Photo

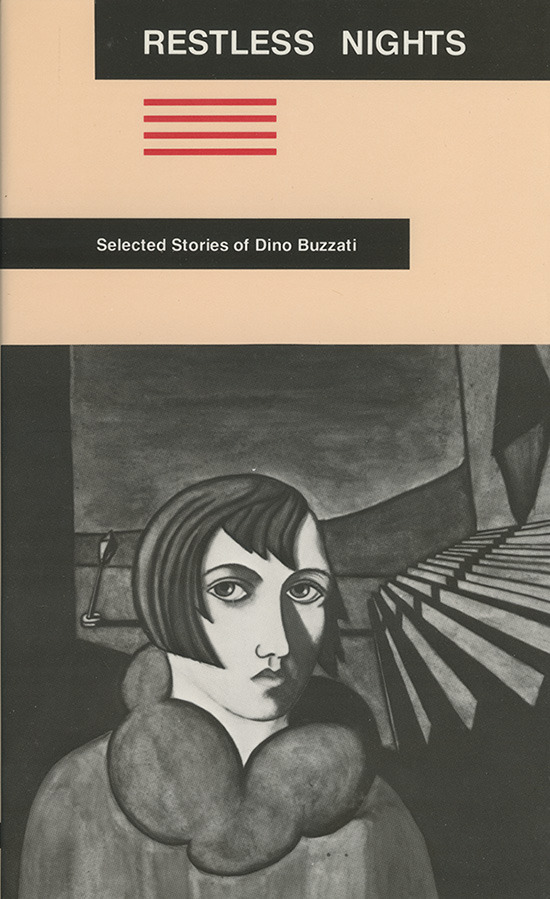

Plenty of people read Dino Buzzati, which is maybe why these books are always hard to find: Restless Nights and The Siren, two story collections translated by Lawrence Venuti, published by North Point Press in 1983 and 1984. 50 Watts Books has a small number of them for sale.

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

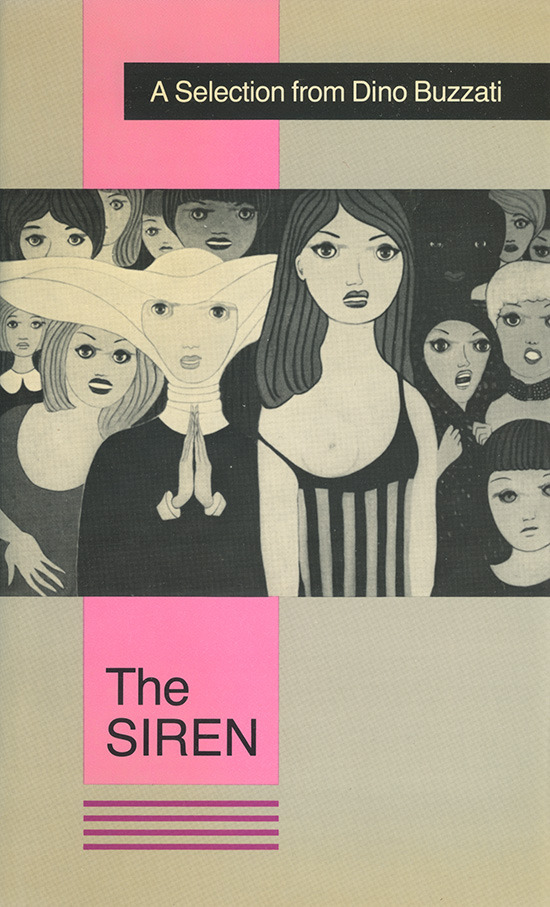

If anyone is still looking...I now have a little store selling obscure fiction and art books: 50 Watts Books. In the coming months I’ll be selling my own book collection too...

Stephen as you might know has been operating a real store, Point Reyes Books.

78 notes

·

View notes

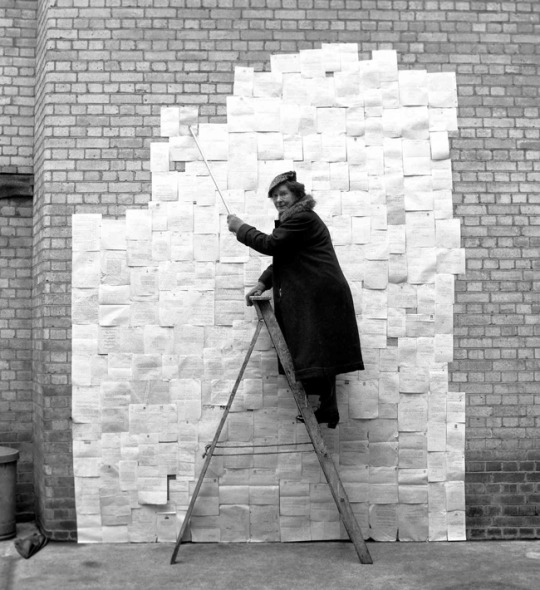

Photo

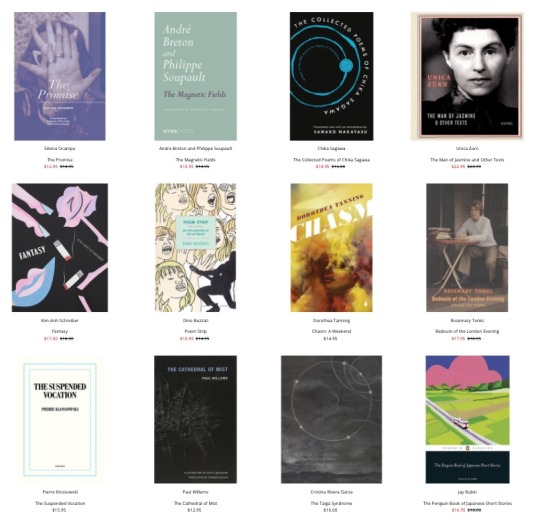

No one reads Dmitri Prigov (see photo).

Read Jacob Edmond on Prigov’s Little Coffins.

Bio from Ugly Duckling Press:

Dmitri Alexandrovich Prigov was born in Moscow in 1940. Trained as a sculptor at the Stroganov Institute, he worked as an architect and made sculptures for public parks during the Soviet era. A prolific writer (in 2005 he estimated that he had already written 35,000 poems), he was a founder of the “Moscow Conceptual art” school. He wrote in almost all conceivable genres (including two novels), was an active performance artist, produced videos, and drawings and installations. He also acted in films, including Taxi Blues. Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Prigov published in underground and émigré journals, and was briefly sent to a psychiatric hospital after being arrested by the KGB. With the onset of glasnost and perestroika, he was able to publish and show his visual art in “official” venues, and also exhibited his art outside of Russia. During the Soviet period his work fiercely satirized official language and culture; after the collapse his writing became more philosophic – but both before and after it energetically explored all the possibilities that language and literature offered. He won several prizes, including, in 2002, the Boris Pasternak prize. Prigov died, in Moscow, of a heart attack in 2007. His collected works are being published in Russia, edited by Mark Lipovetsky.

Image: Dmitri Prigov, Odna tysiacha trista semʹdesiat sedʹmoi grobik otrinutykh stikhov [The one thousand three hundred and seventy-seventh little coffin of rejected verse], n.d. Paper, staples, typescript text, 14.7 x 10.5 cm.

66 notes

·

View notes

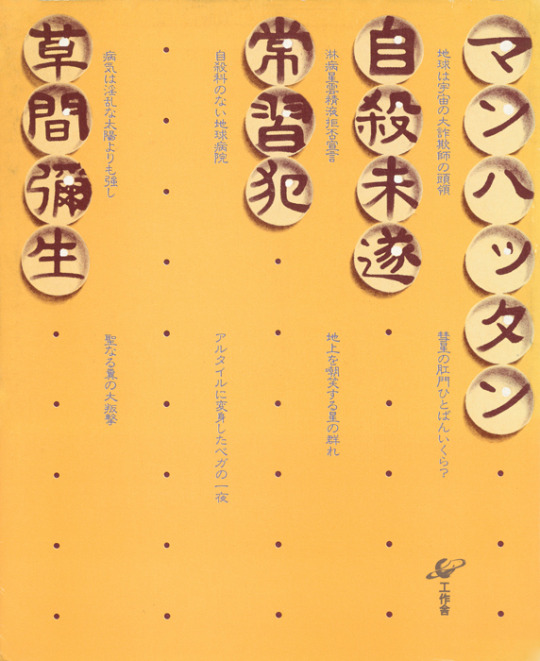

Photo

From wikipedia (which is based on this timeline):

In 1977, [Yayoi] Kusama published a book of poems and paintings entitled 7. One year later, her first novel Manhattan Suicide Addict appeared. Between 1983 and 1990, she finished the novels The Hustler's Grotto of Christopher Street (1983), The Burning of St Mark's Church (1985), Between Heaven and Earth (1988), Woodstock Phallus Cutter (1988), Aching Chandelier (1989), Double Suicide at Sakuragazuka (1989), and Angels in Cape Cod (1990), alongside several issues of the magazine S&M Sniper in collaboration with photographer Nobuyoshi Araki.

I think English-language readers would flock to the “shockingly visceral and surrealistic” Manhattan Suicide Addict and Woodstock Phallus Cutter. Someone should hire translator Ralph McCarthy and make it happen. Actually, there is a hard-to-find 1998 English-language book called Hustlers Grotto: Three Novellas...translated by McCarthy! [Image: First edition of Manhattan Suicide Addict, 1978 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio inc.]

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

No one reads Virgilio Piñera, mostly because, as the Guardian tells it, his career was derailed when he “was arrested under [Fidel Castro’s] government's clampdown on the ‘three Ps’ (’prostitutes,’ ‘pimps,’ and ‘pájaro’ – homosexuals in Cuban Spanish slang).”

At the time of this writing, the extent of Piñera’s work in print in English is a play and only a handful of poems, despite the fact that he was a prolific writer of short stories, many of which are included in Eridanos Library’s collection, Cold Tales.

Thanks to Marcel Schwob translator Kit Schluter for introducing me to Piñera’s work, which often reads like a more macabre Julio Cortazar.

Visit the Neglected Books site for more on this writer no one reads.

121 notes

·

View notes

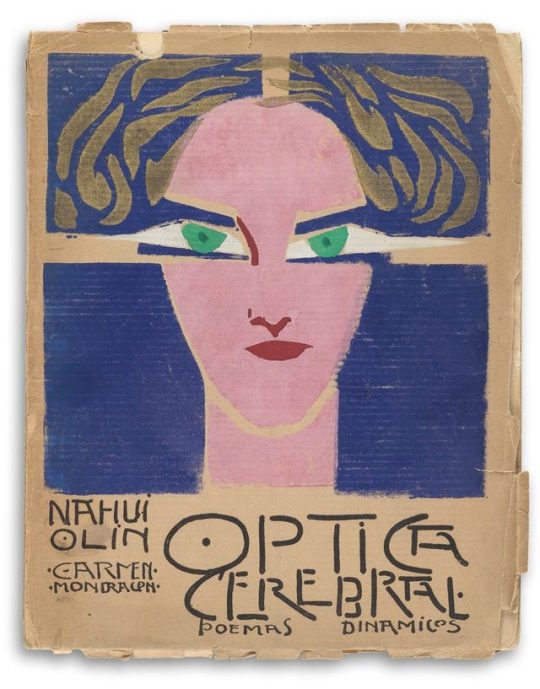

Photo

No one reads Carmen Mondragón aka Nahui Olin.

355 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Finally in English: The Evenings by Gerard Reve (and it’s as incredible as I hoped). I wrote a pretty manic post about Reve five years ago (where has all my energy gone). The Pushkin edition just got a nice review in the New York Times. Reve on his book:

I wrote “The Evenings” because I was convinced I had to write it: that seems to me a good enough reason. I hoped that ten of my friends would accept a free copy, and that twenty people would buy the book out of pity and ten others by mistake. Things turned out differently. It’s not my fault it caused such an uproar.

I think fans of Robert Walser would love this book. The vivid dream sequences called to mind David Lynch more than anything. It was written by a 23-year-old in 1947 Europe, so it’s a little dark.

541 notes

·

View notes

Photo

No one reads Zora the Unvanquished.

Photograph by Ken Russell titled “We Regret to Inform You,” 1955, copyright Ken Russell/TopFoto.

From The Guardian: “This image is taken from a series called Zora the Unvanquished, taken of 72-year-old Zora Raeburn who wrote novels and sent them to publishers for 30 years, with no acceptances – she is pictured here with a montage of her rejection letters.”

Part of the exhibit Reality is a Dirty Word: Photographs by Ken Russell at Proud Galleries, Chelsea, 1 December - 3 January.

643 notes

·

View notes

Photo

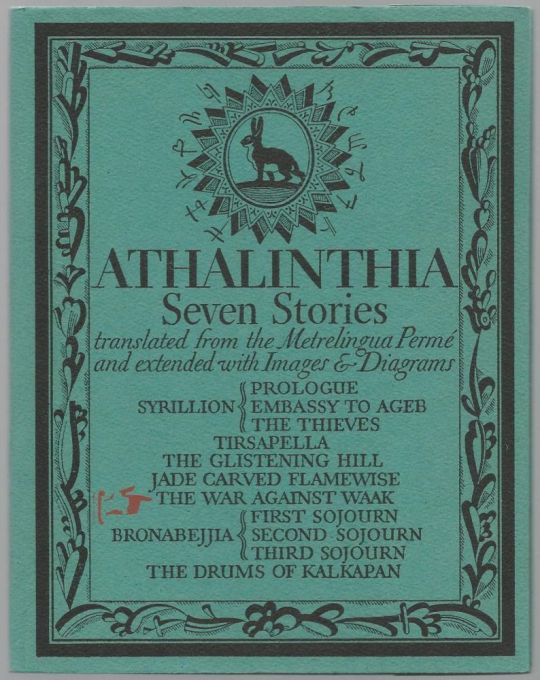

No one reads the fiction of graphic design legend William Addison Dwiggins, because it is impossible to find. I stumbled upon this material while putting together a post on Dwiggins on 50 Watts.

BookTryst: “The small books Dwiggins produced at his private press Püterschein-Hingham have a wonderful mix of experimental type, page layout and illustration. The War Against Waak (1948) shows, in the writing, his admiration for his contemporary, Lord Dunsany.” (Pictured above are the cover and an illustration from this book.)

Bruce Kennett, from his article The Private Press Activities of William Addison Dwiggins: “Armed with a sharp wit and an insightful appreciation of human nature, Dwiggins (‘WAD’) often used humor to drive home points that he wished to make about serious topics. He produced articles and essays under his own name or that of his imaginary colleague, Dr. Hermann Püterschein. He wrote plays for his marionettes, then watched as they were performed in a purpose-built theater of his own design. Dwiggins also wrote a series of fantasy tales—‘The Athalinthia Stories, translated from the Metrelingua Permé and extended with Images and Diagrams’—that captured the sights and scents of exotic places while regarding human aspirations and foibles with particular tenderness and Puckish humor. His personal work was peppered with references to literary classics, revealing his own passions for this subject. All of these activities found expression in his private press work.”

Cover image found here. The illustration is reproduced in William Addison Dwiggins: Stencilled Ornament and Illustration. More at 50 Watts.

252 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Haven’t read David Markson? The inaugural issue of The Scofield is devoted to this underappreciated writer and includes essays, marginalia, book recommendations, and more.

118 notes

·

View notes

Photo

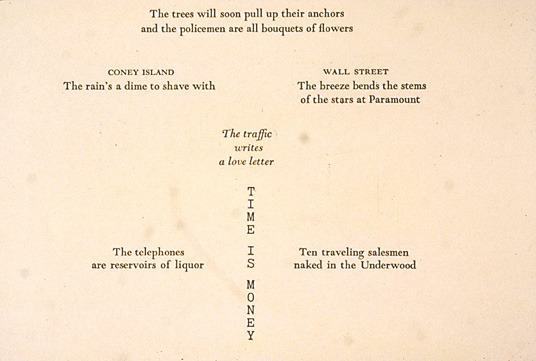

A spread (in English translation) from 5 metros de poemas, composed between between 1923 and 1925 by Carlos Oquendo de Amat (born 17 April, 1905; died 6 March, 1936); the work, comprising 18 poems in a five-meter-long accordion-fold layout, was published by the Lima-based publisher Minerva in 1927, by which time the author had joined the Communist Party and had foresworn writing poetry; the English translation here is by David Guss, 1986; a more recent English edition, faithful to the original, is available from Ugly Duckling Presse

One of the few photographs of Carlos Oquendo de Amat (date unknown)

181 notes

·

View notes

Photo

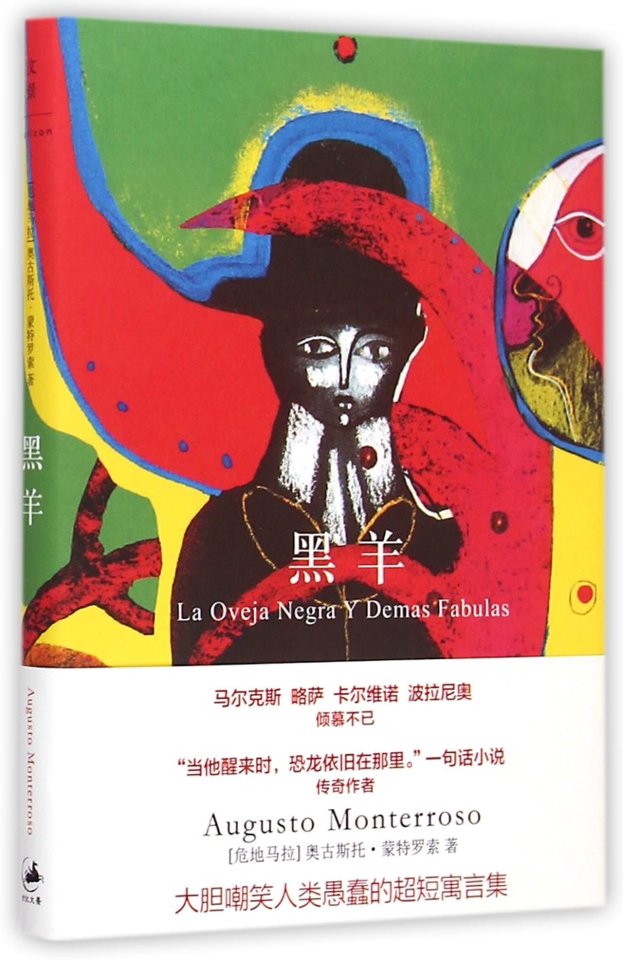

Stephen wrote a feature on writers nobody reads -- including Augusto Monterroso -- for Literary Hub. (Pictured: new Chinese edition of The Black Sheep.)

170 notes

·

View notes

Photo

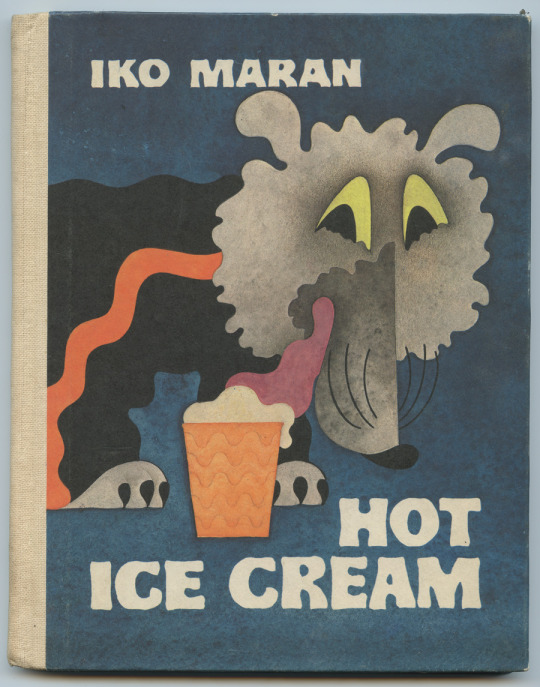

No one reads Iko Maran (1915–1999; obituary by fellow writer Aino Pervik, in Estonian).

I bought Hot Ice Cream from an Estonian book dealer for Heldur Laretei’s gloopy illustrations, not even particularly noticing the weird title in English (original: Tuline Jäätis, 1978). I picked up the book tonight and opened right to this page.

Subtitle: Adventures of Little Siim and Trunkie the Rubber Elephant.

556 notes

·

View notes

Photo

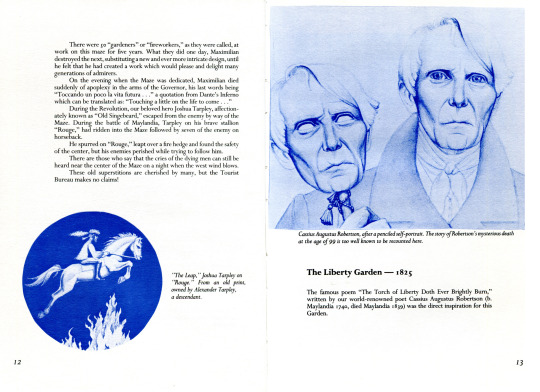

Submitted by Craig Conley:

No one reads fine artist Rhea Sanders’ guidebook to the fictional Fire Gardens of Maylandia or Sweetwilliam’s Folly (The Tradd Street Press, Charleston, SC, 1980). The author respectfully dedicates this wryly humorous, meticulously envisioned oddity to “the virus which gave me the fever which gave me the hallucination which gave me the idea for this book.” The reader of the deadpan guidebook is presumed to be a tourist to the state of Maylandia, in possession of a working knowledge of local attractions, so the mysterious nature of the fantastical fire gardens is revealed in subtle tidbits as the site’s colorful and often controversial history is explored. We learn that the gardens were conceived in 1720 by the first royal governor, Ferdinand Mayland, “during one of his annual bouts with a local fever.” The author dryly recounts how the governor persuaded the indigenous Changapod tribe to relinquish their sacred plains of flaming shale at the foot of the mountain they called “He Who Waits”: “Since all objected, all were done away with. This is indeed a sad episode, but it is well to remember that the Changapods had owned this territory for centuries, and had done nothing with it, whereas Governor Mayland imagined a work of art. There were in any case only 370 Changapods.” As the history progresses, we become privy to intimations of “fireworkers” in possession of “the knowledge” — carefully guarded secrets of controlling the shape, movement, and color of fireballs, handed down from father to son over generations. We learn of figures with oddly Francophilic inclinations, such as the Governor’s London-born wife Marguerite, who “spoke only in French, for reasons which have not come down to us.” We learn of the possibly addictive tea leaves that grow near the fire gardens and seem to treat the blue skin condition resulting from exposure to the natural gasses. (“And why should everyone be either black, white, red, or yellow?”) We learn of several possible murders along the way, all unsolved, including one in 1927 — the winner of a contest to name a new garden to express the spirit of the age. A certain Billy Jackson’s entry, “Jazz Baby,” earned him a $5,000 check, though he was shot and killed on his way home and the check stolen. ”We in Maylandia often point to Mr. Jackson’s Jazz Baby Garden when outsiders ask us about the minorities in our midst. For what could be a more beautiful testimonial to our treatment of minorities than this Garden?” We learn of tea plantation heiress Angela Longleaf MacDowell, who stood six feet tall and boasted, “No man on earth or beneath the sod has ever kissed the lips of Angela Longleaf MacDowell.” It was she who envisioned, in a dream, the memorial fire garden for famed local poet Cassius Augustus Robertson (“the story of Robertson’s mysterious death at the age of 99 is too well known to be recounted here”). Profusely illustrated by the author, The Fire Gardens of Maylandia is a charming, deeply funny, and thought-provoking relic from an alternate reality just a little bit more smoldering than ours. (Profuse thanks to Hilary Caws-Elwitt for recommending this book.)

—Craig Conley, author of One-Letter Words: A Dictionary (HarperCollins) and Magic Words: A Dictionary (Weiser Books)

129 notes

·

View notes

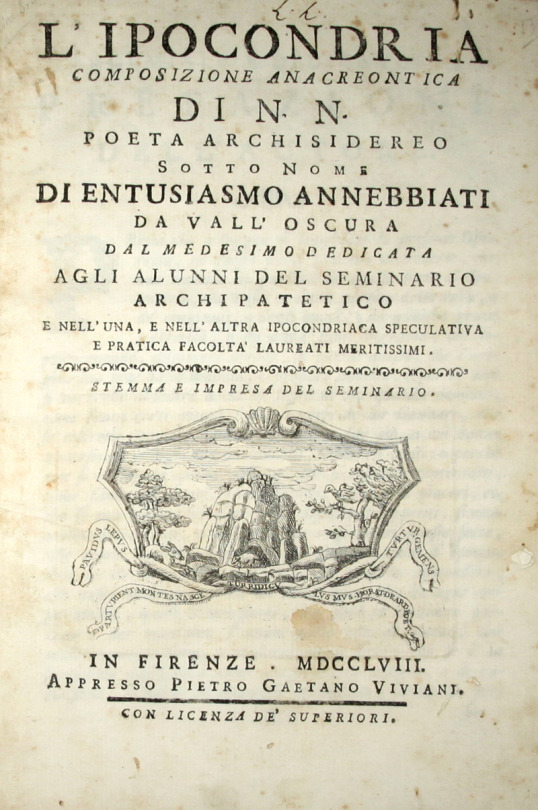

Photo

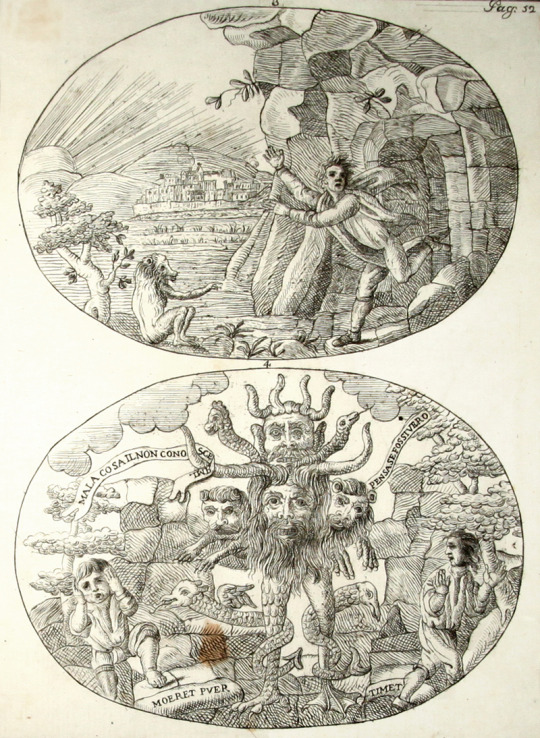

No one reads "Bleary Enthusiasm of the Dark Valley."

First edition, extremely rare, of this allegorical poem on hypochondria. Although the identity of the Italian poet who penned this work remains unknown, his chosen pseudonym, which translates to something like "Bleary Enthusiasm of the Dark Valley" is nonetheless amusing. The story follows the narrator and protagonist, Fabrizio, through the Kingdom of Hypochondria where he meets its queen and her entourage of gruesome characters, a scene brought to life in one of the five wonderful plates included in this work. After the main poem, the author supplies his own commentary, complete with an explanation of the rather puzzling title vignette.[via B & L Rootenberg]

245 notes

·

View notes

Photo

No one reads Ernst Kreuder (1903-72).

A couple years ago I bought Kreuder’s The Attic Pretenders (1946; trans. 1948 by Robert Kee), but by the time it arrived in the mail I had forgotten what prompted the purchase. Tonight I figured it out: in The Man of Jasmine, Unica Zürn writes about wandering into the attics of random buildings convinced she would meet the Attic Pretenders, “these people from a novel she has read and who have come to life in order to please her.” In an endnote, Malcolm Green says it is “one of Unica Zürn’s favorite books. The characters in the novel counter the enforced seriousness of life with an anarchic, childlike playfulness."

The final paragraph of The Attic Pretenders:

Suddenly I had to stretch myself, to stretch the whole of my body. And with this stretching the last resistance broke inside me. Something seemed to pierce me. It was as if I had run into something. I trembled in every limb. The words were already chasing each other through my brain. I jumped off my bunk, feeling alternatively hot and cold all over. I heard voices that were not there and saw myself as in a dream pull open the drawer, lay the paper out on the table, and dip my pen into the ink. A rushing wind was about me, I felt myself beginning to glide away. I was gliding as in a delirium, as in the moment before falling asleep. I wrote. I left my personality farther and farther behind. I wrote faster and faster. I was losing touch with everything I knew, and yet I had found myself. I had become a great mine of voices and stories and, as I wrote, I fell through space and time into another world.

184 notes

·

View notes

Photo

No one reads Liliane Giraudon.

[The following review of Giraudon's Fur is by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert. It was first published in Bakunin vol 6 (1997) as part of Alter-Gilbert's feature on the "cruel tale."]

The first thing that strikes the reader of the fiction of Liliane Giraudon is that she doesn't write like anyone else. Bearing vague traces of surrealism, Giraudon's oeuvre draws comparison with that of Leonora Carrington, Gisèle Prassinos, and Rikki Ducornet; but Giraudon is not a surrealist. Neither is she a pure fantast like her French contemporary Julia Verlanger, nor a naive meliorist in spite of all odds like her other compatriot Marie Redonnet [ed.: Alter-Gilbert translated Redonnet's Dead Man & Company]. Her voice is hypnotic, inscrutable, unique. A trip through one of her narratives is like a somnambular stroll through a rain-soaked ravine with an unreadable road map; a ramble in fugue-state through a wilderness where signposts are written in the language of emotion and the logic of the heart.

Giraudon is a practitioner of silent writing—that is, writing which does not explicitly signal its meaning or purpose. Her poetically-charged prose percolates with unsaid bubblings and unstated gurglings which never surge to the surface, but rush past in irresistible riptides. Her style is discontinuous, at times even fragmentary, yet image-rich and marked by descriptive precision. This disjunctive, highly-colored verbotechny results in an exquisite fuzziness a la Mallarmé. The pieces of her puzzles are like broken mirror shards, each reflecting other parts of a larger image, but never the whole. A clue may be taken from the title of her previous collection of stories (also published by Sun & Moon) Palaksch, Palaksch: a phrase employed by deranged poet Friedrich Holderlin, to mean anything...or nothing.

Giraudon's operational field is a mythic space unpolluted by references to contemporary cheese culture; her characters breathe the sterile air of psycho-emotional vacuum. Her plots and themes are enigmatic and border on the unreal, if not, at times, the non-representational; but there are badges of familiar sensibility—a preoccupation with victims and victimization, revenge motifs, and acts of unrepentant enmity—conspicuous hallmarks of the cruel tale. Her inventory is stocked with fetish and fixation, aberrant behavior, medical anomaly, atavism, evolutionary warpage, and creatic compulsion. Her characters are wounded souls, lost, lonely, often self-loathing; insular anti-heroes whose private hells slowly unravel to reveal a barely controlled hysteria. Their secret selves, propelled by instinct and animal drives, are awash with dark undercurrents of primal savagery; held in bondage by a sensuality which starts out where D. H. Lawrence left off, they grope in a stew of dream and desire, around which the deformed, the disfigured, and the denatured do a dance for domination. These prisoners of the flesh, beset by strange obsessions, teased by Aeons and Archons, tortured by twisted eroticism, are gripped by predatory forces to which they are tacitly resigned. The spirit of Dr. Moreau is everywhere: hints at moonspawn and mutant progeny abound; insinuations of union between man and beasts accentuate an exploration of biomorphic boundaries and what defines them.

At least two of Fur's narratives sit squarely in the grand tradition of the cruel tale: "Clothilde's Goat" and "The Yellow Glove." Others are about life's cruelties: its tantalizations and temptations, dashed hopes, and damaged dreams; about dead babies whose absence is commemorated by concluding lines like: "At this time, around her, that is, here, near us, the stars continue their monotonous course; a terrible heart disease is found in all dogs."

In "Lateral Life," the subject is bodily sacrifice; in "The Lesson," interruption, truncation, curtailment of action, inhibition of completion; in "The Peephole," it is a masochistic ravishment persecution fantasy, with minatory spectral participants; in "The Tie," the thinness of the veneer separating civilization from the teeming bestiality beneath. In "The Center," linguistic interpreters inhabit a tactile sensorium which is a metaphor for the elusiveness of the abstract, the unobtainable nature of the absolute, and the ephemerality of all things; "Pauline Buisson" is about the art of suffering, how fate exacts its pound of flesh, how people get under the skin and make each other bleed; in "Wolf Pass" the keynote is the threat of the inhuman; in "Lidia's Leg," cross-species loss and longing.

From the country which gave birth to the cruel tale, to the Theater of Cruelty and to Donatien Alphonse de Sade, comes a fresh contribution to the canon of the unkind: Fur is a book of disturbing beauty reverberant with endless mystery.

[Gilbert Alter-Gilbert is a critic, translator, and literary historian whose recent publications include the grim anthology Life and Limb and an English-language edition of Vicente Huidobro's Manifestos Manifest. An "experimental classicist," Alter-Gilbert is an inveterate practitioner of fictive history (see Poets Ranked By Beard Weight), a genre pioneered by such illustrious forebears as Marcel Schwob and Raymond Roussel.]

Ed: also see a post on Giraudon on the Project for Innovative Poetry blog.

@WritersNoOneRds / Facebook

539 notes

·

View notes