#ishmael reed

Text

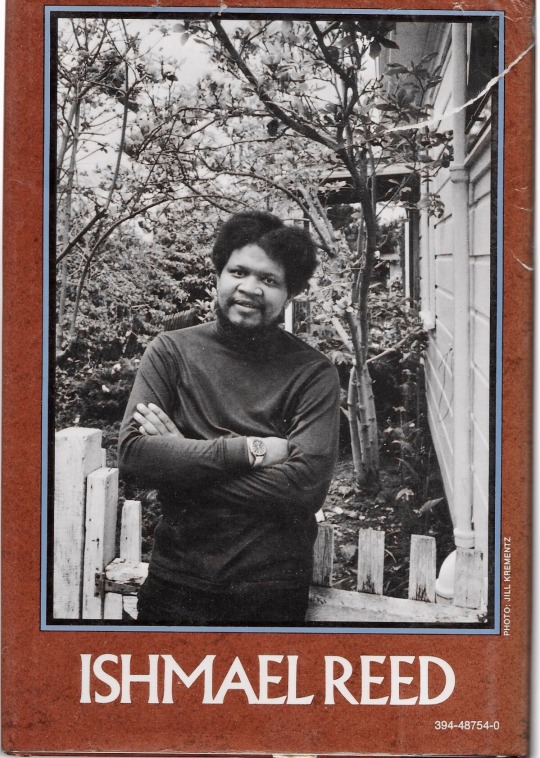

Ishmael Reed

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

He doesn't mind the shape of the idol: sexuality, economics, whatever, as long as it is limited to 1.

from Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

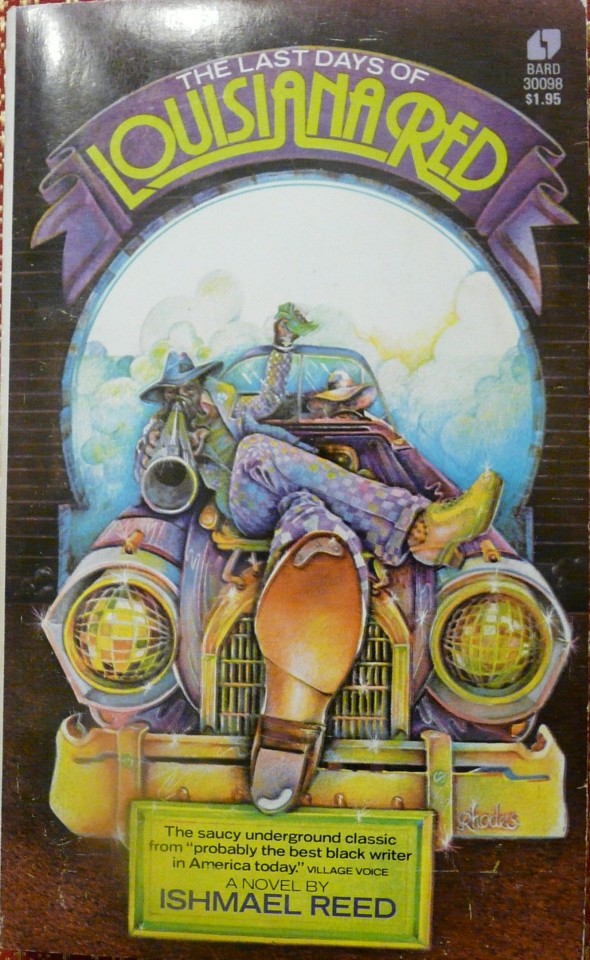

Book Review

The Last Days of Louisiana Red by Ishmael Reed

There is a chapter in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra portraying a tightrope walker. The tightrope walk is an attempt the man makes to leave the commonplace behind, to explore new possibilities, to see new lands, to expand the parameters of life, to move on to something better...a higher state of existence. However, below the tightrope is the audience, made up of the masses of the narrow-minded, the simple folk, the ordinary citizens, the littlepeople, the flies of the marketplace as Nietzsche calls them. They aspire towards nothing but mediocrity and the maintenance of the status quo. These people resent the tightrope walker’s attempt at finding a new way of life, so halfway through the stunt, they pull him down from the rope so that he dies in the fall.

Ishmael Reed, in his novel The Last Days of Louisiana Red, transplants this dilemma to a different context. He applies it to the African-American community in Oakland during the 1970s where the politics of the New Left, Black Power, and the feminist movement are in full swing. I don’t know if Reed consciously borrowed the allegory of the tightrope walker from Nietzsche or not (probably not), but it does serve as a legitimate point of comparison. Ed Yellings, the businessman who starts the Gumbo Works business, can easily replace the tightrope walker; Ed Yellings gets murdered early in the book, but as it is, he stands in for the upwardly mobile element of the African-American community in the post Civil Rights Movement era. He represents the builders and founders of an African-American economic class that is self-deterministic and independent of white America. And s the envious mediocrities of Nietzsche’s town, the ones who kill the tightrope walker, correspond to the Moochers, Reed’s portrayal of the radicals and activists, some of which come from privileged backgrounds, who refuse to build a better society and instead insist on simultaneously destroying the society that exists while demanding that everything be given to them because they are an oppressed minority. This conflict might sound shocking to younger readers who weren’t alive in the 1970s, especially considering it is being articulated by Ishmael Reed, an African-American author, but he is addressing a real social problem with detrimental consequences in the real world.

Ed Yellings’ Gumbo Works is an instant success. The gumbo is sold in a restaurant and manufactured in a factory but little is said about these establishments. This lack of detail is, I think, one of the many flaws in the novel. The business is actually a front for a secret voodoo operation which involves the defeat of Louisiana Red who is not actually a character but more like a spirit of sorts that brings negative energy into the African-American community. Ed Yellings becomes a millionaire and raises a family of four children in a mansion. Wolf grows up to be a business man, following in his father’s footsteps in preparation to take over the company. Street is a Black Power-type radical and criminal who is obviously a caricature of Eldridge Cleaver. The passage about Street committing murder then fleeing to Algeria where he is given a villa free of charge by the government is lifted directly from that Black Panther Party leader’s life. Sister barely figures into the story but probably represents the Back to Africa ideal of the 1970s since her clothes are African-inspired and she associates with a Nigerian friend. Minnie is the one who plays the most prominent role in the story. Based on Cab Calloway’s classic jive anthem “Minnie the Moocher”, she is a prominent member of the Moochers, but she falls out of favor with them because she shows up at rallies to give speeches about ontology and epistemology and other pseudo-intellectual crap that puts people to sleep. She represents the feminist element of the radical Left and insists she is entitled to take over Gumbo Works even though she has no knowledge of business. The inclusion of all these representatives in one family is of symbolic importance. Not only do African-American people bond by colloquially referring to each other as Sister and Brother, but but the idea of the community as an extension of the family makes Reed’s whole point more clear. He is depicting the African-American community as a family which is supposed to be closely knit and supportive of each other despite their individual differences yet at the same time he is showing how this family is one that is dysfunctional.

Ed Yellings gets assassinated, his factory gets burned down, and the two brothers shoot each other while Minnie insists that she inherit everything her father left behind. This is not the way families are supposed to work.

So far it sounds like a lot of interesting and legitimate ideas are introduced into the story. And it is true, a lot of them are interesting and legitimate and there is an abundance of them. A lot of them barely go anywhere after being introduced though. Sister is the easiest example of this as she only makes two brief appearances and doesn’t contribute in any significant way to anything that happens. Street and Wolf are not developed much more as characters either. Street’s only purpose in the book seems to be for the sake of mocking Eldridge Cleaver without mentioning him by name. Some of the supporting characters actually do a lot more than the main members of the family. Nanny, a woman from Louisiana, gets hired to raise the family but her ulterior motive is to groom Minnie for the sake of disrupting Gumbo Works. Nanny is a representation of the old, southern African-American way of life that the urban professional class wants to leave behind. She is actually a practitioner of voodoo and intends to spread the chaos of Louisiana Red through the Oakland Black community.

Nanny’s opposition is Papa LaBas, a houngan who is brought in to replace Ed Yellings as head of the Gumbo Works corporation. The two are engaged in a magical combat that is an updated version of the voodoo war between Doc John and Marie Laveau. The history and folklore surrounding those two legendary figures from New Orleans is sufficiently explained in one chapter. You might remember Papa LaBas as a catalyst of the action in Ishmael Reed’s previous, and far superior novel, Mumbo Jumbo. Aside from running the company, his most memorable part is when he gives Minnie a marsh and misogynistic lecture about how Black women should stay in their traditional places. His twisted logic is that women are already powerful because they provide men with sex, something which makes men obedient and submissive. I suppose that line of reasoning works if you are the type of sex-obsessed man who thinks with the wrong head, but for those of us with a more diverse range of interests, it comes off as a rather infantile view of sexuality and power.

The author’s misogyny is extreme, even by 1970s standards yet it is totally in line with what a lot of African-American men were thinking at that time. Black hyper-masculinity and sexual potency were big components of the Black Power movement and those were the progressives of their time. Read up on the Black Panther’s approach to women and sexuality if you don’t believe me. One Black Panther, I forget who, famously said, “The only place for Black women in the Revolution is on their backs.” The more conservative members of the Black community then, as represented in this story, were even more traditional and domineering in their approach to sex and gender politics.

By far, the most interesting characters are Kingfish and Elder, representatives of the lumpenproletariate who Reed despises. These two clownish characters refuse to work and survive by collecting welfare and committing petty crimes like stealing, burglary, scamming, and begging. They are obviously capable of being useful but refuse to indulge in thing like employment, instead paying for beer and weed by swiping tips off the tables in restaurants. “Owning a business is something that Black people don’t do,” says one of them. This is the type of attitude Ishmael Reed is addressing in this novel in an attempt at correcting it for the sake of his people. Kingfish and Elder stand out here because they are the most direct and clear criticism offered up by Reed and they work well as comic relief.

The least successful character is Chorus, a man who acts as the chorus of the story, explaining what is happening and what is yet to come. He provides counter-narratives about Isis and Osiris, the Egyptian deities, and Antigone, the Greek daughter of Oedipus. These plots correspond to what is happening with Minnie, Ed Yellings, and Papa LaBas. But the stories are confusing and poorly narrated. The purpose of a dramatic chorus is to clarify a story, but in this case Chorus muddles the narrative to the point where skipping these chapters might actually make the book easier to read.

I am wondering if this novel was originally intended to be a play written for theatrical production. The inclusion of Chorus, as well as a scene in a theater where Minnie heckles the performers (sound familiar Leftist millennial students at Berkeley?) are obvious references to the theater. But the whole story is told through dialogue the way a stage performance would be. Even the assassination, the shootings, and the fire at the factory are explained through conversation rather than shown as part of the narrative. This might have been conceived of as a play but written as a novel for some reason I can’t comprehend.

The aforementioned lack of detail is a real weakness. As previously mentioned, the violence and the fire are relayed to the audience by speech. There is also no description of the restaurant or the factory. Even worse, for a book about voodoo, it is disappointing that the actual rites and ceremonies are not described. Rather than having these things talked about in casual conversation, actually showing them visually bulks up the writing, fills in the blank spaces, and makes the story more complete. It allows the audience to experience these events emotionally and creates depth by drawing us into the environment and the action. If the characters only talk about these things than we just move on to the next page without really connecting with them in our imagination.

The other big problem is that Reed introduces too many ideas but never follows through on them. The different characters all represent different aspects of the African-American community but they are little more than hollow receptacles of ideas. What they symbolize is obvious but beyond the symbolism they have no life of their own. With such underdeveloped characters and themes, it is hard to tell if Ishmael Reed is being fair in his critique or not. You can find plenty of things to criticize in the Black bourgeoisie, the Back to Africa ideal, the gangster, the Black Power movement, and the feminists but there are a lot of things those people got right too. By not addressing all sides of these issues, the author does a disservice to his claims by making his criticism look shallow, uninformed, and rudimentary.

The Last Days of Louisiana Red is the follow up novel to Ishmael Reed’s most celebrated work Mumbo Jumbo, a novel that deserves all the praise it gets. The main idea of that book is that if white people stand back and give African-American people enough space then their culture will grow and thrive. I think the main idea of The Last Days of Louisiana Red is that, now that Black people have sufficient space to grow and thrive, they have to deal with some problems internal to the Black community. Notice how prominent a role the white people play in Mumbo Jumbo and how marginal the white people are in Louisiana Red. Reed has progressed to a new set of parameters here. But this latter novel is less successful because he introduces too much information into those parameters. It is like a chef making a pot of gumbo and using every ingredient he finds in the kitchen so that no individual flavor stands out and whatever is there in the pot doesn’t blend in with everything else. Reed could have left a lot of the content out to give more room for the important ideas to take hold or he could have expanded the novel to three times its length to fully develop everything he introduces. Otherwise, he does raise a legitimate issue, that of some members of the African-American community working against its greater interests. even if Some of his criticisms, particularly of feminism, are not entirely justified. I like to think that Reed is too good an author to write this kind of book since he certainly showed what he is capable of in Mumbo Jumbo, but in comparison this just ends up being another novel that doesn’t live up to its potential.

#book reviews#ishmael reed#vintage books#vintage paperbacks#african american fiction#postmodernism#american literature

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Fear stalks the land. (As usual; so what else is new?)

Ishmael Reed, Mumbo Jumbo

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

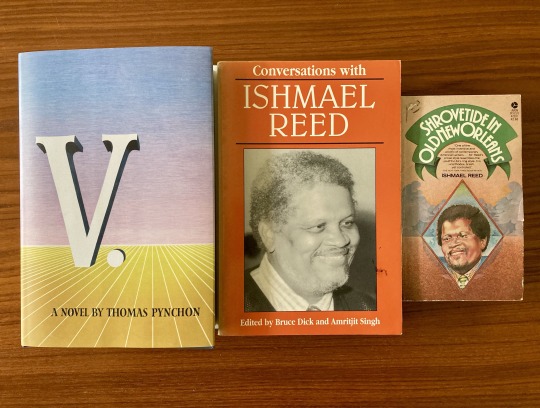

Three books (Books acquired, 8 June 2023)

I got a facsimile hardback sixtieth anniversary edition of Thomas Pynchon’s novel V. for my birthday. I also picked up two Ishmael Reed books: Conversations with Ishmael Reed and an Avon Bard edition of Shrovetide in Old New Orleans. Before I even physically picked up these last two, I knew that they formerly belonged to a guy from Perry, Florida and that a stamp with his name and address would…

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

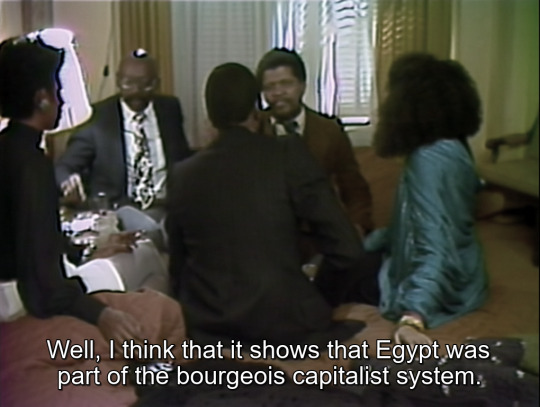

Personal Problems, Bill Gunn (1980)

#bill gunn#vertamae smart-grosvenor#robert polidori#walter cotton#ishmael reed#definitely a candidate for best US film of the 1980s

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

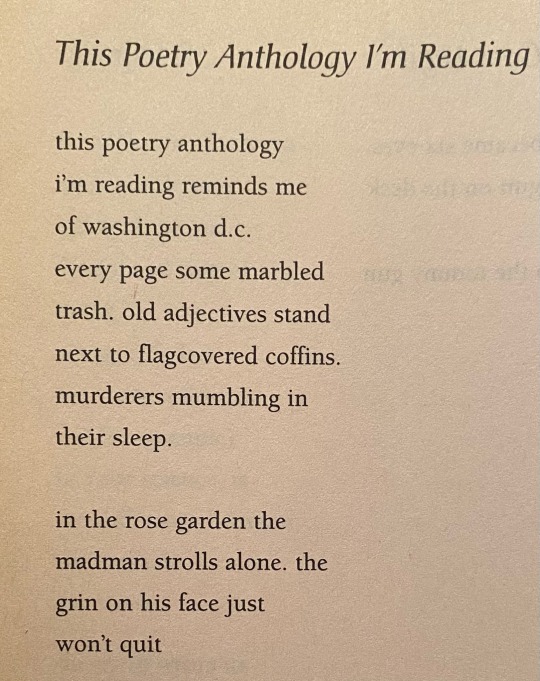

Ishmael Reed, “Eavesdropping on the Gods” from Why The Black Hole Sings the Blues

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

#african/black experience#culture#afrikan#Amiri Baraka#Ishmael Reed#HAKI Madhubuti#Black writers#Black Fire This Time: Volume 1

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ishmael Reed - Mumbo Jumbo - Doubleday - 1972

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ishmael Reed

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently read The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda by Ishmael Reed, thinking I was going to do a writeup on it. Then totally forgot to do a review! So here are my thoughts:

It’s a really interesting piece. It’s less like a proper play and more like an essay in the form of a play. It would likely be somewhat boring to watch in a theatre, since a lot of the monologues are closer to lecture. However, I really like that Reed published it in play format. Essays about race and history and the failures of various history books are many, as are critical analyses of theatrical pieces. But meeting the medium with the same medium, writing a critical analysis of a play (or musical, as it were) in the form of a play, is a cool technique. Even if something doesn’t work perfectly in its medium, sometimes why that medium was chosen is important. Reed is famous for satire, and this is an interesting blend of genuine education and satire; the satire comes mostly in the form of the white historical figures talking about/to each other, and in the way he writes the present-day figures like Rob Chernow and Lin-Manuel Miranda himself, while the monologues of the Black and indigenous historical characters are mostly educational.

The most important overarching critique in this piece, I think, is that history books, especially those written by white people, are selective both in who they decide to portray and from what angle, and will very often omit or gloss over individuals or incidences that might paint their subject in poor light. Reed writes Miranda as a clueless victim of this type of selective omission, which I find to be an interesting choice. The Miranda portrayed in this play used only Chernow’s book as a source for the musical, which means that all the individuals Chernow omitted from his book are ignored in Hamilton, or any prejudices or angles expressed in the book exist in the musical. I don’t know if that was the case in real life, if Lin-Manuel Miranda did any further research to make sure he wasn’t overlooking important people or information, but I think it’s actually a rather kind portrayal. I would be a bit shocked if he did no other research, and no one around him during the process, whether it was producers or dramaturgs or someone else, did any other research either. So writing him as cluelessly using only the one book as a source rather than choosing to ignore other sources seems like a moment of niceness, or perhaps it’s intended to be something more like condescension.

The basic plot is that Lin-Manuel Miranda, stressed out and unable to sleep, is given an Ambien by his agent, and dreams various historical figures coming to him, A Christmas Carol-style, to inform him of all the facts Rob Chernow left out of his book about Hamilton’s relationship to slavery. This includes slaves, indigenous people, (white) indentured servants, and Harriet Tubman.

Most of the monologues are essentially Reed filling in the historical gaps while criticizing Miranda for ignoring the documented plight of enslaved people, indigenous people, and others. But I really like the way he does this; allowing the named and unnamed Black and indigenous historical figures to be portrayed by living actors also gives them a way to be embodied while their history is explained. That’s why I think the vehicle of theatre is very cool: the monologues are, essentially, mini history lessons on the people whose stories Chernow’s history book (and therefore the musical) has forgotten or omitted, but by making them into monologues it allows that person to “tell” their own story through the actor and therefore connect more to an audience, rather than a reader just consuming it on a page in a nonfiction book. There’s a big emotional connection, a pathos that comes across more easily when watching a person speak about their (or “their”) experiences than when reading it as text in a book.

The monologues themselves were actually very eye-opening and interesting; some characters were based on real, named individuals enslaved by the Hamiltons/Schuylers, their relatives, or others in their social circle, and their monologues both explained historical contexts and told their individual stories. Others are anonymous characters portraying indigenous or enslaved people, and their monologues are more general, expressing broader historical experiences. This was a good vehicle for covering bigger picture and more detailed parts of history, I think.

Much of the criticism is about the Schuyler sisters rather than Hamilton himself, and their abuse of people they enslaved. I think Reed focuses on this because the sisters are portrayed as innocent and sweet, and he wanted to emphasize how much that was not the case, and how much they treated human beings like commodities they didn’t care about. But even through the Schuyler sisters, Reed criticizes Hamilton, because he points out over and over that when the sisters wanted something done, the men had to be the ones to put it in motion, meaning Hamilton and the other men in the sisters’ lives were just as complicit in their treatment of the enslaved.

There’s a moment in the middle of the piece where the anonymous indigenous character and one of the anonymous enslaved characters start fighting over, essentially, who was more oppressed by the colonizers. Eventually they’re interrupted when another character points out that this “divide and conquer” strategy is used by imperialists to pit them against each other and that they should be working together to support liberation from oppressors. I thought this was a nice touch because, along with the educational monologues from each character, it emphasizes the importance of mutual support in the face of oppression, and shows that the colonizers wanted that kind of fighting because it was/is an effective way to prevent people from joining together to push back as one and therefore become stronger as a group.

There’s a fair amount of criticism of Miranda’s poor writing, too, and the clumsy and sometimes uncreative rhymes in his raps, which I also appreciated. Not only that, but there’s also an important criticism of how little the actors and crew in these productions get paid compared to producers, backers, and Miranda himself. There’s also criticism of the ticket prices, which I was very happy to see. I was always frustrated by the prices being so high that only people with quite a lot of disposable income (who more than likely were white, especially in major cities where the show tickets were higher) and who probably weren’t going to question any of the show’s content, were the ones who were going to see the show, rather than poorer BIPOC who might have been in the intended audience. (Although tbh I do think the intended audience was white people who wouldn’t care enough to criticize the show.)

In the play, Miranda does go through an emotional arc and redemption; in another dream, he speaks to Alexander Hamilton and realizes that Hamilton is a racist and a slave-owner and not as wholesome as he thought, and Hamilton praises him for scrubbing his image clean via the musical so people think he’s a hero. In the end of the play (which is also the most heavily satirical) he attempts to confront Chernow about his book, but Chernow dismisses him. Miranda is offered a chance to write a musical about Columbus in the same vein as Hamilton, and refuses.

I think this is a piece that would do well as a reading, or done in the style of (and this is the first theatre production that comes to my head, I’m sure there are others) Les Miserables 25th anniversary concert, in which there are no sets (or a very simple one), but the costumed characters stand to speak their lines in front of microphones at the apron of the stage.

I also think a massive criticism that was missing (but I think is a complaint specifically in the theatre fan community and maybe less obvious outside of it) is that Lin-Manuel Miranda could have and should have written a musical about a historical figure or figures who were BIPOC if he was trying to have a primarily non-white cast. The fact that there are *so many* Black historical figures whose lives would make incredible pieces of musical theatre was completely ignored by Miranda in favor writing a show with a non-white cast portraying and smoothing over the history of colonization. He could have written about so many BIPOC historical figures, or events in American history that don’t get enough attention in school. Larger productions with casts of primarily non-white actors are few and far between in mainstream theatre, and telling their historical stories even more rare, and I think Reed should have pointed that out as well.

Overall I really liked this piece, but I think I understand why others might not understand it, as it’s written in a medium that seems odd for its long-winded style. But I think it’s attempting to meet Miranda in a similar medium, and I think to some extent even the long-winded-ness (which is still full of really good history and critique) is sort of a tongue-in-cheek way of showing how difficult it is to portray history in a way that allows for a person or people’s whole story to be told, while simultaneously saying “Look, if you omit the negative aspects of a person’s history, you are failing those who lived and died in oppression by scrubbing the historical figure’s image clean.” Many people who went to see the musical didn’t go on to do more research on Alexander Hamilton and learn about the things that were left out of this portrayal of him as a go-getter, dream-chaser, heroic figure. And anyone who was on social media spaces like Tumblr during the height of the Hamilton craze remembers how many people suddenly treated these real historical figures like adorable fictional characters who were innocent of wrong-doing, who they could attach various characteristics to in the same way people do to fictional characters in fanfiction etc.

I definitely enjoyed this play, and I think while it’s closer to a multi-voiced history lecture than a proper story with a full arc, I think the medium of theatre is a very cool way to criticize Hamilton and Lin-Manuel Miranda, and I really love the combination of satire and genuine historical education. It fills important gaps, gives often overlooked details, and tells the stories of people who still remain ignored or nameless in history. It takes the white historical figures down a peg and gives narrative control to the Black and Indigenous characters. The sheer amount of words spoken by Black and indigenous characters compared to white ones is a pretty big ratio, and I think it’s a subtle but powerful way to give their stories the focus. The satirical end that portrays the racism of Hamilton himself and the selectiveness of Chernow’s book, and also has Lin-Manuel Miranda himself learning a lesson and attempting to redeem himself is also I think a good touch; it doesn’t allow anyone to bow out uncriticized, and it is an obvious attempt to encourage the real life Lin-Manuel Miranda to look at his choices compared to the historical evidence, and the things he could do or say to try and undo some of the damage the musical has done to the memory of the enslaved and oppressed.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dance is the universal art, the common joy of expression. Those who cannot dance are imprisoned in their own ego and cannot live well with other people and the world. They have lost the tune of life. They only live in cold thinking. Their feelings are deeply repressed while they attach themselves forlornly to the earth.

from Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed (with added citation to The Dance: from Ritual to Rock and Roll, Ballet to Ballroom by Joost A.M. Meerloo)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Dance is the universal art, the common joy of expression. Those who cannot dance are imprisoned in their own ego and cannot live well with other people and the world. They have lost the tune of life. They only live in cold thinking. Their feelings are deeply repressed while they attach themselves forlornly to the earth.”

Ishmael Reed, Mumbo Jumbo: A Novel, 1972

0 notes

Quote

No one says a novel has to be one thing. It can be anything it wants to be, a vaudeville show, the six o’clock news, the mumblings of wild men saddled by demons.

Ishmael Reed, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's a nice new big fat interview with Ishmael Reed now up at The Collidescope

There’s a nice new big fat interview with Ishmael Reed now up at The Collidescope

There’s a nice new big fat interview with Ishmael Reed now up at The Collidescope. In the interview (conducted by George Salis), Reed discusses lots of stuff, including his love of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” (“one of the great short stories [by] the greatest of American white male writers for my money”), his contempt for David Simon’s The Wire, most of his novels, and his new…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes