#russia 1812

Text

Ida meets Ney in Russia

I dimly remember that somebody (Cadmus?) mentioned they wanted to read more from Ida. So here’s a brief snippet of Ida – for once – getting in trouble with her hero, of Ney scolding her and … being jealous of Eugène?

The meeting takes place somewhen in late 1812 or early 1813, as much as it’s possible to tell from Ida’s chronological rollercoaster ride. In any case, after or at the end of the Russian retreat. Because of course Ida had joined the Russian campaign as well.

And not only she. If any tumblerinas here plan on learning how to time travel and want to go back to see the Grande Armée march towards Moscow, they don’t need to worry about incognitos. Most likely they would barely be noticed, as apparently there were wagonloads of groupies following their heroes around.

Okay: four. But that’s only those ladies Ida travelled with. Plus, two of them died on the way back.

Ida was particularly fond of a Polish-Lithuanian girl named Nidia, as madly in love with general Montbrun as Ida was in love with Ney. Not that either of the two got to see their idol much during the march. As a matter of fact, the first thing Nidia learned before entering Moscow was that Montbrun had been killed at the battle of Borodino. Other than that, Ida claims to have had a bad feeling about this city from the start:

As we entered Moscow, occupied at last by our troops, this immense city seemed to us like a vast tomb; its empty streets, deserted buildings and solemnity of destruction were heartbreaking. Despite the pomp of victory, I felt struck by I don't know what new kind of melancholy when I saw it; the flags seemed to me gloomy and almost surrounded by funeral crêpes and black forebodings. We were staying in Rue Saint-Pétersbourg, near the Miomonoff palace, which was soon occupied by Prince Eugène. The sight of this young hero and the cheers of the soldiers, who adored him, gave us back all the illusions of victory.

Okay, so I just added this because it’s so rare to see Eugène receive some praise. (I should also mention that the adored young hero was growing bald at an alarming rate and that his bad teeth were killing him.)

As a matter of fact, Ida claims that Nidia was especially interested in Eugène because he was rumoured to maybe become king of Poland (yes, another candidate). These rumours did really exist, Eugène mentions them in a letter to his wife before the campaign started. (And he also makes it pretty clear that these are just rumours and that he has not the slightest ambition to stay in this country. He may have used different vocabulary than Lannes but he didn’t like the region any better.)

The following night, Ida and Nidia wake up to a burning Moscow and are saved by soldiers of 4th corps. On the retreat, they seem to have followed headquarters as closely as possible, which was their safest bet to stay alive (because where the emperor is, there’s food and firewood and a resemblance of order) but still witness horrible tragedies. After the crossing of the Berezina, they apparently followed the remnants of Eugène’s 4th corps to Marienwerder, before Nidia says goodbye and goes back to defending Poland.

But before, on the way, at Valutina (?), Ida finally sees Ney again

At this point, after the retreat, Ida at least starts to question her decision to follow the Grande Armée around. Or something like that.

I have just recounted my fatigue, my difficulties and my perils in a war beyond human endurance, because of the new aspects it seemed to give to destruction and death. A powerful feeling made me undertake everything and endure everything. Why was I going to face the hazards of a campaign? Why was I going to expose the weakness of a woman to the rigours of a climate of iron? In order to obtain yet another glance from the one whose smile had always paid me for my military errands. This look was always like a world offered to my hopes; the dream alone of this reward had made possible all the impossibilities of time, distance, sex and fortune. My life was thus burnt for a few hours, still uncertain. I was giving up everything for a moment in space. Alas! this time, how I was going to regret this moment that had cost me so much to conquer! I had just gambled my existence for a flash of happiness, and this flash, the quickest of my life, became the cruelest.

I had to spend three fatal hours in a miserable shack on the outskirts of Volutina. My dress was so horrible that it was a real disguise. In a person dressed like that, one could hardly suspect a woman. Ney, however, only had to look my way to recognise me. To have been seen was enough to have been discovered. I was about to rush to the front of this first happiness; I was about to testify to the soul of my life how proud I was of this divination of friendship, of this perspicacity of memory, when words of an energy which was far from that of the feeling of which I was possessed, intimated to me the order of the most positive dismissal:

"What are you doing here? What do you want? Go away quickly."

With this address and a few short, curt rebukes about my reckless rage and my fury at following him everywhere, I only had the strength to reply: "It is a rage, indeed, but it is not at least the rage of pleasure or vanity," pointing to my coarse clothes and my face burnt by the sun and faded by fatigue. He took no notice of either the harangue or the costume. He was off and running. His displeasure at seeing me there was so great; he let it out so vividly that I thought he was going to push me back to the opposite bank of the Dniéper in his anger. Stunned by the reception, struck by lightning, I remained motionless for more than an hour, staring at him, thinking I saw him; he had disappeared without paying any more attention to me or worrying about me.

From which we can deduct that Ney was not a reader of Jane Austen novels. Otherwise he would have known that whenever you have behaved in a way that made a woman fall in love with you that’s f-ing your fault, monsieur!

In 1813, when I recalled to Marshal Ney this scene of such violent fury, followed by such cruel silence and abandonment, he told me that he had been so mortally frightened by the extravagance which had pushed me into the midst of so many perils and the licentiousness of an army, that he had even been tempted to beat me. Truth requires me to admit that the temptation had been so strong that he had, I believe, yielded to it a little; it was without his knowing it, for the great passions know neither all they want nor all they do. Anger is therefore still love, since it is as blind as fury.

Girl, get help. Seriously.

When we crossed the Dniéper at Serokodia, I could have had another word with him. A new laurel had just hidden his wrongs and healed my wound. I could have, I wanted to say to him: You have just added to your immortal glory here; you alone have just saved Frenchmen lost in deserts of ice; I would have liked to express to him what all parties repeat today, what posterity will proclaim on the ashes of the brave... But I stuck to the joy of hearing the distant cheers. There was then a little fear in my delirium for him, and I almost have the idea that I idolised him even more by fearing him in that way…

Did I mention the thing about getting help?

Yes, even the reproach was appreciated by my heart, and still seemed to me a tender interest. I found I don't know what pleasure in hearing myself scolded later for my association with Nidia, my marches and counter-marches with the Viceroy's troops. No matter how many times I told the Marshal that Eugène's protection had been focused exclusively on the young Lithuanian girl, and that I had slipped unnoticed into this benevolence, he took it into his head to believe nothing of these sincere protestations. To make him reconsider such a strongly conceived idea would have meant exposing myself to a repeat of the Dniéper order and military correction. I had no intention of trying the same pleasure twice. Finally, he saw the evidence of my attachment, and he found the generosity to prove this belated but strong conviction to me [...]

By calling her his brother-in-arms, by the way. And this, I believe, really meant a lot to Ida.

#napoleon's marshals#michel ney#ida saint-elme#memoirs#napoleon's family#eugene de beauharnais#russian retreat#russian campaign#russia 1812#also#we have a phone call by a certain vice-queen interested in the exact definition of the word “protection” in this particular context

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Berezina Retreat

Between 26-29 November, Napoleon's Grande Armee crossed the Berezina river at Borisov. The losses for Napoleon were great, more than 22,000 French forces would not make it to the other side of the river. Of these casualties, five of them were family members of mine (tragically enough four out of five were brothers as well). Despite the heavy losses, the crossing is seen as a logistic victory as Napoleon with the remnants of his army managed to escape and return to France.

As Napoleon's army reached Bobr, 50km away from Borisov, Napoleon was informed that the bridge at Borisov had been destroyed and the French garrison captured. At the same time a French cavalry brigade discovered a spot where they might be able to cross the river 13km north of Borisov. So on 25th November, the construction of bridges were started by mainly Dutch engineers. The water was close to freezing, only 40 of the 400 Dutch engineers survived the construction of the bridges.

To draw the Russian's attention away from the bridges being built, a diversion was undertaken by Oudinot's corps which led the Russians to believe that the French would either attempt to attack at Borisov and repair the bridge or cross the river south of the place. This resulted in the bulk of the Russian army moving southwards which enabled Napoleon to cross the army.

During the night of 26-27 November, the crossing began but the Russian forces also became aware of the French attempt and tried to return northwards, they were however stopped by Oudinot's battalions. By midday of the 27th, Napoleon and his imperial guard had crossed the river, Marshal Davout's and Prince Eugene's corps also managed to cross the river before the day's end. Meanwhile Marshal Victor's IX corps was given the order to defend against the approaching Russians in order to buy more time for the others to cross. Unfortunately the Dutch regiments were part of Oudinot's forces and most of them sadly died defending the Berezina crossing.

On 28th November, the Russian forces attacked Napoleon's army on both sides of the river. The crossing turned into a completely chaotic stampede as thousands of people, soldiers and stragglers rushed for the bridges. Some of the men tried to swim across the river which was a futile attempt since the water was so cold. There was a mad rush to cross the river since the stragglers knew that the temporary bridges would be destroyed, which happened at 08:00 in the morning on the 29th. tens of thousands of stragglers, both civilian and soldiers, did not manage to cross the river and were now at the mercy of the Russians.

As the bridges were set on fire, the Russians were no longer able to pursue the French army. The French retreat was therefore almost complete, with the Russians no longer on their tail and friendly territory nearby, the remnants of the army had escaped. The casualties were heavy, between 20-30,000 French soldiers died, the IXth corpse was hit particulary heavy as they lost half of their strength trying to protect the bridgehead. Besides the 20-30,000 military casualties, an additional 30,000 noncombatants died as well as result of the crossing and capture by the Russians. 40,000 French soldiers managed to cross the river, with Napoleon's imperial guard still being relatively intact.

Harking back on these relatives of mine, four out of five who died during the Berezina crossing were brothers, but there were other relatives of mine who participated in the Russia campaign, nine to be precies, of the 14 family members who served under Napoleon. Only two out of these nine relatives survived the Russia campaign, which is why those two are my 3rd great grandfathers and the other six are my 3rd great grand uncles as they all died young without partners or children. Here are the names of my relatives who died during the Berezina crossing:

Christiaan Daniels Nijhuis (third great grand uncle), served with the 125é regiment.

Hendrik Reeder (third great grand uncle), served with the 125é regiment.

Christiaan Daniels Nijhuis (third great grand uncle), served with the 125é regiment.

Johannes Reeder (third great grand uncle), Served with the 125é regiment.

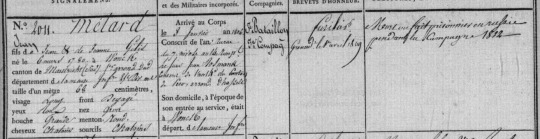

Jean Mélard (fourth great grand uncle), served with the 48é regiment.

Here are the names of my other four relatives who participated in the 1812 Russia campaign:

Christiaan Reeder (third great grandfather), served with the 125é regiment and survived.

Jan Bakhuizen (fourth great grandfather), served with the Imperial guard as a red lancer, he survived though never returned to the army so was marked as missing in action.

Willem van Rijn (fourth great grand uncle), served with the 14é regiment cuirassiers, died during the Russia campaign possibly during the Berezina crossing on 28th November during Doumerc's charge.

Martinus van der Spek (first cousin 6 times removed), served with the 33é lights regiment but did not survive the campaign.

Images include: pictures of the crossing, a red lancer defending his family while crossing, Dutch engineers building the bridge in ice cold water, remains found at the Berezina during ww1 by German soldiers and a document of one of my five relatives who died at Berezina.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon's Ambassador Lauriston approaching Kutuzov in the Tarutino camp.

Maybe someone can translate the dialogue below the pic?

wikimedia

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

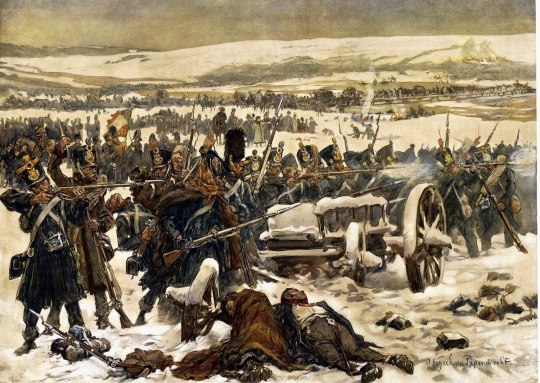

The Retreat from Moscow by Ernest Crofts

#ernest crofts#art#napoleonic wars#russia#france#french#invasion#history#napoleonic#winter#1812#europe#european#french empire#first french empire#soldiers#army#grande armée#snow#landscape

141 notes

·

View notes

Photo

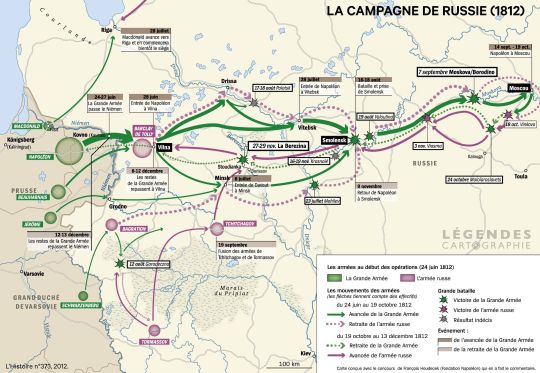

The Russian campaign of Napoleon, 1812.

by LegendesCarto

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Кого я по-настоящему люблю и ценю, так это государя своего почтенного, Александра I. Готов выполнить любой его приказ. Да что приказ! За любимого своего государя готов на смерть идти!

Какое же это высокое и необъяснимое чувство un amour sincère et pur pour le puissant empereur

#war of 1812#19th century#война и мир#russian literature#nikolai rostov#alexander i of russia#alexander i#tsar alexander i#love#i love him#aesthetic

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking into Napoleon's eyes Prince Andrew thought of the insignificance of greatness, the unimportance of life which no one could understand, and the still greater unimportance of death, the meaning of which no one alive could understand or explain.

#reading#books read in 2024#bookblr#books#book photography#book blog#bibliophile#books reading#books and reading#war and peace#leo tolstoy#tolstoy#prince andrew#princess mary#pierre#natasha rostova#petya rostov#sonya rostova#nikolai rostov#classic literature#russian literature#russian classics#a masterpiece#russia#war of 1812#god this was amazing#i loved every second of it#review#five stars#may reads

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Aleksandr Shirokorad:

(Rough) translation:

Thus, the question of whether Napoleon was an aggressor by inflicting a preemptive strike on Russia remains open.

History, as they say, does not tolerate the subjunctive mood, but, in my opinion, it is time for our historians to give an answer, and what would happen if Napoleon married the Russian Grand Duchess, and the tsar would lead the continental blockade in accordance with all the articles of the treaties, Fortunately, our thieves would still find a million loopholes in it.

Finally, the concentration of Russian troops could be carried out several hundred kilometers from the western border, and so on. And here it is more than obvious that it simply would not have occurred to Napoleon to climb into snowy Russia.

Even Academician Tarle warned against drawing analogies between 1812 and 1941 and between Napoleon and Hitler. The Fuhrer needed living space, he planned in advance the destruction of most of the Russian population, forbade his generals in advance to think about the possibility of reviving any kind of statehood in Russia after the destruction of the USSR.

But now Napoleon crossed the Niemen. What are the plans of this “treacherous aggressor”? Napoleon had only one thought - to defeat the enemy and make peace.

#Russian#book pic#Aleksandr Shirokorad#Алекса́ндр Широкора́д#БоГ ВОЙНЫ 1812 ГОЛА Артиллерия в Отечественной вомне#Alexander Shirokorad#Shirokorad#napoleonic#napoleon#napoleonic era#first french empire#19th century#french empire#napoleon bonaparte#history#france#frev#tsar Alexander#tsar Alexander I#Russia#Bog voyny 1812 goda. Artilleriya v Otechestvennoy voyne#book#tarle#Yevgeny Tarle#Тарле#Евгений Викторович Тарле

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dolokhov: Don’t worry, I have a few knives up my sleeve.

Anatole: I think you mean cards.

Dolokhov, pulling knives out of his sleeves: No, I do not.

#source: scatterpatter's incorrect quotes generator#fedya dolokhov#fyodor dolokhov#anatole kuragin#Anatole vasilyvich Kuragin#danatole#great comet#natasha pierre and the great comet of 1812#russia#1800s Russia is sexy#like seriously I love it#you don’t understand#reading war and peace

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kutuzov Prospect by The Internal Expression

youtube

Music by The Internal Expression &

Poems by Denis Davydov &

Paintings by Peter Von Hess &

some episodes from the film

War and Peace by Sergey Bondarchuk

were used in this video.

The track Kutuzov Prospect is dedicated

to the victory of the Russian Army led

by Mikhail Kutuzov in the Russian campaign of 1812

I don't want highest awards

And dreams of conquest

Don't disturb my peace!

But if a fierce foe dares

to oppose us,

My first duty, my sacred duty -

Rise up for our homeland again.

Denis V. Davydov, Elegy IV

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign (French: Campagne de Russie) and in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812 (Russian: Оте́чественная война́ 1812 го́да), was initiated by Napoleon with the aim of compelling the Russian Empire to comply with the continental blockade of the United Kingdom. Widely studied, Napoleon’s incursion into Russia stands as a focal point in military history, recognized among the most devastating military endeavors globally. In a span of fewer than six months, the campaign exacted a staggering toll, claiming the lives of nearly a million soldiers and civilians.

On 24 June 1812 and subsequent days, the initial wave of the multinational Grande Armée crossed the Niemen River, marking the entry from the Duchy of Warsaw into Russia. Employing extensive forced marches, Napoleon rapidly advanced his army of nearly half a million individuals through Western Russia, encompassing present-day Belarus, in a bid to dismantle the disparate Russian forces led by Barclay de Tolly and Pyotr Bagration totaling approximately 180,000–220,000 soldiers at that juncture. Despite losing half of his men within six weeks due to extreme weather conditions, diseases and scarcity of provisions, Napoleon emerged victorious in the Battle of Smolensk. However, the Russian Army, now commanded by Mikhail Kutuzov, opted for a strategic retreat, employing attrition warfare against Napoleon compelling the invaders to rely on an inadequate supply system, incapable of sustaining their vast army in the field.

The fierce Battle of Borodino, located 110 kilometres (70 mi) west of Moscow, concluded as a narrow victory for the French although Napoleon was not able to beat the Russian army and Kutuzov could not stop the French. At the Council at Fili Kutuzov made the critical decision not to defend the city but to orchestrate a general withdrawal, prioritizing the preservation of the Russian army. On 14 September, Napoleon and his roughly 100,000-strong army took control of Moscow, only to discover it deserted, and set ablaze by its military governor Fyodor Rostopchin. Remaining in Moscow for five weeks, Napoleon awaited a peace proposal that never materialized. Due to favorable weather conditions, Napoleon delayed his departure, hoping to secure supplies through an alternate route. However, after losing the Battle of Maloyaroslavets he was compelled to retrace his initial path.

As early November arrived, snowfall and frost complicated the retreat. Shortages of food and winter attire for the soldiers and provision for the horses, combined with relentless guerilla warfare from Russian peasants and Cossacks resulted in significant losses. Once again more than half of the soldiers perished on the roadside succumbing to exhaustion, typhus and the unforgiving continental climate. The once-formidable Grande Armée disintegrated into a disordered multitude, leaving the Russians with no alternative but to witness the crumbling state of the invaders.

During the Battle of Krasnoi, Napoleon faced a critical scarcity of cavalry and artillery due to severe snowfall and icy conditions. Employing a strategic maneuver, he deployed the Old Guard against Miloradovich, who obstructed the primary road to Krasny, effectively isolating him from the main army. Davout successfully broke through, Eugene de Beauharnais and Michel Ney were forced to take a detour. Despite the consolidation of several retreating French corps with the main army, by the time they reached the Berezina, Napoleon commanded only around 49,000 troops alongside 40,000 stragglers of little military significance. On 5 December, Napoleon departed from the army at Smorgonie in a sled and returned to Paris. Within a few days, an additional 20,000 people succombed to the bitter cold and diseases carried by lice. Murat and Ney assumed command, pressing forward but leaving over 20,000 men in the hospitals of Vilnius. The remnants of the principal armies, disheartened, crossed the frozen Niemen and the Bug.

Napoleon’s initial force upon entering Russia exceeded 450,000 men, accompanied by over 150,000 horses, approximately 25,000 wagons and nearly 1,400 artillery pieces. However, the surviving count dwindled to a mere 120,000 men (excluding early deserters); signifying a staggering loss of approximately 380,000 lives throughout the campaign, half of which resulted from diseases. This catastrophic outcome shattered Napoleon’s once-untarnished reputation of invincibility. Sources. French invasion of Russia, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

В создании видео Кутузовский проспект использовались:

Музыка The Internal Expression

Стихи Дениса Давыдова

Картины Петера Фон Гесса

Эпизоды фильма Война и Мир Сергея Бондарчука

Трек Кутузовский проспект посвящён победе Русской армии во главе с Михаилом Кутузовым в Отечественной войне 1812 года

Не хочу высоких званий,

И мечты завоеваний

Не тревожат мой покой!

Но коль враг ожесточенный

Нам дерзнёт противустать,

Первый долг мой, долг священный -

Вновь за родину восстать.

Денис Давыдов, Элегия IV

Оте́чественная война́ 1812 го́да, во французской историографии - Ру́сская кампа́ния 1812 го́да (фр. Campagne de Russie 1812) - военный конфликт между Российской и Первой Французской империей, протекавший на территории России в период с 12 (24) июня до 14 (26) декабря 1812 года. В дореволюционной российской историографии традиционно именовался «нашествием двенадцати языков» (уст. Нашествіе двунадесяти языковъ) в связи с многонациональным составом армии Наполеона.

Причинами войны стали отказ Российской империи активно поддерживать континентальную блокаду, в которой Наполеон видел главное оружие против Великобритании, а также политика Наполеона в отношении европейских государств, проводившаяся без учёта интересов России.

«Масштаб операций в 1812 г. почти невероятен, а потери - военные и гражданские, французских захватчиков и русских защитников - вызывают содрогание даже сегодня, несмотря на несоизмеримо большие потери в двух последовавших одна за другой мировых войнах в XX в.».

На первом этапе войны (с июня по сентябрь 1812 года) русская армия с боями отступала от границ России до Москвы, дав под Москвой Бородинское сражение.

В начале второ��о этапа войны (с октября по декабрь 1812 года) наполеоновская армия маневрировала, стремясь уйти на зимние квартиры в неразорённые войной местности, а затем отступала до границ России, преследуемая русской армией, голодом и морозами.

Война закончилась почти полным уничтожением наполеоновской армии, освобождением территории России и переносом военных действий на земли Варшавского герцогства и Германии в 1813 году (см. Война Шестой коалиции). Среди причин поражения армии Наполеона российский историк Н. А. Троицкий называет всенародное участие в войне и героизм русской армии, неготовность французской армии к боевым действиям на больших пространствах и в природно-климатических условиях России, полководческие дарования русского главнокомандующего М. И. Кутузова и других генералов русской армии.

В 1789-1799 годах во Франции произошла Великая французская революция, закончившаяся приходом к власти Наполеона Бонапарта. Реакцией нескольких крупных монархических европейских стран (включая Россию и Великобританию) было создание серии антифранцузских коалиций, изначально ставивших целью восстановление монархии Бурбонов, но позже принявших оборонительный характер в попытке остановить дальнейшее распространение французской экспансии в Европе. Война четвёртой коалиции закончилась для России поражением русских войск в битве под Фридландом 14 июня 1807 года. Император Александр I заключил с Наполеоном Тильзитский мир, по которому обязался присоединиться к континентальной блокаде Великобритании, что противоречило экономическим и политическим интересам России. По мнению русского дворянства и армии, условия мирного договора были унизительны и позорны для страны. Русское правительство использовало Тильзитский договор и последовавшие за ним годы для накопления сил к предстоящей борьбе с Наполеоном.

По итогам Тильзитского мира и Эрфуртского конгресса Россия в 1808 году отобрала у Швеции Финляндию и сделала ряд других территориальных приобретений; Наполеону же развязала руки для покорения всей Европы. Французские войска после ряда аннексий, произведённых главным образом за счёт австрийских владений (см. Война пятой коалиции), придвинулись вплотную к границам Российской империи.

После 1807 года главным и, по сути, единственным врагом Наполеона оставалась Великобритания. Великобритания захватила колонии Франции в Америке и Индии и препятствовала французской торговле. Учитывая, что Англия господствовала на море, единственным реальным оружием Наполеона в борьбе с ней была континентальная блокада, эффективность которой зависела от желания других европейских государств соблюдать санкции. Наполеон настойчиво требовал от Александра I более последовательно осуществлять континентальную блокаду, но наталкивался на нежелание России разрывать отношения со своим главным торговым партнёром.

В 1810 году русское правительство ввело свободную торговлю с нейтральными странами, что позволяло России торговать с Великобританией через посредников, и приняло заградительный тариф, который повышал таможенные ставки, главным образом на ввозившиеся французские товары. Это вызвало негодование французского правительства.

Наполеон не был наследственным монархом и поэтому желал подтвердить легитимность своего коронования через брак с представительницей одного из великих монархических домов Европы. В 1808 году российскому царствующему дому было сделано предложение о браке между Наполеоном и сестрой Александра I великой княжной Екатериной. Предложение было отклонено под предлогом помолвки Екатерины с принцем Саксен-Кобургским. В 1810 году Наполеону было отказано вторично, на этот раз относительно брака с другой великой княжной — 14-летней Анной (впоследствии королевой Нидерландов). В том же году Наполеон женился на принцессе Марии-Луизе Австрийской, дочери императора Австрии Франца II. По мнению историка Е. В. Тарле, «австрийский брак» для Наполеона «был крупнейшим обеспечением тыла, в случае, если придётся снова воевать с Россией». Двойной отказ Наполеону со стороны Александра I и брак Наполеона с австрийской принцессой вызвали кризис доверия в русско-французских отношениях и резко их ухудшили.

В начале 1811 года Россия, опасавшаяся восстановления Польши, стянула несколько дивизий к границам Варшавского герцогства, что было воспринято Наполеоном как военная угроза герцогству.

В 1811 году Наполеон заявил своему послу в Варшаве аббату де Прадту: «Через пять лет я буду владыкой всего мира. Остаётся одна Россия, - я раздавлю её…».

Согласно традиционным представлениям в российской науке, от последствий континентальной блокады, к которой Россия присоединилась по условиям Тильзитского мира 1807 года, страдали русские землевладельцы и купцы и, как следствие, государственные финансы России. Однако ряд исследователей утверждает, что благосостояние основных податных сословий, в числе которых были купечество и крестьянство, не претерпело существенных изменений в период блокады. Об этом, в частности, можно судить по динамике недоимок по платежам в бюджет, которая показывает, что эти сословия даже нашли возможность выплачивать в рассматриваемый период повышенные налоги. Эти же авторы утверждают, что ограничение ввоза иностранных товаров стимулировало развитие российской промышленности. Снижение таможенных сборов, наблюдавшееся в период блокады, не имело большого влияния на российский бюджет, поскольку пошлины не являлись его существенной статьёй, и даже в момент достижения своей максимальной величины в 1803 году, когда они составили 13,1 млн руб., на их долю приходилось всего 12,9 % доходов бюджета. Поэтому, согласно этой точке зрения, континентальная блокада Англии была для Александра I только поводом к разрыву отношений с Францией.

В 1807 году из польских земель, входивших, согласно второму и третьему разделам Польши, в состав Пруссии и Австрии, Наполеон создал Великое герцогство Варшавское. Наполеон поддерживал мечты Варшавского герцогства воссоздать независимую Польшу до границ бывшей Речи Посполитой, что было возможно сделать только после отторжения от России части её территории. В 1810 году Наполеон отобрал владения у герцога Ольденбургского, родственника Александра I, что вызвало негодование в Петербурге. Александр I требовал передать Варшавское герцогство как компенсацию за отнятые владения герцогу Ольденбургскому или ликвидировать его как самостоятельное образование.

Вопреки условиям Тильзитского соглашения, Наполеон продолжал оккупировать своими войсками территорию Пруссии, Александр I требовал вывести их оттуда.

С конца 1810 года в европейских дипломатических кругах стали обсуждать грядущую войну между Французской и Российской империями. На дипломатическом приёме 15 августа 1811 года Наполеон гневно высказал в адрес России ряд угроз русскому послу в Париже князю Куракину, после чего в Европе уже никто не сомневался в близкой войне Франции и России. К осени 1811 года российский посол в Париже князь Куракин докладывал в Санкт-Петербург о признаках неизбежной войны.

Источник. Отечественная война 1812 года из Википедии - свободной энциклопедии.

#rock#rockmusic#music#musician#Рокмузыка#Музыка#Музыканты#war and peace#warandpeace#peter von hess#petervonhess#Отечественная война 1812#Patriotic War of 1812#French invasion of Russia#War of 1812#Warof1812#Kutuzov#Mikhail Kutuzov#MikhailKutuzov#Denis Davydov#Hermitage Museum#HermitageMuseum#RussianEmpire#NapoleonBonaparte#famousartists#theintexp#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Letter from Laure Junot to her husband (1812)

This is for @impetuous-impulse and @snowv88: As promised, here’s the letter Laure Junot wrote to her husband in September 1812, when Junot was with the Grande Armée in Russia. It’s taken from the book "Lettres interceptées par les Russes", edited by Frédéric Masson (and of which I only own one of those Indian "reprints" that come down to a really bad scan and that I had rightfully be warned of before I bought it 😋. However, these pages are perfectly legible.)

For context: While the publication contains letters that normally did not reach their destination, as they were intercepted during the second half of the Russian campaign, this missive actually had been written during the first months of the invasion and had gotten to Junot safely. However, in his answer, Junot sent it back to Laure, and this answer then fell into the hands of the Russians. (I do not know what they were thinking. Because it’s rather private, and not pretty.)

Laure Junot, at the time when she wrote this letter, happened to be at a spa, at the same time as several other ladies of the court, off-duty empress Joséphine, Julie more-or-less-queen of Spain, Pauline Borghese and the crown princess of Sweden, Julie’s sister Désirée.

The Duchess L. of Abrantès to Junot, Duke of Abrantès. Aix [en Savoie], 7 September 1812

Your last letter caused me to feel both pain and pity. It comes from a fool, and from a fool all the more guilty for being so, as it depends on him to recover his reason and as he refuses to do so as stubbornly as if it meant his eternal misfortune. People dominated by an unfortunate passion are, in the beginning, like sick people who do not want to submit to the vigorous treatment that would cure them. And you want me to feel sorry for you! You want me to pity you! But do you deserve it? Yes, perhaps, but of this pity stripped of all esteem, for you are not the one to whom I promised to offer mine along with all my friendship as the prize for his noble efforts to deserve the name of man, by removing from his heart a feeling that he knows can never be happy. In this respect, you know my way of thinking. It is invariable, and nothing can change it. For many months I have spoken in the same terms to you, and I always will, because it is the language of both my heart and my reason. Perhaps it seems too harsh to you and you find me too frank. A more flirtatious person would no doubt be less so, but is it not better for me to refuse you a poison that would only aggravate your wound and to apply to it a balm that should, according to my desire, remove even the scar and only leave behind of its memory that which could, in the future, spread more charm over our friendship?

Whoa. Now that's a handfull. Please don't hold back, Madame! I have no clue (but would love to speculate!) what kind of "unfortunate passion" she refers to.

For a long time I had this ambition that almost all women have, this unbridled desire to attract attention and admiration, to inspire passionate feelings, to be a kind of divinity for everything around me. I paid for all these adulations with a look or a smile that often troubled the soul of the person to whom they were addressed, without stirring mine. Well, it is with bitterness that I remember this time in my life, and it would seem criminal to me now to encourage or give rise to a feeling that I could not share.

Is this a hint at her own wrongdoings, the affair with Metternich?

I am very happy to think that you are now close to your mother and your son. Give the latter all the time you can spare from your business and the duties you are obliged to fulfil. You have, you told me, great confidence in his tutor. But could strangers ever match a father's eye? Your abilities and your wit put you in a position to watch over his studies very closely yourself. May your loving attention also be focused on his young heart and his feelings. May he one day be able to return to you all the good things he possesses. Believe me, his virtues will be much dearer to him.

This passage confuses me deeply. How can she assume Junot is with his mother and his son in September 1812, when Junot is with the Grande Armée, and the Grande Armée in Russia since June? She must have known that, right? We'll see in the postscript that the ladies were informed of what was going on at the front. Also, the need she feels to interest Junot in his own child is so sad.

I'm leaving for Geneva the day after tomorrow, no matter how much the princesses insist that I stay. I haven't seen my children for three months now, and the need to be closer to them is becoming more pressing every day. I promised to go to Changrenon. I have to spend two days there, and from there I'll go straight to Paris, where I'll be very happy to see and embrace my children, the joy and glory of my life! Ah, when I look back on such moments, I no longer say that it is deprived of any happy future!

Which apparently otherwise she had said. - Also, as she says she will go to Paris to see her children, does that not imply that the son (who was five at the time, according to a footnote) was also there? Does that mean that in the passage above she supposed Junot to be in Paris as well? For that matter, was Junot's mother in Paris, or did she live elsewhere?

I hope that the first letter I receive from you will be good and reasonable, just as I want it to be. Many people take great pride in never changing their feelings. Do the opposite and put your pride in driving away from you those who now dominate you. It is only through weakness, believe me, that we retain an unreasonable inclination, and the word consistency is profaned when applied to madness.

Farewell, believe in my sincere friendship; nothing can diminish it, and one thing can increase it greatly: the certainty of being able to give it to you without fear.

This sounds more like a mother trying to reign in an adolescent. The use of the word "crainte" is also interesting. What precisely does she fear?

You ask me about my health. In truth, I don't know what to tell you, as I am still too ill to go and distress my friends by telling them about my sufferings. I'm still coughing up blood, and in the last six days I've had three new bouts of vomiting. There you have my bulletin.

P.S.: I am reopening my letter to tell you that I am no longer going to Geneva. Yesterday, after writing my letter, I received the bulletin of the 25th [August, of the Grande Armée in Russia, mentioning her husband]. You have probably read it, and you know me well enough to be convinced that this is not the moment I would choose for a pleasure trip. I'm also in a lot of pain; two hours ago, on my way back to the Empress's, I vomited so much blood that it could only be stopped by putting ice on my chest, so now I'm in so much pain that I can't breathe.

Does she try to imply that the army bulletin they received made her feel worse? I think it's the one mentioning Junot not quite being up to the job.

Also interesting: She adresses her husband by the formal "vous" throughout the letter. Which I believe was slowly going out of use but still not unusual in France, especially between spouses of high nobility. Still, this letter makes me feel as if Laure and her Andoche at this point already lived seperate lives. It sounds like one you would write to a husband you had recently divorced.

#napoleon's court#napoleon's generals#laure junot#jean andoche junot#russian campaign#russia 1812#smolensk 1812

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

בדיוק היום בשנת 1812 החל הקרב על קרסנוי.

חיילים צרפתים, שדיממו בחורף הרוסי ונרדפו על ידי חיילים רוסיים, ניסו לחזור לשטח ידידותי. הצבא הגדול של נפוליאון, פעם כוח אדיר, שמנה יותר מ-600 אלף איש בתחילת הפלישה לרוסיה, עד לקרב קרסנוי ירד משמעותית במספרו ונחלש. תנאי מזג אוויר קשים, מחלות והתקפות רוסיות מתמשכות גבו מהצרפתים מחיר כבד.

הצבא הרוסי בפיקודו של מיכאיל קוטוזוב נקט באסטרטגיית אדמה חרוכה ויצא למצוד אחר הצרפתים, כשהוא נמנע מחיכוכים בקנה מידה גדול, אך הפעיל כל הזמן לחץ על הצרפתים הנסוגים.

עם זאת, ליד קרסנוי הרוסים ניסו לחתור למגע עם יחידות של הצבא הצרפתי הנסוג. הרוסים ביקשו לנצל את אי הסדר ואת הפגיעות של חיילי נפוליאון כדי להסב להם נזק מרבי. כתוצאה מהקרב ספגו הצרפתים אבדות רבות, שהחמירו עוד יותר את מצבו הקשה ממילא של צבאם הנסוג.

למרות שנפוליאון הצליח להימלט עם חלק מצבאו, הקרב על קרסנוי הדגיש שוב את הכשלים האסטרטגיים והלוגיסטיים של הפלישה הצרפתית לרוסיה.

#historyistold#היסטוריה#רוסיה#russia#россия#onthisdayinhistory#on this day#france#Napoléon#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#russian empire#1812 war#צרפת#האימפריה הרוסית

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bad ideas in history.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Courage of General Raevsky by Nikolay Samokish

The Battle of Saltanovka depicting General Raevsky personally leading his men into battle, with his two young sons at his side.

#nikolay nikolayevich raevsky#battle of saltanovka#battle of mogilev#napoleonic wars#french#invasion#1812#france#russia#russian#soldiers#art#nikolay samokish#battle#war#europe#european#history#french empire#russian empire#patriotic war#patriotic war of 1812#sons#nikolay raevsky#alexander raevsky#combat#nikolai raevsky#aleksandr raevsky#painting#smolensk regiment

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

We took up our residence in the rancho, or hovel, of a curious old Spaniard, who had served with Napoleon in the expedition against Russia.

"Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited During the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, 1832-36" - Charles Darwin

#book quote#the voyage of the beagle#charles darwin#nonfiction#residence#hospitality#rancho#hovel#spaniard#napoleon#russia#french invasion of russia#russian campaign#second polish war#army of twenty nations#patriotic war of 1812

0 notes

Text

The U.S. frigate United States capturing H.B.M. frigate Macedonian: fought, Octr. 25th. 1812 / lith. & pub. by N. Currier, c. 1835-1856 (LOC).

#polls#napoleonic#napoleonic wars#war of 1812#military history#great comet of 1812#charles dickens#george iv#regency era#regency#louisiana#us history#1810s#1812#age of sail#naval battle#who will win the ultimate 1812 showdown?

654 notes

·

View notes