Text

Maria-Margaretta | she makes all things good. 2023

Billboard Exchange co-presented in Saskatoon, SK by AKA Artist-Run, Hamilton Artists Inc., and PAVED ArtsBillboard at 424, 20th St W, Saskatoon, SK

"How do we care for objects and the stories they hold? Artist Maria-Margaretta explores generational relations by considering the ways in which objects are created, kept, and passed down. Her photographic billboard, she makes all things good, reflects on her homelands and ancestral lineage through the transformative power of objects.

The image consists of three objects: an axe centerpiece held by a hand wearing beaded white gloves, placed against a canvas tent. Margaretta collaborated with Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley to create a sheath for the axe, adorning the object with delicate beadwork as a gift for their young daughter. The axe is a well-used family tool recovered on Pawis-Steckley’s nan’s beach on Wasauksing First Nation. Design elements on the sheath reference and honour their Métis and Anishinaabe heritage and shared journey as parents. Meanwhile, the elbow-length white gloves, beaded by Margaretta for her great great grandmother, embody the Michif matriarchs whose labour in raising families upholds Métis nationhood. The worn, olive-coloured tent belonging to Margaretta’s grandfather sets a warm and earthy tone to the image, reminiscent of her ancestral homelands in St. Louis, Saskatchewan. Together, the axe, glove, and tent carry the past into the present, envisioning new worlds for holding and dreaming with their daughter. "

#indigenous contemporary art#indigenous art#contemporary art#metis art#contemporary metis art#metis artist#maria margaretta#indigenous beadwork#metis beadwork#beadwork#contemporary beadwork

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Catherine Blackburn | Scooped (detail). 2017

Catherine Blackburn was born in Patuanak Saskatchewan, of Dene and European ancestry and is a member of the English River First Nation. She is a multidisciplinary artist and jeweller, whose common themes address Canada's colonial past that are often prompted by personal narratives. Her work merges mixed media and fashion to create dialogue between historical art forms and new interpretations of them. Through utilizing beadwork and other historical adornment techniques, she creates space to explore Indigenous sovereignty, decolonization and representation.

#catherine blackburn#scooped#sixties scoop#60s scoop#millennial scoop#indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#contemporary art#beading#photography#contemporary beading#indigenous beadwork#Contemporary Photography#indigenous photography#mixed media#indigenous mixed media#Dene artist#contemporary dene art#dene art

315 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Annie Pootoogook | Lovers’ Embrace. 2004

I keep coming back to Annie. An incomparable artist and storyteller. She is deeply missed but her genius, care and strength lives on through the worlds she drew.

#annie pootoogook#inuit#inuit art#contemporary inuit art#indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#drawing#contemporary drawing#inuit drawing#indigenous drawing#pencil crayon#lovers embrace

524 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ogimaa Mikana. Don’t be shy to speak Anishinaabemowin when it’s time. Bayfield St., Barrie, Ontario; Biskaabiiyang. North Bay, Ontario; Untitled (All Walls Crumble). Ottawa, Ontario; Anishinaabe manoomin inaakonigewin gosha. Peterborough, Ontario.

Ogimaa Mikana is an artist collective founded by Susan Blight (Anishinaabe, Couchiching) and Hayden King (Anishinaabe, Gchi’mnissing) in January 2013. Through public art, site-specific intervention, and social practice, we assert Anishinaabe self-determination on the land and in the public sphere.

The Ogimaa Mikana Project is an effort to restore Anishinaabemowin place-names to the streets, avenues, roads, paths, and trails of Gichi Kiiwenging (Toronto) - transforming a landscape that often obscures or makes invisible the presence of Indigenous peoples. Starting with a small section of Queen St., re-naming it Ogimaa Mikana (Leader's Trail) in tribute to all the strong women leaders of the Idle No More movement, the project hopes to expand throughout downtown and beyond.

“The Anishinaabeg endure. We do so through settler colonial time, and across space. We do so in contention. Untitled (All Walls Crumble) considers this movement. To be Indigenous in the city is so often a struggle for recognition, to be seen, and to resist the erasure that is common in Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, etc. Yet with recognition also comes appropriation and co-optation. In this unease, we consider the benefits of erasure, or at least, covert movement.

Inspired by stories of our relatives and ancestors counting coup, and Basil Johnson’s description of warfare more generally, the Ogimaa Mikana Project considers the tension between visibility and invisibility to challenge settler colonial logic. Against a crumbling wall holding up Ottawa’s major highway - scheduled for demolition and replacement - we draw attention to the ways the settler state recycles itself, and by extension, affirms its legitimacy. We see it and resist in provocative ways that mirror a there/not there presence.

Against this crumbling wall, we reclaim space for an anti-recognition: to speak to each other, as Anishinaabeg, as communities pushed out by gentrification, as the colonized, and offer a refrain and a sign of defiance: “Wakayakoniganag da pangishin. Nin d'akiminan kagige oga ahindanize.”

#Ogimaa Mikana#susan blight#Hayden King#anishinaabeg#anishinaabe#Anishinaabe artist#anishinaabeg artists#Anishinaabe Art#indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#contemporary art#public art#place-naming#intervention#art intervention#contemporary anishinaabe art#indigenous collective#indigenous artist collective#Anishinaabemowin

855 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Justine Woods | I love you as much as all the beads in the universe: a garment-based inquiry into re-stitching alternative worlds of love. 2021

Top: “We carry our homeland(s) close to our heart. (front view)”; Middle: “We carry our homeland(s) close to our heart. (trout filleting detail)”; Bottom: “Our bodies our stitched with 193 years of diasporic love (back detail of beaded Drummond island.)”

love you as much as all the beads in the universe: a garment-based inquiry into re-stitching alternative worlds of love “engages with a praxis of decolonial love through garment construction and beadwork as a practice-based method of inquiry. My research centres decolonial love as methodology with the expressed purpose to physically and conceptually re-stitch alternative worlds that are grounded in ethical practices and based on respect, empathy, reciprocity, consent and love. Engaging in decolonial love as praxis, the artistic production of my MDes thesis re-frames pattern drafting, garment construction and stitching methods within decolonial and relationship-based contexts. This MDes thesis prioritizes, and foregrounds, all of the relationships that make up my identity as an Aabitaawikwe of Penetanguishene, Ontario and centres these relationships as praxis towards building alternative worlds of love that honour, celebrate and mobilize Indigenous internationalism, intercultural solidarity, co-resistance and liberation.”

Justine’s research and design practice centres Indigenous fashion technologies and garment-making as practice-based methods of inquiry toward re-stitching alternative worlds that prioritize Indigenous resurgence and liberation. Her work foregrounds all of the relationships that make up her identity as a Penetanguishene Aabitaawikwe; an identity she has inherited from her family and her Aabitaawizininiwag Ancestors.

#indigenous art#contemporary art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#fashion arts#indigenous fashion arts#indigenous fashion#garments#garment making#design#indigenous design#contemporary design#metis art#metis fashion#contemporary metis fashion#metis artist#Aabitaawikwe#Penetanguishene#justine woods

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ayimach ᐊᔨᒪ, 2022.

ᓀᔭᐤ/Neyaw is Cree for: A Point of Land Jutting onto the Water and is an Indigenous fashion assertion presented as a ready-to-wear capsule collection.

Designer Jason Baerg is an Metis curator, educator, and visual artist. Dedicated to community development, Baerg founded and incorporated the Metis Artist Collective and has served as volunteer Chair for such organizations as the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and the National Indigenous Media Arts Coalition. Creatively, as a visual artist, he pushes new boundaries in digital interventions in drawing, painting and new media installation.

#indigenous art#indigenous fashion#indigenous fashion arts#fashion#fashion arts#contemporary art#contemporary fashion#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#contemporary fashion arts#indigenous contemporary fashion#indigenous contemporary fashion arts#metis art#metis artist#metis fashion#contemporary metis fashion#contemporary metis art#jason baerg#ayimach

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maria Hupfield | Distinctive, Easily Portable, and Often Stolen, (one of three). 2022

Maria Hupfield is a maker, a mover, a connector, an Anishinaabe-kwe of Wasauksing First Nation. Like the artist herself, Hupfield’s work is never static. Her performances, sculptures and installations reference different spans and scales of times. She values expansive exchange over isolation, and inclusion over hierarchy.

“The artworks in the exhibition (Protocol Break) were made or revisited in Toronto during our pandemic lockdown, a time of sadness and alienation for many of us. We were afraid, lonely, cut-off. Divided inside. Yearning for our roots and connections, the forest became a chair. Apartments became tents. Survival is passed down and remembered, thrown forward into the future.Magic is afoot! In a felt slipper. Call home, commune with your mom. Claim your voice from the soft body of an instrument. Ask the children to tell you what they’ve learned, write it down, cut it out and sew it on a rainbow.

-Excerpt from exhibition text by Shary Boyle”

#Maria Hupfield#indigenous art#contemporary art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#Anishinaabe#Anishinaabe Art#Anishinaabe artist#anishinaabe contemporary art#sculpture#contemporary sculpture#indigenous sculpture#felt#felt art#indigenous felt art#felt sculptures#instillation#instillation art#contemporary instillation art#indigenous instillation art#indigenous instillation

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wendy Red Star | Last Thanks. 2006

Wendy Red Star is an Apsáalooke contemporary multimedia artist born in Billings, Montana, in the United States. Her humorous approach and use of Native American images from traditional media draw the viewer into her work, while also confronting romanticized representations.

Using materials like Target-brand Halloween costumes and inflatable animals, Red Star counters the stereotypical trope that all Native American people are "one with nature."

Red Star has exhibited in the United States and abroad at venues including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY), Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn, NY), both of which have her works in their permanent collections; Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain (Paris, France), Domaine de Kerguéhennec (Bignan, France), Portland Art Museum (Portland, OR), Hood Art Museum (Hanover, NH), St. Louis Art Museum (St. Louis, MO), Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minneapolis, MN), the Frost Art Museum (Miami, FL), among others.

#Wendy Red Star#Last Thanks#Apsáalooke#Crow people#Apsáalooke artist#Apsáalooke art#contemporary Apsáalooke photography#Apsáalooke photography#indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#contemporary art#Contemporary Photography#indigenous photography#crow art#crow artist#photography#thanksgiving

326 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jutai Toonoo | Palliqniq. (detail) 2015

“A cutting-edge contemporary artist, sculptor, jeweler and graphic artist, Jutai Toonoo created works that rarely conformed to the traditional assumptions about the style and substance of Inuit art.

Toonoo belongs to the middle generation of Inuit artists who hover somewhere between the old and new worlds of the Arctic, negotiating an identity that is at once introspective and worldly. His work, often enlivened by the use of text, blends traditional and modern themes and provides commentary on social concerns such as isolation, drug and alcohol addiction, the search for identity and contemporary global issues.” Feheley Fine Arts

#indigenous art#contemporary art#Jutai Toonoo#inuit art#contemporary inuit art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#erotic art#indigenous erotic art#inuit erotic art#inuk artist#drawing#contemporary drawing#inuit drawing

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Blake Angeconeb | The Kiss (Gustav Klimt) but Indigenous. 2022

Blake Angeconeb is an Anishinaabe woodlands artist who hails from Treaty 3 territory. His first venture into art began 6 years ago during a fun painting session with his younger niece, which has since launched him into a full-time career as an artist. Blake’s primary practice involves acrylics and multimedia on canvas, blending the school of woodlands art with pop culture references. Blake is a self-trained painter with a growing collection of small and large scale works who enjoys collaborating with other artists. He is part of the Caribou clan and a proud member of Lac Seul First Nation.

#Blake Angeconeb#gustav klimt#The Kiss#Indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#contemporary art#woodlands art#contemporary woodlands art#Anishinaabe Art#Anishinaabe artist#anishinaabe contemporary art#digital art#indigenous digital art#contemporary digital art

203 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mekayla Dionne | Sweets. 2021

Mekayla Dionne is an emerging Métis abstract painter. She was born in 1997 and spent her childhood in a small rural town in Ontario. Her love of art started at a young age, drawing and painting on anything she could get her hands on, and eventually taking it more seriously throughout high-school, in which she had a very encouraging Art Teacher who was a painter herself.

Mekayla’s art is always evolving and shifting from one thing to the next. Currently she is working in large scale abstract paintings primarily with acrylic and oil paint. She uses many layers to create landscape-esque forms and interesting compositions. Her art is intended to be accessible to people of all ages and levels of art knowledge. She creates visual adventures using colour combinations and shapes, as well as creating paths for your eye to travel around the work

#metis art#metis painting#Metis artist#contemporary art#Contemporary Painting#indigenous art#Indigenous painting#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#indigenous contemporary painting#metis contemporary painting#abstract painting#abstract painter#metis abstract art#abstract art#contemporary abstract art

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill | Counterblaste. 2021

Pantyhose, tobacco, thread, charms, plastic flowers, dried flowers, earring beaded by Cheryl L’Hirondelle, running shoes, beads, rabbit fur earrings, and nail polish.

Tobacco is considered essential to physical, social and spiritual well-being in many Indigenous cultures throughout the Americas. Hill, a Métis artist who lives on the unceded lands of the Skwxwú7mesh, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh peoples (Vancouver), grew up using tobacco for gifting and ceremony, and developed an interest in how the practice has survived colonization, criminalization and capitalism. But, for Hill, its Indigenous usage represents an alternative system guided by an ethic of distribution and reciprocity.

“Counterblaste (2021), is a chimeric figure laying on one side. Her eight breasts are swollen – some painfully red – but she rests contentedly as if having just finished feeding her young. Her head is cradled in the nook of an elbow with her lop ears sprawled outwards and her feet, laced into scuffed running shoes that show the wear and tear typical of a busy mother, are tucked behind. The work’s title references a treatise written by King James VI and I in 1604 titled ‘Counterblaste to Tobacco’, a vitriolic pamphlet decreeing a personal distaste for smoking: a habit his fellow countrymen had acquired in the colonies and was fast becoming a favourite pastime. James’s treatise reduces tobacco to its association as a treatment for venereal disease, describing it as ‘a stinking and unsavorie Antidot, for so corrupted and execrable a Maladie’ – accompanied by his blistering condemnations of ‘barbarous people’, rooted in sexualized, racist hate. As a direct affront to the King’s masculine paranoia, Hill’s Counterblaste gives form to an Indigenous body politic that challenges conquest ideologies. The maligned sexuality of Indigenous peoples and the derogation of the tobacco plant are effaced by the gaze of this confident mother.” ( https://www.frieze.com/article/moma-projects-gabrielle-hirondelle-hill-2021-review)

#Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill#metis art#Metis artist#contemporary metis art#contemporary art#indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#installation#metis installation art#tobacco#Counterblaste

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

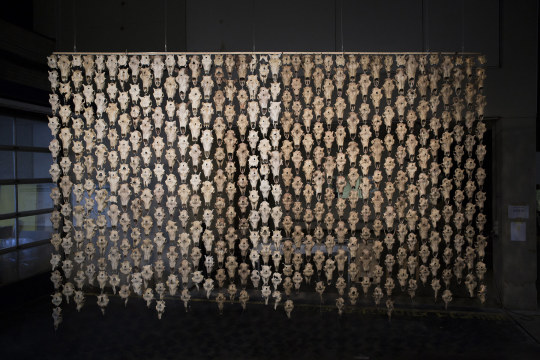

Máret Ánne Sara | Pile o’Sápmi. 2018

“Pile o’Sápmi is a work of art that was created as a protest and a symbol of the Norwegian government’s forced slaughter of reindeer belonging to Indigenous Sámi herders in Finnmark. Máret Ánne Sara created the original work as an installation of 200 reindeer heads outside the Inner Finnmark District Court in February 2016, where her brother Jovsset Ante Sara brought a case against the Norwegian government. Sara sued the Norwegian state to prevent the forced slaughter policies implemented by the Norwegian government, and defend his right as a Sámi reindeer herder to practice his culture. The case sets an important precedent in terms of indigenous rights in Norway and the rights of reindeer herders in particular.

In parallel, Pile o’Sápmi branched into an interdisciplinary art movement. Máret Ánne Sara curates art and artists to raise awareness and further debate about the ongoing struggles for Sámi rights in Norway and the rest of Sápmi. Several of Sápmi’s foremost artists have exhibited and performed work in galleries and in public spaces in Deatnu, Tromsø and Oslo, closely tracking the case as it moves through the legal system.

Their work has brought greater attention to the case, creating spaces and events where politicians, media and the wider public learn more about the principal issues raised by this case and the ongoing infringement of Sámi rights in our contemporary society.

More than 40 artists have donated works of art as part of a lottery to fundraise for Sara’s case, and the social media presence as well as international media has created wide attention to both the artworks and the circumstances of the court case from which the work arose. Pile o’Sápmi has been exhibited internationally at the Documenta14 in Athens and Kassel. The work Pile o’Sápmi Supreme, featuring 400 reindeer skulls, was recently acquired by the National Gallery in Norway.”

https://maretannesara.com/pile-o-sapmi/

#indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#contemporary art#Pile o’Sápmi#sapmi#Máret Ánne Sara#Finnmark#norway#reindeer#sapmi art#sami art#sami artist#sapmi artist#sámi#Sámi art#Sámi artist

360 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maureen Gruben | top: Aidainnaqduanni, Aurora. 2020; bottom: Aidainnaqduanni, Morning. 2020

Inuvialuk artist Maureen Gruben employs an intimate materiality. In her practice, polar bear fur, beluga intestines and seal skins encounter resins, vinyl, bubble wrap and metallic tape, forging critical links between life in the Western Arctic and global environmental and cultural concerns. Gruben was born and raised in Tuktoyaktuk where her parents were traditional knowledge keepers and founders of E. Gruben’s Transport. She holds a BFA from the University of Victoria and has exhibited regularly across Canada and internationally. She was longlisted for the 2019 Aesthetica Art Prize and the 2021 Sobey Art Prize, and her work is held in national and private collections.

#indigenous art#Indigenous artist#contemporary art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#Inuvialuit#inuvialuk artist#Maureen Gruben#polar bear#Aidainnaqduanni#Aurora#Morning#inuvialuit art#contemporary inuvialuit art#inuit art#contemporary inuit art#photography#Contemporary Photography#Archival inkjet#installation#inuit installation

320 notes

·

View notes

Note

where do you find these pieces?

I am an arts workers so some of these works are by artists I know, have worked with or have seen. Some are by artists I learnt of in school, in magazine interviews or reviews, or just generally online. I recently was gifted a calendar that introduced me to a bunch of emerging Indigenous artists who I will be showcasing later in the year.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

How would you define contemporary art?

I use the definition I was taught while at art school studying art history. Contemporary Art means art produced within the past 100 years. This differs to Modern Art, which has been used in many ways, but I was taught describes any work made after 1850. Though I generally try and highlight art produced by working artists, I have a few posts that showcase works from the 50s and 60s too. If you would like to see some older works let me know!

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Peter Robinson | Boy Am I Scared Eh! 1997

Peter Robinson (Ngāi Tahu) has a large multidisciplinary practice that explores ideas such as identity through the installation of manipulated materials, painting, or even intricate sculpture. His career spans 30 years both nationally and internationally. He was one of the first artists to represent Aotearoa at the Venice Biennale in 2001 with Jaqueline Fraser. He also won the Walters Prize in 2008, the top art prize in Aotearoa.

“Peter Robinson’s work from this period is loaded with symbols that confront head-on issues of our colonial history, racism, prejudice and identities. In Boy Am I Scared Eh!, 1997 the spiralling koru (unfurling fern frond) can also be read as a fingerprint – a symbol of a symbol of uniqueness but also as emphasis to the statement it surrounds, as if to poke fun in defiance. This physical marker of identity is netural, but when ideas of identity enter the cultural realm they become complex, contested and loaded. Much of Robinson’s work during this time considered, critiqued and deconstructed that complexity. The text, ‘Boy Am I Scared Eh!’ references Colin McCahon’s 1976 painting, Scared. As young man McCahon once commented: ‘The force of painting as propaganda for social reform is immense if properly wielded . . .’” ( https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/explore-art-and-ideas/artwork/8541/boy-am-i-scared-eh )

#peter robinson#maori#Maori Art#maori artist#contemporary maori art#maori painting#contemporary art#Contemporary Painting#indigenous art#Indigenous painting#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#boy am i scared eh#new zealand#aotearoa#aotearoa art#aotearoa artist

116 notes

·

View notes