#traditional ecological knowledge

Text

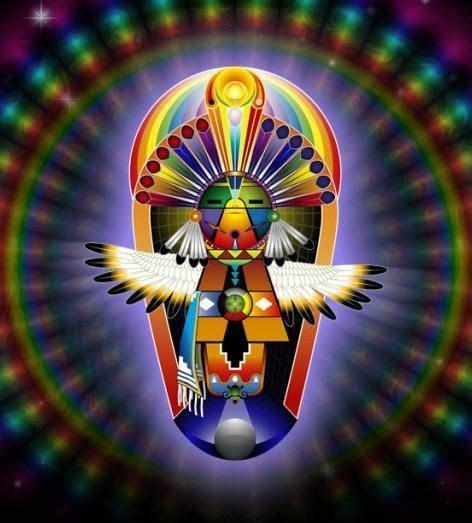

Fire suppression p.1 & p.2: “Flame Retardant” & “Building Potential” Inspired by the PEM's ‘Our Time on Earth’ exhibit

I was gladly surprised to see the exhibit’s various optimistic installations, especially the building materials of the future. As a forestry student I am beginning to understand our relationship to our forests differently. In the US, forest policy which aimed to suppress wildfires has contributed to a century-long build up of fuel that would otherwise have been cleared by controlled burns or small spontaneous ground fires. Indigenous peoples shaped the forests of the Americas to require these controlled burns. More and more I realize that indigenous knowledge and collaboration is a necessary part of the stewardship of future. A concept which is present at large at the museum but also specifically within Our Time on Earth. Getting a ‘sustainable’ amount of lumber from our forest still disregards the health and purpose of these trees to a diverse and complex ecosystem. It is essential that we diversify our building material, to include carbon-negative things like mycelium! Natural resources that are close by, and at hand in our local environment, which doesn’t require chopping down a tree 3000 miles away and transporting it to the US. We need local resources whose collective cultivation lead to a sense of community and collaboration. A better future!

My thanks to lane.m.artin for collaborating with me for p.2!

#acrylic painting#artists on tumblr#PEM#peabody essex museum#climate change#fire suppression#wild fire#TEK#Traditional ecological knowledge#controlled burning#art of mine#solarpunk#is how i would describe the exhibit but listen I am just doing my best and maybe this gallery might even see this piece in it's peripheral#and thats a win#contemporary art

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Popular culture (propaganda) is always like "hunter gatherers lived life on the constant brink of starvation, never knowing when their next meal would come from" and then when you look up the real ethnobotany of the area the descriptions are "yeah, the berries are totally edible but nobody really eats them cause they're kinda bland :/"

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It is simply impossible to overstate both the importance of the buffalo to the Indian people and the damage that was done when the buffalo were nearly wiped out,” ITBC President Ervin Carlson said in a statement. “By helping tribes reestablish buffalo herds on our reservation lands, the Congress will help us reconnect with a keystone of our historic culture as well as create jobs and an important source of protein that our people truly need.”

#bison#buffalo#short grass prairie#conservation#sustainability#economic development#traditional ecological knowledge#ecological restoration#species conservation

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

All my relatives: Exploring Lakota ontology, belief, and ritual. Posthumus DC (2022)

This is a book all about Lakota traditional beliefs and therefore has a lot of information connected to Mitakuye Oyasin. “At the heart of both Lakota religious continuity and innovation is an underlying animist ontological orientation, a basic way of seeing, understanding, and being in the world that extends personhood— in the form of a soul or spirit— to nonhuman life- forms.” This is expressed with ‘Mitakuye Oyasin’ –meaning ‘all my relatives’ or ‘we are all related’, which refers not only to human kinship but also to the relationship shared by all life-forms, both human and nonhuman, and the reciprocal obligations, responsibilities, and mutual respect that naturally extend from it” (14).

This repeats much of the ideas from similar definitions: belief in the connection between all life, relationships, the power the phrase has. It also gives a lot of words to help define these beliefs in academic language. Another important thing to point out is the way mitakuye oyasin is recognized as being part of Lakota innovation; my goal here is to use mitakuye oyasin to an innovation of queer ecology–hopefully add to the conversation.

“The normative cultural values encompassed by mitákuye oyásʾį are the very foundation of kinship, relational ontology, and the overarching interspecies collective, of which humans are only one hoop, one oyáte ‘people, nation, tribe’, in the company of many others. The key constituents of this animist ontology and worldview, of mitákuye oyásʾį, are persons, a category that extends beyond human beings to nonhuman or other- than- human persons. [...] Importantly, the Lakota worldview sees humans as the least knowledgeable and powerful beings, requiring the most aid and pity, upending the common Western biblical assumption that humans have dominion to rule over all other life- forms and subdue the earth (see V. Deloria 1999, 50; 2009, 99– 100). For the Lakotas, the seed of all life is wakʿą ‘sacrality, mystery, divinity’; ́ hence all life- forms share a generalized interiority, whether human or nonhuman.”

This is important information to support my argument. Queer ecology is very critical of Western beliefs and dichotomies that separate humans from nature and thereby present mankind as the ultimate lifeform (anthropocentrism). There are many essays and articles that examine the influence Christianity has had on the colonialist project (Gaard is the first that comes to mind). The Lakota worldview of being the ‘younger siblings’ of creation are supported by science in that ‘humans’ as a 'species' haven’t existed all that long in comparison to other 'species' and like many indigenous cultures, Lakota people knew the key to knowing nature was to learn from the world around us, as the author later confirms:

“Deloria explains that “the oldest traditions say that humans learned politeness and courtesy from the animals. . . . Generations of elders had already observed the behavior of birds . . . and decided that emulating them was the proper way for humans to act” (V. Deloria 2009, 123). Standing Bear (2006a, 56) substantiates this, writing, “The Lakota enjoyed his association with the animal world. For centuries he derived nothing but good from animal creatures. From them were learned lessons in industry, fidelity, and many virtues and much knowledge.” (50-51)

In the author’s footnotes is Vine Deloria’s examination of mitakuye oyasin that is, I feel, a great support of my claim:

“Vine Deloria refers to mitákuye oyásʾį as the ‘Indian principle of interpretation/observation,’ calling it “a practical methodological tool for investigating the natural world and drawing conclusions about it that can serve as guides for understanding nature and living comfortably within it. . . . We observe the natural world by looking for relationships between various things in it. . . . This concept is simply the relativity concept as applied to a universe that people experience as alive and not as dead or inert” (1999, 34). (Posthumus 2022 p219 f)

Queer ecology’s goal in many ways is to critique the ways the Western scientific paradigm has created inequity. Many are seemingly searching for solutions and answers to the problems that have been perpetuated by the colonial empire, supported as it is by western science.

While we must always, always be careful of appropriation and misappropriation–I contend that the solutions are not ones that need to be ‘discovered’ or solved in the way that Western science is so often searching for–advancement, the future…but rather, the answers are in what has always been there…and it’s simply a matter of observation.

#queer ecology#mitakuye oyasin#queer theory#ecofeminism#critical ecology#colonialism#all my relatives#lakota#indigenous studies#postcolonial theory#ecology#science#traditional ecological knowledge#queering ecology#ecosystems#environment#social ecology#long post

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

My goal is to read 30 books this year. I basically stopped reading for fun in grad school so now I'm trying to make up for lost time. There have been lots of fun fiction reads already (this is the year of fantasy romance apperently), but here is my non-fiction stack. Clearly it has a strong theme to it.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

#kelp#good news#science#environmentalism#nature#environment#indigenous people#traditional ecological knowledge#ecosystems#ecosystem engineers

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great mullein, Verbascum thapsus

Native to Europe, Northern Africa, and Asia, and invasive throughout the United States and Australia. It has many traditional uses, including to treat lung ailments and skin irritations. It's also known as "natures toilet paper" due to its large and soft leaves.

#plants#foraging#traditional medicine#nature#naturalist#great mullein#forager#ecologist#ecology#biologist#biology#traditional ecological knowledge#north america#photography#mine#plant#botany#midwest#nature photography

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from Nation of Change:

Ignorance of Native science and the centuries of knowledge it represents is hardly limited to Clear Lake. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s historical inability to distinguish among seven separate species of abalone (well known to coastal tribes, including the Chumash, Ohlone, and Yurok) led to successive waves of over-exploitation. All seven species are currently in trouble; the one remaining viable fishery—red abalone—was shut down in 2017 and will remain so until 2026. In the western United States, which is experiencing the worst drought in 1,200 years, government-mandated fire-suppression plans replaced millennia of Indigenous wildland stewardship that included vegetation management and the intentional burning known as “good fire.” Instead, every year, millions of acres burn, homes are annihilated, and people die in catastrophic wildfires that cost billions of dollars.

With climate change escalating superstorms, heat waves, mega-floods, and drought, Indigenous science can no longer be ignored. For almost two millennia, beginning with local inhabitants of the Mediterranean who provided baseline data for the 600 plants described in Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica in 77 CE, Indigenous peoples have furnished substantive source material for scientific research.

As it turns out, Indigenous knowledge is exceptionally nuanced and deep. It is cumulative, place-based, and acquired largely through observation and experimentation on both large and small scales. Indigenous science—including contributions highlighted in the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Indigenous Climate Hub—is crowd-sourced citizen science taken to the next level, constructed over multiple generations in close relationship with the species, habitats, bodies of water, weather patterns, and other natural phenomena surrounding the observers. It is not superstition or isolated observation or pseudoscience, all misinterpretations stemming from the racist and classist assumptions of Western explorers and ethnographers starting in the 17th century and persisting to the present day.

Indigenous peoples continuously occupying specific ecosystems for centuries or millennia maintain intimate familiarity with how those ecologies function. From the Yanomami in the Amazon to the Iñupiat in the Arctic, Native communities successfully shepherded resources through a combination of deeply held belief systems and sophisticated adaptive management technologies, augmented by the pervasive accumulation, intergenerational transfer, and application of scientific knowledge. This is why Native peoples developed scientific terminology to categorize and characterize species and interspecies relationships—such as birds associated with specific fruiting trees, or the migration patterns of walrus and caribou—long before Western science invented academic fields like agronomy, animal behavior, ecology, climate science, restoration ecology, soil science, and zoology. Traditional ecological knowledge, or TEK, is a scientific term used to acknowledge this wide-ranging body of nature-based expertise.

30 notes

·

View notes

Link

Today, many environmental experts are interested in incorporating learnings from Indigenous societies into climate policies. In part, this is because recent studies have shown that environmental outcomes, such as forest cover, for example, are better in Indigenous protected areas.

It also stems from growing awareness of the need to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights and sovereignty. TEK [ traditional ecological knowledge ] cannot be “extracted.” Outsiders need to show deference to knowledge-holders and respectfully request their perspective.

One idea societies can adopt as they combat climate change is the importance of trust – which can feel hard to come by these days. Young activist Greta Thunberg’s “Fridays for Future” initiative, for example, highlights the ethical issues of trust and responsibility between generations.

Many outdoor enthusiasts and sustainability organizations emphasize “leaving no trace.” In fact, people always leave traces, no matter how small – a fact recognized in Siberian TEK. Even footsteps compact the soil and affect plant and animal life, no matter how careful we are.

A more TEK-like – and accurate – maxim might say, “Be accountable to your descendants for the traces you leave behind.”

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

... traditional ecological knowledge only allows you to scale within the limits of your relational obligations ...

" Deep time diligence is sort of looking at all the systems and the trajectories of these things and doing catastrophic risk analysis, doing all these kinds of things, doing these things collectively. So as a group, everybody’s out there observing what’s happening in nature and what’s happening in your economic systems and communities, and we keep coming together and everybody’s bringing a different data set, and some of these overlap, some of them are contradictory. But in the aggregate, we get a sense, together, with that one big brain—the computational power of a group of people together, you know, big community together doing all this work—that, that works. That’s deep time diligence, because you start building the stories that you need and the Lore that you need and the knowledge that you need for the system as it’s shifting.

And you make sure that you’re moving where it’s going to be, where the authority is going to be, where the livability is going to be, and how it’s going to be. You’re constantly shifting towards that while you’re testing the water, testing the water, testing the water, the whole time, just ahead of you. Like when you’ve got a stick in a stream, and you’ve got that stick ahead of you, and you’re testing the depth— "

“... the key to keeping track of stable innovation processes across multiple generations is story ... it can be more creative than a Cambrian explosion, or more destructive than a nuclear explosion. Story that maintains the continuity of creation requires a lot more work, however, and it develops over time from thousands of data sets held in relationships.”

...

" ... the only way to store data long term, like proper long term, is in intergenerational relationships, where data is stored in narratives, intergenerational narratives. That can last for forty, fifty, sixty thousand years. That can last as long as relations are continued—that data will last. It’s the only safe way to store data in the long term."

...

"Your ignorance is only from the fact that you have a valid data set, but it’s only from one standpoint. But you get all the multiple standpoints and you start to form a picture. You’ve got all these different data points coming back in and it’s computed, like you’ve got dark data processing happening at this big collective level with the best computation mechanism ever—’cause the human brain’s pretty good, but you get like twenty, thirty, a hundred and fifty of those brains together, sharing stories, sharing data sets, and then all of these things just kind of moving and shaping together, something emerges: principles, lores, story, narrative binding all these together. That’s why myth works so well. That’s why myth is so evocative and so enduring; it’s because all these diverse ignorances come together and truth emerges from that ... That’s the only way it can be done."

...

"Wrong story is where instead of all these diverse ignorances coming together to make truth and reality, instead of that, it’s like a small cluster of those ignorances, or just one tiny data point of that ignorance decides: I am truth. I am right. And I’m gonna insist that just this point of view is the right one. And I’m gonna recruit as many people as possible. And together we’re gonna create a compelling narrative, usually a spiritual narrative, straightaway, you know? We’re just gonna draw on mythological tropes from right story everywhere. We’re gonna draw on even proper facts. And you can fact check this—every fact’s gonna be true. But we’re gonna selectively pick those facts and make them fit this narrative. And then we’re gonna project it and we’re gonna insist on it and we’re gonna die on that hill and we’re gonna insist that everybody follow this narrative to the death. And that’s what we’re up against. That’s your wrong story. It’s really powerful because it’s incredibly ignorant, and it’s a way that a minority can subvert and control a majority. It’s a brilliant leverage point. It’s a brilliant psychotechnology. It’s probably the most brilliant invention ever made: the wrong story. Because story is so powerful: story can heal, story can kill. Right story is clunky and it takes time—because it’s supposedto take time."

“[C]ultural knowledge of a region is not just contained in the tribe’s living memory and the sentient landscape, but is also in an enormous continental permanent ledger, in which each place keeps the Lore of other places,”

"[Indigenous governance] ... that’s that big governance model of all this sort of nested, fractal relations and connections of authority. They scale up from every pair, to every pair of individuals, to every pair of clan groups, and then to every four clan groups, then pairing off against each other: and that’s a tribe. And then every pair of tribes coming together and forming a region, and then every pair of regions—and so it keeps fractally scaling up, you know? So that’s our governance model there. And that’s kind of beautiful, and within that there’s Law, L-A-W, and there’s L-O-R-E. And Law is almost like a physical substance in the land. It’s a permanent ledger where the Laws are. They are inalienable, and, well, they last as long as landforms last. So they’re not permanent, but they last for a pretty damn long time."

“This system makes our cultures anti-fragile and acts as a kind of insurance against disasters—the Lore and therefore the Law of any culture can always be restored.”

"Because there’s volcanoes and shit changes, you know? There’s earthquakes, there are rising sea level events that happen, and there are tsunamis—like shit happens. Sometimes there’s a red tide. So, you know, everyone’s eating fish for a couple of weeks out of the sea and they don’t know that they’ve all consumed a poison that’s gonna kill every single person in the whole tribe, you know? Shit like this happens. So you make sure that your Lore is actually kept with other tribes. So there’ll be a few people in another tribe who carry all of your Lore and language and everything else, so if your people get wiped out, that can be repopulated from the other tribe, and that Lore that’s necessary for caring for that landscape and that bioregion—that’s carried on there. So that’s that anti-fragile permanent ledger human network that goes on."

The entire interview is just freaking amazing. I am going to be thinking about this and going back to It again and again, and reaching out with that stick in muddy waters to look for the paths to connect it.

"Like your individual viewpoint—that’s not a reality, that’s a truth for you. And if you’re doing it right, then you’re constantly changing that truth and amending it according to your interactions with others and other truths. Because that truth—that’s your epistemology, and your epistemology is supposed to be a method of inquiry where you’re constantly changing and updating your worldview according to the other data sets that you’re coming across with other people’s story. So that’s your truth, and that has to be constantly changing.

But then your ontology—that’s your reality, and that’s different. Because the reality is empirical and it’s collectively discerned. You need many people to help you discern that and you discern that together. That’s what’s real."

And

"I guess the only reason we’re having these conversations, the only reason we’re writing these books, is because we are hoping that there’s a possibility of a soft landing, where billions won’t have to die in horrible ways, where children won’t be harmed, won’t starve, won’t burn. We’re all hoping for this, and it’s probably wrong story because it’s probably not possible. The probability is that, you know, the systems change is and will continue to unfold in ways that are fairly catastrophic. Most of the people in the world right now are really feeling it, and are really in Armageddon, and in incredible suffering and upheaval and fear and death and all the rest. That’s most of the people in the world. You and I don’t notice it, because we’re living in these first world countries. It’s like, most of the world’s already burning, man. We’re past the tipping point. Probably need to start putting together the cautionary tales that are gonna carry everyone forward into the future and make sure this shit doesn’t happen again. With whatever stable system emerges from this, it probably won’t emerge in nice ways."

#deep time diligence#relational obligations#collective knowledge#aggregate sense#Lore#traditional ecological knowledge#intergenerational narratives#long post#podcast#transcript

0 notes

Video

youtube

#fave#controlled burns#controlled fires#indigenous practices#native american practices#colonization#traditional ecological knowledge#indigenous science

1 note

·

View note

Text

TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE (TEK)

Unlock ancient wisdom with Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Explore the fusion of indigenous insight and modern science for sustainable living.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), also known as Indigenous Knowledge or Native Science, refers to the evolving knowledge acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment.

For a long time, TEK based on native peoples’ experience in dealing with nature and natural resources for thousands of years have been overlooked by the modern…

View On WordPress

#climate change#economy#environment#esg#native science#natives#society#sustainability#tek#traditional ecological knowledge#wisdom

0 notes

Text

#have some TRUTH#Truth--Healing--Reconciliation#living cultures#since time immemorial#‘Namgis#Mowachaht/Muchalaht#canoe runs#grease trail#oolichan trail#Wa's#Kwakwaka‘wakw#deep history#traditional ecological knowledge#knowledge keepers#science#land back#THR#indigenous people#indigenous land#orange shirt day#history#BC

0 notes

Text

Eluding Capture: The Science, Culture, and Pleasure of “Queer” Animals by Stacy Alaimo (final)

Eluding Capture

“A universe of differing naturecultures, propelled by the pursuit of pleasure as well as other forces, can hardly serve as a foundation for biological reductionism, gender essentialism, heteronormativity, or models of human exceptionalism” (64).

Researchers (Vasey et al) in their investigation of female-female mounting behavior concluded that this behavior is ‘female typical’ and not some attempt at executing ‘male mounting behavior’. “The macaques may remind us of Judith Butler’s argument that homosexuality is not an imitation of heterosexuality” (65).

Most feminist theory distinguishes between sex and gender, positing ‘gender’ as cultural, and thus solely a human construct (65). But Roughgarden, on the other hand, sees gender in nonhuman animals, defining it as “the appearance, behavior, and lived history of a sexed body” (2004, 27) (65). Many species have more than three genders.

The white throated sparrow apparently has “four genders, two male, two female”—these genders are distinguished by either a white stripe or a tan tripe and correspond to aggressive an territorial versus accommodating behaviors. 90% of the breeding involves a tan stripe bird (of either sex) with a white stripe bird (of either sex) (9) (65).

The call by researchers like Haraway to see animals as ‘other worlds, replete with significant otherness’ (2003, 25) is useful when trying to make sense of the sheer multitude and complexity of animal cultures that don’t fit within human—even feminist, even queer, models. These ‘queer species’ are queer in a multitude of ways but rarely do any of them correspond to modern categories of gay or lesbian.

Queer ecologists such as Roughgarden and Bagemihl argue that “many non-Western cultures have a greater knowledge of and appreciation for the sexual diversity of the nonhuman world” and that “contemporary theoretical accounts of sexual diversity pale next to both the scientific account of animal sexuality and knowledge systems of particular indigenous groups, who recognize sexual diversity” (66).

“The animal world—right now, here on earth—is brimming with countless gender variations and shimmering sexual possibilities: entire lizard species that consist only of females who reproduce by virgin birth and also have sex with each other; or some multigendered society of the Ruff, with four distinct categories of male birds, some of whom court and mate with one another; or female Spotted Hyenas and Bears who copulate and give birth through their ‘penile’ clitorides, and male Great Rheas who possess ‘vaginal’ phalluses (like the females of their species) and raise young in two-father families; or the vibrant transsexualities of coral reef fish, and the dazzling intersexualities of gynandromorphs and chimeras. In their quest for ‘postmodern’ patterns of gender and sexuality, human beings are simply catching up with the species that have preceded us in evolving sexual and gender diversity—and aboriginal culture have long recognized this” (1999, 260-61)( 66).

Despite our endless attempts at rationalization and categorization and trying to make sense of the world, the sheer diversity and multiplicity among animal sexuality and gender, sex, reproduction and childrearing still makes our minds boggle. These moments of wonder ignite the sense that suddenly the world is not only “more queer than one could have imagined, more surprisingly itself, meaning that it confounds our categories and systems of understanding”….queer animals elude perfect modes of capture. By doing so, “queer animals dramatize emergent worlds of desire, action, agency and interactivity that can never be reduced to a background or resource against which the human defines himself” (67).

“Is the diversity of sexual behavior that we can observe in nature anything other than mindbogglingly beautiful?” (Homosexual Behavior in Animals: An Evolutionary Perspective by Volker Sommer, 2006 370).

“Nature’s inventiveness far outruns our meager ability to categorize her productions,” and “the sheer inventiveness—exuberance—of nature overwhelms” (68).

“World is crazier and more of it than we think” (Louis MacNeice)

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science. He whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed” (Albert Einstein)

Sexual diversity in nature, is not only interesting from a scientific standpoint but these phenomena are also ‘capable of inspiring our deepest feelings of wonder and our most profound sense of awe’ (1999, 6) (68). Which the writer hopes will inspire greener politics and greater interest in the topic of 'significant otherness' in nonhuman animals.

This brings to mind for me, the concept of Wakan Tanka; The Great Mystery. Wakan Tanka is a Lakota concept of all that is still a mystery, that cannot be understood, and the great beyond—the cosmos and all that is not known yet here on Earth. I connect this to the previous text because to me, the indigenous people have always had this sense of appreciation, wonder and love for the mysterious and the diversity of our world.

#queer ecologies: sex nature politics desire#queer ecofeminism#critical ecology#animal sexuality#sexuality#queer animals#queer ecology#ecofeminism#queer theory#ecology#wakan tanka#biodiversity#indigenous peoples#indigenous cultures#traditional ecological knowledge#environmental politics#environmentalism#heteronormativity

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Willamette Valley of Oregon, the long study of a butterfly once thought extinct has led to a chain reaction of conservation in a long-cultivated region.

The conservation work, along with helping other species, has been so successful that the Fender’s blue butterfly is slated to be downlisted from Endangered to Threatened on the Endangered Species List—only the second time an insect has made such a recovery.

[Note: "the second time" is as of the article publication in November 2022.]

To live out its nectar-drinking existence in the upland prairie ecosystem in northwest Oregon, Fender’s blue relies on the help of other species, including humans, but also ants, and a particular species of lupine.

After Fender’s blue was rediscovered in the 1980s, 50 years after being declared extinct, scientists realized that the net had to be cast wide to ensure its continued survival; work which is now restoring these upland ecosystems to their pre-colonial state, welcoming indigenous knowledge back onto the land, and spreading the Kincaid lupine around the Willamette Valley.

First collected in 1929 [more like "first formally documented by Western scientists"], Fender’s blue disappeared for decades. By the time it was rediscovered only 3,400 or so were estimated to exist, while much of the Willamette Valley that was its home had been turned over to farming on the lowland prairie, and grazing on the slopes and buttes.

Pictured: Female and male Fender’s blue butterflies.

Now its numbers have quadrupled, largely due to a recovery plan enacted by the Fish and Wildlife Service that targeted the revival at scale of Kincaid’s lupine, a perennial flower of equal rarity. Grown en-masse by inmates of correctional facility programs that teach green-thumb skills for when they rejoin society, these finicky flowers have also exploded in numbers.

[Note: Okay, I looked it up, and this is NOT a new kind of shitty greenwashing prison labor. This is in partnership with the Sustainability in Prisons Project, which honestly sounds like pretty good/genuine organization/program to me. These programs specifically offer incarcerated people college credits and professional training/certifications, and many of the courses are written and/or taught by incarcerated individuals, in addition to the substantial mental health benefits (see x, x, x) associated with contact with nature.]

The lupines needed the kind of upland prairie that’s now hard to find in the valley where they once flourished because of the native Kalapuya people’s regular cultural burning of the meadows.

While it sounds counterintuitive to burn a meadow to increase numbers of flowers and butterflies, grasses and forbs [a.k.a. herbs] become too dense in the absence of such disturbances, while their fine soil building eventually creates ideal terrain for woody shrubs, trees, and thus the end of the grassland altogether.

Fender’s blue caterpillars produce a little bit of nectar, which nearby ants eat. This has led over evolutionary time to a co-dependent relationship, where the ants actively protect the caterpillars. High grasses and woody shrubs however prevent the ants from finding the caterpillars, who are then preyed on by other insects.

Now the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde are being welcomed back onto these prairie landscapes to apply their [traditional burning practices], after the FWS discovered that actively managing the grasslands by removing invasive species and keeping the grass short allowed the lupines to flourish.

By restoring the lupines with sweat and fire, the butterflies have returned. There are now more than 10,000 found on the buttes of the Willamette Valley."

-via Good News Network, November 28, 2022

#butterflies#butterfly#endangered species#conservation#ecosystem restoration#ecosystem#ecology#environment#older news but still v relevant!#fire#fire ecology#indigenous#traditional knowledge#indigenous knowledge#lupine#wild flowers#plants#botany#lepidoptera#lepidopterology#entomology#insects#good news#hope

4K notes

·

View notes