#caryl brahms

Text

No Nightingales is a 1944 comedy novel by Caryl Brahms and S.J. Simon, a regular writing team between 1937 and 1950. The title is a reference to the popular wartime song A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square. The novel is loosely inspired by the legend of the supposedly haunted townhouse 50 Berkeley Square. The story is set in a house in Berkeley Square, haunted by two benevolent ghosts coping with new occupants between the reigns of Queen Anne and George V.

You can read the book for free online at the archive.org :) <3 (free registration needed)

773 notes

·

View notes

Text

Share your GOS2 bibliography with me

How crazy is it that season 2 has basically forced me to go back to university. I’ve done more reading and critical analysis and historical research than I have in years. I bite my thumb at you, Neil (affectionate).

And as I’m sure I’m not alone in this, I’d love to see your bibliography of all of the references or reading/watch lists. I’m sure to pick up a few good ones! I’ll go first.

Movies + TV

Arrival - Denis Villeneuve

Clue - Jonathan Lynn

I Know Where I'm Going - Powell & Pressburger

The Ball - Magnus Dennison and Katja Roberts

Every Day - Michael Sucsy

About Time - Richard Curtis

The Red Shoes - Powell & Pressburger

The Small Back Room - Powell & Pressburger

The Tales of Hoffmann - Powell & Pressburger

Stairway to Heaven - Powell & Pressburger

Ill Met By Moonlight - Powell & Pressburger

The League of Gentlemen's Apocalypse - Steve Bendelack

Monty Python's Life of Brian - Terry Jones

Monty Python and the Holy Grail - Terry Gilliam & Terry Jones

The Twilight zone (The Arrival) Boris Sagal

The Twilight zone (The Hitch-Hiker) - Alvin Ganzer

Staged (Seasons 1 and 2) - Simon Evans & Phin Glynn

Books

The Crow Road - Iain Banks

The Bridge - Iain Banks

The Scholars of Night - John M. Ford

Symbols of Sacred Science - René Guénon

Catch-22 - Joseph Heller

A Tale of Two Cities - Charles Dickens

The Colour of Magic - Terry Pratchett

Night Watch (Discworld) - Terry Pratchett

Parlement of Foules - Geoffrey Chaucer

The language of the birds - Farid ud-Din Attar

Pride & Prejudice - Jane Austen

Persuasion - Jane Austen

Midnight Days - Neil Gaiman

Negative Burn #11 - Neil Gaiman

Chivalry - Neil Gaiman

Other

Les contes d'Hoffamann - opera, Jacques Offenbach

Don Giovanni - opera, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

The Line, the Cross and the Curve - musical, Kate Bush

The book of Enoch - Ethiopian Apocryphal trs. Rev. George Schodde, PhD

I'm sure there will be more... sigh.

Spoiler alert: there are more!

Donnie Darko - 2001, Richard Kelly

Nothing Lasts Forever - 1984, Tom Schiller

The Ghosts of Berkley Square - 1947, Vernon Sewell

Brazil! - 1985, Terry Gilliam

No Bed for Bacon - 1941, Caryl Brahms and S. J. Simon

Don't, Mr Disraeli! - 1949, Caryl Brahms and S. J. Simon

Murder Mysteries - Neil Gaiman

The Man Who Was Thursday - 1908, GK Chesterton

Small Gods - 1992, Terry Pratchett

Ipomadon - Medieval - Trs. Richard Scott-Robinson

#go season 2#good omens 2#art director talks good omens#go2#good omens season 2#good omens#good omens analysis#good omens s2#good omens season two#neil gaiman#good omens meta#good omens prime

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘The moon, Diana’s orb,

shining upon Hecate’s dark plaything, the Earth.’

Caryl Brahms & S. J. Simon

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

27 and 21 for the ask game please, if you have time 🌹

Thank you - always time for you...

27. What's your favourite book? Or just one you've read a few times?

Oooh - so many possibilities... these are all ones I've read and re-read over a long time.

The one that's been a favourite for a very long time: The Bone People (Keri Hulme); the Alexander Trilogy (Mary Renault);

The one that makes me laugh every time: No Bed for Bacon (Caryl Brahms & SJ Simon); Bridge in the Menagerie et seq (Victor Mollo; I giggled at those before I really understood bridge); Going Postal as the random Terry Pratchett; le petit Nicolas in general

Non-fic that made me see the world differently: Landau & Lifschitz on mechanics; Eric Hobsbawm on history.

edited because I forgot to do 21: how was your day today?

I managed to leave the hotel I stayed in last night with an actual physical room key, and had to send it back in a taxi, so that was annoying. More generally, busy but I think useful and I am looking forward to being at home and with fewer people tonight. And all the nice asks have been fun in the corners of the day.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Nightingales by S.J. Simon & Caryl Brahms

My rating: 2.25 of 5 stars

Moods: funny lighthearted relaxing slow-paced

Plot- or character-driven? N/A

Strong character development? No

Loveable characters? Yes

Diverse cast of characters? No

Flaws of characters a main focus? No

Full disclosure, I read this purely because of Good Omens brainrot. Because, well, it's titled "No Nightingales" and set in Berkeley Square. While reading it, I discovered it's a comedy about two gay-coded male ghosts in their haunted house witnessing the outskirts of British history, so maybe the connection isn't even that arbitrary.

The story itself is rather pointless and I'm sure I missed a lot of jokes and references, most of the others I had to look up on Wikipedia anyway.

But I really liked the kind of humour of the whole book: "'Am I in favour of Votes for Women?' asked the Prime Minister. 'Yes and no. [...] There is a time and place for everything, and I submit it to you that the time to discuss this question is not ripe.'

But the tomato was."

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jean Simmons.

Filmografía

- Sports Day (1944)

- Give Us the Moon (1944), de Val Guest y Caryl Brahms.

- Mr. Emmanuel (1944)

- Kiss the Bride Goodbye (1945), de Paul L. Stein.

- Meet Sexton Blake (1945), de John Harlow

- The Way to the Stars (1945)

- César y Cleopatra (Caesar and Cleopatra) (1946) de Gabriel Pascal

- Cadenas rotas (Great Expectations) (1946), de David Lean.

- The Woman in the Hall (1947)

- Uncle Silas (1947), de Charles Frank

- Narciso negro (Black Narcissus) (1947) de Michael Powell y Emeric Pressburger.

- Hungry Hill (1947), de Brian Desmond Hurst

- Hamlet (Hamlet) (1948), de Laurence Olivier.

- La isla perdida (The Blue Lagoon) (1949) de Frank Launder.

- Adán y...ella (Adam and Evelyne) (1949) de Harold French.

- Extraño suceso (So Long at the Fair) (1950), de Antony Darnborough y Terence Fisher.

- Coacción (Cage of Gold) (1950), de Basil Dearden.

- El torbellino de la vida (Trio) (1950), de Ken Annakin.

- Trágica obsesión (The Clouded Yellow) (1951), de Ralph Thomas.

- Androcles y el león (Androcles and the Lion) (1952) de Chester Erskine.

- Cara de ángel (Angel Face) (1953) de Otto Preminger.

- La reina virgen (Young Bess) (1953) de George Sidney

- Entre dos mujeres (Affair with a Stranger) (1953), de Roy Rowland.

- La túnica sagrada (The Robe) (1953) de Henry Koster.

- La actriz (The Actress) (1953), de George Cukor.

- Guapa pero peligrosa (She Couldn't Say No) (1954), de Lloyd Bacon

- Sinuhé, el egipcio (The Egyptian) (1954) de Michael Curtiz.

- Demetrio y los gladiadores (Demetrius and the Gladiators) (1954), de Delmer Daves.

- Una bala en camino (A Bullet Is Waiting) (1954), de John Farrow.

- Desirée (Desireé) (1954) de Henry Koster.

- Pasos en la niebla (Footsteps in the Fog) (1955) de Arthur Lubin.

- Ellos y ellas (Guys and Dolls) (1955) de Joseph L. Mankiewicz.

- Hilda Crane (1956), de Philip Dunne

- This Could Be the Night (1957), de Robert Wise.

- Mujeres culpables (Until They Sail) (1957), de Robert Wise.

- Horizontes de grandeza (The Big Country) (1958), de William Wyler.

- Después de la oscuridad (Home Before Dark) (1958), de Mervyn LeRoy.

- Esta tierra es mía (This Earth Is Mine) (1959) de Henry King.

- El fuego y la palabra (Elmer Gantry) (1960), de Richard Brooks.

- Espartaco (Spartacus) (1960), de Stanley Kubrick.

- Página en blanco (The Grass Is Greener) (1960) de Stanley Donen.

- All the Way Home (1963), de Alex Segal

- Vivir en la cumbre (Life at the Top) (1965), de Ted Kotcheff.

- La mujer sin rostro (Mister Buddwing, 1966), de Delbert Mann.

- El novio de mi mujer (Divorce American Style) (1967), de Bud Yorkin.

- Noche de titanes (Rough Night in Jericho) (1967),de Arnold Laven.

- Heidi (1968)

- Con los ojos cerrados (The Happy Ending) (1969), de Richard Brooks.

- El joven y la cuarentona (Say Hello to Yesterday) (1971),de Alvin Rakoff.

- Mr. Sycamore (1975), de Pancho Kohner.

- Dominique (Dominique) (1978), de Michael Anderson.

- La maldición de los Dain (The Dain Curse) (1978), de E.W. Swackhamer.

- Sensibilidad y sentido (Sensibility and Sense) (1978), de David Hugh Jones.

- Conducta confidencial (Yellow Pages) (1988), de James Kenelm Clarke.

- Reencuentros (Angel Falls) (1993), de Joyce Chopra.

- Donde reside el amor (How to Make an American Quilt), de Jocelyn Moorhouse.

- Con su propia ley (1998) (Her Own Rules) de Bobby Roth.

- Final Fantasy: La fuerza interior (2001) (Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within), de Hironobu Sakaguchi (voz).

- Jean Simmons: Rose of England (2004) (documental)

- El castillo ambulante (Hauru no ugoku shiro) (2004), de Hayao Miyazaki (voz)..

Premios y nominaciones

Óscar

- 1948 Mejor Actriz de Reparto Hamlet Candidata

- 1969 Mejor Actriz Con los ojos cerrados Candidata

Emmy

- 1983 Primetime Emmy a la mejor actriz de reparto - Miniserie o telefilme El pájaro espino TV Film Ganadora

- 1989 Primetime Emmy a la mejor actriz de reparto - Miniserie o telefilme Se ha escrito un crimen Espejito, Espejito Mágico 1ª Parte Temporada 5/21 Nominada.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Simmons

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

The book I am currently reading

The Invention of Jane Harrison by Mary Beard. I’m fascinated by Hope Mirrlees, and her relationship with Jane Harrison was one of the ingredients of her life. They collaborated on a book of translated Russian tales, and Harrison’s theories seem integral both to Paris, Mirrlees’s modernist poem and to Lud-in-the-Mist. I’m loving watching Mary Beard deconstruct and re-examine ideas about what biography is in this short but brilliant book. Also Pandora’s Jar: Women in the Greek Myths by Natalie Haynes. I’m reading it slowly and with delight, an essay at a time, rejoicing in the easy erudition and the way she upends what I thought I knew and gives me something much more interesting in its place.

The book that changed my life

The Book of the New Sun by Gene Wolfe. It’s brilliant, much more brilliant than I knew when I read it for the first time. I would not be the writer I am without Wolfe’s friendship, or without taking his lesson that you should write to be reread with increased pleasure by a smart reader.

The book I wish I’d written

Lud-in-the-Mist by Hope Mirrlees. It’s the great English fantasy novel, about the prosaic land next to the wilderness of Faerie. It’s a history and a murder mystery, and it’s about family and dissatisfaction, and about fairy fruit, which, as with all good fantasy, stands both for itself and for poetry, and sexuality, and the things that leave us changed forever.

The last book that made me laugh

Round the Horne Scripts by Marty Feldman and Barry Took. Où sont les neiges d’antan, Mr Horne? That’s your actual philosophical French.

The book that influenced my writing

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by CS Lewis. I read it when I was six, and fell in love with Narnia and with the magical story and most of all with the auctorial voice. Lewis seemed to be having a wonderful time writing, confiding in and treating the readers as if they were smart friends. It was the first time I was ever aware that there was a person behind the words. It made me want to write. It made me want to do that magic trick.

The last book that made me cry

Reading Diana Wynne Jones’s Dogsbody to my daughter Maddy, some 15 years ago. I got to the book’s end and we both had very wet faces.

The book I couldn’t finish

Titania Has a Mother by Caryl Brahms and SJ Simon. I love much of their work, so was thrilled recently to find a book of theirs I didn’t know about. And a fairytale book at that. Let’s just say it was of its time and hadn’t aged well.

The book I’m ashamed not to have read

Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. I’ve read extracts from it and loved them. It’s a novel I approve of and keep meaning to read. I just haven’t read it.

The book I give as a gift

A Humument by Tom Phillips. A Victorian novel, with pages painted over and into, messages and thoughts revealed and illuminated. It was always the book I gave people, hoping that even a few of them would read it and delight in it as I do.

The book I’d most like to be remembered for

You don’t get to choose. Probably, you don’t get to be remembered, either. But most of my favourite authors are now unfashionable and forgotten, and I’d be happy to join their company, if every now and again someone found one of my books in a dusty pile and took comfort in it.

My earliest reading memory

A book about a little mermaid looking for other mermaids, and the inside front cover art from a Noddy book.

My comfort read

Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light feels like a place I can go where the people know me and will have to take me in, in a novel of people become gods.

*********

To send books to the NoCo Book Box Supporters Club, please use one of our Wishlists:

Left-Bank Books, STL

EyeSeeMe Children's Bookstore, STL

BookShop

Amazon

Feel free to order used books whenever possible! Off The Shelf STL and BetterWorldBooks are two of my favorite Amazon MarketPlace sellers for used books.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

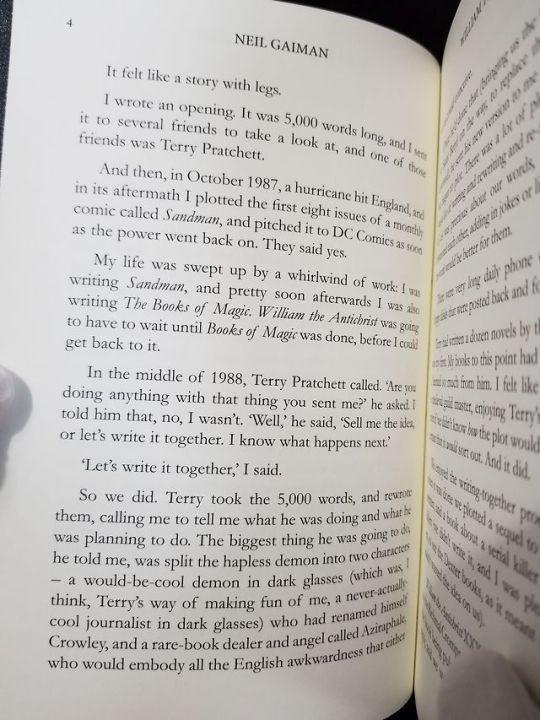

There was some interest in the introduction to the William the Antichrist book that came with the Ineffable Edition of the Definitive Good Omens, so here are the pictures of that. As with the rest of my posts on the book’s contents, I’ve provided a transcript below the cut.

I was twenty-six. I had just finished writing Don’t Panic!

The Hitchhiker’s guide to the Galaxy Companion. There was something comfortable about the style I was writing it in: I wasn’t trying to pastiche Douglas Adams, but I was trying to write in a style I thought of as ‘classic English humour’ – P. G. Wodehouse was in there, and so were Alan Coren, Richmal Crompton and Stella Gibbons, Caryl Brahms and S.J. Simon, and many others. And by the end of the book, in the spring of 1987, I felt comfortable writing in that style.

In the summer of 1987, several odd ideas came together: the film The Omen; a scene in Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta; Richmal Crompton’s Just William books. I found myself imagining a book called William the Antichrist, in which a hapless demon was going to be responsible for swapping the wrong baby over, and the son of the US Ambassador would be completely undemonic, while William Brown would grow up to be the Antichrist, and the demon would need to stop him ending the world. The unfortunate demon, whom I called Crawleigh, because Crawley was a nearby town with an unfortunate name, would have to sort it all out as best he could.

It felt like a story with legs.

I wrote an opening. It was 5,000 words long, and I sent it to several friends to take a look at, and one of those friends was Terry Pratchett.

And then, in October 1987, a hurricane hit England, and in its aftermath I plotted the first eight issues of a monthly comic called Sandman, and pitched it to DC Comics as soon as the power went back on. They said yes.

My life was swept up by a whirlwind of work: I was writing Sandman, and pretty soon afterwards I was also writing The Books of Magic. William the Antichrist was going to have to wait until The Books of Magic was done, before I could get back to it.

In the middle of 1988, Terry Pratchett called. ‘Are you doing anything with that thing you sent me?’ he asked. l told him that, no, I wasn’t. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘Sell me the idea, or let’s write it together. I know what happens next.’

‘Let’s write it together,’ I said.

So we did. Terry took the 5,000 words, and rewrote them, calling me to tell me what he was doing and what he was planning to do. The biggest thing he was going to do, he told me, was split the hapless demon into two characters – a would-be-cool demon in dark glasses (which was, I think, Terry’s way of making fun of me, a never-actually- cool journalist in dark glasses) who had renamed himself Crowley, and a rare-book dealer and angel called Aziraphale, who would embody all the English awkwardness that either

of us could conceive.

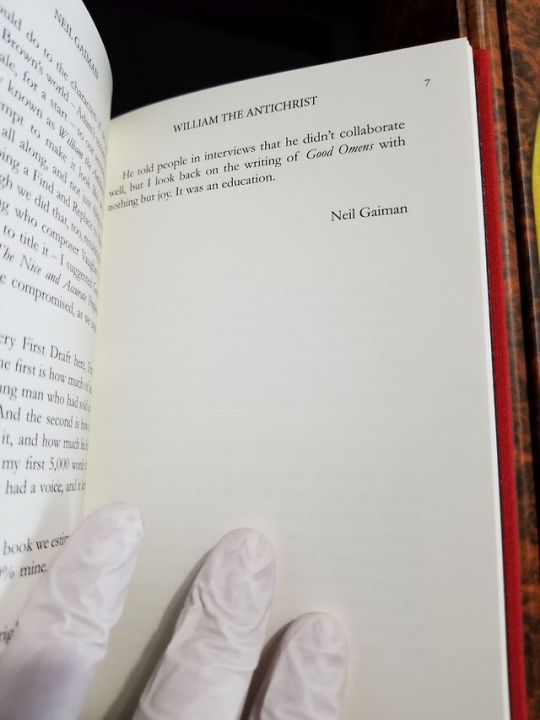

Once he‘d done that (bringing us the Chattering Order of Saint Beryl on the way, to replace the nurses that I’d invented) he sent his new version to me to read, and then we began to plot. There was a lot of plotting. And there was a lot of writing and rewriting and re-rewriting. Neither of us was precious about our words, so we cheerfully footnoted each other, adding in jokes or lines if we thought the work would be better for them.

There were very long daily phone calls. There were floppy disks that were posted back and forth weekly.

Terry had written a dozen novels by that point, but this was my first. My books to this point had been non-fiction. I learned so much from him. I felt like an apprentice to a medieval guild master, enjoying Terry’s confidence that, even if we didn’t know how the plot would sort out, we were certain that it would sort out. And it did.

We enjoyed the writing-together process, enough that when it was done we plotted a sequel to the book we had written, and a book about a serial killer who killed serial killers (we didn’t write it, and I was pleased, some years on, to see the Dexter books, as it meant that the Universe hadn’t wasted the idea on us).

William the Antichrist XXX being finished, we reached out to the Richmal Crompton estate to see if they’d countenance the book being published with their characters. They didn’t reply, and we were already talking about some of the fun

things we could do to the characters if we weren’t stuck with William Brown’s world – Adam’s second in command could be female, for a start – so our second draft of the book formerly known as William the Antichrist, which was mostly an attempt to make it look like we knew what we were doing all along, and not just filing off the serial numbers and doing a Find and Replace to change William to Adam (although we did that, too, resulting in Gollancz’s copy editor asking who composer Vaughan Adams was). Then we just had to title it – I suggested Good Omens, and Terry suggested The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch, so we compromised, as we usually did, and used both of them.

Rereading my Very First Draft here, I’m struck by a number of things. The first is how much of an early pencil sketch it was by a young man who had sold at most half a dozen short stories. And the second is how much Terry, wisely, changed about it, and how much he left the same. Once he had changed my first 5,000 words into our first 10,000 words, the book had a voice, and it kept that voice until the end.

When we finished the book we estimated that the words were 60% Terry’s and 40% mine, and the plot, such as it was, was entirely ours.

Nobody has seen this original opening before. Not since I sent it to half a dozen friends in 1987, anyway.

I’m so glad one of them was Terry.

He told people in interviews that he didn’t collaborate well, but I look back on the writing of Good Omens with nothing but joy. It was an education.

Neil Gaiman

#good omens#Definitive Good Omens#ineffable edition#william the antichrist#williamtheantichrist#transcript#sIp

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the World's a Stage

(books about theatre)

John Arden, Books of Bale

Beryl Bainbridge, An Awfully Big Adventure

Richard Bissell, Say, Darling

Caryl Brahms and S.J. Simon, A Bullet in the Ballet

Angela Carter, Wise Children

Robertson Davies, Tempest-Tost

Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby

Bamber Gascoigne, The Heyday

H.R.F. Keating, Death of a Fat God

Thomas Keneally, The Playmaker

Noel Langley, There's a Porpoise Close Behind Us

J.B. Priestley, The Good Companions

Mary Renault, The Mask of Apollo

Barry Unsworth, Morality Play

#THEMES#ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE#ARDEN_John#BAINBRIDGE_Beryl#BISSELL_Richard#BRAHMS_Caryl#CARTER_Angela#DAVIES_Robertson#DICKENS_Charles#GASCOIGNE_Bamber#KEATING_HRF#KENEALLY_Thomas#LANGLEY_Noel#PRIESTLEY_JB#RENAULT_Mary#UNSWORTH_Barry

0 notes

Text

Girl Stroke Boy (1971) - Classic Movie Review 9340

Girl Stroke Boy (1971) – Classic Movie Review 9340

Director Bob Kellett’s 1971 comedy Girl Stroke Boy is an excruciatingly unfunny, ultra-tacky and tasteless ‘adult’ comedy written by the normally tasteful Ned Sherrin and Caryl Brahms, both of whom should have known better.

It is based on David Percival’s stage play Girlfriend about elderly, posh, conservative parents Lettice and George Mason (played by Joan Greenwood and Michael Hordern) who…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Today's #1000BooksToReadBeforeYouDie is a screwball-comedy murder mystery from 1937: "A Bullet in the Ballet" by Caryl Brahms and S. J. Simon. I'm a big fan of whodunits from the so-called Golden Age of Mysteries (Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen, Philo Vance, Mr. and Mrs. North, et al), but I'd never heard of this one. I can't wait to, um, Chasse this one down. (A little ballet humor to start off your day). Read: 31 To-Be-Read: 78 https://www.instagram.com/p/Btv-JMDHdnY/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1w6m7s1nuqziu

0 notes

Text

Adam Quill in Envoy on Excursion

'Alone in the dark Quill listened to the grisly ticking of the alarm-clock. He felt horrible. It seemed to him that he must be looking exactly like the hero on the jacket of a ten-cent pulp. Only these heroes always got themselves rescued. … Nothing for it but to die. He hoped he would die like an Englishman. With calm. Well it had been a good life. Scotland Yard. The Stroganoff Ballet. And the girl behind the tobacco kiosk. It was a pity perhaps that he had never solved a case, but it was too late to bother about that now. … The pounding of blood in Quill's ears sounded exactly like distant footsteps. God it was footsteps! They were coming closer. “Help!” yelled Quill, forgetting to die like an Englishman. “Help!”'

Caryl Brahms & S.J. Simon, Envoy on Excursion (1939)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

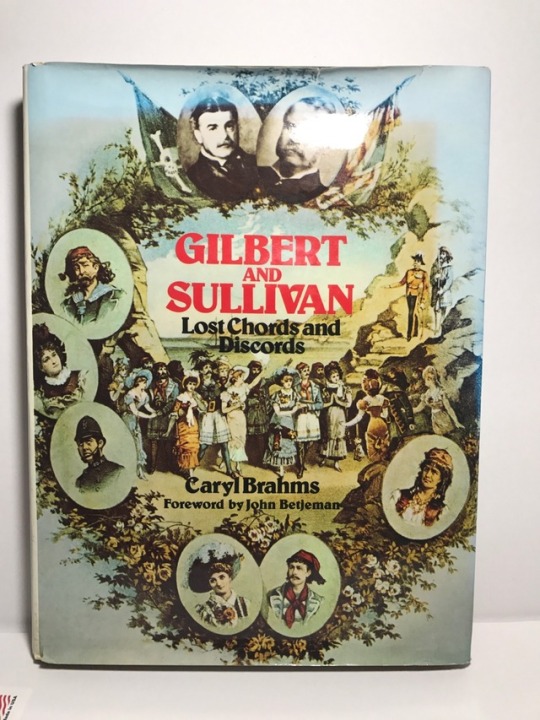

Look at this on eBay: https://www.ebay.com/itm/232302807089 Gilbert And Sullivan Lost Chords and Discords - Caryl Brahms 1975

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Don't, Mr Disraeli. Caryl Brahms. S J Simon. A Vintage Ladybird Book 715. 1949

Set in Victorian England and featuring everyone you would expect from this era plus The Marx Brothers! Don't Mr Disraeli is a melodramatic version of the Romeo and Juliet theme, with the addition of a stage villain, all twirling mustachios.

About

Originally published in 1940, this copy is a a first publication from Penguin in 1949. The iconic orange banded Penguin cover shows the original price of 1/6.

Condition

Very good condition. All the pages are good, clean and intact thanks to a very good binding, It has the feel of never being read. The cover and reverse are very good with just very minor wear. The spine is darker as you find with these penguin books of this era (maybe the original glue used? If you know PLEASE let me know!) and shows just minimum wear so please see the photographs.

0 notes

Text

Sir John Hurt obituary

British actor became an overnight sensation after playing Quentin Crisp in the 1975 television film The Naked Civil Servant

Few British actors of recent years have been held in as much affection as Sir John Hurt, who has died aged 77. That affection is not just because of his unruly lifestyle he was a hell-raising chum of Oliver Reed, Peter OToole and Richard Harris, and was married four times or even his string of performances as damaged, frail or vulnerable characters, though that was certainly a factor. There was something about his innocence, open-heartedness and his beautiful speaking voice that made him instantly attractive.

As he aged, his face developed more creases and folds than the old map of the Indies, inviting comparisons with the famous lived-in faces of WH Auden and Samuel Beckett, in whose reminiscent Krapps Last Tape he gave a definitive solo performance towards the end of his career. One critic said he could pack a whole emotional universe into the twitch of an eyebrow, a sardonic slackening of the mouth. Hurt himself said: What I am now, the man, the actor, is a blend of all that has happened.

For theatregoers of my generation, his pulverising, hysterically funny performance as Malcolm Scrawdyke, leader of the Party of Dynamic Erection at a Yorkshire art college, in David Halliwells Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs, was a totemic performance of the mid-1960s; another was David Warners Hamlet, and both actors appeared in the 1974 film version of Little Malcolm. The play lasted only two weeks at the Garrick Theatre (I saw the final Saturday matine), but Hurts performance was already a minor cult, and one collected by the Beatles and Laurence Olivier.

He became an overnight sensation with the public at large as Quentin Crisp the self-confessed stately homo of England in the 1975 television film The Naked Civil Servant, directed by Jack Gold, playing the outrageous, original and defiant aesthete whom Hurt had first encountered as a nude model in his painting classes at St Martins School of Art, before he trained as an actor.

Crisp called Hurt my representative here on Earth, ironically claiming a divinity at odds with his low-life louche-ness and poverty. But Hurt, a radiant vision of ginger quiffs and curls, with a voice kippered in gin and as studiously inflected as a deadpan mix of Nol Coward, Coral Browne and Julian Clary, in a way propelled Crisp to the stars, and certainly to his transatlantic fame, a journey summarised when Hurt recapped Crisps life in An Englishman in New York (2009), 10 years after his death.

Hurt said some people had advised him that playing Crisp would end his career. Instead, it made everything possible. Within five years he had appeared in four of the most extraordinary films of the late 1970s: Ridley Scotts Alien (1979), the brilliantly acted sci-fi horror movie in which Hurt from whose stomach the creature exploded was the first victim; Alan Parkers Midnight Express, for which he won his first Bafta award as a drug-addicted convict in a Turkish torture prison; Michael Ciminos controversial western Heavens Gate (1980), now a cult classic in its fully restored format; and David Lynchs The Elephant Man (1980), with Anthony Hopkins and Anne Bancroft.

In the latter, as John Merrick, the deformed circus attraction who becomes a celebrity in Victorian society and medicine, Hurt won a second Bafta award and Lynchs opinion that he was the greatest actor in the world. He infused a hideous outer appearance there were 27 moving pieces in his face mask; he spent nine hours a day in make-up with a deeply moving, humane quality. He followed up with a small role Jesus in Mel Brookss History of the World: Part 1 (1981), the movie where the waiter at the Last Supper says, Are you all together, or is it separate cheques?

Hurt was an actor freed of all convention in his choice of roles, and he lived his life accordingly. Born in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, he was the youngest of three children of a Church of England vicar and mathematician, the Reverend Arnould Herbert Hurt, and his wife, Phyllis (ne Massey), an engineer with an enthusiasm for amateur dramatics.

After a miserable schooling at St Michaels in Sevenoaks, Kent (where he said he was sexually abused), and the Lincoln grammar school (where he played Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest), he rebelled as an art student, first at the Grimsby art school where, in 1959, he won a scholarship to St Martins, before training at Rada for two years in 1960.

He made a stage debut that same year with the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Arts, playing a semi-psychotic teenage thug in Fred Watsons Infanticide in the House of Fred Ginger and then joined the cast of Arnold Weskers national service play, Chips With Everything, at the Vaudeville. Still at the Arts, he was Len in Harold Pinters The Dwarfs (1963) before playing the title role in John Wilsons Hamp (1964) at the Edinburgh Festival, where critic Caryl Brahms noted his unusual ability and blessed quality of simplicity.

This was a more relaxed, free-spirited time in the theatre. Hurt recalled rehearsing with Pinter when silver salvers stacked with gins and tonics, ice and lemon, would arrive at 11.30 each morning as part of the stage management routine. On receiving a rude notice from the distinguished Daily Mail critic Peter Lewis, he wrote, Dear Mr Lewis, Whooooops! Yours sincerely, John Hurt and received the reply, Dear Mr Hurt, thank you for short but tedious letter. Yours sincerely, Peter Lewis.

After Little Malcolm, he played leading roles with the RSC at the Aldwych notably in David Mercers Belchers Luck (1966) and as the madcap dadaist Tristan Tzara in Tom Stoppards Travesties (1974) as well as Octavius in Shaws Man and Superman in Dublin in 1969 and an important 1972 revival of Pinters The Caretaker at the Mermaid. But his stage work over the next 10 years was virtually non-existent as he followed The Naked Civil Servant with another pyrotechnical television performance as Caligula in I, Claudius; Raskolnikov in Dostoevskys Crime and Punishment and the Fool to Oliviers King Lear in Michael Elliotts 1983 television film.

His first big movie had been Fred Zinnemanns A Man for All Seasons (1966) with Paul Scofield (Hurt played Richard Rich) but his first big screen performance was an unforgettable Timothy Evans, the innocent framed victim in Richard Fleischers 10 Rillington Place (1970), with Richard Attenborough as the sinister landlord and killer John Christie. He claimed to have made 150 movies and persisted in playing those he called the unloved people like us, the inside-out people, who live their lives as an experiment, not as a formula. Even his Ben Gunn-like professor in Steven Spielbergs Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) fitted into this category, though not as resoundingly, perhaps, as his quivering Winston Smith in Michael Radfords terrific Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984); or as a prissy weakling, Stephen Ward, in Michael Caton-Joness Scandal (1989) about the Profumo affair; or again as the lonely writer Giles DeAth in Richard Kwietniowskis Love and Death on Long Island.

His later, sporadic theatre performances included a wonderful Trigorin in Chekhovs The Seagull at the Lyric, Hammersmith, in 1985 (with Natasha Richardson as Nina); Turgenevs incandescent idler Rakitin in a 1994 West End production by Bill Bryden of A Month in the Country, playing a superb duet with Helen Mirrens Natalya Petrovna; and another memorable match with Penelope Wilton in Brian Friels exquisite 70-minute doodle Afterplay (2002), in which two lonely Chekhov characters Andrei from Three Sisters, Sonya from Uncle Vanya find mutual consolation in a Moscow caf in the 1920s. The play originated, like his Krapp, at the Gate Theatre in Dublin.

His last screen work included, in the Harry Potter franchise, the first, Harry Potter and the Philosophers Stone (2001), and last two, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Parts One and Two (2010, 2011), as the kindly wand-maker Mr Ollivander; Roland Joffs 1960s remake of Brighton Rock (2010); and the 50th anniversary television edition of Dr Who (2013), playing a forgotten incarnation of the title character.

Because of his distinctive, virtuosic vocal attributes was that what a brandy-injected fruitcake sounds like, or peanut butter spread thickly with a serrated knife? he was always in demand for voiceover gigs in animated movies: the heroic rabbit leader, Hazel, in Watership Down (1978), Aragorn/Strider in Lord of the Rings (1978) and the Narrator in Lars von Triers Dogville (2004). In 2015 he took the Peter OToole stage role in Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell for BBC Radio 4. He had foresworn alcohol for a few years not for health reasons, he said, but because he was bored with it.

Hurts sister was a teacher in Australia, his brother a convert to Roman Catholicism and a monk and writer. After his first short marriage to the actor Annette Robinson (1960, divorced 1962) he lived for 15 years in London with the French model Marie-Lise Volpeliere Pierrot. She was killed in a riding accident in 1983. In 1984 he married, secondly, a Texan, Donna Peacock (divorced in 1990), living with her for a time in Nairobi until the relationship came under strain from his drinking and her dalliance with a gardener. With his third wife, Jo Dalton (married in 1990, divorced 1995), he had two sons, Nicolas and Alexander (Sasha), who survive him, as does his fourth wife, the actor and producer Anwen Rees-Myers, whom he married in 2005 and with whom he lived in Cromer, Norfolk. Hurt was made CBE in 2004, given a Bafta lifetime achievement award in 2012 and knighted in the New Years honours list of 2015.

John Vincent Hurt, actor, born 22 January 1940, died 27 January 2017

Read more: http://ift.tt/2kDFeJt

from Sir John Hurt obituary

0 notes

Text

Edinburgh > | John Hurt obituary | Film

...Hamp (1964) at the Edinburgh Festival, where critic Caryl Brahms...

http://ift.tt/2kDFeJt

0 notes