass resistance. “One of the main reasons we were told there can be no border on the island of Ireland is because dissident republicans may attack it, but yet there’s been no consideration given to the loyalist community on how people may react to a border down the Irish Sea,” Bryson told a reporter from The Belfast Telegraph. “I don’t think anyone in loyalism wants to see violence. But obviously there’s a lot of anger at the minute.”

On a June evening in East Belfast, a group of men belonging to a Protestant fraternal organization called the Orange Order gathered at their meeting place in a red-brick Victorian hall for a special occasion: the unveiling of a new parade banner. The Orange Order is a staunchly unionist organization founded in 1795 and is named after William of Orange, the Protestant king who in the late 17th century took the throne after King James II, a Catholic, was deposed in the Glorious Revolution. Every year in Northern Ireland, Orangemen — who number around 30,000 — conduct thousands of parades, and they’ve been staging them for centuries. The biggest day of parading falls on July 12, a Protestant celebration that marks William’s decisive victory over James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, and on the eve of the holiday, unionists light large bonfires. These parades were historically seen as a display of Protestant supremacy, and they frequently led to sectarian clashes. Today they usually go off peacefully, though often under a heavy police presence. Orangemen say the parades are an innocent expression of their culture. Many nationalists still view them as intimidating.

This particular lodge, called the Young Men’s Christian Total Abstinence Loyal Orange Lodge 747, consisted, contrary to its name, largely of older gentlemen who wore suits and ties along with the orange sashes worn by Orangemen. The abstinence in this case was real — the men drank juice out of wineglasses — and the event began with the singing of a hymn. Then the parade banner, which had been covered with a white sheet, was unveiled, revealing a depiction of William of Orange atop a white horse at the Battle of the Boyne. The men applauded the banner, put on their bowler hats and filed out into the street, where a neatly uniformed marching band awaited. The drummers snapped and pounded, the flutists piped and the men marched their new banner past the brick rowhouses and storefronts of East Belfast, a working-class stronghold blighted in parts by poverty. The Orangemen strutted past homes decorated with flags of loyalist paramilitaries and murals showing armed paramilitary men in balaclavas. It made for a somewhat jarring juxtaposition, seeing men of such apparent decorum pass such harsh images. The Orangemen ended their march with a rendition of “God Save the Queen.”

Back inside the hall, as they dined on plates of roast beef and potatoes, a Presbyterian minister named Mervyn Gibson, the grand secretary of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland, approached the lectern. “Today some are trying to bribe us out of the United Kingdom by claiming to offer us a better lifestyle in the Republic of Ireland,” he said. Gibson seemed to be referring to arguments that the Northern Ireland economy would flourish within a united Ireland. “Our loyalty and identity are not about economics,” Gibson went on, “not something to be bartered or traded.” Those now threatening a referendum on Irish unity, he added, were the same people who “tried to bomb and murder us out of the United Kingdom. They failed then, and they’ll fail again,” he said, and then concluded: “We’re born British, we’ll remain British, we’ll die British.” The men of the lodge responded: “Hear! Hear!”

The key question, it seemed, was how far these men would go to remain British. On another occasion, Gibson told me he would accept a democratic vote for Irish unity it if it came to that. Others, however, are more strident. Many loyalists feel a sense of decline as Catholics have gained more rights and upward mobility; young loyalist men in interface areas who used to be guaranteed factory jobs by virtue of their identity now face high unemployment and a sense that their standing in society has eroded. Such grievances seem to only reinforce people’s sense of identity. Loyalist paramilitaries feed off this to gain recruits, though according to the police, these groups are more often involved in organized crime than in politics. Still, in East Belfast, I observed how one paramilitary — the U.V.F. — had the capacity to stir up sectarian passions.

Last summer, in advance of the July 12 celebrations, members of Belfast’s republican-led City Council voted to remove a pyre made of wooden pallets in East Belfast — set up for the coming bonfire night — saying it was illegally on city property, namely the parking lot of a recreation center. Local loyalists responded angrily and vowed not to allow the city to remove the pyre, resulting in a standoff that, for days, became the main news story in town. At a demonstration one evening that drew hundreds of people to the site of the pyre, I met a number of masked young men who told me they were protecting the pyre from being dismantled. Jamie Bryson, the loyalist activist, spoke to the crowd. “Standing exposed tonight is the actual agenda of Belfast City Council,” he said. “And it is the total demolition of every aspect of Protestant unionist and loyalist culture,” he went on. “We will not have it!” This inspired a fervent round of applause. “No surrender!” shouted a woman next to me who wore a shirt that said “Me Wrong?” on it. “This is British land, and it will stay British land,” she then told me.

Police officers said the standoff was whipped up by the U.V.F. In a letter to the City Council, the police warned that any attempt to remove the pyre would “cause a severe, violent confrontation, orchestrated by the U.V.F.” and that the “use of firearms during such disorder cannot be ruled out.” Ultimately, the police did not move in. This was, Bryson later wrote in an online newsletter, a “momentous and hugely symbolic victory within the context of the larger cultural war.”

On the bonfire night, I went to another pyre on a barren plot next to a peace wall in West Belfast, where my tour guide, Robert, had taken me. As the sky slowly darkened, a D.J. played pulsing techno. Drunken teenagers milled around. A small, impromptu marching band of revelers formed. They sang a U.V.F. tune at the top of their lungs: “On my gravestone, carve a simple message: ‘Here lies a soldier of the U.V.F.’ ” I spoke to one woman among them who told me that this was all in good fun, just an expression of loyalist culture. But you couldn’t help noticing that the pyre that was about to be lit had been bedecked with flags of the Republic of Ireland.

______

James Angelos is a contributing writer for the magazine based in Berlin. He last wrote about anti-Semitism in Germany. Ivor Prickett is an Irish photographer. He was a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in breaking-news photography for his coverage of battles in Mosul and Raqqa.

#brexit#uknews#uk#citizens uk#uk news#uk politics#ireland#northern ireland#republican politics#politics and government#us politics#politics#u.s. news#worldpolitics#world news#europe#european union#european history#history#religion#national news#national security

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curfews Put In Place After Another Day Of Blazing Protests + Officials Blame ‘Outsiders’ For Violence In Several States

Several cities spring into action putting curfews in place where raging protests over the death of George Floyd grow. There have been peaceful protests and there has been violent protests. Public officials are blaming the violence on “outsiders” traveling state-to-state to wreak havoc. More inside…

Another night of blazing protests swept the nation last night. Buildings were burned, people were shot and thousands were arrested. However, there have been plenty of peaceful protests that have been launched to demand justice for the killing of George Floyd. The Minneapolis man lost his life after a white police officer – Derek Chauvin – pressed his knee into his neck for nearly 9 minutes. George was taken to the hospital via ambulance where he was pronounced dead.

Since then, former police officer Derek Chauvin was arrested and charged with third degree murder and manslaughter. However, those charges do NOT match up to what the former police officer did. Also, the other three former police officers have NOT be charged even though new video shows three officers pinning George (who was already hancuffed) down.

Folks are demanding justice for George Floyd. By any means necessary. Demonstrations happened in more than 75 cities across the nation.

For some reason the media doesn’t seem interested in showing these parts of the protests.#BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/lVP1Il99dk

— Joshua Potash (@JoshuaPotash) May 31, 2020

Protesters in Newark, NJ held a peaceful protest:

The world needs to know about what happened in Newark today. A Black city, with a Black mayor (who marched with us), and many Black owned businesses. 100% peaceful demonstrations. Anger was allowed to be expressed in a healthy way and wasn’t met with force. pic.twitter.com/eyRrO0OIzN

— Brian Scully (@brian_m_scully) May 31, 2020

New Jersey had one of most peaceful protest. Even the NJ police joined the protesters. Please share this to show how to really protest peacefully and not riot. #BlackLivesMatter #Riot2020 #GeorgeFloydProtests #newjerseyprotest pic.twitter.com/d41YjoeROY

— Christian (@Chris_Parra__) May 31, 2020

Los Angeles protesters were peaceful (until the cops showed up):

An endless, peaceful river in LA last night.

This is what protests look like before police show up.#BlackLivesMatter

pic.twitter.com/d5JcHe6yuW

— Joshua Potash (@JoshuaPotash) May 31, 2020

People in Toronto gathered peacefully:

Peaceful protests happening in Toronto Canada yesterday!

#BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/wAjIkRYjzg

— 5SOS UPDATES! (@5sosworldalerts) May 31, 2020

Two demonstrations in Detroit unified:

2 peaceful protests running into each other and merging into one in Detroit pic.twitter.com/0ddI7sJTQp

— Kayla (@CupcakeStoner) May 31, 2020

Peaceful protests went down in Jacksonville, FL:

Peaceful protests captured in #Jacksonville, FL yesterday. #GeorgeFloyd #injustice via @bajangrlinasouthernwrld

A post shared by TheYBF (@theybf_daily) on May 31, 2020 at 6:26am PDT

Peaceful protests were even held overseas in solidarity:

peaceful protest today in liverpool. we knelt for 8 minutes and 46 seconds- the time it took derek chauvin to murder george floyd. we will remember him, and the countless other black individuals killed by corrupt cops under systematic racism. #BLACK_LIVES_MATTER pic.twitter.com/J8XftdakpC

— rae (@tpwkrae) May 31, 2020

today was beautiful, we had a peaceful protest. I had never been surrounded with so much strong energy. this needs to stop, if it takes a thousand protests, so be it. all of us need to come together and use our voices#BLACK_LIVES_MATTER#BlackLivesMatterUK pic.twitter.com/g0uf9aL7uO

— BLM (@candyyjoon) May 31, 2020

Unfortunately, all the protests haven’t been peaceful. An NYPD officer snatched the mask off a black man’s face and pepper sprayed him…FOR NO REASON. Check it below:

I am heartbroken and disgusted to see one of my family members a young black man w/his hands up peacefully protesting and an NYPD officer pulls down his mask and pepper sprays him. @NYCSpeakerCoJo @BPEricAdams @FarahNLouis @JumaaneWilliams @NewYorkStateAG @NYPDShea cc: @EOsyd pic.twitter.com/tGK5XWS0bt

— Ms. Anju J. Rupchandani (@AJRupchandani) May 31, 2020

Several cities across the nation looked like war zones last night as people protested in the streets over the death of George Floyd:

Sometimes (arguably often times) being peaceful doesn’t work. Citizens being able to peacefully handle situations and use the current system to get the Justice it is there to afford SHOULD be the status quo. More than not, though, it isn’t. Not for everyone, especially not always for those without privilege. Until those in power operate accordingly across the board to ensure justice is served to EVERY person under the law, rage will continue. #georgefloyd #breonnataylor #ahmaudarbery #revolution

A post shared by TheYBF (@theybf_daily) on May 31, 2020 at 8:51am PDT

MOB MENTALITY via @shaunking Police brutality in America is on full display right now. From coast to coast.

A post shared by TattleTailzz (@tattle_tailzz) on May 31, 2020 at 5:55am PDT

Columbia, SC man gets arrested during protest for almost getting ran over by Police truck. Make sure this man doesn’t get falsely charged pic.twitter.com/pSqhFXqYTU

— 803Gee (@803Mcfly) May 31, 2020

The National Guard has moved in on Minneapolis and they are shooting people with rubber bullets who don't follow their commands:

Share widely: National guard and MPD sweeping our residential street. Shooting paint canisters at us on our own front porch. Yelling “light em up” #JusticeForGeorgeFloyd #JusticeForGeorge #BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/bW48imyt55

— Tanya Kerssen (@tkerssen) May 31, 2020

It got real in Richmond, Va last night:

Visuals from Richmond Virginia. One of many fires taking place. This one is on east Broad Street (credit: Kaylee Walton) @NBC12 #GeorgeFloydProtests #RichmondVA pic.twitter.com/4OYhLyR7y1

— Eric Perry (@EricpNBC12) May 31, 2020

Protesters also targeted United Daughters of the Confederacy. You can see damage inside and outside of the building. @NBC12 #richmond pic.twitter.com/5JnAA6Jrq5

— Eric Perry (@EricpNBC12) May 31, 2020

A viewer sent this picture from inside the @WholeFoods on Broad.

Several businesses were damaged in the last 48 hours.

(sorry but they didn't have to knock this GOODT wine over...) @NBC12 pic.twitter.com/3ONfseK1zm

— Eric Perry (@EricpNBC12) May 31, 2020

One person was shot and is facing life threatening injuries. Two Virginia State Police troopers were also injured:

Big fire on East Broad Street. This is just one of many happening across #RichmondVA

Police confirm one person was shot overnight (protest related) (credit: Kaylee Walton)

Praying for peace @NBC12 #GeorgeFloydProtests #GeorgeFloyd pic.twitter.com/ULC0hflDyy

— Eric Perry (@EricpNBC12) May 31, 2020

Virginia State Police confirm two officers were injured overnight in Prince William County as they were called in to assist.

One Trooper was hit in the head with a brick and the other in the leg with a rock.

Both suffered minor injuries and is expected to be ok. @NBC12

— Eric Perry (@EricpNBC12) May 31, 2020

In NYC, a police SUV RAMMED into protesters:

NYPD definitely has some explaining to do as at least 1 police SUV rammed into a sea of protestors during yesterday’s protests in Brooklyn.

A post shared by TheYBF (@theybf_daily) on May 31, 2020 at 6:14am PDT

THE POLICE ARE RUNNING THE PEOPLE WITH THEIR CARS, THEY ARE THROWING PUMPS, LACRIMOGENOUS GASES AND ARCHES AND ARROWS. LEAVE THE PROTEST NOW #BLACK_LIVES_MATTER pic.twitter.com/OVhpzrD9uF

— Milimilanga (@fllnglouie91s) May 31, 2020

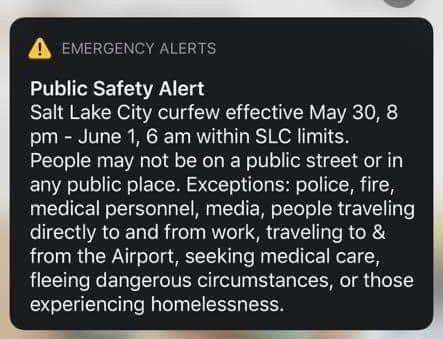

Several cities have now imposed curfews including, Atlanta, Seattle, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Denver, Salt Lake City, Nashville, Minneapolis, and Richmond, VA among others due to the raging protests. Most curfews are starting at 8pm to 6am.

A post shared by (@ancient_future9) on May 31, 2020 at 6:18am PDT

Many government officials believe there are "outside groups and crisis actors" coming into cities wreaking havoc.

black women tried to deescalate white men from stop inciting unnecessary violence at a protest: “when you do that they dont come after YOU they come after US” and they literally told her that it doesnt matter because “they’re gonna kill you anyways”pic.twitter.com/w6uF1DP6db

— kawira (@versacetaehyung) May 31, 2020

“We have people from across the country who have traveled many states to be here. We know that this is an organized effort,” Chief Will Smith said. “We're committed to try and identify those that are behind it. And we're doing our very level best to arrest those that are perpetrating the violence on our community, our city, and against our citizens.”

The Pittsburgh Post Gazette reports:

As protests over the death of George Floyd grow in cities across the U.S., government officials have been warning of the “outsiders” — groups of organized rioters they say are flooding into major cities not to call for justice but to cause destruction.

But the state and federal officials have offered differing assessments of who the outsiders are. They’ve blamed left-wing extremists, far-right white nationalists and even suggested the involvement of drug cartels. These leaders have offered little evidence to back up those claims, and the chaos of the protests makes verifying identities and motives exceedingly difficult.

Buffalo, NY is on curfew. They too believe there are outsiders coming in to destroy the city. NPR reports:

Mayor Byron Brown said the city was a target of an outside coordinated effort.

“Law enforcement has intelligence and has briefed us that there are people that are in this community from outside the city of Buffalo and outside of Erie County,” said Brown. “[They] are contributing to these problems. In fact, they are the ringleaders of inciting violence.”

The distinction is important.

By the way, former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick is establishing a fund to pay legal fees for George Floyd protesters in Minneapolis. Kaepernick's Know Your Rights Camp Legal Defense Initiative is working with top defense lawyers in the Minneapolis, Minnesota, area to help those in need of legal assistance, according to the group's website.

Photos: AP Photo/ Ringo H.W. Chiu/Matt Rourke

[Read More ...]

source http://theybf.com/2020/05/31/curfews-put-in-place-after-another-day-of-blazing-protests-officials-blame-%E2%80%98outsiders%E2%80%99-fo

0 notes

Text

In Georgia, cinema is the latest flashpoint in the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights

Register at https://mignation.com The Only Social Network for Migrants. #Immigration, #Migration, #Mignation ---

New Post has been published on http://khalilhumam.com/in-georgia-cinema-is-the-latest-flashpoint-in-the-struggle-for-lgbtq-rights/

In Georgia, cinema is the latest flashpoint in the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights

Screenshot from the trailer of the “And then we danced” movie by Levan Akin, showing the main character Merab. Image via Music Box Films’ December 2019 YouTube video.

A 2019 film about the story of an LGBT dancer continues to strongly polarise Georgian society. “And then we danced,” filmed in this South Caucasus nation of 3.5 million people, offers a snapshot of contemporary Georgian society — including its intolerance towards members of the LGBTQ+ community. It tells the story of Merab, a professional dancer who specialises in traditional Georgian dance. While training for a role in the prestigious Georgian National Ensemble, he develops a romantic and erotic relationship with another male dancer, Irakli. Social pressure tears the lovers apart; when Merab is outed, he considers leaving his country behind. Director Levan Akin's film is an homage to a country undergoing rapid and contradictory changes. It is a country besieged by foreign tourists alongside grinding economic hardships for most of the population — compelling some to emigrate. It is a tribute to the timeless courtyards of the Georgian capital Tbilisi, where watchful neighbours can be a lifeline — and a curse. It is a portrayal of a city whose rebellious youth find solace in drugs (and the landmark, gay-friendly club Bassiani), and whose LGBTQ+ community must live their lives in secret, sometimes forcing themselves into heterosexual marriages. In this context, Merab's love for traditional dance — the “soul of the nation” — and for Irakli are steeped in tragedy, in a country struggling with sexism and patriarchy. The film has made some powerful enemies. [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n25XEhQ6764?feature=oembed&w=650&h=366] Georgia is a predominantly Christian country whose Orthodox Church is legally separate from the state. Nevertheless, it is highly regarded, wealthy, influential and does comment regularly on social and political issues. Its official view on LGBTQ+ people is that they are “deviant” people. On May 17, 2013, LGBTQ+ activists marching in Tbilisi were attacked by far-right protesters led by religious leaders on the International Day against Homophobia. Since 2014, the Georgian Orthodox Church has celebrated “Family Purity Day” every May 17 to fight what it describes as “gay propaganda.” When the LGBTQ+ community announced that it would hold its first Pride Parade in Tbilisi, church figures voiced strong criticism. The government announced that it would not provide protection for the event, leading to its postponement several times over the summer, and eventual cancellation. The Georgian Orthodox Church condemned “And then we danced” even before it hit the screens, issuing angry statements during its filming. When it was first released in Tbilisi and the seaside city of Batumi on November 8, 2019, far-right protesters, once again with church support, prevented viewers from entering the cinemas. But this time, the government did react, by sending police to protect moviegoers and arresting protesters, thereby enabling the screenings did take place. On November 6, the Patriarchate of the Georgian Orthodox Church made the following statement, which it later removed:

საქართველოს მართლმადიდებელი ეკლესია ყოველთვის იყო, არის და იქნება კატეგორიულად შეურიგებელი როგორც საერთოდ ცოდვის, ისე, მითუმეტეს, სოდომური ურთიერთობების პოპულარიზაციისა და დაკანონებისადმი. ამიტომაც ყოვლად მიუღებლად მიგვაჩნია ასეთი ფილმის კინო-თეატრებში ჩვენება.

The Georgian Orthodox Church is, has always been, and always will be categorically opposed to the promotion and legalisation of sin in general, and of the sin of Sodom in particular. That is why we consider it unacceptable to show such a film in cinemas.

As the church emphasises its role as the guardian of the Georgian soul and the nation, the film was particularly sensitive given the prominent role played by traditional dance. During the Soviet period until 1991, this dance almost became a shorthand for anything Georgian, in keeping with Moscow's interest in representing the country's 120 ethnic groups through strong folkloric images. Accordingly the chokha, the garment worn by Georgian male dancers, has come to visually symbolise Georgia. Tellingly, the main choreographer for “And then we danced” has chosen to remain anonymous, perhaps confirming the dancing teacher's words warning in the film about the “purity of the Georgian dance” and the “need to be masculine.” It is no less telling that while the film begins with a black and white archive of these performances, it ends with a dramatic dance in bright blood red, free of those rules and freed in expression. Another sensitive point was the fact that the film was chosen as Sweden's entry for the 2020 Oscar ceremony. The film has already obtained several awards, and several European and Asian countries have bought the rights to broadcast it as well — as producer Ketie Daniela notes, that is a rare privilege for a Georgian film. In an interview this February, Levan Akin, the film's Swedish-Georgian director whose parents left Georgia in the 1960s, expressed surprised at the intensity of Georgian reactions to the film. “I knew it would be controversial but never thought it would be that controversial; there were riots, people got injured, and we could only show it for three days,” remarks Akin. [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQHSf5zEkOQ?feature=oembed&w=650&h=366] The public debate over the film is just the latest chapter in a longer fight for LGBTQ+ rights in Georgia. The first victory in that struggle was won in 2000, when Georgia decriminalised consensual same-sex relations. To this day, among all the 15 post-Soviet states (except the three Baltic states which are members of the European Union), Georgia has some of the most progressive legislation in this regard: in 2014 it amended its laws to make hate crimes related to sexual orientation an aggravating factor in prosecution. Yet there is a huge gap between the law on paper and the reality of life for members of the community who continue to face discrimination, hate speech, and violent crimes. As Giorgi Gogia, Associate Director for Europe and Central Asia at Human Rights Watch, explained in an interview with GlobalVoices:

Georgia adopted comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation in 2014 that prohibits discrimination on all grounds, including sexual orientation and gender identity. The law also puts the ombudsman’s office in charge of overseeing anti-discrimination measures. The legislation was adopted as part of Georgia’s visa liberalisation action plan with the EU. At the same time, the ruling Georgian Dream party proposed constitutional amendments defining marriage “as a union of a woman and a man”, thus a ban on same-sex marriage. I am afraid that the growing polarisation in the run up to the crucial parliamentary polls later in the fall might push the ruling party towards more populist stance. Homosexuality remains highly stigmatised in Georgia and is at the epicentre of “culture wars” between progressives and conservatives, with anti-gay elements backed by the Church, often with hateful rhetoric.

Read more: No place for transgender people in Georgia's labour market

A more recent documentary, “March for dignity” (released in mid-June and directed by John Eames) has been released to revisit and reflect on the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights in Georgia: [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJW5tVgXnkE?feature=oembed&w=650&h=366] Giorgi Tabagiri, a representative of Tbilisi Pride, which maintains its own Twitter account, told GlobalVoices that progress may be incremental, but it is progress nonetheless:

We had great plans for the 2020 Pride March, but after seeing all those events cancelled in Europe, we took the tough decision to call it off. And eventually we decided to launch other activities: rainbow masks in this COVID-19 period, that became very successful to the point that celebrities wore them on state television. We also distributed 100 large rainbow flags that people used in streets and on buildings, which is a very sensitive issue here. Our office is picketed regularly by far-right groups demanding we take them down. On May 17, we organised an online demonstration against homophobia on Zoom, collaborating with media and broadcasting live on Facebook. About 120,000 people watched it, which is a large figure for Georgia. Overall, we do see positive changes, including in legislation, but the problem is that it does not translate into social acceptance, so we have a long way to go. The movie “And then we danced” will certainly have a long-term impact in this regard, as more people will watch it. We also need more public figures as allies, but so far very few of them who are LGBTQ+ are out.

Akin's film may be a fiction, but the social stigma it depicts is deadly real. If things can change, perhaps stories about the Merabs and Iraklis of tomorrow will look very different indeed.

Written by Filip Noubel, Teona Kakhiani · comments (0)

Donate · Share this: twitter facebook reddit

0 notes