#Javad Zarif

Text

Joe Biden campaigned in 2020 on the promise of new ideas, more competence, and a “return to normality.” But when it comes to economic sanctions, President Biden has chosen instead to maintain the path that his predecessor set. From Venezuela to Cuba to Iran, the Biden administration’s approach to sanctions has remained remarkably similar to Trump’s.

On the campaign trail, candidate Biden promised to rejoin the Iran deal and to “promptly reverse the failed Trump policies that have inflicted harm on the Cuban people and done nothing to advance democracy and human rights.” Yet two and a half years after taking office, the Biden administration has made little progress towards fulfilling these promises. While economic sanctions may not seem important to the average American, they have strong implications for the global economy and America’s national interests.

President Biden initially showed promise by requesting that the Treasury Department conduct a swift review of U.S. sanctions policies. However, the review’s publication in October 2021 was underwhelming. It produced recommendations such as adopting “a structured policy framework that links sanctions to a clear policy objective,” and “ensuring sanctions are easily understood, enforceable, and, where possible, reversible.” If the U.S. was not already undertaking these measures, it is fair to ask what exactly was taken into consideration when prior sanctions were implemented.

The failure to reenter the Iran deal is the most egregious error of Biden’s sanctions policies. Apart from harming American credibility and acting as a strong deterrent to any future countries looking to enter diplomatic agreements with the U.S., Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy has been a complete failure. As the United States Institute of Peace notes, Iran’s “breakout time” —the time required to enrich uranium for a nuclear bomb — stood at around 12 months in 2016. As of today, Iran’s breakout time stands at less than a week.

It did not have to be this way. Although Iran violated segments of the JCPOA after American withdrawal, it never left the deal completely, signaling potential for a reconciliation. Yet the Biden administration declined to lift sanctions initially. As Javad Zarif, Iran’s foreign minister, told CNN in early 2021, “It was the United States that left the deal. It was the United States that violated the deal.”[...]

Biden has shown similar hesitancy on Cuba. Although the administration has taken certain steps to undo Trump’s hardline stance, there remains much room for progress. Six decades of maximum pressure on Cuba have failed completely, serving primarily to harm Cuban civilians and exacerbate tensions with allies who wish to do business with Cuba. The U.S. embargo of Cuba is incredibly unpopular worldwide. A U.N. General Assembly Resolution in support of ending the embargo received 185 votes in support, with only two against — the U.S. and Israel.

Steps such as reopening the American embassy in Havana and removing restrictions on remittances are positive developments, yet the Biden administration could do much more. Primary among these are removing Cuba from the State Sponsors of Terrorism list and ending the embargo once and for all. This would not only improve daily life for Cuban civilians, but increase business opportunities for Cubans and Americans alike.

Trump also attempted his maximum pressure strategy with Venezuela, but failed to achieve anything resembling progress. In one of his final actions in office, he levied even more sanctions on Venezuela, further isolating one of the region’s largest oil producers. Venezuela is another country where the Biden administration has taken mere half-measures. Easing some sanctions in late 2022 is a positive sign, but there is no serious justification for keeping any of the Trump-era sanctions in place.

All of these actions have had major consequences, not only for the citizens of the sanctioned countries, but also for Americans. As oil prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the fact that Iran and Venezuela, two of the world’s largest oil producers, were unable to sell on the U.S. market no doubt led to higher gas prices for American consumers. And the millions of Americans with family in sanctioned countries face serious difficulties in visiting and sending remittances to their family members.

Despite these measures, none of these countries are considered serious threats to the U.S. In a March 2023 Quinnipiac poll, Americans rightly ignored Iran, Venezuela and Cuba when asked which country “poses the biggest threat to the United States.” Just two percent chose Iran as the biggest threat, with zero choosing Cuba or Venezuela.

These sanctions are unpopular, ineffective and quite often counterproductive to American interests. While changing the course of U.S. foreign policy can take quite some time, the dangers of hesitancy are quite clear. Rather than maintaining the Trump status quo on sanctions, which saw record increases, President Biden should fulfill his campaign promises and end the ineffective and costly sanctions on countries such as Iran, Cuba, and Venezuela, and return to the use of diplomacy to further American national interests.

You know things are bad when The Hill is coming after you as a democrat (note the lack of mention about sanctions on China or DPRK)

22 Jun 23

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since its start, the war in Gaza has been thought of as potentially foreshadowing a direct conflict between Iran and Israel. Hezbollah continues to threaten to open a new front in the war, and Iranian hard-liners have welcomed their country’s direct intervention. Last month, Iran’s former foreign minister, Javad Zarif, mentioned a letter written by hard-line officials to Iran’s supreme leader attempting to persuade him to engage in the conflict with Israel on behalf of Hamas.

The likelihood of an expanded regional war, however, is low. Despite the slogans echoed by Iranian hard-liners, the reality of Iran’s strategic thinking is more circumspect. There are at least seven reasons Tehran is likely to avoid starting a war with Israel on behalf of Hamas.

First, the Islamic Republic of Iran cannot rally society to engage in a new war as it did during the war with Iraq in the 1980s. It was the relentless mobilization of human waves, among other factors, that resisted the Iraqi army and forced Baghdad to withdraw from Iran’s territory. However, several decades later, society’s support for the political system has significantly declined. Following last year’s protests, coupled with the economic crisis caused, in part, by U.S.-led sanctions, discontent among the youth and the urban middle class has surged.

Second, the moderate faction in the Iranian government has been warning against Iran’s direct intervention in the war. Indeed, the war in Gaza has deepened political cleavages in Tehran. In the threat assessment of Iranian hard-liners, the destruction of Hamas is automatically associated with the subsequent collapse of Hezbollah and, ultimately, a military attack on Iran. That is why they support targeting American bases in Iraq and Syria by Iran’s Shiite proxies. This view stands in stark contrast with that of moderate officials, particularly Zarif, who has consistently warned about the destructive consequence of Iran’s potential involvement in a war with the U.S. According to Zarif, if Iran takes a more radical stance on Gaza, it could trigger a deadly conflict with the U.S., which Israel would welcome. And despite being marginalized by Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s government, Zarif still holds significant influence among the political elites of the Islamic Republic and even its society.

Third, Israel’s apparent failure in deterring Hamas’s attack on Oct. 7 does not alter Tehran’s strategic calculation toward Israel. Despite Israel’s reliance on high-tech defense technology like the Iron Dome missile defense system, Hamas inflicted a significant military and intelligence blow against it, thereby shattering its deterrence policy. But that does not shift Iran’s perspective on Israel or the power dynamics in the region. Though the Hamas operation rattled Israel’s long-standing credible deterrence strategy, it does not provide Iran with the opportunity to challenge Israel using missile power. Conversely, Iran may believe that Israel feels that reestablishing deterrence is an existential priority for which it’s worth taking extraordinary military or political risks.

Fourth, contrary to the conventional wisdom, neither Hamas nor even Hezbollah is Iran’s proxy; it would be more accurate to think of them as Iran’s nonstate allies. There is no top-down relationship between Tehran and Hamas. Even as Hamas aligns its actions with Iran, its approaches could diverge, as they notably did during the Syrian civil war when Hamas supported the Sunni anti-Assad rebels. American and Israeli intelligence has suggested that Iran’s top officials were not aware of the Hamas operation. In mid-November, Reuters claimed that Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, told Ismail Haniyeh, the head of Hamas, that because the Iranian government was given no warning of the attack on Israel, it will not enter the war on the Palestinian group’s behalf.

Fifth, Iran’s strategic partners in Moscow and Beijing have not declared their full support for Hamas. Iran has sought alignment with China and Russia under its Look East policy and would be loath to spoil its relationships with those countries. Tehran is, in fact, following a similar policy in Gaza to the one it adopted after observing the Sino-Russian wait-and-see approach to the capture of Kabul by the Taliban two years ago. The goal for Iran is to avoid being isolated in major international crises.

Sixth, there exists a deep belief among influential decision-makers in Iran that the Arab sheikhdoms of the Persian Gulf would welcome a large-scale war between Iran and Israel. Iran may hope that Arab countries would sever their ties with Israel as a result of a wider war, but that is unlikely. Arab public opinion holds little sway over their countries’ foreign policies. And Arab leaders have long perceived Hamas as a disruptive Iranian proxy that they would be happy to see Israel dismantle once for all.

The last and the most significant factor influencing Iran’s apparent reluctance to engage in war is Khamenei’s specific point of view toward regional conflicts. Contrary to the mainstream view in the West, Iran’s supreme leader approaches responses to regional conflicts from a realist standpoint rather than an ideological one. Having served as the president of the Islamic Republic during the devastating war with Iraq, he is acutely aware of the consequences of war, especially with the U.S. This awareness led Iran to choose a relatively measured response following the assassination by the United States of Gen. Qassem Suleimani, the former leader of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force. Such behavior aligns with his overall strategy in handling regional crises. More than two decades earlier, when Iranian diplomats in northern Afghanistan were killed by the first Taliban emirate and public sentiment in Iran leaned heavily toward a major intervention, Khamenei and Hassan Rouhani, head of the Supreme National Security Council at the time, helped prevent escalation.

These seven interconnected reasons explain the Islamic Republic’s reluctance to involve itself in the war on behalf of Hamas. The war in Gaza may, however, accelerate Iran’s nuclear program. There are strong voices in Iran, predominantly in the hard-liner camp, arguing that the country’s most significant tool to prevent the destruction of Hamas hinges on its decision to fully pursue nuclear capabilities. They believe that Iran’s trump card lies in its threat to develop nuclear weapons, showcasing vital support for its allies—similar to its past support for the Assad government of Syria. This reasoning gained substantial momentum when Israeli ultranationalist Heritage Minister Amichai Eliyahu advocated for the dropping of “some kind of atomic bomb” on the Gaza Strip “to kill everyone” as “an option.”

None of this implies that Iran is willing to abandon Hamas, its strategic asset in Gaza. Rather than standing idly by, Tehran is likely to continue applying pressure on both Israel and the U.S.—through Hezbollah and its Shiite proxies in Iraq and Syria—without escalating the conflict to a full-scale regional war.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

[...] Voria Ghafouri, a former member of the national football team and once a captain of the Tehran club Esteghlal, has been outspoken in his defence of Iranian Kurds, telling the government on social media to stop killing Kurdish people. He has previously been detained for criticising the former Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif. [...]

The footballer, 35, was a member of Iran’s 2018 World Cup squad, but was surprisingly not named in the final lineup for this year’s World Cup in Qatar.

Originally from the Kurdish-populated city of Sanandaj in western Iran, Ghafouri had posted a photo on Instagram of himself in traditional Kurdish dress in the mountains of Kurdistan, but is a cult hero beyond Iran’s north-west. Sanandaj endured some of the most violent crackdowns in the protests that followed the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian Kurd, and Ghafouri had visited some of those injured in the protests in Mahabad.

In 2019, he distributed blue jerseys in honour of Sahar Khodayari, a woman who self-immolated after being sentenced to prison for attempting to watch an Esteghlal match at Azadi stadium. After another incident of violence against female football fans in 2021, Ghafouri wrote on Instagram: “As a soccer player, I’ve indeed become humiliated when I play in an era when our mothers and sisters are prohibited from entering stadiums.”

Many fans suggested his career at Esteghlal, a championship winning team, was cut short in June as punishment for speaking out. Others argued that in his mid-30s, Ghafouri was too old for the Iranian top flight.

He recently tweeted: “Stop killing Kurdish people!!! Kurds are Iran itself … Killing Kurds is equal to killing Iran. If you are indifferent to the killing of people, you are not an Iranian and you are not even a human being … All tribes are from Iran. Do not kill people!!!”

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being British we are very used to picking another team to cheer on after England's men get knocked out of a tournament, because you know...

And it is exciting that Wales are in the World Cup too.

But seriously I'm going to be cheering on Iran after my home nations, because they're seriously awesome about standing up for what they believe in. (I'm personally not watching the games, but I'm reading about news because the human rights violations in Qatar.)

As well as Iran refusing to sing their national anthem in protest of what is going on back home. (Sadly at the same game England's men backed out of wearing an arm band in support of LGBT+ people in fear of getting a yellow piece of card)

Voria Ghafouri, who is not part of World Cup squad. Has been arrested as "warning to players" in Qatar. He has been really out spoken been outspoken in his defence of Iranian Kurds, telling the government on social media to stop killing Kurdish people. He has previously been detained for criticising the former Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif.

Like at great personal risk he has done this, and the Iranian players are also taking risks, and I honestly think the world should be like.

We are watching!

But I am really happy that England's and Germany's women have been there wearing the pro LGBTQIA+ arm band, and have been like, and what? That's bad AF.

Welsh fans also got into trouble and had rainbow hats confiscated as they tried to enter the stadium in them. And honestly that's still putting up the resistance. Which is really great.

We honestly need to stand up for human rights wherever we see abuses, and make sure we tell countries we are watching these people who have been arrested, so they cannot disappear.

Even if those abuses happen at home.

#Voria Ghafouri#worldcup#Football#humanrights#human rights#lgbtlove#lgbtqia#LGBT#gay rights#Racism#qatar world cup#qatar wc 2022#Iran

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iran's Israel attacks shed light on Swiss role as 'protecting power'

US Secretary of State John Kerry, right, speaks with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif before a bilateral meeting for a new round of nuclear talks with Iran at the Intercontinental Hotel in Geneva, Switzerland. file. | Image Credit: AP

Washington and Tehran have not had diplomatic relations for decades, but they had direct communication through the “Swiss Channel” before Iran…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Stopping the Iranian nuclear horn remains Israel’s top priority: Daniel 8 https://andrewtheprophetcom.wordpress.com/2024/03/05/stopping-the-iranian-nuclear-horn-remains-israels-top-priority-daniel-8/

0 notes

Text

Irã em alerta máximo enquanto Biden pondera resposta ao assassinato de militares dos EUA

Irã em alerta máximo enquanto Biden pondera resposta ao assassinato de militares dos EUA

Teerã alerta Washington, mas regime não tem certeza do grau de apoio à política externa intervencionista

O Irão disse aos EUA através de intermediários que se atacar directamente o solo iraniano, Teerão irá contra-atacar os activos americanos no Médio Oriente, arrastando os dois lados para um conflito directo.

O aviso surge enquanto o Irão espera em alerta máximo para ver como Joe Biden responderá à morte de três militares dos EUA considerados por Washington como mortos por uma milícia apoiada por Teerão baseada na Síria.

As bases dos EUA na Síria e no Iraque sofreram mais de 160 ataques de gravidade variável desde o ataque do Hamas a Israel, em 7 de Outubro .

Entre temores de uma represália dos EUA, o rial iraniano caiu para o seu ponto mais baixo em 40 anos em relação ao dólar, mesmo quando Teerão reiterou que o ataque foi obra de “grupos de resistência” independentes – a resposta padrão do Irão às acusações dos EUA de que prolifera a turbulência militar em todo o mundo. a região armando e treinando os grupos . O Hamas é designado grupo terrorista pelos EUA e pela UE.

O valor da moeda nacional do Irão caiu 15% desde 7 de Outubro. O líder supremo do Irão, o aiatolá Ali Khamenei, apelou a controlos mais rigorosos sobre a liquidez numa reunião com líderes empresariais, reflectindo a sua preocupação de que a inflação estava a destruir os padrões de vida e a criar uma atmosfera difícil antes das eleições parlamentares nacionais em Novembro. A inflação está em 40%.

Agora, os meios de comunicação social iranianos especulam abertamente sobre a natureza de possíveis represálias – baseando largamente as suas discussões em reportagens dos meios de comunicação social dos EUA. Ambos os lados sublinharam que não procuram uma guerra aberta, mas Teerão considera que um ataque dos EUA ao seu território é uma linha vermelha que será recebida com uma resposta adequada.

À medida que as tensões aumentavam, o Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros iraniano convocou o embaixador britânico, Simon Shercliff, na terça-feira para exigir que o Reino Unido ponha fim às suas alegações de que o Irão está a tentar intimidar dissidentes iranianos que vivem na Grã-Bretanha.

O ministro dos Negócios Estrangeiros iraniano, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, emitiu uma nota confiante de que os acontecimentos em toda a região ainda tendiam na direcção do Irão. Ele disse que a Casa Branca sabia bem que era necessária “uma solução política” para acabar com a carnificina na Faixa de Gaza sitiada e com a actual crise no Médio Oriente.

Ele disse: “A diplomacia está avançando neste caminho. Benjamin Netanyahu está chegando ao fim de sua vida política criminosa”.

Com um ataque dos EUA às posições iranianas dentro da Síria visto como a opção mais provável, o vice-ministro do Interior do Irão, Seyyed Majid Mirahmadi, numa reunião com os seus homólogos sírios discutiu a crise e insistiu que o chamado “eixo de resistência” estava à beira. da vitória.

Javad Zarif, antigo ministro dos Negócios Estrangeiros iraniano, disse acreditar que a “aura de invencibilidade” de Israel se desfez. Numa entrevista afirmou: “A política externa do regime israelita baseia-se em dois eixos: opressão e invencibilidade”.

Zarif disse que a política de guerra de Israel tem três pilares: a guerra deve ser fora de Israel, deve ser surpreendente e deve terminar rapidamente. Ele disse que tanto os dois eixos da política externa de Israel como os seus três pilares da política militar foram quebrados pelo ataque de 7 de Outubro.

Mas o próprio Irão enfrenta os seus próprios desafios: a agitação eclodiu em todo o Curdistão após a execução, na segunda-feira, de quatro curdos acusados pelo regime de cooperar com a Mossad, as agências de inteligência israelitas.

Imagens que circulam online mostram ruas desertas e lojas fechadas em Sanandaj, Saqqez, Mahabad, Bukan, Dehgolan e outras cidades.

Os quatro homens, todos membros do partido de esquerda Komala, foram executados por alegadamente terem planeado um atentado bombista em Isfahan no Verão passado, em colaboração com Israel.

Mehdi Saadati, membro da comissão de segurança nacional e política externa do parlamento, disse: “Estas execuções são uma lição para quem quer se opor à vontade da nação iraniana porque a nação iraniana irá puni-los pelos seus atos”.

Mas ainda não está claro se a última repressão está ligada ao nervosismo no Irão quanto ao grau de apoio à política externa intervencionista do regime.

Embora o apoio aos palestinianos seja generalizado na sociedade iraniana, o regime teme que o estado da economia e o descontentamento político geral possam reduzir a participação nas eleições parlamentares de Março, minando a sua reivindicação de legitimidade.

Na tentativa de aumentar a participação na votação, o número de urnas duplicou e os candidatos estão a ter mais tempo na televisão e na rádio para tentarem gerar um clima de entusiasmo. Não há “votação por correspondência”, mas serão implantadas numerosas estações móveis.

A participação nas eleições parlamentares de 2020 foi registada abaixo dos 42,5%, com a votação na capital, Teerão, a cair para 26,2% – os valores mais baixos desde a revolução de 1979. Espera-se algo semelhante desta vez. Mas se a participação cair abaixo dos 40%, seria um golpe para o prestígio do regime e confirmaria que a revolução está a sobreviver de uma mistura de repressão e alienação.

fonte https://www.theguardian.com/

Read the full article

0 notes

Video

youtube

Israel reveals a disaster among its forces after the execution of the leaders of H.M. S-5 and Iran begin escaping

Updates on the Al-Aqsa Flood operation presented in this episode of Samri Channel.

The beginning began with the American magazine Foreign Policy, which discussed Iran’s position on the ongoing war between Israel and the Gaza Strip, which heralded the outbreak of a direct confrontation between Tehran and Tel Aviv. However, despite the letter written by Iranian officials to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, to persuade him to engage in the conflict in support of Hamas, The possibility of an expanded regional war is low, and the reality of Iranian strategic thinking is more cautious than slogans. A report by the American magazine reviewed at least 7 reasons why Iran is likely to avoid starting a war with Israel on behalf of Hamas.

First: The report stated that Iran cannot mobilize Iranian society to engage in a new war as it did during the war with Iraq in the 1980s, when it was the continuous mobilization of human waves, among other factors, that resisted the Iraqi army and forced Baghdad to withdraw from Iranian territory. . The report added, “After decades have passed, society’s support for the political regime has declined,” pointing to the recent demonstrations in Iran, the economic crisis resulting in part from the sanctions led by Washington, and the escalation of discontent among the youth and the middle class.

Second: The report stated that the moderate movement within the Iranian government warned against direct Iranian interference in the war, adding that “the war in Gaza caused the deepening of political divisions in Tehran.” According to the assessments of Iranian extremists, the destruction of Hamas is automatically linked to the subsequent collapse of Hezbollah and, ultimately, to launching a military attack on Iran, which is why they support the targeting of American bases in Iraq and Syria by Iranian proxies. However, the report pointed out that this view greatly contradicts the view held by moderate officials, especially Zarif, who has constantly warned of the destructive consequences of Iran’s potential involvement in a war with the United States.

According to former Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, if Iran takes a more extreme position on Gaza, it could spark a deadly conflict with the United States, which Israel would welcome. Thirdly, the report pointed out that “Israel’s clear failure to deter the Hamas attack on October 7th does not change Tehran’s strategic calculations vis-à-vis Israel,” adding that despite Israel’s reliance on high-tech defense technology such as the Iron Dome defense system, it has directed Hamas dealt a major military and intelligence strike against it, thus destroying its policy of deterrence.

He pointed out that “this does not change Iran’s view of Israel or the power dynamics in the region, and that although the Hamas operation destabilized Israel’s long-standing deterrence strategy, it does not provide Iran with the opportunity to challenge Israel using missile force.” The report continued that, on the contrary, Iran may believe that Israel feels that restoring deterrence is an existential priority for which it is worth taking an exceptional military or political risk. Fourth: Contrary to popular opinion, neither Hamas nor even Hezbollah are agents of Iran, and what is more accurate is to consider them as allies of Iran as non-governmental forces, according to the report, which added that “although Hamas has aligned its actions with Iran, its approach may differ from it.” This was notably the case during the Syrian Civil War when Hamas supported Sunni rebels opposed to Syrian President Assad.

Fifth: The report indicated that Moscow and Beijing, two of Iran's strategic partners, did not express their full support for Hamas, indicating that Iran sought an alliance with China and Russia as part of its policy of looking towards the East, and therefore it would not want to spoil its relations with these two countries. According to the American report, Iran is following a policy in Gaza similar to the one it adopted after observing the Chinese-Russian wait-and-see approach when the Taliban took over Kabul two years ago, pointing out that Tehran’s goal is to avoid isolation in major international crises. Sixth: The report spoke of the existence of a deep belief among decision-makers in Iran that the Arab sheikhdoms in the Gulf would welcome a large-scale war between Iran and Israel, ruling out the possibility that Iran hopes that the Arab countries will sever their relations with Israel as a result of a broader war.

#Egypt

#Palestine

#Gaza

0 notes

Text

Army activity versus Iran is feasible if United States permissions stop working to quit Tehran from endangering Washington’s passions according to Brian Hook, the United States State Division’s supervisor of plan preparation and also head of the Iran Activity Team

Hook made the dangers on Thursday a day after Tehran stated it was not looking for battle with any type of various other country.

He stated the UNITED STATE would certainly likes to involve with the nation diplomatically, yet the armed forces choice gets on the table.

Press TELEVISION records: “We have actually been really clear with the Iranian program that we will certainly not be reluctant to utilize armed forces pressure when our passions are intimidated,” Hook stated.

” I assume now, while we have the armed forces choice on the table, our choice is to utilize every one of the devices that go to our disposal diplomatically,” he stated.

He was talking at an interview at Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling in Washington, DC in feedback to an inquiry on feasible following actions the United States can take versus Iran in its optimal stress war the Islamic Republic.

Hook talked at an occasion held to show items of what he declared were Iranian tools and also armed forces devices turned over to the United States by Saudi Arabia.

Outward Bound United States Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley held a comparable occasion in the exact same place last November, showing what she affirmed scraps of a projectile offered by Iran to Yemen’s Houthis.

The program attracted taunting from numerous onlookers that examined the credibility of the cases made by a mediator without any expertise of armed forces issues.

Foreign Preacher Mohammad Javad Zarif stated on Twitter then that Iran would certainly not publish the “Iranian Criterion Institute logo design” on its rockets as held true worrying the “proof” presented by the United States.

” Attempt producing ‘proof’ once more,” he stated, mentioning that a ruined rocket would certainly not “land completely constructed.”

On Thursday, United States media wondered about the timing of the occasion, stating it was an effort to change the narrative far from Saudi Arabia, which has actually come under extreme examination over the murder of reporter Jamal Khashoggi.

It came as the Us senate on Wednesday progressed a resolution that would certainly finish United States armed forces assistance for the Saudi armed forces project in Yemen in a sharp rebuke to Head Of State Donald Trump.

Hook attempted to eliminate those inquiries, stating there “isn’t anything connected to what’s taking place in Saudi Arabia.”

He likewise looked for to push back on objections that the display screen was a political feat by the Trump management that can enhance stress in the area.

” This is basically out in wide daytime Iran’s rockets and also tiny arms and also rockets and also UAVs and also drones,” he stated.

On Wednesday, Leader of the Islamic Change Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei emphasized that the Iranian Military have to create their abilities to discourage any type of prospective assailant. The Leader, nevertheless, stated the Islamic Republic is not after a battle with any type of nation.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Politics of Culture and Communication and the Islamic Republic of Iran

Mehdi Semati

Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL, USA

[email protected]

The Islamic Republic of Iran remains a foreign policy ‘challenge’ to the prevailing international order, though it might be more accurate to call it international disorder. The disorder came into sharp view recently when Mohammad Javad Zarif, Iranian foreign minister, accompanied Federica Mogherini, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, as she unveiled elaborate plans to undermine the administration of Donald Trump and salvage the ‘Iran Deal’. The plan involved a ‘special vehicle’ conceived to circumvent the new and renewed US financial sanctions against Iran and companies that seek to do business there. As if to make the disorder even more pronounced, France, Germany, Britain, Russia and China announced their support for the plan in a joint statement. The gap that separates the European Union and the United States regarding Iran is as much about American belligerence and Trump’s shenanigans in the Middle East as it is about the Islamic Republic of Iran’s survival instinct and its strategic and geopolitical steps and missteps. Regardless of how one characterizes the internal and external factors at play, the Islamic Republic of Iran remains very much a ‘problem’ on the global stage.

That gap between the European Union and the United States is also fueled by the internal contradictions of the discursive position Iran occupies as an ‘Islamic nation’ and a ‘trouble spot’ in the ‘Middle East’ in Western geopolitical and popular imaginaries. These contradictions include an insistence on the backward character of Iranian rulers (and Iran as a nation of ‘fundamentalists’) while warning about Iran’s capabilities of enriching uranium, nuclear technology and long-range ballistic missiles. In other words, we are warned about a

backward nation with fanatical rulers who have nevertheless managed to build technologically advanced (and lethal) weaponry, with nuclear technology as well. More important, the Western imaginary is confounded by contradictions: Iran is a morbid object of geopolitical discourse and it is the place from which remarkable cultural forms and productions continue to emerge.

The contributors to this special issue of the Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication engage with these cultural forms and institutions and the sociopolitical contexts of their production, circulation, reception and operation. These cultural forms include popular music, theater, poetry, museums, cinema and art. The contributors address the politics of the Western discourses on Iran as they discuss these cultural forms at the intersection of political, social and cultural registers and their co-constitutive relationships.

In her contribution to this collection of essays, Theresa Steward examines the fraught relationship between Iranian musicians and the Western media and their audiences. For example, once moving beyond the novelty of rock or pop music in Iran, Western observers often look for signs of ‘resistance’ and ‘revolutionary’ culture of artist seeking to escape the repression of the ayatollahs. In this scenario, Iranian musicians are engaged in a constant battle for survival against a loathsome state in a closed and oppressive social space. This reductive tendency, which collapses all aspects of culture into a ‘political’ dimension, is a feature of much writing on culture in Iran. The reality is far more interesting and complicated than such depictions or descriptions allow. As Steward shows, musicians are aware of this Western appetite for ‘resistance’ narratives, and some, with a Western audience in mind, use it to their strategic advantage. In her essay, Steward focuses on Bahman Ghobadi’s No One Knows About Persian Cats (2009) (a film about the ‘underground’ music scene in Iran), to demonstrate how Iranian musicians occupy a multi-faceted and complex position that goes well beyond alleged perpetual ‘protest’ and ‘defiance.’

Erum Naqvi’s contribution addresses the thriving theater scene in Iran. It might be accurate to say that Iran has never had such a dynamic theater scene, from mainstream and well-known Iranian and foreign plays, to experimental and musical theaters. Arguably, theater in Iran has never been as popular as it is today; many shows in Tehran and other major cities are regularly sold out. In addition, newer genres, such as ‘horror’ (vahshat), are refashioning this ancient art form. These are remarkable developments that repudiate ignorant comments about Iranian cultural and social space made by those who wish to vilify the Islamic Republic. More importantly, the developments are noteworthy, as they shed light on the dynamism of the cultural sphere, in spite of the state.

This dynamism can be observed, for example, in the way art collectives run by younger artists are reimagining and rearticulating historical art forms (e.g., ruhowzi) that were deemed too ‘un-Islamic’ to be performed in public spaces after the revolution in 1979. Naqvi’s essay presents this re-articulation as a vibrant cultural re-production of the boundaries of various genres, which are constantly renegotiated, reimagined and playfully reworked. These reimaginings are not attempts at resistance but are reformulations of the classical canons of theater in Iran, with inflections of joy, aspirations, fears and anxieties that are relevant in the contemporary conjuncture. In this playful rearticulation, where the past is restated in the aesthetic grammar of today, we find the pleasures of the popular.

Shareah Taleghani’s essay addresses the poetry of Solmaz Sharif, an Iranian-American poet whose work has been celebrated for her experimentation with form and uncompromising critique of ‘war on terror’ and her denunciation of militarism and war. Taleghani’s focus on Sharif ’s poetry in Look (2016) is partly informed by the post-colonial literature on translation theory (with which she examines Sharif’s work as a subversive act of ‘translation’ as cultural practice), and as an assessment of the efficacy of intralingual modes of translation.

Sharif ’s poems render the English language unfamiliar and foreignize it; the audience’s complicity in the sanitizing effects of militarized language is unsettled. Taleghani explores how, by reappropriating military discourse, Sharif’s poetry is a form of ‘resistant domestication’ that reflects the experience of diaspora, exile, immigration, transnational identity, belonging and estrangement, all shaped by her own experience as a member of the Iranian-American diasporic community.

In her contribution to this collection, Anna Vanzan addresses the topic of museums in Iran. As a product of the Enlightenment era, Vanzan identifies how museums are instruments to rationalize human affairs and their place in the cosmological order. The efforts by the Iranian state to build museums is not unique; many states have done so. By focusing on the Holy Defense Museum and the Martyrs’ Museum, Vanzan shows the ideological interests of the state in aestheticizing the war via religious iconography and symbolism and mobilizing collective memory as projects of political identity and popular mobilization. I would argue that the Iranian state’s recent interest in building lavish museums is no longer an attempt to ‘stage a revolution’ (Chelkowski and Dabashi 1999), but more an effort to revive it, and resuscitate its affective power and ideological allure, at times also injecting nationalistic mythologies (i.e., elements of pre-Islamic and Persian identities) into it. In fact, such attempts by the state reflect its anxieties about its perceived failure to maintain a revolutionary state and to acknowledge tacitly the unfulfilled promises of a forty-year-old revolution. Today, many cultural forms, implicitly and sometimes explicitly contain elements of ‘popular history’ that entertain narratives about such promises and about life before the 1979 revolution.

Niloo Sarabi’s contribution offers a rereading of Marzieh Meshkini’s Roozi ke zan shodam (The day I became a woman), a critically acclaimed film that takes up the question of gender and women’s position in the Islamic Republic. This film was released nearly two decades ago and is clearly a testament to the ongoing and relentless assertion of the agency of Iranian women; furthermore, it illustrates that popular culture in the Islamic Republic has long been a contentious cite of struggle over the meaning of gender, womanhood and women’s role in society. As Hamid Naficy argued, with regard to Iranian cinema, ‘a unique and unexpected achievement of this cinema has been the significant and signifying role of women both behind and in front of the camera, leading to “women’s cinema” ’ (Naficy 2003: 138). One of the paradoxes of ‘Islamicization’ of Iranian society has been the opening of various cultural industries to women, who, in turn, have challenged the terms of their representation. As Sarabi argues, the visual codes of representation of women in this context have entailed both limitations and opportunities with regard to the portrayal of women in the cinema and their presence in the film industry. Moreover, her discussion acknowledges the longstanding internal debates in Iran on gender and gender roles. Sarabi reflects on the ways in which Meshkini’s visual aesthetics, the formal characteristics of her film, and its other narrative properties contribute to debates in Iran on the veil, gender norms, social mobility and women’s pleasure.

Alice Bombardier’s essay addresses painting and art in Iran. Nothing seems to embody the contradictions of the Islamic Republic like the art scene in Iran.

Just as the US sanctions were renewed and the Iranian currency is in decline, art auctions at posh hotel ballrooms in North Tehran have brought large sums for various works of arts, especially paintings. A recent headline states, ‘Iran art auction rakes in millions amid pressure over sanctions’ (Najib 2019). At an auction in Tehran recently, a journalist told me that art journalists in Iran believe that collecting expensive art is a good way for billionaires to ‘park’ cash. More ominously, and perhaps cynically, another journalist joked that buying expensive art is one of the best methods of laundering money. Thus, the renewed interest in the art scene in Iran is propelled by its connection to the global art market and by the participation of contemporary Iranian artists in the global art scene. The interest is also driven by recent scholarship on Iranian art, to which Bombardier has contributed. In some ways, the renewed interest in painting might also reflect a desire to rediscover the suppressed history of painting as a cultural form, suppressed by a history born out of authoritarian state (under the Pahlavi monarchy), geopolitical developments (e.g., the red scare of the Cold War era) and post-revolution domestic politics (a religious state and its cultural revolution).

Bombardier’s research is distinctive, in the sense that her work is grounded in a historical framework that is cognizant of both continuity and breaks in the ongoing fate of painting. In her contribution to this collection, Bombardier traces the origins of ‘New Painting’, a term she prefers over the Persian renditions of ‘contemporary painting’ (naqqashi-i muasir) or ‘modern painting’ (naqqashi-i modern). The artists of ‘new painting’ were innovative in many respects. They introduced new methods, forms, and, perhaps more important, ‘social innovations through new channels of collective creation’ (e.g., associations, galleries/clubs, conferences, journals). Yet, for all the innovations of these pioneers introduced, their history and contributions have been forgotten, or even erased, from most accounts of painting in Iran. Bombardier offers explanations grounded in an analysis of the political and social contexts of the era in which these pioneers made their contribution and of the subsequent contexts of the reception of their work. Her essay is an important step in recovering their legacy.

The articles in this collection, individually and collectively, challenge the prevailing views regarding Iran and cultural production and practices in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The contributors question simplistic explanations about Iran and the Islamic Republic, a feature of far too much commentary about Middle Eastern societies and cultures. The analyses of these authors demonstrate that the realities of Iran and its people are far more complicated, interesting and dynamic than the prevailing discourses about Iran would suggest. It might be safe to say, Iran is no exception in being misunderstood as a country in the Middle East, an ‘imaginative geography,’ to use Edward Said’s (1979) language.

References

Bombardier, Alice (2017). Les pionniers de la Nouvelle peinture en Iran. Œuvres méconnues, activités novatrices et scandales au tournant des années 1940. Bern: Peter Lang.

Chelkowski, Peter and Hamid Dabashi (1999). Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran. New York: New York University Press.

Grigor, Talinn (2014). Contemporary Iranian Art: From the Street to the Studio. London: Reaktion Books.

Hirsh, Michael (2018). Is Iran Deal Finally Dead? Foreign Policy. Accessed 18 Jan. 2019, online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/25/iran‐nuclear‐deal‐last‐stand/, 25 September 2018.

Keshmirshekan, Hamid (2014). Contemporary Iranian Art: New Perspectives. London: Saqi Books.

Naficy, Hamid (1991). Women and the Semiotics of Veiling and Vision in Cinema. American Journal of Semiotics 8 (1–2): 47–64.

Naficy, Hamid (1994). Veiled Visions/Powerful Presences: Women in Postrevolutionary Iranian Cinema. In Mahnaz Afkhami and Erika Friedl (eds.), In the Eye of the Storm: Women in Postrevolutionary Iran, pp. 131–150. London: I.B. Tauris.

Naficy, Hamid (2003). Poetics and Politics of Veil, Voice, and Vision in Iranian Postrevolutionary Cinema. In David A. Bailey and Gilane Tawadros (eds.), Veil: Veiling, Representation and Contemporary Art, pp. 136–159. London: Institute of International Visual Arts with Modern Art Oxford.

Najib, Mohammad Ali (2019). Iran Art Auction Rakes in Millions amid Pressure over Sanctions. Aljazeera. Accessed 18 January 2019 online: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/iran‐art‐auction‐rakes‐millions‐pressure‐sanctions‐19011217355 9995.html, 14 January 2019.

Nooshin, Laudan (2017). Whose Liberation? Iranian Popular Music and the Fetishization of Resistance. Popular Communication: The International Journal of Media and Culture 15 (3): 163–191.

Said, Edward (1979). Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Said, Edward (1994). Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books.

Semati, Mehdi (2017). Sounds Like Iran: On Popular Music of Iran. Popular Communication: The International Journal of Media and Culture 15 (3): 155–162.

1 note

·

View note

Text

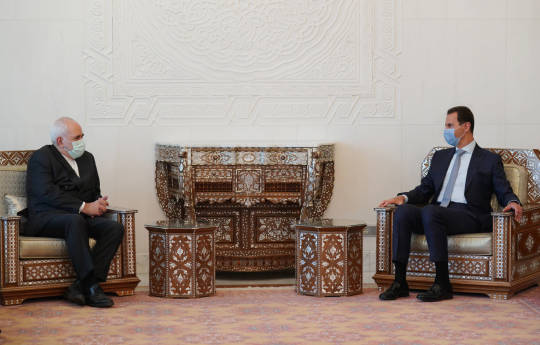

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif in Damascus today, 12 May 2021

Topics such as Palestine were discussed

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

The new administration in Washington has a fundamental choice to make. It can embrace the failed policies of the Trump administration and continue down the path of disdain for international cooperation and international law -- a contempt powerfully evident in the United States' decision in 2018 to unilaterally withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal, that had been signed by Iran, China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the European Union just three years earlier. Or the new administration can shed the failed assumptions of the past and seek to promote peace and comity in the region.

U.S. President Joe Biden can choose a better path by ending Trump's failed policy of "maximum pressure" and returning to the deal his predecessor abandoned. If he does, Iran will likewise return to full implementation of our commitments under the nuclear deal. But if Washington instead insists on extracting concessions, then this opportunity will be lost.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russia, Turkey, and Iran Drawing Closer

Russia, Turkey, and Iran Drawing Closer

March 2021: Leaders from Iran traveled to Turkey and met this past week. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif and Turkey’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Mevlut Cavusoglu got together as “brothers”.

Iran’s Zarif commented, “As before, constructive engagement on bilateral and regional issues. Ultimate aim: Apply Iran and Turkey’s experience of 400 years of peace to our region. Together, anything is…

View On WordPress

#Javad Zarif#killer#Mevlut Cavusoglu#President Joe Biden#President Recep Erdogan#Turkey#Vladimir Putin

1 note

·

View note

Text

Iran's Israel attacks shed light on Swiss role as 'protecting power'

US Secretary of State John Kerry, right, speaks with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif before a bilateral meeting for a new round of nuclear talks with Iran at the Intercontinental Hotel in Geneva, Switzerland. file. | Image Credit: AP

Washington and Tehran have not had diplomatic relations for decades, but they had direct communication through the “Swiss Channel” before Iran…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Stopping the Iranian nuclear horn remains Israel’s top priority: Daniel 8

IRANIAN PRESIDENT Hassan Rouhani (right) and Foreign Minister Javad Zarif. Who wanted to pay the price of moral action to truly stop Iran?(photo credit: DANISH SIDDIQUI/ REUTERS)

Preventing an Iranian nuclear weapon remains Israel’s top priority – opinion

The October 7 attack taught Israel that it has no other choice but to confront Iran-backed threats on all fronts, sooner or later.

By JACOB…

View On WordPress

0 notes