#Roheeni

Text

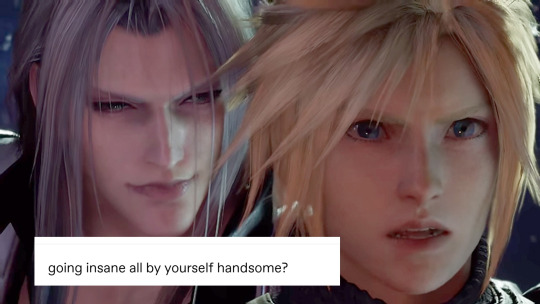

So I saw the screenshot and immediately had to do a redraw for myself. Gotta take every chance I get to draw even more Agony and Roheeni.

#essarttag#dungeons and dragons#art#original#dnd#tiefling#sorcerer#agony#final fantasy#cloud#sephiroth#redraw#screenshot redraw#devil#Roheeni

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

WU Reviews: The Handmaid’s Tale Season 2 Episode 1 Recap by Roheeni Saxena ‘08 (@RoheeniSax)

Hulu

Last year, Roheeni Saxena ‘08 gave us a brilliant two-part overview of Season 1 of The Handmaid’s Tale. This year, she’s recapping every individual episode of Season 2 and breaking down each haunting second. Suffice to say, SPOILER ALERT. With no further ado, let’s venture into the first episode and see what has befallen the women of Gilead since the end of Season 1.

It is ten minutes into the first episode of Handmaid’s Tale Season 2 before we hear any words. Alongside Offred, we are thrust into a cacophony of noise, fear, confusion, danger, guns, aggressive dogs, and choppy camera work that heightens our disorientation. Then we come to the sudden realization that we have been rounded up to die. The floodlights come up on Fenway Park, a familiar Boston landmark. It has been transformed into a mass execution venue, as though the state-sanctioned murder of fifty tenacious and strong-willed women is a sport that thousands would happily show up to watch.

As viewers, we wonder, “Are we watching a scene from the end of the season? Will the rest of the season be a flashback? What could Season 2 look like if the handmaids are killed within the first ten minutes? Also, DAMMIT, we should have known better than to cheer on the handmaids’ rebellion against Aunt Lydia – and the handmaids should have known better than to rebel, what did they think would happen to them?” This last thought, that we should have known better, is undoubtedly shared by each of the handmaids on the gallows. The inevitable rise of this thought in the viewer’s mind comes from skillful suggestion and manipulation achieved by the frenetic unfolding of these non-verbal first ten minutes. We are there with the handmaids, sharing their desperation.

The handmaids stand, necks in nooses, and Kate Bush’s “This Woman’s Work” comes in on the soundtrack. It is a little on the nose, and yet poignant in contrast to the visuals we see underneath it. We are privy to the handmaids’ last moments: some cry, pray, wet themselves, and some just reach for each other’s hands.

Like the handmaids, we are in disbelief as the executioner shouts, “By his hand,” and the gallows platforms drop. But they only drop a handful of inches. Together, handmaids and viewers realize this is an elaborate farce to demonstrate how little power the handmaids have, and how much danger they put themselves in when they decided not to kill Janine. Offred verbalizes the viewers thoughts, “What the actual fuck?”

In this cold open, Season 2 of Handmaid’s Tale loudly announces itself as a furious force demanding our attention. As this show’s momentum drives it towards an unknown horizon Season 1 ended where the book ended), it takes these first ten minutes to demonstrate that this new season will deliver more frank brutality, more incisive insight, and more painful honesty. Season 2 will continue the excellent direction, camera work, art styling, and acting that were displayed in Season 1, but with an aggressive expansiveness. Season 2 promises to make a stronger statement on life in Gilead, and a more urgent commentary on how Gilead came to be.

As the action of the episode continues, its first real speech comes from Aunt Lydia, a woman who has secured her position in Gilead by actively oppressing other women. In granting Aunt Lydia the first speech of this season, the show asserts this season’s main theme: the complex relationships between women trying to survive in a world that hates women (like ours does, but more violently and candidly).

The remainder of Episode 1 follows pregnant Offred/June. Aunt Lydia attempts to use her pregnancy to separate her from the other handmaids, to scapegoat her for the consequences of their rebellion – but does she truly believe that a group of women trapped as reproductive slaves will fall for the myth that their unwillingly pregnant leader was looking out for herself? As June resists the weaponization of her pregnancy, we learn that “difficult” handmaids are isolated and chained until they deliver, which is reminiscent of current laws forcing incarcerated women to be shackled to the bed while in labor, as though they could escape while crowning.

This episode’s flashbacks are a heightened echo of today’s political climate. They begin with Luke placing his signature on June’s birth control renewal. Though they both comment on how strange this is, they comply with this new requirement, offering no resistance. While it is trendy right now to refer to Handmaid’s Tale as a mirror of current events, it is not really a mirror. Instead, it is something much more valuable. The show gives viewers a window into the moments when residents of a pre-Gilead world could have stood up to changing norms, and either did, or were too wrapped up in their own lives to do so – in this way, it is a call to arms that we should all be listening to.

In the next flashback, June is addressed as Ms. Bankole by a hospital worker. Watching her firmly assert her name as “June Osborne” in front of her daughter Hannah is inspiring, and reminds the viewer that the best way to embody strong feminism is to push back firmly when society’s patriarchal tendencies violate our selfhood and our boundaries.

Moments later, we watch June’s escape from the Handmaid’s pregnancy center. In this sequence, we are granted a series of tight shots on her face, and wide shots of her solitary body, hurrying through the dark with a flashlight. This imagery is not lost on the viewer – she is alone in this escape, and the future is uncertain, unilluminated. Though this staging emphasizes June’s escape as a solitary endeavor, it also shows that even in escape she is denied agency. June does not know where she is going. She runs until unseen hands lock her into a truck that facilitates her escape to an unknown location.

When she arrives at her hideout, she is again stripped of agency, this time by Nick. She is told to wait, instructed to burn her clothes and cut her hair. Left alone to accomplish these tasks, June finally takes control of her body, using the scissors meant for her hair to cut the red tag out of her ear. This moment stands alone in Episode 1 as June’s first self-driven agency-asserting action that goes unthwarted. She tosses the red tag into the fire, and we hear it clatter in the silence.

The final shots of this episode show June’s face full of determination, her blood-soaked underwear-clad body lit by fire that burns her Handmaid’s costume. It is a beautiful shot. However, in a rare moment for this show, the script fails to live up to this staging. The episode ends with June stating her name, her age, her physical stats, her origins, her fertility, her pregnancy status, and ends with her saying, “I am free.” Here, a simpler and stronger writing maneuver would have been for June to simply say, “My name is June Osborne.” This choice would have harkened back to the assertions she made about her name in this episode’s flashbacks, and would have reminded the viewer that, in this moment, she is taking back her identity as a human, rather than as a reproductive object.

Overall, this first episode of Handmaid’s Tale Season 2 was an audacious announcement that this show’s most shocking, aggressive, and politically relevant storylines will be coming to viewers this season, while everything excellent from Season 1 (acting, direction, camera work, color palette, writing) will continue through Season 2. With this announcement, Handmaid’s Tale Season 2 Episode 1 ensures that viewers will keep watching this bolder braver season unfold.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

You shouldn’t have done that, my dearest....

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Found this song, thought it fit Agony. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EKLWC93nvAU

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

WU Reviews: Roheeni Saxena '08 (@RoheeniSax) Reviews The Handmaid's Tale: Part II

(Source)

If Part I of Roheeni Saxena ‘08’s review of The Handmaid’s Tale wasn’t enough for you, we bring you Part II. MAJOR SPOILER ALERT: what follows are notes on key moments from all ten episodes of The Handmaid’s Tale. If you do not want to be spoiled, please watch the show first. Then return to WU Reviews to read the below and let us know your thoughts about the show’s most brutal, searing, and memorable moments.

Episode 1

The brainwashing of Handmaids at the Red Center is horrifying for any woman who has ever been raped or faced an attempted rape (1/6 women according to RAINN).

The initial rape of the protagonist seems to go on for hours. The complicity of the commander’s wife in this rape is rage-inducing.

Minutes later, the Handmaids gather to brutally murder a man (with their bare hands) who has committed a rape of another handmaid. A man who committed a rape without society’s consent. It seems that in this Max-Weber-approved world, the state has a monopoly not only on violence, but on violence against women.

Episode 2

One-eyed Janine gives painful, non-medically assisted birth to healthy girl who is immediately taken away from her and given to another woman. This drives home the role that women with status play in oppressing other women in Gilead.

If the mission of fourth wave feminism is to champion intersectionality and show how women can be used by the hegemony to oppress other women, then Gilead shows how that dynamic might be exploited by the most violent state actors.

Episode 3

The star of Episode 3 is Alexis Bledel, though her character doesn’t utter a word. We watch her, a gay woman, lose her status as a sex slave, lose a love she has found in this new terrible world, and then her clitoris.

We’re also given insight into how the world slowly descended into this state: “Nothing changes instantly. In a gradually heating bathtub, you’d be boiled to death before you knew it.”

Episodes 4-6

More vivid flashbacks, showing the life before Gilead, the rise of this world, and more of June’s oppression by the wife of her commander – Serena Joy played a critical role in the formation of this world that now oppresses her.

This subjugation of women by women reaches its zenith in episodes 5 and 6, when June’s mistress asks her to have sex with another man to assist her getting pregnant, and when we learn that Gilead is expecting to sell its handmaidens in trade.

Female politicians from other countries turn a blind eye to cries for help, in favor of seeking women for breeding. Women in power never hesitate to turn on other women for their own benefit.

Episode 7

The fall of the US from June’s husband’s perspective. A strange choice, and one that is jarring after so many episodes building the world of Gilead.

Some interesting insights into how terrifying this world can be, even for a man who is relatively safe from its oppression.

Episode 8

We see where Gilead sends women who fail to conform to the new normal. A brothel where June is reunited with her best friend. And again, women are complicit in the oppression of other women – they run this sex-slave brothel.

Are we surprised that the only female black main character is stuck in this brothel? No, because Gilead, like our current society, oppresses women of color more brutally than it oppresses white women.

Episode 9

Finally, a realistic depiction of the way women would inevitably rebel against this brutality. Suicide, threats of infanticide, manipulation of men.

Janine’s increasing insanity shows us a descent into chaos that feels frighteningly familiar. We realize that Janine is the only one reacting to this new world in a way that maintains her humanity. She reacts with alternating hope, derision, fear, and incredulity.

Episode 10

Pushed to the breaking point of their personhood, the Handmaids refuse to stone Janine to death for her attempted infanticide. A brief moment of empowerment is followed by bewilderment, confusion, and fear. By the end of this episode, we come to realize this is the pattern of all interactions in Gilead.

The end of the timeline given in Atwood’s novel. The next season will be even less predictable and certain.

#wu review#wellesley underground#the handmaid's tale#gender-based violence#intersectional feminism#television#roheeni saxena

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

WU Reviews: Roheeni Saxena ‘08 (@RoheeniSax) Reviews The Handmaid's Tale: Part I

(Source)

‘08 alum, Roheeni Saxena, has many compelling thoughts about The Handmaid’s Tale. Therefore, the WU Reviews series is proud to present an in-depth two-part review of the series. Part I, which you can read below, is an overview of the entire show with insights into the conversation around this series, its depictions of gender-based violence, and the need for everyone to educate themselves about intersectional feminism. Read on...

“Now I’m awake to the world. I was asleep before, that’s how we let it happen. When they slaughtered congress, we didn’t wake up. When they blamed terrorists, and suspended the constitution, we didn’t wake up then either. They said it would be temporary. Nothing changes instantly. In a gradually heating bathtub, you’d be boiled to death before you knew it.”

The Handmaid’s Tale is easily the best thing on TV in 2017, and if you haven’t watched it you should. The novel by Margaret Atwood was one of my favorites as a young adult, but the TV show surpasses it. The book gives us insight into the brutal world of Gilead, through a diary-like narrative provided by Offred, the protagonist, but reading the text is less visceral and tangible than watching this show. The show is terrifying, haunting, and shockingly similar to real life experiences of gender-based violence. The Handmaid’s Tale is an artful, brutal, and precise piece of television; a rare instance in which a film/TV interpretation of a book expands upon the source material and enhances it.

From a technical standpoint, there’s little to fault the show for. Every acting performance is flawlessly strong, particularly Elisabeth Moss (Offred) and Yvonne Strahovski (Serena Joy). I grew to dislike Alexis Bledel for her flat portrayal of intersectionally ignorant and privileged Rory Gilmore, but she is absolutely captivating in The Handmaid’s Tale. Each of the relationships are tense, careful, and gripping. The limitations of sparse language required by the Gilead regime imbue every non-verbal interaction with powerful subtext. The actors uniformly rise to this challenge.

Intense close-ups, especially of Elisabeth Moss, make the viewer feel like they’re personally experiencing everything she experiences. We never really observe her, instead we are her, feeling every time she suppresses her true self, every sense of danger, every fear, every mistrust, and every violation of her body and her humanity. Cinematically, these intense close-ups are the equivalent of providing the audience with a first-person narrative. The camera and the audience are as pinned in and controlled as the characters, with no knowledge or information that the characters do not have. The camera rarely leaves the circle of action, so the viewer feels as though they’re right there in the scene with the characters. When the characters are confused and scared, so are the viewers. And that’s most of the time.

The sparse language of the show is a direct contrast with its lush visuals, which call to mind the oil paintings of Johannes Vermeer. The art direction for the show is exact and stunning and chilling. The world of Gilead is bathed in a landscape of turquoise, the color of the commanders’ wives, clearly delineating the power structure of the show, which depicts a world in which women are made complicit in the oppression of other women. The red of the Handmaidens stand out like blood against this serene backdrop.

This contrast is intentional. The Handmaids wear the red of menstruation, signifying shame, guilt, and pain. The Handmaids are the only characters with any connection to their humanity, to their bodies, and to their reproductive systems, which are filled with blood and gore and the ability to generate new humans (also, just a reminder: women are not baby factories, women are people). They are made faceless by their bonnets, blindered like horses, treated like animals, forced to breed. Their clothing marks them as tainted as Hester Prynne’s scarlet letter. This extreme demarcation can only be really understood with a visual medium – Atwood’s novel was never able to make their presence seem quite as stark.

Additionally, the show makes the world of Gilead exceptionally eerie by presenting it side by side with flashbacks to the current day. In flashbacks, we see the characters wearing athleisure that look like ours, drinking in college, going for runs, and complaining about Uber. Then, that imagery is cut directly against the ageless imagery of Gilead, with its limited color palette, and its prescribed clothing that is reminiscent of more ancient, conservative garb.

Margaret Atwood’s novel was brilliant in its delicate remix of fascism and oppressive regimes. She took aspects of almost every oppressive culture and threw them together in a way that was timelessly recognizable and relatable. She’s been quoted as stating that every oppressive tactic she wrote about came from a true historical occurrence, a fact that just drives home how universal the oppression of women really is.

However, this show is being praised as extremely timely by many, and this claim ignores the reality of intersectional oppression. The show isn’t particularly timely in light of this new, more overtly anti-female administration – in fact, it’s coming all but too late for those of us who live in a space of intersectionality. Women of color, queer women, disabled women, all women whose lives are steeped in the stifling pressure of systemic dehumanization will find this show incredibly hard to watch. The depiction of a ritualized, societally endorsed rape will feel uncomfortably familiar to these women, whose bodies are also consistently violated by current societal structures.

All their lives, women of color, queer women, women marginalized in terms of multiple aspects of their personalities have been screaming for help, trying desperately to get more privileged women to notice their distinctive struggles. These women are more likely to be victims of domestic violence, they’re more likely to be victimized by the state, and they’re more likely to be disrespected by their communities. For these women, the show is less of a brilliant, incisive insight into the current moment, and more of a violently brutal reminder of who has the power: everyone else but them.

The Handmaid’s Tale is an incredible piece of television, and you should absolutely watch it. When you watch it, consider how the power structures being depicted in this show are merely allegorical representations of oppressive power structures that you’re currently living within. Watch this, and be inspired to fight for change.

#wu review#wellesley underground#the handmaid's tale#gender-based violence#intersectional feminism#roheeni saxena#television

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jess Malory was working for Roheeni all along to betray the party!!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WU Reviews: The Handmaid’s Tale Season 2 Episode 2 Recap by Roheeni Saxena ‘08 (@RoheeniSax)

Handmaid’s Tale Episode 2 opens, and we are with June, laying in the back of a flatbed truck, while she delivers a monologue about freedom, wondering aloud, “is this what freedom is?” Unfortunately, this opening speech, like the final lines of Episode 1 (see previous review), is lacking. This writing issue is likely to continue throughout season 2: without Margaret Atwood’s precise and purposeful writing to guide June’s monologues, her interior dialogue is becoming increasingly inelegant. However, (if we are being VERY generous) the deterioration of June’s critical thinking may also be a purposeful choice made by the writers. When she is delivered to her new hiding place, she thanks the man who transported her, and in parting she says, “under his eye,” leaving the viewer to wonder about the deterioration of June’s mind - Gilead has begun to colonize her thoughts. Regardless of the colonization of June’s mind, the real thrust of Episode 2 lies in Emily’s storyline.

In Episode 2, for the first time, the viewer enters the world of “the colonies,” where Alexis Bledel’s Emily was banished at the end of Season 1. Bledel’s Season 1 performance was simultaneously surprising and inspired – given the opportunity to play something other than a Rory-Gilmore-type, Bledel’s genuine talent and skill were undeniable. Episode 2 is absolutely written to (once more) show off what Alexis Bledel can do with a real part. As she returns to the show, her on-screen presence bursts into the episode, shoveling dirt in the colonies, where she has been banished as an “unwoman”. Emily’s inner strength and intense fear while living in the colonies are both palpable, but the most interesting scenes in her storyline are her pre-Gilead flashbacks. In these flashbacks, we see her as a brave gay academic, as a gay woman whose most prominent academic mentor has been lynched on campus for being gay, and as a woman attempting to flee the country with her wife and son.

In her flashbacks, Emily lectures on the microbiome, shutting down mansplaining students in her classroom, and encouraging her female students of color to pursue science (as a WOC STEM PhD candidate myself, this is particularly compelling to me). As the pre-Gilead timeline progresses, Emily and her department chair (who is gay, just like Emily), discuss the “new political climate” (ring any bells, 2018 progressives?). He advises her against teaching in the coming semester, and she incisively infers that he is “hiding the dykes” due to political pressure. Then, he echoes a sentiment many older LGBTQ people have been sharing lately in 2018, that he never thought that he would see the next generation going back into the closet. In response, Emily informs him that she absolutely will be teaching next semester and won’t be going back into the closet. He sardonically replies, “welcome to the fight, it sucks.” (In the last few years, THIS queer WOC has had the same conversation with mentors and older professionals – luckily, my peers and I ARE here for the fight…. because the truth is that it was never over anyway.)

Given this country’s most recent family separation policies, it is particularly poignant for the viewer to watch Emily being separated from her family. When she and her wife attempt to cross the border with their son, she produces their marriage license, and she is told that the document is no longer recognized. She is told that it is not valid, and they are not married, because it is forbidden by the law. Emily asks the border police (Gilead’s ICE?) what law forbids it, and when the customs agent will not clarify, it is clear to us (the viewers) and to Emily that he is referring to the BIBLICAL law, which obviously has no place in the state’s legal system. Unironically, just last week in the US, Attorney General Jeff Sessions used the bible as justification for the separation of immigrant parents and child at the US-Mexico border, and the White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders supported this stance.

This Handmaid’s Tale episode was written well before some of this country’s highest public officials would use the Bible as justification for splitting up immigrant families, and its portrayal of this recent reality seems almost prescient. We are currently living in a time when the most incisive satire is, sadly and truthfully, easily trumped by reality (pun intended). Also, just a quick aside, when Sarah Huckabee Sanders verbally supported Jeff Sessions’ decision to quote Romans 13 as justification for separating families at the border, Playboy White House Correspondent Brian Karem implored her to show some empathy, at least in terms of her identity as a mother – that’s right, we now live in a world in which cis/het/male reporters from PLAYBOY have more empathy for families who are separated at the border while seeking asylum than women who work at the White House have.

One of Emily’s last actions in this episode is to administer some pills that she labels as “antibiotics” to a mistress (wife) who appears in the colonies because her husband had an affair. Emily administers this medication in her role as a caretaker who attempts to grant humanity to her fellow unwomen in the colonies. We, the viewers, momentarily think she must have an endless reservoir of kindness, particularly as she justifies the gesture with the comment, “a mistress was kind to me once.” However, later that same day, when Emily goes to check on the sick new unwoman, we realize that we have been fooled, just as the former mistress has – the pills Emily gave her were actually poison, not antibiotics. As the shocked former-wife lies dying, and the shocked viewer watches, Emily says to her, bitterly, “Every month, you held a woman down while your husband raped her. Some things can’t be forgiven.” Then, Emily tells the wife that “she should die alone,” and walks away. Emily’s brutal response to a former wife’s appearance in the colonies is a response to a brutal world – she responds violently to a world that has treated her violently, and this action seems to echo Zora Neale Hurston’s sentiment, “If you’re silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it” – Emily did NOT enjoy her pain, and she wants people to know it.

Also, just some asides about June’s storyline in this episode: June’s narrative in Episode 2 is less character-driven and more expository, giving the viewers insight into the history of how Gilead rose to power. As she continues to hide from the Gilead’s police force, June and the viewer come to learn that she is hiding out in the former offices of the Boston Herald, one of the oldest US newspapers, winner of eight Pulitzer prizes. We also come to realize that Gilead’s armed forces slaughtered all the newspaper’s staff, as part of their efforts to control the press and take control of the government. Additionally, when Nick comes to visit June, we see her frustration as she appreciates just how trapped she really is – even when he gives her keys to a car and the means of escape, she knows she’d never be able to make it out of Gilead alive, and screams in anger as realizes that no keys, no gun, nothing can save her from this system that’s designed to use her as breeding stock, keep her separated from her child, and kill her. Then, realizing that she has absolutely no agency in this social structure, June chooses to assert her agency in the only space where she is able to assert her personhood – in her physical relationship with Nick. In this context where June literally has no other outlets, her choice to have sex with Nick is a transgressive act, as she uses her body for her own pleasure, to distract herself from her own fear and pain, and to dominate the man she has access to.

0 notes