#obviously its more complicated and less... jokey than that

Note

IDK if you've ever said anything about it, but in the Lights Out AU, what was Wally's first reaction on realizing that Frank was alive and he wasn't alone anymore? I imagine it was...quite emotional

i Haven't talked about their Initial Reunion yet, no! but yes, it was very emotional! there were certainly many emotions!

namely: fear, confusion, shock, and nearly killing your friend with an oversized baseball bat <3

#im trying to work on a mini comic to expand on this but my art Isnt Arting Correctly#so this will have to do for now#but to put it Short and Simply#frank: WHAT THE FUCK ITS JUST ME!!! ITS ME!!!#wally: oh oops heyyyyy totally thought you were one of the Things <3 my bad <3#wally: ....#wally: HOLY SHIT? FRANK?!#aaaaaand scene#wh lights out au#scribble salad#rambles from the bog#obviously its more complicated and less... jokey than that#i have the scene laid out nicely in my head#but putting it to 'paper' is a challenge!#there are factors to include#like how frank thinks everyone in the storage room is dead & how wally hasnt spoken more than a few mumbled words in a Long time#wally at this point has essentially lost his sense of self and basically just goes through his 'routine' like a robot#so it takes a second for his mind to kinda... reboot in a sense#and in that second frank nearly dies for realsies#haha thats... thats funny actually. Nearly. ha. the irony.#but uhhhh yeah frank really goes Through It for a bit#especially the immediate waking up through running into wally#or more like wally runs into him! purposefully! with the bat!

349 notes

·

View notes

Note

talk shop tuesday huh...

how do *you* go about creating an oc? what comes first, and how do you build the character around that idea? i'm interested in your process!

that is a great and fairly complicated question! I think to me almost all character-building is relational. Aivide was created as a conversation with parts of Al2rnia that compelled me after I read through the worldbuilding masterdoc the others had made, and by Esther saying "we still don't have a hope player." The combination of Hope Player and Doing Stupid Menial Work Until You Die guy gripped me and originated a much more jokey and much more successfully fakenice version of Aivide. Obviously context from real life creeps in too – I was working a campus job that I liked doing but did not get paid very much for or supported in, and having a lot of thoughts about the nature of that kind of work.

So I guess at present my answer would be that the first character sketch is built from the world, and the other character sketches are born from the first character. Govy is a good example of this – I wanted to make a violet Nora's age who was the opposite of Nora in demeanor and life circumstances, and I wanted to give them a meaningful connection. The Govy Pathos Industrial Complex and a lot of the more complicated feelings that exist between those two characters arose as a direct result of Actually Writing Them, just as aivide as she exists right now is the product of Aivide the Prequel and its many revisions, as well as long conversations with my friends about where her character goes after that. The more of a story I actually write, the less so a character becomes a person and not an idea.

Stelad is another example – I spent an afternoon wondering if it would be more interesting for Aivide to have an unconventionally teal ancestor or a conventionally teal ancestor. Once I settled on the answer, Esther and I would go on to use the built up world-context of the Chiono-Eubala transition to contextualize exactly why and how Stelad got there.

With Quartz and friends, I tried to do a lot more thinking ahead than I did in the early stages of Aivide. This was necessary because these were old, old characters with a lot of hyper-conspicuous gaps in what made them tick, and I felt that I couldn't return to the project without understanding them. A lot of that boiled down to imagining their parents, hometowns, and evolving living situations. Details such as Quartz's father thinking she's the Smartest Little Girl to Walk The Earth and favoring her over her brother; Leander's mom knowing she could have been a world-famous pianist if she hadn't married his father; or Lark's parents being beloved and popular community figures who loved each other in a very mutually respectful and replicable manner. The moment you're writing out page-long explanations of how a character's parents met or what their childhood apartment looked like, even of maybe 5% of what you write even makes it into the narrative, you still know stuff about who the character is that you didn't before.

TL;DR - Context, both world- and character- driven, and a sketch of a Compelling Idea that becomes a real person through discovery-based writing and deliberately asking yourself important questions. Characters who are Ideas and not People is a lot of what I react against in my current fiction projects, a teenage writing habit of mine that I think all but the best of us probably fall prey to. I think the easiest way to make them People is being able to answer questions about the world your characters exist in and the people who occupy it with them. Everything is relational, and enhancing the resolution on one part of it enhances everything else with it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

big ol’ invicncible spoilers, watch the show first trust me you’re not missing anything if you don’t read this post

I’ve never talked about a cartoon or tv show before but I’ve gotta say that people who say there’s ‘no complexity’ to Omni-Man’s character just tick me off.

I mean, listen, he’s totally a villain at least in the cartoon adaptation (I’ve not read the comics, going to consider them separate entities for the sake of argument), but he’s far from a two dimensional sussus amogus imposter blindly readying the planet for invasion.

I whole-heartedly believe that Omni-Man enjoyed being a superhero, saving lives. I believe his friendship with the tailor guy was real, I believe he respected, admired even, the Guardians of the Globe, cherished his relationship with Debbie, and enjoyed living among humans. The brief interaction with Darkwing and The Immortal when the Mauler Twins attack the White House is so sincere right? Like, it seems to me he respects them, the jokey “you’re welcome” when he saved Darkwing, the “I had him” when he saved the guard Immortal was going for, that wasn’t necessary of him. He had no real reason to be playful and cordial with them, he could have been distant and still gained their trust easily (I mean, Darkwing was a jerk and they loved him). The brief moment of shock and unresponsiveness when Mark revealed that he’d finally gotten his powers? I honestly believe that was a moment of disbelief. I think he hoped Mark’s powers wouldn’t manifest, hoped he wouldn’t have to continue his mission. That pause was him coming to terms with the end of things. The realization that he would have to hurt people he respected, finish his mission, and end his time as a father, author, and superhero.

When he collapses after murdering the Guardians of the Globe, the look on his face isn’t just exhaustion from the fight, it looks to me like shock. Disbelief. I don’t think he wanted to kill the Guardians, I think he hated doing it, but it’s what he was bred for. He was born and trained from childhood for thousands of years to weaken a planet from within, prepare it for invasion. Earth had superheroes, naturally a pretty noteworthy obstacle for an invasion, so he, in his mind, had no choice but to kill them. And notice that most of his kills are pretty... clean? He goes right for Immortal’s head, ditto with Aquaris and Green Ghost, snaps War Woman’s neck, kills Darkwing in one clean move, tears off Martian Man’s heart(? is that a heart?), crushes Red Rush’s head (which seems slow because of Red Rush’s perception of time being RIDICULOUS compared to our own, that horrific scene only lasted like a second for the rest of the characters). He goes for quick, clean kills, minimizing pain. Maybe its just brutal, soldier-like efficiency, since the greatest superheroes on Earth cannot be allowed to get any good hits in (they nearly killed him as it was), but what if it was a desire to not prolong the suffering of people he genuinely liked?

We see in the flashback towards the end (during the THINK, MARK, THINK! scene lmao) that he initially didn’t give two shits about humanity on a deep level. He loved and respected Debbie and his then-very-young son, but thought humans were, on a whole, primitive and dumb. But as he spends time observing them, watching their culture, interacting with them, living with them, he warms up to them. The smile on his face when Mark hits his first homerun in little league, remembering Debbie’s favourite foods, the way he laughs when he mentions how a superhero had to meet the president in a plaid supersuit, the fishing photograph with the tailor. Even after he finally reveals himself as an infiltrator, the way he talks, to me, shows respect for his adversaries even as he demeans and belittles humanity. The discussion with Cecil, the warning to ‘stay out of this’. Nolan seems reluctant to kill anybody he doesn’t have to, and seemingly acknowledges that the Global Defense Agency at the very least is a minor threat.

So, you say, why does he act so AWFUL at times?

Well, his seeming lack of emotion after the funerals for the Guardians of the Globe can proooooooooooooobably be chalked up to his alien psychology. He finished grieving, he didn’t see the harm in cracking jokes about them. Calling Debora a ‘pet’? I think that honestly would be him trying to rationalise his feelings for her. There’s a fraction of a second where he hesitates to say it, and I honestly think he’s just trying to explain to himself how he could ever love a ‘lesser lifeform’. Killing all those innocent people? In his mind that was justified to get through to Mark. He doesn’t enjoy it -- though he also doesn’t dislike it -- he just sees it as a flat necessity, no less insignificant than killing a bug (i said the man is a complex character, I didn’t say he wasn’t evil).

Don’t forget, Nolan’s genuine reasoning for bringing Earth into the Viltrum Empire is to help it. He argues that Viltrum technology can end hunger and poverty, end crime, revolutionize medicine. In his eyes, his indoctrinated eyes, he’s doing the right thing to help the people of Earth.

He still thinks he’s the hero.

‘it’s right to pity them’.

He sees humans as lesser creatures, he thinks they need protection from themselves, need to be brought up by the Viltrumites to be better. They can’t survive on their own, they’re weak and soft, they need us to reach their full potential, to find true glory in serving the might of Viltrum. Omni-Man does not see his actions as evil, he thinks he’s the good guy. He reluctantly kills the Guardians of the Globe, slaughters thousands of people, and destroys a city in order to, in his extremely twisted sense of morality, help people.

And, in the end, it is not the Viltrumite parts of Omni-Man and Invincible that end the conflict. It is Mark’s very human belief that he will, one day, get through to his dad. His refusal to give in, his undying love and determination to save people, save Nolan. It’s this that reaches Omni-Man. It doesn’t reach the tough soldier he had been for thousands of years, it reaches the small part of Omni-Man that wasn’t pretending to be human. The part that is Nolan Grayson. The part that, despite still seeing them as primitive and inferior, likes humanity. It’s a human tear that leaves his eye as Nolan flies away from Earth, finally giving up and refusing to facilitate the invasion if it means killing his son, something a full Viltrumite wouldn’t hesitate to do for a second if their family got in the way of their conquest. He was changed by his time with humans.

I’m not defending Omni-Man, he’s obviously a bad guy, an antagonist, serving a genuinely evil empire, but i AM saying he isn’t some flat, boring two dimensional villain who just PRETENDED to like humanity for the twenty odd years he spent living there. I’ve seen people in youtube comments replying with “I think you misunderstand Omni-Man as a character, you see, he was simply pretending to not hate humanity, it was all an elaborate ruse, there’s no real depth and inner terminal in him at all uwu” but i think THEY misunderstand Omni-Man.

He’s not morally grey, he’s arguably not even redeemable, but he IS a complex and well written character and boiling him down to ONLY being an evil alien who tricked people into liking him just rubs me the wrong way.

but idk maybe I misunderstood him and he really IS flat and boring. Maybe his time with humanity didn’t change him at all, he isn’t emotionally conflicted, and he’s just less cool than I thought.

And despite my seeming passive aggressive language, it’s totally chill if you disagree with my personal interpretation of Omni-Man as a character, art is meant to be a unique experience for everyone, so if you see him completely differently to me that’s great! I just dislike the insistence from some people online that anybody who sees him as a deeper, more complicated character is just wrong.

also sorry for this post coming out of left field entirely lmao

#invincible#omni-man#nolan grayson#mark grayson#cecil stedman#debbie grayson#the immortal#war woman#aquaris#martian man#red rush#green ghost#darkwing#guardians of the globe#cartoon#animation#character discussion#complex characters#THINK MARK THINK#look i know this isnt unpopular#but i just wanted an excuse to write about omni-man and invincible tbh#superheroes#super powers#mauler twins#forgive me for typing so much#i like to get carried away sometimes#spoilers#invincible spoilers#big spoilers

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Bolin, The Ethical Dilemma of Highbrow True Crime, Vulture (August 1, 2018)

The “true-crime boom” of the mid- to late 2010s is a strange pop-culture phenomenon, given that it is not so much a new type of programming as an acknowledgement of a centuries-long obsession: People love true stories about murder and other brands of brutality and grift, and they have gorged on them particularly since the beginning of modern journalism. The serial fiction of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins was influenced by the British public’s obsessive tracking of sensational true-crime cases in daily papers, and since then, we have hoarded gory details in tabloids and pulp paperbacks and nightly news shows and Wikipedia articles and Reddit threads.

I don’t deny these stories have proliferated in the past five years. Since the secret is out — “Oh you love murder? Me too!” — entire TV networks, podcast genres, and countless limited-run docuseries have arisen to satisfy this rumbling hunger. It is tempting to call this true-crime boom new because of the prestige sheen of many of its artifacts — Serial and Dirty John and The Jinx and Wild, Wild Country are all conspicuously well made, with lovely visuals and strong reporting. They have subtle senses of theme and character, and they often feel professional, pensive, quiet — so far from vulgar or sensational.

But well-told stories about crime are not really new, and neither is their popularity. In Cold Blood is a classic of American literature and The Executioner’s Song won the Pulitzer; Errol Morris has used crime again and again in his documentaries to probe ideas like fame, desire, corruption, and justice. The new true-crime boom is more simply a matter of volume and shamelessness: the wide array of crime stories we can now openly indulge in, with conventions of the true-crime genre more emphatically repeated and codified, more creatively expanded and trespassed against. In 2016, after two critically acclaimed series about the O.J. Simpson trial, there was talk that the 1996 murder of Colorado 6-year-old JonBenét Ramsey would be the next case to get the same treatment. It was odd, hearing O.J.: Made in America, the epic and depressing account of race and celebrity that won the Academy Award for Best Documentary, discussed in the same breath with the half-dozen unnecessary TV specials dredging up the Ramsey case. Despite my avowed love of Dateline, I would not have watched these JonBenét specials had a magazine not paid me to, and suffice it to say they did very little either to solve the 20-year-old crime (ha!) or examine our collective obsession with it.

Clearly, the insight, production values, or cultural capital of its shiniest products are not what drives this new wave of crime stories. O.J.: Made in America happened to be great and the JonBenét specials happened to be terrible, but producers saw them as part of the same trend because they knew they would appeal to at least part of the same audience. I’ve been thinking a lot about these gaps between high and low, since there are people who consume all murder content indiscriminately, and another subset who only allow themselves to enjoy the “smart” kind. The difference between highbrow and lowbrow in the new true crime is often purely aesthetic. It is easier than ever for producers to create stories that look good and seem serious, especially because there are templates now for a style and voice that make horrifying stories go down easy and leave the viewer wanting more. But for these so-called prestige true-crime offerings, the question of ethics — of the potential to interfere in real criminal cases and real people’s lives — is even more important, precisely because they are taken seriously.

Like the sensational tone, disturbing, clinical detail, and authoritarian subtext that have long defined schlocky true crime as “trash,” the prestige true-crime subgenre has developed its own shorthand, a language to tell its audience they’re consuming something thoughtful, college-educated, public-radio influenced. In addition to slick and creative production, highbrow true crime focuses on character sketches instead of police procedure. “We’re public radio producers who are curious about why people do what they do,” Phoebe Judge, the host of the podcast Criminal, said. Judge has interviewed criminals (a bank robber, a marijuana brownie dealer), victims, and investigators, using crime as a very simple window into some of the most interesting and complicated lives on the planet.

Highbrow true crime is often explicitly about the piece’s creator, a meta-commentary about the process of researching and reporting such consequential stories. Serial’s Sarah Koenig and The Jinx’s Andrew Jarecki wrestle with their boundaries with the subjects (Adnan Syed and Robert Durst, respectively, both of whom have been tried for murder) and whether they believe them. They sift through evidence and reconstruct timelines as they try to create a coherent narrative from fragments.

I remember saying years ago that people who liked Serial should try watching Dateline, and my friend joked in reply, “Yeah, but Dateline isn’t hosted by my friend Sarah.” One reason for the first season of Serial’s insane success — it is still the most-downloaded podcast of all time — is the intimacy audiences felt with Koenig as she documented her investigation of a Baltimore teenager’s murder in real time, keeping us up to date on every vagary of evidence, every interview, every experiment. Like the figure of the detective in many mystery novels, the reporter stands in for the audience, mirroring and orchestrating our shifts in perspective, our cynicism and credulity, our theories, prejudices, frustrations, and breakthroughs.

This is what makes this style of true crime addictive, which is the adjective its makers most crave. The stance of the voyeur, the dispassionate observer, is thrilling without being emotionally taxing for the viewer, who watches from a safe remove. (This fact is subtly skewered in Gay Talese’s creepy 2017 Netflix documentary, Voyeur.) I’m not sure how much of my eye-rolling at the popularity of highbrow true crime has to do with my general distrust of prestige TV and Oscar-bait movies, which are usually designed to be enjoyed in the exact same way and for the exact same reasons as any other entertainment, but also to make the viewer feel good about themselves for watching. When I wrote earlier that there are viewers who consume all true crime, and those who only consume “smart” true crime, I thought, “And there must be some people who only like dumb true crime.” Then I realized that I am sort of one of them.

There are specimens of highbrow true crime that I love, Criminal and O.J.: Made in America among them, but I truly enjoy Dateline much more than I do Serial, which in my mind is tedious to the edge of pointlessness. I find myself perversely complaining that good true crime is no fun — as self-conscious as it may be, it will never be as entertaining as the Investigation Discovery network’s output, most of which is painfully serious. (The list of ID shows is one of the most amusing artifacts on the internet, including shows called Bride Killas, Momsters: Moms Who Murder, and Sex Sent Me to the Slammer.) Susan Sontag famously defined camp as “seriousness that fails,” and camp is obviously part of the appeal of a show called Sinister Ministers or Southern Fried Homicide. Network news magazine shows like Dateline and 48 Hours are somber and melodramatic, often literally starting voice-overs on their true-crime episodes with variations of “it was a dark and stormy night.” They trade in archetypes — the perfect father, the sweet girl with big dreams, the divorcee looking for a second chance — and stick to a predetermined narrative of the case they’re focusing on, unconcerned about accusations of bias. They are sentimental and yet utterly graphic, clinical in their depiction of brutal crimes.

It’s always talked around in discussions of why people like true crime: It is … funny? The comedy in horror movies seems like a given, but it is hardly permitted to say that you are amused by true disturbing stories, out of respect for victims. But in reducing victims and their families to stock characters, in exaggerating murderers to superhuman monsters, in valorizing police and forensic scientists as heroic Everymen, there is dark humor in how cheesy and misguided these pulpy shows are, how bad we are at talking about crime and drawing conclusions from it, how many ways we find to distance ourselves from the pain of victims and survivors, even when we think we are honoring them. (The jokey titles and tongue-in-cheek tone of some ID shows seem to indicate more awareness of the inherent humor, but in general, the channel’s programming is almost all derivative of network TV specials.) I’m not saying I’m proud of it, but in its obvious failures, I enjoy this brand of true crime more straightforwardly than its voyeuristic, documentary counterpart, which, in its dignified guise, has maybe only perfected a method of making us feel less gross about consuming real people’s pain for fun.

Crime stories also might be less risky when they are more stilted, more clinical. To be blunt, what makes a crime story less satisfying are often the ethical guidelines that help reporters avoid ruining people’s lives. With the popularity of the podcasts S-Town and Missing Richard Simmons, there were conversations about the ethics of appropriating another person’s story, particularly when they won’t (or can’t) participate in your version of it. The questions of ethics and appropriation are even heavier when stories intersect with their subjects’ criminal cases, because journalism has always had a reciprocal relationship with the justice system. Part of the exhilarating intimacy of the first season of Serial was Koenig’s speculation about people who never agreed to be part of the show, the theories and rabbit holes she went through, the risks she took to get answers. But there is a reason most reporters do all their research, then write their story. It is inappropriate, and potentially libelous, to let your readers in on every unverified theory about your subject that occurs to you, particularly when wondering about a private citizen’s innocence or guilt in a horrific crime.

Koenig’s off-the-cuff tone had other consequences, too, in the form of amateur sleuths on Reddit who tracked down people involved with the case, pored over court transcripts, and reviewed cellular tower evidence, forming a shadow army of investigators taking up what they saw as the gauntlet thrown down by the show. The journalist often takes on the stance of the professional amateur, a citizen providing information in the public interest and using the resources at hand to get answers. At times during the first season of Serial, Koenig’s methods are laughably amateurish, like when she drives from the victim’s high school to the scene of the crime, a Best Buy, to see if it was possible to do it in the stated timeline. She is able to do it, which means very little, since the crime occurred 15 years earlier. Because so many of her investigative tools were also ones available to listeners at home, some took that as an invitation to play along.

This blurred line between professional and amateur, reporter and private investigator, has plagued journalists since the dawn of modern crime reporting. In 1897, amid a frenzied rivalry between newspaper barons William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, true crime coverage was so popular that Hearst formed a group of reporters to investigate criminal cases called the “Murder Squad.” They wore badges and carried guns, forming essentially an extralegal police force who both assisted and muddled official investigations. Seeking to get a better story and sell more papers, it was common for reporters to trample crime scenes, plant evidence, and produce dubious witnesses whose accounts fit their preferred version of the case. And they were trying to get audiences hooked in very similar ways, by crowdsourcing information and encouraging readers to send in tips.

Of course the producers of Serial never did anything so questionable as the Murder Squad, though there are interesting parallels between the true-crime podcast and crime coverage in early daily newspapers. They were both innovations in the ways information was delivered to the public that sparked unexpectedly personal, participatory, and impassioned responses from their audiences. It’s tempting to say that we’ve come full circle, with a new true-crime boom that is victim to some of the same ethical pitfalls of the first one: Is crime journalism another industry deregulated by the anarchy of the internet? But as Michelle Dean wrote of Serial, “This is exactly the problem with doing journalism at all … You might think you are doing a simple crime podcast … and then you become a sensation, as Serial has, and the story falls to the mercy of the thousands, even millions, of bored and curious people on the internet.”

Simply by merit of their popularity, highbrow crime stories are often riskier than their lowbrow counterparts. Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker about the ways the makers of the Netflix series Making a Murderer, in their attempt to advocate for the convicted murderer Steven Avery, omit evidence that incriminates him and put forth an incoherent argument for his innocence. Advocacy and intervention are complicated actions for journalists to undertake, though they are not novel. Schulz points to a scene in Making a Murderer where a Dateline producer who is covering Avery is shown saying, “Right now murder is hot.” In this moment the creators of Making a Murderer are drawing a distinction between themselves and Dateline, as Schulz writes, implying that, “unlike traditional true-crime shows … their work is too intellectually serious to be thoughtless, too morally worthy to be cruel.” But they were not only trying to invalidate Avery’s conviction; they (like Dateline, but more effectively) were also creating an addictive product, a compelling story.

That is maybe what irks me the most about true crime with highbrow pretensions. It appeals to the same vices as traditional true crime, and often trades in the same melodrama and selective storytelling, but its consequences can be more extreme. Adnan Syed was granted a new trial after Serial brought attention to his case; Avery was denied his appeal, but people involved in his case have nevertheless been doxxed and threatened. I’ve come to believe that addictiveness and advocacy are rarely compatible. If they were, why would the creators of Making a Murderer have advocated for one white man, when the story of being victimized by a corrupt police force is common to so many people across the U.S., particularly people of color?

It does feel like a shame that so many resources are going to create slick, smart true crime that asks the wrong questions, focusing our energy on individual stories instead of the systemic problems they represent. But in truth, this is is probably a feature, not a bug. I suspect the new true-crime obsession has something to do with the massive, terrifying problems we face as a society: government corruption, mass violence, corporate greed, income inequality, police brutality, environmental degradation, human-rights violations. These are large-scale crimes whose resolutions, though not mysterious, are also not forthcoming. Focusing on one case, bearing down on its minutia and discovering who is to blame, serves as both an escape and a means of feeling in control, giving us an arena where justice is possible.

Skepticism about whether journalists appropriate their subjects’ stories, about high and low, and about why we enjoy the crime stories we do, all swirl through what I think of as the post–true-crime moment. Post–true crime is explicitly or implicity about the popularity of the new true-crime wave, questioning its place in our culture, and resisting or responding to its conventions. One interesting document of post–true crime is My Favorite Murder and other “comedy murder podcasts,” which, in retelling stories murder buffs have heard on one million Investigation Discovery shows, unpack the ham-fisted clichés of the true-crime genre. They show how these stories appeal to the most gruesome sides of our personalities and address the obvious but unspoken fact that true crime is entertainment, and often the kind that is as mindless as a sitcom. Even more cutting is the Netflix parody American Vandal, which both codifies and spoofs the conventions of the new highbrow true crime, roasting the genre’s earnest tone in its depiction of a Serial-like investigation of some lewd graffiti.

There is also the trend in the post–true-crime era of dramatizing famous crime stories, like in The Bling Ring; I, Tonya; and Ryan Murphy’s anthology series American Crime Story, all of which dwell not only on the stories of infamous crimes but also why they captured the public imagination. There is a camp element in these retellings, particularly when famous actors like John Travolta and Sarah Paulson are hamming it up in ridiculous wigs. But this self-consciousness often works to these projects’ advantage, allowing them to show heightened versions of the cultural moments that led to the most outsize tabloid crime stories. Many of these fictionalized versions take journalistic accounts as their source material, like Nancy Jo Sales’s reporting in Vanity Fair for The Bling Ring and ESPN’s documentary on Tonya Harding, The Price of Gold, for I, Tonya. This seems like a best-case scenario for prestige true crime to me: parsing famous cases from multiple angles and in multiple genres, trying to understand them both on the level of individual choices and cultural forces.

Perhaps the most significant contributions to post–true crime, though, are the recent wave of personal accounts about murder and crime: literary memoirs like Down City by Leah Carroll, Mean by Myriam Gurba, The Hot One by Carolyn Murnick, After the Eclipse by Sarah Perry, and We Are All Shipwrecks by Kelly Grey Carlisle all tell the stories of murder seen from close-up. (It is significant that all of these books are by women. Carroll, Perry, and Carlisle all write about their mothers’ murders, placing them in the tradition of James Ellroy’s great memoir My Dark Places, but without the tortured, fetish-y tone.) This is not a voyeuristic first person, and the reader can’t detach and find joy in procedure; we are finally confronted with the truth of lives upended by violence and grief. There’s also Ear Hustle, the brilliant podcast produced by the inmates of San Quentin State Prison. The makers of Ear Hustle sometimes contemplate the bad luck and bad decisions that led them to be incarcerated, but more often they discuss the concerns of daily life in prison, like food, sex, and how to make mascara from an inky page from a magazine. This is a crime podcast that is the opposite of sensational, addressing the systemic truth of crime and the justice system, in stories that are mundane, profound, and, yes, addictive.

#true crime#adnan syed#media#ethics#The Way We Live Now#culture#andrew jarecki#james ellroy#criminal justice#detective fiction

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

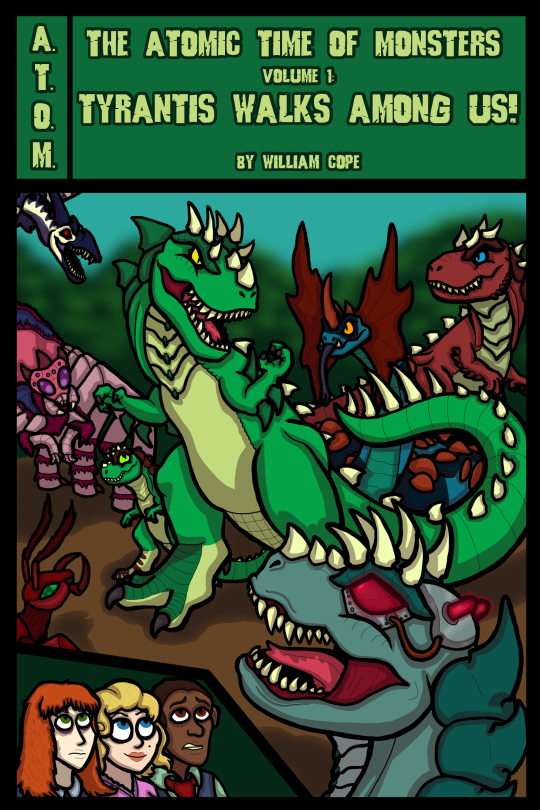

It’s time for more A.T.O.M. Volume 1 trivia! Today we’re gonna talk about the monsters!

- Tyrantis is my oldest OC, having been made when I was six. The original pitch for him was that he was what would happen if a Tyrannosaurus rex had been mutated by an atom bomb instead of a godzillasaurus, which is why his name is a portmanteau of Tyrannosaurus and “Gigantis,” one of Godzilla’s less well known alternate names. It’s also why he breathes fire. However, because Tyrantis was also meant to be Godzilla’s sidekick at the time, his powerset was specifically less impressive than Godzilla’s - i.e. normal fire instead of nuclear fire. While he’s become more and more his own character as time went on, I decided to make that limitation a law of his character - Tyrantis is not meant to outshine the monster icons that came before him, but rather stand alongside them.

- Tyrantis was originally represented in my childhood playtime by a Jurassic Park juvenile T.rex, which is why I’ve adamantly kept his head looking very Jurassic Park-y in all his incarnations (huge goofy overbite, big eyebrows, bumpy nasal ridge, etc.).

- One of my earliest attempts to tell Tyrantis’s story as a kid involved the Lego Movie Maker stop motion program. While I never figured out how to get the buggy program to work, my failed attempt to make a Tyrantis movie at the time did have one lasting effect: the Lego T.rex toy that would play him happened to have these big spikes on its arms (because they were originally made for the Lego Dragon figure), which all subsequent incarnations of Tyrantis would incorporate as one of his important design details.

- The armored scutes on Tyrantis’s curved neck and his crocodilian tail are direct homages to Ray Harryhausen’s Gwangi (and countless other stop motion theropods), while his pronounced “cheek” bumps are taken from multiple monster suits by Eiji Tsuburaya. Add in the obvious Stan Winston Jurassic Park t.rex head and you have a design that pays homage to three of my favorite monster creators.

- One of my goals in writing Tyrantis was to keep his status as a both an archetypal monster AND child’s wish fulfillment character intact. He’s a big, green, fire-breathing reptile, the kind countless children have imagined, and while he’s rowdy and loves fighting other monsters (because that’s what monsters do), he’s also kind and protective of the weak. Part of the fun of writing this final version of A.T.O.M. was juxtaposing this innocent, child-like character against a more serious and complicated world.

- Gorgolisk, the gigantic prehistoric snake monster in the story, is almost as old as Tyrantis. Her original incarnation was called Hydra and, true to her name, had seven heads instead of just the one. While her design and name has changed a lot since then, her status as the cool and collected counterpart to impulsive and foolhardy Tyrantis has remained a constant.

- Ironically, while Gorgolisk is no longer explicitly connected to Dr. Lerna as she was in earlier drafts, the two remain very similar in personality.

- Ahuul, Tyrantis’s pterosaur-inspired antagonist, is also fairly old, though like Gorgolisk he went through a name change. Ahuul’s first incarnation was named Kongamatu, and was a kaiju-fied version of the African pterosaur cryptid of the same name. Other names he tried out included Wendigo, Ahool, and Ahul, the later two belonging to another cryptid that is sometimes believed to be a pterosaur, and his final name is obviously a play on that same monster (though the novel gives it a different origin).

- Earlier versions of Ahuul weren’t quite as nasty, but still began as antagonistic creatures.

- Bobo, the giant friendly spider, began as a character I made up in a jokey and heavily embellished autobiographical comic I made in middle school. The original Bobo was a significantly smaller giant spider (about the size of a car) that lived under a trapdoor in the walkway to my house. It was a REALLY dumb comic, but I liked the idea of Bobo as this protective spider-monster, and eventually she found a home as a kaiju in Tyrantis’s story.

- The name “Bobo” is inspired by the song “Boris the Spider” by The Who. I made it cutesier because, to my teenage brain, that made it all the more hilarious.

- Tyranta and Tyrantor owe their existence to both The Lost World: Jurassic Park and Gorgo, as a young me thought that the key to making a monster sympathetic was to give it a family. While I now think that isn’t strictly necessary, being a loving father and devoted spouse has been a core part of Tyrantis’s character for a long time, and his family is one of the traits that makes him stand out from most other monsters.

- The fact that Tyranta is slightly larger and stronger than her male counterparts was inspired by a popular idea among dinosaur fans that the female tyrannosaurids were larger than the males. There isn’t a great deal of scientific evidence supporting this claim, but it’s persistent nonetheless, and I think it makes for an interesting dynamic. Plus monogamous species tend to have larger females than males, and Tyrantis and Tyranta are definitely monogamous, so in a way I’ve stumbled into scientific accuracy after all!

- The first incarnation of MechaTyrantis hails from the short but influential Lego era of the story, and was made to be roughly the same size as the green Lego T.rex toy. His flesh and blood head, tail, and feet are all design elements that can be traced to that custom Lego model, as are the rough shape of his distinctive Gravity Manipulation Canons (which originally came from one of the early Lego Star Wars sets).

- No one will believe me, but MechaTyrantis’s nature as a cyborg instead of a full-on robot predates the existence of Kiryu by quite a few years. Rather than fight it, I decided to lean into the accidental similarities in the published novel.

#The Atomic Time of Monsters#Tyrantis#Gorgolisk#Bobo#Tyranta#Tyrantor#MechaTyrantis#kaiju#A.T.O.M. Trivia

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

With Crystal of Storms, Rhianna Pratchett Helps Reboot Fighting Fantasy Roleplay Books

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

Writer Rhianna Pratchett, known for video games including the Tomb Raider reboot and the Overlord series, returns to an early staple of role-playing gaming with Fighting Fantasy. Pratchett’s book, Crystal of Storms, takes players into a fantasy police procedural on a floating island.

She’s one of only two guest writers for the franchise, and the first woman to put her stamp on it. With a strong career of her own and the legacy of her father Terry’s Discworld series, her quirky take on the fantasy procedural is part of Scholastic’s revitalization of Fighting Fantasy.

Developed in the 80s, Fighting Fantasy works as an introduction for kids to fantasy roleplaying. Players can use dice or flip the pages to roll different outcomes for their characters. Items, stat trackers, and alternate origin stories make Fighting Fantasy more complicated than a choose-your-own-adventure book but still easy to play solo.

“We’re delighted to welcome Rhianna to the world of Fighting Fantasy,” Ian Livingstone, co-creator of Fighting Fantasy, said. “Her charming writing style and clever, imaginative world-building in Crystal of Storms is a new take on the genre and a joy to read.”

Den of Geek called Pratchett to talk about humor, fantasy, narrative design for games, and more.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Den of Geek: How does a Fighting Fantasy game work?

Pratchett: Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson created Fighting Fantasy back in the 80s. I read it as a kid. You choose where the adventure goes. You make choices as you encounter different scenarios, characters, and monsters. You pick up potions and weapons, various things that can help. Just like in an RPG game, except it’s all text. For the choices you make, you turn to different sections of the book and see what the results of those choices are.

You can use traditional dice, and there’s a section at the back where you can record your stats and rolls to see how a battle will turn out. You can record your gold, the provisions, any code words, things like that. But you could also use the pages themselves as dice rolls because every page has a pair of dice with numbers on it, so if you don’t have dice, randomly flick through the book and stop on a page, and on the corner it will tell you what the dice roll will be. Which is very handy. There’s something nice about using physical dice while you’re playing it, so it’s very interactive.

As an older adult you don’t have dice about as much as you do as a kid! I had to go out and get dice and pencil when I was doing research!

What was your process for world building for the archipelago of Pangaria?

I came up with the overarching idea based on an amalgamation of a few things. There was a bit in Gates of Death (a previous Fighting Fantasy book by guest author Charlie Higson) where you interact with goblins that have a flying machine. I thought that sounds pretty cool. I wonder if you could go bigger with that? I was also reading a news story about cloud formations that look like cities. No one knows why! Those things merged in my head, the city in the sky, the goblins, and their flying machine.

It had been a long time since I’d read classic Fighting Fantasy books. I wanted very specific areas I could develop in the same way you’d develop a level for a game. That’s why I had the archipelago and the different islands that all have different roles within the economy of Pangaria. So you’ve got the water island, the farming island, the technomancy island. Technomancy, which is halfway between magic and technology, is what underpins the whole of Pangaria. It’s what makes the islands fly, what powers the storm crystals you have in these portable wings you can wear to fly around different islands. There are these little goblin airbuses that go between islands as well. I wanted to create distinct areas I could personalize, make unique, and have fun with and create original monsters for as well as delving into the archives and coming up with some classic monsters that hadn’t been seen for a while. It was a good mixture of that.

A lot of it I did on the fly. Ian Livingstone told me how hard it was. I thought he was joking with me. “Oh, he’s just trying to scare me,” but it is very hard. If Ian Livingstone tells you that, it probably is hard given that he’s written so many of them. Ultimately your writing will not end up in a linear form. Each page has multiple sections, all of which are numbered. You need to make sure you have enough sections, about 400 sections, and that they’re covering enough words, and they’re not next to each other. All that can be quite difficult to manage. Fighting Fantasy authors have different ways of doing it. Ian writes it out freehand. I started doing that, then I did a flow chart. That was becoming too time consuming, so I started an Excel document with colors for different sections, and the pages, and the different islands. Which more or less worked. So I devised my own system for how it works.

I had the great Jonathan Green, who is a Fighting Fantasy author who’s written a lot, helping guide me through the world. Particularly with things like boss fights, how to structure fights in the Fighting Fantasy style, and how to do things like have little moments within the boss fights where you can roll the dice to do something specific.

The thing that underpins Pangaria is a combination of the goblins’ tech and creatures called stormborns, that are a bit like jinns as we know them, but not like jinns in the Fighting Fantasy world. They’re like elementals that live in and around the Ocean of Tempests, which is where Pangaria is situated. It’s floating in the eye of the storm, protected from the outside world by this giant tempest. The stormborns harvest storm crystals from the tempests, which are used to power the goblins’ tech.

You start off as a member of the Sky Watch, which are more or less like the police force, but Pangaria is largely peaceful. You don’t have much to do and you’re a little bit bored and wishing for adventures. You find yourself the only Sky Watch member left. All the other recruits are on the Nimbus island, which crashes into the ocean at the start of the story.

All the islands are named after clouds. There are five islands, around a sixth central island. The sixth crashes out of the sky and you have to visit the other islands and find out what happened to the island, how to get down there, who’s responsible for it. It’s a fantasy police procedural set on a floating archipelago, basically.

Did your history writing video games help in putting this book together?

Certainly the level design aspect. I wouldn’t call myself a game designer, although I would call myself a narrative designer, which is kind of a subset of game design. I have had to pick up a lot along the way, and I have had to work on games which were very level based. Each level has its own unique aesthetic and personality and characters and things like that. So I’m used to creating mini-worlds within worlds. So that really helped.

Usually, I don’t get the opportunity to write fights as part of my job when I work on games because that’s usually done with whoever’s dealing with the gameplay mechanics. That’s not usually me, unless there is a substantial bit of narrative embedded into the fight. For smaller, indie projects like Lost Words: Beyond The Page, my last game, I had quite a big role in coming up with some of the mechanics and level design aspects because they were so heavily tied to the narrative in that game. I’d been working on it for three or four years on and off. My brain had developed in a way that when I took on this project I understood things on an intrinsic level that maybe if I hadn’t been in video games for so long I wouldn’t have understood so easily. I understand the pace of games and I could bring that to the table.

Also brevity! In games you have to learn to be succinct. If you’re dealing with lots of little sections and you have to write 400 or so sections, you have to be economical about your words.

What is your history with Fighting Fantasy?

I played them when I was 8 or 9 years old. I used to get them out from my local library. In fact I think I got a threatening letter from my library when I was a child because I’d held on to the book so long. I thought they were threatening me with taking me to court!

As the first female author in the series, do you bring an element to it that girls and women would particularly appreciate?

Ian and Steve have been bringing the books back over the last couple years, and bringing in guest authors like Charlie and myself to work on. It’s fun that there are still areas in this world where women haven’t done anything before. It’s nice but nerve wracking to be the first woman to write one. Our illustrator [Eva Eskelinen] as well is the first woman to illustrate for a Fighting Fantasy book.

It’s hard to know because I don’t have any frame of reference other than being who I am. A lot of what I did in games narrative was quite new for women to get involved in. There were obviously women who were doing great work in fantasy games in the 80s, Roberta Williams, Jane Jensen, and Christie Marks who did the King’s Quest games, Conquests of Camelot, and the Gabriel Knight games. There are a lot of women who worked in design who were also doing narrative.

I think it’s more than I bring my own sensibilities to it. It’s very difficult to separate what’s me and what’s particularly female. I had to write in the Fighting Fantasy tone, which is quite standard fantasy tone. Not particularly jokey. I probably stretched jokiness and irreverent charm to about as much as I could…I don’t think it’s intrinsically female. It’s intrinsically me.

Your contribution is described as “narrative rich.” What do you focus on when it comes to giving a unique identity to your own writing style?

As a writer you have to be open to all kinds of information and stories. You need to read. You need to be interested in people and the world. You need content to generate content. You need to pay attention to the news and read around the genre you’re writing for. You need to go as broad as you can, to educate yourself, exercise your imagination and your creativity as a result of that. So I don’t have any particular tools except all the stuff that goes into my brain and comes out. I don’t really know what happens in the middle. Lots of stuff goes in and stories come out!

I’m often working with stories that exist in part. In games, I coined the term “narrative paramedic” many, many years ago to describe the job a game writer sometimes does where they’re basically handed a box of narrative body parts and you have to assemble them into a story. Or the story is dying very badly and you have to save it. Narrative paramedics often get called in very late in the day. They’re patching up the story, not writing it from the ground up.

When I was a games journalist I never met a game writer. I might have met some designers that did some writing. Writing was done literally by whoever had the time and inclination to do it. It could’ve been designers, or producers. It wasn’t done by a professional as a standard. That has changed very much. Game studios are building out their narrative teams. But we’re still working out how to fit writers into the process both in house and freelance. … You still get narrative paramedic jobs, but they’re thankfully less common because more studios have writing teams or relationships with writers.

It was Mary DeMarle, who’s narrative director now at Eidos Montreal, who coined the term narrative designer when she was working on the Myst games. Narrative designer is different to a writer, although those jobs are shared. Writers deal with what you might think of as traditional writing, the story, the dialogue, the cinematics, the VO, letters, documents, graffiti, that kind of thing. Whereas a narrative designer is concerned with how the story gets to the player. How the player will experience it. It could be the player experiences it through cinematics, or level design and art and there’s no traditional narrative. They’re usually a conduit between the writers and the rest of the design team and make sure the needs of the design team are communicated to the writers. Some do writing themselves, some don’t, but they’re really there to make sure the story gets into the game in the best way possible.

I really like putting humor in games and quirky weirdness that is intrinsically me I think. I worked on all the Overlord games with Triumph Studios and Codemasters years back, and they were fun to write for. There’s not always room to do that in games, but wherever I can. It’s a product of what I read, what I listen to, how I think, how I was raised, what I’ve experienced.

I’m always very suspicious if writers really have a handle on what is going on inside their heads to produce the stories. It feels a bit magical. Which I know is not helpful, because people would like “you need to do this and this.” There are some of those! But a lot of it is your mind as a writer, your mind you have developed through being open to the world, and letting that percolate. Eventually in the narrative gumbo things will float to the top.

I’m a very multitasking writer. I’m not good at setting hours. I work all hours, mostly during the evening, and its very antisocial but I have a very understanding partner. I wish I was a writer who could get up, start a day at a particular time and end at a particular time. But I’m not. But it works for me!

Were there any particularly fun ways you worked the mechanics into the story, or anything that would only work in Fighting Fantasy?

When you’re working in games, you have a fear that someone’s going to press x or spacebar and skip the cutscene or whatever that you’ve spent weeks or months of your life slaving over. It can just be skipped. That’s a risk and the nature of your job. With Crystal of Storms I know readers are engaged. They’re there for the words. Although every player of Fighting Fantasy knows basically that you go to the different sections and learn all the outcomes and choose which one you like best. You learn to have about four different fingers in different sections of the book so you can flick between things to see what the outcomes are.

What games are you playing nowadays?

I always like The Long Dark. I always joke with the ghost dad in my head, because my dad was a big gamer. Sometimes I play games because I can tell they’re the kind of game he would like. I have a particular fondness for wilderness survival games because when I was growing up my dad and I lived in the countryside on the edge of a valley, and my dad would take me out walking and teach me about what plants and berries and fungus were edible and which weren’t. Or, I guess, everything is edible once.

He would teach me a light smattering of wilderness survival, and I was always interested in books that touched on that as a kid. So I really like games like Don’t Starve. I play that a lot with my partner. My partner actually got me a beefalo plushie from Don’t Starve!

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

I’ve also been playing Among Trees, and I’ve started to do a lot of the harder challenges in The Long Dark. We have a bit of a heat wave here in the UK so it makes me feel slightly cooler to be playing a game set in the Canadian snowy wilderness. I am somewhat obsessed with that and my poor partner has to endure tales of how I escaped wolves, and how I shot a moose with one shot and then two wolves got me! The emergent narrative as well as the existing narrative Hinterland [Studio] has done with their story chapters are really, really good. I’ve turned to outdoor games where you’re trumping around in the wilderness in isolation.

Crystal of Storms is out on October 1st. Find out more about it here.

The post With Crystal of Storms, Rhianna Pratchett Helps Reboot Fighting Fantasy Roleplay Books appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3jvyA2N

0 notes

Text

The Slash That Sailed One-Thousand Ships

So I saw a jokey Achilles/Patroclus post going around and, being the viper of myth & snake of history that I am, I wrote a jokey comment in response to it...

then decided to post it as a jokey minorinterlude instead...

and THEEEEeeeennNN.........

it turned into This monstrosity :T

SO:

(and with the proviso that my knowledge of this era and subject is by no means Perfect, and also that I could be hilariously forgetting important Bits)::

On the one entirely metaphorical hand: By the forms of "Classical" aristocratic(!important to note!) Greek culture, Achilles was clearly the eromenos(”the beloved”. The passivity is intentional) as the younger lover. English-speakers dealing with Achilles and Patroclus have, almost universally, age-switched them in treatments of the subject, which is a not-so-subtle hint at which view is conventionally favored in English-speaking cultures, if you ask me.

On the other entirely metaphorical hand: Homer was “writing” centuries before the “Classical” Era for a non-Classical audience, and their relationship, while easy to interpret through this model, clearly doesn’t follow it. Did the erastes/eromenos dynamic exist in Homer’s time? I don’t know. Was it as formalized as it was in the Archaic and Classical Era, both socially and symbolically(eromenosian hairlessness and erastean beardedness, etc)? I don’t know. If it was formalized, did it even take the same form? I don’t know.

The classical Greeks(and later Romans) (!!!)whose writings we have(!!!) generally lack an interest in “historical accuracy”, and mostly treated historical writing as polemical. By which I mean: they wrote about history to make arguments about the present, had absolutely zero or near-to-zero compunctions against making shit up or passing on as fact fictions convenient to them, and typically -unless tradition remembered otherwise and thus would declare them assholes immediately for saying it- assumed their social mores were the past’s social mores. So it’s entirely possible that Patroclus, while older, was still the eromenos in a Homeric Greece where social position[1] or relative prowess in battle mattered more in defining formal sexual relationships between aristocratic men[2]. Indeed, it’s entirely possible that the whole “conflict” about the nature of their relationship is the result of Athenian writers reading it through a Classical lens that was entirely alien to the relationship-dynamic Homer meant to convey(and which, presumably, was conveyed more clearly in the traditions surrounding and predating the Illiad which have been lost to memory, and to an audience steeped in them). And the thing is: that Classical Greeks argued against the most obvious romantisocial interpretation, as many must have for Plato to feel it necessary to write them into Symposium to refute them, shows that the issue was much more complicated in practice than formal Greek social institutions suggest.

On the third entirely metaphorical hand: The modern innovation of the power-bottom presents, I agree, an excellent compromise for both sides of this issue, entirely the fault of egocentric Athenians or not, though potentially an anachronistic one u_u

On the fourth entirely metaphorical hand: There were obviously other models of m/m love in Classical Greece. In Thebes, erastes and eromenos fought beside each other, as grown men and as social equals, with Achilles and Patroclus as a possible inspiration for this, or an example of the Homeric(meaning age not literature here) traditions that inspired the stories about them(of which only the one remains). The Sacred Band(the unit built around this tradition of military male homosexuality) was also reported to be drawn from all social classes purely on the basis of skill[4]. So, while described with the same terms, it clearly had different dynamics: it wasn’t restricted to the aristocracy; it was an equal relationship rather than one between mentor and student; and it was between two grown men, not between a grown man and a teenager.

Notes under the cut:

[1]Patroclus was Achilles’s henceman or follower. You could also say he was from a lower-status(but still aristocratic and royal) “branch family”. In modified modern terms, he was a “half-cousin” of Achilles: they shared a great-grandmother, Aegina, who had a child by Actor(a mortal king) named Menoetius, and a child by Zeus named Aeacus. Achilles’ grandfather was Aeacus; Patroclus’s grandfather was Menoetius. Who was also semi-divine through Aegina, who was the daughter of a humble river-god, Asopus. How humble? there were FOUR Asopuses ::::| We could go whole-hog speculative on this and treat it as a metaphor for royal/aristocratic hierarchy -given that every “King” everywhere and anywhen has justified their hegemony through divine descent or writ- but I leave the decision on such speculation entirely to the Reader u_u

[2]which clearly DID NOT operate under the same rules as paiderastia which required the eromenos to be a “hairless youth”. Yes that word inspired the English word you think it did, no it doesn’t mean exactly the same thing It’s Complicated, yes these relationships were supposed to end[3] when the youth had grown an appreciable amount of body-hair because Tradition defined sex not by gender but action and a grown man being penetrated was traditionally see as “womanish”, i.e., emasculating. Greek Aristos were misogynistic shitheads.

[3]”end” in the sense that penetrative sex was supposed to end. The social relationship between “Lover”(also, Mentor) and “Beloved” was expected to continue on and be close, and “The Greek Way” of intercrural sex(between the thighs) could presumably continue. Though, obvsl, people usually have sex privately(for a value of “privately” that, in Classical Greece, includes wild drunken parties with close friends), even if this privacy was mostly a social fiction in itself given the design of Greek homes(and social nature of “privacy”), so one would assume this would be, to some extent, also a social fiction. Many continued on as they had been, many knew they did so, and many were fine with this.

[4]I’ve done very little reading on Classical Greek history outside of Athens and Sparta, and especially social-history-reading(for which there aren’t many sources anyway, from what I understand), so I’m also interested in whether or not the dynamic of the Sacred Band played out in the rest of Theban society. Like: were Theban male homosexual relationships more equal and adult than general for Greece? Was there less of a stigma on class-mixing in Thebes(class was a HUGE issue in Athenian politics, and Sparta -for all its ascetic “egalitarianism” BETWEEN “Spartans”- was a racist totalitarian slave-empire)? I should look for books that might discuss these things :T

#Classical Greece#Patroclus#Achilles#Erastes and Eromenos#Homosexuality in Classical Greece#Classical Scholarship#Homosexuality#Patroclus/Achilles#Greek Myth#analytic posts

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi guys!!! i am writing in at 10:34 instead of 10 because... i don’t know.

my dream stuck with me all day. i tried talking to real people to sort my head out but it wasn’t as helpful as i’d hoped.

i wasted a LOT of time just... doing nothing, i guess. i skipped lunch, but i knew the more meals i skip the worse i’ll feel, so i forced down like a single serving of trail mix. then i poked around for a little bit longer (didn’t even clean my apartment).

oh, i did pick up my package. and i found out that the apartment complex is charging me 96 extra dollars over my full rent every month. i started getting that sorted out but i won’t hear back from the administrator until she gets in on monday, and even then they can be kinda slow to respond.

like how i had to notify maintenance that there was a giant hole in my wall and they did nothing about it for a month so i told them again and they still did nothing so i had to fix it myself and then they came in and did nothing but leave a little flyer on my door. and also the mold in the hole had been making me sick for the whole month before that.

my toilet also seems like it’s got something in the refill pipes that gunks everything up every two weeks but i’m reluctant to put in a maintenance order. i’d rather just keep cleaning it and/or fix it myself when i get time.

eventually i dragged myself out to my bike and got on and biked over to gamestop. it was a lovely day. i experimented with using different gears but i think my bike chain doesn’t like that very much because 2nd gear is different depending on if i was in 1st or 3rd last.

i went to the grocery store and got too much again... i spent less than usual i think? i dunno the vegetarian stuff can get kinda pricey... and the cat litter is a huge hassle to get around. it makes my bike so heavy i don’t have a lot of control over it at all.

which is how i ended up getting hit by a motorcycle on my way home.

it was not going very fast. it had pulled out of a side road/driveway thing? and was blocking the sidewalk. i expected it to either not block the sidewalk or to go out into the traffic since the road was clear. i did not expect it to do neither of those things. i also could not stop the bike even though i had grabbed the brake.

he decided to pull forward when i was right in front of him and he knocked me over and then he fell over. my bike handlebar fell directly on my bag of popcorn (i’d gotten it in the hope of having something a little more filling as a snack for my lunchbox) and it exploded and it made the scariest noise i’ve ever heard while hitting the ground.

we’d fallen into the road so he and i scrambled to our feet pretty quick and i yanked my bike upright even though it was way too heavy for me to do that normally without a lot of care, especially with the 20-pound cat litter. adrenaline is a strange thing.

it’s actually really surprising i wasn’t hurt more badly than i was? my grocery bags had been wrapped uncomfortably and tightly around my shoulders since i’d had trouble getting them on my back. i was WAY HEAVIER than i normally am because of that. i fell directly on my arm and/or hand (i don’t remember the moment just before and just after the fall well at all) and i did bruise my fingers but not my arm. and i didn’t scrape my side or hip or leg. wearing jeans probably helped.

i mean like... my purse got a faceful of road. my ankle and foot hurt and my fingers on my left hand aren’t working that well if i grab anything. but i didn’t even get winded or trapped under my bulky grocery bags or the bike, which did fall on me. my muscles have become Powerful. and also the bike must have been saved by its soft landing directly on my popcorn and my bread.

a few pedestrians came by to check on us. one guy either offered me his number or asked for mine to “check up on” me. i said that wouldn’t be necessary. when i told asher about it he thought that was super weird. i wasn’t thinking very hard about it at the time but i did pretend to be less hurt than i actually was.

i took a minute to stop having a heart attack and i made sure the guy’s motorcycle didn’t break. it was actually damaged more than my bike was because i am an Unstoppable Force.

then i walked by bike to the stoplight half a block away and got on it and rode home on my injured ankle and with the bags even heavier because i’d gotten tired.

i told my classmates about it on our group chat and then i sat and avoided doing anything for like a whole hour. i got my shiny silvally and trained it. i finished up my laundry. i made a very small, very early dinner because i knew i had to eat something even though i still didn’t want anything.

then i biked to campus and got there arouuund 4:40-ish. i coasted most of the way because i really was tired. i graded! for three hours!! i finished one section!!!!!!!!!

bad. it’s maybe 10% of the work i have to finish this weekend. sorting out depression AND finances AND getting hit by motor vehicles AND adult chores like laundry AND doing my school work is too hard...

when i got to the office jennica gave me some of her candy. i revealed that i had also bought halloween candy and gave it to her and suzanne and taylor. wasn’t no one else there. i stayed in suzanne’s office even after she left for a little bit for two reasons. i didn’t feel like moving and also jennica was watching a football game and screaming at her screen. but then it got really hot in that office and taylor was tapping the floor so hard i could feel the vibrations through my shoes and hear it over my music. so i moved to my office, which also belongs to jennica.

the third time she screamed so hard my ears rang, i turned around to address her. i tried to be as polite as i could and ask her to at least keep down the screaming because it was hurting my ears. i was mostly tired of flinching every time she did it though.

so like... there were things making it hard to do work. i hope that the extra 90% of my work goes faster tomorrow. i’m gonna try to get into the office early, if i can... it’s my goal. i don’t always reach my goals. obviously.

so i biked home and had a small snack (even though i STILL didn’t want to eat anything, i could tell i was very hungry) and then it was 9:30 and i watched a 45-minute video. and then i watched another video i guess. i only have one video left in my bookmarks but it’s also 45 minutes long so it’ll have to wait for next weekend i guess.

now it’s 11. it is hard to want to go to sleep again.

it’s... rare that i remember conversations in my dreams. and i don’t remember word for word what i was talking about with those guys. thinking about learning a piano piece, wondering if he could help me, talking about siblings. i’m a lot more direct and honest in my dreams which is kind of nice as much as it is worrying. i don’t like swearing (just in general, i mean, in practice it’s usually really funny) but it seems to slip out a lot when i’m dreaming and i wonder what that says about me.

it’s kind of nice to be that... blunt, i guess, isn’t the right word. not obtuse, even if sometimes the conversations take place entirely in strange phrases that only read as metaphors or, in retrospect, really hilarious and face-slapping puns that took four hours to set up.

guess there’s not much point in lying to myself. i assume here that the dream people i encounter are, in fact, all in my head, and not anywhere else. it’s, kind of, comforting, that i don’t seem to be hiding that much from myself, if dream revelations sound more like “oh yeah that sounds right” than “wow i didn’t know i felt that way.” i love to keep my secrets but at least i know what they are, i guess?

sometimes it’s hard to discern my motivations when i talk to people, just because, it’s complicated and i feel super suspicious all the time even when i’m being really honest with my stories and goofy about jokey jokes. but i barely ever approach dream people with the intention of actually lying to them even if i keep a lot of things to myself. and that’s how i feel when i’m awake too.

i share a lot but it’s always stuff that doesn’t really matter to me. and it’s funny if i complain about it instead of really sad. other people don’t always think it’s funny too though. and i guess they pick up on the stuff i would rather keep secret even if i try to hide it.

i let my moods affect me a lot even though i don’t always want to. being in a bad mood can make something feel right that doesn’t normally feel right. like deciding to share stuff from my childhood in a way that is not even a little bit of a joke. i don’t WANT people to know i’m in a bad mood, but i want to act in a different way than usual and that tips people off maybe? because different things seem like good ideas and different things seem like bad ideas depending on how bad i feel?

i guess i can get pretty reckless when i don’t feel good. reckless socially, maybe. being unhappy or angry and NOT blowing it off as a joke or absolutely downplaying it? that’s normally terrifying!!!

like i said in our group chat i was cranky but otherwise fine. cranky was kind of a vague way of not-saying i spent an hour refusing to leave my desk or eat or do anything that might help me make use of the daylight i had left because even though i didn’t FEEL scared (i don’t feel anything really) i knew my body was scared. does that make sense?

i feel like that a lot. where i’ll recognize a situation where i would normally have this sort of response, so i’ll kinda go through the motions of responding the way i remember how to, but i don’t feel the emotion that would normally cause me to respond that way. i can’t tell if i’m just acting out of habit, or an attempt to be “normal,” or i am actually feeling things and my brain is telling me i’m not for some reason, or what. maybe all of those, and maybe other things too.

the only emotion i really recognize when i feel it is anger. i know when i’m angry. but that’s about it.

i can’t tell if i’m lying or not. like of COURSE, i MUST feel happy sometimes. but thinking about memories that are supposed to be happy i don’t... have a word for how i feel. i know it’s not happy, but it must be something, and happy seems to be the only option there. but i keep having the need to say “i don’t feel anything.” it’s disorienting, knowing that something should be there and finding that it’s not, but it must be, because where else would it be? where did my emotions go? did they leak out of my ear or something? are there holes in my pockets?

like i have panic attacks, i KNOW i’m having a panic attack, i’m experiencing all the symptoms... except for the actual thought “i’m feeling panicked.” the panic isn’t there. just the headache and the trouble breathing and the shaky hands and the restlessness. so it must be panic. but where is the panic???

am i overthinking it? is it normal to overthink it?

trying to categorize and intellectualize all my emotions is probably what’s making them so hard to feel. you don’t think about all the individual muscles you have to stimulate in order to grab a pencil. you just want to grab the pencil and then it is grabbed. if you think about HOW to grab the pencil it’s easy to get caught up in the “wait. what?” part of it. you just gotta do it naturally.

maybe that’s why meditation helps so much with some people. lets you stop thinking about the “how” and the “why” and just kinda, “do” it.

wikipedia has some interesting things to say about it. “ speculating about one's own problems rather than experiencing them and attempting to change. “

“ Alternatively the therapist may unwittingly deflect the patient away from feeling to mere talking of feelings, producing not emotional but merely intellectual insight[23] an obsessional attempt to control through thinking the lost feelings parts of the self. “

heh. a long time ago i was talking about how badly i wanted to stop feeling things. guess i got what i wanted. but i didn’t really stop feeling things so much as only sometimes feel bad things and stop feeling good things altogether.

maybe that’s an answer then. stop thinking about it so dang hard. things will happen. i don’t have to think about how to make them happen in order to actually make them happen. emotional things, moreso than adult outside life things. i have to consider my approach toward getting my rent payments back if i want to actually get them back. it’s not advice for every situation...

but instead of thinking so hard about how to move my arm that i hurt my brain, i should probably just move my arm.

that requires dealing with a lot of emotions that i don’t really want to deal with because it’s not useful to me right now. it won’t be helpful for me right now to be furious and miserable all the time for a few weeks. there’s never really a good time for it... when i had time, i was at home, so i didn’t have the right space for it. now i got the space, sort of, but absolutely no time at all.

i guess i was, after all, happy at the restaurant last night, hanging out with my friends, not thinking about whether i was happy or not. it wasn’t pure happy, but it was there. contentment. i don’t remember it now, very well, but i wasn’t thinking about it that way at the time. moods can do a lot toward changing your perception of what things felt like and what seems like a good or bad idea.

i guess, the thing here is, i don’t feel safe enough to feel all my emotions. i mentioned it to keegan yesterday, when we were talking about drugs, just because that’s where the conversation went. i said i never really wanted to alter my state of mind like that because i hate the idea of not being in control of what i say. he said “interesting” but wouldn’t elaborate.

loosening up would make it harder to pay attention to everything and run with (more or less) one behavior strategy. i know how it is to be drunk, let alone connected to the universe. even then i have to be really careful, especially around my family. if something happened and i didn’t have all my faculties... it’s not safe.

and now, snoopy pooped directly next to my desk. so i cleaned that up. it’s after 11:30. i should sleep.

one thought. i think that’s why my moods feel so... horrible. it feels horrible to be in a different mood than usual and i hate myself when i feel differently from “nothing” because i feel like that makes me act differently. and i feel like i can’t afford that. being angry makes me feel like i’m going to slip up and say something i don’t actually want to say. being happy feels like it makes me less careful. because who cares! things are good!! these people are good too!!!

and being angry is like, “everyone should know how much my life sucks because i’m so miserable and i want someone to acknowledge me.”

i crave that sweet validation. i shouldn’t need it. my life is real whether people believe it or not. even *i* don’t want to acknowledge most of this stuff normally.

i was a little mean today, at the office. meaner than i intended. well, i intend to be 0 mean, so like, 2 mean is too much for me. some things that were supposed to be jokes were said with just the wrong amount of edge. i hope they know it’s because i was knocked over by a motor vehicle today and not because i am angry with them.

and like... being angry isn’t an excuse to be snippy. i shouldn’t take it out on them. i just didn’t really have any patience for screaming in a small enclosed echoey space today.

i feel like i’m a bad person because i don’t have a better handle on my temper and who i need to not direct it at.

anyway, a good thing today. i had a lot of fun at gamestop and i had a great bike ride out there and most of the way back. i’m glad that i wasn’t badly hurt and that my bike wasn’t visibly damaged. we’ll see how the gear shift holds up. it was already acting kinda weird today before the crash. i’ll take it in next weekend after this grading problem is taken care of and maybe my class schedule is adjusted.