#roxanne swentzell

Text

Roxanne Swentzell

youtube

Roxanne Swentzell was born in 1962 in Taos Pueblo, New Mexico. Swentzell is a sculptor who uses the coil method, a traditional Santa Pueblo technique for clay sculpting. She also produces works in bronze. Swentzell's first public exhibition was in 1984, and her work has been in several more since, including a 1998 exhibition at the White House. Her work can be found in the collections of the National Museum of the American Indian, the Denver Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and other institutions.

#art#artists#native american#american indian#santa clara pueblo#pueblo#american indian art#indigenous#indigenous women#indigenous art#native art#native artists#new mexico#Youtube

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NCECA Conference wrap up! Feeling immense after coming home from Cincinnati. Hello to everyone I didn’t get to see, to everyone I only was able to wave at across the room, thankful for everyone I got to have an actual conversation with. My DMs are open, hope to see you again soon 1) one of my contributions to the Cup Sale “what makes a good pot these days” 2) @aderowillard stunning work, my first hi hello howdy I’m Cinci 3) Jeremy Brook’s crocheted porcelain condoms 4) Xia Zhang’s always beautiful and provocative work at @cincyartmuseum 5) more rookwood art pottery than you can shake a stick at. This is actually from Matt Morgan Art Pottery 1882-1884 6) Roxanne Swentzel’s encouraging closing lecture and her trickster gods. 7) the glint of @tyler_quintin_arts 8) @sunkooyuhceramics, the only artist I purchased for my cupboard collection this year 9) party people @cxc_ceramics_collective 10) Cincinnati’s finest, put me back together after nights of diverse beverages xx https://www.instagram.com/p/Cp-VCOor8Dn/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am fascinated by this artist's process.

“I think in clay,” she said. “Clay was the earth that grew our food, was the house we lived in, was the pottery we ate out of and prayed with. So my relationship to clay is ancestral and I think it has a deep genetic memory. It’s like a family member for us.” She remembers seeing her great-grandmother, the artist Rose Naranjo, speaking to her clay, and she said her mother, Roxanne Swentzell, learned to sculpt figures as a means to communicate long before she talked.

While Swentzell makes beautifully smooth sculptures of Indigenous women engaged in everyday activities, Simpson tends to rough things up. She leaves the surfaces of her figures uneven and adds adornments in metal, leather and other materials to create, in the words of the Los Angeles curator Helen Molesworth, “a badass, ‘Mad Max,’ ‘Blade Runner’ vibe.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

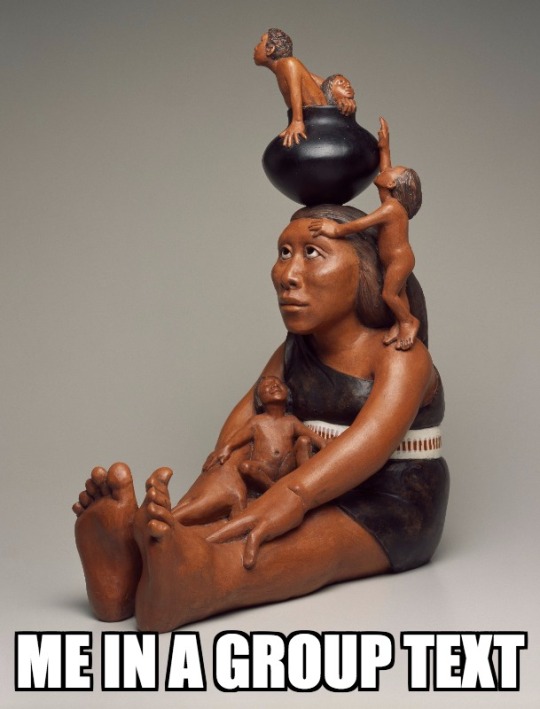

Pick one of the figures in this sculpture and do your best to take on their position. How does it feel to be in this position? When have you been in a similar position?

This sculpture incorporates many figures, each with their own distinct expression and position. The largest figure, a woman wearing a Pueblo dress, sits with her legs straight out, her hands resting on her knees, and her shoulders rolled forward a little. Her head is level, but she raises her eyes upwards, towards the vessel balanced on her head. This vessel is a traditional ceramic of the Kah’p’oo Owinge (Santa Clara Pueblo), the Tewa pueblo to which the artist Roxanne Swentzell belongs. Climbing out of this black pot are two much smaller figures. One leans on the rim, looking off in one direction, while the other figure’s head just barely begins to emerge from within the vessel. Below, standing on the shoulder of the woman with a hand resting on her forehead for support, is a standing figure, reaching up towards the two emerging from the vessel. Resting in the crook of the woman’s right arm, is the final figure: while all the other tiny figures are wide-eyed and engaged in their various activities, this figure on the woman’s lap is lounging, turning a contented face upwards as though basking in the sun.

How would you describe the expression of the woman? Is she tired, fatigued by the energy of these small figures? Is she amused and content? Is it something else? Whenever I return to her face, I find a new shade of emotion as she experiences the commotion of the many figures crawling over her. I imagine her holding her breath and watching the vessel wobble as the figures crawl out of it.

The iconography—that of a larger figure with many smaller figures crawling all over—has become a common motif in Pueblo ceramics; it is known as a storyteller figure. The first was created by Ko-Tyit (Chochiti) Pueblo artist Helen Cordero, who made it in the 1960s to honor her grandfather, a renowned storyteller. Swentzell, too, thinks about communication between generations. She has said, “We are the mothers of the next generation and the daughters of the last. Male or female...in the Pueblo world, we are 'Mothers' (nurturers) of the generations to come in a world that supports life. It is always good to remember…to nurture life, for it is our work now as it was for our parents and ancestors that came before us and it will become the work of our children.” The very clay the Swentzell uses is a reminder of this as well; she uses locally sourced clay, thus tying it to the land of New Mexico itself. She says, “To have human figures made of clay is in itself part of the theme. We are all from this Mother, all from this Earth: made of her and will return to her... I love the perspective of understanding that we all come from the Earth.” What might it mean to work for life for future generations? How does art become part of that work?

Swentzell also plays with this storyteller imagery in this sculpture, linking the idea of communication from one generation to the next with the act of creating artwork for sale. Swentzell is a renowned sculptor, and her work has been honored at the prestigious Santa Fe Indian Market. Initially, she never considered selling her work. Instead she sees sculptures as an extension of her ability to communicate, like pages in a diary. Now that she does sell her work, she often explores the relationship between Indigenous identity, Indigenous art, and commodification. This particular work is known as Making Babies for Indian Market, a reference to the annual Santa Fe Indian Market. How does the title relate to what we see in the sculpture? What might Swentzell be suggesting about the relationship between creating art and selling it?

How do art, identity, and commodification intersect? What do the implications of these intersections and relationships have for future generations? In what ways are future generations a consideration in your own life or work?

Posted by Christina Marinelli

Roxanne Swentzell (Kah'p'oo Owinge (Santa Clara Pueblo), born 1962). Making Babies for Indian Market, 2004. Clay, pigment. Brooklyn Museum, Gift in memory of Helen Thomas Kennedy, 2004.80. © artist or artist's estate

#howtolook#roxanne swentzell#Kah'p'oo Owinge#Santa Clara Pueblo#sculpture#art#artist#native american#Pueblo#storytelling#mother#children#nurturers#new mexico#generations#Sante Fe Indian Market#Indigenous art#Kah’p’oo Owinge#Ko-Tyit#Helen Cordero

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native American Heritage Month Deel III

Deze laatste week van november, en dus Native American Heritage Month, hebben we weer drie Native American kunstenaars voor je! Eerdere delen gemist? Hier vind je deel 1 en 2

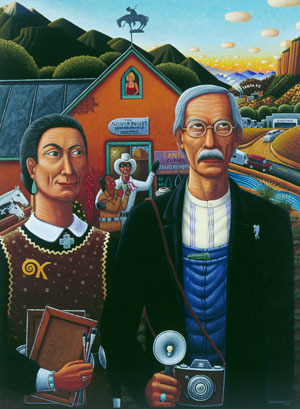

David Bradley

American Gothic

David Bradley staat bekend om zijn sociopolitieke kritiek op hedendaagse inheemse kunst en als een kunstenaar-activist die onder andere kunstfraude bestrijdt. Bradleys levendige, kleurrijke kunst herinterpreteert vaak beroemde schilderijen vanuit een inheems perspectief. Zo beeldt hij in plaats van een norse boer en zijn zus figuren als Sitting Bull, Tonto, en de Lone Ranger af.

‘To be an artist from the Indian world carries with it certain responsibilities. We have an opportunity to promote Indian truths and at the same time help dispel the myths and stereotypes that are projected upon us. I consider myself an at-large representative and advocate of the Chippewa people and American Indians in general. It is a responsibility which I do not take lightly.’

— David Bradley

Roxanne Swentzell

Ancestors

Roxanne Swentzell is een beeldhouwer, keramisch kunstenaar en inheemse voedselactivist. Swentzells werk richt zich op persoonlijk en sociaal commentaar, dat respect voor familie, cultureel erfgoed en voor de aarde weerspiegelt. Haar sculpturen tonen emotionele uitbeeldingen van haar eigen persoonlijke ervaringen uit. Ze nemen voornamelijk de vorm aan van vrouwelijke figuren en richten zich op kwesties zoals genderrollen, identiteit, politiek, familie, en het verleden.

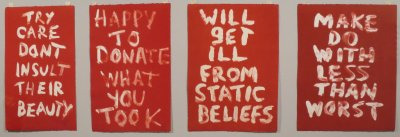

Edgar Heap of Birds

Dead Indian Stories

Edgar Heap of Birds is een multidisciplinaire kunstenaar wiens werk bestaat uit openbare kunstboodschappen, grootschalige tekeningen, acrylschilderijen en buitensculpturen. Hij staat vooral bekend om op tekst gebaseerde conceptuele kunst, zoals ‘Dead Indian Stories’. Het lijkt op openbare bewegwijzering, maar is eigenlijk commentaar op de ‘Native American experience’. Een ander voorbeeld is ‘Building Minnesota’, waarvoor Heap of Birds veertig grote, metalen, reclamebordachtige borden langs de binnenstad van Minneapolis plaatste. De borden eerden de veertig Dakota-mannen die door Abraham Lincoln en Andrew Jackson ter dood waren veroordeeld na het VS-Dakota conflict van 1862.

#native american heritage month#behind the art#native american#native american artists#native american art#kunst#art#schilderijen#beeldhouwwerk#david bradley#roxanne swentzell#edgar heap of birds#blikopeners

1 note

·

View note

Text

Virginia Stroud, enrolled UKB Cherokee and Muskogee artist

#her and Roxanne Swentzell are my favorite ever#the way they portray our people in celebration and wonder

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

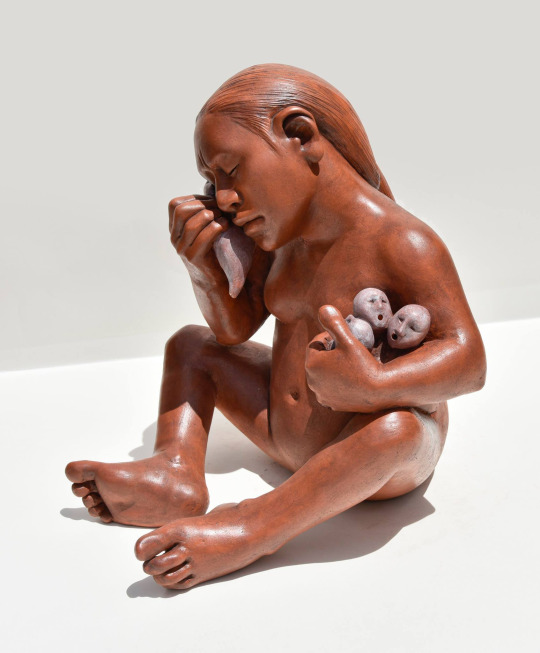

Window to the Past / Roxanne Swentzell / 1999 / Bronze

At the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona.

I love this sculpture of a woman contemplating her connection to her ancestors in a single bead. I relate to the experience. I keep a shadow box on my wall, displaying bits of my ancestor’s belongings: my grandfather’s dice, my mother’s baby eyeglasses, a buffalo nickel that my father saved, my grandmother’s schoolyard whistle - little emblems of lives lived before my own. They are worthless things, except for their magic, the traces of the spirits of the people who held them before me.

#photographers on tumblr#sculpture#Window to the Past#Roxanne Swentzell#Heard Museum#Phoenix#Arizona

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Ceremony in the Atomic Age.”

Marian Naranjo opens the wooden door and steps inside a roughly 15-square-foot adobe house called a buwah tewha, purpose-built for baking buwah, the Tewa people’s first ancestral bread. [...] Naranjo, a member of Santa Clara Pueblo, has invited me into this space [...]. Since April [2019], Naranjo’s organization Honor Our Pueblo Existence [...] have invited women from Santa Clara Pueblo and other Tewa villages into this space every second weekend of each month to “bring back one of our most important lifeways,” the baking of buwah [...]. Pueblo lifeways, things like farming and Tewa language, for example, [...] have mostly been set aside through centuries of genocide and erasure [...] during Spanish colonialism and later American occupation, Naranjo said during one of our early conversations in 2018. [...] “So that was one of the big changes, you know, that came from fences, and ownership, and those kinds of things: capitalism. [...] Before [...] everybody participated in food. Then what came here was you have to go to school, get a degree or graduate, so that you can get a job, to buy a car, to go to the grocery store, so you can eat. [...] It was forced. They couldn’t fight what was coming.” What was coming could be any number of things. [...] Whatever she was referring to, it can [...] be symbolized by the institution Naranjo has spent much of her life fighting against: Los Alamos National Laboratory.

In many ways, Naranjo said, what is now called the Espanola Valley is a place where things happen, but then reverberate throughout the country and the world, like ripples of water on a shoreline.

This phenomenon can be represented [...] [by] the most prominent example [...] the discovery of the atomic bomb in 1945.

“This place is a sacred place and the people who were planted here are still here,” she said, referring to the area that encompasses Santa Clara Pueblo, Ohkay Owingeh and the city of Espanola. “That this is one of the spots where whatever starts here, goes around the world. We know this because of what was last planted in this sacred place: the atomic age. We saw this go around the world. This short, destructive force that’s the total opposite of all of our belief.” [...]

Roxanne Swentzell, a sculptor from Santa Clara Pueblo, was one of the roughly 60 people who helped Naranjo build the two women’s houses for making buwah. [...] “From there, we were learning more about the foods, and one of the foods we re-remembered is the buwah, our traditional ceremonial bread,” Swentzell said. So the duo went to a class in Pojoaque Pueblo where they learned how to make the bread again, and wanted to bring it back to Santa Clara Pueblo. [...] She met Naranjo when Swentzell was in her 20s during a language class. “She struck me as amazing,” Swentzell said of Naranjo. “She speaks from her heart [...].”

Swentzell, who works with clay like Naranjo, said pottery is a common language.

When Marian Naranjo was six or seven years old, her father drove her up the hill, where she saw the gate to Los Alamos. “There was this tower, with guys standing up there with machine guns,” she would later tell a documentary filmmaker. “I wasn’t really scared, only that it was a time that I was born into.” [...] She graduated [...] in 1968. That summer, she worked as an intern for the Lab, going up and down the hill daily to work in dosimetry, measuring doses of radiation. [...]

Through her work with Communities for Clean Water and Amigos Bravos, she helped establish the individual industrial stormwater permit which, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, is the strongest in the nation. The permit was issued Nov. 1, 2010 as part of the settlement of the Clean Water Act lawsuit, and requires the Laboratory to meet stormwater management requirements at more than 400 legacy sites. Joni Arends, co-founder and executive director of Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (CCNS), said she met Marian when she returned to the group in 1998. At the time, Marian was working with the group to settle a lawsuit it had filed against the Laboratory because it was releasing radioactive material into the air, a violation of the Clean Air Act.That settlement resulted in funding for the Community Radiation Education Project, which paid for educational programming in pueblos about the radioactive contamination. [...] Arends said Marian gathered 144 pueblo elders for a meeting at Picuris Pueblo to reach a consensus to protect the sacred area on which the Lab was built.

-----

Text, images, and captions published by: Austin Fisher. “Ceremony in the Atomic Age.” Women of Distinction series. Rio Grande Sun. 27 July 2019. Updated 12 March 2020.

383 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘It Could Feed The World’: Amaranth, A Health Trend 8,000 Years Old That Survived Colonization

Indigenous women in North and Central America are coming together to share ancestral knowledge of amaranth, a plant booming in popularity as a health food

— Cecilia Nowell in Albuquerque, New Mexico | Friday, 06 August 2021

An elderly woman cuts an amaranth crop, in Uttarakhand, India. The plant is indigenous to North and Central America but also grown in China, India, Southeast Asia, West Africa and the Caribbean. Photograph: Hitendra Sinkar/Alamy Stock Photo

Just over 10 years ago, a small group of Indigenous Guatemalan farmers visited Beata Tsosie-Peña’s stucco home in northern New Mexico. In the arid heat, the visitors, mostly Maya Achì women from the forested Guatemalan town of Rabinal, showed Tsosie-Peña how to plant the offering they had brought with them: amaranth seeds.

Back then, Tsosie-Peña had just recently come interested in environmental justice amid frustration at the ecological challenges facing her native Santa Clara Pueblo – an Indigenous North American community just outside the New Mexico town of Española, which is downwind from the nuclear facilities that built the atomic bomb. Tsosie-Peña had begun studying permaculture and other Indigenous agricultural techniques. Today, she coordinates the environmental health and justice program at Tewa Women United, where she maintains a hillside public garden that’s home to the descendants of those first amaranth seeds she was given more than a decade ago.

“For the seeds, distance doesn’t exist. Borders don’t exist” — Maria Aurelia Xitumu of the Qachuu Aloom community

Since the 1970s, amaranth has become a billion-dollar food product. Photograph: Picture Partners/Alamy Stock Photo

They are now six-foot-tall perennials with flowering red plumes and chard-like leaves. But during that first visit in 2009, the plants were just pinhead-size seeds. Tsosie-Peña and her guests spent the day planting, winnowing, cooking and eating them – toasting the seeds in a skillet to be served over milk or mixed into honey – and talking about their shared histories: how colonization had separated them from their traditional foods and how they were reclaiming their relationship with the land.

Since the 1970s, amaranth has become a billion-dollar food – and cosmetic – product. Health conscious shoppers embracing ancient grains will find it in growing numbers of grocery stores in the US, or in snack bars across Mexico, and, increasingly, in Europe and the Asia Pacific. As a complete protein with all nine essential amino acids, amaranth is a highly nutritious source of manganese, magnesium, phosphorus, iron and antioxidants that may improve brain function and reduce inflammation.

“This is a plant that could feed the world,” said Tsosie-Peña.

For her it also has deep cultural value. She is part of growing networks of Indigenous women across North and Central America who have been sharing ancestral knowledge of how to grow and prepare amaranth. Seed exchanges, including those in New Mexico and California, are part of a larger movement to reclaim Indigenous food systems amid growing recognition of their sustainability and resilience in a time of climate crisis and industrialized agriculture.

“Supporting Indigenous people coming together to share knowledge” is vital to the land back movement, a campaign to reestablish Indigenous stewardship of Native land, and liberation of Native peoples, Tsosie-Peña said. “Our food, our ability to feed ourselves, is the foundation of our freedom and sovereignty as land-based peoples.”

This is a story of two histories: the remarkable survival of amaranth through colonization and the women like Tsosie-Peña who, in the last 20 years, have expanded networks of Indigenous people celebrating its ancient cultivation.

They are now six-foot-tall perennials with flowering red plumes and chard-like leaves. But during that first visit in 2009, the plants were just pinhead-size seeds. Tsosie-Peña and her guests spent the day planting, winnowing, cooking and eating them – toasting the seeds in a skillet to be served over milk or mixed into honey – and talking about their shared histories: how colonization had separated them from their traditional foods and how they were reclaiming their relationship with the land.

Since the 1970s, amaranth has become a billion-dollar food – and cosmetic – product. Health conscious shoppers embracing ancient grains will find it in growing numbers of grocery stores in the US, or in snack bars across Mexico, and, increasingly, in Europe and the Asia Pacific. As a complete protein with all nine essential amino acids, amaranth is a highly nutritious source of manganese, magnesium, phosphorus, iron and antioxidants that may improve brain function and reduce inflammation.

“This is a plant that could feed the world,” said Tsosie-Peña.

For her it also has deep cultural value. She is part of growing networks of Indigenous women across North and Central America who have been sharing ancestral knowledge of how to grow and prepare amaranth. Seed exchanges, including those in New Mexico and California, are part of a larger movement to reclaim Indigenous food systems amid growing recognition of their sustainability and resilience in a time of climate crisis and industrialized agriculture.

“Supporting Indigenous people coming together to share knowledge” is vital to the land back movement, a campaign to reestablish Indigenous stewardship of Native land, and liberation of Native peoples, Tsosie-Peña said. “Our food, our ability to feed ourselves, is the foundation of our freedom and sovereignty as land-based peoples.”

This is a story of two histories: the remarkable survival of amaranth through colonization and the women like Tsosie-Peña who, in the last 20 years, have expanded networks of Indigenous people celebrating its ancient cultivation.

Beata Tsosie-Peña winnows amaranth, the process of separating the seeds from the chaff. Photograph: Brooks Saucedo-McQuade

Seeds Hidden Under Floorboards

Amaranth is an 8,000-year-old pseudocereal – not a grain, but a seed, like quinoa and buckwheat – indigenous to Mesoamerica, but also grown in China, India, south-east Asia, west Africa and the Caribbean. Before the Spanish arrived in the Americas, the Aztecs and Maya cultivated amaranth as an excellent source of proteins, but also for ceremonial purposes. When Spanish conquistadors arrived on the continent in the 16th century, they threatened to cut off the hands of anyone who grew the crop, fearing that the Indigenous Americans’ spiritual connection to plants and the land might undermine Christianity. Yet, farmers continued secretly growing amaranth, which sprouted up like a weed in their fields – even as far north as the modern-day United States.

Although the Spanish outlawed amaranth when they arrived in Central America, Mexico and the south-western United States, Indigenous farmers preserved the seeds – which grew with remarkable resilience.

In Guatemala, amaranth faced another near-extinction when state forces began targeting the Maya people, and burning their fields, during the 1960-1996 civil war. To preserve their traditional foods, Mayan farmers poured handfuls of seeds into glass jars to bury in their fields or hide under floorboards. One such farmer was Magaly Salazar, a Maya K’iche’ woman from San José Poaquil, who hid a small glass jar of amaranth seeds behind one of her ceiling tiles. After the civil war, when it felt safe to start growing amaranth again, Salazar retrieved her seeds and started sharing them with other farmers.

In 2004, Sarah Montgomery, a New Mexican who’d moved to Guatemala to do food justice work with Mayan women, read about Salazar’s seeds and invited her to Rabinal, where a few dozen mostly female, survivors of the armed conflict had formed an agricultural community called Qachuu Aloom – Maya Achì for “Mother Earth”.

From left, Sarah Montgomery, Maria Elena Alvarado Ixpata and Beata Tsosie-Peña handle red plumes of amaranth. Photograph: Liz Goetz. Amaranth is a highly nutritious psuedocereal with antioxidants that could reduce inflammation. Photograph: Getty Images/StockFood

When Salazar and a friend arrived in Rabinal, they distributed their amaranth seeds among members of Qachuu Aloom and began teaching them how to plant and cook amaranth. But as they gardened, speaking in a mix of Maya Achì and Maya K’iche’, the women began exchanging stories of surviving the conflict. At one point, Montgomery overheard one of the women say, “We had no idea that what happened to us was happening to other people.” Today, Salazar’s seeds are growing in hundreds of Guatemalan gardens – Qachuu Aloom has grown to include more than 400 families from 24 Guatemalan villages – as well as in Tsosie-Peña’s yard and a public garden in northern New Mexico.

While amaranth is no longer banned, Tsosie-Peña says “planting it today feels like an act of resistance”. Reestablishing relationships with other Indigenous communities across international borders is part of a “larger movement of self-determination of Indigenous peoples”, she says, to return to the “alternative economies that existed before capitalism, that existed before the United States”.

‘I Remember My Grandma Planting This’

Tsosie-Peña first saw amaranth growing in her pueblo at her good friend Roxanne Swentzell’s house. The president of the Flowering Tree Permaculture Institute, Swentzell was teaching classes on how to garden in the high desert and also doing work around seed saving. Tsosie-Peña was interested in learning more, and in 2008 she received her Indigenous sustainable design certification from the Traditional Native American Farmers Association in Tesuque Pueblo. Montgomery was at the workshop and introduced the class to a handful of farmers from Qachuu Aloom. The next year, members of Qachuu Aloom made that trip to Santa Clara to plant amaranth in Tsosie-Peña’s garden.

Every year since then, Guatemalan farmers with Qachuu Aloom have traveled to the United States to share their knowledge of amaranth with predominantly Indigenous- and Latino-led gardens. In California, they’ve shared seeds with members of the Bishop Paiute Tribe and with urban gardens in Los Angeles; and in northern New Mexico, they’ve hosted gardening and cooking workshops in the rural community of La Madera. In 2016, when Tsosie-Peña and her colleagues at Tewa Women United broke ground on their public garden in Española, Qachuu Aloom was there to plant amaranth once again.

But Qachuu Aloom hasn’t always been the one bringing seeds – many Indigenous gardeners, such as Tsosie-Peña’s friend Roxanne Swentzell, have preserved their own amaranth. On the Hopi reservation in Arizona, for example, members of Hopi Tutskwa Permaculture still grow Hopi Red Dye Amaranth, and have shared it with Qachuu Aloom.

Tsosie-Peña says that this exchange between North and Central American farmers isn’t just about amaranth as a crop; it’s also about reconnecting to ancient trade routes that have been disrupted by increasingly militarized borders.

Left: A worker in the candy factory Dulceria Juanita in Mexico City uses amaranth to form skulls that will be decorated with sweets for Día de los Muertos on 10 October. Photograph: Carlos Tischler/Eyepix Group/Pacific Press/REX/Shutterstock. Right: Tamarind is added to the amaranth skulls and small candies are added for decoration. Photograph: Carlos Tischler/Eyepix Group/Pacific Press/REX/Shutterstock

Maria Aurelia Xitumul, a member of Qachuu Aloom since 2006 who has traveled on exchanges to California and New Mexico, echoes Tsosie-Peña. “The goal is to share experiences, not necessarily generate income, like capitalists. What we want is for the whole world to produce their own food,” she said in Spanish. “For the seeds, distance doesn’t exist. Borders don’t exist.”

Montgomery says she noticed the presence of borders in a different way when coordinating Qachuu Aloom workshops in California: many of the people they began working with in community gardens were very recent immigrants from Central America and Mexico. Their memories of amaranth were fresh. Montgomery recalls one participant seeing the amaranth and exclaiming, “I remember my grandma planting this.”

She also began noticing participants in different workshops she hosted – such as one with African refugees who’d settled in Albuquerque – connecting with the amaranth. It seemed like it had grown all over the world, but come and gone with cycles of colonization.

“There was a lot of really similar stories of colonization and how seeds were taken in these different places, how similar strategies were used to make seeds disappear, and create this domination and dependency,” Montgomery said. “But the thing about amaranth is, it comes up everywhere.”

A ‘Superweed’

In 2010, the New York Times published an article about the looming threat of superweeds – weeds which have developed to be resistant to Roundup–including amaranth. When sprayed on a field, Roundup is designed to kill all plants except Monsanto’s genetically-engineered Roundup Ready crops. But, somehow amaranth has survived – just like it did during the Spanish conquest.

“You can grow it in Hispaniola, you can grow it in northern New Mexico and the mountains of Guatemala,” says Montgomery. Xitumul was shocked when she visited the Hopi reservation in Arizona and saw how well it grew in the arid climate so different from her forested home town.

A single amaranth plant produces hundreds of seeds – something that the farmers of Qachuu Aloom celebrated when the small handful of seeds Magaly Salazar sequestered away turned into hundred-pound bags of harvest the next season.

For many Indigenous farmers in Guatemala and the United States, growing amaranth has provided a degree of economic independence, but it has also offered a route to food sovereignty.

Blanca Marsella González, a member of Qachuu Aloom, harvests amaranth plants. Photograph: JC Lemus/Juan Carlos Lemus

“Amaranth has completely changed the lives of families in our communities, not only economically, but spiritually,” said Xitumul. Growing traditional crops has allowed many Guatemalan farmers – herself included – to support their families from their ancestral homes, rather than working in Guatemala City or coastal coffee and banana plantations.

More recently, during the pandemic, Xitumul said that people with their own gardens, especially in communities that had long lockdowns, felt more secure knowing they had control over their food supply. In northern New Mexico, many pueblos, including Tsosie-Peña’s, implemented strict quarantines. To support her neighbors in navigating a food desert, Tsosie-Peña distributed seeds at the outset of the pandemic.

The week before the emergency declaration of the pandemic Tsosie-Peña was in Guatemala. When international borders began closing, she had to rush home to the United States. But a few months ago, after vaccines were widely distributed in the US, she and a handful of delegates from each of the farms that had begun planting Qachuu Aloom’s seeds traveled back to Guatemala. With them, they brought seeds from the amaranth they had each grown in their home gardens – descendants of Qachuu Aloom and Magaly Salazar’s seeds – to plant in a shared plot: a kind of solidarity garden.

“We’ve always viewed our seed relatives as relatives and kin,” says Tsosie-Peña. “We have co-evolved with them as fellow Indigenous peoples of this place.”

— Cecilia Nowell is a freelance reporter who writes about gender, inequality and the Americas and is currently based in Albuquerque, New Mexico

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Making Babies for Indian Market, Roxanne Swentzell, 2004, Brooklyn Museum: Arts of the Americas

The sculpture is a contemporary version of the traditional storyteller figure with an ironic twist. It makes a dual statement on the production of traditional-style pottery for the Santa Fe Indian Market, for sale as well as on the Pueblo potter's desire to create something lasting for generations to come. A Pueblo woman sits with her legs and arms outstretched in front of her. The figure's face resembles Roxanne Swentzell, the artist responsible for the sculpture. Her eyes look up towards the Santa Clara black pot balanced on her head. Two babies emerge from the pot. One is shown half way out, the other with its head poking up. A third baby stands on the woman's shoulder and is reaching towards one of the babies coming from the pot. A fourth baby sits on the Pueblo woman's lap with an expression of deep contentment. Making babies and making pots are equated, perhaps to protest how indigenous people themselves and their traditions are often considered as if commodities, to be purchased by non-Native people at commercial Indian Markets throughout the Southwest. The entire piece is a tour-de-force of workmanship, a hand formed sculpture that merges two worlds, the time-honored and the modern. The entire surface of the work is highly polished and is in excellent condition. © Roxanne Swentzell

Size: 23 1/2 x 8 1/2 x 17 in. (59.7 x 21.6 x 43.2 cm)

Medium: Clay, pigment

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/2706

1 note

·

View note

Text

A buffalo horn belt entitled Winyan Wánakikśin (Women Defenders of Others) created by Oglala Lakota artists Kevin Pourier and Valerie Pourier in 2018. The belt was made to honor the achievements of Native American women and was inspired by the power and influence of women during the Dakota Access Pipeline protests. It features the faces of eight notable Native American figures (listed from left to right): Susie Silook (Yupik/Inupiaq), Tipiziwin Tolman (Wichiyena Dahkota/Hunkpapa Lakota), Mary Kathryn Nagle (Cherokee Nation), Wanda Batchelor (Washoe), Jodi Archambalt (Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota), Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo), Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne/Hodulgee Muscogee), and Bobbi Jean Three Legs (Hunkpapa Lakota). The item is composed of animal hide, metal, stone, mother-of-pearl, malachite, lapis lazuli, turquoise, and sandstone. It is on display at the National Museum of the American Indian.

How & Why I Chose This Piece:

When I was researching objects for this exhibit, I wanted to find something that challenged Western narratives and teachings of history. I was looking for objects in the National Museum of the American Indian and came across Winyan Wánakikśin (Women Defenders of Others) which was being featured as part of the American Women’s History Initiative to display more accurate and inclusive representations of American women and their stories. I was initially drawn to this piece due to its use of patterns and intricate design and was curious about their significance as well as the materials that were used. However, the more I looked at this object, the more interested I was in the women on the belt. I did not recognize any of the women featured but after doing a little research into who they were, I realized that they were actually really important figures that have contributed so much to Indigenous communities. This made me think about my own Eurocentric biases and Westernized education and how this has limited my knowledge of U.S. history. Therefore, I chose this piece because I personally wanted to learn more about these women as well as different Indigenous art forms and practices, and, although in a very small way, begin to challenge what has been presented to me as the dominant narrative. This object was initially created as a way to honor the strength and accomplishments of Native American women but I wanted to focus on the process of making the belt and the viewers understanding, or lack of understanding, of who these women are and what the various patterns and designs represent, as a means of reframing it in the context of global resistance. I argue that this object visually exposes viewers to beautiful and powerful indigenous art, practices, and stories of women that destabilize colonial narratives and establish a community of global resistance against the erasure of Indigenous communities and the oppression of women. In terms of theoretical frameworks, I wanted to apply ideas from both Dipesh Chakrabarty’s “Provincializing Europe” and Frantz Fanon’s “On Violence”. In regards to Charkrabarty I focused on how, in making this object and using buffalo horn, Kevin and Valerie Pourier challenge Eurocentric biases by remaining in touch with their ancestral traditions. Looking at this piece according to Fanon’s ideas on decolonization and violence, I saw a lot of theoretical violence taking place through the work of the women featured. I specifically viewed a three-pronged structure of violence that included the creation and messages of art, teaching Native languages, and participation in legal or social advocacy. I love that although this object seems simple, it is actually really valuable in raising awareness about multiple forms of resistance and challenging viewers’ perceptions and understandings of historical narratives.

Winyan Wánakikśin as a Form of Global Resistance:

In 2016, protests over the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) began receiving national recognition and participation from Native communities and allies who viewed the project, which involved constructing an oil line near Standing Rock Sioux reservation land, as a violation of environmental, health, and human rights. The DAPL project disregarded the status of the Standing Rock Sioux as a sovereign nation with protected land rights and endangered tribal members due to the high probability of an oil leak occurring in the pipeline, which would have had a detrimental impact on water and other valuable resources for the tribe. Many Native American women held an integral role in resisting this destruction of Native land by spurring grassroots movements, leading marches, and pursuing legal action. In creating Winyan Wánakikśin, Kevin and Valerie Pourier wanted to expand the limited scope of art inspired by the protests at Standing Rock, predominantly depicting men, and instead honor the courage and power of the women involved. Their final product moves the focus beyond just Standing Rock though, incorporating Native American women who are promoting changes both locally and globally through art, law, language, and other means. In this manner, the Pouriers intend their art to be a reflection of the strength and achievements of all women.

Although it does have value solely as a commemorative piece, the belt’s physical composition using traditional materials, and the significance of specific symbolic imagery depicted on its surface visually exposes viewers to beautiful and powerful indigenous art, practices, and stories of women that destabilize colonial narratives and establish a community of global resistance against the erasure of Indigenous communities and the oppression of women.

The buffalo horns Kevin and Valerie Pourier used to make Winyan Wánakikśin are particularly important in defining it as a piece of resistance. The belt is composed of nine segments carved from this material which are then inlaid with crushed lapis lazuli, turquoise, sandstone and other elements for color. By incorporating buffalo horns into this piece, the artists pay homage to their Lakota ancestors who viewed this specific animal as an essential part of their ceremonies and livelihood. This practice is part of a larger movement of repurposing within Indigenous art as a means of honoring the entire life of an animal. The idea and application of using all parts of the animal challenges Eurocentric biases that position Native American cultural practices as underdeveloped or inferior. I think this enhances the appeal of the object by showing a sustainability which counteracts the excessive and wasteful habits typically seen in Western culture.

The construction of this belt also reflects a contemporary persistence of practicing ancestral art forms through the act of polishing the buffalo horn. This performance once again speaks to the value placed on the buffalo in Lakota culture as Kevin Pourier explains that “the black, the shininess of the horn...[is important because] for the Lakota people, the buffalo spirit lives in [the] horn cap.” Due to it’s value, the carving and polishing processes take time and great care. In fact, I was surprised to learn that it took over two weeks for the Pouriers to finish the polishing process and more than six months in total to finalize the entire piece. Despite the immense amount of time spent on a seemingly simple and insignificant element, this attention to the polish actually has a large impact on engagement with the object, giving it a full glossy effect that immediately draws viewers’ attention and encourages them to think about the significance of the materials used, the patterns incorporated, and the women featured on the belt. Through this continued connection with ancestral practices, this work of art begins to offer a way of preserving traditional art forms that are an essential part of many Indigenous communities.

The symbolic imagery of the belt further contributes to a multimodal approach in resisting the erasure of Indigenous cultures and the oppression of women. The portraits of the eight women are done in black and grey, causing the colorful patterns and designs surrounding them to stand out. These vibrant backgrounds are unique for each individual and help to characterize their personal values as well as their impact on the world. I think it’s worth noting that the belt does not include any written identification about who these women are, suggesting that they should be recognized and known by their faces and symbols alone. In this manner, the object’s unapologetic and proud portrayals of these women demand attention and recognition for them, thus becoming another way in which Winyan Wánakikśin destabilizes the ‘typical’, i.e. Eurocentric, canonization of history.

Furthermore, the imagery depicted on the belt contributes to a sort of theoretical violence as a means of resisting the erasure of Indigenous cultures and the oppression of women. I see these eight women as symbols of resistance who employ violence through three critical components: art, language, and law. Roxanne Swentzell and Susie Silook are artists who challenge stereotypes about Native Americans and promote the preservation of ancestral techniques through their work. Looking at the panels on the belt, we can see that Swentzell’s portrait is superimposed over a traditional design used in Pueblo pottery. This depiction emphasizes Swentzell’s connection to Pueblo culture and her sculptures, which provide social commentary on issues relating to Native American rights. Through her work with clay, Swentzell specifically seeks to object the commodification of Native Americans. In Silook’s panel, the artist stands next to a whale diving into light blue water. This symbol references her radical artwork protesting violence against women, using ivory and whalebone as her medium. Although there is a predominant sense of globality in the work of both artists, Silook uses an ancestral practice of carving ivory dolls, a tradition in her culture which is typically performed by men, to resist oppression on a local scale as well. Her carvings are defiant not only by embodying a role typically perceived as being for men but also in portraying women in these pieces rather than traditional animal imagery. I think the art of these women share similarities to Frantz Fanon’s ideas for decolonization. Fanon argues that “the ‘thing’ colonized becomes a man through the very process of liberation” which involves using violence to “remov[e]...heterogeneity...[and] unify...on the grounds of nation”. Applying this to Swentzell and Silook’s work, we can see that the social awareness and criticism within their art attacks these colonial structures and narratives, humanizing and uplifting the identities of Indigenous peoples, especially women.

Language as a form of violence is also brought to our attention through the portrait of Tipiziwin Tolman, a language preservationist on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. While language has been historically used as a tool for colonization, threatening or wiping out many Indigenous oral traditions, Tolman demonstrates it can also be used as a weapon against the colonizer. In learning and teaching others about her own native Lakota language, Tolman begins a process of liberation in which she rejects limited, colonial understandings and uses for language.

Finally, Mary Kathryn Nagle, Wanda Batchelor, Jodi Archambault, Suzan Harjo, and Bobbi Jean Three legs embody various elements of legal and social justice advocacy that challenge oppressive structures. Although these women have all done valuable work in demanding reparations, reclaiming land rights and resources, and ultimately speaking out for women’s rights, I want to connect this type of violence back to the DAPL protests that inspired this piece of art. In the final segment of the belt, Bobbi Jean Three Legs stands against the backdrop of a traditional Dakota floral design, her fist raised in a sign of support and solidarity. This gesture is in reference to her role organizing and leading a 2,000 mile relay run from North Dakota to Washington, D.C. to deliver a petition against DAPL. I think the beautiful and powerful imagery on the belt itself in combination with the activist’s impactful story challenges the patriarchy by asserting that women, especially Indigenous women, have agency and are influential in making changes worldwide.

The belt’s buckle further emphasizes this message by showing a picture of the earth being supported by hands of different colors. Through this part, the individual panels that represent the diverse practices and values of each of these women are linked together, establishing a community of global resistance. Ultimately, Winyan Wánakikśin is much more than an object celebrating and memorializing the accomplishments of women. It visually engages and challenges viewers to reconsider their understanding of history through the materials and stories of the women depicted on its surface.

- Kaelan H.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What do we learn in each generation? Mud Woman Rolls On by Roxanne Swentzell #denverartmuseum #mudwomanrollson #advent #adventcalendar #adventword #adventword2019 #learn #santaclara #roxanneswentzell @denverartmuseum #sculpture #latergram #storyteller (at Denver Art Museum) https://www.instagram.com/p/B6IThx3BIe1/?igshid=1brtbb3uzkpz7

#denverartmuseum#mudwomanrollson#advent#adventcalendar#adventword#adventword2019#learn#santaclara#roxanneswentzell#sculpture#latergram#storyteller

1 note

·

View note

Text

Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) 2019 Graduation Ceremony

Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) 2019 Graduation Ceremony

Rose Simpson (Santa Clara Pueblo); her daughter Cedar; Dr. Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo); and Dr. Porter Swentell (Santa Clara Pueblo). Photo by Carolyn Wright – Courtesy of IAIA

Published May 21, 2019

65 Degrees and Certificates Conferred on May 18, 2019

SANTA FE, N.M. — The Institute of American Indian Arts held their 2019 commencement ceremony at 11:00 am on Saturday, May 18, 2019.

IA…

View On WordPress

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

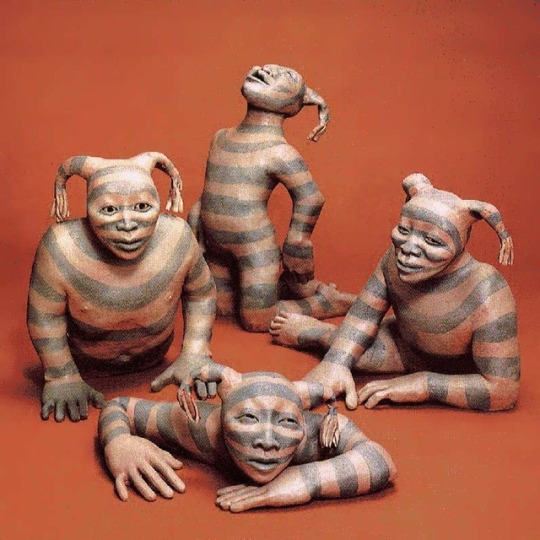

The Emergence of the Clowns by Roxanne Swentzell

Depicts the story of four clowns emerging from the underworld. I am especially drawn to the expressive gestures of each figure, fostering a sense of mischief and devilry.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We warned you, the BKM Staff loves their Art Memes. Thus, Art Meme Mondays.

Join in by browsing our digital collections and memeing one of your own—and don’t forget to tag us @brooklynmuseum!

Roxanne Swentzell (Kah'p'oo Owinge (Santa Clara Pueblo), Native American, born 1962). Making Babies for Indian Market, 2004. Memed by Jonathan Dorado

#artmememonday#art meme#meme#art#bkmamericasart#roxanne swentzell#kah'p'oo owinge#santa clara pueblo#native american#babies#group text

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center -- Albuquerque, New Mexico has been published on Elaine Webster - http://elainewebster.com/indian-pueblo-cultural-center-albuquerque-new-mexico/

New Post has been published on http://elainewebster.com/indian-pueblo-cultural-center-albuquerque-new-mexico/

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center -- Albuquerque, New Mexico

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center—Albuquerque New Mexico

One look at the IPCC website, https://indianpueblo.org/ and you’ll already have an idea of what to expect during a visit. However, along with the obvious attributes of any fine museum and cultural center, this place exudes personal stories, artworks, cultural histories, and a vibe that is difficult to explain—intuitive in nature, with a splash of solidarity among peoples.

The Pueblo People are as similar and diverse as the lands they inhabit—rugged, beautiful, and most importantly spiritual in nature. As the earth changes and folks are once again migrating to escape disaster, and/or search for opportunities, we are reminded that there is no permanence to life. Life morphs as we struggle to stay the same.

One aspect of Pueblo life that appeals is that of tight knit families and communities. Research shows that in the past (at its height AD 1000 – 1300) the welcome sign was always out. Travelers, traders, friends, and relatives were invited in and made comfortable, often necessitating the addition of accommodations, as is evident in the spread of some of the most occupied sites. It wasn’t until colonialism intruded on Indigenous life that war became common and it did not end well for Indians.

Today the tide is turning—those that questioned Native American wisdom are now wondering if we need to take a few steps back and embrace the ancients. Archaeologists and anthropologists have re-directed their research to include the Indigenous perspective and to understand how myths, legends, and religious beliefs may hold the key to understanding not just how the past unfolded, but how we can benefit today from the traditional ways.

Art, song, dance, and poetry acts as a healing balm for hurts and traumas that art too difficult to talk about. Simple signage displays more than an evident meaning. As I stood before this poem and gazed at a nearby seed jar, extraordinarily formed and painted with crude tools, hand-dug earth, and buried firing, I felt a deep desire to immerse myself in the mysteries of these people.

One exhibit includes a projected film of Maria Martinez, famous for her San Ildefonso, black on black pottery. In the film Maria digs the earth with her hands, mixes the clay, forms and decorates the pottery, and buries multiple creations in a pile of dung, dirt and stone, insulated with whatever discarded items that will hold in the heat and fire the pots. Her dedication to her work, her family and her community are legendary. The exhibit explores the challenges of the time—poverty, alcoholism, education, and the bounce-back ability to overcome them all.

Then there’s the younger generation, which is finding new ways to celebrate their existence and to show the world the benefits of life close to nature, love, good health, and family. Roxanne Swentzell, a leader and visionary, captures soulful feelings in the expressions of the faces on her sculptures. https://www.roxanneswentzell.net/towergallery_bronzes.htm

Then, as a New York City girl, I couldn’t resist this piece by Zuni artist, Silvester Hustito, as I have my own personal war going on with that city—love of a place of emergence—disdain for conflicts that destroy. As described by the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian: His images are contemporary and abstract in nature. But the general subject matter comes from Silvester’s experiences growing up in Zuni. Initiated into a Katsina clan as a youth, he “likes to make work that gives you a feeling of what I experienced, because to me it was and still is a very powerful thing.” His recent “War God” series uses symbols close to the Zuni people. While respecting the privacy of Zuni beliefs, he has tried to show the essence of the meaningful symbolism. He says he has used the War God imagery because “it’s something I admired when growing up.”

0 notes