#professor but he spent over half of the class showing us his published novels and his garden. idek.

Text

advance snippet: Updating Wednesdays on Patreon (The Untamed)

So. Do I need to write an Untamed modern!AU with a college twist (Lan Xichen is a music professor in Canada) in which Wei Wuxian attempts to self-therapy himself by creating a graphic novel fantasy AU version of his life (aka the real story of Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation) and Lan Xichen attempts to rebuild his life after a toxic relationship ended? I mean probably not but has that ever stopped me? here’s the intro snippet we’ll see how things go.

(Title is tentatively Updating Wednesdays on Patreon because i don’t know what to call this thing)

~~

The first day of August finds Lan Xichen in a coffee shop, tinkering with the syllabus for his new music theory course, when his phone pings with a message.

> Lan Wangji: Brother.

> Lan Wangji: Wei Ying has asked me to inform you that he will be publishing the first collection of pages in his new graphic novel on Patreon this afternoon.

Lan Xichen smiles at Lan Wangji's tone. For all that his little brother is more verbose in electronic communication than verbal, he's always so exact.

> To Lan Wangji: Can't wait! What's it about?

The little cursor blinks for a while as Lan Wangji continues to type. Lan Xichen just hopes that his brother-in-law's creative enthusiasm isn't running up against Lan Wangji's sensibilities.

Finally, a reply appears.

> Lan Wangji: Wei Ying wants me to tell you that it is completely fictional.

This gives Lan Xichen pause. Why on earth would Wei Wuxian, or Lan Wangji himself for that matter, need to make that declaration?

> Lan Wangji: It is a high fantasy xianxia story.

Before Lan Xichen can ask why that is causing this odd message exchange, another notification pops up on his phone.

> Wei Wuxian: Lan Xichen! Lan Zhan types so slow! It's just a different art style I wanted to try out and it snowballed from there!

> Wei Wuxian: I know you follow me on Patreon so you're going to get the notification this afternoon so I wanted to warn you hahaha

> Wei Wuxian: All names and places are purely fictional. I don't really have a sword.

Another message arrives, with all the information Lan Xichen needs.

> Lan Wangji: This matters a great deal with Wei Ying.

Lan Xichen smiles at his brother's words. Lan Wangji and Wei Wuxian have been together since their junior year of high school, through a great deal of personal difficulties on both sides, and are still as fiercely protective of each other as ever. He loves them both for it.

> To Lan Wangji: Thank you for the information. I'm sure it will be great.

> To Wei Wuxian: Can't wait to see it! Anything you do is always great.

No more messages arrive, so Lan Xichen goes back to considering how to change the quiz structure of his musical theory class to avoid a marking crisis with the evaluation of his ensemble class.

Finally, as Lan Wangji gathers up his papers to leave, one last message comes in on his phone.

> Lan Wangji: Thank you for your support. We all appreciate it.

Attached to the message is a photo taken of Lan Wangji's family, he and Wei Wuxian holding Lan Yuan between them. The toddler grins at the camera, his arms around Wei Wuxian's neck. Wei Wuxian's looks at the camera, dark circles under his eyes like he's working through the night again, while Lan Wangji only has eyes for his husband.

It's so wholesome and loving that a sliver of pain rakes through Lan Xichen's heart. He's happy for his brother. His brother deserves the world. Lan Wangji deserves being loved, and to love.

Not everyone gets that. Sometimes, that falls apart.

Sometimes, for some people, love is just an illusion.

Lan Xichen tucks his phone away and leaves the coffee shop.

~~

He gets home mid-afternoon, and spends a while stowing away the groceries he picked up on his walk. The neighbourhood has several Greek and Persian markets and he's able to buy most of what he needs on foot, saving the Chinese markets in Richmond for his weekly dim sum brunches with Lan Wangji's family when he can borrow the use of Lan Wangji's sensible and economical mini-van.

He doesn't drive any more, not since—

Lan Xichen stops and puts down the bag of avocados. His mind is a funny place, bringing up the oddest things at the most inconvenient of times.

He doesn't drive anymore. He doesn't need to, using the bus and the odd taxi to transport his instruments up to the university for performances. The public transit system is so much better.

Safer.

He goes back to putting away the vegetables, pulls out a cookbook (new, spine uncreased, bought for him by Lan Qiren for his birthday) and opens it at random. He's never had coconut curry salmon before, but he has all the ingredients.

Trying new things. He's supposed to be trying new things.

The recipes says it will only take half an hour to make, so he goes up to his office and turns on his computer to check his work email. The message fly fast and furious, some about the new department head, some about class enrollment, a few from students asking if they can get onto his waitlist. He replies to the most urgent, files the rest, then checks his personal email.

The notification from Wei Wuxian's Patreon is up, so Lan Xichen clicks it.

Then he sits back, frankly impressed. He's seen Wei Wuxian's comic style progress since the boy was drawing silly cartoons to entertain Lan Wangji in history class, but even he wasn't prepared for this.

The art is gorgeous. Stylized figures, intricate period costuming, rich backgrounds – it's truly a work of art.

Then he gets a better look the two characters' faces, and laughs out loud. It's Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji, clear as day, with long hair and flowing robes. Wei Wuxian's even managed to capture that exasperated-yet-fond look Lan Wangji has whenever Wei Wuxian is being particularly loud.

The introduction is even better. "Join our hero Lan Wangji and dashing rogue Wei Wuxian as they battle deadly monsters and forge a path with demonic cultivation!"

Wei Wuxian hasn't even changed their names. True, he uses his mother's surname professionally, so Cangse Ying can't be easily tracked back, but still.

Lan Xichen wonders for a moment if Lan Wangji is okay with this, but then he notices that the project text is available in both English and in Chinese, with the Chinese written in Lan Wangji's style.

They worked on this together, then.

Trying not to think about why that makes his chest feel funny, Lan Xichen opens to the first page--

-- Which features a bruised and bloodied Wei Wuxian falling off a cliff while a horrified Lan Wangji screams after him.

Confused, Lan Xichen makes sure he hasn't accidentally read the last page first. No, this is the first. Still a little baffled, he clicks to the next page, sees the stylized banner that reads six years ago and relaxes. This is Wei Wuxian's style of using flashbacks to interrupt the narrative flow. Lan Xichen spent most of Lan Wangji's university years hearing his brother's despair for Wei Wuxian's artistic choices in essay form.

But enough about the past. Lan Xichen settles in to read the first chapter of the story, where Wei Wuxian and his siblings (Jiang Yanli drawn lovingly, Jiang Cheng with a bigger frown and more menacing eyebrows than Lan Xichen remembers) traveled to the Cloud Recesses (the sarcastic nickname Wei Wuxian gave to Lan Qiren's West Vancouver mansion) for cultivator lectures. Lan Xichen is there on the page, too, drawn taller and far more imposing than he is in real life.

The first encounter between Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji is fantastical and improbable and, according to Lan Xichen's recollection, almost completely accurate. Wei Wuxian had mouthed off at Lan Wangji at the weekend orientation camp for their new arts high school, Lan Wangji glared the boy into submission, then later that night when Wei Wuxian tried to sneak back onto school grounds with alcohol, he and Lan Wangji had gotten into a fight. Verbal, instead of with swords, and without the supernatural murder victims, but Lan Xichen remembered everything else from Lan Wangji's indignant recitation on his return home.

He keeps reading, enjoying the art and the lyrical narration, and keeps enjoying it right up to the scene when Nie Huaisang appears on the page to offer Lan Qiren a present, Meng Yao standing right behind him.

Lan Xichen doesn't remember standing up, but here he is, two feet away from his computer, heart pounding. He hadn't—Why—

What was Meng Yao doing in a story about Wei Wuxian's high school years?

Taking a deep breath, Lan Xichen makes himself return to his desk. As far as he knew, he was the one who introduced Meng Yao to Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji, when the boys were in university and after he and Meng Yao started dating--

Lan Xichen can feel his heartbeat slow, as he tries to breathe. He needs to stop this foolishness over Meng Yao. They dated before living together for a while, that was all. They broke up. It happens to people all the time.

Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji were in college for most of that time, anyway, living their lives. They barely knew Meng Yao, even if Wei Wuxian's sister married Meng Yao's half-brother. They couldn't know how badly Lan Xichen had messed up their relationship, how terrible he had been to live with. It was his fault that—

Stop.

Stop.

It's over. In the past. A story that has Meng Yao as a minor character isn't going to mess with Lan Xichen's head. He's not going to let it.

He exhales and makes himself look back at the screen.

Meng Yao only shows up a few more times. For some reason, he's the only character who isn't tagged with his own name. He's there handing over the present to Lan Qiren, standing in front of Nie Huaisang when the Wens arrive, then in two last panels in which he tells the on-screen Lan Xichen that he has to return to Nie Mingjue's side.

Lan Xichen's stomach sours. He and Nie Mingjue had been close, before Meng Yao came into Lan Xichen's life. After that, Lan Xichen hadn't had much time for anyone else. That was normal, Meng Yao always said. People in love only needed each other.

Lan Xichen picks up his phone, then puts it down. He can't ask Lan Wangji about this. It would be weird. Wei Wuxian must just be making artistic narrative choices.

The chapter ends soon after, with Wen Qing and Wen Ning welcomed grudgingly into Cloud Recesses. The next chapter is due up in two weeks, the page declares, and welcomes any comments or feedback. A few people are already posting, gushing over the art work and discussing the teaser from the opening page.

Wanting to be supportive, Lan Xichen writes a small review, complimenting the artistic style, the intricacies of the outfits, poses a query as to the different colour palettes between the first page (dark, red, menacing) and the flashback scenes in Cloud Recesses (light, airy, hopeful), then translates the comment into English and posts both versions up. If Lan Wangji is going though all the trouble of ensuring a bilingual experience, then he will too.

He should go start dinner, he really should, but some part of him is drawn back to the first panel in which Meng Yao appears. He's shorter than Lan Xichen remembers in life, the long hair and braids suiting his face.

It's been so long since Lan Xichen last saw Meng Yao. He's not sure what he's thinking. Is he wistful? Mournful? Sad?

He doesn't know. He never knows what he feels about Meng Yao, which was the problem. He's not normal about feelings. Even Lan Wangji, whose brain is a unique and complicated thing, looking for order and reason and patterns in an illogical and messy world, loves fiercely, feels passionately. Maybe he got all the love in the family, and Lan Xichen got stuck with the stunted and undergrown heart.

Stirring, he pages back to the first appearance of his on-screen twin. The Lan Xichen on the screen looks patient, kind, a smile hiding behind his eyes.

He hadn't realized this is how Wei Wuxian sees him.

He picks up his phone.

> To Wei Wuxian: What an incredible achievement! The art is amazing!

> To Wei Wuxian: Where is the story from? As it's a work of fiction and has nothing to do with your real life ;)

> Wei Wuxian: Oh hahahha the story is a collaboration of a bunch of ideas! I can't tell u more (sworn to secrecy by my collaborators) but so glad you like it!!!!!!

> To Lan Wangji: Did you do the writing? I love the dialogue.

> Lan Wangji: Wei Wuxian did most of the English. I made it better and did the translation.

> To Lan Wangji: Have you told uncle about this project?

> Lan Wangji: He prefers to speak of my composition achievements.

Lan Xichen puts his phone down and rubs his eyes. The old tension between Lan Qiren and Lan Wangji never goes away. It started in high school with Lan Qiren's disapproval of Wei Wuxian, continued into university with Lan Qiren's disapproval of Wei Wuxian as well as Lan Wangji's decision to attend a local university for musical studies instead of going to Julliard in Lan Xichen's footsteps, and outrage at the news that Lan Wangji asked Wei Wuxian to marry him before they even finished their undergraduate degrees.

The resulting years had been a long-standing cold war, with Lan Xichen trying to mediate in the middle. Even the arrival of Lan Yuan on the scene twenty months previous hadn't softened both sides into anything resembling ease.

If Lan Wangji doesn't want to tell their uncle that he and his husband are collaborating on a semi-biographical graphic novel, Lan Xichen isn't going to muddy the waters.

> To Lan Wangji: It sounds like you're enjoying the project.

> Lan Wangji: Working with Wei Ying on any project is enjoyable. I read that couples with young children should try to engage in a mutual hobby outside of parenting.

> To Lan Wangji: Very wise.

He wonders if he should ask about Meng Yao, types out a message to that effect, then deletes it.

> To Lan Wangji: I should start dinner – see you on the weekend for brunch?

>Lan Wangji: Yes.

Lan Xichen puts his phone down. The days are long in August and the sun still bright, but he's tired and he doesn't know why.

~~

anyway that’s where this whole disaster is going. new fandoms are fun.

#the untamed#my writing#teaser snippet of a new story#i have 14000 words written#trying to get is mostly done before popping up on ao3

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crucial Stats:

Name: Alexander Stirling Scarlet

Age: Late thirties, born April 17th

Height: Five feet nine inches

Weight: One hundred and forty pounds

Hair: Dirty blonde

Eyes: Blue

Ethnicity: Caucasian

Sexuality: Demisexual, grey-aromantic

Religion: Agnostic

Relevant biographical information:

Born in Herne Hill, London, England

Orphaned after his parents, Paul and Claudia Scarlet, were killed in a car accident. Raised by his neglectful high society aunt, Isolde Blackburne.

Graduated from Oxford with a degree in literature and spent years afterward trying unsuccesfully to get his own novels and short stories published. Constantly rejected for “unoriginality.”

Immigrated to America and started his criminal career at the age of twenty-five. Lasted two and a half years as a prominent Gotham rogue before having a glass display case dropped on his head during an altercation with Batgirl (Barbara Gordon).

Spent a year in Arkham Asylum after his hospital stay, where he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Was the victim of medical malpractice at the hands of Dr. Penelope Young, who would repeatedly verbally abuse him during psychiatric sessions and deliberately give him wrong medication doses. Also bullied cruelly by Jonathan Crane, who took pleasure in “breaking him by talking.”

Burned the palms of his hands in a self-harm attempt to the point of permanent nerve damage during his criminal days. Now wears leather gloves to cover them.

Found work at Gotham Academy a year and a half after his release with a clean bill of health and rehabilitation funding. Now works there as a professor of English and drama.

Married Lydia Scarlet nee Limpet after five years of living with her. Now has four children with her—Isabella, Catherine, Amelia, and Jeremy.

Also considers Hayden Ayala and Samuel Robonico as part of the family, as well as Lydia’s extended family on her adopted father’s side.

Good friends with Kira Drake, Elsie Khalii, and Jervis Tetch. Frenemies-leaning-toward-friends with Edward Nygma. Sitcom nemesis of Edgar Heed. Sworn enemy of Jonathan Crane, Batman, and Gotham’s police force.

Still keeps his Men of Letters (his henchpeople from his crime days) as backup if he needs it. Printer’s Devil is the sniper, Typesetter is the medic, Pressman is the muscle and electrician, and Footnote is the gopher and undercover agent.

Does not get along at all well with Headmaster Hammer and will go out of his way to disboey him behind his back. Still very protective of the Academy’s students and trusts the members of Team Detective implicitly—he’s basically the Giles to their Scooby Gang.

Personal trivia:

Can whistle and read music, but not sing.

Always makes a little tutting or “oh!” sound when he’s annoyed, usually accompanied by rolling his eyes. Also makes a lot of “thinking noises” when he speaks and talks with his hands. Almost never uses slang.

Impeccable posture and a cat-like sense of cleanliness.

A very skilled gadgeteer as well as his eidetic memory and speedreading skills. Incredibly well-read and inventive.

Has terrible eyesight, but refuses to wear thick bulky glasses as a professor.

Never loses an opportunity to whip out a pithy literary quote, but gets very frustrated when people misquote things and will instantly correct them.

Has an abysmal sleep schedule and will normally stay awake into the wee hours of the morning. Very restless sleeper who tosses and turns a lot.

Owns three cats–two long-haired tuxedo cats named Ernest and Hercule and one ginger tabby named Lloyd. Also gets along surprisingly well with birds.

Is liable to consume himself with work or fly into a screaming rage over the smallest slight during manic episodes, but usually sits at his desk without moving from it or speaking during depressive ones. Extremely dilligent about taking his medications because he despises losing control.

Has post-traumatic stress reponses to prolonged discussion of Arkham Asylum or anything that reminds him of his time there.

Is the absolute living embodiment of the Superiority/Inferiority Complex and delights in being cheerfully passive-aggressive.

Favorite drink is English breakfast tea or Arabian coffee. Favorite food is roast chicken. Also snacks on peanuts when he’s anxious. Favorite sweet is cherry Danishes.

Has a specfic cafe in the academic district he and Lydia like to order from.

Often underweight as a child because of his aunt’s ill treatment.

Favorite books are Great Expectations, Jane Eyre, and The Time Machine.

Favorite movies are the original Universal Horror canon.

Favorite singer is Nat King Cole.

Disdains a lot of modern rogues and bemoans the needless violence and lack of “class”.

Can be a bit classist and elitist, especially in academic settings.

Walks everywhere if he can help it, only drives if he’s heading out of Gotham altogether.

Scrimped and saved to rent a small cabin for himself, Lydia, and the children whenever they need to get out of the city’s hustle and bustle.

A fairly strict, but still patient and fair teacher as well as parent.

First met Lydia in Blackgate Penitentiary after he was arrested the first time–she kicked his ass in a game of chess.

Once tried to discover Dream of the Endless’s secrets and ended up getting knocked out for a week of nightmares for his trouble. Is very cautious about magic ever since.

Very overly protective of the things and people he loves, tends to be distrustful on their behalf.

Owns basically no casual clothes, always dresses in his Academy attire (the tweed jackets and dress slacks, not the pleather Bookworm suit).

Very self-conscious about his thinning hair and thus will not take off his hat unless it’s for someone he trusts.

Likewise doesn’t like to be touched unless it’s by someone he trusts, will swat your hand away otherwise.

Usually shows verbal affection more often than physical affection. Can be extremely emotionally constipated, especially when he’s just starting to forge a relationship with someone.

Greatest fear is alienating his loved ones or making them afraid of him.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Character

I spotted GILDEROY ALAN LOCKHART in Diagon Alley early today. Have you heard the rumors? Supposedly the HALF-BLOOD is affiliated with NO ONE. Born on APRIL / 1 / 1958, they are TWENTY-FOUR and identify as MALE (HE/HIM) and PANSEXUAL. They work as a BEST-SELLING AUTHOR; it makes sense, given they are FLAMBOYANT & SELFISH but also CREATIVE & RESOURCEFUL. When I think of them, I think of hands stained with ink, pictures edited with a clever charm, and a roguish grin that hasn’t failed him yet.

Faceclaim: Evan Roderick

Biography

Gilderoy Lockhart has been extraordinary since the day of his birth - no! Before even then! Rumor has it that he was performing magic while still in the womb, turning on faucets and levitating his sisters’ toys, among other miraculous feats. His mother tells the outrageously “true” tale that the lights in St. Mungo’s flicked furiously with his first breath, and shone brightly as he opened his eyes for the first time, as if the entire world was welcoming him into it. Surely that must have been a sign of something great and awe-inspiring! (The Healers insisted that it was an accident regarding a different level of the facility and a rather angry half-giant - and that Gilderoy himself had been a rather unimpressive baby, by all standards.)

Mr. Lockhart was a rather ordinary muggle man, with an ordinary job and ordinary features, although his hair was his shining quality - naturally wavy and a lustrous golden color, Gilderoy thanks his father every day for his beautiful locks. It is but one of many traits that make the whole of Gilderoy’s perfect existence - his mother’s magic makes up much of the rest. You see, dear reader, by the age of two Gilderoy was performing charms that even first years couldn’t master, and by five he was more skilled than any other child one could find. He was practically a prodigy - no, he was one. (This is false. Gilderoy was very clever, though, and could convince his mother that he moved things with his mind rather than his hands - she wasn’t exactly a difficult mind to crack.) However, there was a dangerous illusion created in the Lockhart household.

His mother, Eileen, was not shy with her exuberant love for her son. She neglected his three sisters for him, perhaps because two were squibs and the other had yet to show any magical predilections, but nevertheless it was no secret where her affections found priority. In her fanatic support, he became convinced that he was special, one of the few of his kind. That his acceptance to Hogwarts would be a monumental moment in history - the Gilderoy Lockhart, accepted into one of the finest wizarding schools in the world. This thought stemmed not only from his mother’s attitude, but from his family’s lackluster talents. His elder sisters, both squibs, made it seem as though magic was the rarity in the family, while in fact they were. Squibs were greatly uncommon, and two in one family was an even greater oddity. His younger sister was also magical, they would come to find, but she failed to perform anything in front of people - whereas she would make plants grow when no one was looking - so Gilderoy knew in his bones that he was special.

But Gilderoy Lockhart was, in fact, not special at all. Where in the muggle world and within his family, he was considered somewhat of a marvel - by his mother at least - in the wizarding world, he was only one of dozens of children accepted into Hogwarts. His mother failed to mention that all children with magical abilities living in the United Kingdom would be accepted, that whatever talent he thought he might possess meant nothing. Worst of all, not a single classmate cared for his perfect, wonderful hair; not a single professor saw him for the prodigy that he was. It was a shame! It was a tragedy! Not only were they missing out, but he was being deprived of the recognition that he so desperately deserved!

So, he spent his years at Hogwarts striving for such attention, in whatever way he could manage to find it. It did well for his marks, in a surprising turn of events. All that time researching different ways to see his name or face - or both - in some widely published form, resulted in proficiency with different charms and jinxes. (He was nowhere near the top of his class, but he wasn’t quite toward the bottom either. His mother comforted him by saying that the entire system was rife with favoritism.) His grabs for attention ranged from the extreme - carving his name into the quidditch pitch - to the tame - joining the Ravenclaw team just to hear Gilderoy Lockhart! called out by the commentator, which he often became distracted by.

Although attractive and reasonably friendly, his self-centered attitude didn’t gain him many friends. Upon his graduation, there were only one or two people he found himself writing to consistently - the others simply never replied to his letters. They were jealous, of course. He was off finding wonderful adventures! It just happened that those adventures weren’t his. After traveling to “find himself”, he ended up finding something different entirely - a get-rich-quick scheme with impressive results. A drunk patron in a bar in Morocco told him of her valiant run-in with a banshee. What a tale it was! There was mystery! intrigue! and, of course, a victory over the slain creature! The gears in his clever head began turning and as his pen magically dictated her each and every word, he had an idea - what if he simply took this story as his own? He had done it before, with Benjy Fenwick - of course, that was just for an article series in the Prophet, but it gained enough of a following that, should he write a book, he was sure it would be a hit. But, Benjy was distraught by Gilderoy’s betrayal, so he would have to go about this differently…

Memory Charms. He’d researched them quite extensively during his tenure at Hogwarts, but had seldom used them practically. So, he wiped the memory of her own adventure from the witch’s memory and wrote a book as if it was his story. And it was a great success, more than he could have anticipated. Since then, he has published four other novels of exploits that were not his own, yet he claimed them to be. He has been in England for some time promoting his most recent work, Magical Me, an autobiography that could have been written by a fanatic follower, rather than the man himself. Witch Weekly just awarded him with their Most Charming Smile Award, too. Finally, the world was realizing what an extraordinary talent he truly was. Too bad there was a war going on, taking away all those front page spaces that should have been reserved for him. Who cares about Voldemort this, and Dumbledore that? Gilderoy Lockhart is the only person who matters, after all.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Arranged: Chapter 3

Modern AU. Set in 2018. Where Claire and Jamie are arranged to be married.

CH: 1 - 2

AO3

A/N: Sorry it took a while to write this. The past month just has been incredibly weird and strange. But I am happy this is up now, I had a wee writers block on how to make them go forward but I think I found the way. So excited to write what's next. Hope you like this chapter and it's always good to see and hear your comments and suggestions <3

CHAPTER 3: The First Afternoon

It was the morning after the dinner, Claire was on the bus heading to uni to start another day. Usually, she’d spent the 10-minute ride browsing through class notes but today, she found herself staring out the window and watching the city scene go by. Musing with recent events, Claire can’t help but think about Jamie.

Jamie Fraser wasn’t a stranger in her life. On the contrary, she cannot remember her life without him.

Looking back, she remembered their days, growing up in their family dinners. Jamie was two years ahead of her, he was basically in her life even before she knew it and they practically grew up together.

Sure, Jenny and Willie were also there in that scenario as well but with the recent arrangement, she focused on the times she was only with him. Before any of this, she only thought of him as a really close family friend but didn’t think they were really that close. But the more she thought about them, the more wrong she found herself.

She remembered playing in the green fields of their backyard, stealing toys from each other or playing tag; carpooling to and from elementary school for some years, heading straight to either of their house until a parent can come and pick them up; watching the same cartoons, singing the theme song together once it was on; how they would take afternoon naps after watching said show and be woken up exactly at 4PM for some afternoon snacks; how all of them - her, Jenny, Jamie and Willie - would all play house or castle rescue, and how her and Jamie were always deemed the “king and queen” combo or the “prince and damsel” duo, where in the end, he would always save her; In some days, they would even have wedding scenarios played out as part of the story of happily ever after. It was all very innocent and fun, and at the time, no one thought any malice into it. It was just pure childhood fun.

Everything sort of changed when they entered high school. Jamie and Claire went to exclusive boys and girls catholic schools and naturally, they had their own circle and friends and their interactions were limited to their family dinners. Heading off to college, Claire took a pre-med course and Jamie took-up a pre-law course and now, she’s in medical school while he’s busy running the family’s publishing house business. Although they both stayed in Edinburgh, their paths never crossed as often as one would think.

However, despite growing up and somehow, maybe, growing apart, when they do see each other, they would talk and interact as they normally do – the long-time friends they are – and update each other on the status of their lives. All very civil, normal and nothing more.

What’s even more puzzling to Claire, now, is in these times and nobody ever teased them about the “what ifs” of them ending up together. Nobody ever spoke to them in that way, nobody gave an inkling about this merger ever happening. Nobody had a rumored crush on anyone. Nobody gave them any thought and no one gave her any indication to. As far as she knew, Jamie Fraser was and will always be just a long-time family friend in her life.

The shock of the engagement was wearing off but Claire was determined to get to the bottom of this. Jamie was right – their parents aren’t impulsive enough to set this up lightly. There is a deep, real reason for it and she will know it and put a stop to it.

-

“Darling, there you are!” Frank called as she stepped out of the car, breaking her thoughts of Jamie.

Frank – her very new and current suitor. They’ve been seeing each other for over a month and Claire was totally smitten with the professor right from the moment they met at the university library when he helped her carry her loads of medical books from the shelf to the table.

He make a joke – she can’t remember it anymore – but it made her laugh in what was a stressful exam week and she was charmed by his aristocratic elegance and wit. They got to talking after that and she found out he was a history professor and almost a decade older than her (though she thought he didn’t look like it).

She hadn’t told her parents about him because of what they might think of her dating a much older man and how it can affect their position in the university. She was a student (she can argue that she’s in medical school and not some undergraduate bimbo) and he was a teacher – that scenario doesn’t look good in any way, shape or form. Also, she wasn’t entirely certain of him yet - so she’s taking her time to get to know him a little bit more before she allows him more into her life.

As they met in the middle of the courtyard, Frank noticed her somber aura. “What is it, Claire?” he asked, concerned.

“Oh, it’s nothing. Just got up in the wrong side of the bed” she lied. He took it at face value and thought nothing more. Clearly, he doesn’t know her yet as he hadn’t caught up with the jig.

“Okay!” He said, really not noticing it. “I gotta run to class. I’ll see you in the afternoon?”

“Yes – No! I forgot I have a group meeting later and don’t know how long would that be. Uhm…maybe just call me later and see where I’m at?” She said. Frank just nodded and went on his way.

-

It was technically a groupmeeting – they were two people, that counts. She was going to see Jamie in a nearby coffee shop and start this ridiculous quest. The day went by with Claire mostly working on autopilot student mode. Her mind ran scenarios on where they should start to investigate, people they can ask favor for to look into their family company. They should also fix their schedules and think about how this will affect their studies. This investigation was going to take over their lives and both seem to be in agreement with it – Claire, simply, wants it to be over.

He was already seated when she arrived, her favorite beverage, hot and waiting, on the table. “Sorry, I’m late. The bus was late and there was so many people waiting in line…” Claire explained herself. “It’s no mind, Claire.” Jamie stopped her before she went on a long narrative. She just smiled and took her seat across from him.

“Oolong Tea” Jamie pointed to the cup. “I hope ye dinna mind me orderin’ for ye. I canna choose which pastry ye’d like today though, so I’ll let ye choose that one.”

“It’s fine. That’s what I was going to drink anyway and I’ll order the bread later.” Claire thought about how Jamie knew her drink but with their long history, she thought she shouldn’t be shocked about it. After all, she knew his drink even though the lid of the coffee cup hid its contents – it was black, three sugars.

“Where do we begin?” she asked, hoping it’ll shift her thought from their apparent familiarity.

“Well, what did yer parents say to ye again?”

“That this was a business merger of some sort, which honestly, doesn’t make sense. Your business seems to be fine, ours is as well. Do you have any idea about the financial status of your company?”

Jamie shrugged. He already knows falling numbersis not the problem but this was the ruse. As much joy it was to spend with her, it equally pained him for it to be this way. “I guess we can start there?” He suggested. “Let me call Rupert and Angus Mackenzie from Finance, I’m sure they can discreetly hand me the finances since…2010? I’ll just go that far back just in case.” Real reason was to accumulate as much paperwork to get lost themselves in.

Since the Frasers and Beauchamps are both stakeholders in each other’s company, they both had access to the numbers for both companies. Acquiring the data was not that hard.

“Hi, Rupert! I’m okay, just settling back” Jamie said as he called Rupert. “Rupert, I was wondering if you could send me the year-end numbers of our company and the Beauchamps dating back in 2010? Yes, - No, I would just like to study the trends…”

“No need to explain. I got you, Jamie! I’ll send it in an hour.” Rupert answered back with a knowing laugh, interrupting Jamie’s ramble of an explanation. His parents must’ve set this up too. Jamie sighed hopelessly, thanked Rupert and ended the call.

“Files will be sent in an hour” Jamie said.

“I guess we got time to kill. Would you mind if I did a bit of studying? We’re already here and we gotta wait.” Claire asked.

“No, no, go ahead. I was just going to ask the same thing.” He replied with a smile as he started pulling out his stuff from his bag.

They were occupying in a four-seater table, the space just enough for each of them to claim a side. Claire put out her laptop, two medical books, a notebook and lots of pencils and ballpens. Jamie, also, pulled out his laptop, three novels, a notebook and lots of highlighters. Both silently went on their respective study sessions.

A little over a half hour in, Jamie disrupted Claire’s thought with a question. “Claire, do you need a refill?”

She looked up, a little disoriented. “Hm, what? Oh, yes, please, thank you.”

Jamie took her cup and went to bar to fill her tea with a fresh pour of hot water. He refilled his coffee too. As he set down her cup, Claire inadvertently let out a question. “How did you know I refill?” She was curious as to how much Jamie really knew her. She saw him turn a little shy in her question as he placed a hand on the back of his neck.

“Well, ye’ve been drinking Oolong tea since we were wee bairns and ye always made sure that the tea bag is always well-used and that meant two, maybe three, uses until it lost its flavor for ye. Also, you’re doing that eye-scrunch thing when ye’re thinking so hard of a thing ye canna or tryna figure out. Thought it a good time to distract ye.”

“Well, it was. Thank you” Claire said monotonously as she took a sip of her tea. “I see you’re still coloring your books with highlighters.” She said, pointing at his many colors of markers on his table.

“And I see ye’re still placing wee snacks on each paragraph in yer book.” Jamie retorted back and they shared a small laugh.

“It’s been a while since we studied together but it seems like some things never change”

“Aye, some things never do, Sassenach” Jamie said tenderly, looking straight into Claire’s eyes.

“Hey, you haven’t called me that in forever!” Claire exclaimed excitedly. “What does that mean again?”

“Och, nothing. It just means Englishman, or in yer case, Englishwoman. An outlander, not from Scotland”

“Right, right! That’s the only name you’d call me growing up, I almost forgot my own!”

“Really?” Jamie never knew the name meant possibly more than Claire let on and he was curious to know the story behind it. However, a ding on Jamie’s computer alerted them back to the task at hand.

“Ach, the email is here” Jamie informed Claire and she quickly got up, went over to his side, pulled out a chair and sat beside him. She peered so close at his computer their cheeks were almost side to side.

“Open it, open it!” Claire said, waving a hand to Jamie to hurry up.

“Patience!” he chuckled as the file filled the screen.

Both simultaneously groaned when the file they got was filled with so much number, just pure numbers, neither of them can make it out. Rupert must’ve made it so complicated, they’ll never figure anything out.

“Seriously, Rupert!” Claire rolled her eyes, annoyed.

“I’ll call him –“

“No. He might get suspicious if we ask so much and so frequently. We, erm, we…can figure this out”

“How about we call it for the day? We got the file, we can look at it tomorrow instead.” Jamie said, looking to prolong the evidence. If they start on this now, Claire will never stop for the rest of the afternoon and probably evening. “I got an exam I have to study for anyway. Unless, you want to have a go at it?”

Claire shook her head. She’s got to study too. “No, you’re right. I have to study too.” She sighed. “We have to talk about a schedule where this research is not going to interfere with our studies – which is our top priority”

Jamie just nodded. “How about we meet here every after class and maybe spend 2-3 hours looking at this, then we go back to our studies? Sounds like enough time to balance our day?”

They reached an agreement and let the investigation stop for the day. Claire reached for her stuff to pack but when she noticed Jamie didn’t move and just continued to go back to highlighting his pages. “Aren’t you going home or somewhere else to study?”

“Och, I’m already here and the ambiance is good, thought I’d stay until the evening.” Jamie replied with a sheepish smile. Claire looked around and the atmosphere was good. The smell of the coffee was inviting, the people were quiet, and a change of scene was probably what she needed to focus. It wasn’t bad either that she’s with Jamie, they were friends after all. With that, she put her stuff back on the table and decided to stay as well. Jamie stayed silent and they went on their own business but she saw the small tug in his lips and he smiled.

-

A loud ringing of the cellphone brought them out of their space. It was Claire’s phone and Claire’s mother calling.

“Hello, yeah – I’m sorry. I’m on my way home. No, just got lost in studying” Claire rapidly explained as Jamie could hear her mother’s rapid line of questioning. “Yep, I’ll be there in 15 minutes. Love you, bye”

“Ye’ll be there in 5” Jamie said. “I’ll take ye home”. It was already 8:00PM and they were going to miss dinner.

“What? No, Jamie. It’s fine. The bus by this time are probably not that full.” They were quickly packing their stuff while, also, quickly negotiating their travel plans.

“I have a car and we live in the same neighborhood. Ye canna argue with that logic, Claire.”

Claire grumbled but relented. It was certainly easier and convenient and again, Jamie was no stranger. On some unsurprisingly absurd level, she trusts him completely. She reasons it’s probably from the years they’ve known each other. Nonetheless, if Jamie acts inappropriately, she’ll just tell him to their mothers.

The drive home was quick and Jamie, being the true gentleman he was, insisted that he open Claire’s passenger door and walk her right in front of her doorstep. She was about to protest but his actions were quicker and for the fourth time that day, she let him…erm…look out for her.

“Thank you for a lovely afternoon. For the tea, the records, the study time, and the ride home” she said as she turned around to bade him goodbye. They were standing in a respectable distance from one another, just as friends do. “Would you like to stay for dinner? It’s the least I can offer for the tea.”

“Ah, no. My family is waiting on me too. I’ll have my hide if mam doesna see me on the table”

“Well, then, goodnight, Jamie.”

“Goodnight, Sassenach. I’ll see you tomorrow?”

“I’ll see you tomorrow.”

#outlander#outlander fanfic#outlander fanfiction#fanfic#fanfiction#arranged#arranged au#jamie fraser#Claire fraser#Claire Beauchamp#modern AU#how do you make those gorgeous moodboards#ahihihihi#tb writes

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

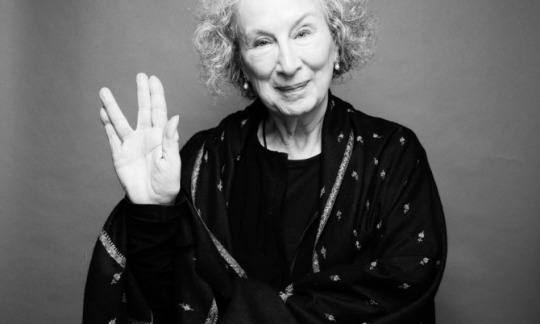

The Handmaid’s Tale: How Will Margaret Atwood’s Book Sequel Affect the TV Show?

https://ift.tt/2MqdrsZ

Margaret Atwood’s Testaments, out this September, is a sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale. What is its relationship to the TV series?

facebook

twitter

tumblr

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

As Game Of Thrones proved, when a TV adaptation overtakes its source material, problems can follow. Invention and expansion is required, but, even with the blessing of the original creator, on-screen continuation of a story is often treated by fans as unwelcome and non-canonical.

When Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale arrived in 2017, its first season covered the expanse of material from the very start to the very end of Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel (epilogue aside, it closed on the same final image). For seasons two and three, the show expanded the dystopian world of Gilead, a fundamentalist patriarchal regime that, among other delights, forces fertile women into sexual servitude as 'Handmaids' to the ruling classes, and kept the story going beyond the reach of the book.

Now, with The Handmaid’s Tale renewed for a fourth season, and a sequel to the original novel arriving mid-way between seasons three and four, where does everything stand?

What do we know about Testaments?

Publication date: Sept. 10, 2019

Published by: Penguin

Announced in November 2018, Testaments is Margaret Atwood's sequel to her 1985 modern classic The Handmaid’s Tale. It joins the story 15 years after the events of that novel. (A framing narrative for the original in the form of a fictional academic paper presented on the historical period of Gilead extends 200 years after those events, so technically, the sequel is filling in a gap instead of branching entirely out anew.)

Testaments' cover art (see above) was designed by artist Noma Bar, whose simplified designs contain hidden images, such as the ponytailed girl forming the collar of the cover star Handmaid. The back cover reverses the two images, with the Handmaid concealed among the ponytailed girl's clothing.

read more - The Handmaid's Tale: The Baby Nichole Crisis's Real-World Parallel

The new novel will have three different female narrators, Atwood has confirmed, though their identities remain under wraps. The sequel was inspired by everything readers have ever asked the author “about Gilead and its inner workings,” and by “the world we’ve been living in,” according to the Penguin press announcement. It will be unconnected to events in seasons two and three of Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale (which makes sense as they take place in the time directly after the end of the original, and Testaments is set a decade and a half later on).

When asked by the LA Times why she was writing a sequel, Atwood explained that she’d been asked questions about Gilead by readers for 35 years. “It’s time to address some of the requests.”

The Trump administration too, was part of her explanation. Atwood described herself “like all Canadians” watching US politics and thinking “What kind of shenanigans will they be up to next? What’s gonna happen next? I’ve never seen anything like it, and neither has anybody else. On one hand, it’s just riveting, and on the other hand, it’s quite appalling.” True and true.

Testaments isn’t Margaret Atwood’s first addition to her original novel

In 2017, an “enhanced edition” of The Handmaid’s Tale audiobook - as read by Claire Danes in 2012 - was released. This version by Audible not only added snippets of music in between chapters (to represent the cassette compilation tapes over which Offred recorded her story in the original novel), but also extended the epilogue.

read more: The Handmaid's Tale Season 3 Depicts a Seismic Shift in Gilead

Originally, The Handmaid’s Tale novel ends with the ‘transcription’ of a fictional conference paper presented by an academic researcher in Gileadean studies, 200 years after the events of the story. It’s a sly, satirical piece of writing that concluded with the line “Are there any questions?” In the 2017 edition, questions are asked. Audience members – one voiced by Margaret Atwood – ask speaker Professor James Darcy Pieixoto a series of points about his paper and the workings of Gilead. During the Q&A, there’s even mention of the historical discovery of Aunt Lydia’s logbook from the era, which turned out to be a hoax. The session ends with a tease for the sequel, as the Professor tells his audience “I hope to be able to present the results of our further Gileadian investigations to you at some future date.”

On September the 10th this year, that’s exactly what's going to happen.

What is Atwood’s relationship to The Handmaid’s Tale TV show?

Atwood is a Consulting Producer on Hulu’s TV adaptation of her novel, which doesn’t mean, as she told Toronto Life back in April 2017, that she has the final say in story or otherwise, but that she’s part of the conversation: “It means that the only person who knows what the characters had for breakfast is me. I’m the historical consultant.”

Showrunner Bruce Miller told The Hollywood Reporter in January 2018 that Atwood “plays a huge role” in the series as “the mother of us all.”

“She was in the writers' room very early in the season,” said Miller about the second season. “We've been talking throughout, and she's been reading everything. She's very involved. She's our guiding star, and always has been.”

The team’s goal, he explained, is to “make sure the "Atwoodness" of the show stays front and centre. Even though we're going beyond the story that's covered in the book, in some ways, we're still very much in the world of Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale.”

In the season one premiere, Atwood had a dialogue-free cameo as an authoritarian Aunt who strikes Elisabeth Moss’ June during her training at the RED centre, where Handmaids are prepared for their postings:

%u201CI even did a cameo%u2014I got to whack Elisabeth Moss over the head%u201D: @MargaretAtwood on The Handmaid%u2019s Tale https://t.co/l9tmnT3Oke pic.twitter.com/YvMuugvNRv

— Toronto Life (@torontolife) April 26, 2017

Speaking to The Independent in June 2019, Miller confirmed that he is is regular contact with Atwood. “She reads all the scripts. She sees episodes, and so she feels the same way, I think – that it’s a good extrapolation of her world.”

So the expanded Gilead of seasons two and three, which travelled to the Colonies and the Econovillage, locations only mentioned in passing in the original novel, will not influence Testaments.

Seasons two, three and four of the TV show continue to draw from the book

Though The Handmaid’s Tale TV show outran the novel by the end of season one in terms of timeline, elements from the book are still being used up by the television series. In season two, the first “Prayvaganza” was staged, a Gilead ceremony from the novel in which girls as young as fourteen are married off to men in a mass ceremony.

In season three, viewers first witnessed the act of “particicution” by hanging as described in the novel, in which multiple Handmaids pull on ropes joined to one set of gallows, as a form of “salvaging.” Also in season three, June discovers and records a message on a compilation cassette in the basement of her latest posting, as a reference to the tapes on which Offred’s original testimony was discovered in the novel.

Speaking to The Independent in June 2019, showrunner Bruce Miller described how June’s season three inner monologue line about her mother always wanting a "women's culture" and Gilead has created one, but not the one she envisaged, was taken straight from the book. “We spent kind of three years teasing that quote apart,” said Miller. “We have quotes from the book up all over the place."

So even though the timeline has strictly run out, we can expect details from the novel to emerge for exploration in future seasons of the TV show, and presumably the same will apply for Testaments.

Testaments will make the TV show harder to write

Speaking to The Independent about the relationship between the original novel and the TV adaptation, showrunner Bruce Miller brought up Testaments. “But now Margaret’s writing a sequel,” he said, agreeing that would make it “interesting”.

“The degree of difficulty was 10 and now it becomes 10 plus,” said Miller. Navigating the expanded world of Gilead he and his team have created while remaining truthful to the vision Atwood lays out in Testaments will be some balancing act.

How many seasons will the TV show go on for?

Season four of The Handmaid’s Tale is expected to arrive in 2020. According to a very early plan by showrunner Bruce Miller, there would then be a further six seasons still to go after that. Miller told The Hollywood Reporter in 2017 that he had originally “roughed it out to around 10 seasons”, but has since confirmed to Mashable that there is no exact target in terms of the number of seasons, more a narrative point he wants to reach.

“The ideal for the show's longevity is that when it's done there's something kind of nice and perfect that you can put on the shelf next to the book as a companion piece, said Miller. “There is no number, and considering that seasons can get longer and shorter has made that even more meaningless.”

Miller told Mashable he wants to take the story all the way to Gilead’s own version of the Nuremberg Trials after the fall of the regime, when Serena and Commander Waterford are forced to answer for their crimes. “We can go on for a very long time,” he promised.

Keep up with all our The Handmaid's Tale season 3 news and reviews right here.

Read and download the Den of Geek SDCC 2019 Special Edition Magazine right here!

facebook

twitter

tumblr

Feature

Books

Louisa Mellor

Jul 31, 2019

The Handmaid's Tale

hulu

Margaret Atwood

from Books https://ift.tt/310hK26

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/yoga-meditation-and-psychedelics-would-you-take-drugs-during-your-practice/

Yoga, Meditation and Psychedelics: Would you Take Drugs During Your Practice?

Top yoga and meditation teachers Sally Kempton and Ram Dass share their personal experiences with psychedelics as we explore the latest trends in research and recreational use.

ANDREW BANNECKER

When a friend invited Maya Griffin* to a “journey weekend”—two or three days spent taking psychedelics in hopes of experiencing profound insights or a spiritual awakening—she found herself considering it. “Drugs were never on my radar,” says Griffin, 39, of New York City. “At an early age, I got warnings from my parents that drugs may have played a role in bringing on a family member’s mental illness. Beyond trying pot a couple times in college, I didn’t touch them.” But then Griffin met Julia Miller* in a yoga class, and after about a year of friendship, Miller began sharing tales from her annual psychedelic weekends. She’d travel with friends to rental houses in various parts of the United States where a “medicine man” from California would join them and administer mushrooms, LSD, and other psychedelics. Miller would tell Griffin about experiences on these “medicines” that had helped her feel connected to the divine. She’d talk about being in meditative-like bliss states and feeling pure love.

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

This time, Miller was hosting a three-day journey weekend with several psychedelics—such as DMT (dimethyltryptamine, a compound found in plants that’s extracted and then smoked to produce a powerful experience that’s over in minutes), LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide, or “acid,” which is chemically synthesized from a fungus), and Ayahuasca (a brew that blends whole plants containing DMT with those that have enzyme inhibitors that prolong the DMT experience). Miller described it as a “choose your own adventure” weekend, where Griffin could opt in or out of various drugs as she pleased. Griffin eventually decided to go for it. Miller recommended she first do a “mini journey”—just one day and one drug—to get a sense of what it would be like and to see if a longer trip was really something she wanted to do. So, a couple of months before the official journey, Griffin took a mini journey with magic mushrooms.

See also This is the Reason I Take the Subway 45 Minutes Uptown to Work Out—Even Though There’s a Gym On My Block

“It felt really intentional. We honored the spirits of the four directions beforehand, a tradition among indigenous cultures, and asked the ancestors to keep us safe,” she says. “I spent a lot of time feeling heavy, lying on the couch at first. Then, everything around me looked more vibrant and colorful. I was laughing hysterically with a friend. Time was warped. At the end, I got what my friends would call a ‘download,’ or the kind of insight you might get during meditation. It felt spiritual in a way. I wasn’t in a relationship at the time and I found myself having this sense that I needed to carve out space for a partner in my life. It was sweet and lovely.”

Griffin, who’s practiced yoga for more than 20 years and who says she wanted to try psychedelics in order to “pull back the ‘veil of perception,’” is among a new class of yoga practitioners who are giving drugs a try for spiritual reasons. They’re embarking on journey weekends, doing psychedelics in meditation circles, and taking the substances during art and music festivals to feel connected to a larger community and purpose. But a renewed interest in these explorations, and the mystical experiences they produce, isn’t confined to recreational settings. Psychedelics, primarily psilocybin, a psychoactive compound in magic mushrooms, are being studied by scientists, psychiatrists, and psychologists again after a decades-long hiatus following the experimental 1960s—a time when horror stories of recreational use gone wrong contributed to bans on the drugs and harsh punishments for anyone caught with them. This led to the shutdown of all studies into potential therapeutic uses, until recently. (The drugs are still illegal outside of clinical trials.)

Another Trip with Psychedelics

The freeze on psychedelics research was lifted in the early 1990s with Food and Drug Administration approval for a small pilot study on DMT, but it took another decade before studies of psychedelics began to pick up. Researchers are taking another look at drugs that alter consciousness, both to explore their potential role as a novel treatment for a variety of psychiatric or behavioral disorders and to study the effects that drug-induced mystical experiences may have on a healthy person’s life—and brain. “When I entered medical school in 1975, the topic of psychedelics was off the board. It was kind of a taboo area,” says Charles Grob, MD, a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, who conducted a 2011 pilot study on the use of psilocybin to treat anxiety in patients with terminal cancer. Now researchers such as Grob are following up on the treatment models developed in the ’50s and ’60s, especially for patients who don’t respond well to conventional therapies.

See also 6 Yoga Retreats to Help You Deal With Addiction

This opening of the vault—research has also picked up again in countries such as England, Spain, and Switzerland—has one big difference from studies done decades ago: Researchers use stringent controls and methods that have since become the norm (the older studies relied mostly on anecdotal accounts and observations that occurred under varying conditions). These days, scientists are also utilizing modern neuroimaging machines to get a glimpse into what happens in the brain. The results are preliminary but seem promising and suggest that just one or two doses of a psychedelic may be helpful in treating addictions (such as to cigarettes or alcohol), treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety in patients with terminal cancer. “It’s not about the drug per se, it’s about the meaningful experience that one dose can generate,” says Anthony Bossis, PhD, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine who conducted a 2016 study on the use of psilocybin for patients with cancer who were struggling with anxiety, depression, and existential distress (fear of ceasing to exist).

Spiritual experiences in particular are showing up in research summaries. The term “psychedelic” was coined by a British-Canadian psychiatrist during the 1950s and is a mashup of two ancient Greek words that together mean “mind revealing.” Psychedelics are also known as hallucinogens, although they don’t always produce hallucinations, and as entheogens, or substances that generate the divine. In the pilot study looking at the effects of DMT on healthy volunteers, University of New Mexico School of Medicine researchers summarized the typical participant experience as “more vivid and compelling than dreams or waking awareness.” In a study published in 2006 in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine gave a relatively high dose (30 mg) of psilocybin to healthy volunteers who’d never previously taken a hallucinogen and found that it could reliably evoke a mystical-type experience with substantial personal meaning for participants. About 70 percent of participants rated the psilocybin session as among the top five most spiritually significant experiences of their lives. In addition, the participants reported positive changes in mood and attitude about life and self—which persisted at a 14-month follow-up. Interestingly, core factors researchers used in determining whether a study participant had a mystical-type experience, also known as a peak experience or a spiritual epiphany, was their report of a sense of “unity” and “transcendence of time and space.” (See “What’s a Mystical Experience?” section below for the full list of how experts define one.)

In psilocybin studies for cancer distress, the patients who reported having a mystical experience while on the drug also scored higher in their reports of post-session benefits. “For people who are potentially dying of cancer, the ability to have a mystical experience where they describe experiencing self-transcendence and no longer solely identifying with their bodies is a profound gift,” says Bossis, also a clinical psychologist with a speciality in palliative care and a long interest in comparative religions. He describes his research as the study of “the scientific and the sacred.” In 2016 he published his findings on psilocybin for cancer patients in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, showing that a single psilocybin session led to improvement in anxiety and depression, a decrease in cancer-related demoralization and hopelessness, improved spiritual well-being, and increased quality of life—both immediately afterward and at a six-and-a-half-month follow-up. A study from Johns Hopkins produced similar results the same year. “The drug is out of your system in a matter of hours, but the memories and changes from the experience are often long-lasting,” Bossis says.

Learn if psychedelics complement a yoga practice or promote healing.

ANDREW BANNECKER

The Science of Spirituality

In addition to studying psilocybin-assisted therapy for cancer patients, Bossis is director of the NYU Psilocybin Religious Leaders Project (a sister project at Johns Hopkins is also in progress), which is recruiting religious leaders from different lineages—Christian clergy, Jewish rabbis, Zen Buddhist roshis, Hindu priests, and Muslim imams—and giving them high-dose psilocybin in order to study their accounts of the sessions and any effects the experience has on their spiritual practices. “They’re helping us describe the nature of the experience given their unique training and vernacular,” says Bossis, who adds that it’s too early to share results. The religious-leaders study is a new-wave version of the famous Good Friday Experiment at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel, conducted in 1962 by psychiatrist and minister Walter Pahnke. Pahnke was working on a PhD in religion and society at Harvard University and his experiment was overseen by members of the Department of Psychology, including psychologist Timothy Leary, who’d later become a notorious figure in the counterculture movement, and psychologist Richard Alpert, who’d later return from India as Ram Dass and introduce a generation to bhakti yoga and meditation. Pahnke wanted to explore whether using psychedelics in a religious setting could invoke a profound mystical experience, so at a Good Friday service his team gave 20 divinity students a capsule of either psilocybin or an active placebo, niacin. At least 8 of the 10 students who took the mushrooms reported a powerful mystical experience, compared to 1 of 10 in the control group. While the study was later criticized for failing to report an adverse event—a tranquilizer was administered to a distressed participant who left the chapel and refused to return—it was the first double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment with psychedelics. It also helped establish the terms “set” and “setting,” commonly used by researchers and recreational users alike. Set is the intention you bring to a psychedelic experience, and setting is the environment in which you take it.

“Set and setting are really critical in determining a positive outcome,” UCLA’s Grob says. “Optimizing set prepares an individual and helps them fully understand the range of effects they might have with a substance. It asks patients what their intention is and what they hope to get out of their experience. Setting is maintaining a safe and secure environment and having someone there who will adequately and responsibly monitor you.”

Bossis says most patients in the cancer studies set intentions for the session related to a better death or end of life—a sense of integrity, dignity, and resolution. Bossis encourages them to accept and directly face whatever is unfolding on psilocybin, even if it’s dark imagery or feelings of death, as is often the case for these study participants. “As counterintuitive as it sounds, I tell them to move into thoughts or experiences of dying—to go ahead. They won’t die physically, of course; it’s an experience of ego death and transcendence,” he says. “By moving into it, you’re directly learning from it and it typically changes to an insightful outcome. Avoiding it can only fuel it and makes it worse.”

In the research studies, the setting is a room in a medical center that’s made to look more like a living room. Participants lie on a couch, wear an eye mask and headphones (listening to mostly classical and instrumental music), and receive encouragement from their therapists to, for example, “go inward and accept the rise and fall of the experience.” Therapists are mostly quiet. They are there to monitor patients and assist them if they experience anything difficult or frightening, or simply want to talk.

“Even in clinical situations, the psychedelic really runs itself,” says Ram Dass, who is now 87 and lives in Maui. “I’m happy to see that this has been opened up and these researchers are doing their work from a legal place.”

The Shadow Side and How to Shift It

While all of this may sound enticing, psychedelic experiences may not be so reliably enlightening or helpful (or legal) when done recreationally, especially at a young age. Documentary filmmaker and rock musician Ben Stewart, who hosts the series Psychedelica on Gaia.com, describes his experiences using psychedelics, including mushrooms and LSD, as a teen as “pushing the boundaries in a juvenile way.” He says, “I wasn’t in a sacred place or even a place where I was respecting the power of the plant. I was just doing it whenever, and I had extremely terrifying experiences.” Years later in his films and research projects he started hearing about set and setting. “They’d say to bring an intention or ask a question and keep revisiting it throughout the journey. I was always given something more beautiful even if it took me to a dark place.”

Brigitte Mars, a professor of herbal medicine at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, teaches a “sacred psychoactives” class that covers the ceremonial use of psychedelics in ancient Greece, in Native American traditions, and as part of the shamanic path. “In a lot of indigenous cultures, young people had rites of passage in which they might be taken aside by a shaman and given a psychedelic plant or be told to go spend the night on a mountaintop. When they returned to the tribe, they’d be given more privileges since they’d gone through an initiation,” she says. Mars says LSD and mushrooms combined with prayer and intention helped put her on a path of healthy eating and yoga at a young age, and she strives to educate students about using psychedelics in a more responsible way, should they opt to partake in them. “This is definitely not supposed to be about going to a concert and getting as far out as possible. It can be an opportunity for growth and rebirth and to recalibrate your life. It’s a special occasion,” she says, adding, “psychedelics aren’t for everyone, and they aren’t a substitute for working on yourself.”

See also 4 Energy-Boosting Mushrooms (And How to Cook Them)

Tara Brach, PhD, a psychologist and the founder of Insight Meditation Community of Washington, DC, says she sees great healing potential for psychedelics, especially when paired with meditation and in clinical settings, but she warns about the risk of spiritual bypassing—using spiritual practices as a way to avoid dealing with difficult psychological issues that need attention and healing: “Mystical experience can be seductive. For some it creates the sense that this is the ‘fast track,’ and now that they’ve experienced mystical states, attention to communication, deep self-inquiry, or therapy and other forms of somatic healing are not necessary to grow.” She also says that recreational users don’t always give the attention to setting that’s needed to feel safe and uplifted. “Environments filled with noise and light pollution, distractions, and potentially insensitive and disturbing human interactions will not serve our well-being,” she says.

As these drugs edge their way back into contemporary pop culture, researchers warn about the medical and psychological dangers of recreational use, especially when it involves the mixing of two or more substances, including alcohol. “We had a wild degree of misuse and abuse in the ’60s, particularly among young people who were not adequately prepared and would take them under all sorts of adverse conditions,” Grob says. “These are very serious medicines that should only be taken for the most serious of purposes. I also think we need to learn from the anthropologic record about how to utilize these compounds in a safe manner. It wasn’t for entertainment, recreation, or sensation. It was to further strengthen an individual’s identity as part of his culture and society, and it facilitated greater social cohesion.”

Learn about the pyschedelic roots of yoga.

ANDREW BANNECKER

Yoga’s Psychedelic Roots

Anthropologists have discovered mushroom iconography in churches throughout the world. And some scholars make the case that psychoactive plants may have played a role in the early days of yoga tradition. The Rig Veda and the Upanishads (sacred Indian texts) describe a drink called soma (extract) or amrita (nectar of immortality) that led to spiritual visions. “It’s documented that yogis were essentially utilizing some brew, some concoction, to elicit states of transcendental awareness,” say Tias Little, a yoga teacher and founder of Prajna Yoga school in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He also points to Yoga Sutra 4.1, in which Patanjali mentions that paranormal attainments can be obtained through herbs and mantra.

“Psychotropic substances are powerful tools, and like all tools, they can cut both ways—helping or harming,” says Ganga White, author of Yoga Beyond Belief and MultiDimensional Yoga and founder of White Lotus Foundation in Santa Barbara, California. “If you look at anything you can see positive and negative uses. A medicine can be a poison and a poison can be a medicine—there’s a saying like this in the Bhagavad Gita.”

White’s first experience with psychedelics was at age 20. It was 1967 and he took LSD. “I was an engineering student servicing TVs and working on electronics. The next day I became a yogi,” he says. “I saw the life force in plants and the magnitude of beauty in nature. It set me on a spiritual path.” That year he started going to talks by a professor of comparative religion who told him that a teacher from India in the Sivananda lineage had come to the United States. White went to study with him, and he would later make trips to India to learn from other teachers. As his yoga practice deepened, White stopped using psychedelics. His first yoga teachers were adamantly anti-drug. “I was told that they would destroy your chakras and your astral body. I stopped everything, even coffee and tea,” he says. But within a decade, White began shifting his view on psychedelics again. He says he started to notice “duplicity, hypocrisy, and spiritual materialism” in the yoga world. And he no longer felt that psychedelic experiences were “analog to true experiences.” He started combining meditation and psychedelics. “I think an occasional mystic journey is a tune-up,” he says. “It’s like going to see a great teacher once in a while who always has new lessons.”

See also Chakra Tune-Up: Intro to the Muladhara

Meditation teacher Sally Kempton, author of Meditation for the Love of It, shares the sentiment. She says it was her use of psychedelics during the ’60s that served as a catalyst for her meditation practice and studies in the tantric tradition. “Everyone from my generation who had an awakening pretty much had it on a psychedelic. We didn’t have yoga studios yet,” she says. “I had my first awakening on acid. It was wildly dramatic because I was really innocent and had hardly done any spiritual reading. Having that experience of ‘everything is love’ was totally revelatory. When I began meditating, it was essentially for the purpose of getting my mind to become clear enough so that I could find that place that I knew was the truth, which I knew was love.” Kempton says she’s done LSD and Ayahuasca within the past decade for “psychological journeying,” which she describes as “looking into issues I find uncomfortable or that I’m trying to break through and understand.”

Little tried mushrooms and LSD at around age 20 and says he didn’t have any mystical experiences, yet he feels that they contributed to his openness in exploring meditation, literature, poetry, and music. “I was experimenting as a young person and there were a number of forces shifting my own sense of self-identity and self-worth. I landed on meditation as a way to sustain a kind of open awareness,” he says, noting that psychedelics are no longer part of his sadhana (spiritual path).

Going Beyond the Veil

After her first psychedelic experience on psilocybin, Griffin decided to join her friends for a journey weekend. On offer Friday night were “Rumi Blast” (a derivative of DMT) and “Sassafras,” which is similar to MDMA (Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, known colloquially as ecstasy or Molly). Saturday was LSD. Sunday was Ayahuasca. “Once I was there, I felt really open to the experience. It felt really safe and intentional—almost like the start of a yoga retreat,” she says. It began by smudging with sage and palo santo. After the ceremonial opening, Griffin inhaled the Rumi Blast. “I was lying down and couldn’t move my body but felt like a vibration was buzzing through me,” she says. After about five minutes—the length of a typical peak on DMT—she sat up abruptly. “I took a massive deep breath and it felt like remembrance of my first breath. It was so visceral.” Next up was Sassafras: “It ushered in love. We played music and danced and saw each other as beautiful souls.” Griffin originally planned to end the journey here, but after having such a connected experience the previously night, she decided to try LSD. “It was a hyper-color world. Plants and tables were moving. At one point I started sobbing and I felt like I was crying for the world. Two minutes felt like two hours,” she says. Exhausted and mentally tapped by Sunday, she opted out of the Ayahuasca tea. Reflecting on it now, she says, “The experiences will never leave me. Now when

I look at a tree, it isn’t undulating or dancing like when I was on LSD, but I ask myself, ‘What am I not seeing that’s still there?’”

See also This 6-Minute Sound Bath Is About to Change Your Day for the Better

The Chemical Structure of Psychedelics

It was actually the psychedelic research of the 1950s that contributed to our understanding of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which regulates mood, happiness, social behavior, and more. Most of the classic psychedelics are serotonin agonists, meaning they activate serotonin receptors. (What’s actually happening during this activation is mostly unknown.)

Classic psychedelics are broken into two groups of organic compounds called alkaloids. One group is the tryptamines, which have a similar chemical structure to serotonin. The other group, the phenethylamines, are more chemically similar to dopamine, which regulates attention, learning, and emotional responses. Phenethylamines have effects on both dopamine and serotonin neurotransmitter systems. DMT (found in plants but also in trace amounts in animals), psilocybin, and LSD are tryptamines. Mescaline (derived from cacti, including peyote and San Pedro) is a phenethylamine. MDMA, originally developed by a pharmaceutical company, is also a phenethylamine, but scientists don’t classify it as a classic psychedelic because of its stimulant effects and “empathogenic” qualities that help a user bond with others. The classics, whether they come straight from nature (plant teas, whole mushrooms) or are semi-synthetic forms created in a lab (LSD tabs, psilocybin capsules), are catalysts for more inwardly focused personal experiences.

See also Try This Durga-Inspired Guided Meditation for Strength