#post-war soviet one is actually rather interesting but i like the theme already

Text

Not sure anyone is interested (or unaware as I was), but if you're going through abstinence for a certain Dutch actress and can content yourself with less than a leading role, there are at least two films up on yt that I've found...

#post-war soviet one is actually rather interesting but i like the theme already#the other one is a bit too ambitious i think. also contains more male nudity than i'd like#BUT there's a scene where's she's lying in the middle of three half-naked ladies so there's that L O L#also. singing!!#not tagging this at all. if you know you know#and if everyone else was already in the know and i am not contributing anything then forgive#i had a few totally free days a few weeks ago and accidentally found and watched these. thought i'd share#they have subtitles btw

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Space based story with prison camps: problematic parallels?

Trigger warnings:

Holocaust

Unethical Medical Experimentation (in the post and resources)

ivypool2005 asked:

I'm writing a sci-fi novel set on Mars in the 25th century. There are two countries on Mars: Country A, a hereditary dictatorship, and Country B, a democracy occupied by Country A after losing a war. Country A's government is secretly being puppeted by a company that is illegally testing experimental technology on children. On orders from the company, Country A is putting civilian children from Country B in prison camps, where the company can fake their deaths and experiment on them. (1/2)

My novel takes place in one of the prison camps. I am aware that this setting carries associations with various concentration camps in history. Specifically, I'm worried about the experimentation aspect, as I know traumatic medical experimentation occurred during the Holocaust. Is there anything I should avoid? How can I acknowledge the history while still keeping some fantasy/sci-fi distance from real experiences -- or is it a bad idea to try to straddle that fence at all? Thank you! (2/2)

We are far from being the only people to have suffered traumatic medical experiments..

--Shira

TW: Unethical Medical Experimentation (in the post, and all of the links)

Medical experimentation in history

Perhaps without intending to, you have posed an enormous question.

I will start by saying that we, the Jewish people, are not the only group to have unethical, immoral, vicious experiments performed on our bodies. Horrific experimentation has been conducted on Black people, on Indigenous people, on disabled people, on poor people of various backgrounds, on women, on queer people... the legacy of human cruelty is long. Here are some very surface-level sources for you, and anyone else interested to go through. Many, many more can be found.

General Wiki Article on Unethical Human Experimentation

US Specific Article on Unethical Human Experimentation

The early history of modern American Gynecology is largely comprised of absolutely inhumane experimentation, mostly on enslaved women (with some notable exceptions among Irish immigrant women)

An Article on Gynecological Experimentation on Enslaved Women

I also recommend reading Medical Bondage by Deirdre Cooper Owens

The Tuskegee Experiment

First Nations Children Denied Nutrition

Guatemala Syphilis Experiment

Unit 731

AZT Testing on Zimbabwean Women

Project MKUltra

Conversion Therapy

Medical Experiments on Prison Inmates

Medical Interventions on Intersex Infants and Children

Again, these are only a few, of a tragic multitude of examples.

While I don't feel comfortable saying, as a blanket statement, that stories like this should never be fictionalized, it feels important to emphasize the historicity of medical experimentation, and indeed, medical horrors. These things happened, in the real world, throughout history, and across the globe.

The story of this kind of human experimentation is one of immense cruelty, and the complete denial of the humanity of others. Experimentation was done on unwilling subjects, with no real regard for their wellbeing, their physical pain, the trauma they would incur, the effect it would have on families, or on communities. These are stories, not of random, mythical "subjects," but of human beings. These were Black women, already suffering enslavement, who were medically tortured. These were Indigenous children, who were utterly powerless, denied nutrition, just to see what would happen. These were Black men, lied to about their own health, and sent home to infect their spouses, and denied treatment once it was available. These were Aboriginal Australians, forced to have unnecessary medical procedures, children given brutal gynecological exams, and medications that were untested.. These were inmates in US prisons, under the complete control of the state. These were prisoners of war. These were pregnant people, desperate to save their fetuses, lied to by doctors. These were also Jewish people, imprisoned, and brutalized as part of a systematic attempt to destroy us.

The story of medical torture, of experimentation without any meaningful consent, of the removal of human dignity, and human rights, is so vast, and so long, there is no way to do it justice. It is a story about human beings, without agency, without rights, it's the story of doctors, scientists, and the inquisitive, looking right through a person, and seeing nothing but parts. This is not some vague plot point, or a curiosity to note in passing, it is a real, terrible thing that happened, and is still happening to actual human beings. I understand the draw, to want to write about the Worst of the Worst, the things that happen when people set aside kindness, and pick up cruelty, but this is not simply a device. This kind of torture cannot be used as authorial shorthand, to show who the real bad guys are.

On writing this subject - research

If you want to write a fictional story that includes this kind of deep, abiding horror, you need to immerse yourself in it. You need to read about it, not only in secondhand accounts, and not only from people stating facts dispassionately. You need to seek out firsthand accounts, read whatever you can find, watch whatever videos you can find. You need to find works recounting these atrocities by the descendants, and community members of people who suffered.

Then, when you have done that, you need to spend time reflecting, and actively working to recognize the humanity of the people this happened to, and continues to happen to.

You have to recognize that getting a stamp of approval from three Jewish people on a single website would never be enough, and seek out multiple sensitivity readers who have personal, familial, or cultural experience with forced experimentation.

If that seems like a lot of work, or overkill, I beg you not to write this story. It's simply too important.

-- Dierdra

If you study public health and sociology, it is often a given that the intersection of institutional power and marginalized populations produces extreme human rights abuses. This is not to say that such abuse should be treated as an inevitability, but rather to help us understand, as Dierdra says, how often we need to be aware of the risk of treating our fellow humans poorly. Much of modern medical history is the story of the unwilling sacrifices made by people unable to defend themselves from the powers that be. Whether we are talking about the poor residents of public hospitals in France during the 18th century whose bodies were used to advance anatomy and pathology, to vaccine testing in the 19th century, to mental asylum patients in the 20th century who endured isolation, lobotomies, colectomies and thorazine, one can easily see this pattern beyond the Holocaust.

Even when we shift our focus away from abuse justified by “experimentation”, we have many such incidents of institutionalized state collusion in abuse that have made the news within the last 20 years with depressing regularity. Beyond the examples mentioned above, I offer border migrant detention centers and black sites for America, Xinjiang re-education sites and prisoner organ donation in China, Soviet gulags still in use in Russia, and North Korean forced labor camps (FLCs) for political prisoners as more current examples. I agree with Dierdra that these themes affect many people still alive today who have endured such abuses, and are enduring such abuses.

More on proper research and resources

Given that you are going to be exploring a topic when the pain is still so fresh, so raw, I think you had better have something meaningful to say. Dierdra’s recommendation to immerse yourself in nonfiction primary sources is essential, but I think you will also want to brush up on many established works of dystopian fiction featuring themes relating to state institutions and the exploitation of vulnerable populations. While doing so, read about the authors and how the circumstances of their environments and time periods influenced their stories’ messages and themes. I further recommend that you do so both slowly and deliberately so you can both properly take in the information while also checking in with your own comfort.

- Marika

#holocaust#holocaust tw#prison camps#oppression#tragedy exploitation#torture tw#resources#death tw#abuse tw#asks#history

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSB crew & friends fundraiser

Dear Listeners,

I hope you are all well and looking after each other, especially those who need the most help. These are very worrying times but all we can try to do is offer comfort and kindness to each other.

As a band, we are in the very fortunate position of being ok financially for the next few months - most bands larger than us are probably in the same boat. One group of people who aren’t as fortunate, though, are touring crew members and musicians; they don’t have the benefit of PRS and PPL payments, streaming income, record sales income, advances against future records and so on.

Even though we had no gigs announced for this year we’d like to do our best to help those we work most regularly with, a group of around 10 to 15 people. All of the below items are being sold by me personally and any funds raised will be placed into an emergency PSB crew and musician fund, to enable anyone who needs help to take advantage of any available money. In the absence of any help from the government (as at lunchtime on March 17, anyway) it seems the least we could do. One of our most regular crew members has lost 14 weeks of work, already; clearly that is going to have a devastating impact, which is why we are doing what we can to help. (We have also made various behind-the-scenes efforts, too, to the extent to which we are able to afford to.)

In the event that none of our crew or session players needs assistance, we will find a suitable charity to donate this money to. Either way it will all end up going to a good cause, and none of it is for the band.

Obviously an unprecedented number of people are going to struggle financially over the coming months - to those with uncertain short-term financial futures who, in normal circumstances, would dearly love some of these items, we can only apologise. It’s not a competition - one group of struggling people isn’t more important than another, but these are people with whom we regularly work and communicate and who are part of our broader family, and we feel obliged to try to help them.

To try to accommodate those without the financial resources to buy these items off the bat, we’re running a raffle for one of the copies of EP One. See below for more details.

HOW THIS WILL WORK

If you’re interested in any item, please email [email protected], clearly stating which item(s) you’d like to buy. I am doing all of this manually so there is a chance the item will be gone by the time you email - apologies if so. I will try to respond as quickly as possible.

Some of the prices may seem high, but they are for the most part very rare PSB items and they are also the last that I have of most of them, so I am trying to get the most out of what I have in order to help others.

The sealed auction will run as an email auction until Sunday, March 22. I will hopefully be able to post the record on Monday, March 23. To place a bid, please email [email protected], clearly stating that it’s for the sealed auction and the amount you’re offering.

The raffle will run until Sunday, March 22 too. Tickets are virtual and are £5 each, to enable those with less disposable income to bid on an extremely rare item (after this fundraiser I will only have 2 left, from an original 250, and they won’t be re-pressed). You can buy more than one ticket but please do so in multiples of £5. If you are interested in taking part, please email [email protected] and clearly state the number of tickets you’d like to buy. You will be emailed further instructions.

Again, I am doing all of this myself, so please do bear with me if demand is higher than I anticipate.

ITEMS FOR SALE

First off - a word about test pressings! They are exactly what they sound like they are, ie pressings sent from the vinyl plant to us for approval or, indeed, rejection. They are often slightly poorer quality than the final version, for various boring reasons, and in some cases some of these have actually been rejected by us for being poor quality. But the value in these items doesn’t lie in their fidelity, rather their scarcity, so hopefully you won’t be expecting a pristine listen, rather an extremely rare edition of a cherished record.

Ok, here we go:

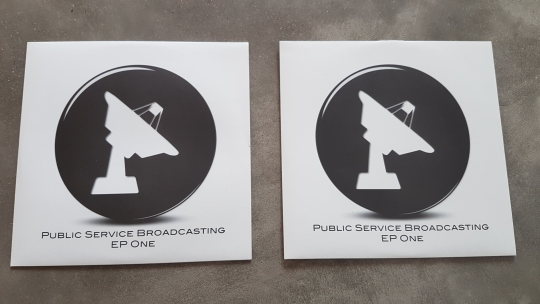

2 x copies of EP One

This is the first PSB vinyl release ever, pressed on 10″ in only 250 copies. After this fundraiser I have 2 more, forever, so they are extremely rare. They regularly go for upwards of £150 on eBay.

One will run as a sealed auction - please send your name and your highest bid to [email protected]. The auction will close on Sunday at 7pm GMT.

The other, to allow those with less disposable income to take part, will be a virtual raffle. Tickets £5 each. You can buy more than one ticket but please do so in multiples of £5. If you are interested in taking part, please email [email protected] and clearly state the number of tickets you’d like to buy. You will be emailed further instructions.

NB - both items have ever-so-slight damage to the covers so they are not pristine! They’ve been in a cardboard box that was taken to numerous gigs and festivals in 2010 and 2011 with me desperately trying to flog them to uninterested parties, before The War Room came out and they started selling online!

TEST PRESSINGS

The following are rare test pressings of various albums, EPs and so on. There are a very limited number of copies available and it’s first come, first served. Please also read the disclaimer on audio quality above. I will try to update this list as they sell, but please don’t be disappointed if you email me and they’re already sold.

Dispatch will probably happen sometime next week (March 23 onwards) provided the postal service is still working; if it isn’t, I will post them as soon as is feasible.

THE RACE FOR SPACE - PLASTIC INNER SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£100 each + p&p

THE RACE FOR SPACE - REPRESS, PROPER SLEEVE 3 of 4 SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£100 each + p&p

We had to get TRFS re-pressed from a different master in 2018 so had new test pressings. I have 4 of these newer versions, 3 of which have proper, sealed sleeves.

EVERY VALLEY SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£100 + p&p

INFORM - EDUCATE - ENTERTAIN SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£100 each + p&p

WHITE STAR LINER SOLD OUT

SOLD OUT!

£75 each + p&p

To buy, email [email protected] - also let me know if you’d like it signed. NB - this test pressing was rejected so it is not great quality, but it is extremely rare!

THE WAR ROOM SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£75 + p&p

PEOPLE WILL ALWAYS NEED COAL (RSD 2018 REMIX RELEASE) - SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£75 each + p&p

THE RACE FOR SPACE - REMIXES SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£75 each + p&p

LIMITED EDITION VINYL

These are all, with the exception of the TRFS remix release, limited editions that have sold out (I think!). I am happy to sign any of them.

SIGNAL 30 RSD 2013 7″ SOLD OUT!

Extremely rare. Orange vinyl, backed with New Dimensions in Sound.

SOLD OUT!

£100 + p&p

ELFSTEDENTOCHT PARTS 1 & 2 RSD 2014 7″ SOLD OUT!

Very rare.

SOLD OUT!

£80 each + p&p

THE OTHER SIDE PICTURE DISC - RSD 2016 7″ SOLD OUT!

NB because this is a picture disc, the audio quality isn’t great - that’s the nature of the medium. It looks amazing though! Backed with the Datassette remix.

SOLD OUT!

£50 + p&p

GO! 7″ SOLD OUT!

Backed with the Errors remix.

SOLD OUT!

£50 each + p&p

THEME FROM PSB 7″ SOLD OUT!

SOLD OUT!

£50 + p&p

PROMO & EARLY CDs

ROYGBIV (FIRST OFFICIAL SINGLE) SOLD OUT!

Backed with a different version of Lit Up, not the album version. Rare.

SOLD OUT!

£50 each + p&p

THE WAR ROOM (ORIGINAL RELEASE) SOLD OUT!

From back before we had a distributor so I was still selling and posting these myself - relatively rare although a few hundred were made up. In a plastic CD wallet.

SOLD OUT!

£50 each + p&p

ORIGINAL / RARE STOCK OF PSB VINYL

EVERY VALLEY (CLEAR INDIES VERSION) SOLD OUT!

Still sealed, limited numbers were pressed up and these are 2 of the last 3 I have.

SOLD OUT!

£50 each + p&p

THE RACE FOR SPACE - REMIXES SOLD OUT!

On orange vinyl. One has slight damage to the shrinkwrap. Price is based on being expected to be asked to sign them!

SOLD OUT!

£25 each + p&p

To buy, email [email protected] - also let me know if you’d like it signed.

POSTERS

GREEN MAN 2018 TRIPTYCH SCREENPRINT SOLD!

NB - this has different text to the image above - instead of ‘Informing...’ it has Green Man Festival and the date of the show (I can’t find the original image). It was a limited edition run.

SOLD!

£50 + p&p

THE RACE FOR SPACE DOUBLE SIDED A2 POSTERS SOLD OUT!

No image, sorry, but we have a handful of these left. They’re on decent, thick paper, A2 size, one side has the USA cover and one side the Soviet cover. Happy to sign as required.

SOLD OUT!

£30 each + p&p

To buy, email [email protected].

That’s it for now - thanks a lot for any support you can help us extend to our folks.

Yours hygienically,

J. Willgoose, Esq.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

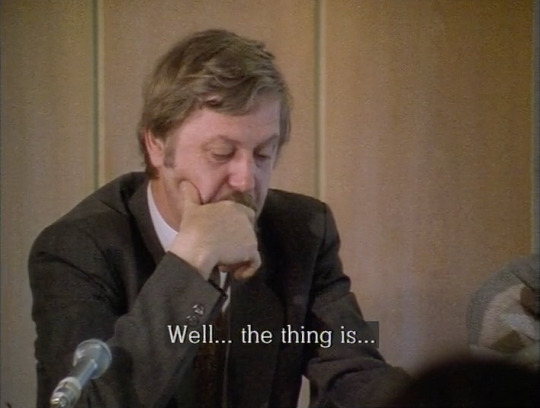

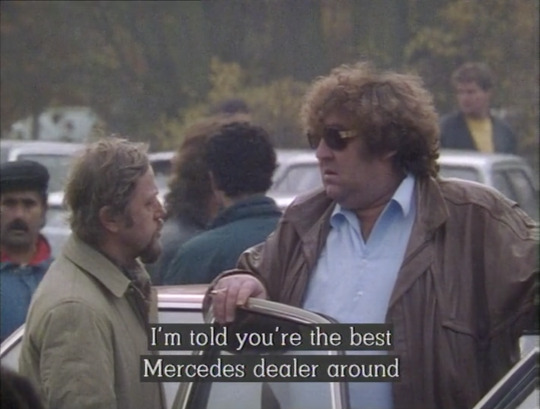

Cold War (2018) | Directed and Written by Pawel Pawlikowski

Before getting into Cold War, as a prelude, I’d like to mention a funny documentary the filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski released back in 1991 called Dostoevsky’s Travels. It follows the great-grandson of the famous Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky who died in 1881. Fyodor is generally known as one of the greatest writers of all-time and possibly one of the first modern psychologists, deeply probing the human soul in his work.

Great-grandson Dmitri drives a tram in Leningrad, Russia and agrees to go on a speaking tour about his “prophet” Grandfather. He doesn’t do this to pay his respects, but only because he dreams of scraping together enough money to buy a used Mercedes to impress his friends. And he is OBSESSED with buying a Mercedes and knows nothing about his Great-Grandfather.

He talks to crowds of intellectuals and hardly has anything to say about his kin Fyodor and just wants to get paid. He buys one Mercedes and it breaks down immediately. He then buys another at the end of the documentary and it gets stolen by bandits. As the doc progresses you see Dmitri is a bit of a numb-skull and a scoundrel.

I liked it due to the irony of Dmitiri’s complete uncaring attitude towards Fyodor’s highly regarded esteem, and obviously this absurd infatuation with acquiring a used car as a status symbol compared to his novelist grandfather, who is held up so highly for his spiritual profundity and depth.

It’s a great piece of work no one has heard of...part-cautionary Capitalist tale at the end of the Soviet Union, while Cold War is part-cautionary Communist tale post World War II.

Official Trailer for Cold War

youtube

Intro and Technical Specs

To start, my main fear of writing about films I love is that it will suck the joy out of the film itself by looking at it so closely. I have only written in depth about two films, and thus far, am finding it to be the opposite. When going under the microscope, I am just becoming more aware how great a truly well-made film is when breaking it down.

Cold War may be the most beautiful black-and-white film I’ve seen. The category Amazon has placed it in is “Arthouse Drama”. Amazon Studios also is the distributor of the film. My guess is because it did very well at the Cannes Film Festival and Pawlikowski won the Oscar for his previous film Ida in 2013. Sometimes they get it right.

To give some more context, I am very familiar with Ida and studied it for research for making my latest short film. I found it interesting Pawlikowski implemented a particular style similar to filmmaker Paul Schraeder’s book, “Transcendental Style in Film”. One aspect of this style pertaining to Ida is the cinematic framing for the action and not moving the camera until the end. He framed his subjects in a squared 4:3 aspect ratio while leaving lots of headroom, sometimes leaving them in the bottom corner of the frame, which carried over to Cold War. I don’t exactly know why he does this, but I have some theories that I will flesh out within the post in depth.

While watching, I immediately noticed the grain in the 4K version. I looked it up and the film was shot with an Alexa digital camera and also a 35mm film camera, so apparently they were able to mimic film grain with the Alexa in post to match. A 32mm lenses was used for almost all the shots. According to Pawlikowski it was because this focal length closely mimics the viewing width of the human eye and allows a wide space of action that can fit around the subject(s) in the frame.

Similar to Ida, there is no non-diegetic music in the film (music added outside of the film’s music itself) until the closing credits, reminiscent of the French director Bresson.

Opening in Rural Poland

The film opens on the hands of a man playing an instrument that resembles bagpipes, looks handmade and I assume is indigenous to Poland. The camera tilts up to reveal a bright-eyed rural man, and eventually pans over to another interesting looking character playing a violin as they sing together.

We soon learn that Wiktor (one of the protagonists) is traveling with two others (Irena and Kaczmarek) and they are recording various forms of folk music unique to the Polish people. Kaczmarek immediately degrades this type of music as “possibly crude” or “too primitive” immediately marking a divide in perspective compared to Irena and Wiktor, who visibly enjoy interacting and recording the villagers’ authentic music.

They soon come to a house where a unique-looking dirty village girl sings a song not accompanied by any instruments. She has deep-set eyes and looks slightly haunted, and the lyrics of the song are about unrequited love.

Not a happy song.

Wiktor and Irena are enraptured by the raw singing and are recording this. In contrast, Kaczmarek disinterestedly eats soup in the next room, spoon klanking against the bowl, probably interfering with the recording.

Kaczmarek is representative of the Communist State for this film, high on bureaucracy and lacking in soul.

The song being sung by the little girl is a huge part of the film as a whole. Little do we know (and probably not evident to most who have seen the film) the lyrics tell the story of what happens between the protagonists we are about to follow in the film. The song is called Dwa Serduszka (Two Hearts) and is an authentic Polish folk song like much of the music in the movie.

After watching for the first time (I commonly do this) I went online to look up background information and found a very well-made youtube video essay describing the song as being the “Leitmotif” for the film. Leitmotif is a term defined as “a recurrent theme throughout a musical or literary composition, associated with a particular person, idea, or situation”.

In this case, the song operates as a direct pointing of what is to happen. The song pops up several times throughout the course of the film, forecasting the fates of the two protagonist lovers, Wiktor and Zula, who are brought together by music.

This “forecasting” I believe goes deeper. It’s as if it is pre-determined. Pre-determined due to the current political environment in Poland and the two characters’ difference in personality and upbringing. Also, most importantly, is because they love each other in a way that seems beyond their control and not a choice, eventually becoming impossible for them to live life without one another. The leitmotif reminds us throughout the film of Wiktor and Zula’s inability to escape their fate, which is already etched in stone by powers beyond their will:

Two hearts four eyes

Crying all day and night long

Dark eyes, you cry because you can't be together

You can't be together

My mother told me

You mustn't fall in love with this boy

But I went for him anyway and love him until the end

I will love him until the end

youtube

Folk Ensemble

Now we are at a large building which looks to still be in the rural area. Auditions are going to be held here for singers and dancers for a folk ensemble performance. A couple of trucks haul the commoners in and Kaczmarek gives a stately speech to the bunch before cutting inside to everyone waiting to audition for Wiktor and Irena.

We then meet Zula waiting. She elects to audition with another girl, naively, rather than shine in the audition solo. They enter the room to sing for Wiktor and Irena. Wiktor is immediately transfixed and asks Zula to hold on and asks her to sing another song alone.

She sings with an authentic, untrained beauty. We also see her feistiness here. It’s obvious Wiktor is smitten and she is marked down to be selected as one of the singers after they exchange a parting look.

By now, the framing style of the cinematography is noticeably unique compared to other films. As mentioned in the intro, characters are often framed with lots of headroom and sometimes placed in the bottom of the frame, leaving it mostly open space. My theory on this is that the environment the characters inhabit are shaping their destiny more than the characters’ own free will, therefore their heads are often seen at the bottom with action on top and around them.

For example, Communism looms larger than the individual, tamping he or she down (literally) to the bottom of the frame. Not only Communism, but their uncontrollable love for one another, the characters’ upbringing and the people around them with their general wants and needs. These factors shape their present and future more than their own willful, self-determination and I think the filmmaker is aware of this fatalism, yet doesn’t just come and say it because that wouldn’t be interesting. We just see that Wiktor and Zula are never able to comfortably settle anywhere with their love nor escape the love they feel for one another, making their situation impossible due to the circumstances.

In Ida, duty to God looms large and so does the characters’ Jewish unknown family past (to only name two) and the shots are framed accordingly as well.

On a broad level stepping outside of the film, what’s interesting to me is how much free will do humans actually have and how much is self-determinant? After studying the film closely, this is the deep question (not answer) that I came to that transcends the surface story.

Wiktor watches Zula from a distance outside that evening. Irena then tells him Zula killed her father and did some prison time for it. After rewatching, I suspect that Irena loves Wiktor, and there are a few subtle cues later on that I noticed as well.

During private lessons, Wiktor curiously asks Zula what happened between her and her father while Wiktor plays scales on the piano and she matches the notes with her voice. Zula says her father tried to be sexual with her so she stabbed him. It is a very matter-of-fact and short answer. Wiktor doesn’t say anything and continues playing the piano.

I’ve thought about this scene more so than any other scene after rewatching. I think it is because of the dialectical nature of Zula saying she stabbed here Dad because he tried to have sex with her, one of the darkest things you could imagine, then the slight humor of Wiktor’s reaction while seamlessly transitioning back to the softness of the piano and her soft voice syncing.

Wiktor is very watchful, internal, reserved, most likely from a more refined family and musical background. Zula is tough, spirited, tenacious and has lit a fire in Wiktor. Wiktor is tall and dark-haired. Zula is short and blonde. Opposites!

It is now time to perform for a large audience in a theatre. Wiktor conducts. Zula and about 20 other girls in Polish folk attire sing the leitmotif song that was sung by the young girl earlier. The group sings beautifully. Zula shines in front. Even Kaczmarek on the side of the stage behind the curtain seems to be in awe and carefully walks about as if not to disturb the magic.

Afterwards there is a reception. Wiktor and Irena lean against a large mirrored wall and everyone else in the room is seen in the reflection. When you first watch it, it takes awhile to figure out the orientation of the room due to the mirrored wall. I think this is the most interesting shot of the film.

Kaczmarek then gleefully enters frame and says that the performance was so beautiful, calls Wiktor a genius and says it’s the most beautiful day of his life. He really means it and is the most authentic emotion we see from him in the whole film. Previously, Kaczmarek thought all this “folksy stuff” was foolish. There is a funny moment between the three. Wiktor and Irena are obviously moved by this but not sure how to express it as the stately Kaczmarek leans against the mirror with the two.

On a second viewing, one sees Zula in the reflection staring at Wiktor the entire time.

The two make love soon after in a bathroom at the party.

The Ensemble + The State

The performance is so good, now the State wants to get involved and meets with Wiktor, Irena and Kaczmarek. The government wants to turn the repertoire into a “calling card for our Fatherland” and incorporate “Land Reform”, “World Peace” and a strong number about the “Leader of the World Proletariat”. In return the group will be held in high favor, able to travel to other countries to perform, etc. Irena and Wiktor are visibly uncomfortable with this. Irena speaks first and says thank you but the ensemble is about authentic folk art and the rural population doesn’t sing nor understand these difficult issues. Kaczmarek quickly intervenes and calls the man from the state “comrade” and says the ensemble, on the contrary, will do this after given proper direction. Irena stares him down. Wiktor says nothing.

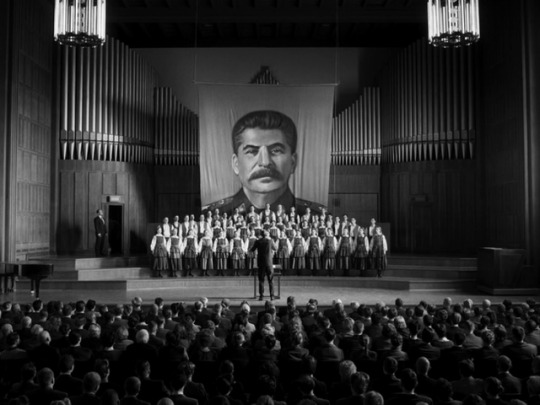

The next performance is stained by a huge tapestry of Stalin behind the singing ensemble. The tone now is more dutiful rather than soulful, as if singing a church hymn they are forced to sing. Zula’s face while singing now lacks the life it possessed in the performance before. The State must extinguish all individuality and uniqueness with the goal to homogenize. Irena’s heart looks broken in the audience. Everyone dutifully rises for applause afterwards and Irena walks out. We do not see her again in the film. Everything has changed.

The stuffiness of the singing troops is saved afterwards by a beautiful shot of Wiktor and Zula laying in a golden wheat field together at dusk. Golden?? The film is in black and white but my mind says “golden”. Birds and crickets sing.

Tranquility away from the group.

But it doesn’t last long, as they are unable to run from the larger outside factors. Zula soon confesses that she reports on Wiktor to Kaczmarek about their relationship and the things he tells her. She says it’s because she’s on probation for something and assures Wiktor that it’s nothing that will hurt him, but Wiktor gets up and walks off angrily at a loss for words.

As mentioned, the scene starts with their eyes closed as if in a dream, beyond the State, but it's inevitable that the state has to enter their relationship at some point, infecting the dream, and will remain a problem for the rest of their lives.

Zula calls him a “bourgeois wanker” as he walks away and she reacts oddly by jumping in a nearby river. As soon as she hits the water, Wiktor stops and turns around. She floats in the river and begins singing the leitmotif song.

The next shot is of the two silently sitting together again in the wheat field at nightfall with a campfire going. Zula’s hair is wet. The two just stare at each other and never say a word.

What are they thinking?

I think Wiktor is thinking that he can not escape her because of his love and that they are stuck! Zula knows this too. This is a type of love that transcends choice. Just like the State, their love controls them.

The silent shot in nature cuts to black, then diverges to a busy train station with a brass band as the ensemble leaves to go to Berlin for a show. Kaczmarek gives a stately speech to the group about their trip. Wiktor meets Zula privately in a train car and lays out a plan for their escape once in Germany to go to France. Zula is nervous she will not be able to make it somewhere other than her homeland Poland due to her inability to speak French and lack of experience. I doubt she has any family to rely on, and at the moment has the ensemble in Poland as a decent occupation. Wiktor assures her she has talent to learn and the most important thing is they’ll be together. They kiss.

The performance in Berlin is shot very uniform and proper, perhaps further pointing to its newfound soulless rigidity. Afterwards, Wiktor goes to the meeting place to cross the border. Zula remains at the reception with the comrades and Kaczmarek (as if in a trance) and never shows. Wiktor waits until nightfall and eventually stiffly walks across without her.

Defection

Wiktor is now playing piano in a cool jazz night club in Paris with a band. It is 1954. His beard is now grown out a bit and his hair messier than before.

He is now in an empty cafe at closing time and speaks French with the waitress. He seems to have assimilated well here. It is revealed he is waiting for someone. That someone is Zula. She eventually walks in and they stare at one another for a few moments.

One look at Wiktor while sitting across from her shows how much he still loves her and has missed her. The actor playing Wiktor, Tomasz Kot, really shows this wonderfully. He is very good at being still yet showing so much. Regarding the performances, this is one of the most authentic love films I’ve seen in a long time. And an expert director and writer doesn’t hurt. The film never feels sappy, in my opinion, while simultaneously remaining very romantic.

Zula doesn’t show much and stays cold during this scene, but can’t help but ask, “Are you with someone?”

Wiktor is.

So is she.

He asks if she’s happy.

She isn’t, but doesn’t say it.

Wiktor knows and walks her to the hotel.

She says she wasn’t good enough, not as good as him, to make the escape from Poland to Paris.

Wiktor says he believes love is enough.

Zula coldly kisses his cheek and then stolidly walks away.

Wiktor watches her go.

But eventually Zula breaks! She turns back around, walks quickly back and they kiss passionately for a few moments before she leaves again.

If one just read this and didn’t watch the film, you might think it seems like any other love story you’ve seen a million times. But to me, because of the authenticity of the performances and lack of constant soundtrack music, it really felt great to see these two embrace again. And I think it proves that moments in movies that may look cliche on paper can be pulled off with a skilled filmmaker and actors. Also, there’s only a few angles that the camera covers in this scene and ALL the scenes really! There’s a graceful economy and no superfluous closeups with unnecessary dialogue. And as mentioned, no outside music booms in like most films commanding you to feel something! You feel it because you feel it, not because you’re told to feel it with an over-bearing soundtrack trying to compensate for lack of performance or direction.

Wiktor now walks into his apartment, smokes a cigarette alone deep in thought, then gets in bed with his girlfriend. He tells her he’s just been with the woman of his dreams. She doesn’t seem to care and turns around to go to sleep, highlighting the lax and blase nature of their relationship and possibly Paris artist life as a whole. Wiktor then turns off the lamp and looks up at the ceiling in lovestruck thought.

We are now in Yugoslavia in 1955, which looks much more lush than I would’ve imagined Yugoslavia. Wiktor gets off the train to attend a performance of the ensemble. Kaczmarek quickly greets him at the front of the theatre and is oddly cordial and confident in a sharp suit.

Once inside, Zula sees Wiktor in the audience and looks startled.

Wiktor looks side to side and men are watching him from the aisles. He is escorted away by authorities yet remains adamant to see Zula rather than be afraid of being thrown in jail or hurt.

The first time I watched I thought he was definitely going to be thrown in prison. Kaczmarek obviously ordered the men to take him away and send him home in a train before he could see Zula, because of Kaczmarek’s interest in Zula.

Zula and the ensemble are shown singing the leitmotif song now. Zula notices Wiktor is no longer in his seat. Perhaps he was escorted out at the intermission. She sings with a melancholic intensity. The black-and-white contrast is especially beautiful here, maybe more so than anywhere else in the film. There is a black back drop and all of the singers’ alabaster skin glows, as well as their folk costumes.

Wiktor is back in Paris now and has gotten work as a Film Composer. Two years has passed since the Yugoslavia concert. While in the middle of working on the soundtrack, the side door of the sound stage opens. Wiktor is spellbound as a smiling Zula is revealed.

Zula has married an Italian so she could legally move to France. She says the marriage doesn’t count though because it wasn’t in a church. Neither seem worried about it. This time Zula does not hold back her feelings and, obviously, neither does Wiktor.

They make love.

They ride on a boat down the Seine at night past the buildings and cathedrals. They messily and drunkenly dance alone at a night club in rapture.

Heaven for a moment.

Which begins Zula’s vast transition from the performing rural ensemble in Communist Poland to a solo singer at the Paris jazz club with Wiktor’s band.

She sings the emblematic Dwa Serduszka most wonderfully here.

Order. Everything in it’s right place.

She is luminous as the camera slowly dollies around her, eventually revealing a packed club. Everyone is captivated and still. Then at the end is a lovely moment, maybe my favorite moment of the film, where Wiktor is staring at her intensely and she turns to check in with him and he gives her a nod of approval. It’s almost corny, riding the edge, but is powerful, conveying a silent understanding between the two seeing one another perfectly clearly.

Poles to Parisians

We now are at where Wiktor and Zula live, which looks like a cool version of a converted attic with a Paris view. Juliette, Wiktor’s ex, has translated Dwa Serduszka from Polish to French and Zula is unhappy with the translation, which most likely includes some self-consciousness about her pronunciation. The manner is which the leitmotif song appears here runs parallel to the first step in the descent of the relationship in Paris. Zula is defensive and anxious about the Parisian artistic circle Wiktor has introduced her to and she drinks to ease the anxiety of feeling inferior. Wiktor tells her not to because she is “charme slave” as they say, alluding to how everyone has a narrative role and label in these circles. Zula is becoming difficult and insecure. Wiktor is becoming caught up in the scene and ignorant of Zula’s dramatic change of environment.

The film director at the party looks Zula up and down when they arrive. Wiktor allows this without rebuke, most likely due to the nature of the sexually-lax Parisian art culture. Everyone is beautiful and chic at the party. Zula immediately goes for the drinks. She then sees Juliette and approaches her abruptly (yet with restraint for Zula), subtly challenging her French translation of Dwa Serduzska. Juliette calmly explains her reasoning according to the lyrics’ metaphors. It’s obvious Juliette sees through what’s happening in the situation here.. Juliette’s part is small but the actress is excellent and conveys a lot. She eventually mentions how the transition to Paris must’ve been a shock...the cafes, cinemas, shops, restaurants. Apparently Juliette sees this shock more than Wiktor does. Zula tries to play it cool here but you can see she’s flustered. This is a game she’s not used to playing. She then retorts that her life in Poland was better.

Wiktor is talking to someone and looks over and sees Zula and the Film Director sitting closely, flirting. Zula glances back over at him to see if he cares, but Wiktor stays put. Then later she aggressively confronts him about giving her story “more color”. It is apparent now that he has enhanced her Polish story to seem more dramatic in order to captivate his French friends and colleagues. Wiktor shrugs this off. Zula’s vibe is not carefree and cool like the rest of the party with her straightforward, intense rawness which creates an isolation for herself.

She sits in the bathroom now alone, drinking from a bottle, talking to herself in the mirror. She calls Wiktor a jerk, but then says she loves him. She calls herself an idiot at one point. She continues to talk in the mirror as if to console herself. And I can’t help to mention how much she looks like a young Gena Rowlands here. It reminds me of the 1968 film Faces, which is also black and white. They look so much alike, and both fantastic actresses that are blonde, voluptuous and troubled.

Gena Rowlands in Faces (1968)

Joanna Kulig in Cold War (2018)

Wiktor, unknowingly and excitedly, opens the bathroom door and says that they’re all going to the Jazz Club now. Zula says she’s a bit sad and wants Wiktor to come in the bathroom with her, but he ignores this and says let’s go. She takes a moment to herself and then it cuts to the club.

She looks miserable and wasted sitting at the bar. As we go, I am still noticing the framing I mentioned at the beginning with the subject at the bottom, but for this shot she really seems low!

Her melancholy is interrupted by an upbeat, American song (”Rock Around the Clock Tonight”) and she gets up reinvigorated and starts dancing enthusiastically with a few different guys. The camera goes handheld and is the messiest camerawork of the film (a good messy). She eventually gets sloppy and gets on the bar and almost falls and people drunkenly cheer as Wiktor exasperatedly watches.

youtube

We then see Wiktor carrying her into their room. Zula says he is no longer a man in Paris like he was in Poland, and says she and the director get along well in attempt to get under his skin further. He then sits alone in the dark and smokes a cigarette.

It now cuts to Zula in a sound studio singing into a mic in French. I don’t speak any French, but her accent and pronunciation feels correct, but her spirit is muted...and we soon see one reason why. Wiktor’s voice ominously interrupts her over a speaker behind glass in the recording booth. Now the shot is on him and he looks disheveled and dark and tells Zula they only have 40 minutes left and not to blow it. There is a deep hate in his eyes we haven’t seen yet, perhaps retribution for calling out his manhood and their recent relationship woes. An engineer and the film director are also in the booth. There is just a bad energy in the room and anyone that’s ever tried to perform anything would be able to detect how difficult it would be to bring a great performance here. The music starts back up and Wiktor looks down as if disappointed right before she starts singing.

We are at a listening party now for Zula’s record at the French Director’s apartment. Zula is standing in the middle of the room alone, listening intently as several others sit around in the background drinking champagne. Dwa Serduszka plays, but now in French.

It’s okay but not great.

It doesn’t have the soul that it had before in Polish.

I’m trying to put my finger on it, but the French seems a little stiff and the vocal track seems extra-produced. Too loud and too clear when mixed with the band’s instruments and it’s just not what it was before like the first time at the jazz club, for example.

Again, this leitmotif song is also a metaphorical indicator for the stage in the relationship. She looks over at Wiktor who is cooly leaning on the wall off to the side (maybe too cool) and gives Zula a nod similar to his nod after the jazz club performance. But this nod doesn’t have the effect it did then and seems oddly forced. The record playing here in this posh Paris apartment compared to the Polish rural girl singing at the beginning of the film is night and day. It’s obvious why, if you think about it. They’ve taken a folk Polish song, translated it to French for a rural Polish singer, then recorded and produced it in a slick Paris sound studio under difficult conditions. How could the quality not suffer a bit?! Another example of the larger outside obstacles making it impossible for them, even in a free society like Paris, France.

It cuts to them now walking home afterwards. Immediately it’s apparent Zula is unhappy. Wiktor recognizes this but apparently didn’t know while at the party. As they pass a fountain next to the street, Zula throws the record in <splash> yet continues to mostly hold her sadness in, which has become more of a depression at this point. Assimilating is one thing, but they have gotten into this habit of holding back and not being up front, maybe due to the social circles they run in now. Zula cooly mentions that the French Director has fucked her well 6 times and "not like a Polish artist in exile,” which causes an eruption in Wiktor (what she wanted) and he slaps her.

This is strange to mention but, technically, the slap doesn’t sync with the sound. Lol.

I watched this part 3 or 4 times to make sure and it just doesn’t (unless there was a lag in the internet connection). Maybe nobody else notices this, but I’ve had to edit-sync slaps, kicks and punches before many times on this very computer and immediately saw something didn’t look/sound right.

After the hard slap, Zula raises up and says, “Now we’re talking”, which is sarcastic but also the truth. Often one needs a crisis moment to break out of a behavioral habit and apparently the French translation broke the camel’s back.

The next day Wiktor frantically goes to the Director’s apartment looking for Zula. He stomps through the rooms looking for her. The Director then says she went back to Poland. Wiktor slowly walks out of the apartment with a terrified look on his face.

Wiktor has become unhinged and plays maniacally on the piano at the Jazz Club. The other band members just stop playing and look at him as he bangs on the keys in isolation. There is some slight comical levity here for a couple of seconds due to the look on the clarinet player’s face.

You assume Wiktor has lost his job. He is now miserably pumping coins in a phone booth for talk time to find out where Zula is in Poland.

Afterwards, Wiktor goes to what I assume is an embassy. A Polish man at a desk tries to dissuade him from leaving Paris and going back to Poland. You can see the Eiffel Tower outside the window as the man asks Wiktor why he would ever want to leave this place. He says Wiktor doesn’t exist anymore to Poland because he left and let down all the young people he worked with. The man takes a drink from his cup and reacts as if he’s spiked it with something strong, perhaps how he’s able to get through his job. He then mentions there is a way Wiktor can go back if he truly regrets what he has done.

The Exiles Return

It is 1959 and we see Zula back in Poland on a dreary, crowded train with peasants. Soldiers whistle at her as she walks on a snowy road. She has come to visit a very broken, gaunt Wiktor who is being held prisoner by the military for being an exile. He says he has to be here for 15 years and got off lucky. Zula gives the guard what I assume are cigarettes which buys them 10 minutes alone.

His right hand has been beat severely. They kiss and Zula says she will wait for him. Wiktor tells her to find someone else, but Zula says she will get him out.

Cuts to 1964, 5 years later. A performing Zula is on stage singing a ridiculous Latin-infused song with a black wig on, resembling a late Judy Garland. She looks overweight and drunk with her comical, sombrero-wearing band.

We now see an older Wiktor backstage with Kaczmarek who is holding an unhappy, despondent child. Kaczmarek doesn’t look like he’s aged a bit and still has a detached soullessness about him. With Kaczmarek, you wait for him to be rude or mean but he is not. He always stays at a steady, robotic hum of cordiality.

It is revealed Wiktor can no longer play music because he can no longer use his right hand. It is also now apparent that Zula married Kaczmarek in order for Wiktor to be released.

Zula now comes off stage and walks quickly toward them but drunkenly falls down. She manages to rapidly get up and falls directly into Wiktor’s arms, completely disregarding Kaczmarek and her son.

They go off to the restroom together and sit on the floor staring at one another. Zula pulls off her wig, perhaps finally able to shed this horrible identity she's had to create to survive.

She asks him to get her out of here...for good.

The two take a crowded bus and get dropped off on a country road next to a lovely field. They look slightly rejuvenated but stolid.

Early in the film, Irena and Wiktor sat in the van while Kaczmarek took a walk to take a pee. Kaczmarek then aimlessly walked into the ruins of this old church. He looked around, then left...point being we’ve seen this place before. And earlier, even Kaczmarek’s face showed a certain amount of reverence for this old church and felt the power it gave off.

Wiktor and Zula now enter this same church. There is a circular hole in the ceiling, perhaps so God can see them.

They now kneel with a candle lit in front of them on an alter with a row of white pills. They have a brief, simple marriage ceremony. They both have a glow to them. They cross themselves and mention God. They ingest the pills.

They kiss.

They then sit on a bench at dusk and look out into the field, holding hands, quiet.

You can hear the insects and an occasional bird chirp. Both have dark circles under their eyes. It’s so beautiful yet so sad.

Zula then says, “Let’s go to the other side. The view will be better there”. They stand and go, leaving an open frame. A gentle gust blows the wheat from behind where they were sitting. Perhaps God’s sigh...

This last time I watched, the ending really got me...and is powerful now as I write about it.

As mentioned in the intro, Pawlikowski’s last film Ida incorporated a particular style. Pawlikowski never moved the camera until the end of that film, so when he did the viewer would be raised up in a transcendental way as the first external music came in, lifting us from the real world for a few moments. I think he did the same thing here with Cold War in a different way. The moment of transcendence for this film comes at the end also but not with the movement of the camera but with the movement of the wheat behind the bench before cutting to black. This film is high on realism, but this gust is something otherworldly, therefore a powerful contrast from the stark, real world tribulations previously in the entirety of the film up to this point. This is what makes it so heartbreaking and beautiful and poetic all at the same time. And also, for a moment, the viewer might weigh whether the fate of Wiktor and Zula is so horrible after all.

“for my parents” appears before the credits, pointing to the fact that the story is based on the filmmaker’s parents’ true experience during that time period. Bach’s Goldberg Variations comes in and you know it’s Glen Gould when you hear the humming, which I don’t necessarily like but it doesn’t ruin the mood. Bach was also used for the ending of Ida and is also the only non-diegetic music used for Cold War.

In conclusion, I think every great film has to have a surface story that one can follow and then a large idea hidden within that story (or as a result) to meditate on which includes something deep about the human condition. With some films, one has to work to find out what that larger idea is. For future posts, I may try to specifically focus on this “larger idea” rather that breaking down the entire film. This often appears as a question, not an answer, and Cold War does this masterfully.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Éric Alliez & Maurizio Lazzarato’s Wars and Capital

❍❍❍

The book is examining Wars and Capital, with State in between as an important element to constitute the notion of politics (in a Schmittian & Greek sense). I came across the book in an exhibition titled Crossings in Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen this Christmas. The cover description of the book says: “A critique of capital through the lens of war, and a critique of war through the lens of the revolution of 1968.” I have read some of the works of Lazzarato before on notion of sovereignty, which made me interested to read this one.

The book is drawing heavily from the Nazi racist political scientist Carl Schmitt (who was going as far as demanding that all publications by Jewish scientists should henceforth be marked with a small symbol) and at the same time political works of Foucault and Deleuze. Unsurprisingly, Foucault has been criticized for being too liberal, specifically in chapter 7: “The Limits of the Liberalism of Foucault”. That’s also probably, the reason that Schmitt’s Naziism has not been mentioned throughout the whole book. Schmitt has been cited more than 35 times and one chapter is dedicated to him alongside Lenin. (Chapter 8: The Primacy of Capture, Between Schmitt and Lenin)

Alliez and Lazzarato seem to fully agree with Wallerstein’s world-system theory. Creation of the term "War of subjectivity” (which is also another fancy word for identity-politics) is a big part of the concept. Since today everyone has recognized that mostly white-boys are complaining about identity politics (for obvious reasons), writers have become creative in coming up with this new term “War of subjectivity”. However, the essence of the book is pushing for the same good-old critiques: fascism is not so different from Capitalism / Anthropocene is Capitalocene / poor White workers in England suffered as much as slaves in America (page 115, 374) / Postmodernism is bad, class-consciousness is needed… etc. etc.

“During colonization, entire peoples, after having been expropriated from their ‘life as savages,’ let themselves die off rather than fall into a slavery that could include the option of ‘free labor.’ ‘Free labor’ that the practice of working to death in workshops and manufactures brings so close to slavery itself that the Morning Star—the organ of the English free-traders—could exclaim: ‘Our white slaves, who are toiled into the grave, for the most part silently pine and die.’”

The centrality of the debt-economy concept is always present in the background of the book. Also, neoliberalism is defined as the “Global Civil War”. At some point, I questioned myself if he’s just adding the word WAR at the end of anything that capital is to blame for? War here is referred to as “the most deterritorial form of sovereignty”. “War of Subjectivity”, “War of Race, class, gender, sex, etc..”. This is also not a new strategy, orthodox white-boy Marxists have been presenting all sorts of privileges (especially “white-privilege” and “male privilege”) as a divider and a sidetrack for class wars. Borrowing from Giovanni Arrighi, they inserted a passage that clearly shows how they think about colonialism. They blame almost everything aside from the most important element: “racism”.

“The synergy between capitalism, industrialism, and militarism, driven by interstate competition, did indeed engender a virtuous circle of enrichment and empowerment for the peoples of European descent and a corresponding vicious circle of impoverishment and disempowerment for most other peoples.”

Methodologically, the book almost never steps out of Europe. Although there are some great historical references to wars and interventions in developing countries, which are also the intersection of capitalism and colonialism -examples such as Haiti’s slave rebellion of Saint-Domingue. The strength of the book is in identifying all different modes of governmental industrial militarism, or “military Keynesianism”, which enabled colonial power to quite down internal civil war during the process of colonialism. The example of Nazi Germany’s full population employment due to war was very aligned with these analyses. In section 9.6 of the book, the writers argue how post-war welfare states were able to erase the differences between war-time and peace-time, which was part of the larger debate on how “warfare states” transferred to “welfare states”. This is also the same reason I kept reading all the 430 pages of the book.

In 1957 the Nazi Carl Schmitt invited Kojeve to give a lecture addressing representatives of “Rhine capitalism” at an exclusive club in Düsseldorf. The title of the talk was "Colonialism from a European Perspective". Alexandre Kojeve, a right-wing Hegelian bureaucrat, dissected colonialism into two categories of “giving colonialism” and “taking colonialism”. He says: “Thus one must really ask the question today: how can colonialism be economically reconstructed in a "Fordist" way, so to speak? On the face of it, there are three conceivable methods, and all three have already been suggested.” Lazzarato probably turned on by this distinction, references Kojeve alongside Schmitt and replaces the word “colonialism” with “capitalism” to flatten all ambiguities that colonialism is the same as capitalism. Following the reminder that the Capitalist mode of production is simultaneously a mode of destruction.

The biggest problem that I have with the book, is that it equalizes the poor white workers of the 17-19th century in Europe to the slaves in Africa and the Americas. I call this act “theoretical colonization”. While race-blindness remains an issue in the book, it’s another problem to reduce the suffering of racial slavery in order to equalize them with Western white workers.

It’s very comical that in one instant they called Foucault’s theory “Eurocentric” and also “British-centric”!? Showing that they actually have no clue what these terms mean or where it's coming from. I agree with Spivak that to some extend Foucault’s work is slightly Eurocentric, but to hear this from a conservative white boy like Lazzarato is admittedly a bit humorous.

What came to my mind during reading Wars and Capital was the film “Lincoln (2012)”. By attacking 19th-century-liberals, the film made all the right-wing people happy (including those radicals who hated Obama and later in 2016, voted for Trump). In the background of this recollection is also the most racist film of all times "The Birth of a Nation (1925)” by D. W. Griffith, which depicted the abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens very negatively.

The writers attack the liberalism of John Locke and his support of slavery. By using this 17th-century example, they are constructing a case that centrism (the equivalent of today’s conflicts of subjectivity, which for them falls under the bigger umbrella of liberalism) is the secret motor of liberal governmentality. What Lazzarato is neglecting is not class consciousness but the fact that what constitutes an abolitionist position in the West, is not the race-blindness of homo oeconomicus but is a consciousness of race, culture, and colonialism.

Expectedly and appropriately, there is no actual examination of what racism is in the book. Similar to other orthodox leftists, writers refuse to get into any analysis of racism. They hijack the notion of racism when it intersects with wage-gab, or harsh working conditions in Europe. The only race that exists is the race of workers, problem solved! Classic!

In most cases, they use the word racism as a supplement to show the intensity of a particular concept (environmental racism, anti-labor racism, war-racism, eugenics of labor force). The ultimate aim is to reduce racism solely to market-violence. In other words, all sorts of social inequalities are a side-effect of the world’s economic system and therefore fall under the same category of social reproduction.

Éric Alliez and Maurizio Lazzarato are so orthodox that for them the radical white kids from ’60s are heterodox.

They are so orthodox when mentioning Korea, they don’t put south or north before it.

They are so orthodox that for them talking about “Black Power” is the same as talking about “White Power” because it is talking about race!

What Marxism needs is not another corps of the orthodoxy wrapped in the cutting-edge hip and fancy vocabulary, but a fresh inclusive, race-conscious framework that acknowledges people’s differences and culture prior to the call for unification of the workers. That’s the only way it can come out of the dark archaic place where it is now. Similar to Carl Schmitt critique of liberalism in the “The Concept of Political”, today, the same critique comes from people such as Bolsonaro, Trump, Putin, Erdogan, and the rest.

Here is a selection on Griffith’s work, from Sergei Eisenstein in the collection of essays, titled: Dickens Griffith and the Film Today (1944). The critique of liberalism seems to do nothing but to direct attention to the position of the writer. This passage precedes a description of a video made in mockery of Menshevik addressing in the Second Congress of Soviets.

“The role of Griffith is enormous, but our cinema is neither a poor relative nor an insolvent debtor of his. It was natural that the spirit and content of our country itself, in themes and subjects, would stride far ahead of Griffith's ideals as well their reflection in artistic images. In social attitudes Griffith was always a liberal, never departing far from the slightly sentimental humanism of the good old gentlemen and sweet old ladies of Victorian England, just as Dickens loved to picture them. His tender-hearted morals go no higher than a level of Christian accusation of human injustice and nowhere in his films is there sounded a protest against social injustice.”

The depiction of abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens in the racist film “The Birth of a Nation 1915” by D. W. Griffith.

The depiction of Thaddeus Stevens in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln (2012)″

The depiction of “The Birth of a Nation 1915” in Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman (2018)″

Bib.

De Vries, Erik. 2001. “Alexandre Kojeve, ’Colonialism from a European Perspective’ 29 (1):”, no. 29 (1) (January), 115-30.

Eisenstein, Sergei. 2014. Film Form. HMH.

Koonz, Claudia. 2003. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Schmitt, Carl. 2008. The Concept of the Political. University of Chicago Press.

0 notes

Text

A Beginner’s Guide to the Music of Aleksandr Bashlachev

By popular demand, here is a starter kit, in mostly English, to help anyone interested get into the work of my absolute favorite late-Soviet poet (/rock poet/singer-songwriter/guitarist of sorts) and one of my best beloved poets, as they say, всех времён и народов: Aleksandr Bashlachev (Александр Башлачев, or, if you’re feeling extra helpful, Александр Башлачёв— that last “e” is always pronounced “o”).

Aleksandr Bashlachev was born May 27, 1960, died February 17, 1988 (by his own hand; sometimes people count him in the so-called “27 Club”), and left around 60 poems/song texts and various recordings (audio and some video), many of which are available on YouTube (a lot of his stuff is on Spotify, too, if that’s your thing). Despite the short length of his life/career, his body of work was/is a sort of massive hidden influence on Russian rock music/the associated culture from Perestroika forward; he’s not at all well-known among the general public in Russia today, but if you’re at all interested in any of that cultural history (or if you just like Russian rock), he’s worth at least a passing familiarity.

I’m making this post partially because I just love him and want to share his brilliant work,*** but also because his poetry (like, frankly, a lot of Russian poetry) is graceful and rewarding on its own, but also densely loaded with intertextual meaning, and his performance style (messy snarly vocals, messy acoustic guitar, just a bit of a mess really, albeit a through-composed one; also incredibly intense, somehow simultaneously explosive and hypnotic— one of his contemporaries, Yuri Naumov, used the term “thermodynamic”, which I like a lot) can be a rather “acquired taste” for a lot of people, especially for those who aren’t already familiar with the stylistics of Soviet bardic music or, like, garage folk-punk or something idk. I know it took me a long time to get into his stuff, at any rate (but once I did, I didn’t listen to anything else for months).

Themes and frequent images in his work include: Russia’s fate, politics (complicated ones, for which he got “shaken down” by various “security” organizations a couple of times— they only stopped doing that in 1987), spiritual freedom, spiritual honesty (”it’s impossible to sing one way and live another”), human contact, human nature (each unique individual as part of the whole), words, bells, birds, heights, Leningrad, love (unconditional and all-encompassing: “even those I hate, I love— they’re just not good enough people to realize it yet”), the sun, the role of the artist in society, the utopian future, suicide.

Also a key point here: SashBash (that was/is his nickname) wrote not so much songs, as fellow rock musician Boris Grebenshchikov put it, as entire emotional spectacles, so when you watch a video of him singing, there’s a helluva lot to take in on top of the words and music themselves, even though he was given to keeping the mis-en-scene pretty minimalistic (just a snarly Russian dude, his guitar, and his bell bracelets). It can be pretty intimidating stuff overall, (especially if your first language isn’t Russian! and/or you’re not used to listening to poetry in Russian, in which case I’ll tell you up front that this is gonna be really rough, but ultimately totally worth it— all the time I’ve spent listening to this stuff and frantically trying to decipher it has helped me a ton with my Russian!) and it can be hard to know where to start with him because his poetry is very complex and he wrote in a couple of different “genres” (to use the term loosely); hopefully this guide will help.

So with that, here are ten (10) songs (plus important musical/poetic background) to get you started— all listed, linked, and commented on under the cut!

(i love this pic there’s something magical and telling about the combo of rocker-style leather jacket and komsomol lapel pin)

***and because this man desperately wanted to be remembered (he believed that people are reincarnated as soon as they are forgotten, and absolutely did not want to ever come back), and I get so much out of the art he made, I feel like i should try at give back at least a little, if only now, and like this

I see you’re still with us! Excellent! Поехали!

Okay, so, the first thing to know with Russian rock music is, a lot of it is based on (at least) two traditions: Western rock music (and/or the contemporary Soviet perception of it) and the Soviet bardic song genre of the 1960s and 70s (e.g. Okudzhava, Vysotsky). Russian rock tends to be heavily text-based and very individual-driven (in the sense that the lead singer of a group is often pretty much synonymous with the band— it doesn’t really matter who’s playing backup to Boris Grebenshchikov, as long as he’s there, the band is “Akvarium”), and SashBash’s work is definitely no exception to those rules— if anything he takes them to even higher levels. He worked almost exclusively alone, and a lot of his singing uses a dramatized speech-like recitative timbre; his main concern was not so much with rock music as such as with the poetry, with the Word, with expression through the Russian language (великий, богатый и проч. и проч.).

Although that artistic concern remains fairly constant throughout SashBash’s repertoire, his genre choices are less consistent. Roughly speaking, his work can be divided into short comic songs, short serious songs, and long-form epics or meditations. Texts for all the songs I’m about to list can be found at http://www.bards.ru/archives/author.php?id=1927.

Short Serious Songs: (i’m starting with these because because there’s a lot of them, because they include some of his best known songs, and also because they’re just a good place to start to get a feel for what he was about as an artist without buckling in for a twenty-minute Suffering Session— that comes later)

1. Время колокольчиков (The time of little bells) — SashBash’s most famous song, just generally a famous song, gave its name to the whole era in Soviet music culture. If you’re only going to listen to one of these, this is the one, and I highly recommend watching the linked video of him performing it (all of the videos I’ll link here are from a квартирник (apartment concert) at Boris Grebenshchikov’s place— there exist other videos of SashBash performing, but a lot of them are from large concerts which he was very uncomfortable playing, and a lot of the time it shows). Rock and roll, the role of the artist in a time of individualist upheaval, the fate of the Russian soul, and more. (3:20)

2. Лихо (Likha (Slavic mythological personification of Evil); Dashingly) — One of SashBash’s major influences on the Russian rock scene was an eye toward Ancient/Medieval Rus’ as both a source of contemporary Russia’s problems and model of possible futures, whether good or bad. These certainly weren’t new ideas in Russian literature (see: Westernizer vs. Slavophile debates of the 19th century), but SashBash’s deft, unforgettable phrasings (and passionate, agitated delivery) brought rock and roll into conversation with these classic Russian arguments, and imbued them with new urgency. (2:41)

3. Влажный блеск наших глаз (The wet shine of our eyes) — This is a bit sexier. Actually it’s all about sex. And love? And misery. And sex. (3:08)

4. Поезд №193 (Train №193) — This is a straight-up suicidal ideation song, an attempt to catch at a working definition of love, a swift pile up of quick-fix definitions, desperations. A genuinely short song with a pointedly circular structure. (2:16)

5. Вишня — This is the last song Aleksandr Bashlachev wrote whose text and audio survive. It’s a relatively melodic, life-affirming song full of fairy-tale imagery and general generosity of spirit, and the advice the singer gives to the princess character is actually pretty solid imho, especially for the 1980s (be brave, be kind, rejoice in all the things that please your heart and especially in your own freedom/will). (4:17)

6. В чистом поле дожди косые (In the open field slanting rains) — A treatment of a lot of the same themes as Время колокольчиков, but more explicitly and imagistically Russian (as opposed to Soviet), with the theme of rock and roll expanded to art/literature in general, a lot more Orthodox Christian imagery and ideas (anticapitalist), a less ecstatic and more lachrymose ambiguous ending... A lot of people claim this to be the best song he wrote. (4:57 (song starts around 30 seconds in))

Short Comic Songs: (We need a break...such as it is. Soviet humor. If you don’t know the drill, you will shortly. I’ll go ahead and put trigger warnings in for these.)

7. Подвиг разведчика (The feat of an intelligence agent (title of famous WWII movie)) An average late-Soviet asshole with a brutal hangover daydreams about going on Cold War spy adventures, is ridiculous. The linked video has a pretty solid translation in the drop-down. (4:55) TW: alcohol, food, domestic abuse, poison, homophobic slur, torture mention, guns, suicidal ideation, rape mention (casual use of term)

8. Верька, Надька, Любка (Faith, Hope, Love (girls’ names)). Sometimes subtitled Исповедь весеннего рака (Confessional of a spring crab). A very strange, ultimately sweet and oddly earnest song that starts fairly concretely and gets rapidly, cosmically out of hand. A giant confused metaphor for a single Leningrader’s personal ideological development, with metamorphoses. (5:20) TW: food, suicidal ideation, religion, alcohol/drugs, brief casual transphobia (? tbh i’ve been chewing on this line for two years now and in context i’m still not quite sure), unreality

Epics/Meditations: (ok here we go, от винта!)

9. Имя Имён (Name of Names) — A chant of shifting rhythms over a monotonous pair of guitar chords, an uncertain, lurching, demanding, overawed and underserved Credo. (8:19)

10. Ванюша (Vanyusha (boy’s name, affectionate)) — This is an arc-structured song, about trying to understand the loss of a loved one, of a child, to find or make meaning out of that suffering (Bashlachev, whose philosophy in total seems to me simultaneously very Soviet and very Orthodox Christian, believed that all personal development, and indeed all that, which is worthwhile in life, comes to us through suffering— “if your soul hurts, it means it’s working”). It uses a lot of Russian folk structures and motifs, both lyrical and musical. (11:53)

Please note that these are not my personal favorite songs of his, necessarily— just a good first set that I hope represents and can act as a starting point for his whole body of work. Thank you for reading!! Спасибо за внимание!!

BONUS SashBash singing Russian 19th and 20th century pop hits with some friends. Laughter, joy, and contextually inappropriate quotations of Lenin ensue

#by 'by popular demand' i mean one specific person asked me to make this#if anyone wants to see my essay on late soviet masculinity + this guy's work message me and i'll hook you up#music#poetry#russian music#soviet rock#russian rock#soviet music#aleksandr bashlachev#александр башлачев#русский рок#советский рок#long post#suicide#СашБаш blog#Also I hadn’t noticed this before but a lot of SashBash’s comedy takes place in khrushovsky. There’s an essay in there somewhere.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reagan: Pragmatist or Conservative Purist?

Getting Right with Reagan: The Struggle for True Conservatism, 1980-2016, by Marcus Witcher, University Press of Kansas, 448 pages, February 2020.

On January 19, 1989, as the fortieth president of the United States, Ronald Reagan, departed the White House, the New York Times reported that “no one credits Mr. Reagan with being much of an intellect,” the went on to question, “does anyone call him a hard worker or active leader.” Rather, the newspaper of record claimed, Reagan’s “strength lay in delivering lines that were arranged for him.” While such words might not be totally shocking, given the source, what Marcus Witcher reveals in his extraordinary and critical new book, Getting Right with Reagan: The Struggle for True Conservatism, 1980-2016, is that such views did not emerge merely from the left. Conservatives, too, dumped on Reagan, criticizing everything from his failure to free the market sufficiently enough to his placating of the Soviet Union. To be sure, no one, left or right, could have predicted the complete collapse of Eastern European communism over the next several months, and such knowledge might very well have reshaped even the New York Times’s opinion of the greatest president of the twentieth century.

Witcher: The Best of the Best of the Rising Generation

A recently-minted PhD in history, Marcus M. Witcher is, arguably, the finest and most impressive young scholar in a generation. As his first book it would make even the most senior scholar and historian proud. Even the opening line—“Ronald Reagan was no conservative ideologue”—is immediately captivating. From there, the book only improves. “This book recasts Reagan as a shrewd political operator who often moderated his conservative positions—much to the vexation of conservatives during the 1980s.” Rather than being ideological on fine points of intellectual rigor, “Reagan was a pragmatic conservative who understood that building coalitions across party lines was essential to effective governance.”

Getting Right with Reagan advances four arguments.

First, Witcher convincingly argues that conservatives thought little of Reagan during his two terms as president. They were, for better or worse, the first to criticize the man and find his shortcomings.