#enrique vila-matas

Text

Enrique Vila-Matas - ...Seguí viviendo en la desesperación, pero con momentos de felicidad extraña que de vez en cuando me llegaba —me sigue llegando— del rock and roll...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Voy andando como un vagabundo y de vez en cuando veo reflejada en los cristales mi silueta pasajera mientras me digo que la vida es inalcanzable en la vida. La vida está tremendamente por debajo de sí misma. No existe, además, ni la menor posibilidad de alcanzar la plenitud."

Enrique Vila-Matas, Muerte por saudade, en Suicidios ejemplares.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creo que soy el primer ser humano que descubre, más allá de los infinitos agujeros negros y del espacio etéreo, que el humor es lo último que se pierde. Esto no es exactamente lo que me habían enseñado en las escuelas y academias. Allí decían que era la esperanza lo último en perderse. Pero no. He descubierto que sólo el humor es lo que hay más allá de los límites de los límites de los límites ilimitados.

Enrique Vila-Matas, Exploradores del abismo

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Strange sea of an intense blue, dangerous like love.”

— Enrique Vila-Matas

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

After all, what are we, what is any one of us, if not a combination, particular and exact, of what we have done, what we have read, and what we have imagined?

Enrique Vila-Matas, Hijos sin hijos (DEBOLSILLO; March 8, 2012) (via Alive on All Channels)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carlo Emilio Gadda dedicó toda su vida a practicar, con un entusiasmo notable, lo que Italo Calvino calificó de «arte de la multiplicidad», es decir el arte de escribir el cuento de nunca acabar, ese cuento infinito que en su momento descubriera Laurence Sterne en su Tristram Shandy, donde nos dice que en una narración el escritor no puede conducir su historia como un mulero conduce su mula -en línea recta y siempre hacia adelante-, pues si es un hombre con un mínimo de espíritu se encontrará en la obligación, durante su marcha, de desviarse cincuenta veces de la línea recta para unirse a este o aquel grupo, y de ninguna manera lo podrá evitar: «Se le ofrecerán vistas y perspectivas que perpetuamente reclamarán su atención; y le será tan imposible no detenerse a mirarlas como volar; tendrá, además, diversos

Relatos que compaginar:

Anécdotas que recopilar:

Inscripciones que descifrar:

Historias que trenzar:

Tradiciones que investigar:

Personajes que visitar.»

En suma, dice Sterne, es el cuento de nunca acabar, «pues por mi parte les aseguro que estoy en ello desde hace seis semanas, yendo a la mayor velocidad posible, y no he nacido aún».

Enrique Vila-Matas, Barleby y compañía, 2000.

#Enrique Vila-Matas#vila-matas#vila matas#bartleby y compañia#barletby#tristram shandy#laurence sterne#carlo emilio gadda#gadda#italo calvino#desvio#infinito

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enrique Vila-Matas - Kassel no invita a la lógica. Editorial Seix Barral

0 notes

Text

Um leitor de ficção

Eu estou lendo a Ilustrada quando o escritor espanhol Enrique Vila-Matas lança seu novo romance chamado Montevidéu. A história fala de um homem que tem uma relação com a literatura meio tumultuada. Eu já tinha o seu último romance como Mac e seu contratempo. Eu gostei de seu estilo que conta a história literária onde não se tem uma aula chata de uma universidade sobre escritores que vemos nas…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

" Não há nada mais subversivo que a literatura"

Enrique Vila-Matas

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enrique_Vila-Matas

0 notes

Text

Enrique Vila-Matas, Montevideo, 2023

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enrique_Vila-Matas

0 notes

Text

mac und sein zwiespalt

roman von enrique vila-matas

erschienen 2022

im wallstein verlag

isbn: 978-3-8353-5246-9

(von tobias bruns)

mac wurde vorzeitig aus seiner arbeit gedrängt. notgedrungen muss er sich irgendwie die zeit vertreiben und sucht sich ein neues hobby. ab sofort schreibt er tagebuch, doch das eigentliche ziel ist es schriftsteller zu werden - er liebt es zu lesen und denkt auch ihm würde das schreiben gut stehen -, aber möchte er nicht irgendein buch, irgendeinen roman schreiben: er möchte einen roman schreiben, der unvollendet ist und posthum veröffentlicht wird - einen geplant nicht abgeschlossenen roman. das tagebuch ist seine übung für diesen plan, doch treibt ihn die angst, dass tagebuch selbst würde irgendwann als roman verstanden. seine frau - nun alleinversorgerin des älteren ehepaares - beäugt sein neues hobby mit misstrauen... zu ernst nimmt er es für sie, dieses tagebuchschreiben draußen in den cafés und bars des coyote-viertels in barcelona und des späteren überarbeitens und korrigierens. auf diesen touren durch sein viertel trifft er immer wieder auf den berühmten autor ander sánchez, einen nachbarn, der vor langer zeit einen roman geschrieben hat, auf den er nicht stolz ist. es ist ein roman über das leben eines bauchredners, der mit extrem langweiligen sequenzen gespickt ist. als mac das hört, macht er es sich zur aufgabe, aus diesem in den augen des großen schriftstellers peinlichen roman eine eigene, bessere version zu erschaffen. je mehr mac in den roman auftaucht, desto mehr parallelen zu sich findet er. in einer der geschichten ertappt er seine frau als hauptdarstellerin! wie kann das sein? er stellt sie zur rede, doch es gefällt ihm ganz und garnicht, was er zu hören bekommt...

wie wird man schriftsteller? wie wird man erfolgreicher autor? was ist das geheimnis? was ist überhaupt dieser prozess, den man durchgeht, um von einer idee zu einer geschichte zu kommen? mac und sein zwiespalt beantwortet keine einzige dieser fragen, doch beschäftigt sich der roman intensiv mit all diesen fragen - auf eine sehr erheiternde, mal tiefsinnige, mal leichte art und weise. macs literarischen ergüsse in seinem “tagebuch” sind mal überwältigend, mal intelektuell, absurd, naiv, kindisch, kreativ, philosophisch und manchmal gar alles zusammen und enrique vila-matas macht genau das, was sein protagonist niemals wollte: das tagebuch selbst wird zum roman! welch schicksalhafte wendung, die der autor seinem protagonisten da zuteil werden lässt. so schicksalhaft und unterhaltsam, surreal und romantisch, dass man diesen roman (und seinen protagonisten) einfach nur liebhaben kann! klingt komisch, ist aber so...

#mac und sein zwiespalt#enrique vila-matas#wallstein verlag#wallstein#philosophenstreik#roman#rezension#Literaturkritik#tobias bruns#lesenmachtglücklich#literatur#spanien#spanische literatur

1 note

·

View note

Text

Enrique Vila-Matas - ...«Si yo tuviera la fuerza de no hacer nada, no haría nada. Es porque no tengo la fuerza de no hacer nada por lo que escribo. No hay ninguna otra razón. Es lo más verdadero que puedo decir sobre esta cuestión»...

0 notes

Photo

Mac & His Problem

By Enrique Vila-Matas.

Design by Matt Broughton.

0 notes

Text

Tal vez ser un autor sea hacerse el muerto, situarse en el lugar del difunto, y no perder de vista ciertas perspectivas que abrieron pensadores como Foucault, para quien lo que la escritura pone en cuestión no es tanto la expresión de un sujeto que escribe cuanto la apertura de un espacio en el que el sujeto que escribe no deja de desaparecer.

Enrique Vila-Matas, Exploradores del abismo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

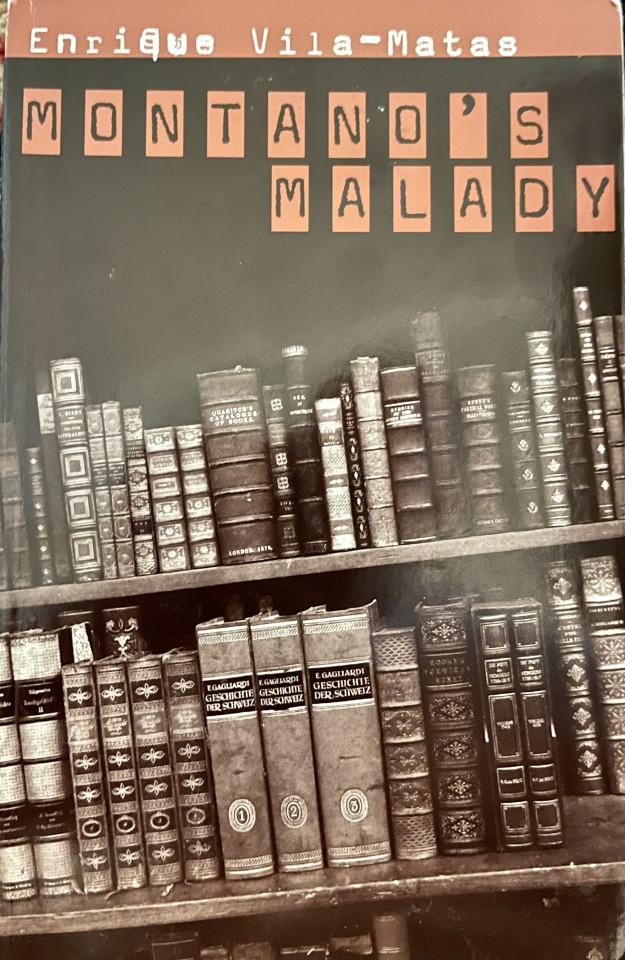

Montano’s Malady by Enrique Vila-Matas, translated by Jonathan Dunne

Perhaps this is what literature is, the invention of another life that could well be our own, the invention of a double. Ricardo Piglia says that to recall with a memory that is not our own is a variant of the double, but it is also a perfect metaphor for literary experience.

Having quoted Piglia, I observe that I live surrounded by quotations from books and authors. I am literature-sick. If I carry on like this, literature could end up swallowing me, like a doll in a whirlpool, causing me to lose my bearings in its limitless regions. I find literature more and more stifling, at the age of fifty it frightens me to think that my destiny is to turn into a walking dictionary of quotations. (p. 4)

***

Every day in Barcelona became horrible, very morbid. I would cry in my sleep and then wake up and tell Rosa that it was nothing, really, Rosa, just a dream or something like that, nothing, Rosa. But it was not a dream or even a nightmare, it was a mournful voice, I knew this very well, a voice that even at night prowled about me and told me that I was going to die and that I didn't have long to live. I would wake up in the night and tell Rosa that it was nothing, just a dream, but shortly thereafter I would go to the kitchen to have a drink. Rosa would follow me to the kitchen and, as soon as she caught me with a bottle of something, she would tell me that I was in a very bad way, that it would even be better for me to start writing reviews again and to think about literature, or else to travel, yes, to travel to a faraway country, I needed it. And I would stand there, openmouthed and sad, staring silently at the kitchen calendar. (p. 23)

***

I slept almost all the hours of the outward journey to Chile. The few moments I spent awake between one sleeping pill and the next were criminal. I could only think to flip through the in-flight magazine, where I came across some verses by Pablo Neruda, perfect for reminding me that death and literature existed: "There are lonely cemeteries, / graves full of bones without sound, / the heart passing through a tunnel, / dark, dark, dark, / as in a shipwreck we die from within ...” (p. 25)

***

"You destroy everything you love!" she exclaimed suddenly. I hadn't expected her to get heated up quite so soon. "I love my children and I haven't destroyed them," I answered jokingly, I really had not intended to pick a serious fight. "What children? Don't bring Montano into this, you've done him enough damage already, stuffing literature into the poor boy, he speaks in book—do you know what it means to speak in book?" I stopped and thought for a few seconds and, before I explained that I had planned the fight only for this diary and we would do well to continue the idvllic state in which we had been living since my return from Chile, replied (not wanting her to believe that a literary critic of my stature was incapable of answering her question), "To speak in book means to read the world as if it were the continuation of a never-ending text." (p. 33)

***

The story opens with a quotation from Macedonio Fernández with which my son presumably wishes to comment ironically on the lifting of his writer's block: "‘Everything has been written, everything has been said, everything has been done,’ God heard someone telling him when he had yet to create the world, when there still wasn't anything. ‘Someone already told me that,’ he rejoined perhaps from the old, cleft Void. And he began.” (p. 45)

***

I wonder how I can have been so stupid, believing for so long that I must eradicate my Montano's malady, when it is the only worthwhile and truly comfortable possession I have. I also wonder why I should apologize for being so literary if, in the final outcome, only literature could save the spirit in an age as deplorable as ours. My life should be, once and for all, purely and only literature. (p. 144)

***

DECEMBER 25 OR LE RICORDANZE

The memories of various lay anniversaries dance today.

On such a day, forty-five years ago, in 1956, Robert Walser died. After lunch at the sanatorium, he decided to go for a hike in the snow, to climb to Rosenberg, where there are some ruins. From the top there was a wonderful view over the mountains of Alpstein. The hour was soothing, it was midday, and outside there was snow, pure snow, as far as the eye could see. The solitary hiker set out and began to fill his lungs with the clear winter air. He left Herisau Sanatorium behind. He climbed through beeches and firs up the side of Schochenberg. Two children found him where he dropped down dead in the snow, in perpetual ecstasy over the Swiss winter.

Walser, or the art of disappearing.

In one of his novels, The Tanner Siblings, there are some lines that presage his own death in the snow; in the mouth of one character he places an elegy to Sebastian, the poet found dead in the snow. "With what nobility he has chosen his tomb! He lies among splendid green firs covered in snow. I don't want to inform anyone. Nature bends down to contemplate her deceased, the stars sing softly around his head and the night birds caw: it is the best music for someone who cannot hear or feel."

Walser, or the art of disappearing at Christmas, of knowing how on such a sentimental date to leave the writing room, the room of phantoms.

On such a day, thirty-nine years ago, on December 25, 1962, the Great Snowfall took place over Barcelona. It is one of the most important memories of my early years. That morning the patio of my parents' home appeared covered in snow and I couldn't believe it. To start with, I thought it was part of my mother's Christmas decorations. I remember that December 25th very well. Me with a scarf inside the house, listening to my mother say that for a city like Barcelona, so abandoned by the hand of God, it was a blessing that, even if it was only the once, He should have remembered us and brought us snow on the most appropriate day, Christmas Day, with divine punctuality.

For me, Christmas Day will always be the day of the Great snowfall. Wrapped in two jerseys and a scarf inside the house, I switched on the radio and suddenly we heard a message of peace and Christmas goodwill from Salvador Dalí, a few emotional words from the Ampurdán painter telling us that, from that day on, he planned to orient all his life toward Franco's Spain and the family: "Isabella the Catholic, consecrated hosts, melons, rosaries, truculent indigestion, bullfights, Calanda drums and Ampurdán sardines. To sum up: my life must be oriented toward Spain and the family."

We listened to that message in respectful silence mixed with some astonishment. The snow fell stealthily on the patio outside, as at the beginning of a Christmas tale.

"Dalí's turned into one of us," said my father.

On such a day, forty-five years ago, in 1956, W. G. Sebald's grandfather died, having gone out for a walk in the snow and collapsed on top of it at almost exactly the same time as another walker, Robert Walser, was also struck down on the snow, in a similar landscape.

Two dead for a single Christmas Day.

Eleven days ago, last Friday, December 14th, the writer W. G. Sebald died while out driving. He always seemed to have just emerged from another age: a slightly ancient man who, in sight of solitary landscapes, came across traces of a past in ruins that referred him to the wholeness of the world.

I am seated next to the Christmas tree in my home, and I remember the Great Snowfall of my childhood and that speech by Dalí, and I begin to listen to Vittorio Gassman reciting Leopardi's Le ricordanze, and I let the memories, mine and others', invade me, and I tell myself that without them and without those memories’ ruins, without memory, life would be even more distressing, though it may be even more distressing to realize that the more our memory grows, the more our death grows. Because man is just a machine for remembering and forgetting, heading for death. And I don't say this with sadness because it's also true that memory, disguised as life, turns death into something subtle and tenuous.

The memories dance for me and I adhere to the indispensable fabric of my memory and my identity—in this case, that reached with my double odyssey—and I tell myself that I am somebody only because I remember, which is to say that I am because I remember; I am the one memory has always helped, preventing him from falling into absolute distress, has helped during years with flashes and luminous sparks in which every day, in a ray of sun, charming and tragic, the tragic dust of time has danced for me.

There are two of me. I have a double odyssey's identity. One is lurking in the Chinese wall and the other, more Christmassy and sedentary, listens to Gassman at home: “Viene il vento recando il suon dell'ora / dalla torre del borgo. . ."

The detective's patience to trap a memory can verge on the ridiculous. One is satisfied with a cake dunked in tea; another, with a drop of perfume at the bottom of an empty bottle; another, with il suon dell'ora, a peal of bells swept by the wind from the village tower. Tastes, minimal smells, sounds of the past. I'm ashamed to say so, because it's not very poetic, shall we say, but this is how it is and I can't change it: my dunked cake, my drop of perfume, my music of the wind is a prosaic and vulgar mouthful—as brief as childhood—of a Catalan beverage called Cacaolat, a mixture of milk and cocoa that I used to drink daily during morning break at school.

I only have to taste that beverage for the memories to return. But this word, Cacaolat, could not be more ridiculous and less poetic, which may explain why I have spent half my life hating writers who work with their memories, and instead defending those who without the dead weight of memories are in a position to reach their maturity more quickly. I have spent half my life defending those writers who do not live off the rents of the past, and who can demonstrate an up-to-date imagination, an imagination capable of inventing out of the present, out of nothingness itself.

Half a life boasting of finding hardly anything in my tedious childhood, just a scarf, a patio covered in snow, and not much else. Half a life congratulating myself on never having had to resort to childhood to be able to write, congratulating myself on not becoming emotional when I examined a situation from my early years. And yet all this suddenly collapsed a few months ago in Barcelona's Rovira Square, the approximate geographical center of my childhood; it collapsed when I visited this square recently to witness the filming of a sequence from Shanghai Nights, Juan Marsé's novel that Fernando Trueba was making into a film. The set designers had turned Rovira Square into what it was fifty years before. It was as if I had pressed the time machine's exact switch. Suddenly everything was the same as fifty years ago; even the posters for the double bill showing at the long-since-disappeared Rovira Cinema were the same; even the atmosphere of the air in the square struck me as identical to that of fifty years ago. I immediately understood—as when took LSD in my formative years—that Time does not exist, everything is present.

I cried, I could not hold back the tears. I cried before the unexpected return of the past. Something very similar occurs in a passage from Sebald's Vertigo. The narrator of "All'estero," a chapter in that book, travels with a friend, Clara, who succumbs to the temptation to enter the school she had been to as a child: "In one of the classrooms, the very one where she had been taught in the early 1950s, the selfsame schoolmistress was still teaching, almost thirty years later, her voice quite unchanged—still warning the children to keep at their work, as she had done then [. . .] Alone in the entrance hall, surrounded by closed doors that had seemed at one time like mighty portals, Clara was overcome by tears [. . .]. We returned to her grandmother's flat in Ottakring, and neither on the way there nor that entire evening did she regain her composure following this unexpected encounter with her past."

Here Sebald seems to be telling us that the past, all past, is still happening, surfacing, is there, doing its own thing. Without handing out a calling card or needing us to invoke it, the past, our past, is happening in the present. It's thrilling, it's terrifying. It reminds me of Emily Dickinson begging the Lord not to leave her alone down here. I believe that she sensed that we are completely alone, without anybody, in a world that is only a dark basement, where we may have been put for good. (pp. 209-13)

***

What I do remember is that I spent the whole of the outward journey to Cuenca wondering whether I should go to Matz Peak at the beginning of June to read excerpts from this diary in the open air at midnight and experience the "mountain spirit." It is, no doubt, an extravagant invitation, which has obsessed me for some time now. I can't help it. I see myself there alone, in shorts, the only foreigner surrounded by German-language writers, not understanding a word anybody says, after a journey by airplane, train, bus, and cable car. I'm sure that, if I end up going to Matz Peak, everything will be so odd, so novelesque that, on my return, I shall be able to write a fair few things about what happened to me up there. But I have one doubt. Is it worth undertaking such a long journey just to come back and relate the interminable series of strange experiences I'll have had? What if I stay at home and simply imagine them? Do I not trust in my own imagination? Must I travel so far in pursuit of real events when those I imagine on Matz Peak are bound to be superior? Or do I think that what I'll find on that peak is beyond my powers of imagination? I would love to be surprised by events, but what if I climb the peak and everything there is bland, outrageously normal: a handful of nuts in Tyrolese costume reading their rubbish at midnight in front of a few tents and seeking the mountain spirit inside a circle of torches? What if it turns out that the dull drone of the washing machine I am carefully listening to now is actually much more odd, normal, or stupid? (p. 220)

***

Every year's the same at around this time. The number of illiterates in this country is on the increase, but this seems to be unimportant, there are more and more Book Days and it's up to me to explain why we have to read. Yesterday, on the radio, I was invited to explain to listeners in two seconds why they should be encouraged to read. For them literally to be encouraged, I replied. I was going to add: and at the same time to achieve the spirit’s salvation, Musil’s ideal. I didn’t say this, it struck me as excessive and also I'd have overstepped the two-second limit.

I am no longer so rigidly literature-sick. Or, rather, I begin not to understand why I must advocate reading. Let every illiterate in this country do what he wants, of course. Besides, I hate virtually the whole of humanity and I spend the day planting mental bombs against all those businessmen who publish books, those departmental managers, market directors on the wire, and economics graduates. I plant mental bombs against them and against their disciplined followers and the rest of the world in general. So I wonder why I should lend them a hand and recommend that they read books if I only wish them ill, if I only want their stupidity to grow and for them to crash, once and for all, as they travel on the train of ignorance that we all pay for, but that one day they will pay a high price for, falling into the bottomless pit of failure, taking themselves elsewhere, into a different industry. What's more, I loathe them so much that I'd be delighted if they were obliged to read, if a perfidious decree appeared from somewhere, a drastic order to become acquainted with books, and suddenly this country's cities turned into libraries of forced, chaotic, daft intellectual activity. (pp. 220-21)

***

Preciselv because literature enables us to understand life, it tells us what can be, but also what could have been. There is nothing sometimes farther away from reality than literature, which is constantly reminding us that life is like this and the world has been organized like that, but it could be otherwise. There is nothing more subversive than literature, which aims to return us to true life by exposing what real life and History smother. Magris knows this very well, he is deeply interested in what could have been, had History or human life taken another course. Anyone who's interested in this is interested in reading. This is not advocacy. After all, there are times—like now—when I wouldn't recommend reading even to Pico's moles, even to my worst enemies. (pp. 222-23)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Enrique Vila-Matas piensa en su arte. En mi blog.

1 note

·

View note