#material philology of manuscript studies

Text

“The manuscript book isn’t only the necessary medium for the trasmission of ancient and medieval culture: it’s also a complex and dynamic object, which reflects, in its appearance and physical structure, the cultural, economical, social and political changes through the centuries.” - Marilena Maniaci.

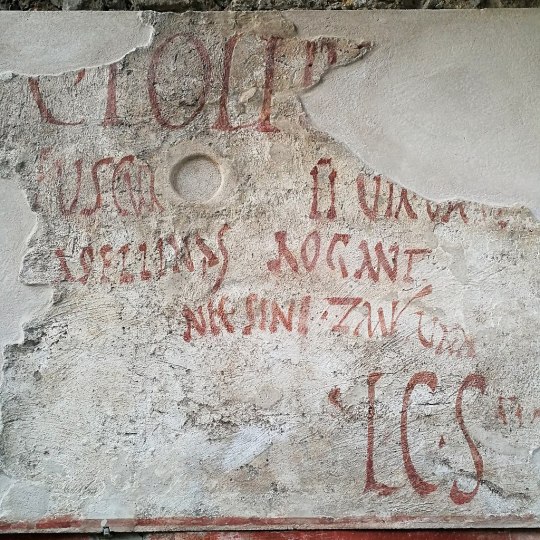

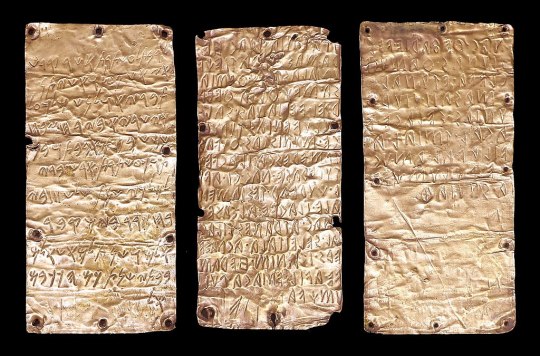

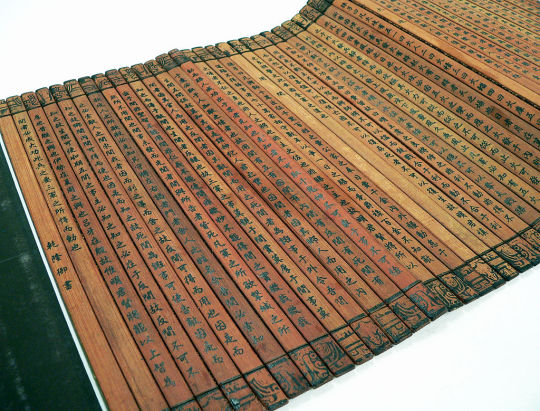

Throughout history, humankind has always felt the need to communicate, and to fulfil that need has used a variety of recipients for their writing — organic, inorganic, of plant or animal origin… Before, and alongside, the well-known triptych of papyrus-parchment-paper were and are clay, shards of pottery, metals, fabrics, leaves, wood, bones…

Any writing, in its materiality, is a two-faced coin. One face is that which can be easily (or not) seen, such as the text and the images. The other face is all that is not seen, be it inside the writing, such as the material aspects, the structure, the techniques, or outside the writing, such as the culture or socio-economic situation.

While philology and palaeography study the text and images are the interest of art historians, that hidden other face is the subject of research of codicology, particularly in its acceptation of archaeology of manuscripts. Codicology is a relatively recent branch of studies, which originates as an ancillary science to philology and palaeography and as such still lacks a unified method or mission, but in the aforementioned meaning of the term and for what concerns us, it can be defined as the study of the history of codices (sing. codex).

Codicology, then, studies the codex in everything that isn’t text and writing, and partially images (although all of these things give contextual information, and are taken into consideration). But what, exactly, is a codex?

A codex isn’t a book, it’s not even a scroll - at least, not necessarily. As defined by Marilena Maniaci a codex is “a container of information, mostly textual, but also visual and musical, in which the dimension of immaterial ideas interacts, in different and complex ways, with the materiality of the object.” More simply, a codex is any object consisting of a material which has been written on or which was meant to be written on and which has been bound or could have been bound.

A scroll is a codex, a book is a codex, but also ostraka (pottery shards) which have been tied together through holes, or a single and quite big piece of vellum which has been folded.

The three following images are all codices, as different as they may seem!

Codicology studies the materials a codex is composed of, the way it was produced, used, re-used, its history throughout the years, in whose hands it ended up and how its “adventures” influenced its physicality. These informations, seemingly of secondary importance, can give us interesting insights on the times the codex “lived” through.

#history chirp#history#material history#manuscript#manuscript history#medieval manuscripts#papyrus#parchment#paper#writing table#codicology#codex#medieval codex#book of hours#writing history

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saints&Reading: Tuesday, January 16, 2024

janaury 3_january 16

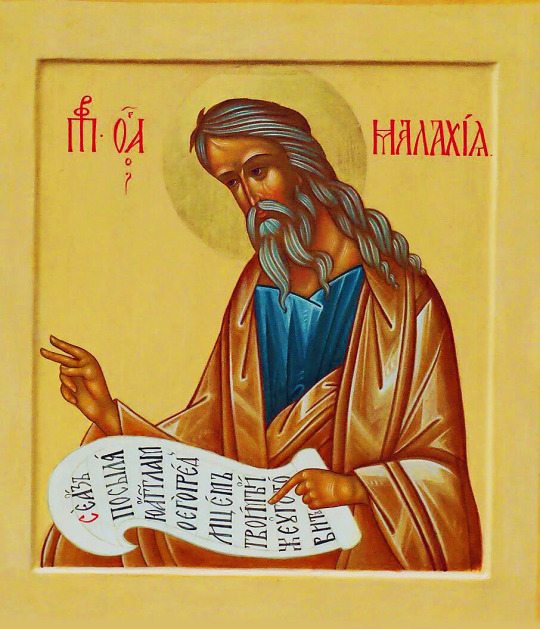

HOLY PROPHET MALACHI (400 B.C.)

The Holy Prophet Malachi lived 400 years before the Birth of Christ, at the time of the return of the Jews from the Babylonian Captivity. Malachi was the last of the Old Testament prophets, therefore the holy Fathers call him “the seal of the prophets.”

Manifesting himself an image of spiritual goodness and piety, he astounded the nation and was called Malachi, i.e., an angel. His prophetic book is included in the Canon of the Old Testament. In it he upbraids the Jews, foretelling the coming of Jesus Christ and His Forerunner, and also the Last Judgment (Mal 3:1-5; 4:1-6).

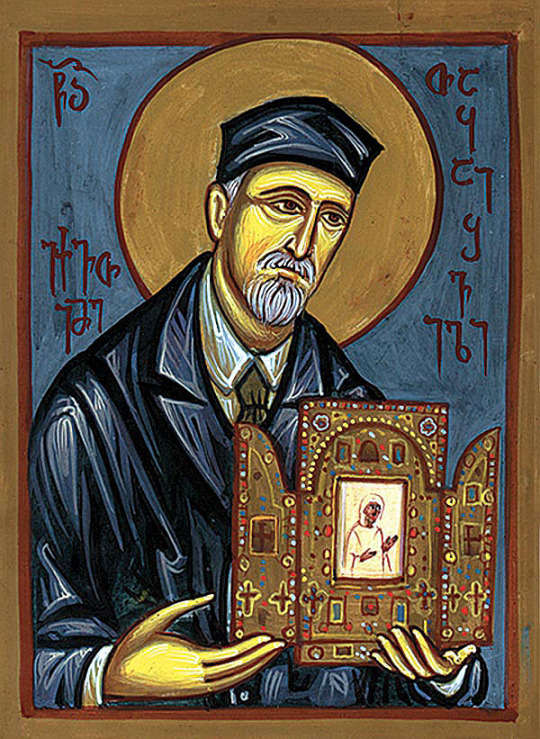

VENERABLE EUTHYMIUS (TAQAISHVILI) THE MAN OF GOD OF TBILISI (1953)

Saint Ekvtime (Euthymius) Taqaishvili, called the “Man of God,” was born January 3, 1863, in the village of Likhauri, in the Ozurgeti district of Guria, to the noble family of Svimeon Taqaishvili and Gituli Nakashidze. He was orphaned at a young age and raised by his uncle.

From early childhood St. Ekvtime demonstrated a great passion for learning. Having completed his studies at the village grammar school, he enrolled at Kutaisi Classical High School. In 1883 he graduated with a silver medal and moved to St. Petersburg to continue his studies in the department of history-philology at St. Petersburg University. In 1887, having successfully completed his studies and earned a degree in history, St. Ekvtime returned to Georgia and began working in the field of academia. His profound faith and love for God and his motherland determined his every step in this demanding and admirable profession.

In 1895 Ekvtime married Nino Poltoratskaya, daughter of the famous Tbilisi attorney Ivan Poltoratsky, who was himself a brother in-law and close friend of St. Ilia Chavchavadze the Righteous. From the very beginning of his career St. Ekvtime began to collect historical-archaeological and ethnographical materials from all over Georgia. His sphere of scholarly interests was broad, including historiography, archaeology, ethnography, epigraphy, numismatics, philology, folklore, linguistics, and art history. Above all, St. Ekvtime strove to learn more about Georgian history and culture by applying the theories and methodologies of these various disciplines to his work.

In 1889 St. Ekvtime established the Exarchate Museum of Georgia, in which were preserved ancient manuscripts, sacred objects, theological books, and copies of many important frescoes that had been removed from ancient churches. This museum played a major role in rediscovering the history of the Georgian Church.

In 1907 St. Ekvtime founded the Society for Georgian History and Ethnography. Of the many expeditions organized by this society, the journey through Muslim (southwestern) Georgia was one of the most meaningful. Having witnessed firsthand the aftermath of the forced isolation and Islamization of this region, St. Ekvtime and his fellow pilgrims acquired a greater love for the Faith of their forefathers and became more firmly established in their national identity. Though they no longer spoke the Georgian language, the residents of this region received the venerable Ekvtime with great respect, having sensed from his greeting and kindness that he had come from their far-off motherland.

There was not a single patriotic, social or cultural movement in Georgia during the first quarter of the 20th century in which St. Ekvtime did not actively take part. Among his other important achievements, he was one of the nine professors who founded Tbilisi University in 1918. St. Ekvtime also vigorously advocated the restoration of the autocephaly of the Georgian Orthodox Church.

On March 11, 1921, the Georgian government went into exile in France. The government archives and the nation’s spiritual and cultural treasures were also flown to France for protection from the Bolshevik danger. St. Ekvtime was personally entrusted to keep the treasures safe, and he and his wife accompanied them on their flight to France. St. Ekvtime bore the hardships of an emigrant’s life and the horrors of World War II with heroism, while boldly resisting the onslaught of European and American scholars and collectors and the claims of other Georgian emigrants to their “family relics.”

In 1931 St. Ekvtime’s wife, Nino, his faithful friend and companion, died of starvation. The elderly widower himself often drew near to the brink of death from hunger, cold, and stress, but he never faltered in his duty before God and his motherland—he faithfully protected his nation’s treasures.

The perils were great for St. Ekvtime and the treasures he protected: British and American museums sought to purchase the Georgian national artifacts; a certain Salome Dadiani, the widow of Count Okholevsky, declared herself the sole heir of the Georgian national treasure; during World War II the Nazis searched St. Ekvtime’s apartment; even the French government claimed ownership of the Georgian treasures.

Finally, the Soviet victory over fascist Germany created conditions favorable for the return of the national treasures to Georgia. According to an agreement between Stalin and De Gaulle, the treasures and their faithful protector were loaded onto an American warplane and flown back to their motherland on April 11, 1945. When he finally stepped off the plane and set foot on Georgian soil, St. Ekvtime bowed deeply and kissed the earth where he stood. Georgia greeted its long-lost son with great honor. The people overwhelmed St. Ekvtime with attention and care, restored his university professorship, and recognized him as an active member of the Academy of Sciences. They healed the wounds that had been inflicted on his heart.

Exhausted by the separation from his motherland and the woes of emigration, St. Ekvtime rejoined society with the last of his strength. But mankind’s enemy became envious of the victory of good over evil and rose up against St. Ekvtime’s unshakable spirit. In 1951 the Chekists arrested his stepdaughter, Lydia Poltoratskaya. St. Ekvtime, who by that time was seriously ill, was now left without his caregiver. In 1952, without any reasonable explanation, St. Ekvtime was forbidden to lecture at the university he himself had helped to found, and he was secretly placed under house arrest. The people who had reverently greeted him upon his return now trembled in fear of his persecution and imminent death. Many tried to visit and support St. Ekvtime, but they were forbidden. On February 21, 1953, St. Ekvtime died of a heart attack, and three days later a group of approximately forty mourners accompanied the virtuous prince to his eternal resting place.

On February 10, 1963, the centennial of St. Ekvtime’s birth, his body was reburied at the Didube Pantheon in Tbilisi. When his grave was uncovered, it was revealed that not only his body, but even his clothing and footwear had remained incorrupt. St. Ekvtime’s relics were moved once again, to the Pantheon at the Church of St. Davit of Gareji on Mtatsminda, where they remain today.

The body of Nino Poltoratskaya-Taqaishvili was brought from Leville (France) and buried next to St. Ekvtime on February 22, 1987.

The Holy Synod of the Georgian Apostolic Orthodox Church canonized St. Ekvtime on October 17, 2002, and joyously proclaimed him a “Man of God.”

© 2006 St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood

1 PETER 3:10-22

10 For "He who would love life And see good days, Let him refrain his tongue from evil, And his lips from speaking deceit. 11 Let him turn away from evil and do good; Let him seek peace and pursue it. 12 For the eyes of the LORD are on the righteous, And His ears are open to their prayers; But the face of the LORD is against those who do evil." 13 And who is he who will harm you if you become followers of what is good? 14 But even if you should suffer for righteousness' sake, you are blessed. "And do not be afraid of their threats, nor be troubled." 15 But sanctify the Lord God in your hearts, and always be ready to give a defense to everyone who asks you a reason for the hope that is in you, with meekness and fear; 16 having a good conscience, that when they defame you as evildoers, those who revile your good conduct in Christ may be ashamed. 17 For it is better, if it is the will of God, to suffer for doing good than for doing evil. 18 For Christ also suffered once for sins, the just for the unjust, that He might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive by the Spirit, 19 by whom also He went and preached to the spirits in prison, 20 who formerly were disobedient, when once the Divine longsuffering waited in the days of Noah, while the ark was being prepared, in which a few, that is, eight souls, were saved through water. 21 There is also an antitype which now saves us-baptism (not the removal of the filth of the flesh, but the answer of a good conscience toward God), through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, 22 who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, angels and authorities and powers having been made subject to Him.

MATTHEW 10:16-22

16 Behold, I send you out as sheep in the midst of wolves. Therefore be wise as serpents and harmless as doves. 17 But beware of men, for they will deliver you up to councils and scourge you in their synagogues. 18 You will be brought before governors and kings for My sake, as a testimony to them and to the Gentiles. 19 But when they deliver you up, do not worry about how or what you should speak. For it will be given to you in that hour what you should speak; 20 for it is not you who speak, but the Spirit of your Father who speaks in you. 21 Now brother will deliver up brother to death, and a father his child; and children will rise up against parents and cause them to be put to death. 22 And you will be hated by all for My name's sake. But he who endures to the end will be saved.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#gospel#bible#wisdom#saints

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

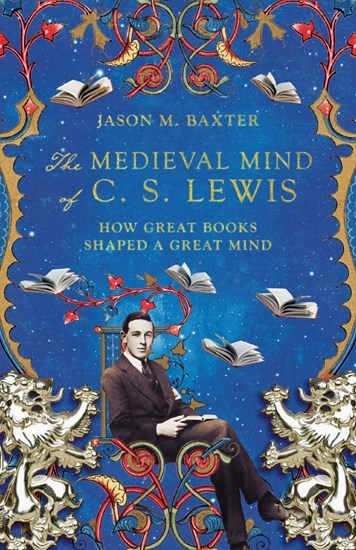

Book Review | The Medieval Mind of C.S. Lewis: How Great Books Shaped a Great Mind by Jason M. Baxter

I somehow missed this book when it was published last year, but happily, I received it as a gift over the holidays. The content is pretty much exactly what the title says: the book focuses on how Lewis’ work as a medievalist shaped his life and other works, particularly his fantasy and Christian writings. At less than 200 pages long, it’s a short and sweet introduction to Lewis’ worldview, and you don’t have to be a medievalist to appreciate it, though knowing some of the medieval texts being discussed definitely adds to the value.

The book begins with the assertion that while many people know Lewis as a fantasy author and Christian writer, his work as a medievalist is less widely known. I find this claim to be doubtful—to me, The Allegory of Love is one of the defining works of his career, second only to the Narnia series—but of course, as a medievalist, my perception may be skewed. Baxter then guides the reader through some of the medieval works that influenced Lewis, with a particular emphasis on Boethius and Dante, providing specific examples from Lewis’ non-academic writings which demonstrate their influence.

One of the things I like most about Lewis as scholar, which Baxter emphasizes throughout this book, is the sense of wonder and enchantment he brings to his discussions of old literature. I know that in my own work, which often gets caught up in the material details of manuscript production and transmission, it’s easy to lose track of the simple enjoyment that brought me to literary studies in the first place. Lewis never lost sight of that, placing it first and foremost even in his more technical discussions of philology and reception history. This sense of wonder became an integral part of every aspect of his life, from his work to his religion.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Writing of History in Ancient Egypt (IV)

Roberto B. Gozzoli The Writing of History in Ancient Egypt during the First Millennium BC (ca. 1070-180 BC). Trends and Perspectives, Golden House Publications, 2006, GHP Egyptology 5 (excerpts from the Introduction)

“Owning some ideas to Assmann’s studies, my research focused on the first millennium BC historical sources, an interest that dates back to the times of my BA and MPhil dissertations.57 Despite new publications of some texts have appeared in the last twenty years, complemented by literary, philological or grammatical studies, any historiographic approach to them is yet missing.58 Moreover, I felt that a comprehensive study of historical writing in Egypt during the first millennium BC was lacking. Chronologically, my upper limit of the material studied is set up at the fall of the New Kingdom; while the lower limit reaches the reign of Ptolemy V. The upper date is a sort of a natural delimiter in Egyptology. The lower one instead should be considered with more flexibility. While trends in early Ptolemaic royal texts were a target for the research, the analysis of how the past is dealt in the apocalyptic literature and in the stories, which follow earlier traditions but are known from later manuscripts made me trespass that border, in order to give a comprehensive view of the entire genre.

The material here studied is essentially divided in two parts, one called royal inscriptions and the other (Hi)stories. The royal inscriptions include almost any text of the period from the Libyan Period till the first two centuries of Ptolemaic domination. Some exclusion has been done, but is generally confined to very fragmentary texts. Within the inscriptions of the Ptolemaic Period, priestly decrees are also included. Such addition is entirely due to the fact that those decrees continue themes that are already part of the royal inscriptions. From a methodological point of view, starting from the study of the royal military texts as done by Spalinger, I tried to divide the structure of the text as belonging to a codified genre from the historical contents present in them.59

In some cases, the presence of parallels for a text is eased by its belonging to a specific group of inscriptions, triumphal texts, iw.tw reports, inundation inscriptions and so forth. The concordance of parallels and textual classes demonstrates the existence of what I call an internal intertextuality, nothing particularly surprising for texts that show high degrees of codification. For my point of view, however, the presence of an external intertextuality is more significant, as it demonstrates the conscious usage of similar phrases and concept in texts of different genre.60 Discovering models and intertextuality also favoured the interpretative process,why a text assumed a certain code, and the eventual ideology behind it.61

While the royal inscriptions are a class by their own, the second part, (Hi)stories, is devoted to Herodotus (chapter 5), Manetho (chapter 6), stories (chapter 7) and apocalyptic literature (chapter 8). The topics are certainly more variegated than the first part, but the main of aim of research is substantially the same for the four chapters. In this case, it focuses on the importance of the past in Egypt, how ancient Egyptians dealt with and exploited it during the first millennium. Assmann aimed to find the traces of earlier events in later Egyptian history. Like him, my intention is of identifying those traces during the first millennium BC.

At the same time, I wanted to go a step further: as historical information “in Greek style” did not exist in Egypt, such (hi)stories are an important part of any narrative relative to historical or pseudo-historical characters. While the ways those tales are preserved is not part of my research, it is the process of selecting the events narrated for those characters which particularly attracts me, as it implies the existence of an “agenda”. Such agenda elaborates historical or pseudo historical information for specific intentions. As most of the information is essentially pseudo-historical, the label originates from this notion. As it will be seen in the due course, this process exploits famous names of “historical” pharaohs, Sesostris,Thutmose III and Ramesses II. Those pharaohs are inserted in narratives completely unrelated to the periods they lived, but explainable for the first millennium BC situation, when the relative stories were invented.

In the specificity of each chapter, for Herodotus, attention has been devoted on what his Egyptian sources wanted to highlight of Egyptian history, and where his king list was derived from. In this case, the work by Lloyd has been considered as the fundamental reference for the analysis.62 As it will be seen, the information relative to Egyptian history of the proper historical chapters in Herodotus (II, 99-182) diverges in quality. Herodotus partially transforms the information his Egyptian sources had given to him, therefore the view of how Egyptian used their past is partially blurred. However, as the historian from Halicarnassus is obliged to follow what his informers say –a statement that will be proved in the due course- almost any historical material which he presents can be used in order to reconstruct the objective of such a narrative from an ancient Egyptian point of view.

The process used for Herodotus has been in large part similar for Manetho: my interest was centred where his historical work originated from, whether or not there were Egyptian and/or foreign earlier models and what sort of historicalinformation was available to him at the time of writing. Thus, what earlier historians, Herodotus and others from the earlier Hellenistic Period (Hecataeus of Abdera for Egypt and Berossus for Mesopotamia) had said, and whether influences are present in Manetho’s historical work. Moreover, Manetho’s history did not reach the modern reader in its complete form, but only as transmitted by later authors. This requires filtering the historical information in order to discern what Manetho might have said from what may be later additions. Out of scholarly honesty and anticipating some of my interpretations about his Aegyptiaca, I believe that most of the survived text comes from Manetho’s original, with some later interpolations and embellishments here and there.

Delving into scholarly literature, I discovered that the importance of the cultural background in Manetho’s history was already considered by Struve, in a neglected study published in Russian.63 In my research, dates and royal names are fundamental in order to use as proof of the accuracy of Manetho’s sources for his history. Therefore, an appropriate appendix has been given at the end of this book. But I have to refer to Helck, Redford, Krauss and von Beckerath for anyone really interested about the intricacies of Egyptian chronology and identification of royal names.64

The seventh chapter is an assortment of stories, pseudo-epigraphs such as the Bakhtan and Famine stelae, also including the Shabaqo Stone and demotic stories (Drunken Amasis, Setne I and II, Pedubastis cycle). For the scope of my research, two different paths are followed. Placing the story in its historical context is the first objective. My preposition however was of sorting out from the story itself what the scribe aimed from writing a certain document mentioning specific historical characters. Introducing some of the contents present in this book, in the story of Neferkare and Sasenet for example, I considered important to understand whether there was a particular reason to have the New Kingdom text copied again during a later (Nubian) period.65

The use and peruse of history is also the target of the last chapter. The Demotic Chronicle exploits the past in order to explain the present conditions. Moreover, the Apocalyptic Literature and its end of the world hopes to resurrect the old good –and gone – values has led me to inquire who was the original king expected to come and save his people.

At this point, some of the readers can note that private biographies are not part of this work, in spite of the fact they are mentioned at the beginnings of this introduction as historical sources. Reasons of space have prevented me to include them here; a detailed work about biographies during the first millennium BC will have occupied an entire monograph just by its own.66 Asking for leniency, as very small excuse I can say that the private biographies of any period as historical sources will be part of a future work. Another point is certainly that as the original quest was about how much the historical texts are “historical”, it was not my intention to build a social history. How various classes related each other sometime appear here and there, but there are inserted in a broader historical discourse. Finally, the problem of who is the audience of the royal texts, an aspect deeply linked to the concept of “propaganda” itself, is completely disregarded. Yet as partial justification, a research relative to the concept of hierarchy of and access to the knowledge is one of the future projects.”

On line source with the entirety of the thesis https://href.li/?https://www.academia.edu/359798/The_Writing_of_History_in_Ancient_Egypt_during_the_First_Millennium_BC_ca_1070_180_BC_Trends_and_Perspectives

I think that Herodotus has the merit that he was the first person to write a comprehensive account of the ancient Egyptian civilization and more particularly a continuous history of Egypt, as part of his history of the rise of the Persian Empire and of the Greco-Persian wars. Moreover, I think that it is now generally accepted that he did a real investigation in Egypt and he used Egyptian priests as sources, as the excerpts of the thesis of Roberto Gozzoli that I have reproduced show. Of course, as Pr. Gozzoli says, the historical part of Herodotus’ Book II (on Egypt) is of unequal value. On the one hand, despite some flaws from a modern point of view, his account of the Saite period is reliable and remains a main source for this period of the Egyptian history. On the other hand, his account of the pre-Saite period is schematic and interwoven with tales, the persons of the rulers presented in it are often confused, and it contains some important factual errors and omissions, although it is not totally devoid of value (the first pharaoh -Min- is identified correctly, all periods of the Egyptian history are represented, except the Hyksos, what the pharohs do according to it correspond to the traditional functions of the Egyptian kingship, the memory of a female ruler and of a period in which the temples had been closed is preserved, the description of the building of the pyramids is rational and preserves the memory of the role of the use of forced labor and of oppressive policies in it). But Herodotus expresses himself his scepticism about what his Egyptian sources had told him about the pre-Saite period, although of course he did not have the time and the means to check the narrative of the Egyptian priests. Perhaps more importantly, as R. Gozzoli’s text shows, although of course the Egyptian material is partially transformed in the transition from the Egyptian sources to Herodotus, the testimony of the latter is very important for the reconstruction of the historical consciousness of the Egyptians of the Late Period.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Major Translators of the Qur’an Into Latin

Thomas E. Burman, in his study of Latin Qur’anic manuscripts, details four such translations between the years 1140-1560. These works are:

The earliest was by Robert of Ketton, who was employed to translate the Qur’an by Blessed Peter the Venerable in 1142 to better evangelize Muslims. This work, called the Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete, is a paraphrase that attempts to keep the spirit, if not structure, of the original Arabic. This work survives in about twenty-five medieval manuscript, and was printed in two editions in the sixteenth century. This was the single most popular Latin translation of the Qur’an.

Mark of Toledo, commissioned by Archbishop Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada in 1211, produced the Liber Alchorani. This translation was made in the context of the Reconquista; it was meant to be the authoritative Qur’an used by Muslims living in lands conquered by Iberian Christians. In this way, the archbishop had hoped to limit the autonomy of subject Muslim communities. This work, a word-for-word translation, exists in six full manuscripts and one fragmentary one.

Flavius Guillelmus Raymundus Mithridates, a Jewish convert to Christianity who evidently (judging by the names) tried to reinvent himself a couple of times over post-conversion. An enormously influential figure in the development of a Christianized Kabbalah, Mithridates was known for citing Talmudic and Islamic texts in Christian sermons. Between 1480-1482, he started (and failed to complete) a translation of the Qur’an into Latin. Though he seems to have translated many individual verses, only two surahs were completely translated. Though not completed, Mithridates had declared his intention on creating an edition of the Qur’an that would have had the Arabic original placed side-by-side with translations into Hebrew, Syriac, and Latin. This was not a scholarly exercise, however; it seems to have been meant to be an ornamental piece, an expensive item meant to be kept in a collector’s display of exotic books.

In 1518, the Augustinian Cardinal Egidio da Viterbo commisioned another translation of the Qur’an, by Spaniard Iohannes Gabriel Terrolensis. This copy, like Mithridates’s unfinished work, was an edition that presented the Arabic original alongside the Latin translation. There is a clear concern for the philological structure of the original Arabic, and an attempt to replicate its content as closely to the original as possible. Despite this, there were clear errors in the attempted translations, and at one point the original manuscript was criticized (perhaps a little excessively) and corrected by Leo Africanus, the Pope’s slave and convert to Catholicism from Islam.

In addition to these four translators, there was at least one more translator of note: Juan de Segovia, who created a trilingual Arabic-Castilian-Latin Qur’an. His work has no survived, except possibly in fragments that have not been positively attributed to him, though the preface to his trilingual edition has. Juan de Segovia announces in his preface that he was inspired to translate the work in order to correct the errors of Robert of Ketton’s translation: he felt that it was too loose in its paraphrasing, occasionally omitted information (though nothing doctrinally significant), and added Islamic exegetical material into the text in ways that it was not always clear that it was an addition. Juan de Segovia, like Egidio da Viterbo, desired an edition of the Qur’an which could be used by Christians to better understand Islam - and to that purpose, he hired a Muslim named Iça, also from Segovia, to help translate the original Arabic into Castilian, from which the Latin translation was made.

Source: Thomas E. Burman’s Reading the Qur’ān in Latin Christendom, 1140-1560

#history#Qur'an#translation#figures of note#Robert of Ketton#Leo Africanus#Juan de Segovia#religious pluralism#Renaissance

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

If you’re a medieval historian, you normally work a lot with manuscripts. A manuscript is just a text written by hand, although manuscripts are distinguished from inscriptions by the material on which they are written: a manuscript is normally written on perishable materials — like calfskin in much of Europe, birch bark in Russia and Central Asia, bamboo and paper in East Asia, and palm leaves in India and Southeast Asia — while an inscription is cut into a stone or metal surface. Manuscripts are usually a lot more informative than inscriptions and also a lot more diverse in content and authorship. In Europe and Northeast Asia there are a lot of medieval manuscripts.

An image from Royal Armouries manuscript I.33, the oldest armed martial arts treatise in the world. It was written in southern Germany in the early fourteenth century, and is thus older than almost any extant Indo-Malaysian manuscript on any topic. This says a lot about the range of sources historians working in each region can expect to use. Full manuscript can be found here (Wiktenauer).

Manuscripts are often illustrated, giving valuable information about life and times not explicitly recorded in writing. Their pages can be dated chemically, giving reasonably precise dates even to texts without written chronograms — although this isn’t necessary with many texts, as close dates can often be established on the basis of the script. If the script looks like a fourteenth-century script, you’re probably looking at a fourteenth-century text (although there’s more to it than that). There are enough texts to allow for this kind of detailed palaeographic analysis in much of Europe and temperate Asia.

The language and script (littera hybrida) of this manuscript tell us that it was written in around the middle of the fifteenth century in the Low Countries. There are tons of manuscripts in littera hybrida; it was practically the national script of the Netherlands in the fifteenth century.

All of this should be reasonably obvious and well-known. Here, though, I want to point out that medieval Afro-Eurasia — let’s leave the Americas aside for the purposes of this article — wasn’t a single temperate environment in which both state and private archives hoarded and preserved large numbers of texts written on organic materials. These kinds of sources just aren’t available for much of the world, whether because writing never developed there or because organic materials don’t last long in certain environments. Naturally, these problems are particularly acute in humid tropical climates.

In much of the tropics, insects, heat, and humidity meant that even if texts were written on palm leaves and animal skins, they had to be deliberately preserved or copied perhaps once in a generation in order to make their way down to us today. This wasn’t the case in England or China; a locked wooden box in a parish church or town hall would be sufficient to keep a piece of parchment safe and few special measures needed to be taken. The medieval historical record is thus inherently biased in favour of societies in temperate climes.

The number of genuinely medieval manuscripts from Southeast Asia can be counted on one hand, even though we know from inscriptions that writing has a long history in the region (dating back to the fourth century and possibly earlier). The oldest extant Malay manuscript has been radiocarbon dated to the fourteenth century, even though the oldest Malay inscriptions date to the seventh century and are thus slightly older than the oldest texts in English. We are consequently reliant on inscriptions for the reconstruction of much of medieval Indo-Malaysian history and society, and on much later (definitively post-medieval) manuscripts for the study of Southeast Asian literature. This gives a particular spin to historical events and restricts what can be studied through traditional philological methods.

“Raja Barus”, ‘the King of Barus’ in a Malay manuscript of 1797, one of the oldest copies of the Hikayat Raja Pasai. The story probably dates to the fourteenth century. Yes: it was written in the late eighteenth century. Yes: it’s a good source for the fourteenth century. That’s how a lot of history in the tropics works. Deal with it.

This presents scholars of the medieval Old World tropics with a bit of a problem. Historians of medieval Europe can freely parade manuscript illustrations in books and, nowadays, on social networks without any qualms because the illustrations they’re showing off are bona fide medieval images. But you can’t do that if the manuscripts didn’t survive, and there are a lot of issues involved in using later manuscripts to demonstrate earlier art and history. How can a complete picture of the Hemispheric Middle Ages be created and shown to the world when Indonesian and tropical African manuscripts are so late and so poorly represented?

Should scholars of the medieval tropics focus on ‘legitimately’ medieval things — bronzes, inscriptions, reliefs — or should they include later images of supposedly earlier phenomena and risk collapsing the entire history of e.g. Indonesia into one undivided whole?

In museums you tend to find the latter approach. In the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, the oldest keris in the world (made, or at least inscribed, in 1342 CE) is in the same case as a piece of nineteenth-century Muslim headgear. Colonial-era dress and artworks rub shoulders with tenth-century bronzes and thirteenth-century statues. I find that problematic; you wouldn’t put a medieval English sword and a Regency-era lady’s bonnet in the same display, I shouldn’t think. Europe and Indonesia are thus treated differently: Europe’s history is divided into sections that are studied more or less independently while Asian history, and especially tropical Asian history, is treated as one inseparable whole, divided more by region than by period. This is one reason among many why Southeast Asia may never be integrated into the academic study of the medieval world (let alone the popular imagination about the Middle Ages).

And what about eastern Indonesia and New Guinea? Neither part produced any written literature, as far as we know, before the fifteenth century, and the oldest manuscripts from eastern Indonesia date to the early sixteenth century. New Guinea was part of the medieval world; it was certainly known to people in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Java and other parts of Indonesia. But what can we show the world to represent this medieval Papuan history? There aren’t any manuscripts. There aren’t even any sculptures or very many bronze objects (although some of the latter are occasionally found). That doesn’t mean New Guinea just vanished from the world in the Middle Ages or that the people there preserved some primordial ‘Stone Age’ lifeways, though, as the popular imagination seems to have it.

Art in New Guinea, whether on the coasts or in the highlands, is dominated by wooden sculpture. While plenty of carved wooden objects survive from temperate medieval Eurasia, no examples of the wooden sculpture of medieval New Guinea have come down to us. Can we assume that modern sculpture is representative of earlier tradition?

That seems like a big leap to me. New Guinea isn’t a primeval place unchanged since the dawn of time but rather a place full of creative human beings, a place where fashion and religion operate like they do anywhere else. Showing a Papuan carving made in the twentieth century by a specific artist from a particular ethnic group as if it were representative of a prehistoric or medieval tradition would ultimately be as peculiar as using David Hockney’s oeuvre to showcase medieval English painting. Style always changes. Where truly medieval eastern Indonesian art has survived, as with a few of the lovely textiles preserved as heirlooms in Timor, the motifs are strikingly different from modern ones.

If we want to raise awareness of the tropical world, then, how do we go about it? How can scholars working on Europe get to know island Southeast Asia and the Swahili coast without introducing an orientalist bias that treats the Middle Ages as identical to modern times, or to some arbitrary ‘traditional’ point in the past? It’s a real conundrum. I suspect, though, that the solution is to help expand the traditional medievalist’s view of what constitutes valid evidence about the medieval world — and perhaps to highlight the ways in which the temperate world diverges from the tropics.

Does the absence of a written or artistic or sculptural record exclude a place from consideration as part of the ‘Global Middle Ages’? Yes — if you restrict yourself to the methods and ideas of traditional medieval scholarship. But if the objective is to account for and better understand the world before the Columbian Exchange, methods simply have to be broadened: the triangulation of archaeology, comparative ethnography, historical linguistics, oral history, and ethnohistory has to be brought in to complement traditional philological scholarship. If that isn’t done then our image of the medieval world will always be restricted to what was written down and preserved, and that naturally introduces a bias towards the temperate — and perhaps also to the European, the white, and the colonial.

This article first appeared as a post on the Medieval Indonesia blog, and a version of its argument has appeared in print in Bryan C. Keene (ed.), 2019,Toward a Global Middle Ages, Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Academic Book Review

Epistolary Acts: Anglo-Saxon Letters and Early English Media by Jordan Zweck. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018. Pp. 240. $56.25.

Argument: In Epistolary Acts, Jordan Zweck examines the presentation of letters in early medieval vernacular literature, including hagiography, prose romance, poetry, and sermons on letters from heaven, moving beyond traditional genre study to offer a radically new way of conceptualizing Anglo-Saxon epistolarity. Zweck argues that what makes early medieval English epistolarity unique is the performance of what she calls “epistolary acts,” the moments when authors represent or embed letters within vernacular texts. The book contributes to a growing interest in the intersections between medieval studies and media studies, blending traditional book history and manuscript studies with affect theory, media studies, and archive studies.

***Full review under the cut.***

Chapter Breakdown

Chapter One: Examines the production of “real” letters, including formal protocols and Anglo-Saxon customs. Includes sections on how Latin protocols and vocabulary were translated into Anglo-Saxon practices, origins and influences on Anglo-Saxon letters, editorial interventions, and immediacy.

Chapter Two: Analyzes the physical form and format of letters. Argues that the Old English Sunday Letter can be understood in terms of mass communication via manuscript culture and oral circulation, that it is a self-replicating document. Includes sections on the history of the Sunday Letter, its audiences, circulation, community, and its use as a material object.

Chapter Three: Analyzes the transmission of letters via messengers. Argues that the bodies of messengers transform and are transformed by contact with the letter. Takes Apollonius of Tyre, Letter of Agbar, and the Life of St. Mary of Egypt as its foci. Includes sections on the history of messengers in Anglo-Saxon England, somatic responses, faith and healing, memorializing bodies for public consumption, and women within epistolary exchange.

Chapter Four: Argues that epistolary acts offered a way of recording (religious) events that left no tangible trace so they could be circulated among believers.Takes Life of St. Basil and the Legend of the Seven Sleepers as its foci. Includes sections on archives, erasure and destruction, and memory.

Theories/Methodologies Used

media studies

genre studies

philology

Reviewer Comments

I read this book last year and it was one of my favorite academic reads, not only because I learned a lot about a genre I had very little knowledge about, but because I love when media studies and medieval studies join forces. I feel like letters are often overlooked within medieval studies as a whole, but particularly within Anglo-Saxon studies, perhaps because we have so few “actual” letters that survive. By taking into account representations of letters in literary texts, Zweck allows us to reflect on a genre we take for granted, making her intervention feel like a necessary addition to the field.

My favorite part of Zweck’s argument was when she discusses how media is not just another word for technology or materiality, but a description of systems, rituals, and protocols. Too often, I think, we have the tendency to think of “media studies” in terms of digitization or what the material object the message is inscribed upon, rather than whole structures and networks of communication. This realization leads Zweck to use the term “epistolary acts” rather than just “letters” or “epistles,” a term which I found helpful when reminding myself that letters were so much more than words on a page.

Zweck’s prose is very clear, and there was never a point where I found myself to be confused. She doesn’t use a lot of heavy literary theory, so understanding what she means by “media studies” is not hard. Because many of the texts she analyzes are somewhat outside the well-known “canon,” I wouldn't recommend this book to people whose only knowledge of Old English literature is Beowulf or the elegies (though she does have a good analysis of The Husband’s Message in her introduction). But even if you haven’t read some of the texts she discusses, her organization is very straight-forward, and I never felt like I couldn’t grasp the importance of her arguments for the Old English corpus as a whole. Having a working knowledge of Old English will also allow you to get the most out of this book, since much of Zweck’s analysis involves close reading.

I enjoyed this book very much, so I highly recommend it to my fellow academics.

Recommendations: This book is useful if you’re working on:

medieval letters, genre markers of letters

recording history, recording miracles, preservation/documentation of events

representations of letters in fiction

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Perfect to lose yourself in

Tolkien's translation of Beowulf dropped today, and goodness gracious is it a beautiful thing. Not only the poetic-prose translation itself (in prose form, but with an ear to how long sentences are and to alliteration), but copious footnotes by Christopher Tolkien about the translation and its composition from the existent manuscripts that JRR had left behind; a couple hundred pages of lecture excepts from JRR's famous lecture series on the poem that are just gorgeous in detail and scope; The Sellic Spell, a piece of Beowulf fan-fiction that JRR wrote about the early adventures of Beowulf/attempt to reconstruct the original tale from which Beowulf is a later version of; and The Lay of Beowulf, a shorter version of the story in verse for singing your children to sleep.

Go to Amazon

Tolkien As Academic Gives Us A New Treasure

Had J.R.R. Tolkien never written The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, or The Silmarillion his fame today would rest on his long career at Oxford University as professor of Anglo-Saxon. There he did pioneering work in philology, but his greatest renown would come from his life long labor of love: studying the great poem Beowulf. Much of Tolkien's work on Beowulf, especially his revolutionary essay "The Monsters and the Critics," has been widely available for many years. Now Christopher Tolkien, serving as his father's literary executor, has give us another treasure: J.R.R. Tolkien's own prose translation of Beowulf.

Go to Amazon

read for right reasons, thoroughly enjoyable and informative. Liked the comments as much if not more than the prose translation

The last few years has seen the release by the Tolkien Estate of several hybrid books that combined original retellings/translations of ancient hero legends (Sigurd, Arthur) with further commentary by J.R.R. Tolkien (on the source material) and Christopher Tolkien (on his father’s work). The latest in this series is Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf, which has perhaps incurred greater interest since outside of his fiction, Tolkien is perhaps best known for his famed essay, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” As with the prior two, one’s enjoyment of this new work will be dependent on one’s delight in /toleration of some pretty arcane scholarship. Personally, I enjoyed all of them, including this latest, but then, I’m a huge Tolkien fan, I’m an English teacher who owns several copies of Beowulf translations and teaches the legend every year, I love the song “Grendel” by Marillion and the book Grendel by John Gardiner, and give me a good footnote or twenty and I’m alight with joy. I couldn’t be more the target audience unless I threw myself into a dragon-prowed boat and laid waste to some English coastal towns. Your mileage therefore may vary.

Go to Amazon

Five Stars

First Beowulf. Interesting. I need an older translation ...

Competes easily with Heaney translation.

Five Stars

Love Tolkien's Translation

Two Stars

Excellent.

Fantastic, almost lyrical translation

The BEST Beowulf!

This book is a excellent resource for writing papers

1 note

·

View note

Text

HMML Avicenna's Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb) and other works, Der Mond ist aufgegangen, ‘Belachen, Lass uns einfältig werden, fromm, Graemen, einen sanften Tod, in Himmel kommen’, democracy and freedom and law, Workshop of Robert Campin Merode Altarpiece Metmuseum, Fernand Khnopff I lock my door upon myself Neue Pinakothek

HMML Avicenna's Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb) and other works, Der Mond ist aufgegangen, ‘Belachen, Lass uns einfältig werden, fromm, Graemen, einen sanften Tod, in Himmel kommen’, democracy and freedom and law, Workshop of Robert Campin Merode Altarpiece Metmuseum, Fernand Khnopff I lock my door upon myself Neue Pinakothek

https://blog.naver.com/artnouveau19/222087687625

HMML

@visitHMML

Avicenna's Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb) is possibly the most important medical book ever written, influential in #Arabic and in Latin translation. Copied in #Baghdad in 1171, this is the earliest copy in HMML's digital collections: https://bit.ly/32dGmqv #12thcentury

https://twitter.com/visitHMML/status/1304398293263355906

Avicenna's Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb)

https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom/view/140473?fbclid=IwAR1bCnzqc8DKU0DKKCPg1YiNsHzORa87xjRZCXLyUd5_jEwRe6AXg4j8NLE

Avicenna

Ibn Sina (Persian: ابن سینا), also known as Abu Ali Sina (ابوعلی سینا), Pur Sina (پورسینا), and often known in the West as Avicenna (/ˌævɪˈsɛnə, ˌɑːvɪ-/; c. 980 – June 1037), was a Persian[7][8][9] polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, thinkers and writers of the Islamic Golden Age,[10] and the father of early modern medicine.[11][12][13] Sajjad H. Rizvi has called Avicenna "arguably the most influential philosopher of the pre-modern era".[14] He was a Muslim Peripatetic philosopher influenced by Aristotelian philosophy. Of the 450 works he is believed to have written, around 240 have survived, including 150 on philosophy and 40 on medicine.[15]

His most famous works are The Book of Healing, a philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and The Canon of Medicine, a medical encyclopedia[16][17][18] which became a standard medical text at many medieval universities[19] and remained in use as late as 1650.[20]

Besides philosophy and medicine, Avicenna's corpus includes writings on astronomy, alchemy, geography and geology, psychology, Islamic theology, logic, mathematics, physics and works of poetry.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avicenna

In June 2009, Iran donated a "Persian Scholars Pavilion" to United Nations Office in Vienna which is placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the Vienna International Center.[118] The "Persian Scholars Pavilion" at United Nations in Vienna, Austria is featuring the statues of four prominent Iranian figures. Highlighting the Iranian architectural features, the pavilion is adorned with Persian art forms and includes the statues of renowned Iranian scientists Avicenna, Al-Biruni, Zakariya Razi (Rhazes) and Omar Khayyam.[119][120]

The 1982 Soviet film Youth of Genius (Russian: Юность гения, romanized: Yunost geniya) by Elyor Ishmukhamedov [ru] recounts Avicenna's younger years. The film is set in Bukhara at the turn of the millennium.[121]

In Louis L'Amour's 1985 historical novel The Walking Drum, Kerbouchard studies and discusses Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine.

In his book The Physician (1988) Noah Gordon tells the story of a young English medical apprentice who disguises himself as a Jew to travel from England to Persia and learn from Avicenna, the great master of his time. The novel was adapted into a feature film, The Physician, in 2013. Avicenna was played by Ben Kingsley.

List of works[edit]

The treatises of Ibn Sīnā influenced later Muslim thinkers in many areas including theology, philology, mathematics, astronomy, physics, and music. His works numbered almost 450 volumes on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived. In particular, 150 volumes of his surviving works concentrate on philosophy and 40 of them concentrate on medicine.[15] His most famous works are The Book of Healing, and The Canon of Medicine.

Ibn Sīnā wrote at least one treatise on alchemy, but several others have been falsely attributed to him. His Logic, Metaphysics, Physics, and De Caelo, are treatises giving a synoptic view of Aristotelian doctrine,[37] though Metaphysics demonstrates a significant departure from the brand of Neoplatonism known as Aristotelianism in Ibn Sīnā's world; Arabic philosophers[who?][year needed] have hinted at the idea that Ibn Sīnā was attempting to "re-Aristotelianise" Muslim philosophy in its entirety, unlike his predecessors, who accepted the conflation of Platonic, Aristotelian, Neo- and Middle-Platonic works transmitted into the Muslim world.

The Logic and Metaphysics have been extensively reprinted, the latter, e.g., at Venice in 1493, 1495, and 1546. Some of his shorter essays on medicine, logic, etc., take a poetical form (the poem on logic was published by Schmoelders in 1836).[122] Two encyclopedic treatises, dealing with philosophy, are often mentioned. The larger, Al-Shifa' (Sanatio), exists nearly complete in manuscript in the Bodleian Library and elsewhere; part of it on the De Anima appeared at Pavia (1490) as the Liber Sextus Naturalium, and the long account of Ibn Sina's philosophy given by Muhammad al-Shahrastani seems to be mainly an analysis, and in many places a reproduction, of the Al-Shifa'. A shorter form of the work is known as the An-najat (Liberatio). The Latin editions of part of these works have been modified by the corrections which the monastic editors confess that they applied. There is also a حكمت مشرقيه (hikmat-al-mashriqqiyya, in Latin Philosophia Orientalis), mentioned by Roger Bacon, the majority of which is lost in antiquity, which according to Averroes was pantheistic in tone.[37]

Avicenna's works further include:[123][124]

Sirat al-shaykh al-ra'is (The Life of Ibn Sina), ed. and trans. WE. Gohlman, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1974. (The only critical edition of Ibn Sina's autobiography, supplemented with material from a biography by his student Abu 'Ubayd al-Juzjani. A more recent translation of the Autobiography appears in D. Gutas, Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition: Introduction to Reading Avicenna's Philosophical Works, Leiden: Brill, 1988; second edition 2014.)[123]

Al-isharat wa al-tanbihat (Remarks and Admonitions), ed. S. Dunya, Cairo, 1960; parts translated by S.C. Inati, Remarks and Admonitions, Part One: Logic, Toronto, Ont.: Pontifical Institute for Mediaeval Studies, 1984, and Ibn Sina and Mysticism, Remarks and Admonitions: Part 4, London: Kegan Paul International, 1996.[123]

Al-Qanun fi'l-tibb (The Canon of Medicine), ed. I. a-Qashsh, Cairo, 1987. (Encyclopedia of medicine.)[123] manuscript,[125][126] Latin translation, Flores Avicenne,[127] Michael de Capella, 1508,[128] Modern text.[129] Ahmed Shawkat Al-Shatti, Jibran Jabbur.[130]

Risalah fi sirr al-qadar (Essay on the Secret of Destiny), trans. G. Hourani in Reason and Tradition in Islamic Ethics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.[123]

Danishnama-i 'ala'i (The Book of Scientific Knowledge), ed. and trans. P. Morewedge, The Metaphysics of Avicenna, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973.[123]

Kitab al-Shifa' (The Book of Healing). (Ibn Sina's major work on philosophy. He probably began to compose al-Shifa' in 1014, and completed it in 1020.) Critical editions of the Arabic text have been published in Cairo, 1952–83, originally under the supervision of I. Madkour.[123]

• Kitab al-Najat (The Book of Salvation), trans. F. Rahman, Avicenna's Psychology: An English Translation of Kitab al-Najat, Book II, Chapter VI with Historical-philosophical Notes and Textual Improvements on the Cairo Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952. (The psychology of al-Shifa'.) (Digital version of the Arabic text)

Der Mond ist aufgegangen - Schlaflieder zum Mitsingen | Sing Kinderlieder

https://youtu.be/sFTzBc6CA7Q

Belachen, Lass uns einfältig werden, fromm, Graemen, einen sanften Tod, in Himmel kommen, democracy and freedom and law

Annunciation Triptych (Merode Altarpiece)

ca. 1427–32

Workshop of Robert Campin Netherlandish

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/470304

Fernand Khnopff, I lock my door upon myself, 1891, Neue Pinakothek Munich.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fernand_Khnopff_-_I_lock_my_door_upon_myself.jpeg

0 notes