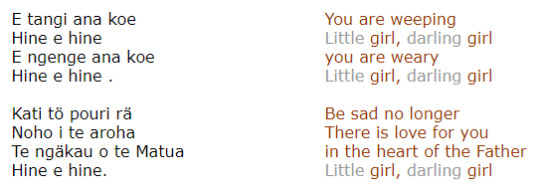

#joseph hines

Text

joseph hines photographed by @alexdrogers

#alex d rogers#joseph hines#the standard#the affluent standard#nikon#z9#nikon z9#menswear#mens fashion#style guide#style goals#well dressed men#men in suits

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bradley Joseph Clemens - Specializes In Wildlife Management

Meet Bradley Joseph Clemens, a proud multi-generation native of Harney County, Oregon. As the founder of Dry Mountain Hunting Consultants, LLC, since 2018, he specializes in wildlife management and bow hunting strategies. His dedication to the logging industry led to accolades like the 2018 Eastern Oregon Logger of The Year.

#bradley joseph clemens#bradleyjosephclemens#lifelong hunter#hunting industry#hines#works in bow hunting

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alarmed over the discovery of 215 multiracial bodies found buried in a pauper’s cemetery behind the Hinds County, Mississippi jail, Reverend Hosea Hines, senior Pastor of the Christ Tabernacle Church and the national leader of A New Day Coalition for Equity and Black America (ANCEBA), joined Attorney Ben Crump in calling for an investigation.

Some relatives of those found buried behind the jail simply thought they were missing. They object to having to pay a fee for the removal of their loved one’s remains that are needed for a proper burial.

At a press conference held on December 20 at the Stronger Hope Baptist Church in Jackson, Mississippi, Crump was joined by relatives of three of the deceased men. Each of the women held pictures of their loved ones.

Gretchen Hankins, who is white, held a picture of her son, Jonathan Hankins, 39. Mary Moore Glenn, a Black woman, held a picture of her son, Marrio Moore, 40, and Betterstem Wade held a photo of her son, Dexter Wade, 37. They were shocked to learn their relatives had been buried behind the jail.

Crump and his co-counsel, Dennis Sweet, are demanding to know why officials failed to investigate their deaths and did not try to find the next of kin, as opposed to burying them in a pauper’s grave near a dirt road by the jail work farm. Their gravesites were reportedly marked with a metal rod and a number.

“People all across America are scratching their heads in disbelief about what’s happening in Jackson, Mississippi, with this pauper’s graveyard,” said Crump.

“It went from talking about the water” that was non-existent or contaminated, “to now we’re talking about the graveyard. What is going on in Jackson, Mississippi?”

That is what Reverend Hines wants to know, as well.

In an interview with the Chicago Crusader, Hines said, “It’s unfortunate that we are living in a world that is college educated and super sophisticated as it relates to telecommunications and IT. The amount of mistakes that were made, as to individual families not being notified about the deaths, is really unbelievable.

“It really saddens my heart to know that their relatives went that long, some over a year, not knowing if their loved ones were dead or alive and then coming to the realization that they had been buried in a pauper’s grave behind a jailhouse,” Hines said. “If they had been properly notified, they would have been able to pay their proper respects.

“A lot of these things that have happened were not under the watch of Joseph Wade, the chief of the Jackson Police Department,” Hines stated. “He has instituted a new death notification policy that would give relatives information about their deaths and the cause.

“I have spoken with the chief, and he has told me he will implement policies and procedures to ensure this won’t happen again and to hold those individuals responsible for what has occurred.”

Agreeing with Attorney Crump, Hines said, “There needs to be a real call for justice” on behalf of the 215 Black, white, Hispanic and Native Americans who were buried behind the jailhouse.

Asked if he was surprised this was happening in Jackson, Mississippi, Hines said, “I am surprised that it’s happening anywhere in the U.S. We should be better than this.”

He said he does not know if the deaths of the 215 people were acts of “racism, prejudice, or bigotry.” He is also investigating the causes of their deaths.

“I give my condolences to all of the families that have been affected by this tragedy. My prayers go out and up to them, and I pray that you find the whole truth and nothing but the truth about their deaths.” Hines said he will be working to find out the truth and to give care to the grieving families.

Efforts to reach Hinds County Coroner Sharon Grisham-Stewart to determine the cause of the deaths failed. She did not respond to phone calls or emails.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview for 'Out Magazine' for Fellow Travelers (2023)

Starting in 1950, hundreds to thousands of gay men and lesbians were fired from government jobs for allegations of homosexuality under the intrusive eyes of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn. They were labeled deviants and morally weak. McCarthy and Cohn said that gay people couldn’t be trusted with your children, let alone to run your country. It’s shockingly similar to what’s happening today.

By 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which barred homosexuals from working in the federal government. Five thousand people were not just fired but were outed to their families and communities, effectively and in some cases literally ending their lives. More followed. It wasn’t until the 1970s that this policy barring gay people from federal jobs started to change, and not until 1998 that it completely ended.

In Fellow Travelers, an eight-episode series airing on Showtime this fall, actors Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey play Hawk Fuller and Tim Laughlin, two men who meet while working in Washington, D.C., at the start of McCarthyism. They fall in love. For Hawk, this means living an existence of discipline and barriers, hiding who he is so he can build a life working in the government. For Tim, it means losing his career and finding a path that allows him to follow his truth.

In order to survive, Hawk and Tim form a chosen family with two other gay men swept up in the big political and cultural changes happening: journalist Marcus Hooks (Jelani Alladin) and drag-queen-turned-activist Frankie Hines (Noah J. Ricketts). Throughout the four decades covered in the series, the four men come back into each other’s lives when things get hardest. For the four out stars of the show, forming that kind of found family was important in order to be able to play some of the most complex and challenging (but rewarding) roles of their careers. That family found its leader in Bomer, a veteran actor (Magic Mike, The Normal Heart). Bailey, an English actor with an extensive background in theater, is internationally famous as the male lead in season 2 of Netflix’s Bridgerton. Alladin (Frozen) and Ricketts (Frozen, Beautiful: The Carole King Musical) are known for their Broadway roles.

“Matt is such a giver, and he gave to all of us and provided the space for all of us to feel safe, to feel that we can make bold choices and that we can all play along,” Alladin says, thanking Bomer. “And it really connected everybody on set to say, to trust each other. Rarely do I feel like there’s a circle of four queer men or four queer bodies and I feel like we can all say, ‘I would fall on a sword for you.’”

For Bomer and Bailey, that also meant building the kind of trust that allowed them to film some sex scenes that are among the hottest in the careers of two men who have filmed a lot of heated moments. “It’s funny, isn’t it? Personally, when I read the script, I didn’t think it was explicit,” Bailey laughs. “I think it’s so important. You can’t tell the queer love story and not show how the sex is so intrinsic.”

“It’s all something that is hard to talk about to people who come together and have separate bodies,” he adds. “But if you exist in the same body, how you negotiate that and what that means, how being submissive [affects sex], and well, really what is kink…. It’s all a thing. I just think it’s a really hearty and honest examination of something which I know I’ve always yearned to see properly explored.”

Bomer says they were able to explore that because they had conversations throughout filming the scenes. “We could call audibles on the fly or really communicate with each other or say we wanted to try this or that, so it all felt pretty free,” he says. “And in terms of the story, all those scenes really carry the story forward. Their relationships are not the same after those above scenes as they were before. So they’re all intrinsic and inherent to the story.”

“I think it’s so nuanced and personal, isn’t it? The way that people have sex is so presumed,” Bailey says. “It definitely was the first time that I’ve seen a light being shown on the roles within a gay relationship and power and status with being submissive and dominant.”

“But to me, what I find interesting, it’s a give and take between the two,” he continues. “So actually it’s not one person going, ‘I’m now going to do this.’ It’s like they move as a unit. And I think that’s beautiful. And I feel like it always is negotiation, and I’m always interested in people who identify as one role, and I would wonder what that is.”

He points to the first time Hawk and Tim have sex, where Hawk takes on the dominant (top) role, and the last time, when Tim takes charge. “Literally, it’s a complete reversal,” he points out. “It’s a love story. So that bleeds into these scenes. So even in the way they have sex, it’s always about generosity and communication. And that is essentially how I feel how this whole show was made on generosity and communication and truth.”

While the sexual intimacy is groundbreaking in the show, the intimacy is there for the characters in other ways too. Because the actors played the characters throughout four decades of their lives, they were presented with a unique opportunity to showcase development — especially for Alladin and Ricketts, who know the importance of showing Black queer love on screen.

“There’s also something so powerful in telling this story to the world right now in hope of either educating or simply revealing to those who don’t understand that love can happen in all shapes, sizes, and forms, and be inside of all people,” Alladin says. “And that it should not be something that is limited by law or limited by the venom of segregation.”

“For me, some of the intimacy that I enjoy the most in this series is when we’re all old,” he continues. “Because they’re still caring for one another. I’ll never forget shooting that scene in the bedroom in one of the later episodes where we’re at age 80 and we’re still connected, we’re still loving each other. That’s something I’ve never seen — caring that lasts through decades.”

For Ricketts, playing the role of a Black gay man who is a drag performer in an illegal gay bar in the ’50s and then becomes an activist and organizer throughout the rest of his life, caused him to look at his own life and priorities.

“I think there’s something so beautiful and beautifully hard about being yourself in a world that is determined to hate you,” Ricketts says. “And playing Frankie, a character that was out and loud and proud with a glossy lip and a painted nail. It really forced me to look inward at the way I moved through the world and see if I’m coming out authentically, if I’m moving in the world authentically. And so I hope that as people watch this, they ask themselves that question so we can break down these barriers of hypermasculinity and feeling like we have to change who we are to subscribe to societal norms.”

“I think living out loud and living as an effeminate person in the world, you put on a type of armor,” he continues. “There is a lot of fear underneath that. And even though to the external world, you’re going out there being brave, what I tried to show was that it’s actually a really difficult thing to stand up and be yourself. There’s a lot of emotion underneath that. And so I think throughout the years, you beat someone down one time and you get stronger the next time. And I think that’s what you see in Frankie’s evolution.”

“It’s amazing to see how much [Frankie’s] priorities shift as the world shifts through the decades. And I think that’s what I responded to so much, is that my character Frankie gives up, puts his heels away to fight the good fight and to make a better existence for the people that come after him,” he says. “And I think that’s something that’s so real for queer people that it’s a call to action. We don’t have the luxury of hanging back. We have to fight for everything that we have.”

That fight became even more real for each of the actors the more they learned about the real Lavender Scare — the aforementioned persecution of queer people in the U.S. government — a history lesson that’s not taught in most schools. “I had no idea it was a thing, and I was embarrassed by that,” Alladin admits. “I was ashamed of that. Why was that chapter skipped in the history books? Why not in social studies class? It is 101, and here we are staring in the mirror being like, Well, did anything change? Well, no. Because we didn’t teach it. We haven’t taught it. So therefore, how can you learn the lesson?”

“I think there’s so much erasure that happens of queer history in general that I’m happy this exists because it forces people to ask the question, Did this really happen? And to seek out answers for themselves,” Ricketts adds. “And the answer is, ‘Yeah, it’s real.’ And it’s happening again today. So yeah, call to action, babies!”

“A lot of the transformations that we’ve seen in the community come from Black and brown bodies that really put themselves out on the street and out on the front lines to fight the fight. And so that’s something that I knew, but it’s amazing to see that it didn’t just happen at Stonewall, it happened in San Francisco and other places with the street queens, that they were out there really going to jail, fighting for their lives so that we could have what we have today,” he says. “And I just think it’s so beautiful to show that. I’m happy that it’s represented.”

Before the July photo shoot for this article, Alladin and Bailey had the chance to go to London Pride together, something both actors say they’ll never forget. “I think it was really crazy to have to experience Pride in New York City and to land in London and experience Pride in London and feel that it’s almost exactly the same,” Alladin says. “There’s a need to release joy. There’s a need to feel that. The world is trying to squish it out of the community with every law that’s being passed, every kind of denial of existence. And you’re like, I just want to enjoy one day.”

Bailey says that working on the show has made him more aware of the political fervor at Pride than any time he’s been previously, and it’s causing him to examine how he uses his platform to fight for LGBTQ+ rights. And Bomer also felt that this year’s Pride was a special one — particular in the wake of Supreme Court decisions that struck down affirmative action and opened the door to businesses discriminating against LGBTQ+ people.

“In light of the past week in all the Supreme Court rulings, it was so important for me personally yesterday just to go out into the streets and take in the Pride celebrations and the sense of community and hope and joy and love that everyone was feeling,” he says. “And to allow that to fill my cup a little bit and inspire me to educate myself and form myself to do what I can and keep moving forward and in the most productive way possible for our community.”

Bomer also wants to make sure he honors those who fought to get us where we are today. “I was fortunate enough to be in Houston last week for the 20th anniversary of Lawrence v. Texas [the SCOTUS ruling invalidating U.S. sodomy laws], and it was so profound for me to meet members of the community in Houston who I was totally unaware of,” he says. “There are generations of heroes who are doing the real grassroots behind-the-scenes work who don’t want accolades, who don’t want awards, who are doing the real work that’s changing all of our lives. And I think I value that today more than I ever have before.”

“For me, I think Pride is always a time to reflect on how far we’ve come but also to realize how much further we have to go,” Ricketts says. “And I think that’s what I’d say to the younger communities, is really understand and know how we got here in the first place and figure out what your form of fighting is. If it’s just showing up in the world authentically as you, that’s wonderful. If it’s getting on a podium and preaching until midnight, that’s wonderful too. But we all need each other and no one can sit back and rest. We have to keep fighting in the fight.”

Talking about queer joy as a form of activism at Pride makes Alladin think of a note he was given during filming from series creator Ron Nyswaner (Philadelphia) about the balance of difficulty and joy found in the series.

“Ron gave me a note one day,” Alladin recalls. “I texted him being like, ‘I’m watching all this research on the ’80s and the AIDS crisis and I’m just sitting here crying.’ He was like, ‘Yeah, but Jelani, I still went to birthday parties. I still found a way to play games with my friends. I still found a way to have a beer and enjoy that.’ So there is still some semblance of light being found in darkness and chaos.”

“When I was in Houston, I was at home with one of the activists and he was showing me pictures from the time period,” Bomer contributes. “And obviously, there was so much heartbreak and loss, but there was also so much celebration and so much joy. It’s really the balance.”

Source

#fellow travelers#out magazine interview 2023#out magazine#matt bomer#jonathan bailey#noah j. ricketts#jelani alladin#showtime#paramount plus#jonny bailey#noah ricketts#interviews#interviews:2023#NEW!

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pictures from our trip to Aotearoa/New Zealand 🏔️🌊🌿

Wellington Botanic Garden, Split Apple Rock in Tasman Bay, Punakaiki pancake rocks, Hokitika beach & Hokitika Gorge, Southern Alps from a helicopter tour, Franz Joseph Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere, Mirror Lakes

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

MARY LOU WILLIAMS, LA PETITE FILLE AU PIANO

"I don't like to cook, wash and iron. Since I never had it to do, why do it now?’’’

- Mary Lou Williams

Née le 8 mai 1910 à Atlanta, en Georgie, Mary Elfrieda Scruggs, dite Mary Lou Williams, était la deuxième d’une famille de onze enfants. Scruggs avait eu une enfance particulièrement difficile. Mary n’avait pas vraiment connu son père Joseph Scruggs, qui avait abandonné sa famille peu après sa naissance. Mary avait rencontré son père pour la première fois alors qu’elle était dans la vingtaine.

La mère de Scruggs, Virginia Winn, qui était alcoolique, avait subvenu aux besoins de sa famille en travaillant comme blanchisseuse. Virginia s’était remariée par la suite avec Fletcher Burley. Comme Scruggs l’avait expliqué plus tard dans une biographie qui était demeurée non publiée, sa mère avait l’habitude de jouer de l’orgue tout en la portant dans ses bras. Scruggs poursuivait: "I must have frightened her so that she dropped me then and there, and I started to cry. It must have really shaken my mother. She actually dropped me and ran out to get the neighbors to listen to me."

Vers 1914 ou 1915, Scruggs s’était installée à Pittsburgh avec sa famille. Scruggs appréciait énormément Burley, qui avait même emmené un pianiste à la maison pour lui apprendre à jouer des pièces de Jelly Roll Morton et d’autres pionniers du jazz. Scruggs expliquait: "As a stepfather he was the greatest, and he loved the blues. Fletcher taught me the first blues I ever knew by singing them over and over to me." Burley emmenait également la jeune Mary dans les bars où il se rendait pour parier, lui permettant ainsi de gagner jusqu’à 20$ en pourboires en se produisant au piano.

Élevée dans le quartier d’East Liberty, Scruggs était une véritable enfant prodige. À l’âge de seulement deux ans, Scruggs était capable de jouer des pièces simples au piano sans aucune assistance. Un an plus tard, elle avait commencé à apprendre le piano (à l’oreille) avec sa mère Virginia. Comme Scruggs l’avait expliqué plus tard, "[I had] no formal instruction. My mother wouldn't allow a teacher near me. She played by ear, then went to a teacher and ended up not playing at all, just reading music. But my mother kept me in a musical environment. Professional musicians were always coming to the house.’’

Il avait fallu très peu de temps à Scruggs pour apprendre à jouer de différents styles musicaux, du ragtime au boogie woogie en passant par le blues, les succès populaires et les airs de musique classique. Son oncle et son grand-père payaient même Scruggs pour jouer leurs chansons favorites. Peu après, des amis de la famille avaient commencé à la payer pour aller jouer dans des fêtes. Scruggs s’était produite en public pour la première fois à l’âge de sept ans.

Scruggs avait toujours joué du piano par nécessité. Ses voisins blancs avaient jeté des briques sur sa maison jusqu’à ce qu’elle accepte d’aller jouer dans leurs résidences. À l’âge de six ans, Scruggs, qui s’était fait connaître sous le surnom de “the little piano girl of East Liberty", avait contribué à la subsistance de ses frères et soeurs en allant jouer dans des soirées pour un dollar l’heure. Dans une entrevue publiée sur le site du Kennedy Center de New York, Scruggs avait raconté plus tard qu’elle avait souvent travaillé pour une riche famille de banquiers, les Mellons. Elle expliquait: "They'd send a chauffeur out for me and I'd play their private parties. Once they gave me $100. My mother almost fainted. She wanted to know if the lady drank. She even called the people to see if they had made a mistake."

Scruggs, qui avait étudié au Westinghouse Junior High School de Pittsburgh, était rapidement devenue une passionnée de jazz et écoutait sans arrêt les enregistrements des plus grands musiciens de l’époque comme Jelly Roll Morton, Earl Hines et Fats Waller.

Scruggs avait commencé sa carrière professionnelle en 1924 en participant à une tournée avec le duo Seymnour and Jeanette qui se produisait sur le circuit de vaudeville de la Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA). Particulièrement dure pour les musiciens de couleur, la TOBA avait été surnommée par dérision "Tough on Black Artists" et ‘’Tough on Black Asses.’’

Un jour, le groupe Hits and Bits devait se produire à Pittsburgh, mais le pianiste de la formation ne s’étant pas présenté, Scruggs avait été recommandée au producteur "Buzzin'" Harris. Au début, Harris croyait qu’on lui avait fait une blague, mais une fois qu’il avait entendu Scruggs jouer, il l’avait aussitôt engagée. Il l’avait aussi invitée à partir en tournée avec le groupe. D’abord réticente, après lui avoir trouvé un chaperon, la mère de Scruggs avait laissé voyager sa fille durant deux mois avec le groupe pour 30$ par semaine.

Scruggs avait mentionné la pianiste Lovie Austin comme sa principale influence.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

En 1923, Scruggs avait joué avec Duke Ellington et un de ses premiers groupes, les Washingtonians, dans le cadre d’un engagement d’une semaine au Lincoln Theater. Elle s’était également produite avec les McKinney's Cotton Pickers au Rhythm Club de Harlem. Un jour, Louis Armstrong était entré dans le club et s’était arrêté pour entendre Williams. Armstrong avait été tellement impressionné par le jeu de Williams qu’il l’avait embrassée. Comme Williams l’avait expliqué plus tard: "Louis picked me up and kissed me."

Au début de sa carrière, Williams avait fait face à la résistance de certains gérants et musiciens qui ne voulaient pas jouer aux côtés d’une femme. C’est alors qu’un saxophoniste baryton et clarinettiste du nom de John Overton Williams s’était porté à sa défense et avait obtenu l’accord des autres musiciens pour qu’elle fasse partie du groupe,.

Scruggs avait pris le nom de Williams après son mariage en novembre 1926. Au début de sa carrière, Williams avait également utilisé les noms de ses deux beaux-pères, Burley et Winn.

Williams avait rencontré Scruggs à Cleveland alors qu’il se produisait avec son groupe, les Syncopators. Après le mariage, Williams avait emmené Scruggs à Memphis, au Tennessee, où il avait formé un groupe dont sa nouvelle épouse était la pianiste. C’est dans le cadre de ce groupe que Williams avait pu jouer aux côtés de grands noms du jazz comme Jack Teagarden et Art Tatum.

En 1929, à l’âge de seulement dix-neuf ans, Williams avait assumé la direction du groupe après que son mari ait accepté une invitation de se joindre à l’orchestre d’Andy Kirk à Oklahoma City. Devenue la soliste vedette du groupe, Williams, qui était surnommée à l’époque “The Lady Who Swings the Band’’, en avait profité pour interpréter quelques-uns de ses arrangements.

Même si Williams avait éventuellement rejoint son mari à Oklahoma City, elle n’avait jamais été officiellement membre du groupe. Le groupe de Kirk, appelé les Twelve Clouds of Joy, s’était plus tard installé à Tulsa, en Oklahoma, où Williams, quand elle ne travaillait pas comme musicienne, transportait des corps pour une entreprise de pompes funèbres. Lorsque les Coulds of Joy avaient accepté un contrat à long terme à Kansas City, au Missouri, Williams s’était joint au groupe tant comme musicienne qu’arrangeuse et compositrice. Décrivant son séjour à Kansas City, Williams avait déclaré: "Kansas City in the Thirties was jumping harder than ever. The 'Heart of America' was at that time one of the nerve centres of jazz, and I could write about it for a month and never do justice to the half of it… Of course, we didn't have any closing hours in these spots. We could play all morning and half through the day if we wished to, and in fact we often did. The music was so good that I seldom got to bed before midday."

Même si elle n’était officiellement membre du groupe, Williams avait enregistré pour la première fois avec les Clouds of Joy en 1929 et 1930. Au total, Williams avait enregistré 108 de ses compositions avec le groupe.

Parmi les compositions de Williams à cette époque, on remarquait "Froggy Bottom" (qui avait été enregistrée en 1929, mais publiée seulement en 1936), "Walkin' and Swingin'" (1936), "Little Joe from Chicago", "Roll 'Em" (qui était devenu son plus grand succès avec l’orchestre de Benny Goodman), “What’s Your Story, Morning Glory” (avec l’orchestre de Jimmie Lunceford), "Moten Swing" (1936), “Steppin’ Pretty”, "Twinklin'", "In the Groove" (1937), “Big Jim Blues”, "Lotta Sax Appeal", ‘’Messa Stomp’’ (1929 et 1938) et "Mary's Idea" (1938). Williams avait aussi été l’arrangeuse et la pianiste du groupe dans le cadre d’enregistrements à Kansas City (1929) Chicago (1930) et New York (1930). En fait, la contribution de Williams dans le groupe de Kirk était si importante que le Pittsburgh Courier avait écrit qu’elle était responsable ‘’or many of the unusual arrangements used by the band in playing their hit numbers". Toujours interprétée par les big bands de nos jours, la pièce "Walkin' and Swingin'’’ avait même servi d’inspiration à Thelonious Monk dans l’écriture de son célèbre "Rhythm-A-Ning." C’est d’ailleurs Williams qui avait présenté à Monk la légendaire baronne Pannonica de Koenigswarter, une mécène qui était éventuellement devenue sa protectrice ainsi que celle de Charlie Parker.

Durant la crise des années 1930, le groupe de Kirk ayant moins d’occasions de voyager et d’enregistrer, Williams en avait profité pour peaufiner son style, apprendre la théorie avec Kirk et participer à des jam sessions avec de grands noms du jazz comme Lester Young et Ben Webster. Écrivant de cinq à six arrangements par semaine à l’époque, Williams passait la majeure partie de ses nuits à composer. Comme Williams l’avait déclaré dans la biographie Morning Glory publiée par Linda Dahl en 1999: "I always liked lying flat on my back on the grass in Paseo Park in Kansas City, looking up at the stars, composing, late at night."

À l’hiver 1930-31, Williams s’était rendue à Chicago pour enregistrer ses premières pièces de piano solo, "Drag 'Em" et "Night Life" (ella n’avait jamais été payée pour les sessions). D’abord simplement appelée ‘’Mary’’, Williams avait commencé à utiliser le prénom de Mary Lou sur la recommandation de Jack Kapp des disques Brunswick. Les disques du groupe s’étaient très bien vendus, ce qui avait fait de Williams une grande vedette. Peu après la session d’enregistrement, Williams était devenue la seconde pianiste attritrée du groupe. En plus de jouer en solo, Williams avait travaillé comme arrangeuse à son compte, collaborant notamment avec Earl Hines, Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington (pour lequel elle avait écrit un total de quarante-sept arrangements), Cab Calloway et Tommy Dorsey, contribuant ainsi à créer ce qu’on avait appelé le style de Kansas City. Comme Williams l’avait expliqué au cours d’une entrevue au magazine Melody Maker:

"By now I was writing for some half-dozen bands each week. One week I was called on for twelve arrangements, including a couple for Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines, and I was beginning to get telegrams from Gus Arnheim, Glen Gray, Tommy Dorsey and many more like them. As we were making perhaps 500 miles per night, I used to write in the car by flashlight between engagements. The band parts too... Whenever musicians listened to the band they would ask who made a certain arrangement. Nearly always it was one of mine."

En fait, Williams était si prolifique que plusieurs de ses arrangements n’avaient jamais été enregistrés. Plusieurs autres avaient aussi été perdus.

Après avoir enregistré ‘’In the Groove’’ en 1937 avec la collaboration de Dick Wilson, Williams avait été contactée par Benny Goodman qui lui avait demandé d’écrire une chanson de blues pour son orchestre. Williams avait finalement composé "Roll 'Em", un boogie woogie basé sur le blues. Williams avait aussi connu un grand succès avec la pièce "Camel Hop", dont le titre faisait référence au commanditaire de l’émission de radio de Goodman, les cigarettes Camel. Goodman avait tenté de faire signer un contrat à Williams pour la forcer à écrire exclusivement pour lui, mais elle avait décliné la proposition, car elle désirait conserver son indépendance. Devenue un des meilleurs ‘’arrangeurs’’ de jazz tout sexes confondus en 1938, Williams avait inspiré le commentaire suivant à un critique du New York Amsterdam News: "Miss Williams is considered swing music's only top arranger, a field she takes to with much alacrity because she likes the work.’’

Malgré toute sa notoriété, Williams avait commencé à réaliser à la fin des années 1930 qu’elle ne serait jamais rétribué à sa juste valeur comme arrangeuse et compositrice. Comme elle l’avait expliqué au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine Melody Maker en 1954: ‘’By the late 1930s she had come to expect that she would not be paid fairly, if at all, for many of her arrangements. "I had begun to think my arrangements were not worth much, as no one ever wanted to pay for them, and Andy, I knew, could not afford a proper arranger's fee. But the work paid off in the long run. Whenever musicinas listened to the band they would ask who made a certain arrangement. Nearly always it was one of mine.’’

De plus en plus désabusée, Williams avait commencé à perdre tout intérêt pour son métier. Elle précisait: ‘’Sometimes I sat on the stand working crossword puzzles, only playing with my left hand. Every place we played had to turn people away, and my fans must have been disappointed with my conduct. If they were, I wasn't bothering at the time." Williams était demeurée avec le groupe de Kirk de 1929 à 1942. En plus de jouer du piano de composer et d’écrire des arrangements, elle avait fait plus de 180 enregistrements avec le groupe. En 1940, Williams avait également arrangé et enregistré les pièces "Baby Dear" and "Harmony Blues" avec un groupe connu sous le nom de Mary Lou Williams and Her Kansas City Seven, qui était composé de membres de l’orchestre de Kirk.

En 1942, Williams, qui venait de divorcer de John Williams, avait quitté les Twelve Clouds of Joy et était retournée à Pittsburgh où ella habité avec sa soeur durant un certain temps. En Pennsylvanie, Williams avait été rejointe par son collègue Harold "Shorty" Baker, avec qui elle avait formé un groupe de six musiciens qui comprenait le jeune Art Blakey à la batterie. À la même époque, Williams avait également formé un groupe entièrement féminin qui comprenait notamment la guitariste Mary Osborne.

Après s’être produite à Pittsburgh, Baker avait finalement quitté le groupe pour se joindre à l’orchestre de Duke Ellington comme chanteuse. En 1943, Williams avait rejoint le groupe à New York, avant de se rendre à Baltimore, où elle avait finalement épousé Baker. Après avoir commencé à voyager avec l’orchestre d’Ellington, Williams avait écrit plusieurs arrangements pour le groupe, dont "Trumpet No End" (1946), sa version de la chanson ‘’Blue Skies’’ d’Irving Berlin. Williams avait aussi remporté un grand succès en interprétant la chanson "Walkin' and Swingin'". Au bout d’un an, Williams avait quitté Baker et le groupe d’Elllington et était retournée à New York.

Après avoir signé un contrat avec Moses Asch, le propriétaire et producteur de Asch Records, Williams avait enregistré plus de cinquante pièces de 1944 à 1947 avec différentes compagnies d’enregistrement. En 1944, Williams avait participé à six sessions d’enregistrements avec de grands noms du jazz comme Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas, Vic Dickenson, Bill Coleman, Edmond Hall, Frank Newton et Josh White. Deux ans plus tard, elle avait enregistré un album solo. Après avoir accepté un contrat au Café Society Downtown, le premier club multiracial de New York, Williams avait commencé à animer sa propre émission de radio hebdomadaire appelée Mary Lou Williams's Piano Workshop. Williams avait aussi commencé à parrainer et à collaborer avec de jeunes musiciens de bebop comme Bud Powell, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker et Thelonious Monk.

Fascinée par le bebop, Williams avait écrit plusieurs compositions influencées par le nouveau style musical, dont “Tisherone”, “Knowledge”, “Lonely Moments” et “Waltz Boogie.” Cette dernière pièce avait d’ailleurs été enregistrée en 1946 par un des groupes féminins de Williams, les Girl-Stars. En 1945, Williams avait également composé la pièce à succès "In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee" pour Gillespie. L’appartement de Williams était aussi devenu le lieu de rendez-vous de plusieurs musiciens comme Erroll Garner, Phineas Newborn, Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Elmo Hope et Thelonious Monk. Comme Williams l’avait expliqué plus tard au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine Melody Maker, "During this period Monk and the kids would come to my apartment every morning around four or pick me up at the Café after I'd finished my last show, and we'd play and swap ideas until noon or later". En 1947, Williams avait finalement publié un premier album de bebop avec le trompettiste Kenny Dorham. Elle avait aussi composé deux pièces d’inspirations bop pour Benny Goodman.

Toujours en 1945, Williams avait composé la Zodiac Suite, une pièce très influencée par la musique classique. Comme son titre l’indiquait, chacune des douze parties de la suite correspondait à un signe du Zodiaque et était dédiée à un de ses partenaires musicaux, dont Billie Holiday et Art Tatum. Pour sa part, le mouvement ‘’Capricorn’’ avait été écrit en l’honneur de Pearl Primus, une danseuse qui avait travaillé avec Williams au Cafe Society. La danseuse Katherine Dunham avait plus tard chorégraphié une danse sur le mouvement ‘’Scorpio.’’ Enregistrée avec Jack Parker et Al Lucas, la suite avait été interprétée à Town Hall le 31 décembre 1945 par le New York Philharmonic Orchestra et le saxophoniste Ben Webster. En 1947, Williams était retournée à New York où elle avait animé sa propre émission de radio appelée le Mary Lou Williams’s Piano Workshop.

En 1952, après avoir accepté une offre de se produire en Angleterre, Williams était demeurée en Europe durant deux ans, faisant notamment un long séjour en France dans le cadre d’engagements au Boeuf sur le Toit et dans un club qui avait été baptisé en son honneur, Chez Mary Lou. Au cours de son séjour en Europe, Williams avait fait une tournée sur le continent et avait enregistré avec six compagnies de disques différentes.

Épuisée tant psychologiquement que physiquement, Williams avait finalement décidé de se retirer et de passer à autre chose. Le retrait de Williams de la scène pouvait également avoir été causé en partie par la mort en 1955 de son ami et protégé Charlie Parker, qui avait combattu sa dépendance envers les narcotiques durant la majeure partie de son existence.

Après s’être retirée du jazz durant trois ans, Williams s’était produite à Paris en 1954. Après être retournée aux États-Unis, Williams, qui avait été élevée dans la religion baptiste, s’était convertie au catholicisme en 1957 aux côtés de l’épouse de Dizzy Gillespie, Lorraine. En plus de passer plusieurs heures à l’église, Williams avait consacré la plus grande partie de son énergie à s’impliquer dans la Bel Canto Foundation, une oeuvre qu’elle avait créée à ses propres frais en 1957 et qui avait pour but d’aider les musiciens aux prises avec des problèmes de dépendance à relancer leur carrière. Williams avait même transformé son appartement d’Hamilton Heights en maison de transition. Elle avait aussi ouvert un centre d’épargne afin de financer sa maison de transition, consacrant jusqu’à même 10% de ses propres revenus à son financement.

Les pères John Crowley et Anthony avaient finalement réussi à persuader Williams de retourner vers la musique en 1957 en lui disant qu’elle pouvait continuer de servir Dieu et l’Église catholique en utilisant son don exceptionnel pour la musique. Quant à Dizzy Gillespie, il avait convaincu Williams de faire un retour avec son groupe au Festival de jazz de Newport en 1957. Williams avait également continué de faire la promotion du jazz et avait commencé à sensibiliser les jeunes Afro-Américains à cette partie importante de leur héritage. Elle avait aussi fait plusieurs apparitions sur des émissions de télévision comme The Today Show” et “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

Compositrice d’une grande polyvalence, Williams s’intéressait tout aussi au jazz modal qu’au blues et à la musique classique. Décrivant sa collaboration avec Williams dans le cadre de l’enregistrement de l’album Free Spirits en 1975, le producteur Nils Winther avait commenté: "She was an unusually kind and serious person. She was very religious {...}. She was very serious. She recorded many takes before she was satisfied {...}. The musicians were the ones she worked with and the choice of tunes was largely hers, with a few suggestions from me. Mary Lou was happy with the artistic freedom she got on the recording. I left the choice of repertoire and choice of musicians up to her, as I think it should always be, by the way. {...}. I think it's a very fine release, and I'm very happy that I had the opportunity to record this huge jazz musician."

Le Père Peter O’Brien était devenu l’ami et le gérant de Williams dans les années 1960. O’Brien avait également présenté Williams à l’évêque de Pittsburgh, John Wright. O’Brien avait aussi aidé Williams à se trouver de nouvelles salles où se produire à une époque où seulement deux clubs de Manhattan offraient des concerts de jazz à plein temps. À partir de la fin des années 1950, Williams avait participé à de nombreuses tournées et présenté plusieurs concerts, notamment dans le cadre d’une performance à Pittsburgh avec les pianistes Willie "The Lion" Smith, Duke Ellington, Earl Hines et Billy Taylor en 1965.

En plus de travailler dans les clubs, Williams avait joué dans les clubs, fondé le Festival de jazz de Pittsburgh (1964) et fait des apparitions à la télévision. Quant à l’évêque Wright, il avait permis à Wilson d’enseigner au Seton High School situé dans le North Side. C’est là que Williams avait écrit sa première messe appelée The Pittsburgh Mass. La pièce était basée sur un hymne composé en l’honneur du saint péruvien Martin de Porres qui venait d’être canonisé par le pape Jean XXIII la même année. Williams avait également écrit deux autres de plus courte durée, Anima Christi et Praise the Lord. La messe avait été interprétée pour la première fois en novembre 1962 à l’église St. Francis Xavier de Manhattan. Williams avait enregistré l’oeuvre en octobre de l’année suivante. Williams était éventuellement devenue la première compositrice de jazz à obtenir une commande de l’Église pour écrire de la musique liturgique influencée par le jazz.

EDERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Dans les années 1960, Williams avait continué de sa concentrer sur la composition de musique sacrée, d’hymnes et de messes. Elle était d’ailleurs devenue une pionnière du jazz dit ‘’spirituel’’ qui avait été plus tard popularisé par des musiciens comme John Coltrane, entre autres. L’une de ces messes était Music for Peace, qui avait été chorégraphiée par Alvin Ailey et présentée au Alvin Ailey Dance Theater sous le titre de Mary Lou's Mass en 1971. Ailey avait éventuellement déclaré au sujet de l’oeuvre qui était commanditée par le Vatican: "If there can be a Bernstein Mass, a Mozart Mass, a Bach Mass, why can't there be Mary Lou's Mass?" Williams avait interprété une nouvelle version de la messe sur le The Dick Cavett Show en 1971. Parmi les autres oeuvres de musique religieuse composées par Williams, on remarquait la cantate Black Christ of the Andes (1962), un nouvel hommage au père afro-péruvien St. Martin de Porres, et Mass for the Lenten Season (1968).

Williams avait aussi consacré énormément d’efforts à enseigner à des chorales de jeunes. La "Mary Lou's Mass" avait éventuellement été interprétée à la St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City en avril 1975 devant une foule de plus de trois mille personnes.

C’était la première fois de l’histoire qu’un musicien de jazz se produisait dans cette église. Comme l’écrivait un article du magazine Time en 1964, "Mary Lou thinks of herself as a 'soul' player — a way of saying that she never strays far from melody and the blues, but deals sparingly in gospel harmony and rhythm. 'I am praying through my fingers when I play,' she says. 'I get that good "soul sound", and I try to touch people's spirits.'" Lorsque certains croyants s’étaient objectés à la célébration de la messe, Williams avait rétorqué que le jazz était une forme sacrée de la culture afro-américaine. Comme Williams l’avait déclaré au cours d’une entrevue accordée au New York Post, "Americans don't realize how important jazz is. It's healing for the soul. It should be played everywhere — in churches, nightclubs, everywhere. We have to use every place we can."

Williams s’était également produite au Festival de jazz de Monterey en 1965. En 1964, Williams était devenue la première femme à créer sa propre maison de disques, Mary Records. C’est avec cette compagnie que Williams avait publié plusieurs de ses albums des années 1970, dont son célèbre Black Christ of the Andes.

La carrière de Williams avait connu son apogée dans les années 1970. De 1971 à 1978, Williams avait enregistré huit albums, dont un enregistrement au piano solo. Elle avait également participé à l’album The History of Jazz, un enregistrement qui était une combinaison de musique et de témoignages qui avaient pour but de renseigner les auditeurs sur l’évolution du jazz. Williams avait aussi participé à la distribution de “Tree of Jazz’’, une illustration de l’artiste David Stone Martin qui retraçait l’histoire de la musique afro-américaine du swing au bebop en passant par les Negro spirituals. Décrivant l’importance des Spirituals dans l’histoire du jazz, Williams avait commenté: ‘’From suffering came the Negro spirituals, songs of joy, and songs of sorrow. The main origin of American Jazz is the spiritual. Because of the deeply religious background of the American Negro, he was able to mix this strong influence with rhythms that reached deep enough into the inner self to give expression to outcries of sincere joy, which became known as Jazz’’. Témoignant dans le cadre du documentaire de Joanne Burke ‘’Mary Lou Williams: Music on My Mind’’ en 1990, Williams avait ajouté: "There have been four important periods in this wonderful music: spirituals, ragtime, Kansas City swing, and the bop era. All the music is healing and spiritual."

Williams s’était de nouveau produite au Festival de jazz de Monterey en 1971. Elle avait également joué au club The Cookery, un nouvel établissement dirigé par l’ancien gérant du Café Society, Barney Josephson. Le concert avait été enregistré. Le 17 avril 1977, Williams s’était aussi produite en duo avec le pianiste d’avant-garde Cecil Taylor à Carnegie Hall. Le concert avait été publié sur l’album Embraced. Même si les avis avaient été partagés au sujet du concert, Williams n’avait pas hésité à relever le défi. Comme elle l’avait déclaré après le concert: "Now I can really say that I have played it all." Pour sa part, le pianiste et compositeur danois Jacob Anderskov avait commenté après le concert: "My first encounter with Mary Lou William's music was on the iconic, but also for her atypical, record with her and Cecil Taylor together. I later read that she was frustrated with this collaboration, and the record is perhaps not the best place to start for several reasons. On the other hand, it is a unique documentation of an extremely interesting frontal clash between two great musicians, each from a different aesthetic, and each from a different generation."

Également enseignante, Williams avait commencé par donner des cours de jazz aux enfants avant de se joindre à l’University du Massachusetts à Amherst en 1975. De 1977 à 1981, Williams avait occupé un poste d’artiste-en-résidence à l’Université Duke, où elle avait enseigné l’histoire du jazz avec le Père O’Brien tout en dirigeant le Duke Jazz Ensemble. Au cours de cette période, Williams avait également présenté de nombreux concerts et fait des apparitions dans plusieurs festivals de jazz. En 1978, elle s’était aussi produite à la Maison-Blanche devant le président Jimmy Carter et ses invités. La même année, Williams avait également participé à un concert-hommage à Benny Goodman dans le cadre du 40e anniversaire du légendaire concert de Carnegie Hall.

Williams avait enregistré son dernier album au Festival de jazz de Montreux en 1978, un concert en solo comprenant un medley de spirituals, de ragtime, de blues et de swing. Les autres faits saillants du concert incluaient de nouvelles versions des standards "Tea for Two" et "Honeysuckle Rose", ainsi que ses compositions "Little Joe from Chicago" et "What's Your Story Morning Glory". Parmi les autres pièces interprétées lors du concert, on remarquait un medley comprenant les classiques ‘’The Lord Is Heavy", "Old Fashion Blues", "Over the Rainbow", "Offertory Meditation", "Concerto Alone at Montreux" et "The Man I Love". En 1980, Williams avait créé la fondation qui porte son nom, la Mary Lou Williams Foundation. L’organisme avait pour but de faire la promotion de l’oeuvre de Williams et de faire connaître le jazz aux enfants.

Refusant de ralentir, Williams avait maintenu un train d’enfer jusqu’à l’automne 1980. Clouée au lit par un cancer au cours des derniers mois de sa carrière, elle avait cependant continué de composer. La dernière composition de Williams était demeurée inachevée. Intitulée ‘’The History of Jazz’’, l’oeuvre comprenait 55 instruments à vent, trois pianos et un orchestre de chambre.

Mary Lou Williams est morte d’un cancer de la vessie à Durham, en Caroline du Nord, quelques semaines après son 71e anniversaire de naissance. Parmi les artistes qui avaient assisté à ses funérailles à l’église de St. Ignatius Loyola (c’est également là qu’elle avait été baptisée), on remarquait ses anciens patrons Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman et Andy Kirk. Williams a été inhumée au Calvary Catholic Cemetery de Pittsburgh. Des extraits de la Mary Lou’s Mass avaient été interprétés au cours de la cérémonie. Gillespie avait également interprété quelques pièces.

Dressant le bilan de sa carrière, Williams avait déclaré quelques temps avant sa mort: "I did it, didn't I? Through muck and mud." Surnommée "the first lady of the jazz keyboard", Williams avait été une des premières femmes à connaître du succès comme musicienne de jazz et avait servi de modèle à plusieurs artistes. Lorsqu’on avait demandé Williams pourquoi elle avait persisté à travailler dans un domaine aussi largement dominé par les hommes, elle avait répondu avec humour: "I don't like to cook, wash and iron. Since I never had it to do, why do it now?’’’

Williams avait également fait partie des trois seules musiciennes de jazz à avoir été immortalisées dans le cadre de la célèbre photographie d’Art Kane intitulée ‘’A Great Day in Harlem’’ (1958). Les deux autres femmes étaient la pianiste Marian McPartland et la chanteuse Maxine Sullivan. Un mois après la mort de Williams, des musiciens s’étaient réunis à New York dans le cadre d’un concert-hommage qui avait pour but d’amasser des fonds pour donner des cours de jazz aux jeunes musiciens de talent.

Mary Lou Williams avait remporté de nombreux honneurs au cours de sa carrière. Lauréate de bourses de la fondation Guggenheim en 1972 et 1977, Williams s’était méritée en 1981 le Duke University's Trinity Award pour les services qu’elle avait rendus à l’institution. Le prix avait été accordé à Williams à l’issue d’un vote des étudiants de l’université. En 1983, l’Université Duke avait également rendu hommage à Williams en établissant le Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture.

Williams avait également décroché des doctorats honorifiques de l’Université de Boston, de l’Université Fordham de New York (1973), de l’Université Loyola et du Rockhurst College de Kansas City (1980). Williams a été admise au Down Beat Hall of Fame en 1990, devenant ainsi la première musicienne de jazz à remporter cet honneur.

Williams avait aussi été mise en nomination au gala des prix Grammy en 1971 pour l’album Giants qu’elle avait enregistré avec Dizzy Gillespie et Bobby Hackett. Depuis 1996, le Kennedy Center de Washington, D.C. tient un festival annuel exclusivement consacré au jazz féminin sous le nom de Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival. L’État de Pennsylvanie a rendu hommage à Williams en faisant installer une plaque au 328, de l’Avenue Lincoln, à Pittsburg, afin de témoigner de ses réalisations et d’indiquer l’emplacement de l’école où elle avait étudié. La ville de Kansas City, au Missouri, a également créé la Mary Lou Williams Lane en l’honneur de Williams.

Les archives de Williams sont conservées depuis l’an 2000 au Rutgers University's Institute of Jazz Studies de Newark, au New Jersey. En 2013, l’American Musicological Society avait publié l’ouvrage Mary Lou Williams' Selected Works for Big Band, une compilation comprenant onze de ses compositions pour grand orchestre.

Plusieurs musiciens de jazz avaient également rendu hommage à Williams. En 2000, le trompettiste Dave Williams avait publié l’album ‘’Soul on Soul’’ qui comprenait de nouveaux arrangements de ses compositions ainsi que des oeuvres inspirées de son travail. La même année, le pianiste John Hicks avait enregistré l’album ‘’Impressions of Mary Lou’’ qui mettait en vedette huit des compositions de Williams. En 2005, le Dutch Jazz Orchestra avait enregistré l’album ‘’Lady Who Swings the Band’’ qui comprenait plusieurs compositions inédites de Williams. L’année suivante, le Mary Lou Williams Collective dirigé par la pianiste Geri Allen avait publié l’album Zodiac Suite: Revisited.

L’autrice Sarah Bruce Kelly avait également rendu hommage à Williams dans son roman biographique Jazz Girl. Publié en 2010, le roman évoquait les premières années de la carrière et de la vie de Williams. La même année, Ann Ingalls et Maryann MacDonald avaient aussi rendu hommage à Williams dans un livre pour enfants intitulé ‘’The Little Piano Girl.’’ L’ouvrage était accompagné d’illustrations de Giselle Potter. La poétesse Yona Harvey avait également publié en 2013 un recueil inspiré de la vie de Williams et intitulé Hemming the Water. Le recueil comprenait notamment le poème "Communion with Mary Lou Williams".

Reconnue pour sa beauté, Williams avait souvent eu des relations torrides avec les musiciens qui l’avaient accompagnée, dont Ben Webster et Don Byas. Même si le tromboniste Jack Teagarden lui avait proposé de l’épouser plusieurs fois, elle ne s’était jamais remariée. Les relations de Williams avec l’agent de Louis Armstrong, Joe Glaser, avaient également été confrontées à certaines difficultés, parfois en raison de son propre tempérament. Glaser et Benny Goodman avait d’ailleurs fait preuve d’énormément de patience envers Williams, qui était reconnue à l’époque pour se dérober à ses obligations contractuelles. Même si Glaser avait souvent tenté de ramener Williams à la raison, cela avait été souvent inutile. Williams avait même quitté Goodman en plein milieu d’une session d’enregistrement à la fin des années 1940.

En 2015, la réalisatrice et productrice Carol Bash avant rendu hommage à Williams dans le documentaire intitulé ‘’Mary Lou Williams: The Lady Who Swings the Band.’’ Présenté en grande première à la télévision publique, le film avait été projeté par la suite dans plusieurs festivals de cinéma à travers le monde. En 2018, le podcast historique What'sHerName avait rendu hommage à Williams dans un épisode intitulé "THE MUSICIAN Mary Lou Williams" qui comprenait une apparition de la réalisatrice et productrice Carol Bash. En 2021, le Umlaut Big Band avait publié ‘’Mary's Ideas’’, un double CD comprenant plusieurs archives rares et inédites tirées de la collection personnelle de Williams. L’album incluait également des arrangements et des compositions de Duke Ellington et Benny Goodman, des extraits de la Zodiac Suite et de l’History of Jazz for Wind Symphony, la dernière composition inachevée de Williams. Mary Lou Williams a écrit des centaines de compositions au cours de sa carrière. Elle a également enregistré plus de 100 albums.

Décrivant l’originalité de Williams comme compositrice, l’ancien éditeur du magazine Metronome, Barry Ulanov, écrivait: "One of the difficulties about jazz is that it's very hard to notate it, but Duke Ellington could and so could Mary. She had discovered, because of her particular genius, a way to articulate on paper a jazz pattern—how to accent a measure. And that's why her best stuff is among the best in jazz." Rendant hommage à Williams, le critique Glenn Griffin du Denver Post avait ajouté qu’elle avait été la première, ‘’for a long time the only, and many claim the most significant, woman in jazz between the era of the '20s and her death in 1981." Saluant la contribution de Williams à l’histoire du jazz, Duke Ellington avait commenté: ‘’Mary Lou Williams is perpetually contemporary. Her writing and performing are and have always been just a little ahead and throughout her career . . . her music retains--and maintains--a standard of quality that is timeless. She is like soul on soul."

Le père jésuite Peter F. O’Brien, qui connaissait Williams depuis 1964, avait été son gérant de l’automne 1970 à sa mort en 1981. Devenu directeur exécutif de la Mary Lou Williams Foundation après la mort de Williams, O’Brien était également pasteur de la Resurrection Parish de Jersey City, au New Jersey.

Même s’il n’avait jamais dirigé son propre big band et n’avait enregistré que de façon sporadique comme leader, Mary Lou Williams est considérée comme une des musiciennes les plus importantes de l’histoire du jazz.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Famous 1868 births.

Snitz Edwards (Hungarian-American actor)

Maxine Elliott (American-French actress & businesswoman)

Joseph Cawthorn (American actor)

George Arliss (British actor)

Emperor Nikolai II Of Russia (last Russian emperor)(pictured)

Gen. John L. Hines (American army general)

Capt. Robert Scott (British naval captain & explorer)(pictured)

Fr. Prof. Theodor Wulf (German Catholic priest & physicist)

John T. Raulston (American judge)

Leila Dalton aka Marie Dressler (Canadian-American actress)(pictured)

Dr. Korbinian Brodmann (German neurologist)

Scott Joplin (American composer & pianist)

Eugenie Besserer Hegger (French-American actress)

#Religion#Celebrities#Movies#Hungary#Maine#France#New York City#New York#U.K.#Politics#Russia#West Virginia#Washington D.C.#Boats#Germany#Tennessee#Canada#Ontario#Music#Texas#Awesome

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1776 role swap:

Daniel Keyes: John Adams

Roy Poole: Benjamin Franklin

Jonathan Moore: Thomas Jefferson

Donald Madden: John Hancock

David Ford: John Dickinson

Ralston Hill: Richard Henry Lee

Ronald Holgate: Charles Thomson

Charles Rule: Edward Rutledge

Howard Caine: Samuel Chase

Patrick Hines: Dr. Josiah Bartlett

James Noble: Roger Sherman

Rex Robbins: Rev. John Witherspoon

Ken Howard: Dr. Lyman Hall

John Myhers: Col. Thomas McKean

Ray Middleton: Robert Livingston

Leo Leyden: Lewis Morris

Emory Bass: George Read

Howard da Silva: Stephen Hopkins

William Hansen: Joseph Hewes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

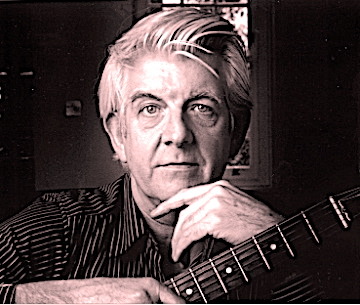

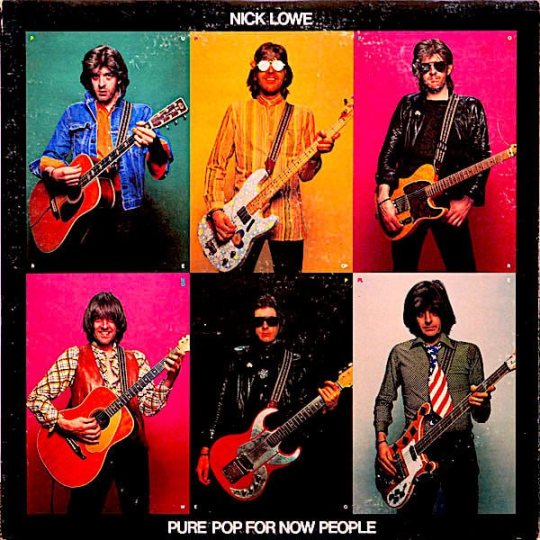

HAPPY BIRTHDAY to pedal steel guitarist Joe Alterio, composer John Antes, Dave Appell, Roscoe Arbuckle, J.S. Bach’s BRANDENBURG CONCERTOS (1721), Joseph Barbera, the 1980 Beatles RARITIES LP, Beethoven’s MISSA SOLEMNIS (1824), Laura Flynn Boyle, Sharon Corr, Don Covay, Fanny Crosby “Queen of Gospel Songwriters,” Klaus Dinger (Kraftwerk), Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gorgeous George, the 1988 musical GOSPEL AT COLONUS, civil rights activist Dorothy Height, Connie Hines (Mr. Ed), Patterson Hood (Drive By Truckers), Harry Houdini, Yanks Janis, Carol Kaye, Mike Kellie (Spooky Tooth), Krisdayanti, Kelly LeBrock, Pacemaster Mase (De La Soul), Steve McQueen (got that song waiting for you), Malcolm Muggeridge, Nivea, Lee Oskar, Paradox Thought, Joseph Priestley, cellist Hank Roberts, Klavdiya Shulzhenko, Billy Stewart, Dorothy Stratton, Sylvester the Cat, Dougie Thompson (Supertramp), Fred Vail, Boogie Bill Webb, Tommy Wilson, and the great singer-songwriter, producer, and entertainer Nick Lowe. If you collected all the recordings he’s produced, played on, and/or wrote songs for (plus the cover versions), you’d have an amazing, well-rounded record library par excellente. He’s intersected with Johnny Cash, Elvis Costello, Dave Edmunds, and a galaxy of other notables. Seeing him with Rockpile (twice) left an indelible impression on me in terms of stage presence and entertainment value. When his PURE POP FOR NOW PEOPLE LP came out, it became required listening in my social circle. I read that Nick never does live performances of his song “I Love the Sound of Breaking Glass” (allegedly a comeback to a Blondie song). So here’s my take of it, live at the Cellblock (opening for The Badlees). Meanwhile, HB Nick!

#nicklowe #breakingglass #johnnyjblair #singeratlarge #thebadlees #cellblock #williamsportPA #concert #soloacoustic #blondie #elviscostello #johnnycash #daveedmunds #rockpile

#Nick Lowe#breaking glass#Johnny J Blair#singer songwriter#singer at large#The Badlees#Cell Block#Williamsport#Pennsylvania#Blondie#Elvis Costello#Johnny Cash#Dave Edmunds#Rockpile#Bandcamp

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A GOOD PERSON (2023)

Starring Florence Pugh, Morgan Freeman, Chinaza Uche, Celeste O'Connor, Molly Shannon, Zoe Lister-Jones, Nichelle Hines, Toby Onwumere, Ignacio Diaz-Silverio, Oli Green, Alex Wolff, Brian Rojas, Ryann Redmond, Sydney Morton, Mike Menendez, Chip Hamilton, Drew Gehling, Dudney Joseph Jr., Mark Thudium, Victor Cruz, Jessie Mueller, Emilia Suárez and Anthony Cedeño.

Screenplay by Zach Braff.

Directed by Zach Braff.

Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 129 minutes. Rated R.

The title A Good Person carries a certain amount of baggage. After all, all of the characters in this well-meaning, if sometimes slightly manipulative drama, are basically good people, although they all have flaws.

I believe the specific good person in the title is supposed to be Allison (Florence Pugh), a twenty-something pharmaceutical rep who has a tragic accident which not only kills two people but ends up destroying her engagement and causing her to become addicted to Oxycontin.

I say I believe it’s supposed to be her, I guess, because the description just as easily fits Daniel (Morgan Freeman), a retired cop and ten-years-sober alcoholic whose daughter was killed in the accident, and now is struggling to care for his granddaughter.

It would also be a fitting way to refer Nathan (Chinaze Uche), Allison’s former fiancé who watched the accident not only kill his sister and brother-in-law, but also destroy the life of the woman he loves. (Allison broke off the engagement, not Nathan.)

Or it could even be Ryan (Celeste O’Connor), the granddaughter who lost her parents and now is trying to come up with the empathy to forgive the woman responsible for their death.

Like I said, they’re all good people. Good, imperfect people. Which may be the point.

A Good Person is sweet and messy and tragic and sometimes a little schmaltzy, much like life.

The film is the return to the New Jersey roots of writer/director Zach Braff, who is perhaps better known as a light comic actor (Scrubs, and more recently a ubiquitous series of T-Mobile commercials), nearly two decades after his filmmaking debut with Garden State.

Garden State has had a weird trajectory over the years. When it was originally released, it was an acclaimed arthouse hit. However, over the years a massive backlash has formed on the film, to the point that it now is pretty much mocked and despised. I come down somewhere in the middle – when it first came out, I didn’t think it was as good as so many said, but it’s also in no way the embarrassment that so many say now.

A Good Person is not likely to excite so much passion – either in the positive or the negative.

Yet, in several ways it is rather similar to the earlier film. Like that film, the female lead is “manic-pixie-dream-girl” adjacent, although one who in the long run has been cowed by tragedy and medical and psychological problems. Braff, a New Jersey native, also still does have a firm grasp on the people and places of the Garden State.

Also like Garden State the storyline pulls on the heartstrings, sometimes shamelessly.

However, the acting is rather terrific, particularly by Freeman, who is a welcome presence in one of his too few current leading roles, and Uche as perhaps the most grounded person there, who is trying to keep the fraying relationships and people around him from falling apart.

Pugh is mostly sympathetic in a much more difficult role. Sometimes you don’t totally buy her as an oxy addict, but otherwise she negotiates the bombshells that the script throws at her with confidence and aplomb.

But whoever it was who thought it was a good idea to give Molly Shannon a somewhat dramatic role as Allison’s worried mother… no. Just no.

Still, even though the audience feels slightly manipulated, A Good Person often works.

It’s a good movie. Not a great one, mind you. But like the good people it is portraying, greatness is something it can aspire to.

Jay S. Jacobs

Copyright ©2023 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved. Posted: March 24, 2023.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

joseph hines photographed by @alexdrogers

#alex d rogers#joseph hines#the standard#the affluent standard#nikon#z9#nikon z9#miami#loungewear#black fashion#black designers#blackstyle

89 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bradley Joseph Clemens - Owner Of B & M Timber

In his spare time, Bradly Joseph Clemens enjoys camping and spending time with his family, golfing, and fishing. His favorite sports team is the Oregon Ducks, and his interests include hunting, family, the Lord, backpacking, traveling, and golfing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

WHEN AN NCIS AGENT TURNS UP DEAD AND KASIE GOES UNACCOUNTED FOR, THE TEAM MUST WORK QUICKLY TO TRACK THE KILLER, ON “NCIS,” MONDAY, OCT 24

“The Good Fighter” – When an NCIS agent turns up dead and Kasie goes unaccounted for, the team must work quickly to find the killer, on the CBS Original series NCIS, Monday, Oct 24 (9:00-10:00 PM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network and available to stream live and on demand on Paramount+*.

REGULAR CAST:

Sean Murray

(NCIS Special Agent Timothy McGee)

Wilmer Valderrama

(NCIS Special Agent Nicholas “Nick” Torres)

Brian Dietzen

(Medical Examiner Jimmy Palmer)

Diona Reasonover

Katrina Law

(Forensic Scientist Kasie Hines)

(NCIS Special Agent Jessica Knight)

Rocky Carroll

Gary Cole

(NCIS Director Leon Vance)

(FBI Special Agent Alden Parker)

GUEST CAST:

Mark Atteberry

(Medgar Nash)

Amber Friendly

(Eden Greyson)

Menik Gooneratne

(Diya Khatri)

Damian Joseph Quinn

(Travis Baltoni)

KayKay Blaisdell

(Gen Z Girl)

Vonzell Carter

(Instructor)

WRITTEN BY: Kimberly-Rose Wolter

DIRECTED BY: Jose Clemente Hernandez

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 3.26

Beer Birthdays

William Brand (1938)

Bill Siebel (1946)

Rudi Ghequire (1959)

Ben Myers

Fraggle (1967)

Scott Vaccaro (1978)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Alan Arkin; actor (1934)

Richard Dawkins; biologist, writer (1941)

Paul Erdos; Hungarian mathematician (1913)

Robert Frost; poet (1874)

Leonard Nimoy; actor (1931)

Famous Birthdays

Edward Bellamy; writer (1850)

Pierre Boulez; conductor (1925)

Nathanial Bowditch; astronomer (1838)

James Caan; actor (1940)

Joseph Campbell; writer (1904)

Bob Elliot; comedian, "Bob & Ray" (1923)

Marshall Faulk; St. Louis Rams RB (1973)

Leeza Gibbons; television hostess (1957)

Jennifer Grey; actor (1960)

Sterling Hayden; actor (1916)

Duncan Hines; writer, cake-mix mogul (1880)

A.E. Housman; English writer, poet (1849)

James Iha; rock guitarist (1968)

Michael Imperioli; actor (1966)

Erica Jong; writer (1942)

Harry Kalas; sportscaster (1936)

Keira Knightley; actor (1985)

Vicki Lawrence; actor (1949)

Anthony James Leggett; physicist (1938)

Joe Loco; jazz musician (1921)

Leslie Mann; actor (1972)

James Moody; jazz saxophonist (1925)

Sandra Day O'Connor; US Supreme Court justice (1930)

Nancy Pelosi; politician (1940)

teddy Pendergrass; pop singer (1950)

Diana Ross; pop singer (1944)

Annette Schwartz; German porn actor (1984)

Martin Short; actor, comedian (1950)

Amy Smart; actor (1976)

Paige Spiranac; golfer (1993)

Misty Stone; porn actor (1986)

Richard Tandy; rock musician, "ELO" (1948)

Steven Tyler; rock singer (1948)

Sara Jean Underwood; model (1984)

William Westmoreland; military general (1914)

Tennessee Williams; writer, playwright (1911)

Bob Woodward; journalist (1943)

0 notes

Text

James M. Barry, Sr., age 83, of Ellisville, Missouri passed away on Sunday, October 8, 2023. He was born in Louisville, Kentucky on September 9, 1940 to Vincent and Lorraine Barry (nee Decker).

Jim is survived by his beloved wife of 61 years, Page Barry (nee Myers); loving children, Robin (Robert) Gerchen, Jim (Sally) Barry, and Jennifer (Garland) Hines; treasured grandchildren, Allison (Christian) Meyer, Robert Hancock, Alexandra Gerchen, Jean-Martin Gerchen, Jack Barry, Hannah Barry, Thomas Barry, Joseph “Vance” Watkins, Nicholas Watkins, and James Watkins; dear brother, Vince (wife Patricia survives) Barry; and a host of other family members and friends.

He was preceded in death by his father, Vincent Barry; and mother, Lorraine Barry.

According to Jim, he was the favorite child (I believe Uncle Vince might agree). He and his brother grew up above The Copper Kettle, a tavern his parents owned. He was a caddy at the local golf course and soon became very good at the sport. His love for golf continued throughout his life even in his waning days when his grandsons would come over to keep him company and watch golf on tv with him.

He attended Cincinnati Academy of Commercial Art following high school and soon landed a job at Maritz in St. Louis, while fulfilling his commitment as an Air Force reservist. It was at Martiz that he made lifelong friends – Tom Lavelle, Herb Rose and Rich Avett. He and Herb Rose went on to found Barry, Rose & Associates and from there he became the creative director at Herman Marketing where photography became his main focus.

His proudest freelance project was the creation of the City of Ellisville logo which is still used today.

In his younger years, he collected beer cans and was a proud member of the Beer Can Collectors of America. More recently, he enjoyed woodworking, especially turning bowls, carpentry and cabinet making, buying and reselling antique tools.

Of late, he was very proud member of the American Legion, Post 556.

Jim was well known by his family and friends for his very timely sense of humor, throwing in zingers when you’d least expect it. Granddad was also a wonderful, creative soul leaving behind beautiful gifts for his children and grandchildren including paintings, hand-turned wooden boxes, bowls, ice cream scoops and ink pens as well as furniture and cabinetry in our homes.

In lieu of flowers, please donate to the following charities:

0 notes