#but i think there's a balance of awareness and nuance that very few people/players have been able to hit

Text

anyways. andy roddick everybody

Transcription:

[A: As you're saying the devil's in the details and homosexuality is illegal, but we have openly gay players. Uh...[Daria] Kasatkina, came out last year, now, if she goes there and play[s], are we just telling her to take a week off of her sexuality? I mean how do we even...how do we protect our own players who are, you know their—their life choices are viewed as criminal, when they enter this place? It's like, how do we protect those mechanisms, and, can whatever is said now be trusted when it's actually in practice?]

#there's a lot more to be said about this and actually i think the whole section where they talk about this is pretty good overall#better at least than some of what i've seen from other folks#but this part in particular i was grateful that someone said out loud#andy roddick#wta tennis#the whole saudi issue is complicated to me for a lot of reasons#i don't want to get into it too much because i think it's such a long conversation#but i think there's a balance of awareness and nuance that very few people/players have been able to hit#anyways.#maybe one day i'll talk about it in full

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Superman & Lois Pilot Script Review

I’ve been reliably informed that absence makes the heart grow fonder, and indeed as my laptop and everything on it have been unusable for a couple months after a mishap, I went from ‘maybe I’ll write something on the pilot script for Superman & Lois’ to ‘as soon as I can get my hands back on that thing I’m writing something up’. I’m actually surprised none of you folks asked about it when I’ve mentioned several times that I read it; I was initially hesitant, but I’ve seen folks discussing plot details on Twitter and their reactions on here, so I guess WB isn’t making much of a thing out of it. Entire pilots have leaked before and they just rolled with it, so I suppose that isn’t surprising. Anyway, the show’s been pushed back to next year, and also the world is literally sick and metaphorically (and also a little literally) on fire, so I thought this might be fun if anyone needs a break from abject horror.

(Speaking of the world being on fire: while trying to offer a diversion amidst said blaze, still gonna pause for the moment to add to the chorus that if opening your wallet is a thing you can do, now most especially is a time to do it. I chipped in myself to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and even a casual look around here or Twitter will show people listing plenty of other organizations that need support.)

What I saw floating around was, if not a first draft, certainly not the final one given Elizabeth Tulloch later shared a photo of the cover for the final script crediting Lee Toland Krieger as the director rather than a TBD, but the shape of things is clearly in place. I’m going for a relative minimum of spoilers, though I’ll discuss a bit of the basic status quo the show sets up and vaguely touch on a few plot points, but if you want a simple response without risk of any story details: it’s very, very good. Clunky in the way the CW DC shows typically are, and some aspects I’m not going to be able to judge until the story plays out further, but it’s engaging, satisfying, and moreover feels like it Gets It more broadly than any other mass-media Superman adaptation to date.

The Good

* The big one, the pillar on which all else rests: this understands Lois and it really understands Clark. Lois isn’t at the center of the pilot’s arc, but she’s everything you want to see that character be - incisive, caring, and refusing to operate at less than 110% intensity with whatever she’s dealing with at any given time, the objections of others be damned. Clark meanwhile is a good-natured, good-humored dude who you can see in both the cape and the glasses even as those identities remain distinct, who’s still wrestling with his feelings of alienation and duty and how those now reflect his relationships with his children. The title characters both feel fully-formed and true to what historically tends to work best with them from day one here in ways I can’t especially say for any other movie or show they’ve starred in.

* While the suit takes a back seat for this particular episode, when Superman does show up in the opening and climax it absolutely knows how to get us to cheer for him; there’s more than one ‘hell yeah, it’s SUPERMAN, that guy’s the best!’ moment, and they pop.

* While the superheroics aren’t the biggest focus here, when they do arrive, the plan seems to be that they’ll be operating on an entirely different scale than the rest of the Arrowverse lineup. Maybe they scripted the ideal and’ll be pared-down come time for actual filming and effects work, or maybe they’re going all-out for the pilot, but the initial vision involves a massive super-rescue and a widescreen brawl that goes way, way bigger in scope than any I’m aware of on the likes of Supergirl. I heard in passing on Twitter from someone claiming to be in the know that the plan for Superman & Lois is that it’ll be fewer episodes with a higher budget, more in line with the DC Universe stuff if not exactly HBO Max ‘prestige TV’, and whether it’s true or not (I think it’s plausible, the potential ratings here are exponentially higher than anything else on the network so they’d want to put their best foot forward) they seem to be writing it as if that’s the idea.

* This balances its tones and ambitions excellently: it’s a Kent-Lane family drama, it’s Lois digging in with some investigative reporting to set up a major subplot, it’s Superman saving Metropolis and battling a powerful high-concept villain, and none of it feels like it’s banging up at awkward angles with the rest. There are a pair of throwaway lines in here so grim I can’t believe they were put in a script for a Superman TV show even if they don’t make it to air, and they in no way undermine the exhilaration once he puts on the cape or the warmth that pervades much of it. This feels as if it’s laying the groundwork for a Superman show that can tackle just about any sort of story with the character rather than planing its feet in one corner and declaring a niche, and so far it looks like it has the juice to pull it off.

* While the pilot doesn’t focus on him in the same way as the new kid, Jonathan Kent fits well enough for my tastes with the broad strokes of his personality from the comics, albeit if he had made it to 14 rather than 10 without learning about his dad being Superman. A pleasant, kinda dopey, well-meaning Superman Jr. - the biggest deviation, one I approve of, is that he can also kinda be a gleeful little shit when dealing with his brother in ways that remind you that this is very much also Lois Lane’s boy.

* We don’t know much about the season villain as of yet, but it’s an incredibly cool idea that I’m shocked that they’re going for right away, and I absolutely want to see how they play out as a character and how they’ll bounce off all the other major players.

* The way this seems to be framing itself in relation to the Superman movies and shows before it feels inspired to me: there are homages and shout-outs to and bits of conceptual scaffolding from Lois & Clark, Smallville, Donner, and more, but they’re all shown in ways that make it clear that those stories are part of his past rather than indicators of the baseline he’s currently operating off of. We get a retrospective of his and Lois’s history right off the bat with most of what you’d expect, and combined with those references the message is clear: this is a Superman who’s been through all the vague memories that you, prospective casual viewer, have of the other stuff you saw him in once upon a time, but this series begins the next phase of his life after what that general cultural impression of him to date covers. It strikes me as a good way of carrying over the goodwill of that nostalgia and iconography, while building in that this is a show with room to grow him beyond that into something more nuanced (and for that matter true to the character as the comics at their best have depicted him) than they tended towards. Where Superman Returns attempted to recapture the lightning in a bottle of an earlier vision of him in full, and Man of Steel tried to turn its back on anything that smelled of Old and Busted and Uncool entirely, perhaps this splitting of the difference - engaging with his pop culture history and visibly taking what appealed from some of those well-known takes, while also drawing a clear line in the sand between those as the past and this as the future - is what will finally engage audiences.

The Bad

* This is the sort of thing you have to roll with for a CW superhero show, and that lives and dies by the performances, but: the dialogue varies heavily. There are some really poignant moments, but elsewhere this is where it shows its early-draftiness; a decent amount is typical Whedon-poisoned quippiness or achingly blunt, and some of the ‘hey, we’re down with the kids!’ material for Jon, Jor, and Lana’s kid Sarah is outright agonizing. I suspect a lot of it will be fixed in minor edits, actor delivery, and hopefully the younger performers taking a brutal red pen to some of their material - this was written last January and the show’s now not debuting until next January, they’ve got plenty of time for cleanup - but if this sort of the thing has been a barrier to entry for you in the past with the likes of The Flash, this probably won’t be what changes your mind.

* There are a few charming shout-outs to other shows, but much moreso, Superman & Lois actually builds in a big way out of Crisis. Which is a-okay with me, except that what exactly that was is rather poorly conveyed given that lots of people will be giving this a spin with no familiarity with that. Fixable with a line or two, but important enough to be worth noting.

Have to wait and see how it plays out

* The series’ new kid, Jordan Kent, is so far promising with potential to veer badly off-course. He’s explicitly dealing with mental illness, and not on great terms with Clark at the beginning in spite of the latter’s best efforts, the notion of which I’m sure will immediately put some off. Ultimately the commonalities between father and son become clear, and he’s not written as a caricature in this opening but as a kid with some problems who’s still visibly his parents’ boy, but obviously the ball could be fumbled here in the long term.

* Lois’s dad is portrayed almost completely differently here than in the past in spite of technically still being her military dad who has some disagreements with her husband. There are some nice moments and interesting new angles but it seems possible that the groudwork is being laid for him to be Clark’s guy in the chair, and not only does he not need that he most DEFINITELY doesn’t need that to be a member of the U.S. Military, especially when one of the first and best decisions Supergirl made when introducing him was to make clear he had stopped working with the government any more than necessary years ago. Maybe it can be stretched if his dad-in-law occasionally calls him up to let him know about a new threat he’s learned about, and maybe they’ll even do something really interesting with that push-and-pull, but if Superman’s going to be even tacitly functioning as an extension of the military that’s going to be a foundational sin.

* As I was nervous about, Superman & Lois has some political flavor, but much to my delighted surprise, there’s no grossly out of touch hedge-betting in the way I understand Supergirl has gone for at times. As of the pilot, this is an explicitly leftie show, with the overarching threat of the season as established for Lois and Clark as reporters being how corporate America has stripmined towns like Smallville and manipulated blue collar workers into selling out their own best interests. Could that go wrong? Totally, there’s already an effort to establish a particular prominent right-wing asshole as capable of decency - without as of yet downplaying that he’s a genuinely shitty dude - and vague hints that some of the towns’ woes might be rooted more in Superman-type problems than Lois and Clark problems. But that they’re going for it this directly in the first place leaves me hopeful that the show won’t completely chicken out even if there’ll probably be a monster in the mix pulling a string or two; Greg Pak and Aaron Kuder’s Action Comics may justify Superman punching a cop by having him turn out to be a shadow monster so as to get past editorial, but it’s still a story about how sometimes Superman’s gotta punch a cop, and hopefully this can carry on in that spirit of using what wiggle room it has to the best of its ability.

So, so far so good. Could it end up a show with severe problems carried on the backs of Hoechlin and Tulloch’s performances? Absolutely. But thus far, the ingredients are there for all its potential problems to be either fixed, subverted, or dodged alright, and even when it surely fumbles the ball at junctures, I earnestly believe this is setting itself up to be the most fleshed-out, nuanced, engaging live-action take on these characters to date. And god willing, if so, the first real stepping stone in decades to proper rehab on Superman’s image and place in pop culture.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I've been thinking alot ab mythological roles. In comic, theyr asigned to characters to represent their intended growth and who theyr suposed to become in the alpha timeline, and this is known due to the nature of paradox space and time shenanigans. So when we try to claspect ourselves, what are we suposed to base it on? We cant know who we will become, and atitle that represents all of ourself just isnt posible. Everyone has diferent tests but no one seems to be asking that question directly

The point of a Classpect is to challenge you. It’s supposed to be difficult. It’s supposed to push you. You’re not meant to go into a Classpect and find it easy peasy; there’s always some form of difficulty, some block, that you have to overcome. So, I think, the first way you can help figure out your Classpect; if it sounds too easy, if it sounds like that form of growth would be a sinch for you - it’s wrong.

Classpects challenge you in order to make you the very best you you can be. It’s somewhere between the Ideal Self and the Perfect/Ultimate Self (though very much not the way Dirk explains or understands it). There is a specific path you can go down, a series of awarenesses that you can uncover, that help you realise who you’re really meant to be. So, some of Classpecting is also just trying to think ahead to who YOU want to be, but also what you think the BEST you could look like.

There’s no 100% quickfire way to figure that out - because, you’re right, we’ve got no idea who we’re going to become, and thinking about our ideal/best selves isn’t exactly easy - but you can do it through a lot of self reflection. Figuring out what your flaws are, where you struggle as a person, what your strengths are; they can all be used to figure out what you at your absolute best would be. You can then reference that against the various Classpects, and especially how people analyse them - because a lot of us do include what the struggle point for any given Classpect would be; that thing you have to overcome - and see if that struggle would actually be difficult for you. Would that challenge make you rise up as a person? Would it benefit you?

You can also base it on what you already know about yourself and your current personal journey. You’ve been growing since you were a kid, changing who you are in little ways, being affected by different things; Classpects take into account all of this.

I very much subscribe to the theory that Classpects affect your homelife and your upbringing. Your Classpect comes first - even before you’re born, your Classpect is there as an inevitable sort of thing. It details exactly what path you’ll go down as a person, be it to become a True, Realised, or Failed Player. You can pretty much always track these paths and the similarities between Players via joint experiences and joint struggles.

This is the sort of thing we detail, too - or at least that I try to include in my analyses. This is what a Player will look like before their awareness; this is what a Player is likely to act like and struggle with. This is probably the easiest way to help figure out your Classpect, so long as you’re comfortable with the idea of self reflection; looking back over your life and seeing if it lines up with the explanation of a Classpect pre-awareness.

To take myself as an example? I’m a Page of Heart. I know this because, throughout my life, I have had significant struggles with Heart (self identity, impulsivity, relationships), and I had a definite lack of it at one point in time (ending up doing a lot of the “trying to act caring/empathetic but often being overemotional” and “being passionate to the point of obsession” stuff). And I know for a fact that, still, in my attempts to be kind and caring, I can be... very overprotective and a little suffocating.

On top of that? I’ve definitely been exploited via my emotions and empathy (something I only realised more recently through Classpect-based self reflection), and I have a tendecy to overshare with people who aren’t technically close enough for it. I know for a fact, too, that my emotions can get wildly out of hand.

Therefore, a lot of my growth is about learning Heart until it becomes natural, and about an eventual sense of balance between the lack and the extreme. I already know I’m getting there. I’m getting much better at connecting to people emotionally, and I’ve got a knack these days for figuring out peoples’ identities (which can be something as small as guessing their favourite animal/colour first try and as large as working them through their Classpect journey).

I know this is my Classpect because it fits not only what I’ve been through, what I know I’m going to struggle with, and the concept that it’s actively going to challenge me, but also because it hits this note of who I see and want my ideal self to be.

This is why tests are great, but don’t always hit the mark. I’ve been asked a few times to make a test of my own, and as much as I’d love the idea and have put some thought towards it, a lot of Classpecting is self reflection and thought. It could help to narrow down the potentials, but it would never be perfect - especially since there are some Classpects (such as the destructive or lacking ones) that might appear on the surface as a completely different Classpect. I’m not sure how to accurately make a test that takes into account these little nuances.

So! For a TL;DR:

We can still understand Classpects the same way they’re used in Homestuck, and I think in a way it’s better to view them like that. Your Classpect defines you, is you, and therefore you can use what you know about yourself, your struggles, and your best self to figure out which Classpect best aligns with you. If it seems like it’d challenge you, if it hits a lot of notes for things you’ve been through, and if you think your ideal self is what the Classpect’s end product is? Chances are, that’s your Classpect - and has been all along.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Designing BattleTabs

Hey! I’m Tom, game designer for BattleTabs!

The design for Battletabs originated from Battleship, a fairly well known board game. One of the most interesting parts of the design process has been analysing the game to find how it ticks, and pushing it in a direction that suited our goals. I thought I’d take this opportunity to share how that process went down!

When I joined the team in January the gameplay for Battletabs was just about the same as Battleships. The goal was to rework the design so that the game would have longer appeal, could be updated to stay fresh, and simply to make it more fun!

The current version of BattleTabs!

Analysis

The first thing was to break down what made Battleships fun! I played lots of different versions of Battleships and noticed a few things:

Things I liked:

The most interesting part of Battleships is when you’ve got a grid with some hits and misses and know the shapes of the enemy ships. From that information can deduce several potential positions for the enemy, which you can whittle down further with strategic play.

Some games added “combo” mechanic that I don’t believe exists in the classic game where on hitting the opponent you could play again. I quite liked this, since it meant you had a chance to take out a whole ship at once, giving a losing player a sense that they could always catch up if they had a bit of luck without feeling overpowered.

One of the advantages of Battleship is that it’s something of a folk game - most people have played it or are at least vaguely familiar with the rules (although as it turned out, not as many as I had guessed!). We could expand on the base design, but wanted to make sure it still felt like Battleships.

Most the Battleships games (especially commercial ones) I could find were identical or minor variations on the original design, which suggested there was an opportunity to expand on it to create something unique!

Things I didn’t like:

The early game isn’t very interesting. Until you’ve got some information on the board, the optimal strategy is pretty much to just take random guesses! (This is something that we’re keenly aware could be improved in the current design!)

Too much randomness! While luck is exciting, the sense (even when it’s a delusion!) that your skill at the game matters is important for a game to feel competitive and keep players happy.

Most turns are misses. In classic Battleship, the hit/miss ratio is about 0.33, and because misses don’t give the player much information the typical turn is quite unsatisfying. Obviously the player can’t hit every turn, so I was keen to find ways to make misses a little more rewarding.

Games are too similar! Although each game plays differently, opponents rarely played in dramatically different styles and the board and ship shapes are always the same.

A few versions gave special abilities to each ship, which I liked in principle but I found that in all cases they were massively overpowered and caused games to rarely last more than a few turns. In many cases the best abilities were earned by playing ads or spending money, which caused games to often feel nakedly unfair.

Update #1: “Sonar”

From this analysis I put together a list of ways we might improve the game

More interesting ship shapes would make finding spaces that might contain ships more nuanced

For similar reasons, maps could contain obstacles

A “Minesweeper” system where misses revealed the distance to the closest enemy ship would give the player more information from a miss, and also fed into the “find possible spaces for ships” gameplay

Ships with special abilities, where use of the abilities is restricted to prevent players using the same ship every turn and to prevent games devolving into blitzkriegs. Eventually we settled on a cooldown system, which can be balanced easily and provide a nice reward momentum in turn based games.

We considered lots of other ideas too, like increasing the number of ships, adding a wager system where players could bet on the likelihood of a tile containing an opponent, only allowing players to play adjacent to tiles they’d already hit, and a puzzle mode - some were discarded, others set aside for future updates!

We were keen to start improving the game immediately and incrementally, so we focused first on the “Minesweeper” concept, which solved a good number of my issues with traditional Battleships at once.

Me and Brandon tested it on paper and were pleasantly surprised to find that for once, the theory neatly panned out in reality!

Mike implemented this design and put it live not long afterwards.

Some of the many, many scraps of paper used for playtesting!

Update #2: “Fleets”

At the same time, we were thinking about ways to give the game more lasting appeal. The keys were progression, depth, and community. We wanted to build a meta-game that enabled us to reward play with valuable in game commodities, and encourage players to form stronger social bonds.

Factions

One of the ideas considered was a “factions” system (common to a few multiplayer games, including Pokemon Go), where players of a faction could lay claims to territory on a world map by winning games. We eventually decided that such an expensive system might be too risky while the game still had a relatively low playerbase.

Ships and Fleets

The idea that eventually stuck was to expand on the “special abilities” concept we’d considered previously. The idea was that players could collect new ships by winning games, and use them to create their own fleets that helped them to gain an edge over their opponents. A levelling system would be employed to provide an extra reward and help matchmake players of similar skill and fleet power.

We prototyped the concept as we had before - this time with the pandemic preventing real-life meetups, over Skype. We were pleasantly surprised how many interesting abilities we were able to think up, although to ensure we could implement and test the changes relatively quickly we decided to start with 4 predefined fleets with relatively basic ships, with the ships/XP economy as a future update.

Designing the 4 fleets

The goals for the 4 fleets we wanted to launch with were clear:

Reasonably low implementation complexity

Each fleet should have a clear and distinct role

Ships and fleets should attempt to resolve the flaws in the core Battleships design

Playtesting

Playtests went well, clearly increasing the variety and nuance of interesting situations, and making decisions over which ships to attack more interesting. One of the big advantages of the system was how easily tunable it was - if something was overpowered we could change the effectiveness of the ability, or if that wasn’t so easily possible, the cooldown.

Ship size

Something that did surprise us was how unclear the effectiveness of physically larger ships was. On one hand larger ships were easier to find, but on the other they took longer to destroy. Smaller ships only really seemed more subject to randomness, rather than “better” or “worse”, with a lucky player destroying them in one hit, but an unlucky player unable to find them.

Increasing complexity

The biggest downside was the added complexity - players would now need to read the descriptions for each ship to understand how they functioned, and select a ship each time they wanted to use an ability - low complexity relative to most competitive games, but a large step up for us. Ultimately we decided that added complexity was necessary to increase depth, and it seems likely that any solution that increased depth would have the same issue.

A new role for Sonar

In one way this update was a step back - the “sonar” update was popular and I was incredibly happy at how elegantly it resolved the “lack of skill” problem. It was an effective enough ability that we briefly considered keeping it as the default (with no ship selected) attack, but eventually decided to make it an ability in itself. As a rule of thumb, I still believe that fleets should always have one ship with some form of sonar, or at least some form of vision ability such as the new “reveal” ability, which is less interesting but also less powerful making it a useful tool for some ships!

Looking to the future!

The fleets update launched two weeks ago, and so far it’s been a success! We’ve been improving social aspects, allowing players to add friends, use emoji and invite rematches.

In the near term we’re looking at some minor design tweaks and contemplating a few new fleets, and in the longer term you can look forward to special events, progression systems, and more ships and fleets! To stay up to date, the Discord channel is the best place to get the latest news!

Thanks for reading!

Tom

0 notes

Text

The Mundane Fantasy: Persona 5's Appeal To Adults

I have a hard time figuring out who Persona 5 was made for exactly. The game, like all Persona games, is focused around misfit high school students who uncover dark secrets about the world and people (especially adults) around them. In this particular case, you are tasked with changing the hearts of adults who would do harm to others by invading their subconscious and kicking the crap out of their evil selves. You manage to put a stop to a teacher who subjects students to abuse and sexual harassment, reform a gangster, among others. The outright criminal nature of the game’s biggest problems are interestingly folded in with the smaller associated problems that go along with them. Teammates on the track team turn on each other, for instance, in order to spare themselves the wrath of their coach. Gossip is spread about some of the female characters out of jealousy and insecurity. At twice the age of an average high school student, it feels quite wrong that I can get sucked into the drama of youths the way I do. It isn’t even the overarching sinister plot points that have me so enthralled. The more power fantasy elements, such as donning a mask, having superb fighting skills and superpowers at the behest of supernatural beings, and being among a chosen few who can put a stop to evil doers isn’t exactly compelling to me the way it was when I was actually in high school. Those elements are fun, but the more I’ve played of the game, the more I’ve come to realize that it’s the more mundane activities that have captured my imagination.

Much of the game is comprised of doing everyday activities: going to school, answering questions in class, going to a part time job. You can wander around the streets of town and stop into a batting cage or arcade. You can chow down on a monster hamburger or go shopping for plant food. Sounds sort of amusing, but ultimately unfulfilling for a game, one might think. Of course, the game knows that having complete freedom to do whatever you want whenever you want would get pretty old after a while. To make everyday life more interesting, they brilliantly put limits on how long you have before each major event. Every story arc in the game has an end date. You know about it, everybody involved in the plot reminds you that it’s looming, a calendar appears each day and a dagger is stabbed into the current day. It’s a considerable threat. Suddenly, making some coffee or going down to the book shop feels much more important because it takes up what precious time you have left. Each action has weight and significance, no matter how small, because you choose to do it with the understanding that it all might end in the near future.

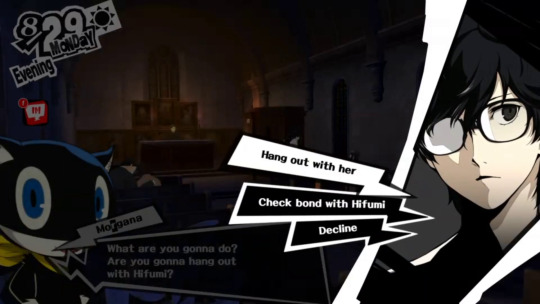

I love the way this manifests itself in the relationships you have with the other characters. Over the course of play, you meet and befriend various people in the community, mostly fellow classmates. Several of them join your cause to turn people from evil to good, either becoming playable characters in your party, or aiding you in other capacities, such as boosting your group’s public perception. To strengthen yourself and those who fight with you, you have to spend time with these people and grow your relationships. This has always been the most interesting part of Persona games to me, and 5 feels like a real pinnacle of this idea.

The types of relationships you have vary quite a bit when compared to previous entries in the series. There are your close knit group of friends, of course, but there are also numerous adult figures who play prominent roles. There is Sojiro Sakura, or Boss, a grumpy coffee shop owner who takes you in when no one else would. There is also Sadayo Kawakami, your home room teacher whom you accidentally discover moonlighting as a “maid” for a service of uncertain intentions. These “adult” relationships, for lack of a better term, come about due to unusual circumstances, and aren’t intended to be portrayed as typical for someone of high school age, nor for a high school aged player or even young adult. Their circumstances feel specifically targeted to garner sympathy from the player, rather than empathy.

Your relationship to Sojiro is particularly interesting, to the point where I saw myself more in him than in the main character.

So why, then, are the playable characters all high school students? Despite horrible things that happen and the overall bleak underpinning of the game, Persona 5 is a portrayal of an idealized high school world. When you start the game, you’re an outcast. No one wants you around, they spread rumors about your criminal record, they treat you like a burden and source of shame. The good news is that things only get better for you. Armed with quiet confidence, you have the agency to change people's’ minds by getting to know them, spending time with them, learning about them. Engagement helps everyone get beyond stereotypes and see each other for who they are. This is, unfortunately, not the way high school works for many.

The social pressures that we face as teens and young adults are difficult to solve over conversations and bowls of ramen. We hold fears about what others will think and we don’t yet have the maturity and self-awareness to deal with those fears appropriately. The power trip for Persona 5 isn’t that you can wield a cool sword and gun and fight a bunch of Shadows, it’s that you can talk to people, form bonds with them, understand them. You have the superpower of level-headedness and retrospect. Mechanically, the game rewards these behaviors by leveling up your relationships with the people you spend time with. Leveling up relationships gives you new abilities that make the dungeon exploration and combat easier. This is important, of course, because games have rules and a game’s mechanics should work together. The mechanics in Persona 5 are well balanced, but thanks to the strength of the writing, the convincing performances by the actors, and the social constructs built up within the game, the rewards for strengthening character relationships start to feel less and less vital. You eventually want to spend time with your friends not so much because you’ll get a power up or new ability, but because you have compassion for the characters and want to help them however you can.

The relationships you have with female characters can extend beyond friendship. The positive implications of this are a lot less clear than they are for your friendships in general. How this plays out largely depends on who the player is. It’s very easy to spin the friendships you have with the women in the game as extremely positive. You spend time with them as you would every character. Your bonds grow as you learn about them and help them navigate through complicated emotional situations. The fact that you can also attempt to date them can also be seen as very positive. A solid friendship is a wonderful base from which a romantic relationship can be built, but a few key aspects undermine this a bit.

You can date multiple women in the game. That, alone, is not so much the problem. The issue arises in that there is no way to gain the consent of said partners for the multiplicity of your coupling. It’s essentially all done on the down low, and it can become a bit tricky if you’re out on a date with one partner and happen to run into another. On the one hand, it’s nice that there are repercussions for behaving in this way, limited though they may be. Choosing to cheat means you’ll eventually be caught and your romances will be terminated. For the sake of the game’s story, this is fine, though it would have also been really interesting to be able to explore the interconnectedness of your relationships more fully. Each relationship is treated individually, which works from a mechanical perspective, but feels a bit disingenuous when human relationships are a lot more nuanced and complex than simple one on one interactions. There are implied trade-offs in the game, such as choosing to hang out with one person over another, but there are no real punishments for this other than losing time. Getting caught by one of your girlfriends is about as far as this is explored, and that’s a real shame. With how much the game emphasizes relationship growth, the series seems to be begging for expanded views on what kind of relationships are possible between and among the various characters. And this is completely ignoring the fact that women are the only possible romantic partners to begin with.

While the depth of the relationships can be a bit unfulfilling in some respects, it is important to remember that the player has choices. You can choose which friendships you want to strengthen, and more importantly, when. You can choose to pursue a romance with someone or not. Dating is not a requirement at all. That choice is what ultimately feeds into the power fantasy. High school students often don’t have the luxury of choice, or at least feel as if they do not have choices they can make. You, as the player, have choices all the time. You get to decide where to go, what to do, when to explore the distorted palaces of the game’s antagonists, and when to kick back with a friend and watch a movie. That is significant. It also helps when you get to voice your opinion with a little bit of sarcastic wit or humor. The ability to be comfortable in your own skin is all over this game, and that’s a really great thing.

You are always asked beforehand if you are sure you want to spend time with your friends, just in case you would like to spend time elsewhere.

Persona 5 is definitely a game made for adults, or at least, for certain types of adults: adults who might still struggle with navigating our social world with curiosity and confidence. It’s also for adults who did not feel they had much control over their lives at a younger time and are in search of a way to come to terms with that. It’s important to note that the characters around you are often in crisis. They get to act the way teenagers would act. They feel pride, insecurity, afraid, helpless. You are there to back them up, help them realize confidence within themselves, be a non-judgmental figure so they can have positive mental health. You get to be largely immune from all the chaos because this isn’t your life and and in your life you have probably already faced the emotional turmoil that goes along with teen age, even if you didn’t have to suffer problems as serious as an abusive coach or being framed for assaulting a woman on the street. Getting to play as the mediator of these terrible fictionalized problems can help put perspective on the real problems that we do face where we feel like the characters in crisis instead. I’m not sure younger players would necessarily be able to understand that. I hope they could, but as a 30 year old, it’s kind of incredible that a video game can remind me that there are ways to navigate our difficulties and they don’t require becoming a superhero so much as they require being emotionally available to ourselves and others.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Addendum To Aaron Hernandez Story

This post is intended as a followup to the post “Aaron Hernandez: A Case Study About What’s Wrong With Modern Society”, which was originally published on May 7th 2017. As such, a link to the content here will be added to that post as a post scriptum.

To understand what will follow, I strongly recommend that you read the abovementioned post first.

There have been many developments on the Aaron Hernandez story. As such, they confirm the blog’s main assertions:

The story of Mr. Hernandez poses a big risk to modern sexual philosophy and the “Straight”-”Gay” dichotomy, and threatens to completely collapse both

Numerous authorities within the dichotomy (“gay” and “straight” media, LGBT leadership, etc) are well aware of the first bullet point, and as such are trying to bury the story

Firstly, after the first Outsports article on Aaron Hernandez, all media did as the article asked, and basically stopped discussion on the matter. In doing so, they were expecting (and subtly ordering) their audiences to do the same.

This is a prime example of how modern sexual philosophy works to defend itself, and how a society facilitates that defense mechanism. In this case, the strategy went as follows:

”Gay” leadership and media signal that they don’t want to discuss the case

Within the dichotomy, the “gay” side is given total authority over discussion on same-sex activity. Thus, if the “gay” side doesn’t want to discuss it, the “straight” side has no reason to discuss it either. Thus, the Outsports article was used as a pretext to decrease coverage on the “straight” side.

Both sides keep completely mum on the case, and as a result, it’s kept somewhat in the dark

Similar strategies were used with the “g0y” movement and Man2Man Alliance, where the “gay” media castigated and ignored them, and the “straight” media followed their lead in not covering them. In this way, anything that threatens the status quo is neutralized.

Let me be clear, and you probably realize the following too: for a media that thrives on speculation, this is highly unusual. Both “gay” and “straight” media usually feast on speculation on whether some celebrity is “gay”. Yet, when so much suggests that Aaron Hernandez was into guys too, they leave all forward movement on the case to the family. In doing so, they claim that it’s out of sensitivity for the family, but that’s only a front. They’ve been far less merciful with celebrities like Cristiano Ronaldo and Aaron Rodgers, who also have families.

The real reason is that, if the Aaron Hernandez case is explored enough, it would soon become evident that modern sexual philosophy is COMPLETELY WRONG. It would completely destroy a philosophy that so much of U.S. society hinges on. It would turn U.S. society upside-down in a way they don’t want.

As such, I hope my LGBT-identified readers are taking note of their leadership and media. They only care for sexual behavior that supports the fundamental message of modern sexual philosophy - that same-sex eroticism is inherently abnormal and aberrant. If the behavior doesn’t do that, the LGBT movement wants nothing to do with it.

Yet, their efforts have only been moderately successful so far. Public interest in the story is still so high, the media has had no choice but to report trickles of it, and acknowledge developments in the story.

For example, Shayanna Jenkins-Hernandez (Mr. Hernandez’ fiancee) did an interview on “Dr. Phil” during May 2017. During that interview, she flatly denied all rumors that he was “gay”, and said further that he was “very much a man”. It was revealed that she first became aware of the rumors during Mr. Hernandez’ trial, when his defense team let her know. She also revealed that Mr. Hernandez and herself spoke about the topic several times, and each time, he completely denied he was “gay”.

First of all, I wish to say that Mr. Hernandez was telling the truth. Remember what was said here about the word “gay” - that it’s a word that marries same-sex activity with a “gay” culture of anal play, drag, and gender-atypical behavior. Meanwhile, while it’s likely that Mr. Hernandez was bisexual in his behavior, it’s very clear that he also roundly rejected the LGBT identity. Given the complicated meaning the word “gay” has, he was perfectly justified in saying that he wasn’t “gay”.

However, there was also something conspicuously absent from the interview. It was something that would put all gossip to bed - the suicide letters. Where were the suicide letters? To prove her point, why didn’t Ms. Jenkins-Hernandez cite them as proof that he wasn’t “gay”? Especially since they’re now in her possession in their unredacted form, and since she has most likely read them by now? Those suicide letters were testimony from the man himself on who he was, yet during such a key moment, they’re nowhere in sight.

There’s only one reason why they were absent: they would somewhat undermine the statements of Ms. Jenkins-Hernandez, and she knows that. Don’t be fooled. It’s true that he wasn’t “gay”. However, that doesn’t mean that he didn’t sexually interact with other guys. Indeed, the sports world contains a highly homoerotic culture, where its players can eroticially interact with each other without any “gay” spectre. From all appearances, Mr. Hernandez immersed himself completely within that culture, and enjoyed it immensely.

Thus, and to the contrary, their unignorable absence actually confirms a conclusion made in the first post: the most problematic aspect of those letters are their content. Furthermore, it also confirms that such content is definitely homoerotic in nature, and would make clear that he sexually interacted with other guys. That’s the only way those suicide notes, the biggest “smoking guns” that would end all speculation at once, are absent when they’re most valuable.

In this, I don’t fault Ms. Jenkins-Hernandez. Modern sexual philosophy works to preserve itself, and will sacrifice anything to do so. Meanwhile, the Hernandez family is doing everything to save Mr. Hernandez from being painted as “gay”, or even having that suggested about him. Certain parties would use them as justification for calling him that, even if closer inspection would reveal a more nuanced story. Thus, I understand why they might still be sheepish about revealing the letters.

Other developments in the month of May further confirm this blog’s conclusions. To pacify public interest in the case, the Boston Globe filed a FOIL (Freedom of Information Law) request for other prison correspondence from Mr. Hernandez. Those letters were then circulated across the media world, and are available for your viewing in this link.

As a side note, the Globe could do this because all of Mr. Hernandez’ correspondence is now public record, including the suicide notes. This is because they are currently being held by local authorities, and by virtue of that, they now belong to the public. Any news organization can obtain them at any time through a FOIL request. Thus, the relative silence on the story isn’t for lack of resources; it’s because they don’t want to do the work. As said before, the coverage blackout is being done on purpose. But I digress.

Anyway, the letters reveal that Mr. Hernandez had very friendly relationships with his other cellmates. The first four contain Mr. Hernandez repeatedly asking (and at one point pleading) to be placed in a certain cell block. That cell block contained men that he knew previously, and at least one man who he considered a “brother” and his “heart”. The last letter in the link attached has Mr. Hernandez addressing “false gossip” that was circulating around the prison, while making the same request to be placed in that certain cell block.

In the letters, there are several redactions made. All of the names mentioned are redacted, which admittedly is common practice, and is firmly within the bounds of FOIL law in general. However, there is one redaction made which, in my opinion, is a little odd. The last letter listed contained the following sentences, as Mr. Hernandez is addressing false gossip: “I have been hearing from many or rather few thinking that I’m ‘[redacted]’. But that is false. People are always coming up with things that are incorrect.”

Given the developments of the past few weeks, and the immediate context of the other attached letters, the redacted word is most likely the word “gay”.

At this point, I’m wondering on what legal grounds this redaction was done. From what I can tell, the closest exception that would qualify would be on grounds of privacy. According to the Massachusetts FOIL law, certain personal details can be redacted “which may constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy”. As such, the decision to redact “requires a balancing between the seriousness of any invasion of privacy and the public right to know”. As such, in practice enforcement leans toward non-disclosure.

However, I can’t see how disclosure of the described action - dismissing “gay” rumors - necessarily counts as an invasion of privacy. Within the context of the letter, it only confirms what we already know about Mr. Hernandez, and the rumors that consistently dogged him. The fact that a person is fighting “gay” rumors usually isn’t state secret.

In the end, I don’t know exactly which party influenced that particular redaction. All I know is that it was effective in further obscuring the Hernandez story. Within the letter that redacted word didn’t reveal much. However, in combination with the other released letters, along with the likely content of the unreleased suicide letters, it reveals so much more. All of that correspondence reveals a man who was shamelessly close to men - to the point of calling another man his “heart” - yet flatly denies identifying as “gay” or LGBT. From this, two conclusions present themselves that subvert modern sexual philosophy:

Same-sex activity and the LGBT identity and culture are not (and need not be) intrinsically linked

Same-sex activity is not an exclusively “gay” phenomenon

There’s one more factor to consider. Remember that Mr. Hernandez was one of the top football players in the NFL. This is very important because in U.S. culture, male athletes are considered the greatest fulfillments of masculinity. If these “alpha males” are revealed to be constantly having sex with other men (and each other), it completely undermines the fundamental message of modern sexual philosophy: that same-sex activity is inherently abnormal and aberrant.

As such, if the redacted word was released, I hardly think Mr. Hernandez’ privacy would be harmed. It would be much more harmful to modern sexual philosophy, the parties that rely on it for power, and the various social infrastructures that depend on it.

If this seems confusing to you, keep in mind that many parties directly depend on the “Straight”-”Gay” dichotomy (the highest fulfillment of modern sexual philosophy) for their power, including:

The Christian churches and their clergy, whose condemnation of homosexuality depends on most parishioners believing that they are truly “straight”.

Ex-”gay” ministries, for obvious reasons

Politicians who receive support from the clergy and devout Christian populations.

Various companies benefiting from messages that being “straight” (and thus being gender-conforming) requires purchase of certain commercial goods.

The “gay” leadership, whose authority depends on the idea that people attracted to the same sex are a small and easily identifiable minority, who need their guidance and supervision to survive.

Politicians who receive support from the “gay” leadership

Condom and lube manufacturers, whose bottom line is helped by the cultural practice of anal play

The medical-industrial complex, who sell drugs treating injuries and diseases caused by anal play

The parties involved constitute huge parts of U.S. society, which is why both “straight” and “gay” media are distinctly uninterested in covering the story. The story destabilizes modern sexual philosophy, and by extension, destabilizes their power and salaries.

Indeed, even with the relatively few developments in the case, the “straight” media is trying to keep itself far away from it. Meanwhile, following the edict of the Outsports article, the “gay” press has been almost silent on the matter. The only item they covered in the last month was the Dr. Phil interview, to convince people that there’s nothing to see here.

However, even with all this posturing and scrambling, they’re actually worse off than they were before. It seems Mr. Hernandez’ friends and family are less willing to cooperate with the coverup. On May 24th, Jonathan Hernandez (Aaron’s older brother) released a cryptic statement saying he wanted to reveal “Aaron’s truth”, to counter “many stories about my brother's life [that] have been shared with the public”. Furthermore, Kyle Kennedy (Mr. Hernandez’ supposed male lover in prison) hasn’t retracted his determination to reveal his side of the story. To that end, in May he renewed his demand that authorities give him the suicide note that was reportedly meant for him.

It’s clear that “the powers that be” of the dichotomy are in deep trouble. The Hernandez story is difficult, if not impossible, to frame in a way that supports modern sexual philosophy. Every move the media makes shows that they’re trying to hide something, and seems to arouse more interest in the story. More of Mr. Hernandez’ loved ones seem willing to blab.

Sooner or later, the dichotomy (and the philosophy it represents) will have to be revealed as a fraud, and completely untrue. At this point, it’s not a question of “if”, but “when”.

What’s unknown is what will happen after that. The outcome could go one of two ways.

After it is revealed to be a fraud, modern sexual philosophy is thrown out completely. U.S. society is turned completely upside down, as a more accurate way to describe sexuality is sought. This is the outcome I personally want.

After it is revealed to be a fraud, enforcement of modern sexual philosophy is made even more stringent. In sheer defiance, its authorities will insist upon people adhering to the dichotomy it produces, and will double down on enforcing its rules and labels.

Remember that for all its rigor, the dichotomy is still a rather informal system. There’s no law requiring people to identify as “straight”, “gay”, “queer”, etc. There’s no secular law requiring people to believe same-sex activity is inherently abnormal. It has power only because so many people believe it to be true. This is why so many societal institutions (like the U.S. education system) are designed to sustain that belief.

However, moves have been made to institutionalize modern sexual philosophy in recent years. Increasingly more college campuses are asking their students which labels they identify with. More governmental agencies are making tallies on how many people identify with which label. This is despite the fact that these labels are under increasing scrutiny by more parties. It should be noted however that such questions are still optional.

When modern sexual philosophy is revealed to be false, such efforts might only intensify in response. Adopting one of its sexual labels might become a mandatory feature of more surveys, but that might not be all. The principles of modern sexual philosophy might become codified in law, and its sexual labels might become as necessary as Social Security identification numbers. As a result, a person will be unable to socially function if they do not believe in modern sexual philosophy, and do not give it support by adopting the labels of its dichotomy. If that seems too totalitarian to be believable, remember that something like the Patriot Act was also once considered unimaginable.

Of course, if the majority don’t believe in it, even that scenario will be impossible.

Thus, if you’re here for the first time, know that there’s nothing tying you to modern sexual philosophy that’s unbreakable. Thus, I urge you to read “The ‘Straight’-’Gay’ Dichotomy: How It Works”, to fully understand how that system functions. I also urge any who read this to go to “For Straight People (though not exclusively)”, which will point to philosophies and forms of same-sex behavior that don’t hinge on demonstratively false concepts. Also read the page “History of the Concept of Homosexuality”, to see how this concept evolved into its modern day meaning. Don’t be afraid of talking about what you learn to others, because that’s the only way progress will be made. Thus, the fissure created by Mr. Hernandez can further grow.

There’s another move you can make that’s important: don’t stop following the Aaron Hernandez story. Don’t be fooled by the “gay” and “straight” press, with their insinuations that there’s nothing to see here. There IS something here, but they just don’t want you to see it, to preserve their own power. Insist on more coverage and analysis. Double down on asking more questions. They can only hide so much, and run so far.

As a last note, I hope that my LGBT-identified readers are noticing how LGBT media and leadership is treating them. There’s no other way to put it: you are being flimflammed and bamboozled by your own media. Your intelligence is being insulted by those who are supposed to be your advocates. They’ve made perfectly clear that they don’t support same-sex activity in all its forms, but only the kinds that support the homophobic message of modern sexual philosophy. This is my question to you - if they are so willing to lie to your face, do they really deserve your unquestioning support?

Make no mistake; this story is far from over. For your own good, stay tuned.

#Aaron Hernandez#straight#gay#lgbt#Bros being bros#Gay Christian#gay christianity#lgbt christian#lgbt christianity#bisexuality#Bisexual#bisexual pride

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two (Totally Opposite) Ways to Save the Planet (Ep. 346)

Can technology solve the challenges of food, water, energy, and climate change that come with a growing global population? (Photo: Oast House Archive/geograph)

Our latest Freakonomics Radio episode is called “Two (Totally Opposite) Ways to Save the Planet.” (You can subscribe to the podcast at Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or elsewhere, get the RSS feed, or listen via the media player above.)

The environmentalists say we’re doomed if we don’t drastically reduce consumption. The technologists say that human ingenuity can solve just about any problem. A debate that’s been around for decades has become a shouting match. Is anyone right?

Below is a transcript of the episode, modified for your reading pleasure. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, see the links at the bottom of this post.

* * *

Charles MANN: At one point I was going to call the book Toblerone For Ten Billion. That was vetoed by my editor, for some reason.

Charles C. Mann is a journalist who writes big books about the history of science. His current interest is:

MANN: The modern environmental movement, which I would argue is the only successful ideology to emerge from the 20th century.

By the middle of the twenty-first century, the global population is expected to reach 10 billion.

MANN: And the question is, are we going to be able to satisfy all their demands for food, water, energy.

Also: Toblerone.

MANN: Because in addition to food and water and the basics, they’re going to want occasional treats.

And there’s one more big concern.

MANN: How are we going to deal with climate change? Those are the big challenges.

The future of food, water, energy, and climate change — big challenges indeed. How will those challenges be met?

MANN: There have been two ways that have been suggested, overarching ways, that represent, if you like, poles on a continuum. And they’ve been fighting with each other for decades.

That fight, and those two worldviews, are the subject of Charles Mann’s latest book, which he wound up calling The Wizard and the Prophet. The prophet sounds the alarm and wants us all to cut back. The wizard urges us to charge forward, confident that technology will solve our problems. Surely you’ve heard these prophets and wizards, speaking to us — and usually speaking past each other.

Al GORE: The next generation would be justified in looking back at us and asking, “What were you thinking? Couldn’t you hear what the scientists were saying? Couldn’t you hear what mother nature was screaming at you?”

Nathan MYHRVOLD: The way to have a dramatic message is to say we’re all going to die.

The prophet encourages a return to nature.

Mary ROBINSON: We need to replant and save rainforests.

The wizard finds the prophet’s suggestions naïve.

MYHRVOLD: Well, that argument is so absurd on so many levels that the miracle is that there are people who can say it with a straight face.

The prophet sees grave danger in the immediate future:

ROBINSON: We’re going to be into tipping points. The Arctic is going to go. We’re going to see a sea-level rise that will wipe out islands.

The wizard is more optimistic:

MYHRVOLD: I think that if we put our heads together, we will come up with ways to cope. But that’s no fun compared to saying we’re all going to die next Thursday.

Today on Freakonomics Radio: are you more prophet or wizard? Why? And: is anyone right?

* * *

When Charles Mann was in college, there was a book that showed up on the reading list in several classes.

MANN: Ecology, you know, political science, demography.

So he had the chance to read it several times. It was called The Population Bomb. There was a warning on the cover. “While you are reading these words,” it said, “four people will have died from starvation. Most of them children.”

MANN: And it really hit home, and I thought, oh my gosh. The edition I read, which is the first edition, said there would be massive famines in the 1970’s. Basically, it said we are in deep, deep trouble.

And then, in the 1980’s:

MANN: In the 1980’s, I sort of noticed this hadn’t happened.

So were the famine predictions simply wrong? Or: was the doomsaying a calculated strategy, designed to shrink the Earth’s population before it was too late? Environmentalists were saying humankind was pushing the Earth’s limits; technologists, meanwhile, said those limits were nowhere in sight.

MANN: The world is finite, obviously, and the real question is not whether there are limits, but whether the limits are relevant. At some point, we do run out of planet. But what exactly that limit is and when we’re going to hit it — I think it’s much less well-known than either side says it is.

DUBNER: So did you come to feel then that both camps — rather than wizards and prophets, we can call them techno-optimists and environmentalists — do you feel that both camps to some degree intentionally misrepresent their strengths in order to engender support, when in fact the reality — and indeed, most solutions — is probably much more nuanced than that?

MANN: I think so. I’m not sure about intentionally, because people get convinced. I think that neither side truly appreciates how much of a leap in the dark jumping into the future is. They’re both overly confident that we know what we’re doing. Take energy for instance. The best solution for the prophets is this whole sort of neighborhood solar thing. But that depends on there being innovations in computer technology and innovations in energy storage, in energy transmission, that simply aren’t here yet. Maybe they can be done, but do we actually know how to do it? No.

Similarly, the wizards, they typically imagine very large numbers of next-generation nuclear plants. And they argue, totally rationally and totally correctly, that these have the smallest environmental footprint of any form of energy generation. They’re completely right about this. But I’m not actually seeing that happening. Nobody seems to be building these things. Next-generation nuclear plants have been around for 30 or 40 years, at least on the drawing board, and only a few of them have actually ever been tried. So you wonder, how is that going to happen? Both of these: how is this going to happen?

While wrestling with the best ways to move forward when it comes to energy, food, water, and climate change, Charles Mann found himself looking backward. Specifically, to two men — the wizard and the prophet who make up the title of his new book. Its subtitle is: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World.

DUBNER: Let’s start with your prophet, William Vogt. So tell us briefly about him, and why he was the one who qualified to become the prophet in your book.

MANN: Well, he is, more than anyone else, the progenitor of the modern environmental movement. And the basic idea of it is one of limits. He called it carrying capacity. And this is that the Earth, the environment — another idea he invented, the environment — is governed by these ecological processes and we transgress them at our peril. And therefore we have to hunker down. We have to put on our cardigan sweaters and turn down the thermostat and eat lower in the food chain and all that sort of stuff. And he put this all together in a book. It’s now forgotten, but it was hugely influential, called Road to Survival. It was published in 1948, and it’s the first modern “we’re all going to hell” book, if you know what I mean.

DUBNER: As apocalyptic as his beliefs and predictions were, the title itself connotes at least survival, if not prosperity. Was the road to survival, basically, hope that a lot more people don’t get born and/or a lot of people die, and we have enough to go around, and we get small?

MANN: Much of the book is a passionate screed for population control, sometimes written in language that makes you cringe. Another big chunk of the book is about how we should do things in a way that fits better within nature, and that’s things like stop farming within marginal land. It’s paying attention to erosion. It’s not overusing fertilizer.

DUBNER: So when you say that his discussion about population growth makes you cringe, was it from a classist perspective, the cringing comes from, or racist — how would you describe it?

MANN: I would say yes, both. He was, basically, pretty misanthropic. And it’s hard to avoid noticing that although he was very, very hard on rich, white people and overconsumption and being wasteful and destructive and so forth, that the brunt of the population-reduction stuff he’s talking about are on poor, brown people in other parts of the world. And he sometimes described them in language that is really kind of appalling — he talks about Indians breeding with the irresponsibility of codfish, and so forth. In this he was very much a man of that time, unfortunately. And this is something that environmentalists today should be aware of and think about. Their movement has some pretty deep roots in some pretty bad places.

William Vogt’s work inspired the first best-selling environmental book: Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson. Here’s Carson:

Rachel CARSON : Can anyone believe that it is possible to lay down such a barrage of poisons on the surface of the earth without making it unfit for all life?

MANN: And books like The Population Bomb; Al Gore’s first book, Earth in the Balance; The Limits to Growth. All these great environmental classics all stem directly from his work. That’s why I picked him.

William Vogt was born in 1902 on Long Island, New York, back when it was largely bucolic.

MANN: And then it was just engulfed by suburbanization. So he tried to find nature, he ends up in a Brooklyn slum, and is plucked from that and goes to one of those schools they have in New York where the deserving poor are given special education.

He becomes the first college graduate in his family — with a degree in French literature.

MANN: And a degree in French literature was probably as useful in career building then as it is now. And he turned to ornithology. He was a passionate birdwatcher. I should mention that he had polio, as well, and he went all over the place despite finding great difficulty in walking and having canes and braces and having to be hauled around and so forth. He was a gutsy guy. And through a whole series of unlikely circumstances — he ends up becoming the official ornithologist of the Peruvian government on these guano islands off the coast of Peru. And these islands have had seabirds roosting on them for millennia upon millennia. And the seabirds do what they do, which is to eat fish nearby and excrete huge quantities of bird poop. I’m allowed to say that on your podcast?

DUBNER: Sure are. Absolutely.

MANN: You guys are just, you know, hang loose, right?

DUBNER: We’re very pro-poop.

MANN: Okay. And this, in the 1850’s, became the origin of today’s hugely important fertilizer industry, these vast heaps of bird poop that were on these islands off the coast of Peru. And they became very important to the Peruvian government. To maintain the supply of poop, you need to maintain the supply of birds. In the 1930’s, the supply of birds started declining, and they brought him in, as he said, “to augment the increment of excrement.” And he spent three years there, and he actually did a remarkable piece of ecological science, a foundational piece.

He realized that there is an oscillation of the currents there, it’s called today, El Niño, La Niña. And he argued that when the warm water came in, when the El Niño phase came in, the anchovetas, which were the fish that the birds ate on these islands, swam far out into the Pacific to avoid the warm water. They like cold water. And the birds couldn’t reach them. And this recurring phenomenon put a cap on the number of birds that you could have on these islands. And you could not augment the increment of excrement — that nature set these bounds. And if he did increase the bird supply, it would just mean that things would be worse when the next El Niño came in. And this was this powerful insight for him. This is the way nature worked. And he put it together.

And then he made two big steps, which I think are enormously important. One is that he said, this kind of phenomenon, which is called a carrying capacity — means that only so much can be produced because of these natural limits — could be stretched like taffy to cover the entire world. The world can be thought of as a single environment with a single carrying capacity. And the second, he said, is that we’re exceeding it. Or we’re about to exceed it, and that’s going to bring us into trouble.

DUBNER: William Vogt predicted, specifically, personally, he predicted famine, which as you write, hasn’t come true. So in the 1940’s, the global famine death rate was about 785 people per 100,000 — so, call 800 per 100,000. It’s now 3 per 100,000. So let me ask you this: as a prophet, do you need to be right? Or is it enough to sound the alarm? Because obviously on that dimension at least, a prediction of famine and population wipeout, Vogt was wildly wrong.

MANN: Now, I think there are two responses to it. The first is, “Okay, you’re right, it didn’t happen, but it will happen eventually. We just got the timing wrong.” And the second response, which, to my way of thinking at least, is more nuanced, is, “You’re right, we didn’t get that right, but a lot of the other things they predicted, we did get right.” And that is true. Nitrogen pollution is a huge issue. I mean, about 40 percent of the fertilizer that’s been used didn’t get absorbed by plants, and it got — either went up in the air, where it interferes with the ozone layer, not a good idea, or it becomes nitrous oxide, closer to the ground, in the air, which has caused all kinds of health problems. Or even worse, it goes into the streams, which goes into the rivers, which goes into the ocean, causes these enormous blooms of algae and other aquatic plants. These die, they fall down to the bottom. Microorganisms consume them, it’s sort of an orgy of breakfast, and they metabolize so quickly they suck all the oxygen out of the air and you get these huge dead zones in coastal areas around the world. And you can go on and on. All that stuff, if you point to that, they’re looking better.

At the same time as William Vogt, the prophet, was sounding the alarm on overpopulation and what he saw as the resultant famine, there was another scientist whose discoveries would lead to a dramatic growth of the global population. This is the wizard in Charles Mann’s book; his name: Norman Borlaug.

MANN: He was born in a very poor family in Iowa, poor soil, terrible, hardscrabble farm, worked like a dog. He was determined to get off of that, he really hated it, clearly. He thought his way to do it, because he didn’t think he was very smart, was athletics. To do that, he needed to go to college, which he was able to do, really, thanks to the fact that Henry Ford had invented the cheap tractor.

DUBNER: Which let his family free him up from the labor, yes?

MANN: Right, freed him up from the labor. And even more important, when you have horses, and oxen and so forth doing the labor for you, you have to grow food for them, and you have to tend to them. And they’re just huge time sinks, and they’re land sinks. And a typical small farmer in those days, about 40 percent of the family’s land was devoted to growing the food for the animals.

DUBNER: That was one of my favorite statistics in your book. I mean, it’s one of those things that, the minute you see it, it makes perfect sense. But I never would have imagined it.

MANN: Exactly. It’s almost like doubling your land. And of course your land becomes more productive. A tractor is a huge, huge deal.

DUBNER: On two dimensions at least, right? In terms of making more available land and, obviously, increasing the pace of the labor.

MANN: Right, and making people’s lives better, and also being able to accomplish more, just, — it’s vastly better.

Thanks to that tractor, Borlaug did go to college; he studied forestry and eventually got a Ph.D. in plant pathology and genetics. During World War II, he worked at DuPont, trying to make water-proof ration boxes and mold-proof condom wrappers. Then he got a job with the Rockefeller Foundation, trying to boost the production of wheat in Mexico.

MANN: And the remarkable thing is, he succeeded, despite not knowing Spanish, never having been out of the country, never having bred wheat before, hardly having worked with wheat before. And the wheat genome is terrifically complicated, it’s five times as many genes as there are human genes. And because plants can do weird things that mammals can’t, there’s three copies of each genome in every cell. There’s six different versions of each gene. It’s just a mess.

DUBNER: So his breakthrough came about from what you described as shuttle breeding. Can you describe A, why that was unusual, why more people didn’t try that; and B, why it worked?

MANN: More people didn’t try it because it was literally written in the textbooks that it wouldn’t work. And the thing is, he was so ignorant — very occasionally, ignorance is good. And what he thought to do was — plant breeding is very slow, because in most places there’s only one crop of wheat that you grow a year. It’s either called winter or spring wheat, and you have to wait an entire year to grow the next. And there had been a dogma that you have to breed the crop in the area in which it’s going to be grown. And he thought, “Wait a minute. What if I grow one crop in the south of Mexico and one crop in the north of Mexico, where it’s warmer? And that way, I can do two a year and make things go twice as fast.”

DUBNER: Well, Borlaug found a way through, as you said, grit and luck, and a handful of other things, to make wheat a much, much, much more productive and more flexible crop. And this gave way to what we came to call the Green Revolution, and Borlaug went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize. So talk to me about the consequences of, really, this one man and what he helped produce, good and bad consequences.

MANN: Well, the good consequences are really striking. If you look at the data, shortly after the Green Revolution, wheat production in Mexico just soars. It basically quadruples. The same techniques come to the American middle west, and that’s when the American middle west becomes a huge agricultural powerhouse. Our yields just increase enormously. It goes to India and Pakistan. Same thing. Then, the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations are excited by what they’re seeing in wheat, and they set up the International Rice Research Institute outside the Philippines, and they resolve to do the same thing with rice. And yields triple there. And the world just grows enormously more food. And sometime in the 1980’s, for the first time in recorded history, the average person on earth has enough food year-round. And famine — except for famine induced by war — basically ends. It’s a huge moment. And I sort of think this should be taught in all the schools. So that’s the good part, and it’s a huge good part.

DUBNER: Okay, so let’s talk about the downsides of the Green Revolution. One of them, you write, is that it essentially fueled income inequality. Land became more valuable. It just created a lot of leverage. On the other hand, the alternative would be that everyone gets to be poor and hungry, other than maybe, warlords and kings, right? So how much credence should we give inequality as a downside of the Green Revolution?

MANN: I think you should give quite a bit of credence to it, because when we say, “inequality,” it sort of minimizes the actual experience, just as we are talking about, when a small holder’s farm is able to grow four times as much food, the land becomes four times as much valuable, and it becomes worth stealing. And in countries with very weak institutions, which is unfortunately most of the world, it was stolen, often with the active support of the elites in the government. And huge numbers of people were pushed off the farms and forced into slums, and communities were broken up.

DUBNER: And what about the environmental costs of the Green Revolution?

MANN: The big environmental costs of this are nitrogen pollution. What we talked about before.

DUBNER: So did Borlaug, later in life, acknowledge the costs of the growth that he helped produce?

MANN: Kind of. There’s a way that, when you’ve accomplished something, and somebody is carping, that you say, “Well yes, but,” and you acknowledge what they do and then you brush past it. He said, “Wait a minute, the work that we’ve done has saved hundreds of millions of people from starvation. That’s a big deal. And there’s no upside without a downside. So yeah, there’s a downside, but holy cow.” And I think that’s pretty easy to understand.