Text

Metroid Prime 2 Really Enjoys Wasting Your Time

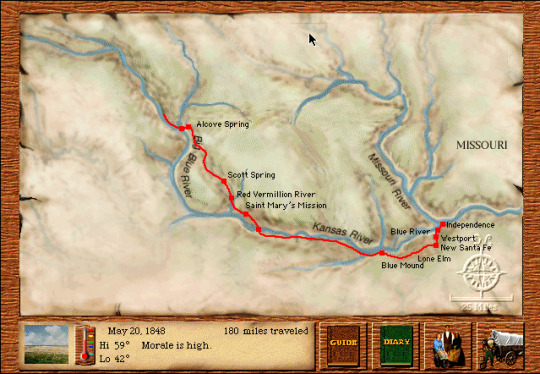

If I’m being completely honest, I’ve always thought the praise that the Metroid Prime series got was overblown. Don’t get me wrong, Metroid Prime, in particular, is a good game, but the series seemed to suffer in ways that the 2D games never did. Most of these issues come down to asking players to scour every inch of every level in order to find a critical item or hidden path forward. That is in the spirit of the classic 2D Metroid games, Super Metroid in particular, but 2D presentation allows for those sensibilities to shine because it doesn’t take all that much effort to examine what’s on screen in a 2D game. Even the map, as intricate as it is, only allows for four directions of exploration. After playing the game for a while, it’s pretty easy to look at a room you’re currently in, compare it to the map, and check out areas that may contain secrets.

When you move that into 3D space yet try to maintain the amount of detail that’s present in the 2D games, you’re going to have a mess on your hands. To solve this problem, Metroid Prime took a very minor component of Super Metroid, the scanning visor, and basically made a whole game out of it, all while trying to remain an action game. Scanning objects is easily the worst part of Metroid Prime. It essentially forces you to crawl your way through an area the first time, stopping every few feet to look around with the scan visor. Scannable items are highlighted in red if you haven’t scanned them before, which is supposed to help you quickly determine what you need to focus on, but so many rooms have numerous items to scan, which destroys the pacing.

Granted, not every item is important, so you can get by without scanning a great deal of the available items, but seeing as progress is often locked behind items you need to scan, or knowledge you gain from a scanned item, you are heavily encouraged to scan anything and everything. When you realize just how much of your time is spent scanning items, you realize how little of it is spent actually exploring, fighting bosses, and having fun.

Yes, many of these chairs have to be scanned in small groups or individually for...some reason.

Metroid Prime 2: Echoes has all of the same problems as Metroid Prime and then really doubles down wasting the player’s time. The biggest change from Prime to Echoes is the introduction of the Dark World. The Dark World concept is pretty much lifted directly out of A Link to the Past, meaning that in order to make progress, you have to hop back and forth between the Light and Dark World in order to discover new areas, obtain new abilities, and change things in one world to impact the other. Conceptually, this is a great idea and it’s actually amazing it took until 2004 for this idea to be brought into the Metroid universe. Unfortunately, the execution is hampered by one extremely important detail: the Dark World actively hurts Samus just by being there.

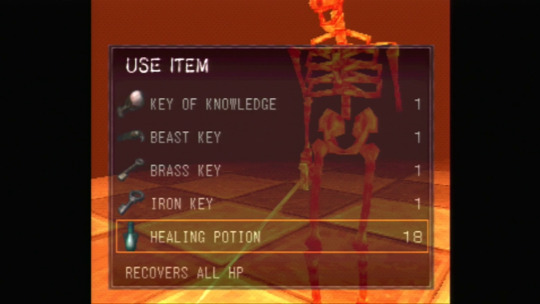

I know there’s a story reason for all this, but it completely ruins the game. Initially, being in the Dark World at all takes a huge toll on your health very quickly, so you can’t spend very long in it. The only protection you get are these little beacons of light that project domes of safety. This, naturally, sets you up for the expectation that you’ll eventually get a suit upgrade that lets you withstand this constant HP drain. This is true, but it doesn’t happen until maybe the last (and most boring) 10% of the game that just has you backtracking through a bunch of areas to get some keys. Before that, you do get one suit upgrade that reduces the damage done, but you still take damage in the Dark World for the vast majority of the game, making exploring far more dangerous than it’s generally worth.

If you know what you’re doing, are good at the game, and don’t face too many issues with combat, you can get through the Dark World areas without losing too much health over time. Unfortunately, I’m not especially great at these games and tend to take a lot of punishment in enemy encounters. Since the game is extremely stingy with regard to its health and ammo pickups, I dread every time I have to go into the Dark World, fearful that I might get stuck out between safety zones or trapped fighting enemies for too long.

Thankfully, you can recover your health in the Dark World by hanging around those safety beacons. Unfortunately, the health restoration is so slow (about 1 HP every second), that you will spend a lot of time standing around doing nothing, waiting for your health to reach a point where you feel confident about going out and fighting or exploring more. I can’t think of a more blatant way to waste the player’s time. First, the suit that reduces the HP penalty in the Dark World should just eliminate the effect altogether. There is no really good reason you couldn’t take damage early on in the Dark World, find the suit upgrade, and then be free to traverse without penalty. I’d prefer that the Dark World not damage you at all, but I get that there is a narrative purpose to this, initially.

You’ll spend a lot of time just standing around in these safe pods, waiting.

What I can’t reconcile is just how slowly your HP regenerates when you’re in a safe zone. The reason it’s so slow is because there are enemies that engage you in rooms that contain these beacons and obviously they didn’t want players to be able to camp out under the beacon and just mindlessly shoot until the enemies died while they faced no serious danger. It seems that a better solution would have been to simply reduce the number of safety beacons a bit, or make sure enemy encounters were in areas that didn’t contain them. That way the threat of exploring would still exist, but if you did get in trouble, you could just backtrack to a beacon, stand around for a few second, then go back out and try again.

Instead, you still have to stand around beacons if you go exploring for too long or take too many hits, and the time spent doing it is drastically extended. Maybe having faster health regeneration would still make the game too easy, but I’d take a game that’s too easy over one that literally stops my progress so I can stand around for an arbitrarily long amount of time, actively making me not want to continue exploring.

Going back to the issue with detail, Prime 2’s map system does little to alleviate the inherent issues with exploring complicated level designs from the first-person perspective. One of the reasons I tend to have gripes with first-person perspective games is because they do a very poor job of mimicking what it’s like to actually see a space with your eyes. Most of this is related to peripheral vision what you can see in your peripheral vision in real life, as well as the fact that you can move your eyes around in your head, shifting your focus, without actually turning your head. You really can’t do that in games because you’re detached from the space by a screen. To look around, you have to physically move your character’s head (the camera) in the direction you want to look. It’s extremely disorienting to me and as a result I often get lost in games, even ones that don’t have levels as intricate as those found in the Prime series.

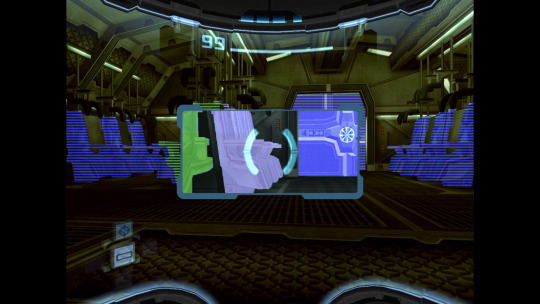

Naturally, there is a map in the game, and it is absolutely vital to navigating the game. However, reading the map is, in itself, a challenge because it, too, is in 3D. Honestly, it pretty much had to be. The levels in Echoes are extremely complicated (needlessly so, I’d say). Of course, it’s the same map that was used in the original Prime, but due to the levels not being as distinct in Echoes as they were in the first game, as well as the fact that you have a complementary map of the same areas to accommodate the Dark World, we’re looking at another area where you end up spending a great deal of time. I can’t tell you how many times I’d walk into a room, even one I’d been before, check the map, go into an adjacent room, then immediately go back to check the map. When you combine the time spent sitting around waiting to regain health and the time spent simply trying to orient yourself in the map (and often fighting with it since you can easily highlight rooms in floors above or below you by accident), it’s easy to see why the game can take around 20 hours to beat, even when really the game should take about half as long.

As I get older, I get a lot more irritated with games that do things simply to waste your time and pad out the play time. You really get the feeling that the changes made to Prime 2 were done specifically to make sure players spent more time with it, even if the quality of that time was drastically diminished compared to the first game. As such, Echoes is a vastly inferior game to its predecessor, and one that isn’t really worth revisiting. And if all the time wasting isn’t bad enough, it also introduced Dark Samus, which I consider the worst thing to ever happen to the Metroid franchise.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Animations in Demon’s Souls Are Ridiculous

youtube

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nitpickery: QTE Button Prompts

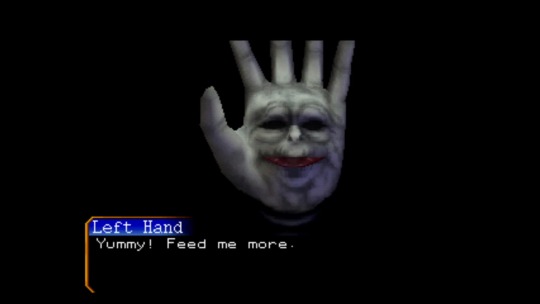

Castlevania: Lords of Shadow is far from perfect. Even so, it’s a game that I’ve played and replayed many times for the reason that it’s a satisfying combat action title. Its flaws tend to be the mildly irritating kind, and thus can be ignored easily enough, especially on multiple playthroughs. There is one aspect of the game, however, which does significantly impact my enjoyment of the game, and that is how it uses button prompts for the quick time events.

For the record, I don’t think quick time events are a particularly egregious offense. When you’re going for a particularly cinematic sequence that would otherwise be impossible given the camera’s normal operation, or if you build in quirky gimmicks into the combat, they can be engaging. No matter you implement them, the trick to pulling them off successfully rests in the consistency of their presentation. Lords of Shadow, unfortunately, completely misses the mark on this front in two very specific ways.

The first issue and biggest issue is the element of randomness to the button prompts. I’ll use the large lycan enemies for my example because I think they demonstrate this most clearly. When you hit a lycan enough times to stun them, they glow gold, letting you know that you can grab them to finish them off. There are two quick time events that you must complete in order to finish them off cleanly. First, you have to press any button once a larger circle shrinks down inside a smaller circle. I never really minded these because it doesn’t matter what button you push, so long as you push something with the correct number of frames. The second part is that you have to mash a particular face button once Gabriel Belmont places his foot on the lycan’s face. The button you need to mash simply depends upon which one the game wants to present to you for that particular sequence.

Circle, this time.

Square, this time, in the same fight.

There is only one reason to use different button prompts to perform the same action, and that is to punish players for not paying close enough attention. This should never be the goal of an action game that explicitly tells you what buttons to press and when. The controller, in the case of Lords of Shadow, is the apparatus through which the player controls Gabriel Belmont. It is essentially an analog for Gabriel’s body. In order for it to work that way, there have to be certain rules to its use. Pressing a button or combination of buttons has to perform a specific action and do so consistently so that the player can understand what they do and control the character successfully. If we go back to Gabriel’s foot on the lycan’s face, no matter how many lycans you grab and do this to, it is inherently the same action. Why, then, do I sometimes have to press A or Cross to do this, and sometimes Y or Circle? You have to do it that way because the developers decided the QTEs should be more like obstacles than methods to directly control Gabriel, sending mixed signals to the player about what the controller’s role in the game actually is.

While it might seem like a minor annoyance to some, I actually think using QTEs in this way subtly undermines the faith that players put in the game overall. I found myself regularly pressing the wrong buttons during normal combat, jumping when I meant to slash, or grabbing when I meant to block, because I was constantly being told by the random button prompts that there was no correlation between the buttons I was pressing and the action I was performing. Lords of Shadow is not the only game that takes this approach, though. You see it in Bayonetta as well, and it’s no less hostile to players there, either.

Bayonetta does have one major leg up on Lords of Shadow’s implementation, though, and that is in the graphical representation of the prompt. Bayonetta presents the buttons within the context of the controller itself. Rather than just an isolated graphic of the button that Lords of Shadow provides, you get a circle with the buttons that you need to press in the positions they would be on your controller. This is a small detail but it helps immensely. At that point, I don’t really even have to recognize the buttons, themselves, rather just the placement. Given that you likely aren’t looking at your controller very often while playing, its small touches like this that can alleviate a problem. Lords of Shadow does go halfway here, and puts the button prompt in a place on the screen that mimics where it would be on the controller, but the button graphic is in complete isolation. Without the controller context, it doesn’t do near enough to help the player identify the button quickly.

I’ll also mention that this problem is more pronounced for me on the Xbox 360 and PC version of Lords of Shadow. When Playing on the PlayStation 3, I found myself confusing buttons less often. I’m not sure if that’s because I just play more games on Sony consoles or what. I thought it might be due to Microsoft and Sega using one letter configuration and Nintendo using another, but I play plenty of Japanese games on PlayStation platforms that swap the confirm and cancel commands between the Cross and Circle buttons. Maybe I’m just illiterate.

Whether or not this kind of issue is a nitpick or not really depends on the person. For me, I think it definitely ventures into fundamental problem territory due to the erosion of trust between the game and the player. However, that very well may be an issue with me and not a more widespread problem. Of course, how you feel about it also probably largely has to do with how you feel about QTEs more generally. I’ve long felt that the line between QTE and just reacting to what’s happening in the game is very thin. Games like Demon’s Souls proved that enemies didn’t even have to flash a certain color or do anything outside their standard animations to clue players in to what they were about to do and how to react.

Meanwhile, Arkham Asylum used specific button prompts and consistent indicators above enemies to let you know when to block and dodge attacks or perform specific moves. Even From Software themselves, danced dangerously close to QTE territory with its warning messages that flash on screen in Sekiro, which surprised me considering how they had relied solely on animations to telegraph enemy behavior in most of their games. But then I remembered From Software also made Ninja Blade, maybe the QTEist game of them all, so I imagine they’ll stick around in some capacity for quite a while yet. If they do, hopefully they learn from the games that did them poorly so that they can at least not hinder the player’s progress for no good reason.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Adaptations: Why Ghost in the Shell Doesn’t Have One

Before I say anything else, the things I say about Ghost in the Shell here assume a little bit of knowledge about the franchise. While I would have loved to have gone in depth on some of the things I mention, I don’t see a way to do that right now without, essentially, spending several years doing so. I’ve wanted to write about this topic, in some form or other, for a long time, and this is finally something I’ve been able to put down without getting lost in a fog.

It’s taken me a long time to write about Ghost in the Shell. Mostly, it’s because I didn’t know where to begin or which specific angle to write from. We’re talking about a multimedia property that began as a manga series in 1991 that grew to see tons of subsequent material in the form of more manga, animated films, and video games that continue to be put out to this day. The video game aspect was what had always been on my mind, but the question that has been bothering me all this time really only became clear recently. Why isn’t there a great Ghost in the Shell game?

Okay, that’s a bit of a loaded question. There are, actually, a couple pretty good Ghost in the Shell games. One of those is for the Sony PlayStation, which takes the form of an action shooter where the player acts as the pilot (or is it driver) of a Fuchikoma. Aesthetically, it absolutely nails the feeling of its parent franchise. The second is also an action shooter for the PlayStation 2, which does let the player control the series’ protagonist, Major Motoko Kusanagi, as well as a handful of other members of her team. They aren’t spectacular games, but they do have some solid mechanics, and in the case of Stand Alone Complex for the PS2, there’s a wholly original story to delve into accompanied by some solid animation from Production I.G, the studio responsible for every animated adaptation of the series. The real issues I take with all the games is that they don’t truly capture the spirit of Ghost in the Shell.

This brings me to the point where I have to grapple with just how big a beast the franchise really is. My feeling about the lack of a great game representing the spirit of Masamune Shirow’s work is because when I think of Ghost in the Shell, I’m very specifically thinking about the 1995 animated film. It turns out that the1995 film is actually something of an outlier for the franchise. Written by Kazunori Itō and directed by Mamoru Oshii, the film is something of an amalgamation of a few different story lines taken from the manga source material. Despite something of a cobbled together story, the film managed to do something that the manga never really did: give the main character a convincing internal motivation before the story’s climax.

I recall Ghost in the Shell being sold as an action-packed, violent, “adult” story. The truth of the matter is the film is not really an action film at all. There are exactly three action set-pieces over the course of the hour and twenty-three minute run time. Those action sequences don’t really play out much like action sequences, either. They don’t feature bombastic or heroic music. Kusanagi is literally invisible or, at best, translucent while she fights. For the time she is visible in a combat situation, she hides herself behind the cover, waiting until a safe opening before donning her invisibility cloak again. We know so little about the adversaries in these scenarios that there’s no feeling of triumph upon the Major’s victories. It’s almost an anti-action movie. That seems to fly in the face of a lot of the other Ghost in the Shell material, if not most of it.

To me, this is why no existing Ghost in the Shell game is really great. Action games need to have action in them, legitimately. But by conforming to the standards of action titles, the core identity of Ghost in the Shell is completely lost. There’s just no room to explore the conflict that Kusanagi feels about being compelled to work for an organization that has given her the cybernetic body she enjoys and requires to live her life. There’s no clear-cut way to frame what violence takes place without taking control the player’s control away.

I might be in the minority in how I view the series, preferring the more “realistic” representation of the world and its inhabitants that the film took on. I am perplexed and intrigued by a Motoko Kusanagi that decides to merge with an AI as a result of her own existential crisis rather than being compelled to do so to avoid being prosecuted as a killer after being caught in the act.

Maybe most fans would be perfectly happy with something like a Metal Gear Solid game, just set in the Ghost in the Shell universe (hell, at this point I’d take that myself). Also, maybe most fans take no issue at all with an out and out action game. The Stand Alone Complex series seems to be the pinnacle for many fans out there, and it focused much more on the action, the technobabble that sounds more interesting than it really is, and of course, making Kusanagi look as sexually appealing as possible.

There are just so many of those kinds of games already, and almost none that explore the things that the 1995 film does because they aren’t the same kind of story. If a great Ghost in the Shell story is not, at its heart, an action story, then a great Ghost in the Shell game also couldn’t be an action game. Unfortunately, I don’t know what kind of game it would be. I’m not sure that there is such a thing as an anti-action game, but I do hope one day we find out.

0 notes

Text

Vampire Hunter D’s Lone Video Game Adaptation

When people talk about PlayStation era 3D games being hard to go back to, Vampire Hunter D is the one I most often think about. Something of an alternate timeline version of the Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust animated film, the game has you play as the vampire hunter, himself. Throughout the adventure, you explore the castle Chaythe to rescue a woman, Charlotte, from having been kidnapped by the vampire lord, Meier Link. I say it’s an alternate history because while the general plotting of the film (itself an adaptation of the third novel in Hideyuki Kikuchi’s series), the events of the game take place entirely within Chaythe, whereas only the last act of the film is set there.

The decision to condense the story to all take place within the castle is a brilliant move and makes for an interesting and thematically consistent setting. You work your way from room to room, finding items and solving puzzles to open up more of the castle to explore. All the while you must slay or evade enemies that stand in your path and battle the occasional boss. If any of this sounds familiar, it should. It’s the formula for the classic survival series, Resident Evil.

Vampire Hunter D does its best to disguise itself as a survival horror game. It has pretty much all the staples. There’s the spooky mansion setting, the keys and puzzles, the backtracking through areas to open previously inaccessible locations. There are pre-rendered backgrounds and static camera angles. Last and for many, definitely least, there are tank controls.

My feeling is that tank controls are perfectly fine for survival horror games where the player has no control over the camera. It makes sense that your directional movement would be absolute rather than depend upon the view of whatever area you happen to be in. The drawback, of course, is that precision movement is difficult and you often move a bit slower because it takes time for your character to turn to face whatever direction you want to go.

Vampire Hunter D is not a survival horror game. It’s an action adventure game. It’s an action adventure game with platforming, fast paced melee combat, and plenty of ways to keep yourself fighting fit in the form of consumable items. None of these things are made easier by way of tank controls and they are, by far, the biggest barrier to entry for players who might have otherwise really taken to the game. All it takes is getting stuck against a wall while being wailed on by an enemy or missing a jump due to a poor camera angle to sour the overall experience.

The game seems to be aware of just how inappropriate tank controls were as well, as other aspects of the game seem to exist purely to compensate for the movement. The platforming I mentioned earlier rarely has you leaping over dangerous gaps. Even the instances that do only set you back a few seconds or reset the current room with no penalty to your health points. Really, most of the time you just need to hop onto a box or a knee high ledge, which kind of makes you wonder why they bothered including it.

Tank controls really have their limitations in the combat. To compensate, by default, you lock onto the nearest enemy when you draw your sword. This alters your movement a bit as pressing left or right will have you circle around your target in that direction rather than having you turn your body to face that direction. This works fairly well in rooms that provide good visibility and aren’t too cramped, but can be pretty useless in tight hallways or if you're trying to work around more than one enemy at a time. Again, the developers at Victor Entertainment Software seem to have been aware of these limitations and generally limit the places where you face multiple enemies to specific sections of the game, many of which you can just run past if you need to. It’s no surprise that the bosses are all fought in more open rooms where you have ample room to run around, side step, and circle around while locked on.

It’s a shame that tank controls were what we were given. I understand why it was designed the way it was, but if any game could have been improved by having more standard 3D movement enabled, it would be this one. Perhaps most amusing is that there is analog support, but like Resident Evil, all it really does is map the tank controls to the analog stick rather than give you true freedom of movement we’ve become accustomed to over time. I have plenty of complaints about the movement in Devil May Cry, but something like that would have been a huge improvement over what ended up in the game.

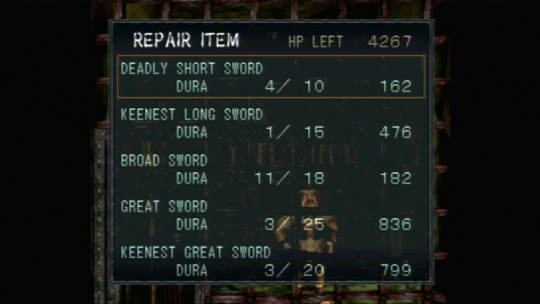

While the movement controls may be frustrating during combat, the mechanics around combat are actually where Vampire Hunter D shines the most and why I think it’s a game worth exploring despite its shortcomings. Being half vampire, D’s prowess depends upon having a steady supply of blood. That vampire power is represented by the VP bar under your HP.. Overtime, your VP depletes and causes your attack power to drop and your magical abilities to weaken. You can recover VP in two ways: consume blood capsules that you find throughout the castle or be splashed with the blood of enemies you strike with your sword.

I love this idea because it provides incentive to engage in combat when you would otherwise be tempted to just run past as many enemies as possible. If you avoid fighting, you have to consume blood capsules. While they aren’t exactly in short supply on the normal difficulty, they are best served for boss fights or other tough enemies so that you can recover some health and your VP and deal as much damage as possible.

It’s not as balanced as it really should be, unfortunately. Your VP drains at a pretty slow rate, but it’s also hard to get back up to a high level through the blood splashes alone. It would have been interesting to have the meter drain more quickly, but also refill more quickly, adding a bit of urgency to the game and really encouraging you to take down any monsters you come across.

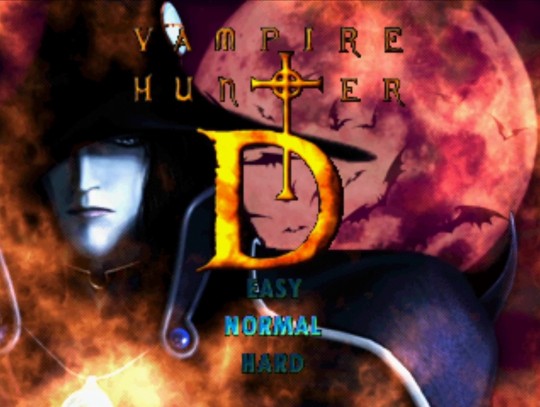

A similar mechanic is used for D’s magic abilities, which are made possible thanks to the parasite that lives within his left hand. There is an option to heal, an attack based magic that surrounds enemies and drains them of health, and the ability to absorb the souls of enemies. That soul absorption replenishes your magic meter, so while you want to refill your VP with sword strikes, you also want to make sure you inhale as many enemies into Left Hand as possible as well.

Again, this is a mechanic designed specifically to encourage killing the monsters in the castle and it’s a perfectly reasonable goal for an action game. Unfortunately, it has a bit of an opposite effect as absorbing enemies is not a guarantee and you’re likely to take damage when attempting it since you need to be in close proximity for it to work. If you try it and you can’t absorb one, you’ll almost certainly take a hit that would have otherwise been avoidable. It’s a shame the VP and magic replenishing systems weren’t all that complementary as the intent behind them really has a lot of merit and offers a glimpse at what could have been complex and satisfying combat mechanics.

If you know what you’re doing, Vampire Hunter D is a fairly short game with a fair bit of replay value, as there are three endings you can achieve depending on a handful of choices you can make. I find the story to be one of the more compelling things about the game. It’s told through standard in-engine cutscenes and they’re acted fairly well (several of the actors from Bloodlust reprise their roles). Your enjoyment of that probably largely depends on whether or not you’re already a fan of the Vampire Hunter D source material or your feelings on sci-fi action horror in general, but there’s a lot to like about it.

I feel a bit bad for those who just aren’t able to enjoy older games due to feeling archaic. I can’t really defend the issues Vampire Hunter D has, as there are legitimate limitations and design choices that make the game frustrating at times. However, I also don’t want it to be dismissed as an old game not worth playing. You can tell just how much the people who made it really seemed to care about making it true to the Vampire Hunter D series. It’s about as faithful a video game adaptation as could be and one well worth spending some time with.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why I Hope The Future of Castlevania (if There is One) Remembers Lords of Shadow

Some time ago I wrote about the two DLC chapters for Castlevania: Lords of Shadow and why you probably don’t want to play them. Those chapters are extremely disappointing and not representative of the game as a whole. As such, I always meant to write about the main game, but found it difficult to focus on something specific. Straight out reviews can be fun, but this is a big budget popular game we’re talking about. There are tons of reviews out there for it already. Instead, I want to talk about why the first installment of the series is still monumentally important to the franchise as a whole and why there are more lessons to learn from it for any future installments than there are to be learned from any other game in the series.

For any who don’t know, Lords of Shadow acts as a complete series reset. Several little elements from the original canon, if you can call it that, make their way into the game, though often in very different form. As I don’t get hung up about continuity or canon, this was an obvious good choice. It allowed MercurySteam and the folks at Konami to incorporate the things they liked about Castlevania without having the constraints of finding space within a pre-existing history. And like so many reboots, the story they chose was an origin story, both of the Belmonts and the series constant antagonist, Dracula.

Essentially, Lords of Shadow chronicles the birth of Dracula by way of the game protagonist, Gabriel Belmont. Unable to overcome the grief from the death of his wife, Marie, whom he killed while under the influence of belated antagonist, Zobek, Gabriel acquires incredible power and defeats Satan. Even after declaring to believe in forgiveness and receiving the forgiveness he so desperately seeks from his wife, Gabriel still descends into despair. We learn at the very end of the game that he’s forsaken humanity and become Dracula.

As the Lords of Shadow series broke away from the previous Castlevania timeline, so should a new 3D Castlevania game break away from the Lords of Shadow timeline. The poor reception to Lords of Shadow 2 killed that series and there is no point trying to bring it back. I’m certainly not eager to see a new origin story, but there’s no reason to think a new game would need to start at the beginning. Just as the original NES Castlevania started centuries after the first Belmont took up arms against the vampire lord, so too could a new title start at any point along a new timeline.

As large a departure from the source material as Lords of Shadow’s story was, the way it plays departed even further. Granted, none of the 3D entries truly capture the spirit of the 2D entries simply due to the nature of moving in 3D space. Castlevania and Legacy of Darkness for the Nintendo 64 adhered the closest, while Lament of Innocence and Curse of Darkness for the PlayStation 2 ventured more into brawler territory.

Lords of Shadow is heavy on the platforming, but rather than trying to time a perfect leap over a pit and Medusa head, you instead shimmy across ledges and use your whip to swing across gaps and repel down walls. It’s much more akin to how platforming works in a game like Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time or the rebooted Tomb Raider series. This allowed the game to showcase its art direction very specifically. Since the game controls the camera at all times, they could position you exactly how they wanted to give you pause at majestic waterfalls in the background, or exaggerate the sense of scale against towering bosses.

While I prefer camera control to rest with the player, there is something to be said for the framing that a game controlled camera allows for.

While I love the more ridiculous and difficult platforming of the Nintendo 64 games, there is a steep learning curve to it. On top of that, the hallmark problems of 3D platforming (issues with camera position and depth of field) have never really been solved. The negative impact of the symptoms may have been lessened over the years, but the core issues remain. That means you have essentially have to choose where to focus your game. Do you put your effort into making your platforming as excellent as challenging as rewarding as possible, or do you focus on the action elements?

Lords of Shadow focused largely on the action. The game is most satisfying when you have small groups of weaker enemies to tear through with your favorite combat techniques, or more difficult single enemies where you have to learn their patterns so you can time your dodges and blocks effectively. The only real complaint about the combat system is that many of the techniques that you can learn feel frivolous. Upgrading a handful of the basic ones is more than enough to get you through and it’s quite difficult to remember the numerous button combinations needed for each new technique you learn. It’s easy enough to use two or three that you know well and ignore everything else.

The more interesting aspect of combat are the various relic powers. These add holy or demonic magic properties to your techniques depending on which type of magic you have activated. I prefer these types of upgrades because they don’t require you to memorize a new set of commands for a marginal benefit. They simply amplify the effectiveness of certain techniques, and push you toward using certain ones. Having more of these that you could select from would have been a nice way to round out the combat without further complicating it. This is something I’d prefer to be lifted from the game rather than the basic combat elements. After all, there are other action games like Devil May Cry or Bayonetta that serve as better combat templates than Lords of Shadow.

The outstanding question you may be asking is “why make a 3D Castlevania game at all?”. It’s a fair question. The games from the series that have really stood the test of time are those in 2D. The legacy of the classic NES titles and the Igavania titles is well-respected and lives on through an abundance of games that took inspiration for a reason. Igarashi himself managed to put together a spiritual successor to both Symphony of the Night and Dracula’s Curse, cementing that legacy for a long time to come. There is no such legacy for the 3D entries.

As much as I adore the quirks and charm of the 3D entries in the series, I’d be lying to myself if I said any of them were truly outstanding. Lords of Shadow may have come close, but its shortcomings are too numerous and the legacy of the series as a whole tarnishes even the brightest elements. Castlevania deserves a truly outstanding 3D game. The opportunity for it is there, so long as whoever makes it learns the lessons of how and why games like Lords of Shadow fall just short.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Castlevania: Lords of Shadow DLC That Probably Shouldn’t Be

Despite owning the Castlevania: Lords of Shadow Collection, I never bothered to actually download and play the packed in DLC my first time around with the game. Since I wanted to talk about Lords of Shadow more generally, I figured my second playthrough would be as good an excuse as any to finally get through those last two chapters, Reverie and Resurrection. Before I get to that, however, I should say that Lords of Shadow is a game I enjoy immensely. It has a lot of problems that I can’t wait to delve deeper into, but I can’t help but have a great time while playing it. My second time through was even more enjoyable than the first. When you have a good grasp on the combat and know the solutions to puzzles ahead of time, the pace of the game feels more like it was intended. The cinematic approach the game strives so hard to achieve comes through quite effectively.

It’s safe to say, then, that I was really excited about the DLC chapters. Gabriel’s story arc over the course of the main game feels complete, but the reveal in the final cutscene that he’s become Dracula and he’s been hiding away in his castle until modern-day leaves ample room to explore what happened in between. Interestingly, MercurySteam initially had no plans to create DLC, according to the executive producer, Dave Cox. Rather, it was Konami, realizing they had a big hit on their hands, who wanted to capitalize on that popularity by throwing in some additional content. In hindsight, this really shows.

The biggest let down is in the character arcs, which is something the main game also struggled with. There is a huge disconnect between what the game tells the player they should be feeling through its use of heavy-handed journal entry reads and cutscenes, and what the player is doing moment to moment in the game. Gabriel is supposed to be losing his grip on his humanity thanks to his thirst for vengeance, but that struggle never shows up in what the player does. The abstract puzzle solving is enjoyable, but there’s no deeper meaning behind the gimmicks of the puzzles themselves. Meanwhile, the combat pits Gabriel against hordes of monsters that are inherently hostile. Whether Gabriel was actively seeking to fight them or not, there’s no question that Gabriel would be in danger if he ever happened across them. So all the time spent slaying those monsters can feel as much like self-preservation as it does Gabriel succumbing to his urges for violence.

To begin Reverie, Laura, the adopted vampire daughter of Carmilla, telepathically reaches out to Gabriel. She is desperate for his help and explains that an ancient evil, the Forgotten One, had been imprisoned by the founding members of the Brotherhood of Light. When they ascended, their Lords of Shadow counterparts maintained this prison. With the Lords of Shadow destroyed at Gabriel’s hand, the seal to the prison has grown weak and the Forgotten One’s escape is imminent. Gabriel, in his dejected state, refuses to help, at first, but a little cajoling from Laura convinces him.

Using a new, improved big bad as the reason for Gabriel and Laura’s paths to cross again feels contrived. Unfortunately there just isn’t any other way around that. However, the decision to use Laura in the DLC is a great choice. She resides in the castle that will eventually belong to Dracula, she has an established emotional connection to Gabriel, and her vampiric state is absolutely critical to the plot.

Reverie plays out much like any other chapter from the game, with Gabriel and Laura traversing the castle, fighting monsters, and solving puzzles to retrieve vials of blood from each of the Lords of Shadow, which act as keys to the Forgotten One’s prison. The added gimmick here is that the player takes control of Laura for some of these sections. Her vampiric powers of turning into mist allow her to pass through gated doorways that Gabriel can’t get through and replenish her health by consuming the blood of enemies. I commend the developers for trying to vary up the gameplay with the DLC, but being able to actually control Laura ends up detracting far more from the experience than it adds. Laura's ability to go through areas that Gabriel can't is only used a couple times, and instead of using that ability to navigate around and solve environmental puzzles, Laura just fights some zombies with some very poor combat mechanics.

Laura’s vampire abilities are terribly under-utilized.

This could have worked out a lot better with more appropriate level and puzzle designs, but I think it was a mistake to ever take the control away from Gabriel in the first place. The game is viewed through his lens, after all. He even narrates the prologues to the DLC chapters. I can't help but wish MercurySteam had taken some direct cues from ICO, where you could ask Laura to perform certain tasks or influence her behavior, but not control her directly. Of course, given the time and budget constraints MercurySteam was working under, it would have been an impossible task.

With all three containers of the blood of the Lords of Shadow retrieved, the seal to the Forgotten One's prison is opened. Unfortunately, Laura gives Gabriel the bad news that he won’t be able to enter the prison while he’s still alive as only dark beings can exist there. It's not explained why, but it serves to force Gabriel into making a decision. He can become undead by drinking Laura’s blood, or he can retain his humanity until the Forgotten One escapes and lays waste to the Earth. This decision is supposed to be made more difficult since Gabriel must consume all of Laura’s blood in order to turn, which will kill her.

This is where the lack of time given to this whole arc causes major issues with its emotional weight. Chapter XIII is about as long as every other chapter in the game, taking about an hour or so to complete. In that time we are expected to recall Gabriel's previous interactions with Laura, get to know her better, grow to like and empathize with her, and ultimately feel sorrow at having to end her undeath. The regret that Laura expresses only comes up in the cutscene where Gabriel is transformed. Before that, her dialogue portrays a confident and sarcastic character who seems in no hurry at all to die. Likewise, we are supposed to believe that it is in large part because Gabriel wants to end Laura’s suffering that he’s willing to forsake his own humanity. But you can’t have one without the other, so it just never feels convincing.

Despite being lightly animated paintings, I do quite like the cutscenes of the DLC.

If all that happens in Reverie, what happens in Resurrection, you might be asking. Gabriel chases the Forgotten One through a tedious, difficult to navigate lava obstacle course, then fights him to the death. In all honesty, Resurrection is a complete mess. It's the most intricate and challenging platforming the player is asked to do over the entire game, yet it takes place in the least visually distinctive level. There are tricky platforms to jump back and forth across, where missing results in instant death. There are timed elements where you have to wall-climb out of sight or face an instant death at the hands of the Forgotten One. And there's a collapsing staircase segment where you have to time jumps perfectly or it's back into the lava bath with you for another instant death. This whole segment really highlights how painful it is to not have any control over the camera whatsoever.

Other than a challenge of memorization and a bit of finger dexterity, nothing is accomplished at all with this chapter. We don't learn anything about the Forgotten One that we didn't already know in Chapter XIII, so I was absolutely shocked when he spoke before the boss fight. I figured it would act as some kind of primal beast, instinctual, and inherently non-human. Laura refers to him as a creature, after all. Nope, he's just a tough-talking baddie who wants to escape and destroy everything as revenge for being put in prison in the first place. For all his trouble of becoming a vampire, Gabriel doesn’t even get any new abilities. From the perspective of playing the game, there is no consequence whatsoever.

It seems like the Forgotten One forgot how not to talk in terrible clichés.

It's a real shame that MercurySteam chose to use one of its two DLC chapters on an obstacle course, especially when this whole ordeal is absolutely critical to Gabriel's character development. His decision to give in to darkness and become a vampire sets up the entire Castlevania franchise (or it was supposed to with the rebooted continuity), and ultimately, it just feels like a footnote. It’s, even more a shame that the publisher pressure and lack of execution on the DLC was a sign of things to come for the Lords of Shadow series.

0 notes

Text

The Dismemberment of Horror in Dead Space

After playing Dead Space for the first time I became increasingly frustrated by its attempts to be a horror game despite firmly planting its flag in the action camp. Action-horror is a tightrope walk between genres that I think rarely pans out, but that combination is alluring enough that I can’t fault anyone for trying. To me, action and horror are almost antithetical. Good action games provide a vehicle for players to feel powerful once they understand the mechanics and master them. Good horror games never let the player feel at ease, using the player’s expectations against them to keep them constantly unsettled.

Dead Space betrays its horror elements almost immediately. In two very important ways. First, the game’s monsters, the necromorphs, are revealed in all their gross glory before you even get two rooms deep into the mining ship you’re investigating, the Ishimura. You get onboard after crash landing in the opening cutscene, you walk into a room that’s got blood all over the floor, and then the necromorphs try to murder the entire crew you came with while you look on behind the complete safety of glass.

Dead Space takes so much inspiration from the 1979 film Alien as if the necromorphs weren’t a huge giveaway. But Alien works as a horror film because it spends the majority of its time building tension, first through the interpersonal issues of the crew, and then by having characters picked off one at a time by a monster the audience doesn’t really get to see. During that first encounter with the necromorphs you get a very clear look at them. You get an even better look when you’re chased into an elevator by one whose predatory instincts are questionable, at best.

Once you’ve seen the necromorphs, you know what you’re up against. This leads to the second way in which the game betrays horror, it tells you exactly how to deal with the necromorphs, and it does so in the absolute clumsiest way possible. Necromorphs need to have their appendages cut off in order to get them to cease reanimating and you get four opportunities in a row to learn this, two of which are impossible to skip. First, you find a message written in blood next to a body that says “Cut off their limbs”. Pretty straightforward. Minutes later, you can find an audio log where a crewmember says the same thing. Technically, both the bloody message and audio log can be skipped over or missed, but their placement makes that unlikely, at least on a first playthrough. What’s not skippable is the captain chiming in over your communication device saying the same thing as the audio log, followed by instructions from your suit that appear on the screen.

That’s four instances of the player receiving the same information all within the span of a couple minutes. I understand that severing necromorph limbs is the crux of the game’s entire combat, but when you tell the player the solution to fighting every single enemy in a game that’s supposed to scare them, you are doing them a terrible disservice. What makes this especially painful is that the player is given a subtle hint about cutting limbs off with the first necromorph that the player sees. As Isaac stands in the elevator while he’s being attacked, the elevator doors close and chop off the necromorph’s arm and head.

I am empathetic to developers not wanting players to get thrown into combat situations and repeatedly die because they don’t know what they should be doing, but this a game whose combat is modeled almost entirely on Resident Evil 4. In Resident Evil 4 you can shoot zombies in the legs to slow them down, you can shoot off their heads for quick kills, and you can even shoot thrown projectiles out of the air. None of this is told to the player, but it doesn’t take much experimentation to start figuring it out, which is arguably the most enjoyable part of the game. Dead Space never lets the player work out strategies for themselves, which can reduce the enjoyment and prevent the sensation of panic that horror games can elicit so well.

For all the things that Dead Space did well with regard to immersion, a few choices really break the illusion for me. There are a lot of small, but obvious issues. Necromorphs drop ammo and health items despite being horrifically twisted re-animated flesh with no need for either of these things. The ship is littered with caches of those same items, either built into the Ishimura’s structure or littered about the floor. There are also shops that allow you to buy health and ammo, as well as upgrade your protective suit.

All of these little problems add up to one big problem. All of the tools you end up using in the game only work in the context of a shooter. Sure, they try to justify the various weapons you can carry by giving them a tenuous relationship to mining, but even that is shaky. You first pick up the plasma cutter, presumably the most advanced type of mining tool in existence. So what purpose, then, does a circular saw serve? The answer is that the various tools flesh out the combat mechanics because they’re weapons, and nothing more. It would have been nice if the various tools could have been used to solve environmental puzzles and really explore the idea that Isaac is an engineer and not a soldier. Sadly, there’s nothing that Isaac ever does over the course of the game that doesn’t seem like something any other character couldn’t have done. The very existence of the item shops and upgrade stations pretty much proves it.

That brings me to the characters. This is where Dead Space felt the weakest to me. Every single character is a very broadly drawn archetype. You have a no-nonsense soldier, a nagging second-guesser, a mad scientist, a religious fanatic (well, several of them, actually), and the secret agent. To top it all off, you have the silent protagonist. Non-speaking player characters make a lot of sense in a lot of games, but it just doesn’t work out as well in Dead Space because your character has a personal reason for being on this particular mission: your girlfriend is on the Ishimura.

The first thing you see in the game is a video clip of Isaac’s beloved, Nicole Brennan. Kendra asks him about it, and the motivation is set. Isaac’s goal is to save Nicole. During the course of the game you do eventually run into her, and yet despite the horror show that both she and Isaac have gone through, Isaac does absolutely nothing even remotely resembling how one would react upon reuniting with a loved one. At the end of the game, we are treated to yet another obvious trope: Nicole’s been dead the whole time. I’m not sure if this was intended to actually be a plot twist or not, because it’s heavily foreshadowed. The video clip at the beginning clearly cuts off before it’s finished, and Isaac is arbitrarily kept from being close to her due to door locks that couldn’t possibly be activated if it wasn’t all occurring in his mind. When you finally are in the same room with her, Isaac has no reaction whatsoever. He’s supposed to be in love, but there is nothing even close to resembling human emotion coming from him.

One interesting explanation could have been that the trauma of the events has left him emotionally comatose, but instead, it’s all hand-waved away by the Marker. The Marker is a weird space object that is responsible for the necromorphs and drives anyone who spends enough time around it insane. Isaac is supposed to be a victim of this, and Kendra straight up tells us this after she reveals herself to the double-crosser that she is. It’s here that we get to see the video of Nicole played back in its entirety, and watch as she takes her own life to spare herself the horror of the situation.

The root of every element of the game can be clearly seen. You get your doses of Resident Evil 4, Alien, System Shock, and Event Horizon. Obviously, there are few or no true new ideas when it comes to stories, but what you want is a game that works to defy expectations a bit, and that allows the interactive elements to tell the story in ways other media can't. Dead Space doesn’t do this, it simply adds everything it can into one pot and hopes for the best.

For all its lack of a true sense of horror, Dead Space is still an immensely enjoyable action game, which is, itself, a huge accomplishment. You can try it for the first time a decade after its release like I did, and it plays just as well now as I’m sure it did then.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Adaptation Expectations - Sword of the Berserk: Guts' Rage

Some things just demand to be adapted into video games, and Kentaro Miura’s dark fantasy manga series Berserk stands pretty much atop that list. Released in 1999 and developed by Yuke’s in cooperation with Miura, Sword of the Berserk: Guts’ Rage is a third-person action game for the Sega Dreamcast that attempted to scratch that initial gamification itch, and ride the success following the first anime adaptation of the series, which premiered two years prior.

Before discussing the details, it’s important to note that Sword of the Berserk suffers the same fate that so many licensed games do. It isn’t very good. Some of that comes down to the era in which it was made. There are a few frustrations that plague it that are typical of an era in which 3D action games were relatively new. That isn’t to say there aren’t things to enjoy about the game. If nothing else, it did help solidify why the approach to how action games played needed to be adjusted. Unfortunately, that means Sword of the Berserk itself, is something of a missed opportunity. On the plus side, it’s not a very long game, so its shortcomings don’t have enough time to grossly overstay their welcome, and any suffering along the way is mercifully brief.

The first obvious issue is the lack of camera control. Going back to play any 3rd person action game without a controllable camera can feel extremely limiting. It’s become such a staple that it feels more unnatural not to have it than it probably did to have it when it was first introduced. Of course, there are certainly examples of very good games that lack it. You can’t control the camera in Onimusha or Devil May Cry, but you don’t tend to notice that limitation as much since the camera is placed in thought ways that reveal the relevant visual information to the player.

Sword of the Berserk’s camera lacks that thoughtfulness. It tries to be dynamic, moving along with your character, but the concern seems to be more on framing Guts in a particular way rather than assisting the player. Given that this is an adaptation of a beautifully drawn manga series, it’s hard to fault the developers for trying to capture some of that magic in their game (which they largely accomplish in the cutscenes), however, it ends up compromising its playability to a fairly extreme degree at times.

You also have the issue of moving toward the camera a lot, meaning you’ll often find yourself running headfirst into danger you can’t see until it’s too late. There’s even an escape sequence near the end of the game reminiscent of Sonic Adventure 2’s opening sequence. You have to run around and jump over obstacles with little warning before you’re right up against them. Without rings to help you cling to life, this is extremely frustrating. One mistake means you die, and in a game with limited checkpoints and continues, it can quickly become the hardest and most frustrating part of the entire experience.

Rollin' around at the speed of sound/Got places to go, gotta follow my rainbow/Can't stick around, have to keep movin' on/Guess what lies ahead, only one way to find out!

Another part of what makes the camera so difficult is that it doesn’t have a lot of room to maneuver, even if the developers might have wanted to. You spend most of your time inside a castle, fighting through narrow corridors and cramped courtyards. In those confined spaces, the camera can’t really move wherever it wants because chances are, level geometry would get in the way. There are few examples of where this does actually happen, such as when you travel below the castle’s cemetery, and an obelisk sitting in the middle of the room complete obscures any figures that move behind it.

Aside from restricting the camera, the level design has the consequence of hampering what the game’s mechanics are centered around entirely, the combat. The whole point of a Berserk game is to play as Guts and swing the laughably huge Dragon Slayer sword around. There are several levels in this game where that is literally impossible. One level in particular, where you run through the castle town has several passageways where you’ll clank your sword against stone trying to land a hit on guards that hinder your progress. The developers seemed to realize this would be a problem, so they put in the option to sheath the Dragon Slayer and fight with your fists. I can say that this is not the most adequate solution. Even playing on the easy difficulty, punching guards out is a dubious proposition. Your damage output is drastically reduced and since the guards can snipe you with arrows from some distance with crossbows, you may well die before even getting the chance.

Let me just, uh, erm, hmm.

On some level, you have to respect the commitment to realism, as you obviously could not swing a sword the size of the Dragon Slayer in most places that human being typically occupy. However, the ability to swing said hunk of iron in the first place is fantastical, and thus, I think it would have been more than a fair compromise to let the sword simply clip through level geometry in an effort to make the combat more fluid and satisfying. Thankfully, the boss fights, which are the main draw of the game’s combat, are usually placed in much more open areas to avoid this issue.

Ultimately, I get the feeling that the game’s design took something of a back seat to the story that Kentaro Miura wanted to tell, and as such, there’s relatively little actual game to be played at all. Of the roughly four hours it takes to get through, most of that time is spent in cutscenes, making Sword of the Berserk more of an animated film than a game. Honestly, this does not really bother me. If you got the game because you were already a fan of Berserk, then what you’re getting is Berserk. What’s especially great about it is that the story told is unique to the game. It’s a side-quest, as it were, to the Millennium Falcon arc, where Guts has decided to keep the traumatized Casca close to him as he continues his quest to defeat Griffith. In this side story, Guts meets some traveling performers and decides to go watch their performance in a nearby town. He ends up walking into the middle of a conflict between the regions lord and people afflicted with a curse, called the Mandragora.

What’s more, is that the story is told quite well. For its time, the Dreamcast was a very capable platform for 3D graphics. Even twenty years later, the cutscenes are enjoyable to watch on their own if you’re willing to overlook a few flaws. Sure, the characters models are a bit blocky and they move a bit like action figures, but robotic movement is a problem that still plagues 3D animation if the 2016 Berserk or 2019 Ultraman anime is anything to go by. There’s still incredible attention to detail. The faces, in particular, have a lot of expression to them and help bring moments to life in a way that seems hard to believe at times.

You can really see the despair on his face.

It helps, too, that the voice acting is of very high quality. With well-known talents like Cam Clarke and Earl Boen, there was a clear emphasis on treating the game’s story seriously. This is extremely important since the story makes up pretty much the whole reason you’d be playing this game in the first place. There are some issues with the localization here and there (the name Guts is treated as a nickname rather than a given name in a few scenes), but the line delivery and interaction between characters really sell the scenes, even if the lines themselves are a bit clunky or cliched. When you compare the cutscenes in Sword of the Berserk to those in say, Tenchu: Stealth Assassins, released just a year earlier, you can’t help but appreciate the skill in direction and experience of the actors when stellar voice-acting in games was not a given.

You could argue that this story could have been served better through manga or traditional animation, but it’s hard to fault Yuke’s for wanting to make a Berserk game, or Miura for wanting to branch out and test the waters on new methods of conveying his story. Berserk’s popularity in Japan meant that a game based on the series was going to be made at some point, and creating a self-contained side story that can be begun and ended within that game makes perfect sense. It also helps make the game approachable by those who aren’t familiar with the series at all. In 1999, Berserk certainly wasn’t considered such a pinnacle of dark fantasy in the West as it is today, so someone picking the game off the shelf in the US would very likely have no frame of reference for the story at all. Thanks to the introduction of new characters like Rita, the player can learn what they need to know through the lens of those characters, making the reliance on that prior knowledge a lot less necessary.

Now that Berserk’s influence has become so far reaching, it seems unlikely that anyone would come to the Dreamcast game without some working knowledge of the series. While it’s hard to consider it a can’t miss part of the Berserk experience (save for the wonderful musical contributions of Susumu Hirasawa), there’s enough there for anyone willing to put up with some clunky design. At the very least, it’s worth watching a playthrough online for the story alone if the act of playing the game itself doesn’t manage to replicate the feeling of becoming the Black Swordsman himself.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wrong Place, Wrong Time: Fatal Frame’s Maiden of Black Water

When the Wii U was announced and I saw early footage of the gamepad, which includes its own touchscreen designed for asymmetrical gaming, the very first thing I thought of was how perfect it would be for Fatal Frame. Tecmo’s partnering with Nintendo beginning back with Tsukihami no Kamen for the Wii was a clear statement that bridging the gap between player and game by way of hardware peripherals was the future for the series. Tecmo mostly delivered on that goal when it came to the Wii. While not a perfect game, Tsukihami no Kamen is one of the best entries in the series. It used a more unique setting, incorporated motion controls in relatively intuitive and meaningful ways, and even managed to enhance the audio presentation thanks to Nintendo’s quirky hardware designs. While it remains the most obscure title outside of Japan thanks to its lack of localization for other markets, it was both a great experiment and a great game.

With the Wii U gamepad, Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water could go one step further and put the Camera Obscura directly in the player’s hands. Series director, Makoto Shibata, indicated that he worked very closely with Nintendo regarding building the game around the Wii U’s unique capabilities. For the most part, the gamepad integration is exactly what you’d expect. When taking pictures, the player aims the gamepad in the direction of what they want to capture, using the screen as the viewfinder. The ZR button behaves like the typical shutter button present in the PS2 games. Physically moving the gamepad to navigate the world while the Camera Obscura allows for 360-degree tracking, which reduces the virtual layers between player and game while adding a physical layer that previous entries simply had no way to include.

With new possibilities come new challenges. Players have to balance looking at the gamepad and looking back up at the TV screen in order to get a good sense of where they are in relation to everything else. It is here, looking back and forth between two screens, that Maiden of Black Water builds the majority of its suspense. The confining nature of the viewfinder mode in the Fatal Frame series was always designed to make moments more dreadful. Going from the relative safety of the third person view to the first person perspective of the Camera Obscura, means you have to drastically reduce your visibility in order to accomplish goals within the games. When ghosts routinely try to ambush you from behind, being able to only look directly in front of you radically reduces your ability to defend yourself. In Maiden of Black Water, the risk that players must partake in to progress is taken to the extreme.

On one hand, being able to quickly peek at your television without having to change perspectives in the game’s UI makes for a better time. If you think you might be backing yourself into a corner, you can quickly focus on your TV to get a better view of your surroundings and make quick and informed adjustments. In the earlier series entries, you’d have to put the camera away, figure out what angle you were looking at the room from, then adjust from there. It worked beautifully for a horror game, but it was slow and imprecise at times. The Wii U’s gamepad reduces the time spent switching back and forth between viewing methods and gives a great deal more control over the camera itself.

On the other hand, having to focus on two different screens in real life can be just as, if not more disorienting than doing it virtually. I found my eyes often failing to adjust quickly when darting back and forth, and moving the camera around with my hands instead of just with the analog stick meant losing track of what I was looking at due to the natural blurring effects that happen when moving your head quickly. These issues became less pronounced with practice (and heavy use of the lock on mechanic), but they aren’t something that every player is going to be able to contend with. Thankfully, there’s an alternative option for those who aren’t able to or simply don’t want to use the gamepad in this way, which puts the camera’s viewfinder up on your TV screen instead, like the rest of the series.

Given how much experience so many of us have with cameras (or at least smartphones with cameras built into them), one would think very little training would be needed to make sure players have the skills they need to navigate this game successfully. Tecmo must not have had faith in its audience because the introduction to the game is a plodding mess of a tutorial section. In Tecmo’s defense, using the gamepad is not much like using a real-world camera at all. The reason for that, and where Tecmo deserves 100% of the blame, is because of how they decided to change things up for the combat. The ideas behind it are mostly the same as those codified by earlier entries in the series. Taking pictures of ghosts while they are close to increases the damage your shots do. The time spent focused on an enemy builds up the spirit power of your camera, and waiting until a fatal frame opportunity before taking the shot will deal out the biggest hits and return the most points. Those things all work more or less as expected.

The big addition to the suite of combat mechanics, requiring multiple hovering targets to be captured in a single photo with the main spirit, is not an easy enough concept to leave up to players to figure out on their own. In Koei Tecmo’s effort to explain it in-game, since they couldn’t be bothered to create a manual, is to render the first enemies in the game almost completely harmless. The first enemies in these games have never been particularly threatening, but just how dangerous they are isn’t something the player is aware of unless they make a mistake. Even then, enough mistakes could kill the player outright and the encounter takes place at the same pace as every other encounter in the game.

In Maiden of Black Water, the first ghost you fight stands still for the majority of the experience as on-screen prompts walk you step by step through each facet of using the camera for combat. Only once does the ghost try to lunge for you, which is prefaced by text telling you it’s going to happen. The vast majority of ghost encounters are scripted, of course, but the lack of facade here betrays the uncertainty that is vital to establishing a horror atmosphere. There’s just no way to be afraid of an enemy’s attack if the game tells you it’s coming well beforehand and doesn’t bother to even make it punishing if you fail it. It’s not a bone-chilling start, despite how hard the cutscene directors try to make it seem otherwise.

Fatal Frame has always included plenty of in-game information on how its systems work and how to maximize damage in combat, but its tutorializing was never so exposed. In previous entries, some text pops up on screen as new mechanics are introduced. The player can either read it or hammer a button to skip right on through. After that, these documents are tucked away for later reference if needed and the player is left on their own to make good on whatever knowledge they’ve acquired. It would be a stretch to say Tecmo ever managed to pull off tutorialization with any real elegance, but the quick and dirty approach of simply putting pieces of the manual into the game worked well enough. They even have just enough of a narrative reason to exist, since they are often presented as notes left NPCs. It’s not a seamless integration, but it’s enough to keep the game’s facade acceptable, if not totally believable.

Having played the entire series again, one lesson learned is that complicating a horror game’s systems does not make it more frightening. The original Fatal Frame is maybe the scariest of the bunch, badly delivered dialogue and all. It pulled this off despite offering the lowest level of technical expertise because it focused on the world’s presentation over the method with which you dispatched spirits. While Fatal Frame is also arguably one of the easier games in the series, that lack of difficulty doesn’t come at the expense of its dreadful tone or the carefully crafted sequences that make it so haunting.

As the series progressed, it became more and more about making the combat interesting, adding features, drawing more and more attention to evaluating player performance, and letting the environmental storytelling take a back seat. Maiden of Black Water has the most involved combat system out of any of the games, and with the gamepad at the center of it all, the game’s world had to be built more around the limitations of players using it rather than the capabilities that such a device allowed for.

Those human limitations of understanding and reacting to the overcomplicated combat resulted in the game being compromised in ways that previous installments weren’t. The Wii U is the most powerful system that a Fatal Frame game has appeared on, yet its art direction just doesn’t convey an otherworldliness that makes ghosts unsettling. The lack of light in the early games, resulting in lots of negative space on the screen, is nonexistent in Maiden of Black Water. The warping effects around the spirits have almost been preserved, but they also give off a glow that makes them look like a soft, dim light bulb more so than a soul stretching across two planes of existence. They are weirdly opaque and easy to spot, which may have been a result of technical limitations on the count of the Wii U, but could also be a result of needing them to be more easily identifiable for the player’s benefit.

Ghosts often appear in groups of three or four, which means they need to have a minimum amount of space to move around and for the player to move around and between them. Because of the multi-target damage multiplying mechanic, players need even greater distance between themselves and their enemies in order to get clear shots of all of the targets at once. It’s surprisingly rare to be in a cramped location. The introductory sections are easily the most dangerous architecturally, even though there are no real threats there. In earlier games, it would be common to be ambushed by a ghost in a narrow corridor. Since it was impossible to keep a lock on a ghost that spent most of its time behind walls, this would force players to run to a larger connecting room where they could maintain eye contact with the spirit to build their spirit charge and deal decent damage.

So much of Maiden of Black Water takes place outdoors in a forest that has pretty good visibility. There are paths that limit your movement a little bit, but there is little in the way of obstructed views, so even if you can’t move around all that much, you can see far enough and the ghosts are distinguishable enough that you can still have a pretty fair fight no matter where you are. It’s only when fighting a big group at once or particular ghosts that can deal ongoing damage to you that things get really hard to manage. It’s always cumbersome no matter the difficulty, and the time it takes to learn the ins and outs of the mechanics, the various input sensitivity, and ghost AI tendencies leaves little time to realize that these are supposed to be harrowing situations.

There’s not a single location in any other Fatal Frame game as open as this.

This all makes for a challenging game, but not a scary one. Over time, I’ve definitely become desensitized to the tricks that Tecmo uses to elicit fear in players. I recognize the AI, I recognize the tells in the level design, and I understand the pacing well enough to predict when certain things are going to happen. Even knowing what I know about these games, I can still go back to most of them and get chills when a figure appears behind me in a mirror or when a ball suddenly starts bouncing towards me down the stairs. Maiden of Black Water actually has a few moments that used this knowledge against me. There are so many dolls strewn about the various locations that I was certain they would turn into a jump scare or become an enemy for me to take down on my way to complete some task. This doesn’t really happen, and that restraint shows that, on some level, this team still knows how to keep players on edge. It’s just a shame it that more often than not, the subtle horror that wore down a player’s defenses was traded for a more action-oriented style of play.

Had that same level of restraint been applied to more facets of the game, I think Maiden of Black Water could have been a classic horror game. It could have given all the people who scoffed at the Wii U gamepad’s gimmicks something to chew on. It could have shown why horror is the perfect genre for tech such as augmented reality and VR. Fewer, but denser locations, fewer but more meaningful ghost encounters, and a back to basics kind of combat would have allowed the truly innovative parts of the game to really shine. Turning the gamepad on its side to put the camera into portrait mode is brilliant. Being able to turn around in a complete circle and have the gamepad screen track correctly is inspired. These genuinely unique features are just buried under a bunch of superficial additions, getting in the way. With all those extra layers built on top of the foundation, there’s just no way for the horror to make its way to the surface.

The superficiality present in the series really comes to head for the sixth installment. Where we saw increasing sexualization of characters as the series progressed, Maiden of Black Water does just about everything it can to elicit arousal as much as fear. This is nothing new for the horror genre, but it is a sharp turn away from the more subtle elements of horror and toward blatant titillation. The female main characters are attractive young women who wear incredibly impractical clothing for the type of locations they explore (a short dress and short shorts aren’t exactly appropriate gear for traversing a rain-soaked mountain).

That same rain ties into a new mechanic where getting wet increases the amount of damage the player can deal while increasing the amount of damage they’ll suffer if hit. The longer the player is exposed to rain or wades through standing water, the wetter they get, and the more pronounced the water’s effects are. As the player gets waterlogged, their clothing also reacts, getting darker in color, and clinging to the characters. This would provide wonderfully non-intrusive visual feedback invaluable for players were it not for the meter that appears on screen which gives the player the exact same information.