#caroline era

Text

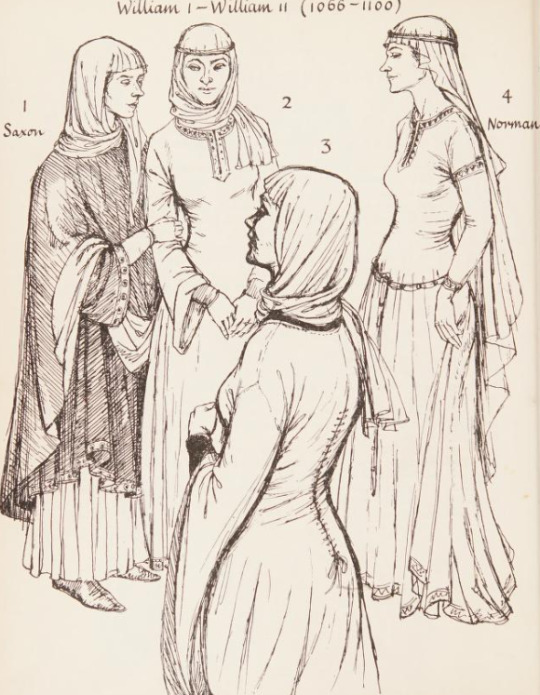

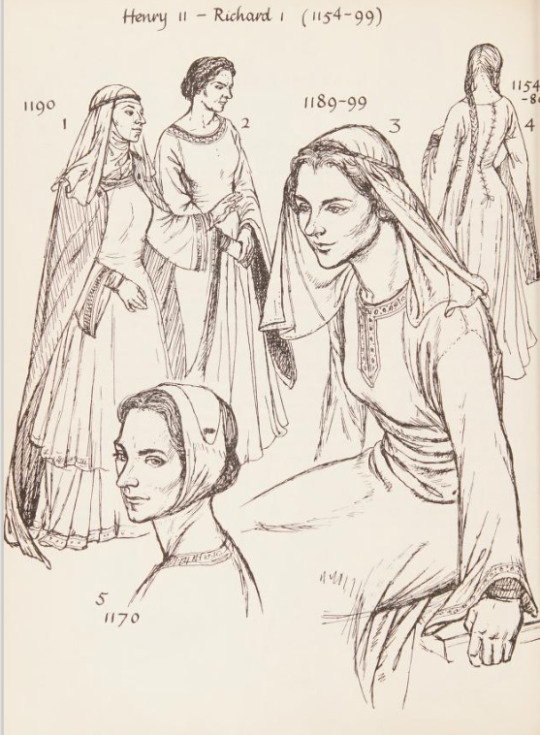

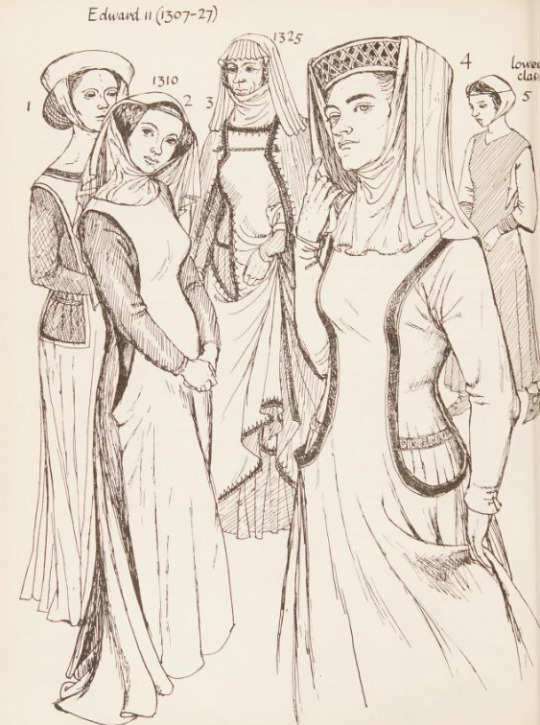

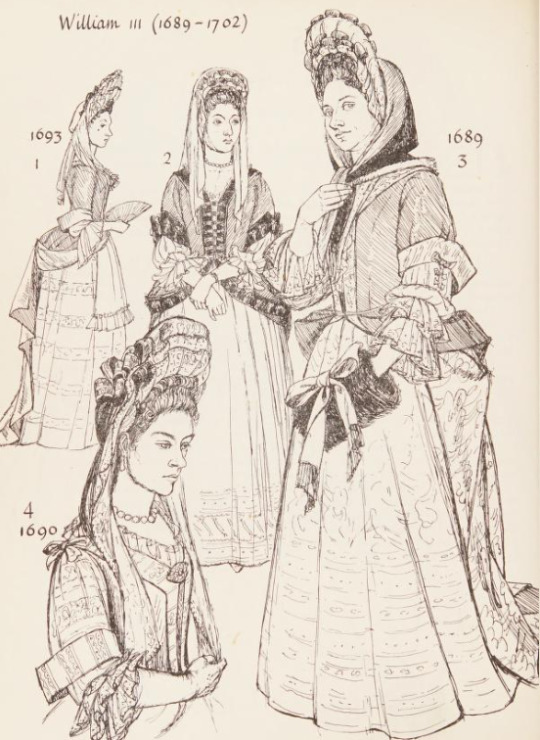

Historical Costumes of England from the Eleventh to the Seventeenth Century

- Nancy Bradfield, 1963

283 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Winter

The cold, not cruelty makes her weare

In Winter, furrs and Wild beasts haire

For a smoother skinn at night

Embraceth her with more delight

1643 etching by Wenceslaus Hollar copied by his pupil, Richard Gaywood, in 1654. part of a set of 4 etchings depicting the seasons

#1643#1654#1640s#1650s#17th century#winter attire#winter#etching#prints#historical fashion#womenswear#fashion#masks#Richard Gaywood#Wenceslaus Hollar#Václav Hollar#England#europe#Caroline era

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

roy christmas 1991

#succession#kendall roy#roman roy#shiv roy#succession fanart#caroline collingwood#my art#in an early draft logan was included but…#dad present at important family events? unrealistic#caroline on her princess diana haircut era IGNORE the year i don’t know if it’s anachronistic or not#lol

914 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who BBC Portraits: The Third Doctor Era (1970-74)

#doctor who#classic who#third doctor#liz shaw#the brigadier#jo grant#mike yates#sarah jane smith#sergeant benton#jon pertwee#caroline john#nicholas courtney#katy manning#richard franklin#lis sladen#john levene#now i know the sjs pic is from the fourth doctor era but it didnt feel right to exclude her!!!!#series 7#series 8#series 9#series 10#third doctor era

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

ATTENTION ROMANTICS, JANEITES, BYRONISTS, GEORGIANS, & OTHER 19TH CENTURY NERDS!

this website jane austen's music has resources all about the music jane austen composed by hand, like a link to this song captivity.

this website romantic-era songs has recordings of a bunch of music that was popular in the romantic era, including recordings of poetic works that were originally intended to be set to music. examples incl. lord byron's famous poems vision of belshazzar (a real banger!) & she walks in beauty (not what i expected having read it beforehand without it's music, but it was byron's own favorite to listen to). i really love this one the waters of elle by lady caroline lamb, also composed by isaac nathan. he was a famous jewish-english musician who later relocated to australia and introduced classical music there, & is thus sometimes called "the father of australian music" (apparently, according to his wiki, he was also the first person in the southern hemisphere to die in a tram incident after he got there... oddly specific factoid, but alright).

#literature#english literature#lord byron#romanticism#history#poetry#music#songs#19th century#nineteenth century#recordings#compositions#composers#isaac nathan#caroline lamb#romantic era#the romantics#the young romantics#romantics#romantic poetry#music history

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday to the king and queen of Naples

#napoleonic era#napoleon bonaparte#french history#my art#joachim murat#caroline bonaparte#art#napoleonic wars#artists on tumblr#napoleon's marshals#posting this an hour early cuz yo girl needs some sleep

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Dress a Day Challenge

September: Bond Films

The Spy Who Loved Me / Caroline Munro as Naomi

In terms of the "five primary modes of Bond girl chic," would this count as a combination of swimwear and lingerie? But it also functions as no-nonsense work clothes, since Naomi is all business and she works around water a lot.

The ropes of beads all over the wrap she's wearing over the swimsuit look pretty, but they seem like they would get in the way a lot.

#the spy who loved me#bond film costumes#caroline munro#one dress a day challenge#one dress a week challenge#movie costumes#1977 movies#1977 films#james bond films#swimwear#stylish villain#1970s fashion#1970s style#70s fashion#70s style#roger moore era

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

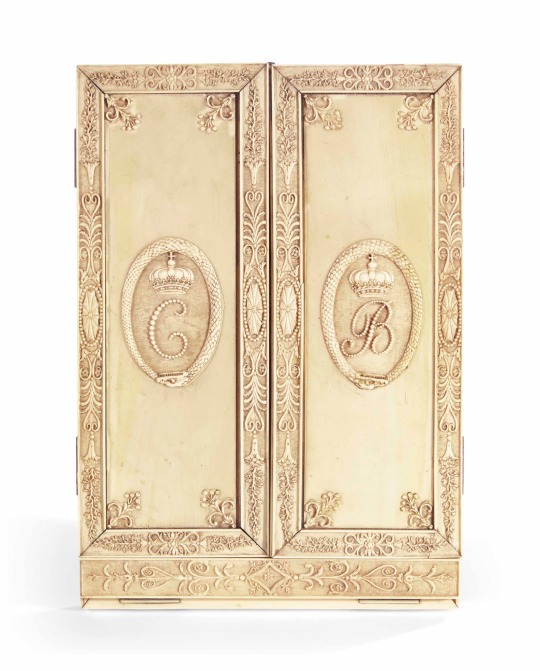

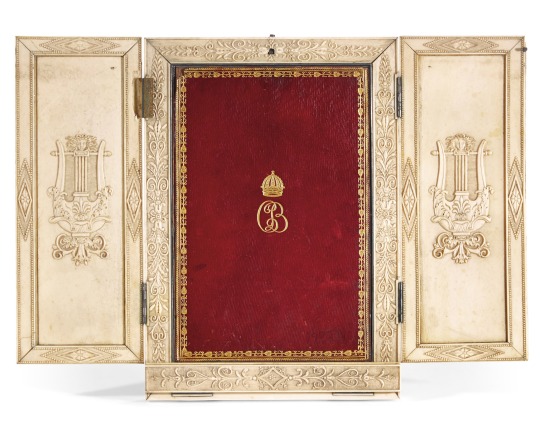

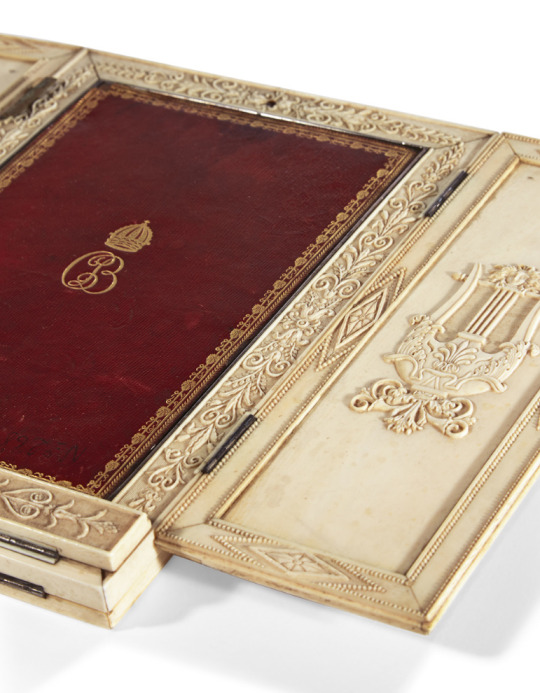

First French Empire era travel mirror. Monogram of Caroline Bonaparte.

(Christie’s)

#Caroline#Caroline Bonaparte#Caroline Bonaparte Murat#travel mirror#mirror#empire style#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Napoleon’s sisters#first french empire#french empire#19th century#1800s#Christie’s#auction#france#history#french history#artifact#napoleon#art#neoclassical#neoclassicism#empire

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE GILDED AGE + ART [2/∞]

Young Caroline Webster Schermerhorn (1860) by an unknown artist

Mrs William Astor (1890) by Carolus-Duran

Caroline "Lina" Schermerhorn Astor played by Donna Murphy

#the gilded age#thegildedageedit#lina astor#caroline astor#mrs astor#donna murphy#costume drama#costume design#19th century#carolus duran#portrait#realism#oil on canvas#art#1860s#1890s#victorian era#gilded age#the gilded age + art#🎥🎥

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

As someone that genuinely loved bonlena’s friendship in season one. When you compare bonlena to other girl duos in that era like Brooke/Peyton, Blair/Serena or even just comparing them to Elena/Caroline. All of these girl duos have issues. Which is normal. But, the issue is that Bonnie never gets to vocalize how Elena or Caroline hurts her directly or indirectly. She accepts these things and just goes off-screen. Bonnie very rarely blames anyone or calls anybody out she just says what she disliked. Most fans claim they’ve disliked Bonnie due to her season 1-2 personality and only find her likable due to s6. “Bonnie’s independent that’s why….” Independence doesn’t meant no one should care lol.

Caroline has the privilege to tell Elena off. She thinks Elena’s selfish? Thinks Damon is a bad influence on her? She says that. Bonnie never once does that. She doesn’t label Elena or Caroline the root of all things. When she attempts to be more reserved it only happens off-screen. When it comes to Caroline, she’s taking up for her and still too in-tuned with her own life at points to notice Bonnie’s struggles.

Bonlena can’t discuss their issues and really doesn’t anymore once Caroline fills in that space as Bonnie is pushed out the plot outside her magic. When Abby is turned, Elena wanted to go an apologize. Caroline refused it, we get the line about how Bonnie is always the one hurt but very little done on Bonnie’s thoughts after that. This also applies to how the writers wrote Elena to revolved around the Salvatore’s.

Anyways i say all of this to say I don’t get how some people can label Bonnie fans or their work just Caroline or Elena bashing when their giving her feelings and a plot that has nothing to do with Caroline or Elena. Like you don’t think there should’ve been some discussion on how her friends didn’t notice she was dead all summer? Or when Elena tried to kill her? How Caroline is often wrapped up in dating drama to notice her bestfriend having a bad day? Bonnie deserves having a voice too.

#Bonlena#This was not an anti post lol i genuinely do wish we ended up with more trio moments in the end#And that the mfg didn’t feel like supernatural coworkers…#i was watching o t h and it was that era of Brooke/Peyton fighting and arguing lol. saying how they feel….#bonnie bennett#elena gilbert#caroline forbes#tvd#the vampire diaries#Baroline#barolena

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Familial loyalties between fathers and sons that jeopardised the material well-being of the mother and her illegitimate child could create considerable conflict within a parish. …Fathers who failed to take order regarding their son’s indiscretions might also find themselves charged with incontinent living besides becoming financially liable for the consequences. In 1628, the churchwardens of Wisborough Green (Sussex) not only presented John Nightingall and Mary Lewer (his father’s servant) for incontinency following Lewer’s confessions that she was pregnant by John, but also Robert Nightingall, John’s father, ‘for a very bawd’.

This was because he had for several months ‘bin told, both [by] our vicar and also by divers others, what great familiarity was spoken of to be betwixt his said sonne John and Mary Lewer’ but had failed ‘either to cause them for to be marryed or els to put them asunder … which maketh many people uppon great presumptions for to suggest that the said Mary is an harlot common both with the father and also with his sonne’. As a consequence all three were ‘kept backe from the Lord’s table, for the great suspicion of their incontinency’.

Measures whereby grandparents were ordered to take responsibility for their children’s children reflected a wider framework of familial protection that could be extended to parents of ‘base-born’ children. While this sometimes incurred punitive consequences at the instigation of churchwardens and overseers seeking to limit charges to parish funds, grandparental involvement – and expenditure – was often voluntary and did not necessarily entail competing loyalties towards children and grandchildren.

While it was more often maternal grandparents of illegitimate children that featured in quarter session orders both being compelled and volunteering to take on the responsibility for their grandchildren’s maintenance, fathers of putative fathers can also be glimpsed substituting their own means on behalf of their sons. …A similar arrangement appears to have been brokered between the grandparents of the child Alice Martin was carrying in 1640, of which the labourer Thomas Spencer was the reputed father.

William Martin, Alice’s father, ‘did voluntarily undertake to keep her … until she could be delivered’, after which John Spencer, Thomas’s father, undertook to ‘keep the said child’ on account of his withholding consent from his son to marry Alice ‘unless he should be compelled by law’. As in this last case, fathers of putative fathers often stepped in to let their sons off the hook and such actions mirrored the kind of arrangements that could be put in place for the care of legitimate children who had been pre-deceased or deserted by their fathers.

These measures could therefore function as a form of licensed desertion or figurative death, and may well have deprived both the illegitimate children and their ‘reputed’ fathers of the opportunity to form lasting bonds. However, it is also possible that such arrangements (many of which would have been brokered out of court) actually served to facilitate paternal contact and prioritise it above maternal claims on either the putative father or their child.

Similar interpretative ambiguities regarding attitudes to putative fathers arise from measures put in place by JPs to secure the maintenance of illegitimate children. On the one hand, magisterial orders were principally motivated by the need to limit pressure on the charges borne by ratepayers, and they were therefore focused on extracting a financial commitment from putative fathers.

This had a punitive as well as pragmatic dimension, divorcing maintenance from those concepts of honesty and that were normatively associated with a man’s provision for his dependants. Orders sometimes stipulated that payments should be made after divine service at the communion table or in the church porch, in rituals of reparation which were public and which may have therefore carried associations of shame.

On the other hand, the preoccupation with maintenance was not always severed from expectations that fathers would play an active role in the upbringing of their offspring, although – significantly – such expectations appear to have diminished over the course of the seventeenth century. While this might be judged to have been beneficial to the men concerned, freeing them from the direct responsibilities of parenthood in ways that were increasingly unthinkable for the mothers of illegitimate children (particularly during infancy), it also more decisively severed the links between paternity and parenthood in cases when fathers were deemed incapable of maintenance, thereby channelling patriarchal dividends out of the hands of the poor.

Many putative fathers were not shielded by their families of origin from either the charges or even the practicalities of caring for illegitimate children. Securing a child’s maintenance without charge to ratepayers was the main preoccupation of JPs concerned with giving orders to ‘reputed’ fathers. However, it was not unheard of, particularly in the earlier part of the period, for JPs to expect more paternal involvement than the basic provision of regular maintenance payments and sufficient security to protect parish rates.

A few maintenance orders issued by JPs stipulated a division of labour between mothers and fathers of illegitimate children that entailed fathers taking over direct responsibility, usually after infancy or early childhood, at the very least for decision-making concerning the child’s future if not for its day-to-day care. JPs in Staffordshire in 1601 ordered that John Sabin should pay 10d weekly towards the maintenance of the child he fathered on Alice Godwin until its second birthday, after which he was to ‘take charge of the child’, receiving 1d weekly from Alice until the child was able to get its own living.

At the Wiltshire Sessions in 1615 it was similarly ordered that an illegitimate child should be nursed and brought up by his mother until he ‘shall accomplishe the full age of three years’, during which time the father was to pay 10d weekly towards his maintenance. After this point the father was to ‘keep and maintaine the childe untill he be fitt yeares to be bound as an apprentice in some Trade or mistrie’ during which time the mother was to contribute 4d weekly to the father’s costs.

In determining a period of payment, it was not unusual for maintenance orders to oblige putative fathers to undertake weekly contributions until they took over the child’s care or arranged a place in service or apprenticeship, and it is possible that fathers were expected to take direct responsibility for such placements in a division of labour that would have mirrored the duties of fathers towards their legitimate offspring.

In the early 1560s the Durham church courts presided over a settlement between the parents of a ‘bais begotton’ girl to the effect that her father William Brandling was to ‘have the rewll, order and government’ of the child while her mother agreed from henceforth to have ‘no medlynge with the said wench, to enties hir frome any servic order or apointment lawfullye by the said William the wench shall be assigned unto’. William, in the meantime, was to compensate the mother for her former charges associated with bringing up their child with a bundle of lint or flax annually for the following four years.

…Petitions lodged with JPs sometimes included expectations that putative fathers should take on direct and immediate responsibility for a child’s care, such as that lodged by Eleanor Raynolds in 1619 requesting that the father of her child, a butcher, be ordered ‘to breed up the said child or give her money wherewith to maintain it’. The fellmonger Augustine King was similarly issued with the choice between taking on ‘the whole keeping and nourishing’ of his bastard child or paying a weekly sum of 12d to the overseers of the poor ‘for its upkeep and education until it can be placed in service’.

That a request for a father to take on his illegitimate child was not merely an empty threat designed to extract maintenance payments is suggested by orders that presumed paternal responsibility, such as that issued by Warwickshire JPs in 1662 subsequent to Elizabeth Morrell’s affiliation of her child to William Search during her delivery. On the basis of the testimony of midwives present at the birth it was ordered that Search ‘shall from henceforth receive, provide for and maintain the said bastard male child’, free the parish of Milverton from any charge relating to his maintenance and pay James Morrell, in whose house the child had been born, his ‘reasonable charges’ for Elizabeth’s lying in.

In a few instances, sessions records provide fleeting references to putative fathers voluntarily taking on direct responsibility for their children’s welfare. In 1665 the Warwickshire bench ordered that the child of Anne Wilcox be removed from her care in the county gaol on the petition of its father who was ‘contented to maintain and provide for the said child’ and who was exhorted to ‘take care that the said child be carefully provided for’.

This may have been a temporary measure, as in the case of Richard Jones who had been entrusted with the care of the child he had fathered on Elizabeth Smyth while she remained in the house of correction, which arrangement ceased when she was freed as a consequence of inheriting ‘some reasonable estate whereby she … is of ability to maintain herself in good sort’. However, it is important that we do not discount the possibility in at least some cases of genuine affection on the part of fathers towards their illegitimate children.

Such emotions are unlikely to have surfaced in the routine orders issued for maintenance – not least since most cases came to the attention of the quarter sessions as a consequence of some kind of default – but they can very occasionally be discerned elsewhere. The sentiments of Richard Smyth, for example, servant to Elizabeth Watson, were recorded in 1617 after she was suspected of drinking a substance concocted to destroy the child she was carrying, fathered illegitimately by Richard.

He confessed to a number of witnesses that, having often lain with him, ‘my dame nede not a gone awaye frome me thus for I dide never deserve it at her hand’, declaring that ‘she is a beaste’ and that ‘she nede not agone aboute to a destryed it for I am as licke a man as enye of hir husbones ware for I woulde never a stored from hir for I would neaver a bene a shamed of it’. The ability of fathers to assume direct responsibility for their illegitimate offspring’s care depended on a range of factors besides willingness – which, it should not be denied, was often clearly lacking.

It is not perhaps coincidental that many of the orders discussed above involving direct paternal involvement of some kind related to men with specific occupational titles that suggest they may have been householders of sufficient substance rather than youths more dependent on the patronage and goodwill of parents or employers – although the distress of Richard Smyth at his mistress’s attempt to destroy their child suggests that not all men in this position automatically looked to flight, denial or protection as the most attractive options.

In the case of married men charged with paternity the action taken would most likely have involved spousal negotiation, with some wives colluding in attempts to have another man named as the putative father of any children born of their husband’s adulterous liaisons and others willing to accommodate them within their own households. A petition by Anne, the wife of John Aldridge, submitted to the Warwickshire sessions in 1657 illustrates the circumstances in which it might have been in a wife’s interest to house another woman’s child, reputedly fathered by her husband.

Protesting against John’s long imprisonment for being the ‘supposed’ father of a child begotten on Bridget Darbey, Anne offered to take the child and ‘breed it up with her own children rather than her husband should lie in prison, she being confident of her husband’s honesty notwithstanding the harlot’s affirmation in the time of her travail’. It was clearly less damaging to the household’s material well-being to take on the burden of an additional child than to suffer the costs of John’s absence, even if this did not vindicate his reputation in the way Anne might have desired.

It should also be remembered that it was not unusual for households to absorb children from former relationships, however unharmoniously, and that fostering arrangements were also commonplace, providing a context in which the boundary between legitimate and illegitimate children could be blurred. Over the course of the seventeenth century there was, however, a subtle shift in the dynamics governing the negotiation of paternal responsibilities towards and involvement with illegitimate offspring as the intervention of parish authorities became more routine regarding arrangements for the care, education and (most pressingly) the maintenance of the poor children who were deemed a threat to parish rates.

This has already been charted with reference to the practice of placing pauper children as apprentices, which became increasingly commonplace from the early seventeenth century and which reflected the growing scepticism of parish authorities about the ability of poorer parents to socialise as much as provide for their children. Conversely, the power of parish officers to place children in foster care (on account of their poverty or parental deprivation) could also constitute a form of patronage to the receiving households through the provision of a welcome source of labour, income and claims to civic entitlement.

In Southampton, for example, widow Grundie promised to take in an orphaned child until he was old enough to be bound apprentice to her son, ‘[i]n Considerac’on whereof she was p[ro]missed that she should contynewe Alehowse keeping’ in addition to receiving the sum of 20s, while a porter, Thomas Pitties, took in a child ‘at his owne charges’ on condition that he, his wife and the boy had ‘a spare Roome in the lower Almeshowse’. The transfer of parental roles in such cases could be informed by distinctions between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor and often involved the subtle redistribution of scant resources between them.

Just as ‘marriage and family formation … was a privilege rather than a right’ in early modern England, with some parish officers actively preventing nuptials between couples of limited means, fitness for fatherhood was also judged in socio-economic terms, and this was of particular relevance in cases of illegitimacy in which parish overseers became involved. During the first half of the seventeenth century, the numbers of orders requiring fathers’ direct paternal involvement in or responsibility for their illegitimate offspring’s care diminished markedly.

Instead, it became routine to demand weekly maintenance payments from putative fathers in cases when officials were not satisfied that an illegitimate child would be provided for either by a one-off payment of a lump sum and/or a bond supported by sureties saving the parish harmless. Increasingly, as the mechanisms for administering poor relief became established at the level of the parish, these payments were channelled through the overseers of the poor. In Warwickshire, for example, maintenance payments from fathers were less often paid directly to their children’s carers but were increasingly administered and redistributed by parish officials over the course of the seventeenth century.

This occurred not only when the parish authorities took on responsibility for arranging a child’s care (perhaps after the return to work, death or desertion of its mother), but also even when the child remained in the mother’s hands. Besides a cluster of cases during the Interregnum in which the bench ordered maintenance to be paid directly to the child’s mother or foster carer, and two cases involving men of substantial means (one a gentleman and the other settling with a lump sum), overseers of the poor were increasingly specified as the recipients and distributors of payments.

…Diminished paternal involvement in such cases should not therefore be ascribed to the elevation of maternal above paternal bonds, since it was most likely the cost-effectiveness of maternal breast-feeding (compared with the expense of a wet nurse) that lay behind parochial pressure on mothers of chargeable illegitimates to keep their children. Divesting putative fathers of paternal responsibilities beyond maintenance stemmed from the assumptions of ‘civic fathers’ (so described and documented by Patricia Crawford) that poor men ‘lack[ed] the masculine virtues of independence and autonomy’ and were to be treated themselves ‘as children who required paternal supervision’.”

- Alexandra Shepard, “Brokering Fatherhood: Illegitimacy and Paternal Rights and Responsibilities in Early Modern England.” in Remaking English Society: Social Relations and Social Change in Early Modern England

#renaissance#history#english#class#alexandra shepard#remaking english society#jacobean#caroline era#bastards

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Princess Charlotte of Wales (daughter of George IV and Caroline of Brunswick, not Prince William and Kate Middleton) married Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, future King of the Belgians and uncle to Queen Victoria, in London on 2 May 1816. As the heiress presumptive to the throne and the woman who should have been Queen, if not for her untimely death the following year, her wedding was the social event of the decade and she needed a dress fit for a Princess in order to match the occasion. She had one.

In this royal fashion history documentary from History Calling we look at one of the earliest surviving royal wedding dresses in British history which was recently on display in the Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace. Despite the increasing popularity of white wedding dresses at the time of her nuptials, Charlotte wore silver silk and satin overlaid with lace and embellished with shell motifs. We’ll trace her dress’s journey from its creation by the Princess’s dressmaker, Mrs Triud of Bolton Street, to the day Charlotte wore it, to what happened to it after her death and how it came to be in its present home. By comparing photographs of the dress as seen today to historical descriptions and a picture of it from 1816, we’ll see how well the current gown matches early 19th century fashions, examine how much of the original garment is left and ask whether this unique piece of dress history can really be called the wedding dress of Princess Charlotte.

#princess charlotte#princess charlotte augusta#princess charlotte of wales#regency era#george iv#royal wedding#regency fashion#regency#caroline of brunswick#british royal family#british monarchy#Youtube

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oooh drawing requests! Neat! How about…Caroline (SC or vanilla, dealers choice) but in whatever outfit you currently have on? Or if not that, maybe your favourite outfit? Show off a bit of your own fashion sense!

What do you do when the prompt is for whatever you have on or your favorite outfit, but the favorite outfit is the Caroline outfit in your wardrobe? Pick a secret third thing: my second favorite outfit, my Star Trek uniform, which I always have in my closet in case there’s a con and I have no other ideas on what to wear.

Let’s be real though: Caroline looks sharp in this uniform yes, but she is NOT starfleet material lmao. She’s probably broken several Federation laws by now…

#This is so stupid lmao but ask and ye shall receive#SC Caroline not in lab coat for once! Let it be known she does wear other things. But NOT this lol#portal#portal 2#caroline portal#Sc caroline#schrödinger’s cave#art request#Sc#Star trek#I had a big Star Trek era about six years ago#My art#star trek voyager

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I tried to look up with whom Caroline Bonaparte had affairs and I found this website through my research and I don't know how to feel about this because these comments are not detailed and objective enough for me EVEN THOUGH there are sources mentioned at the end. With all of this in mind, I wanted to ask you all if you know more about these points and if you can confirm to have read about these incidents:

Let's look at some points which let me be confused, shall we?

1. Did Lannes and Caroline ever have a relationship/situationship?

I was more confused than informed after reading these two sentences. Specifically the "unless it was him" part because I read it as if Napoleon made an exception for Lannes which he didn't? The structure of the sentence doesn't make any sense for me. At the same time, English is my third languages. Maybe I just need to read through my grammar books again and study... All of this aside, did they really have something going on?

2. Naps slapping Achille

I heard about the incident of Naps pulling at Achille's ear once but just randomely mentioning this was ???? And the thing is, this wasn't elaborated at all. When did this happen? How did this happen? How did Murat and Caroline react? I can imagine Murat getting quite protective. This incident is described as the Bonapartes disputing about something and then Napoleon slapping his nephew out of nowhere. And that's it...

3. Was Caroline really "thrilled" about the idea of staying Queen?

Pls, let me explain: I am aware of Caroline's ambitions but the verb "thrilled" sounds wrong in my eyes because, as far as I am concerned, it contains the fact that Joachim, the father of her four children, would be dead. She sounds like as if Murat didn't mean anything to her and... that wasn't the case, was it? I am open for corrections. I really want to learn.

4. This... just isn't true.

If I remember corectly, Murat's and Napoleon's relationship wasn't the best already (before Russia) because Murat wanted to reign in Naples and not to be a puppet of Napoleon.

Caroline and Murat themselves went through big highs and very big lows in 1810... i. e., Caroline went through a miscarriage.

5. Murat's indecisiveness considering leaving Napoleon's side after everything..

Gahwd, whoever wrote this, your choice of words is terrible. He wasn't an idiot. He was humane. . _.

6. Did all of the siblings really blame Caroline for everything that happened to Naps? As if they weren't done with his bullshit too... you can't tell me that Joseph wasn't just done after the peninsular war.

Why on earth would Napoleon blame Caroline for Russia? She wasn't there? In addition to that, Naps was a realist who liked to take risks and had ambitions. He is not delusional... 😭🤡

In conclusion: I am confusion.

#I am confusion#napoleon bonaparte#napoleon's marshals#joachim murat#napoleonic era#caroline murat#napoleon's family#jean lannes#Achille Murat

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think something you run into with specifically male characters that I never see with any other characters is when the AUs reach a fever pitch crescendo critical mass zenith and people just staring going hard into the selfcest side of shipping, a la Oncelercest and Sanscest.

I'm not saying it's exactly a problem but gender equality denotes we need to start doing this with characters besides twinks and skeletons

#i do respect that this would require#this website to absolutely lose their minds about a woman the same way they lose their minds#about the tumblr man of the week#but i do think it's possible#this was brought on by something specific but i will not be explaining#i want 50 glados/ceo caroline/test runner carolines on my desk by monday morning#mla format#slight amendment i did forget people were doing this#with pokemon mikus for a bit#a golden era

15 notes

·

View notes