#atta cephalotes

Text

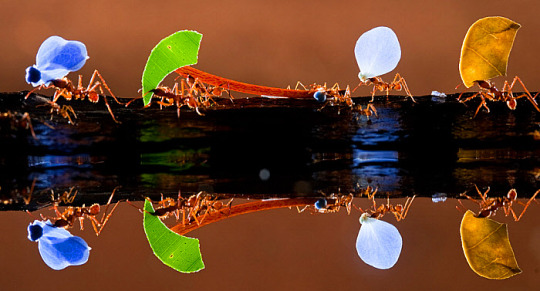

Leaf cutter ants (Atta cephalotes)

Photos by Bence Mate

#Atta cephalotes#atta#leaf cutter ants#ants#hymenoptera#formicidae#formicoidea#insects#entomology#ant photography#insect photography#nature

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

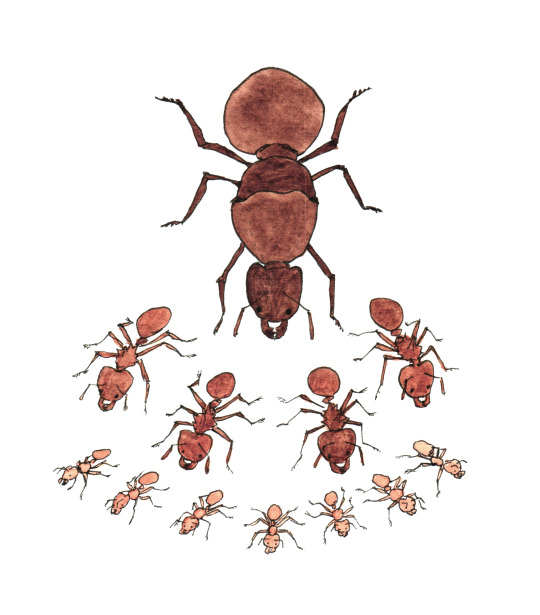

Atta cephalotes is a species of leafcutter ant in the tribe Attini (the fungus-growing ants) which is widely distributed throughout North, Central, and South America from as far north as Mexico to as far south as Bolivia. Here they tend to inhabit tropical rainforests, cloud forests, and mixed mosaics spending the bulk of there time in the understory and on the forest. Although leafcutter ants are famous for there cutting and gathering of leaves as well as other plant material such as seeds, flowers, vines, fruit and even occasionally fecal matter and dead invertebrates, they actually don’t eat these substances regularly, instead they use this organic matter to nourish and cultivate expansive fungi farms which provide the majority of the colonies nutrition. These are colonial insects with complex division of labor. A single long-lived queen (up to 20 years) and millions of sterile workers live together in an enormous underground nest which can be up to 100 square meters. Workers cut and carry leaf fragments, clean and mulch leaves, tend symbiotic fungus gardens, care for queen and many larvae/pupae, and defend the nest, together with soldiers. Newly hatched workers perform tasks inside the nest (some outside, e.g., trail clearing), with older workers mainly active outside the nest. Leafcutter ants are eaten by a wide variety of predators including many birds, bats, frogs, toads, lizards, ground mammals, and invertebrates including other ants such as army and fire ants.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leafcutter ant (Atta cephalotes). The Entomologist's Text Book. Written and illustrated by John Obadiah Westwood. 1838.

Internet Archive

247 notes

·

View notes

Note

so like. how does it work practicing a religion that in part revolves around a river 12,000 km from you

For a moment I thought you meant the Ganghes and I wondered if you were conflating Hinduism with Buddhism because that's what nowadays forms the majority of my practice. But I think you mean me being Kemetic and the river you mean is the Nile.

Truth be told there is no consensus and to some extent the whole community is experimenting with it! Comes with the territory of reconstructing a religion from archaeological evidence.

As a bit of a case study why don't we take Wep Ronpet, Egyptian New Year. The theme of the holiday in antiquity was the beginning of the flood season which renewed the fertility of the Nile valley, equated to Zep Tepi, the primordial time of creation. Among modern Kemetics it has a meaning similar to the secular New Year: out with all the negativity and chaos of the year past, in with the new.

Opinions differ as to exactly when to celebrate Wep Ronpet. The event commemorated simply does not happen anymore. Since the construction of the Aswan Dam in 1960-1970 the Nile does not flood annually, so that cannot be the benchmark.

Some Kemetics mark it with a fixed date, usually around northern hemisphere summer to coincide with the ancient date. Agust 15th (September 11th in the Julian calendar) to coincide with the Coptic Orthodox Church's Feast of the Martyrs, the direct modern descendant holiday of Wep Ronpet still celebrated in Egypt, or July 18th for the date during the New Kingdom period.

Other Kemetics may celebrate it based on their own region's agricultural calendar. If I was doing it like this here in Guatemala I could perhaps do it around May or June which is the time of year when rainfall first spikes and the famous zompopos the mayo (a type of leafcutter ant that thrives in humidity, scientific name Atta cephalotes) begin to come out.

Finally, and most popularly, many kemetics base it around the date of the heliacal rising of sirius, a once-yearly astronomical event that used to coincide fairly close to the flooding of the Nile and was as such used in antiquity to estimate the date. Since the exact date of the heliacal rising varies depending on where on the globe you are opinions differ as to what to base the calculations off of. Members of The House of Netjer base it off their main temple in Illinois where former Nisut (pharaoh) Dr. Tamara L. Siuda resides. Others base it off the date in Egypt itself. And yet others base it off their own location.

I personally am partial to August 15th for entirely personal and practical reasons. I live in Guatemala City, August 15th is a public holiday because the patron saint of the city is The Virgin of the Assumption. So The Feast of the Assumption of the Holy Virgin Mary on August 15th, both a pan-Catholic holiday and specifically a local holiday I get a day off for is fitting I think. A very specific rejection and recontextualization of the religion I was raised with.

And that's what practicing a reconstructed religion comes down to, I believe. Weaving together the threads of history, archaeology, and anthropology to forge your own relationship with the cultural and spiritual practices that speak to you from these ancient cultures.

#kemetic#kemeticism#religion#by the way while I do not mind answering these at all#I'd much rather redirect them to my main (@aerial-jace) for when it does not intersect with WC or my fics kay?

9 notes

·

View notes

Audio

I just found this and I need to share it. Kuai Shen built an electric circuit to listen to and amplify the sounds leaf-cutter ants make to communicate. He then made an album you can buy which includes access to instructions to build your own piezoelectric amplifier to listen to any acoustic vibrations. Kuai even wrote down the biological process and anatomy behind it. He sees a kinship between ants and humans and now so do I. Just listen...

Stridulation Amplified: compositions with the stridulatory organ of Atta cephalotes by Kuai Shen

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

BIG HEAD ATTA CEPHALOTES!!! WITH BERRY TOO BIG FOR HER!!!!!!!

i love her shes doing her best

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

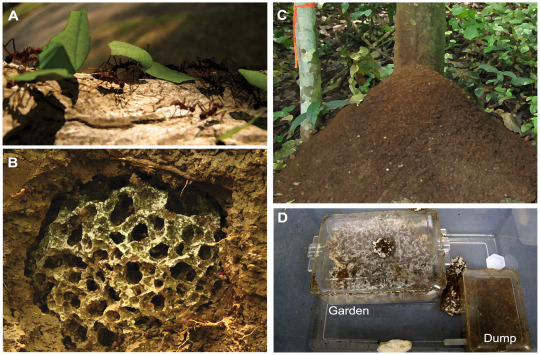

Leafcutter ant (Atta cephalotes)

Burgers’ Zoo, Arnhem

Leafcutter ants are the farmers of the insect world! They cut pieces of leaves and flowers and carry them back to their colony. There, the leaves are chewed into a paste which is the perfect breeding ground for a special fungus; the leafcutter ants’ food source!

0 notes

Photo

Gigantiops destructor

PHOTOGRAPHS BY EDUARD FLORIN NIGA

Diacamma rugosum, Saharan silver ant

Gnamptogenys bicolor, Leaf-cutter ant (Atta cephalotes)

Maricopa harvester ant, Polyrhachis beccarii worker ant

Giant turtle ant (Cephalotes atratus)

#eduard florin niga#photographer#national geographic#gigantiops destructor ant#ant#nature#macro photography#diacamma rugosum#saharan silver ant#gnamptogenys bicolor#leaf-cutter ant#atta cephalotes#maricopa harvester ant#polyrhachis beccarii#giant turtle ant#cephalotes atratus

232 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Leafcutter ants (Atta cephalotes) dismembering an intruding bullet ant (Paraponera clavata) in Limón, Costa Rica

Chien C. Lee

76 notes

·

View notes

Video

LEAFCUTTER ANTS

Atta cephalotes

©Laura Quick

Atta cephalotes is a species of leafcutter ant in the tribe Attini. A single colony of ants can contain up to 5 million members, and each colony has one queen that can live more than 15 years.

They live in nests that can be as deep as 7 meters that they have carefully positioned so that a breeze can rid the nest of the dangerous levels of CO2 given off by the fungus they farm and eat.

Ant–fungus mutualism is a symbiosis seen in certain ant and fungal species, in which ants actively cultivate fungus much like humans farm crops as a food source. In some species, the ants and fungi are dependent on each other for survival. The leafcutter ant is a well-known example of this symbiosis.

Of note: A special caste of workers manage the colony's rubbish dump. These ants are excluded from the rest of the colony. If any wander outside the dump, the other ants will kill them or force them back. Rubbish workers are often contaminated with disease and toxins, and live only half as long as their peers.

Other posts:

Very good overview post of leafcutter process

Older leafcutters - go from cutting to carrying

Leafcutter - Close-up precision cutting

source

#leafcutter#leafcutter ants#atta cephalotes#©laura quick#costa rica#la selva biological station#puerto viejo de sarapiquí#fascinating#earthwatch.org#travel photography#fungus farmers#trash workers#ant fungus mutualism#symbiosis

11 notes

·

View notes

Video

Video: Leafcutter Ant, Atta cephalotes by Andreas Kay

Via Flickr:

youtu.be/iJfck3zisI0 from Ecuador

#Andreas Kay#ant#Atta cephalotes#Ecuador#Flickr#focus stack#Formicidae#Hymenoptera#leafcutter#soldier

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Animals! 3

1. Electric Eel

2. Flamboyant Flower Beetle

3. American Lobster

4. Atta Cephalotes

0 notes

Link

See these, and you will never look at an ant the same way again. From National Geographic. All photos by Eduard Florin Niga.

At left, the diacamma rugosum, native to Borneo, is one of the only ant species to lack a queen caste. Instead, workers compete in long tournaments to determine who will be allowed to lay eggs. At right: The Saharan silver ant is one of the fastest ants in the world; it can move its small body nearly three feet in one second.

At left, Gnamptogenys bicolor, found in China and nearby countries, has iridescent pockmarks on its head that may help serve as a form of camouflage. Right: This a leaf-cutter ant, Atta cephalotes, that farms fungus in underground chambers.

At left, a Maricopa harvester ant, found abundantly in Arizona and nearby states. These ants have a potent venom, stronger than that of honeybees, which can cause intense pain. Right: A Polyrhachis beccarii worker, native to Southeast Asia, covered in golden hairs.

Above, the giant turtle ant, Cephalotes atratus, is sometimes called “the Darth Vader of the ant world.” Its flat, broad head helps it glide between treetops in South American rainforests. Read more about this wondrous microworld here.

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Leafcutter Ants

Atta cephalotes

Atta texana

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 9 - Atta cephalotes (leafcutter ant)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

These ants suit up in a protective 'biomineral armor' never seen before in insects

https://sciencespies.com/nature/these-ants-suit-up-in-a-protective-biomineral-armor-never-seen-before-in-insects/

These ants suit up in a protective 'biomineral armor' never seen before in insects

Ants are pretty organised little creatures. Highly social insects, they know how to forage, build complicated nests, steal your pantry snacks, and generally look after the queens and the colony, all by working together.

Leaf-cutter ants turn that cooperation up several notches. Leaf-cutter ant colonies like Acromyrmex echinatior can contain millions of ants, split into four castes that all have different roles to maintain a garden of fungus that the ants eat.

These farming ants might make a top-tier team of gardeners, but that doesn’t mean they don’t get into the occasional scrap, and living in such large groups usually also means facing an increased risk of pathogens.

For these reasons, a little protection never goes astray, and although scientists aren’t entirely sure why, it seems these little guys needed protection enough to evolve their own natural body armour.

A team led by researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison analysed this ‘whitish granular coating’ on A. echinatior and came to the conclusion that the coating is a self-made biomineral body armour – the first known example in the insect world.

“We have been working on these leaf-cutting ants for many years, especially focusing on this fascinating association they have with bacteria that produce antibiotics that help them deal with diseases,” senior author and University of Wisconsin-Madison microbiologist Cameron Currie told ScienceAlert.

“It was in our effort to identify what the ant might produce for the bacteria that [first author Li] Hongjie discovered the biomineral crystals on the surface of the ant.”

The team peered deep onto the mineral layer that covers the ant’s exoskeleton, using electron microscopy, electron backscatter diffraction, and a number of other techniques. They found the coating is made up of a thin layer of rhombohedral magnesium calcite crystals around 3-5 micrometres in size.

Top: the shiny armour. Bottom: SEM image of the coating. (Li et al., Nature Communications, 2020)

You might be more familiar with biomineral skeletons in crustaceans such as the hard shells of lobsters. However, insects evolved from crustaceans, so it makes sense that some may have retained a similar armour-like trait.

The team also reared the ants to see when this coating occurred, and how it protects them – finding that the coating is not present in baby ants, but develops rapidly as the ants mature, and that this finished coating significantly hardens the exoskeleton.

To confirm this, the researchers put the ants into experimental battles, finding that those with the armour were more protected in battle, and also from pathogens.

“To further test the role of the biomineral as protective armour, we exposed Acromyrmex echinatior major workers with and without biomineral armour to Atta cephalotes soldiers in ant aggression experiments designed to mimic territorial ‘ant wars’ that are a relatively common occurrence in nature,” the team write.

“In direct combat with the substantially larger and stronger At. cephalotes soldier workers, ants with biomineralised cuticles lost significantly fewer body parts and had significantly higher survival rates compared to biomineral-free ants.”

They also discovered that without the armour, the ants were significantly more likely to be infected with an insect attacking fungus called Metarhizium anisopliae.

Although we don’t understand how this leaf-cutter ant species evolved this coating, the team thinks that it’s probably not the only insect that developed such a protection.

“Given that fungus-growing ants are among the most extensively studied tropical insects,” the team writes, “our finding raises the intriguing possibility that high-magnesium calcite biomineralisation may be more widespread in insects than previously suspected, suggesting a promising avenue for future research.”

While there might be a number of species of ants that have a similar coating, with more research the ‘armour’ technology could even make the leap to humans – or at least our stuff.

“We think that there is potential for development of the material as adding strength to a range of products. It is light and thin,” Currie told ScienceAlert.

“The field of material science is an exciting area of science.”

The research has been published in Nature Communications.

#Nature

2 notes

·

View notes